Jackson v. Marvell School District Motion for Permission to Appeal Upon the Original Papers, to Consolidate Appeals, and for Summary Reversal

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Marvell School District Motion for Permission to Appeal Upon the Original Papers, to Consolidate Appeals, and for Summary Reversal, 1969. 55c990f8-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d7ae4c9d-8046-4e43-9267-2789029768d6/jackson-v-marvell-school-district-motion-for-permission-to-appeal-upon-the-original-papers-to-consolidate-appeals-and-for-summary-reversal. Accessed March 10, 2026.

Copied!

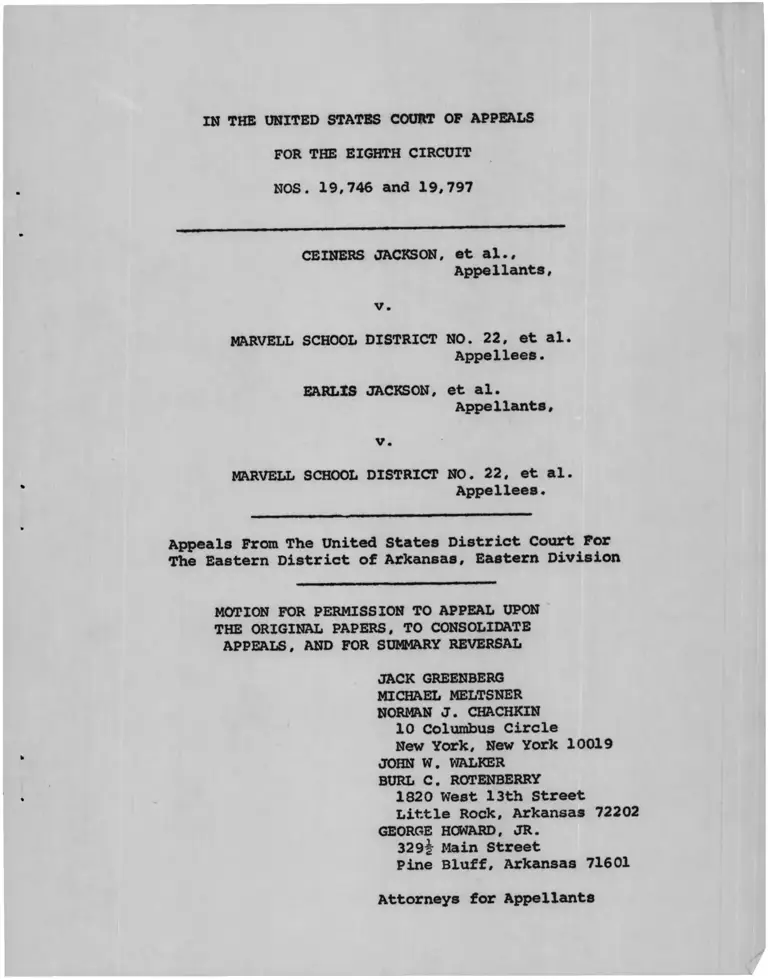

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 19,746 and 19,797

CEINERS JACKSON, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.

Appellees.

EARLXS JACKSON, et al.

Appellants,

v.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.

Appellees.

Appeals From The United States District Court For

The Eastern District of Arkansas, Eastern Division

MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO APPEAL UPON

THE ORIGINAL PAPERS, TO CONSOLIDATE

APPEALS, AND FOR SUMMARY REVERSAL

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL MELTSNER

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

BURL C. ROTENBERRY

1820 West 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

GEORGE HOWARD, JR.

329| Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 71601

Attorneys for Appellants

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 19,746 and 19,797

CEINERS JACKSON, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.

Appellees.

EARLIS JACKSON, et al.

Appellants,

v.

MARVELL SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 22, et al.

Appellees.

Appeals From The United States District Court For

The Eastern District of Arkansas, Eastern Division

MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO APPEAL UPON

THE ORIGINAL PAPERS, TO CONSOLIDATE

APPEALS, AND FOR SUMMARY REVERSAL

Appellants, by their undersigned counsel, respectfully pray pur

suant to Rule 30(f) of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure that

they be permitted to prosecute these appeals upon the original papers

filed in this cause in lieu of a printed appendix; that these separ

ate appeals from orders of the district court entered April 15, 1969

and June 13, 1969, respectively, be consolidated and considered to

gether; and further, that after consideration of the matters presente.

herein and the original papers, this Court summarily reverse the

judgments below and remand with instructions. In support of their

motions, appellants respectfully show this Court:

History of Case

1. The orders appealed from were entered following this Court's

remand in 1968. Jackson v. Marvell School District No. 22, 389 F.2d

740 (8th Cir. 1968).

2. Prior to September 1, 1965, appellees operated a dual schoo

system with separate school facilities and faculties for white and

Negro pupils (Id,, at 742).

3. During the 1965-66, 1966-67, 1967-68 and 1968-69 school

years, appellees operated the Marvell public schools pursuant to

freedom-o£-choice plans (Ibid.y Report of appellee school district

in No. H-66-C-35, dated June 13, 1968).

4. During the four years when appellee schooLdistrict operated

freedom-of-choice plans, no white student ever exercised ;a choice

to attend any all-Negro school; the following table shows the results

of the choice periods in each of the four years:

No. of % .of White

No. of % of Negro white Students

Total Negro Negro Students Students Students In All-

Students In In "white" In ‘white" In All- Negro

Year District Schools Schools Negro Schs . Schools

1965-66 1,700 17 1.0% 0 0%

1966-67 1,700 116 6.8% 0 0%

1967-68 1,566 207 13.2% 0 0%

1968-69 1,616 205 12.7% 0 0%

2

(Jackson v. Marvell School District No. 22, supra at 742;

Answers to Interrogatories in No. H-67-C-20, No. 25; Report of ap-

ellee school district in No. H-66-C-35, dated June 13, 1968).

5. During the school year 1965-66, appellees operated on one

site the predominantly white Marvell High School and Marvell Elemen

tary School; on another site, the all-Negro Tate High School and Tate

Elementary School; and three other small, all-Negro elementary school.

(Jackson v. Marvell School District No. 22, supra at 742-43). One

small all-Negro elementary school was closed prior to the 1966-67

school year (Answers to Interrogatories in No. H-67-C-20, No. 1);

another such school was closed prior to the 1967-68 school year (Id.,

No. 3). Appellees opened a new, predominantly white high school

facility in 1967-68, which is called the Marvell High School (Id.,

No. 4) and which is located two blocks from the former Marvell High-

Marvell Elementary complex (Tr. III~40). The predominantly white

high school grades were transferred from the old site to the new

building commencing with the 1967-68 school year.

1/ Appellants have previously furnished the Court, at the time

of filing their earlier Motion for Summary Reversal in No. 19,746

certified copies of the transcripts of the hearings below. The

transcript of the August 6, 1968 hearing is in two volumes and

will be referred to herein as Tr. I and II respectively; the

one-volume transcript of the March 31, 1969 hearing will be

referred to herein as Tr. III.

-3-

Proceedings Below

6. These appeals are taken from judgments issued in two cases

consolidated at the time of trial:

A. Ceiners Jackson v. Marvell School District No. 2 2 , No.

; H-66rC-35, was originally commenced on August 17, 1966, and

was the subject of the prior appeal herein, 8th Cir. No. 18,762,

opinion reported at 389 F.2d 740.

B. Earlis Jackson v. Marvell School District No. 22, No.

H _ 67 _ C - 20 , was commenced in July, 1967, seeking to enjoin ad

ditional construction by the school district on the site of

the (all-Negro) Tate High School on the grounds that such con

struction would perpetuate the dual school system operated by

appellees (Complaint in No. H-67-C-20, SISI II/ XI). The Com

plaint also sought relief consistent with this Court's ruling

in Kelley v. Al>-h.-imer, Arkansas School District No. 22, 378

F .2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967).

C. Plaintiffs in the second case subsequently withdrew

their request for an injunction against construction, which

had been completed, and stated that they would rely upon the

prayer for alternative relief consistent with Kelly (Letter

from undersigned counsel for appellants to Hon. Oren Harris,

U.S. District Judge, dated September 14, 1967, in No. H-67-C-20).

D. Subsequent to the May 27, 1968 decisions of the United

-4-

States Supreme Court in Green v. County School Board of New

Kent County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430; Monroe v. Board of Com

missioners of Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450; and Raney v.

Board of Education of the Gould. Arkansas School District/ 391

U.S. 443, plaintiffs in the original action filed a Motion for

Further Relief seeking to require appellee school district to

adopt and implement a plan of desegregation other than a

freedom-of-choice plan (Motion for Further Relief, No. H-66-C-35)

E. Because the issue in both cases was thus very similar,

they were consolidated at the August 6, 1968 hearing (Tr. I 4;

Order entered August 29, 1968, p. 2).

7. At the August 6, 1968 hearing, appellee Charles Cowsert,

Superintendent of the appellee school district (Tr. I 6-107; Tr. II

3-24) and Dr. Myron Lieberman, an expert witness called by appellants

(Tr. II 24-99), testified.

8. At the conclusion of the hearing, the district court ruled

from the bench (Tr. II 105-19) that appellees could not constitu

tionally continue to operate the Marvell, Arkansas public schools

pursuant to a freedom-of-choice plan:

Here we have an important school program

in a transitional state at a time when

our circuit has suggested this Court

recognize that there should be some time

and opportunity in this transitional

period for the development of a consti

tutional desegregation program. The

5-

thing that bothers me is just what the

court itself recognized, that there are

school boards and districts which simply

do not come to the reality of developing

the kind of a program that would be ac

cepted and approved and would provide the

objective which the Court said fourteen

years ago that we must come to ultimately

to do justice to all of those who are en

titled to an equal opportunity for public

education. So consequently the Circuit

Court of Appeals and this Court has given

an opportunity to this school district

for compliance, and I for one was hopeful

that the proposed plan for freedom-of-

choice would prove to be effective. . . .

. . . If you've got something that doesn't

work then we better look for something

else, and that is precisely what this Court

is going to do.

It is quite obvious to me that the freedom-

of-choice system is not working for this

district. It is clear from the testimony

and the record presented here that it will

not work, that you are not going to resolve

this problem with this kind of program. . .

. . . I am therefore going to cancel and

disapprove your proposed desegregation

plan of freedom-of-choice. . . .

. . . This is the 6th of August. To leave

the school district in that kind of a sus

pended situation at this time would, in my

judgment, be cruel and certainly unjustified.

So the Court is going to permit the school

district to proceed with the school program

under the present arrangement beginning with

the school system.

Then I am going to ask that by February the

1st that you submit another type of plan be^

cause I_am saying that for this school district

-6

under the circumstances freedom-of-choice

is out the window. There is no need to.

pursue a_ course that has already run out

and is no good.

(Tr. II 110-11. 113, 114, 116 [emphasis supplied]).

9. The district court thereafter entered a written order

August 29, 1968, which provided, inter alia:

2. The Plan of Desegregation of Marvell

School District No. 22 proposed on Nov

ember 25, 1966, and amended April 9, 1968,

is hereby disapproved as an unacceptable

method for the operation of this school

on a constitutional basis as interpreted

by the Supreme Court in Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County (No. 695

decided May 27, 1968).

3. The defendants are hereby ordered to

propose an alternate plan for the conver

sion of the school system to a unitary sy

stem in accordance with the decisions of

the Supreme Court made May 27, 1968, for

all students in attendance, and such plan

shall be presented to the Court on or be-

' fore February 1, 1969. Upon the filing

of said plan with the Court and after due

notice, a hearing will be held at a day

certain to be determined by the Court.

If Order entered August 29, 1968, p. 2)

10. On February 1, 1969, appellees filed a "Report" purportedly

in compliance with the district court's August 29th order. However,

rather than proposing an alternative plan to convert the Marvell

School District to a unitary school system, the Report stated that

"freedom of choice is the only feasible procedure in the assignment

-7

of students in this system; there is no feasible alternative" (Re

port of Defendants dated January 31, 1969, p. 1).

11. February 21, 1969, plaintiffs filed a Motion requesting

that continuation of freedom of choice not be permitted, that the

district be given five days in which to submit a plan in compliance

with the court's August 29, 1968, order, and that if the district

thereupon failed to present an acceptable plan, a receiver be ap

pointed by the court to operate the schools in conformity to the

2/

law.

12. The district court set March 31, 1969 for a hearing on

the matter. At that hearing appellees presented testimony by the

Superintendent (Tr. Ill 6-48), the Mayor of Marvell (Tr. Ill 48-66),

and two Negro school teachers employed by the district (Tr. Ill 66-

87). Appellants presented no evidence.

13. At the conclusion of the March 31, 1969 the district court

reversed its August 29th ruling:

There were many of us in the Congress

at the time [May 17, 1954] who felt

that the [Supreme] court arbitrarily

went way out in left field to change

the basic law which the Supreme Court

had ennunciated in 1896. . . .

. . . I have made it very clear that

as long as those who have the respon

sibility will undertake to bring about

compliance, it may be the impact is

2/ Cf. Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 724 (S. D. Ga. 1965).

-8-

greater on some than on others, but as

long as there can be shown an effort

towards bringing about compliance with

the basic constitutional requirements.

I have great compassion and sympathy

and I am going to do what I can as the

court to assist the leadership and en

couragement towards a_ constitutionally

operated system. . . when it is apparent

that there is no real effort being made

to bring about better methods and means

of compliance, this court is directed to

act with this kind of situation. . . .

. . . I want to compliment those who

have the responsibility in this diffi

cult problem. I can see a decidedly

changed attitude of the people through

out the school district who have children

and interested in their education . . . .

of course, the best solution, if it could

be done, would be to have an all high

school where everyone would be assigned

and an all elementary school. . .

. . . However, the school district is

still operating at this time a state-

imposed dual school system. No progress

has been noted in the disestablishing

of the Negro flchool as such. . . .

From the testimony, it is apparent that

through efforts of the mayor, members of

the city council and other leaders in

the school district, the novel approach

proposed might provide a solution of this '

most sensitive problem.

So since there appears to be a good-faith

effort in the proposal and the court being

persuaded that with the proper guidance

and leadership and understanding, patience

and tolerance, real progress can be realized,

I am going to give the district an opportun

ity . . .

-9-

I am going to modify my previous ruling

in which I disapproved the continuation

of freedom of choice in the operation of

the schools of this district, at least

for the time being, in an effort to see

just how the proposal of the district will

now work. . . .

If, from the reports, no progress is indi

cated and there is no prospects of achieving

a constitutionally operated school system,

the court will have to take notice and act

accordingly. After the results are reported

about May 15 and should it become necessary

for the court to consider this problem in

a different light, the parties will be given

another opportunity to be heard. . .

Now the court is going to approve this pro

cedure at the risk of being reversed by the

Circuit Court of Appeals. . . .

(Tr. Ill 99-101? 105-109) [emphasis supplied).

14. On April 15, 1969, the district court entered the order

which is the subject of the appeal in No. 19,746. That order pro

vided that the district should hold a special choice period between

April 15 and May 15, 1969 and report the results thereof to the dis

trict court on or before May 22, 1969, after which time the district

court would pass upon continued use of freedom-of-choice for the

1969-70 school year. On April 24, 1969, appellants filed a Notice

of Appeal.

15. On May 17, 1969, appellants filed a Motion for Permission

to Appeal Upon the Original Papers and for Summary Reversal in No.

19,746. June 6, 1969, this Court entered an order denying appellants

-10-

motion "without prejudice to renew after the filing of any additional

order as contemplated in the District Court's order of April 15, 1969-

16. On May 22, 1969, appellees filed a Report with the district

court which indicated the following results of the special choice

period:

Number white Number Negro Number Faculty memb:

students students of minority race

School choosinq choosinq assiqned

Marvell Elementary 251 117 0

Marvell High 261 98 1

Tate Elementary 36 660 4-2/3

Tate High 0 628 2-2/3

3/Turner Elementary^ 0 45 0

Total Number of Negro students choosing . .

Total Number of white students choosing . .

No. of Negro students choosing

"white" schools ......................

No. of white students choosing

"Negro" schools ......................

% of Negro students in "white" schools. . .

% of white students in "Negro" schools. . .

% of Negro students in all-Negro schools. .

1548

548

215

36

13.9 %

6.6 %

43.5 %

17. June 13, 1969, the district court entered an order approvir

the use of a freedom-of-choice plan of desegregation for the 1969-70

school year because it would "produce the maximum degree of desegre

gation possible at this time when compared with the reasonably pre-

3/ The school district proposed to close Turner and offer its

Negro students a second choice between Tate Elementary and

Marvell Elementary Schools.

-11-

dictable results of other alternatives." On June 17, 1969, appellants

filed a Notice of Appeal from the June 13, 1969 order, which appeal

has been docketed as No. 19,797

Reasons Why Summary Reversal Is Required

18. The appellees produced no evidence at the March 31, 1969

hearing which suggested that freedom of choice is any more likely

to disestablish the dual school system than it had been on August 29,

1968. In fact, the Superintendent's testimony on March 31 established

the contrary conclusion:

Q. How many can you say will attend the Tate

school pursuant to your solicitation for

the next school year?

A. How many can I guarantee?

Q . Yes.

A. I could not guarantee.

Q. How many can you reasonably estimate will

attend the Tate school?

A. Of course, the letter has not been circu

lated long enough for the people to discuss

it and to really make a decision. You real

ize this is a complete new situation, some

thing that has never happened in this community.

Q. Is it fair to say that if you have not been

able to get white pupils to transfer to the

black schools under the freedom of choice,

that you are not likely to get white pupils,

in any numbers anyway, to transfer to the

black schools this next year?

-12-

A. That is something that I would be quessing

at.

Q. I understand that.

A. In any great numbers?

Q . Yes.

A. I do not believe that the first shot of

integrating a school is going to be made

with any great degree of enthusiasm.

Q. So if any white students accepted your

offer or invitation it would be token more

or less, would it not, a few white pupils?

A. I think the first step, yes, sir, would be

to get a few.

Q. How long do you propose, in case the court

grants your request, to operate under the

freedom-of-choice procedure, or the solic

itation procedure?

A. Well, of course, we feel like if the be

ginning is made that that foundation could

be built on.

(Tr. Ill 17-18). The results of the special April 15 - May 15 choice

period confirm these expectations. Forty-three per cent of the Negro

pupils in the Marvell school system will continue to attend a segre

gated, all-Negro school. The Marvell schools remain identifiably

white by both student enrollment and faculty assignments; the Tate

schools are demonstrably Negro schools when judged by the same indici

Appellees by no conceivable test have met the "heavy burden upon the

board to explain its preference for an apparently less effective

-13-

method," Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, Virginia,

391 U.S. 430, 439 (1963).

19. The district court itself recognized (Tr. Ill 105-06) that

the most efficacious plan to eradicate the dual school system, Which

the court itself found still in existence after four years of freedp r

of-choice (Tr. Ill 106), was the plan recommended by appellants' ex

pert at the August, 1968 hearing: reorganization of the school sy

stem to provide for one district-wide high school and one district

wide elementary school. Yet the court below did not require the

appellees to adopt this plan; instead, free choice was continued.

20. Appellees' sole justification for failing to adopt the

reorganization approach suggested by appellants' expert, Dr. Lieber-

man, was community resistance and the possibility of what has come

to be known as "white flight":

Q. But really, I just want to captalize [sic]

this, you are making your request for ad

ditional time, and your request for per

mission to continue with freedom of choice

primarily because of the disproportions of

blacks to whites in the school district,is

that correct. That is to say that you have

too many Negroes in the school system and

too few whites to make integration attrac

tive to white parents and their children.

A. In one immediate shot?

Q . Yes.

A. Yes. The school is based on acceptance of

the people in that community. If you are

-14-

going to destroy or chase people out and cause

them to abandon their school, then the responsi

bility of the local people is to keep their schools

for the students.

(Tr. Ill 22-23. See also Tr. Ill 19-20, 26-27, 30-31; cf. Tr. Ill

39). It should be clear by now that this is no justification for

further delaying the achievement of a unitary school system.

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of City of Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U.S.

450, 459 (1968); Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ._, No. 26432

(5th Cir., April 15, 1969), p. 5; Kelley v. Altheimer, Arkansas

School District No. 22. Civ. No. PB-66-C-10 (E.D.’Ark,, March 24,

1969), pp. 8-9.

21. There is no evidence in the record from which the district

court could have concluded that the request to continue free choice

was a "good-faith effort" (Tr. Ill 105) to bring about a unitary

school system which reflected *’a decidedly changed attitude" (Tr.

Ill 107) on the part of the school district. The district waited

until nine days before the hearing — well after it proposed on

February 1 to continue free choice — to send out the letter to

white parents (Tr. Ill 9). Even then, as noted, the response was

uninspiring. Furthermore, the district very clearly has acted in

bad faith with regard to faculty desegregation. Despite this Court's

instruction on February 9, 1968 that "the Board should be required

to take affirmative action to (1) encourage voluntary transfers . . .

-15-

(2) assign members of the faculty and staff from one school to an

other ," Jackson v . Marvell School District No. 22, supra at 745, no

such teacher assignments have ever been made "against their wishes"

(Tr. Ill 13). The totally inadequate performance of the district

to date results in the continued racial identifiability of its school

At any rate, the time for mere "good faith" has passed.

At this very, very late date in the

glacial movement toward school racial

integration, it should no longer be

an issue of good faith.

United States v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer, 396 F.2d 44, 49 (5th

Cir. 1968); accord, Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., _____^

F.2d___No. 26450 (5th Cir., May 28, 1969) (slip opinion at p. 16).

22. Finally, the remarks of the district court reflect applic

ation of an improper legal standard:

. . . I have made it very clear

that as long as those who have the

responsibility will undertake to

bring about compliance, it may be

the impact is greater on some than

others, but as long as there can be

shown an effort towards bringing

about compliance with the basic con

stitutional requirements I have

great compassion and sympathy and

I am going to do what I can as the

court to assist the leadership and

encouragement towards a constitu

tionally operated system.

(Tr. Ill 100-01). What is required at this late date is far more

than an undertaking or an effort towards compliance with the Con-

-16-

stitution. Compliance in deed as well as in speech must be achieved

now. This Court has recently reiterated that "the time for transi

tion has now passed and that these problems should have been worked

out long ago." Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County, Ark

ansas, No. 19,404 (8th Cir., May 9, 1969), p. 11. Cf. Kemp, v. Beasle;

389 F.2d 178, 185 n.10 (8th Cir. 1968) and accompanying text. "We

are firm that a point has been reached in the process of school de

segregation 'where it is not the spirit but the bodies which count.'

Montgomery County Board of Education, et al., on petitions for re

hearing en banc, 5 Cir. 1968, __ F.2d __ [No. 25865, November 1, 1968]

(dissenting opinion p. 6)." United States v. Indanola Municipal

Separate School District. No. 25655 (5th Cir., April 11, 1969), p. 12

23. Summary reversal, while an extraordinary procedure, has

been found to be particularly suitable and necessary in school de

segregation cases "because of the importance in school administration'

for having an immediate end to any doubt with respect to procedures

to be followed for the next school year," Gaines v. Daugherty County

Bd. of Educ., 392 F.2d 669, 672 (5th Cir. 1968). This is particu

larly true where, as here, the normal appellate process would delay

consideration of an appeal beyond the start of the following school

term. Summary reversal has been found to be proper in numerous such

cases. See generally, Acree v. County Bd. of Educ. of Richmond

County, No. 25136 (5th Cir., August 31, 1967); Banks v. St. James

-17-

Parish School Bd., No. 25375 (5th Cir., Nov. 20, 1967); Bivans.v.

Board of Educ. and Public Orphanage for Bibb County,, No. 25743 (5th

Cir., May 24, 1967); Thomie v. Houston County Bd. of Educ^, No. 24754

(5th Cir., May 24, 1967); George v. Davis. and Carter v. West Felic

iana Parish School Bd., No. 24860 and 24861 (5th Cir., July 24, 1967,

and Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., No. 25092 (5th Cir., August

4, 1967).

24. Unless this Court summarily reverses the orders below, an

other school year will go by before a unitary school system is im

plemented in this district. A year has already been lost because

the district court determined in August, 1968 that it was "too late"

to implement any plan other than freedom of choice. Despite the

clear import of the Green, Monroe and Raney decisions for this dis

trict, no hearing was held between the date of those decisions,

May 27, 1968, and August 6, 1968. Consequently, even though the cour

below determined upon such hearing that freedom-of-choice was an un

constitutional plan of operating the Marvell public schools, it

ordered continuation of free choice during the 1968-69 school year

because of the district's claimed inability to implement a different

kind of plan between August 6 and the opening of school. But see,

e.q., Tr. II 44-46. The district court has now approved continued

use of freedom of choice despite the court's own recognition that

reorganization of the school system would immediately end the dual

-18-

school system, despite the continued clear racial identifiability

of the Tate and Marvell schools as Negro and white schools, re

spectively and despite the continuation of Tate High School as

an all-Negro school. The only argument with which the Board has

attempted to justify its preference for a less effective method

of desegregation than grade reorganization is the specter of

"white flight." Reliance on such arguments is constitutionally

forbidden, as this Court itself has had occasion to point out.

Aaron v. Cooper. 257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958). We respectfully

urge this Court to act in order to prevent the irretrievable loss

of Negro students' constitutional rights for yet another year.

WHEREFORE, for all the reasons set forth above, appellants <

respectfully pray that they be permitted to prosecute these ap

peals upon the original papers in lieu of a printed appendix;

that their Motion for Summary Reversal in No. 19,746 be renewed;

that these appeals be consolidated and determined together; and

that this Court summarily reverse the orders entered below, and

remand this cause with instructions to the district court to

order the implementation of a school reorganization plan or any

other equallv effective plan which desestablishes the dual school

system and substitutes therefor a unitary nonracial school system

-19-

in the Marvell School District No. 22 effective with the 1969-70

school year.

Respectfully submitted.

JACK GREENBERG

MICHAEL MELTSNER

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York. New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

BURL C. ROTENBERRY

1820 West 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

GEORGE HOWARD, JR.

329g Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 71601

Attorneys for Appellants

-20-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on the day of June, 1969 I served

a copy of the foregoing Motion for Permission to Appeal Upon the

Original Papers, To Consolidate Appeals, and for Summary Reversal

upon Robert V. Light, Esq., 1100 Boyle Building, Little Rock,

Arkansas 72201 and Charles B. Roscopf, Esq. 417 Rightor Street,

Helena, Arkansas 72342, attorneys for appellees, by United States

air mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants