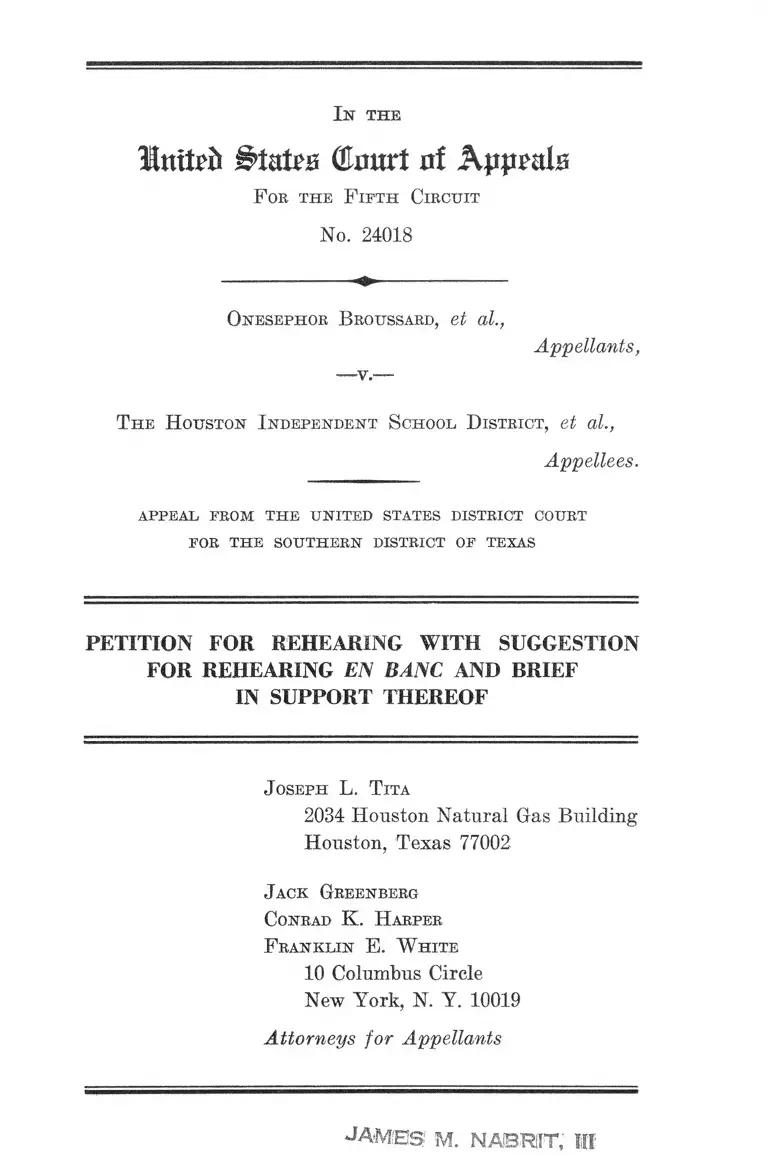

Broussard v. Houston Independent School District Petition for Rehearing with Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc and Brief in Support Thereof

Public Court Documents

July 3, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Broussard v. Houston Independent School District Petition for Rehearing with Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc and Brief in Support Thereof, 1968. b2d06d9f-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d763f807-13c3-4fec-b5e4-daff9eb114a8/broussard-v-houston-independent-school-district-petition-for-rehearing-with-suggestion-for-rehearing-en-banc-and-brief-in-support-thereof. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Imtrfc Court of Appeals

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 24018

Onesephop Broussard, el al.,

Appellants,

T he H ouston Independent School District, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

PETITION FOR REHEARING WITH SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING EN BANC AND BRIEF

IN SUPPORT THEREOF

Joseph L. Tita

2034 Houston Natural Gas Building

Houston, Texas 77002

Jack Greenberg

Conrad K. H arper

F ranklin E. W hite

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

JAMBS' M. NABRIIT, Ilf

I N D E X

Petition for Rehearing ....................................................... 1

Brief in Support of Petition ..................... .......................... 5

Statement of the Case ................... ............................... 5

Reasons for Granting Rehearing en Banc ............... 10

A rgument

I. The Majority Opinions Are in Direct Con

flict With the Law of This and Other Circuits

and of the Supreme Court of the United

States ...................... 11

A. The Prevailing Law ..... ................ ...... ....... 11

B. The Reasons Advanced by the Majority to

Uphold the District Court’s Decision Are

Legally Insufficient ______ 16

1. Retroactivity ............................. 16

2. The other reasons .................................. 19

II. The Majority Erred in Failing to Grant Ap

pellants Any Relief After Conceding That

Appellees Had Violated Appellants’ Constitu

tional Rights in the Selection of School Sites 22

Conclusion ...................... 26

Certificate .............................................................................. 29

PAGE

Certificate of Service 30

ii

A ppendix

Initial Majority Opinion .................. ..... .................. la

Judge Wisdom’s Dissent ............................................. 12a

Majority Supplemental Opinion .............................. 27a

PAGE

Table of A uthorities

Cases:

Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage

for Bibb County, et al., C. A. No. 1296 (M. D. Ga.

1967) .................................................................................. 15

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools

v. Dowell, 375 F. 2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967) ................... 12

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Florida

v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964) ................. 17

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, Vir

ginia, No. 11782 (4th Cir., May 31, 1968) ............ ...12,15

Briggs v. Elliot, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955) ....8,17,

18, 22, 27

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ...............12, 26

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294...........12, 22, 23

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

Virginia, 36 U. S. L. W. 4476 (U. S. May 27,

1968) ..........................................................................12,13,20

Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District,

No. 22, 378 F. 2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967) ........................... 12

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) .......... . 12

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F. Supp.

468 (M. D. Ala. 1967) .................................................. 14

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U. S. 145....................... 23

I l l

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 IT. S. 395 ....... . 23

Raney v. Board of Education of the Gould School Dis

trict, 381 F. 2d 252 (8th Cir. 1967), rev’d and rem.

on oth. gds., 36 U. S. L. W. 4483 (U. S., May 27,

1968) ............................................................................ ....24,25

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F. 2d 191 (5th Cir. 1962) ............. ..... 18

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 347 F. 2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) ........................... 17

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F. 2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ...........................17,18

United States v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk

County, Florida, No. 25768 (5th Cir., April 18,

1968) .......................................................................... 12,14,15

United States v. Concordia Parish School Board, No.

26071 (5th Cir. May 21, 1968) ..................................... 24

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F. 2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff’d with mod. on reh.

en banc, 380 F. 2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert. den. sub

nom. Caddo Parish School Board v. United States,

389 U. S. 840 (1967) ____ ....9,12,13,14,16,

19, 20, 21, 22, 24

Wheeler v. Durham Board of Education, 346 F. 2d 768

(4th Cir. 1965) .................................................................. 12

Miscellaneous:

Southern School Desegregation, 1966-1967, A Report

of the United States Commission on Civil Rights .... 19

PAGE

In the

Imtpfc States Court of

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 24018

Onesephor Broussard, et al.,

■v.-

Appellants,

The H ouston Independent School D istrict, et al.,

Appellees.

A PPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E SO U TH E R N DISTRICT OF TEXAS

PETITION FOR REHEARING WITH SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING EN BANC

Onesephor Broussard and his wife, Yvonne, and Queen

Ethel Young respectfully request rehearing, and suggest

the appropriateness of an en banc rehearing of the de

cision of this Court rendered on May 30, 1968 in an opinion

by District Judge Ben C. Connallv, joined by Circuit Judge

Rives with a dissent by Circuit Judge Wisdom.1 This, 2-1

decision, affirmed an order of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Texas entered on July

13, 1966 per The Honorable Allen B. Hanney, District 1

1 The original and supplemental opinions of the majority and

that of Judge Wisdom, dissenting, are included in an appendix.

Pages in the appendix are denoted by the prefix “A ” .

2

Judge. That decision is reported at 262 F. Supp. 266

(1966).

This case concerns the propriety of certain features of a

$59 million dollar building program embarked upon by the

sixth largest school district in the country—a district

segregated by law in 1954, and which as late as 1966, had

95% of its Negro students in all Negro schools.

The school district admitted that several of its proposed

sites were in dense Negro areas and that the schools to be

built on those sites would open as all-Negro schools; that

although the district was aware of the distribution of the

Negro population in the area, it had no obligation to con

sider race in selecting sites and that sites were not as

sessed in terms of their potential to achieve desegregation.

Appellants moved to enjoin construction at these sites until

the district had conducted a survey with a view to select

ing sites which would assist in eradicating the dual system.

Neither the district court nor the majority in this court

afforded relief.

Judge Wisdom’s dissent said of the majority opinion—

most aptly: “ there is no ameliorating reason for the

majority’s decision. It offends the law as it existed in this

Circuit at the time the case was argued on appeal. It

offends the law more egregiously now” (A. 14).

This petition for rehearing asks this Court, for the fol

lowing reasons, to reconsider, en banc, the decision of May

30, 1968:

1. The majority opinions, in agreeing with the reasons

underlying, and in affirming, the district court’s opinion

and decree, directly conflict with the action of the other

3

panels of this Circuit, the law of other circuits and of the

Supreme Court of the United States.

2. The consequences of a building program of this

magnitude are far-reaching and severe. Left uncorrected,

it will impose continuing and irreparable deprivation on

not only this, but on future generations of Negroes in

Houston. Although some relief was still possible, the panel

majority erred in failing to grant any relief after conced

ing that the Houston Independent School District had vio

lated appellants’ constitutional rights in the selection of

school sites.

Attached is a Memorandum Brief in support of this

petition.

Respectfully submitted,

Joseph L. T ita

2034 Houston Natural Gas Building

Houston, Texas 77002

Jack Greenberg

Conrad K. H arper

F ranklin E. W hite

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N, Y. 10019

I n th e

Ittiteii Butnt (£mvt rtf Appmhs

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 24018

Onesephor Broussard, et al.,

Appellants,

The H ouston Independent School D istrict, et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION

FOR REHEARING EN BANC

Statement of the Case

In March of 1966, the school administration of the Hous

ton Independent School District announced, for the first

time, the precise location of most of the sites selected for

a $59,000,000 building program (voter approval was ob

tained in March of 1965 without announcement of the

specific sites). Immediately opposition was voiced by many

in the community. Experts in the field of sociology, psy

chology and demography including seven Ph.D.’s (three

Department Heads of leading local universities) came to

a common conclusion: the proposed building program, in

placing many of the schools in the heart of areas of high

Negro population was clearly an exercise in the perpetua

tion of segregation, which would summarily cripple future

6

attempts at integration. They added that the consequences

were long range and major since the patterns of residential

segregation in the community were not likely to change for

several generations. The contemplated program would

adversely affect all aspects of community life, and increase

the possibility of racial violence. They offered their ser

vices without cost to assist the district in a study to select

sites which would seek to overcome the effects of segrega

tion and the dual system.

These warnings were not heeded, the offer was rejected,

and the school district plunged forward with the proposed

building program, unchanged.

As a consequence, in May, 1966, suit was filed by Negro

parents in the district seeking to enjoin the building of

those projects which would perpetuate segregation in

Houston and make difficult the establishment of an in

tegrated, unitary school system. (During the trial, appel

lants voluntarily removed from the Court’s consideration

those projects whose impact on segregation was remote.)

At the hearing, in June of 1966, the school superintendent,

who was the primary architect of the building program,

testified readily arid unequivocally, that certain named

schools to be built under the proposed building program

would be “ all-Negro.” These schools would be segregated

for five and probably ten years, and perhaps longer. He

further admitted that the fate of other schools built in areas

of dense Negro population would be the same, and stated

that although the school authorities were very well aware

of Negro population distribution in the community, the

factor of race was never considered in the selection of

school sites, nor were experts ever consulted to evaluate

the consequences of site selection and the resulting segre

gation. Testimony at the hearing also revealed:

7

(A ) That the district’s “Freedom of Choice Plan” did

not, in most particulars, comply with then-existing stand

ards of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare.2

(B) That bus transportation was used in large measure

to discourage integration, i.e., many bus routes carried

Negro students out of their neighborhoods past white

schools to totally segregated Negro schools. (Some routes

had distances of up to 24 miles one way.)

(C) That the district’s feeder system and method of

initial assignment of new pupils utilized dual boundary

lines which existed at a time when segregation was man

dated by state law.

(D) That the ninth grade, faculty, and athletics were

segregated.

(E) That in June of 1966 (twelve years after the Brown

decision), less than five per cent of the Negro students in

Houston attended integrated schools.

The defenses which the school District offered to the

charge that the building program would promote segrega

tion and make integration more difficult, were that:

(1) it had no affirmative duty to consider race in the

selection of school sites (and that they deliberately re

frained from such consideration);

(2) that the district’s “ Freedom of Choice Plan” justi

fies the building of schools in ghettos or areas of dense

Negro population;

2 Assignments were made initially on the basis of race. There

was no requirement of an annual choice nor that letters be directed

to children and their parents informing them of their right to

choose. The transportation system was still segregated (A. 23, n.

8

(3) the policy referred to as the Board’s neighborhood

school program is educationally sound and unrelated to

segregation.

Belying, as did appellee-school board, on Briggs v. El

liot, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955) and its progeny—

that “ The constitution . . . does not compel racial inter

mingling . . . but simply forbids enforced segregation”—

the district court denied all relief. 262 F. Supp. 266,

270-271.

At the time of trial (June, 1966), and at the time the

district court issued its opinion, contracts had not been

signed for any of the so called “ all-Negro” projects. Ap

pellants promptly filed in the district court a Motion for

Injunction Pending Appeal to preserve the status quo until

this Court could rule on the matter. The motion was de

nied.

As late as October of 1966, after appellants had per

fected their appeal, construction on only one “ all-Negro

school” had been commenced; contracts for all the remain

ing Negro schools had not yet been executed. Appellants

filed another Motion for Injunction Pending Appeal. It

was denied but this court granted an accelerated hearing

for January 25, 1967. There followed, however, considera

ble contractual and construction activity, particularly in

the “ all-Negro” schools.

The new schools for which contracts were signed in No

vember, 1966 (some eight in number) were precisely those

which appellants’ petition alleged would perpetuate segre

gation, a fact unchallenged by the district’s Superinten

dent of Schools. Located deep in large, populous Negro

ghettos, bounded by natural and man-made barriers, the

9

prospect of their future integration under existing adminis

trative and transportation procedures was remote.

On January 9, 1967, less than six months after the Dis

trict Court’s opinion (and barely a month after the signing

of the contracts for the several ‘'all Negro” schools cited

above), the School Board, at a regular meeting had an

opportunity carefully to consider the “Jefferson” opinion,3

and specifically the language referring to new construc

tion. The Board majority summarily refused even to re

consider the building program, its effect on integration,

or any modification to conform to Jefferson. They simi

larly refused reconsideration in March, 1967, when that

decision was affirmed en banc.

In January 1967, appellants filed a third motion (the

second in this Court) for injunction pending appeal. It

was argued January 25th, when the ease was also argued

on merits. The third motion was denied February 10, 1967

by the same 2-1 majority for whose opinion rehearing is

now sought. Two months after oral argument of the ap

peal, appellants filed a fourth motion (the third in this

Court) to delay construction pending decision. It has never

been acted upon.

On May 30, 1968, a full sixteen months after oral argu

ment, District Judge Ben C. Connally affirmed Judge Han-

ney’s order denying the injunction. In so doing, he stated,

in reference to integration, “ admittedly, the Houston au

thorities did not affirmatively consider this factor” (A. 29).

3 United, States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372

F. 2d 836, affirmed with modifications on rehearing en banc, 380

F. 2d 385, cert. den. sub nom. Caddo Parish School Board v. United

States, 389 U. S. 840.

10

Nevertheless, he “ agreed” with the District Court opinion,

affirmed it, and did not order relief.

At the present time, many of the schools are nearing

completion; as predicted, they will open as all-Negro

schools unless some judicial relief is afforded.

Reasons for Granting Rehearing en Banc

1. The majority opinions, in agreeing with the reasons

underlying, and in affirming, the district court’s decree are

contrary to and in direct conflict with the law of this Cir

cuit, other circuits and the Supreme Court of the United

States.

2. The majority erred in failing to grant any relief, after

conceding that the Houston Independent School District

had violated appellants’ rights in the selection of school

sites.

11

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Majority Opinions Are in Direct Conflict With

the Law of This and Other Circuits and of the Supreme

Court of the United States.

A. The Prevailing Law

One reading the initial majority opinion must repeatedly

turn to the first page to verify the caption and date to

reassure oneself that one is indeed reading an opinion by

the Fifth Circuit entered in rnid-1968. That suggests how

much the majority opinions are out of touch with the de

cisional law of this Circuit.

The broad underlying issue before the panel was whether

a school district formerly segregated by law is under a

duty to take affirmative action to disestablish the dual sys

tem. More narrowly, there were two issues: (1) whether

the Houston School Board acted improperly in consciously

rejecting considerations of race as a factor in site selec

tion while implementing a $59 million dollar school con

struction program and (2) whether there was any relief

possible where at the time of decision, the construction

program had been completed or was near completion.

The majority’s initial opinion concedes neither that the

Board had an affirmative duty to desegregate the system

nor that it acted wrongfully in failing to consider whether

that duty was performed or shirked in choosing between

alternative school sites. Indeed it appears to adopt the

position of the appellees who not only admitted, but in

sisted that:

12

“ No matter how you interpret the propositions or argu

ments of plaintiffs or the plaintiffs’ law suit, there is

only one issue and that issue is whether or not the

school district has the affirmative duty to integrate the

races. We submit that all cases, including Brown,

clearly hold that the school district does not have the

affirmative duty to integrate the races” (Brief for

Appellees, pp. 21-22).

But the law of this and other circuits and of the United

States Supreme Court is entirely to the contrary. Cf.

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, Vir

ginia, 36 U. S. L. W. 4476 (U. S. May 27, 1968) interpret

ing Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (Brown

I), 349 U. S. 294 (Brown I I ) ; United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, 372 F. 2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966),

affirmed with modifications on rehearing en lane, 380 F. 2d

385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert. den. sub nom. Caddo Parish

School Board v. United States, 389 U. S. 840 (1967); United

States v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk County,

Florida, No. 25768 (5th Cir., April 18, 1968); Brewer v.

School Board of the City of Norfolk, Virginia, No. 11782

(4th Cir., May 31, 1968); Wheeler v. Durham Board of

Education, 346 F. 2d 768 (4th Cir. 1965); Kemp v. Beasley,

352 F. 2d 14, 21 (8th Cir. 1965); Kelley v. Altheimer,

Arkansas Public School District, No. 22, 378 F. 2d 483

(8th Cir. 1967); Board of Education of Oklahoma City

Public Schools v. Dowell, 375 F. 2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967).

Upon rehearing of the Jefferson County case this Court

said (380 F. 2d at 389):

“ The Court holds that Boards and officials administer

ing public schools in this circuit have an affirmative

13

duty under the Fourteenth Amendment to bring about

an integrated, unitary school system in which there are

no Negro schools and no white schools—just schools.

Expressions in our earlier opinions distinguishing be

tween integration and desegregation must yield to this

affirmative duty we now recognize. In fulfilling this

duty it is not enough for school authorities to offer

Negro children the opportunity to attend formerly all

white schools. The necessity of overcoming the effects

of dual school systems in this circuit requires integra

tion of faculties, facilities, and activities as well as

students” (emphasis in original).

The Supreme Court, Green, supra 36 U. S. L. W. at

4479-80, has similarly held that school boards must take

steps “which promise realistically to convert promptly to

a system without a ‘white’ school and a ‘Negro’ school, but

just schools.”

With respect to the selection of sites for schools, the

initial opinion of the majority in this case, is flatly con

trary to Jefferson. Section VII of the Jefferson en banc

decree provides:

“New Construction

“ The defendants, to the extent consistent with the

proper operation of the school system as a whole shall

locate any new school and substantially expand any

existing schools with the objective of eradicating the

vestiges of the dual system” (emphasis added).

As explained in the Jefferson panel opinion, this pro

vision means:

u

“ that . . . race is relevant, because the Governmental

purpose is to offer Negroes equal educational oppor

tunities. The means to that end, such as disestablish

ing segregation among students, distributing better

teachers, equitably equalizing facilities, selecting ap

propriate locations for schools, and avoiding resegre

gation must necessarily be based on race. School

officials have to know the racial composition of their

school population and the racial distribution within

the school district. The Courts and HEW cannot

measure good faith or progress without taking race

into account.” 372 F. 2d at 877 (emphasis added).

Similarly, in Lee v. Macon County Board of Education,

267 F. Supp. 468 (M. D. Ala. 1967) (three judge-court), a

unanimous Court ordered State officials to withhold ap

proval of sites for the construction or expansion of schools:

“ if judged in the light of the capacity of existing facil

ities, the residence of students and the alternative sites

available, the construction will not to the extent con

sistent with proper operation of the school system as

a whole, further the disestablishment of state enforced

or encouraged public school segregation and eliminate

the effects of past state enforced or encouraged racial

discrimination in the state school system.”

The Court also enjoined further reliance upon surveys

not conducted in accordance with the standards of the

Court in approval of school sites.

More recently, this Court has said in the United States

v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk County, Florida,

supra, in language which might well be directed specifically

15

to the Houston Independent School District and in refuta

tion of the majority opinion in the instant case:

“ the appellee contends that inasmuch as the planning

for the school was made without reference to race,

there was no conscious effort on the part of the Board

to perpetuate the dual system. This does not meet

the requirements of the Court order. There is an

affirmative duty overriding all considerations with

respect to the locating of new schools, except where

inconsistent with ‘proper operation of the school sys

tems as a whole’, to seek means to eradicate the ves

tiges of the dual system. It is necessary to give con

sideration to the race of the students. It is clear

from this record that neither the State Board nor

the appellee sought to carry out this affirmative obliga

tion before proceeding with the construction of this

already planned school” (slip op. 6-7, emphasis in

original).

Cf. Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage

for Bibb County, et al., C. A. No. 1296 (M. D. G-a. 1967)

and Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, No.

11782, 4th Cir. decided May 31, 1968, in which proposed

construction was similarly enjoined.

All these holdings, which seem too explicit to be misinter

preted, are ignored in the majority opinion, as are the

decisions of this Circuit and other Circuits, which pre

dated the present action. Nowhere in its initial opinion

does the majority intimate that appellees should have

chosen sites with the objective of eradicating the vestiges

of the dual system.

16

To be sure when confronted by the challenge of Judge

Wisdom’s dissent, the majority adds a supplemental

opinion which attempts to put the matter in focus. But

it is no less shocking that an initial opinion (in a case

regarding the propriety of school construction) could have

been written without reference to the legal standard of

this Circuit embodied in Section Y II of the Jefferson de

cree.

B. The Reasons Advanced by the Majority to Uphold

the District Court’s Decision Are Legally Insufficient

1. Retroactivity

Forced now to grapple with Section VII of the Jefferson

decree, the majority concedes in its supplemental opinion,

that appellees acted erroneously in failing to consider

race but elects rather to condone the admitted unconstitu

tional actions of the Houston Independent School District

“ because the school authorities were not endowed with

sufficient prescience to anticipate Jefferson by some two

years” (A. 29). They state also that: “ it [the Jefferson

opinion] should not be given a retroactive effect unfairly to

penalize this program undertaken in good faith and in full

compliance with the law as it then existed” (A. 30).

But the question of retroactivity is simply not a part of

this case. It is an argument devoid of merit. The Jeffer

son ease’s direction that there was an affirmative duty to

integrate the races and to locate schools with that objec

tive did not rise like Venus from the sea; it reflected the

law of this circuit, at the time this case was filed, when

it was appealed and presently. As early as 1964 this

Court upheld the power of a district court to enjoin:

“ approving budgets, making funds available, approving

employment contracts and construction programs . . .

17

designed to perpetuate, maintain or support a school

system operated on a racially segregated basis” (em

phasis added).

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Florida v.

Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616, 620 (5th Cir. 1964). And in 1965,

almost a year before the Board announced its construc

tion sites, this Court specifically rejected the Briggs case,

upon which the Board and the lower court relied. See Sin

gleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 347

F. 2d 729. There it was said (at 730):

In retrospect, the second Brown opinion clearly im

poses on public school authorities the duty to provide

an integrated school system. Judge Parker’s well

known dictum (“ The Constitution, in other words, does

not require integration, it merely forbids discrimina

tion” ), in Briggs v. Elliot, 132 F. Supp. 776, 777,

should be laid to rest. It is inconsistent with Brown

and the later development of decisional and statutory

law in the area of Civil Rights.

The matter was put even more strongly (in January, 1966,

seven months before the district court’s decision) in a sub

sequent proceeding in Singleton:

The Constitution forbids unconstitutional state action

in the form of segregated facilities, including segre

gated public schools. School authorities, therefore,

are under the constitutional compulsion of furnishing

a single, integrated school system. . . .

This has been the law since Brown v. Board of Educa

tion. . . . Misunderstanding of this principle is per

18

haps due to the popularity of an over-simplified dictum

that the constitution “ does not require integration”

(emphasis added).

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

355 F. 2d 865, 869 (1966).

Thus by mid-1966, when the district court denied all

relief, it was quite clear that school officials had an affirma

tive duty to bring about “ an integrated unitary school sys

tem” . From that it should have followed that school of

ficials would have to be concerned about the placement

of schools in any good faith attempt to eradicate the

dual system. In any event, however, the Houston School

Board knew then, as it knows now, that the location

of schools had much to do with school segregation.

It persisted nonetheless, after ample warning from the

plaintiffs and others, with its program of constructing

schools in the center of high-density Negro areas. It is

not now entitled to consideration because it wrongfully

assumed that Briggs (even then no longer the law) was

justification for reinforcing rather than disestablishing its

dual system.4

4 This marks the fourth appeal to this circuit by Negro plaintiffs

seeking relief against this the sixth largest school district in the

United States. Judge Connally, author of the majority opinion,

said in 1960 when considering the first integration plan submitted

by the Houston School District, the proposed “ plan does not con

stitute compliance wnth the * * # order of this Court, nor does it

constitute a good faith attempt at compliance,” but rather is a

“subterfuge designed only to accomplish further evasion and delay.”

(Emphasis added.) Judge Brown of this Circuit saw fit to quote

this particular language when once again considering the school

district’s efforts toward segregation (Boss v. Dyer, 312 F. 2d 191,

at- 192). Today, regrettably, this language remains the apt descrip

tion of a district bent on discrimination at any cost.

19

2. The other reasons

There are many inferences contained within the ma

jority opinions which suggest that other factors besides

ignorance offer a reasonable basis for excusing the Hous

ton Independent School District from complying with a

clear constitutional mandate. Some deal with integration

and some are quasi-equitable. In concert, they form another

portion of the “ rationale” of the majority opinion. Singly

and collectively they fall far short of the constitutional

mark.

a. The majority opinion contends “ that the constitu

tional rights of the students are otherwise protected by

“ an adequate Freedom of Choice Plan” , apparently on

the assumption that since students may choose any school

in the district the placement of particular schools is not

important (A. 30). But the Court earlier admits that

“ the Board’s experience has shown that . . . students prefer

to attend the school in proximity to their homes” (A. 4).

It is dubious, therefore, that “ free choice” is likely to

overcome any segregative effects resulting from the pur

poseful placement of small schools in ghetto areas.®

Even more important, however, is the Board’s policy of

providing transportation only where the closest school is

more than two miles from the child’s home. (As we have

explained in our original brief before the panel, the district 5

5 Even if freedom of choice might aid in integrating those

schools placed in outlying white areas, it was quite clear that it

would not integrate the schools at issue here—those placed in

Negro areas. White children in Houston like those elsewhere, uni

formly choose only white schools. See Southern School Desegrega

tion, 1966-67, A Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights, at p. 142. “During the past school year, as in previous

years, white students rarely chose to attend Negro schools.” Cf.

United, States v. Jefferson County, supra, 372 F. 2d at 889.

20

deviated from its own policy and provided transportation

to promote segregation. Thus white children were fur

nished transportation past Negro schools and Negro chil

dren past white schools.) Faced with having to provide

his own transportation if he chose to leave his neighbor

hood, most Houston children declined to leave the neigh

borhood. Freedom of choice was stifled by the Board’s

restrictive transportation policy.

Finally while quoting Jefferson (“ that freedom of choice

is not a goal in itself” (A. 11)), the majority appears to

hold squarely to the contrary:

Indeed, under the Houston plan, as described by the

school authorities, it would appear that an “ integrated

unitary school system” is provided where every school

is open to every child (A. 12). (Emphasis added.)

But the Court in Jefferson and the Supreme Court in

Green specifically rejected that view. Said the Court in

Green, 36 U. S. L. W. at 4478:

The School Board contends that it has fully discharged

its obligation by adopting a plan under which every

student, regardless of race, may “ freely choose the

school he will attend.” . . . But that argument ignores

the thrust of Brown II. In the context of the state

imposed segregated pattern of long standing, the fact

that in 1965, the Board opened the doors of the former

“white” school to Negro children and of the “ Negro”

school to white children merely begins, not ends our

inquiry whether the Board has taken steps adequate

to abolish its dual segregated system.

21

The majority plainly erred therefore in assuming that

“ an integrated unitary school system” was achieved be

cause any child could choose any school.

b. The majority also speaks of the problems of the con

tractors and laborers who would be put out of work, had

an injunction been granted. Certainly any third parties

have legal remedies against the Houston Independent

School District. It should be remembered that no con

tractual obligations had been entered into at the time the

injunction was sought. Moreover the ink was hardly dry

on the contracts and construction had not yet commenced,

when the instant case was argued in this Court and when

Jefferson was handed down. The Houston Independent

School District deliberately entered into this unconstitu

tional building program with full knowledge and notice

of the possible consequences.

c. The majority asks “ What is the alternative? The

plaintiffs offer none” (A. 29). The very question im

properly places the burden and reflects a misconception of

the law. Assistance was offered by the plaintiffs and re

jected by the district. Preparation of a building program

takes a considerable length of time. It is not reasonable

to expect the appellants to have evolved a comprehensive

plan in the less than six weeks between the first announce

ment of site selection and the commencement of the hear

ing. All that was ever asked in the injunction was a mini

mum delay to study the effects on segregation of a certain

specified number of projects. The bulk of the program

was left unimpeded.

d. The majority alleges that the school district was

irrevocably committed to certain sites previously pur

22

chased. But testimony at the hearing indicated that no

substantial loss would be incurred by virtue of selling ex

isting sites and acquiring new ones.

II.

The Majority Erred in Failing to Grant Appellants

Any Relief After Conceding That Appellees Had Violated

Appellants’ Constitutional Rights in the Selection of

School Sites.

In denying all relief the majority posed the question this

way: Whether a court of equity should enjoin a program

of this magnitude because the school authorities were not

endowed with sufficient prescience to anticipate Jefferson

by some two years? We have shown elsewhere that no pre

science was necessary; that it was sufficiently clear then

that Briggs was no longer the law and that school officials

were obliged to take race into account in formulating

affirmative action to disestablish the dual system.

The record does not show the extent to which the building

program had been effectuated at the time of the panel

opinion. Apparently, neither the majority nor the dissent

believed it had been completed. This is an important

matter into which the district court should be allowed to

inquire on remand. But even assuming that construction is

under way at all the contemplated sites or, indeed, that the

program was nearing completion or had been completed,

we submit that there were more options than either grant

ing or denying the requested injunction and that the court

erred in failing to consider them.

In the second Brown decision the Supreme Court de

clared that “ in fashioning decrees the Courts will be guided

23

by equitable principles” (349 U. S. at 300). Equity courts

have broad power to mold their remedies and adapt relief

to the circumstances and needs of particular cases. Where,

as here, the public interest is involved “ those equitable

powers assume an even broader and more flexible charac

ter . . . ” Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U. S. 395, 398.

Accordingly, such courts have required wrongdoers to do

more than cease unlawful activities and compelled them to

take affirmative steps to undo effects of their wrongdoing.

In Louisiana v. United States, 380' U. S. 145, 154, it was

put this way:

The Court has not merely the power but the duty to

render a decree which will so far as possible, elimi

nate the discriminatory effect of the past as well as

bar like discrimination in the future.

We believe the panel majority erred in failing to con

sider whether there were any equitable measures available

to the district court on remand which might have tended

to “ eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past” , i.e.

the segregative effects of an admittedly unconstitutional

building program.

Although much harm is done by the erection of schools

without regard to their tendency to reinforce the dual

system, all is not necessarily lost simply because the build

ing has been completed or because it has progressed to

such a point that an injunction against construction would

be unwise. In some situations by reorganizing the grade

structure (having it serve other or fewer grades than

those for which it was intended) or by changing the method

of assigning pupils to that particular school, the harm

caused might, to some extent, be dissipated. Judge Wis

24

dom was, therefore, correct in suggesting that “ It is not

too late, however, for the Board to survey the situation

and to propose expedients to undo the effects of its build

ing policy” (A. 26). Having effectively denied three re

quests for injunction pending appeal, thereby bringing

about this very difficult situation, the very least the Court

should have done was to remand the case with instruc

tions that the district court hold a hearing to ascer

tain whether and to what extent the segregative effects

of the building program might be dissipated by grade re

organization or by alternative methods of assigning pupils.

By way of preparation for that hearing, it would seem

appropriate for the district court to require the board to

make the kind of survey proposed by Judge Wisdom and

to report its findings at the hearing.

That disposition would be entirely consistent with the

law in this and other circuits. Thus, for example, in United

States v. Concordia Parish School Board, No. 26071 (5th

Cir. May 21, 1968), although this Court denied a motion

by the United States to enjoin pending appeal, construc

tion alleged to be in violation of Section VII of the Jef

ferson decree, it nonetheless stated that the denial was:

Without prejudice, however, to the right of the ap

pellants to seek in this court, on appeal, when the

case is heard on the merits, such modification of the

Board’s attendance plans as would lessen the likeli

hood that the new facility would be attended solely by

white pupils.

Cf. Raney v. Board of Education of the Gould School Dis

trict, 381 F. 2d 252 (8th Cir. 1967) reversed and remanded

on other grounds, 36 U. S. L. W. 4483 (U. S., May 27, 1968).

25

In Raney, Negro plaintiffs (in a district having only two

twelve-grade school complexes, one Negro and one white)

sought to enjoin replacement of the Negro high school at

the Negro site on the ground that it would perpetuate

the dual system. The district court denied relief and, be

cause of the illness of the Court reporter, construction was

completed prior to determination on appeal. The Eighth

Circuit recognized that alternative uses of the building

and of assigning students thereto would undo segrega

tion that would otherwise result from its ill-chosen site.

Said the Court:

There is no showing that the Field [Negro] facilities

with the new construction added could not be con

verted at a reasonable cost into a completely inte

grated grade school or into a completely integrated

high school when the appropriate time for such course

arrives (381 F. 2d at 255).

The Supreme Court, in reversing and remanding on other

grounds, specifically pointed out that petitioners might

renew on remand their request that the new construction

be utilized some other way (36 U. S. L. W. at 4483-84).

In sum, we believe the panel majority erred in assum

ing that because construction was well under way or had

been completed no relief was appropriate.

26

CONCLUSION

Appellants, at great expense, have done everything pos

sible to prevent implementation of a massive construc

tion program which all members of a panel of this court

now agree was conducted unconstitutionally, but which

the panel majority claims it is powerless to undo. It is

difficult, even with the benefit of hindsight, to see what

more appellants might have done. Well in advance of the

signing of contracts, we sought by way of injunction a

minimum delay so that the Board could reconsider its

sites in light of its constitutional obligation to disestab

lish the dual system. Our request was refused by a trial

court in an opinion at variance with the law then and now.

The same trial court refused to delay commencement of

construction pending this appeal, even though no harm

would have been caused thereby. Several times, there

after, we moved in this court to preserve the status quo

pending decision. Again, we were rebuffed by the same

majority that now refuses all relief. Added to that, some

sixteen months elapsed between oral argument and deci

sion during which time the Board hurried to complete the

program.

Now the majority concedes, albeit grudgingly, that ap

pellants were correct all along but abstains from entering

any relief because construction is completed (or near com

pletion). We believe the judiciary, and certainly this Court

en banc, is capable of affording Negro minors seeking

the benefits of Brown more than a “ Pyrrhic victory.” .

The notion of awarding a bonus for delay in the area of

integration is as repugnant to the law of this and every

circuit, as is withholding a constitutional right because of

hostility to its enforcement. Constitutional guarantees are

made of sterner stuff, and are. not so readily expendable.

No case has presented to this Court the propriety of a

building program as massive and so dangerous, if wrongly

implemented, to the effectuation of an “ integrated unitary

school system” as that involved here. The consequences of

the Board’s acknowledged unconstitutional conduct are far

reaching and severe. They impose continuing and irrepara

ble deprivation on this and future generations of Negroes

in Houston. Whether the majority properly dealt with the

underlying questions and whether the district court should

investigate possible remedial action merits the attention

of the full court.

The Houston Independent School District is by its own

projections soon to launch on another building program.

They may well elect to follow their past practice, rein

forced by the majority opinion’s affirmation, and again

utilize the delays inherent in judicial procedures. To avert

this very real danger, Judge Wisdom as a dissenting voice

seeks to admonish not only this, but other districts against

such a course (A. 26). It remains however, merely the ad

monition of a dissenting Judge.

We believe the decision of the majority, if left to stand,

not only sets a retrogressive legal precedent, totally in

conflict with the existing law, but will also be an open in

vitation to still another round of subversion and evasion

by districts such as Houston. The resilience of the Briggs

case should be an object lesson, demonstrating that bad

’ l l

law can confound, confuse and substantially impede the

progress of integration in the South despite seemingly

clear language of refutation.

For the foregoing reasons appellants ask that this Court

grant rehearing en banc.

Respectfully submitted,

Joseph L. Tita

2034 Houston Natural Gas Building

Houston, Texas 77002

Jack Greenberg

Conrad K. H arper

F ranklin E. W hite

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

Certificate

I hereby certify that the foregoing Petition for Rehear

ing with Suggestion for Rehearing en banc is presented in

good faith and not for purposes of delay.

Attorney for Appellants

30

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that on the 3rd day of July, 1968, I

served a copy of the foregoing Petition for Rehearing with

Suggestion for Rehearing en banc and Brief in support

thereof upon Joe H. Reynolds, Esq., 1340 Tennessee Bldg.,

Houston, Texas 77002, by mailing a copy thereof to him

at the above address via United States mail, postage pre

paid.

Attorney for Appellants

A P P E N D I X

A P P E N D I X

la

Initial Majority Opinion

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 2 4 0 1 8

ONESEPHOR BROUSSARD, ET AL,

Appellants,

versus

THE HOUSTON INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT,

ET AL,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Texas.

(May 30, 1968.)

Before RIVES and WISDOM, Circuit Judges, and

CONNALLY, District Judge.

CONNALLY, District Judge: This action was filed

in the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Texas as a suit for injunction against the

Houston Independent School District. The plaintiffs

are a number of pupils of that District, of the col

ored race, who have filed the proceeding as a class

action. Its purpose is to restrain the School District

and its officers and employees from acquiring and

2a

condemning land, from soliciting bids, accepting bids

or distributing funds, letting contracts or doing any

other acts in furtherance of an extensive program

for the construction of new schools and the im prove

ment and modernization of other schools within the

District. This relief was sought upon the allegation

that the program of new construction and rehabilita

tion—in particular the location of a number of new

schools—was designed by the Board to prom ote and

to perpetuate de facto segregation in the schools. It

was alleged that such de facto segregation deprived

the minor plaintiffs of their right to attend an inte

grated school, and thus deprived them of due process

and equal protection of the laws. After a full hearing

consisting of seven trial days and including an in

spection by the trial judge1 of some 17 locations, in

cluding the four or five most vigorously attacked by

the plaintiffs, the injunctive relief was denied.1 2 We

affirm.

To bring the issues thus presented into proper fo

cus, som e background is necessary. The Board of Ed

ucation of the Houston Independent School D istrict is

com posed of seven elected m em bers. It is charged by

law with the operation and maintenance of the public

school system within its geographic limits. This is an

area of approxim ately 311 square miles, including

most of the Houston, Texas metropolitan area. In ex

cess of one million persons reside within its geo

1 The Honorable Allen B. Hannay, an able and experienced

trial judge.

2 The District Court opinion is reported 262 F.Supp. 266

(1966).

Initial Majority Opinion

3a

graphic boundaries. Approximately 230,000 scholas

tics attend its schools, with an average increase of ap

proxim ately 10,000 students per year. It is the sixth

largest school district in the nation. At the time of

trial, it operated in excess of 200 schools (elementary,

junior high and high schools), located throughout the

District.

At the time of Brown vs. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954), the Houston schools were com pletely

segregated by state law, with a dual boundary sys

tem. Following Brown, on Decem ber 26, 1956 a suit

was filed in the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Texas (C.A. 10444, Ross vs.

Board of Trustees, Houston, Independent School Dis

trict) to desegregate the Houston schools. Following

a series of hearings the District Court entered an or

der directing that the schools be desegregated on a

one-grade-per-year basis, beginning with the school

year of September 1960, with com plete desegregation

to be effected by 1971. On appeal, this action of the

trial court was affirm ed [Houston, Independent

School District v. Ross, 282 F.2d 95 (I960)]. Since

that time the plan of desegregation has been acceler

ated, in large measure by voluntary action by the

Board,8 so that at the time of trial (June 1966) only

the ninth grade remained segregated, and with that

remaining vestige to be eradicated beginning with the

school year of September 1967.3 4

3 At least such action was “voluntary” in the sense that it was

not court ordered.

4 Additionally, the Board had taken steps to integrate its

school faculties and its athletic program, each of which had until

recently remained largely segregated.

Initial Majority Opinion

4a

The record shows that there is in operation a free

dom of choice plan, pursuant to which a student, re

gardless of his race or place of residence, m ay

register at any school within the District, m erely by

notifying the school authorities of the choice, and by

having the student appear at the school of his choice

on opening day.5

While it would appear at first blush that such a plan

would be calculated to lead to overcrowding of some

of the m ore popular schools, the Board’ s experience

has shown that in large measure the students prefer

to attend the school in proxim ity to their homes, and

in no instance had admission been denied to a school

of one’ s choice by reason of overcrowding.

With some variations due to population densities, it

has been the policy of the Board to space the loca

tion of its elementary schools at intervals of approxi

mately one m ile; junior high schools at intervals of

two m iles; and senior high schools at three m ile in

tervals throughout the District. Thus inevitably many

of the schools are located in predominantly colored

residential sections, others in predominantly white

residential sections, and still others in areas of a

mixed or com m ingled racial pattern.6 Similarly, the

5 This was true at the time of trial for all grades except the

ninth, and, as stated, this exception expires with the 1966-67

school year.

6 Examples of schools within “fringe areas” and having ap

proximately equal numbers of white and negro students are Mc

Gregor Elementary, Kashmere Gardens High, Lockett Junior-

Senior High, Rogers Junior High.

Brock Elementary School furnishes an interesting ex

ample of the effect which a change in residential pattern will have

on a school. Originally attended principally by white children,

Initial Majority Opinion

5a

new construction and renovation is even-handedly ap

plied throughout the District, some in white, som e in

negro and some in commingled areas. As most of the

scholastics, regardless of their race, prefer to attend

the school in their immediate vicinity,7 the racial

com position of the student body of each school re

flects, in general, the racial com position of the

neighborhood wherein such school is located.

The need for the construction program is not de

nied. It is undisputed that many of the existing

school facilities are grossly overtaxed; some areas

of rapidly increasing population are inadequately

served, or served not at all.

Initial Majority Opinion

On M ay 19, 1965, the voters of the Houston Inde

pendent School District by popular election authorized

the issuance of some $59 million in bonds for con

struction purposes. The program contemplated the

construction of a number of new schools, some at

new, others at old sites; the construction of new

classroom s, the addition of cafeterias, the enlarge

ment of campuses, etc.; and the repairing and re

furbishing of existing facilities at still other locations.

Some fifty schools were involved in the project.

While this was the largest single bond issue for this

purpose in the Board’ s history, experience had shown

the number of negro children increased as the complexion of the

neighborhood changed from white to colored. Now it is pre

dominantly negro. Another interesting example of a mixed racial

pattern is that of McReynolds School. It is approximately 49%

Latin-American, 49% Anglo-American, and 2% negro.

7 This is the testimony of plaintiffs’ witnesses, and con

firmed by School Board records.

6a

that substantial new construction was necessary at

intervals of approxim ately four years. Preceding is

sues had been in the amount of $39 million in 1963 and

in the amount of $32 million in 1959.

This was the thrust of plaintiffs’ case. After de

veloping the fact that certain schools in areas of

dense colored population were overcrowded, and that

the construction program contemplated the relief of

this situation by the erection of new schools close by,

or the enlargement of existing facilities, the testi

m ony of several sociologists and psychiatrists was

offered. These witnesses, all eminently qualified in

their fields, testified in substance that a colored child

would not receive as good an education attending a

com pletely, or predominantly, colored school as he

would attending a m ore thoroughly integrated

school.8 Hence the argument was advanced that the

construction of a new school in an area of dense ne

gro population, or making an old school more service

able, m ore efficient, or m ore attractive, would, in ef

fect, constitute a denial to the negro child residing

in such area of the integrated-type education to

which he was entitled.

Despite their pedagogic attainments, none of these

witnesses had any experience as a school adminis

8 These witnesses further testified that the Board should

take as its objective the achievement of the same white to colored

ratio in each school as prevailed in the overall census of the

scholastics within the District (namely, 70% white, 30% negro).

They further testified that this should be achieved by bussing the

students outside of their residential areas, if other expedients

were ineffective.

Initial Majority Opinion

7a

trator. They had little fam iliarity with the overall

building program . No one could or would venture a

suggestion as to where or how any one of the ques

tioned sites should be relocated. They showed little

awareness of any factor to be taken into account in

the location of a school other than the racial com po

sition of the area. The only answer which these wit

nesses could offer to the question as to how they

would solve the problem of locating the new schools

was to say that they should not be located in a pre

dominantly negro area ;9 and to say further that if

given time they (the experts) could no doubt find a

better location.

The defense was that the policy of the School

Board, past and present, was to build the schools

where they were needed, i.e., where they would be

most convenient for the students, particularly those of

tender years. If was shown that in addition to the

need for a school in a given area, many considerations

came into play in the selection of a particular site.

Am ong others were (a) econom ics—in some cases the

Board, with foresight, had previously acquired prop

erty not then needed, but held for future use which

might profitably be availed of at this time, (b) acces

sibility and convenience—including the condition of

the streets, the avoidance of traffic hazards, etc.,

and (c ) coordination with the City Planning

Commission, with realtors and developers plan-

9 These witnesses all seem to have a great affinity for the

word “ghetto” . They repeatedly referred to certain sections of

this city by that term. Judge Hannay found no ghetto-type

conditions in the vicinity of any of the sites which he visited.

Initial Majority Opinion

8a

ning new subdivisions and developments, where

large population increases might be anticipated. On

abundant and convincing evidence, Judge Hannay

found that the Board had been guided only by such

proper considerations as these, and denied relief.

Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Ed., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir.

1966); Clark v. Bd. of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F.2d

661 (8th Cir. 1966); Sealy v. Dept, of Public Instruc

tion of Pa., 252 F.2d 898 (3rd Cir. 1958).

When carefully analyzed, the plaintiffs’ position is

simply this. No new schools should be built, or old

schools im proved, in densely populated colored areas.

The child resident in such area, regardless of his

wishes, of necessity must be required to attend a

school in some other section with a relatively high

ratio of colored-to-white students. Considerations of

convenience, of traffic hazards, or the wishes of the

student and his parents should be disregarded. Such

child simply would have to attend a high ratio col-

ored-to-white school, and would be required to do this

only because he was a negro.

The Constitution does not require such a result,

and we entertain serious doubt that it would permit

it. Racial im balance in a particular school does not,

in itself, evidence a deprivation of constitutional

rights. Zoning plans fairly arrived at have been con

sistently upheld, though racial im balance m ight re

sult. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Bd. of Ed., 369

F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966); Springfield School Commit

tee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d 261 (1st Cir. 1965); Wheel

Initial Majority Opinion

9a

er v. Durham City Board of Education, 346 F.2d 768

(4th Cir. 1965); Gilliam v. City of Hopewell, Vir

ginia, 345 F.2d 325 (4th Cir. 1965); Downs v. Kansas

City, 336 F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964); Bell v. School

of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.2d 209 (7th Cir. 1983).

Houston has not adopted a zoning plan. Rather, un

der the Houston plan, a child m ay attend the school

of his choice. Those negro children who wish to at

tend a school some distance from their homes, with a

high colored-white ratio, m ay do so. But those negro

children who wish to attend a school close to their

hom es have constitutional rights, too; and they well

might assert such rights against a School Board

which refused to construct a needed school in their

area simply because it would he attended largely

by negro students. This would be discrimination with

a vengeance, based solely on account of race.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

And would it not constitute discrimination to hold, as

plaintiffs would have us hold, that every child in

Houston m ay attend the school of his choice— chosen,

perhaps, because it is convenient, because his best

girl attends, because it has a good football team, or

for any other sufficient reason—except those children

living in the Fifth W ard; and to hold that they must

attend the school chosen for them because of what

others have determined to be a favorable colored-

white student ratio?10 In their zeal to press for inte

gration of the races at all levels and in all things—

10 Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir.

1965).

Initial Majority Opinion

10a

scholastic, business, social, m arital—m any persons,

som e of good will, com pletely lose sight of the rights

of those who do not desire to be integrated at the m o

ment. The Constitution protects that right, also. The

recognition given by Court decree and by statute in re

cent years to the negro’ s constitutional freedom from

enforced segregation in the field of public education,

public transportation, voting, jury service and in re

lated areas is to a privilege which he m ay enjoy. But

integration, at these levels, is not a concept to which,

like Procrustes’ bed, every individual must be fitted,

regardless of his desires. If a negro prefers to ride in

the rear of the bus today, he m ay not be com pelled

to take a forw ard seat. If he wishes to vote, he m ay;

but he m ay not be required to cast his ballot by

those who feel it would be to his, or their, benefit that

he do so. Of m ost recent recognition, he m ay inter

m arry with one of another race .11 The Constitution af

fords him these rights, not recognized until recently.

It does not im pose an obligation on him1 to exercise

them. It is for him to decide whether it be to his ad

vantage. The individual is still the m aster of his

fate.11 12

The validity of the defendant B oard ’s freedom

of choice plan is attacked by the plaintiffs. It is ar

gued that when new schools are com pleted in the col

11 Loving v. V irginia,-----U.S........... (June 12, 1967), where the

Court states, “Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or

not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual

and cannot be infringed by the State.” (Emphasis added.)

12 “It is the individual who is entitled to the equal protection

of the laws.” McCabe vs. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe R. Co.,

235 U.S. 151 (1914); Reynolds vs. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964);

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

Initial Majority Opinion

11a

ored sections, they will be too convenient and too at

tractive; and under the freedom of choice will tend

to produce a high incidence of de facto segregation.

Hence we observe that a freedom of choice plan—

fairly and non-discriminatorily administered—has had

the specific approval of this court as recently as the

en banc consideration of United States vs. Jefferson

County Bd. of Ed., . . . . F.2d . . . . (5th Cir. 1967),

where the court said:

“ Freedom of choice is not a goal in itself.

It is a means to an end. A schoolchild has no

inalienable right to choose his school. A free

dom of choice plan is but one of the

tools available to school officials at this stage

of the process of converting the dual system

of separate schools for Negroes and whites

into a unitary system. The governmental

objective of this conversion is—educational

opportunities on equal terms to all. The

criterion for determining the validity of a

provision in a school desegregation plan is

whether the provision is reasonably related to

accomplishing this objective.” 13

While we reiterate that “ a schoolchild has no inalien

able right to choose his school” , we add the corollary

that where the law or rules of the School Board af

13 And see the language of Judge Wisdom, speaking for this

Court in Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

355 F.2d 865 (1966), at p. 871:

“At this stage in the history of desegregation in the

deep South a freedom of choice plan is an acceptable method

Initial Majority Opinion

12a

ford this right to others,14 it m ay not be denied to the

negro child because of his race.

Judge Wisdom’s Dissent

Indeed, under the Houston plan, as described by

the school authorities, it would appear that an “ inte

grated, unitary school system ’ ’ is provided, where ev

ery school is open to every child. It affords “ educa

tional opportunities on equal terms to all.” That is

the obligation of the Board.15

The action of the trial court was right, and is

AFFIRM ED.

Judge W isdom ’s Dissent

WISDOM, dissenting.

I respectfully dissent.

It seems scarcely possible that in the Fifth Circuit

a school board in a great city could look a judge in

the eye and say that in spending sixty million dol

lars for school buildings the board need not consider

residential racial patterns as a relevant factor in the

selection of school sites. The Houston School Board

knows, everyone knows, that the location of schools

is highly relevant to school segregation.

for a school board to use in fulfilling its duty to integrate

the school system.”

and cases there cited.

14 Such is the case here. The plaintiffs do not challenge the

freedom of choice as applied to white students, nor question the

new construction in white or in mixed residential areas.

15 United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Ed., supra, p. 6 slip

opinion, en banc consideration.

13a

I can understand, though I can not accept, the

Board’ s explanation of its decision. The Board relied

on the Briggs dictum: “ The Constitution . . . does

not require integration. It m erely forbids desegrega

tion.” Briggs v. Eliott, E.D.S.C. 1955, 132 F. Supp.

776. Many other school boards throughout the South

have been willing victims of the Briggs word-magic.

They em braced the chains that held them captive.

The glitter of the rhetoric obscured the looseness of

their bonds.

I doubt if many laymen understand the question-

begging distinction between “ desegregation” and

“ integration” . In the vernacular there is no distinc

tion. But here, as in similar situations in other states,

the lay board understood the effect of their law yers’

reading of Briggs. As stated in the Board’s brief:

“ There is no affirm ative duty on the School District

to consider race in the selection of school sites” ;

that would be an affirm ative act leading to integra

tion.1

In the years that first followed the School Desegre

gation cases, Brown v. Board of Education, 1954, 347

U.S. 483, apologists for token desegregation could ra

tionalize the Delphic riddle Briggs found in Brown.* 2

Briggs offered a middle way in a difficult transition-

ary period. And the lack of specific directions in the

Supreme Court’s mandate in Brown along with a

’ The Board’s brief states: “ there is only one legal issue. That

issue is whether or not the school district has this affirmative

duty to integrate the races” .

2 Briggs was one of the original School Desegregation cases.

Judge Wisdom’s Dissent

14a

district court’ s inherent equitable power and prim ary

responsibility for tailoring decrees to individual

cases seem ingly gave inferior courts wide latitude in

their handling of school desegregation plans. Later

and slowly, by the case-by-case development of the

law, the Supreme Court put limits on the scope of an

inferior court’s authority to bless local action to de

segregate schools.®

Judge Wisdom’s Dissent

There is no ameliorating reason for the m ajority ’s

decision. It offends the law as it existed in this circuit

at the time the case was argued on appeal.1 It offends

the law m ore egregiously now.3 4 5

I.

The broad question this case presents is whether

the administrators of a public school system are un

der a duty to take affirm ative action to desegregate

3 See, e.g. Cooper v. Aaron, 1958, 358 U.S. 1, 78 S.Ct. 1399,

3 L.Ed.2d 3; Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

1965, 382 U.S. 103, 86 S.Ct. 224, 15 L.Ed.2d 187; Rogers v. Paul,

1965, 382 U.S. 198, 86 S.Ct. 358, 15 L.Ed.2d 265.

4 United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 5

Cir. 1966, 372 F.2d 847, aff’d en banc, 1967, 380 F.2d 385, cert,

denied sub nom. Caddo Parish School Board v. United States,

1967, U.S. , S.Ct. , 19 L.Ed.2d 103; Lee v.

Macon County Board of Education, M.D.Ala. 1964, 231 F. Supp.

743; 1966, 253 F. Supp. 727; 1967, 267 F. Supp. 458; Braxton

v. Board of Public Education of Duval County, M.D.Fla. 1962, 7

Race Rel. L. Rep. 675, aff’d 5 Cir. 1964, 326 F.2d 616, cert,

denied, 377 U.S. 924, 84 S.Ct. 1223, 12 L.Ed.2d 216.

5 Stell v. Board of Education for the City of Savannah and

the County of Chatham, 5 Cir. 1967, F.2d [No. 23724,

Dec. 4]; Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 5 Cir. 1968, F.2d [No. 25162, March 12];

United States v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk County,

Fla., 5 Cir. 1968, F.2d [No. 25768, April 18],

15a

the school district. The Board faced up to this issue.®

The narrow question before the Court is whether, in

a context necessarily involving a choice of alterna

tives, a school board should select sites tending to

erase the effects of the dual system of legalized seg

regated schools or is free to select sites tending to

maintain segregation (or token desegregation). The

Board recognized the presence of this issue, but re

solved it by determining that consideration of race

would be an affirm ative integrative act that need not

be taken.

M y brothers sweep the issues under the rug.

The Court does not discuss whether the Board was

right or wrong to rest its actions on the lack of a

duty to take any affirm ative action that might lead

to integration. The Court does not discuss the Board’s

deliberate decision to disregard the racial factors in

school site selection. Instead, m y brothers try to jus

tify the Board’ s action by finding a rational relation

ship between the sites selected and certain nonracial

factors, such as safety of access, the use of previous

ly acquired property, and coordination with the City

Planning Commission.* 63- No one doubts the relevance

G See footnote 1.

63 Many factors are relevant to the proper selection of school

sites: safety, accessibility, economical use of city property, co

ordination with city planners, and so on. But as Judge Tuttle

said in Davis v. Board of Commissioners of Mobile County, 5

Cir. 1966, 364 F.2d 896, 901: “ . . . there is a hollow sound

to the superficially appealing statement that school areas are

designed by observing safety factors, such as highways, rail

roads, streams, etc. No matter how many such barriers there

may be, none of them is so grave as to prevent the white chil

dren whose ‘area’ school is Negro from crossing the barrier and

enrolling in the nearest white school, even though it be several

intervening areas away.”

Judge Wisdom’s Dissent

16a

of such criteria. But a relationship otherwise rational

m ay he insufficient in itself to meet constitutional

standards—if its effect is to freeze-in past discrim ina

tion. For exam ple, a rational relationship exists be

tween literacy or citizenship tests (fairly admin

istered) and the right to vote. But we enjoin the use

of such tests when they freeze into a voters ’ regis

tration system the effects of past discrim ination.7

Again, a rational relationship may exist between pres

ervation of the peace and segregation o f schools.

That was Little R ock ’s argument. The Supreme

Court held that it was not enough.8

The Negro plaintiffs do not charge the Board with

bad faith. Nor do I. The Board acted on the advice of

its law yers; the lawyers relied on Briggs and on de

cisions in this circuit which followed Briggs.

At most, however, Briggs addressed itself to a

school board ’ s duty, not to its power. And the duty

dealt with was the Board’ s minimum, negative duty

to the individual complainant, not its duty in adminis

tering a public school system to take affirm ative ac

tion to provide equal educational opportunities to all

(N egro school children as a class) by eradicating the

vestiges and effects of the dual system of segregated

schools.