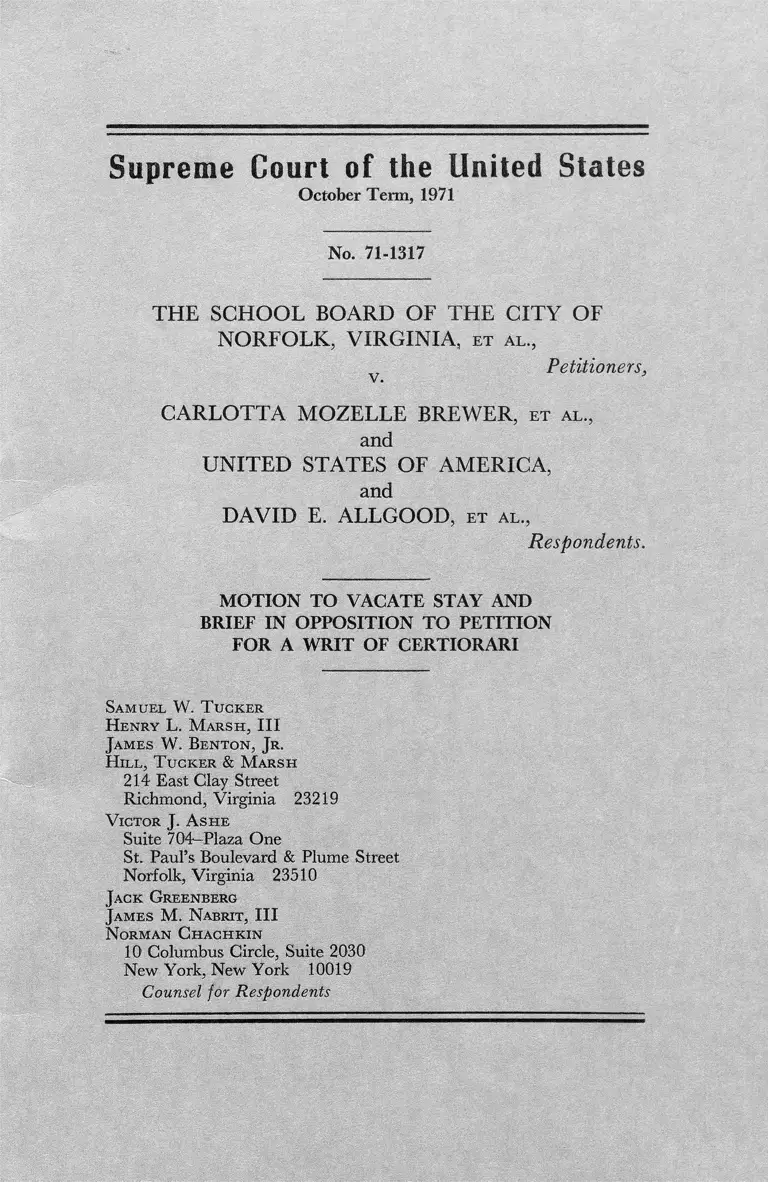

City of Norfolk, VA School Board v. Brewer Motion to Vacate Stay and Brief in Opposition to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Norfolk, VA School Board v. Brewer Motion to Vacate Stay and Brief in Opposition to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1971. e13705ae-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d76222cf-046a-4a34-b83a-817454a26684/city-of-norfolk-va-school-board-v-brewer-motion-to-vacate-stay-and-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 71-1317

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, e t a l .,

Petitioners,

CARLO TTA MOZELLE BREWER, et a l .,

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

and

DAVID E. ALLGOOD, et a l .,

Respondents.

M O TIO N TO VACATE STAY AND

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION

FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI

Sa m u el W. T u ck er

H e n r y L. M a r s h , III

Ja m e s W. Be n t o n , Jr.

H ill , T u ck er & M arsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

V ictor J. A sh e

Suite 704—Plaza One

St. Paul’s Boulevard & Plume Street

Norfolk, Virginia 23510

Ja ck G reenberg

Jam es M. N abrit, III

N orm an C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Respondents

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 71-1317

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, et a l .,

Petitioners,

v.

CARLOTTA MOZELLE BREWER, et a l .,

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

and

DAVID E. ALLGOOD, et a l .,

Respondents.

M O TIO N TO VACATE STAY

Respondents Carlotta Mozelle Brewer and others move

the Court to vacate the stay of the mandate of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit dated March

7, 1972 by which the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia at Norfolk is directed “ to amend

the plan of desegregation for the defendant school district

by requiring the school district to provide, either by a bus

system of its own or by an acceptable arrangement with the

private bus system now operating in the school district, free

transportation for all students of the school system assigned

to schools located beyond reasonable walking distances of

2

their homes.” By order of the Court of Appeals filed x\pril 3,

1972, the mandate was “ stayed until April 18, 1972, in order

to permit the defendants to apply to the Supreme Court for

a writ of certiorari, or to apply to that Court for a stay.”

The petition for a writ of certiorari was docketed on the

13th day of April, 1971.

In support of this motion, the respondents show:

I

1. If the stay of the mandate will be vacated, the district

court, in compliance with the spirit of Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969), may join

the Council of the City of Norfolk as a party defendant and

require the Council and the School Board to make plans,

with increased appropriations as necessary, for providing

free transportation for the school children without which, as

the Court of Appeals has noted, reassignment for purposes

of desegregation “ becomes a futile gesture and . . . a cruel

hoax.” Inasmuch as approximately ninety days are required

between order and delivery of school buses (Bradley v.

School Board of the City of Richmond, 324 F.Supp. 456,

459 (E.D. Va. 1971)), the courts should require the School

Board to promptly decide whether it will transport children

by school buses or, if not, by what practical means free

transportation will be provided. In either event, and to

avoid diminution of the quality of the educational program

(Code of Virginia, 1950, § 22-126.1), the cost should be

ascertained and included in the city’s budget for the fiscal

year which will begin July 1, 1972 (Code of Virginia, 1950,

§ 15.1-160 et seq.).

2. No injury will be occasioned the School Board or the

Council if the stay should be vacated. Even if the district

3

court should require the purchase of school buses and this

Court should later hold that Norfolk has no obligation to

furnish free transportation to school children under the cir

cumstances of this case, there is a growing national demand

for school buses which insures that such properties can be

resold with minimal financial loss.

3. In the words of the Court of Appeals in its March 7,

1972 opinion in this case at footnote 6, the respondents

allege: “ The District Court found the cost of installing and

operating a transportation system by the school district to

be $3,600,000. O f this sum, however, approximately $3,-

000,000 represented capital outlays, covering purchases of

buses and the acquisition and equipping of service yards.

These expenditures are normally funded and are not con

sidered an operating expense. The annual operating expense

of the bus system for the school district was fixed at about

$600,000, of which 47 per cent would be reimbursable by the

State. It would seem reasonable to assume that an annual

operating budget of $600,000 by the district (supplemented

as it would be with State aid) would cover the operating

costs of the system and provide adequately for normal

amortization of the capital expenditures required for the

purchase of buses and for the acquisition of service facilities.

Such an expenditure from a school budget of over 35 million

dollars would be in line with what was considered reasonable

in Swann, where an increased annual operating expense of

$1,000,000, imposed on a total school budget of $66,000,000,

was held reasonable.”

4. Judicial requirement that the Council and School

Board make plans for providing free transportation for

school children will not even occasion undue inconvenience

but will merely insure good faith performance of the under

taking which the School Board indicated when, in its appli

4

cation to the Court of Appeals for the stay, it represented:

“ The appropriate officials of the School Board and the City

of Norfolk are in the process of investigating feasible alterna

tive methods of providing public transportation for the

school children and the general public of the City of Nor

folk, including the financing thereof.”

II

5. If the stay of the mandate will continue in force, the

defendant School Board and the Council of the City of

Norfolk (which by reason of the School Board’s objections

has not been made a party hereto) will be free from judicial

compulsion to provide transportation for the school children

during the 1972-73 school session or to make reasonable

plans for such; and thousands of Norfolk school children and

their parents, including members of the plaintiff class, will

be financially disadvantaged without prospect of recovery

or, even worse, children will be required to forego school

attendance during the 1972-73 school session by reason of

their inability to pay the cost of transportation to distant

schools to which they have been assigned pursuant to the

constitutional command to desegregate schools.

6. Under the desegregation plan for Norfolk’s schools,

submitted and approved pursuant to this Court’s decisions in

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1 (1971) and companion cases, an estimated 24,000

school children are assigned to schools which are beyond

walking distance from their respective homes; some of the

distances being as much as nine miles. Norfolk’s public

schools have an approximate enrollment of 50,000, more

than 16,000 of whom are from low income families as are

most of the plaintiff class.

5

7. During 1971-72, student bus fares in Norfolk were

increased from 12j/i> cents to 17 /2 cents or from $45 to $63

a year. A predictable result of such fare increase was that

more children of low income families would have to forego

school attendance because of their inability to pay for trans

portation.

8. If the stay should continue in effect and this Court

should ultimately affirm the judgment of the Court of Ap

peals, thousands of Norfolk school children from families

with low income including many children of the plaintiff

class, will have been irreparably injured by the wrongful

denial of the means to get to the distant schools to which

they were assigned pursuant to the desegregation plan. The

reward for their quest for equal educational opportunity will

have been, in a very realistic sense, a gross denial of any

educational opportunity.

Sam u el W. T ucker

Of Counsel for Carlotta Mozelle

Brewer, et al., Respondents

Sam u el W. T ucker

H enry L. M a r s h , III

Jam es W. Be n t o n , Jr .

H ill , T u ck er & M arsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

V ictor J. A sh e

Suite 704^Plaza One

St. Paul’s Boulevard and Plume Street

Norfolk, Virginia 23510

Ja ck G reenberg

Jam es M. N abrit, III

N orman C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Carlotta Mozelle Brewer,

et al., Respondents

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION

FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Earlier A spects of the Case .................................. ........................ 1

Q uestions Presented ........................................................................ 2

Statement of Additional Facts ...... ............................................... 3

R easons for Denying the Writ ......................................... ........... 4

I. Free Pupil Transportation ...................... ........................ 4

A. Free Transportation, As Mandated By The Court

Below, Is Clearly Required By Prior Decisions O f This

Court ................................................................................. 4

B. The Apparent Conflict Between Circuits, If Real, Is

Insignificant ................................................................. 7

II. Allowance Of Counsel Fees To Plaintiffs........................... 9

III. The Pendency Of The Instant Petition, Coupled With

The Stay Granted Pursuant To F.R.A.P. 41(B), Shield

The School Board From Its Responsibility To Order

School Buses Now ................................................................. 11

Conclusion ................................................... 12

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, 321 F.2d 494

(4th Cir. 1963) ........... 9

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 324 F. Supp.

456 (E.D. Va. 1971) ......................................................................... 11

Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, Virginia, 434 F.2d 408 1

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....6, 10

Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County, Virginia, 327

F.2d 655 (4th Cir. 1964) 9

Page

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School District, 369

F,2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966) ............ ........................ ........................... 10

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School District, 449

F.2d 493 (8th Cir. 1971) ................................................ ............7, 9

Griffin v. Board of Supervisors of Prince Edward County, 339 F.2d

486 (4th Cir. 1964) ......................................................................... 9

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218

(1964) .......................................... ..................................................... 6

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education, 418 F.2d 1040 ( 4th

Cir. 1969) ........................................................................................ - 10

School Board of Norfolk, Virginia v. Brewer, 399 U.S. 929 ....... .. 2

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971) .......................................................................................... 4, 5, 7

United States of America v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, et a l , ..... F.2d ...... (5th Cir. No. 71-2773) ................. 8, 9

Other Authority-

Constitution of Virginia (1971) Article VIII, §§ 1, 3 .................... 6

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 71-1317

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, et a l .,

Petitioners,

v.

CARLOTTA MOZELLE BREWER, et a l .,

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

and

DAVID E. ALLGOOD, et a l .,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION

FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI

EARLIER ASPECTS OF THE CASE

On June 29, 1970 this Court denied the school board’s

petition for writ of certiorari to the decision of the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit (Brewer v. School Board of

City of Norfolk, Virginia, 434 F.2d 408) which, inter alia,

directed that “ [w]ith respect to elementary and junior high

schools, the board should explore reasonable methods of

desegregation, including rezoning, pairing, grouping, school

2

consolidation, and transportation” (Id at 412). School Board

of Norfolk, Virginia v. Brewer, 399 U.S. 929.

On or about September 3, 1971 the school board made

application to the Chief Justice for a stay of the mandate of

the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit which had va

cated the district court’s August 25, 1971 stay of its July 28,

1971 order requiring transportation of pupils to effect school

desegregation; the application having been based on a claim

that Executive Order No. 11615, dated August 15, 1971

prohibited the Virginia Transit Company’s anticipated fare

increase without which the company would not continue to

transport children at reduced fares. The school board then

asserted: “ The only alternative method of obtaining the

necessary transportation is for the School Board to establish

a school bus system.” The application for a stay was denied

on September 5, 1971. School Board of Norfolk, Virginia v.

Carlotta Mozelle Brewer, et al., and United States of Amer

ica, No............ October Term, 1971.

On or about September 27, 1971 certain “ white defend-

ant-intervenors” made application to the Chief Justice for a

stay of the District Court’s July 28, 1971 order requiring

transportation of pupils to effect school desegregation. The

application was denied. David E. Allgood, etc., et al. v. Car

lotta Mozelle Brewer et al., No..............October Term, 1971.

The history of sixteen years of active litigation of this case

in the lower courts is set forth in the appendix to this brief.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The petitioners’ statement of questions presented makes

certain assumptions which the respondents are unwilling to

admit. Hence, we restate those questions, viz:

1. Whether this school board must defray costs of all

transportation which is necessary to the disestablishment of

3

racial segregation in the public schools and to the mainte

nance of equality of benefits accorded students similarly situ

ated.

2. Whether an appellate court may mandate an award of

counsel fees to successful plaintiffs in a school desegregation

case.

3. Whether, by virtue of the stay granted pursuant to

F.R.A.P. 41 (b ), the pendency of the instant petition will

absolve the school board of its responsibility to order school

buses in sufficient time to furnish transportation during the

1972-73 session.

STATEMENT OF ADDITIONAL FACTS

The board estimates that 24,000 pupils will require trans

portation. Norfolk’s public schools have an approximate en

rollment of 50,000, more than 16,000 of whom are in low

income families.

Since 1942 Virginia has offered assistance to local school

district transportation programs covering maintenance,

operating expenditures, bus replacement costs, etc. (25 Tr.

60, 74). Up to 100% of operating expenditures qualify for

reimbursement upon the application of a school district.

For many years, the Virginia Transit Company has oper

ated special school busses in conjunction with the school

board. These buses are routed to pick up students near their

homes each morning and transport them to the school of

their assignment. Over the years, the City of Norfolk has

subsidized the cost of transporting more than 8,000 students

daily, thus permitting them to ride at one-half of the normal

fare.

“ The District Court found the cost of installing and oper

ating a transportation system by the school district to be

4

$3,600,000. O f this sum, however, approximately $3,000,000

represented capital outlays, covering purchases of buses and

the acquisition and equipping of service yards. These ex

penditures are normally funded and are not considered an

operating expense. The annual operating expense of the bus

system for the school district was fixed at about $600,000,

of which 47 per cent would be reimbursable by the State. It

would seem reasonable to assume that an annual operating

budget of $600,000 by the district (supplemented as it would

be with State aid) would cover the operating costs of the

system and provide adequately for normal amortization of

the capital expenditures required for the purchase of buses

and for the acquisition of service facilities. Such an expendi

ture from a school budget of over 35 million dollars would

be in line with what was considered reasonable in Swann,

where an increased annual operating expense of $1,000,000,

imposed on a total school budget of $66,000,000, was held

reasonable” (Slip Op. footnote 6).

REASONS FOR DENYING THE W RIT

I.

Free Pupil Transportation

A.

F ree T r a n s p o r t a t io n , A s M a n d a te d B y T h e C o u r t

B e l o w , I s C l e a r l y R eq u ired By P rior D ecisio n s

O f T h is C o u r t .

By necessary implication, this Court has shown that this

school board must furnish free transportation. In affirming

the district court’s order in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 26-27 (1971), and with

specific reference to an optional majority-to-minority trans

fer provision, this Court indicated:

5

“ In order to be effective, such a transfer arrangement

must grant the transferring student free transportation

[emphasis supplied] and space must be made available

in the school to which he desires to move. Cf. Ellis v.

Board of Public Instruction, 423 F.2d 203, 206 (C.A.

5 1970). The court orders in this and the companion

Davis case now provide such an option.”

It should go without saying that the school board has at

least an equal duty to transport students whom it assigns to

distant schools to accomplish desegregation as it has to

transport the student who voluntarily seeks such assignment

to avoid being in a racial majority.

After showing the peculiar appropriateness of the use of

transportation in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg (North Caro

lina) system and in the Mobile, Alabama system as well, the

Court in ,Swann, said:

“ Desegregation plans cannot be limited to the walk-in-

school.” (402 U.S. at 30)

Then the Court mentioned one possible valid objection to

transportation of students to accomplish desegregation, i.e.,

“ when the time and distance of travel is so great as to either

risk the health of the children or significantly impinge on

the educational process” {Ibid).

In their considerations of plans for the use of trans

portation to accomplish desegregation, district courts are

charged, by Swann, to consider the discussions under (1)

Racial Balances or Racial Quotas, (2) One-race Schools

and (3) Remedial Altering of Attendance Zones. They are

not enjoined to measure relief by the extent to which the

subject school district may have previously transported stu

dents.

The lower courts are charged, by Swann, to reconcile

competing values, as courts have traditionally done, in fash

6

ioning remedial measures. In so doing they must keep in

mind the goal of equal educations opportunities for all chil

dren; those who live near and those who live far from school

and, also, those whose parents are affluent and those whose

parents are indigent. “ Such an opportunity, where the state

has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be avail

able to all on equal terms.” Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka, 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954). That constitutional im

perative transcends fiscal policies and budgetary preroga

tives. Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 (1964).

Here, the Court of Appeals considered the problem of

expense and concluded that the cost of busing in this case is

not unreasonably burdensome (Slip Op. p. 8, footnote 6).

Quite appropriately, the court, sitting en banc, unanimously

required this school board “ to provide . . . free transporta

tion for all students of the school system assigned to schools

located beyond reasonable walking distance of their homes”

(Judgment filed May 7, 1972).

Unquestionably, desegregation in Norfolk cannot be ac

complished without transportation. It seems to be equally

clear, as a matter of paramount law in Virginia, that “ public

elementary and secondary schools for all children” shall be

free, and shall be compulsory for “ every eligible child of

appropriate age, such eligibility and age to be determined

by law” (Constitution of Virginia (1971), Article VIII,

Education §§ 1, 3). No child, regardless of the affluence or

poverty of his parents (who may or may not be hostile to the

desegregation process), can be crushed between the state

law which says he must attend school and the federal law

which requires his assignment to a school remote beyond his

means of locomotion. The court below was imminently cor

rect in holding that “ the Court cannot compel the student

7

to attend a distant school and then fail to provide him with

the means to reach that school” (Slip Op. p. 9).

As was demonstrated in Swann (402 U.S. at 7), resi

dential patterns in metropolitan areas have resulted from

federal, state and local government action; and school board

action, particularly, with reference to the sites and sizes of

schools, based on these patterns have resulted in segregated

education. Now, in obedience to the constitutional mandate

to desegregate schools, the state assigns children to schools

distant from their homes. Consideration of these facts im

pelled the court below to hold “ that the school district as a

part of its plan of desegregation must provide a practical

method of affording free busing for students assigned to

schools beyond normal walking distance of their homes; the

mechanics of the method to be employed by the school dis

trict in discharge of this duty [being] for the District Court”

(Slip Op. pp. 10-11).

B.

T h e A p p a r e n t C o n f l ic t B e t w e e n C ir c u it s ,

I f R e a l , I s I n s ig n if ic a n t

The school board argues that there is a conflict between

circuits concerning provisions of free transportation and

points to the one short paragraph in Clark v. Board of

Education of Little Rock School District, 449 F.2d 493, 499

(8th Cir., 1971) wherein the Eighth Circuit altered the

district court’s free transportation requirement by excluding

“ students who continue to attend the secondary school closest

to their home” ; it having been the feeling of the Court of

Appeals that the constitutional rights of such students have

not been or will not be affected. It is quite apparent that

the Eighth Circuit overlooked the very likely protest of

some excluded student that he must pay for transportation

8

to and from school while others similarly situated ride

shorter distances at public expense.

The reasoning adopted by the Fourth Circuit in the instant

case finds support in the April 11, 1972 decision of the Fifth

Circuit in United States of America v. Greenwood Munici

pal Separate School District, et a l.,___F .2 d ____ (5th Cir.

No. 71-2773) which reversed the district court’s denial of

free transportation for black students residing in non-con-

tiguous or satellite zones. (The opinion is reproduced in the

appendix hereto.) Rejecting the government’s suggestion of

remand for inquiry by the district court as to the transporta

tion needs of the students and the ability of the school

district to meet those needs, the Court of Appeals said:

“ It is implicit in the decisions of the Supreme Court

and of this court that it is the responsibility of school

officials to take whatever remedial steps are necessary

to disestablish the dual school system, including the

provision of free bus transportation to students required

to attend schools outside their neighborhoods. The black

elementary students who were refused free transporta

tion by the district court’s order are victims of the rem

nants of the dual system of schools which existed for so

long under the requirements of Mississippi constitu

tional and statutory provisions. No legitimate reason is

put forth for forcing them and their parents to shoulder

the burden of eliminating these vestiges of segregated

schools in the circumstances present here.” (Slip Op.

pp. 4, 5)

The only uncertainty, if any, is whether equal protection

is being accorded the student who is denied free transpor

tation because his school, although beyond walking distance,

is the closest school to his home. After considering the cost

involved, the court below forestalled the uncertainty, and

avoided the further equal protection question, by requiring

9

free transportation of all students who live beyond normal

walking distance. In the Greenwood case, the Fifth Circuit

did not have before it the facts respecting the needs of the

individual students and the ability of the school district to

meet those needs. It dealt only with the problem which was

most urgent— the transportation of children whom the court

had required to be assigned to distant schools. In the Clark

case, the Eighth Circuit did not state the facts or articulate

its reasoning which caused it to “ feel that the constitutional

rights of the [excepted] students have not been or will not

be affected.”

The petitioners do not claim that the Fourth Circuit’s

order requires them to transport a significant number of

children from their homes to the closest school. It appears

that the difference in budgetary commitment will be slight.

Moreover, the appropriate case in which to test the equal

protection right of a student to free transportation to a

school which, although beyond normal walking distance, is

closest to him would seem to be a case in which such a

student is a party.

II.

Allowance Of Counsel Fees To Plaintiffs

There is no general rule prohibiting the allowance of

counsel fees in the absence of statute. As was pointed out by

Judge Winter, especially concurring with the court below,

the Fourth Circuit has directed the allowance of counsel fees

to plaintiffs in several school desegregation cases, e.g., Bell v.

School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, 321 F.2d 494

(4th Cir. 1963) ; Brown v. County School Board of Freder

ick County, Virginia, 327 F.2d 655 (4th Cir. 1964) ; Griffin

v. Board of Supervisors of Prince Edward County, 339 F.2d

486 (4th Cir. 1964), reversed on other grounds, 377 U.S.

10

218 (1964); Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education,

418 F.2d 1040 (4th Cir. 1969).

Although it then denied the prayer of plaintiff-appellants

for an award of counsel fees, the Eighth Circuit in Clark v.

Board of Education of Little Rock School District, 369 F.2d

661, 671 (8th Cir. 1966), warned: “ The time is coming to

an end when recalcitrant state officials can force unwilling

victims of illegal discrimination to bear the constant and

crushing expense of enforcing their constitutionally accorded

rights.” In the 1971 appeal of the same case, that court held:

“ The plaintiff should no longer be required to bear the con

tinuing expense of attorneys’ fees to vindicate their constitu

tional rights. They are entitled to attorneys’ fees for services

performed by them in processing this appeal and cross-

appeal” (449 F.2d at 493).

The respondents are in accord with the views expressed

by Judge Winter, concurring specially in the judgment

below:

“ The time is now when those who vindicate these civil

rights should receive fair and equitable compensation

from the sources which have denied them, even in the

absence of any showing of ‘unreasonable, obdurate

obstinacy.’ ” (Slip Op. p. 30)

“ It seems . . . to be appropriate now to hold . . . that

reasonable and adequate counsel fees should be

awarded as of course unless special circumstances would

render an award unjust.” {Id., p. 29)

These views are particularly appropriate in the light of this

school board’s long continued pattern of evasion of its duty

to desegregate and its persistent obstruction of the efforts of

the plaintiffs to realize the promise of the 1954 Brown deci

sion, an outline of which is set forth in the appendix to this

brief as “ The History of This Litigation In The Lower

Courts.”

11

Although the respondents believe that a similar pro

nouncement from this Court would greatly accelerate the

course of school desegregation across the land, they urge

denial of the instant petition for reasons above shown and

for a further reason next stated.

III.

The Pendency O f The Instant Petition, Coupled With The Stay

Granted Pursuant To F.R.A.P. 41(B), Shields The School Board

From Its Responsibility To Order School Buses Now

The petition points out that the Virginia Transit Com

pany has served notice on the City of Norfolk that it will

terminate service for all passengers on August 23, 1972. This

being so, the plan for desegregation of Norfolk’s schools may

fail for the 1972-73 school session unless the school board

will acquire school buses in sufficient number to provide

transportation for the students assigned to schools remote

from their homes.

In another school desegregation case pending in the

Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division, the evi

dence indicated that approximately ninety days are required

between order and delivery of transportation equipment

(.Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 324 F.

Supp. 456, 459 (E.D. Va. 1971)). But for the stay granted

pursuant to Rule 41(b) of the Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure and the timely filing of the instant petition, the

school board might even now be ordering school buses and

seeking appropriation of funds with which to defray the cost

of a school transportation system.

Of course, considering the likelihood that the City of

Norfolk will assume the operation of the transit system,

transportation of school children might be accomplished

through that system. In such event, however, the right of

12

school children to free transportation to distant schools, as

recognized by the court below, should not be impaired. Dur

ing 1971-72, and at the instance of the school board, student

fares were raised from 12j/2 ̂ to 17/2^ (from $45 a year to

$63). If the city-operated transit systems can charge chil

dren any amount to get to and from the schools to which

they have been assigned, it can charge enough to place free

public education beyond the reach of the vast majority of

the plaintiff class.

CONCLUSION

Unless the instant petition will be promptly denied or

unless the stay will be promptly vacated, this school board

may again delay desegregation for yet another year or, even

worse, it may deny public education to a large number of

the children whose predecessors sought relief at the hand of

the federal court in May of 1956.

Respectfully submitted,

Sa m u el W. T ucker

Of Counsel for Carlotta Mozelle

Brewer, et al., Respondents

Sa m u el W. T ucker

H e n ry L. M a r s h , III

Jam es W. Be n t o n , Jr .

H ill , T u ck er & M arsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

V ictor J. A sh e

Suite 704^Plaza One

St. Paul’s Boulevard & Plume Street

Norfolk, Virginia 23510

Jack G reenberg

Jam es M . N abrit, III

N orm an C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Carlotta Mozelle Brewer,

et al., Respondents

A P P E N D I X

The History Of This Litigation In The Lower Courts

In this sixteen-year-old litigation to desegregate the Nor

folk, Virginia public schools, the reported opinions are

numerous. Nearly every conceivable tactic to delay, frus

trate and avoid the mandate of Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) has been raised.

After the complaint was filed in 1956, all action was de

ferred pending the holding of a planned special session of

the Virginia Legislature on the subject of school integration,

and then again pending the effective date of the “ massive

resistance” legislation passed at the special session. On Janu

ary 11, 1957, the district court denied the school board’s

motion to dismiss, and on February 12, 1957, the district

court entered an injunction against the school authorities

restraining them from :

refusing, solely on account of race or color, to admit to,

or enroll or educate in, any school under their oper

ation, control, direction or supervision, directly or in

directly, any child otherwise qualified for admission to,

and enrollment and education in such school.

Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 148 F. Supp. 430,

2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 337 (E.D. V a.), both aff’d sub nom.

School Bd. of City of Newport News v. Adkins, 246 F.2d 325

(4th Cir.), cert, denied, 355 U.S. 855 (1957). However, all

proceedings were again stayed pending disposition of ap

peals and petitions for certiorari. It was not until July, 1958

that the school board adopted pupil placement criteria and

procedures. The board thereupon denied all 151 applica

tions filed by black students to attend previously all-white

facilities during the 1958-59 school year. 3 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 945 (1958). The district court ordered the board to

APPENDIX I

App. 2

reconsider and on August 29, 1958, the board announced

that seventeen of the transfer requests would be granted. 3

Race Rel. L. Rep. 955 (1958). The board sought an addi

tional delay in admitting the seventeen black students, but

the district court denied it and the court of appeals affirmed.

Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 3 Race Rel. L. Rep.

1155 (E.D. V a .), aff’ d 260 F.2d 18 (4th Cir. 1958). On

plaintiff’s cross-appeal from the district court’s refusal to

order the admission of the remaining 134 students, the

matter was remanded since the district court had indicated

he would consider separately the validity and application

of the criteria under which the applications were denied.

The schools to which the seventeen Negro students were

assigned, however, were closed, pursuant to Virginia’s

“ school closing” laws, from the fall of 1958 until February,

1959, when the laws and similar Norfolk City ordinances

were declared unconstitutional in James v. Almond, 170

F. Supp. 331 (E.D. Va. 1959; 3-judge court) ; Harrison v.

Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S.E. 2d 636 (1959); James v. Duck

worth, 170 F. Supp. 342 (E.D. Va.) , aff’d 267 F.2d 224 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 361 U.S. 835 (1959). At that time plain

tiffs’ supplemental 3-judge court complaint was dismissed as

moot, and late in the 1958-59 school year, the district court

refused to overturn the board’s denial of the 134 transfer

applications, holding its placement principles facially con

stitutional. Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 181 F.

Supp. 870, 870-81 (E.D. Va. 1959), aff’d sub nom. Hill v.

School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 282 F.2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960).

The district court subsequently permitted the board to as

sign pupils by these principles, although holding that the

board need not utilize the procedures of the Virginia Pupil

Placement Board in view of that agency’s policy of not

granting any transfer requests. Beckett v. School Bd. of City

App. 3

of Norfolk, 185 F. Supp. 459 (E.D. Va. 1959), aff’d 181

F.2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960). During 1961 and 1962, the dis

trict court had occasion to review and overturn school board

denials of black students’ transfer requests (unreported

opinions) although there was no across-the-board attack on

assignment procedures. However, when in 1963 the plaintiffs

filed a motion for further relief, the board discarded pupil

placement and proposed what has come to be known as the

“ Norfolk choice” plan— transfer between black and white

schools located within the same attendance area. This plan

was approved by the district court and on plaintiffs’ appeal

the court of appeals reversed and remanded for reconsider

ation in light of its then recent decisions in this field. The

district court was specifically instructed to consider the

legality or propriety of superimposing a city-wide zone for

all-black Booker T. Washington High School on all other

city high school zones. Beckett v. School Bd. of City of

Norfolk, 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1315 (E.D. Va. 1964), vacated

and remanded sub nom. Brewer v. School Bd. of City of

Norfolk, 349 F.2d 414 (4th Cir. 1965). Proceedings subse

quent to that remand and negotiations between the parties

resulted in the entry of a consent order on March 17, 1966,

approving a new desegregation plan. Beckett v. School Bd.

of City of Norfolk, 11 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1278 (E.D. Va.

1966). Under that plan, reluctantly approved by the dis

trict court, there were multiple-school zones but at the high

school level, transfers between the three white high schools

and Booker T. Washington High were permitted only to fa

cilitate integration. The following year, completion of Lake

Taylor High School necessitated the filing of an amended

plan by the school board, proposing five high school zones,

and allowing only Booker T. Washington students to trans

fer to schools outside their zone of residence. The district

App. 4

court required that transfer privileges be extended to all

high school students but rejected plaintiffs’ attacks upon the

zone lines and upon the proposed replacement of Booker T.

Washington High School on the same site. The court of

appeals reversed and remanded, directing the district court

to consider, with respect to both issues, whether segregated

neighborhood patterns in Norfolk resulted from racial dis

crimination, of which the board was seeking advantage in

its zone lines. Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 269

F. Supp. 118 (E.D. Va. 1967), rev’d sub nom. Brewer v.

School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968).

The district court found the appellate court’s decision “ vague

and confusing.” 302 F. Supp. at 20. Negotiations between

the parties following the remand failed to produce agree

ment. As an interim plan for 1969-70 the school board pro

posed zone line changes between Lake Taylor and Booker T.

Washington to increase integration, and similar changes be

tween Maury and Granby. After hearings in the Spring of

1969, the district court approved the interim plan for 1969-

70. Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 302 F. Supp. 18

(E.D. Va. 1969). After extensive hearings in the Fall of

1969 on the long-range plan of desegregation for 1970-71

and thereafter, the district court approved the school board’s

submission. Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 308

F. Supp. 1274 (E.D. Va. 1969). The court of appeals re

versed and remanded stating that the plan, whereby 76%

of the black elementary pupils would be assigned to 19

all-black schools, 40% of the white elementary pupils would

be assigned to 11 white schools, 57% of the black junior

high pupils would be assigned to 3 black schools, one all-

white junior high school would remain, and segregated high

schools would remain, was constitutionally impermissible.

Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 434 F.2d 408 (4th

App. 5

Cir. 1970). On remand the school board submitted a plan

with results similar to those rejected by the court of appeals.

The district court accepted the plan with certain modifica

tions. Beckett v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, Civ. Action

No. 2214 (E.D. Va. August 14, 1970). All parties except the

United States appealed from the district court’s decision.

The court of appeals delayed its consideration of the case

pending this Court’s decision in Swann v. Charlotte-M eck-

lenburg Board of Education, 401 U.S. 1 (1971) and com

panion cases.

On June 10, 1971, sub nom. Adams v. School District No.

5, 444 F.2d 99 (4th Cir. 1971), the court of appeals re

manded to the district court with instructions to receive from

the school board a new plan which would give effect to this

Court’s decisions in Swann, supra, and Davis v. Board of

School Commissioners of Mobile County, 401 U.S. 333

(1971).

On remand the school board’s proposed new plan was

approved, as modified, by order of July 28, 1971. On Au

gust 25, 1971, in an order indefinitely staying its order of

July 28, 1971, the district court allowed the school system

to commence the 1971-72 school year under the 1970-71

plan on the ground that Executive Order No. 11615 (the

‘“ price freeze” order) “ impeded” the undertaking of the

Virginia Transit Company to transport children to school.

On September 2, 1971, the court of appeals vacated the

stay on the ground that “ the School Board cannot avoid

its constitutional duty to desegregate the schools by plead

ing that the bus company might lose money because of the

price freeze.”

On March 7, 1972 the Court of Appeals decided the

appeals of the black plaintiffs and the white intervenors

and held that the district court had properly approved the

App. 6

plan. The Court also held that the Board was required to

provide free transportation to pupils who live beyond normal

walking distance of their assigned schools and that the board

must pay fees to the plaintiffs’ attorneys for their service in

securing free transportation for the students. Brewer v. The

School Board of the City of N orfolk,___F .2d ....... (4th Cir.

No. 71-1900, March 7, 1972).

App-7

APPENDIX II

In The

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

No. 71-2773

United States of America,

Plaintiff,

versus

Greenwood Municipal Separate School District, et al.,

Defendants,

Lilly Russell, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

versus

Greenwood Municipal Separate School District, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Mississippi

(April 11, 1972)

Before Wisdom, Coleman and Simpson, Circuit Judges.

Per Curiam: Once more we are called upon to deal with

the desegregation problems of the Greenwood Municipal

Separate School District.1 Pursuant to our remand of June

29, 1971, 445 F.2d 388, 389, for the entry of an order re

quiring the implementation of a plan complying with former

decisions of this Court and with the principles established in

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 1971,

402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554, the district court

ordered the school district to provide free bus transportation

to students who elect, on an individual basis, to change

schools under the majority-to-minority transfer provision2

of the District’s court ordered desegregation plan. With re

spect to elementary students who, in accordance with the

desegregation plan, were placed in noncontiguous school

zones and required to attend school outside their neighbor

hoods, the lower court declined to require the school district

to provide free transportation. The plaintiffs have appealed

from the district court’s refusal to order free bus transporta

tion for the latter class of students.3

App. 8

1 In chronological order we have dealt with this District’s problems

in the following cases: United States v. Greenwood Municipal Sepa

rate School District, 5 Cir. 1969, 406 F.2d 1086, cert, denied 1969,

395 U.S. 907, 89 S.Ct. 1749, 23 L.Ed.2d 220; United States v.

Greenwood Municipal Separate School District, 5 Cir. 1970, 422 F.2d

1250; Russell v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School District, 5 Cir.,

June 29, 1971, 445 F.2d 388; United States v. Greenwood Municipal

Separate School District, 5 Cir., July 2, 1971, 444 F.2d 544, vacated

as moot by en banc Court, .... . F.2d ---- (January 12, 1972). The

desegregation suit was originally instituted by the United States in July,

1966.

2 This provision entitles a student to transfer from a school in which

his or her race is in the majority to a facility in which his or her race

is in the minority.

3 The United States as a party to this case did not initiate the motion

involved in this appeal, but did participate in the lower court’s pro

ceedings and has failed an amicus curiae brief with this Court.

App. 9

On this appeal, the Negro plaintiffs contend that the fail

ure of the district court to order free transportation for those

elementary students placed in noncontiguous zones will re

quire black students transferred to the previously all-white

Bankston School to walk two miles each way, across the

main lines of the Illinois Central Railroad, through the cen

tral business district, across the Yazoo River, and along a

main thoroughfare for one-half mile. The school district re

sponds by arguing that the provision of free transportation

is merely a matter of convenience for the black elementary

students involved, that these black students have no con

stitutional claim to free transportation, that the school dis

trict has never furnished transportation to students who re

side within the corporate limits of Greenwood, and that the

school district is without funds to provide the requested

transportation. The lower court, in addition to giving rea

sons for its decision essentially similar to those advanced by

the school district on this appeal, observed that this court

has previously required the provision of free transportation

to students who elected to change schools under a majority-

to-minority transfer plan but that we have never heretofore

directed a school district to provide free transportation for

children placed in noncontiguous zones who go to schools

outside their neighborhoods.

In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

supra, the Supreme Court explicitly held that a school dis

trict which elects to utilize a majority-to-minority transfer

plan as a desegregation tool must provide free transportation

to each student making a transfer under the plan. 402 U.S.

at 26, 27, 91 S.Ct. at 1281, 28 L.Ed.2d at 572, 573. In dis

cussing the pairing and noncontiguous zoning techniques

ordered by the trial court in Swann, the Supreme Court ap

proved the trial court’s direction to the educational authori

App. 10

ties that bus transportation be used to implement these

techniques:

“ In these circumstances, we find no basis for holding

that the local school authorities may not be required to

employ bus transportation as one tool of school desegre

gation. Desegregation plans cannot be limited to the

walk-in school.” 402 U.S. at 30, 91 S.Ct. at 1283, 28

L.Ed.2d at 575.

The plaintiffs and the United States are not in agreement

as to the appropriate disposition of this case. The plaintiffs

urge us to direct the district court to order the school district

to provide free bus transportation to the elementary students

placed in noncontiguous attendance zones. The United

States asks us to remand the cause to the district court with

instructions “ to permit the parties to present evidence as to

the transportation needs of students and the ability of the

school district to meet those needs, and to make full findings

of fact or opinion and findings.”

We have again reviewed the extensive record in this pro

ceeding and conclude that it is unnecessary to remand the

cause to the district court for the hearing and findings sug

gested by the United States. It is implicit in the decisions of

the Supreme Court and of this court that it is the responsi

bility of school officials to take whatever remedial steps are

necessary to disestablish the dual school system, including

the provision of free bus transportation to students required

to attend schools outside their neighborhoods. The black ele

mentary students who were refused free transportation by

the district court’s order are victims of the remnants of the

dual system of schools which existed for so long under the

requirements of Mississippi constitutional and statutory pro

visions. No legitimate reason is put forth for forcing them

App. 11

and their parents to shoulder the burden of eliminating

these vestiges of segregated schools in the circumstances

present here.

The judgment of the district court, insofar as it refused

free transportation to elementary students zoned noncon-

tiguously to attend school outside their neighborhoods, is

reversed and the cause is remanded with directions that the

district court without delay require the school district to

provide such transportation to the affected elementary

students.

Let our mandate issue at once.

Reversed and Remanded with directions.

Coleman, Circuit Judge, dissents.