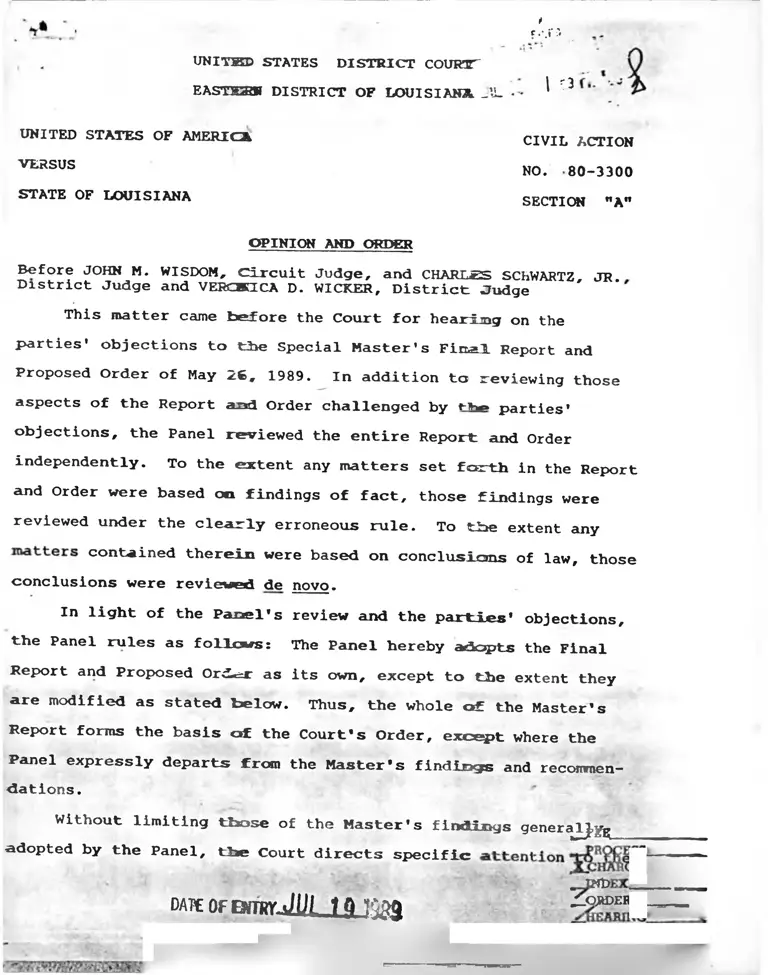

United States v. Louisiana Opinion and Order

Public Court Documents

July 19, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Louisiana Opinion and Order, 1989. 6a65218e-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d81e93ca-e114-4b19-a231-bc29254075f3/united-states-v-louisiana-opinion-and-order. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

tc.-.rr.

UNIinED STATES DISTRICT COUR3T

EASTEHM DISTRICT OF LOUISIAlOt. _\L 1 =:3

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

VERSUS

STATE OF LOUISIANA

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 80-3300

SECTION "A"

OPINION AND ORDER

Before JOHN M. WISDOM, Circuit Judge, and CHARLES SCHWARTZ, JR.

District Judge and VERCaocA D. WICKER, District Judge

This matter came tsefore the Court for hearijng on the

parties' objections to tbe Special Master’s Final Report and

Proposed Order of May 26, 1989. In addition to reviewing those

aspects of the Rep>ort and Order challenged by t-i>̂ parties'

objections, the Panel reviewed the entire Report and Order

independently. To the ecKtent any matters set forth in the Report

and Order were based on findings of fact, those findings were

reviewed under the clearly erroneous rule. To tbe extent any

contained therein were based on conclusions of law, those

conclusions were revieMed de novo.

In light of the Panel's review and the parties* objections,

the Panel rules as follows: The Panel hereby adopts the Final

Report and Proposed Ord«^ as its own, except to the extent they

are modified as stated below. Thus, the whole of the Master's

Rep>ort forms the basis of the Court's Order, except where the

Panel expressly departs from the Master's finding and recommen

dations.

Without limiting those of the Master's findtings generaJJ.^

adopted by the Panel, the Court directs specific

date Of BmJUL15J38S

.IWD

J_Ofa>ER.

DOCUMENT N

following extractions the Master’s Report, xx ntodlfled where

riecessary:

Louisiana currently lias seventeen general st^te institutions

r»f higher learning, orgami zed under four separatsi gpoverning

3x>ards.^ The Board of Cements has general respoDsil>ility for

planning, coordinating «3id reviewing the budgets arrwl academic

progrcun offerings of eacfn state university. Eac±\ of the three

xeinaining boards has sep^xate direct management authority for a

number of the universities. The Louisiana State University Board

of Supervisors ("LSU Supervisors”) oversees Louisiana State Uni

versity and Agricultural and Mechanical College “i_n Baton Rouge

C’'LSU A&M"), the University of New Orleans ("UNO"), Louisiana

State University at Shreveport ("LSU-S"), Louisiana State Univer

sity at Alexandria ("LSU-A") and Louisiana State University at

Evinice ("LSU-E”). The Sonithern University Board of Supervisors

I”Southern Supervisors") oversees Southern University at Baton

Souge ("SUBR”), Southern University at New Orleans ("SUNO") and

Southern University at Stireveport/Bossier City ("SUSBO"). The

Soard of Trustees for Siztje Colleges and Universities

I "Trustees") oversees Lodsiana Tech University in Ruston

I "Louisiana Tech"), GrambXing State University (""Grambling"),

University of Southwestern Louisiana in Lafayette C"USL"), North-

1 The findings appearing herein on pages 2-12 are taken from

P5>. 8-21 of the Special Raster’s Final Report t"E«5X5rt"].

Yluroughout this Order, tlae Master's citations to statements

and depositions of particsolar witnesses have been cnitted, as

reference to such sources cam l>e obtained directly from the

Kamter's Report.

- 2-

m m

^ 2iKt Louisiana UniversitT in Monroe ("Northeast"liorthwestern

St^te University in Natdaitoches ("Northwestern"), Southeastern

:L£niisiana University in Baramond ("Southeastern"), ScNeese State

ISniversity in Lake Charles ("McNeese"), Nichblls State University

f-n Thibodaux ("Nicholls") and Delgado Conrounity CoULege in New

Orleans ("Delgado").

Of these institutions, LSU-A, LSU-E, SUSBO Delgado have

only two-year programs. Additionally, SUNO maintains a number of

îsi»o-year programs as well as four-year programs. Two other pub

lic community colleges— Bossier Parish Community College and

St. Bernard Parish Community College— are separately managed by

tbe State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education and are no

longer defendants in this case, having been granted summary judg-

i*^nt in the Court’s August 2, 1988, ruling. See ted States

y. Louisiana, 692 F. Supp. 642, 658-59 (E.D. La. 1988). There is

not, however, any statewide system of community colleges and a

of regions in the state— most notably the state capital of

Baton Rouge— have no two-year ccMiimunity college.

The remaining schools listed above have four—year under

graduate programs and varying programs for graduate studies.

Tliree state professional schools are also organized under the

same three management boards. The Louisiana State University

Itedical Center, located In New Orleans and Shreveport, and the

Paul M. Hebert Law Center, located in Baton Rouge, are overseen

b y the LSU Supervisors. The Southern University I.aw Center, also

in Baton Rouge, is overseen by the Southern Supervisors. Flnal-

® separate A^icultural Center in Baton Rouge, over-

en by the LSU Supervisors- < y-

-3-

The current governing structure for state univMsities was

cr&ated as part of a revision of the Louisiana Constitution in

Prior to 1974, statevlde coordination was iwrosided by the

Louisiana Coordinating Coomsel for Higher Education, itself cre

ated in 1968, which had limited powers than current

Boajrci of Regents. Most of the state universities were governed

by the State Board of Education at that time, althou^ the Loui

siana State University Boaird of Supervisors separately governed

tbe LSU schools. The 1974 cx>nstitutional revisions divided the

direct governance for state universities into the three current

governance boards and gave the Regents enhanced, though not com

plete, control over budgetary and program matters.

As the Court's August 2, 1988, opinion discusses, four state

'i^riversities SUBR, SUNO, SUSBO and Greunbling— were originally

established as institutions for blacks only. 692 F- Supp. at

647. The remaining four-year state universities were established

for 'whites only. It was not until scxne time after the enactment

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that the State of Louisiana dis

continued official recognition of state universities as single

race institutions. However, with respect to most schools, de

facto racial ident if lability has continued to the present. The

chart below (updating the chart provided in the Court’s August 2,

1988, opinion, 692 F. Supp. at 645) notes the enrollment at each

institution, by race, conqparlng 1981, the year the consent decree

was implemented, with 1988.'

-4-

■ ■ •'h ■' i.Sc

EnronJBent at Louisiana Pifellc Unlversltie« Bv Rac«^ isgi and iQftB

Black

1981

mita

ver«lt?y

•elgado

raablljag

ouialaaaa Tech

cNe«s«

Ichol1«o rU ^ e ia d

srtfaMesternsu th ieas^ tern

3L

SupgjrlBors

!U-A

iU-ACll

lU-E

U Law Sclxml

U-S

O

i , % • %

3,371 40.1 4,348 51.73,777 98.5 44 1.11,194 11.6 8,4S9 82.51,062 15.3 5,706 82.21,068 15.0 5,9S4 83.62,431 22.0 8,544 77.21,296 19.4 4,448 66.61,112 12.6 7,633 86.22,380 17.4 10,931 79.8

151

1,688

237

16

315

2,491

9.9

6.3

15.5

1.9

7.6

16.1.

1,357

22,832

1,283

830

3,803

11,519

88.8

84.7

84.0

96.1

91.5

74.6

hern S q p T v ls o r a

Total

8,404

3,834

10,288

6,943

7,119

11,071

6,682

8,854

13,702

1.528

26,964

1.528

864

4,155

15,432

Black

2.257

5,626

1,236

1,004

819

1,539

1.258

577

2,478

214

1,906

242

30

381

2,439

9.7

7.5

13.9

3.8

8.5

15.5

1988

Khlta

31.5

95.8

12.7

13.8

11.5

15.1

19.5

6.7

17.5

4,268

225

7,186

6,156

6,180

8,461

4,768

7,868

11,200

1,949

22,259

1,483

746

3,991

12,053

59.6

3.8

73.7

84.3

8b.6

83.0

74.1

91.7

79.2

88 .6

88.0

85.1

94.9

88.9

76.5

BR

W

5B0

Total

7,161

5,870

9,751

7,300

7,139

10,193

6,438

8,582

14,143

2,201

25,296

1,743

786

4,490

15,752

7,655

1,994

661

86.4

82.4

99.8

288

11

1

2.6

0.5

0.2

8,’855

2,420

662

8,267

3,130

1,118

92.7

83.9

89.7 ■

398

436

122

4.5

11.7

9.8

8,921

3,731

1,246

32,899 23.6 97,961 70.3 139,305 34,521 24.5 99,749 70.9 140,743

As the chart illustrates^ the racial identifiabULity of Lou-

isiaiia's state universities is especially evident in the coexist

ence of predominantly black Institutions (PBIs) and p«:edominantly

white institutions (PWIs) in close geographic proximltjr in four

areas of the state. In New Orleans^ SUNO currently bas 83.9 per

cent black and 11.7 percent wblte enrollment, while UK> has 15.5

percent black and 76.5 percent white enrollment. In Baton Rouge,

SUBR has 92.7 percent black and 4.5 percent white enrollment,

while LSU A&M has 7.5 percent black and 88.0 x>ercent lAite

enrollment. In the Shreveport/Bossier City area, SUSBO has 89.7

percent black and 9.8 percent white enrollment, while bSU-S has

8.5 percent black and 88.9 percent white enrollment. Finally, in

Lincoln Parish, Grambling has 95.8 percent black and 3.8 percent

white enrollment, while Louisiana Tech, in nearby Ruston, has

12.7 p>ercent black and 73.7 percent white enrollment-

The governing boards of these universities are also racially

identifiable. The Board of Regents currently has sixteen mem

bers, thirteen (81 percent) of whom are white and three (19 per

cent) of whom are black. Of the eighteen LSU Supervisors, four

teen (78 per®ent) are white and four (22 percent) are black. The

Southern Board of Supervisors has four white (22 percent) and

fouxrteen black (78 percent) members. The Trustees aLre the most

integrated of the four boards, with thirteen of eighteen members

(72 percent) white and five mesnbers (28 percent) black- Accord

ing to the most recent data availeible, the total population of

the State of Louisiana is 4.5 million, 69 percent white and 29

percent black.

Given the racially identifiable membership of the Boards,

none, including the Southern board which vigorously seeks to pre

serve its separate identity, is an exponent of racial Integra-

I* r

ticm- Retaining such vestiges of segregation is not aa appropri

ate solution to the problems before this Court, and it can never

be forgotten that this case is about the integration of all of

Loafsfana's institutions of hlgd:ier education.^

A truism thus emerges: Tbe present scheme for governing

education in Louisiana— three operating boards and one coordinat

ing board--has perpetuated illegal segregation in Louisiana's

higher education, even though the system's creation postdates the

f i l m g of this case. The system of multiple boards is therefore

a defect in the state’s system of higher education that violates

the federal constitution.- In addition, the scheme almost guaran

tees a standoff between two "systems" (LSU and Southeml and the

rest of higher education. The strongest argument of those favor

ing the present multi-board system is that the structure of

higher education in Louisiana is irrelevant to the goals of

desegregation and therefore it ought not be changed.^ As stated

above, the Panel rejects this argument outright.

Statistics regarding student performance, discussed below,

demonstrate additional particular constitutional defects inherent

in and perpetuated by Louisiana's present system of higher

education.

According to the statewide student profile ccmipiled by the

Board of Regents (SSPS), in tbe fall of 1988 only 27,146 freshmen

enrolled in state universities, but given past patterns, roost of

2

3

See Report, p. 53.

See Report, p, 48.

-7- \ - r i t . s r : •

thea will not gradiiate. Dr. Treanblay, Coordinator of ]^tesearch

and Oaia Analysis, Board of Regents, sutroitted a chart wbich ana

lyzed tlie status of students after six years who entered as

fresboen in fall 1982.- It shows the graduation rates for each of

Louisiana’s seventeen universities over the six-year period:

Graduation Rates at Louisiana Public Universities -

1982 to 1988

Institution

Trustees

Nujnber Enrolled

Fall 1982 Graduated by Spring 1988

Number_____Percentage

Delgado 705 106 15.0Grajribling _ 674 287 42.6Louisiana Tech 1,644 761 46.3McKeese 1,285 330 25.7Nicholls 1,398 477 34.1Northeast 1,580 534 33.8Nortibwestern 745 258 34.6Southeastern 1,695 546 32.2USL 2,310 788 34.1

LSU Supervisors

LSU A&M 4,486 2,103 44.9LSU-A 421 88 20.9LSU-E 270 89 33.0LSU-S 464 110 23.7UNO 1,931 364 18.9

Southern Supervisors

SUBR 1,294 328 25.3SUHO 352 30 8.5SUSBO 216 24 11.1

TOTAI. 21,470 7,133 33.2

As the chart shows, no state university in Louisiana gr^wiuated

half of its enrollees within six years, and six institutions

failed to graduate even one quarter of their enrollees. Overall,

■St- ‘ -

-r-

'i

-8-

of the 21,470 students who enrolled as first-time fresboen in the

fall of 1982, only 7,133 or 33.2 percent had graduated 'try the

spring of 1988, six years later. The national average for pub

lic universities is 44.9 percent graduated over six years. See

American Council on Education, Digest of Education Statistics 249

(1988) (percentage of students entering in 1980 who grarduated

within the following six years).

The overwhelming majority of students enrolled in state uni

versities in Louisiana are state residents. According to Board

of Regents SSPS data, of first-time freshmen in the fall of 1988,

90.3 percent were Louisiana residents and 9.7 percent were non

residents. Moreover, 58.5 percent of the first-time freshmen in

this sample entered a university in their home parish or in a

parish adjacent to their home parish, while 41.5 percent ventured

further from contiguous parishes to attend college within the

state.

In addi(^ion, black students and PBIs account for a siuch

greater percentage of non-resident students and students from

non-contiguous parishes than do white students and PWIs. For

instance, of the 2,627 non-resident students enrolling as first

time freshmen in fall 1988, 1,539 (58.5 p>ercent) were black and

1,401 (53.5 percent) went to PBIs. By comparison, blacks made up

only 28.0 percent of the total entered students. PBIs clearly

attract more non-resident students and students from distant par

ishes within the state than do PWIs. In the fall of 1988, 33.7

percent of students at PBIs were non-residents and 63.4 percent

came from non-contiguous parishes, while only 5.3 percent of stu-

-9-

dents at PWIs were non-residents and 37.6 percent came froa non

contiguous parishes. Non-resident black students are also far

more likely to go to PBIs them 2u:e resident blacks. Overall,

52.7 percent of black students entering in the fall of 1988 went

to PBIs, but the rate was 88.2 percent for non-resident blacks

attending PBIs as compared to 43-6 percent of resident blacks.

In fact, in 1988 only one state university, Grambling, a

PBI, attracted more than half (55.4 percent) of its student body

out of state. Thus, Grambling is a "national" university in

terras of the residences of its students, with California supply

ing the largest number of students after Louisiana. By compari

son, at LSU A&M, Louisiana's "flagship" University, only 8.4 per

cent of its student body came from outside the state.

The relative college preparation level and college-^ing

rates for black and white high school students in Louisiana fur

ther define the segregation problem confronting Louisiana edu

cation. According to date compiled by the Louisiana State

Department of Education, there were 46,222 high school graduates

in 1988, 15,018 (32.5 percent) of whom were black and 30,126

(65.2 percent) of whom were white. Of these 1988 graduates,

38,844 (3 4 . 0 percent) came from public high schools and 7,378

(16.0 percent) came from private high schools. Public high

school graduates were disproportionately black (36.7 percent

black/60.9 percent white) while private high school graduates

were disproportionately white (10.4 percent black/87.5 per cent

white). Viewed another way, 5.1 percent of black students gradu

ated from private high schools, %«hereas 21.4 percent of vhite

■■ . .. ̂ . ..

- 10-

-- - -;

• ■ - i f <■

__ . __ _________ ^ ' '

.-'j

. 4 r* ^ ' -

'• ■ i-- ...

students graduated from private schools. This disparity is espe

cially pronounced in certain areas, like Orleans Parish, where

83.9 percent of blacks go to public high schools but 90.0 percent

of white students go to private high schools.

College-going rates in Louisiana are also much higher for

white students than for black students. In 1988, 17,816 of the

total 46,222 graduating high school students in Louisiana (38.5

percent) went to college but blac)cs accounted for only 4,263 of

these college-going high school graduates, yielding a college

going rate for blacks of 28.4 percent. By contrast, whites

accounted for 12,647 college_entrants, yielding a 42.0 percent

college-going rate for whites. This disparity in college-going

rates has remained relatively constant in recent years. Five

years ago, for instance, in 1983, the college-going rate for

blacks was 29.2 percent and the college-going rate for whites was

42.5 percent.

Of thos« students who attend state universities in Louisi

ana, whites are much better prej>ared than blacks. According to

1987-88 data from the American College Testing Program (ACT), the

mean high school grade point average (GPA) for all public college

attendees was 2.75. The mean GPA for blacks, however, was 2.54

while the mean GPA for whites was 2.80. Likewise, the mean ACT

score for blacks was 12.74 compared to an 18.67 mean ACT score

for whites. This disparity in preparation is also reflected in

the percentage of first-time freshnen in state universities who

are enrolled in "developmental” (i.e,, remedial) education

courses. According to Board of Regents data, in the fall of

- 11 -

. -'o'

1988, 12,897 (48.0 percent) of all first-tiroe freshmen were

enrolled in remedial courses, but the rate for black students

(71.7 percent) was much higher than the rate for white students

(38.5 percent).

The Louisiana system of public higher education is faced

therefore with a lower college-going rate than the national aver

age and a lower preparation level on average, with black students

in each case being behind white. In what was formerly a dual

system of higher education, the PBIs still educate over 50% of

the black students who enter higher education. The Court’s con

cern which led to_the appointment of a Special Master was pre

cisely that during the period of the consent decree from 1981 to

1987, while more black students entered higher education, the

percentage of black students educated at PBIs versus PWIs

increased. Thus, racial separation in higher education in Loui

siana remains unresolved.

Given the disparate racial compositions of the student popu

lation at schools in close proximity, such as LSU A&M-SUBR in

Baton Rouge, Grambling-Louisiana Tech in Ruston, UMO-SUNO in New

Orleans, and LSUS-SUSBO in Shreveport, the merger of institutions

has been considered. However, merger presents many problems

without any sure benefits of desegregation.* Among the problems

are merging student bodies of highly disparate academic back

grounds, potential loss of qualified faculty and administrators

who were attracted to a school because of its academic character-

Report, p. 37 & n.4.

- 12-

Istics and goals, and underrrining black institutions such L̂8

Grambling and Southern with substantial alumni following.* Thus,

under the circumstances, an opportunity must be given for

Grambling and Southern to make every effort to integrate before

extreme solutions are considered. Therefore, as the Special Hats-*

ter reconinends, the merger remedy is generally reserved at

stage®, with the exception of desegregation of legal education,

which as discussed below, presents unique considerations in the

Panel's view.

Notwithstanding this Court's recognition of the historical

imp>ortance of PBIs and its attendant refusal to order a merger

remedy at this juncture, the focus of this litigation is not

institutions but students.'' Gee State of Louisiana Post-Trial

Memorandum, at 35-37; United States v. Alabama. 791 F.2d 1450,

1455-56 (11th Cir. 1986), cert, denied. 479 U.S. 1085 (1987)

(state universities cannot assert fourteenth amendment rights

against the state). In 1988, 53 percent of Louisiana black

entering freshmen were enrolled in PBIs and 47 percent in PWIs.

This percentage of black students attending PBIs slightly

exceeds that of 1981 when the consent decree began and indicates

the failure of the consent decree approach. Nevertheless, the

opportunities for blacks in Louisiana higher education are

5 Id. at pp; 36-37,

6 Id. at p. 35.

7 The matters appearing on pp. 13-14 herein are taken from Report, pp. 40-41.

-13-

ga 'j QiM i kmmiuii m w i i— ■Ba t i w i

9 X

clearly tiel to t:-je entire state higher education system. Any

desegregaticm plan should seek to Increase the number of Louisi

ana blacks %#ho attend college, which is below the national aver

age, as well as to integrate the existing institutions, espe

cially PBIs, whose percentage of other race students is below

that of the PWIs. Over time, the challenge is to render the very

terms PBI and PWI anachronistic.

The PBIs have developed attractive prograims for black stu

dents, as reflected in the number of out-of-state black students.

But education of out-of-state students (white or black) should

not be a priority of institutions in a state where the college

going and graduation rates of whites and blacks are so low, espe

cially if tuition levels are set so that in-state students siibsi-

dize out-of-state students. On the other hand, high out-of-state

ratios indicate the popularity and reputation the PBIs have

earned.

The more troubling implication is that the PBIs, while

requesting additional money for enhancement, may be more intent

on preserving their mission of serving black students than on

expanding opportunities for white students. The experience of

the consent decree confirms that enhctncement of PBIs without more

simply makes PBIs more attractive to black students, without

attracting %diite students. The focus of the Court's remedial

plan, however, must be on improving the ability of PBIs to edu

cate both black and white students. Preserving Southern and

Grambling for their educational importance means preserving then

as institutions for all Louisiana citizens, not just for black

students.

-14--',

' V . i.T'* •

•' * iS * r* V . .

-- --i- Tf- .. m '---

- ‘V-'i • ̂ i .•'TSk- -

The evidence also suggests Louisiana's multi-board arrange

ment has led to unnecessary and costly program duplication.® The

import of this finding is that the single board solution pos- its

a relationship between efficiency and desegregation, particu

larly to the extent program duplication results from the multi

board structure in Louisiana. It is critical to the success of

integrating the historically black institutions that they be

upgraded and given desirable programs in order to attract a sig-

8 See at p. 49, citing Witness Statement of Roy

McTarnaghan, Vice President for Academic Affairs for the

University of Florida System, pp. 17-18, which charts program

duplication in Louisiana as compared to Florida;

Comparison of Selected Bachelor's Degree Programs Offered and

Degree Productivity; Florida and Louisiama Recent Five-Year

Analysis

Florida Florida Louisiana Louisiana

Florida Average Degrees/ Louisiana Average Degrees/

Programs Degrees Programs Programs Degrees Prograuns

Offered • Per Yr. Per Yr. Offered Per Yr. Per Yr.

Horti

culture 2

Animal

Science 2

Archi

tecture 2

Jour

nalism 3

Speech

Correc

tion 4

Business

Educa

tion 6

■•I"

29

57

116

178

84

67

Jr '*, :V'4'

14.6

28.5

58

59

21

11

6

10

4

9

11

13

12

84

139

91

72

72

2

8.4

35

10

6.5

5.5

-15-

n If leant number of white students. Only by creating an organiza

tional structure with the power to make program decisions state

wide can these efforts be achieved. Inefficiencies also suggest

the dissipation of scarce resources for higher education which,

the difficult fiscal times Louisiama is facing, can only

further impair the state's ability to enhance its historically

black institutions.* Thus, program duplication is highly rele

vant to desegregation.

The size of a single board is also a matter of interest.^®

Size bears on effectiveness and effectiveness obviously relates

to the leverage the single board must assert to achieve desegre

gation. If a board is too large, its mefobers will lack the nec

essary involvement. On the other hand, if the board is too

small, it can be dominated by a few strong views. See Kerr and

The Guardians; Boards of Trustees of American Colleges and

Universities (forthcoming 1989) (where these factors are dis

cussed and aMninimura size board of nine to eleven is

recommended).

As previously indicated, the three operating boards in

Louisiana each have eighteen members, broken down by race as fol

lows: LSU Board of Supervisors (fourteen whiLe/four black);

Southern University Board of Supervisors (four white/fourteen

9 See Report, pp. 51-52.

from Sport'^'^p^%4^^^^^"^ 16-17 of this Order are taken

11 See p. 6, supra.

-16-

I

black); Board of Trustees (thirteen white/five black). The Board

of Regents has sixteen members (including one student), three of

whom are black. Under the circumstances, the size of the single

board proposed by the Task Force of seventeen members (including

one student) seems reasoned^le from the point of view of

effectiveness.

However, the Panel specifically rejects the Special Master*s

finding that desegregation necessitates a conscious effort to

place a quota of blacks on the new board in excess of the per

centage of blacks in the population. The new board members must

be chosen on the basis of their qualifications, with emphasis

upon each board member's own educational background; his or her

experience in teaching or education administration; and his or

her commitment to the implementation of this Order. However,

emphasizing qualifications does not diminish the impropriety of

purposefully excluding black representation on the new board, and

although no ̂ uota is ordered, the new board's racial composition

must be consistent with the findings and directives of this

Order.

With regard to the structure of a proposed remedial system

and the roles of the particular institutions wirhin the system,

there is no obvious and necessary connection between organization

and desegregation.*^* However, a strong correlation between

classifying and tiering public institutions and desegregation may

surely be inferred from structuring higher education to enhance

12 See Report, p. 65.

-17-

I

' v ' ' .

quality while ensuring minority students participate at all lev

els. A system producing better educated students benefits all

concerned.

In formulating that aspect of a remedy bearing upon classi

fication of institutions, no party contests establishing LSU as a

flagship university with selective admissions standards.^’ The

plans also suggest a second tier of institutions, labelled

doctoral" institutions according to generally accepted national

classification schemes.^*

The remaining four-year institutions may be labelled

"comprehensive.— As a rule, these institutions should not

offer doctoral programs.^* They are: Grambling, LSU-S, McNeese,

Northeast, Northwestern, Nicholls, Southeastern and SUNO. While

the Southern Plan proposes further tiering among

This terra is adopted from the

13 at p. 64.

14 Id. at up. 66-67.

15 See at p. 69 & n. 12

State/Task Force pleui.

69-70. Several institutions that would be

comprehensive universities currently offer discrete

doctoral degree programs. For Instance, Grambling offers a

doctoral degree in developmental education, Northeast offers a

m 'd * in offers a Ph.D. and} J^^^^tion. Grambling and Northeast have been

notwithstanding any «?iasIiScIiioroJ^L^ff?ci?ioi''^ their

gmiSiai

educationally sound and consistent with the desegregation goals of this plan, discrete d^to?al

' “ * <‘. .*■ !* : a If A,

these institutions, there seems to be general agreement by the

parties with their missions as they now stand. The board and

President should explore the necessity for further tiering among

these schools in due course, having in mind resource constraints

as well as racial balance. The very purpose of tiering is to

reduce duplication, not to encourage it.̂ "̂ >

Tied to the tiering of institutions is the imposition of

selective admissions standards. Central to the Special Master's

analysis of selectivity and tiering is LSU’s recent experience

with the imposition of a modest selectivity program.^* The tes

timony before the Special Master shows that relatively modest

admissions standards (course work requirements but no rank in

class or ACT minimum) served to produce better prepared appli

cants for admission, in effect forcing high schools to respond to

the preparation challenge. And more imp>ortantly, the number of

black students entering LSU was not lessened; Board of Regents

data show th^t 8.2 percent of the 1988 entering class was black,

which actually marks a small increase over the historical per

centage of black students at LSU.

The current practice of open admissions to all four-year

institutions is counter-productive, both in terms of educational

objectives and racial integration. The objective is not simply

to admit students into college, but to educate and graduate them.

17 Report at p. 70, citing Chart set forth herein on p. 15, n. 8 supra.

18 See Report, pp. 71-73.

-19-

In terms of undergraduate degree productivity, the Louisiana open

admissions system is a f a i l u r e . A s previously discussed,^®

system-wide only 33.2 percent of the students who entered higher

education in Louisiana in 1982 had received bachelors and associ

ates degrees after six years of attendance, far below the nation

al average of 44.9 p>ercent for public universities.

Thus, with an open admissions system, students enter higher

education (both four and two years) easily, but do not readily

leave with degrees. Moreover, the problem is particularly acute

at institutions with a large black population, notably SUNO.

The Special Master's recoiiimendations regarding the tiering ^

of institutions included the creation of a community college sys-

tem.^^ Louisiana has never embraced community colleges as an

integral part of its higher education system and as a result, its

community colleges are relatively undeveloped as an educational

19 See at p. 72. Given that almost 50 percent of the

entering students need remedial (develoimiental) education, degree

productivity will not be high. See id. at p. 75 & n. 17, citing

Tremblay Hearing Exhibit 2, which shows that 48 percent of fall

1988 four-year college students needed developmental education.

The figure was 77 percent for black students. Interestingly the

percentage of those needing developmental education was also 48

percent for students at two-year colleges, suggesting that four-

year schools provide as much if not more remedial education than

two-year schools. This also points to a hidden cost of the open

admissions system which fails to organize students by academic

ability. It creates program inefficiencies since all of higher

education must devote resources to developmental education.

20 See pp. 7-9, supra and Tremblay Chart.

21 Four community colleges are defendants in this case;

Delgado (New Orleans); LSU-Eunice; LSU-Alexandria; and Southern-

Shreveport. Their total enrollment is about 12,000 students of

whom about 3,800 or 32 percent are black.

■Jiif

- 20-

resource. Louisiana ranks 48th among states in the number of

higher education institutions in relation to college age popula

tion largely because of the paucity of community colleges. More

over, community colleges serve a non-traditional age population

largely unserved in Louisiana, even though Louisiana has a very

low high school cc«npletion rate which accentuates the need for

lifelong learning. Community colleges are also necessary to

insure remedial education of those who might be excluded from the

less accessible four-year college system, thereby helping to

ensure a racially balanced s y s t e m . A system created from eunong

the existing independent community colleges would have had 12,351

students in 1988, of whom 31 percent werfe black.***

The Special Master expressed trepidation in reclassifying

SUNO, with its extraordinarily low productivity as a four-year

liberal arts university.*® Nevertheless, SUNO’s two-year role

has been no more successful than its four-year mission. More

over, SUNO's»two-year offerings overlap with Delgado's, whereas

SUNO will be the only open admissions four-year university in New

Orleans, once UNO adopts selective admissions. If the re-orien

tation is conscientiously pursued by the board and the SUNO

administration, creating this new niche for SUNO may lead to

improved degree productivity. The new board should, therefore.

\ 22 See Report, pp. 82-83.

i 23 See id. at p. 84.

1 24 Id.

25 See id. at pp. 89-90.

- 21-

review SUNO’s two-year degree offerings and either terminate them

or transfer them to Delgado.

Against this background, the new system of higher education

proposed by the Special Master and adopted by the Panel may be

diagrcimmed as follows:^*

26 See id., pp.^91-92.

— 22-^iy.

- i'-. -Vut.'-i'l'-i1,1’:/ ■ ■

. 5̂r-’ .v-v”

Organization of Propos«d Unlvarslty of Louisiana Systm

I

Univarsity of Louisiana Board

V.P. for Dasagragation Cooplianca

Prasidant of Syscaa

Staff

V.P. for Coonunity

Collagas

LSU l&H LSU-S SUBR SUNO UTacb Um USL Graobling HcNaesa Nicholls No-East No-Vast So-Eastam

(LSU-Law) (So-Lav)

(LSU-Had)

CLSU-Ag)

Louis ian

Southern

CC Syste

(LSCC-f

(LSCC-E)

(LSCC-S)

(LSCC-Dalga

The minimization of program duplication is an essential

aspect of the Special Master’s proposed reorganization of the

school system. The evidence demonstrates there is more program

duplication in Louisiana than is desirable fr«ii the point of view

of educational efficiency.*^ Dr. McTarnaghan shows how Louisi

ana has more degree programs in many areas than does Florida^

even though Florida is a much larger system and state.*®

McTarnaghan attributes much of this program duplication to

the lack of a single board with adequate authority to initiate or

terminate programs. He notes excessive duplication costs money

and renders the programs less viable from a qualitative perspec

tive. Moreover, McTarnaghan also suggests duplication permits

schools to cater to students of one race, thereby hindering

desegregation goals. Other witnesses, notably Clifton Conrad,**

confirm program duplication is excessive in Louisicina and that it

fosters racially identifiable schools.*®

There is accordingly no doubt in the Court's mind that

duplication of programs can have a stultifying effect on desegre

gation. Therefore, the board must take as one of its first mis

sions the reduction of duplicated programs, especially where they

involve proximate institutions.**

27 See id. at, p. 93.

28 See chart in note 8, p, 15, supra■

29 Conrad testified on behalf of the United States. He is a

Professor of higher education at the University of Wisconsin.

30 See Report, p. 94 & n. 25.

31 See Report, p. 95. To some extent, this assignment is tied

-24-

.• ?J l 1 * V .

Sv

K*.

I '

In the cataloguing the problems associated with unwarranted

duplication of programs, legal education in Louisiana looms

large. There are two state supported law schools in Louisiana,

Southern Law Center and the LSU Paul Hebert Law Center, both

located in Baton Rouge. In terms of racial identiflability and

academic achievement, they present remarkably different pictures.

Southern Law Center is desegregated, with a student body 58 per

cent black and 42 percent white and a faculty (including part-

time) which is virtually 50/50. LSU Law Center on the other hand

has a minuscule percentage of black students. During the period

of the consent decree, it ranged from 1.9 percent to 0.8 percent.

In 1988, it was only three percent.^* Moreover, the Louisiana

bar passage rate at LSU Law Center has averaged about 90 percent

over the last five years, whereas at Southern Law Center it is

under 50 percent. LSU Law School is a more successful law school

from that perspective, but Louisiana blacks are largely edu

cated at the inferior school. Yet, competitive, quality legal

education for blacks is particularly important because the ratio

of black lawyers to the black population is very low, and law

to the tiering proposal the board roust also implement. However,

primarily graduate level programs and much of

the duplication currently exists at the undergraduate level.

( S ^ McTarnaghan table in note 8 supra.) in terms of the

desegrega^on data in this case, undergraduates are a critical

aspect. The n u ^ r of students Involved is far larger and the

enrollment choice is likely to be more pronounced.

See Report, p. 96.

33 See id. at p. 97.

-25- iW :. i : lit':

<T̂ ■

degrees are often recognized as an access point to political and

economic power. ̂ ■*

Thus, the Panel perceives the focal issue concerning legal

education to be different from the issue identified by the Spe

cial Master.** The issue is how to desegregate legal education

overall, not just LSU. Unlike the other Louisiana institutions,

the two law schools have identical programs and exist virtually

side by side. Moreover, the programmatic difficulties of insti

tutional merger in the university context generally are greatly

lessened in this instance since both institutions award only a

single degree (J.D.). _

LSU Law Center’s low percentage of blacks seems to be a

function of an admissions policy that makes no effort to attract

black applicants, since it is significantly below the percentage

of black undergraduates at LSU-A&M and the number of blacks at

the state’s two private law schools.** Moreover, those few

blacks who dy graduate from LSU Law School succeed in passing the

bar (of the eighteen black students at LSU since 1982-83, none

has failed the bar). Affirmative action programs setting goals

like the new admissions standards at LSU-A&M are an appropriate

place to begin the desegregation of legal education. A ten per

cent category of admissions exceptions whose puri>ose is to

increase the diversity of LSU Law School and the number of black

34 See id. at p. 96.

35 See W . at p. 96.

36 See id. at pp. 97-98.

-26-

graduates is appropriate and should be immediately implemented

for the 1990-91 school year. LSU should also offer substantial

scholarships to black students and undertake vigorous recruitment

efforts aimed at black students.

However, as long as the two institutions of disparate qual

ity exist, the State will continue to produce a secondary class

of lawyers unable to compete fully in the professional context.

Given the racial composxtxon of the two schools, the negative

impact of this disparity will fall largely upon the black law

student population, and given the consent decree experience, a

simple provision of funds will not resolve this problem, even

assuming such funding is a realistic possibility.

Thus, over the next five years, the Board must develop a

plan for merger of the two schools; a gradual merger over a five

year period of time will minimize the necessary adjustment by the

students, administration, and faculty and the impact of curricu

lum change. .Duplication of programs should be gradually elimi

nated and new admissions standards for the single Law Center

evaluated, with continuing provision for a special category of

admissions at no lower than ten percent. New admissions stan

dards should also be prepared with a view towards ensuring that

the merger of the two institutions does not disproportionately

burden the black law student population, even though the Panel

envisions the imposition of more stringent admissions standards

at the new merged law school than are presently imposed at

Southern.

- 21 -

The Court also declines to adopt as a remedy any order that

specific dollar amounts of operating expenses or capital to be

spent on enhancement of existing institutions.*^ Nonetheless,

the new board must make provision for such funding as is neces

sary to implement the program transfers ordered herein and any

other new programs the single board orders, whether such funding

be referred to as "enhancement," as the Special Master stated, or

otherwise. Determination of specific dollar amounts requires

carefully drawn budgets not made a part of the record in these

proceedings. The president of the system and his or her staff

must calculate the funds needed for operating purposes and expend

them properly.

Since the necessity for higher education budget cuts has yet

to be determined, the most that need be said now is that all cuts

as well as increases must be made consistent with the desegrega

tion goals of this plan. At a minimum, funding reductions should

not dispropostionately affect black students or the PBIs and

existing funding for those PBI enhancement programs successful in

substantial other race students should be protected

from budgetary ax.*“

A final remedial measure recommended by the Master and

adopted by the Court is monitoring of the actions taken by the

state to implement this Order. The need for a monitoring func

tion is premised largely upon the Court's continuing jurisdiction

37 See id., pp. 104-05.

38 See i^, p. 107.

-28-

over this case, and some form of monitoring is necessary to aid

the Court in the exercise of its jurisdiction. The remedies dis

cussed herein place most of the responsibility for compliance

upon the state and its institutions, where responsibility should

lie if desegregation is to become a reality for Louisiana. The

single board and its chief executive are given extensive powers

to end the racial identiflability of Louisiana higher education.

At the same time, of necessity much of the impact of this remedy

is to be felt in the future. Thus, it is difficult to argue that

the system should be released from oversight by the Court at this

stage. A period of review, over five years, is the only prudent

way to assure the implementation of the remedies proposed.^®

Thus, pursuant to the Special Master’s Final Report as

modified above and consistent with the Court's prior orders, it

is specifically ORDERED as follows;

Single Governing Board

1. Within 30 days of the entry of this Order, the four

boards currently governing public higher education in Louisiana

shall be disbanded and their powers consolidated into a single

state governing board. The new board ("board") shall be given

ultimate authority over academic, budgetary, personnel and admin

istrative affairs of each of the public institutions currently

overseen by the Board of Trustees, the Southern Supervisors and

the LSU Supervisors. Additionally, the board shall be given the

special mission of monitoring and implementing the remedial Order

39 see id., p. 112.

-29-

of the Court and of insuring that progre^ss toward eliminating

Louisiana's racially dual education system is achieved. The

board shall determine an appropriate name for the new coordinated

system of higher education, such as the "University of Louisiana

System.

2. The board shall have seventeen voting members and one

student member. The board shall elect a chair from among its

members on an annual basis. The voting members shall be

appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the Louisiana Senate.

Board members shall have staggered terms of five years and

reappointment for one additional term shall be permitted. The

initial terms shall be for three, four or five years in order to

permit the staggered system to begin. These terms shall apply to

six, six and five members, respectively.

The board members appointed pursuant to this Order shall

include three persons chosen from the present Board of Regents,

with one person to hold a three year appointment, one a four year

appointment and one a five year appointment; two persons chosen

from the present LSU Board of Supervisors, with one person to

hold a four year appointment and one person to hold a five year

appointment; two persons chosen from the present Southern Board

Supervisors, with one person to hold a four year appointment

and one person to hold a five year appointment; and two persons

40 The names and titles used in this order are only

suggestions; the board is free to craft different names or titles

so long as they are otherwise consistent with the remedial goals of this plan.

-30-

chosen from the present Board of Trustees, with one person to

hold a four year appointment and one person to hold a five year

appointment. “*•

In making appointments to the board, the Governor shall not

only select persons with established skills and experience in

higher education, but shall also select persons firmly committed

to the desegregation goals of the Court’s Order and the Court’s

methods for implementing the Order. Additionally, board members

shall be selected to broadly represent the racial, ethnic, gender

and geographic diversity of the state.

3. For the first five years, while the remedial provisions

of the Court’s Order are being implemented, the Court shall

reserve the right to veto the composition of the board, if the

board’s composition does not adequately take into consideration

the goals of this Order or does not work to ensure participation

by Louisiana’s black citizens. In addition, the board shall

appoint one student member on an annual basis, pursuant to a pro

cedure established by the board. A black student frequently

should be appointed.

4. The board shall be charged with appointing a full-time

president. This person shall have an established and extensive

background in higher education governance, and a sensitivity to

the educational needs of racial minorities. The president shall

-31-

serve at the pleasure of the boir<| and be delegated operational

authority over the university system.

5. There shall be a substantial administrative staff to

support the new president, which will utilize the personnel and

resources of the Board of Regents and the three operating boards,

as appropriate. The president shall have the responsibility to

recommend to the board appointment and, if necessary, removal of

chancellors of each of the system campuses. Additionally, a spe

cial vice-president for desegregation compliance, whose mission

is to oversee implementation of the Court's plan, shall be

a p p o i n t e d t h e board upon the recommendation of the president.

This special vice-president shall be responsible for developing

and implementing other desegregation proposals approved by the

board; for compiling data on all aspects of desegregation in Lou

isiana public higher education; and for reporting to the monitor

ing committee as hereinafter required.

6. Within 90 days after the entry of this Order, the board

shall develop and implement procedures for the use of advisory

committees at each state university and community college. Among

their duties, these committees shall provide advice and assis

tance to the president and the vice-president for desegregation

compliance, as requested. The size of these advisory committees

shall be set by the board but shall not exceed 17 members. All

state universities shall be encouraged to form such committees

which will provide non-binding advice and information about cam

pus life to the board. Like the board, these advisory commit

tees shall be appropriately composed to further the goals of this

Order.

-32-

I Classification of State Universities

7. Within 120 days, the board shall implement a scheme for

classifying each state university according to its mission and

taking into account its undergraduate, graduate and research pro

grams and the degree of selectivity in admissions. Such classi

fications shall be consistent with the tiers set forth below and

shall be designed to reduce the number of programs statewide.

The board shall be especially careful to differentiate the mis

sions and academic programs of proximate PWIs and PBIs.

8. LSU A&M shall be designated by the board as the

research university in the state university system and recognized

as Louisiana’s flagship state institution. It shall continue to

have the greatest number of graduate and research programs and

shall implement the most selective criteria for admission. LSU

A&M’s undergraduate admissions shall be limited to the top eche

lon of graduating high school seniors in light of standards

estedslished 4>y the board, with selectivity based on criteria dis

cussed below. These selective admissions standards shall be

established within 120 days and implemented for the 1990-1991

school year. All remedial education courses shall be eliminated

by the 1990-1991 school year.

9. The board shall also designate an intermediate level of

state institutions offering significant doctoral and other gradu

ate programs in addition to four-year undergraduate programs.

These universities shall be somewhat less selective than LSU A&M,

based on criteria discussed below. The selectivity standards

shall be developed within 120 days and implemented for the 1990

I -33-

i-I

1991 school year. Liice LSU A&M, this group of universities shall

have little need for, and thus by the 1993-1994 school year, no

remedial education courses. The group of intermediate doctoral

institutions shall initially be Louisiana Tech, SUBR, UNO and

USL. The board shall be responsible for developing a realistic

timetable for SUBR, with the imposition of selective admissions

and the development of its doctoral level programs taking no more

than three years.

10. The board shall designate the remaining four-year pub

lic institutions — Grambling, Nicholls, SUNO, LSU-Shreveport,

'McNeese, Northeast, Northwestern and Southeastern as compre

hensive universities which will have very limited graduate/

research missions and less selective or open admissions. The new

board shall within 120 days set the admissions standards for all

of these institutions with the exception of Grambling, which

standards shall be implemented for the 1990-1991 school year.

Care shall £̂ e taken to insure that at least some of these insti

tutions move away from open admissions toward some degree of

selectivity (which might be the requirement of completing a col

lege preparatory curriculum).

11. With respect to admissions standards for Grambling and

Louisiana Tech, the Court hereby adopts as part of its Order the

stipulation of the parties appearing as Appendix B to the Special

Master’s Final Report, but only to the extent such stipulation

and its implementation are consistent with this Opinion and

Order.

-34-

12. Within 180 days, existing graduate programs at compre

hensive universities should be evaluated for continuance. So

long as they are educationally sound and foster the desegregation

goals of this Order, some discrete, non-duplicative graduate pro

grams may be maintained.** Comprehensive universities may retain

remedial education programs, especially if they remain open

admissions institutions. However, the primary focus for remedial

education shall be shifted in the future to the community

colleges, which will be solely open admissions institutions.

Selective Admissions Standards

13. The state shall end the traditional system of o{>en

admissions to all state universities. Consistent with the clas

sification scheme laid out above, selective admissions require

ments shall be developed by the board within 120 days and imple

mented at selected Louisiana public universities by the 1990-1991

school year. Only five institutions are made selective directly

under this Order {and one of them, SUBR, only after three years).

The board has discretion to make further selectivity distinc

tions with the remaining institutions, so long as the admissions

standards of the five selective schools designated herein clearly

distinguish them from the remaining institutions.

14. State universities shall base admission decisions on

some combination of high school grades, high school class rank,

high school courses taken, personal recommendations, extracurric-

42 See, e.g., n. 16, supra p. 18.

-35-

t ■

ular activities, essays or personal statements, interviews and

standardized test scores. The precise formulation of the crite

ria for each institution shall be approved by the new board.

ACT and other standardized test scores provide valuable data.

However, they should be used as admissions tools only in conjunc

tion with other high school performance data. Primary emphasis

shall be placed on high school grades, class rank and breadth of

course work undertaken.

15. Within 120 days, the board shall develop appropriate

programs of high school course work that will be required for

admission at each institution. In developing these requirements,

the board must consult and work with the Board of Elementary and

Secondary Education and the state's high schools to insure that

resources are put in place to meet demand. New course work

requirements must be phased in commencing with the 1990-1991

school year to allow hxgh schools and students a period to adjust

and shall be.fully implemented by the 1993-1994 school year.

16. Each state institution shall have fifteen percent of

its entering class set aside for admissions exceptions. Ini

tially, ten percent shall be used for admitting other race stu

dents (that is, black students at PWIs and white students at

PBIs), with the remainder available for other institutional

interest students such as athletes, students with other talents

and alumni children. The precise mechanism for administering the

admissions exceptions shall be developed by the president and the

campus chancellors but the emphasis shall be fostering integra

tion at each campus. Like selective admissions standards thp»m-

-36-

selves, the admissions exceptions shall be developed within

120 days and implemented for the 1990-1991 school year. The use

of a ten percent other race set-aside does not mean that overall

ten percent other race enrollment is acceptable. The goal is

that each campus substantially increase its proportion of other

race students and thus eliminate its racial identifiability; this

goal demands more than ten percent other race enrollment.

Comprehensive Community College System

17. The two-year community colleges subject to the Court's

Order (LSU-Eunice, LSU-Alexandria, SU-Shreveport/Bossier City and

Delgado) shall be reorganized as part of a single comprehensive

community college system for Louisiana. The plan for this reor

ganization shall be completed within 180 days so that the ccxnmu-

nity college system shall be in place by the 1990-1991 school

year. All two-year community colleges and vocational schools

(including, for example. Bossier Parish Community College and

St. Bernard Parish Community College) should be incorporated into

this system. The board shall also develop an appropriate naune

for the new system, such as "Louisiana Southern Comrounity College

System."

18. . Upon recommendation of the president, the board shall

appoint a special vice-president for the community college system

who will report to the board through the president. This

appointment shall be made within 90 days. The special vice pres

ident shall oversee and coordinate the affairs of all community

colleges, including the appointment of chancellors at each

campus.

-37-

19. The community college system vice-president and the

president shall insure that, within 180 days, articulation agree

ments are executed between each of the community colleges and the

four-year institutions for the 1990-1991 school year. Such

agreements shall be widely advertised and shall provide for

transfer of students successfully completing two-year academic

degrees, although four-year institutions with selective admis

sions may adopt selectivity standards in admitting transfer stu

dents. The community college system shall also provide voca

tional and technical education and adult education, but its

transfer mission, especially as it relates to minority opportuni

ties, shall be the focus of its efforts at the outset.

20. Community colleges shall retain open admissions stan

dards and shall emphasize remedial education courses. By the

1993-1994 school year, the board shall concentrate remedial edu

cation courses in the community colleges, with no remedial

courses remaining at four-year universities, with the exception

of those comprehensive universities that retain open

admissions, '•*

21. By the 1990-1991 school year, the remaining two-year

programs at SUNO shall be transferred to Delgado leaving SUNO as

the comprehensive four-year institution in New Orleans, with less

selective or open admissions. The board shall study whether

Delgado's offerings currently meet the demand for community col

lege education in New Orleans and increase Delgado's offerings as

43 See, para. 12 of Order, p. 35, supra.

-38-

needed. Within 180 days the board shall review two-year course

offerings at other four-year institutions to determine whether

they should be continued or transferred.

22. The board shall study the need for and feasibility of

starting new community colleges in the areas of the state where

none currently exist. Special attention must be given to Baton

Rouge, where a community college will be needed to service local

students not able to be admitted at LSU A&M and SUBR, once both

have selective admissions. The board shall therefore begin plan

ning for a new college campus in Baton Rouge within the first

year.

Program Transfer and Enrollment Management

23. With the exception of LSU Law Center and Southern Law

Center, merger and/or closing of existing state universities need

not be undertaken at this time. Instead, the board shall imple

ment a system of enrollment management, program review and pro

gram transfer to address the problem of prograim duplication and

accompanying waste of resources and segregation. The board shall

assign to the president the mission of reviewing all current

course offerings. Within 180 days, the president shall recommend

appropriate enrollment levels for each academic program and also

identify progreuns not meeting minimal quality standards and rec

ommend that they be eliminated or consolidated with similar pro

grams at other state universities.

24. The board shall then take appropriate action with

respect to eliminating, consolidating and setting enrollment lev

els for academic programs, which shall be implemented by the

-39-

1990-1991 school year. The board shall ensure that such action

is sensitive to the desegregation goals of this plan. Thus

enrollment limits shall be set with an eye toward preventing

"flight" of students to same race schools. As an example,

enrollment limits at Southeastern shall be used to prevent South

eastern from becoming a "flight" school for white students not

gaining admission to LSU A&M or UNO, but who are reluctant to go

to SUBR or SUNO.

25. The program transfers agreed upon by Louisiana Tech and

Grambling shall be implemented by the 1990-1991 school year.

Like other programs, howeverthese programs are subject to fur

ther evaluation by the board and the monitoring committee, and

since the Special Master no longer has jurisdiction over this

case, any changes in the stipulation’s proposals shall be submit

ted to the board. The details of the Louisiana Tech/Grambling

transfers are contained in the stipulation attached as Appendix B

to the Special Master's Final Report, which provisions the Court

adopts as part of its Order, to the extent such provisions and

their implementation are consistent with this Order.

26. By the 1990-1991 school year, the board shall begin

implementing the merger of Southern Law Center into the LSU Law

Center. To the extent consistent with the reg[uired core curricu

lum at each law school, the board shall immediately insure that

certain high demand course offerings are not duplicated between

the State’s two public law schools. LSU Law School shall under

take as soon as practicable, but no later than the 1990-1991

school year, vigorous efforts for recruiting blacks. Including

-40-

.# -

♦-en percent admissions exceptions for black students, offering

scholarships to prospective black students and appointing a spe

cial admissions officer for black students, as described above in

this Order.**

In implementing this merger, the board shall appoint a chan

cellor for the new unified Law Center by the 1990-1991 school

year who shall work with the board to effectuate merger of fac

ulty and curriculum and re-evaluation of existing admissions

standards. In so doing, it is not the intent of this Order to

damage the quality of legal education at the LSU Law Center; to

require significant lowering of admissions standards; or to

require any lowering of academic requirements for those students

who do gain admission.

Funding for Implementation of this Order

27. Taken into consideration funds freed by the elimination

of duplicative programs, the board, in conjunction with the pres

ident and staff, shall develop budgets for the newly reclassified

institutions, including non-formula expenditures for improving

the quality of PBIs whenever fiscally possible. Capital needs

shall be evaluated on a similar basis and priority given to those

facilities that will support programs to attract other race stu

dents. The board shall complete this task within 180 days in

conjunction with the 1990-1991 higher education budget

submissions.

44 See text, pp. 26-27, supra.

-41-

other Race Rec::ultment and Retention

28. The board shall develop a coordinated program for

recruitment and retention of other race students, faculty, admin

istrators and staff at all state universities and professional

schools within 120 days, which shall include:

(a) Scholarships for other race students. A program

of scholarships designed to attract other race students to both

PWIs and PBIs shall be developed by the board. A fixed percent

age of each institution's overall operating budget shall be set

aside for this purpose by the board upon recommendation of the

president. Moreover, the board shall establish a state-wide

other race scholarship program.

(b) Other race admissions officers. Each PWI and PBI

shall have at least one admissions officer whose sole function is

to recruit other race students. Such person shall be charged

with developing, coordinating and executing all of the institu

tion's other-race student recruitment programs.

(c) Equal opportunity statements. Each institution

shall develop a strong, written equal opportunity policy, both as

to students and employees. This policy shall be reviewed by the

special vice-president for desegregation ccmnpliance and approved

by the board.

(d) Public information efforts. Under the direction

of the board, each affected institution shall develop and imple

ment significant campaigns for disseminating to prospective stu

dents and employees information about each state university, its

programs and its equal opportunity policy. Among other things,

-42-

\

public information efforts shall include the use of biracial

recruiting teams from each PBI and PWI which shall visit high

schools in their region and throughout the state, as appropriate.

(e) Developing relationships between high schools and

colleges. The board shall identify state institutions particu-

l^rly situated to benefit from special outreach progreuns to high

schools in predominantly other race areas. Such programs shall

be designed to reduce the strangeness and alienation students

often associate with other race institutions. Programs shall

include summer sessions in which high school students live on

campus and are familiarized with a university's programs and

facilities. A pilot project shall be commenced at Southeastern

for the summer of 1990.

(f) Incentives. The board shall set annual integra

tion progress goals for each institution which are demanding yet

and which require roughly equivalent progress at each

institution.* The board shall develop financial incentives for

institutions that meet or exceed their annual goals. Financial

rewards might include additional funds for scholarships or

approval for new program offerings. Incentives shall increase by

the degree to which the goal is exceeded. The board shall also

consider employing "reverse Incentives" or taxes for institutions

which consistently fail to meet their goals.

Monitoring Committee

29. A three-member committee shall monitor progress toward

desegregation. The committee shall consist of (1) Paul W, Mur-

rill; (2) Frank E. Vandiver; and (3) Franklyn G. Jenifer. Cora-

-43-

mittee members shall be paid a reasonable per diem and expenses,

with Dr. Murrill and Dr. Vandiver's per diem and expenses to be

taxed as costs against the State of Louisiana to be allocated to

the budgets of the various institutions as the new board deems

appropriate. Dr. Jenifer's per diem and expenses will be paid by

the United States.

30. The monitoring committee is hereby charged with inde

pendently evaluating the progress of the new board and each

institution towards specific compliance with this Order and with

the overriding desegregation goals set by this Order. Copies of

the minutes of all meetings of the new board shall be sent to the

members of the monitoring committee within one week of each board

meeting. The committee shall meet with the new board at least

four times per year, and within one week after each meeting of

the board and the committee, the committee shall file a Report to

the Panel. The first meeting of the new board and the committee

shall take place within 90 days of the appointment of the new

board.

The committee's reports shall specifically advise the Panel

of the progress or lack of progress towards achieving desegrega

tion. Each member shall have access to the Court at all times,

provided such person communicate to the Court in writing, file a

copy of any such communication in the record of these proceed

ings, and send a copy of any such communication to the other com

mittee members.

-44-

• < ' ' f '

At least in the early stages of implementation, the monitor

ing committee shall be available to review and respond to deci

sions of the new board on an as-needed basis.

31. The monitoring committee shall give the new boArd a

period of five years to achieve substantial progress toward elim

inating the racial identiflability of Louisiana’s universities.

If at the end of five years substantial progress is not shown,

the committee shall recommend to the Court more direct solutions,

including Court appointment of board members or direct control by

the committee of the system of higher education and merger of

institutions. However, nothing stated herein shall be construed

as a divestiture of this Court's continuing jurisdiction to take

appropriate action to enforce this Order.

Interim Procedures

32. As previously indicated, the board shall be appointed

and confirmed within 30 days of the entry of this Order. As each

board member is appointed, the Panel shall be advised of such

appointment by letter and shall be provided with a copy of such

person's curricul\ma vitae.

If after 20 days from the entry of this Order the Governor

foresees that all board members will not be appointed and con

firmed within 30 days, the Governor shall submit to the Court a

proposed timetable for completing the board selection process

under the guidance of the monitoring committee. If the ccmimittee

deems it necessary, it may recommend to the Court names of mem

bers to serve on the board. The Court reserves the right to make

any appointments necessary to complete the composition of the

-45-

board in a timely fashion or to veto the appointment of any board

member.

33. The board shall assume responsibility for managing the

state university system and implementing this remedial Order as

soon as it is formed. While its first responsibility is to

search for and appoint a system president, the board should imme

diately appoint an interim president. The interim president

shall serve until the president is selected, in order to insure

that centralization of control occurs forthwith and that the

steps to be taken during the first year of the Order are not

delayed. The board should have the full authority of the state,

through the Governor and other state officials, to carry out its

mandate. Any questions that arise during the interim period

regarding implementation of this plan may be directed to the

-46-

monitoring comm'.ttee and by the committee to the Court, if

necessary.

New Orleans, Louisiana, this day of 1989,

v̂ orv. \u J CjcLcnvi

JUDGE JOHN M. WISDOM

- M -

m}h