Bakke v. Regents Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief for Petitioner, 1977. 0406c147-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d7c2caf7-7711-4918-b444-556c775d513c/bakke-v-regents-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

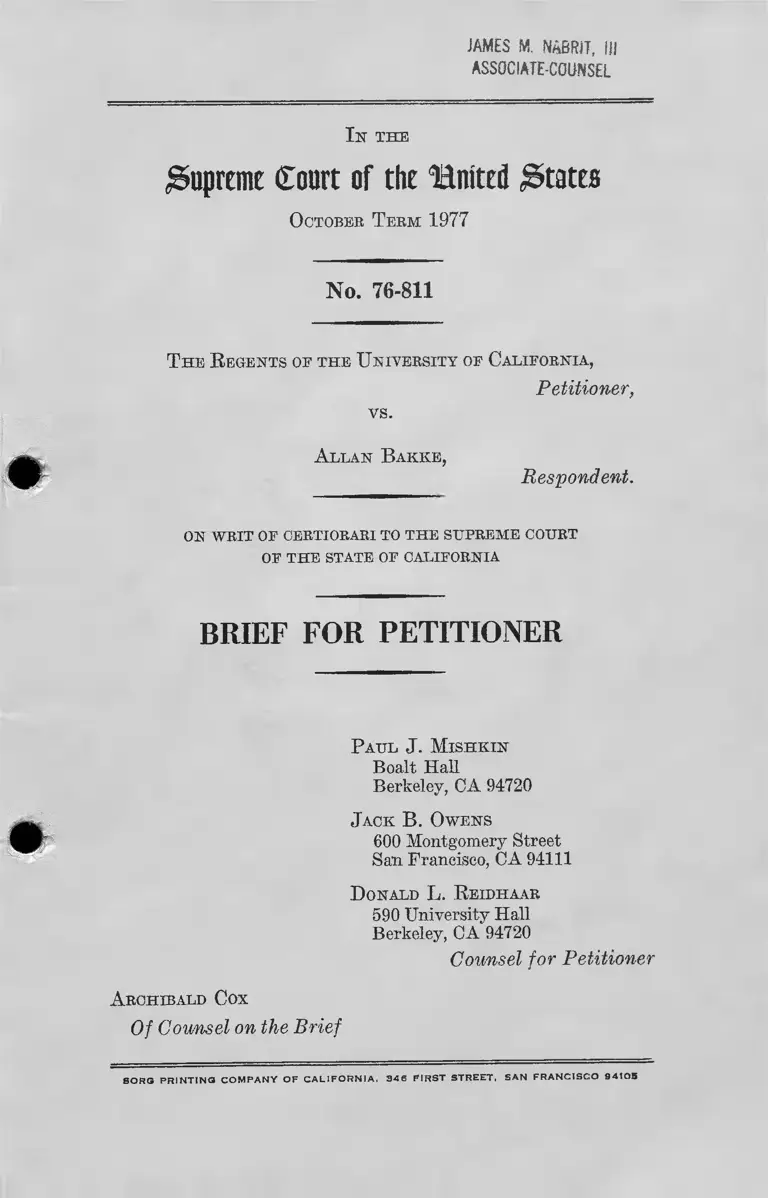

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

ASSOCIATE-COUNSEL

I n the

Supreme Court of the United States

Ogtobee Term 1977

No. 76-811

T h e R egents oe the U niversity of California,

Petitioner,

vs.

Allan B akke,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

P aul J . Mish k in

Boalt Hall

Berkeley, CA 94720

J ack B. Owens

600 Montgomery Street

San Francisco, CA 94111

D onald L . R eidhaar

590 University Hall

Berkeley, CA 94720

Counsel for Petitioner

A rchibald Cox

Of Counsel on the Brief

S O R O P R IN T IN G C O M PA N Y O F C A L IF O R N IA , 3 4 6 F IR S T ST R E E T , SA N F R A N C IS C O 9 4 1 0 5

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Opinions Below................ -........ -.................................. 1

Jurisdiction ...................................................... -........... 1

Question Presented........................................................ 2

Constitutional Provision Involved............-................ ... 2

Statement ..... ........... .......... .............-........-.................- 2

Summary of Argument...................-......-.......-.............. 8

Argument ............................................ -.............-.......... 13

Introductory...................... -................ ---.....- ........ 13

I. The Legacy of Pervasive Bacial Discrimination in

Education, Medicine and Beyond Burdens Discrete

and Insular Minorities, as Well as the Larger

Society. The Effects of Such Discrimination Can

Not Be Undone by Mere Reliance on Formulas of

Formal Equality. Having Witnessed the Failure

of Such Formulas, Responsible, Educational and

Professional Authorities Have Recognized the

Necessity of Employing Raeially-Conscious Means

to Achieve True Educational Opportunity and the

Benefits of a Racially Diverse Student Body and

Profession ......... -....................................— ........ - ^

A. The Legacy of Discrimination Continues to

Burden and to Obstruct the Advancement of

Discrete and Insular Racial Minorities..... . 17

1. The delay in implementing Brown v.

Board of Education is but one of the ele

ments of the experience of growing up as a

member of racial minority in this country.. 17

11 S ubject I ndex

Page

2. The most significant fact about doctors

from minority groups is that they are so

few, and the most significant fact about

health care for such groups is that it is

scarce and inferior....... .......................... — 21

B. Until the Advent of Special-Admissions Pro

grams, Medical Schools, Except for Two

Traditionally Black, Were White Islands in a

Multi-Racial Society.......... ...............- -....—- 26

1. Formal barriers against minority partici

pation in medical schools did not fall until

very recently and, by itself, the elimination

of those restraints did not produce racial

diversity. Indeed, mere reliance on for

mulas of formal equality raised the threat

of retrogression, rather than the prospect

of progress —............................................. 26

2. Despite the persistence of discrimination,

a pool of fully qualified minority appli

cants existed by the late 1960’s, but the

steep rise in demand for medical school

admission, coupled with the sharp in

crease in the numerical credentials of

those admitted, continued to exclude mi

norities --------------------........ -.............—- 2S

C. Special-Admissions Programs Are Intended

to Further Goals Universally Recognized As

Compelling. The Investment of Effort in Such

Programs in Professional Schools Has Been

Nationwide, and Reflects a Nationwide Recog

nition, Shared by This Court, That the Endur

ing Effects of Racial Discrimination Cannot

S ubject I ndex iii

Page

Be Countered by Mere Abolition of Formal

Barriers ............... .......................................... 32

D. Furtherance of the Goals of the Davis Pro

gram and Its Counterparts Nationwide

Unavoidably Requires the Use of Racially-

Conscious Means ____ ___ _____ ______ ___ 35

An Admissions Program Adopted Voluntarily by a

State Medical School to Counter the Effects of

Pervasive Discrimination and to Secure the Educa

tional Benefits of Racial and Ethnic Diversity in a

Student Body Accords with the Equal Protection

Clause __________-__ ____________________ 44

A. A State’s Use of Racial Criteria, Even for a

Remedial Purpose, Is Undeniably a Cause for

Concern. However, An Accurate Assessment,

Rather Than an Exaggeration, of the Basis for

Concern Is In Order. Furthermore, Identify

ing the Real Basis for Concern Represents the

Beginning, Not the End, of the Appropriate

Inquiry ................................. ................. ........ 44

1. The Davis Program Does Not Resurrect

the Insidious Quotas of Another Era. It

Sets a Goal Not a Quota; There Is Noth

ing of Constitutional Significance in the

Use of a Number to Define the Goal...... 44

2. The Relevant Concern in the Utilization

of Racial Criteria for Remedial Purposes

in Admissions Is Not the Infliction of Any

Slur or Stigma or the Infringement of

Any Right to Admission on the Basis of

Relative Merit, However Defined..... ...... 48

IV Subject I ndex

Page

3. The Relevant Basis for Concern Is a Po

tential for the Arousal of Racial Aware

ness. Identifying that Concern Repre

sents the Beginning, Not the End, of the

Requisite Analysis ................................... 57

B. The Decisions of This Court and Other Courts

Sustaining the Use of Racial Criteria to

Enhance Racial Diversity in Schools and to

Counter the Effects of Discrimination Estab

lish That the Arousal of Racial Awareness

Inevitably Produced by Special-Admissions

Programs Does Not Render Them Invalid..... 61

C. The Standard of Strict Judicial Scrutiny Is

Inapplicable in This Case ............................- 68

D. Regardless of the Weight of the Burden of

Justification, the Davis Program Does Not

Contravene the Equal Protection Clause ....... 74

1. The Means Chosen by the Medical School

Are Rationally Related to the Desired

Ends, and Under This Court’s Precedents

the Challenged Program Is Therefore

Constitutional .......................................... 74

2. If Use of Racial Criteria In a Remedial

Context Triggers an Intermediate Stand

ard of Review, the Davis Program

Meets Such a Standard ........................... 77

3. Measured Against the Standard of Strict

Judicial Scrutiny, the Davis Program Is

Constitutional ............................................ 79

Conclusion ................................... ................................. 86

CITATIONS

Cases:

Pages

A levy v. Downstate Medical Center, 39 N.Y.2d 326,

334-35, 348 N.E.2d 537, 544-45, 384 N.Y.S.2d 82, 89

(1976)........................ .....................................64, 72, 77, 79

American Party of Texas v. White, 415 U.S. 767

(1974)........................................................................ 85

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) .....................61, 78

Associated General Contractors of Massachusetts, Inc.

v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (CA 1, 1973), cert, denied

416 U.S. 957 (1974) ............................. ...... ............... 67

Balaban v. Rubin, 14 N.Y.2d 193, 199 N.E.2d 375, 250

N.Y.S.2d 281, cert, denied 379 U.S. 881 (1964).......... 64

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45 (1908)............ 86

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) ........................ 20

Booker v. Board of Education, 45 N.J. 161, 212 A.2d

1 (1965) .................................... ............................... 64

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1, 24 (CA5 1966) ................. 68

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)....passim

Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134 (1972) .................... . 85

Califano v. Goldfarb, 97 S.Ct. 1021 (1977)................... 72

Califano v. Webster, 97 S.Ct. 1192 (1977)......... ......... 77, 84

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education, 289

F.Supp. 647 (M.D.Ala. 1968), aff’d sub nom. United

States v. Montgomery County Board of Ed., 395

U.S. 225 (1969)............ - ............................... ........... . 66

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (CA8) (en banc),

cert, denied 406 U.S. 950 (1972)................................ 67

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (CA3 1971), cert.

denied 404 U.S. 854 (1971)___ ____________ ____ 67

Craig v. Boren, 97 S.Ct. 451 (1976)............. ................ 77

Crawford v. Board of Education of the City of Los

Angeles, 17 C.3d 280, 130 Cal.Rptr. 724, 551 P.2d 28

(1976) 18

VI Citations

Pages

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners, 402 U.S. 33

(1971) ........ ................. .................... ........................62, 66

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 82 Wash.2d 11, 507 P.2d 1169

(1973), vacated as moot, 416 U.S. 312 (1974).......... 64

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 (1974).... .............. 46

Dunn v. Blumstein, 405 U.S. 330 (1972)................. 80,81,82

Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 (1941)..---- ------- 59

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co. Ine., 96 S.Ct.

1251 (1976)................................................................61, 66

Fuller v. Volk, 250 F.Supp. 81 (D.N.J. 1966)............... 64

G-ermann v. Kipp, 14 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. 1197

(W.D.Mo. 1977)........ ...................... ........................ 77

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

Florida, 272 F.2d 763 (CA5 1959)........ ......... ......... 21

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).... 35

In re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717 (1973)............................... 81

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915)............... 40

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954)---- ------- ---- 20

Ilirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943)...... 68, 69

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U.S. 460 (1950) ........ 47

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969)............. ....... 72

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966)............... 75

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973)....62, 65

Kirkland v. Department of Correctional Services, 520

F.2d 420, reh. en banc denied, 531 F.2d 5 (CA2

1975), cert, denied 97 S.Ct. 73 (1976)------ ---- ---- - 57

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)...... 68, 69

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974)....... ...................... 75

Local 53 of International Ass’n of Heat & Frost I. &

A. Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (CA 5 1969).... 67

Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905).................. 85

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)..... ......... 48, 49, 69, 70,

72,73, 80

Citations vii

Pages

Lubin v. Panish, 415 U.S. 709 (1974)............................81,85

Morean v. Board of Education, 42 N.J. 237, 200 A.2d

97 (1964)................................... 64

Morton v. Maneari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974)...... 20,53, 55, 75, 84

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971)...................... 36, 61

McDonald v. Santa Pe Trail Transportation Co., 427

U.S. 273 (1976).......................................................... 78

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) 16

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961)................. 74, 75

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964)..........58, 69, 70,

80, 81, 84

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (CA5 1974) ............. 67

North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971)................. ............................... 35, 61,63

Offermann v. Nitkowski, 378 F.2d 22 (CA2 1967) ...... 63

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948) ........ .....20, 69

Patterson v. American Tobacco Company, 535 F.2d

257 (CA4), cert, denied, 97 S.Ct. 314 (1976) .......... 67

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) .....................69, 70

Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (CA3 1970), cert,

denied 402 U.S. 944 (1971) ............. ..................... 66

Bios v. Enterprise Association Steamfitters Local 638

of U.A., 501 F.2d 622 (CA2 1974) ............... ........ 67

Bosenstock v. Board of Governors, 423 F.Supp. 1321

(M.D.N.C. 1976) _______ ________ _____ _____ 64

San Antonio Independent School District v. Bodriguez,

411 U.S. 1 (1973) ............................... 38, 56, 71, 74, 75, 76

School Committee v. Board of Education, 352 Mass.

693, 227 N.E.2d 729 (1967), appeal dismissed 389

U.S. 572 (1968) .............. -......................

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969)

64

19

CitationsV l l l

Pages

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 TT.S. 479 (1960) ..................... 81

Soria v. Oxnard School District, 386 F. Supp. 539

(C.D. Cal. 1974) ..................................................... 18

Southern Illinois Builders Association v. Ogilvie, 471

F.2d 680 (CA7 1972) .............................................. 67

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 311

F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal.' 1970) ............................... 18

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d

261 (CA1 1965) ....................................................... 63

State ex rel Citizens Against Mandatory Bussing v.

Brooks, 80 Wash.2d 121, 492 P.2d 536 (1972) ........ 64

Storer v. Brown, 415 U.S. 724 (1974)...... ..............82,84, 85

Sugarman v. Dougall, 413 U.S. 634 (1973) ............... 81

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) .....................................18, 63, 65, 66, 84

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234 (1957).......... 76

Tancil v. Woolls, 379 U.S. 19 (1964) ................. ....... 78

Tometz v. Board of Education, 39 I11.2d 593, 237

N.E.2d 498 (1968) ............................................... 64

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc.

v. Carey, 97 S.Ct. 996 (1977)....54, 55, 61, 63, 70, 75,77, 84

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S.

144 (1938) ................................................................ 68

United States v. International Brotherhood of Electri

cal Workers, Local No. 38, 428 F.2d 144 (CA6 1970),

cert, denied 400 U.S. 943 (1970) .............................. 67

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d 544

(CA9 1971), cert, denied 404 U.S. 984 (1971) .......... 67

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) .................................. 61,62,66

United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354

(CA8 1973) .............................................................. 67

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d

387 (CA2 1973) .....................................................40,67

Citations ix

Pages

Wanner v. County School Board, 357 F.2d 452 (CA4

1966) ........................ ......................... -..................... 63

Weinberger v. Wiesenfield, 420 U.S. 636 (1975) ..... . 77

Constitutions :

United States Constitution

Fourteenth Amendment, ....... passim

California Constitution

Article IX, Section 9 ................................................. 75

Statutes :

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3) ...................................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 2000(e), et seq............................................ 67

E xecutive Order:

Executive Order 11246, 30 F.R. 12319, as amended,

32 F.R. 14303, 34 F.R. 12985 .................—- -.......... 67

M iscellaneous :

AMA News, April 8,1968, p. 8 ......................... -.......... 23

Applewhite, Blacks in Public Health, 66 J.N.M.A. 505

(1974) -........................................... 23

Association of American Medical Colleges: Proceed

ings for 1968,44 J .M ed.E duc. 349 (1969)................. 34

Bickel, The Original Understanding and the Segrega

tion Decision, 69 H arv.L.Rev. 1 (1955) ................... 73

Brest, Foreword: In Defense of the Antidiscrimina

tion Principle, 90 H arv.L.Rev. 1 (1976) ................. 19

T he Carnegie Commission on H igher E ducation, A

Chance to L earn (1970) ...................-.................. 13

Crowley & Nicholson, Negro Enrollment in Medical

Schools, 210 J.A.M.A. 96 (1969).......... -.................. - 27

Cnea, Sakakeeny & Johnson, T he Medical School Ad

missions P rocess : A R eview oe the L iterature 1955-

76 (1976) ....-........................................ 29> 30> 50>51

X Citations

Pages

Curtis, Blacks, Medical S chools and S ociety (1971)-26, 27

Datagram: Ethnic Group' Members on U.S. Medical

Faculties, 51 J.M ed.E duc. 69 (1976) ..............-............. 22

Dove, Minority Enrollment in U.S. Medical Schools,

1969-70 Compared to 1968-69, 45 J.M ed.E duc. (1970) 28

Dube & Johnson, Medical School Applicants, 1973-74

(AAMC 1976) .................................................................... 29

Elesh and SchoUaert, Race and Urban Medicine: Fac

tors Affecting the Distribution of Physicians in

Chicago, 13 J. H ealth & Soc. BEH. (1972) ............ 26

Ely, The Constitutionality of Reverse Racial Discrimi

nation, 41 U .C h i .L.Rev. 723 (1974) ............... -....... 73

Freund, Constitutional Dilemmas, 45 B.U.L.Rev. 13

(1965) ....... -.............-......................................-.....—70, 86

Gordon, Descriptive Study of Medical School Appli

cants, 1975-76 (AAMC 1977) ...................................29,36

Greenawalt, Judicial Scrutiny of ‘‘Benign” Racial

Preference in Law School Admissions, 75 Col.L.

R ev. 559 (1975) ....................................................----- 56

Gunther, Foreword: In Search of Evolving Doctrine

on a Changing Court: A Model for a Newer Equal

Protection, 86 H arv.L.Rev. 1 (1972) ........................ 85

Hamilton, Graduate S chool P rograms for M inority/

D isadvantaged S tudents (1973) ............-............... 41

Haynes, Distribution of Black Physicians in the United

States, 210 J.A.M.A. 93 (1969)................................. 22

Hutchins, Reitman, & Klaub, Minorities, Manpower

and Medicine, 42 J.M ed.Educ. 809 (1967) ..............27, 28

Jenkins, The Howard Professional School in a New

Social Perspective, 62 J.N.M.A. 167 (1970).............— 25

Johnson, History of the Education of Negro Physi

cians, 42 J.M ed.E duc. 439 (1967)................................... 22

Citations xi

Pages

Johnson, Smith & Tarnoff, Recruitment and Progress

of Minority Medical School Entrants 1970-72, 50

J.M ed.Educ. 713 (1975) ....................................29,31,45

Kaplan, Equal Justice in an Unequal World, 61 Nw.L.

Rev. 363 (1966) ..................................................... 59

Kerckhoff & Campbell, Race and Social Status Differ

ences in the Explanation of Educational Ambition,

55 J .S oc.F orces 701 (1977)........................ -............. 37

Lieberson, Ethnic Groups and the Practice of Medi

cine, 23 A m. Soc. R ev. 542 (1958).............................. 25

Mantovani, T. Gordon & D. Johnson, Medical School

Indebtedness and Career Plans 1974-75 (DHEW)

Pub.No. (HRA) 1976)....................... -..................... 26

Medical Education in the United States, 1966-67, 202

J.A.M.A. 753 (1967)................................................. 29

Medical Education in the United States, 1975-76, 236

J.A.M.A. 2949 (1976)............................................... 29

Melton, Health Manpower and Negro Health: The

Negro Physician, 43 J.M ed.E duc. 798 (1968)........... 22

Mexican- A mertcan P opulation Commission of Cali

fornia, Mexican-American P opulation in Califor

nia A pril, 1973 (1973)....................................... - .... 2

The New York Times, June 6, 1974 ............................ 23

C. Odegaard, M inorities in Medicine : F rom R ecep

tive P assivity to P ositive A ction 1966-76 (1977)

20, 23, 27, 30, 34, 37, 40, 48, 58

Raup & Williams, Negro Students in Medical Schools

in the United States, 39 J.M ed.Educ. 444 (1964)..... 26

Redish, Preferential Law School Admissions and the

Equal Protection Clause, 22 U.C.L.A.L.Rev. 343

(1974) ............................-.......-......... 72

Reitzes, N egroes and Medicine (1958) .................... 26

Citationsxii

Pages

Report of Task Force of Association of American

Medical Colleges to Inter-Association Committee

on Expanding Educational Opportunities in Medi

cine for Blacks and Other Minority Students (April

22, 1970) ................................................................... 3,34

Sandalow, Racial Preferences in Higher Education:

Political Responsibility and the Judicial Role, 42

TX.Ch i.L.Rev. 653 (1975) ................................................. 70

Seham, B lacks and A merican Medical Case

(1973) ............... 22 ,24,26

Simon and Coveil, Performance of Medical Students

Admitted Via Regular and Admissions-Variance

Routes, 50 J.M ed.Edtic. 237 (1975) ........................ 31

Sowell, New Light on Black I.Q., The New York Times

Magazine, March 27, 1977 ....................................... 43

Thompson, Curbing the Black Physician Manpower

Shortage, 49 J.M ed.Edttc. 944 (1974) ...................... 23

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce,

U nited S tates Census of P opulation : 1970........2,19, 37

39,83

U.S. Bureau of Health Manpower, Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare, Pub. No. (HRA)

76-22, Minorities and Women in the Health Fields:

Applicants, Students and Workers (1975) .............. 23,36

Waldman, E conomic and R acial D isadvantage as

R eflected in T raditional Medical S chool Selec

tion F actors: A S tudy of 1976 A pplicants to U.S.

Medical S chools. (AAMC 1977) ............................29, 38

Wechsler, Toward Neutral Principles of Constitu

tional Law, 73 H arv.L.Rev. 1 (1959) ..... ................... 71

Wollenberg, A ll Deliberate Speed : Segregation and

E xclusion in California’s S chools, 1855-1975

(1976) 18

I k the

Supreme Court of tf)t Zintteb States;

Octobee T erm 1977

No. 76-811

T h e R egents of the U niversity of California,

Petitioner,

vs.

A llan B akke,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

B rief for Petitioner

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the California Supreme Court is reported

at 18 C.3d 34,132 Cal. Rptr. 680, 553 P.2d 1152.

JURISDICTION

The California Supreme Court denied the University’s

petition for rehearing on Oetober 28, 1976 (R.494).1 The

petition for a writ of certiorari was filed on December 14,

1976 and was granted on February 22, 1977. 97 S.Ct. 1098.

The jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. § 1257(3).

1. “R” references are to the record filed in this Court.

2

QUESTION PRESENTED

When only a small fraction of thousands of applicants

can be admitted, does the Equal Protection Clause forbid

a state university professional school from voluntarily

seeking to counteract effects of generations of pervasive

discrimination against discrete and insular minorities by

establishing a limited special admissions program that in

creases opportunities for well-qualified members of such

racial and ethnic minorities ?

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION INVOLVED

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution provides in pertinent part: . nor shall any State

. . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws.”

STATEMENT

The medical school of the University of California at

Davis opened in 1968, adding 50 to the total number of

places in the nation’s medical schools. In short order the

faculty realized (as have the faculties of most medical and

law schools in this country over the past decade) that

existing admissions criteria failed to allow access for any

significant number of minority students (R. 15, 57-58, 67,

85-86). Racial and ethnic minorities at that time comprised

over 23% of the population of California (including about

7% blacks and at least 14% Mexican Americans).2 The

entering class of 1968 at Davis contained no blacks, no

Chicanos, three Asians, and no American Indians (R. 216,

282).

2. These figures are estimates based upon the results of the 1970

census, as adjusted. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Department of

Commerce, Pub. No. PC(1)-D6, U nited S tates Cen su s oe P opu

lation : 1970. Detailed Characteristics, California, Section 1, Table

139 (1973); Mexican-American Population Commission of Califor

nia, Mexica n-Am erican P opulation in Ca lieo r n ia : April 1973

at 8. (1973).

3

In the two years that followed, the medical school faculty

fashioned and implemented a special admissions “Task

Force” program3 to compensate for the effects of societal

discrimination on historically disadvantaged racial and

ethnic minorities (R. 67, 159-60). Among the objectives of

this program were enhanced diversity in the student body

and the profession, improved medical care in underserved

minority communities, elimination of historic barriers to

medical careers for disadvantaged members of racial and

ethnic minority groups, and increased aspiration for such

careers on the part of minority students (R. 67-68). It was

the judgment of the Davis faculty that the Task Force

program was the “only method” that would achieve signifi

cant enrollment of minority applicants (R. 67-68).

The program has led to entering classes at Davis of sub

stantially greater racial and ethnic diversity than in 1968.

From 1970, the first year of operation of the program,

until 1973 and 1974, the years at issue in this case, minority

students were admitted as follows:

Task Force Program General Admissions Total

Blacks Chicanos Asians Total Blacks Chicanos Asians Total Minorities

1 9 7 0 4 . . . 5 3 0 8 0 0 4 4 12

1971 ... . . . 4 9 2 15 1 0 8 9 2 4

1 9 7 2 ... . . . 5 6 S 16 0 0 11 11 27

1973 ...... 6 8 2 16 0 2 13 15 31

1 9 7 4 ...... 6 7 2 15 0 4 5 9 245

8. The “Task Force” program at Davis was part of a nation-

wide effort in which a prominent role was played by a Task Force

of the Association of American Medical Colleges; see the Report of

that Task Force to the Inter-Association Committee on Expanding

Educational Opportunities in Medicine for Blacks and Other Mi

nority Students (April 22, 1970).

4. The entering class of 1970 consisted of a total of 52 students;

the total class was increased the following year to 100, the level at

which it has remained (R. 215; 282).

5. The data appearing in this table are at R. 216-18. The record

indicates that there were 16 Task Force admittees in 1974. Ibid.

4

Under the general admissions procedure at Davis, grade-

point averages and scores on the Medical College Admis

sions Test (“MCAT”) are of major importance, but they

are not determinative. Individual attributes unrelated to

formal credentials are given weight, as are factors of

importance to the profession, such as whether the applicant

originates from and may be likely to return to an area

where health care services are in short supply (R. 64-65,

180, 183). Applicants must submit, in addition to college

transcripts and MCAT scores, a description of extracur

ricular and community activities, a history of work experi

ence, personal comments regarding reasons for wanting to

attend medical school, and letters of recommendation (R.

62, 197-200, 231-40, 282). Because the number of applicants

annually far outstrips the number of available places (e.g.,

by ratios of 25 and 37 to 1 for 1973 and 1974) and because

admissions is an arduous and time-consuming process, ap

plicants with undergraduate grade-point averages below

an arbitrarily picked figure are summarily rejected (R. 63,

205, 219, 282). Of the remaining applicants, those whose

files reflect particular promise are granted personal inter

views with members of the admissions committee (R. 62-

63).

The person conducting an interview prepares a summary

of the meeting and then assigns the applicant a score of

0 to 100. The score given takes into account many factors

The Brief of Amici Curiae in opposition to certiorari in this case

pointed out, at p. 23 n.12, that in that year there were only 15

Task Force admittees. In its Reply to that Brief of Amici, the Uni

versity acknowledged this to be a fact. In 1974, one Task Force

admittee withdrew before the start of classes and, despite the exist

ence of a Task Force waiting list, admission was then granted to a

non-minority applicant from the regular admissions process. The

reduction of Task Force admittees in 1974 from 16 to 15 occurred

after the close of discovery in this case and did not become known

to counsel until recently. See Reply to Brief of Amici Curiae in

Opposition to Certiorari, p. 5, n.4.

relating to the applicant, including formal credentials,

letters of recommendation, demonstration of motivation,

character and imagination, the type and locale of the appli

cant’s anticipated practice, whether the applicant is likely

to add diversity or make a special contribution to the

student body, and the interviewer’s assessment of the appli

cant’s potential in medicine. .After the interview, other

members of the admissions committee review tire file, includ

ing the interview summary (but minus the score assigned

by the interviewer), and assign their own scores. The

grades of individual interviewers and reviewers are then

cumulated into a total or “benchmark” number. Benchmarks

are used as the primary but not wholly controlling basis

for final decisions on admission (E. 63-65,156-58,180).

Applicants to the Task Force program submit the same

materials as applicants for general admission (E. 161, 169,

197-200, 282). Final selection of Task Force applicants, as

of applicants for general admission, is made by the full

admissions committee (E. 166). However, as to those stu

dents, the full committee acts on the recommendations of a

Task Force subcommittee, which has the responsibility for

processing Task Force applicants (E. 65-67). In practice

only disadvantaged members of racial and ethnic minority

groups are admitted under the Task Force program (E.

171). The materials submitted by minority applicants to

the Task Force program are screened to determine if those

applicants are disadvantaged, and those who are not are

referred to the general admissions process (E. 65-66, 170).

The files of the disadvantaged minority applicants are

further screened in order to select those to be invited for

a personal interview (B, 66). In the years at issue in this

litigation, the Task Force program selected for interviews

and further consideration some candidates who had grade-

6

point averages below the cut-off figure employed in the

general admissions process (E. 175). The ensuing interview

ing and rating procedures parallel those employed in gen

eral admissions (E. 66,164).

All students admitted are fully qualified to meet the

requirements of a medical education at Davis (E. 67). In

1973 and in 1974, 16 and 15 students, respectively, out of

an entering class of 100 were admitted pursuant to the Task

Force program (E. 67, 221, 282).6 The Task Force goal set

by the faculty for those years was 16 students (E. 164-66).

The students admitted pursuant to the program were

chosen from a pool of minority applicants more than ten

times the size of the group that could be offered admission,

let alone the smaller number that could actually be enrolled

(E. 205, 219, 282).

Eespondent applied for admission to the medical school

for the entering classes of 1973 and 1974 (E. 69). His was

one of 2,464 applications for admission for 1973 (E. 205,

282), and one of 3,737 applications for 1974 (E. 219, 282).

Eespondent was a highly rated applicant who came very

close to admission (E. 254, 308; Pet. App. 108a). He applied

under the general admissions program in both years, and in

both years he was granted an interview (E. 69). Students

admitted on recommendation of the Task Force subcom

mittee in 1973 and 1974 often had MCAT test scores, grade-

point averages, and benchmark ratings lower than respond

ent (E. 175-82).

Following his second rejection, respondent brought suit

in state court against the Eegents of the University of

California (the University). The trial court upheld respond

ent’s claim that the challenged program discriminated

6. See note 5, supra.

7

against white applicants on the basis of race and therefore

violated the Equal Protection Clause (Pet. App. F, p. 117a).

However, it refused to order respondent’s admission, be

cause he had not met the burden of proving that he actually

would have been admitted in the absence of the Task Force

program (Pet.App. F, pp. 116a, 117a).

The California Supreme Court took the case directly from

the trial court, “prior to a decision by the Court of Appeal,

because of the importance of the issues involved.” 18 C.3d

at 39. The highest state court held the challenged program

unconstitutional “because it violates the rights guaranteed

to the majority by the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment of the United States Constitution.” Id.

at 63. Conceding, at least for the purposes of argument, that

the objectives of the Task Force program were not only

proper but compelling, the court, wholly without support

in the record, theorized that alternatives, such as increasing

the number of medical schools, aggressive recruiting or

exclusive reliance on disadvantaged background without

regard to race, would somehow achieve real racial diversity

without giving any weight whatsoever to race. Id. at 54-55.

The court also ruled that the trial court erred in imposing

on respondent the burden of proof as to whether he would

have been admitted in the absence of the Task Force pro

gram. Id. at 63-64. In its opinion as originally released, the

court directed that the case be remanded to the trial court

for redetermination of that issue with the University bear

ing the burden of proof (Pet.App. A, p. 38a).

The University filed a petition for rehearing (R. 445).

In that petition, the University conceded that, given re

spondent’s high rating in the admissions process, it would

not be able to sustain the burden of proving that respondent

would not have achieved admission in the absence of the

Task Force program.7 The court below denied rehearing

(Pet.App. B) but modified its initial opinion to direct that

respondent be admitted (Pet.App. C).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

One of the things in which the nation may take great

pride since the end of World War II has been its willing

ness to address in actions, rather than simply words, the

racial injustices that are the unhappier parts of our legacy.

In that era, and for the first time in this century, we have

undertaken to deal vigorously and realistically with the

American dilemma by significant and persevering effort

7. E. 451, 487-88. The University resisted below, as it resists

today, the contention that it should bear the burden of proof on

whether respondent’s admission in fact turned on the existence or

nonexistence of the Task Force program. The University’s conces

sion in its rehearing petition does not constitute a reversal of that

position. Father, it reflects simply that, in light of respondent’s

proximity to admission in the years at issue, whether he would have

been admitted in the absence of the challenged program is, practi

cally speaking, a question of where the burden of proof on that

issue is allocated. The trial court in this ease found that respondent

would not have attained admission in either 1973 or 1974 even if

there had been no Task Force program (E. 389-90; Pet.App. 116a-

117a). However, in making that finding, the trial court was oper

ating on the premise that respondent bore the burden of proof (E.

383; Pet.App. 111a). Even on that assumption, the court in its

notice of intended decision declared: “There appears to the Court

to be at least a possibility that [respondent] might have been ad

mitted absent the 16 favored positions on behalf of minorities” (E.

308; Pet.App. 108a). Furthermore, although respondent’s numerical

rating did not put him in a group that was certain of admission,

it must be remembered that numerical ratings are not wholly con

trolling in the regular admissions process (E. 63-65). In addition,

in a report prepared in response to a complaint filed by respondent

with the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (see E.

281), the chairman of the admissions committee declared, “ [H]ad

additional places been available, individuals with Mr. Bakke’s rat

ings would likely have been admitted to the medical School [in

1973] as well” (E. 254).

9

and. by making the difficult adjustments inevitably in

volved in seeking to bring the reality of our society closer

to its aspirations. This Court played a major role in

articulating and imparting momentum to this commitment,

but the Court has not acted alone. The commitment to

relegate the lingering burdens of the past to the past has

run deeply and widely throughout the country, among a

great many of its institutions.

The problem also runs deep and wide. The dismantling

of the formidable structures of pervasive discrimination

requires great endurance, and the courage to maintain the

necessary great effort.

That the obstacles are formidable was clear from

the outset. But their true complexity only began to

appear after the first successful steps had been taken.

Nonetheless, those institutions that, in the exercise of

their appointed roles, confront at close range the enduring

effects of what has been handed down to us have not

shrunk from the commitment when the unforeseen com

plexities began to reveal themselves. Thus, when it be

came clear in the 1960’s that dismantling of formal racial

barriers did not itself bring long-alienated minorities into

the mainstream, the widespread response was not abandon

ment of the commitment but effort to seek new ways to

undo the continuing effects of past discrimination and to

achieve the benefits of a truly open, racially diverse

society.

The response was not only widespread; it sprang from

a broad range of independent and autonomous sources.

No central authority directed this effort. Yet toward the

end of the last decade, many governmental and private

institutions, including this Court, came concurrently to

the realization that a real effort to deal with many of

the facets of the legacy of past racial discrimination

10

unavoidably requires remedies that are attentive to race,

that color is relevant today if it is to be irrelevant tomor

row. This discovery and response was found in many

sectors of society; the school desegregation area was a

major arena, but the same phenomenon was found in

employment, housing, and many other areas, including

professional education.

This case concerns access of minorities to professional

education and careers, specifically in medicine. The experi

ence of the professional schools in the 1960’s mirrored the

picture elsewhere. The falling of formal racial barriers

failed to lead to participation by significant numbers of

minorities. All but two medical schools in the nation re

mained virtually all-white islands in a multiracial society.

Indeed, in terms of the numbers of minorities entering

medical schools, a threat of retrogression appeared.

At about the same time that other parts of the society

were independently arriving at similar conclusions, many

medical schools and national professional organizations

came to the realization that the only effective solution lay

through race-conscious admissions programs. The use of

racially-blind admissions criteria resulted in near-total

exclusion of historically disfavored minorities during a

period when the competition for medical school places was

only normally intense. The end of the last decade saw a

dramatically heightened over-all demand for admission to

medical school, which inevitably carried with it a sharp

escalation in the level of formal credentials of those attain

ing admission. These schools soon realized that failure to

devise and implement race-conscious admissions policies

would prolong indefinitely essentially all-white student

bodies and the extreme scarcity and isolation of minority

physicians. Medical schools, like many other institutions in

the society, found it both appropriate and necessary to

11

address a problem historically cast in racial terms through

remedial programs employing racial criteria.

Race-sensitive measures were employed in medical-

school admissions, as elsewhere, because they were found

to be necessary, not because of an ignorance of the con

cerns that may inhere in the use of such means, even for

remedial purposes. In programs like that at issue in this

controversy, the relevant concern is not for quotas, for

any slur or stigma against any particular group, for any

corruption of meritocratic principles, or for any singling

out of any particular ethnic group to bear the brunt of

the program. There has been a tendency to inject such

concerns into this matter, but on analysis they prove to be

irrelevant, misleading, or both. The relevant concern is for

a potential for the arousal of racial awareness in a society

that is striving to put behind it past tendencies to view

persons in racial and ethnic terms. The identification of

this concern represents the beginning, rather than the end,

of the requisite analysis. And, on balance, as well as

under all of the controlling authorities, the potential for

the arousal of racial awareness inescapably contained in

programs like that of the Davis medical school, when

weighed against the significant benefits to be achieved,

does not violate the Equal Protection Clause.

State action that arouses racial awareness in circum

stances where the potential for harm is very high and

where the state’s purpose is to inflict injury through such

arousal contravenes the Equal Protection Clause, as this

Court has recognized. Nevertheless, this and other Courts

have repeatedly upheld the utilization of racial criteria

for the purposes of achieving racial diversity in schools

and countering the effects of a legacy of discrimination,

despite the inevitable arousal of racial awareness prompted

by such means. The school desegregation cases, as well as

12

other lines of authority, reflect the ultimate judgment that

the benefits to be had from utilization of truly effective

remedies justify the transient societal costs and the

incidental effects on some whites. There is a distinction

between color-blindness and myopia, a line that has been

kept clear in these cases. 'They are determinative authority

for reversal in the instant case. But the University does

not rest there. The same result follows if resort be had to

other lines of authority.

The standard of strict judicial scrutiny does not apply to

this case. That standard is appropriately applied to racial

classifications aimed at harming discrete and insular minor

ities, to groups historically alienated and denied a voice in

political affairs. To apply stringent scrutiny to measures

intended to aid such groups, and when majoritarian proc

esses are plainly unimpaired, would stand the Equal Pro

tection Clause on its head and lead to an unwarranted, un

justified, and aberrational degree of judicial intervention in

intractable matters of educational policy properly reserved

to the states and to educators.

Begardless of the standard of review or burden of justi

fication, the Davis medical school program comports with

the Equal Protection Clause. The traditional standard of

review properly applies, and the program plainly meets i t ;

there is the most rational relationship between means and

ends. An intermediate standard of review is not warranted

by the circumstances, but the program in any event meets

such a standard. Finally, although strict judicial scrutiny is

wholly inappropriate, the program passes even that bar

rier. The ends of the program are as compelling as imagin

able in our country today. The fit between means and ends

is as tight as possible. There are no effective alternatives.

Unless the ends of the program are to be held illegal or

unless the state is to be left with compelling interests that it

13

is powerless to vindicate, the result below must be reversed

even on the standard least favorable to the University’s

position.

ARGUMENT

Introductory

The outcome of this controversy will decide for future

decades whether blacks, Chicanos and other insular minori

ties are to have meaningful access to higher education and

real opportunities to enter the learned professions, or are

to be penalized indefinitely by the disadvantages flowing

from previous pervasive discrimination. Affirmance of the

judgment below would mark a return to virtually all-white

professional schools. The professions would remain white

enclaves. Reversal would permit continuation of admissions

programs, like the one at Davis, fashioned by educators who

have agreed that “ [t]he greatest single handicap the ethnic

minorities face is their underrepresentation in the profes

sions of the nation.” The Carnegie Commission on Higher

Education, A Chance to Learn, 12-13 (1970). It would also

allow educators, rather than lawyers and judges, to deal

with intractable matters of educational policy.

Today, only a race-conscious plan for minority admissions

will permit qualified applicants from disadvantaged minori

ties to attend medical schools, law schools and other institu

tions of higher learning in sufficient numbers to enhance

the quality of the education of all students; to broaden

the professions and increase their services to the entire

community; to destroy pernicious stereotypes; and to

demonstrate to the young that educational opportunities

and rewarding careers are truly open regardless of ethnic

origin. Applicants for admission to professional schools

14

greatly outnumber the available places. Until their cultural

isolation is relieved by full participation in all phases of

society, historically alienated minorities would be screened

out by all racially blind methods of selection. There is,

literally, no substitute for the use of race as a factor in

admissions if professional schools are to admit more than

an isolated few applicants from minority groups long sub

jected to hostile and pervasive discrimination.

A fundamental error of the court below lies in its failure

to recognize this necessity. The court did not deny the great

values of the goals of the medical school faculty. It opined,

however, upon sheer speculation, without citation to evi

dence in or studies outside the record, that significant

numbers of minority medical students eould be enrolled by

reliance on “neutral” alternatives, such as recruitment.

Although the University believes that the California court

exceeded the judicial function in substituting its judgment

for that of educators and for that reason alone must be

reversed, its error was compounded by the fact that it was

wrong. Its “alternatives” are illusory. None of them would

lead to significant minority participation. A quixotic at

tempt to employ some of them would grievously harm

educational values considered fundamental by most facul

ties.

Most professional schools in this country today utilize

special-admissions programs. Since the governing boards

of these schools are not given to the employment of

ineffective means, it is no accident that these programs

employ racial criteria. These entities will recognize (as

they have in the past) the fallacies and false hopes in the

admissions policies espoused by the court below. Most pro

fessional schools predictably will be unwilling to engage

in subterfuge and, in the event of an affirmance, would

simply shut down their special-admissions programs. They

15

would be consigned to watching the number of minority

students in their schools dwindle to disappearance and to

hoping and waiting, much as the country hoped and waited

in the 1920’s and 1930’s, for the end of an era in which the

tyranny of abstract legal formulas bars gravely needed

reform efforts undertaken by entities other than the judici

ary.

Some faculties, reading between the lines of the opinion

below or of an affirmance at this Court and in a desperate

hope to preserve significant minority enrollment, might

resort to sub rosa race lines. This would represent sub

silentio acknowledgment of the by now obvious point that a

problem historically cast in racial and ethnic terms admits

only of solutions unavoidably defined in racial and ethnic

terms. However attractive this course might appear at

first, ultimately it would lead to three grave difficulties.

First, perhaps even the most ardent exponents of

realpolitik would agree that whatever the case for hypoc

risy and disingenuousness in other arenas, it may be intol

erable in a university. Second, the racial criteria at issue

here, unlike those that harm the discrete, powerless minori

ties, are realistically susceptible to alteration or elimination

by majoritarian or representative processes. Surreptitious

resort to racial and ethnic criteria would impair the ability

of these processes to control any abuses. Finally, an effort

to disguise purpose undoubtedly would encumber the judi

cial process, but ultimately it would not totally frustrate

judicial scrutiny. If deliberate reliance in any form on

factors of race or ethnicity as a means for dealing with

past or present exclusion of minorities from professional

schools and the professions constitutes invidious discrim

ination, as the court below held, then a program purportedly

neutral on its face but in fact applied for the purpose of

obtaining color-conscious results could in time be demon-

16

strated to be illegal. Accordingly, an effort to achieve the

ends of the Davis program while disclaiming, with a know

ing wink, reliance on race very likely would bring grief to a

faculty that made the attempt. It would certainly bring to

the courts a continuous burden of supervision of the admis

sions processes of the nation’s professional schools.

Despite the tenor of the opinion below, it simply is not

true that a judicial striking down of the challenged pro

gram won’t make much of a difference, that faculties nation

wide would find effective alternatives, and that significant

minority participation in professional education for the

foreseeable future would be likely to continue. There is no

such easy way out, notwithstanding the opinion of the court

below. The fundamental importance of this ease calls for

a clear-eyed recognition of what is really at stake and for

a resistance to the inclination to blink, or worse to mask,

the consequences of an affirmance.

The faculty of the Davis medical school, like this Court,

“was rightly concerned that childhood deficiencies in

the education and background of minority citizens, re

sulting from forces beyond their control, not be

allowed to work a cumulative and invidious burden

on such citizens for the remainder of their lives.”

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 806

(1973).

The faculty sought to shorten the distance between the con

cept of formal equality of opportunity and the actuality of

real inequality of opportunity. Whether such voluntary,

remedial efforts will be permitted to continue, and whether

the doors, so recently opened, to the traditionally white pro

fessional schools are in fact to remain open to historically

excluded minorities, will turn on the result in this case.

The country is well-served by programs like the one at

the Davis medical school. They are positive proof to those

17

so long excluded from positions of responsibility that all

citizens are truly to be offered a chance to perform in

professional roles. Without such programs, the promise of

Brown v. Board of Education rings hollow in professional

education, for our time and, perhaps, for a very long time

to come.

I

The Legacy of Pervasive Racial Discrimination in Education,

Medicine and Beyond Burdens Discrete and insular Minorities,

as Well as the Larger Society. The Effects of Such Discrimina

tion Can Not Be Undone by Mere Reliance on Formulas of

Formal Equality. Having Witnessed the Failure of Such For

mulas, Responsible Educational and Professional Authorities

Have Recognized the Necessity of Employing Racially-Con-

scious Means to Achieve True Educational Opportunity and

the Benefits of a Racially Diverse Student Body and Profession.

A. THE LEG A CY OF DISCRIMINATION CONTINUES TO BURDEN AND TO

OBSTRUCT THE ADVANCEMENT OF DISCRETE AND INSULAR RACIAL

MINORITIES.

1. The delay in implementing Brown v. Board of Education is but one of the

elements of the experience of growing up as a member of a racial minority

in this country.

Students applying for admission to medical school in

1970, the first year of operation of the Davis Task Force

program, would in ordinary course have begun elementary

school in 1954, the year this Court decided Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 TT.S. 483. Brown eloquently expressed the

goal of educational opportunity unimpaired by the effects of

racial discrimination, but implementation of the commit

ment expressed in Brown has taken years and is even today

not complete. A rectification of such magnitude cannot occur

overnight, especially when it encounters resistance at the

local level. Minority students entering medical schools in

the 1970’s are from the generation of minority students who

have seen the hope but not the promise of Brown. This

18

Court spoke to the delay in implementing Brown at about

the time the Davis program got under way:

“Over the 16 years sinee Brown II, many difficulties

were encountered in implementation of the basic con

stitutional requirement that the State not discriminate

between public school children on the basis of their

race. Nothing in our national experience prior to 1955

prepared anyone for dealing with changes and adjust

ments of the magnitude and complexity encountered

since then. Deliberate resistance of some to the Court’s

mandates has impeded the good-faith efforts of others

to bring school systems into compliance. The detail and

nature of these dilatory tactics have been noted fre

quently by this Court and other courts.” Swann v.

Charlotte-Mechlenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S.

1,13 (1971).

Still more recent cases on this Court’s docket, from cities

of the North and West as well as the South, testify to the

continued prevalence of serious obstacles to the achievement

of desegregated schools. And for every case which reaches

this Court there are hundreds, or thousands, of similar

problems in other places which are faced only administra

tively or by lower courts or indeed not litigated at all. More

over, even a state such as California, which is one of the

most open societies in the country, cannot claim to have

been (or to be) free of discrimination on the basis of race.

The California school desegregation cases alone contradict

any such assertion,8 and they again represent only the tip

of the iceberg. But California could not, in any event, in

sulate itself from the effects of segregated education else-

8. See, e.g., Crawford v. Board of Education of the City of Los

Angeles, 17 C.3d 280, 130 Cal.Rptr. 724, 551 P.2d 28 (1976); Soria

v. Oxnard School District, 386 F. Snpp. 539 (C.D. Cal. 1974);

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 311 F. Supp. 501

(C.D. Cal. 1970). See generally, C. Wollenberg, A nn D eliberate

S p e e d : Segregation and E xclusion in Calieornia’s S chools,

1855-1975 (1976).

19

where in the nation. It is not simply that persons from other

states have a constitutional right to become California resi

dents if they wish. See, e.g., Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S.

618 (1969). Many have actually exercised that right,

including particularly substantial numbers of minorities

from the South, the major cities of the North, and elsewhere.

For example, 41% of American-born blacks residing in Cali

fornia in 1970 were born in the South—more than were

born in California® These individuals are residents of the

state, but to the extent that they have endured segregated

education elsewhere, they cannot escape its consequences

merely by emigrating to California.

Ultimately, however, the legacy of past discrimination is

not limited to the harmful effects of segregated education.

Unequal education, however significant and immediately

relevant, is but one facet of a much more pervasive pattern

of discrimination against minority persons in this country:

“Kacial generalizations are pervasive and have tradi

tionally operated in the same direction—to the disad

vantage of members of the minority group. A person

who is denied one opportunity because he or she is

short or overweight will find other opportunities, for

in our society height and weight do not often serve as

the bases for generalizations determining who will re

ceive benefits. By contrast, at least until very recently,

a black was not denied an opportunity because of his or

her race, but denied virtually all desirable opportuni

ties. As door after door is shut in one’s face, the indi

vidual acts of discrimination combine into a systematic

and grossly inequitable frustration of opportunity.”10

9. The figures are essentially the same for the age-group most

eligible for medical school (20-24 years old). U.S. Bureau of the

Census, Dep’t of Commerce, Pub. No. PC(1)-DC6, U nited S tates

Cen su s oe P o pu la tio n : 1970, Detailed Characteristics, California,

Section 1, Table 140 (1973).

10. Brest, Foreword: In Defense of the Antidiscrimination

Principle, 90 Harv.L.Rev. 1, 10 (1976) (italics original).

20

Growing up black, Chicano, Asian, or Indian in America

is itself an experience which transcends the particular fact

of segregated education. The history and culture of each

of these groups is different, and thus to some extent is the

precise nature of the experience. But these groups all con

stitute

“ethnic minorities separated not only by substantially

different attitudes and experiences but by continued

educational disadvantages. [They] also share a dis

advantage resulting from circumstances of their par

ticular racial mixture. More of their members are

visibly distinguishable from the dominant majority

by their darker skin and certain related physical fea

tures. The prejudice of whites against people with

darker skins has a long history. It is expressed in

negative attitudes that encourage the preservation

of this psychological distance between [these] ethnic

groups and whites that their cultural differences had

already created. Even efforts by members of these

minorities to merge with the majority have been de

terred by this color prejudice.

“Each of [these] minority groups has been separated

and alienated within the United States. . . ,mi

11. C. Odegaard, M in orities in M e d ic in e : F rom R eceptive

P assivity to P ositive A ction 1966-76 at 8 (1977) [hereinafter

cited as M in orities in Med icin e] . The quoted passage speaks orig

inally of American Indians, Black Americans, Mexican Americans,

and Puerto Ricans, hut its reasoning clearly applies fully to Asian

Americans. The Court’s own cases of eourse provide a documentary

record of the history of discrimination against the groups included

in the Davis program. See, e.g., B o llin g v. Sharpe, 847 IJ.S. 497

(1954) ; H ernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954); O yam a v. Cali

fo rn ia , 332 U.S. 633 (1948); M orton v. M ancari, 417 U.S. 535

(1974) . Because they share a history of uninterrupted discrimina

tion and near-total alienation based in substantial part on color,

these groups differ from other ethnic minorities. These groups are

referred to in this brief as racial minorities or as minorities. The

term “race” is vague and imprecise if not inaccurate, but as the

court below observed: “Unfortunately lexicon is imprecise and until

an improved taxonomy emerges we shall probably be compelled to

discuss problems such as that before us in terms of race.” 18 C.3d

at 46.

21

In other words, including those of this Court, to grow up

a member of one of these groups is to be of a discrete and

insular minority in this country.12

The difficulties inherent in growing up as a member of

a discrete and insular minority are encountered throughout

society. The problem is societal in nature. This case deals

with one aspect of the broader societal problem—medical

schools and medicine—and with the efforts of a medical

school to address those facets of the larger problem which

fall within its appointed role. Because this case on its

facts involves medical school admissions, we turn now to

the legacy of discrimination in the context of medicine.

2. The most significant fact about doctors from minority groups is that they

are so few, and the most significant fact about health care for such groups

is that it is scarce and inferior.

The ramifications of societal discrimination for minority

doctors extend to every aspect of their professional lives.

Black doctors have been isolated and constricted by denial

of opportunities in their training, their practice, and their

professional status.18 Restrictions on the access of black

12. The difference between growing up as a member of the

majority and growing up as a member of a racial minority can be

illustrated by comparing respondent’s life experiences with those

he would have encountered if black. Respondent was bom in the

midwest (R. 112). Subsequently he moved with his parents to

Florida, where he attended Coral Gables High School in Dade

County ( Ib id .) . In moving to Florida, his parents had the comfort

of knowing that respondent would be eligible for the best public

high school education available. That would not have been true if

respondent had been black, for in the years in which respondent

attended high school, Florida practiced de ju re discrimination and

“complete actual segregation of the races, both as to teachers and

pupils, still prevailed in the public schools of [Dade] County.”

Gibson v. B oard o f P u b lic In s tru c tio n o f D ade C oun ty , F lorida,

272 F.2d 763, 766 (CA5 1959).

13. Because extensive documentation is available only for

blacks, the discussion in this part of the brief focuses on that

minority group. What data are available suggest that the picture

for other minorities is not essentially different. See text at and

n. 22, in fra .

22

medical graduates to advanced clinical training and to spe

cialty board certification have resulted in fewer specialists

among black physicians than among white.14 The relative

paucity of blacks on the faculties of American medical

schools exceeds even the degree of their scarcity in the

profession.15 Racial barriers have often obstructed hospital

appointments necessary to effective practice.16 Such appoint

ments, continuing education, valuable professional contacts,

and even specialty certification have turned upon member

ship in the state or local medical society.17 Yet it was not

until 1968 that the American Medical Association prohibited

racial bars to membership in its state and local affiliates.18

And in 1971 the House of Delegates of that organization

found it necessary to adopt a resolution threatening sus

pension of local units which continued to practice racial

exclusion.19

14. M. Seham, B lacks and A merican Medical Care 57, 71

(1973) [hereinafter cited as B lacks and Medical Care] ; Haynes,

D istr ib u tio n o f B lack P hysic ians in the U n ited S ta tes , 210 j .a .m .a .

93, 95 (1969); Melton, H ea lth M anpow er and N egro H e a lth : T he

N egro P hysic ian , 43 J.Med.Educ. 798, 806 (1968); Johnson, H is

to ry o f the E d u ca tio n o f N egro P hysicians, 42 J .M ed .E duc. 439,

442-43 (1967).

15. D atagram : E th n ic G roup M em bers on U .S. M edical F acu l

ties, 51 J.Med.Educ. 69, 70 (1976). And 36% of the black members

of medical faculties serve at Howard University, Meharry Medical

College, and the University of Puerto Rico. Id .

16. B lacks and M edical Care, 71-77.

17. Id . at 75; Melton, supra note 14, at 806.

18. B lacks and Medical Care, 74.

19. Id . at 81.

The presence or absence of minority members in medical societies

can also make a difference in the way those organizations address

important questions of health care. Thus, for example, it would be

not merely insensitive, but unthinkable, for the head of a medical

society with substantial numbers of minority members to make the

following public statement, attributed to the president of the Ameri

can Medical Association in 1968:

“ [The president] said that the medical profession should

not be blamed for this group’s [“people in big-city ghettos”]

23

The data could be multiplied. But the most important

fact about minority doctors is that there are so few of them.

The 1970 census reported 6,002 black physicians out of

279,658 physicians in the United States, or 2.1% of the

total.20 The reported ratio of black physicians to blacks

is far lower than the physician/non-physician ratio for the

nation at large. For blacks, that ratio is 1/4248. For the

population generally, it is 1/649. The shortage of black

physicians is most acute in the deep South, where in some

states the physician/non-physician ratios among blacks

has been reported to be in the range of 1/15,000 to 1/20,000.21

The picture for Mexican Americans and American Indians

is almost certainly worse yet.22

The scarcity and inferior status of minority physicians

is mirrored by the scarcity and inferiority of health care

services for minorities. The distressing status of health

care for minorities is amply chronicled elsewhere:

“Every measure of health we have shows striking

differences between the white and nonwhite population,

and this gap is becoming a chasm in spite of all the

advanced technical resources in our country. Blacks

in our country do not live as long as whites; black

mothers die in childbirth more often than whites and

inability or lack of willingness to educate themselves, for the

conditions in which they live, for the lack of transportation to

allow them to visit existing health care institutions, and for

their reluctance to see a physician in a free clinic until their

condition is beyond help.” AMA News, April 8, 1968, p. 8.

20. U.S. Bureau of Health Manpower, Dep’t of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare, Pub. No. (HRA) 76-22, M inorities and W om en

in the H ea lth F ields: A p p lica n ts , S tu d e n ts and W orkers at 9

(1975).

21. Thompson, C urbing the B lack P hysic ian M anpow er S h o r t

age, 49 J .M ed.E dttc. 944, 945-46 (1974).

22. The data are very sparse. See M in orities in Medicine 33;

Applewhite, Blochs in P ub lic H ea lth , 66 J.N.M.A. 505, 506 (1974) ;

T h e N ew Y ork T im es , June 6, 1974, at 36, col. 5 (letter from

William E. Cadbury, Jr., Executive Director, National Medical

Fellowships, Ine.).

24

their babies are more likely to be premature, stillborn,

or dead in their first year of life. Blacks visit doctors

less frequently than whites and when they go to the

hospital they are more likely than whites to need a

longer stay, which reflects the fact that they have been

medically neglected. In almost every category of illness,

the morbidity and death rates among blacks are higher

than among whites. Blacks suffer proportionately more

acute and chronic illnesses. In 1960 the death rate for

blacks from pulmonary tuberculosis was roughly four

times that of the white population, and the number

of active cases among blacks was three times as high.

According to the Public Health Service data, in 1962

the incidence of reported syphilis among blacks was

ten times greater than among whites and the death

rate was about four times as high. Hypertension, dia

betes, cirrhosis of the liver, and malignant neoplasms

also affect blacks more than they do whites. . . .

“Black death rates relating to such communicable

diseases as whooping cough, meningitis, measles, diph

theria, and scarlet fever are particularly high. This,

of course, is because frequently black children have

not been immunized. And in almost every category of

causes of deaths for infants, the rate for blacks is 39.5

per 1,000 live births, almost twice as high as for whites

(20.8). . . . The difference cannot be attributed to

income alone, since when the death rates of infants

from low-income families are analyzed, race still makes

the difference. The infant death rate for families whose

income is less than $3,000 is 27.3 per 1,000 live births

for white families, and 42.5 for blacks; when family

income is between $3,000 and $4,900, the rate for whites

is 22.1, and 46.8 for blacks.” 23

To suggest that the paucity of minority physicians is

reflected in poor medical care for minorities is not to sug

gest that only blacks can treat blacks or that only Asians

23. B lacks and M edical Care 9-11.

25

should treat Asians or that only Chicanos should be trained

to treat Chicanos. It is simply to recognize the reality that

many forces, including economics, idealism, and continuing

patterns of discrimination, commonly bring minority phy

sicians back into minority communities, where the shortage

of health services is most severe, and that as a society we

have refrained from compelling other physicians to locate

their practices in those areas.

“If you could insist, for instance, that the people

who come into the professional schools make a contract

for 10 or 20 year terms to serve low-income people,

then you would have no need to be racially selective.

But the fact of the matter is you could neither make

nor enforce such a contract. Therefore, one must be

more explicit in favoring those people who, in fact,

are more likely to make a commitment to serve in that

sector of the community that has the most acute medi

cal and public health needs for a long term. Viewed

from that quasi-contractual perspective, independently

of the race of the people involved, then I think you can

have the proper focus on what needs to be done in the

admission policies. Operating on that theory of a con

tract in its social sense, I think it is safe to say that

there is an overwhelming disproportion of probability

that black people will return by necessity of culture and

custom to the black community, to use their talents. It

is not a philosophical position, it is a statistical posi

tion. It is justified not on the basis of the theory of

differences of color, but on the practical necessities of

the deprivation of peculiar enclaves within our society

that we need to be concerned with a new racially-

selective education.”24

24 J enkins, T he H ow ard P rofessional School in a N ew Social

P erspective , 62 J.N.M.A. 167 (1970). There are data showing that

doctors of non-racial ethnic groups (Anglo-Saxon, Irish, Italian,

Jewish, and Polish) tend to “specialize in serving their fellow-

ethnics.” Lieberson, E th n ic Groups and the Practice o f M edicine,

23 Am. Soo. Rev. 542, 546 (1958). There is also a strikingly high

26

B. UNTIL THE ADVENT OF SPECIAL-ADMISSIONS PROGRAMS, MEDICAL

SCHOOLS, EXCEPT FOR TWO TRADITIONALLY BLACK, WERE WHITE

ISLANDS IN A MULTI-RACIAL SOCIETY.

1. Formal barriers against minority participation in medical schools did not

fall until very recently and, by itself, the elimination of those restraints did

not produce racial diversity. Indeed, mere reliance on formulas of formal

equality raised the threat of retrogression, rather than the prospect of

progress.

The beginning of this decade witnessed the advent of

minority special-admissions programs. Before then, medical

schools in the United States had always been white islands

in a multi-racial society, except for traditionally black

Howard University and Meharry Medical College. For the

longest portion of our history after the end of slavery,

minorities were excluded from many, if not most, medical

schools by law or by official school policies.25 The final col

lapse of state de jure barriers was unquestionably mandated