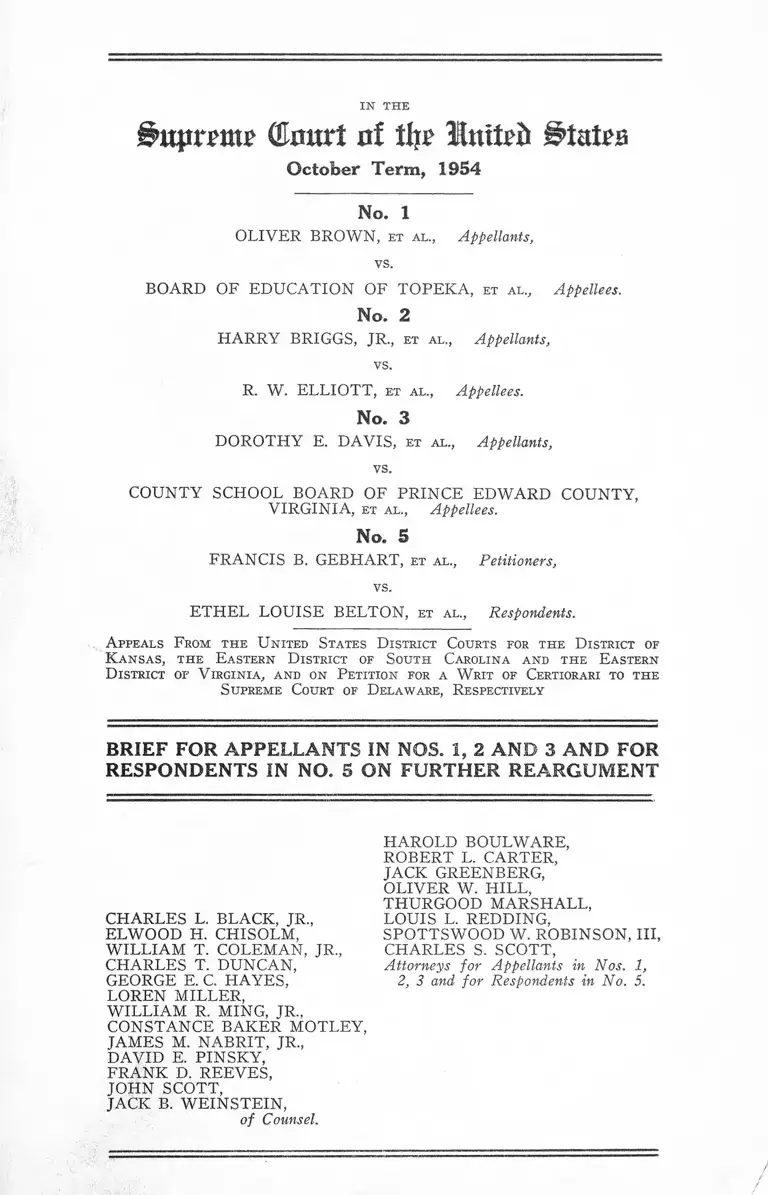

Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Appellants in Nos. 1, 2 and 3 and for Respondents in No. 5 on Further Reargument

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Brief for Appellants in Nos. 1, 2 and 3 and for Respondents in No. 5 on Further Reargument, 1954. d23ae9db-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d71bf437-ab88-4eb0-9094-f8e339a2dcac/brown-v-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants-in-nos-1-2-and-3-and-for-respondents-in-no-5-on-further-reargument. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

(Emtrt nf % lmt£& States

October Term, 1954

No. 1

OLIVER BROWN, et al ., Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, et al., Appellees.

No. 2

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., et al ., Appellants,

R. W. ELLIOTT, et al., Appellees.

No. 3

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, et al ., Appellants,

vs.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD COUNTY,

VIRGINIA, et al., Appellees.

No. 5

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, et al., Petitioners,

vs.

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, et al., Respondents.

A ppeals F rom the U nited States D istrict Courts for the D istrict of

K ansas , the E astern D istrict of South Carolina and the E astern

D istrict of V irginia, and on P etition for a W rit of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of D elaware, R espectively

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS IN NOS. 1, 2 AND 3 AND FOR

RESPONDENTS IN NO. 5 ON FURTHER REARGUMENT

CHARLES L. BLACK, JR.,

ELWOOD H. CHISOLM,

WILLIAM T. COLEMAN, JR.,

CHARLES T. DUNCAN,

GEORGE E. C. HAYES,

LOREN MILLER,

WILLIAM R. MING, JR.,

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY,

JAMES M. NABRIT, JR.,

DAVID E. PINSKY,

FRANK D. REEVES,

JOHN SCOTT,

JACK B. WEINSTEIN,

of Counsel.

HAROLD BOULWARE,

ROBERT L. CARTER,

JACK GREENBERG,

OLIVER W. HILL,

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

LOUIS L. REDDING,

SPOTTSWOOD W. ROBINSON, III,

CHARLES S. SCOTT,

Attorneys for Appellants in Nos. 1,

2, 3 and for Respondents in No. 5.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Preliminary Statement ................................................. 2

Questions Involved ....................................................... 2

Developments in These Cases Since the Last Argu

ment ............................................................................... 3

The Kansas Case ................................................... 3

The Delaware Case ............................................... 4

The South Carolina C a se ..................................... 7

The Virginia Case ................................................. 8

Argument:

I. Answering Question 4: Only a Decree Requir

ing Desegregation as Quickly as Prerequisite

Administrative and Mechanical Procedures Can

Be Completed Will Discharge Judicial Responsi

bility for the Vindication of the Constitutional

Rights of Which Appellants Are Being De

prived ........................................................................ 10

A. Aggrieved Parties Showing Denial of Con

stitutional Rights in Analogous Situations

Have Received Immediate Relief Despite

Arguments For Delay More Persuasive Than

Any Available Here ..................................... 11

B. Empirical Data Negate Unsupported Specu

lations That a Gradual Decree Would Bring

About a More Effective Adjustm ent.............. 16

II. Answering Question 5: If This Court Should

Decide to Permit an “ Effective Gradual Ad

justment” from Segregated School Systems to

Systems Not Based on Color Distinctions, It

Should Not Formulate Detailed Decrees but

Should Remand These Cases to the Courts of

First Instance with Specific Directions to Com

plete Desegregation by a Day Certain................ 24

Declaratory Provisions..................................... 26

Time Provisions ................................................. 28

Conclusion ....................................................................... 31

Table o f Cases

Arizona Copper Co. v. Gillespie, 230 U. S. 4 6 .......... 14, 28

Bolling v. Sharpe, No. 4 (Oct. Term, 1954) .............. 22

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 ............................... 25

Burr v. Bd. of School Commrs. of Baltimore, Supe

rior Court of Baltimore City, Oct. 5, 1954 (unre

ported) ......................................................................... 27

Ex Parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 ................................. 12,13, 25

Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 206 U. S. 230 ........ 14, 28

Hartford-Empire Co. v. United States, 323 U. S. 386 15

Monk v. City of Birmingham, 185 F. 2d 859 (C. A.

5th 1950), cert, denied 341 U. S. 940 ........................ 25

New Jersey v. New York, 283 U. S. 473 ..................... 14

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U. S.

H O ................................................................................. 15

Simmons v. Steiner, 108 A. 2d 173 (Del. Ct. Chanc.

1954) ............... 6

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 6 3 1 ................ 10,11

i i

PAGE

Ill

Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, 221

U. S. 1 ......................................................................... 15

Steiner v. Simmons (Del. Sup. Ct. No. 27, 195 4 )___ 6, 27

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ................................. 11

United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U. S. 106 15, 30

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S.

1 7 3 ................................................................................. 15

United States v. National Lead Co., 323 U. S. 319 . . . 15

Westinghouse Air Brake Co. v. Northern Ry. Co.,

86 Fed. 132 (C. C. S. D. N. Y. 1898)........................ 28

Wisconsin v. Illinois, 278 U. S. 367 ............................ 14

Wisconsin v. Illinois, 281 U. S. 1 7 9 ............................. 28

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U. S.

5 7 9 .................................................................................... 11,12

Statutes Cited

28 U. S. C., § 1343 ........................................................... 14

42 U. S. C., § 1983 ......................................................... 14

Del. Code Tit. 3, § 121 (1953 )....................................... 4

Del. Code Tit. 14, § 702 (1953 )..................................... 5

Del. Code Tit. 14, § 902 (1953 )..................................... 5

Other Authorities

Ashmore, The Negro and the Schools (1954)........17,19, 20,

21, 30

Brogan, The Emerson School—Community Problem,

Gary, Indiana, Bureau of Intel-cultural Education

Report (October 1947, mimeographed) .................. 19

Charleston News and Courier, August 4, 1954 ........ 8

Chein, Deutsch, Hyman and Jahoda, Consistency

and Inconsistency in Intergroup Relations, 5 J.

Social Issues 1-63 (1949 )......................................... 18

PAGE

IV

Clark, Desegregation: An Appraisal of the Evidence,

9 J. Social Issues 1-77 (1953 )....................17,18,19, 20, 21

Clark, Effects of Prejudice and Discrimination on

Personality Developments, Mid-Century White

House Conference on Children and Youth (mimeo

PAGE

graphed 1950) ............................................................. 20

Clark, Some Principles Related to the Problem of

Desegregation, 23 J. Negro Ed. 343 (1954)............ 20

Clement, Racial Integration in the Field of Sports,

23 J. Negro Ed. 226-228 (1954) ............................... 19

Conference Report, Arizona Council for Civic Unit

Conference on School Segregation (Phoenix, Ariz

ona, June 2, 1951) ....................................................... 19

Culver, Racial Desegregation in Education in Indi

ana, 23 J. Negro Ed. 296, 300-302 (1954) ..........20, 21, 30

Deutsch and Collins, Interracial Housing, a Psycho

logical Study of a Social Experiment (1951) .......... 18

Knox, Racial Integration in the Schools of Arizona,

New Mexico and Kansas, 23 J. Negro Ed. 291, 293

(1954) ..................................................................... 21

Kutner, Wilkins and Yarrow, Verbal Attitudes and

Overt Behavior Involving Racial Prejudice, 47 J.

Abnormal and Social Psych. 649-652 (1 9 5 2 ).......... 18

La Piere, Attitudes vs. Action, 13 Social Forces 230-

237 (1934) ................................................................... 18

Merton, The Social Psychology of Housing (1948).. 19

Merton, West and Jahoda, Social Fictions and Social

Facts: The Dynamics of Race Relations in Hill-

town, Columbia University Bureau of Applied

Social Research (mimeographed) ............................. 19

V

Merton, West, Jahoda and Selden, Social Policy and

Social Research in Housing, 7 J. Social Issues, 132-

MO (1951) ................................................................... 19

New York Times, “ 7 of South’s Governors Warn of

‘ Dissensions’ in Curb on Bias—Avow Right of

States to Control Public School Procedures—Six

at Meeting Refrain from Signing Statement” ,

November 14, 1954, p. 58, col. 4 -5 ............................ 19

New York Times, “ Mixed Schools Set in ‘ Border’

States” , August 29, 1954, p. 88, col. 1 -4 ................ 19

New York Times, “ New Mexico Town Quietly Ends

Pupil Segregation Despite a Cleric” , August 31,

1954, p. 1, col. 3 -4 ....................................................... 19

Next Steps in Racial Desegregation in Education,

23 J. Negro Ed. 201-399 (1954) ............................... 17

Nichols, Breakthrough on the Color Front (1954).. 19

Report by the President’s Committee on Equality of

Opportunity in the Armed Forces (1950 ).............. 17

Rose, You Can’t Legislate Against Prejudice— Or

Can You?, 9 Common Ground 61-67 (1949)............ 19

Saenger and Gilbert, Customer Reactions to the

Integration of Negro Sales Personnel, 4 Int.

J. Opinion and Attitudes Research 57-76 (1950).. 18

Southern School News, Sept. 3, 1954, p. 12, col. 3-4 8

Southern School News, Sept. 3, 1954, p. 13, col. 5 . . . 9

Southern School News, Oct. 1, 1954, p. 14, col. 2-3 9

Southern School News, Oct. 1,1954, p. 14, col. 5 ........ 10

Tipton, Community in Crisis 15-76 (1953) ................ 19,20

Wright, Racial Integration in the Public Schools of

New Jersey, 23 J. Negro Ed. 283 (1954 )................ 21

PAGE

IN THE

§>uprpmp CEnurl of fl|p States

October Term, 1954

---------------------- o-----------------------

No. 1

O liv e r B r o w n , et al., Appellants,

vs.

B oard op E d u ca tio n of T o pe k a , et al., Appellees.

No. 2

H ar r y B riggs, J r ., et al., Appellants,

vs.

R . W . E l l io t t , et al., Appellees.

No. 3

D o r o th y E . D av is , et al., Appellants,

vs.

C o u n t y S ch o ol B oard op P r in c e E dw ard C o u n t y ,

V ir g in ia , et al., Appellees.

No. 5

F ra n c is B . G e b h a r t , et al., Petitioners,

vs.

E t h e l L ouise B e l t o n , et al., Respondents.

A pp e a ls F ro m t h e U n it e d S tates D istr ic t C ourts for

t h e D istr ic t of K an sa s , t h e E aste rn D istr ict of

S o u t h C a r o lin a an d t h e E aste rn D istr ict of V ir g in ia ,

an d o n P e t it io n for a W r it of C ertio rari to t h e

S u p r e m e C ourt of D e la w a r e , R e spe c t iv e ly .

------ ---------------- o--------- --------------

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS IN NOS. 1, 2 AND 3 AND FOR

RESPONDENTS IN NO. 5 ON FURTHER REARGUMENT

2

Preliminary Statement

On May 17, 1954, this Court disposed of the basic con

stitutional question presented in these cases by deciding

that racial segregation in public education is unconstitu

tional. The Court said, however, that the formulation of

decrees was made difficult “ because these are class actions,

because of the wide applicability of this decision and

because of the great variety of local conditions . . . The

cases were restored to the docket, and the parties were

requested to present further argument on Questions 4

and 5 previously propounded by the Court for the reargu

ment last Term.

Questions Involved

Questions 4 and 5, left undecided and now the subject

of discussion in this brief, follow :

4. Assuming it is decided that segregation in public

schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment

(a) would a decree necessarily follow providing that,

within the limits set by normal geographic school

districting, Negro children should forthwith be

admitted to schools of their choice, or

(b) may this Court, in the exercise of its equity

powers, permit an effective gradual adjustment

to be brought about from existing segregated

systems to a system not based on color distinc

tions ?

5. On the assumption on which question 4(a) and (b)

are based, and assuming further that this Court will

exercise its equity powers to the end described in

question 4(fc),

(a) should this Court formulate detailed decrees in

these cases;

3

(b) if eo, what specific issues should the decrees

reach;

(c) should this Court appoint a special master to

hear evidence with a view to recommending

specific terms for such decrees;

(d) should this Court remand to the courts of first

instance with directions to frame decrees in

these cases, and if so, what general directions

should the decrees of this Court include and

what procedures should the courts of first

instance follow in arriving at the specific terms

of more detailed decrees?

Developments in These Cases Since the Last Argument

The Kansas Case

On September 3,1953, the Topeka School Board adopted

the following resolution:

Be it resolved that it is the policy of the Topeka

Board of Education to terminate the maintenance

of segregation in the elementary schools as rapidly

as is practicable.

On September 8, 1953, appellees ordered segregation

terminated in two of the nineteen school districts in Topeka.

In September, 1954, segregation was completely terminated

in ten other school districts and partially in two.

There is now a total school enrollment of approximately

8,500 children of elementary school age attending 23 ele

mentary schools. Of the 8,500 children enrolled, approxi

mately 700 Negro children are in four elementary schools

for Negroes. There are 123 Negro children now attend

ing schools on anon-segregated basis pursuant to appellees’

implementation of its policy of removing segregation

from the public school system. The blunt truth is that

4

85% of the Negro children in Topeka’s elementary schools

are still being denied the constitutional rights for which

appellants sought redress in their original action.

While Topeka has been effectuating its plan, several

other cities of the first class have undertaken the abolition

of segregated schools. Lawrence and Pittsburg have

completely desegregated. Kansas City, Abilene, Leaven

worth and Parsons have ordered partial desegregation.

Wichita and Salma have revised their school regulations

to permit Negro children to attend schools nearest their

homes. Only Coffeeville and Fort Scott have not taken

any affirmative action whatsoever.

The Delaware Case

By order of the Court of Chancery, affirmed by the

Supreme Court of Delaware, the named plaintiffs were

immediately admitted to the schools to which they applied.

These plaintiffs and other members of the class are in their

third year of uninterrupted attendance in the two Dela

ware schools named in the order. That attendance has

been marked by no untoward incident. The order, how

ever, did not result in elimination of separate schools for

Negroes in the two school districts involved, in each of

which one segregated elementary school is yet maintained

by petitioners.

The State Board of Education has statutory authority

to “ exercise general control and supervision over the

public schools of the State, including . . . the determination

of the educational policies of the State and the seeking

in every way to direct and develop public sentiment in

support of public education.” D e law ar e C ode, Title 14,

Section 121 (1953). Accordingly, the State Board of Edu

cation, on June 11, 1954, adopted a statement of “ Policies

Regarding Desegregation of Schools of the State” and

announced “ a general policy” that it “ intends to carry

5

out the mandates of the United States Supreme Court de

cision as expeditiously as possible.” It further requested

that “ the school authorities together with interested citizen

groups throughout the State should take immediate steps

to hold discussions for the purpose of (1) formulating

plans for desegregation in their respective districts and

(2) presenting said plans to the State Board of Education

for review.”

On August 19, 1954, the State Board of Education re

quested “ that all schools, maintaining four or more

teachers, present a tentative plan for desegregation in their

area on or before October 1, 1954 . ”

The desegregation plans of the Claymont Board of Edu

cation, whose members are petitioners here, providing for

the complete termination of segregation, were approved

by the State Board of Education on August 26, 1954. These

plans have been partially put into operation.

No plan ending segregation in the Hockessin schools,

the other Delaware area in the litigation here, has yet been

formulated.

Delaware statutes provide for two types of public

school districts, exclusive of the public school system in

Wilmington which is practically autonomous. One type is

commonly known as the State Board District. As to

it, the statute provides that the “ Board of School Trustees

shall be the representative in the District of the State

Board of Education.” D elaw ab e C ode, Title 14, Section

702 (1953). There are 98 such units. The other type is the

Special School District, concerning which the statute pro

vides that “ There shall be a Board of Education which

shall be responsible for the general administration and

supervision of the free public schools and educational in

terests of the District.” D elaw ar e C ode, Title 14, Section

902 (1953). There are fifteen Special School Districts.

6

Desegregation in the school districts of Delaware is

illustrated by the table below:

S ta te B oard D istricts

Partial Complete No

Desegregation Desegregation Desegregation Total

New Castle County .. 4 1 26 31

Kent County ............ 0 0 24 24

Sussex County ........ 0 0 43 43

98

S p e c ia l S c h o o l D istr icts

Partial Complete No

Desegregation Desegregation Desegregation Total

New Castle County . . 3 1 1 5

Kent County ............ . 1 0 3 4

Sussex County * . . . . . 0 0 6 6

15

Wilmington, which is in New Castle County and con

tains 34% of the population of the State, in June desegre

gated all elementary and secondary schools for the 1954

summer session. It has also completely desegregated its

night school sessions. Beginning in September, 1954, de

segregation of all elementary schools was effectuated, with

some integration of teachers.

* Partial desegregation, that is, on the high school level, was insti

tuted by the Milford Board of Education, in Sussex County. This

action was later revoked and a test of the revocation is now pend

ing in the Delaware courts. See Simmons v. Steiner, 108 A. 2d 173

(Del. Ct. Chanc. 1954). In that case the Vice-Chancellor found the

Negro plaintiffs’ rights to remain as students in Milford High

School “ clear and convincing” and restrained the Board of Educa

tion from excluding them. However, the Supreme Court of Dela

ware temporarily stayed the injunction to give that court sufficient

time to examine “ serious questions of law.” Argument has been

scheduled for December 13, 1954. Steiner v. Simmons (Del. Sup

Ct. No. 27, 1954).

7

The school districts involved in this litigation also are

in New Castle County, which has 68% of the State’s popu

lation. Desegregation in varying degrees has started in

every major school district in this county, except one.

The State Board of Education has made specific re

quests to 58 of the 113 school districts in the State to

submit such plans. Another six districts have stated that

any kind of plan they may have would be more or less

nullified by overcrowded classroom conditions. Fourteen

others have indicated that they desire to await the man

date of this Court. The remaining districts have not re

sponded to the State Board.

In summary, school districts in areas comprising more

than 50% of the population of Delaware have undertaken

some desegregation of the public schools. Many school

districts in semi-urban and rural areas have undertaken

no step. The ultimate responsibility for effectuating- de

segregation throughout Delaware rests with petitioners

here, members of the State Board of Education.

The South Carolina Case

Since May 17, 1954, South Carolina’s fifteen-man legis

lative “ Segregation Study Committee” was reorganized

and has conferred with the Governor, State education offi

cials, other legislators and spokesmen from various civic

and teacher organizations. All of their meetings have

been closed to the public. The Committee also visited

Louisiana and Mississippi “ to observe what was being

done in those states to preserve segregated schools.”

On July 28, the committee issued an interim report

which recommended that public schools be operated during

the coming year “ in keeping with previously established

policy.” The committee construed its assignment as being

the formulation of courses of action whereby the State

could continue public education “ without unfortunate dis

ruption by outside forces and influences which have no

8

knowledge of recent progress and no understanding of the

problems of the present and future. . . . ” Moreover, the

report stated that the committee also recognized “ the need

for a system in keeping with public opinion and established

traditions and living patterns.”

The State Attorney General insisted that this Court

should not undertake to direct further action even by

the school district involved and announced that he con

sidered the Clarendon County case “ purely a local matter

as far as the parties to the suit are concerned.”

In Rock Hill (population 25,000 with 20% Negroes) a

Catholic grade school voluntarily desegregated. Opening

day enrollment was 29 white students and five Negroes.

There has been no report of overt action against this

development; but the parents of some of the children have

been remonstrated with by neighbors and workers.1

A newspaper reportla of a public speech of E. B. Mc

Cord, one of the appellees herein, superintendent of educa

tion for Clarendon County, states in part:

There will be no mixed schools in Clarendon

County as long as there is any possible way for

present leadership to prevent them.

So declared L. B. McCord of Manning, Claren

don County superintendent of education, in an ad

dress before the Lions Club here Monday night.

Decrying the fact that “ Our churches seem to

be letting their zeal run away in leading the way,”

he denounced de-segregation as contrary to the

Scriptures and to good sense.

The Virginia Case

On May 27, 1954, the State Board of Education advised

city and county school boards to continue segregation dur

ing the present school year.

1 Southern School News, Sept. 3, 1954, p. 12, col. 3-4.

la Charleston News and Courier, August 4, 1954.

9

On August 28, the Governor named a thirty-two-man,

all-white legislative commission to study the problems

raised by the Court’s ruling and to prepare a report and

recommendations to the legislature and to him. The Gov

ernor then announced:

. . . I am inviting the commission to ascertain,

through public hearings and such other means as

appear appropriate, the wishes of the people of

Virginia; to give careful study to plans or legisla

tion or both, that should be considered for adoption

in Virginia after the final decree of the Court is

entered, and to offer such other recommendations

as it may deem proper as a result of the decision of

the Supreme Court affecting the public schools.2

At its first meeting the commission adopted a rule

that:

All meetings of the commission shall be execu

tive and its deliberations confidential, except when

the meeting consists of a public hearing or it is

otherwise expressly decided by the commission.3

By October, the local school boards or boards of super

visors of approximately 25 of the state’s 98 counties had

adopted and forwarded to the Governor resolutions urging

the continuation of segregated schools.

In May, 1954, the Richmond Diocese of the Roman

Catholic Church, which includes all but 6 of Virginia’s

counties, announced that during the Fall of 1954, Negroes

would for the first time be admitted to previously all-white

Catholic parochial schools where there was no separate

parochial school for Negroes. Approximately 40 Negro

pupils of a total of 3,527 are enrolled in four hig’h and six

2 Southern School News, Sept. 3, 1954, p. 13, col. 5.

3 Southern School News, Oct. 1, 1954, p. 14, col. 2-3.

1 0

elementary parochial schools formerly attended only by

white pupils. The Superintendent of the Biehmond Diocese

states that integration in these schools “ has worked out

magnificiently, without a ripple of discontent, . . . . ” 4

ARGUMENT

I .

Answering Question 4: Only a Decree Requiring

Desegregation as Quickly as Prerequisite Administra

tive and Mechanical Procedures Can Be Completed

Will Discharge Judicial Responsibility for the Vindica

tion of the Constitutional Rights of W hich Appellants

Are Being Deprived.

In the normal course of judicial procedure, this Court’s

decision that racial segregation in public education is un

constitutional would be effectuated by decrees forthwith en

joining the continuation of that segregation. Indeed, in

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631, when effort was

made to secure postponement of the enforcement of similar

rights, this Court not only refused to delay action but

accelerated the granting of relief by ordering its mandate

to issue forthwith.

In practical effect, such disposition of this litigation

would require immediate initiation of the administrative

procedures prerequisite to desegregation, to be followed

by the admission of the complaining children and others

similarly situated to unsegregated schools at the beginning

of the next academic term. This means that appellees

will have had from May 17, 1954, to September, 1955, to

complete whatever adjustments may be necessary.

4 Id. at p. 14, col. 5.

1 1

If appellees desire any postponement of relief beyond

that date, the affirmative burden must be on them to state

explicitly what they propose and to establish that the

requested postponement has judicially cognizable advan

tages greater than those inherent in the prompt vindication

of appellants’ adjudicated constitutional rights. Moreover,

when appellees seek to postpone the enjoyment of rights

which are personal and present, Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U. S. 629; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631,

that burden is particularly heavy. When the rights of

school children are involved the burden is even greater.

Each day relief is postponed is to the appellants # a day of

serious and irreparable injury; for this Court has announced

that segregation of Negroes in the public schools ‘ ‘ generates

a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community

that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely

ever to be undone. . . . ” And, time is of the essence be

cause the period of public school attendance is short.

A. Aggrieved Parties Showing Denial of Consti

tutional Rights in Analogous Situations Have

Received Immediate Relief Despite Arguments

For Delay More Persuasive Than Any Avail

able Here.

Where a substantial constitutional right would be

impaired by delay, this Court has refused to postpone

injunctive relief even in the face of the gravest of public

considerations suggested as justification therefor. In

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U. 8. 579,

this Court upheld the issuance of preliminary injunctions

restraining the Government’s continued possession of steel

mills seized under Presidential order intended to avoid a

work stoppage that would imperil the national defense

during the Korean conflict. The Government argued that

even though the seizure might be unconstitutional, the

* As used in this Brief, “ appellants” include the respondents in

No. 5.

1 2

public interest in uninterrupted production of essential

war materials was superior to the owners ’ rights to the

immediate return of their properties. It is significant that

in the seven opinions filed no Justice saw any merit in this

position. If equity could not appropriately exercise its

broad discretion to withhold the immediate grant of relief

in the Youngstown case, such a postponement must cer

tainly be inappropriate in these cases where no comparable

overriding consideration can be suggested.

Similarly in Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283, this Court

rejected the Government’s argument that hardship and

disorder resulting from racial prejudice could justify delay

in releasing the petitioner. There, the argument made by

the Government to justify other than immediate relief was

summarized in the Court’s opinion as follows (pp. 296-297):

It is argued that such a planned and orderly re

location was essential to the success of the evacuation

program; that but for such supervision there might

have been a dangerously disorderly migration of

unwanted people to unprepared communities; that

unsupervised evacuation might have resulted in hard

ship and disorder ; that the success of the evacuation

program was thought to require the knowledge that

the Federal government was maintaining control over

the evacuated population except as the release of

individuals could be effected consistently with their

own peace and well-being and that of the nation;

that although community hostility towards the

evacuees has diminished, it has not disappeared and

the continuing control of the Authority over the

relocation process is essential to the success of the

evacuation program. It is argued that supervised

relocation, as the chosen method of terminating the

evacuation, is the final step in the entire process and

is a consequence of the first step taken. It is con

ceded that appellant’s detention pending compliance

with the leave regulations is not directly connected

with the prevention of espionage and sabotage at

the present time. But it is argued that Executive

Order No. 9102 confers power to make regulations

13

necessary and proper for controlling situations

created by the exercise of the powers expressly

conferred for protection against espionage and sabo

tage. The leave regulations are said to fall within

that category.

In a unanimous decision, with the Court’s opinion by

Mr. Justice Douglas and two concurring opinions, the

Court held that the petitioner must be given her uncondi

tional liberty because the detention was not permissible by

either statutory or administrative authorization. Viewing

the petitioner’s right as being in that “ sensitive area of

rights specifically guaranteed by the Constitution” (p.

299), the Court rejected the Government’s contention that

a continuation of its unlawful course of conduct was neces

sary to avoid the harmful consequences which otherwise

would follow.

It is true that in the Endo case the contention rejected

was that an executive order (which on its face did not

authorize the petitioner’s detention) ought to be extended

by “ construction” so as to entitle the Relocation Authority

to delay the release of the petitioner until it felt that social

conditions made it convenient and prudent to do so. In

this case, the suggestion is that this Court, in the exercise

of its equity powers, ought to withhold appellants’ con

stitutional rights on closely similar grounds. But this

is not a decisive distinction. If, as the Endo case held,

the enjoyment of a constitutional right may not be deferred

by a process of forced construction on the basis of

factors closely similar to the ones at work in the instant

case, then certainly this Court ought not to find in its

equitable discretion a mandate or empowerment to obtain

the same result.

In the Endo case, the national interest in time of war

was present. In these cases, no such interest exists. Thus,

there is even less basis for delaying the immediate enjoy

ment of appellants’ rights.

14

Counsel have discovered no case wherein this Court

has found a violation of a present constitutional right but

has postponed relief on the representation by governmental

officials that local mores and customs justify delay which

might produce a more orderly transition.

It would be paradoxical indeed if, in the instant cases,

it were decided for the first time that constitutional rights

may be postponed because of anticipation of difficulties

arising out of local feelings. These cases are brought to

vindicate rights which, as a matter of common knowledge

and legal experience, need, above all others, protection

against local attitudes and patterns of behavior.5 6 They

are brought, specifically, to uphold rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment which are not to be qualified, sub

stantively or remedially, by reference to local mores. On

the contrary, the Fourteenth Amendment, on its face and

as a matter of history, was designed for the very purpose

of affording protection against local mores and customs,

and Congress has implemented that design by providing

redress against aggression under color of state laws,

customs and usages. 28 U. S. C. § 1343; 42 U. 8. C. § 1983.

Surely, appellants’ rights are not to be enforced at a

pace geared down to the very customs which the Four

teenth Amendment and implementing federal laws were

designed to combat.

Cases in which delays in enforcement of rights have been

granted involve totally dissimilar considerations. Such cases

generally deal with the abatement of nuisances, e.g.,

New Jersey v. New York, 283 U. S. 473; Wisconsin v. Illi

nois, 278 U. S. 367; Arizona Copper Co. v. Gillespie, 230

U. S. 46; Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 206 U. S. 230;

or with violations of the anti-trust laws, e.g., ScMne

5 In the instant cases, dark and uncertain prophecies as to antici

pated community reactions to school desegregation are speculative

at best.

15

Chain Theaters v. United States, 334 U. S. 110; United

States v. National Lead Co., 332 U. S. 319; United States v.

Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S. 173; Hartford-Empire

Co. v. United States, 323 IT. 8. 386; United States v. Ameri

can Tobacco Co., 221 IT. 8. 106; Standard Oil Go. of New

Jersey v. United States, 221 IT. S. 1.

These cases are readily distinguishable, and are

not precedents for the postponement of relief here. In

the nuisance cases, the Court allowed the offending- parties

time to comply because the granting of immediate relief

would have caused great injury to the public or to the

defendants with comparatively slight benefit to the plain

tiffs. In the instant cases, a continuation of the unconsti

tutional practice is as injurious to the welfare of our gov

ernment as it is to the individual appellants.

In the anti-trust cases, delay could be granted without

violence to individual rights simply because there were no

individual rights on the plaintiff’s side. The suits were

brought by the Government and the only interest which

could have been prejudiced by the delays granted is the

diffuse public interest in free competition. The delays

granted in anti-trust cases rarely, if ever, permit the con

tinuance of active wrongful conduct, but merely give time

for dissolution and dissipation of the effects of past mis

conduct. Obviously, these cases have nothing to do with

ours.

It should be remembered that the rights involved in

these cases are not only of importance to appellants and

the class they represent, but are among the most important

in our society. As this Court said on May 17th:

Today, education is perhaps the most im

portant function of state and local governments.

Compulsory school attendance laws and the great

expenditures for education both demonstrate our

16

recognition of the importance of education to our

democratic society. It is required in the perform

ance of our most basic public responsibilities, even

service in the armed forces. It is the very founda

tion of good citizenship. Today it is a principal

instrument in awakening the child to cultural values,

in preparing him for later professional training,

and in helping him to adjust normally to his en

vironment. In these days, it is doubtful that any

child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life

if he is denied the opportunity of an education.

Such an opportunity, where the state has under

taken to provide it, is a right which must be made

available to all on equal terms.

Neither the nuisance cases nor the anti-trust cases

afford any support for delay in these cases. On the con

trary, in cases more nearly analogous to the instant cases,

this Court has held that the executive branch of the gov

ernment could not justify the detention of wrongfully

seized private property on the basis of a national economic

crisis in the midst of the Korean conflict. Nor could the

War Relocation Authority wrongfully detain a loyal

American because of racial tension or threats of disorder.

It follows that in these cases this Court should apply

similar limitations to the judiciary in the exercise of its

equity power when a request is made that it delay enjoy

ment of personal rights on grounds of alleged expediency.

B. Empirical Data Negate Unsupported Specula

tions That a Gradual Decree Would Bring

About a More Effective Adjustment.

Obviously, we are not aware of what appellees will

advance on further argument as reasons for postponing

the enforcement of the rights here involved. Therefore,

the only way we can discuss Question 4(b) is by conjecture

in so far as reasons for postponement are concerned.

17

There is no basis for the assumption that gradual

as opposed to immediate desegregation is the better,

smoother or more “ effective” mode of transition. On

the contrary, there is an impressive body of evidence which

supports the position that gradualism, far from facilitat

ing the process, may actually make it more difficult; that,

in fact, the problems of transition will be a good deal less

complicated than might be forecast by appellees. Our

submission is that this, like many wrongs, can be easiest

and best undone, not by “ tapering o ff” but by forthright

action.

There is now substantial documented experience with

desegregation in this country, in schools and elsewhere.6

On the basis of this experience, it is possible to estimate

with some accuracy the chances of various types of

“ gradual” plans for success in minimizing trouble during

the period of transition.

Some plans have been tried involving a set “ deadline”

without the specification of intervening steps to be taken.

Where such plans have been tried, the tendency seems to

have been to regard the deadline as the time when action

is to be initiated rather than the time at which desegrega

tion is to be accomplished. Since there exists no body

of knowledge that is even helpful in selecting an optimum

time at the end of which the situation may be expected

to be better, the deadline date is necessarily arbitrary and

hence may be needlessly remote.7

6 See A shmore, T he N egro and th e Schools (1954) ; Cla rk ,

D esegregation : A n A ppraisal of th e Evidence, 9 J. Social

I ssues 1-77 (1953); N ext Steps in R acial D esegregation in

E ducation , 23 J. N egro E d. 201-399 (1954).

See also R eport by th e P resident’s Comm ittee on E quality

of O pportunity in th e A rmed F orces (1950).

7 A shmore, op . tit . supra note 6, at 70, 71, 79, 80; Clark , op .

cit . supra note 6, at 36, 45.

1 8

A species of the “ deadline” type of plan attempts to

prepare the public, through churches, radio and other

agencies, for the impending change. It is altogether con

jectural how successful such attempts might be in actually

effecting change in attitude. The underlying assumption—

that change in attitude must precede change in action—

is itself at best a highly questionable one. There is a

considerable body of evidence to indicate that attitude may

itself be influenced by situation 8 and that, where the situa

tion demands that an individual act as if he were not

prejudiced, he will so act, despite the continuance, at least

temporarily, of the prejudice.9 We submit that this Court

can itself contribute to an effective and decisive change

in attitude by insistence that the present unlawful situa

tion be changed forthwith.

As to any sort of “ deadline” plan, even assuming that

community leaders make every effort to build community

support for desegregation, experience shows that other

forces in the community will use the time allowed to firm

8 Clark , op . cit. supra note 6, at 69-76.

9 K utner , W il k in s and Y arrow , V erbal A ttitudes and

O vert Behavior I nvolving R acial P rejudice, 47 J. A bnormal

and Social P sy ch . 649-652 (1952); L a P iere, A ttitudes vs.

A ction , 13 Social F orces 230-237 (19 34 ) ; Saenger and G il

bert, Customer R eactions to th e I ntegration of N egro

Sales P ersonnel, 4 I n t . J. O pinion and A ttitudes R esearch

57-76 (1950); D eutsch and Collins, I nterracial H ousing ,

A P sychological Study of a Social E xperim ent (1951);

C h e in , D eutsch , H y m a n and Jahoda, Consistency and I ncon

sistency in I ntergroup R elations, 5 J. Social I ssues 1-63

(1949).

19

UP an(J build opposition.10 At least in South Carolina and

Virginia, as well as in some other states affected by this

decision, statements and action of governmental officials

since May 17th demonstrate that they will not use the time

allowed to build up community support for desegrega

tion.11 Church groups and others in the South who are

seeking to win community acceptance for the Court’s May

8 (cont.) A shmore, op. cit. supra note 6, at 42; New York Times,

“ Mixed Schools Set in ‘Border’ States” , August 29, 1954, p. 88,

col. 1-4; New York Times, “ New Mexico Town Quietly Ends Pupil

Segregation Despite a Cleric” , August 31, 1954, p. 1, col. 3-4; R ose,

Y ou Ca n ’t L egislate A gainst P rejudice— O r Can Y o u ?, 9

Comm on Ground 61-67 (1949), reprinted in R ace P rejudice and

D iscrim in atio n , (Rose ed. 1951); N ichols, Breakthrough on

th e Color F ront (1954); M erton, W est and Jahoda, Social F ic

tions and Social Fa c t s : T he D ynam ics of R ace R elations

in H illto w n , Colum bia U niversity B ureau of A pplied Social

R esearch (mimeographed); M erton, W est, Jahoda and Selden,

Social P olicy and Social R esearch in H ousing, 7 J. Social

I ssues, 132-140 (1951); M erton, T he Social P sychology of

H ousing (1948).

South as well as North, people’s actions and attitudes were

changed not in advance of but after the admission of Negroes into

organized baseball. See Clem ent , R acial I ntegration in the

F ield of Sports, 23 J. N egro Ed. 226-228 (1954). Objections to

desegregation have generally been found to be greater before than

after its accomplishment. Clark , op. cit. supra note 6, passim; Con

ference R eport, A rizona Council for Civic U n ity Conference

on School Segregation (Phoenix, Arizona, June 2, 1951).

10 Clark , op. cit. supra note 6, at 43, 44; Brogan, T he E mer

son School— Co m m u n ity P roblem, Gary , I n d ian a , B ureau of

I ntercultural E ducation R eport (October 1947, mimeo

graphed); T ipton , Co m m u n ity in Crisis 15-76 (1953).

11 For the latest example of this, see New York Times, “ 7 of

South’s Governors Warn of ‘Dissensions’ in Curb on Bias— Avow

Right of States to Control Public School Procedures— Six at Meet

ing Refrain from Signing Statement” , November 14, 1954, p. 58,

col. 4-5.

2 0

17th decision cannot be effective without the support of a

forthwith decree from this Court.

Besides the “ deadline” plans, various “ piecemeal”

schemes have been suggested and tried. These seem to be

inspired by the assumption that it is always easier and

better to do something slowly and a little at a time than

to do it all at once. As might be expected, it has appeared

that the resistance of some people affected by such schemes

is increased since they feel arbitrarily selected as experi

mental animals. Other members in the community observe

this reaction and in turn their anxieties are sharpened.12

Piecemeal desegregation of schools, on a class-by-class

basis, tends to arouse feelings of the same kind 13 and these

feelings are heightened by the intra-familial and intra

school differences thus created.14 It would be hard to im

agine any means better calculated to increase tension in

regard to desegregation than to so arrange matters so that

some children in a family were attending segregated and

others unsegregated classes. Hardly more promising

of harmony is the prospect of a school which is segregated

in the upper parts and mixed in the lower.

When one looks at various “ gradual” processes, the

fact is that there is no convincing evidence which supports

the theory that “ gradual” desegregation is more “ effec

12 T ipton , op. cit. supra note 11, at 42, 47, 57, 71 ; Clark , Some

P rinciples R elated to th e P roblem of D esegregation, 23

J. N egro Ed. 343 (1954); Culver, R acial D esegregation in

Education in I n d ian a , 23 J. N egro Ed. 300 (1954).

13 A shmore, op. cit. supra note 6, at 79, 80 ; Clark , D esegrega

tion : A n A ppraisal of th e Evidence, op. cit. supra note 6, at

36, 45.

14 Clark , E ffects of P rejudice and D iscrim ination on P er

sonality D evelopments, M id-Century W h ite H ouse Confer

ence on C hildren and Y outh (mimeographed, 1950).

2 1

tive ’ ’.lo * * * * * On the contrary, there is considerable evidence that

the forthright way is a most effective way.16

The progress of desegregation in the Topeka schools is

an example of gradualism based upon conjecture, fears and

speculation regarding community opposition which might

delay completion of desegregation forever. The desegrega

tion plan adopted by the Topeka school authorities called

for school desegregation first in the better residential areas

of the city and desegregation followed in those areas where

the smallest number of Negro children lived. There is little

excuse for the school board’s not having already completed

desegregation. Apparently either the fact that the school

board, in order to complete the transition, may have to

utilize one or more of the former schools for Negroes and

16 A shmore, op. tit. supra note 6, at 80:

Proponents of the gradual approach argue that it mini

mizes public resistance to integration. But some school offi

cials who have experienced it believe the reverse is true. A

markedly gradual program, they contend, particularly one

which involves the continued maintenance of some separate

schools, invites opposition and allows time for it to be organ

ized. Whatever the merit of this argument, the case histories

clearly indicate a tendency for local political pressure to be

applied by both sides when the question of integration is

raised, and when policies remain unsettled for a protracted

period the pressures mount. One school board member in

Arizona privately expressed the wish that the state had gone

all the way and made integration mandatory instead of

optional— thus giving the board something to point to as jus

tification for its action.

16 Clark , op. tit. supra note 6, at 46, 47; W right, R acial I nte

gration in th e P ublic S chools of N ew Jersey, 23 J. N egro E d.

283 (1954); K nox , R acial I ntegration in th e Schools of

A rizona , N ew M exico , and K ansas, 23 J. N egro Ed. 291, 293

(1954); Culver, R acial D esegregation in Education in I ndi

a n a , 23 J. N egro E d. 296, 300-302 (1954).

2 2

assign white children to them or the fact that it must now

reassign some 700 Negro children to approximately seven

former all-white schools, seems to present difficulties to

appellees. One must remember that in Topeka there has

been complete integration above the sixth grade for many

years. The schools already desegregated have reported no

difficulties. There can hardly be any basic resistance to

nonsegregated schools in the habits or customs of the city’s

populace. The elimination of the remnants of segregation

throughout the city’s school system should be a simple

matter.

No special public preparations involving teachers, par

ents, students or the general public were made, nor were

they necessary in advance of either the first or second step

in the implementation of the Board’s decision to desegre

gate the school system. Indeed, the Board of Education

adopted the second step in January, 1954, and the only

reports of what was involved were those published

in the newspapers. Negro parents living in these terri

tories were not notified by appellees regarding the change,

but transferred their children to the schools in question on

the basis of information provided in the newspapers. As

far as the teachers in those schools were concerned, they

were merely informed in the Spring of 1954 that their par

ticular schools would be integrated in September. Thus,

delay here cannot be based upon need for public orienta

tion.

It should be pointed out that of the 23 public elementary

•schools, there exists potential space for some additional 83

classrooms of which 16 such potential classrooms are in

the four schools to which the majority of the Negroes are

now assigned. No claim can be made that the school system

is overcrowded and unable to absorb the Negro and white

children under a reorganization plan. There is no discern-

able reason why all of the elementary schools of Topeka

have not been desegregated.

As is pointed out in the Brief for Petitioners on Fur

ther Reargument in Bolling v. Sharpe (No. 4, October

23

Term, 1954) the gradualist approach adopted by the Board

of Education in Washington, D. C., produced confusion,

hardship and unnecessary delay. Indeed, the operation of

the “ Corning Plan” has produced manifold problems in

school administration which could have been avoided if the

transition had been immediate. The argument that delay

is more sound educationally has been shown to be without

basis in fact in the operation of the District of Columbia

plan— so conclusively, in fact, that the time schedule has

been accelerated. The experience in the District argues

for immediate action.

To suggest that this Court may properly mold its

relief so as to serve whatever theories as to educational

policy may be in vogue is to confuse its function with that

of a school board, and to confuse the clear-cut constitutional

issue in these cases with the situation in which a school

board might find itself if it were unbound by constitutional

requirements and were addressing itself to the policy

problem of effecting desegregation in what seems to it the

most desirable way. But even if a judgment as to the

abstract desirability of gradualism could be supported by

evidence, it is outside the province of this Court to balance

the merely desirable against the adjudicated constitutional

rights of appellants. The Constitution has prescribed the

educational policy applicable to the issue tendered in this

case, and this Court has no power, under the guise of a

“ gradual” decree, to select another.

We submit that there are various necessary admini

strative factors which would make “ immediate” relief as

of tomorrow physically impossible. These include such

factors as need for redistricting and the redistribution of

teachers and pupils. Under the circumstances of this case,

the Court ’s mandate will probably come down in the middle

or near the close of the 1954 school term, and the decrees

of the courts of first instance could not be put into effect un

til September, 1955. Appellees would, therefore, have had

from May 17, 1954, to September, 1955, to make necessary

administrative changes.

24

I I .

Answering Question 5: If This Court Should De

cide to Permit an “ Effective Gradual Adjustment” from

Segregated School Systems to Systems Not Based on

Color Distinctions, It Should Not Formulate Detailed

Decrees but Should Remand These Cases to the Courts

of First Instance with Specific Directions to Complete

Desegregation by a Day Certain.

In 'answering Question 5, we are required to assume

that this Court “ will exercise its equity powers to permit

an effective gradual adjustment to be brought about from

existing segregated systems to a system not based on color

distinctions ’ ’ thereby refusing to hold that appellants were

entitled to decrees providing that, “ within the limits set

by normal geographic school districting, Negro children

should forthwith be admitted to schools of their choice.”

While we feel most strongly that this Court will not sub

ordinate appellants’ constitutional rights to immediate

relief to any plan for an “ effective gradual adjustment,”

we must nevertheless assume the contrary for the purpose

of answering Question 5.17

Question 5 assumes that there should be an “ effective

gradual adjustment” to a system of desegregated educa

17 “ 5. On the assumption on which question 4 (a ) and ( b) are

based, and assuming further that this Court will exercise its equity

powers to the end described in question 4(b) ,

“ (a) should this Court formulate detailed decrees in these cases;

“ (b) if so, what specific issues should the decrees reach;

“ ( c) should this Court appoint a special master to hear evidence

with a view to recommending specific terms for such decrees;

“ (d) should this Court remand to the courts of first instance with

directions to frame decrees in these cases, and if so, what general

directions should the decrees of this Court include and what pro

cedures should the courts of first instance follow in arriving at the

specific terms of more detailed decrees?”

25

tion. We have certain difficulties with this formulation.

We have already demonstrated that there is no reason to

believe that any form of gradualism will be more effective

than forthwith compliance. If, however, this Court deter

mines upon a gradual decree, we then urge that, as a mini

mum, certain safeguards must be embodied in that ‘ ‘ grad

ual” decree in order to render it as nearly “ effective” as

any decree can be which continues the injury being suf

fered by these appellants as a consequence of the unconsti

tutional practice here complained of.

Appellants assume that “ the great variety of local

conditions” , to which the Court referred in its May 17th

opinion, embraces only such educationally relevant factors

as variations in administrative organization, physical

facilities, school population and pupil redistribution, and

does not include such judicially non-cognizable factors as

need for community preparation, Ex Parte Endo, 323 U. S.

283, and threats of racial hostility and violence, Buchanan

v. War ley, 245 U. S. 60; Monk v. City of Birmingham., 185

F. 2d 859 (C. A. 5th 1950), cert, denied, 341 IT. S. 940.

Further we assume that the word “ effective” might be

so construed that a plan contemplating desegregation after

the lapse of many years could be called an “ effective

gradual adjustment.” For, whenever the change is in

fact made, it results in a desegregated system. We do not

understand that this type of adjustment would be “ effec

tive” within the meaning of Question 5 nor do we under

take to answer it in this framework. Rather, we assume

that under any circumstances, the question encompasses

due consideration for the constitutional rights of each of

these appellants and those presently in the class they repre

sent to be free from enforced racial segregation in public

education.

Ordinarily, the problem—the elimination of race as the

criterion of admission to public schools—by its very nature

would require only general dispositive directions by this

Court. Even if the Court decides that the adjustment to

26

nonsegregated systems is to be gradual, no elaborate

decree structure is essential at this stage of the proceed

ings. In neither event would appellants now ask this

Court, or any other court, to direct or supervise the details

of operation of the local school systems. In either event,

we would seek effective provisions assuring their opera

tion—forthwith in the one instance and eventually in the

other—in conformity with the Constitution.

These considerations suggest appellants’ answers to

Question 5. Briefly stated, this Court should not formulate

detailed decrees in these cases. It should not appoint a

special master to hear evidence with a view to recommend

ing specific terms for such decrees. It should remand these

cases to the courts of first instance with directions to frame

decrees incorporating certain provisions, hereinafter dis

cussed, that appellants believe are calculated to make them

as nearly effective as any gradual desegregation decree

can be. The courts of first instance need only follow normal

procedures in arriving at such additional provisions for

such decrees as circumstances may warrant.

Declaratory Provisions

This Court should reiterate in the clearest possible

language that segregation in public education is a denial

of the equal protection of the laws. It should order that the

decrees include a recital that constitutional and statutory

provisions, and administrative and judicial pronounce

ments, requiring or sanctioning segregated education afford

no basis for the continued maintenance of segregation in

public schools.

The important legal consequence of such declaratory

provisions would be to obviate the real or imagined dilemma

of some school officials who contend that, pending the

issuance of injunctions against the continuation of segre

gated education in their own systems, they are entitled

or even obliged to carry out state policies the invalidity of

27

which this Court has already declared. The dilemma is

well illustrated by the case of Steiner v. Simmons (Del. Sup.

Ct. No. 27, 1954), pending in the Delaware Supreme Court,

wherein plaintiffs are suing for readmission to M ilford’s

high school from which, on September 30, 1954, they were

expelled because they are Negroes. The Vice Chancellor

granted the requested mandatory injunction, finding that

plaintiffs had a constitutional right to readmission to

school. The Delaware Supreme Court, however, granted a

stay pending determination of the appeal on the basis of

its preliminary conclusion that “ there are serious questions

of law touching the existence of that legal right.” 18

This Court’s decision of May 17th put state authorities

on notice that thereafter they could not wTith impunity

18 Cf. Burr v. Bd. of School Commrs. of Baltimore, Superior

Court of Baltimore City, Oct. S, 1954 (unreported), in which case

Judge James K. Cullen stated in part:

In the instant case this Court is asked to issue a writ

of mandamus requiring these defendants, the School Board,

to continue with its policy of segregation. This Court finds

the Board of School Commissioners have exercised their dis

cretion legally and in accordance with a final and enforceable

holding and decision of the Supreme Court. Those cases were

undoubtedly argued before the Supreme Court fully, and the

views of every division of thought of our citizenry was un

doubtedly presented to the Court; but the Court has spoken.

Whether the individual agrees or disagrees with the finding,

he is bound thereby so long as it remains the law of the land.

The Court realizes the change and the difficulty some may

have accepting the reality or the inevitable from the stand

point of enforcement. W e live in a country where our rights

and liberties have been protected under a system of laws

which has withstood the test of time. W e must allow our

selves to be governed by those laws, realizing there are many

differences among our people. Respect for the law is of para

mount importance. The law must be accepted. W e must all

be forced to abide by it. W e can gain nothing by demonstra

tions of violence except sorrow and possible destructions.

abrogate the constitutional rights of American children

not to be segregated in public schools on the basis of race.

This type of recital in the decree should foreclose further

misunderstanding, real or pretended, of the principle of

law that continuation of racial segregation in public educa

tion is in direct violation of the Constitution— state con

stitutions, statutes, custom or usage requiring such segrega

tion to the contrary notwithstanding.

Time Provisions

We do not know what considerations may be presented

by appellees to warrant gradualism. But whatever these

considerations may be, appellants submit that any school

plan embracing gradualism must safeguard against the

gradual adjustment becoming an interminable one. There

fore, appellants respectfully urge that this Court’s opinion

and mandate also contain specific directions that any decree

to be entered by a district court shall specify (1) that the

process of desegregation be commenced immediately, (2)

that appellees be required to file periodic reports to the

courts of first instance, and (3) an outer time limit by

which desegregation must be completed.

Even cases involving gradual decrees have required

some amount of immediate compliance by the party under

an obligation to remedy his wrongs to the extent physically

possible.19 In Wisconsin v. Illinois, 281 U. S. 179, the

Court said:

It already has been decided that the defendants

are doing a wrong to the complainants, and that

they must stop it. They must find out a way at their

peril. We have only to consider what is possible

if the state of Illinois devotes all its powers to

19 See Wisconsin v. Illinois, 281 U. S. 179; Arizona Copper Co.

v. Gillespie, 230 U. S. 46; Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 206 U. S.

230; Westinghouse Air Brake Co. v. Great Northern Ry. Co., 86

Fed. 132 (C. C. S. D. N. Y. 1898).

29

dealing with an exigency to the magnitude of which

it seems not yet to have fully awaked. It can base

no defenses upon difficulties that it has itself created.

I f its Constitution stands in the way of prompt

action, it must amend it or yield to an authority

that is paramount to the state (p. 197).

# # #

1. On and after July 1, 1930,20 the defendants,

the state of Illinois and the sanitary district of

Chicago are enjoined from diverting any of the

waters of the Great Lakes-St, Lawrence system or

watershed through the Chicago drainage canal and

its auxiliary channels or otherwise in excess of an

annual average of 6,500 c.f.s. in addition to domestic

pumpage (p. 201).

Considering the normal time consumed before the

issuance of the mandate of this Court and the time for

submission and preparation of decrees by the courts of

first instance, decrees in these cases will not issue until

after February, 1955—after the normal mid-term in most

school systems. Thus, the school boards would have until

September, 1955— sixteen months after the May 17th

opinions—to change to a system not based on color dis

tinctions. This time could very well be considered as

necessarily incidental to any decision by this Court requir

ing “ forthwith” decrees by the courts of first instance.

Whatever the reasons for gradualism, there is no

reason to believe that the process of transition would be

more effective if further extended. Certainly, to indulge

school authorities until September 1, 1956, to achieve de

segregation would be generous in the extreme. Therefore,

we submit that if the Court decides to grant further time,

then the Court should direct that all decrees specify Sep

tember, 1956, as the outside date by which desegregation

must be accomplished. This would afford more than a year,

in excess of the time necessary for administrative changes,

20 This opinion was rendered April 30, 1930.

30

to review and modify decisions in the light of lessons

learned as these decisions are put into effect.

We submit that the decrees should contain no provision

for extension of the fixed limit, whatever date may be fixed.

Such a provision would be merely an invitation to pro

crastinate.21

We further urge this Court to make it plain that the

time for completion of the desegregation program will not

depend upon the success or failure of interim activities.

The decrees in the instant cases should accordingly provide

that in the event the school authorities should for any

reason fail to comply with the time limitation of the decree,

Negro children should then be immediately admitted to the

schools to which they apply.22

All states requiring segregated public education were

by the May 17th decision of this Court put upon notice

that segregated systems of public education are unconstitu

tional. A decision granting appellees time for gradual

adjustment should be so framed that no other state main

taining such a system is lulled into a period of inaction and

induced to merely await suit on the assumption that it will

then be granted the same period of time after such suit is

instituted.

21 A shm ore , T h e N egro and th e Schools, 70-71 (1954);

Culver, R acial D esegregation in E ducation in I n d ian a , 23 J.

N egro E d. 296-302 (1954).

22 See United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U. S. 106,

where this Court directed the allowance of a period of six months,

with leave to grant an additional sixty days if necessary, for activi

ties dissolving an illegal monopoly and recreating out of its com

ponents a new situation in harmony with the law, but further directed

that if within this period a legally harmonious condition was not

brought about, the lower court should give effect to the requirements

of the Sherman Act.

31

Conclusion

Much of the opposition to forthwith desegregation does

not truly rest on any theory that it is better to accom

plish it gradually. In considerable part, if indeed not in

the main, such opposition stems from a desire that de

segregation not be undertaken at all. In consideration of

the type of relief to be granted in any case, due considera

tion must be given to the character of the right to be pro

tected. Appellants here seek effective protection for

adjudicated constitutional rights which are personal and

present. Consideration of a plea for delay in enforcement

of such rights must be preceded by a showing of clear legal

precedent therefor and some public necessity of a gravity

never as yet demonstrated.

There are no applicable legal precedents justifying a

plea for delay. As a matter of fact, relevant legal prece

dents preclude a valid plea for delay. And, an analysis

of the non-legal materials relevant to the issue whether or

not relief should be delayed in these cases shows that the

process of gradual desegregation is at best no more effec

tive than immediate desegregation.

W herefore, we respectfully submit that this Court

should direct the issuance of decrees in each of these cases

requiring desegregation by no later than September of

1955.

CHARLES L. BLACK, JR„

ELWOOD H. CHISOLM,

WILLIAM T. COLEMAN, JR.,

CHARLES T. DUNCAN,

GEORGE E. C. HAYES,

LOREN MILLER,

WILLIAM R. MING, JR.,

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY,

JAMES M. NABRIT, JR.,

DAVID E. PIN SKY,

FRANK D. REEVES,

JOHN SCOTT,

JACK B. WEINSTEIN,

of Counsel.

HAROLD BOULWARE,

ROBERT L. CARTER,

JACK GREENBERG,

OLIVER W. HILL,

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

LOUIS L. REDDING,

SPOTTSWOOD W. ROBINSON, III,

CHARLES S. SCOTT,

Attorneys for Appellants in Nos. 1,

2, 3 and for Respondents in No. 5.

S upreme P rinting Co., I n c , 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3 - 2320