Laurel v. United States of America Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 5, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Laurel v. United States of America Brief Amicus Curiae, 1974. 2bc7f004-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d7bce70e-ebe8-46e5-9a14-70399f674490/laurel-v-united-states-of-america-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

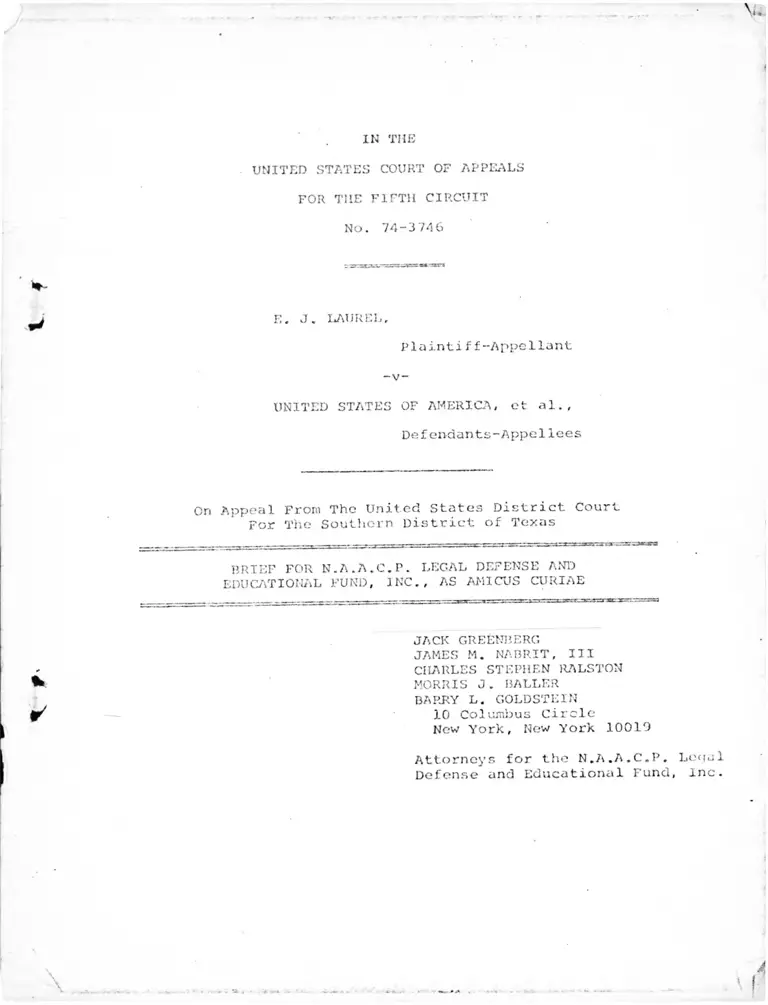

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 74-3746

E. J. LAUREL,

Plaintiff-Appellant

- v-

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.f

Defendants-Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District of Texas

BRIEF FOR N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC,, AS AMICUS CURIAE

JACK GREENBERG JAMES M. NABRIT, III CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

* MORRIS J. HALLER

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN— 10 Columbus CircleNew York, New York 10010

Attorneys for the N.A.A.C.P,

Defense and Educational Fund,

Lecju 1

Inc.

TABLE Or CONTENTS P age

Table of Contents......................................i

Table of Authorities.................... .......... ^

Interest of Amicus Curiae........................ 1

Introduction..................................... 3

ARGUMENT

I. §717 OF TITLE VII, ON ITS FACE, REQUIRES A TRIAL DE NOVO IN CIVIL ACTIONS BROUGHT

PURSUANT TO ITS PROVISIONS............. 7

II. §717 OF TITLE VII, AS A MATTER OFLEGISLATIVE HISTORY, REQUIRES A TRIAL

DE NOVO IN CIVIL ACTIONS BROUGHT

PURSUANT TO ITS PROVISIONS............. 15

Dissatisfaction With Administrative Remedies..... 15

Intent To Accord Federal Employees The Same

Enforcement Rights As Private Employees....... 28

III. THE STATUTORY PURPOSE OF §717 REQUIRES

A TRIAL DE NOVO IN WHICH LITTLE WEIGHT SHOULD BE GIVEN THE RECORD DEVELOPED DURING THE CSC DISCRIMINATION COMPLAINT

PROCESS................................ 33

Judicial Precedent and §717 Statutory Purpose.... 33

Part 713 Regulations On Their Face............... 39

Administration Of The Regulations................ 42

IV. PERSUASIVE CASELAW SUPPORTS THE REQUIRE

MENT OF A TRIAL DE NOVO IN FEDERAL

EMPLOYMENT CASES BROUGHT UNDER TITLE

VII................................... 54

V. THE RIGHT TO A TRIAL DE NOVO IS NOT WAIVED

WHEN THE EMPLOYEE ELECTS TO HAVE A FINAL

AGENCY DECISION WITHOUT UNDERGOING AN ADMINISTRATIVE HEARING, AS SPECIFICALLY

PROVIDED BY §717 (c).................... 59

CONCLUSION....................................... 63

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Aetna Ins. Co. v. Kennedy, 301 U.S. 389 (1937)

Alexander v. Gnrdner-Denver Co., 39 L.Ed.2d

147 (1974).............................

Beverly v. Lone Star Lead Const. Corp., 437

F.2d 1136 (5th Cir. 1971)..................

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954)...........

Bowers v. Campbell, 8 EPD 51̂ 5̂2 (9th Cir. 1974)...

Calder v.Bull, 3 Dali. 386 (1789)............... .

Carreathcrs v. Alexander, 7 EPD f9379 (D. Colo.

(1974).....................................

Congress of Racial Equality v. Commissioners,

270 F.Supp. 537 (D. Md. 1967).........

Engle v. Davenport, 271 U.S. 33 (1925)

Fekete v. United States Steel Corp., 424 F.2d

331 (3rd Cir. 1970)...................

Flowers v. Local 6, Laborers International Union

of North America, 431 F.2d 205 (7th

Cir. 1970)...............................

PAGE

61

4, 34,40,48,55,59,60

2,12,28,29

7

55

14

55

10, 11

13

12.28.29

12.28.29

Griffin v. U.S. Postal Service, 7 EPD [̂9133

(M.D. Fla. 1973).................... 54,55, 57

Cases

I

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)..... 549

Gnotta v. United States, 415 F.2d 1271 (8th Cir. 1969) cert, denied 397 U.S. 934

(1970)..................................... 10*11

Guilday v. U.S. Justice Dept, 43 LW 2195 (D. Del.

October 22, 1974).......................... 56,58

Hackley v. Johnson, 360 F.Supp. 1247 (D.D.C.

1973).................................... 31

Harris v. Nixon, 325 F.Supp. 28 (D. Colo.

1971)..................................... 10

Hassett v. Welch, 303 U.S. 303 (1933)..... ...... 13

Hodges v. Easton, 106 U.S. 408 (1882)........... 61

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948)............... 7

Interstate Consol. Street R. Co. v. Massachusetts,

207 U.S. 79 (1907)......................... 13

Jackson v. U.S. Civil Service Comm'n., 7 EPD^9134 (S.D. Tex. 1973).................... 5456,->7

Jenkins v. United Gas Corporation, 400 F.2d 28

(5th Cir. 1968)......................... 2 * 5

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122

(5th Cir. 1969)...............•.......... 2

Johnson v. U.S. Postat Service, 497 F.2d 12

(5th Cir. 1974)........................... 54

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES [Cont'd.]

Page

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTSfConi'd. 1

I jPago

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938)........... 61

Kendall v. United States, 12 Pet. 524, (1838).... 13

King v. Georgia Power Co., (259 F.Supp.

943 (N.D. Ga. 1968)............'-- '........ 13

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792 (1973)................................. 2, 4, 12,34, 50,55,59,60

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d

534 n. 14 (5th Cir. 1970).................... 1

Morrow v. Crisler, 470 F.2d 960 (5th Cir. 1973)

aff'd en banc, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.

1974)....................................... 5

Morton v. Mancari, 41 L.Ed.2d 290 (1974)........... 15, 17, 37,56

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S.

400 (1968).................................. 4,

Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1968)............................. 53

Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public Utilities

Comm. 301 U.S. 292 (1937).................. 61

Reynolds v. Wise, 375 F.Supp. 145 (N.D.Tex. 1974)................................. 54, 5j,57

Robinson v. Klassen, No. LR-73-C-301 (E.D.

Ark. October 3, 1974)...................... 56

^ 'O•

TABLE OF CONTENTS [Cont'd.]

Paqe

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971) cert, dismissed 404 U S 1006 (1971).... 1? 20, 29

Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp.. 400 U 9 542 (1971)........ 2

Smith v. Universal Services, Inc., 454 f 2d 154 (5th Cir. 1972).... 12,28,29,34

United States v. H.K. Porter Company, N.D. Ala. 1968, 226 F.Supp. 40.... 13

United States v. Standard Brewery 251 U.S. 210 (1920)....... 14

United States v. Tappan, 11 Wheat. 419 (1826) 10

Wisconsin Central R.co. v. United States 164 U.S. 190 (1896)..... 9

v

STATUTES

^ N>- lJ

Paqe

5 U.S.C. §702 .............................. 11

5 U.S.C. §706.............................. 11,56

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5......................... 9, 10,12,13, 15,28,29,

31, 59

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16....................... passim

EXECUTIVE ORDERS

E.O. 11246............................... 7,10

E.O. 11375............................... 7,10

E.O. 11478..................... .......... 7,10

REGULATIONS

5 C.F.R. §713.213........................ 39

5 C.F.R. §713.215........................ 39

5 C.F.R. §713.216........................ 40

5 C.F.R. §713.217........................ 40

5 C.F.R. §713.218........................ 40,41

5 C.F.R. §713.221........................ 41

5 C.F.R. §713.283........................ 41

VI

r

OTHER AUTHORITIES

M. Brewer, Behind the Promises: Equal EmploymentOpportunity in the Federal Government (Public

Interest Research Group 1972)...............

Brief for Appellees, Hackley v. Johnson,No. 73-2072 (D.C. Cir. 1974)................

Conference Rep. No. 92-681, on H.R. 1746,92nd Cong., 2d Sess. (1971).................

119 Cong. Rec. §1219........................

Hearings on H.R. 1746 Before the General Subcomm.on Labor of the House Comm, on Education and

Labor, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971)..........

Hearings on H.R. 13517 Before the General Subcomm. on Labor of the House Comm, on Education and Labor 91st Cong., 1st.

& 2d. Sess (1970).....................

Hearings on S.2453, Before the Subco.im. on Labor of the Senate Comm, on Labor and Public

Welfare, 91st. Cong., 1st Sess. (1969)---

Hearings on S.2515, S.2617 & H.R. 1746 Beforethe Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm,

on Labor and Public Welfare, 92d Cong.,

1st. Sess. (1971)........................

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, on H.R. 1746, 92d

Cong., 1st Sess (1971)...................

Page

42,43,52

62

29

29

21,23,26,

27, 32

16,21,22,25,

27,32

16,17,31

21,22,26,27,32

17,22,28,35,

37,43,51

I. Kator, Third Generation Equal Employment Opportunity, Civil Service Journal

(July-Scptember 1972)...............

Letter from Robert E. Hampton, Chairman, CSC, by Arthur F. Sampson. Acting Administrator, GSA, of June 18, 1973.

Note, Racial Discrimination in the Federal

Civil Service 38 Geo. Wash. L. Rev.

265 (1969)......................... .

vii

OTHER AUTHORITIES [Cont'd.]

Sape & Hart, Title VTI Reconsidered: The Equal Opportunity Act of 1972, 40 Geo. Wash.

L. Rev. 824 (1972).......................... 11

Senate Rep. No. 92-415, On S. 2515, 92d Cong.,1st Sess. (1971)............................ 8,19,22,24,28,35,38,51

Staff of Subcomm. On Labor of the Senate Comm.on Labor and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 2d Sess., Legialative History of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972(Comm. Print 1972))Legislative Hisotyr].... passim

U.S. Civil Service Conn'n. BAR Annual Report ot the Commissioners for FY 1974,

/Attachment 2............................... 44

U.S. Civil Service Conn'n. Discrimination Complaint Examiner's Handbook (April1972)............................... ..... 42,44,46,48,49, 50

U.S. Civil Service Conn'n. DiscriminationComplaint Procedures................. 81

U.S. Civil Service Conn'n., FPM Letter

No. 713-17, Attachment 1.................. 39

U.S. Civil Service Conn'n., InvestigatingComplaints of Discrimination in Federal

Employment (Rev. October 1971)........... 42,45,46,48

U.S. Civil Service Comm'n., Matter of Jones(BAR decision of October 4, 1974).......... 50

U.S. Civil Service Comm'n., Memorandum on Government Equal Employment Opportunity Counseling

and Discrimination Complaint Activity, Fiscal

Year 1972 thru Fiscal Year 1974

(August 20, 1974)......................... 43

U.S. Civil Service Comm’n., Memorandum on Precomplaint Counseling and Discrimination Com

plaint Activity During Fiscal Year 1974

(August 20, 1974)....................... . 43

Page

viii

OTHER AUTHORITIES [Cont'd.]

Page;

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The FederalCivil Rights Enforcement Effort -

A Reassessment (1970)...................... 40

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Federal Civil Rights Enforcement Effort -

A Reassessment (1973)...................... 8,47

ix

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-3746

E. J. LAUREL,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

—v-

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,' et al . ,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court For The Southern District of Texas

BRIEF FOR N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE*

Interest of Amicus Curiae

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

has for many years been engaged in civil rights litigation

in this Court and in district courts throughout the Fifth

Circuit. See Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426

F.2d 534, 539, n.14 (5th Cir. 1970). Following the enactment

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,attorneys

associated with the Legal Defense Fund have participated in

^Counsel for both parties have consented to the filing

of this Brief, pursuant to F.R.A.P., Rule 29.

many of the leading cases decided by this Court and the

Supreme Court that have resulted in Title VII being given

a broad and expansive interpretation, both procedurally and

substantively, so that the Act could accomplish the goal of

Congress and serve as an effective weapon against employment

discrimination. See, e.g., Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

417 F.2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969); Jenkins v. United Gas Corp

oration, 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968); Beverly v. Lone Star

Lead Const. Corp., 437 F.2d 1136 (5th Cir. 1971); Phillips

y. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971); McDonnell

Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973).

When the 1972 amendments to Title VII that made the

federal government subject to the Act's provisions were enacted,

the Legal Defense Fund and cooperating attorneys became in

volved in cases against the federal government nationwide.

In this Circuit alone the Fund has litigation pending in dis

trict courts in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and Texas. Agencies

being sued include, inter alia, the Army, Navy, and Air Force,

the Post Office, and the National Aeronautic and Space Administration

In every one of our cases, and, we believe, in every cosc

brought against it nationwide, the government has consistently

raised technical and narrow objections whose purpose is so to

restrict the scope of the case as to make it impossible for the

federal courts to review government employment policies and to

grant the kind of relief the United States itself has con-

-2

r

sistently maintained should be afforded against private and

state and local government employers. This case involves only

one of the government's arguments — that a government employee

is not entitled to a trial de novo in a Title VII action. The

Court should be aware, however, of this contention s re

lationship to the other principle argument consistently made

by the government — that federal employees cannot maintain

a class actiai under Title VII.

The result of the acceptance by the federal courts of

these contentions would be to reduce the federal courts to a

rubber stamp; their role would merely be to review an ad

ministrative "record" compiled by agents of the defendant

agency concerning what happened to a single employee. No broad

independent inquiry into or assessment of the challenged

employment practices would ever be conducted. The government,

the largest single employer in the nation, would be immune from

the same judicial scrutiny to which all other employers are

subject. For the reasons set out below, amicus curiae con

tends that such a result would be unwarranted and unjust.

The grant of summary judgment should be reversed, and plaintiff

should be permitted to go forward and litigate his claim

of discrimination on the merits.

Introduction

The kind of hearing the federal courts provide employment

discrimination complaints is what principally determines the

quality of judicial enforcement of Title VII, a "policy Con-

-3-

Newman v. Piggiegress considered of the highest priority."

Park Enterprises. 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968) cited in Alexander v.

Gardner-Donvor Co., 39 L.Ed.2d 147, 158 (1974). The question

has been resolved in favor of trial de novo in private and state

or local government employment discrimination litigation in a

variety of contexts; the same reasons require a similar resolu

tion in federal employment discrimination litigation. The

Supreme Court in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792,

799 (1973), stated that “court actions under Title VII are de_

novo proceedings" notwithstanding that the EEOC had rendered a

finding of a no reasonable cause. Similarly in Alexander v.

Gardner-Denver Co., supra, the Court held that a trial do novo

is not foreclosed by a prior arbitral decision of no reasonable

cause. The common thread of Title VII law is that it is imper

missible "to engraft on the statute a requirement which may in

hibit the review of claims of employment discrimination."

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, supra, 411 U.S. at 798-99.

"[C]ourts should ever be mindful that Congress, in en

acting Title VII, thought it necessary to provide a judicial

forum for the ultimate resolution of discriminatory employment

claims. It is the duty of courts to assure the full availability

of this forum." Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., supra, 39 L.Ed.2d

at 165 no.21. Employment discrimination prohibited by Title VII

quite clearly raises different issues than ordinary federal

employee adverse actions, issues the federal courts are best

suited to decide. "The objective of Congress in the enactment

of Title VII . • • was to achieve equality of employment oppor

tunities and remove barriers that have operated in the past to

favor an identifiable group of white employees over other

employees." Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 429-30

(1971). In short, federal employees are entitled to no more and

no less than what employees of a private company, see, e_._cj. <

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122 (5 th Cir^ 1969),

or a state or local governmental entity, see, e.g., Morrow v.

Crisler, 479 F.2d 960 (5th Cir. 1973), aff'd on banc, 491 F.2d

1053 (5th Cir. 1974), are entitled to under Title VII and the

Constitution.

In Part I we show that the statutory language of §717 of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, added by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, 42 U.S.C. §2000 (e) -16(a),

unquestionably requires a trial de novo of claims of racial dis

crimination in federal employment. Because the face of the

statute is unequivocal, canons of statutory construction dictate

that statutory analysis alone settles the question. Nevertheless

in Part II we show that legislative history, without contradition

also makes clear what the statute in fact says, that a trial

de. novo is required. The question of what standard of scrutiny

the federal district courts may use in adjudicating federal

employ non t discrimination was settled by Congress in 1972 . We

demonstrate in Part III, however, that present CSC procedures

federal employment discrimination complaints infor processing

light of the statutory purpose to eliminate racial discrimi

nation from federal employment also dictate a trial dja novo.

Persuasive caselaw, as set forth in Part IV, is in agreement

with this reading of the statute. It follows, as we show in

Part V, that federal employees do not waive their right to a

plenary judicial trial on the merits by electing an agency

decision without an administrative hearing.

-6-

r

A R G U M K N T

I .

6 717 OF TITLE VII, ON ITS FACE, REQUIRES

1 TRIALDE NOVO IN CIVIL ACTIONS BROUGHT

PURSUANT TO ITS PROVISIONS.

The declaration of purpose and policy in S 717<n' that'

"All personnel actions affecting employees or applicants . . .

in executive agencies . . . be made free from any discrimination

based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin" merely

reiterates prior declarations in E.o. 11246, § 101 of September

24, 1965, E.O. 11375. § 101 of October 13, 1967 and E.O. 1147S

§ 1 of August 8, 1967. It has of course been the law since

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948) and Bolling v. Sharpe, 347

civil rights legislation and

U.S. 497 (1954) that/the Fifth Amendment due process

clause prohibit any racial discrimination by the

federal government. Moreover, § 717(b) that spells out the

remedial, affirmative action and review‘responsibilities of

federal agencies, is similar to obligations imposed by successively

more detailed Executive Orders. Compare § 717(b) with E.O.

11478 §<$ 2 — 5. The derivative character of the non-discrimination

rights guaranteed to federal employees is indicated by § 717(e)

which states that, "Nothing contained in the Act shall relieve

any Government agency or official of its or his primary

responsibility to assure non-discrimination in employment as

required by the Constitution and statutes or of its or his

responsibilities under Executive Order 11478 relating to equal

employment opportunities in the Federal Government."

The manifestly new element in § 717 is the express

remedial provision that an aggrieved federal employee may "file

a civil action" naming the head of his agency as defendant without

1/

1 / The Senate report states, "The bill adds to Title VII a new

Section 717 (Section 11 of the bill) making clear the obligation of the Federal Government to make all personnel decisions free

from discrimination based on race, color, sex, religion or national

origin." (emphasis added) Senate Rep. No. 92-415, on S.2515,

92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 12 (1971); Staff of Subcomm. on Laborof the Senate Comm, on Labor and Public Welfare, 92d Cong.,2d Sess., Legislative History of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972 at 921 (Comm. Print 1971) [Legislative History] .

See also. Legislative History at 1723 (Comment of Sen. Cranston

that "these [717] provisions . . .in many respects only codify

requirements presently contained in Executive Oiders and the

Constitution") 1968 (Comment of Sen. Williams).

The u . S. Commission on Civil Rights, charged with the

legal duty of monitoring federal civil rights enforcement,

is of the same opinion.

The new law clearly strengthens the

position of CSC in terms of its relationship to other Federal departments and agencies.However, what it provides, with few exceptions, is nothing but an affirmation of power CSC already possessed under the previous Executive Orders 8/ — powers which CSC heretofore chose

to exercise in a limited manner.

8/ Actions CSC has recently taken— such as changing the requirements for affirmative action plans and developing procedures under

which it can assume responsibility for a

grievance filed wi th an agency' are congruent with the authority CSC had under

Executive Order 11478. U-S. Comm, on Civil Rights, The Federal Civil Rights Enforcement

Effort - A Reassessment 45 (1973)

-8-

completely exhausting available administrative remedies.

§§ 717(c) and 717(d) provides that:

(c) Within thirty days of receipt of notice of final action taken by a department,

agency, or unit referred to in subsection 717(a) or by the Civil Service Commission

upon an appeal from a decision or order of

such department, agency, or unit on a complaint

of discrimination based on race, color,

religion, sex or national origin, brought pursuant to subsection (a) of this section,

Executive Order 11478 or any succeeding Executive orders, or after one hundred and

eighty days from the filing of the initial charge with the department, agency, or unit

or with the Civil Service Commission on appeal from a decision or order of such department,

agency, or unit, an employee or applicant for

employment, if aggrieved by the final disposition of his complaint, or by the failure

to take final action on his'complaint, may file

a civil action as provided in section 706, in

which civil action the head of the department,

agency, agency, or unit, as'appropriate, shall

be the defendant.

(d) The provisions of section 706(f)

through (k) as applicable, shall govern civil actions brought hereunder. 2/

2/ The phrase "as applicable" merely refers to those sections

dealing with the EEOC and the Attorney General in § 706(f) - (k)

which are obviously inapplicable to civil actions against the

federal government. This intent .is clear from the Section-By-

Section Analysis of H. R. 1746, The Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 explaining the major provisions of the 1972 Act, as

reported from the Conference Committee which states that, "The provisions of Sections 706(f) through (k), concerning private civil actions by aggrieved persons, are made applicable to aggrieved

Federal employees or applicants for employment." Legislative

History at 1851. Moreover, construction of a statute rendering meaningless a reference to another statute is not favored, "the

explicit language of the statute cannot thus be done away with."

Wisconsin Central R. Co. v. United States, 164 U.S. 190, 202

(1896).

None of the Executive Orders had expressly conferred such a

right of action or specifically waived the sovereign immunity

of the federal government, see, E.O. 1146, § 104; E.O. 11375,

§ 104; E.O. 11478, § 4. The courts had been reluctant to imply

access to the courts, see, e.g., Gnotta v. United States, 415

F .2d 1271, 1277-78 (8th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 934

(1970); Congress of Racial Equality v. Commissioners, 270 F. Supp.

537, 542 (D. Md. 1967), or permitted only limited review of the

administrative record, see, e.g., Harris v. Nixon, 325 F. Supp.

28 (D. Colo. 1971). §§ 717(c) and 717(d) redressed the prior depr

vation of any or very limited judicial review of agency disposition

of complaints of employment discrimination, by their terms giving

federal employees the same remedial protection as private and

state or local government employees enjoy under provisions of

§ 706. It should be clear that narrow construction of judicial

scrutiny, reducing the federal courts to the role of rubber

stamp for agency dispositions of complaints of employment

discrimination, would nullify the only substantive change in

the law effected by § 717. Hie long standing rule of con

struction is that courts may not construe a statute in such a

way that its provisions are rendered nugatory. See, e.g.,

United States v. Tappan, 11 Wheat. 419, 426 (1826).

A trial do novo is also required by express terms of the

statute. First, § 717(c) provides that an aggrieved employee

••may file a civil action as provided in section 706" (emphasis

added) and § 717(d) states that, "The provisions of section

706(f) through (k) , as applicable, shall govern civi J. _'l c! -3

brought hereunder" (emphasis added). §§ 706(f) - (k), specifically

-10-

incorporated by §§717(c) and (717)d, speaks throughout of

"civil actions." The specific statutory use of "civil action"

plainly means a district court trial proceeding, not mere

judicial review of an administrative record. Constrast the

statutory language of § 10(a) of the Administrative Procedure

.

Act, 5 U.S.C. § 702, which describes the general right of review

from administrative proceedings in terms of, "A person suffering

legal wrong because of agency action, or adversely affected or

aggrieved by agency action within the meaning of a relevant

statute, is entitled to judicial review thereof." For the scope

of review under the APA, see 5 U.S.C. § 706. § 717(c) is

clearly in derogation of the limited APA judicial review provisions

which would control in the absence of specific statutory language. 2a/

Second, § 717 fails to draw any distinction between

judicial scrutiny when the administrative process has not been

initiated within 180 days, is incomplete, or is final either !

at the agency or CSC level. Only the requirement of a trial

de novo in every case no matter its administrative posture

comports with this specific right of action framework in which

employment discrimination complaints need only partially exhaust

administrative procedures before seeking review. Before enactment

of 717(c), the courts, sec, e.g., Gnotta v. United States, supra:

Harris v. Nixon, supra.Congress of Racial Equality v. Commissioner, supra,/and thc CSC,

see, e.g., citations to specific parts of hearings, i nfra, at

n. 6 , had considered the question of judicial review only in terms

of review a fter final agency or CSC action. congress made clear

2a/ "Unlike review of agency actionPurSUant to section 10 of tit Procedure Act whereby the court merely determines whether an

agency's action is supported by substantial evidence, on action by an aggrieved federal employee under the 1972 Act requires a

trial de novo." 3ape « Hart, Title VII Reconsidered: The Equal

2

-11-

• • .. . c flpfprence to prior- administirstiveby express provision that this deference eu v

action was no longer the law.

Third, § 706, specifically incorporated by §§ 717(c)

and 717(d), provides inter alia that private employees and state

or local government employees may bring civil actions against

their employer for employment discrimination. Prior to 1072,

the federal courts had made clear that plaintiffs suing under

§ 706 were entitled to a trial do novo. See, , Robi nson_'m

tori Hard corp., 644 F.2d 791, SCO (4th Cir. 1971), cerH. dis

missed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971): Beverly V. bone Star bead Con-

p 2d 1136, 1140-42 (5th Cir. 1971): Flowers struction Corp., 437 F.2d

V. local 6 laborers International Union of Port)' America.

431 F .2d 205, 206-08 (7th Cir. 1970): Fekete_v.,. United States

Steel Corp.. 424 F.2d 331. 334-36 (3rd Cir. 1970). Smithy.

■ services. I n c , 454 F.2d 154, 157 (5th Cir. 1972),

decided before enactment, had also stated the prevailing rule

that agency action in private employment "is not agency action

of a quasi-judicial nature which determines the rights of the

parties subject only to the possibility that the reviewing court:

might conclude that the EEOC)s actions are arbitrary, capricious

or an abuse of discretion." but "takes on the character of a

trial do novo, completely separated from the actions of the

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972,

(1972). The authors are, respectlv

of Congressional Affairs, 22CC,

General oubcomm. on Labor of the n.

1+0 Geo. Wash. L.R. 829-,857

ely, Deputy Director, Office

Professional Staff Member,

R. Comm, on Education and Labor

3/ These cases were cited by the Supreme Court

poiiglnss Corp. v. Green, supra, 411 U.S. at 799

proposi tion.

in McDonncl1- for the same

-12-

EEOC. United States v. H. K. Porter Company, N.D. Ala. 1968,

226 F. Supp. 40; King v. Georgi£L^wer_C°. [295 F. Supp. 943

(N.D. Ga. 1960)1." §§ 717(c) and 717(d) incorporated this prior

caselaw construing the meaning of § 706.

Fourth, § 706(f)(4), specifically incorporated by §§ 717(c)

and 717(d), authorizes the district court to appoint a special

master if the court has not "scheduled the case for trial within one

hundred and twenty-five days after issue has been joined" (emphasis

added) in order to expedite Title VII adjudications. § 706 (f) (4)

also speaks throughout of the duty of district courts "to hear_and

Hm-nrmvine the case" (emphasis added). Moreover, § 706 (j), also

specifically incorporated by §§ 717(c) and 717(d), provides that

any civil action or proceeding before the district court is

"subject to appeal" under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1291, 1292.

Fifth, if Congress had intended something less than a trial do

novo of the merits, it could readily have done so. Indeed, § 706(b)

provides that the EEOC "shall accord substantial weight to final

4/ The Section-By-Section Analysis of H.R. 1746, The Equal 4/ The 6ecri *„nitv Act of 1972 explaining the major pro- Employment Opportunity Act ui ^ referencevisions of the 1972 Act, as reported from the Conferenc

Committee, specifically states:

In any area where the new law does not

address itself, or in any areas where a

specific contrary intention is not indicated,

it was assumed that the present caselaw as

developed by the courts would continue to

govern1the applicability and construction of

Title VII.

. . .-4- tqaa Furthermore, the general ruleLegislative H isto ry at 1844 F th^ ^ tGrrns Qf a s t a tu t e

has always been that the adop as it existed at the

5 Z ° W “ rv

etiect R.— e— :— _--•-- to m q ? ^ ; Hassctt v. Welch,vnr.nl v. Davcnnort, 271 U.S. 33, 3« 12------ ----------

*303 U.S. 303, 314 (1938).

-13-

rr

findings and orders" of state or local deferral agencies under

state or local fair employment practice laws. Congress thus

made clear its intention on the face of the statute.

"IT]here is no court that has power to defeat the

intent of the legislature, when couched in such evident and

express words as leave no doubt whether it was the intent

of the legislature, or no." 1 Blackstone's Commentary 91

cited in Colder v. Bull, 3 Dali. 386 (1798). "Nothing is

better settled than that, in the construction of a law, its

meaning must first be sought in the language employed. if that

be plain, it is the duty of the courts to enforce the law as

written, provided it bo within the constitutional authority

of the legislative body which passed it." United States v.

Standard Brewery, 251 U.S. 210, 217 (1920). No question can

arise that federal employee civil actions to enforce equal

employment opportunity are unconstitutional; the duty of federal

courts pursuant to § 717(c) is therefore clear.

-14-

"\ S I •

I I .

§ 717 OF TITLE VII, AS A MATTER OF

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY, REQUIRES A TRIAL

DE NOVO IN CIVIL ACTIONS BROUGHT PURSUANT gro ITS PROVISIONS .5/

The legislative history of § 717 reiterates what is

clear from the face of the statute, that a trial do novo is

required. Congress, first, was dissatisfied with the un-

reviewable operation of the CSC complaint process and, second,

accorded § 717(c) civil action plaintiffs the same right to

invoke the jurisdiction of the federal courts as § 706

t

plaintiffs fo enforce equal employment opportunity.

Dissatisfaction With Administrative Remedies

The unanimous opinion of the Supreme Court in Morton v .

Maneari, 41 L.Ed. 2d 290, 298 (1974) , surveying the legisla

tive history of § 717, stated:

5/ H.R. 1746, reported out of the House Committee on Education and Labor gave the EEOC administrative jurisdiction over federal employees, § 717(b), and permitted an aggrieved

employee to file a civil action within 30 days after final

EEOC action, § 717(c), Legislative History at 27-28. The

House replacement, H.R. 9247, omitted the coverage of federal employees, Legislative History at 326-32. S.21315 which tracked the provisions of H.R. 1746 was sponsored by Senator

Williams in the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare,

Legislative History at 185-87. However, the Senate Committee

unanimously reported out a version of S.2515 which substituted

CSC administrative jurisdiction over federal employees, § 717(b),

and permitted a civil action under the conditions of the present law, § 717(c), Legislative History at 407-08. The terms

of § 717(c) were suggested by Clarence Mitchell of the NAACP and authored by Senator Cranston and Senator Dominick within the

Senate Committee, Legislative History at 493-94, 695. The Senate Committee version of § 717(c) passed the Senate without change, Legislative History at 1788. At the conference, the House

receded and the Senate version was accepted, Legislative History at 1819. .

-15-

o *

The 1964 Act did not specifically outlaw employment discrimination by the federal govern

ment. 21/ Yet the mechanism for enforc inq long-outstanding Executive Orders for bidding government discrimination had prove

ineffective for the most pert. 22/ ™ °rc,cr toremedy this, Congress, by the 1972 Act. amended the 1964 Act and proscribed discrimination in most areas of federal government,

in general, it may be said that the sub stantive anti-discrimination law embraced in

Title VII was carried over and applied to the

Federal Government. As stated in the House

Report.

"To correct this entrenched discrimination

in the Federal service, it is necessary to insure thq effective application of uniiorm,

fair and strongly enforced policies. The present law and the proposed statute do not. permit industry and labor organizations to

be the judges of their own conduct in the area of employment discrimination. There is

no reason why government agencies should not

be treated similarly." II.R. Rep. No. 92-238,

on H.R. 1746, 92d Cong., 1st Scss. 24 2a (1971)• [Language derived from statements

of Clarence Mitchell of the NAACP in Hearings

on H.R. 6228 & II.R. 13517 Before the General

Subcomm. on Labor of the House Comm, on

Education and Labor, 91st Cong., 1st &Sess. at 112 (1970); Hearings on S.24u3,Before the Subcomm. on Labor of the SenateCommittee on Labor and Public Welfare, 9ist ..Cong., 1st Sess. at 79 (1969).] (bracketed items added)

21/ The 1964 Act, however, did contain a pro

viso, expressed it somewhat precatory

language:

"That it shall be the policy of the United States to insure equal employment opportunities

for Federal employees without discrimination

because of race, color, religion, sex or nationa

origin." 78 Stat. 234.

This statement of policy was reonactod as 5 IJ.s.C.

§7151, (5 U.S.C.S. §71511, 80 Ktnt. 52 3 (I860), am) the

1964 Act's proviso was repealed, isl* # at 66 .

22/ "This disproportionatte [sic] distribution of

-16-

minorities and women throughout the Federal

bureaucracy and their exclusion from hiyher level policy-making and supervisory positions

indicates the government's failure to pursue its

policy of equal opportunity.

"A critical defect of the Federal equal employment program has been the failure of the

complaint process. That process has impeded rather than advanced the goal of the elimination

of discrimination in Federal employment. 11.R.

Rep. No. 92-238, on H.R. 1746, 92d Cong., 1st

Sess., 23-24 (1971).

The principal reason for the enactment of § 717, as the Kancari

opinion indicates, was strong dissatisfaction with the admin

istrative complaint process created by the CSC under authority

W

of the Executive Orders.

■6/ The complete statement of the House Report was that:

This disproportionatte distribution of minorities

and women throughout the Federal bureaucracy and

their exclusion from higher level policy-making and supervisory positions indicates the govern

ment's failure to pursue its policy of equal oppor

tunity.

A critical defect of the Federal equal employment

program has been the failure of the complaint pro cess. That process has impeded rather than advanced

the goal of the elimination of discrimination in

Federal employment. The defect, which existed under the old complaint procedure, was not corrected

by the new complaint process. The new procedure,

intended to provide for the informal resolution of

complaints, has, in practice, denied employees adequate opportunity for impartial investigation

and resolution of complaints.

Under the revised procedure, effective July 1,

1969, the agency is still responsible for investigating and judging itself. Although the procedure pro

vides for the appointment of a hearing examiner from an outside agency, the examiner docs not have the authority to conduct an independent investigation. Further, the conclusions and findings of the

examiner are in the nature of recommendations to

the agency head who makes the final agency determination as to whether discrimination exists. Although

-17-

the complaint procedure provides.for an appeal

to the Board of Appeals and Review in the Civil Service Commission, the record shows that the

Board rarely reverses the agency decision.

The system which permits the Civil Service Commission to sit in judgment over its own practices and procedures which themselves may raise questions

of systemic discrimination, creates a built-in

conflict-of-interest.

Testimony reflected a general lack of confidence

in the effectiveness of the complaint procedure on

the part of Federal employees. Complainants were skeptical of the Civil Service Commission's record

in obtaining just resolutions of complaints and

adequate remedies. This has discouraged persons

from filing complaints with the Commission for fear that it will only result in antagonizing their

supervisors and impairing any hope of future advance

ment.

Aside from the inherent structural defects the

Civil Service Commission has been plagued by a general lack of expertise in recognizing and isola- ing the various forms of discrimination which exist

in the system. The revised directives of Federal

agencies which the Civil Service Commission has

issued are inadequate to meet the challenge of eliminating systemic discrimination. The Civil Service Commission seems to assume that employment

discrimination is primarily a problem of malicious

intent on the part of individuals. It apparently

has not recognized that the general rules and pro

cedures it has promulgated may actually operate to the disadvantage of minorities and women in systemic

fashion. All too frequently policies established

at the policy level of the Civil Service Commission do not penetrate to lower administrative levels.The result is little or no action in areas where unlawful practices are most pronounced. Civil Service selection and promotion requirements are

replete with artificial selection and promotion requirements that place a premium on "paper" credentials

which frequently prove of questionable value as a

6/ (Continued)

-18-

f?/ (Continued)

means of predicting actual job performance.^ The problem is further aggravated by the agency's use

of general ability tests which are not aimed at any direct relationship to specific jobs. The inevitable consequence of this as demonstrated by

similar practices in the private sector, and,

found unlawful by the Supreme Court, is that

classes of persons who are culturally or educationally disadvantaged are subjected to a heavier

burden in seeking employment.

To correct this entrenched discrimination in the

Federal service, it is necessary to insure the effective application of uniform, fair and strongly

enforced policies. The present law and the proposed

statute do not permit industry and labor organizations to be the judges of their own conduct in the area of employment discrimination. There is no reason why government agencies should not be treated

similarly. Indeed, the government itself should set the example by permitting its conduct to be reviewed

by an impartial tribunal.

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, on H.R. 1746, 92d Cong. 1st Sess. at 23-25 (1971); Legislative History at 83-85.

See generally, id. at 22-26, Legislative History at

82-85.

Similarly, the Senate Report stated:

One feature of the present equal employment oppor tunity program which deserves special scrutiny by the Civil Service Commission is the complaint process. The procedure under the present system, intended to provide for the informal disposition of complaints, may have denied employees adequate opportunity for

impartial investigation and resolution of complaints.

Under present procedures, in most cases, each

agency is still responsible for investigating and judging itself. Although provision is made for the

appointment of an outside examiner, the examiner does not have the authority to conduct an independent

investigation, and his conclusions and findings are

in the nature of recommendations to the agency head

who makes the final agency determination on whether

there is in fact, discrimination in that particular

-19-

•6/ (Continued)

case. The only appeal is to the Board of Appeals and Review in the Civil Service Commission.

The testimony Before the Labor Subcommittee re

fleeted a general lack of confidence in the effectiveness of the complaint procedure on the part of

Federal employees. Complaints have indicated skepticism regarding the Commission's record in obtaining Just resolutions of complaints and adequate

remedies. This has, in turn, discouraged persons from filing complaints with the Commission for fear

that doing so will only result in antagonizing their supervisors and impairing any future hope of advance

ment. The new authority given to the Civil Service

Commission in the bill is intended to enable the

Commission to reconsider its entire complaint structure and the relationships between the employee,

agency and Commission in these cases.

Another task for the Civil Service Commission is

to develop more expertise in recognizing and isolating the various forms of discrimination which exist

in the system it administers. The Commission should be especially careful to ensure that its directives

issued to .Federal agencies address themselves to the various forms of systemic discrimination in the system. The Commission should not assume that employ

ment discrimination in the Federal Government is solely a matter of malicious intent on the part of individuals. It apparently has not fully recognized

that the general rules and procedures that it has promulgated may in themselves constitute systemic

barriers to minorities and women. Civil Service selection and promotion techniques and requirements

are replete with artificial requirements that place a premium on "paper" credentials. Similar require

ments in the private sectors of business have often

proven of questionable value in predicting job per

formance and have often resulted in perpetuating existing patterns of discrimination (sec e-q• Griggs

v. Duke Rower Co., supra n.1). The inevitable consequence of this kind of technique in Federal employ

ment, as it has been in the private sector, is that classes of persons who are socio-economically or

educationally disadvantaged suffer a very heavy burden in trying to meet such artificial qualifica

tions .

-20-

t

6/ (Continued)

It is in these and other areas where discrimina

tion is institutional, rather than merely a matter

of bad faith, that corrective measures appear to

be urgently required. For example, the Committee

expects the Civil Service Commission to undertake a thorough re-examination of its entire testing and qualification program to ensure that the standards

enunciated in the Griggs case are fully met.

Senate Rep. No. 92-415, on S.2515, 92d Cong., 1st Scss. at 14-15 (1971); Legislative History at 423-25. See generally, id. at 12-17; Legislative History at

421-26.

See, Hearing On S.2453 Before The Subcomm. On Labor Of The

Senate Comm, on Labor and Public Welfare; 91st Cong., 1st Sess.

at 35-36 (comments of Senator Cranston); 61 (comments of EEOC member, Clifford L. Alexander); 76 (comments of Joseph L. Rauh);

77-80, 02-04 (testimony of Clarence Mitchell, NAACP); 170-91 (testimony of Julius W. Hobson) (1969) ; Hearings on II.R. 6228

& H.R. 13517 Before the General Subcomm. On Labor of the House

Comm, on Education and Labor, 91st Cong., 1st & 2d Sess. at 110-12 (statement of Clarence Mitchell, NAACP); 144-66 (testimony

of Panel of Federal Employees); 1963-65, 190-205, 238-40 (comments of Chairnuin Hawkins) ; 247 (comments of Rep. Erlenborn) ;

248 (comments of Rep.Mink)(1970); Hearings on H.R. 1746 Before

the General Subcomm. on Labor of the -House Comm, on Education

and Labor, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 126-28 (comments of Rep.Mink); 129-30 (comments of Rep. Reid); 153-59 (testimony of Clarence Mitchell, NAACP); 363-64 (comments of Chairman Hawkins);

387-90 (statement of Clarence Mitchell, NAACP); 390-421 (testimony of Warren Anderson, Black Committee) (1971) ; Hearings

on S.2515, S .2617 & H.R. 1746 Before the Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm, on Labor and Public Welfare, 92d Cong. 1st Sess. at 198 (testimony of Hon. Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, Chair

man, U.S. Comm, on Civil Rights), 201-08 (testimony of Hon.

Walter E. Fauntroy, District of Columbia Rep.); 208-26 (state

ment and testimony of Clarence Mitchell, NAACP); 275-80 (testimony of Daisy B. Fields, Federally Employed Women, Inc.),

458-68 (statement of Julius W. Hobson) (3.971) ; Note, Racial

Discrimination in the Federal Civil Service, 38 Geo. Wash. L.Rev. 265 (1969) (influential law review article cited throughout

hearings) .

For defense of the CSC complaint process, see Hearings On

S.2453 Before the Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm, on Labor and Public Welfare, 91st Cong. 1st Sess. 127-46 (testimony of Robert E. Hampton, Chairman, CSC) ; Hearings on II.R. b238 &

H.R. 13517 Before the General Subcomm. on Labor of the House Comm, on Education and Labor, 91st Cong., 1st & 2d Sess. at 191-

240 (testimony of Irving Kator, CSC)(1970); Hearings on H.R.

1746 Before the General Subcomm. on Labor of the House Comm.

-21-

Both the Senate and House Reports agreed on the need to

provide for judicial scrutiny of agency disposrtion of employ

ment discrimination claims no matter which federal agency —

CSC or the EEOC - ended up presiding over the administrative

complaint procesi^The new authority given to the Civil Service

Commission in the bill is intended to enable the Commission

to reconsider its entire complaint structure and the relation

ships between the employee, agency and commission in these

cases." Sen. Rep.. SHESa. « M* Legislative History at 423.

The Senate Report, which allowed the CSC to supervise the

complaint process, stated:

An important adjunct to the strengthened^Civil Service Commission responsibilities is

tie statutory provision of a private rrght

of action in the courts by Federal employees

who are not satisfied with the agency or

Commission decision.

6/ (Continued)

on Education and Labor, 92d Cong., ^^Sess. (ig71). Hearings

(statement and testimony 1746 Before" the Subcomm. on Labor ofon S.2515, S .2617 & H.R. 174b Bctore 92d Cong., 1st

the Senate Comm, on Labor and Publ irving Kator (1971).Sess. at 291-344 (testimony & statement o£ irvinj

7/ The debate in Congress bot^eJ"d^ai°e^ployeeshto the EEOC

administrative jurisdiction ov<? w,th the CSC did not involve and those who sought to leave it wr h the q£ fche csc

any disagreement about the un. ^ both sides that the

complaint process. There was ^ ^ t LpSrtSnitJ in the federal CSC had not enforced equal cmpl y Pl 2515. 92d Cong.,

service. C ^ . Leg°blatltf kiTJ'U 421-26. ViRth.1st Sess. at ^-17 (1971N “ 9 92d c , lst Sess. at

H.R. Rep- No. 92-238, on H **j 82-86. Sec citations to22-28 (1971); Legislative History at 82 8b. £ th£J issue

specific parts of hearings, g.u p p , • • _ could do a better

was practical, whether the over ur w §"717 strictures. See,

gob than CSC s2617 and H.R. 1746 Before the

f ^ J T ^ T a b ™ of^the'Senate Co-, on Labor and Public

-22-

The testimony of the Civil Service Com

mission notwithstanding, the committee found

that an aggrieved Federal employee does not

have access to the courts. In many cases,

the employee must overcome a U.S. Government

defense of sovereign immunity or failure to

exhaust administrative remedies with no

certainty as to the steps required to exhaust

such remedies. Moreover, the remedial authority

of the Commission and the courts has also been

in doubt. The provisions adopted by the com-

mittcc will enable the Commission to grant full

relief to aggrieved employees, or applicants,

including back pay and immediate advancement as

appropriate. Aggrieved employees or applicants

will also have the full rights available m the

courts as are granted to individuals in the

private sector under Title VII.

Senate Rep. No. 920415, on S.2515, 92d Cong.,

1st Sess. at 16-17 (1971); Legislative History

at 42 5.

The House Report, which allowed the EEOC to supervise the

complaint process, concurred:

Despite the series of executive and administrative

directives- on equal employment opportunity, Federal

employees, unlike those in the private sector to whom Title VII is applicable, face legal obstacles

in obtaining meaningful remedies. There is serious doubt that court review is available to the aggrieve

Federal employee. H.R. Rep. No. 92-938, on H.R.1746, 92d Cong.. 1st Sess. at 25 (1971); Legislative

History at 85.

Senator Dominick, who with Senator Cranston, authored § 717(c),

set forth his view of the critical enforcement role the courts

TJ (Continued)

Welfare, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 61-62

William II. Brown III, Chairman, EEOC), 198 Theodore Hcsburgh, Chairman, U.S. Comm. On

295 (comments of Irving Kator, CSC)(1971), Before the General Subcoram. on Labor of the

(statement of (comments of Hon. Rev.

Civil Rights); 292-93,

Hearings on H.R. 1/46 House Comm, on Educa

tion and Labor. 92d Cong.. 1st Sess. at 113-30 (testimony of Harold Glickstein. Staff Director, U.S. Comm. On Civil Rights).

-23-

should play in exorcising their 717(c) jurisdiction.

It is overly simplistic to arguo as many have,

that protection of employees rights can best bo

achieved by vesting the present pro-employee (EEO]

Commission with as much enforcement power as

possible. The vicissitudes of Presidcntially appointed Boards is legend. The administrative Board possessing enforcement powers most similar

to the cease and desist powers advocated by the

majority, the National Labor Relations Board,

provides the best example of this. Critics

charge that the NLRB, in reacting to political winds rather than stare decisis, have fluctuated from pro-management decisions during the Eisenhower Administration to pro-labor positions during the Johnson and Kennedy Administration. Determination

of employment civil rights deserves and requires

non-partisan judgment. This judgment is best

afforded by Federal court judges who, shielded

from political influence by life tenure, arc more likely to withstand political pressures and render their decisions in a climate -tempered by judicial reflection and supported by historical judicial

independence. i

Likewise simplistic reasoning has classified

proponents of court enforcement as being pro

respondent or anti — employees 1 rights. Nothing

could be less correct. Both procedures seek to achieve the same end— the fair redress of employees-' grievances. Althoug I opposed the cease and desist provisions, I voted to report S.251d , as amended,

out of committee favorably as I was most encouraged by the potential relief its compromise amendments offered federal employees. As the report indicates,

these employees are the most frustrated in achieving equal employment opportunity. I authored an amend

ment with Senator Cranston which was adopted that provided the approximately 2.6 million civil service

and postal workers with court redress of their employment discrimination grievances. The amendment creates

machinery suggested by Clarence Mitchell, Director,

Washington Bureau, NAACP, whereby an aggrieved civil

service or postal employee has the option after exhausting his agency remedies, of either instituting

a civil suit in Federal district court or continuing

through the Civil Service Board of Appeals and Re

views to district court, if necessary.

Senate Rep. No. 92-415, on S.2515. 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 85-86 (1971); Legislative History at 493-94.

-24-

Senator Dominick’s similar position on judicial enforcement

for private employees, JlcI- at 86-87, Legislative History at

494-99 ̂ as utilizing special assets of both the executive and

judicial branches and providing an expeditious and final

remedy, also eventually prevailed.

Floor debate on § 717(c) was minimal. As Senator Williams

puts it:

Another significant part of the bill and one

that has not had very much debate because it was so clearly accepted at the committee level, concerns our Federal Government employees. The

requirement of equal employment opportunity i.̂

extended by statute to these employees, and for the first time a clear remedy is provided enabling

them to pursue' their claims in the district courts

following a Civil Service Commission or agency

hearing. Legislative History at 1768.

Proponents of § 717(c) set forth its requirements without

8/encountering any dissent.

The Congressional reports and floor debate reflect the

consensus of the framers of §717(c) evinced during hearings on

the bills that:

. . . perhaps this a matter f1.e., the intransigence

of federal agencies] that should be resolved in the

courts. I don't think the Executive can take pri mary responsibility for being its own watchdog. 1

think that is part of the reason for having the

courts. It equally is a better procedure. I can visualize moments where you would have a President

who would be very strong in the area and moments where this might not be the case, or where you

8/ Legislative history at 1722-25 (comments of Sen. Cranston),

1725-27 (comments of Sen. Williams); 1727-30 (Analysis of Federal

Employment submitted by Sen. Williams); 1744-52 (comments of

Sen. Cranston); 1752-04 (submissions of Sen. Cranston); 177 (section-by-section analysis) 269-72 (comments of Mr. Fauntroy);

288-92 (comments of Rep. Badillo).

-25-

would have White House staffers who might look^ more South than North, and in any event. I don t

think you are going to be upheld.★ ★ ★

What I am saying is that if we are really going to change the structure of the Government and open

i.t up in certain areas where it should be opened

then we are going to have to have remedies that reach beyond the Executive’s capacity not to act.

Hearings on H.R. 6228 & H.R. 13517 Before the General Subcomra. on Labor of the House Comm, on Education and Labor, 91st Cong., 1st & 2d Sess.

at 237-38 (1970) (comments of Rep. Reid).

Civil rights activists and representatives of black federal

employees specifically took issue with the CSC at hearings that

aggrieved federal employees could invoke judicial review after

exhausting administrative remedies under preexisting law.

“Government employees must be given access to the Federal courts

so that discriminatory action by the Government will stand no

longer as a wrong without a remedy behind the veil of sovereign

immunity." Hearings on H.R. 1746 Before the General Subcomm.

on Labor of the House Comm, on Education and Labor, 92d Cong.,

1st Sess. at 391-92 (testimony of Warren Anderson, Black

Committee). An example of this conflict between civil rights

activists and the CSC, resolved eventually by the Committee

and the full Congress in favor of the civil rights activists, is

the following colloguy between Clarence Mitchell of the NAAC1

and Irving Kator of the CSC:

Mr. MITCHELL. Would you indulge me just to ask if you will ask the Civil Service Commission

while they are here whether there is any way that a complainant who is unable to get redress before

the Board of Appeals and Review can get redress by

going into the Federal Courts?

-26-

The CHAIRMAN. I am glad you have asked me to

ask the question; and without rephrasing it, 1

think you heard it, Mr. Kator.

Mr. KATOR. Yes, Mr. Chairman.Mr. Mitchell, an employee dissatisfied with a

decision of the Commissions Board of Appeals and

Review may get into court. I think we cited in our written statement a recent case in the Colorado

district, which made this very clear, that permits the employee to move from the Commission's Board of Appeals and Review directly into the courts for

review of that procedure.

The CHAIRMAN. Does that seem responsive, Mr.

Mitchell?

Mr. MITCHELL. Yes; but it is not in line with

our experience.As I pointed out in my testimony yesterday, we have filed a complaint against the Commission at

HUD here in the U.S. District Court for the District

of Columbia, and we have had to rely on at least four different statutes plus the fifth amendment,

and it is by no means clear at this point that the

courts will uphold that principle on which we are

relying.Now, if we ultimately win, we would, of course,

take at least about 4 years to do it according to

the Supreme Court. But it seems to me by doing

what the bill proposes to do, the whole thing would be simplified and we would have a clear

channel into the courts under the statute as pro

posed in this bill.

Hearings on S.2515, S.2617 & H.R. 1746 Before the

Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm, on Labor

and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 296 (1971)

9/

The position of the CSC, specifically rejected by the

Congressional committees, was that there was no need for an

cj/ Hearings on H.R. 6228 & H.R. 13517 Before the General .mb

comm, on Labor of the House Comm, on Education and Labor, 91st

Cong., 1st & 2d Sess. at 216 (testimony of Mr. Kator)(1970);

Hearings on H.R. 1746 Before the General Subcomm. on Labor of the House Comm, on Education and Law, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 320, 322 (testimony of Mr. Kator); 305-86 (CSC statement)(1971);

Hearings on S.2515, S.2617 & H.R. 1746 Bcfre the Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm, on Labor and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 301 (statement of Mr. Kator), 310 (CSC statement) (U71) .

-27-

express statutory right of action. In light of this legisla

tive history, the CSC complaint process upon which Congress delib

erately imposed a system of judicial safeguards, should be

subjected to the closest scrutiny and little deference given to

findings and decisions of no discrimination.

Intent To Accord Federal Employees The Same Enforcement

Rights As Private Employees-------- _ -------------- ------

A second point on which there was consensus in the legis

lative history, as reflected in language incorporating § 706

provisions, was that the right of action accorded federal

employees by § 717(c) should be the same right of action pre

viously conferred upon private employees by § 706, i . > trial

de novo . See Robinson v. Lorrillard Corp., supra ; Rev e r I y.. v

Lone Star Lead Construction Corp. , supra; Flowers v. Loca3r _6

Laborers International Union of North America, supra; Poketo

v. United States Steel Corp.; Smith v. Universal^ScrviccSj— 1 ~̂—

supra. The Senate Report stated that, "Aggrieved employees

or applicants will also have the full rights available in the

courts as are granted to individuals in private sector under

Title VII." (emphasis added) Sen. Rep. No. 92-415, on S.2j15,

92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 16 (1971); Legislative History at 425.

The House Report said no less: " . . . there can exist no

justification for anything but a vigorous effort to accord

Federal employees the same rights and impartial treatment which

the law seeks to afford employees in the private sector,

(emphasis added) H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, on H.R. 1746, 92d Cong.

-28-

?

1st Scss. at 23 (1971); Legislative History at 83. As the

Conference Report, speaking of federal employees, put it "an

aggrieved party could bring a civil action under the provisions

of Section 706," Conference Rep. No. 92-681, on H.R. 1746.

92d Cong., 2d Sess. at 21 (1971); Legislative History at 1819.

Floor debate is to the same effect. Senator Cranston,

one of the authors of § 717(c), stated:

As with other cases brought under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Federal District Court review would not be based on

the agency and/or CSC record and would be a

trial de novo . (emphasis added). 119 Cong.Rec. § 1219 (daily ed. January 23, 1973) (cor

recting error made in 118 Cong. Rec. § 228/,

Legislative History at 1744.)10/

10/ 119 Cong. Rec. § 1219 states:

Unfortunately, Mr. President, the word "not" was mi solaced . . . the bound volume of the Congres

sional Record . . . will set forth this sentence

in the correct manner as follows :

As with other cases brought under Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Federal District Court review would not

be based on the agency and/or CSC record

and would be a trial de novo.

I hope that this correction will . • • avoid anymisplaced reliance upon the incorrect version as

originally printed in the Congressional Record of

February 22, 1972.

As Senator Cranston's comment stood initially, with the transposed to the second clause, it would have misrepresented

existing law that private employees were e n t R o b i n - o n v de novo after EEOC proceedings under § 706. See BS— ac~" 0n

Lorri Hard Corn., sunran Bover \x_JLz. c -Â -a-r L - a-~—— - ~

Corn7 ~sudta; lH<^e r s . c a 1 _6_of'Itorth'to// ica, supra; Fekete v.._Unxted States otccl. Co.rl-'

Smith v

/ u 11 v.. i t — - — ■— .— . i. ■ — — Universal Services, Inc., supia.

-29-

r

Senator Dominick, the other author of § 717(c) said the same:

. it strikes me that one of the first things

we have to do is at least to put employees hold

ing their jobs, be they government or private employees, on the same place so that they have

the same rights, so that they have the same

opportunities, and so that they have the equality within their jobs to make sure that they are not being discriminated against and

have the enforcement, investigatory procedure

carried out the same way. (emphasis added) ll8

Cong. Rec. § 176 (daily ed. January 20, 1972),

Legislative History at 680-01.

Senator Dominick later reiterated his point:

It seems to me that where we are dealing with job discrimination, it makes no difference what type

of job you have, you should be entitled to - same remedies anyone else in that situation h ,

and~ thi s is a right to have the federal court determine whether or not you have been discriminated

against (emphasis added) 118 Cong. Rec. § 17/ tdaily ed. Feb. 15, 1972); Legislative History at la27

Senator Williams, sponsor and floor manager of S.2515. said no

les

Finally, written expressly into the law is aprovision enabling an aggrieved Federal employee

to file an action in U.S. District Court for a

review of the administrative proceeding record

after a final order by his agency or by the Civil

Service Commission, if he is dissatisfied with

that decision. Previously, there have been un

realistically high barriers which prevented or

discouraged a Federal employe from taking a case

to court. This will no longer be the case.

There is no reason why a Federal employee should

not have the same private right of action enjoy

by individuals in the private sector, and I

believe that the committee has acted wisely i

this regard (emphasis added).

118 Cong. Rec. § (daily ed.

Legislative History at 172/. 11_/

1972) ;

11/ Several district courts have interpr

"review of the administrative proceeding

standing alone, as limiting the scope of

eted Senator Williams

record" language,

judicial review, e

-30-

Sec also Legislative History at 681-82, 835, 1441, 1482 (comments

of Sen. Dominick); 1723 (comments of Sen. Cranston).

In committee hearings, witness after witness spoke of the

need to assure federal employees of the § 706 right to seek

redress in the courts as private and state or local government

12/employees. ~ The reason for requiring a § 706 trial de novo

is apparent. As Clarence Mitchell of the NAACP, who is

credited with suggesting the § 717(c) right of action scheme,

stated:

Under (the CSC complaint] system each agency investigates itself with the result that if

by some miracle there is a finding of discrimination, its implementation is delayed

by various obstructionists. Needless to say, such findings of discrimination are few and

far between. In fairness, it must be said

that some members of the Civil Service Commission itself and a few of the top officers of the Commission have made valiant attempts to establish workable fair employment policies.

Unfortunately, the lower levels of bureaucracy in the commission itself and in the Government agencies usually nullify these policies by using cumbersome procedures that are weighted in favor

of those who discriminate and by tolerating

supervisory personnel with known records of

discrimination.

Hearings on S.2453 Before the Subcomm. on Labor

of the Senate Comm, on Labor and Public Welfare,

11/ (Continued)

Hacklev v. Johnson, 360 F. Supp. 1247, 1252 (D.D.C. 1973).overlooks the overwhelming evidence in favor of trial de novo as well as the meaning of the statement taken as whole. Senator

Williams' statement that an employee could file an action only "after a final order by his agency or the Civil Service Comm,

is of course also inaccurate.

12/ See citation to specific parts of the hearings, supra, n . 6.

91st Cong-, 1st Sess- at 79 (1969); Hearings on H.R.

6228 & H.R- 13517 Before the General Subconun. on

Labor of the House Conun. on Education and Lcibor,

91st Cong., 1st & 2d Sess. at 112 (1970).

Only the CSC characterized judicial scrutiny as limited to a

limited review of the administrative procedure as in CSC adverse

13/action cases. These comments, however, were pitched to the

degree of judicial scrutiny the CSC claimed existed under pre

existing law. The Committee reports of course rejected the

claim of a preexisting right of action for federal employees

that obviated the need for § 717(c). Moreover, § 717(c) and

§ 717(d) specifically incorporate the § 706 civil action pro

visions with broad scope of judicial scrutiny espoused by

civil rights activitists, thus rejecting limited review of

the administrative record in adverse action litigation that

the CSC propounded. A clear choice was made. §717(c), as

Senator Dominick put it, provides "more remedies for those

who are discriminated against in Federal employment than have

ever been available to them before." 118 Cong. Rcc. §

(daily ed. 1972); Legislative History at 1526. Only a

trial de novo accomplishes this; review of the administrative

record would give the complainant nothing he didn't have before.

This Court cannot and should not permit the undoing of what

Congress so clearly intended to do and did in 1972.

12/ See Hearings on H.R. 1746 Before the General Subcomm. on Labor of the House Comm, on Education and Labor, 92 Cong.,

1st Sess. 385-86 (1971); Hearings on S.2515, S.2617 A H.R.

1746 Before the Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm, on Labor

and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 296 (1971) .

-32-

Ill.

THE STATUTORY PURPOSE OF § 7 3-7

REQUIRES A TRIAL DE NOVO IN WHICH

LITTLE WEIGHT SHOULD BE GIVEN THE

RECORD DEVELOPED DURING THE CSC DISORTMINATION COMPLAINT PROCEog_-_

as a

The lower court should have given little evidentiary weight to

prior adverse agency disposition of the discrimination complaint

natter of law in light of the statutory purpose of § 717

to completely eliminate racial discrimination in federal employ

ment. § 717(a) states that, "All personnel actions affecting

employees or applicants for employment . . - shall be made free

from any discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin." (emphasis added). Judicial precedent and

clear expression of statutory purpose require that unless prior

agency dispositions of discrimination claims meet a rigorous

standard they are not to be accorded substantial evidentiary

weight in § 717 civil actions in the federal courts. The

present revised CSC Equal Opportunity Regulations, 5 C.F.R.

Part 713, on their face and as administered, are simply not

designed to accord federal employees a substitute for the

independent judicial determination of facts concerning claims of

racial discrimination and application of controlling constitutional

and statutory principles of law of a trial dc novo.

Judicial precedent and 5 717 Statutory ̂

In two recent unanimous decisions

set forth the factors to be considered

purpose

the Supreme Court ha

w3ien deciding the

-33-

evidentiary weight to be given prior non-judicial disposition

of Title VII claims in trials de novo. In McDonnell Douglas v .

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 798-99 (1973), the Court had before it an

EEOC finding of no reasonable cause.

. . . the courts of appeal have held that, in

view of the large volume of complaints before

the Commission and the nonadversary character of

many of its proceedings. court actions under

Title VII are de novo proceedings and . . . a

Commission 'no reasonable cause' finding does not

bar a lawsuit in the case.' Robinson v. Lorillard

Corp. 444 F.2d 791, 800 (CA4 1971); Beverly v. Lone

Star Lead Construction Corp., 437 F.2d 1136 (CAS 1971); Flowers v. Local 6, Laborers inter

national Union of North America, 431 F.2d 205

(CA7 1970); Fekete v. U.S. Steel Corp., 424 F.2d

331 (CAS 1970).

This Circuit, in Smith v. Universal Services^_ZUfL* *

454 F .2d 154 (5th Cir. 1972), has elaborated upon the Supreme Court

reasoning that the record of nonadversary administrative proceeding

- 14/is necessarily suspect. In Alexander v. Gardncr-Denvcr Co.,

14/ It is not to be denied that under Title VII, the action of the EEOC is not agency action of a quasi-judicia1 nature which determines the rights

of the parties subject only to the possibility that

the reviewing courts might conclude that the EEOC's actions are arbitrary, capricious or an abuse of

discretion. Instead, the civil litigation at the

district court level clearly takes on the character

of a trial de novo, completely separate from the

actions of the EEOC. United States v. H.K. Porter

Company, N.D. Ala. 1968, 296 F. Supp. 40; King v. Georgia Power Co., supra. It is thus clear that the

report is in no sense binding on the district court

and is to be given no more weight than any other

testimony given at trial.

39 L. Ed. 2d 147 (1974), the Court similarly had before it

a prior arbitral decision of no discrimination.

14/ (Continued)I

This is not to say, however, that the

report is inadmissible. A trial de novo

is not to be considered a trial in a vacu

um. To the contrary, the district court is obligated to hear evidence of whatever nature which tends to throw factual light on

the controversy and ease its fact-finding

burden.

The Commission's decision contains

findings of fact made from accounts by different witnesses, subjective comment

on the credibility of these witnesses, and reaches the conclusion that there is reasonable

cause to believe that a violation of the Civil

Rights Act has occurred. Certainly these are

determinations that are to be made by the

district court in a dc novo proceeding. We think, however, that to ignore the manpower

and resources expended on the EEOC investigation and the expertise acquired by its field investigators in the area of discriminatory employment practices would be wasteful and

unnecessary. [454 F.2d at 157]

in contrast to the expertise of the EEOC in investigating employment discrimination, the CSC was criticized by congress

for its failure to even perceive the class nature of discnmi

nation. H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, on H.R. 1746, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 24-25 (1971); Legislative History at 84-85; Sen. Rep.

NO. 92-415, on S.2515, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. at 13 (1971);

Legislative History at 422.

-35-

r