Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent

Public Court Documents

August 31, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent, 1988. cc0e37d7-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d7059e94-38bd-4b05-bb60-2c3894aced7f/patterson-v-mclean-credit-union-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondent. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

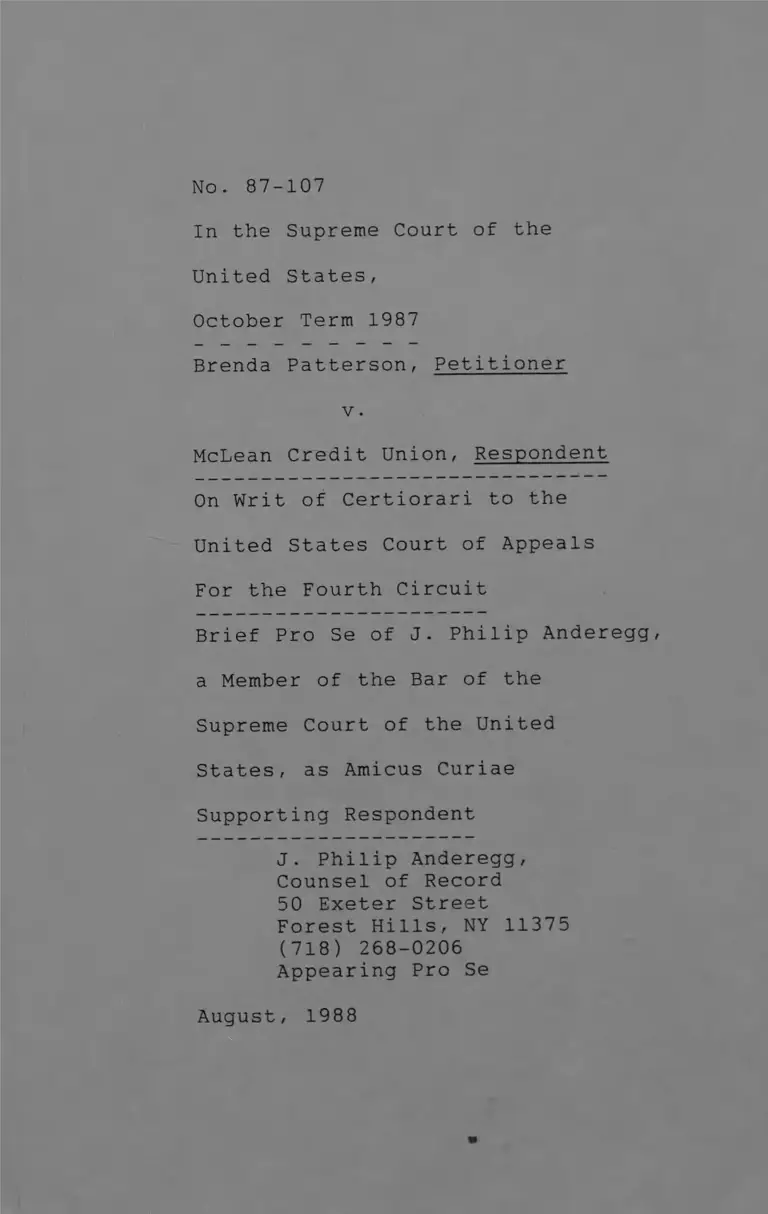

No. 87-107

In the Supreme Court of the

United States,

October Term 1987

Brenda Patterson, Petitioner

v.

McLean Credit Union, Respondent

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

Brief Pro Se of J. Philip Anderegg,

a Member of the Bar of the

Supreme Court of the United

States, as Amicus Curiae

Supporting Respondent

J. Philip Anderegg,

Counsel of Record

50 Exeter Street

Forest Hills, NY 11375

(718) 268-0206

Appearing Pro Se

August, 1988

QUESTION PRESENTED

This brief for J. Philip Anderegg

as amicus curiae deals only with the

question that the Court in its order of

April 25, 1988, asked the parties to

address on reargument: Whether the in

terpretation of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 ad

opted by this Court in Runyon v. Mc

Crary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976), should be

reconsidered.

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of Amicus Curiae

Page

2

Summary of Argument 2

Argument 4

I. The Plain Language of § 1981

II. The Legislative History of

§ 1981 does not support Runyon. 5

III. Runyon imposess on § 1981 a

Conflict with the Rights of

Aliens Under the Immigration

and Nationality Act unless,

Incongruously, That Section is

Held to Forbid Only State-

Action-Based Discrimination

Against Liens, Notwithstand

ing Its Prohibition, Under

Runyon, of Private Acts of

Discrimination Against Citizens 8

IV. Runyon Should be Reconsidered,

and Overruled, Because it Can

not Be Applied to all Contracts,

and Because the "Case-by-Case

Method of Determining the Lim

its of the Runyon Rule Leaves

the Public in Ignorance Until the

Judiciary is Led by the Accid

ents of Litigation to Speak.

This is not a System of Law

For a Free People. 11

Conclusion 12

Does Not Support Runyon. 4

(ii)

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Bhandari v. First National Bank

of Commerce, 808 F.2d 1062

(5 Cir. 1987) passim

Bhandari v . First Nztional Bank

of Commerce, 829 F.2d 1343

(5 Cir. 1987) 7,8

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal

Corp, 498 F . 2d 641 (5 Cir.m) 8

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409 (1968) 6

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160,

1976 passim

Statutes

Civil Rights Act of 1866 5

42 U.S.C. § 1981 passim

Immigration and Nationality Act,

§ 274B(a) 3, 10

Immigration Reform and Control

Act of 1986, P.L. 99-603 3, 10

(iii)

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1987

No. 87-107

Brenda Patterson, Petitioner,

v .

Mclean Credit Union, Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit

BRIEF OF J. PHILIP ANDEREGG AS AMICUS

CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENT

This brief is submitted, on the

written consent of the parties, on be

half of J. Philip Anderegg, a member of

the Bar of this Court, appearing pro

se, as amicus curiae in support of the

respondent. Letters of consent from

the parties have been lodged with the

clerk.

-2-

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The interest of J. Philip Anderegg

is that of a lawyer, a member of the

Bar of this Court, desirous of seeing

clarity, simplicity, and knowability

in the law.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160

(1976), holding 42 U.S.C. § 1981 to pro

hibit private acts of discrimination in

the making of contracts, was wrongly

decided and should be reconsidered because

1) the language and plain meaning of

§ 1981 do not support that holding;

2) the legislative history of that

section, while showing a desire on the

part of many members of the 39th Congress

which enacted

/the Civil Rights Act of 1866 to pro

vide a Federal remedy for tortious and

criminal private acts by whites against

-3-

newly emancipated blacks in the immed

iate post-Civil War period, does not show

significant support for compelling whites,

or anyone else, to make (i.e. to enter in

to) contracts with other persons, of

whatever race, even when the reluctance or

refusal on the part of one party to a pro

posed contract was based on racial an

imosity toward the other party to the pro

posed contract;

3) if Runyon was rightly decided, then

§ 1981 should prohibit acts of private

discrimination against aliens on the

ground of their alienage. Such a result

would be not only unjustified by the lan

guage and history § 1981; it would be

in clear conflict with § 274B(a) of the '

Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C.

§ 1324b(a)) as added by § 102 of the Imm

igration Reform and Control Act of 1986,

P.L. 99-603;

4-

4) Runyon, if maintained, will leave

us with an undesirable (or worse) future

case-by-case determination of the sep

aration of "the type of contract offer

within the reach* of § 1981 from the type

without" (Justice Powell, concurring, in

Runyon at 427 U.S. 188).

ARGUMENT

I. THE PLAIN LANGUAGE OF § 1981 DOES

NOT SUPPORT RUNYON■

That "the same right ... to make ...

contracts ... as is enjoyed by white cit

izens " conferred by § 1981 on ”[a]ll

persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States" cannot include a right in

A to compel B to make a contract with A,

no matter what the basis of B's unwill

ingness, because white citizens did not

"enjoy" such a right at the time of en

actment of either the Civil Rights Act

of 1866 or the Voting Rights Act of 1870,

-5-

has been set forth in the dissent of Jus

tice White in Runyon and in Bhandari v.

First National Bank of Commerce, 808 F.2d

1082 (5 Cir. 1987, hereinafter "Bhan-

dari I") at 808 F.2d 1092-93 better than

I can. Hence I will not weary the Court

with further words on the subject.

II. THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF

§ 1981 DOES NOT SUPPORT RUNYON.

As part of its argument directed to

the legislative history of § 1981, Pet

itioner's Brief on Reargument argues at

length (pp. 14 to 54) that the 39th Con

gress intended section 1 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866 to bar all racial dis

crimination, private as well as state-

action-based. As to private discriminat

ion that brief sets forth material pre

sented to Congress concerning torts and

crimes committed by whites against

blacks in the South after the emancipation

-6-

of the slaves. It also sets forth mat

erial concerning the imposition by whites

of overreaching, abusive terms in the

contracts of employment which whites made

with former slaves, and breaches by

whites of those contracts, e.g. refusals

to pay wages due. The understandable

angry reaction of members of Congress to

this material is also set forth.

By far most of this material pertains

however, in the terms of Bhandari I_' to

what Bhandari I_ calls the third (and "best")

of this Court's arguments in Jones v.

Alfred H. Mayer Co■, 392 U.S. 409 (1968)

to support the proposition that § 1 of

the 1866 Civil Rights Act reaches private

discrimination. See 808 F.2d at 1092 and

1094-95. But as Bhandari I notes (808

F.2d at 1095), the congressional desire

aroused by evidence of privat0e injustices

-7-

against blacks was a desire "to eradicate

racist practices beyond those the language

of the statute [the Civil Rights Act of

1866] appears/o reach." That Congress

knew of, and was angered by, torts, crimes

and breaches of contract committed by

whites against blacks does not justify

expanding § 1981 to cover racially motiv

ated refusals to make contracts.

As Bhandari _I explains (808 F.2d at

1095), the history of the 1870 Act

is completely different. It leaves

no doubt that Congress was concerned

with legal discriminations against

aliens by the states alone.

The 5th Circuit's reasons for so saying

are set out at 808 F.2d 1095-97, and its

views to the same effect are set out in

even greater detail in its subsequent en

banc decision of the same name dated

October 5, 1987 (hereinafter "Bhandari II")

reported at 829 F.2d-1343. See 829 F.2d

at 1345-48.

In Bhandari II, the full bench of the

5th Circuit overruled the earlier 5th

Circuit decision of Guerra v. Manchester

Terminal Corp., 498 F.2d 641 (1974) whicjfch

had held that §1981 does forbid private

discrimination based on alienage. A Pet

ition for Certiorari, No. 87-1293, was

filed in this Court on 2/2/88 for review

of Bhandar i 11 .

III. RUNYON IMPOSES ON § 1981 A CON

FLICT WITH THE RIGHTS OF ALIENS

UNDER THE IMMIGRATION AND NAT

IONALITY ACT UNLESS, INCONGRU-

ously, that section is held to

FORBID ONLY STATE-ACTION-BASED

DISCRIMINATION AGAINST ALIENS, '

NOTWITHSTANDING ITS PROHIBITION,

UNDER RUNYON, OF PRIVATE ACTS OF

DISCRIMINATION AGAINST CITIZENS.

-8-

Justice White's dissent in Runyon

-9-

points out the "logical impossibility"

(427 U.S. at 206) of holding, as Runyon

does, that U.S. citizens are protected by

§ 1981 against private acts of discriminat

ion whereas aliens are (he suppossed to

be beyond discussion) protected by the

same language only against state-action-

bapsed discrimination. Absent action by

Congress, not to be counted on, and if

Runyon is left undisturbed, either our law

(judge-made) will accept this logical

impossibility (to the discredit of the law

I submit), or it will, in the teeth of the

historical evidence as to the 1870 Civil

Rights Act detailed in the Bhanaari op

inions , hold that aliens like citizens

are protected by § 1981 against private

acts of discrimination.

This latter is an equally undesirable,

indeed a wholly unacceptable outcome.

Under section 274B(a) of the Immigration

-lo-

Act, 8 U.S.C. § I324b(a)) added by § 102

of P.L. 99-603, the Immigration Reform and

Control Act of 1986, it is an "unfair imm-

ogration-related employment practice" to

discriminate against an alien on the ground

of his alienage ("citizenship status"), but

only if the alien is lawfully admitted, is

admitted as a refugee, or is granted as

ylum, and in any of those cases has com

pleted a declaration of intention to be

come a citizen -- and has followed up that

declaration within time limits and with

results not necessary to be set out here.

Moreover, under that same section 274B(a)

an employer may systematically prefer

a citizen over an alien if the two are eq

ually qualified.

I think it fair to call a conflict a

situation wherein one law prohibits con

duct which another law, by careful choice of

languagedoes not, and that is the situat

-11-

ion here.

The way to avoid both horns of the di-

lemna is to overrule Runyon and bring

§ 1981 back to a prohibition of discrimin

ation by state action only.

IV. RUNYON SHOULD BE RECONSIDERED,

AND OVERRULED, BECAUSE IT CANNOT

BE APPLIED TO ALL CONTRACTS, AND

BECAUSE THE "CASE-BY-CASE" METH

OD OF DETERMINING THE LIMITS OF

THE RUNYON RULE LEAVES THE PUB

LIC IN IGNORANCE UNTIL THE JUDIC

IARY IS LED BY THE ACCIDENTS OF

LITIGATION TO SPEAK. THIS IS NOT

A SYSTEM OF LAW FOR A FREE PEOPLE.

Concurring in Runyon, in important

part because he thought the case did not

involve a personal contractual relation

ship such as one in which the offeror se

lects those with whom he desires to bar

gain on an individualized basis, Justice

Powell conceded (427 U.S. at 187-89) that

-12-

some offers to contract should be out

side the reach of Runyon. He also recog

nized that it might be (and I submit that

it clearly is) impossible to draw a

"bright line" easily separating the typ4

of contract offer within the reach of

§ 1981 (given the Runyon decision, he surely

meant) from the type without, i.e. out

side it. Justice White expressed similar,

and more acute misgivings in his dissent

(427 U.S. at 212). I make bold to urge

upon the Court that certainty, clarity and

knowability of rules of law are a high val

ue, for a free people, and that they are

set at an undesirable discount by Runyon.

CONCLUSION

I leave to the parties other issues.

With respect however to the issue of stare

decisis, I urge the following: Runyon

is an example of the use of legislative

history to make a statute mean something