Plaintiffs' Memorandum in Opposition to Defendants' Motion to Dismiss; Application of the United States for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae; Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 9, 1987

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Memorandum in Opposition to Defendants' Motion to Dismiss; Application of the United States for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae; Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1987. 2bd9aa2b-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d7b5d335-ee1e-4ea2-a20b-4726920fd623/plaintiffs-memorandum-in-opposition-to-defendants-motion-to-dismiss-application-of-the-united-states-for-leave-to-file-brief-as-amicus-curiae-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed March 06, 2026.

Copied!

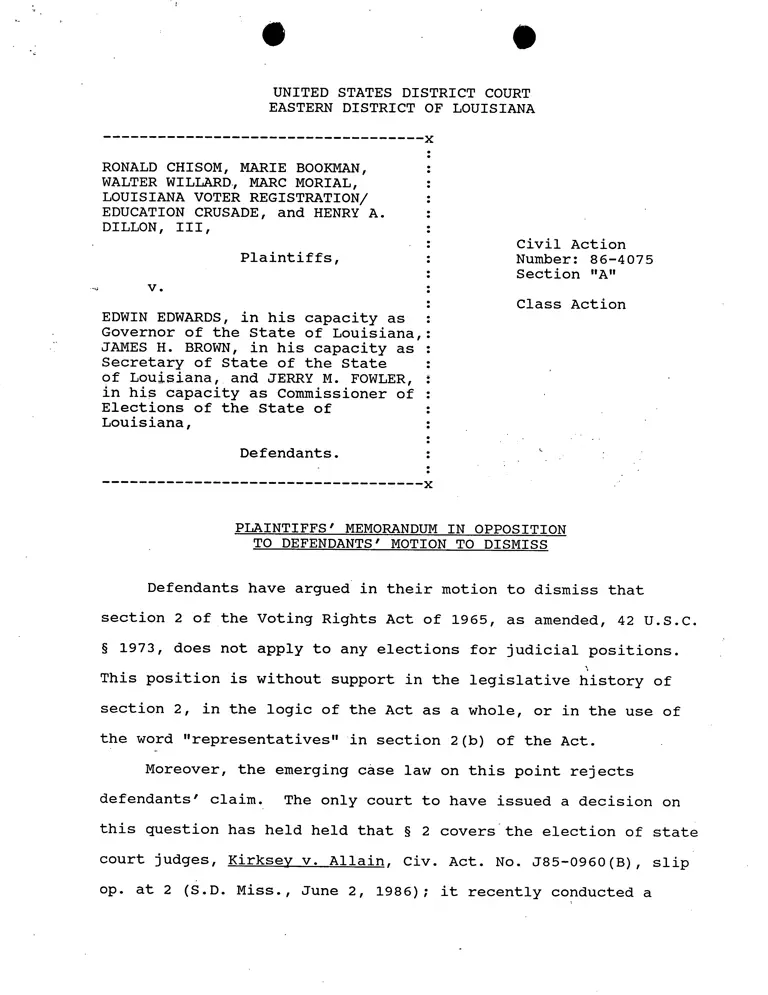

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, MARIE BOOKMAN,

WALTER WILLARD, MARC MORIAL,

LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/

EDUCATION CRUSADE, and HENRY A.

DILLON, III,

Plaintiffs,

V .

Civil Action

• Number: 86-4075

Section "A"

Class Action

EDWIN EDWARDS, in his capacity as :

Governor of the State of Louisiana,:

JAMES H. BROWN, in his capacity as :

Secretary of State of the State

of Louisiana, and JERRY M. FOWLER,

in his capacity as Commissioner of :

Elections of the State of

Louisiana,

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS' MEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION

TO DEFENDANTS' MOTION TO DISMISS

Defendants have argued in their motion to dismiss that

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973, does not apply to any elections for judicial positions.

This position is without support in the legislative history of

section 2, in the logic of the Act as a whole, or in the use of

the word "representatives" in section 2(b) of the Act.

Moreover, the emerging case law on this point rejects

defendants' claim. The only court to have issued a decision on

this question has held held that § 2 covers the election of state

court judges, Kirksey v. Allain, Civ. Act. No. J85-0960(B), slip

op. at 2 (S.D. Miss., June 2, 1986); it recently conducted a

week-long trial regarding Mississippi's use of multimember, at-

large, numbered post judicial districts for the election of

chancery, circuit, and county court judges. 1 And in Martin v.

Alexander, Civ. Act. No. 86-1048-CIV-5 (E.D.N.C.), a case

challenging the election scheme for the North Carolina superior

court, the United States has recently sought leave to file a

brief amicus curiae supporting the position of plaintiffs and

plaintiff-intervenors that § 2 applies to the election of

judges. 2

I. The Legislative History of Section 2 Shows

Congress' Intent To Cover All Elections,

Including Elections for Judicial Positions

Section 2, as originally enacted in 1965, provided, in

pertinent part, that

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or

applied by any State ... to deny or abridge the right

of any citizen of the United States to vote on account

of race or color ....

42 U.S.C. § 1973. The clear import of section 2 was to outlaw

racial discrimination in all voting. In passing the 1965 Act,

Congress sought "to counter the perpetuation of 95 years of

pervasive voting discrimination," City of Rome v. United States,

446 U.S. 156, 182 (1980), by "creat[ing] a set of mechanisms for

dealing with continued voting discrimination, not step by step,

lA copy of the district court's unpublished order appears in

Appendix A to this Memorandum.

2A copy of the United States' application and brief appears

in Appendix B to this Memorandum.

2

•

but comprehensively and finally." S. Rep. No. 97-417-, p. 5

(1982). Nothing in either the language of the Act or its

legislative history supports defendants' claim that voting

standards, practices, or procedures involving the election of

judges were somehow excluded. Nor have defendants provided any

basis for concluding that Congress intended to permit continued

racial discrimination in voting as long as the challenged

practice concerned voting for a judicial, rather than a

legislative or executive, office.

The Voting Rights Act originated as H.R. 6400, a bill

introduced by Representative Cellar, the Chairman of the

Judiciary Committee, but drafted by the Administration. That

bill provided that "[n]o voting qualification or procedure shall

be imposed or applied to deny or abridge the right to vote on

account of race or color." H.R. 6400, § 2, reprinted in Voting

Rights: Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House Judiciary

Comm., 89th Cong., 1st Sess., 862, 862 (1965) [hereinafter cited

as "House Hearings"]. It further provided that: "The term 'vote'

shall have the same meaning as in section 2004 of the Revised

Statutes (42 U.S.C. 1971(e))." H.R. 6400, § 11(c), reprinted in

House Hearings at 865. Section 1971(e), enacted as part of the

Civil Rights Act of 1960, provided that:

When used in the subsection, the word "vote" includes

all action necessary to make a vote effective

including, but not limited to, registration or other

action required by State law prerequisite .to voting,

casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted and

included in the appropriate totals of votes cast with

respect to candidates for public or party office and

propositions for which votes are received in an

3

election .

Thus, H.R. 6400 expressly contemplated protecting voters in any

election involving candidates for "public office" (which a

judgeship indubitably is). Moreover, the fact that the bill

included elections in which no candidate was running (that is,

elections at which "propositions," such as bond issues, are

decided) shows that its focus was on the right of all citizens to

participate in the electoral process, rather than on the

particular question to be determined at a given election.

The Supreme Court has held that, "in light of the extensive

role the Attorney General [Nicholas Katzenbach] played in

drafting the statute and explaining its operation to Congress,"

his construction of the Act is entitled to great weight. United

States v. Sheffield Board of Commissioners, 435 U.S. 110, 131 &

n. 20 (1978); see Allen v. Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 566-

69 (1969); S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 17 & n. 51 (1982). Attorney

General Katzenbach made clear that "[e]very election in which

registered electors are permitted to vote would be covered" by

the Act. House Hearings at 21. 3

3Rep. Kastenmeier noted that one alternative bill had

defined "election" to include

"any general, special, primary election held in any

State or political subdivision thereof solely or

partially for the purpose of electing or selecting a

candidate to public office, and any election held in

any State or political subdivision thereof solely or

partially to decide a proposition or issue of public

law."

The following exchange then occurred:

4

The result of this discussion of the scope of the Act's

intended protection was the inclusion, in the bill ultimately

passed, of an express definition:

The terms "vote" or "voting" shall include all action

necessary to make a vote effective in any primary,

special, or general election, including, but not

limited to, registration, listing pursuant to this

subchapter, or other action prerequisite to voting,

casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted

properly and included in the appropriate totals of

"Mr. KASTENMEIER. First, I am wondering if you

would accept that definition.

Mr. KATZENBACH. Yes.

Mr. KASTENMEIER. Secondly, I am wondering if you

feel it might aid to put a definition of that sort in

the administration bill or whether it is unnecessary.

Mr. KATZENBACH. I don't think it is necessary,

Congressman, but I cannot think of any objection that I

would have to using that definition or something very

similar to it."

House Hearings at 67 (emphasis added). Katzenbach had a similar

colloquy with Rep. Gilbert:

"Mr. GILBERT. ... You refer in section 3 of the

bill [which dealt with tests and devices] to Federal,

State and local elections. Now, would that include

election for a bond issue?

Mr. KATZENBACH. Yes.

Mr. GILBERT. Now, my bill, H.R. 4427. I have a

definition. I spell out the word 'election' on page 5,

subdivision (b). I say:

"Election" means all elections, including

those for Federal, State, or local office and

including primary elections or any other

voting process at which candidates or

officials are chosen. "Election" shall also

include any election at which a proposition

or issue is to be decided.

Now, I have no pride or authorship but don't you

think we should define in H.R. 6400 [the

Administration's bill] the term 'election'?

Mr. KATZENBACH. I would certainly have no

objection to it and I think it should be broadly

defined.

House Hearings at 121.

5

votes cast with respect to candidates for public or

party office and propositions for which votes are

received in an election.

42 U.S.C. § 19731(c)(1) (emphasis added). Nothing in the

language or structure of the Voting Rights Act suggests that this

broad definition does not apply to § 2 lawsuits. Indeed, §

19731(c)(1) represents the best evidence that Congress meant to

include all elections when it prohibited denying or abridging

"the right of any citizen of the United States to vote" in § 2.

Attorney General Katzenbach's contemporaneous interpretation

of the scope of the Act and the definition of "voting" the Act

employs are wholly at odds with defendants' attempt to restrict

the definition of public office to only legislative or executive

positions. Given Congress' "intention to give the Act the

broadest possible scope," Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393

U.S. 544, 566-67 (1969), defendants' cramped reading is

particularly unjustified. As one court has noted, "the Act

applies to all voting without any limitation as to who, or what,

is the object of the vote." Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410

(E.D.N.C. 1985) (three-judge court) (emphasis in original),

aff'd, U.S. , 91 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986).

There is an additional reason to conclude that § 2 has

always applied to judicial elections. As originally enacted, § 2

"simply restated the prohibitions already contained in the

Fifteenth Amendment ...." City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55,

61 (1980) (plurality opinion); see also S. Rep. No. 97-417, pp.

6

•

17-19 (1982). 4 The Fifteenth Amendment clearly applies to claims

of intentional racial vote dilution in judicial elections. Voter

Information Project v. City of Baton Rouge, 612 F.2d 208 (5th

Cir. 1980). Thus, § 2, in its original form, would also have

reached claims of vote dilution in judicial elections. Indeed,

the contrary result would plainly be absurd: § 2 would clearly

bar a state's passage of a law restricting the franchise in

judicial elections only to white voters.

Defendants therefore bear the burden of showing that later

amendments to § 2, all ostensibly intended to broaden the Act's

scope, somehow narrowed the scope of the Act to exclude judicial

elections. Their analysis of the legislative history of these

subsequent amendments fails entirely to meet this burden.

One continuing thread in the legislative history is

Congress' discussion of the increasing number of black elected

officials in jurisdictions that historically had discriminated

against minority voters. While Congress has never explicitly

discussed progress in integrating the judiciary, its frequent

reliance on data that includes judicial positions shows

implicitly that judicial elections fall within the scope of § 2.

In 1975, Congress relied for its figures regarding the number of

4The Supreme Court has termed the Senate Report an

"authoritative source" concerning Congress' intent in amending

section 2. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. , 92 L.Ed.2d 25, 42

n. 7 (1986).

The House Report uses similar terminology. See, e.g., H.R.

Rep. No. 97-227, p. 4 (1982) ("electoral process"); id. at 18

(condemning practices that deprive minorities of the chance to

elect the "candidate of their choice").

7

black elected officials on a report prepared by the U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights. See, e.g., S. Rep. No. 94-295, p. 14

(1975). That report explicitly included judges in its summaries

of the number of black elected officials. See, e.g., U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights Act: Ten Years

After 377 (table containing the number of black elected county

officials in counties with 25% or more black populations, column

listing "Law Enforcement Officials" includes, among others,

"judges" and "justices of the peace"). Similarly, in 1982,

Congress relied on figures provided by the Joint Center for

Political Studies. See H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, pp. 7-9 (1982).

These figures also explicitly included, as relevant elected

officials, elected black judges. See, e.g., Joint Center for

Political Studies, Black Elected Officials: A National Roster,

1980, at 4-5, 14-15 (1980). Of particular salience to this case,

the Joint Center report on which Congress relied included black

elected judges in Louisiana within its total of black elected

officials within the state. See id. at 123 and 132. 5

5The Civil Rights Commission continues to include elected

minority jurists within its descriptions of black elected

officials. See, e.g., U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights, The Voting

Rights Act: Unfulfilled Goals 27-28 (1981) (stating that blacks

were rarely elected to "law enforcement positions (including

sheriffs and judges)") (emphasis added); id. at 31, 34, 35

(tables showing number of elected black law enforcement

officials--a designation that includes judges); id. at 37 (table

showing Hispanic elected county judges during 1979-1980). The

Census Bureau's treatment of elected black judges also counts

them as black elected officials. See, e.g., U.S. Dept. of

Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the

United States 1986, at 252 (106th ed. 1985) (in table no. 428,

"Black Elected Officials, by Office, 1970 to 1985, and by Region

and State 1985," column 3, "Law enforcement" includes "Judges,

8

•

The 1982 amendments, which gave § 2 its current shape, lend

additional support to plaintiffs' position. The Senate Report

refers to minorities who "now hold public office" and "the

presence of minority elected officials." S. Rep. No. 97-417, pp.

5 & 16 (1982). Its repeated use of phrases such as "an equal

chance to participate in the electoral process," e.g., id. at 16,

and "an equal opportunity ... to elect candidates of their

choice," e.g., id. at 28, is entirely at odds with defendants'

suggestion that Congress intended to exclude, sub silentio, one

particular aspect of the electoral process, and one particular

kind of candidate, from the protection of section 2, which

extended to "all stages of the political process," H.R. Rep. No.

97-227, p. 14 (1982) (emphasis added).

Ultimately, defendants' claim that section 2 does not cover

judicial elections rests on the presence of one word,

"representatives," in amended section 2(b). 6 According to

defendants, Congress deliberately chose this word to

only elections involving candidates for positions in

"representative" branches of the government would be

the protection of section 2.

ensure that

the

subject to

magistrates, constables, marshals, sheriffs, justices of the

peace, and other").

6That section states that a violation of section 2(a) is

shown if a plaintiff proves "that the political processes leading

to nomination and election in the State or political subdivision

are not equally open to participation by members of a class of

citizens protected by subsection (a) of this section in that its

members have less opportunity that other members of the

electorate to participate in the political process and to elect

representatives of their choice."

9

Section 2(b) was added as a compromise in the Senate to make

clear that the results test could not be satisfied merely by

demonstrating the absence of proportional representation. See S.

Rep. No. 97-417, p. 2 (1982). There is absolutely nothing in the

statute or legislative history to support the view that use of

the word "representative" was meant to restrict § 2's protection

to a subset of elections. The choice of the word

"representatives," as opposed to, for example, the words

"candidate" or "elected official," which are used extensively in

the legislative history, see, e.g., id. at 16, 28, 29, 30, 31,

and 67, simply cannot carry the weight defendants attempt to pile

onto it. In 1982, as in 1965, the Voting Rights Act applies to

every election.

II. The Overall Structure of the Voting Rights

Act Requires that Section 2 Be Construed To

Cover Judicial Elections

• It is undisputed that judicial elections are subject to the

preclearance provisions of section 5 of the Voting Rights Act.

Kirksey V. Allain, 635 F. Supp. 347 (S.D. Miss. 1986) (three-

judge court); Haith V. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985)

(three-judge court), aff'd, U.S. , 91 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986).

The import of defendants' position in this case is that although

a jurisdiction subject to preclearance may be stopped from

instituting a new practice regarding judicial elections if that

practice has "the effect of denying or abridging the right to

vote on account of race or color," 42 U.S.C. § 1973c (section 5),

10

the jurisdiction is perfectly free to continue using a pre-

existing system of judicial elections that "results in a denial

or abridgement of the right ... to vote on account of race or

color," 42 U.S.C. § 1973 (section 2).

Defendants' argument rests on the proposition that a

violation of section 5 is not necessarily a violation of section

2. Congress has squarely rejected this proposition:

Under the Voting Rights Act, whether a discriminatory

practice or procedure is of recent origin affects only

the mechanism that triggers relief, i.e., litigation

[under section 2] or preclearance [under section 5].

The lawfulness of such a practice should not vary

depending on when it was adopted, i.e., whether it is a

change

H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, p. 28 (1982). 7 Sections 2 and 5 are

intended to complement each other. Section 5 provides an

additional procedural mechanism for protecting voters in areas

with an egregious history of voting discrimination; it does not,

however, use an inconsistent standard of review.

7Both Congress and the Attorney General have interpreted the

protections of sections 5 and 2 as coextensive with respect to

the closely related question whether the Attorney General must

object under section 5 to practices that also violate section 2.

See, e.g., S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 12 n. 31 (1982); 128 Cong. Rec.

S7095 (daily ed., June 16, 1982) (remarks of Sen. Kennedy); 128

Cong. Rec. H3841 (daily ed. June 16, 1982) (remarks of Rep.

Sensenbrenner and Rep. Edwards); Voting Rights Act: Proposed

Section 5 Regulations, Report of the Subcomm. on Civil and

Constitutional Rights of the House Judiciary Comm., 99th Cong.,

2d Sess. 5 (1986); Nomination of William Bradford Reynolds to be

Associate Attorney General of the United States: Hearings Before

the Sen. Judiciary Comm., 99th Cong., 1st Sess. 119 (1985); 52

Fed. Reg. 498 (1987) (to be codified at 28 C.F.R. § 51.55(b) (the

Attorney General will withhold § 5 preclearance from changes that

violate § 2); 52 Fed. Reg. 487 (1987) (when facts available at

preclearance proceeding show that the change "will result in a

Section 2 violation, an objection will be entered.")

11

Moreover, the analysis of the three-judge court in Haith

clearly supports applying section 2 as well as section 5 to

judicial elections. Haith expressly relied on the language of

section 2 to support its conclusion that "the Act applies to all

voting without any limitation as to who, or what, is the object

of the vote." Haith V. Martin, 618 F. Supp. at 413 (emphasis in

original). Thus, no basis exists in the structure of the Act

itself for concluding that only section 5 applies to judicial

elections.

Finally, defendants argue that judicial elections are

covered only by the Fifteenth Amendment, which requires a showing

of discriminatory intent. For this Court to accept defendants'

arguments, it would have to hold that, although § 2 reaches

intentional discrimination in judicial elections, 8 it does not

reach such discrimination in the absence of a finding of

discriminatory intent. But Congress stated that making the

presence or absence of discriminatory intent a dispositive issue

in a § 2 suit "asks the wrong question." S. Rep. No. 97-417, p.

36 (1982). Coverage of judicial elections therefore simply

cannot turn on the intention of the state officials who enacted

or maintain the practices being challenged.

8Although § 2 was amended to make clear that a plaintiff

need not show discriminatory intent to win a vote-dilution suit,

amended § 2 obviously continues to reach claims of intentional

discrimination. See, e.g., Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 640 F.

Supp. 1347, 1353 (M.D. Ala. 1986); cf. Major v. Treen, 574 F.

Supp. 325, 344 (E.D.La. 1983) (three-judge court). Thus, it

necessarily continues to reach claims of intentional vote

dilution in judicial elections. Cf. Voter Information Project v.

City of Baton Rouge, 612 F.2d at 211-212.

12

III. Defendants' Reliance on Wells v. Edwards and

Morial v. Judiciary Commission is Misguided

It is true that the principle of one-person, one-vote first

announced in Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964), does not

apply to judicial elections. See Wells V. Edwards, 409 U.S. 1095

(1973) (per curiam), summarily aff'g, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La.

1972) (three-judge court). Defendants claim this means that

section 2 is similarly unconcerned with judicial elections. •But

the fact that the Constitution does not require strict population

equality among judicial districts says virtually nothing about

whether the Voting Rights Act prohibits judicial apportionment

schemes that result in black voters being denied an equal

opportunity to participate effectively.

. The Voting Rights Act has always been interpreted as

providing protection beyond that afforded by the Fourteenth

Amendment-based principle of one-person, one-vote. For example,

it reaches practices wholly unrelated to the effects of

apportionment. 9 But ei/eli with respect to questions of

apportionment, Congress intended that the Voting Rights Act be

interpreted more broadly than Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533

9See, e.g., Toney v. White, 476 F.2d 203, 207-08 (5th Cir.)

(use of voter purge statute), modified and aff'd, 488 F.2d 310

(5th Cir. 1973) (en banc); Harris v. Graddick, 615 F. Supp. 239

(M.D. Ala. 1985) (appojntment of polling officials); Goodloe v.

Madison County Board of Election Commissioners, 610 F. Supp. 240

(S.D. Miss. 1985) (invalidation of absentee ballots); Brown v.

Dean, 555 F. Supp. 502 (D.R.I. 1982) (location of polling

places).

13

S

(1964), because it knew that "population differences were not the

only way in which a facially neutral districting plan might

unconstitutionally undervalue the votes of some." S. Rep. No.

97-417, p. 20 (1982). Thus, for example, Major v. Treen, 574

F.Supp. 325, 349-55 (E. D. La. 1983) (three-judge court), rejected

a congressional districting plan that fractured New Orleans'

large black community into two districts despite the plan's

compliance with the one person, one vote standard. The fact that

the plan submerged concentrations of black voters within white

majorities, thereby making it impossible for blacks to elect the

candidates of their choice, was itself prohibited.

Defendants also rely heavily on Morial v. Judiciary

Commission of the State of Louisiana, 565 F.2d 295 (5th Cir.

1977) (en banc), cert. denied, 435 U.S. 101,3 (1978). There, the

Court of Appeals held that the duties of judges and the duties of

more political officials differed in ways that justified placing

restrictions on candidates for judicial office that were not

imposed on candidates for other offices. Defendants claim that

this means that the right to vote in judicial elections is more

restricted than the right to vote in other elections.

That position confuses the question as to how judges and

candidates for judicial office should conduct themselves with the

entirely different question of what rights should be accorded to

voters given a state's decision to make judicial positions

elective. First, as we have already discussed, the Act has

always been intended to cover even elections which did not

14

involve candidates for office at all. Thus, the nature of the

office up for election cannot determine whether the Act applies.

The Act focuses on the rights of black voters, not the interests

of black candidates. 1° Second, neither the scope of official

duties nor the level of official performance has any bearing on

the jurisdictional question currently before this Court. Both

Houses of Congress have expressly rejected the concept that a

voting rights plaintiff must show unresponsiveness on the part of

elected officials to establish a violation of section 2. See S.

Rep. No. 97-417, p. 29, n. 116 ("Unresponsiveness is not an

essential part of plaintiff's case."); H.R. Rep. No. 97-227, p.

30 (1982) (same). In light of Congress' decision that

responsiveness or its absence is not the touchstone of a section

2 violation, it makes no sense to suggest, as defendants do, that

section 2 should not cover judicial elections because a trial

judge is not supposed to represent the views of the electorate.

Major v. Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325, 337-38 (E.D. La. 1983) (three-

judge court), implicitly recognized that the interests and rights

of black voters in judicial and nonjudicial elections are

identical when it relied on an analysis of polarized voting which

included, among the 39 elections studied, at least 13 involving

judicial positions.

By deciding to make positions on its Supreme Court elective,

the State of Louisiana has decided that the people shall choose

1°The Morial Court explicitly stated that the challenged

statute had only a negligible impact on the constitutional

interests of voters. See 565 F.2d at 301-02.

15

the Justices. Having made this decision, the State lacks the

power to structure its judicial elections in a fashion that

results in black citizens having a lesser opportunity to elect

the judicial candidates of their choice than white citizens

enjoy. 11

IV. Conclusion

Defendant's construction of section 2 reflects virtually

total inattention to Congress' primary purpose in enacting,

extending, and amending the Voting Rights Act: to ensure that all

citizens have an equal chance to participate in all phases of the

electoral process. S. Rep. No. 97-417, p. 16 (1982). It rests

on a cramped and artificial reading of one word in the second

subsection to overcome the clear meaning of the section as a

whole: that no voting practice or procedure shall be imposed or

applied which results in a denial or abridgement of the right to

11Cf. S. Rep. No. 97-417, pp. 6-7 (1982) (abolishing

elective posts may "infringe the right of minority citizens to

vote and to have their vote fully count"). Thus, even though an

office need not be representative, in the sense that a State is

not required in the first place to permit citizens to choose the

person who fills it, the Voting Rights Act prohibits practices

that diminish the opportunity of minority citizens to decide who

fills it once the decision has been made that it should be

elective.

16

vote on account of race. Thus, this Court should deny

defendants' motion to dismiss and should hold that section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act applies to judicial elections.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

LANI GUINIER

PAMELA S. KARLAN

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

ROY RODNEY

643 Camp Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

March , 1987

17

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

631 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

RON WILSON

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

S

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

KELLY ALEXANDER, JR., et al., )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

and )

)

NORTH CAROLINA ASSOCIATION )

OF BLACK LAWYERS, CALVIN E. )

MURPHY, T. MICHAEL TODD, )

and RALPH GINGLES, )

)

Plaintiff-Intervenors, )

)

v. )

)

JAMES G. MARTIN, et al., )

)

Defendants. )

)

CIVIL ACTION NO.: 86-1 048-CIV-5

APPLICATION OF THE UNITED STATES FOR LEAVE

TO FILE BRIEF AS AMICUS CURIAE

The United States respectfully requests leave of this

Court to file a brief as amicus curiae addressing the issue

of whether judicial election procedures that discriminate on

the basis of race, color or language minority status are

subject to challenge under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.0 §§1973.

Respectfully submitted this 9th day of March, 1987.

SAMUEL T. CURRIN WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

United States Attorney Assistant Attorney General

GERLAD W. J0f.ILS

PAUL F. HANCOCK

RICHARD J. RITTER

Attorney, Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

10th & Constitution Ave.,

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 272-6300

N.W.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

KELLY ALEXANDER, JR., at )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

and )

) CIVIL ACTION NO.: 86-1048-CIV-5

NORTH CAROLINA ASSOCIATION )

OF BLACK LAWYERS, CALVIN E. )

MURPHY, T. MICHAEL TODD, )

and RALPH GINGLES, )

)

Plaintiff-Intervenors, )

)

v. )

)

JAMES G. MARTIN, at al.., )

)

Defendants. )

)

• BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTRODUCTION

This case presents, inter alia, the question whether

judicial election procedures that discriminate on the basis of

race, color or language minority status are subject to challenge

under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42

U.S.C. SS 1973. The Plaintiffs, joined by the Plaintiff-

Intervenors, allege in their complaints that the State's method

of electing Superior Court judges violates their rights under

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. On

January 8, 1987, the Defendants moved to dismiss the Plaintiffs'

Section 2 claims arguing that Section 2 does not apply to

judicial elections.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on March 9, 1987, I served a copy

of the foregoing Application Of The United States For Leave To

File Brief As Amicus Curiae on all counsel of record by

mailing, postage prepaid, a copy to the following persons:

Lacy Thornburg

James Wallace, Jr.

Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General

P. O. Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

C. Allen Foster

Robert G. McIver

Foster, Conner, Robson & Gumbiner

104 North Elm Street

P. O. Drawer 20004

Greensboro, North Carolina 27420

Leslie J. Winner

Ferguson, Stein, Watt, Wallas &

. Adkins

Suite 730, East Independence Plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Angus Thompson

Attorney at Law

122 West Elizabethtown Road

Lumberton, North Carolina 28358

RICHARD J. TTER

Attorney, Vbting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

10th & Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 272-6300

2

I. INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

The United States has the primary responsibility for

enforcing the Voting Rights Act and thus has a substantial

interest in ensuring that the Act is construed properly. In

addition, the United States is a defendant in a related action

under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act that is pending before

the United States District Court for the District of Columbia.

State of North Carolina v. United States, C.A. No. 86-1490. 1 In

that action the State of North Carolina is seeking a declaratory

judgment that certain changes in its method of electing Superior

Court judges do not discriminate unlawfully on the basis of race

or color under the Act. The question of the coverage of judicial

elections under the Voting Rights Act is therefore of direct

interest to the United States. Accordingly, it wishes to

participate as amicus curiae to address the issue raised by the

Defendants' motion to dismiss.

For the reasons set forth below, the United States submits

that there is no basis under the Voting Rights Act, its

legislative history, and the relevant case law for exempting the

election of judges from the prohibitions of Section 2.

1 Under Section 5, covered jurisdictions (which includes 40

counties in North Carolina) may not implement any change in a

voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard

practice or procedure with respect to voting, until the

jurisdiction obtains federal preclearance, either from the

Attorney General or the United States District Court for the

District of Columbia. McCain v. Lybrand, 465 U.S. 236, 244-255

(1984).

3

II. BACKGROUND

In fir h v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D. N.C. 1985) aff'd

54 U.S.L.W. 3840 (June 23, 1986) the State was enjoined, pending

federal preclearance under Section 5, frpm enforcing changes in

its method of electing Superior Court judges that resulted from a

series of acts of the North Carolina legislature that were

enacted between 1965 and 1983. The State subsequently submitted

those acts to the Attorney General for review under Section 5,

along with several acts affecting the election of District Court

judges that had not been precleared. On April 11, 1986, the

Attorney General notified the State that he did not object to the

changes involving District Court elections, and some of the

changes affecting the Superior Court. However, the Attorney

General objected to three Acts that changed the method of

electing Superior Court judges: Chapter 262 (1965) which

required candidates in multi-member districts to run for numbered

posts, and Chapters 997 (1967) and 1119 (1977) which created

multi-member judicial districts out of previously existing

single-member districts, and/or staggered the terms of the

Superior Court judges in Districts 3, 4, 8, 12, 18 and 20. As to

each of those Acts, the Attorney General was unable to conclude

that the State had met its burden under Section 5 of

demonstrating that they would not unlawfully abridge minority

voting rights.

On July 9, 1986, and in response to the Attorney General's

objections, the State legislature passed Chapter 957 which

4

eliminated the numbered post provision for Superior Court

elections. However, that Act did not purport to remedy the other

changes to which the Attorney General had objected. Instead, on

May 30, 1986, the State filed the above referenced declaratory

judgment action in which it seeks to prove that those changes

satisfy the substantive standard of Section 5. Trial of that

action is presently scheduled to commence on July 13, 1987.

On October 2, 1986, the Plaintiffs Kelly Alexander e_t al.,

filed their complaint in this case in which they seek to mount a

state-wide challenge to the method of electing Superior Court

judges. Plaintiff-intervenors were allowed intervention on

October 23, 1986.

III. THE DEFENDANTS' MOTION TO DISMISS

The Defendants have moved to dismiss the Plaintiffs' Section

2 claims and in support of their motion advance the following

principal arguments.

1. Only one court, Kirkspy v. Allain, No. J85-0960(B) (S.D.

Miss. 1986), has ever squarely held that judicial elections are

covered by Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

2. There is no evidence in the legislative history that

Congress ever intended that Section 2 cover the election of

judges:

3. Since the "one man-one vote" principle of Reynolds v.

Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) has been held not to apply to the

State's judiciary, see Holshouser v. Scott, 335 F. Supp. 928

(M.D. N.C. 1971), aff'd 409 U.S. 807 (1972), and that principle

5

was a basis for the, evolution of the vote dilution doctrine under

the Voting Rights Act, vote dilution claims affecting judges are,

by necessary implication, not cognizable under Section 2.

As we argue below, these contentions are without merit.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. The plain words of the Voting Rights Act, which courts

should construe broadly, state that, where judges are elected

voting discrimination is prohibited because the Act applies to

all elections for public office without exception, and there is

no evidence in the legislative history that Congress intended

otherwise.

2. There is ample case authority supporting this plain

reading of the statute, including Raith v. Martin, supra, a case

involving these same defendants where a three judge court found

that judicial elections are covered by Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act and rejected virtually the same arguments the

Defendants seek to-advance here under Section 2.

3. The "one man-one vote" principle, even if inapplicable

to the apportionment of judicial districts under the Fourteenth

Amendment, does not purport to address the legality of electoral

systems that discriminate against racial or ethnic groups. As

such, that principle is not a concern of the Voting Rights Act

which was passed to enforce the Constitutional guarantees of the

6

Fifteenth and Fourteenth Amendments against discrimination in

voting on the basis of race, color or membership in a language

minority group. 2

ARGUMENT

I. SECTION 2 SHOULD BE BROADLY CONSTRUED

The Voting Rights Act "reflects Congress firm intention to

rid the country of racial discrimination in voting." smith

Carolina v. Katzenback, 383 U.S. 301, 315 (1966). The Supreme

Court has emphasized conSistently that the Act should be broadly

construed to effectuate this important national goal. Ulan v.

State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969); Georgia v. United

States, 411 U.S. 526, 533 (1973) -; United States v. Board of

Commissioners of Sheffield, Alabama et al., 435 U.S. 110, 122-123

(1978). "It is apparent from the face of the Act, from its

legislative history, and from our cases that the Act itself was

broadly remedial in the sense that it was 'designed by Congress

to banish the blight of racial discrimination in voting...'

(citation omitted)," United Jewish Oraa_nizations of Williamsburg.

Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 156 (1977).

2 As originally passed by Congress in 1965, the Voting

Rights Act was intended to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment's

prohibition against discrimination in voting on the basis of race

or color. See, City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980). In

1975 the Act was amended, pursuant to Section 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment, to prohibit voting discrimination against language

minority groups. See, Unite States V. Uvaide Consolidated

Independent School District et al., 625 F.2d 547 (5th Cir. 1980),

cert denied, 451 U.S. 1002 (1981 et al.).

7

Section 2, which extends the prohibitions of the Act nation-

wide, is subject to no narrower interpretation. United States v.

Uyalde Consolidated Independent School District, supra, 625 F.2d

at 556. Indeed, when Congress amended the Voting Rights Act in

1982, it noted that "Section 2 remains the major statutory

prohibition of all voting rights discrimination" (Senate Report

No. 97-417, 97 Cong. 2nd Sess. p. 30); and the Supreme Court has

consistently supported its broad construction. See, Allen v.

State Board of Electiohs, supra, where the Court stated, based on

the legislative history, that Section 2 "was intended to be all

inclusive of any kind of [voting] practice" quoting remarks of

Attorney General Katzenbach during Senate hearings prior to the

1965 Act, 393 U.S. at 566-567. In sustaining the constitu-

tionality of the Act in South Carolina v. Katzenbach aupra, the

Court stressed that Section 2 is "aimed at voting discrimination

in any area of the county where it may occur. [It] broadly

prohibits the use of voting rules to abridge the exercise of the

franchise on racial grounds." 383 U.S. at 316.

II. JUDICIAL ELECTIONS ARE COVERED BY SECTION 2

As noted saarA, Section 2 was originally designed to enforce

the provisions of the Fifteenth Amendment. City of Mobile v.

Bo„lden, supra. Thus, it can hardly afford minority voters any

less protection of their rights than the Amendment itself. Yet

the Defendants contend that judicial elections, which are clearly

covered by the Fifteenth Amendment, are not covered by Section 2.

This position is untenable.

8

North carolina has chosen to extend the franchise to the

election of Superior Court judges. Having made that choice, it

is bound by the Voting Rights Act in the conduct of those

elections. Section 2 and Section 5 contain virtually identical

language governing methods of election that are covered by those

provisions i.e., they apply to any "voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting, or standard practice or procedure with

respect to voting." It is uncontroverted that judicial elections

are covered by this language in Section 5 (see, Haith v. Martin.

supra). There is thus no basis in the plain language of the

statute for concluding that such elections are not covered by

Section 2.

"Voting" is defined in Section .14(c)(1) of the Act, 42

U.S.C. 19731(c)(1) to include:

all action necessary to make a vote effective

in any primary, special, or general election,

including, but not limited to, registration,

listing pursuant to this (Act], or other action

required by law prerequisite to voting, casting

a ballot, and having such ballot counted properly

and included in the appropriate totals of votes

cast with respect to candidates for Public or

party office and propositions for which votes are

received in an election. [Emphasis added.]

That definition applies to all sections of the Act. Where judges

are elected rather than appointed, as is the case here, they are

"candidates for public...office," and it seems beyond any doubt

that the strictures of the Voting Rights Act apply. There is no

legislative history to the contrary.

9

For the most part, the Defendants' only reliance on the

legislative history is for its alleged silence with respect to

the judiciary. See, Memorandum in Support of Motion to Dismiss

pp. 3, 5,9. While the legislative history is not so silent with

respect to judges as the Defendants suggest (see part III infra),

even if it were, that silence would hardly support the creation

of an exception from a statute whose plain terms encompass all

elections for public office.

The Supreme Court rejected similar efforts to create

exceptions to the Voting Rights Act in United States v. Board of

Commissioners of Sheffield, Alabama et al., supra. In that case,

the City of Sheffield, Alabama argued that it was not subject to

the preclearance provisions of the Act because they extended only

to states and "political subdivisions." Section 14c(2) of the

Act defines a political subdivision as a county or parish, except

that where registration for voting is not conducted under the

supervision of a county or parish, the provisions extend to any

other subdivision of a state which conducts registration for

voting. The City argued that since it had never conducted voter

registration, it was not a political subdivision and thus not

covered by Section 5.

In reversing the ruling of a three judge court in favor of

the City on this issue, the Supreme Court held that, while there

was little legislative history on the "specific narrow question"

raised by the City, "there is little, if anything, in the

original legislative history that in any way supports the

10

crippling construction of the District Court." 435 U.S. at 130.

The most compelling evidence that such a construction was

contrary to Congresional intent was its inconsistency with the

underlying purposes of the Act. Said the Court:

There is abundant evidence that the District

Court's interpretation of the Act is contrary

to the congressional intent. First, and most

significantly, the District Court's construction

is inconsistent with the Act's structure, makes

S 5 coverage depend upon a factor completely

irrelevant to the Act's purposes, and thereby

permits precisely the kind of circumvention of

congressional policy that § 5 was designed to

prevent. Second, the language of the Act does

not require such a crippling interpretation,

but rather , is susceptible of a reading that

will fully implement the congressional objectives.

435 U.S. at 117.

Excluding the election of judges from the coverage of

Section 2 is unwarranted for the same reasons. See, United

States v. Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District, au2LA,

625 F.2d at 554-556. Moreover, in light of the Supreme Court's

affirmance in Haith v. Martin, supra, that judicial elections are

covered by Section 5, a contrary ruling in this case under

Section 2 would produce a curious anomaly. In such case,

judicial elections in states_ or counties not covered by the

federal preclearance provisions of Section 5 would not be subject

to the Voting Rights Act, while judicial elections in the Section

5 jurisdictions would be covered by the Act. Congress could

hardly have intended such a result. Indeed, such a distinction

between the states and their political subdivisions in their

obligations to comply with the Voting Rights Act without any

11

congressional findings to support it may be constitutionally

indefensible. See, South CarQlina V. Katzenbach supra, 383 U.S.

at 330-331, and City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 176-

178 (1980).

There are other contradictory results that would occur if

this Court were to hold that judicial elections are not covered

by Section 2. It is well established that the Attorney General's

administrative determinations under Section 5 are not subject to

judicial review. Seer Allen v. State Board of Elections supra,

393 U.S. at 549-550; drrris V. Gressette, 432 U.S. 491 (1977).

As a consequence, once a jurisdiction receives preclearance under

Section 5 to implement a voting change, citizens who may

nevertheless claim to be aggrieved by the change have no further

remedy under Section 5. In such a circumstance, the Act

contemplates that they would be able to pursue their claims

through private actions under Section 2. Allen v. State Board of

Elections supra; Morris v. Gressette supra. That opportunity

would be foreclosed if judicial elections were .not covered by

Section 2.

Such a ruling would also foreclose the Attorney General from

suing under Section 2 to enjoin a previously precleared change in

judicial elections if it became evident, after the close of the

administrative review period, that the change was discriminatory.

That result is also contrary to the enforcement scheme

contemplated by the Act. See the Attorney General's Procedures

for the Administration of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of

12

1965, 28 C.F.R. Part 51 ("Section 5 preclearance will not

immunize any change from later challenge by the United States

under amended Section 2," 52 Fed. Reg. 487).

Indeed, under the Defendants' theory, the Attorney General

could not bring any lawsuits under Section 2 to enjoin even the

most egregious voting rights violations where the election of

judges is concerned. Thus the United States could not sue under

Section 2 to enjoin such flagrant voting rights abuses as

occurred in 5ell v. Southwell, 376 F.2d 659 (5th Cir. 1967) where

the Court found that a Georgia election for Justice of the Peace

"was conducted under procedures involving racial discrimination

which was gross, state-imposed and forcibly state-compelled." 3

Plainly, Congress could not have intended such a derisive result

in enacting the Voting Rights Act.

III. THERE IS NO EVIDENCE IN THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY THAT

CONGRESS INTENDED TO EXCLUDE THE ELECTION OF JUDGES FROM

THE COVERAGE OF SECTION 2

Even if it were not clear from the plain language of the Act

that judicial elections are covered by Section 2, thus requiring

resort to the legislative history, that history does not support

the Defendants contention that Congress intended to exempt the

election of judges from the proscriptions of Section 2.

The legislative history of the Act at the time it was

passed originally by Congress in 1965 shows some discussion of

3 The discriminatory practices included racially segregated

voting lists and voting booths, and physical assaults on black

voters.

13

whether the term "vote" that was contained in the operational

definitions of the House and Senate bills (H.R. 6400 and S.1564)

should include the election of candidates for offices of

political parties. See, Conference Report S. 1564, 89th Cong.

1st Sess. Report No. 711, P.14. The House bill extended the Act

to party elections, the Senate bill did not. Congress agreed to

include party elections in the final version of the Act. See, 42

U.S.C. § 19731(c)(1). Had there been any perception on the part

of members of either the House or Senate that judicial elections

should be exempted from the Act, they could have expressed those

views at the times these provisions were deliberated. They did

not.

In his enforcement of the Act, the Attorney General has

treated judicial elections as subject to the Act, and has so

informed Congress. For example, on December 26, 1972 the

Attorney General objected under Section 5 to an Alabama change

from elected to appointed justices of the peace. This objection

was brought to the attention of Congress when the Voting Rights

Act extension of 1975 was under consideration. 4 On February 20,

1976, the Attorney General objected to an Alabama statute that

combined two counties in a judicial district. This objection was

brought to the attention of Congress when the Voting Rights Act

4 See Extension of the Voting Rights Act: H.R. 939, H.R.

2148, H.R. 3247, and H.R. 3501 Before the Subcomm. on Civil and

Constitutional Rights of the House Comm. on the Judiciary, 94th

Cong., 1st Sess. Pt. 1, at 183 (1975) (Exhibit 5 to testimony of

J. Stanley Pottinger, Assistant Attorney General, Civil Rights

Division).

14

Extension of 1982 was under consideration. 5 On February 7,

1980, the Attorney General objected to a Louisiana statute and a

Baton Rouge ordinance requiring certain judges to be elected at

large by a majority vote. Congress was so advised. 6

Finally, there is evidence in the legislative history of the

1982 amendments to the Act that Congress understood that Section

2 applies to judicial elections. Senator Orrin Hatch, Chairman

of the Senate Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on the

Constitution, commented on the broad application of Section 2 and

stated specifically that it applied to judicial districts.

For the past seventeen years, Section 2 has stood as a

basic and non-controversial provision to ensure that any

discriminatory voting law or procedure could be

successfully challenged and voided . .

• • •

It is important to emphasize at the outset that for

purposes of Section 2, the term "political subdivision"

encompasses all governmental units, including city and

county councils, school boards, ludicial districts, utility

districts, as well as state legislatures. [Emphasis

supplied]

S. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 127, 151 (1982).

5 Extension of the Voting Rights Act: Hearings Before the

Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the House Comm. on

the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. Pt. 3, at 2247 (1982)

[hereinafter cited as 1982 Hearings] (Attachment 6 to Letter from

James P. Turner, Acting Assistant Attorney General, Civil Rights

Division, to Rep. Don. Edwards).

6 1982 Hearings 2260.

15

IV. SECTION 2 PROHIBITS VOTING PRACTICES IN JUDICIAL

ELECTIONS THAT RESULT IN THE DENIAL OR ABRIDGMENT

OF MINORITY VOTING RIGHTS

While the Defendants broadly assert that Section 2 does not

apply at all to the election of judges (see Memorandum In Support

of Motion To Dismiss p. 2), 7 a substantial portion of their brief

is devoted to the argument that claims of racial vote dilution in

the election of judges (as distinguished from other racially

discriminatory voting practices) are not covered by Section 2

because the "one-man one-vote" apportionment principle has been

held not to apply to judicial elections. The Defendants rely

principally on Folshouser v. Scott, auaLA, and Wells v. Edwards,

347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972) aff'd, 409 U.S. 1095 (1973) in

support of this ar,gument.

As we show below, these cases are distinguishable, and other

courts have refused to interpret them as foreclosing challenges

to judicial electoral systems that discriminatorily dilute the

voting strength of racial groups.

7 The Defendants also appear to make the startling

suggestion (see memorandum p. 19) that there is no need for

protecting minority voting rights in judicial elections because:

there is no need for any segment of society to be

represented on the bench in order to insure that its

voices will be heard. The only voices a judge may

here are those of the litigants and their attorneys

as they appear in court to argue the facts and meaning

of the law. It is the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, not § 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which assures

that minorities will not be shut out of fair consideration

by the court.

16

We note initially that, as a general proposition, vote

dilution claims, as they affect racial or ethnic groups, are

cognizable under both Section 5 and Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act. See, aliaa v. State Board of Elections, supra, 393

U.S. at 564-567; Georgia v. United States, supr, 411 U.S. at

531-532; Thornburc v. Gingles, 478 U.S. , 106 S. Ct. 2752

(1986); United States v. Uvalde CongOlidated Independent School

*District, supra, 625 F.2d at 553. In aith v. Martin, supra, the

Court rejected the defendants argument that Section 5 does not

cover claims of vote dilution in .judicial elections. The Court

found that the Defendants reliance on the "one-man one-vote"

principle, as applied in Holphouper, was misplaced because in

deciding that case the Court "in no way dealt with, or attempted

to interpret, the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In fact, neither

the majority nor the dissent mentioned the Voting Rights 'Act of

1965." 618 F. Supp. at 412-413.

The Court also rejected the argument, which the Defendants

seek to resurrect here, that because judges are not

"representatives" (their function being to administer the law and

not espouse the cause of a particular constituency) judicial

electoral systems that dilute.minority voting strength cannot be

challenged under the Voting Rights Act because population balance

is not a relevant consideration in those elections. The court's

17

reason, based on the plain language of the Act, for rejecting

that argument under Section 5 is equally instructive as a basis

for rejecting it here under Section 2. Said the Court:

Defendants seek to draw on the distinction made

in Folshouser between those in the legislative

branch of government who represent their constituents

in the making of laws and those in the judicial

branch who do not represent a constituency but, rather,

interpret the law. Discounting the interesting

jurisprudential arguments arising from such an

attempted distinction, see, Folshouser, 335 F. Supp.

at 934 (Craven, J. dissenting), it is quite clear that

no such distinction can be attributed to the [Voting

Rights] Act. The Act provides:

No voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting, or standard, practice, or

procedure shall be imposed or applied

by any State or political subdivision

to deny or abridge the right of any

citizen of the United States to vote

on account of race or color... .42 U.S.C.

§ 1973.

As can be seen, the Act applies to all voting

without any limitation as to who, or what, is the

object of the vote. 618 F. Supp. at 413.

Thus, the Defendants' efforts to convince the Supreme Court of

the merits of these arguments already have been unavailing. 8

The decision in Faith was followed in Kirksey v. Allain, 635

F. Supp. 347 (S.D. Miss. 1986). That case involved a state-wide

challenge to the method of electing chancery and circuit court

judges in Mississippi. The suit was brought under both Sections

2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act as well as the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments. The plaintiffs' Section 5 claims involved

8 See pp. 7-11 of the Defendants' Jurisdictional Statement

before the Supreme Court in aaith V. Martin, a copy of which is

attached to this memorandum.

18

certain changes to the judicial election system that had not been

submitted for preclearance. In granting the Plaintiffs' motion

for a preliminary injunction on the Section 5 issue, the Court

refused the defendants' invitation that it reject the holding of

Faith v. Martin and exempt judicial elections from the scope of

S 5. 9 The Court instead followed buith and held that judicial

elections should not be exempt from the Act because it "applies

to all voting without any limitation as to who, or what, is the

object of the vote." 635 F. Supp. at 349.

The Court later denied the Defendants' motion to dismiss the

Section 2 claims for the same reasons. See Order of June 2, 1986

(copy attached). In denying that motion the Court relied on the

Fifth Circuit's decision in Voter Information Pro -iect, Inc. v.

City of Baton Rouge, 612 F2d 208, 212 (5th Cir. 1980) where the

court of appeals held it was reversible error for the District

Court to have dismissed for failure to state a claim the

Plaintiffs' constitutional challenge to the at-large method of

electing city judges in Baton Rouge and state court judges in

Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana. The District Court had based its

dismissal of those claims on the "one-man one-vote" principle

reasoning, as the Defendants urge here, that since that principle

does not apply to the election of judges, the Plaintiffs could

9 The Defendants in that case raised essentially the same

arguments the Defendants advance here viz, the Act only applies

to "representatives" and judges do not fall into that category;

and vote dilution has ao meaning in judicial elections because

the "one-man one-vote" principle does not apply to those

elections.

19

not claim that this method of election unlawfully diluted

minority voting strength. In reversing that ruling, the Fifth

Circuit, as did the courts in aaith and Kirksey, distinguished

Holshouser v. Scott, supra, and the other "one-man one-vote"

cases affecting judicial apportionments.

The Fifth Circuit stressed that none of those cases involved

claims of race discrimination, and pointed out that the court in

Eolshouser made clear in its opinion that there had been no

showing of "discrimination" or "invidious" state action. The

Fifth Circuit then concluded that:

To hold that a system 6esigned-to

dilute the voting strength of black

citizens and prevent the election of

blacks as judges is immune from attack

would be to ignore both the language and

purpose of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments. The Supreme Court has

frequently recognized that election schemes

not otherwise subject to attack may be

unconstitutional when designed and

operated to discriminate against racial

minorities ... (citing White v. Register

412 U.S. 755 (1972) and omillion v.

Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960). 612 F.2d at 211

The Supreme Court consistently has distinguished between the

equal protection principles that apply to apportionments under

the "one-man one-vote" doctrine, and electoral systems that

discriminate on the basis of race. In White v. Register, supra,

the Court reversed the district court's determination that a 1970

reapportionment plan for the Texas House of Representatives

violated the one-man one-vote principle of Reynolds v. Sims

5212L1, but it sustained the lower court's finding that multi-

20

member districts in Dallas and Bexar Counties unlawfully diluted

the voting strength of blacks and Hispanics. See also, Whitcomb

v. Chavls, 403 U.S. 124, 142-143 (1971); Davis et al., v.

Bandemer et al., U.S. (1986) 54 U.S.L. W. 4898, 4901; and

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735, 751 (1973) ("A districting

plan may create multi-member districts perfectly acceptable under

equal population standards, but invidiously discriminatory

because they are employed 'to minimize or cancel out the voting

strength of racial or political elements of the voting

population' • (citations omitted))."

In sum, there is no basis under either the Voting Rights Act

or the United States Constitution for exempting altogether the

election of judges from Section 2's prohibition against

discrimination in voting simply because equal population

standards may not apply to the apportionment of judicial

districts. Rather, to the extent that the "nonrepresentational"

role of judges is of relevance, it relates not at all to the

threshold coverage question presented here, but to the

evidentiary evaluation of the voting procedure itself under the

various factors identified by Congress as pertinent to a

"totality of circumstances" analysis. 10

10 For example, the factor of "responsiveness" to minority

voters carries considerable weight under Section 2 in the context

of elective representation. But, it may well be of little or no

significance in the evidentiary balance at work under Section 2

in •reviewing a discriminatory change implicating the election

procedures for State judges. That does not mean elected judges

are exempt from Section 2 review, only that the review criteria

may well be weighted differently.

•

21

CONCLUSION

Based on the foregoing, the United States submits that

judicial elections are covered by Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act, and that a dismissal of the Plaintiffs' Section 2 claims

under F.R.C.P. 12b(1) or 12b(6) is not warranted.

Respectfully submitted, this 96%-day of March 1987.

SAMUEL T. CURRIN WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

United States Attorney Assistant Attorney General

GERALD W. JO S

PAUL F. HANCOCK

RICHARD J. RITTER

Attorneys, Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

10th & Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 272-6300

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this'- day of March 1987, I served

a copy of the foregoing Brief for the United States As Amicus

Curiae on all counsel of record by mailing, postage prepaid, a

copy to the following persons:

Lacy Thornburg

James Wallace, Jr.

Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General

P. 0. Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

C. Allen Foster

Robert G. McIver

Foster, Conner, Robson & Gumbiner

104 North Elm Street

P. O. Drawer 20004

Greensboro, North Carolina 27420

Leslie J. Winner

Ferguson, Stein, Watt, Wallas &

Adkins

Suite 730, East Independence Plaza

951 South Independenence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Angus Thompson

Attorney at Law

122 West Elizebethtown Road

Lumberton, North Carolina 28358

RICHARD J. RE2TER

Attorney, Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

10th & Constitution Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 272-6300