McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publishing Co. Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of the Petitioner

Public Court Documents

July 21, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publishing Co. Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of the Petitioner, 1994. 495b8f9c-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d85f9341-1b46-4857-a220-b77bbe47bdb8/mckennon-v-nashville-banner-publishing-co-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-the-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

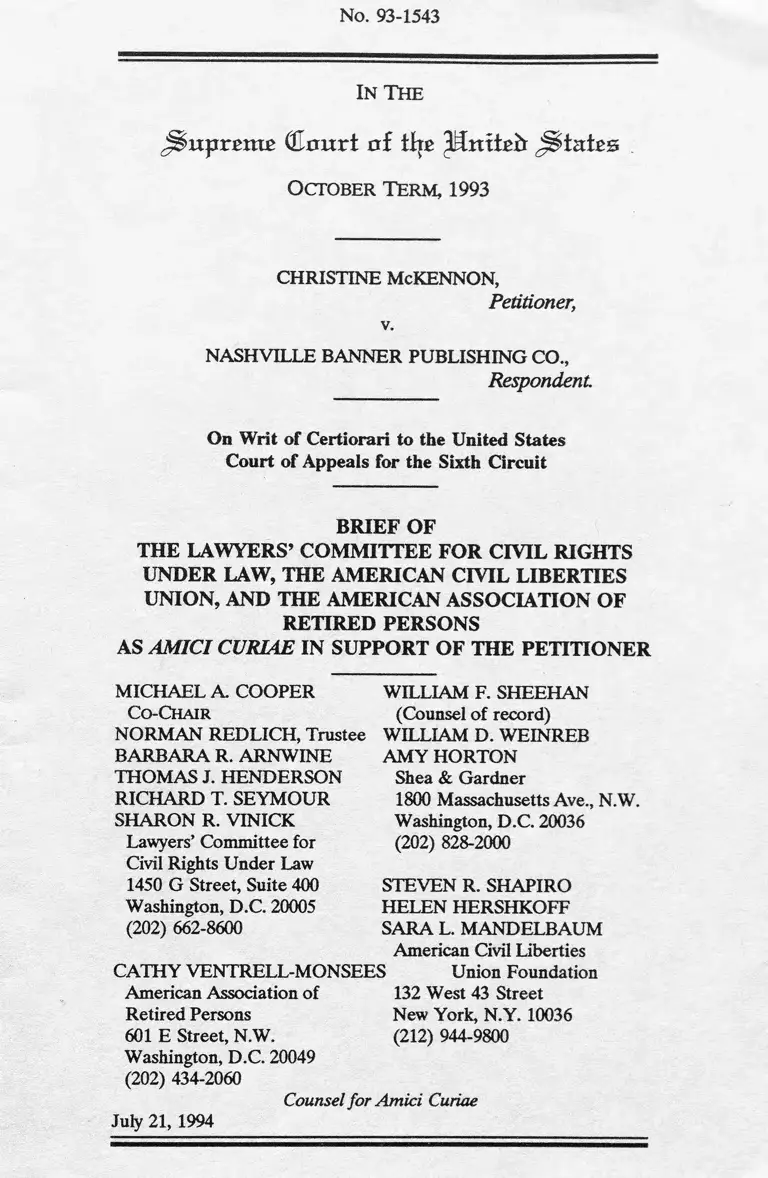

No. 93-1543

In T h e

m p r e r n e C o u r t o f tire ' M t i i i t b S t a t e s

O ctober T erm , 1993

CHRISTINE McKENNON,

Petitioner,

v.

NASHVILLE BANNER PUBLISHING CO.,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF OF

THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION, AND THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF

RETIRED PERSONS

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITIONER

MICHAEL A. COOPER

Co-Chair

NORMAN REDLICH, Trustee

BARBARA R. ARNWINE

THOMAS J. HENDERSON

RICHARD T. SEYMOUR

SHARON R. VINICK

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1450 G Street, Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 662-8600

WILLIAM F. SHEEHAN

(Counsel of record)

WILLIAM D. WEINREB

AMY HORTON

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

STEVEN R. SHAPIRO

HELEN HERSHKOFF

SARA L. MANDELBAUM

American Civil Liberties

CATHY VENTRELL-MONSEES Union Foundation

American Association of 132 West 43 Street

Retired Persons New York, N.Y. 10036

601 E Street, N.W. (212) 944-9800

Washington, D.C. 20049

(202) 434-2060

Counsel for A m ici Curiae

July 21, 1994

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................... iii

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE . . . ___ . . . 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUM ENT......... ...................... 3

ARGUMENT ........................................................... 6

I. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN RULING

THAT PETITIONER WAS NOT INJURED BY

THE VIOLATION OF HER ADEA RIGHTS 6

II. CONGRESS DID NOT INTEND FOR

AFTER-ACQUIRED EVIDENCE OF

EMPLOYEE MISCONDUCT TO DENY ALL

RELIEF FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE

FAIR EMPLOYMENT LAWS ...................... 10

A. The After-Acquired Evidence Rule Is

Inconsistent With the Text of the

Fair Employment Laws ................... 10

B. The After-Acquired Evidence Rule Defeats

the Deterrent and Compensatory Purposes

of the Fair Employment Laws . . . . . . . . . 12

C. The After-Acquired Evidence Rule Has

Been Rejected Under Other Federal

Statutory Schemes .................................... 17

1. Employment-related

statutes .............................................. 17

2. Common-law fault-based

defenses ........................ 22

11

III. AFTER-ACQUIRED EVIDENCE MAY AFFECT

THE REMEDIES AVAILABLE IN

PARTICULAR CASES........... .......... . . . . . . 23

A. Backpay............................................ 26

B. Reinstatement and Front Pay . . . . . . . . . 27

C. Compensatory Damages ........................... 29

D. Liquidated Damages .................... 29

CONCLUSION .......................................... 30

Page

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

ABF Freight System, Inc. v. NLRB,__ U.S.___ ,

114 S. Ct. 843 (1994)............................... 20

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975) .................................. passim

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 (1974)................................... 15

Anastasio v. Schering Corp.,

838 F.2d 701 (3d Cir. 1988) .................... 26

Axelson, Inc., 285 N.L.R.B. 862 (1987) . . . 20

Bartek v. Urban Redevelop. Auth.,

882 F.2d 739 (3d Cir. 1989) .................... 26

Bateman Eichler, Hill Richards, Inc. v. Berner,

472 U.S. 299 (1985)................................. 5, 22

Bigelow v. RKO Radio Pictures, Inc.,

327 U.S. 251 (1946)................................. 27

Bonger v. American Water Works,

789 F. Supp. 1102 (D. Colo. 1992) ......... 25

Carter v. Sedgwick County, Kan.,

929 F.2d 1501 (10th Cir. 1991)................ 28

Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank,

467 U.S. 867 (1984)................................. 6

Duffy v. Wheeling Pittsburgh Steel Corp.,

738 F.2d 1393 (3d Cir.), cert, denied,

469 U.S. 1087 (1984) ............................... 24

Duke v. Uniroyal Inc.,

928 F.2d 1413 (4th Cir.), cert, denied,

112 S. Ct. 429 (1991)..... ........................ 27, 28

Floca v. Homcare Health Servs., Inc.,

845 F.2d 108 (5th Cir. 1988) .................... 28

Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC,

458 U.S. 219 (1982)................................. 12, 13, 16

Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools,

503 U.S.__ , 112 S. Ct. 1028 (1992)___ 29

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976)................................. passim

Page

IV

Gibson v. Mohawk Rubber Co.,

695 F.2d 1093 (8th Cir. 1982).................. 12, 26, 27

Ginsberg v. Burlington Indus., Inc.,

500 F. Supp. 696 (S.D.N.Y. 1980)........... 28

Goldberg v. Bama Mfg. Corp.,

302 F.2d 152 (5th Cir. 1962).................... 19

Gypsum Carrier, Inc. v. Handelsman,

307 F.2d 525 (9th Cir. 1962).................... 18

Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc.,__ U.S. ___,

114 S. Ct. 367 (1993)............................... 29

Hawley v. Dresser Indus., Inc.,

958 F.2d 720 (6th Cir. 1992).................... 24

Hazen Paper Co. v. Biggins,

113 S. Ct. 1701 (1993) ........... ................. 7

Hill v. Spiegel, Inc.,

708 F,2d 233 (6th Cir. 1983).................... 26

Houghton v. McDonnell Douglas Corp.,

627 F.2d 858 (8th Cir. 1980) . .................. 28

International Bhd. of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977).................... ............ 12, 27

John Cuneo, Inc., 298 N.L.R.B. 856 (1990) 20

Lorillard v. Pons, 434 U.S. 575 (1978)___ 6, 19, 26

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co.,

A ll U.S. 273 (1976) ...................... . 11, 27

McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) 25, 27

McKnightv. General Motors Corp.,

908 F.2d 104 (7th Cir. 1990),

cert, denied, 499 U.S. 919 (1991)........... .. 28

Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson,

A ll U.S. 57 (1986)................................... 29

Milligan-Jensen v. Michigan Technological Univ.,

975 F.2d 302 (6th Cir. 1992), cert, dismissed,

114 S. Ct. 22 (1993)................................. 3, 7

Minneapolis, St. P. & S. Ste. M. Ry. v. Rock,

219 U.S. 410 (1929)................................. 18

Page

V

Mt. Healthy City School District Board of

Education v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977) . 4, 8, 9, 23

Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co.

v. Hall, 61A F.2d 248 (4th Cir. 1982) . . . . 18

Omar v. Sea-Land Serv., Inc.,

813 F.2d 986 (9th Cir. 1987).................... 18

Oscar Mayer & Co. v. Evans, 441 U.S. 750 (1979) 12

Perma Life Mufflers, Inc. v. International

Parts Corp., 392 U.S. 134 (1968)............. 5, 22

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989) 4, 8

Rodriguez v. Taylor, 569 F.2d 1231 (3d Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 436 U.S. 913 (1978) . . 12, 15, 28

St. Mary’s Honor Ctr. v. Hicks, 509 U.S.__ ,

113 S. Ct. 835 (1993)............................... 17, 20, 21

Stacey v. Allied Stores Corp., 768 F. 2d 402

(D.C. Cir. 1985)............................... .. 26

Still v. Norfolk &W.Ry., 368 U.S. 35

(1961) . ......................... ................ 5, 17, 29

Summers v. State Farm Mut Auto Ins. Co.,

864 F.2d 700 (10th Cir. 1988).................. passim

Taylor v. Teletype Corp., 648 F.2d 1129

(8th Cir.), cert denied, 454 U.S. 969

(1981) ............................................ 27

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Thurston,

469 U.S. I l l (1985) .................................. 6, 29, 30

United States v. Burke, 112 S. Ct. 1867 (1992) 24, 28

United States Postal Serv. Bd. of Governors v.

Aikens, 460 U.S. 711 (1983) .................... 6

Wallace v. Dunn Constr. Co.,

968 F.2d 1174 (11th Cir. 1992)............... passim

Washington v. Lake Country, III.,

969 F.2d 250 (7th Cir. 1992).................... 7, 25

Welch v. Liberty Machine Works,

1994 U.S. App. LEXIS 10028,

23 F.3d 1403 (8th Cir. Jan. 13, 1994) . . .

Page

24, 25

STATUTES:

Age Discrimination in Employment Act,

29 U.S.C. § 621 et seq. .......................... .. passim

§ 4(a), 29 U.S.C. § 623(a) . _____ _____ _ 6

§ 7(b), 29 U.S.C. § 626(b) . . . . . . . . . . . 11, 29

Civil Rights Act of 1991, adding

Rev. Stat. § 1977A, 42 U.S.C. § 1981a . . 29

Fair Labor Standards Act,

29 U.S.C. § 201 et seq. ...................... 11

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et s e q .............. .. passim

§ 703(a), 42 U.S.C § 2000e-(2)(a) ......... 6

§ 7030, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-(2)(j)___ _ . 24

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

Annual Report of the Director of the Administrative

Office of the United States Courts . . ........... 15

Brunsman, Steve, Resume Fraud, Lying

Not at All Uncommon, Houston Post,

Sept. 26, 1992, at E2 . . _____ . . . ____ _ 15

Crider, Dale, Resume Fraud Complicates Firing

Claims, Nat’l LJ., Dec. 7, 1992, at 17 . . . 15

EEOC: Revised Enforcement Guide on Recent

Developments in Disparate Treatment Theory,

Fair Empl. Prac. Man. (BNA) 405:6915 (1992) passim

Groner, Jonathan, New Defense for Bias Suits:

Attack, Fulton County Daily Report,

Mar. 12, 1993, at 1 ................................... 14

Kelly, Dennis, Lies Part of Students’ Lives,

USA Today, Nov. 13, 1992, at 1 ............. 14

Labich, Kenneth, The New Crisis in Business

Ethics, Fortune, Apr. 20, 1992, at 167 . . . 14

vi

Page

Vll

Maddux, David A., & Douglas A. Barritt,

Employees’ Lies Can Backfire:

Misconduct May Bar Employment Suits,

Nat’l LJ., May 10, 1993, at 25 ................ 14

Many Falsify Credentials, Qualifications,

Atlanta Constitution,

May 11, 1992, at B 5 ................................. 14

Mesritz, George C .,"'After-Acquired" Evidence

of Pre-Employment Misrepresentations:

An Effective Defense Against Wrongful

Discharge Claims,

18 Employee Rel. LJ. 215 (1992) ............ 14

Rigdon, Joan E., Deceptive Resumes Can Be

Door-Openers But Can Become an Employee’s

Undoing, Wall St. J., June 17, 1992, at B1 15

White, Rebecca H., & Robert D. Brussack,

The Proper Role of After-Acquired Evidence in

Employment Discrimination Litigation,

35 B.C. L. Rev. 49 (1993)........................ 3

Witus, Morley, Defense of Wrongful Discharge

Suits Based on an Employee’s Misrepresentations,

69 Mich. B.J. 50 (1990)

Page

14

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE1

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

is a nonprofit organization that was established at the

request of the President of the United States in 1963 to

involve leading members of the bar throughout the country

in the national effort to ensure civil rights to all Americans.

The disposition of the case at bar, arising under the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act ("ADEA"), 29 U.S.C. §

621 et seq., will affect the availability of relief to victims of

unlawful employment practices under other federal statutes,

including Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e et seq., and other antidiscrimination statutes. The

Lawyers’ Committee has represented, and has assisted other

lawyers in representing, numerous plaintiffs in administrative

proceedings and lawsuits under Title VII in the lower courts.

See, e.g., Lewis v. Bloomsburg Mills, Inc., 773 F.2d 561 (4th

Cir. 1985); Payne v. Travenol Labs., Inc., 673 F.2d 798 (5th

Cir. 1982).

The Lawyers’ Committee has also represented parties

and participated as amicus curiae in ADEA and Title VII

cases before this Court. See, e.g., Gilmerv. Interstate!Johnson

Lake Corp.,__ U.S.___ , 112 S. Ct. 1647 (1991); Landgraf

v. USI Film Prods.,__ U.S.___ , 114 S. Ct. 1483 (1994); St.

Mary’s Honor Ctr. v. Hicks,__ U .S.__ , 113 S. Ct. 2742

(1993); Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio, 490 U.S. 642

(1989). The Committee appeared most recently as an

amicus in ABF Freight System, Inc. v. NLRB,__ U.S.___ ,

114 S. Ct. 843 (1994), in which the petitioner contended that

the "after-acquired evidence" rule established in cases arising

under Title VII should curb the remedial powers of the

NLRB.

1 The parties’ written consents to the filing of this brief are being filed

today with the Clerk of the Court.

The Lawyers’ Committee is interested in this case

because the lower courts’ misapplication of the after-

acquired evidence rule is substantially harming the

enforcement of Title VII as well as the ADEA, and is

materially reducing the incentive of employers to eliminate

discrimination.

The American Civil Liberties Union ("ACLU") is a

nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with nearly

300,000 members dedicated to preserving and enhancing the

civil rights and civil liberties embodied in the Constitution

and civil rights laws of this country. In particular, the ACLU

has long been involved in the effort to eliminate racial

discrimination from our society. The Women’s Rights

Project of the ACLU Foundation was established to work

toward the elimination of gender-based discrimination under

law. In pursuit of that goal, the ACLU has represented

parties and participated as amicus curiae in numerous anti-

discrimination cases before the Court, including, during the

last ten years, International Union, UA W v. Johnson Controls,

Inc., 499 U.S. 187 (1991) and EEOC v. Arabian American Oil

Co., 499 U.S. 244 (1991).

The American Association of Retired Persons

("AARP") is a nonprofit membership organization of persons

age 50 and older that is dedicated to addressing the needs

and interests of older Americans. More than one-third of

AARP’s thirty-three million members are employed, most of

whom are protected by the ADEA and Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. One of AARP’s primary objectives is to

strive to achieve dignity and equality in the workplace

through positive attitudes, practices, and policies towards

work and retirement. In pursuit of this objective, AARP has

participated as amicus curiae in numerous discrimination

cases before this Court and the federal courts of appeals,

and filed an amicus brief in support of the grant of certiorari

in this case.

- 2 -

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The question presented in this case is whether Congress

intended the courts to provide a remedy for unlawful

employment discrimination visited on employees who would

not have been hired, or who would have been fired, for some

legitimate reason unknown to the employer when it

committed its discriminatory act but learned in time to be

offered as a defense in the employee’s suit. In the typical

case the subsequently learned legitimate reason (or "after-

acquired evidence") is that the employee obtained his or her

job through some kind of deceit or, as here, has engaged in

on-the-job misconduct warranting dismissal.2 The role

Congress intended after-acquired evidence to play in these

cases must be found in the language and purposes of the

ADEA. The court below, however, without mentioning

either the text or any perceived policy of the Act, denied all

relief on the theoiy that respondent’s violation of the Act

was not the legal cause of petitioner’s injury.

The lower court’s ruling springs from the Tenth

Circuit’s decision in Summers v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins.

Co., 864 F.2d 700, 708 (10th Cir. 1988).3 There the full

extent of an employee’s falsification of company records

came to light only after he filed an ADEA and Title VII suit

against his employer for dismissing him on the basis of

religion and age. The Tenth Circuit wrote that, although the

previously unknown falsifications "could not have been a

-3 -

2 See Rebecca H. White & Robert D. Brussack, The Proper Role o f After-

Acquired Evidence in Employment Discrimination Litigation, 35 B.C. L.

Rev. 49, 50 nn.3-4, 57 & n.27 (1993) (collecting cases).

3 The Sixth Circuit adopted Summers in Johnson v. Honeywell Info. Sys.,

Inc. 955 F.2d 409, 415 (6th Cir. 1992), and followed it in Milligan-Jensen

v. Michigan Technological Univ., 975 F.2d 302, 304 (6th Cir. 1992), cert,

dismissed, 114 S.Ct. 22 (1993), and in the decision below. Pet. App. 5a-

7a.

- 4 -

‘cause’ or ‘reason’ for [plaintiffs] discharge," it would be

"utterly unrealistic" to ignore them and they should be

"considered in determining what relief, or remedy, is

available to [plaintiff]." 864 F.2d at 704, 708. The Tenth

Circuit did not, however, undertake that consideration in

light of the text or purposes of the fair employment laws.

Instead it cited this Court’s decision in Ml Healthy City

School District Board of Education v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274

(1977), for the proposition that, if a worker who had

engaged in so-called resume fraud would not have been

hired (or, in the case of on-the-job misconduct, would have

been fired) had the true facts been known, then he or she

suffers no legal injury from being discharged for

discriminatory reasons.

The Tenth Circuit misread ML Healthy. That decision

established that, when an employer bases an employment

decision on both legitimate and illegitimate reasons, it can

avoid liability if it can prove that it would have made the

same decision based on the legitimate reason alone. As the

Court made clear in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S.

228, 252 (1989), however, the proffered legitimate reason

must have actually motivated the employer at the time it

took the disputed action.

In this case, as in all after-acquired evidence cases, the

employer by definition was unaware of, and thus could not

have been motivated by, the after-acquired legitimate reason

at the time it committed its discriminatory acts. Hence the

forbidden conduct alleged in the complaint and assumed by

the courts below - the denial of raises, harassment, and

ultimate discharge of petitioner because of her age -- caused

petitioner to suffer precisely the type of injury the Act was

designed to redress: the deprivation of wage earning

opportunities because of discrimination.

Accordingly, as the Eleventh Circuit recognized in

Wallace v. Dunn Constr. Co., 968 F.2d 1174 (11th Cir. 1992),

the question the court below should have addressed is

whether, despite the existence of a violation, Congress meant

for victims of employment discrimination to be denied all

relief automatically because of their own misconduct. The

Eleventh Circuit correctly ruled that Congress could not have

intended that result because, as a complete bar to relief, the

after-acquired evidence rule hinders rather than advances the

deterrent and compensatory purposes of the fair employment

laws by allowing intentional discrimination to go without

sanction, leaving victims worse off than if no violation had

occurred, creating an inducement for employers to engage in

reprehensible employment practices, and discouraging

discrimination victims from enforcing their rights.

Our view is reinforced by many decisions, including Still

v. Norfolk & W Ry., 368 U.S. 35 (1961), refusing to recognize

after-acquired evidence of employee misconduct as a bar to

all remedies under other statutes authorizing employment-

related relief, and by Bateman Eichler, Hill Richards, Inc. v.

Berner, 472 U.S. 299 (1985), and Perma Life Mufflers, Inc. v.

International Parts Corp., 392 U.S. 134 (1968), refusing to

recognize common law fault-based defenses to violations of

federal statutes Congress intended would be enforced by

private actions.

Although after-acquired evidence cannot bar all relief,

the proper application of the remedial principles embodied

in the fair employment laws suggests that it may limit the

availability of make-whole relief in particular cases. The

victims of a discriminatory employment decision are not

entitled to relief beyond the point when the same decision

would have been made for nondiscriminatory reasons.

Accordingly, after-acquired evidence of misconduct may

serve in particular cases to terminate backpay and certain

compensatory damages sooner than would otherwise be the

- 5 -

- 6 -

case, and to bar reinstatement and front pay entirely. It

should not, however, affect the availability of punitive

damages, which are awarded solely on the basis of the

employer’s understanding of the unlawfulness of his own

conduct.

ARGUMENT

I. THE LOWER COURT ERRED IN RULING THAT

PETITIONER WAS NOT INJURED BY THE VIOLATION OF

HER ADEA RIGHTS

Section 4(a) of the ADEA, 29 U.S.G. § 623(a), together

with § 703(a) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-(2)(a), make it

unlawful for an employer —

to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual or otherwise discriminate against any

individual with respect to his compensation,

terms, conditions, or privileges of employment,

because of such individual’s

age, race, religion, sex, or national origin. (Emphasis

added).4 As the words "because o f plainly indicate, the

critical inquiry at the liability phase of an individual disparate

treatment case "is the reason for a particular employment

decision." Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank, 467 U.S. 867,

8765 (1984). That presents a question of historical fact,

requiring a determination of "what the state of a man’s mind

at a particular time is." United States Postal Serv. Bd. of

Governors v. Aikens, 460 U.S. 711, 716 (1983) (internal

quotation marks and citation omitted). If the employment

4 As a rale, interpretations of Title VII apply with equal force to the

ADEA, "for the substantive provisions of the ADEA ‘were derived in

haec verba from Title VII.’" Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Thurston, 469

U.S. I l l , 121 (1985) (quotingLorillard v. Pons, 434 U.S. 575,584 (1978)).

- 7 -

decision at issue was made "because of' a prohibited factor,

the statute has been violated, for "liability depends on

whether the protected trait (under the ADEA, age) actually

motivated the employer’s decision." Hazen Paper Co. v.

Biggins, 113 S. Ct. 1701, 1706 (1993) (emphasis added).

Since by definition after-acquired evidence of

misconduct is unknown to the employer at the time of the

challenged employment decision, that evidence cannot

possibly have been the reason for the decision. Hence it

cannot bear on whether the employer has committed an

unlawful employment practice. Indeed, none of the courts

that has denied all relief on the basis of such evidence,

including the courts below, appears to take a contrary view.5

Rather, these courts hold that after-acquired evidence

mandates the denial of all relief notwithstanding the

existence of a statutory violation on the theory that the

violation was not the legal cause of the employee’s injuries.

In Milligan-Jensen, for example, the Sixth Circuit "regarded]

the problem as one of causation" and adopted the view that,

"if the plaintiff would not have been hired, or would have

been fired, if the employer had known of the falsification [on

her job application], the plaintiff suffered no legal damage by

being fired." 975 F.2d at 304-5. And in the instant case the

Sixth Circuit wrote that, "because it was undisputed that

5 The courts below ruled as they did on the assumption that petitioner

was "subjected to age discrimination." Pet. App. 13a, 3a. See also

Milligan-Jensen v. Michigan Technological Univ., 975 F.2d 302, 305 (6th

Cir. 1992) (whether plaintiff was discriminated against was "irrelevant");

Summers v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Inc. Co., 864 F.2d 700, 708 (10th Cir.

1988) ("[WJhile such after-acquired evidence cannot be said to have been

a ‘cause’ for [plaintiffs] discharge in 1982, it is relevant to [his] claim of

‘injury,’ and does itself preclude the grant of any present relief or

remedy."); Washington v. Lake County, III., 969 F.2d 250, 255 (7th Cir.

1992) ("[The defendant] allows us to assume that it discriminated against

[plaintiff) because of his race.").

- 8 -

[petitioner] was guilty of misconduct, prior to her discharge,

that would, if known by [respondent], have caused her

discharge * * * [petitioner] did not suffer injury from the

claimed violation" of her ADEA rights. Pet. App. 3a. By

this the court presumably meant that, because petitioner

would have been discharged lawfully had her misconduct

been known, the unlawful discharge was not the legal cause

of her injuries.

The lower court’s causation theory was first articulated

by the Tenth Circuit in Summers, which mistakenly found it

warranted by this Court’s decision in Mt. Healthy City School

District Board of Education v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977).6

In Mt. Healthy the Court held that an employer who bases an

employment decision on a mixture of legitimate and

illegitimate motives can avoid liability by showing "that it

would have reached the same decision" based on the

legitimate reasons alone. 429 U.S. at 287. In Price

Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989), the Court

adopted the same test of liability in mixed-motive cases

arising under Title VII, but in so doing firmly rejected the

idea that an employer can prevail by offering a legitimate

reason for its decision that it did not discover until later. As

Justice Brennan explained for the plurality:

An employer may not * * * prevail in a mixed-

motive case by offering a legitimate and sufficient

reason for its decision if that reason did not

motivate it at the time of the decision. * * * The

very premise of a mixed motive case is that a

legitimate reason was present * * *.

Id. at 252. See also id. at 260-61 (White, J., concurring in

the judgment); id. at 266-67 (O’Connor, J., concurring in the

6 See Summers, 864 F.2d at 705-06, 707 n.3 (describing Mt. Healthy as

"the linchpin case" in this area).

- 9 -

judgment).

Accordingly, mixed-motive cases are no help to

employers in after-acquired evidence cases, in which it is

always undisputed that the legitimate reason offered for the

employer’s action was not known to the employer at the time

of, and hence could not actually have motivated, that action.

It follows that, in this case, the after-acquired legitimate

reason for petitioner’s discharge cannot alter the conclusion

that age discrimination caused her to lose the wages she

would have earned in the absence of respondent’s violation

of the Act. The loss of those wages is precisely the kind of

injury that the fair employment laws were designed to

redress.

Apart from its reliance on Summers, the lower court

offered no explanation for its unorthodox theory of

causation. In particular, it made no attempt to explain how

its concept of causation would promote or even be consistent

with the purposes of the ADEA. The court’s aim was not to

implement the congressional directive that the employee be

made no worse off as a result of discrimination, see

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 421 (1975)

(quoting 118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972); cf. Mt. Healthy, 429

U.S. at 285-86, but rather to apply the general equitable

principle that a plaintiff be made no better off as a result of

his or her own misconduct. In the end its conclusion

reflected not so much a rule of causation as a policy decision

preferring one wrongdoer over another.7

7 Strictly speaking, the lower court’s causation theory would relieve

employers of liability whenever any legitimate reason for firing or not

hiring the employee, including reasons having nothing to do with

employee misconduct, surfaced after the employer’s discriminatory act -

- such as the discoveiy that the employer had mistakenly given the

employee a passing grade on the job application test, or that over time,

unbeknownst to all, the employee’s eyesight had deteriorated below

standards required by the job. As petitioner demonstrates in her brief.

- 10 -

Our quarrel with the lower court’s approach is not that

it gives weight to the employee’s misconduct, but that it gives

it exclusive weight. Instead of treating the misconduct as a

factor to be considered in shaping an equitable remedy

consistent with the statutory purposes, it treats it as a basis

for denying causation and therefore liability. That approach

disregards altogether that discriminatory employment actions

have occurred which caused, in any ordinary sense, economic

loss to the employee ~ the veiy situation Congress sought to

redress. The better approach would have been to

acknowledge that the employer committed violations that

ordinarily would call for complete relief and then consider

whether Congress intended a different result on account of

the after-acquired evidence of employee misconduct. We

turn now to that question.

II. CONGRESS DID NOT INTEND FOR

AFTER-ACQUIRED EVIDENCE OF EMPLOYEE

MISCONDUCT TO DENY ALL RELIEF FOR

VIOLATIONS OF THE FAIR EMPLOYMENT LAWS

A. The After-Acquired Evidence Rule Is Inconsistent With

The Text of The Fair Employment Laws

The lower court’s ruling effectively excludes numerous

employees from the coverage of the fair employment laws.

It deems these workers incapable of suffering injury on

account of unlawful discrimination regardless of the nature

of the discrimination or its consequences for the workers and

for society. In this case, for example, the court held that,

because petitioner copied confidential records, she did not

suffer a redressable injury even assuming the truth of her

the limitless sweep of that rule of causation would eviscerate the fair

employment laws and we do not read the Sixth Circuit to have adopted

it. Rather, along with other lower courts, the Sixth Circuit’s rule seems

rooted in notions of morality as well as causation, and hence restricted

to cases of after-acquired evidence of employee misconduct.

-11 -

allegations that respondent denied her raises, harassed her,

and ultimately dismissed her on the basis of age.

Nothing in the language of the fair employment laws

suggests that Congress meant to exclude from their

protection workers who have obtained their jobs through

some kind of deceit or retained them despite having engaged

in some form of misconduct unknown to the employer. The

liability provisions of those statutes make it unlawful to

discriminate against "any individual" on the basis of

prohibited factors. This Court has given these words their

ordinary, everyday meaning, holding that Title VII makes no

"exception for any group of particular employees."

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co., 427 U.S. 273, 283

(1976).

The remedial provisions of the fair employment laws

likewise contain no suggestion that Congress meant to deny

a remedy to workers who conceal disqualifying

characteristics. Once a violation of the Act is established,

"[ajmounts owing * * * as a result," such as back wages and

benefits, are to be treated as "unpaid minimum wages or

unpaid overtime compensation" under the Fair Labor

Standards Act ("FLSA"). 29 U.S.C. § 626(b). If the

violation is willful, the plaintiff is entitled to an additional

equal amount as liquidated damages. Id., incorporating by

reference 29 U.S.C. § 216(b). In addition, ADEA courts are

authorized to

grant such legal or equitable relief as may be

appropriate to effectuate the purposes of this

chapter, including without limitation judgments

compelling employment, reinstatement or

promotion, or enforcing the liability for amounts

- 12 -

deemed to be unpaid minimum wages or unpaid

overtime compensation under this section. Id.

Although this language accords district courts a

measure of discretion, Congress granted that discretion "to

allow the most complete achievement of the objectives of

[the statute] that is attainable under the facts and

circumstances of the particular case." Franks v. Bowman

Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747, 770-71 (1976) (Title VII). Hence

in fashioning a remedy "a court has not merely the power

but the duty to render a decree which will so far as possible

eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar

like discrimination in the future." Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC,

458 U.S. 219, 233 (1982) (internal quotations omitted) (Title

VII); Albemarle Paper, 422 U.S. at 421 (discretionary power

to award backpay granted "to make possible the fashioning

of the most complete relief possible")(intemal quotes and

brackets omitted) (Title VII).

B. The After-Acquired Evidence Rule Defeats the

Deterrent and Compensatory Purposes of the Fair

Employment Laws

The ultimate objective of both the ADEA and Title

VII is the eradication of discrimination in the workplace.

Oscar Mayer & Co. v. Evans, 441 U.S. 750, 756 (1979)

(ADEA); Rodriguez v. Taylor, 569 F.2d 1231, 1236 (3d Cir.

1977) (ADEA); see also Albemarle Paper, 422 U.S. at 415.

Both statutes seek to achieve that goal through policies of

deterrence and restoration.8 Make-whole relief (such as

backpay) is essential to both policies. As this Court observed *

* See Albemarle Paper Co., 422 U.S. at 417; International Bhd. of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 364 (1977) (Title VII); Gibson

v. Mohawk Rubber Co., 695 F.2d 1093,1097 (8th Cir. 1982) (ADEA seeks

"to make persons whole for injuries suffered as a result of unlawful

employment discrimination").

- 13 -

in Albemarle Paper, "[i]t is the reasonably certain prospect of

a backpay award that ’provide[s] the spur or catalyst which

causes employers and unions to self-examine and to self-

evaluate their employment practices and to endeavor to

eliminate, so far as possible, the last vestiges’" of their

discriminatory practices. 422 U.S. at 418-419 (citation

omitted). And in Ford Motor Co. this Court said that forcing

an employer who has broken the law to pay the wages and

benefits lost by the victim of his discrimination gives him a

powerful incentive to avoid future violations, for "paying

backpay damages is like paying an extra worker who never

came to work." 458 U.S. at 229. These decisions recognize

that the deterrent and make-whole purposes of the fair

employment laws are mutually reinforcing, and that

compensating victims of discrimination is critical to both, "for

requiring payment of wrongfully withheld wages deters

further wrongdoing at the same time that their restitution to

the victim helps make him whole." Franks, 424 U.S. at 786

(Powell, J., concurring and dissenting).

The rule adopted by the court below, insulating lawless

employers from the Act’s remedial scheme, hinders rather

than advances the restorative and deterrent policies of the

ADEA and Title VII. The compensation-denying result of

the rule is most immediately obvious, but its adverse effect

on deterrence is no less severe. As the Eleventh Circuit

observed in Wallacev. Dunn Constr. Co., 968 F.2d 1174,1180

(11th Cir. 1992), the after-acquired evidence rule

does not encourage employers to eliminate

discrimination. Rather, it invites employers to

establish ludicrously low thresholds for

‘legitimate’ termination and to devote fewer

resources to preventing discrimination because

[the rule] gives them the option to escape all

liability by rummaging through an unlawfully-

discharged employee’s background for flaws and

- 14 -

then manufacturing a ‘legitimate’ reason for the

discharge that fits the flaws in the employee’s

background.

The concerns expressed by the Wallace court are not

fanciful. Employers, human resource professionals, and their

attorneys are by now fully informed of the potential for the

use of after-acquired evidence to avoid liability for

discrimination.9 Moreover, employers have reason to

believe that an intensive investigation of an ex-employee’s

job application may well reveal some misstatement of fact,

even in the case of employees who have performed

satisfactorily since their hire.10

9 See, e g., Jonathan Groner, New Defense for Bias Suits: Attack, Fulton

County Daily Report [for local attorneys], Mar. 12, 1993, at 1 (The

doctrine of after-acquired evidence "permits [an employer] to trump

discrimination charges by using dirt about an employee dug up after his

termination"); George D. Mesritz, "After-Acquired" Evidence o f Pre-

Employment Misrepresentations: An Effective Defense Against Wrongful

Discharge Claims, 18 Employee Rel. LJ. 215, 224 (1992) (instructing

employers to subpoena the ex-employee’s physicians and mental health

care professionals for evidence of illicit drug use, and to contact courts

located where the employee has resided); David A. Maddux & Douglas

A. Barritt, Employees ’Lies Can Backfire: Misconduct May Bar Employment

Suits, Nat’l LJ., May 10, 1993, at 25, 29 ("[T]he employer * * * should

leave no stone unturned in trying to identify any misrepresentations or

misconduct by the employee."); Morley Witus, Defense of Wrongful

Discharge Suits Based on an Employee’s Misrepresentations, 69 Mich. BJ.

50, 51 (1990) ("In defending discrimination and retaliation claims, again

the focus should not be on the employer’s motive for discharging the

employee.").

10 See, e.g.,Many Falsify Credentials, Qualifications, Atlanta Constitution,

May 11, 1992, at B5 ("resume fraud is rampant among job seekers");

Kenneth Labich, The New Crisis in Business Ethics, Fortune, April 20,

1992, at 167, 176 (surveys of Americans between 18 and 30 years old

show that "between 12% and 24% say they included false information on

their resumes"); Dennis Kelly, Lies Part o f Students’ Lives, USA Today,

Nov. 13, 1992, at 1 (33% of high school and college students surveyed

- 15 -

The lower court’s rule also impedes the deterrent aims

of the fair employment laws by discouraging actions by

private litigants, whom Congress has cast in the role of

private attorneys general.11 The after-acquired evidence

rule invites employers to conduct a wide-ranging and

potentially humiliating investigation into the personal and

professional background of every claimant. The inevitable

result will be that employees who would otherwise challenge

unlawful employment practices may tolerate them instead.

That is especially true of employees who are aware of a

blemish on their records that could surface during discovery,

but even employees with nothing to hide might reasonably

indicated that they are willing to he on a resume); Steve Brunsman,

Resume Fraud, Lying Not at All Uncommon, Houston Post, Sept. 26,1992,

at E2; Joan E. Rigdon, Deceptive Resumes Can Be Door-Openers But Can

Become an Employee’s Undoing, Wall St. J., June 17, 1992, at B l; Dale

Crider, Resume Fraud Complicates Firing Claims, Nat’l L J., Dec. 7, 1992,

at 17 ("In today’s employment market, resume fraud is an increasingly

serious problem. * * * One in 10 employers reportedly has discovered

applicants lying on resumes, and a close examination undoubtedly would

uncover many more instances of applicants misrepresenting their

qualifications.").

11 In Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 45 (1974), the Court

said that "the private right of action remains an essential means of

obtaining judicial enforcement of Title VII” and "the private litigant not

only redresses his own injury but also vindicates the important

congressional policy against discriminatory employment practices." The

same is true under the ADEA. Rodrigue: v. Taylor, 569 F.2d at 1245

(granting attorney’s fees to ADEA plaintiff and noting that

"congressionally approved awards are designed to encourage private

enforcement of individual rights and to deter socially harmful conduct").

The Director of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts has

reported that a total o f 10,771 private fair employment lawsuits were filed

in FY 1992, compared with only 440 filed by government enforcement

agencies. Annual Report of the Director of the Administrative Office of

the United States Courts, Table C2, Appendix I, at 179 (Sept. 30, 1992).

- 16 -

decide to abide unlawful practices rather than subject

themselves to intrusive personal investigations. The end

result will harm not only the employees in question but also

their colleagues in the workplace, who benefit each time an

employee vindicates the public policy against employment

discrimination.

Finally, the rule adopted below, legitimatizing the

employer’s resort to discovery into the employee’s

background, will further snarl the litigation process and shift

the focus from issues important under the fair employment

laws to collateral matters. This Court has already deplored

the slow pace of Title VII lawsuits, in which delays "are now

commonplace, forcing the victims of discrimination to suffer

years of underemployment or unemployment before they can

obtain a court order awarding them the jobs unlawfully

denied them." Ford Motor Co., 458 U.S. at 228. The court

of appeals’ rule will make matters worse. Both prospective

plaintiffs and their attorneys, who frequently handle

discrimination claims on a contingency basis, will be

discouraged from running the litigation gantlet, and as

enforcement efforts are weakened so is the overall deterrent

force of the Act. The adverse impact on deterrence is bound

to increase as more violations of the Act go unpunished, and

the proliferation of cases in which employers offer after-

acquired evidence to avoid paying for their discriminatory

actions shows that the court of appeals’ rule may in fact

immunize outlaw employers in a significant number of cases.

In sum, the after-acquired evidence rule finds no

support in either the text or the policies of the fair

employment laws. It wrongly insulates discriminatory

employers from responsibility and thereby diminishes their

"incentive to shun practices of dubious legality,” Albemarle

Paper, 422 U.S. at 417; it leaves victims of intentional

discrimination uncompensated; it will chill private

enforcement actions; it will encourage reprehensible conduct

- 17 -

by employers; and it will contribute to litigation complexity

and delay. By contrast, what can be said on behalf of the

after-acquired evidence rule -- that it punishes employees

who have gained their jobs through deceit or retained them

despite undiscovered on-the-job misconduct -- is irrelevant to

the ADEA and Title VII. Those laws were not enacted to

adjust employer-employee relationships in accord with all of

the rights and duties that may flow between them. Cf St.

Mary’s Honor Center v. Hicks, 509 U.S.__ , __ , 113 S. Ct.

2742, 2754 (1993) ('Title VII is not a cause of action for

peijury; we have other civil and criminal remedies for that.").

C. The After-Acquired Evidence Rule Has Been Rejected

Under Other Federal Statutory Schemes

Two lines of decisions, one dealing particularly with

laws that require employers to compensate workers for

employment-related injuries and the other broadly defining

the role of fault-based defenses to federal statutory causes of

action, have concluded that achievement of Congress’s will

takes priority over competing policies based on the plaintiffs

misconduct.

1. Employment-related statutes. The after-acquired

evidence of misconduct issue has arisen under a variety of

federal statutes governing employer-employee relations, and

over the years the courts and agencies responsible for

implementing those statutes have devised rules for handling

that issue in light of the statutory policies at stake. The

general rule to have emerged is that after-acquired evidence

cannot bar a claim altogether but may limit the availability

of particular forms of relief.

In Still v. Norfolk & W. Ry., 368 U.S. 35 (1961), this

Court held that a railroad cannot escape its obligation under

the Federal Employers’ Liability Act to pay damages for

personal injuries negligently inflicted upon a worker by

- 18 -

proving that the injured worker had obtained his job by

making material misrepresentations on which the railroad

relied in hiring him. The Court thereby effectively overruled

Minneapolis, St P. & S. Ste. M. Ry. v. Rock, 279 U.S. 410

(1929), which had denied such relief on public policy grounds

to an injured worker who obtained employment through

means that struck the Court as particularly outrageous.12

The Court wrote in Still that "considerations of public policy

of the general kind relied upon by the Court in Rock cannot

be permitted to encroach further upon the special policy

expressed by Congress in the Act," which is that workers be

compensated for their injuries. Id. at 44-45. Hence, "the

status of employees who become such through other kinds of

fraud * * * must be recognized for purposes of suits under

the Act." Id. at 45. The Court noted, however, that

application fraud might serve to limit relief in appropriate

cases, such as where the employee concealed evidence of a

pre-existing injury for which he later sought compensation

from the railroad. Id. at 46 n.14.13

12 The plaintiff in Rock obtained his job after being rejected for health

reasons by reapplying under a false name and enlisting a stand-in for the

medical exam. Although Still did not overrule Rock in so many words,

it held th at"Rock must be limited to its precise facts" and suggested that

those facts "may never arise again." 368 U.S. at 44.

13 The lower federal courts have reached the same conclusion regarding

after-acquired evidence of misconduct in cases arising under the Jones

Act and the Longshoremen’s and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act

("LHWCA"). See Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co. v. Hall, 61A

F.2d 248, 252 (4th Cir. 1982) (holding that the "specific legislative policy

favoring compensation of injured employees" embodied in the LHWCA

"overrides the general considerations surrounding an allegedly fraudulent

formation of the employment relationship"); O m ar\. Sea-Land Serv., Inc.,

813 F.2d 986, 990 (9th Cir. 1987) (Jones Act); Gypsum Carrier, Inc. v.

Handelsman, 307 FJ2d 525, 530-31 (9th Cir. 1962) (same).

- 19 -

In Goldberg v. Bama Manufacturing Corp., 302 F.2d 152

(5th Cir, 1962), decided under the FLSA, an employee

discharged for having reported wage and hour violations was

discovered to have engaged in serious job-related

misconduct, including forgery of production slips, theft, and

time clock abuses.14 The Department of Labor, charged

with administering the statute, argued that reinstatement and

backpay were nonetheless appropriate. The court viewed the

case as presenting "a collision of two strong policies, one

against condoning violations of the Act and the other against

forcing an employer to keep unfit employees." Id. at 156. It

reasoned that the congressional goal of eliminating violations

would be frustrated by a rule mandating the denial of all

relief, since ”[t]he purposes of the [FLSA] require that

employees throughout the country feel confident that they

may bring a complaint to the Department of Labor without

being penalized by their employers," and denying all relief

would necessarily leave other workers with the impression

that the employer "discharged an employee in violation of

the Act and the district court allowed the employer to get

away with it scot free." Id. Yet the court also acknowledged

"half a dozen reasons why [the plaintiff] should have been

discharged." Id. at 154. It concluded that "the conflicting

policies present in this case would best be balanced" by an

award requiring reimbursement but denying reinstatement.

Id. at 156.

The National Labor Relations Board has similarly

concluded that the national labor policy is best served by a

rule allowing after-acquired evidence of employee

14 The Goldberg decision is particularly significant because it was part of

the body of case law interpreting the FLSA’s remedial provisions that

existed when Congress was drafting the ADEA. This Court has acknowl

edged that Congress was aware of those judicial interpretations and

meant to incorporate them into the ADEA. LoriUard v. Pons, 434 U.S.

at 580-81.

- 2 0 -

misconduct to limit relief but not bar it entirely. In Axelson,

Inc., 285 N.L.R.B. 862 (1987), two strikers who were unlaw

fully deprived of their jobs had previously engaged in strike

misconduct which, if known by their employer, would have

resulted in their lawful discharge. Seeking to "balance [its]

responsibility to remedy unfair labor practices and [its] policy

of discouraging strike misconduct," the Board denied rein

statement but awarded backpay up until the date the em

ployer acquired knowledge of the misconduct (and would

legitimately have discharged the workers). Id. at 866 & n .ll.

Similarly, in John Cuneo, Inc., 298 N.L.R.B. 856 (1990), the

Board considered the case of a worker who would not have

been hired but for a material falsification on his resume, but

who, absent discrimination, would have remained employed

until the falsification was discovered. Once again seeking to

"balance [its] responsibility to remedy the [employer’s] unfair

labor practice against the public interest in not condoning

[the worker’s] falsification of his employment application,"

the Board denied reinstatement but ordered backpay up un

til the date that the falsification was discovered. Id. at 856.

This Court’s recent ruling in ABF Freight System, Inc.

v. N LRB ,__ U .S.___ _, 114 S. Ct. 835 (1994), suggests that

it would uphold these Board decisions. There the Court

upheld the Board’s grant of reinstatement and back pay

relief to a union supporter who had been fired because of

anti-union animus but who had lied to his employer and had

perjured himself in the Board’s administrative proceedings.

The Court rejected a rule barring all individual relief where

employee misconduct or perjury had occurred, citing St.

Mary’s Honor Ctr., 113 S.Ct. at 2754, as supporting the

Board’s decision to rely on "‘other civil and criminal

remedies’ for false testimony, rather than a categorical

exception to the familiar remedy of reinstatement." 114 S.

Ct. at 840.

- 21 -

The Court’s discussion of the policies at stake in that

case applies equally to cases brought under the ADEA and

Title VII.15 It ruled that the Board had not abused its

discretion in awarding relief because (1) the Board was

under no obligation to adopt a rigid rule foreclosing relief in

all such cases; (2) it could not "fault the Board’s conclusion^

that [the employee’s misconduct] was ultimately irrelevant to

whether antiunion animus actually motivated his discharge";

and (3) it could not fault the Board’s conclusion that

"ordering effective relief in a case of this character promotes

a vital public interest"; and (4) a rule denying all relief

because of employee misconduct "might force the Board to

divert its attention from its primaiy mission and devote

unnecessary time and energy to resolving collateral disputes

about credibility." Id.

Finally, the EEOC has determined that the national

goal of equal employment opportunity would best be served

by a rule that after-acquired evidence of misconduct cannot

bar relief entirely but may limit the availability of particular

remedies. Under the EEOC’s Revised Enforcement Guide,

an employer may be shielded from an order of reinstatement

and from backpay accruing after the discovery of the

legitimate reason for discharge. The employer is still subject,

however, to awards of backpay and compensatory damages

covering the period of time up to the discovery of the

misconduct, as well as punitive damages. EEOC: Revised

Enforcement Guide on Recent Developments in Disparate

13 Albemarle Paper held that Title VIPs "backpay provision was expressly

modeled on the backpay provisions of the National Labor Relations Act"

and that Congress intended the courts to follow the Board’s practices in

making backpay awards. 422 U.S. at 419-20 and 422 N.16.

- 2 2 -

Treatment Theory, Fair Empl. Prac. Man. (BNA) 405:6915,

6926-27 (1992) ("EEOC Revised Enforcement Guide").

2. Common-law fault-based defenses. The second line

of relevant cases includes Perma Life Mufflers, Inc. v.

International Parts Corp., 392 U.S. 134, 138 (1968), in which

the Court refused to apply the common law doctrine of in

pari delicto as a defense to actions under the antitrust laws,

overruling the circuit court’s holding that the plaintiffs were

barred from recovery because they had participated in the

very antitrust violations for which they sought redress. The

Court noted that "[tjhere is nothing in the language of the

antitrust acts which indicates that Congress wanted to make

the common-law in pari delicto doctrine a defense to [private]

actions" and that "the purposes of the antitrust laws are best

served by insuring that the private action will be an ever

present threat to deter anyone contemplating" a violation.

Id. at 138, 139. In the end it did not matter that the

plaintiffs "may be subject to some criticism for having taken

any part in [defendants’] allegedly illegal scheme and for

eagerly seeking" more profits, id. at 139-40, for the

importance of private enforcement of the antitrust laws

carried the day.

The Court reached the same result on similar reasoning

under the securities laws in Bateman Eichler, Hill Richards,

Inc. v. Berner, 472 U.S. 299, 307 (1985). It stressed the

importance of private actions in the enforcement of those

laws and noted that it has "emphasized ‘the

inappropriateness of invoking broad common-law barriers to

relief where a private suit serves important public purposes.’"

Id. at 307 (quoting Perma Life). It held that denying the in

pari delicto defense would best serve the purposes of the

federal securities laws because barring private actions "would

inexorably result in a number of alleged fraudulent practices

going undetected by the authorities and unremedied." Id. at

315.

- 23 -

Those decisions preclude the recognition of a fault-

based defense here, for private enforcement actions under

the ADEA and Title VII are essential to their enforcement.

See note 12, supra. Moreover, if plaintiffs who have violated

the very statutes they sue to enforce are not barred by their

misconduct, then a fortiori plaintiffs who seek to vindicate

federal statutes they have not violated cannot be turned away

on supposed public policy grounds of punishing wrongdoers.

In sum, these two lines of decisions demonstrate that

the proper approach to after-acquired misconduct evidence

in discrimination cases is one that forthrightly seeks to

accommodate the competing policy concerns. Where the

policies expressed in a federal statute run up against

countervailing public policies, the courts should fashion a

remedy that "protects against the invasion of [federal] rights

without commanding undesirable consequences not necessary

to the assurance of those rights." Mt. Healthy, 429 U.S. at

287. The lower courts’ theory of causation/legal injury

frustrates this goal by forcing a choice between a complete

remedy or no remedy at all. Faced with this artificial choice,

it is small wonder that most courts have opted to leave the

plaintiff empty-handed.

III. After-Acquired Evidence May Affect The Remedies

Available In Particular Cases

We have shown that denying all relief to victims of

unlawful discrimination on the basis of after-acquired

evidence is inconsistent with the language and purposes of

the fair employment laws. In this part we discuss the proper

effect of after-acquired evidence on the four types of relief

requested by petitioner in her complaint: (1) backpay for the

wages and benefits she lost as a result of her wrongful

dismissal and discriminatory denial of raises while she was

employed; (2) reinstatement and front pay; (3) compensatory

damages for the humiliation and embarrassment she suffered

- 2 4 -

as a result of age harassment, and (4) liquidated or punitive

damages. We show that, although after-acquired evidence

should never affect the availability of liquidated damages, in

particular cases it may serve to terminate backpay and

certain compensatory damages sooner than would otherwise

be required and to preclude reinstatement and front pay

entirely. Permitting after-acquired evidence to play a role

in the formulation of a remedy is consistent with the

statutory goal of placing discrimination victims, as near as

may be, in the position they would have occupied had the

discrimination not occurred. United States v. Burke, 112 S.Ct.

1867, 1873 (1992) (Title VII); Albemarle Paper, 422 U.S. at

418; Hawley v. Dresser Indus., Inc., 958 F.2d 720, 725 (6th

Cir. 1992) (ADEA); Duffy v. Wheeling Pittsburgh Steel Corp.,

738 F.2d 1393, 1398 (3d Cir. 1984) (same). Such evidence

may demonstrate that an unlawfully discharged worker who

files a discrimination action would have been discharged

lawfully prior to the date of final judgment in that action

even in the absence of discrimination. Under these

circumstances, reinstating the plaintiff and awarding full

backpay would disserve the purposes of the fair employment

laws by making the plaintiff better off than if no

discrimination had occurred. See Wallace, 968 F.2d at 1182;

cf. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-(2)(j).

Allowing the use of after-acquired evidence to limit

relief creates an obvious incentive for defendants to claim

that any previously undisclosed resume falsification or

workplace-rule infraction would have resulted in the

plaintiffs dismissal had it been known. To guard against the

possibility of abuse, a defendant should be required to prove

its claim by objective evidence, such as a preexisting written

policy stating that the conduct in question will result in

immediate dismissal. See Welch v. Liberty Machine Works,

1994 U.S. App. LEXIS 10028, at *8, 23 F.3d 1403 (8th Cir.

Jan. 13, 1994) (reversing summary judgment for employer

because "self-serving affidavit" did not meet the "substantial

- 25 -

burden of establishing that the policy predated the hiring and

firing of the employee''); cf. EEOC Revised Enforcement

Guide, supra, at 405:6925 (employer must offer "objective

evidence" of a "legitimate reason for the action" in mixed

motive cases).

In addition, the defendant should be required to prove

that its policy mandating dismissal is actually applied on a

nondiscriminatoiy basis to others who engage in the same or

similar conduct. See Franks, 424 U.S. at 772-73 & n.32;16

McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 804 (1973)

(evidence that employer had retained other employees who

engaged in same conduct is "especially relevant" to showing

pretextual nature of employer’s stated reason for discharge).

Finally, the court should bear in mind that proof that an

employee would not have been hired is not proof that the

employee would have been fired, for "[tjhere are many

situations * * * in which an employer would not discharge an

employee if it subsequently discovered resume fraud,

although the employee would not have been hired absent

that resume fraud." Bonger v. American Water Works, 789 F.

Supp. 1102, 1106 (D. Colo. 1992). Accord Washington v.

Lake County, III, 969 F.2d at 254.

With the foregoing in mind, we turn now to the

different forms of relief requested by petitioner.

16 In Franks the Court held that an employer could avoid providing

make-whole relief to applicants who were discrim inatorily denied

consideration for line driver positions by showing that the individuals in

question would not have been hired on the basis of "nondiscriminatory

standards actually applied by Bowman to individuals who were in fact

hired." 424 U.S. at 733 n.32 (emphasis added).

- 2 6 -

A. Backpay. A worker who has been discharged

discriminatorily is normally entitled to backpay from the date

of discharge to the date of final judgment. See Lorillard v.

Pons, 434 U.S. at 584; Franks, 424 U.S. at 786 (Powell, J.,

concurring and dissenting); Anastasio v. Sobering Corp., 838

F.2d 701,708 (3d Cir. 1988). However, "[cjonsistent with the

ADEA’s purpose of recreating the circumstances that would

have existed but for the illegal discrimination, aggrieved

persons are not entitled to recover damages for the period

beyond which they would have been terminated for a

nondiscriminatory reason." Gibson, 695 F.2d at 1097.

Accord Stacey v. Allied Stores Corp., 768 F.2d 402, 408 (D.C.

Cir. 1985); Hill v. Spiegel, Inc., 708 F.2d 233, 238 (6th Cir.

1983). Thus, for example, an employee is not entitled to

backpay beyond the period when his or her job would have

been eliminated because of plant closure, see Gibson, 695

F.2d at 1097, or a company reorganization, see Bartek v.

Urban Redevelop. Auth., 882 F.2d 739, 747 (3d Cir. 1989).

It follows that the victim of a discriminatory dismissal

should not receive full backpay if the employer can prove

that, even absent the discrimination, it would have

discovered a legitimate reason for dismissal prior to the date

of final judgment and would have dismissed the plaintiff on

that basis alone. Back pay should be awarded, however, up

until the point the legitimate reason would have been

discovered. Since the employee would have remained

employed up to that time but for the discrimination, a denial

of back pay covering this period of time would leave the

plaintiff worse off than if discrimination had not occurred.

See Wallace, 968 F.2d at 1182.

Although an employer may well find it difficult to

prove when evidence of employee misconduct would have

been discovered absent the plaintiffs suit, employers seeking

to limit backpay liability are often called upon to prove what

would have happened to a worker had the employer not

- 2 7 -

discriminated. See, e.g., International Bhd. of Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. at 324, 359, 362 (1977); Gibson, 695

F.2d at 1009. Where the employee’s misconduct was particu

larly egregious or detrimental to the employer, a court may

conclude that it would have been discovered in short order.

Regardless of the difficulty of proof, however, "[t]he most

elementaiy conceptions of justice and public policy require

that the wrongdoer shall bear the risk of the uncertainty

which his own wrong has created." Bigelow v. RKO Radio

Pictures, Inc., 327 U.S. 251, 265 (1946).17 And the nature

of an employee’s misconduct, even if particularly egregious,

does not justify a departure from the make-whole principle

of relief. As this Court has previously observed, even

workers who have committed "a serious criminal offense

against their employer" are entitled to the full protection of

the fair employment laws. McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail

Transp. Co., A ll U.S. 273, 281 (1976). See also McDonnell

Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 803-04 (1973).18

B. Reinstatement and Front Pay. Normally an

order of reinstatement is required to make the prevailing

plaintiff whole. See Franks, 424 U.S. at 779; Taylor v.

Teletype Corp., 648 F.2d 1129, 1138 (8th Cir. 1981); Duke v.

Uniroyal Inc., 928 F.2d 1413, 1423 (4th Cir. 1991). Unlike

17 For these reasons we disagree with the EEOC’s position that backpay

should terminate on the date the misconduct was actually discovered, for

that position may leave a worker worse off as a result of discrimination.

18 The Tenth Circuit in Summers hypothesized the situation in which,

during the course of fair employment litigation, one purporting to be a

doctor is unmasked as a fake. To our knowledge no case has presented

such an extreme situation, but should such an unlikely case ever arise a

court of equity may deal with it appropriately without violating the

deterrent and make-whole purposes of the fair employment laws. Cf.

Albemarle Paper, 422 U.S. at 424 (in particular cases which have been

litigated in an unusual manner, backpay can be denied without

implicating the purposes of backpay relief).

- 28 -

backpay, however, which "squares accounts of what may be

a closed relationship," "[ojrders for reinstatement and hiring

are of on-going consequence to both employee and employer

and [thus] involve more than making a victim of

discrimination whole for past injuries." Rodriguez, 569 F.2d

at 1242 n.21. Accordingly, most courts have recognized that

"notwithstanding the desirability of reinstatement, intervening

historical circumstances can make it impossible or

inappropriate." Duke v. Uniroyal Inc., 928 F.2d at 1423. See

also, e.g., Houghton v. McDonnell Douglas Corp., 627 F.2d

858 (8th Cir. 1980) (denying reinstatement because plaintiff

was no longer physically fit for the position); Ginsberg v.

Burlington Indus., Inc., 500 F. Supp. 696, 699 (S.D.N.Y. 1980)

(appropriate to deny reinstatement where facts demonstrate

a "‘lack of complete trust and confidence between plaintiff

and defendant’").

The discovery of after-acquired evidence is an

"intervening historical circumstance" that may make

reinstatement inappropriate. First, if the employer proves

that, even absent the discriminatory dismissal and ensuing

litigation, it would have discovered the after-acquired

evidence in short order and dismissed the plaintiff,

reinstatement would in effect make the plaintiff better off

than if no discrimination had occurred. Second, even

without such proof, the discovery itself may nevertheless so

damage the employment relationship that reinstatement

would be unworkable. McKnight v. General Motors Corp.,

908 F.2d 101, 115 (7th Cir. 1990). In the latter case,

however, an award of front pay might be appropriate to

compensate for the lack of reinstatement. See Duke v.

Uniroyal Inc., 928 F.2d at 1423; Carter v. Sedgwick County,

Kan., 929 F.2d 1501,1505 (10th Cir. 1991); Floca v. Homcare

Health Servs., Inc., 845 F.2d 108, 112 (5th Cir. 1988); cf.

Burke, 112 S. Ct. at 1873 & n.9.

- 29 -

C. Compensatory Damages. Under the Civil Rights

Act of 1991, prevailing plaintiffs in disparate treatment cases

are entitled to compensatory damages for pain and suffering

caused by employment discrimination. 42 U.S.C. § 1981a.

This Court has never determined whether such damages are

available under the ADEA, a question on which Franklin v.

Gwinnett County Public Schools, 503 U.S. __ , 112 S. Ct.

1028 (1992), may bear heavily. But the Court need not

decide that issue to hold that after-acquired evidence should

have no effect on the availability of compensatory damages

where, as here, they are sought as a remedy for age-based

harassment. The harms inflicted by discriminatory

harassment are well-documented in the prior decisions of

this Court. See Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57

(1986); Harris v. Forklift Sys., Inc., __U.S. ___, 114 S. Ct.

367 (1993). These harms are not diminished simply because

an employer can show that it would have fired (or would not

have hired) the victim had it known something of which it

was unaware. Cf Still, supra. Where, however,

compensatory damages are sought to offset harm resulting

from unemployment, then, like backpay, they should not be

awarded beyond the point at which the plaintiff would have

been dismissed for legitimate reasons. See EEOC Revised

Enforcement Guide, supra, at 405:6926 (after-acquired

evidence may cut off compensatory damages covering losses

arising after discovery of misconduct).

D. Liquidated Damages. Punitive damages are

available under Title VII as amended by the Civil Rights Act

of 1991 if the employer acts "with malice or with reckless

indifference" to the employee’s rights, 42 U.S.C. § 1981a, and

under the ADEA in the form of liquidated or double

damages if the employer’s violation was "willful," 29 U.S.C.

§ 626(b). See Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Thurston, 469 U.S.

I l l , 125 (1985) (Congress intended ADEA’s liquidated

damages to be punitive in nature). A violation is "willful" if

the employer "‘knew or showed reckless disregard for the

- 30 -

matter of whether its conduct was prohibited by the ADEA.’"

Id. at 128 (citation omitted).

After-acquired evidence should have no effect on the

availability of liquidated or punitive damages under the fair

employment laws. See EEOC Revised Enforcement Guide,

supra, at 405:6927. Those remedies are awarded depending

on the employer’s understanding of the lawfulness of its own

conduct; information the employer did not acquire until after

it acted can have no bearing on that issue. Moreover,

because punitive damages are meant to deter rather than

compensate, the employer’s conduct, not the employee’s, is

the only relevant consideration.

CO NCLUSION

The judgment of the court of appeals should be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Michael A. Cooper William F. Sheehan

(Counsel o f record)

William D. Weinreb

Amy Horton

Shea & Gardner

1800 Massachusetts Ave., NW

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 828-2000

Co-Chair

Norman Redlich, Trustee

Barbara J. Amwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Richard T. Seymour

Sharon R. Vinick

Lawyers’ Committee For

Civil Rights Under Law

1450 G Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 662-8600

Steven R. Shapiro

H elen Hershkoff

Sara L. Mandelbaum

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43 Street

New York, N .Y . 10026

(212) 944-9800

Cathy Ventrell-Monsees

American Association of

Retired Persons

601 E Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20049

(202) 434-2060

Counsel for A m ici Curiae