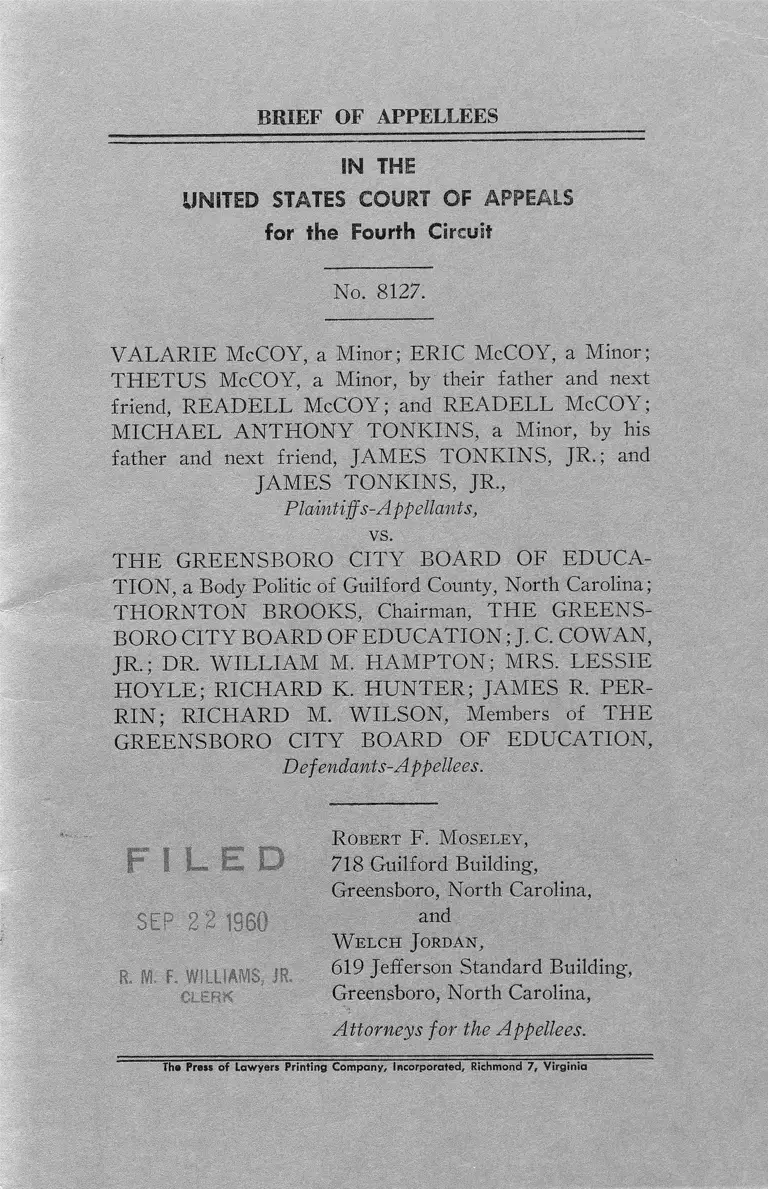

McCoy v. The Greensboro City Board of Education Brief of Appellees

Public Court Documents

September 22, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCoy v. The Greensboro City Board of Education Brief of Appellees, 1960. b7706778-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d80bd7ea-ffbe-4e11-912f-5b4aa7495f43/mccoy-v-the-greensboro-city-board-of-education-brief-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 8127.

V A L A R IE M cCOY, a Minor; ERIC M cCOY, a Minor;

TH ETU S M cCOY, a Minor, by their father and next

friend, R E A D E LL M cCO Y; and R E A D E LL M cCO Y;

M IC H A EL A N T H O N Y TO N K IN S, a Minor, by his

father and next friend, JAM ES TON KIN S, JR.; and

JAM ES TO N K IN S, JR.,

Plaintiffs-A ppellants,

vs.

TH E GREENSBORO C ITY BO ARD OF ED U CA

TION , a Body Politic o f Guilford County, North Carolina;

TH O RN TO N BROOKS, Chairman, T H E GREENS

BORO CITY BO ARD OF E D U C A T IO N ; J. C. COW AN,

JR.; DR. W IL L IA M M. H A M P T O N ; MRS. LESSIE

H O Y L E ; RICH AR D K. H U N T E R ; JAMES R. PER

R IN ; RICH AR D M. W ILSO N , Members of TH E

GREENSBORO C ITY BO ARD OF EDU CATION ,

D ef endants-A ppellees.

F I L E D

SEP 2 2 I960

R. M. F. WILLIAMS, JR.

■CLERK

R o b e r t F. M o s e l e y ,

718 Guilford Building,

Greensboro, North Carolina,

and

W e l c h J o r d a n ,

619 Jefferson Standard Building,

Greensboro, North Carolina,

Attorneys for the Appellees.

The Press of Lawyers Printing Company, Incorporated, Richmond 7, Virginia

IN D E X TO BRIEF

Page No.

Statement of the Case ....................................................... 2

Questions Involved .............................................................. 2

Supplemental Statement o f F a cts .............................. 3

(1 ) The Board’s Compliance with the Constitu

tional Doctrines Enunciated in the Brown Opinions 3

(2 ) Actions of the Board upon the Reassign

ment Applications o f the Four Children W ho are the

Minor Plaintiffs in This Case ...................................... 9

The McCoy Children .................. 9

The Tonkins Child ..............................................-.....- 11

(3 ) Events Following the Consolidation of the

Pearson Street Branch of the Washington School

with the Caldwell S chool........................................ 12

Argument ..........................................................................----- 14

(1 ) Since at the Time of the Hearing o f the

Board’s Motion for Summary Judgment It Appeared

that the Minor Plaintiff School Children Had Been

Assigned, Insofar as Was Possible, to the School in

Which They Had Originally sought to be Enrolled,

the District Judge Correctly Held that the Questions

Presented by the Plaintiffs’ Complaint Had Become

Moot and that the Complaint Should be Dismissed .. 14

(2 ) The District Judge Was Not in Error in De

clining to Permit the Plaintiffs to File Their Supple

mental Complaint..................................................... -....... 17

Conclusion ............................................................................. 27

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Page No.

Allen v. County School Board o f Prince Edwards

County, Va., 4 Cir., 1959, 266 F. 2d 507 .............. 20, 22

Arp v. United States, 10 Cir., 1957, 244 F. 2d 571, cert.

den., 355 U. S. 826, 78 S. Ct. 34, 2 L. Ed. 2d 4 0 ........ 25

Avery v. Wichita Falls, 5 Cir., 1957, 241 F. 2d 230 .. 20, 23

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct.

686, 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954) ; second opinion, 349 U. S.

294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083 (1955) .... 3, 5, 18, 22

Briggs v. Elliott, D.C.E.D., S. C., 1955, 132 F. Supp.

776 ...................................................................................... 23

Carson v. Board of Education, 4 Cir., 1955, 227 F. 2d

789 ...................................................................................... 15

Carson v. Warlick, 4 Cir., 1956, 238 F. 2d 724

15, 17, 20, 24

Cherry v. Morgan, 5 Cir., 1959, 267 F. 2d 305 ..... 16, 26

Covington v. Edwards, 4 Cir., 1959, 264 F. 2d 780,

cert, den., 361 U. S. 840, 80 S. Ct. 61, 4 L. Ed. 2d

78 ......................................................................... 15, 19, 20

Dixi-Cola Laboratories v. Coca-Cola Co., 4 Cir., 1944,

146 F. 2d 43 ................................................................... 26

Farley v. Turner (No. 8054, 4 Cir., June 28, 1960) ...... 22

First Nat. Bank in West Union, W . Va,, v. American

Surety Co., 4 Cir., 1945, 148 F. 2d 654 ....................... 25

General Bronze Corp. v. Cupples Products Corp.,

D.C.E.D., Mo., 1949, 9 F.R.D. 269 .......................... 27

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 5 Cir., 1957,

246 F. 2d 913, second appeal, 1959, 272 F. 2d

763 ............. ................................................................. 20, 21

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 5 Cir., 1958,

258 F. 2d 730 20

Page No.

Holt v. Board of Education, 4 Cir., 1959, 265 F. 2d

95, cert, den, 361 U. S. 818, 80 S. Ct. 59, 4 L. Ed.

2d 63 .................................................................. 15, 20, 22

In Re Applications for Reassignment, 247 N. C. 413,

101 S.E. 2d 359 (1958) ........................................... ----- 8

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 5 C ir, 1960,

277 F. 2d 370 ..................................................... 20, 21, 22

Martinez v. Maverick County Water Control, etc.

District, 5 C ir, 1955, 219 F. 2d 666 ........................... 19

Missouri-Kansas-Texas R. Co. v. Randolph, 8 C ir,

1950, 182 F. 2d 996 ......................................................... 25

School Board of City o f Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen,

4 C ir, 1956, 240 F. 2d 5 9 .............................................. 20

United States v. Alaska Steamship C o, 253 U. S. 113,

40 S. Ct. 448, 64 L. Ed. 808 (1920) ........................... 16

United States v. Russell, 1 C ir, 1957, 241 F. 2d 879 .... 26

United States v. W . T. Grant C o , 345 U. S. 629, 73

S. Ct. 894, 97 L. Ed. 1303 (1953) ............................... 16

Statutes

North Carolina Assignment and Enrollment of Pupils

Act (G. S. 115-176 through 115-179) .... 5, 14, 17, 18

Florida Pupil Assignment Act ................................ .......- 22

Rules

Rule 23 (a ) (3 ), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure...... . 19

Greensboro City Board o f Education Rules and Regu

lations For the Reassignment of Pupils and Pro

cedure With Respect Thereto ...................................... 5

T reatises

3 Moore’s Federal Practice, 2nd Edition, Sec. 23.11

(5 ) , page 3472 19

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 8127.

V A L A R IE McCOY, a Minor; ERIC McCOY, a Minor;

TH ETU S McCOY, a Minor, by their father and next

friend, R E A D E L L M cCO Y; and RE A D E LL M cCO Y;

M IC H A EL A N T H O N Y TO N K IN S, a Minor, by his

father and next friend, JAMES TON KIN S, JR.; and

JAM ES TO N K IN S, JR.,

Plaintiffs-A ppellants,

vs.

T H E GREENSBORO C ITY BOARD OF ED U CA

TION , a Body Politic o f Guilford County, North Carolina;

TH O R N TO N BROOKS, Chairman, TH E GREENS

BORO C ITY BO ARD OF E D U C A T IO N ; J. C. COW AN,

JR.; DR. W IL L IA M M. H A M P T O N ; MRS. LESSIE

H O Y L E ; RICH ARD K. H U N TE R ; JAMES R. PER

R IN ; RICH ARD M. W ILSO N , Members of TH E

GREENSBORO CITY BO ARD OF ED U CATION ,

Defendants-Appellees,

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina, Greensboro Division

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

2

STA TE M E N T OF T H E CASE

The procedural steps which have been taken in this case

are correctly summarized in the Statement o f the Case

set forth in appellants’ brief. However, we do not concede

the accuracy of some of the facts which are recounted

in this portion o f their brief; for this reason we set forth

below a Supplemental Statement o f Facts. Moreover, we

disagree with the plaintiffs’ statement of the question pre

sented by this appeal. W e submit that there are, in fact, two

separate and distinct questions involved.

QU ESTION S IN V O LVE D

(1 ) Did the District Court properly grant the de

fendants’ motion for summary judgment dismissing

the plaintiffs’ complaint when there was an uncon

troverted showing that the relief sought therein by

the individual plaintiffs had been granted as to three

of the children involved and could not, as a matter

o f fact and law, be granted to the other child, the

Court holding that the cause o f action asserted in the

complaint had become moot ?

(2 ) Did the District Court properly decline to

permit the plaintiffs to file a supplemental complaint,

in which the plaintiffs sought, by way o f class relief,

to have the Court order into effect a broad-scale com

pulsory plan of integration of the races in the Greens

boro, North Carolina, public school system, it clearly

appearing that desegregation o f the Greensboro public

schools had been and was being pursued in an orderly

manner with all deliberate speed?

3

SU PPLE M E N TA L STA TE M E N T OF FACTS

In an effort to achieve clarity through chronological

recitation of the facts, we divide our Supplemental State

ment o f Facts into three parts: (1 ) the history of the

activities of The Greensboro City Board o f Education

(hereinafter referred to as the Board) responsive to the

decisions o f the Supreme Court of the United States in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 74 S. Ct.

686, 98 L. Ed. 873 (1954); and, second opinion, 349 U. S.

294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083 (1955); (2 ) the

relevant facts concerning the Board’s actions upon the

applications for reassignment o f the four public school

children who are the minor plaintiffs in this case; and

(3 ) events following consolidation of the Pearson Street

Branch o f the Washington School with the Caldwell

School.

(1 ) T H E B O A R D ’S CO M PLIAN CE W IT H TH E

C O N STITU TIO N A L DOCTRIN ES EN U N

CIATED IN T H E BROW N OPINIONS.

On May 18, 1954, the day after the first decision in the

Brown case was made public by the Supreme Court o f the

United States, the Board (then known as the Board o f

Trustees o f the Greensboro City Administrative Unit)

adopted and had spread upon its minutes the following

resolution:

“ RESOLU TION W IT H RESPECT TO DECI

SION OF TH E U N ITED STATES SUPREM E

COURT BAN N IN G SEGREGATION IN TH E

PUBLIC SCHOOLS

“ W H E R E A S, the Supreme Court of the United

4

States has rendered a decision to the effect that the

segregation o f pupils in public schools solely upon

the basis o f differences in race violates the Fourteenth

Admendment to the Constitution o f the United States,

and is thus invalid and unlawful; and

“ W H E R E A S, the Board of Trustees o f the Greens

boro City Administrative Unit, the governing body

of the public schools o f the Greater Greensboro School

District, recognizes that the decision of the Court

constitutes the law of the land and is binding upon the

Board;

“ NOW , TH EREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, That

the Board instruct the Superintendent to study and re

port to the Board regarding the ways and means for

complying with the Court’s decision.

“ This the 18th day o f May, 1954.” (App. 22a-23a)

It is believed that this prompt action on the part o f the

Greensboro Board (which received national newspaper

coverage at the time) was the first public acknowledgment

by a southern school board of the constitutional necessity

o f eliminating racial discrimination in the public schools

o f the southern states, which had hitherto for a period of

about ninety years rigidly enforced a system of bi-racial

separation of the white and Negro races in their public

school systems. As a matter o f fact, in North Carolina

for generations there had been a triple and total separation

o f the public schools into those provided for whites,

Negroes and Indians, respectively.

The Board and its Superintendent were not long in im

plementing the resolution of May 18, 1954. All references

to “ bi-racial organization” were eliminated from the

Board’s handbook for teachers, and the Greensboro schools

5

were thereafter listed alphabetically instead of by race.

Joint meetings of white and Negro school personnel began

to be held regularly ( App. 24a). The Superintendent began

a study o f available literature relating to the problem of

good faith compliance with the Brozmi decision.

Following the enactment in 1955 by the North Carolina

General Assembly of the Assignment and Enrollment o f

Pupils Act (Chapter 366 o f the Session Laws of 1955, as

amended by Chapter 7 o f the Session Laws of 1956,

codified as North Carolina General Statutes 115-176

through 115-179)1, representatives o f the Board held a

1 Assignment and Enrollment of Pupils.

§ 115-176. Authority to provide for assignment and enrollment of pupils;

rules and regulations.—Each county and city board o f education is hereby

authorized and directed to- provide for the assignment to a public school of

each child residing within the administrative unit who is qualified under the

laws of this State for admission to a public school. Except as otherwise

provided in this article, the authority of each board of education in the

matter o f assignment of children to the public schools shall be full and

complete, and its decision as to the assignment o f any child to any school

shall be final. A child residing in one administrative unit may be assigned

either with or without the payment of tuition to- a public school located

in another administrative unit upon such terms and conditions as may be

agreed in writing between the boards of education of the administrative

units involved and entered upon the official records of such boards. No

child shall be enrolled in or permitted to attend any public school other

than the public school to which the child has been assigned by the appropriate

board o f education. In exercising the authority conferred by this section, each

county and city board of education shall make assignments of pupils to public

schools so as to provide for the orderly and efficient administration of the public

schools, and provide for the effective instruction, health, safety, and general

welfare of the pupils. Each board of education may ado-p-t such reasonable

rules and regulations as in the opinion of the board are necessary in the

administration of this article.

§ 115-177. Methods o f giving notice in making assignments o f pupils.—

In exercising the authority conferred by § 115-176, each county or city

board o f education may, in making assignments of pupils, give individual

written notice of assignment, on each pupil’s report card or by written notice

by any other feasible means, to the parent or guardian of each child or

6

number of meetings with the representatives o f the Boards

o f Education of the two other then larger cities o f North

Carolina (namely, Charlotte and Winston-Salem) for the

purpose o f deciding how the complex sociological problem

o f compliance with the Brown decision could be constitu

tionally met without a complete disruption of public school

education in these cities. Thereafter, and on May 21, 1957,

the Board adopted a resolution relating to rules and regu

lations for the reassignment o f pupils and procedure with

respect thereto (set out in full as Exhibit “ A ” attached

to the Board’s answer to the plaintiffs’ complaint, App.

30a-32a). As the result of widespread publicity given the

Board’s action in adopting the resolution of May 21, 1957

(through newspapers, radio, television and by word of

mouth), early in the summer o f 1957 the Board received

applications for the reassignment of nine Negro pupils

to public schools theretofore attended only by white pupils.

One of these applications for reassignment was disallowed

because the Board had no authority to assign any pupil to

the person standing in loco parentis to the child, or may give notice of

assignment of groups or categories of pupils by publication at least two

times in some newspaper having general circulation in the administrative unit.

§ 115-178. Application for reassignment; notice of disapproval; hearing before

board.— The parent or guardian o f any child, or the person standing in loco

parentis to any child, who is dissatisfied with the assignment made by a

board of education may, within ten (10) days after notification o f the

assignment, or the last publication thereof, apply in writing to the board o-f

education for the reassignment o f the child to a different public school.

Application for reassignment shall be made on forms prescribed by the board

o f education pursuant to rules and regulations adopted by the board of

education. I f the application for reassignment is disapproved, the board of

education shall give notice to the applicant by registered mail, and the

applicant may within five (5 ) days after receipt of such notice apply to

the board for a hearing, and shall be entited to a prompt and fair hearing

on the question o f reassignment of such child to a different school. A

majority of the board shall be a quorum for the purpose of holding such

hearing and passing upon application for reassignment, and the decision of

a majority o f the members present at the hearing shall be the decision o f the

7

the school to which this assignment had been requested

(the school being one not operated by the Board), one

application was withdrawn, one was denied, and the re

maining six were granted (App. 25a-26a). When the

Greensboro public schools opened on September 3, 1957,

the school system began operation upon a non-segregated

basis, which non-segregated operation is now in its fourth

year in Greensboro.

The action o f the Board in taking these steps to eliminate

racial discrimination in the assignment o f pupils to the

public schools of Greensboro was far from, receiving the

unanimous approval o f the people o f Greensboro. On the

board. If, at the hearing, the board shall find that the child is entitled to

be reassigned to such school, or if the board shall find that the reassignment

of the child to such school will be for the best interests of the child, and

will not interfere with the proper administration of the school, or with the

proper instruction of the pupils there enrolled, and will not endanger the

health or safety of the children there enrolled, the board shall direct that the

child be reassigned to and admitted to such school. The board shall render

prompt decision upon the hearing, and notice o f the decision shall be given

to the applicant by registered mail.

§ 115-179. Appeal from decision of board.— Any person aggrieved by the

final order of the county or city board o f education may at any time within

ten (10) days from the date of such order appeal therefrom to the superior

court of the county in which such administrative school unit or some

part thereof is located. Upon such appeal, the matter shall be heard de novo

in the superic-r court before a jury in the same manner as civil actions are

tried and disposed of therein. The record on appeal to- the superior court

shall consist of a true copy o f the application and decision of the board,

duly certified by the secretary of such board. I f the decision of the court

be that the order o f the county or city board of education shall be set

aside, then the court shall enter its order so providing and adjudging that

such child is entitled to attend the school as claimed by the appellant, or such

other school as the court may find such child is entitled to attend, and in

such case such child shall be admitted to such school by the county or city

board of education concerned. From the judgment of the superior court

an appeal may be taken by any interested party or by the board to the

Supreme Court in the same manner as other appeals are taken from judg

ments of such court in civil actions.

8

other hand, a group of Greensboro white citizens filed a

suit in the North Carolina Superior Court in August of

1957 in which they sought to have the Board enjoined from

carrying out or continuing its policies designed and actions

taken to eliminate discrimination based upon race or color

in the assignment o f pupils to the public schools. The

Board retained counsel and defended itself against these

white citizens, and the Board secured favorable decisions

both in the trial court and the Supreme Court of North

Carolina. In Re Applications for Reassignment, 247 N. C.

413, 101 S.E. 2d 359 (1958) (App. 26a).

On May 26, 1959, the Board adopted a resolution con

solidating the Pearson Street Branch of the Washington

School (a school which at that time was attended solely

by pupils o f the Negro race) with the Caldwell School

(a school which at that time was attended solely by pupils

o f the white race), at the same time assigning all o f the

pupils in both schools (with the exception of sixth graders,

who were to be promoted to junior high schools) to the

consolidated Caldwell School for the 1959-1960 school

year (App. 60a-61a).

All reassignments o f both white and Negro children in

the public schools of Greensboro since the adoption of the

Board’s resolution of May 21, 1957, have been handled

under and pursuant to the rules and regulations contained

in that resolution (App. 61a and 93a), each application

being separately considered and acted upon by the Board.

Since the opening of the 1957-1958 school year the public

schools of Greensboro, North Carolina, have been, and

still are, being operated upon a non-segregated basis under

which no child is denied upon the grounds of race or

color the right to attend the public school preferred by

him or his parents.

(2 ) ACTIO N S OF T H E BO ARD UPON T H E RE

ASSIGN M EN T A P PL IC A TIO N S OF T H E

FOU R CH ILDREN W H O A R E T H E M IN OR

PLA IN TIFFS IN TH IS CASE.

The McCoy Children

The original applications for reassignment of the McCoy

children from the Pearson Street Branch of the Washing

ton School to the Caldwell School (App. 65a-70a) each

specified that the reasons for the application were that the

Caldwell School was geographically nearer the home of

the children and possessed physical facilities and extra

curricular activities not available to the children at the

Pearson Street Branch of the Washington School. The

plaintiffs concede that both o f these school buildings are

located upon the same campus or plot of land (App. S a ) ;

hence, the reason for reassignment based upon geographical

convenience would seem to have been nonexistent. While

opinions may have differed as to the comparative excellence,

or lack o f it, o f the physical facilities o f the two schools,

Mr. McCoy merely stated in his affidavit that the Pearson

Street Branch school building was “ smaller than and

inferior to” the Caldwell School building. It was also true

that the pupils in the Pearson Street school building ate

their lunches in their classrooms instead of a cafeteria.

Following consideration of these three applications for

reassignment, they were denied by the Board at a meeting

held on August 11, 1958. After being notified of this action,

Mr. Readell McCoy, the father of the McCoy children,

gave notices of appeal in accordance with the rules of the

Board, and the appeals were duly heard at a regular

meeting of the Board on September 16, 1958. At an

adjourned meeting on the following day each of these

10

appeals was denied (App. 60a). At the hearing o f the

appeals Mr. McCoy and his attorney stated to the Board

that the reassignments were desired so that the McCoy

children “would receive a non-segregated education” (App.

77a).

At a meeting of the Board on May 26, 1959, the Board

adopted the previously mentioned resolution which merged

the Pearson Street Branch of the Washington School

with the Caldwell School, the merger to become effective

with the beginning of the 1959-1960 school year, and the

school thereafter to be known as the Caldwell School.

The effect of the merger was to abolish the Pearson

Street Branch of the Washington School. At the same

time the Board assigned all o f the pupils in both schools

to the Caldwell School for the 1959-1960 school year, this

assignment including the two younger McCoy children.

These assignments were stamped upon the report cards

which were delivered to the pupils on June 5, 1959 (App.

60a) and which came to the attention o f Mr. McCoy (App.

77a). Thetus McCoy completed his sixth grade education

during the 1958-1959 school year while still a pupil at the

Pearson Street Branch, and when he received his report

card on June 5, 1959, it was stamped for assignment to the

Lincoln Junior High School for the 1959-1960 school year,

pursuant to the Board’s assignment of him to the seventh

grade of this junior high school (App. 61a). While Mr.

McCoy may have thought that his two younger children,

Valarie and Eric, would attend a desegregated school at

the Caldwell School for the 1959-1960 school year during

the time in June of 1959 when he could have applied for

the reassignment of them to another school, he admitted

that he knew on June 5, 1959, that his oldest child, Thetus,

had been assigned to the Lincoln Junior High School, a

11

school attended solely by Negro students (App. 78a).

Nevertheless, he took no action seeking reassignment of

the oldest child to any other school, despite the fact that

he could have done so at any time during the period from

June 5 to June 15, 1959.

The Tonkins Child

The Tonkins child became eligible in 1958 to enter the

first grade of a Greensboro public elementary school for

the 1958-1959 school year. In June of 1958 his father

submitted an application upon a reassignment form seek

ing to have the child admitted to the Caldwell School (App.

71a-72a). No action was taken upon this application, because

all assignments o f children to the first grade were handled

on a temporary basis by administrative action o f the Super

intendent, such temporary assignments not being made

until the opening o f the school year (App. 62a). When

school opened on September 3, 1958, Mr. James Tonkins,

Jr., brought his child, Michael Anthony, to the Caldwell

School and requested enrollment of the child in the first

grade. The principal of the school called the Superintendent,

who advised the principal that he (the principal) had no

authority to make a temporary assignment of the child,

and that he should instruct Mr. Tonkins to take the child

to the Pearson Street Branch for enrollment on a temporary

basis (App. 63a). This was done, and on the following

day the Superintendent received an application from Mr.

Tonkins for reassignment of Michael Anthony to the

Caldwell School (App. 73a-75a). This application was duly

considered by the Board at a regular meeting held on

September 16, 1958, at which time the Board denied the

application. Proper notice o f denial of the application was

given to Mr. Tonkins, who promptly filed a notice o f appeal.

12

The appeal was heard by the Board on October 21, 1958,

after which the Board denied the appeal, due notice being

given to Mr. Tonkins of the Board’s action in denying the

appeal (App. 63a-64a).

At the Board meeting o f May 26, 1959, at which time

the Board took action to merge the Pearson Street Branch

o f the Washington School with the Caldwell School, the

Tonkins child was assigned to the Caldwell School for the

1959-1960 school year and notice o f this assignment was

stamped on his report card and sent to his parents on

June 5, 1959. No other application for reassignment of the

Tonkins child to any other school was thereafter filed with

the Board, and at the beginning of the 1959-1960 school

year the Tonkins child entered Caldwell School, where

he was in attendance during that school year. Mr. Tonkins

conceded that he had notice o f the assignment o f Michael

Anthony to the Caldwell School for the 1959-1960 school

year, being the school "to which he had previously sought

admission” (App. 83a).

(3 ) EVEN TS FO LLO W IN G T H E CO N SO LID A

TIO N OF T H E PEARSO N STR EE T BRAN CH

OF T H E W A SH IN G TO N SCHOOL W IT H

TH E C A LD W E L L SCHOOL.

After the Board merged or consolidated the Pearson

Street Branch with the Caldwell School on May 26, 1959,

and directed that all children in both schools (except sixth

graders, who would no longer be eligible to attend an

elementary school) be assigned to the merged Caldwell

School for the 1959-1960 school year, notifications of such

assignments were stamped upon the report cards of all the

Negro and white children (except sixth graders) attending

13

both schools, which report cards were sent to the parents

of the pupils on June 5, 1959 (App. 61a). Thereafter, and

during the period from June 5 to June 15, 1959, the Board

received 351 applications for reassignment of pupils from

various schools in the school system operated by the Board.

Among these applications for reassignment there were

245 separate applications from the parents of white chil

dren who had been assigned to the Caldwell School seeking

reassignment of their children to other schools. At a meet

ing of the Board held on July 21, 1959, these applications

for reassignment were granted. O f these 245 applications

for reassignment which were granted, 191 provided for

reassignment to the Gillespie Park School, a school in

which both white and Negro pupils have been in attendance

since the opening o f the 1957-1958 school year (App. 61a-

62a).

When it became known that the Board had granted the

applications for reassignment of all the white children out of

the Caldwell School, the white faculty at the Caldwell

School requested transfers to other schools, which transfers

were granted by the Superintendent, acting in his admin

istrative capacity, on August 14, 1959. When this action

was reported to a regular meeting of the Board on August

18, 1959, the Board elected a Negro principal and faculty

to the Caldwell School for the 1959-1960 school year.

At no time after these events took place and became

fully known to the adult plaintiffs did either o f them make

any request of the Board through application for reassign

ment, or otherwise, for the transfer of their children to

any other school operated by the Board. On the other

hand, both the two younger McCoy children and the

Tonkins child entered Caldwell School on September 1,

14

1959, and remained in attendance there during the 1959-

1960 school year.

ARGU M EN T

(1 ) SINCE A T T H E TIM E OF TH E H EARIN G

O F T H E B O A R D ’S M OTIO N FOR SU M M A R Y

JUDGM ENT IT A P PE A R E D T H A T TH E M IN OR

P L A IN T IF F SCH OOL CH ILDREN H A D BEEN A S

SIGNED, IN SO FA R AS W A S POSSIBLE, TO TH E

SCH OOL IN W H IC H T H E Y H A D O R IG IN A LLY

SOU GH T TO BE EN ROLLED, TH E D ISTR IC T

JUDGE CO RRECTLY H ELD T H A T TH E QUES

TION S PRESEN TED B Y T H E PL A IN T IF F S ’ COM

P L A IN T H A D BECOM E M OOT A N D T H A T TH E

C O M PLA IN T SH OU LD BE DISM ISSED.

The plaintiffs concede that the younger McCoy children

and the Tonkins child were, indeed, assigned to the school

o f their choice prior to the hearing of the motion for

summary judgment, and that Thetus McCoy, who had com

pleted his sixth grade education, “ may not be entitled to

an order requiring his admission to any particular school

. . .” (App. Br. 27). They also appear to concede that

under the decision of the Supreme Court in Brown II,

“ the personal interest o f the plaintiffs” in non-discrimina-

tory admission to the public schools is the basic issue

at stake (App. Br. 15). This concession would seem to

be mandatory upon the plaintiffs, because this Court has

held that, under the North Carolina Assignment and

Enrollment of Pupils Act (G. S. 115-176 through 115-

179, quoted in footnote 1, supra), school children are

admitted “ as individuals, not as a class or group; and it is

as individuals that their rights under the Constitution are

15

asserted.” Carson v. Warlick, 4 Cir., 1956, 238 F. 2d 724,

at page 729; quoted with approval in Covington v. Edwards,

4 Cir., 1959, 264 F. 2d 780, at page 783, cert, den., 361

U. S. 840, 80 S. Ct. 61, 4 L. Ed. 2d 78.

Insofar as the rights of Thetus McCoy are involved in

this case, it is not disputed that the relief sought on his

behalf in the complaint (that is, admission to Caldwell

School) could not be accorded him, since he had completed

his elementary school education at the time the Court

heard the motion for summary judgment. It plainly appears

that his father knew of his assignment to the Lincoln

Junior High School at the time Thetus took home his

report card on June 5, 1959. Since Mr. McCoy did not

file any application for the reassignment of Thetus to some

other school, manifestly he failed to avail himself o f the

administrative procedure under the Assignment and Enroll

ment o f Pupils Act. W e submit that the plaintiffs have

acquiesced in the Board’s assignment of this child to the

Lincoln Junior High School and that the dismissal o f

the complaint as to him can properly be sustained upon the

grounds that he did not pursue the administrative rem

edies which were available under state law. Carson v.

Board of Education, 4 Cir., 1955, 227 F. 2d 789; Coving

ton v. Edwards, supra; and Holt v. Board of Education,

4 Cir., 1959, 265 F. 2d 95, cert, den., 361 U. S. 818, 80

S. Ct. 59, 4 L. Ed. 2d 63.

After the parents of the other three children learned that

these pupils had been assigned to the Caldwell School for

the 1959-1960 school year, and after they ascertained

that the Board had reassigned out of the Caldwell School

the white pupils on whose behalf such applications for

reassignment had been made, they took no steps whatso

ever seeking reassignment o f these children from Caldwell

16

to another school operated by the Board. Since they origi

nally sought to have these children admitted to the Caldwell

School because o f alleged geographical convenience and

superior facilities, it may be reasonable to assume that,

so far as the children themselves were concerned, the

plaintiffs were satisfied with the Board’s action in assigning

them to Caldwell for the 1959-1960 school year. Messrs.

McCoy and Tonkins could have filed applications for the

reassignment of these three children from Caldwell to

another school, but they did not do so.

At the time of the hearing of the motion for summary

judgment the record before the Court disclosed, without

contradiction, that the relief sought on behalf of the minor

plaintiffs in the original complaint had been granted, in

sofar as was possible. Hence, on the original complaint the

case had become moot, and the Court was constrained to

grant the motion and dismiss the complaint. United

States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S. 629, 73 S. Ct. 894,

97 L. Ed. 1303 (1953) ; United States v. Alaska Steamship

Co., 253 U. S. 113, 40 S. Ct. 448, 64 L. Ed. 808 (1920);

and Cherry v. Morgan, 5 Cir., 1959, 267 F. 2d 305. In

the Cherry case the plaintiffs sought to have declared

unconstitutional an ordinance of the City of Birmingham

which required segregated seating upon passenger buses,

and prior to the trial the City repealed the ordinance,

passing a new one which apparently delegated the matter

o f seating to regulation by the bus company. The District

Court held that the original cause was moot, and also

declined to permit the plaintiffs to file a supplemental

complaint. The Court o f Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

affirmed the dismissal o f the action.

17

It would seem that the plaintiffs practically admit that

they are entitled to no relief upon the allegations of their

original complaint, because they sought leave to file what

they designated as a supplemental complaint, in which

pleading the plaintiffs allege that they are entitled to a

comprehensive injunction requiring the Board to submit

a plan for total integration o f the schools in Greensboro,

this right arising, so they contend, because of the Board’s

action in transferring the white children from the Caldwell

School by granting their several applications for reassign

ment on July 21, 1959. It is implicit in the plaintiffs’ argu

ment m support o f their claimed right to file a supplemental

complaint that the cause o f action asserted in the original

complaint for the enforcement of the individual rights of

the plaintiffs had become moot at the time o f the hearing

in the District Court. This brings us to a consideration of

the second question raised by this appeal.

(2 ) T H E D ISTR IC T JUDGE W A S N OT IN ER

ROR IN DECLIN IN G TO PERM IT TH E P L A IN

TIFFS TO FILE TH E IR SU PPLE M E N TA L COM

PLAIN T.

The North Carolina Assignment and Enrollment o f

Pupils Act has not been accorded mere lip service by the

Greensboro Board. On the contrary, over three years

ago the Board set up the administrative machinery author

ized by the Act, and this procedure was promptly utilized by

the Board in the assignment of pupils to the public schools

beginning with the 1957-1958 school year. This Court

has held that the Act is not unconstitutional, Carson v.

Warlick, supra, and there has been no showing in the case

at bar that the Board has applied any standards in the

assignment of pupils other than those set forth in the

18

Act (G. S. 115-176, see footnote 1, supra). Moreover,

it is not even alleged in the supplemental complaint that

the Board failed to apply these standards when it granted

the applications for reassignment of the white children

who had been originally assigned to the Caldwell School

for the 1959-1960 school term. The supplemental complaint

mistakenly alleges that the minor plaintiffs were assigned

to and the white pupils assigned out of Caldwell School

simultaneously on July 21, 1959. The facts are as stated

above in our Supplemental Statement o f Facts (see affidavit

o f Superintendent Weaver, App. 60a-62a). Upon the record

which was before the District Judge at the time he dis

missed the complaint and denied the plaintiffs’ motion to

file a supplemental complaint, there was no evidence which

showed that the Board had discriminated against a single

school child by denying that child, upon the basis o f race

or color, the right to attend the school o f its choice since

the decision in the Brown case.

The plaintiffs’ argument that they suffered discrimina

tion because of the Board’s action vis-a-vis the applications

for the reassignment of the white children seems to be

coupled with the contention that, despite the fact that

the individual minor plaintiffs were accorded admission to

the school o f their choice, nevertheless the Court should

order sweeping injunctive imposition of total integration of

the races in the Greensboro public schools. This argument

ignores the uncontradicted showing upon this record that

the Greensboro Board has conscientiously and consistently

proceeded in good faith, in accordance with the North

Carolina Assignment and Enrollment of Pupils Act and in

obedience to the mandate of Brown 11, “ to admit to public

schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all

19

deliberate speed” pupils attending the Greensboro public

schools.

While a number o f applicants for the enforcement of

their constitutional rights may be joined as plaintiffs in the

same suit ( Covington v. Edwards, supra), it does not

follow that the injunctive relief sought by the plaintiffs

may be granted in a case such as is disclosed by the facts

in the case at bar. Because the plaintiffs had and still have

available to them the administrative machinery created

by the North Carolina General Assembly under the As

signment and Enrollment of Pupils Act and the rules

and regulations o f the Board issued pursuant thereto,

the plaintiffs must proceed as individuals, not as a class,

in the enforcement of their constitutional rights.

Although the plaintiffs assert in their complaint that

they brought this action on their own behalf and on behalf

o f all others similarly situated, pursuant to Rule 23 ( a ) ( 3 )

o f the Federal Rules o f Civil Procedure (App. 3a), we

submit that the pleadings and affidavits filed by the plain

tiffs disclose that this is not a “ true” class action, because

the judgment binds only the parties before the Court.

Martinez v. Maverick County Water Control, etc., District,

5 Cir., 1955, 219 F. 2d 666. The plaintiffs could not rep

resent any one except children, and their parents, claiming

the right to attend the Caldwell School. As a matter of

fact, the plaintiffs’ reference to Rule 23 ( a ) ( 3 ) is tan

tamount to a concession that the rights they seek to enforce

are several and not joint or common. As pointed out in

3 Moore’s Federal Practice, 2nd Edition, sec. 23.11 (5 ),

page 3472, this is a so-called “ spurious” class action. This

Court has also indicated that the plaintiffs in these school

segregation cases may not maintain a “ true” class action,

20

although several plaintiffs may join together in seeking-

relief from alleged unconstitutional discrimination. Coving-

ion v. Edwards, supra, Carson v. Warlick, supra, and

Holt v. Board of Education, supra. To be sure, other Negro

school children in Greensboro still have the right to sue

the Board if they conceive that the Board has deprived

them of their constitutional rights. Hence, we submit that

the District Court correctly held that the plaintiffs could

not maintain a class action.

Even if it be supposed that these plaintiffs had exhausted

their administrative remedies and were still being denied

the relief which they sought (that is, admission to the

Caldwell School), it is to be doubted that they could

maintain the purported class action which they attempt

to assert, because the cases upon which the plaintiffs rely

(School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen,

4 Cir., 1956, 240 F. 2d 59, and Allen v. County School

Board of Prince Edward County, Va., 4 Cir., 1959, 266

F. 2d 507) are readily distinguished from the case at

bar. Both of these cases were made to turn upon the finding

that injunctive relief was necessary to remove “ the require

ment of segregation” (emphasis supplied). This record

discloses no such requirement; on the contrary, racial segre

gation in the assignment of school pupils in Greensboro

was abandoned by the Board in the summer of 1957.

The cases from the Fifth Circuit2, which are cited in the

plaintiffs’ brief in support o f the contention that the plain

tiffs are entitled to a Court-enforced total integration of

2 Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, S Cir., 1958, 2S8 F. 2d 730;

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction, 5 Cir., 19S7, 246 F. 2d 913, Second

Appeal, 1959, 272 F. 2d 763; Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 5 Cir.,

1960, 277 F. 2d 370 ; and Avery v. Wichita Falls, 5 Cir., 1957, 241 F. 2d 230.

21

the Greensboro public schools, are not in point. In Holland,

Gibson and Mannings it appeared that not a single Negro

child had been admitted to a school attended by white pupils,

and in Avery only a few Negro pupils had been admitted

to an Air Force Base school at the request o f the United

States Department o f Health, Education and Welfare. It

was uncontradicted in these cases that a completely segre

gated public school system was being maintained and

enforced by the school authorities who were the defendants.

In Holland, at page 732, the Court said that “ it is wholly

unrealistic to assume that the complete segregation existing

in the public schools is either voluntary or the incidental

result o f valid rules not based on race.” In the case at bar

no such complete segregation exists. The Court also pointed

out, at page 732, “ that the Fourteenth Admendment does

not speak in positive term to command integration, but

negatively, to prohibit governmentally enforced segrega

tion.”

In the first Gibson opinion, at page 914, the Court noted

that the School Board had adopted a statement o f policy

which provided “ ‘that the best interest o f the pupils and

the orderly and efficient administration o f the school system

can best be preserved if the registration and attendance o f

pupils entering school commencing the current school term

remains unchanged. Therefore, . . . the free public school

system of Dade County will continue to be operated, main

tained and conducted on a nonintegrated basis.’ ” Upon

the second Gibson appeal the Court again noted, at page

766, that “ complete actual segregation of the races, both

as to teachers and as to pupils, still prevailed in the public

schools o f the County” , and that, because of this fact,

the Pupil Assignment Law o f Florida and the Imple

menting Resolution did not, in and of themselves, meet the

22

requirements of a plan o f desegregation of the schools

or constitute a reasonable start toward compliance with

the mandate of the Brown case. The opinion in the second

Gibson appeal specifically stated that the Court did not

disagree with the decisions o f this Court in Carson, Cov

ington, Holt and Allen,

In the Mannings case the Court emphasized the un

disputed fact that the Hillsborough County, Florida, school

system was still being operated upon a totally segregated

basis and that the school board had failed “ to show any

disposition to abandon the segregation policy” (at page

375). It was for this reason that the Court held that the

plaintiffs could maintain a class action for injunctive relief

despite the fact that they had not availed themselves of

the administrative remedies created by the Florida Pupil

Assignment Act. Moreover, the Court expressed some

doubts concerning the constitutional validity of the as

signment standards laid down in the Florida Act. The

plaintiffs say in their brief (at page 21) that this Court has

indicated agreement with Mannings, citing Farley v. Turner

(N o. 8054, 4 Cir., June 28, 1960). This Court cited the

Mannings case solely on the point that where administra

tive procedures fail to meet the standard of affording a

“ reasonably expeditious and adequate administrative rem

edy” , then courts will grant relief to persons whose

constitutional rights are being infringed. However, this

Court said that it “ has consistently required Negro pupils

desirous of being reassigned to schools without regard to

race to pursue established administrative procedures before

seeking the intervention o f a federal court.” In the Farley

case, as in Mannings, it appeared that the school authorities

were adhering to an established and inflexible policy of

23

segregation; hence, there was no need to exhaust futile

administrative remedies. This is the direct opposite o f the

policy pursued by the Greensboro Board.

The facts in the Avery case also differ radically from

the facts in the case at bar. In Avery it was admitted that

the Negro pupils were denied admission to the school of

their choice on racial grounds. Furthermore, there existed

a preconceived plan to transfer en masse all white children

in this school to a so-called “ white” school, which plan was

carried out simultaneously with the transfer o f the Negro

pupils to the school they had sought to enter.

In our case the white pupils were each transferred upon

separate applications for reassignment after the children of

both races had been assigned to Caldwell School. More

over, 191 o f them were reassigned to an integrated school.

The Avery case also quoted with approval the following

portion o f Briggs v. Elliott, D.C.E.D., S. C., 1955, 132

F. Supp. 776, at page 777:

“ ‘ * * * it is important that we point out exactly

what the Supreme Court has decided and what it has

not decided in this case. It has not decided that the

federal courts are to take over or regulate the public

schools o f the states. It has not decided that the states

must mix persons of different races in the schools or

must require them to attend schools or must deprive

them of the right o f choosing the schools they attend.

What it has decided, and all that it has decided,

is that a state may not deny to any person on

account of race the right to attend any school that

it maintains. This, under the decision of the Su

24

preme Court, the state may not do directly or in

directly; but if the schools which it maintains

are open to children of all races, no violation o f the

Constitution is involved even though the children

o f different races voluntarily attend different schools,

as they attend different churches. Nothing in the

Constitution or in the decision of the Supreme Court

takes away from the people freedom to choose the

schools they attend. The Constitution, in other words,

does not require integration. It merely forbids dis

crimination. It does not forbid such segregation as

occurs as the result o f voluntary action. It merely

forbids the use of governmental power to enforce

segregation. The Fourteenth Amendment is a limitation

upon the exercise o f power by the state or state

agencies, not a limitation upon the freedom of in

dividuals.’ ”

A divided Court remanded Avery for further proceed

ings, which appears to be what the plaintiffs seek in this

case. Circuit Judge Cameron dissented from the remand

o f the case. W e submit that his dissenting opinion is not

only legally sound but is replete with common sense. He

cited with approval Carson v. Warlick, supra, and said

(at page 235) that remand would inevitably “ thrust back

into the field of controversy a problem which can . . . move

towards real solution only in an atmosphere of repose and

harmony.” He also said in reference to the remand (at

page 245 ) :

“ This course represents, in my opinion, a strategic

mistake o f real magnitude. Practically every responsi

ble person in a place o f public leadership has stated that

this problem will be solved only as men’s hearts are

25

reached and touched. Weapons have never changed the

human spirit, or fomented good will, and the threat o f

force they carry has never nutured brotherhood. To

tempt one litigant to keep his eyes glued to the gun-

sight, thus provoking the other inevitably to divert most

o f its energies from constructive and probably gener

ous action to preparations for defense, is to perform a

distinct disservice to both and, more important, to the

public.”

In addition to the legal grounds upon which the trial

court relied in refusing to grant the plaintiffs’ motion for

leave to file a supplemental complaint, it is a well-established

principle, supported by virtually every decision on the

point, that such a motion is directed to the discretion o f the

presiding judge and that his decision will not be disturbed

on appeal absent a clear showing of an abuse o f discretion.

In fact, the Court o f Appeals for the Eighth Circuit has

held that an order entered upon a motion for leave to file

a supplemental complaint is not appealable, since such a

motion is addressed to the trial court’s judicial discretion.

Missouri-Kansas-Texas R. Co. v. Randolph, 8 Cir., 1950,

182 F.2d 996. In a recent case, Arp v. United States, 10 Cir.,

1957, 244 F. 2d 571, at page 574, cert, den., 355 U. S.

826, 78 S.Ct. 34, 2 L.Ed. 2d 40, it was said that “ the

granting o f such leave [to file a supplemental complaint]

is discretionary and will not be disturbed on appeal unless

grossly abused” (emphasis supplied). This Court has

said that, while the trial court was correct as a matter of law

in refusing to allow the filing o f a supplemental answer, the

filing of such answer was allowable only in the Court’s

discretion in any event. First Nat. Bank in West Union,

W. Va. v. American Surety Co.. 4 Cir., 1945, 148 F.

26

2d 654. See also Dixi-Cola Laboratories v. Coca-Cola Co..

4 Cir., 1944, 146 F. 2d 43, and Cherry v. Morgan, supra.

W e submit that the plaintiffs have made no showing

to support a finding that District Judge Stanley grossly

abused the discretion vested in him in refusing to allow

the plaintiffs to file their supplemental complaint. Upon

this basis alone it would be proper for this Court to affirm the

action o f the trial court in declining to permit the filing

c f the proposed supplemental complaint.

Moreover, it appears that the proposed supplemental

complaint does not actually relate to the claim presented

in the original complaint. It is the rule that a supple

mental complaint is a mere addition or continuation of the

original pleading, and that it stands on the original com

plaint and is permitted to be filed only for the purpose of

setting forth events which occurred subsequent to the filing

o f the original complaint with respect to the same subject

matter alleged in the original complaint. United States v.

Russell, 1 Cir., 1957, 241 F. 2d 879. As was said in Russell,

at page 882, “ It stands with the original pleading and is a

mere addition to, or continuation of, the original complaint

or answer. It is designed to obtain relief along the same

lines, pertaining to the same cause, and based on the same

subject matter or claim for relief, as set out in the original

complaint.” In the instant case the gravamen of the original

complaint was the Board’s alleged denial to the infant

plaintiffs o f their constitutional rights by refusing to

admit them to the Caldwell School. The proposed supple

mental complaint abandons this position and alleges, in

effect, that the Board deprived the plaintiffs o f their

constitutional rights by admitting them to the Caldwell

School and subsequently allowing the white children, who

27

were also assigned to this school, their free choice of

transfer from the Caldwell School. The supplemental com

plaint also goes far beyond the original complaint in the relief

which it seeks, the plaintiffs praying in the supplemental

complaint that the Court enter an injunction requiring

the Board to integrate in toto the Greensboro public school

system. One o f the tests which has been applied in deter

mining whether the filing o f a supplemental complaint

should be permitted is whether additional and different

evidence on behalf of the plaintiffs will be required to

prove the allegations of the supplemental bill from that

required to prove the allegations of the original com

plaint. General Bronze Corp. v. Cupples Products Corp.,

D.C.E.D., Mo., 1949, 9 F.R.D. 269. Where additional

and different evidence would be necessary to establish the

allegations of the supplemental complaint, leave to file

should be denied. Manifestly, in the instant case quite differ

ent evidence would be required to prove the allegations of the

supplemental complaint from that which would be relevant

in support o f the allegations in the original complaint. In

fact, the plaintiffs recognize this point, because they filed a

motion for continuance pending proposed discovery of

various matters concerning the conversion of Caldwell

School (App. Br. 11). The total departure of the supple

mental complaint from the original complaint is an ad

ditional reason why the trial court’s disposition o f the

plaintiffs’ motion should remain undisturbed.

CONCLUSION

It cannot be denied that the Greensboro Board has

acted and is acting in utmost good faith in its efforts to

solve the problem of removing racial bars in the Greens

boro school system. Its members’ hearts have been reached

28

and touched and their energies have been directed toward con

structive and generous action. The plaintiffs, evidently

unwilling or unable to discern these facts, continue to be

suspicious o f the motives o f the Board’s members. They

keep their “ eyes glued to the gunsight” so that they are

unable to see what is crystal-clear to all others: that is,

discrimination based on race is an abandoned and dis

credited policy in the Greensboro school system. In final

analysis, the plaintiffs have only one grievance: they take

issue with the Board’s action in allowing 245 white chil

dren the same freedom of choice they insist they have the

right to exercise. Their real fundamental contention is

that under the law white and Negro school children should

be forced to sit side by side in the classroom. Unless this

contention is given judicial sanction, the plaintiffs can

not prevail on this appeal. W e submit that their position

is wholly devoid of any merit and that it finds no support in

any of the cases which have dealt with the subject o f

discriminatory practices in the public schools. The judg

ment o f the District Court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

R o b e r t F. M o s e l e y ,

718 Guilford Building,

Greensboro, North Carolina,

and

W e l c h J o r d a n ,

619 Jefferson Standard Building,

Greensboro, North Carolina,

Attorneys for the Appellees.