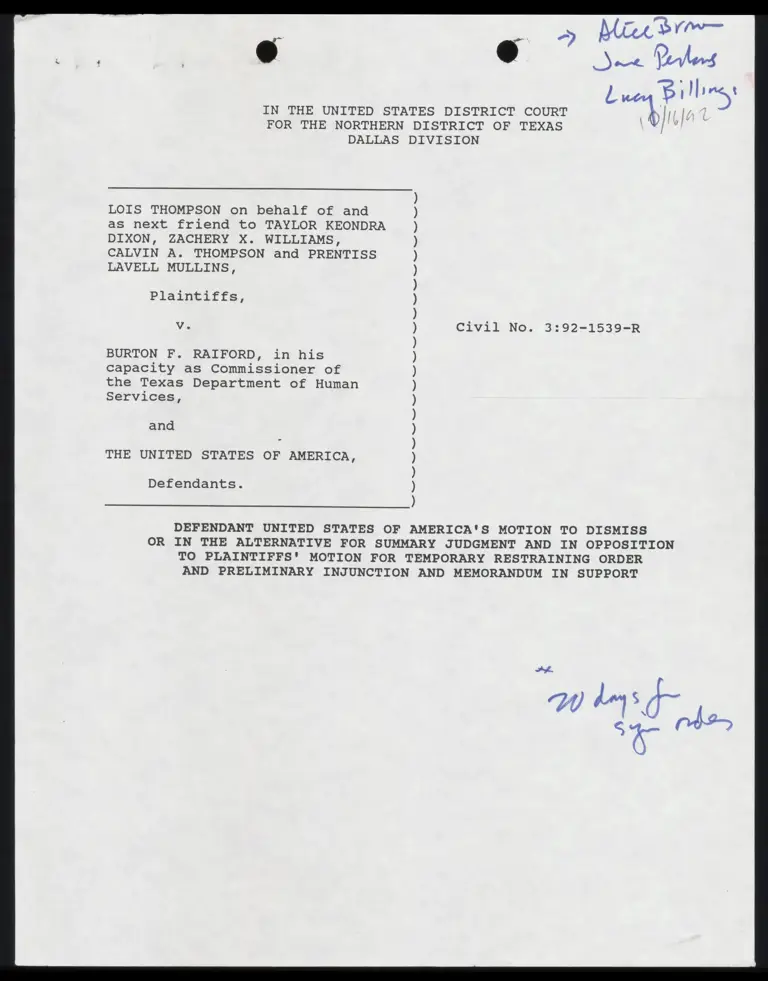

Defendant's Motion to Dismiss or for Summary Judgment and in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Temporary Restraining Order

Public Court Documents

October 16, 1992

75 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thompson v. Raiford Hardbacks. Defendant's Motion to Dismiss or for Summary Judgment and in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Temporary Restraining Order, 1992. ab57b479-5c40-f011-b4cb-0022482c18b0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d733d621-4959-4f5e-89d4-4a3fe6032c22/defendants-motion-to-dismiss-or-for-summary-judgment-and-in-opposition-to-plaintiffs-motion-for-temporary-restraining-order. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

| ® _ 3 Se Dior

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

LOIS THOMPSON on behalf of and

as next friend to TAYLOR KEONDRA

DIXON, ZACHERY X. WILLIAMS,

CALVIN A. THOMPSON and PRENTISS

LAVELL MULLINS,

Plaintiffs,

Vv. Civil No. 3:92-1539-R

BURTON F. RAIFORD, in his

capacity as Commissioner of

the Texas Department of Human

Services,

and

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Defendants.

N

o

N

a

l

N

a

s

N

a

t

l

N

a

l

N

a

l

N

w

N

a

N

l

N

w

N

a

S

u

n

l

a

a

a

?

a

a

’

“

a

n

t

S

u

?

“

?

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION TO DISMISS

OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION

TO PLAINTIFFS' MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER

AND PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT

| + 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHOR PIES. 0 ts vv a ie oa ite Saini ii

I. INTRODUCTION. os elie tle iy ai 0 ov iui wai via tag igi yh tis 1

Il. STATUTORY AND REGULATORY BACKGROUND vv iv eis oie a wien a 6

A. The Medicald Program iv «+ oc oi vc Tete in vie % oie oie 6

B. Early and Periodic Screening Diagnostic

And Treatment Program. «uc sv cis « + 0% aie sa 7

11. UNCONTROVERTED FACTS.» viv. « « 2 visite einiin oi vo range, 9

A. HCFA's Previous Actions Regarding Screening

Of Children For Elevated Blood levels . . . , + viv v's 9

B. The 199) CDC. Statement” . . . . vos v0 vy vrs 12

C. The September 1992 HCFA Guidelines . . . . uv 2 eo ov « '» 16

IV, “BRGUMENT ANDI BUTHORITIES . v vv ve vie lie athe ag aie ai 21

A. The Named Plaintiffs' Claims Should

Be Dismissed Because They Have Not

Suffered Any Injury And Thus Lack

SANGIN ENS SUB le vrs ves mise a ia a a ha 21

: ot Principles of Standing « + . 2. oy vin ivi Niteita 21

2. Plaintiffs Have Suffered No Injury As

A Result of The New HCFA Guidelines .'. . «. . . , 24

B. Plaintiffs' Complaint As To Defendant USA

Should Be Dismissed For Failure To State

Claim Upon Which Relief May Be Granted Or

Alternatively, Summary Judgment Should Be

Granted In Favor Of Defendant USA . . J + 8 guia, hy 28

1. The HCFA Guidelines Are Consistent

With The Medicaid Statute . . ot. Jiiip Jobe 28

2. The HCFA Guidelines Give States The

Option Of Using The EP Test For

"Low Risk" Children Only & =. u...iiv Ww woe ow Tul, 33

3. The HCFA Guidelines Are Consistent With

The 11991 CDC Statement . ... gies Lo Lay Onan no 32

- PS

J 3

C. Plaintiffs Have Failed To Satisfy The

Requirements For Temporary Injunctive Relief . . . . . 34

3. Standards for injunctive Relief . '. . . vv iu a 34

2. Plaintiffs Do Not Have A Substantial

Likelihood Of Success On The Merits . . . + oie . 36

3. There Is No Substantial Threat Of

Irreparable Injury If The Temporary

Relief Plaintiffs Seek From Defendant

USA IS NOC Granted « ov ov io vieciniv. on wiht igban di 37

4. The Threatened Injury To Plaintiffs

Does Not Outweigh Any Damage Preliminary

Relief Might Cause To Defendant USA And

PRE PUDIIC oo 3 oe eis is aie nin wail EE 38

Be Plaintiffs' Motion Should Also Be

Denied Because It Improperly Seeks

To Alter The Status QUO « voc =v vo vv devo 40

Vv. CONCLUSION te ts 8. Be ot i ie wee ea 42

- 41 =

¢ ¢

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASE(S): PAGE(S)

Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S. 737 (1983) o eile Ne cities Laine sie Bly 23g 2D

Allied Marketing Group, Inc. v. CDL Marketing, Inc.,

878 P.24.:806 (5th Cir. 1989) ies + wi Ye eet Sle, Ye yw 34, 35

Anderson v. Douglas & Lomason Co.,

835 Pe2@ 128 {SLR CIT. 1088) vo viv le vieiiv vinnie eee 36

Asarco v, Radish, 490 U.S, 605 (1989) + v vv «iv 0 vo vite vin ein 22

Atkins v, Rivera, 477 U.8.:184. (1986) . + « viv. iv vw Ww Nd Joa i'e

Brown v. Sibley, 630'F.2q 760 (Sth Cir. 1981) . iv « vivin sino 4927

Canal Authority of the State of Florida v.

Callaway, 489 F.2d 567 (53th Cir. FO74) ui oy vie esi ee Teak 3D

Chemical Mfrs. Ass'n v. Natural Resources

Defense Council, Inc., 470 U.S. 116 (1985) viva aie we ee 29

Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources

Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984) . . . .. + «ieee 28, 29

DFW Metro Line Servs. v. Southwestern Bell

Telephone Co., 901 F.24 1267 (5th Cir.),

cert. denied, U.S. r 211 S.Ct. 519: (1990)... + + vv ev + 35

Enterprise Int'l, Inc. v. Corporacion

Estatal Petrolera Ecuatoriana,

762 F.24 464 (5th Cir. 1585) nev vai we VEY eile 35,36

Ethyl Coyp. Vv. E.P.A., 541-F.24 1 (D.C. Cir.),

cert. denied, 426 U.S, 941 (19768) .. + +. 0 hii, JU00 a0

Ford Motor Credit Co. v. Milhollin,

444 8U.8.0. 555 (1080) Rl. om. . an. 0 ie ae ea i a a ia

Gladstone, Realtors v. Village of Bellwood,

44] VeSei 91 {1970 4 ie ite wis v Tv ov 0 viene eae Ry ie yity *

Harris vv. MeRae 4448 U.S. 207 (1980) i. i uns Ww dn otis a

Harris v. Wilters, 596 F.2d 678 (5th Cir. 3979 . . «4d &iww vie Siay

Holland America Ins. Co. Vv. Succession of Roy,

777 FP.2Q5992 ({SLtNECIT. 1IBBY 'v "vv vilei va 2 0 a wim Bene 35.37

- iii -

Ra J

Isquith v. Middle South Utilities, Inc.,

847 'P.24 186°(5th Cir. 1988)", . . « 's

Lewis v. Hegstrom, 767 F.2d 1371 (9th Cir. 1985)

Lopez v. Heckler, 725 F.2d 1489 (9th Cir. 1984),

vacated on other grounds, 105 S.Ct. 583 (1984)

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife,

U.S. y 112:8. Ct. 2130: (1992) v .»

Martin v. International Olympic Committee,

740 F.2d 670 (Oth Cir. 1984) ovis oi v « =

Martinez v. Matthews, 544 F.2d 1233 (5th Cir. 1976)

Mississippi Power & Light Co. v. United Gas

Pipe Line Co., 760 F.2d 618 (5th Cir. 1985)

Public Citizen v. United States Dep't of Justice,

491 U.S. 440 (1989) oie a ae ei WE Ca

Schlesinger v. Reservists To Stop The War,

418 U.S. 208 (1973) oe a a Te a

Schweiker v. Gray Panthers,

4830. CS, 34 {Y081Y >, JL. a

Schweiker v. Hogan, 457 U.S. 569 (1982)

Tanner Motor Livery, Ltd. v. Avis, Inc.,

316 F.24 804 (oth Cir.),

cert. denied, 375 U.S. 821 (1963)

Udall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965)

United States wv. Rutherford,

442 U.S, 544 (1979) i...

University of Texas v. Camenisch,

4510.8, 380 (1981): « vv v + 27%

Valley Forge College v. Americans United

for Separation of Church and State, Inc.,

454 U.S. 464 (1981) + 5. . i

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S5. 490.1(1975)

White 'v, Carlucci, 862 F.24 1209 (5th Cir. 1939)

Whitmore v. Arkansas, 495 U.S. 149 (1990)

- iy

o

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS

42 U.S.C. 1396

42 0.8.0. 8 13960: ..

42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a) (10) (A)

42 U.S.C. § 1396a(b)

42 U.8.C.a 8 139600, a0

42 C.F.R. § 1396d(a) (4) (B)

42 U.S.C. 13964(r) .

§

§

§

§

42 U.S.C. § 1396b(a)

§

§

§

§ 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a) (43) (A)

42 C.F.R. 440.40(b) .

MISCELLANEOUS

Conference Report, H.R. 101-386,

101 Cong. 1st Sess., p. 453

o

I.

INTRODUCTION

Plaintiffs, four children who are residents of West Dallas,

Texas, purport to represent a nationwide class of all Medicaid-

eligible children who are at risk for lead poisoning.! Plaintiffs

contend that they have not been given the appropriate blood lead level

assessment and treatment by the State of Texas. As to defendant USA,

they contend that guidelines issued recently by the Health Care

Financing Administration ("HCFA"), a component of the U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services ("HHS"), which became effective on

September 19, 1992, encourage states to test Medicaid-eligible

children for lead poisoning by using a less sensitive blood test (the

erythrocyte PEOtkpor HYP or "EP" test), which would not detect lead

levels at the threshold at which concern is recommended by the Centers

for Disease Control ("CDC"), rather than a more sensitive blood lead

test. The continued use of the EP test, according to plaintiffs,

contravenes a requirement of the Medicaid statute, 42 U.S.C. §

1396d(r), for "blood lead level assessment" and is inconsistent with

the October 1991 Statement of the CDC "Preventing Lead Poisoning in

! Plaintiffs initiated this action on or about July 29,

1992 against defendant Burton F. Raiford, in his official

capacity as Commissioner of the Texas Department of Human

Services. On or about August 6, 1992, plaintiffs filed their

first amended complaint. Defendant United States of America

("USA") has not been served with either the original complaint or

the first amended complaint. On or about September 10, 1592,

plaintiffs once again amended their complaint ("Complaint") to

include the USA as a defendant.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 1

o o«

Young Children: A Statement By The Centers For Disease Control" and

HHS' "Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Childhood Lead Poisoning"

issued in February 1991, both of which recognize that the lead

screening test of choice is now the blood lead test.

Plaintiffs seek a sweeping mandatory, preliminary and permanent

injunction to require that HCFA compel the states to use the blood

lead test as the sole screening test for lead poisoning.? They also

seek an order enjoining the federal government from supporting,

allowing or financing the states' continued use of the EP test as a

screening test for lead poisoning.’

2 It is only this form of relief which plaintiffs appear

not to seek as preliminary relief from defendant USA. In

addition, plaintiffs seek an order which would require HCFA to

issue guidelines requiring that states retest all Medicaid-

eligible children previously tested with the EP test with the

blood lead level test.

’ Plaintiffs also seek certain relief from defendant Burton

Raiford, Commissioner of the Texas Department of Human Services.

Specifically, plaintiffs seek a mandatory preliminary and

permanent injunction to require the State of Texas to use the

blood lead test as the sole screening device for lead poisoning

statewide, and enjoin the State from using the EP test.

Plaintiffs also seek an order requiring defendant Raiford to

declare West Dallas and other geographic areas in the State of

Texas high risk areas for children for lead poisoning, and notify

all EPSDT providers that eligible children residing in such

designated high risk geographic areas be given lead blood level

assessments. In addition, plaintiffs seek an order requiring

defendant Raiford to give effective notice and outreach of the

availability of blood lead screening and treatment to all EPSDT-

eligible children; and implement a case management program to

ensure that lead screening and treatment is provided for all

EPSDT-eligible children in accordance with the CDC guidelines.

Finally, plaintiffs seek an order requiring defendant Raiford to

retest, using the blood lead level test, all EPSDT-eligible

children previously tested with the EP test.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 2

o «

Defendant USA hereby opposes plaintiffs' Motion for Temporary

Restraining Order and Preliminary Injunction Against the U.S.A.

("Motion") and respectfully moves this Court for dismissal of

plaintiffs' Complaint in its entirety. As a threshold matter,

plaintiffs lack standing to bring this action. Plaintiffs suffer no

injury from the HCFA guidelines. The injury of which they complain -—

i.e., the State of Texas' alleged failure to perform a blood lead test

and appropriate lead poisoning intervention -- does not stem from the

challenged September 1992 HCFA guidelines. Indeed, those very

guidelines would require that plaintiffs receive the blood lead tests

they seek.? Granting the relief sought by plaintiffs from defendant

USA would not redress plaintiffs' injury and would offer plaintiffs no

relief not already offered by the very guidelines plaintiffs

challenge. Furthermore, requiring HCFA to issue guidelines which

mandate the states' use of the direct blood lead test (rather than the

EP test) in all cases would not accomplish plaintiffs' intended result

(i.e., universal use of the blood lead test), and may actually harm

the plaintiffs themselves. Given the states' current capacity

limitations for blood lead tests, requiring blood lead tests of all

Medicaid-eligible children, without assigning priority according to

whether the child 'is at "high risk" or "low risk," may result in

* In accordance with the challenged HCFA guidelines, the

four named plaintiffs would be deemed to be "high risk" for

significant lead exposure. The HCFA guidelines require that the

more sensitive blood lead test be administered for those children

determined to be "high risk."

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 3

. QC

significant delays in providing blood lead tests (and necessary

intervention) for "high risk" children such as plaintiffs.

Even if the Court finds that plaintiffs possess the requisite

standing to bring this suit, the case must be dismissed because

plaintiffs' claims are wholly lacking in merit. Contrary to

plaintiffs' allegations, the new HCFA guidelines do not contravene the

statutory requirement of the Medicaid statute, 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r),

for blood lead level assessment. Section 1396d(r) defines lead

screening as consisting of " (iv) laboratory tests (including lead

blood level assessment appropriate for age and risk factors)." On its

face, § 1396d(r) does not require "blood lead tests" as plaintiffs

contend and plaintiffs offer nothing to indicate that Congress

intended the term "lead blood level assessment" be to have the

restrictive (and highly technical) meaning they ascribe to it.

Plaintiffs' claims evidence a fundamental misunderstanding of the

new HCFA guidelines. There is no merit to plaintiffs' assertion that

HCFA's guidelines generally allow (indeed encourage) the use of the EP

test. The guidelines require the blood lead test for all children

determined to be at "high risk" of having elevated blood lead levels.

States continue to have the option to use the EP test as the initial

screening blood test only in those instances where, after a verbal

assessment, the EPSDT provider deems the child to be "low risk."’

> Thus, plaintiffs' suggestion that the guidelines were

intended to limit the federal government's financial obligations

is ludicrous.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 4

¢ o

HCFA has, however, encouraged the most widespread use of the blood

lead test and will share in the states' costs of screening all

children (including those assessed as "low risk"), through the use of

the blood lead test.S

In addition, the new HCFA guidelines are consistent with the 1991

CDC Statement. Plaintiffs' allegations to the contrary are

groundless. Indeed, the HCFA guidelines were developed in

consultation with the CDC, and the CDC itself has stated that the

guidelines are consistent with the 1991 CDC Statement. See

Declaration of Susan Binder, M.D. Chief, Lead Poisoning Prevention

Branch, CDC, attached hereto as Exhibit "B," at q 19.

Finally, for the same reasons that plaintiffs lack standing and

have failed to state a claim for which relief can be granted,

plaintiffs are not entitled to temporary injunctive relief. This is

all the more true because plaintiffs seek mandatory preliminary

injunctive relief which would alter the status quo, rather than

maintain it, by forcing HCFA to rescind its current EPSDT lead

screening guidelines and issue revised guidelines requiring states to

administer the blood lead test for all Medicaid-eligible children.

Thus, plaintiffs' Motion for temporary injunctive relief should be

denied.

® HCFA estimates that the majority of young Medicaid-

eligible children will be assessed as "high risk" due to their

physical living conditions. See Declaration of William McC.

Hiscock, attached hereto as Exhibit "A," at <q 14.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- §

Na eo

II.

STATUTORY AND REGULATORY BACKGROUND

A. The Medicaid Program

Title XIX of the Social Security Act, commonly known as Medicaid,

42 U.S.C. § 1396, establishes a jointly funded, cooperative federal-

state program designed to "enabl[e] each State, as far as practicable

under the conditions in such State," to furnish medical assistance to

eligible individuals. 42 U.S.C. § 1396. See Atkins v. Rivera, 477

U.S. 154, 165 (1986); Schweiker v. Hogan, 457 U.S. 569, 571 (1982);

Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297, 301 (1980). While the Medicaid program

is voluntary, states that choose to participate must submit a state

plan which fulfills all requirements imposed by the Medicaid statute

and its implementing regulations. 42 U.S.C. § 1396a. See Schweiker

Y. Gray Panthers, 453 U.S. 34, 36-37 (1981); Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S.

at 301. The Secretary is obligated to approve a state plan that meets

all federal requirements. 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(b).

Upon approval of the state plan, a state becomes entitled to

reimbursement by the federal government, termed "federal financial

participation" ("FFP") for a portion of its allowable payments to

hospitals, nursing homes, and other providers furnishing medical

assistance to eligible recipients. 42 U.S.C. § 1396b(a). Both the

state plans and the states' implementation of the plans are subject to

oversight by the Secretary to ensure continued compliance with the

federal requirements. 42 U.S.C. § 1396c.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 6

S s

The day-to-day administration of state Medicaid programs is

performed by the states, not by the federal government. Within the

broad framework of federal requirements and oversight, the states

operate their individual programs in accordance with state rules and

criteria that vary widely. "As long as a State complies with the

requirements of the Act, it has wide discretion in administering its

local program." lewis v. Hedstrom, 767 F.24 1371, 1373 (9th Cir.

1985) (citations omitted).

The Medicaid statute, however, does mandate that, at a minimum

participating states provide certain eligible groups with some

specific services. 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a) (10) (A). Apart from certain

statutory requirements, each state chooses the services (and payment

levels), and any additional groups (other than those mandated by the

Act) for which it will provide coverage. Id. The states also have

considerable discretion concerning the administrative and operating

procedures they will use to implement federal requirements. See

Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. at 301.

B. Early and Periodic Screening Diagnostic and Treatment Program

The Medicaid statute mandates that states provide Early and

Periodic Screening and Diagnostic and Treatment Program ("EPSDT")

services to Medicaid-eligible individuals under the age of 21. 42

U.S.C. §§ 1396a(a) (43) (A) and 1396d(a) (4) (B). In 1989, Congress

amended the Social Security Act to define EPSDT services when it

enacted the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 ("OBRA 89"),

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =- 7

_ 3 eo

Pub. L. 101-239,°103 Stat. 2106 (Dec. 19, 1989). Section 6403 of OBRA

89 provided the definition of EPSDT services by adding § 1396d(r) to

the Medicaid statute, effective April 1, 1990.’

In particular, section 6403 of OBRA 89, 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r),

defines screening services to include, at a minimum,

(1) a comprehensive health and developmental

history (including assessment of both physical

mental health development),

(11) a comprehensive unclothed physical exam,

(1ii) appropriate immunizations according to age

and health history,

(iv) laboratory tests (including lead blood level

assessment appropriate for age and risk factors),

and

(Vv) health education (including anticipatory

guidance).

(Emphasis added).

HCFA provides instructional and interpretive guidance to the

states through the "State Medicaid Manual," policy letters, and

memoranda (which are sometimes known as "Action Transmittals"). These

z The Secretary's regulation, promulgated before the 1989

amendment and found at 42 C.F.R. § 440.40(b), generally defines

EPSDT services, but does not define the services in detail.

OBRA 89, § 6403, now 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r), was derived from H.R.

3299, '§ 4213. Conference Report, H.R. 101-386, 101 Cong. 1st

Sess., p. 453. The Conference Report stated that the legislation

"codifies the current regulations on minimum components of EPSDT

screening and treatment, with minor changes," and provides that

"screening must include blood testing when appropriate, as well

as health education." (Emphasis supplied). The legislative

history furnishes no additional guidance regarding tests or

methods for screening.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 8

¢ &

materials reflect HCFA policy, and delineate how the states can comply

with federal Medicaid law, including federal EPSDT requirements. See

Declaration of William McC. Hiscock (the "Hiscock Declaration") at ¢

3, attached hereto as Exhibit "A." The EPSDT statutory provisions and

the regulations are interpreted by the Secretary in the State Medicaid

Manual.

III.

UNCONTROVERTED FACTS

A. HCFA's Previous Actions Regarding Screening Of Children For

Elevated Blood Levels

Since the early 1970's, long before Congress amended the EPSDT

statutory provisions to define EPSDT "screening" as explicitly

including blood lead level assessments "appropriate for age and risk

factors," HCFA consistently has advocated state screening of children

under the EPSDT program for elevated blood lead levels. Hiscock

Declaration at § 6 and HCFA State Medicaid Manual § 5-70-E (1)

(June 28, 1972) ("all children between ages of 1-6 should be

periodically screened for lead poisoning"), attached thereto as

Exhibit v2.0

HCFA has a longstanding commitment toward identifying and paying

for the costs of treating Medicaid-eligible children that are found to

have elevated blood levels. Hiscock Declaration at q 5.® To further

® This commitment is reflected, for example, in HCFA's 1978

policy decision to share in the states' costs of investigating

sources of lead poisoning as a Medicaid "preventive" service.

Hiscock Declaration at § 5 and HCFA Action Transmittal, 78-59

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 9

3 .

that goal, HCFA considers and relies upon the evolving state of

medical knowledge to form the basis of its EPSDT lead screening

guidelines. Hiscock Declaration at § 7. HCFA collects this medical

knowledge from various sources of medical expertise, including, most

importantly, the CDC's periodic statements on "Preventing Lead

Poisoning in Children." Hiscock Declaration at q 7.° HCFA also

considers input from other governmental agencies (such as the Maternal

and Child Health Bureau of the HHS Public Health Service) and from

nongovernmental entities, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics

and other public interest advocacy groups concerned with childhood

lead poisoning and prevention issues. Hiscock Declaration at q 7.

HCFA periodically revises its EPSDT screening guidelines to

reflect the advances. in scientific knowledge of the effects of

childhood lead poisoning. Hiscock Declaration at q 8. For instance,

in 1972 the State Medicaid Manual guidelines advised state

intervention and treatment of children when an EPSDT screen determined

a child's blood lead level to be greater than 80 micrograms per

deciliter ("mg/dL") of whole blood. Hiscock Declaration at q 8 and

Exhibit 2 attached thereto at 16. By 1988, HCFA revised its EPSDT

guidelines to require intervention when an EPSDT screen determined a

child's blood lead level to be greater than 30 ug/dL. Hiscock

(July 1, 1978) attached thereto as Exhibit "1."

The CDC has issued four policy statements with respect to

preventing childhood lead poisoning. Binder Declaration at q 5.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 10

¢ eo

Declaration at ¢ 8.

In 1985, CDC issued a policy statement with respect to lead level

testing in children. Binder Declaration at § 5. The 1985 CDC

Statement set forth the threshold for concern by pediatric health care

providers at a blood lead level of 25 ug/dL of whole blood. Binder

Declaration at § 5. The actions suggested by the 1985 CDC Statement

ranged from periodic retesting to chelation therapy treatments in more

severe cases of lead poisoning. Binder Declaration at § 5. In

addition, the 1985 CDC Statement recognized the EP test as the

screening test of choice for lead poisoning in children. Binder

Declaration at ¢q 5.

In 1990, consistent with the then current recommendations of the

1985 CDC Statement on "Preventing Lead Poisoning in Children," HCFA

required interventions when an EPSDT screen determined a child's

elevated blood lead level to be greater than 25 ug/dL. Hiscock

Declaration at § 8. Thus, in response to increased medical knowledge

of the effects of elevated blood lead levels, HCFA has continuously

lowered the blood lead level threshold at which it recommends or

requires concern and follow-up by Medicaid health care providers.

Hiscock Declaration at ¢q 8.

Similarly, HCFA periodically revises its EPSDT screening

guidelines to reflect available technological improvements in blood

lead level assessments. Hiscock Declaration at € 9. In 1972, the

agency did not establish any particular preferred test for EPSDT blood

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 11

o« ol

lead screening. Hiscock Declaration at § 9 and Exhibit "2" attached

thereto. In 1988, however, HCFA recommended the EP test as the

primary lead screening test under the EPSDT program. Hiscock

Declaration at q 9. (Rather than directly measuring lead in the

blood, the EP test indirectly assesses blood lead by detecting certain

protein indicators of elevated blood lead levels, i.e. erythrocyte

protoporphyrin. By contrast, the "blood lead test" directly measures

bios lead levels. Hiscock Declaration at § 9; Binder Declaration at

LA ) By April of 1990, HCFA's guidelines required, rather than

merely recommended, a blood lead test where a child was found to have

2 stlevatsg EP levels. Hiscock Declaration at § 9. Therefore, HCFA's

guidelines have not only grown increasingly more stringent in setting

blood lead level thresholds for concern, but they have also required

increasingly more sensitive blood testing where medical knowledge

indicated that such testing was appropriate. Hiscock Declaration at

q 9.

B. The 1991 CDC Statement

In or about 1989, the CDC chartered an advisory committee to

reevaluate a number of issues regarding childhood lead poisoning.

Binder Declaration at § 6. The work of that advisory committee

ultimately contributed substantially to the publication of the October

1991 CDC Statement, "Preventing Lead Poisoning in Young Children: A

Statement By The Centers For Disease Control" ("1991 CDC Statement").

Binder Declaration at § 6 and 1991 CDC Statement attached thereto as

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 12

¢ LJ

Exhibit "1." The advisory committee members, representative of a wide

variety of organizations and interests including physicians, state and

local boards of health, hospitals, organizations dealing with housing

and environmental issues, and a professional who represented

laboratory interests, see 1991 CDC Statement, attached as Exhibit "1"

of Binder Declaration at v, provided written advice and

recommendations to the CDC regarding childhood lead poisoning

prevention. Binder Declaration at q 6. Furthermore, the advisory

committee received expert advice from a group of official consultants,

who provided input for the advisory committee's written

recommendations. Binder Declaration at ¢q 6.

In addition to the written recommendations of the advisory

committee, CDC eoneidersd comments from medical groups, including the

American Academy of Pediatrics, representatives of companies who

produce or use lead, drug manufacturers, and childhood lead poisoning

prevention interest groups. Binder Declaration at § 7. Furthermore,

before publishing the 1991 CDC Statement, CDC provided HCFA with draft

materials for the 1991 CDC Statement, and received comments and

suggestions from HCFA. Binder Declaration at q 8; Hiscock Declaration

at 9 10. In addition, the CDC itself engaged in studies of childhood

lead poisoning, the results of which are reflected in the 1991 CDC

Statement. Binder Declaration at q 9.

The 1991 CDC Statement differs from the 1985 CDC Statement in

that it lowers the threshold for concern by pediatric health care

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 13

¢ ®

providers from the blood lead level of 25 ug/dL to 10 upg/dL. 1991 CDC

Statement at 1; Binder Declaration at ¢ 12. The actions suggested as

a result of such blood lead level results range from periodic

retesting to community prevention activities to chelation therapy

treatments in more severe cases of lead poisoning. 1991 CDC Statement

at 3; Binder Declaration at q 12. The focus of the 1991 CDC Statement

is on "primary prevention" -- i.e. preventing exposure to lead before

children become poisoned. 1991 CDC Statement at 3, 4; Binder

Declaration at q 12. The 1991 CDC Statement is intended to provide

guidance and recommendations, rather than mandates, to pediatric

health care providers, state and local public agencies for dealing

with childhood lead poisoning. Binder Declaration at q 11.

While the 1991 CDC Statement recognizes that the screening test

of choice is now the blood lead test, because the EP test is not

sensitive enough to identify children with blood lead levels below 25

ug/dL, the 1991 CDC Statement also acknowledges the need for a

transition period necessary to allow state health departments, health

care providers and laboratories to reach adequate capacity for

performing the blood lead test. 1991 CDC Statement at 41; Binder

Declaration at q 13. To reach adequate capacity will require the

acquisition of the necessary laboratory equipment and the hiring and

training of appropriate personnel. Binder Declaration at q 13.

During this transition or phase-in period to the use of the blood lead

test as the primary screening method, the 1991 CDC Statement

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 14

o ¢

recognizes that some programs will continue to use the EP test as a

screening test. 1991 CDC Statement at 41; Binder Declaration at § 13.

The 1991 CDC Statement further distinguishes between those

children to be considered high-risk and low-risk for high-dose

exposure to lead, and recommends the use of a series of questions

designed to ascertain the risk level of a child, as well as the type

and frequency of testing the child should receive. 1991 CDC Statement

at 42-44; Binder Declaration at q 15. In addition, the 1991 cDC

Statement recognizes that virtually all children are at risk for lead

poisoning, and as a result, a phase-in of universal screening using

the blood lead test for all children is recommended, except in

communities where large numbers or percentages of children have been

screened and found not to have lead poisoning. 1991 CDC Statement at

2; Binder Declaration at § 16. The 1991 CDC Statement recognizes that

full implementation of universal screening using the blood lead test

will require the availability of cheaper and easier-to-use methods of

blood lead measurement. 1991 CDC Statement at 2; Binder Declaration

at § 16. The 1991 CDC Statement further recognizes that "[c]hildren

at the highest risk should be given the highest priority for

screening." 1991 CDC Statement at 39; Binder Declaration at q 16.!°

© The CDC has rechartered a new advisory committee on

childhood lead poisoning prevention which is scheduled to meet in

or about Spring of 1993. Binder Declaration at q 17. At that

time, the new advisory committee will consider whether to amend

the current 1991 CDC Statement or issue a revised CDC report on

lead poisoning prevention. Binder Declaration at q 17.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 15

o ¢

C. The September 1992 HCFA Guidelines

HCFA's current EPSDT guidelines, which took effect on

September 19, 1992, continue the trend of revising HCFA policy to keep

up with the latest medical knowledge, and to incorporate increasing

technological advances in blood lead level assessments. Hiscock

Declaration at § 10. The new guidelines primarily are a response to

the 1991 CDC Statement. Hiscock Declaration at § 10. CDC officials

responsible for compiling the 1991 CDC Statement reviewed and

commented upon drafts of HCFA's new EPSDT lead screening guidelines.

Hiscock Declaration at q 10; Binder Declaration at 4 17. On

December 6, 1991, several HCFA agency officials met with a CDC

official who was one of the principal authors of the 1991 CDC

Statement, Dr. Sue Binder, to discuss CDC's views on HCFA's draft

EPSDT lead screening guidelines. Hiscock Declaration at q 10; Binder

Declaration at q 17. In response to CDC's comments, HCFA made various

revisions to the draft guidelines, and then circulated the revised

drafts to various other governmental and private entities for comment.

Hiscock Declaration at § 10. CDC expressed its view that the proposed

HCFA guidelines were consistent with the 1991 CDC Statement. Hiscock

Declaration at q 10; Binder Declaration at q 19.

Other entities that reviewed and commented on drafts of HCFA's

guidelines include the American Academy of Pediatrics; the Maternal

and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration

of the HHS Public Health Service; and an organization of the State

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 16

o« ¢

Medicaid Directors' Association known as the Medicaid Maternal and

Child Health Technical Advisory Group. Hiscock Declaration at § 11.

Thus, in revising its EPSDT lead screening guidelines, HCFA received

and considered input from an array of public and private organizations

concerned with childhood lead poisoning. Hiscock Declaration at q 11.

HCFA considered several factors in formulating its current EPSDT

lead screening guidelines. Hiscock Declaration at § 12. HCFA noted

that the 1991 CDC Statement recommends that health care providers

should first verbally assess a child's risk of having elevated blood

lead levels by asking a series of questions to determine the

likelihood of a child's exposure to lead sources. Hiscock Declaration

at € 12; Binder Declaration at § 15. The HCFA guidelines also require

such an assessment. HCFA State Medicaid Manual, attached to

Declaration of Michael M. Daniel in Support of Motion for TRO Against

the USA ("HCFA guidelines") at § 5123.2(a). Depending upon the

answers to questions in this "verbal ARsasaliont children are

considered to be either at "high risk" or "low risk" of being lead

poisoned. Hiscock Declaration at q 12.Y"

In revising its EPSDT lead screening guidelines on lead testing

for children, HCFA also took note that the 1991 CDC Statement

recommended lowering the blood lead level threshold for which concern

'I' Although the 1991 CDC Statement indicates that all

children are at risk for lead poisoning, CDC and HCFA have both

recognized that the highest priority should be reserved for those

children with the highest blood lead levels. 1991 CDC Statement

at 39; Hiscock Declaration at q 12; Binder Declaration at q 16.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS!

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 17

ol oo

and follow-up is recommended from 25 ug/dL of whole blood to 10 ug/dL,

1991 CDC statement at 1; Hiscock Declaration at ¢ 13, and acknowledged

that the 1991 CDC Statement recommends screening through the use of a

blood lead test rather than the EP test to assess blood lead levels

lower than 25 ug/dL. 1991 CDC Statement at 2; Hiscock Declaration at

q 13; Binder Declaration at § 13. However, HCFA also took into

account CDC's recognition of the need for a "transition" period to

move away from EP testing and move toward blood lead testing. Hiscock

Declaration at q 13; see Binder Declaration at q 13.

HCFA's revised guidelines incorporate CDC's methodology of using

verbal assessments to determine "risk categories" of a child's

likelihood of being exposed to dangerous levels of lead. HCFA

guidelines at § 5123.2(a); Hiscock Declaration at § 14. Consistent

with the 1991 CDC Statement, HCFA's guidelines bifurcate children into

"high risk" and "low risk" categories for likelihood of lead exposure

based upon the answers elicited in the verbal assessment. HCFA

guidelines at § 5123.2(a), (b); Hiscock Declaration at q 14; see

Binder Declaration at q 15. HCFA's guidelines mandate the most

sensitive blood lead testing process for children determined to be at

"high risk" of having elevated blood lead levels. HCFA guidelines at

§ 5123.2(c); Hiscock Declaration at q 14. This requirement is

consistent with the 1991 CDC Statement which recommends that the

highest priority be reserved for those children with the highest blood

lead levels. 1991 CDC Statement at 39; Hiscock Declaration at q 14;

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 18

¢ eo

see Binder Declaration at q 16. As a practical matter, HCFA believes

that the majority of EPSDT-eligible children will be deemed to be at

"high risk" for elevated blood lead levels due to the socioeconomic

conditions that often circumscribe where Medicaid recipients reside.

Hiscock Declaration at § 14 and Exhibit "3" attached thereto.

In addition, while HCFA's revised EPSDT guidelines stress that

blood lead testing is the preferred method for assessing blood lead

levels of children deemed to be at "low risk," the guidelines give

states the option of using either the blood lead test or the EP test

as the initial screen for "low risk" children during the transition

period. HCFA guidelines at Preamble; Hiscock Declaration at q 15 and

Exhibit "3" attached thereto. HCFA made this pragmatic policy choice

after considering coments from CDC and various organizations that

indicated that many localities simply do not currently have the

technology and/or the capacity available to universally conduct blood

lead testing for all Medicaid-eligible children, both "high risk" and

"low risk." Hiscock Declaration at q 15.

Both the 1991 CDC Statement and HCFA's guidelines recognize the

problems many communities face in moving away from EP testing and

toward blood lead testing. 1991 CDC Statement at 2, 41; HCFA

guidelines at Preamble; Hiscock Declaration at { 15 and Exhibit "3"

attached thereto; Binder Declaration at q 13. However, the federal

government (through HCFA), has encouraged the most widespread use of

the blood lead test and will share in the costs of screening "low

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 19

o« o

risk" children through the use of the blood lead test, if, as HCFA

recommends, states use this test. See HCFA guidelines at § 5123.2(c);

Hiscock Declaration at § 15 and Exhibit "3" attached thereto.

Even for this limited group of "low risk" children, states must

use the blood lead test in instances of elevated EP test results.

HCFA guidelines at § 5123.2(b); Hiscock Declaration at § 16. Where

subsequent verbal risk assessments suggest increased lead exposure for

children previously deemed "low risk," however, a blood lead test must

be performed. HCFA guidelines at § 5123.2(b); Hiscock Declaration at

q.16 17

Since EPSDT-eligible children must be "periodically" screened for

medical problems in accordance with a prescribed "periodicity

schedule" set by each state, each and every EPSDT child should be

evaluated for their risk of lead exposure at each periodic screening,

and accordingly receive the test appropriate for their particular risk

category. Hiscock Declaration at q 17.

HCFA will continue to revise and update its guidelines in

response to future guidance from the CDC and other organizations, and

2 In the situation where a "low risk" child continuously

resides in an area which a state or local health official

declares lead-free, HCFA's guidelines require only verbal risk

assessments of the child's likelihood of lead exposure, rather

than a blood lead test or an EP test. HCFA guidelines at §

5123.2 (a); Hiscock Declaration at q 17. Similar to other "low

risk" children, however, if the verbal assessment indicates

increased likelihood of lead exposure for this group of children,

then states must use either a blood lead test or the EP test to

determine blood lead levels. HCFA guidelines at § 5123.2{(b);

Hiscock Declaration at q 17.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 20

o J

as the technology necessary to perform the blood lead test becomes

more universally available. Hiscock Declaration at q 19.

Iv.

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES

A. The Named Plaintiffs' Claims Should Be Dismissed Because They

Have Not Suffered Any Injury And Thus Lack Standing To Sue

i. Principles of Standing

Article III of the Constitution confines the federal courts to

adjudicating actual "cases" or "controversies" as a means of properly

separating functions among the three branches of federal government.

Asarco v. Kadish, 490 U.S. 605, 613 (1989); Allen v. Wright, 468 U.S.

737, 750 (1984); Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United

for Separation of Church and State, Inc., 454 U.S. 464, 471 (1982);

Flast v. cohen, 392 U.S. 83, .94 (1967). See U.S. Const. art. III, §

2. The doctrines that surround the "case and controversy" requirement

therefore rest on the principles that govern an independent judiciary

in our democratic government. Allen, 468 U.S. at 750; Valley Forge,

454 U.S. at 471-72; Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 498 (1975).

Considering such principles, the Supreme Court in Allen stated

that "(t)he Art. III doctrine that requires a litigant to have

‘standing' to invoke the power of a federal court is perhaps the most

important of these doctrines." Allen, 468 U.S. at 750. And in fact,

"the standing inquiry requires careful judicial examination of a

complaint's allegations to ascertain whether the particular plaintiff

is entitled to an adjudication of the particular claims asserted."

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 21

Id. at 752.

To determine whether a particular plaintiff has standing to bring

an action, federal courts look to both the constitutional and

prudential limitations of the standing doctrine. See Allen, 468 U.S.

at 751; Valley Forge, 454 U.S. at 471. In order to have standing

under Article III of the Constitution, a plaintiff must satisfy a

three-prong test by alleging (1) an injury that is (2) fairly

traceable to the defendant's allegedly unlawful conduct, and (3)

likely to be redressed by the requested relief. Allen, 468 U.S. at

751; Valley Forge, 464 U.S. at 475. The Supreme Court has recently

explained this requirement in Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife:

First, the plaintiff must have suffered an "injury

in fact" -- an invasion of a legally-protected

interest which is (a) concrete and particularized

and (b) "actual or imminent, not 'conjectural' or

'hypothetical.'" Second, there must be a causal

connection between the injury and the conduct

complained of -- the injury has to be "fairly

. trace[able] to the challenged action of the

defendant, and not . . th[e] result [of] the

independent action of some third party not before

the court." Third, it must be "likely," as

opposed to merely "speculative," that the injury

will be "redressed by a favorable decision."

U.S. ¢ 112.8. Ct. 2130, 2136 (1992) (citations omitted).

The injury must be one that is distinct and palpable. Gladstone,

Realtors v., Village of Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91, 100 (1979); Warth v.

Seldin, 422 U.S. at 501. See also Allen, 468 U.S. at 752; Schlesinger

V. Reservists Comm. To Stop The War, 418 U.S. 208, 218 (1973).

The party who invokes federal jurisdiction bears the burden of

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 22

« o

establishing these elements. Lujan, 112 S. Ct. at 2136. Since these

elements are an indispensable part of plaintiff's case, "each element

must be supported in the same way as any other matter on which the

plaintiff bears the burden of proof" with particularized allegations

of fact. 1Id.; Warth, 422 U.S. at 501-02. If, after an opportunity to

provide such particularized allegations of fact, "standing does not

adequately appear from all materials of record, the complaint must be

dismissed." Warth, 422 U.S. at 501-02 (emphasis added). "A federal

court is powerless to create its own jurisdiction by embellishing

otherwise deficient allegations of standing." Whitmore v. Arkansas,

495 U.S. 149, 155-56 (1990).

As explained in detail below, plaintiffs do not meet the

requirements of standing to sue on their own behalf (or on behalf of

the class which they purport to represent). The injury of which they

complain does not stem from HCFA's issuance of the challenged

guidelines and cannot be redressed by rescission of these guidelines

or any other relief plaintiffs request from defendant USA.

Accordingly, the Court should therefore dismiss plaintiffs' Complaint

for lack of jurisdiction.

2. Plaintiffs Have Suffered No Injury As A Result of The New

HCFA Guidelines

The four named plaintiffs allege that they live near a battery

crushing and lead product fabrication plant located in West Dallas.

Complaint at q 24. Under the challenged HCFA guidelines, all

Medicaid-eligible children should be given a verbal assessment to

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 23

4 dg

determine whether they are at "high risk" or "low risk" for exposure

to dangerous lead levels. Plaintiffs! response to at least one of the

verbal assessment questions listed in the new HCFA guidelines -- "Does

your child live near a lead smelter, battery recycling plant, or other

industry likely to release lead . . . .?" -- should clearly be in the

affirmative. See HCFA guidelines at § 5123.2(a). Under the new HCFA

guidelines, "[i]f the answer to any question is positive, a child is

considered high risk for high doses of lead exposure." HCFA

guidelines at § 5123.2(b) (emphasis in original). As a result, all

four plaintiffs would be considered at "high risk" of having elevated

blood levels. Since the HCFA guidelines require that the most

sensitive blood lead test be administered for those children

determined to be at "high risk," plaintiffs should receive the blood

lead test they desire. See HCFA guidelines at 5-15; Hiscock

Declaration at q 14. These plaintiffs therefore will not be injured

by the application of the new HCFA guidelines. In fact, plaintiffs

will only benefit from their application. Not only is there no

"concrete and particularized" injury that these plaintiffs would

suffer as a result of the application of the new HCFA guidelines,

there is not even a threat of a "conjectural or hypothetical" injury

from those guidelines.

In addition, the requested injunctive relief would not redress

any alleged harm to plaintiffs. In order to establish redressability,

plaintiffs must show that "relief from the [alleged] injury [is]

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 24

o o

'likely' to follow from a favorable decision." Allen v. Wright, 468

U.S. at 751. Or, in the recent phraseology of the Supreme Court,

plaintiffs must show some "potential gain" from the relief requested.

Public Citizen v. United States Dep't of Justice, 491 U.S. 440, 451

(1989). Plaintiffs seek to enjoin defendant USA, both preliminarily

and permanently from supporting, allowing or financing the states' use

of the EP test as a screening test for lead poisoning, and to require

the federal defendant to mandate that states use the blood lead test

as the sole screening device for lead poisoning. They also seek to

enjoin HCFA's September 19, 1992 guidelines, and to require that HCFA

issue guidelines requiring that states retest all Medicaid-eligible

children previously tested with the EP test with the blood lead test.

Complaint at q 73. Yet the four named plaintiffs will fare no better

as a result of the granting of this extraordinary relief. The injury

of which they complain -- i.e., the State of Texas' alleged failure to

perform a blood lead test and appropriate lead poisoning intervention

—= cannot be redressed by enjoining the challenged September 1992 HCFA

guidelines. To the contrary, those guidelines require a blood lead

test and appropriate intervention in the circumstances alleged by

plaintiffs, and granting the relief sought by plaintiffs from

defendant USA would offer them no additional relief.

Furthermore, requiring HCFA to issue guidelines that require the

states' use of only the blood lead test would, in all likelihood, have

little or no practical effect. The HCFA guidelines take into account

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 25

oo 4

the requisite "transition" period needed for all states to move away

from EP testing and move toward universal blood lead testing for all

Medicaid-eligible children, while mandating that children at "high

risk" receive the blood lead test now. See HCFA guidelines at §

5123.2 (c); Hiscock Declaration at ¢ 13.

The states cannot immediately develop full capacity for blood

lead testing. Indeed, the relief plaintiffs seek may actually harm

them. In drafting its new EPSDT lead screening guidelines, HCFA

carefully considered the fact that many states and localities

currently do not have the technology and/or the capacity available to

conduct universal blood lead testing. See Hiscock Declaration at

qf 15. As a result, during the transition period to eventual universal

blood lead testing of all Medicaid-eligible children, HCFA has made a

conscious and pragmatic policy choice to allow states to continue use

of the EP test in limited circumstances. See Hiscock Declaration at

1 19 and Exhibit "3" attached thereto. While states are currently

undergoing the necessary transition to eventual universal blood lead

testing, HCFA has reserved the highest priority of testing using the

blood lead test for those children, like plaintiffs, who are assessed

as "high risk." See HCFA guidelines at § 5123.2(c); Hiscock

Declaration at q 14." Given the states' current capacity

3 plaintiffs, who should clearly receive the blood lead

test pursuant to the new HCFA guidelines, cannot claim to have

suffered the same injury as those "low risk" children for whom

the guidelines do not mandate use of that test. Once the Court

concludes that the proposed class representatives lack individual

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 26

o oe

limitations, requiring blood lead testing of all Medicaid-eligible

children, without assigning priority according to whether the child is

at "high risk" or "low risk," may result in significant delays in

blood lead testing (and necessary intervention) for "high risk"

children such as plaintiffs.!

B. Plaintiffs' Complaint As To Defendant USA Should Be Dismissed For

Failure To State Claim Upon Which Relief May Be Granted Or

Alternatively, Summary Judgment Should Be Granted In Favor Of

Defendant USA

Even if the Court finds that plaintiffs possess the requisite

standing to bring this suit, plaintiffs have nevertheless failed to

state a claim upon which relief may be granted, and their Complaint

should be dismissed pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure

standing, "the proper procedure . . . is to dismiss the

complaint, not to deny the class for inadequate representation or

to allow other class representatives to step forward." Brown Vv.

Sibley, 650 F.2d 760, 771 (5th Cir. 1981). Because standing is a

jurisdictional prerequisite, dismissal on standing grounds is to

take place before class certification issues are ever reached.

Id. As a result, plaintiffs' Complaint should be dismissed.

4 Finally, plaintiffs lack standing to seek an order which

would require HCFA to issue guidelines requiring that states

retest all Medicaid-eligible children previously tested with the

EP test with the blood lead level test. See Complaint at q 73.

Since EPSDT-eligible children must be periodically screened for

medical problems in accordance with a prescribed "periodicity

schedule" set by each state, each EPSDT child -- even those

previously tested with the EP test -- should be evaluated for

their risk of lead exposure under the new HCFA guidelines.

Hiscock Declaration at § 17. As a result, many Medicaid-eligible

children, including these plaintiffs, who previously received an

EP test under the old HCFA guidelines should now receive the

blood lead test in any event.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 27

_¢ o

12(b) (6). Alternatively, because there is no genuine issue as to any

material fact, summary judgment should be granted in favor of

defendant USA in accordance with Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56.

3. The HCFA Guidelines Are Consistent With The Medicaid Statute

The Supreme Court has "long recognized that considerable weight

should be accorded to an executive department's construction of a

statutory scheme it is entrusted to administer . . . ." Chevron,

U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.,, 467 uU.s. 837,

844 (1984) (citations omitted). See also Chemical Mfrs. Ass'n v.

Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 470 U.S. 116, 125 (1985) (a

statutory interpretation by an agency charged with applying the

statute is entitled to "considerable deference."). "To sustain the

[agency's] application of [a] statutory term, we need not find that

its construction is the only reasonable one, or even that it is the

> Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b) (6) allows courts

discretion as to whether to consider "matters outside the

pleading" such as affidavits, and courts may or may not elect to

convert a Rule 12(b) (6) motion into a motion for summary judgment

pursuant to Rule 56. See Isquith v. Middle South Utilities,

ing., 847 F.24 186, 193 -n.3 (5th Cir. 1938) (citing 5 C. Wright &

A. Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure § 1366 (1969)). As a

result, the Court has the discretion to exclude the Hiscock and

Binder declarations accompanying defendant USA's 12(b) (6) motion

and simply dismiss the action based on the Complaint and the

attachments thereto. Even if the Court, in its discretion,

chooses to consider the Hiscock and Binder declarations in

deciding the legal issues before it, thereby converting defendant

USA's motion to dismiss into a motion for summary judgment

pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56, summary judgment

should be granted in defendant's favor as there are no genuine

issues of material fact, and defendant USA is entitled to

judgment as a matter of law.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS’

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 28

_¢ &

result we would have reached had the question arisen in the first

instance in judicial proceedings." Udall Vv. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1, 16

(1965) (citations omitted); accord Chevron, 467 U.S. at 844-45; Ford

Motor Credit Co. v. Milhollin, 444 U.S. 555, 566 (1980); United States

v. Rutherford, 442 U.S. 544, 553-54 (1979).

Moreover, the Secretary of HHS need not prove that the method

chosen is the only, or even the best, means to accomplish the

regulatory objective, only that "the agency decision was rational and

based on consideration of the relevant factors." Ethyl Corp. Vv.

E.P.A., 541 F.2d 1, 36 (D.C. Cir.), cert. denied, 426 U.S. 941 (1976)

(citations omitted).

Contrary to plaintiffs' allegation, the new HCFA guidelines do

not contravene the statutory requirement of the Medicaid statute, 42

U.S.C. § 1396d(r), for lead testing. Section 1396d(r) defines lead

screening as consisting of " (iv) laboratory tests (including lead

blood level assessment appropriate for age and risk factors) ."

(Emphasis added). On its face, § 1396d(r) does not require "blood

lead tests" as plaintiffs contend and plaintiffs offer nothing to

indicate that Congress intended the phrase "lead blood level

assessment" to have the narrow, technical meaning plaintiffs ascribe

to it. See Complaint at q 70. In fact, the Conference Report to OBRA

89, § 6403, now 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(r), stated that the legislation

"codifies the current regulations on minimum components of EPSDT

screening and treatment, with minor changes," and provides that

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 29

_¢ &

"screening must include blood testing when appropriate, as well as

health education." Conference Report, H.R. 101-386, 101 Cong. 1st

Sess., p. 453 (emphasis supplied). The legislative history furnishes

no additional guidance regarding types of blood tests or other methods

for screening.!® As plaintiffs correctly point out, the Secretary of

HHS, the CDC and HCFA have all consistently recognized that the blood

lead test is the preferred mode for blood lead level assessments of

children. See Complaint at qq 63, 64 and 68; HHS' "Strategic Plan for

the Elimination of Childhood Lead Poisoning" (February 1991) at 23;

Binder Declaration at q 13 and Exhibit "1" attached thereto; Hiscock

Declaration at § 15; HCFA guidelines at Preamble. The blood lead test

is not the only test for assessing blood lead levels, however.

Moreover, Congress clearly stated that "age and risk factors"

should be taken into account in determining the blood lead level

assessment "appropriate" for each Medicaid-eligible child. HCFA's

approach under the new EPSDT lead screening guidelines takes into

account the "appropriate for age and risk factors" aspect of §

1396d(r). HCFA has followed the recommendations of the 1991 CDC

Statement and has established a framework within which a verbal

assessment is first given to determine what type of blood lead level

® It should also be noted that at the time Congress

considered and passed OBRA 89, CDC recommended the EP test as the

test of choice. Moreover, it would be anomalous, given the basic

structure and operation of the Medicaid program, which gives

states latitude in determining the services to be provided, for

Congress to tell states not only that children's lead levels must

be assessed, but also to mandate a particular test.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 30

& ®

assessment is most appropriate in light of such factors as age and

risk for exposure to lead. See Hiscock Declaration at q 14; Binder

Declaration at q 15. Therefore, the challenged HCFA guidelines do not

contravene the Medicaid Act.

2. The HCFA Guidelines Give States The Option Of Using The EP

Test For "Low Risk" Children Only

Plaintiffs contend that the HCFA guidelines, which became

effective on September 19, 1992, continue to sanction the use of the

EP test as the primary screening test for lead poisoning in young

children throughout the country. Complaint at § 62. In drawing this

erroneous conclusion, plaintiffs ignore the plain language of the new

HCFA guidelines as well as their context. As explained in the Hiscock

Declaration, under the guidelines, the first step for an EPSDT

provider is to conduct a verbal assessment for each Medicaid-eligible

child in order to determine "risk categories" (i.e., a child's

likelihood of being exposed to dangerous levels of lead). Hiscock

Declaration at q 14. If even one of the questions enumerated in the

guidelines is answered in the affirmative, that child is automatically

considered to be "high risk." See HCFA guidelines at § 5123.2 (b).

HCFA's guidelines require the blood lead test for children determined

to be at "high risk" of having elevated blood lead levels. HCFA

guidelines at § 5123.2(c); Hiscock Declaration at q 14. If all verbal

assessment questions are answered in the negative, that child is

considered to be "low risk," and the EPSDT provider is then given the

option to administer the blood lead test or the EP test. HCFA

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 31

OC o

guidelines at Preamble; Hiscock Declaration at ff 15. As a result,

states continue to have the option to use the EP test as the initial

blood lead level screening test only in those instances where, after a

verbal assessment, the EPSDT provider deems the child to be "low

risk," and further determines to administer the EP test rather than

the blood lead level test. See HCFA guidelines at Preamble; Hiscock

Declaration at q 15."

3. The HCFA Guidelines Are Consistent With The 1991 CDC

Statement

Contrary to plaintiffs' contention, the new HCFA guidelines are

consistent with the 1991 CDC Statement. While the 1991 CDC Statement

recognizes that the lead screening test of choice is now the blood

lead test because the EP test is not sensitive enough to identify

children with blood lead levels below 25 ug/dL, see Complaint at q 68,

plaintiffs conveniently fail to mention the portion of the 1991 CDC

Statement which acknowledges the need for a transition period until

the recommendations of the 1991 CDC Statement can be implemented

fully. 1991 CDC Statement at 41; Binder Declaration at q 13 and

Exhibit "1" attached thereto. The 1991 CDC Statement recognizes that

this transition period is necessary to allow state health departments,

7 The federal government will nevertheless share in the

states' costs of screening "low risk" children through the use of

the blood lead test, and has encouraged states to use the more

sensitive test in all cases, as well as to increase their blood

lead testing capacities so that they will eventually be able to

perform universal blood lead testing for all Medicaid-eligible

children. See Hiscock Declaration at § 19 and HCFA letter to

State Medicaid Directors attached as Exhibit "3" thereto.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 32

OC 6

health care providers and laboratories to reach adequate capacity for

performing the blood lead level test, which will require the

acquisition of the necessary laboratory equipment and the hiring and

training of appropriate personnel. 1991 CDC Statement at 41; Binder

Declaration at ¢ 13.

The 1991 CDC Statement itself recognizes that during this

transition or phase-in period which should culminate in the eventual

use of the blood lead test as the primary screening method, some

programs will continue to use the EP test as a screening test. 1991

CDC Statement at 41; Binder Declaration at q 13. Recognizing the need

for this transition period, and completely consistent with the 1991

CDC Statement, HCFA has given states the option to use the EP test in

certain circumstances (i.e., for "low risk" children only) under the

new HCFA guidelines. See HCFA guidelines at Preamble. The basic

premise of plaintiffs' Complaint -- that the HCFA guidelines ignore or

are inconsistent with the 1991 CDC Statement -- is simply wrong.'

Indeed, the HCFA guidelines were developed in consultation with the

CDC and the CDC itself has stated that the guidelines are consistent

with the 1991 CDC Statement. ee Binder Declaration at q 19.7

® In any event, plaintiffs could not present a claim for

relief based on the allegations (even if true) that the HCFA

guidelines are inconsistent with the 1991 CDC Statement. That

statement is not binding on HCFA, or for that matter, or anyone.

It is merely a recommendation. See Binder Declaration at ¢ 11.

' In addition, the HCFA guidelines are fully consistent

with HHS' "Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Childhood Lead

Poisoning" issued in February 1991. Both recognize that the EP

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT =-- 33

OC &«

C. Plaintiffs Have Failed To Satisfy The Requirements For Temporary

Injunctive Relief

For the same reasons that plaintiffs lack standing and have

failed to state a claim for which relief can be granted, and for

additional reasons as well, plaintiffs are not entitled to temporary

injunctive relief. Plaintiffs' request for injunctive relief should

therefore be denied.

1. Standards for Injunctive Relief

As the Fifth Circuit has recognized, preliminary injunctive

relief is an extraordinary and drastic remedy, and should be granted

only when the movant, by a clear showing, carries the burden of

persuasion. Allied Marketing Group, Inc. v. CDL Marketing, Inc., 878

F.2d 806, 809 (5th Cir. 1929); White v. Carlucci, 862 F.24 1209, 1211

(5th Cir. 1989); Holland America Ins. Co. Vv. Succession of Roy, 777

F.24:992, 997 (5th Cir. 1985); Enterprise Int'l. Inc. v. Corporacion

Estatal Petrolera Ecuatoriana, 762 F.2d 464, 472 (5th Cir. 1985).

Accordingly, "[t]he decision to grant a preliminary injunction is the

exception rather than the rule." Mississippi Power & Light Co.

v. United Gas Pipe Line Co., 760 F.2d 618, 621 (5th Cir. 1985). In

order to obtain the extraordinary remedy of temporary injunctive

relief, the movant must "by a clear showing, carr([y] the burden of

persuasion," White, 862 F.2d at 1211, as to four elements. The movant

test is not a useful screening test for blood lead levels below

25 pug/dL, and that blood lead testing is the preferred method for

lead screening of all Medicaid-eligible children. See HHS report

at 23, 40; HCFA guidelines at Preamble.

DEFENDANT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA'S MOTION

TO DISMISS OR IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT AND IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND

PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION AND MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT -- 34

& &®

must demonstrate

(1) a substantial likelihood of success on the

merits exists;

(2) a substantial threat of irreparable injury

exists if the preliminary relief is not granted;

(3) that the threatened injury to the movant

outweighs any damage preliminary relief might

cause to the opponent; and

(4) that the relief sought will not disserve the

public interest.

DFW Metro Line Servs. v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 901 F.2d

1267, 1269 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, U.s. , 111 8, CL. E519

(1990); Allied Marketing, 878 F.2d at 809; Enterprise Int'l, 762 F.2d

at 471; Canal Authority of the State of Florida v. Callaway, 489 F.2d

567, 572-73 (5th Cir: 1974). "'[T]lhe movant has a heavy burden of

persuading the district court that all four elements are satisfied, '"

and "if the movant does not succeed in carrying its burden on any one

of the four prerequisites," preliminary relief may not be granted.

Enterprise Int'l, 762 F.2d at 472 (citations omitted). Accord

Anderson v. Douglas & lomason Co., 835 F.2d 123, 133 (5th Cir. 1988).