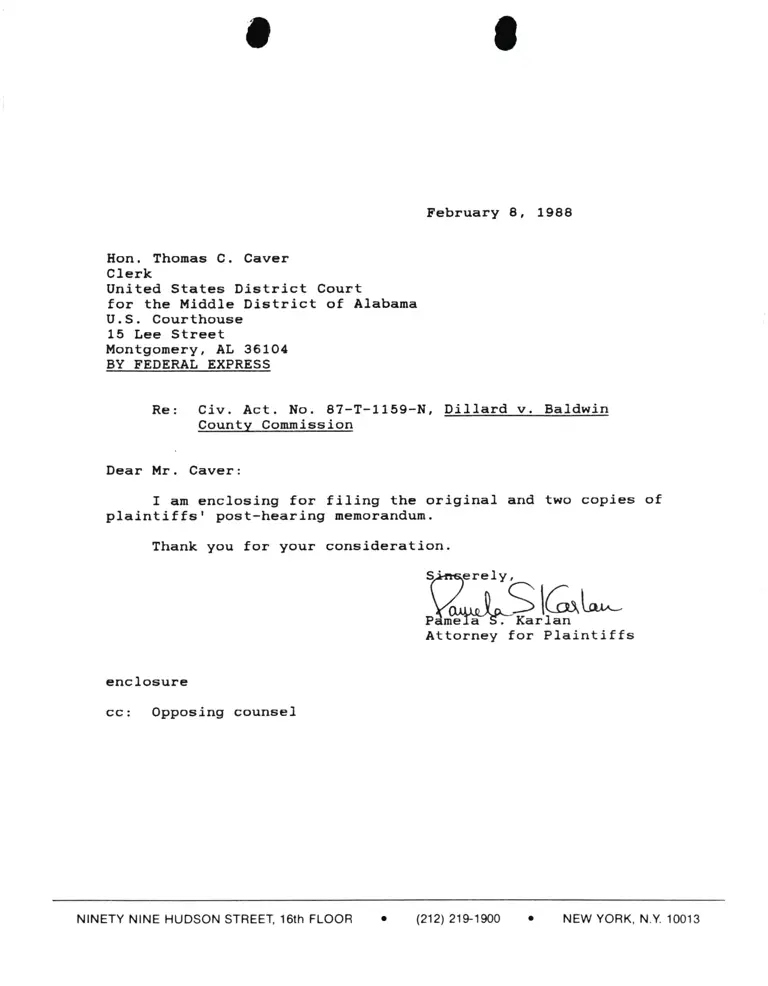

Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Thomas C. Caver (Clerk) Re: Dillard v. Baldwin

Public Court Documents

February 8, 1988

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Pamela Karlan to Thomas C. Caver (Clerk) Re: Dillard v. Baldwin, 1988. 4907841e-ec92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d870d492-d156-43ba-852e-abdcc2dbd2d2/correspondence-from-pamela-karlan-to-thomas-c-caver-clerk-re-dillard-v-baldwin. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Hon. Thouae C. Cavcr

Clerk

United States District Court

for the Mlddle Dietrict of Alabana

U.S. Courthouse

15 Lee Street

Montgom€Ey, AL 36104

BY FEDERAL EXPRESS

Re: Civ. Act. No. 87-T-1159-N,

Countv Coumiseion

Dear Mr. Caver:

enclosure

cc: Opposing counsel

February 8, 1988

Dillard v. Baldwin

I am enclosing for filing the original and two copies of

plaintiffe I post-hearing memorandum.

Thank you for your consideration.

Sitqerelv,

"kd*ml6u^-Attorney for Plaintiffs

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREEI, 16th FLOOR (212) 2191900 NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013