Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board Brief Amici Curiae of American Civil Liberties Union and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. In Support of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1996

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board Brief Amici Curiae of American Civil Liberties Union and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. In Support of Appellants, 1996. dcbf252f-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d8a85167-242e-4e21-a58b-083d1b0f26cc/reno-v-bossier-parish-school-board-brief-amici-curiae-of-american-civil-liberties-union-and-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-inc-in-support-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

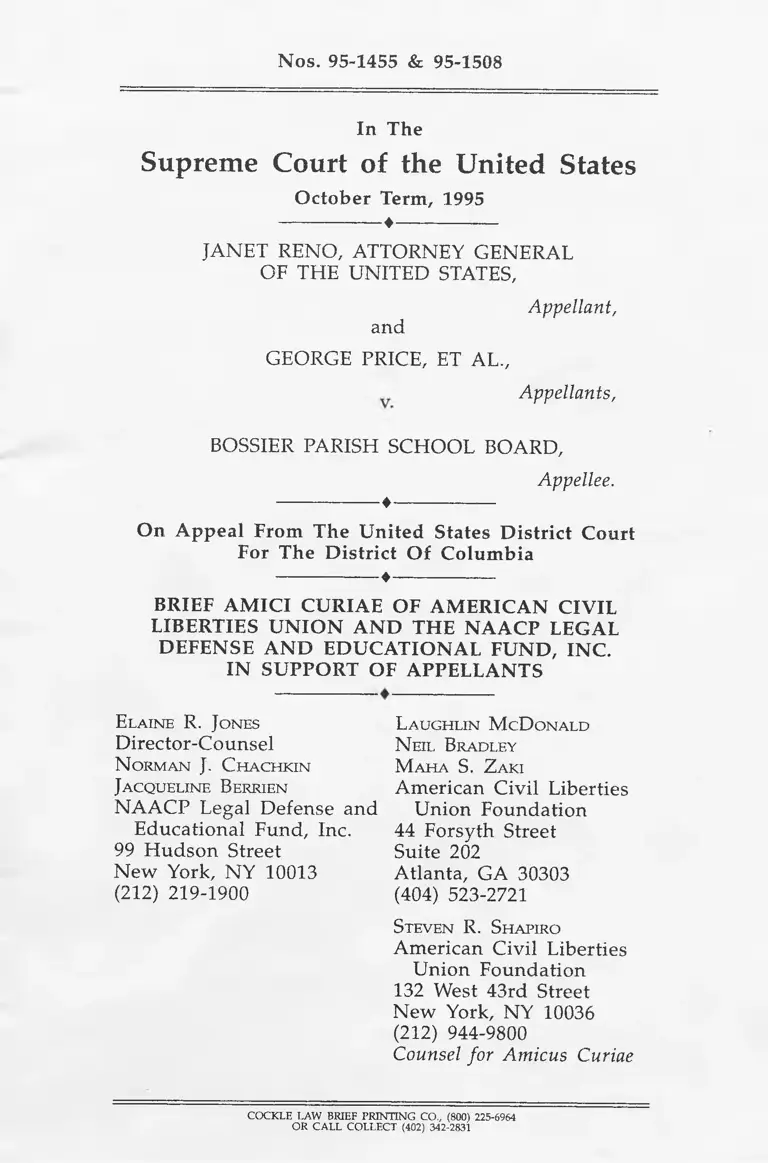

Nos. 95-1455 & 95-1508

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1995

----------------- ♦ -----------------

JANET RENO, ATTORNEY GENERAL

OF THE UNITED STATES,

and

Appellant,

GEORGE PRICE, ET AL.,

Appellants,

BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

♦

Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The District Of Columbia

-----------------♦ -----------------

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF AMERICAN CIVIL

LIBERTIES UNION AND THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

E la in e R. J o n es

Director-Counsel

N o rm a n J . C h a ch k in

J a cq u elin e B errien

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

L a u g h lin M c D o n a ld

N eil B ra d ley

M a h a S. Z a ki

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

44 Forsyth Street

Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

S tev en R. S h a piro

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................... ........................ ii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE............. 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT........................................... 2

ARGUMENT ................................................... 5

I. Section 2 Applies to Section 5 Preclearance........ 5

A. Interpretation of Section 5 Effects Test Prior

to 1982 .................. 6

B. Congressional Action in 1982 ..................... 8

C. The Attorney General's Regulations . . . . . . . . 11

D. The Legislative History Cannot Be Dis

counted............... 13

E. Congress Did Amend the Voting Rights Act . . 16

F. Some Voting Changes Are Not Amenable to

Analysis Under the Retrogression Standard. . . . 18

CONCLUSION................................................................... 20

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

C a ses :

American Jewish Congress v. Kreps, 574 F.2d 624

(D.C.Cir. 1 9 7 8 )................................... ...................... . 13

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976)

........................................ .......................... ... 2, 6, 7, 8, 10, 19

Bush v. Vera, 1996 WL 315857 (U.S. June 13, 1996) . . . . . 1

Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380 (1991)..................... 1, 15

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980)............... 6

City of Richmond, Virginia v. United States, 422

U.S. 358 (1975).................................................................. 18

City of Lockhart v. United States, 460 U.S. 124

(1983)........................................................................................5

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980) . . . . 14

Connecticut National Bank v. Germain, 503 U.S.

249 (1992)...................................................................... 9

FEA v. Algonquin SNG, Inc., 426 U.S. 548 (1976) . . . . 15

Garcia v. United States, 469 U.S. 70 (1984)................. 13

Georgia v. Reno, 881 F.Supp. 7 (D.D.C. 1995)............... 2

Grove City College v. Bell, 465 U.S. 555 (1984).......... 16

Holder v. Hall, 114 S.Ct. 2581 (1994)....................... ...... 1

Horry County v. United States, 449 F.Supp. 990

(D.D.C. 1978)..................................................................... 18

Houston Lawyers' Association v. Attorney Gen

eral of Texas, 501 U.S. 419 (1991)...................................15

Johnson v. DeGrandy, 129 L.Ed.2d 775 (1994)...................... 9

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Lorillard v. Pons, 434 U.S. 573 (1978).......................... 10

McCain v. Lybrand, 465 U.S. 236 (1984)..................... . 18

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981)................... . 15

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. 2475 (1995)..........1, 13

Mississippi v. Smith, 541 F.Supp. 1329 (D.D.C.

1982), appeal dism'd, 461 U.S. 912 (1983) ................. 6

Mississippi v. United States, 490 F.Supp. 569,

(D.D.C. 1979), aff'd mem., 444 U.S. 1050 (1980)........6

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ............... . 1

NLRB v. Fruit Packers, 377 U.S. 58 (1964) .......... 15

North Haven Board of Education v. Bell, 456 U.S.

512 (1982)........................................................................... 15

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971)........... 9

Shaw v. Hunt, 1996 WL 315870 (U.S. June 13, 1996) . . . . . 1

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) . . . . 17

Texas v. United States, 1995 WL 769160 (D.D.C.

1 9 9 5 ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .................................................... 2

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)

.................................... ................. .......... ... 1, 4, 5, 6, 13, 14

United Jewish Org. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977)........1

United States v. Board of Commissioners of Shef

field, Ala., 435 U.S. 110 (1978)......... 10, 13, 14, 19

United States v. Hays, 115 S.Ct. 2431 (1995).................. 1

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 299 (1976). ......................6

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1972)................. ........... 6

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Wilkes County, Georgia v. United States, 450

F.Supp. 1171 (D.D.C. 1978), aff'd mem., 439 U.S.

999 (1981)..............................................................................7

Zuber v. Allen, 396 U.S. 168 (1969) ........................... ... 13

C o n stitu tio n a l P r o v isio n s :

Fourteenth Amendment..................................................6, 17

Fifteenth Amendment.............................................. .6, 17

S tatutory P r o v isio n s :

Age Discrimination Act of 1975:

42 U.S.C. § 6102.................................................................. 16

42 U.S.C. § 6107.................................................................. 17

Civil Rights Act of 1964:

42 U.S.C. § 2000d.......................................................... 17

28 U.S.C. § 2000d-4..................................... 17

Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987

Education Amendments of 1972:

20 U.S.C. § 1681(a).............................................................16

20 U.S.C. § 1687................................................................ .17

Rehabilitation Act of 1973:

29 U.S.C. § 794.. ......................................................... 16

29 U.S.C. § 794(b)............................................................... 17

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Voting Rights Act of 1965:

42 U.S.C. § 1973, Section 2............5, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

42 U.S.C. § 1973c, Section 5 ...................................passim

42 U.S.C. § 4(f)(4 )..................................................... 10

House and Senate Reports:

H.R. Rep. No. 439, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965).......... 14

H.R. Rep. No. 196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975).. .14, 15

Oversight Hearings on Proposed Changes to Reg

ulations Governing Section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, before the Subcomm. on Civil and

Constitutional Rights of the House Committee

on the Judiciary House of Representatives, 99th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1985)....................... ............................. 12

S. Rep. No. 162, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965)................ 14

S. Rep. No. 295, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1975)............... 15

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982).... 3, 9, 15

S. Rep. No. 64, 100th Cong., 2d Sess. (1987)................. 17

Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights

of the Comm, on the Judiciary U.S. House of

Representatives, 99th Cong., 2d Sess., Voting

Rights Act: Proposed Section 5 Regulations

(Comm. Print 1986 Ser. No. 9 ) ....................... 11,

Voting Rights Act: Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on the Constitution of the Senate Comm, on the

Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982) 10

V I

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

O t h e r :

28 C.F.R. § 51.55(b)(2) ...........................................................12

28 C.F.R. § 51.54(b)(3)............................................................ 7

28 C.F.R. § 51.54(b)(4)..................................... 18

128 Cong. Rec. H3841 ................................... 3, 9

128 Cong. Rec. H3840-41. 3, 9

128 Cong. Rec. S7095 ...... .3, 9

50 Fed. Reg. 19122 (1985)..................................... 12

52 Fed. Reg. 486-90 (1987)................................................. 19

M isc ella n eo u s :

Gayle Binion, "The Interpretation of Section 5 of

the 1965 Voting Rights Act: A Retrospective on

the Role of Courts," 32 W .Pol.Q. 154 (1979)..............7

Richard L. Engstrom, "Racial Vote Dilution:

Supreme Court Interpretation of Section 5 of the

Voting Rights Act," 4 So.U.L.Rev. 139 (1978).............. 7

Mark E. Haddad, "Getting Results Under Section

5 of the Voting Rights Act," 94 Yale L.J. 139

(1984).............................................................. 7

Heather K. Way, "A Shield or a Sword? Section 5

of the Voting Rights Act and the Argument for

the Incorporation of Section 2," 74 Tex.L.Rev.

1439 (1996).................................................................. 11

1

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE1

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a

nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with

nearly 300,000 members dedicated to defending the prin

ciples of liberty and equality embodied in the Constitu

tion and this nation's civil rights laws. As part of that

commitment, the ACLU has been active in defending the

equal right of racial and other minorities to participate in

the electoral process. Specifically, the ACLU has partici

pated in voting cases before this Court, both as direct

counsel, see, e.g., Holder v. Hall, 114 S.Ct. 2581 (1994),

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. 2475 (1995), and as amicus

curiae, see, e.g., United States v. Hays, 115 S.Ct. 2431 (1995).

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. is a nonprofit corporation chartered by the Appellate

Division of the New York Supreme Court as a legal aid

society. The Fund was established for the purpose of

assisting African Americans in securing their constitu

tional and civil rights. See NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415,

422 (1963) (noting Fund's "reputation for expertness in

presenting and arguing the difficult questions of law that

frequently arise in civil rights litigation"). The Fund has

participated in many of the significant constitutional and

statutory voting rights cases in this Court. See e.g., United

Jewish Org. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977); Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986); Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380

(1991); Shaw v. Hunt, 1996 WL 315870 (U.S. June 13, 1996);

and Bush v. Vera, 1996 WL 315857 (U.S. June 13, 1996).

---------- ----- ♦ —-------------

1 Letters of consent to the filing of this brief have been

lodged with the Clerk of the Court pursuant to Rule 37.3.

2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The appeal of this declaratory judgment action under

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act presents two separate

issues: (1) whether the district court erred in holding that

the Bossier Parish School Board carried its burden of pro

ving a lack of discriminatory purpose in enacting its redis

tricting plan, and (2) whether a violation of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act provides an independent basis for deny

ing preclearance under Section 5. Amici agree that, in this

case, it is unnecessary for the Court to reach the second

issue, because the district court majority clearly erred in

applying the purpose prong of Section 5, and its decision

must be reversed on that basis. In the event, however, that

the Court reaches the second issue, this amici brief is

submitted to describe the context and legislative history of

amended Section 2 which clearly demonstrate Congress'

intent to assure that a voting change violating Section 2 of

the Act would not be required to receive preclearance

under Section 5 of the Act. To avoid repetition of the

arguments in the principal briefs, the amici brief is limited

to this latter issue, as to which amici have a special interest

based on their involvement as counsel in past Section 5

cases that have addressed this issue. See Georgia v. Reno,

881 F.Supp. 7 (D.D.C. 1995) (three-judge court); Texas v.

United States, 1995 WL 769160 (D.D.C. 1995) (three-judge

court).

The legislative history of the 1982 amendments and

extension of the Voting Rights Act show that Congress

intended for the results standard of Section 2 to apply to

Section 5 preclearance. Congress was well aware of the

limitations of the retrogression standard of Beer v. United

States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976), when it extended and

3

amended the Act in 1982. The Senate Report that accom

panied the amendments provides that "[i]n light of the

amendment to section 2, it is intended that a section 5

objection also follow if a new voting procedure so dis

criminates as to violate section 2." S. Rep. No. 417, 97th

Cong., 2d Sess. 12 n,31 (1982).

The principal cosponsors of the 1982 amendments,

Senator Kennedy and Representative Sensenbrenner, reit

erated on the floors of the Senate and House during the

legislative debates that "where there is a section 5 sub

mission which is not retrogressive, it would be objected

to only if the new practice itself violated the Constitution

or amended section 2." 128 Cong. Rec. S7095 (daily ed.

June 16, 1982) (remarks of Sen. Kennedy); 128 Cong. Rec.

H3841 (daily ed. June 23, 1982) (remarks of Rep. Sen

senbrenner). Representative Edwards, a sponsor of the

final bill and chair of the House subcommittee with juris

diction over the extension of the Act, concurred with

Representative Sensenbrenner's interpretation of the bill.

128 Cong. Rec. H3840-41.

Congress also acted with knowledge of the Attorney

General's then established practice of denying pre

clearance to changes which violated other provisions of

the Act. When Congress reenacts a statute and voices its

approval of an administrative or other interpretation of

the statute, as it did in the Senate Report, Congress is

treated as having adopted that interpretation, and the

courts are bound by it.

The Senate Report is entitled to greater weight than

any other of the legislative history. This Court has

described the Senate Report as being "the authoritative

4

source" for construction of the 1982 amendments to the

Act. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 43 n.7 (1986). It has

been the established practice of the Court, moreover, to

examine the applicable committee reports to determine

congressional intent and the meaning of specific provi

sions of the Voting Rights Act, particularly Section 5,

where the statute itself was silent or ambiguous.

While Congress did not amend Section 5, it did

amend the Voting Rights Acts and provided that

amended Section 2 was to apply to preclearance. It is

common for Congress to add a provision to an act and

apply it to a second provision of the same act without

changing the language of the second provision.

Some voting changes are not amenable to analysis

under a retrogression standard. A change from appointed

to elected county commissioners, for example, would be

covered by Section 5, but it might be difficult to deter

mine the effect of such a change based upon a retrogres

sion analysis. In other cases, there may be no practice or

procedure at all that can be used as a benchmark for

determining retrogression, e.g., where a newly incorpo

rated college district or municipality selects for the first

time a method of conducting elections. Under the circum

stances, a voting plan which fairly reflects the strength of

the minority community as it exists would furnish the

logical and appropriate basis for comparison.

The application of Section 2 to preclearance would

not cause a major or disruptive change in the administra

tion of Section 5. The Attorney General has administered

the statute in such a manner in the past. The purpose or

effect standards would continue to apply and dispose of

5

the vast majority of submitted voting changes. It would

make very little sense from the standpoint of public pol

icy and conserving judicial resources to allow violations

of one section of the Voting Rights Act (Section 2) to be

approved by another (Section 5). Such a result would

undercut the enforcement mechanisms and the overall

purpose of the Act. The evidence shows that Congress

intended to correct the anomalies of Beer by applying

Section 2 to Section 5 preclearance.

-----------------* --------- -------

ARGUMENT

I. Section 2 Applies to Section 5 Preclearance

The legislative history of the 1982 amendments and

extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973 et seq., make it clear that Congress intended for the

results standard of Section 2 to apply fully to Section 5

preclearance. Accordingly, a covered jurisdiction such as

Bossier Parish would be entitled to preclearance of its

voting changes only if it showed that they did not

"result" in discrimination as that term has been defined

by Congress and the Supreme Court. Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. 30, 35-8, 48-51 (1986).2

2 The issue of the applicability of Section 2 to Section 5 was

presented in City o f Lockhart v. United States, 460 U.S. 124,133 n.9

(1983), but because the district court had not passed on it this

Court declined to grant review in the first instance.

6

A. Interpretation of Section 5 Effects Test Prior to

1982

A majority of the Court, in a divided opinion, held in

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976), that only changes

which were retrogressive or affirmatively diminished

minority voting rights were prohibited by the "effect"

language of Section 5.

Beer, however, was by its own terms ambiguous, for

while the Court adopted a retrogression test, the Court

nonetheless acknowledged that an ameliorative submis

sion would be objectionable under Section 5 if it "so

discriminates on the basis of race or color as to violate the

Constitution." 425 U.S. at 141. Cases cited by the majority

in Beer as illustrative of the applicable constitutional stan

dard included White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1972), which

applied an effect standard in minority vote dilution cases.

See Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 35 (describing White v.

Regester as embodying a "results test").3 Thus, Beer itself

may properly be said to contain an anti-dilution excep

tion to the very retrogression standard which it pur

ported to establish.4

3 Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 299 (1976), and City o f Mobile

v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), which held respectively that proof

of a discriminatory purpose was required for a violation of the

Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments, were decided after Beer.

4 The retrogression standard of Beer was strongly criticized

by legal com m entators. Principal objections were that it

sa n ctio n e d and p e rp e tu a te d vote d ilu tio n , rew ard ed

jurisdictions with the worst histories of discrimination against

minority voters, and largely ignored the legislative history and

underlying purposes of the Voting Rights Act. Gayle Binion,

"The Interpretation of Section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act: A

7

In recognition of its limitations and anomalies, the

courts created a number of exceptions to the strict appli

cation of the retrogression principle. For example, the

District of Columbia court has held that a new legislative

plan cannot be approved, even if it is not retrogressive

compared with the preexisting legislative plan, if it

diminishes minority voting strength when compared with

an intervening court ordered plan. Mississippi v. United

States, 490 F.Supp. 569, 582 (D.D.C. 1979), aff'd mem., 444

U.S. 1050 (1980); Mississippi v. Smith, 541 F.Supp. 1329,

1333 (D.D.C. 1982) (three-judge court), appeal dism'd, 461

U.S. 912 (1983). Preexisting districts that have not them

selves been precleared may also not be used in determin

ing if a submission is retrogressive. Mississippi v. Smith,

541 F.Supp. at 1332. Accord, 28 C.F.R. § 51.54(b)(3).

In Wilkes County, Georgia v. United States, 450 F.Supp.

1171 (D.D.C. 1978) (three-judge court), aff'd mem., 439

U.S. 999 (1981), the court created another important

exception to Beer where an existing plan was malappor-

tioned. Wilkes County, which was 47% black, sought pre

clearance of a change from district to at-large elections. It

argued that the proposed change did not have a discrimi

natory effect within the meaning of Beer because even if

blacks were not able to elect candidates of their choice

Retrospective on the Role of Courts," 32 W.Pol.Q. 154, 171

(1979); Richard L. Engstrom, "Racial Vote Dilution: Supreme

Court Interpretation of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act," 4

So.U.L.Rev. 139, 162 (1978); Mark E. Haddad, "Getting Results

Under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act," 94 Yale L.J. 139 (1984).

8

at-large, neither did they control any of the preexisting

single member districts. The court rejected the county's

argument:

Since the existing districts are severely malap-

portioned, it is appropriate, in measuring the

effect of the voting changes, to compare the

voting changes with options for properly appor

tioned single-member district plans.

450 F.Supp. at 1178. Based upon the census, if Wilkes

County had been divided into fairly drawn single-mem

ber districts of equal population, the black population in

one district could have been as high as 71%. Using the

proper basis for comparison, the court concluded that

blacks were worse off under the change, and that "the at-

large method has . . . a racially discriminatory effect." Id.

B. Congressional Action in 1982

Congress was well aware of Beer and its limitations

when it extended and amended the Voting Rights Act in

1982. In amending Section 2 it incorporated the results

standard for determining the lawfulness of voting prac

tices, and provided that the amended statute was to

apply to Section 5 preclearance. According to the Senate

Report that accompanied the amendments:

Under the rule of Beer v. United States . . . a

voting change which is ameliorative is not

objectionable unless the change 'itself so dis

criminates on the basis of race or color as to

violate the Constitution.' . . . In light of the

amendment to section 2, it is intended that a

section 5 objection also follow if a new voting

procedure so discriminates as to violate section 2.

9

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 12 n,31 (1982)

(citations omitted).5

The principal cosponsors of the 1982 amendments,

Senator Kennedy and Representative Sensenbrenner, reit

erated on the floors of the Senate and House during the

legislative debates that "where there is a section 5 sub

mission which is not retrogressive, it would be objected

to only if the new practice itself violated the Constitution

or amended section 2." 128 Cong. Rec. S7095 (daily ed.

June 16, 1982) (remarks of Sen. Kennedy); 128 Cong. Rec.

H3841 (daily ed. June 23, 1982) (remarks of Rep. Sen

senbrenner). Representative Edwards, a sponsor of the

final bill and chair of the House subcommittee with juris

diction over the extension of the Act, concurred with

Representative Sensenbrenner's interpretation of the bill.

128 Cong. Rec. H3840-41.

Congress also acted with knowledge of the Attorney

General's then established practice of denying pre

clearance to changes which violated other provisions of

the Act. The Attorney General, for example, had consis

tently denied Section 5 preclearance to changes which

violated Section 4(f)(4) of the Act, a provision requiring

5 Given the ambiguity in the effect standard, resort to the

legislative history to determine its meaning is both necessary

and proper. See Connecticut National Bank v. Germain, 503 U.S.

249, 253-54 (1992). The Court has regularly applied this

principle in construing the Voting Rights Act. See, e.g., Johnson v.

DeGrandy, 129 L.Ed.2d 775, 795 (1994); Perkins v. Matthews, 400

U.S. 379, 389 n.8 (1971).

10

certain jurisdictions to implement bilingual voting pro

cedures. Voting Rights Act: Hearings Before the Sub-

comm. on the Constitution of the Senate Comm, on the

Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 1659 (1982) [hereinafter

Voting Rights Act Hearings (1982)]. This interpretation of

Section 5 was reported to Congress by William Bradford

Reynolds, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights,

when it considered the extension and amendment of the

Act in 1982. Voting Rights Act Hearings (1982) at 1659,

1720.

In its discussion of Beer, the Senate Report also noted

and approved the Attorney General's practice of not

applying a strict retrogression test, but treating submis

sions "on a case-by-case basis, 'in light of all the facts.' "

S. Rep. No. 417 at 12 n.31. When Congress reenacts a

statute and voices its approval of an administrative or

other interpretation of the statute, as it did in the Senate

Report, "Congress is treated as having adopted that inter

pretation, and the Court is bound thereby." United States

v. Board of Commissioners of Sheffield, Ala., 435 U.S. 110, 134

(1978). Accord, Lorillard v. Pons, 434 U.S. 573, 580 (1978)

("Congress is presumed to be aware of an administrative

or judicial interpretation of a statute and to adopt that

interpretation when it re-enacts a statute without

change").

Congress further confirmed its intention that Section

2 standards were to apply to preclearance when it con

ducted oversight hearings in 1985 on the Attorney Gen

eral's proposed revisions of the regulations governing

Section 5. According to the House Report, "the Subcom

mittee concludes that it is a proper interpretation of the

legislative history of the 1982 amendments to use Section

11

2 standards in the course of making Section 5 determina

tions." Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights

of the Comm, on the Judiciary U.S. House of Representa

tives, 99th Cong., 2d Sess., Voting Rights Act: Proposed

Section 5 Regulations 5 (Comm. Print 1986 Ser. No. 9)

[hereinafter Comm. Print (1986)].6

The lower court's observation that Section 2 and

Section 5 are "different," App. 15a, is a non sequitor. The

sections are different. The issue, however, is whether

Section 2 standards are to be applied in Section 5 pre

clearance. The legislative history indicates that they

should be.

C. The Attorney General's Regulations

In light of the 1982 amendments, the Attorney Gen

eral adopted regulations in 1987 calling for the applica

tion of Section 2 standards to Section 5 preclearance. The

regulations, which were widely circulated prior to their

6 Follow ing those h earin gs, prom inent m em bers of

C o n g re ss e n d o rse d th is c o n s tru c tio n of the A ct in

correspondence addressed to the Attorney General following

rumors that the Department of Justice would abandon the

application of Section 2 standards in the Section 5 review

process. Senator Dole, for example, stated that he had " 'a vital

interest in assuring that the Voting Rights Act is interpreted

. . . consistent with Congress' intent. Preclearing voting changes

that violate Section 2 would threaten the integrity of Section 5 as

a barrier to all illegal voting discrimination and be in direct

conflict with the law's legislative history.' " See Heather K. Way,

"A Shield or a Sword? Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act and the

Argument for the Incorporation of Section 2", 74 Tex.L.Rev. 1439,

1468 (1996) (quoting this and other letters).

12

promulgation7 and were the subject of Congressional

hearings, see Oversight Hearings on Proposed Changes to

Regulations Governing Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act,

before the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional Rights

of the House Committee on the Judiciary House of Repre

sentatives, 99th Cong., 1st Sess. (1985) [hereinafter Over

sight Hearings], provide that:

In those instances in which the Attorney Gen

eral concludes that, as proposed, the submitted

change is free of discriminatory purpose and

retrogressive effect, but also concludes that a

bar to implementation of the change is neces

sary to prevent a clear violation of amended

Section 2, the Attorney General shall withhold

Section 5 preclearance.

28 C.F.R. § 51.55(b)(2).

Since the 1982 amendments and the promulgation of

the regulations, the Attorney General has continued to

object to submissions if they violated Section 2. See

Comm. Print (1986) at 4; Oversight Hearings (1985) at

210-12, 229-34 (describing Section 5 objections in 1983 to

redistricting plans from Amite and Oktibbeha Counties,

Mississippi on the grounds that they violated amended

Section 2). While the regulations and decisions of the

Attorney General are not binding upon the courts, the

contemporaneous administrative construction of the Act

by the Attorney General is persuasive evidence of the

intent of Congress in enacting the 1982 amendments.

7 The regulations were published in proposed form for

comment. 50 Fed. Reg. 19122 (May 6, 1985).

13

United States v. Board of Commissioners of Sheffield, Ala

bama, 435 U.S. at 131.8

D. The Legislative History Cannot Be Discounted

Despite the evidence noted above, the court below

held that Section 2 does not apply to Section 5 because

the legislative history is not extensive. App. 17a. The

Senate Report, as the report commended to the full Sen

ate and representing the collective understanding of the

members involved in drafting and studying the proposed

legislation, is entitled to greater weight than any other of

the legislative history. See Garcia v. United States, 469 U.S.

70, 76 n.3 (1984) ("the authoritative source for finding the

legislature's intent lies in the Committee Reports on the

bill, which 'represent] the considered and collective

understanding of those Congressmen involved in draft

ing and studying proposed legislation,' " quoting Zuber v.

Allen, 396 U.S. 168, 186 (1969); American Jewish Congress v.

Kreps, 574 F.2d 624, 629 n.36 (D.C.Cir. 1978) ("[s]ince the

conclusions in the conference report were commended to

the entire Congress, they carry greater weight than other

of the legislative history"). In addition, the Supreme

Court has described the Senate Report as being "the

authoritative source" for construction of the 1982 amend

ments to the Act. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 43 n.7.

8 In Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. 2475, 2493 (1995), the Court

confirmed the retrogression standard of the effect prong of

Section 5, but the issue of the incorporation of Section 2

standards into preclearance was not presented, and thus not

decided, in Miller.

14

In Thornburg v. Gingles, the amicus supporting the

appellants argued that the report represented "a compro

mise among conflicting 'factions/ and thus is somehow

less authoritative than most Committee Reports." 478

U.S. at 43 n.7. The Supreme Court rejected the claim.

We are not persuaded that the legislative history

of amended § 2 contains anything to lead us to

conclude that this Senate Report should be

accorded little weight. We have repeatedly rec

ognized that the authoritative source for legisla

tive intent lies in the Committee Reports on the

bill.

Id. The Court went on to rely extensively on the Senate

Report and cited it numerous times in construing

amended Section 2. 478 U.S. at 43-8.

It has been the established practice of the Court,

moreover, to examine the applicable committee reports to

determine congressional intent and the meaning of speci

fic provisions of the Voting Rights Act, particularly Sec

tion 5, where the statute itself was silent or ambiguous. In

Beer, in determining how to measure discriminatory

effect, as to which Section 5 itself was silent, the Court

relied mainly upon the House Report of the 1975 exten

sion of the Act. 425 U.S. at 141 (citing H.R. Rep. No. 196,

94th Cong., 1st Sess. 60 (1975)). In City of Rome v. United

States, 446 U.S. 156, 168-69 (1980), the Court resolved the

question whether individual jurisdictions could bailout

from Section 5 coverage by examining the House and

Senate Reports. 446 U.S. at 168-69 (citing H.R. Rep. No.

439, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965), and S. Rep. No. 162, 89th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1965)). In United States v. Board of Com

missioners of Sheffield County, Alabama, in concluding that

15

subjurisdictions were subject to preclearance by virtue of

statewide Section 5 coverage, the Court found partic

ularly "significant" the discussion of the issue in the

House and Senate reports. 435 U.S. at 134 (citing S. Rep.

No. 295, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 12 (1975), and H.R. Rep. No.

196 at 5). In McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981), the

Court discussed the 1975 committee reports at length in

holding that any voting change, including those ordered

into effect by a local federal court, which reflects the

policy choices of elected officials is subject to Section 5.

452 U.S. at 146-51 (citing S. Rep. No. 295 and H.R. Rep.

No. 196). In Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380, 393-394 ns.20,

21, 395 n.22 (1991) (citing S. Rep. No. 417), and Houston

Lawyers' Association v. Attorney General of Texas, 501 U.S.

419 (1991), the Court found that state appellate and trial

court judges were "representatives" within the meaning

of Section 2 based, inter alia, upon the 1982 Senate Report.

Clearly, there is no basis for contending that the Section 2

incorporation argument fails because it relies primarily

upon the Senate Report, App. 17a; the report is the

authoritative source of construction of the Act.

The claim that the legislative history is not extensive

also discounts the fact that the principal cosponsors of

the 1982 amendments stated during the floor debates that

Section 2 was to apply to preclearance. Because these

members of Congress were sponsors and principal archi

tects of the 1982 amendments, their views "deservje] to

be accorded substantial weight." NLRB v. Fruit Packers,

377 U.S. 58, 66 (1964); North Haven Board of Education v.

Bell, 456 U.S. 512, 527 (1982) (the statements of a sponsor

of a bill "are an authoritative guide to the statute's con

struction"); FEA v. Algonquin SNG, Inc., 426 U.S. 548, 564

16

(1976). Every time the issue was directly addressed - in

the debates and in the Senate Report - the conclusion was

that Section 2 was applicable to Section 5.9

E. Congress Did Amend the Voting Rights Act

The lower court also held that Congress did not

intend to import Section 2 standards into Section 5

because it did not amend the latter statute. App. 20a.

Congress did, however, amend the Voting Rights Act and

provided that amended Section 2 was to apply to pre

clearance.

It is common for Congress to add a provision to an

act and apply it to a second provision of the same act

without changing the language of the second provision.

For example, Congress enacted the Civil Rights Restora

tion Act of 1987 in response to Grove City College v. Bell,

465 U.S. 555 (1984),10 to amend four pre-existing civil

rights acts, i.e., Title IX of the Education Amendments of

1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1681(a); Section 504 of the Rehabilitation

Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. § 794; the Age Discrimination Act

of 1975, 42 U.S.C. § 6102; and, Title VI of the Civil Rights

9 That the floor debate was limited is not surprising in view

of the fact that Section 5 preclearance (as opposed to its

duration) was not a very controversial issue. It was the

am endm ent of Section 2 that absorbed the attention of

Congress. Comm. Print (1986) at 4.

10 Grove City held that discrimination in a "program or

activity" of a college didn't subject the institution as a whole to

the nondiscrimination provisions of Title IX of the Education

Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. § 1681(a).

17

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d, and provide that discrimi

nation was prohibited throughout entire institutions or

agencies if any part received federal financial assistance.

The Civil Rights Restoration Act did not, however, make

any changes or add any language to the coverage or fund

termination provisions of the pre-existing acts. S. Rep.

No. 64, 100th Cong., 2d Sess. (1987). Moreover, in three of

the four instances, amendment was accomplished by

adding an entirely separate provision defining the term

"program or activity" in a broad, institution-wide man

ner. Title IX was amended by 20 U.S.C. § 1687; the Age

Discrimination Act was amended by 42 U.S.C. § 6107;

and, Title VI was amended by 28 U.S.C. § 2000d-4. In only

one instance was the statute creating the prohibition of

discrimination itself amended, the Rehabilitation Act of

1973, 29 U.S.C. § 794(b).

Congress did the same thing when it enacted the

1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act as it did when

it passed the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 amend

ing the pre-existing civil rights statutes. It did not add

new language to Section 5, but instead amended Section 2

and provided in the legislative history that Section 2 was

to apply to preclearance. Given its broad authority to

enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments by

appropriate legislation, South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383

U.S. 301, 326-27, 337 (1966), Congress did not exceed its

powers in acting as it did.

18

F. Some Voting Changes Are Not Amenable to

Analysis Under the Retrogression Standard

The argument that the anti-dilution standard of Sec

tion 2 does not apply to Section 5 does not take proper

account of the fact that the effect of some voting changes

is simply not amenable to analysis under a retrogression

standard. A change from appointed to elected county

commissioners, for example, would be covered by Section

5, McCain v. Lybrand, 465 U.S. 236, 250 n.17 (1984), Horry

County v. United States, 449 F.Supp. 990, 995 (D.D.C. 1978),

but it might be extremely difficult to determine the effect

of such a change based upon a retrogression analysis. If

the change were to at-large elections or single-member

districts which fragmented the minority community and

diluted its voting strength, would it nonetheless be enti

tled to preclearance if under the old system no minorities

had been appointed to the commission, and there was no

evidence that the change was racially motivated? The

difficulty with retrogression analysis under these circum

stances is that there is no pre-existing electoral system

which can be used as a basis for comparing the effect of

the new practice.

In other cases, there may be no practice or procedure

at all that can be used as a benchmark for determining

retrogression, e.g., where a newly incorporated college

district or municipality selects for the first time a method

of conducting elections. See 28 C.F.R. § 51.54(b)(4). Under

the circumstances, a voting plan which "fairly reflects"

the strength of the minority community as it exists would

furnish the logical and appropriate basis for comparison.

City o f Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358, 378 (1975).

19

The application of Section 2 to preclearance would

not cause a major or disruptive change in the administra

tion of Section 5. Indeed, the Attorney General has

administered the statute in such a manner in the past.

The purpose or effect standards would continue to apply

and dispose of the vast majority of submitted voting

changes. According to the Attorney General, during his

review of the thousands of voting changes submitted

since the 1982 amendments, "only a handful . . . even

arguably presented th[e] possibility" of being disposed of

on Section 2 grounds. 52 Fed. Reg. 486-90 (1987) (com

ments to 28 C.F.R. § 51). In those relatively rare - but

important - cases where a retrogression analysis was not

applicable, or where a voting change which did not have

a d iscrim inatory purpose or effect nevertheless

"resulted" in discrimination, an anti-dilution standard

should apply.

It would make very little sense from the standpoint

of public policy and conserving judicial resources to

allow violations of one section of the Voting Rights Act

(Section 2) to be approved by another (Section 5). Such a

paradigm would undercut the enforcement mechanisms

and the overall purpose of the Act.11 The evidence shows

that Congress intended to correct the anomalies of Beer by

applying Section 2 to Section 5 preclearance.

-----------------♦ -----------------

11 See Sheffield, 435 U.S. at 136 ("The only recourse available

would be the one Congress found to be unsatisfactory: repeated

litigation").

20

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision below should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

L a u g h lin M cD o n a ld

N eil B ra dley

M a h a S. Z aki

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

44 Forsyth St. NW - Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

S tev en R. S h a piro

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

(212) 944-9800

E la in e R. J on es

Director-Counsel

N o rm a n J . C h a ch kin

J a c q u elin e B errien

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900