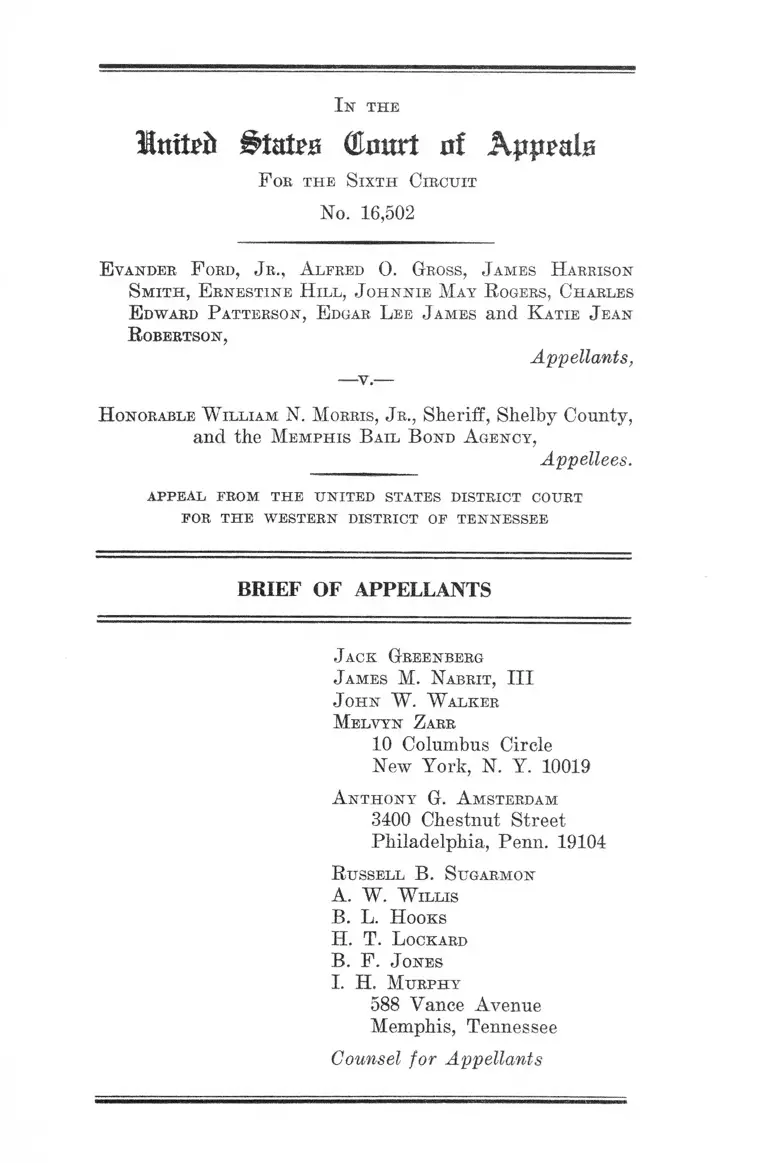

Ford v. Morris Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. Morris Brief of Appellants, 1965. 9ed19d27-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d88450a5-bb52-48a0-a475-2c69af66d821/ford-v-morris-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

United States (Enurt nf Apjipate

F or t h e S ix t h C ir c u it

No. 16,502

E vandeb F ord, J r ., A lfred 0 . Gross, J am es H arrison

S m it h , E r n e s t in e H il l , J o h n n ie M ay R ogers, C h a rles

E dward P a tterso n , E dgar L ee J am es a n d K a tie J ean

R obertson,

Appellants,

H onorable W il l ia m N. M orris, J r ., Sheriff, Shelby County,

a n d the M e m p h is B a il B ond A gen cy ,

Appellees.

appeal from the united states district court

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

J o h n W . W a lk er

M elv y n Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A n t h o n y G. A m sterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Penn. 19104

B u sse l l B . S ugarm on

A . W . W il l is

B . L. H ooks

H. T. L ockard

B . F . J o nes

I . H. M u r p h y

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Counsel for Appellants

INDEX TO BRIEF

PAGE

Questions Presented ........ ......-.............. ....................... 1

Statement of F acts........................—.............................. 2

A rgument

I. Where the sheriff held a capias for appellants’

arrest pursuant to affirmance of their convic

tions, the incidents of their hail on professional

bond pending appeal amount to “custody”

sufficient to support habeas corpus ........... ...... 5

II. Appellants’ convictions under Tenn. Code Ann.

§39-1204 denied them due process of law be

cause there was either no evidence of their

commission of crime or, alternatively, the ap

plication of the statute failed to furnish them

fair warning of the conduct proscribed and en

forced racial segregation in public facilities in

violation of the equal protection clause............ 9

III. Application by the state trial judge of an er

roneous standard of federal constitutional law

requires that appellants’ convictions be vacated 13

IV. The court below erred in denying appellants

an evidentiary hearing and, further, in failing

to make an independent determination of the

ultimate constitutional issues on the record.... 15

Conclusion 17

T able oe C ases

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964) ......................... 11

Barr v. Columbia, 378 TL S. ----- (1964) ________ 10,12

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 II. S. 249 (1952) .............. ...... 12

Bouie v. Columbia, 378 IT. S .----- (1964) _______ __ 11

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 294

(1954) ............... ........................... ............. ......... 11-12,13

Brown v. Bayfield, 320 F. 2d 96, 99 (5th Cir. 1963,

cert, denied 375 IT. S. 902 (1963) ............................... 6

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 IT. S.

715 (1961) ................ ............................................... 12,13

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 IT. S. 196 (1948) ......... ............ . 14

Cosgrove v. Winney, 174 IT. S. 64 (1899) ........... ......... 8

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 IT. S. 536 (1965) ........... 11

Fay v. Noia, 372 IT. S. 391 (1963) ........ ..................... 17

Fitzpatrick v. Williams, 46 F. 2d 40 (5th Cir. 1931) .... 8

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157 (1961) .............. 10,12

Gayle v. Browder, 352 IT. S. 903 (1958) ........................ 12

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (1958) ...... .............. 12

Jackson v. Denno, 378 IT. S. 368 (1964) .................. 16

Jones v. Cunningham, 371 U. S. 236 (1963) .........5-6, 7, 8, 9

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 IT. S. 257 (1963) ...........12,15

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U. S. 1 (1964) ........... ................ 16

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association, 202

F. 2d 275 (6th Cir. 1953, judgment vacated and re

manded, 347 U. S. 971, 1954) ................................ . 12

i i

PAGE

NAACP V. Button, 871 U. S. 415 (1963) ..................... 11

Peterson v. California, 331 P. 2d 24 (1958), app. dism’d

360 U. S. 314 (1959) ............................... .......... ........ 6

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 377 U. S. 244 (1963) ....12,15

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153 (1964) ..............12,15

Reese v. United States, 9 Wall 13 (1869) ....... ............. 8

Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U. S. 534 (1961) .............. 13,14

Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1 (1948) ................. 12

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 (1959) ......... 11

Stack v. Boyle, 342 U. S. 1 (1951) ........ 7

State v. Spring, 176 S. W. 2d 817 (1944) ........ 8

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 (1931) .............. 11

Taylor v. Taintor, 16 Wall 366 (1872) ................ ........ 8

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 (1959) .............. 10

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 TJ. S. 88 (1940) ................. 11

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963) ..............15,16,17

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 (1962) ........... 12

United States v. Trunko, 189 F. Supp. 559 (E. D. Ark.,

1960) ...... .................................................................... 8

Wales v. Whitney, 114 U. S. 564 (1885) ........................ 5

Wallace v. State, 269 S. W. 2d 78 (1954) ........ ............ 8

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 (1963) ..11,15,16

Ill

PAGE

IV

Other A uthorities

2 Hale, P leas of the Crown 124 (1st American Ed.

Philadelphia, 1847) ................ ................................... 7

2 Pollock and Maitland, H istory oe E n g l is h L aw 589

(2d Ed. 1952) .......... .................................................. 7

S tatutes

28 IT. S. C. §2241 (c) (3 ) ............................................. ............... .9,17

Tennessee Code Annotated, §39-1204 .............................. .......9 , 10

PAGE

Isr the

(&mvt rtf A ppa ls

F oe t h e S ix t h C ie c u it

No. 16,502

E vander F oed, J r ., A lfred 0 . Gross, J am es H arrison

S m it h , E r n e s t in e H il l , J o h n n ie M ay R ogers, C h a rles

E dward P a tterso n , E dgar L e e J am es a n d K a tie J ea n

R obertson ,

Appellants,

H onorable W il l ia m N. M orris, J r., Sheriff, Shelby County,

and the M e m p h is B a il B ond A gen cy ,

Appellees.

appeal from the united states district court

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Q uestions P resented

I. Were appellants, who had been admitted to bail on

professional surety bonds pending appeal of state crim

inal convictions, but for whose arrest the sheriff held a

capias issued pursuant to affirmance of the convictions, so

restrained of their liberty as to be in “custody” within the

federal habeas corpus statute, 28 U. S. C. §2241(c)(3)?

The court below answered no. The answer should have been

yes.

II. Were appellants denied due process under the Four

teenth Amendment because their state convictions were

either based upon no evidence or upon an application of

2

the state criminal statute which failed to furnish fair warn

ing of the conduct proscribed? The court below did not

answer this question. The answer should have been yes.

III. Were appellants, by their convictions, deprived of

their right of freedom from state enforced racial segrega

tion guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment? The court

below did not answer this question. The answer should

have been yes.

IY. Were appellants entitled by the standards of

Townsend v. Sain-, 372 U. S. 293 (1963), to an evidentiary

hearing in the court below? The court below answered no.

The answer should have been yes.

V. Did the application by the state trial judge of an

erroneous standard of federal constitutional law require

reversal of appellants’ convictions? The court below an

swered no. The answer should have been yes.

VI. Did the court below err in failing* to make indepen

dent findings on the ultimate constitutional issues presented

by appellants’ habeas corpus petition?

Statem ent o f Facts

On August 30, 1960 (3a), the Assembly of God Church

in Memphis, Tennessee (2a) held a city-wide Youth Rally

at Overton Park Shell (2a) an open air auditorium located

in a publicly owned park (19a). The church group had

leased the auditorium from the City of Memphis (3a, 26a)

and had published advertisements of the services which

were to consist of singing, devotions and a special film

(2a). Negroes were not excluded from the public invita

tion because, according to a church official, there were no

3

Negro members in the Assembly of God Church and none

were expected to attend (8a, 9a). The services began at

7 :30 P.M. with from 400 to 700 people present (3a).

About 15 minutes after the service began and while the

group was singing hymns, a group of 13 or 14 Negroes

(4a, 11a) including the appellants entered and was greeted

by the head usher for the group who testified: “I asked

them out of courtesy if they would not remain, since this

was a segregated meeting, featuring* the young people of

the Assembly of God.” When the Negroes refused to leave,

the usher directed them to take seats on a segregated basis

at the rear of the building (11a). Petitioner Ford told the

usher: “No, we are certainly not going to do that, . . . ”

(22a), and according to the usher, directed the group to

“scatter out” (11a).

The Negroes proceeded down into the audience, and

seated themselves in couples among the gathering. They

were quiet, properly dressed, used no profanity and made

no noise while taking seats (14a, 15a, 23a, 24a). Never

theless, according to State witnesses, as the Negroes moved

in, white people began to move, and some left (12a) be

cause a church official reported “they were not accustomed

to attending* services with Negroes” (5a). This moving

and shifting created some disturbance (5a, 7a). However,

the service continued until the minister in charge of the

group, Rev. Scruggs, called the police (5a, 6a). When the

police arrived about five or ten minutes later, most of the

white people were settled, an offering may have been re

ceived, the lights had been lowered, and the movie was in

progress. Nonetheless, when the police arrived, the lights

were turned on again and the movie was stopped so that

the police could find the petitioners (9a). The police were

instructed to locate colored people in the Shell, inform

4

them they were under arrest and bring them outside (16a).

Police officers testified that fourteen Negroes, male and

female were arrested (17a). All were seated quietly when

the police arrived, were properly dressed, used no loud or

profane language, engaged in no boisterous or indecent

conduct, and offered no resistance to arrest (18a).

Rev. Scruggs contended that he had appellants arrested

not because they were Negroes, but because they created

a disturbance when they refused to take seats in the rear

and “decided to . . . intermingle with the crowd” (9a). He

concluded that the disturbance grew out of the fact that

the white people were not accustomed to attending services

with Negroes (7a).

“Q. And this disturbed the gathering, in this sense

of the word because they were Negroes? A. I suppose

that’s true; yes” (7a).

Following their arrest, the appellants were tried and con

victed of violating Section 39-1204, Tennessee Code Anno

tated.

Appellants, with the exception of Katie Jean Robertson,

were tried on June 19th and 20th, 1961. and were sentenced

to serve 60 days in the Shelby County Penal Farm, and

fined $200. Petitioner Katie Jean Robertson was tried on

September 25, 1961 and was sentenced to serve 60 days and

fined $175.00.

The Supreme Court of Tennessee affirmed the convictions

finding that appellants’ actions created a disturbance of

the religious service and therefore violated the statute

(32a-40a). Moreover, the Court found that such actions

were willful and designed to create an incident. The Court

stated that the issue of whether Negroes could be segregated

at the service held in a public facility was not presented

5

by tins case and the convictions did not violate any consti

tutional rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the petitioners.

Pending the appeal to the Supreme Court of Tennessee,

appellants had been admitted to bail on professional surety

bonds (56a). Following affirmance of their convictions, a

capias issued to the sheriff for their arrest in execution of

sentence (56a). They thereupon presented to the federal

district court below their petition for writ of habeas corpus,

naming the sheriff and bonding company as respondents.

The district court refused an evidentiary hearing on the

petition and, accepting the conclusions of fact and law of

the Tennessee courts, denied the petition in an order ac

companied by a written opinion (55a-66a).

ARGUMENT

I.

W here the sheriff h eld a capias fo r appellants’ arrest

pursuant to affirm ance o f their convictions, the in c i

dents o f their hail on p rofession al bond pending appeal

am ount to “ custody” sufficient to support habeas

corpus.

The question has been much mooted whether a state

criminal defendant bailed on one or another of the various

forms of bond is in “custody” for purposes of habeas

corpus. The old cases cited by the court below (57a) hold

that bail status generally is not “custody,” but these deci

sions reflect an outmoded concept of custody as actual

physical confinement, E.g., Wales v. Whitney, 114 U. S. 564

(1885). The Supreme Court has recently repudiated that

concept and has held that the use of habeas corpus is “not

restricted to situations in which the applicant is in actual,

physical custody.” Jones v. Cunningham, 371 U. S.

6

236, 239 (1963).) As the Fifth Circuit has since noted, the

Jones decision substantially affects the custody require

ment of 28 U. S. C. §2241 and fairly puts in question the

authority of the earlier cases. Brown v. Bayfield, 320 F. 2d

96, 99 (5th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 375 U. S. 902 (1963).

And see Peterson v. California, 51 Cal. 2d 177, 331 P. 2d

24 (1958), app. disrn’d, 360 IT. S. 314 (1959).

Were it necessary to reach the question in this case, ap

pellants would strongly urge that by the reasoning of

Jones a Tennessee criminal defendant bailed on profes

sional surety bond is eo ipso in “custody” within the fed

eral habeas corpus jurisdiction. In Jones, the Supreme

Court held that a Virginia convict’s parole status was

enough to support the habeas jurisdiction of the district

court. Although the convict had been returned to the

community, the court found significant restraints on his

liberty because of his conviction. He could not drive a car

without the permission of his parole officer, to whom he

was required to report periodically; and under the terms

of his parole he was required to keep good company and

good hours, work regularly, keep away from undesirable

places and live a clean, honest and temperate life. The

Supreme Court determined that:

Such restraints are enough to invoke the help of the

Great Writ . . . (I)ts scope has grown to achieve

its grand purpose—the protection of indivduals against

erosion of their rights to be free from wrongful re

straints upon their liberty. While petitioner’s parole

relieves him from immediate physical imprisonment,

it imposes conditions which significantly confine and

restrain his freedom; this is enough to keep him in

the custody of the members of the Virginia Parole

Board within the meaning of the habeas corpus statute.

(371 U. S. at 243.)

7

Critical to the Court’s conclusion was its recognition that

a parolee:

must not only faithfully obey [his parole] . . . restric

tions and conditions but he must live in constant fear

that a single deviation, however slight, might be enough

to result in his being returned to prison to serve out

the very sentence he claims was imposed upon him in

violation of the United States Constitution. He can

be rearrested at any time the Board or parole officer

believes he has violated a term or condition of his

parole, and he might be thrown back in jail to finish

serving the allegedly invalid sentence with few, if any,

of the procedural safeguards that normally must be

and are provided to those charged with crime (371 U. S.

at 242).

This language, of course, precisely describes the circum

stances of a bailed criminal defendant. The whole purpose

of the bail arrangement is to impose some “restraints on

a man’s liberty, restraints not shared by the public gen

erally . . . ,” Jones v. Cunningham, supra, 371 U. S. at 240.

“ . . . Like the ancient practice of securing the oaths of

responsible persons to stand as sureties for the accused,

the modern practice of requiring a bail bond or the deposit

of a sum of money subject to forfeiture serves as an addi

tional assurance of the presence of the accused. . . . ” Stack

v. Boyle, 342 U. S. 1, 5 (1951). Not only is the theory of

bail that “he that is bailed, is in supposition of law still in

custody,” 2 H ale, P leas oe the Crown 124 (1st American

ed., Philadelphia 1847)—indeed, an expressive historical

phrase speaks of the sureties as “ ‘the Duke’s living

prison,’ ” 2 P ollock & Maitland, H istory of E nglish L aw

589 (2d ed. 1952)—but, as a practical matter, the sureties

“ [W]henever they choose to do so, . . . may seize him

and deliver him up in their discharge; and if that can

not be done at once, they may imprison him until it

can be done. . . . ‘The bail have their principal on a

string, arid may pull the string whenever they please,

and render him in their discharged . . . (Taylor v.

Taintor, 16 Wall. 366, 371-372 (1872)).

See also Reese v. United States, 9 Wall. 13, 21 (1869) (alter

native ground); Cosgrove v. Winney, 174 U. S. 64, 68 (1899)

(alternative ground); Fitzpatrick v. Williams, 46 F. 2d 40

(5th Cir. 1931) ; United States v. Trunko, 189 F. Supp. 559

(E. D. Ark. 1960) ; and see State v. Spring, 176 S. W.

2d 817 (1944), (“They [the sureties] could have surren

dered the defendant and procured their release at any

time. . . .”). See also, Wallace v. State, 269 S. W. 2d

78 (1954). Obviously, the surety’s power to retake

his principal is both more arbitrary and more summary

than that of the parole officer considered in Jones; and, in

addition, where a professional bondsman is involved, the

power of state officers to abuse the surety’s unlimited rights

of arrest is immeasurable, because the bondsman’s liveli

hood immediately depends upon the favor of local sheriffs,

prosecuting lawyers and judges.

However, the present case hardly need present the vexing

question whether Jones has overruled sub silentio the au

thorities relied on by the district court. Those cases are

true bail cases—cases in which the habeas petitioner was

released on bond for appearance at a date which was still

in futuro at the time of filing of the habeas corpus petition.

Appellants’ is no such case. The bail on which they were

enlarged was bail pending appeal; their appeal has been

had; their convictions (unconstitutionally, they assert) have

been affirmed; a capias for their arrest pursuant to the

affirmance was already in the hands of the respondent

sheriff at the time the petitions below were filed. Nothing

remained—no legal impediment nor requirement of legal

9

proceeding—before the sheriff could seize them in execu

tion of the capias. In this posture, it is patent that peti

tioners “might be thrown back in jail to finish serving the

allegedly invalid sentence with [none whatever] . . . of

the procedural safeguards that normally must be and are

provided to those charged with crime.” Jones v. Cunning

ham, supra; a fortiori from Jones, they were in custody

within the meaning of 28 IT. S. C. §2241 and amenable to

the district court’s writ.

II.

A ppellants’ convictions under T enn. Code Ann. §39-

1 2 0 4 denied them due process o f law because there

was either no ev idence o f their com m ission o f crim e

or, alternatively, the application o f the statute fa iled

to fu rn ish them fair w arning o f the conduct proscribed

and en forced racial segregation in pub lic facilities in

vio lation o f the equal protection clause.

Tenn. Code Ann. §39-1204 provides:

If any person willfully disturb or disquiet any as

semblage of persons met for religious worship, or for

educational or literary purposes, or as a lodge or for

the purpose of engaging in or promoting the cause of

temperance, by noise, profane discourse, rude or in

decent behavior, or any other act, at or near the place

of meeting, he shall be fined not less than twenty dol

lars ($20.00) nor more than two hundred dollars

($200.00), and may also be imprisoned not exceeding

six (6) months in the county jail.

A. It is appellants’ contention that the court below erred

in relying on the findings of fact in the state court record

and in denying appellants an evidentiary hearing (see

1 0

Argument IY, infra). However, a more serious error

infects the judgment of the court below, compelling re

versal by this Court, for the state court record errone

ously relied upon below itself reveals no evidence of crime.

That record, construed most favorably to appellee, merely

shows the following “objective acts.” Appellants and

several other Negroes entered an auditorium located in

a public park to attend a religious rally advertised as open

to the public. They were not noisy, used no profanity, and

indulged in no rude or indecent behavior. Upon their

entrance, they were met by a white church official who

first tried to exclude them by saying that it was a “segre

gated” meeting, and, upon being unsuccessful, then tried

to seat them on a segregated basis, apart from the white

persons in the audience, at the rear of the auditorium.

Appellant Ford, the apparent leader of the group, directed

the Negroes to “scatter out”, whereupon they quietly seated

themselves at various points in the auditorium—just as

10 or 15 white late-comers had done.

The court below held that a finding that appellants came

late and took seats in the middle of rows could support a

conviction of disturbing religous worship. Such a ruling,

although doubtlessly gratifying to punctual parishioners

incensed at their tardy brethren, is simply farcical. Ap

pellants merely attended the meeting—nothing more—and

their arrest and conviction would be incredible were they

not Negroes. This being so, appellants’ convictions offend

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment be

cause founded on no evidence of guilt. Thompson v. Louis

ville, 362 U. S. 199 (1959); Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S.

157 (1961)) ; Barr v. Columbia, 378 U. S. ----- (1964).

B. If appellants’ “objective acts” can be held to be

punishable under Tenn. Code Ann. §39-1204, that statute

must fall because it gives no fair warning of the conduct

11

proscribed. The construction placed upon the statute by

the Supreme Court of Tennessee gave an “all encompass

ing” (355 S. W. 2d at 102) effect to the catch-all phrase

“any other act”, placing appellants’ conduct within that

meaning. Such a construction could not reasonably have

been foreseen by appellants nor, indeed, by anyone else.

Thus this case is controlled by Bouie v. Columbia, 378 U. S.

----- (1964) and cases cited, and the statute is void for

vagueness.

Moreover, it is settled that requirements of clarity and

specificity are especially high in cases involving, as these

certainly do,1 the attempted penalization of expression.

Smith v. California, 361 IT. S. 147, 151 (1959); Stromberg

v. California, 283 U. S. 359 (1931); NAACP v. Button, 371

IT. S. 415, 432 (1963) and cases cited. Free expression will

clearly be endangered if courts, expressing local interests,

can avail themselves of the device of strained construction

of inapplicable statutes (cf. Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536,

551 (1965); Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 IT. S. 360 (1964)), and

police and prosecutors can engage in “selective enforcement

against unpopular causes.” Button, supra (371 IT. S. at

435); Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 IT. S. 88, 97-98 (1940).

C. The youth rally was held at a city-owned auditorium

open to, and provided for, the use of the public. Since it

is apparent that the arrest and conviction of appellants

were based upon their color and their failure to take seats

apart from the white people in attendance, the conclusion

compelled from the record is that the state court equated

appellants’ breach of the racial segregation policy with a

disturbance of the assembly and thus enforced segregation

under another label. This the State cannot do under the

numerous decisions of the Supreme Court. Brown v. Board

1 It cannot be doubted that appellants sought to express their right to

attend a public rally held in a public park segregated at the time by city

policy (Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 (1963).

12

of Education, 347 U. S. 294 (1954); Gayle v. Browder, 352

U. S. 903 (1958); Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (1958);

Garner v, Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961); Peterson v. City

of Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 (1963); Lombard v. Louisiana,

373 U. S. 267 (1963); Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153

(1964); Barr v. Columbia, 378 U. S .----- (1964).

The leasing of this open-air auditorium to a private

group does not alter this conclusion. The Supreme Court

has repeatedly held that the enforcement of racial segrega

tion in publicly-owned facilities cannot legally be accom

plished by leasing such facilities to private persons.

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715;

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U. S. 350; Muir v. Louis

ville Park Theatrical Association, 202 F. 2d 275 (6th Cir.

1953), judgment vacated and remanded, 347 U. S. 971.

By the same token, the state cannot enforce segregation

in such facilities through the use of its criminal laws any

more than it can do so by a segregation law or rule. The

Constitution forbids the courts, as well as other arms of

the states, from enforcing racial discrimination. Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ; Barrows v. Jackson, 346

U. S. 249 (1952).

The Supreme Court of Tennessee stated in its opinion

that the issue in the case was not whether petitioners had

a right to be at the meeting, but rather whether they will

fully disturbed the meeting. However, the record plainly

indicates that the finding that appellants created a dis

turbance was based upon the fact that their mere presence

as Negroes in a white assembly was in itself a disturbance.

Thus the State has made the presence of Negroes in a

white assembly a crime just as surely as if it had directly

punished appellants under a segregation law.

13

III.

A pplication by the state trial judge o f an erroneous

standard o f fed era l constitu tional law requires that

appellan ts’ convictions be vacated.

Appellants defended their prosecution in the state courts

on the ground that the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment gave them the right to enter as

they had the public auditorium where they were arrested.

The state trial judge rejected this defense, holding that

appellants could constitutionally be excluded from the audi

torium on grounds of race because the First Amendment’s

guarantee of freedom of religion to the worshippers al

lowed racial segregation at the rally. This was plainly

erroneous: even if the City of Memphis could consistently

with the First Amendment provide public facilities for a

religious meeting (a point of no small difficulty under the

Establishment Clause), it certainly could not thereby in

sulate itself pro tanto from its obligation under Broivn

v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), and, e.g.,

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715

(1961), not to discriminate racially in access to public

property. The court below assumed that the state trial

judge was in error on the point (60a, 61a), but held that

the error was insufficient to vitiate the conviction. In this,

the district court was wrong. The use of an erroneous

standard of federal law by the state trial judge in passing

on a federal constitutional defense is alone grounds for

release on federal habeas corpus. Rogers v. Richmond,

365 U. S. 534 (1961). The district court thought otherwise

because “the trial court’s belief . . . was not made known

to the jury” and “the opinion by the Supreme Court of

Tennessee on appeal, affirming the convictions, clearly is

14

not based on the assumption that petitioners had no con

stitutional right to attend the rally” (60a). But because

appellants’ federal constitutional defense was not a jury

issue in the state proceeding, the manner in which the

jury was given the issues which it had competence to de

cide is irrelevant. And the Tennessee Supreme Court’s

correct view of the law cannot cure the incorrect view of

the state trial judge because the state trial judge alone

had the power to find the facts upon which appellants’ con

stitutional defense depended. The trial judge thought that

appellants could be punished, consistently with the Equal

Protection Clause, even though the only disturbance of

which they were guilty was occasioned by the color of

their skin. Under this view, he did not have to find that

they created any other disturbance. The Supreme Court

of Tennessee did not agree that disturbance caused by ap

pellants’ color could be constitutionally punished, but af

firmed the convictions on the theory that some other sort

of disturbance—a disturbance which, if it existed, was

never found by the trial judge—might srpport punish

ment. This sort of disposition of appellants’ federal claim

is so procedurally deficient as itself to amount to a denial

of due process of law, cf. Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196

(1948), and certainly cannot save a conviction condemned

by the Rogers v. Richmond principle.

15

IV.

T he court below erred in denying appellants an

evidentiary hearing and, further, in fa ilin g to m ake

an independent determ ination o f the u ltim ate consti

tutional issues on the record.

Even had the state court record not required the court

below to order appellants’ discharge and the vacation of

their convictions, the district court could not properly

deny appellants relief without an evidentiary hearing.

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963), describes the broad

categories of cases in which such hearings are required.

One category comprises cases in which the state court

fact-finding procedure is inadequate to afford a full and

fair hearing. The present case falls within the category

because, as indicated in Part III of this Brief, the state

trial judge found the facts underlying appellants federal

claims under the influence of a plainly erroneous view of

federal constitutional law. A second category comprises

cases in which there is a substantial allegation of newly

discovered evidence bearing on the federal claim. That is

the case here, because subsequent to appellants’ trial the

City of Memphis officially took the position, in litigation

before the Supreme Court of the United States, of sup

porting segregation in its parks, including the Overton

Park where the rally which gave rise to appellants’ con

victions was held. Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526

(1963). Any substantial involvement of the City in dis

criminatory exclusion of appellants, Robinson v. Florida,

378 U. S. 244 (1964); Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244

(1963); Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 (1963), plainly

renders appellants’ convictions unconstitutional. In trying

the facts underlying the question of City involvement, ap

pellants are entitled to put before the trier the City’s

16

position in the Watson litigation. In addition, the court

below found that:

The facts were not as fully developed as might have

been desirable, but this was largely due to the choice

of petitioners not to testify (63a).

This finding clearly brings the case within the fifth cate

gory of Townsend, which requires a hearing where “the

material facts were not adequately developed at the state

court hearing.” 372 U. 8. at 313. That appellants did not

testify at the state court trial is an impermissible con

sideration upon which to deny them a federal hearing.

They could not have testified without self-incrimination,

and were not required to waive their federal constitutional

privilege, see Malloy v. Hogan, 378 IT. S. 1 (1964), as the

price of bolstering their federal constitutional defense on

the merits. Cf. Jackson v. Denno, 378 U. S. 368 (1964).

They are entitled to a federal forum in which that Hobson’s

Choice is not presented.

Finally, the district court not merely impermissibly

rested on the state record; it did what the Supreme Court

in Townsend reiterated that a federal habeas corpus court

could in no event do—that is, accept without independent

examination the ultimate legal conclusions of the state

criminal courts. Appellants have insisted from the outset

of this litigation that they are being prosecuted and con

victed for doing nothing more than wrhat the Equal Pro

tection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment allows. That

contention was never critically examined in the state court

litigation, save by the state trial judge, who answered it

under a clear error of federal law. The jury was not, and

could not have been, given that issue, and the Tennessee

Supreme Court did not try it. Nevertheless, the court be

low failed to examine the evidence, canvass the issues, and

17

and reach its own independent conclusion on the claim, as

Townsend requires of a federal habeas court even where

that court permissibly elects to rely on the state trial record.

The district court here simply accepted the state courts’

conclusions that there was no Equal Protection issue in

the case (62a). It is more than a little ironic that appel

lants, whose convictions rest on their attempt to test the

protection afforded them by the Equal Protection Clause,

have not yet had a hearing and determination of that issue.

The habeas corpus statute, 28 TJ. S. C. §2241 (c)(3) (1958),

entitles them to one. Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 (1963).

CONCLUSION

T he judgm ent o f the district court should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

J ohn W . W alker

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A nthony 6 . A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Penn. 19104

R ussell B. S ugarmon

A. W . W illis

B. L. H ooks

H. T. L ockard

B. F. J ones

I. H. Murphy

588 Vance Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee

Counsel for Appellants

M E IIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y.