Ford v. United States Steel Corporation Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 16, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. United States Steel Corporation Brief for Appellants, 1978. 090ce933-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d8abc69b-740f-4c13-b7b8-6613caec507e/ford-v-united-states-steel-corporation-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 19, 2026.

Copied!

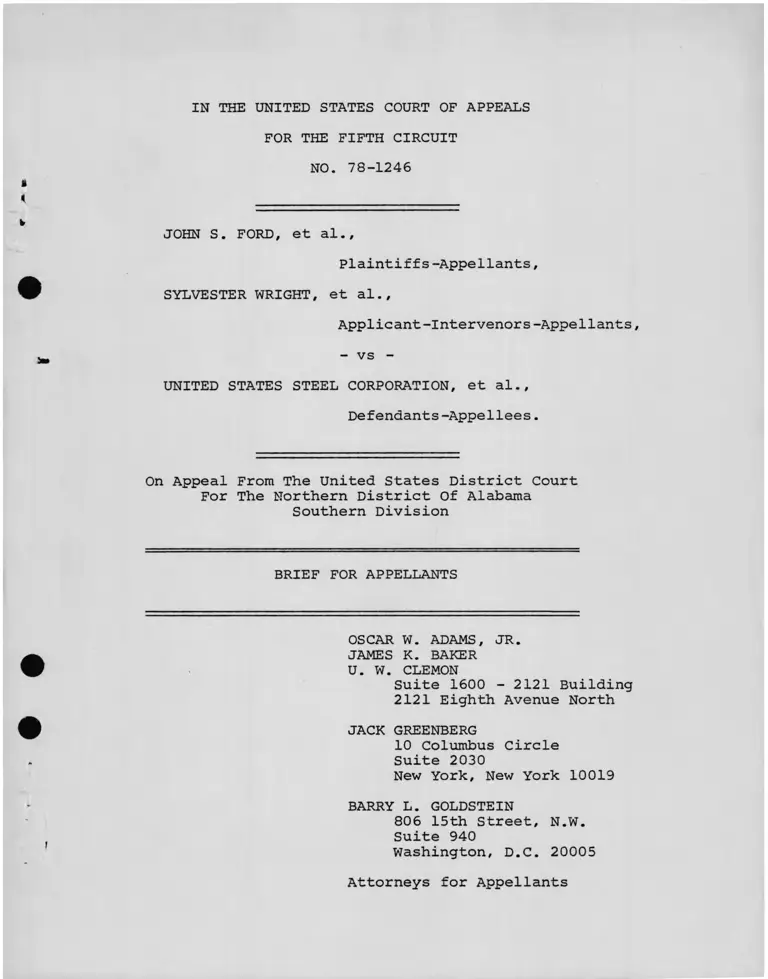

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 78-1246

JOHN S. FORD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

SYLVESTER WRIGHT, et al.,

Applicant-Intervenors-Appellants,

- vs -

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Northern District Of Alabama

Southern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

OSCAR W. ADAMS, JR.

JAMES K. BAKER

U. W. CLEMON

Suite 1600 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

JACK GREENBERG

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 78-1246

JOHN S. FORD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

SYLVESTER WRIGHT, et al.,

Applicant-Intervenors-Appellants,

-vs -

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Alabama

Southern Division

CERTIFICATE

The undersigned counsel for plaintiffs-appellants Ford, et al.,

in conformance with Local Rule 13 (a), certifies that the following

listed parties have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that Judges of this Court may

evaluate possible disqualification or recusal:

1. JOHN S. FORD, WILLIE CAIN, WILLIE L. COLEMAN,

JOE N. TAYLOR, ROBERT CAIN, DAVID BOWIE, and

EARL BELL, plaintiffs;

2. The class of black workers of United States Steel

Corporation, whom plaintiffs represent;

3. SYLVESTER WRIGHT, WESTLEY JOE CHAMBLIN, LEROY JONES,

JIMMIE BENISON, SAM CROOM, MILTON GIVAN, MORRIS

CHANEY, JR., WOODROW WILSON, BEN HUDSON, JESSIE

BANKS, SIMMIE LAVENDER, SCILLIE WILDERS, GEORGE O.

ALEXANDER, JUNIOUS DAVIS, JR., JIMMY DUNSON, DAVE

YOUNG, WILLIE G. RUCKER, FRANK TURNER, W. A.

ARMSTRONG, LUCIOUS FITZPATRICK, W. L. McMICKENS,

NED CRAWFORD, HENRY HINKLE, JOHN T. MILES, CHARLES

L. PETERSON, MUNICH KINE, SENIOUS MARTIN, GEORGE

McNEIR, CLARENCE GILBERT, LLOYD ALEXANDER, KING

SMITH, WASHINGTON JOHNSON, JAMES LEO MONTGOMERY,

and HENRY FIELD, would be intervenors;

4. United States Steel Corporation, defendant;

5. United Steelworkers of America, defendant;

6. United Steel Workers of America, AFL-CIO Local Unions

6612, 1013, 1733, 2405, 2122, 1380, 1131, 1489, 1700,

2210, 2421, 2927, 3662, and 4203, defendants.

Attorney for Appellants

-2-

I N D E X

Table of Authorities ................................ 3-

Statement of Questions Presented ................... i-v

Page

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. The Private Litigation ................... 2

B. The Justice Department Suit and

Consolidated Trial ....................... 5

C. The May, 1973 Decree .................... 6

D. The August 10, 1973 Final Judgment 8

E. The Entry of Nationwide Steel Consent 9

F. The 1976 Decision of this Court and Remand.. 10

ARGUMENT

Summary of Argument

I. The District Court Erred in Awarding

Attorneys' Fees to the Defendants. ...... 12

II. The District Court Erred When It Decertified

the Class on the Basis that the Plaintiffs

Did Not Have the Necessary "Nexus" With the

Class Members. ........................... 12

III. The District Court Erred When It Failed to

Follow the Established Law of the Case and

Decertified the Class........................ 13

•>H The District Court Erred when It Denied

Intervention. ......................... 14

A. Timeliness .........................

B. Intervention is Proper under Rule 24(a)(2)

and Rule 24(b). ......................

CONCLUSION 51

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

American Pipe & Construction Co. v. Utah,

414 U.S. 538 ( 1974)......................... 41-2

Bolton v. Murray Envelope Corp., 553 F .2d

881 ( 5th Cir . 1977)......................... 13,28,

30, 33

Christianburg Garment Co. v. Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, 98 S.Ct. 694

(1978)......................................... 12,16

East Texas Motor Freight v. Rodriquez, 431 U.S.

395 ( 1977).................................. 18

EEOC v Datapoint Corp., No. 76-2862 (5th

Cir. April 7, 1978)......................... 16

EEOC v. United Airlines, Inc., 515 F . 2d

946 ( 7th Cir. 1975)......................... 46

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company,

424 U.S. 747 (1976)......................... 19

Glus v. G.C. Murphy, 562 F .2d 880

(3rd Cir. 1977)............................. 44

Hardy v. United States Steel Corporation,

289 F.Supp. 200 (N.D. Ala. 1967)........... 4

Hodgson v. United Mine Workers of America,

473 F . 2d 118 ( 1972)......................... 48

Huff v. N.D. Cass Co., 485 F.2d 710

(5th Cir. 1973) (en banc)................. 17

Jenkins v. United Gas Corporation, 400

F. 2d 28 ( 5th Cir. 1968).................... 17

Lehrman v. Gulf Oil Corporation, 500 F .2d

659 (5th Cir. 1974)........................... 13,28-9

Lopez v. Arkansas County Independent School

District, 570 F.2d 541 (5th Cir.

1978)........................................ 16

- i -

Page

Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corporation,

398 F . 2d 496 ( 5th Cir. 1968)............... 17-8

Philadelphia Elec. Co. v. Anacanda American

Brass Co., 43 F.R.D. 452 (E.D.

Pa. 1968)................................... 38

Romasanta v. United Airlines, 537 F .2d 915

( 7th cir . 197 6 )............................. 41

Satterwhite v. City of Greenville, 557

F. 2d 414 (5th Cir. 1977)................... 13,19-20

Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558 F .2d

257 (5th Cir. 1977)......................... 14, 35,38-9

Stevenson v. International Paper Company,

432 F . Supp .39 0 (W.D. La. 1977)............. 44-5

Terrell v. Household Goods Carriers' Bureau,

494 F. 2d 16 (5th Cir. 1974)................ 29

Terrell v. U.S. Pipe & Foundry Co., 7 E.P.D.

para. 9055 (N.D. Ala. 1973)............... 44

United Airlines, Inc. v. McDonald, 432 U.S.

385 (1977).................................. 14,17,35-8,40-1,48

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

517 F .2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975)

cert denied 96 S.Ct. 1684 ( 1976)........... 9, 18

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

558 F.2d 742 (5th Cir. 1977)

reh. granted 568 F. 2d 1073 (1978).......... 12,15,45-7

49

United States v. United States Steel

Corporation, 520 F .2d 1043 (5th Cir.

1975) reh. denied 525 F.2d 1214

cert denied 429 U.S. 817 ( 1976)............ passim

United States v. United States Steel

Corporation, 371 F.Supp. 1045

(N.D. 1973)................................. 3,9

11

United States v. United States Steel

Corporation, 5 EPD para. 8619

(N.D. Ala. 1973).............

Page

United States v. United States Steel

Corporation, 6 EPD para. 8790

(N.D. 1973)........................

United States v. Trucking Employers, Inc.,

561 F.2d 313 (D.C. 1977)...........

Walker v. Providence Journal Company,

493 F.2d 82 (1st Cir. 1974).......

Wheeler v. American Home Products, 563

F.2d 1233 ( 5th Cir. 1977).........

White v. Murtha, 377 F.2d 428 (5th

Cir. 1967)..........................

Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Co., 468

F. 2d 1201 (2nd Cir. 1972)

cert denied 411 U.S. 931 (1973)....

Zargaur v. United States, 493 F .2d 447

(5th Cir. 1974)....................

6,8

9

47

34

43

29

47

29

Statutes and Other Authorities

28 U.S.C. §1291 ...........................

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq.m i ___

(as .. passim

Rule

amenaea

23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ..... 18-9,30,

Rule 24, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure......

48-9

Rule 25, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure..... . 34

i n

Statement of Questions Presented

1. Whether the district court erred in awarding attorneys' fees

to the defendants?

2. Whether the district court erred in decertifying the

class because the Ford plaintiffs did not have a proper

"nexus" with the class members?

3. Whether the district court erred in reversing its prior

decision certifying the class which was reviewed by

this Court and Supreme Court because the certification

decision was the "law of the case"?

4. Whether the district court erred in denying intervention

because it was not timely sought?

5. Whether the district court erred in determining that the

intervention was not one of right pursuant to Rule 24(a)(2)

or in exercising its discretion to deny intervention

pursuant to Rule 24(b)?

- iv -

J

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 78-1246

JOHN S. FORD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

SYLVESTER WRIGHT, et al.,

Applicant-Intervenors-Appellants,

vs.

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Alabama

Southern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal involves, as this Court has previously-

described, "a sharply-contested employment discrimination

1/case." The district court on October 13, 1977 reversed

its decision, made in 1973 and decertified the class

represented by the plaintiffs-appellants (R53-62) and

1/ 520 F.2d 1043, 1047, reh. denied 525 F.2d 1214 cert,

denied 429 U.S. 817 (1976)

entered a Final Judgment dismissing the action (R63).

On December 19, 1977, the district court denied the Motion

to Alter or Amend the Judgment, the Motion to Intervene

and the Motion for a Substitution of Named Plaintiffs.

(R61-83). A timely notice of appeal was filed; this Court

has jurisdiction of the appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1291.

The Ford action is but a part of the litigation con

cerning the integration of the racially separate and unequal

employment system at the massive Fairfield Works of the

United States Steel Corporation, 520 F.2d at 1047-48. This

appeal involves the interrelation of the several actions

filed by black employees and the United States pursuant to

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; accordingly,it

is necessary to describe in some detail the development of

that litigation.

A. The Private Litigation

Shortly after Title VII became effective on July 2,

1965, black employees filed charges with the EEOC. These

charges led to a series of lawsuits. In 1966, three law

suits, Hardy, McKinstry and Ford were filed by the same

counsel who represent the Ford class and Wriqht intervenors

2/

on this appeal. These three actions were brought on behalf

of classes of black employees at the Fairfield Works facility

of United States Steel Corporation. There are nine "plants"

2/ Oscar Adams, Jr. of Birmingham and Jack Greenberg have

represented the plaintiffs in these cases since 1966. Over

the course of the years they have associated additional counsel.

2

within the Fairfield Works complex which together "form

a single interrelated steel producing operation." United

States v. United States Steel Corporation, 371 F.Supp. 1045,

1049 (N.D. Ala. 1973). The United Steelworkers of America

represent employees throughout all of the plants but there

3/are separate Locals which represent employees in each plant.

In retrospect the class definitions contained in the

1966 Hardy, McKinstry and Ford complaints were ambiguous.

The plaintiffs in both Hardy and McKinstry alleged that they

represented all blacks at United States Steel Corporation's

facilities in Fairfield. However, in another section of

those complaints the classes of black employees were said to

include those blacks who were members of Local 1489 (Hardy)

and Local 1013 (McKinstry). The complaint in Ford restricted

4/the class to black workers who were members of Local 1733.

These class allegations if read broadly would, of course,

include all the black workers at Fairfield Workers. However,

even if these class allegations were read narrowly as includ

ing only the black workers in Locals 1489, 1013 and 1733 the

joint classes would include over 70% of the black workers

1/

at Fairfield Works.

3/ Appendix A attached to this brief lists each of the nine

plants and the Local Union of the Steelworker which was establish

ed at each plant by the International Union.

4/ Appendix B lists the private suits by date of filing and

class definition.

5_/ All of the workers at the two largest plants at Fairfield

Works, Fairfield Steel Plant and Ensley Steel Plant, were

represented by Locals 1013 and 1489 respectively.

3

In any case the original class allegations were severely

restricted in 1967 by the district court (by the Honorable

Seybourn H. Lynne). Judge Lynne noted that the Hardy and

McKinstry class allegations were "not clear" and that they

could be read to include all of the black workers at Fairfield

Works or just those black workers included in the specified

local unions, Hardy v. United States Steel Corporation, 289

F. Supp. 200, 202 (N.D. Ala. 1967). But Judge Lynne limited

the class definitions in the Ford, Hardy and McKinstry actions

6/

to single departments in the Rail Transportation, Ensley

Steel and Fairfield Steel plants. However, Judge Lynne ruled

that the order limiting the class definition was "without

prejudice to whatever rights plaintiffs may have to amend or

change the designation of the class which they seek to represent,

during the pendency of this action, for proper cause shown."

!_/

Id. at 203.

Subsequently, three additional private suits were brought

from 1967 to 1969 on behalf of black workers: Brown v. U.S.

Steel Corporation, United Steelworkers of America; Love v .

United States Steel Corporation, United Steelworkers of America,

5/ contd.

Appendix C lists the number of white and black workers,and

their average hourly wage, by plant as of 1971.

6/ Each plant was subdivided into departments.

7/ The opinions entered by Judge Lynne in Ford and McKinstry

are, as a practical matter, identical to the one entered in

Hardy. The opinions in Ford and McKinstry were not reported.

Of course, Judge Lynne's Order limiting the definition

of the classes was interlocutory and not appealable.

4

Local 1489 and 1013 of the United Steelworkers of America;

and Donald v. United States Steel Corporation, Local 1013

and the United Steelworkers of America. As in the Ford,

McKinstry and Hardy suits, the Brown, Love and Donald

complaints alleged, inter alia, that the assignment, seniority

and promotional practices of the defendants violated Title VII

and sought adequate remedy.

B. The Justice Department Suit and Consolidated Trial

On December 11, 1970, the United States filed a "pattern

and practice" lawsuit against United States Steel Corporation,

the United Steelworkers of America and each of the Steelworkers '

Locals at Fairfield Works. The complaint alleged broad

patterns of discrimination in, inter alia, hiring, assignment,

promotion and in the application of the seniority system

against all black employees at Fairfield Works. On June 17,

1971 during a pre-trial conference the Honorable Sam C.

Pointer consolidated the Justice Department's pattern and

practice suit with the private suits. The court further

delineated appropriate pre-trial discovery and other procedures

including the appointment of Oscar Adams as liaison counsel

9/

for plaintiffs' attorneys. The trial of the consolidated

8/ See Appendix B.

An additional lawsuit, Johnson v. United States Steel

Corporation, alleged that the defendant maintained segregated

facilities; this suit was found by the district court to be

moot. One lawsuit, Fillingame v. United Steel Corporation,

et al. was filed by white employees and involved a claim of

unfair representation; the district court held that the suit

was unsupported by the evidence, 5 EPD para. 8619 at 7823

_9/ As part of the court's assignment as liaison counsel,

attorney Adams in the Ford, McKinstry and Hardy litigation

5

actions commenced on June 20, 1972 and continued on a

intermittent basis for six months. The Record was joint,

evidence introduced in any one of the cases applied to all

of the cases; the district court described the trial as

follows, 371 F.Supp. at 1048:

In December 1972 — after hundreds of witnesses,

more than 10,000 pages of testimony, and over

ten feet of stipulations and exhibits (the bulk

being in computer or summary form) — the parties

rested.... Trial would have been even more

prolonged but ... for the very professional atti

tude of all counsel in expediting trial (fn. omitted).

C. The May, 1973 Decree

On May 2, 1973, the district court entered a Decree

of over 150 pages. The Decree applied to both the private

actions and the pattern and practice suit; the court entered

a general injunction, as well as extensive provisions cover

ing changes in the seniority system, inter-plant transfer,

training opportunity, and other specific remedial relief. The

Decree also held that six private actions were "due to be

maintained as class actions ... in each the prerequisites

of Federal Rule 23(a) are satisfied and that in addition the

provisions of Federal Rule 23(b) are applicable."

Most importantly for this appeal the district court

held the following definition of the Ford class appropriate,

5 EPD para. 8619 at 7822 :

9/contd.

undertook to coordinate pre-trial discovery and attorney Adams

or one of his partners attended each day of the over 50 trial

days regardless of whether the evidence presented on that day

pertained directly to the class employees which they represented pursuant to the Order entered by Judge Lynne.

6

"... all black persons who have at any time

prior to January 1, 1973, been employed in

the former Pratt City Car Shop line of pro

motion; and, for the purposes of this Decree,

the plaintiffs herein represent a class

consisting of all black persons who have at

any time prior to January 1, 1973, been

employed at the Fairfield Works (except to

the extent they may be otherwise included as

a class member under sub-paragraphs (a)

through (f) [that is, Blacks who had been

included in any of the private class actions]

II

The district court made this ruling sua sponte in order "to

assure that its ruling adverse to back pay claims of such

persons could be reviewed by the Court of Appeals." (R55)

However, it is important to emphasize that prior to the

issuance of the May 2, Decree, Oscar Adams had informed the

district court in the presence of counsel for the defendants

that his clients, black workers who were employed throughout

10/

Fairfield Works, had authorized him to pursue a back pay

remedy on their behalf. This discussion took place at a

chambers conference immediately preceding the May 2, Decree.

Judge Pointer at this conference indicated his intent to

deny back pay to all black workers except those in the narrowly-

defined Ford, McKinstry and Hardy classes. At that time it

was not clear, as Judge Pointer indicated in his October 13,

1977 Opinion, whether the government would appeal the ruling.

(R55)

10/ Oscar Adams and his associate counsel had been regularly

meeting with an organization of black steelworkers employed at

Fairfield Works, the Ad Hoc Group, which had been instituted

prior to 1965 to achieve equal employment opportunity; see infra

at 26-7 for a further discussion of the Ad Hoc Group. In

addition Oscar Adams in his position as liaison counsel for

plaintiffs 1 attorneys had repeatedly met with black workers at

Fairfield Works and the other attorneys who represented the

Donald, Love and Brown classes.

7

Following Judge Pointer's announcement of his intended

ruling, attorney Adams stated that (1) the plaintiffs in

the private actions had maintained that they represented a

broad cross-section of black workers at Fairfield Works

and (2) that, in any case, his clients were going to seek

to insure that their back pay claims were pressed by the

institution of a new lawsuit. Subsequently, Judge Pointer

declared, "sua sponte" that a new lawsuit would be unnecessary

and that the Ford plaintiffs (or indeed the Hardy and McKinstry

plaintiffs) could properly represent a class of black workers

throughout Fairfield Works.

The May 2, 1973 decree was not final and appealable, 5 EPD

para. 8619 at 7823. The district court had indicated that

some class members of the Hardy, McKinstry and Ford (car-shop

11/class ) were entitled to back pay but that further evidence

and hearings were necessary in order to determine who in the

class was entitled to back pay and in what amount.

D. The August 10, 1973 Final Judgment and Appeal

After the May 2 Decree, the court during an in-chambers

conference determined an appropriate formula for computing

back pay in the three private actions. After defendant

United States Steel Corporation provided through informal

discovery proceedings sufficient information to implement

the proposed formula, a hearing was held on August 6, 1973

11/ The narrow Ford class preliminarily determined in 1967

by Judge Lynne is listed as the "Car-Shop class" whereas the

1973 certification by Judge Pointer is listed simply as the

Ford class.

8

to apply the formula and to determine any appropriate changes.

After evidence and argument was presented. Judge Pointer made

several changes in the formula for calculation of back pay,

371 F.Supp. at 1060. Four days later the court issued a Final

Judgment establishing the precise back awards; 33 out of the

37 members of the Ford Car-Shop class received an award of back

pay totaling $112,033.06, 6 E.P.D. para. 8619.

The Ford plaintiffs filed a timely notice of appeal

from the Final Judgment. Of course, it was unnecessary for

the black workers who had been originally included in the Hardy

and McKinstry class definitions to appeal from the limitation

on the class in these cases because they were now represented

in the Ford case. The United States also appealed the court's

denial of back pay and the appeals were consolidated.

E . The Entry of Nationwide Steel Consent Decree

During the pendency of the consolidated appeals, the

United States on April 10, 1974 entered into a consent decree

with United States Steel Corporation, nine other steel companies

and the United Steelworkers of America providing a remedy,

injunctive and back pay, for practices of race and sex dis-

12/crimination. The consent decree applied to Fairfield Works

13/

and some members of the Ford class. Several hundred members

of the Ford class who were tendered settlement under the consent

12/ See United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, 517 F.2d

82*6 (5th Cir. 1975) cert, denied 96 S.Ct. 1684 (1976) for a full

description of the consent decrees.

_13/ The Ford class includes black workers who were ineligible

for tenders under the consent decree: black employees who left

employment prior to April 12,1972, who were hired after January 1,

1968, or who retired after April 12, 1972 but not on pension. (R 72)

9

clecree rejected the tender in reliance on the district court

14/

certification of the Ford class.

The United States dismissed its appeal in favor of the

consent decree.

F. The 1976 Decision of this Court and Remand

This Court reversed the district court's denial of back

pay to black workers and held that "we reject [the company s]

argument that appellant Ford lacks standing as a matter of law

to represent any class of black employees broader than the

'original' Ford class, in which his personal back pay claim has

---- 15/

been satisfied," 520 F.2d 1043, 1052. The action was remanded

for "further proceedings consistent with [the] opinion and other

controlling authority."

On remand, the Ford plaintiffs acted to both insure the

effective enforcement of the injunctive sections of the decree

and commenced formal and informal discovery proceedings

consistent with the remand order to prepare for trial on the

16/

14/ The district court questioned "whether, in the interest of

justice, this court ... should on motion require a re-tender

[under the consent decree]...." (R60 N.9)

15/ The Court's opinion is discussed extensively in Argument III,

infra.

16/ On numerous occasions counsel for plaintiffs have represented

members of the class who complained about the operation of the

Decree. Indeed even after the entry of its October 13 Opinion

the district court on Motion of the Ford plaintiffs added John

Hicks, a named plaintiff in the Ford case, to the Implementation

Committee. This Committee is responsible for the effectuation

of the injunctive remedy.

10

amount of back pay due to class members. One year and

eight months after the mandate was issued the defendant

Steelworkers and United States Steel Corporation moved

for Summary Judgment (R34-51), maintaining that the

evidentiary hearing "envisioned" by the Fifth Circuit

was not "needed." (R53) On October 13, 1977, the district

court issued an opinion agreeing with the defendants; the

court found as a matter of law that it had erred in certifying

the class in 1973 because the Ford plaintiffs had no "nexus"

with the class. The district court also determined that

it was not bound by its prior judgment because of the Opinion

of this Court. (R53-62) The Ford plaintiffs moved to alter

or amend the judgment and alternatively, moved to intervene

or to substitute as named plaintiffs thirty-four members of

the class who had relied on the certification of the Ford

class (R64-5). On December 19, 1977, the district court

denied the motion to intervene, the motion to alter and

amend and the motion to substitute parties. (R69-82).

11

A R G U M E N T

Summary of Argument

I. The district court relied on the dictum in United

States v. Alleqheny-Ludlum Industries, 558 F.2d 742 (5th Cir.

1977) providing that the same standard for awarding attorneys'

fees applies to prevailing defendants and prevailing plaintiffs.

After the Supreme Court ruled to the contrary, Christianburg

Garment Co. v. EEOC, rehearing was granted in Allegheny-Ludlum

and the decision on the attorneys' fees standard was withdrawn.

Thus, the district court's award of attorneys' fees to the

defendants should be reversed.

II. When the district court certified the Ford class in

May 1973, the Ford plaintiffs and the class members had the

same interest with respect to injunctive relief; that interest

continues to this day. The only difference that existed in

May 1973 between the Ford plaintiffs and the Ford class with

respect to back pay relief was one of timing. The Ford plain

tiffs proceeded directly to a stage II hearing concerning the

calculation of monetary relief whereas the class members had

to await the conclusions of that hearing until they could appeal

and then proceed to the State II hearing. However, in May 1973

the Ford plaintiffs had not been awarded any monetary remedy

and it was unclear whether they would, after the stage II

determination, appeal with the class members concerning the

court's determination of back pay. The relevant time frame for

considering whether the class representatives had a proper

12

nexus" with the class members occurs when the class certifi

cation issue is presented or considered by the district court.

Satterwhite v. City of Greenville, 557 F.2d 414 (5th Cir. 1977).

The court considered the issue in May 1973 when there was a

proper nexus between the Ford plaintiffs and the class they

represent. Since the case continues to present a live contro

versy and the named plaintiffs adequately represent the class,

the court erred in decertifying the class. Moreover, the dis

trict court erred when it rendered its decision without holding

the hearing which had been mandated by this Court, United States

v. United States Steel Corporation, 520 F.2d 1043 (1975).

III. The district court contravened the law of the case

doctrine when it reversed its own 1973 certification of the

class and this Court's determination that the certification was

appropriate as a matter of law. Bolton v. Murray Envelope Corp.

553 F.2d 88 (5th Cir. 1977). This Court's decision in Ford I,

contrary to the analysis of the district court, affirmed that

"as a matter of Law" the Ford plaintiffs have standing to repre

sent the class and that the certification was proper. The law

of the case doctrine "grounded upon the sound public policy that

litigation must come to an end" requires the reversal of the

lower court's decision, Lehrman v. Gulf Oil Corporation, 500

F.2d 659 (5th Cir. 1974).

IV. If the ruling decertifying the class is not reversed,

then the ruling denying intervention must be reversed. The class

members were included in one or more of the class allegations of

13

the private actions and they relied on these private actions

to represent their interests in equal employment opportunity

throughout Fairfield Works. The "critical fact" determining

timely intervention is how soon after the entry of the Final

Judgment of an adverse class determination a class member seeks

to intervene, United Airlines v. McDonald, 432 U.S. 385 (1977).

The applicants timely filed twelve days after the entry of the

Final Judgment. Even if the district court's decision that the

intervention was untimely is not reversed under McDonald, it

should be reversed because the court improperly applies the

standards established by this Court for determining whether

intervention is timely sought. Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558

F.2d 257 (1977).

When measured by a "practical yardstick," the denial of

intervention impairs the ability of the would-be intervenors

to adequately protect their interest in the effective implemen

tation of the Decree and in the attainment of full monetary

relief. Thus, the district court erred in denying intervention

as of right pursuant to Rule 24(a) (2). Since the district

court applied the same erroneous analysis in exercising its

discretion to grant permissive intervention pursuant to Rule

24(b) as it did in determining whether intervention was timely

sought, the court's ruling denying permissive intervention

should be reversed.

14

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN AWARDING ATTORNEYS' FEES TO

THE DEFENDANTS

There are two separate rulings concerning attorneys' fees.

In its October 13 opinion decertifying the class, the court

held that the plaintiffs had prevailed on the appeal and were

thus entitled to attorneys' fees since they "succeeded in re

versing a ruling denying back pay, which would have been bind

ing upon the 'new' Ford class." (R.62) Although the defendants

prevailed in the post-appeal proceedings the court declined to

award attorneys' fees to them because of the "unusual context

of this case — the plaintiffs and their counsel having involun

tarily been appointed by the court as class representatives . ."

(R.62) However, in its decision of December 19, 1977, the court

stated that the motions for reconsideration and intervention

filed by the plaintiffs were not done "under the terms of an

involuntary appointment from the court" and that since the de

fendants prevailed on these matters they should be entitled to

attorney fees. (R.81-2)

In its decision to grant attorneys' fees to the defendants

the district court followed the dictum in United States v.

Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, 558 F.2d 742 (5th Cir. 1977) that

there should be no "double standard" in awarding fees to pre

vailing parties depending on whether they are plaintiffs or

defendants. But following this opinion the Supreme Court ruled

15

to the contrary:

In sum, a district court may in its

discretion award attorneys ' fees to

a prevailing defendant in a Title VII

case upon a finding that the plaintiff's

action was frivolous, unreasonable or

without foundation, even though not

brought in subjective bad faith.

Christianburg Garment Co. v. Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission,

98 S.Ct. 694, 700 (1978)

After the decision in Christianburg Garment Co., this

Court granted rehearing in Allegheny-Ludlum and withdrew that

portion of the opinion relating to the standard to be applied

in awarding attorneys' fees to prevailing defendants, 568 F.2d

1073 (1978). Since the district court relied on the incorrect

legal standard established in Allegheny-Ludlum the decision

17/

awarding attorneys' fees to the defendants should be reversed.

2 / This court has vacated and remanded other cases for a

determination as to the appropriateness of an award of attorneys'

fees to prevailing defendants in light of Christianburg Garment

Co., Lopez v. Arkansas County Independent School District, 570

F .2d 541, 545 (1978); EEOC v. Datapoint Corp.,___ F.2d ___ ,

(No.76-2862, April 7, 1978).

However, in this case it is so clear that the plaintiffs'

Motion to Amend and Motion to Intervene were reasonable and

brought with a substaitial legal foundation the Court should

simply reverse the decision of the district court to award

attorney fees to the defendants. Of course, if the court

reverses the lower court on the merits as presented in Argu

ments II—IV, then the issue of the award of fees to the de

fendants is moot since they no longer would be a prevailing

party.

16

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED WHEN IT DECERTIFIED THE CLASS

ON THE BASIS THAT THE FORD PLAINTIFFS DID NOT HAVE

THE NECESSARY "NEXUS" WITH THE CLASS MEMBERS

In the summer of 1968, this court in the initial opinions

rendered by an appellate court concerning Title V U class actions

stated several principles that have guided the subsequent

development of fair employment law. First, Title VII suits

while they may be private in form have an important public

interest, the enforcement of equal employment laws. Second,

while conciliation is an important method for resolving dis

crimination complaints, private litigation is a necessary spur

to cause companies and unions to comply with the Act. Third,

race discrimination cases are by their very nature class actions.

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corporation, 398 F.2d 496 (5th Cir.

1968); Jenkins v. United Gas Corporation, 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir.

1968); see also Huff v. N.D. Cass Co., 485 F.2d 710 (5th Cir.

1973) (en banc). Other circuit courts and then the Supreme Court

approved these general principles, Albemarle Paper Company v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 414 N.8 and 421-22 (1975); United Airlines,

Inc, v. McDonald. 432 U.S. 385, 393 N.13 (1977).

As recognized in Oatis, the named plaintiff must still, of

course, meet the requirements of Rule 23 and have standing to

present the issues, 398 F.2d at 499. "We are not unaware that

suits alleging racial or ethnic discrimination are often by

their very nature class suits, involving classwide wrongs. But

17

careful attention to the requirements of Fed. Rule Civ. Proc.

23 remains nonetheless indispensable." East Texas Motor Freight

v. Rodriquez, 431 U.S. 395, 405 (1977).

The six-month trial of this case in 1972 demonstrated the

appropriateness of the general principles established four

years earlier by this Court. The termination of discrimination

by litigation at the massive Fairfield Works implemented the

public policy of fair employment and acted as a "spur" to

improving equal employment opportunity throughout the steel

industry, see United States v . Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, 517

F.2d 826, cert. denied 96 S.Ct. 1684 (1976). Moreover, the

broad practices of race discrimination, primarily initial job

assignment and the seniority system, were remedied by class

relief, 5 EPD para. 8619. Under these circumstances the district

court determined that the pending private actions were appropriate

class actions. The court heeding the guidance of Oatis and

anticipating the direction of Rodriguez specifically held that

"the prerequisities of Federal Rule 23(a) are satisfied and that

in addition the provisions of Rule 23(b)(2) are applicable."

But four and one-half years later the district court reversed

its position holding that the "prerequisites" of Rule 23(a) were

not in fact met.

The district court reversed its prior decision on the

18

basis that the Ford named plaintiffs had never had the

"necessary 'nexus'" with the class to satisfy "commonality"

and "typically" requirements of Rule 23(a)(2) and (3).

(R.57-59). There is no question that the numerosity require

ment, Rule 23(a)(1) (R.72) and the adequacy of representation

requirement were satisfied, Rule 23(a)(4) (R.57), see also

United States v. United States Steel Corporation, 520 F.2d at

1051.

Judge Pointer after stating that the Ford plaintiffs "are

not now — nor have they ever been — members of the 'new' Ford

class" concludes that they do not have a sufficient "nexus under

Rodriquez" to represent the class. This statement was in error.

The relevant time-frame for determining whether the necessary

"nexus" exists between the claims of the named plaintiffs and

the class is not after the final determination of the merits,

but, depending on the circumstances of the case, when the class

allegations are presented, when the motion to certify is made,

or when the disctrict court determines that a class certifica

tion is or is not appropriate. Satterwhite v. City of Greenville

557 F.2d 414, 419-22 (5th Cir . 1977); Franks v. Bowman Trans

portation Company, 424 U.S. 747, 754-56 (1976). Once the ques

tion of class certification was before the district court, as

it was here in May, 1973, the question as to whether the case

19

is an appropriate class action at a later time does not turn

on the merits of the named plaintiffs' claims, nor on their

mootness, nor even on their present "nexus" with the claims

of the class. Rather the issue shifts from "whether the named

plaintiff in a class action maintains the requisite 'personal

stake in the outcome' to whether after the named plaintiff's

claim no longer exists, the class has acquired such a personal

stake", (footnote omitted) Satterwhite v. City of Greenville,

supra at 416. The inquiry should concern whether it was appro

priate to have certified the class, whether a live controversy

continues in which the class maintains sufficient interest,

and whether the named plaintiffs still adequately represent the

interest of the plaintiffs, id. at 423.

There is no question that the interest of the several

hundred class members in obtaining back pay and in insuring

the effective implementation of the Decree presents a live con

troversy. The district court found that there is presently

adequate representation: "There is no conflict of interest

between Ford and the black employees in other departments and

plants of the company, and Ford's counsel are among the country's

finest and most dedicated attorneys in this type of litigation".

(R.57) The focus of the question is accordingly narrow — did

the Ford plaintiffs in May, 1973 have a sufficient "nexus" with

20

the class to properly satisfy the requirements of Rule 23 when

the issue or class certification was before the district court.

The simple fact of the matter is that at the time of the

certification of the Ford class in May, 1973 the Ford plaintiffs

were similarly situated to the class members and as such were

part of the class: there were questions of law and fact common

to the named plaintiffs and the class and the claims of the

named plaintiffs were the same as those of the class. The dis

trict court's statement that the certification took place “after

trial of the case, the entire litigation having been tried . . "

is inaccurate. As this Court observed the trial in 1972 was

only the first stage of the trial of the case, 520 F.Ed at 1049-51.

18/In its May Decree the district court held that the defendants

had violated Title VII and ordered an injunctive remedy that

applied evenly to all the Ford class members, 5 EPD para. 8619.

Moreover, the court ordered back pay to be paid to the crane

hookers, in the Plate Mill of Fairfield Steel Plant, McKinstry

case, the black workers in Stock House of Ensley Steel, Hardy

case, and the black workers in the Car Shop of Rail Transporta

tion, Ford case, "who have been damaged by the discriminatory

lines of promotion," id. The court stated that "further hearings

18 / The United States Steel Corporation, United Steelworkers

of America and the Locals of the United Steelworkers.

21

and proceedings" would be held to determine who would receive

back pay and in what amount, 5 EPD para 8619 at 7822-23.

It is of critical importance that except for the back

pay hearings to be held in the future the Ford plaintiffs and

the class of black employees throughout Fairfield Works were

as of the May Decree in the same position with respect to both

back pay and injunctive relief. The May Decree did not award

any back pay to the named Ford plaintiffs. Only after the

termination of the second stage trial, and the decision of the

district court, would the Ford plaintiffs know _if they were

going to be awarded back pay and if so, in what amount.

It was entirely possible that one, two or even all of the

Ford plaintiffs would be denied back pay or would be awarded

an amount less than that which would satisfy their claims. On

August 10, 1973, the district court rendered a final decision

awarding back pay to 33 of the 37 black workers in the Car Shop,

see supra at 9. The six named plaintiffs were coincidentally

among the thirty-three black workers who received back pay; in

May 1973, it was, of course, not clear that the 37 black workers

in the Ford class would find, as they did on August 10, that an

appeal was unwarranted after Final Judgment on their claims for

back pay.

As of the May 3 Decree the Ford plaintiffs like the class

22

members simply had claims for back pay; these claims presented

similar fact questions concerning the determination of the

amount of earnings lost as a result of discriminatory practices

and similar legal questions concerning whether "future" loss

could be compensated, the legal effect of past job waivers and

other questions which this Court discussed in its decision on

the appeal, 520 F.2d at 1054-58. The only difference between

the Ford plaintiffs and the class was one of timing: when these

similar law and fact questions would be presented for decision to

the district court.

As a result of the May Stage I decision the Ford plaintiffs

proceeded to a Stage II trial adjudicating their back pay

claims. However, the class members were required to await the

conclusion of the Stage II trial (since the May Decree was

interlocutory) to appeal the decision of the district court,

and then, if successful on appeal (as they were), to proceed

to Stage II. Importantly, if the district court ruled against

the named Ford plaintiffs in Stage II, they would have joined

the class members on the appeal and then on remand be joined

with the class members in presenting their claims for back pay.

With respect to injunctive relief, the claims and circum

stances of the class members and the named plaintiffs were

identical in timing as well as substance. The extensive

23

injunctive relief entered in May, 1973 applied evenly to the

19/

Ford plaintiffs and the class members. Moreover, the Ford

plaintiffs represented the class of black workers in Fairfield

Works in the implementation of the Decree. For example, the

Ford plaintiffs represented the black workers in the selection20/

of the black worker members of the Implementation Committee, assist

ed black workers in understanding the Decree, in processing com

plaints concerning the effectuation of the Decree and in mon-

21/

itoring the workings of the Decree. Furthermore, the Ford

19/ The Decree provided the following remedy which was applied

to all of Fairfield Works: General injunction (paragraph 1),

Implementation Committee which contained a representative for all

the black workers at Fairfield Works (paragraph 2), seniority

remedy providing for the use of plant seniority within all the

plants (paragraph 4), right to transfer to salaried positions

for workers in all the plants (paragraph 5), training oppor

tunities for workers in all the plants (paragraph 6), affirm

ative action in the form of goals and timetables available to

workers in all of the plants (paragraph 7), red-circling avail

able in all the plants (paragraph 8) and reporting and record

keeping provisions which covered all the plants (paragraphs 9

and 10), 5 EPD para. 8619.

20/ The Implementation Committee is described at 5 EPD para.

8619 at 7815-16. The original black worker on the Committee,

Thomas Johnson, has recently been replaced by one of the named

Ford plaintiffs, John Hicks.

21/ a copy of all the reports required by the May Decree is

sent to counsel for plaintiffs. Counsel for the named plain

tiffs have on numerous occasions represented members of the

class in informal discussions and negotiations with the defend

ants concerning the implementation of the Decree.

24

plaintiffs represented the class of black workers in insuring

the appropriate modification of the Decree when the district

court held a hearing concerning the application of the steel

22/

consent decrees, see supra at 9— 10, at Fairfield Works.

In conclusion, the interests and claims of the Ford plain

tiffs and the class members as of the May 3 certification of

the class were similar. Neither the plaintiffs nor the class mem

bers had received the back pay which they claimed; the plain

tiffs and the class members both sought full and effective

implementation of the injunctive decree.

The district court not only erroneously applied the law

in determining that the Ford plaintiffs no longer could pro

perly represent the class but also failed to follow the specific

mandate of this Court that "the district court should conduct a

hearing and take evidence as to the propriety of the 'new'

Ford class . . . ," (R. 53) The failure of the district court

to hold a hearing on the matters specifically directed for

23/

determination by this Court requires reversal.

22/ When the defendants sought to modify the May Decree to

conform to the nationwide steel industry decree counsel for

plaintiffs represented the interest of the class members by

opposing several of the modifications. The plaintiffs were

successful in their opposition to certain of the defendants’

modifications concerning the affirmative action program, the

Implementation Committee and other matters.

23/ The several factual issues which this Court stated to be

appropriate for resolution after a hearing are described in

Section III, infra.

25

Additionally, it is important to note that the failure to

hold a hearing inevitably led the district court to fail to

properly consider the facts of the case. For example, the

district court states that "Most black employees at the various

plants at Fairfield Works were not class members in any of the

actions." (R.SS) This is not the case. The complaints filed

in the private actions purported to include all of the black

workers at Fairfield works. Even if the class complaints are

read narrowly (and plaintiffs would maintain improperly) these

complaints would include well over 50% of the black workers

at Fairfield Works, supra at 3. Moreover, the plaintiffs,

if the court had held a hearing, would have been able to show

that black workers throughout Fairfield Works had relied on

these private suits from the mid 1960's to the present to re

present their interests in achieving equal employment opportunity.

The black employees at Fairfield works had formed the Ad Hoc

Group in the early 19601s in order to work together to achieve

equal employment opportunity. At the meetings of the Ad Hoc Group

held during the 1960's the private litigation was discussed,

and the purpose of that litigation to end discrimination through

out Fairfield Works was emphasized.

Furthermore, the Ford plaintiffs at the hearing could have

demonstrated that they continue to have an interest in the

litigation because (1) they depend on the effective implementa

tions of the Decree, just as the class members do, to insure

26

their equal employment opportunity; and (2) they are active

participants in the Ad Hoc Group, where they have been active

since its formation, and they are concerned with the achieve

ment of the goal of the Ad Hoc Group — the final end of dis

crimination at Fairfield Works and a fair remedy for those who

have suffered from that discrimination. The concern of the

Ford plaintiffs that the Decree effectively terminates discri

mination is amply shown by the recent appointment of John Hicks,

a Ford named plaintiff, to the Implementation Committee estab

lished under the May 1973 Decree.

27

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED WHEN IT FAILED TO FOLLOW THE

ESTABLISHED LAW OF THE CASE AND DECERTIFIED THE CLASS

The application of the "law of the case" doctrine usually

involves a situation where a lower court is reversed on appeal

but then on remand questions whether a particular issue was

actually decided by the appellate court. Here the circumstances

for the application of the law of the case doctrine is much

stronger: both the district court and this Court in Ford I held

that "as a matter of law" Ford does not lack standing to represent

the class, 520 F.2d at 1052. Nevertheless, the district court

ruled, as a matter of law, that the Ford plaintiffs' lacked standing

to represent the class since they did not have the "necessary"

nexus with the class members. Since the lower court ruled as a

matter of law it felt free to disregard this Court's mandate

that "on remand the district court should conduct a hearing and

take evidence as to the propriety of the 'new' Ford class. . . . "

52 O.F.2d at 1051. The district court erred in reversing its

prior decidion on class certification which was affirmed as being

legally proper by this Court and by thus failing to follow the

"laudable" law of the case doctrine. Lehrman v. Gulf Oil

Corporation, 500 F.2d 659, 662 (5th Cir. 1974); Bolton v. Murray

Envelope Corp., 553 F.2d 88 (5th Cir. 1977).

This Court has repeatedly stressed the importance of the

doctrince since it

28

is grounded upon the sound public policy

that litigation must come to an end. An

appellate court cannot efficiently perform

its duty to provide expeditious justice to

all "if a question, once considered and

decided by it were to be litigated anew in

the same case upon any and every subsequent

appeal." (Footnote omitted)

Lehrman v. Gulf Oil Corporation, supra at 662; Terrell v. House

hold Goods Carriers' Bureau, 494 F.2d 16, 19 (5th Cir. 1974);

24/Zarqaur v. United States, 493 F.2d 447, 453-54 (5th Cir. 1974);

White v. Murtha, 377 F.2d 428, 431 (5th Cir. 1967). Accordingly,

this Court has held that "as a general rule if the issues were

decided, either expressly or by necessary implication, those

determinations of law will be binding on remand and on a subse

quent appeal" (footnote omitted) Lehrman v. Gulf Oil Corporation,

supra at 663. While the law of the case doctrine is somewhat

2y

more limited than the doctrine of res judicata, those limitations

do not apply in this case. Rather the district court sought to

avoid the binding effect of the prior decisions in this case

through an interpretation of this Court's decision in Ford I.

The lower court erred in its interpretation.

24/ »it is a principle not to be taken lightly for to do so would

not only encourage judicial inefficiency but also 'panel shopping'

at the appellate level."

25/ The law of the case doctrine does not apply as does res judicata

to questions which were present in the case but which were not

decided. Moreover, the law of the case doctrine will not prevent

a second review of a question if "considerations of substantial

justice warrant it." Id.

29

The district court implicitly recognized that if the

decision of this Court in Ford I did not "relieve" it "from

being bound by its certification of that class" than the law

of the case doctrine and this Court's decision in Bolton v.

Murray Envelope Corp., supra, would preclude a reversal of the

certification decision. (R. 56) The district court only cited

several lines out-of-context from Ford I in support of the

decision that it was relieved of the binding effect of its

prior decision. (R. 56) However, when these remarks are read

in context it is clear that Ford I affirms both the

legal standing of the Ford plaintiffs to represent the class and

the legal appropriateness of the certification of that class after

the Stage 1 trial on liability.

In Ford I the Court summarized its conclusions in the

beginning of the Cpinion,

On remand the district court should carefully

redetermine the propriety of the amorphous

'new' Ford class in light of the consequences

of binding such a_ group to a final judgment.

520 F .2d at 1048. (Emphasis added.)

The Court was concerned with the scope of the Ford class, the

manageability of the case, and whether, in fact, the Ford

plaintiffs could be adequate representatives. The Court was

further concerned that the lower court use the "flexibility"

contained in Rule 23 to insure effective and efficient resolu

tion of the back pay issue. Specifically, the Court pointed

30

out that the district court confronted on remand two separate

problems concerning the speculative nature of the back pay

award: Whether the economic disparity between black and white

workers was the reasonably certain result of the unlawful

conduct and then, if so, to what extent part of the economic

disparity may be attributed to causes other than unlawful

discrimination, 520 F.2d at 1048. The Court then stated that

We believe that both of these difficulties

[concerning the calculation of back pay] can

be largely obviated on remand by the funda

mental expedient of reexamining the scope of

the "new" Ford class. Id.

The Court recognized that the district court had

not in May 1973 made the factual analysis required to determine

specifically how the Ford class action should be managed for

back pay proceedings because the district court had denied back

pay to that class. The Court directed the lower court to make

that analysis:

On remand the district court should conduct

a hearing and take evidence as to the pro

priety of the "new" Ford class, its scope

in terms of the ingredients of the judgment,

if any, by which it ought to be bound, and

its size and membership.

* * * *

The question on remand will be comprehensive

and multifacited: the extent to which the

"new" Ford class is maintainable in a "meaning

ful and manageable" sense as a class action

seeking monetary relief. . . . As a corollary

matter, the court should consider the adequacy

of the representation, F.R. Civ. P. 23(a)(4),

which in this court has been impressive.

(emphasis added), Id. at 1051.

31

The Court clearly was focusing the remand proceedings on

factual concerns of "manageability", "adequate representation",

creation of "sub-classes", etc. However, these were fact

questions, to which, of course, applicable law would be applied.

They were not questions concerning whether the Ford plaintiffs,

as a matter of law and regardless of any further factual findings could

represent the class. These legal questions were raised by the

United States Steel Corporation on appeal and by petition for

26/

certiorari. These questions were settled in Ford I:

Initially, we reject appellee United States

Steel's argument that appellant Ford lacks

standing as a matter of law to represent any

class of black employees broader than the

"original" Ford class. . . . Nor do we accept

the argument that the designation of a "new"

Ford class constituted inherent error or an

unauthorized substitution of parties. Id. at

1052

Thus, the legal issues concerning the Ford plaintiffs’

standing or their appropriateness as Rule 23 class representatives

were settled in Ford I; the district court was instructed after

a hearing to review the structure, manageability, and even the

scope" of the Ford plaintiffs’ standing but not to review once again

the decision of this Court as well as its own decision ccnceming the basic

^2/ United States Steel Corporation's petition for certiorari

raised questions concerning the standing and adequacy of the

Ford plaintiffs to represent the class. The petition for

certiorari was denied, 96 S. Ct. 1684 (1976).

32

legality of the certification of the Ford class. Therefore,

the district court's decertification of the class runs afoul

of the law of the case doctrine, see Bolton v. Murray Envelope

Corp., supra/ and should be reversed.

33

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED WHEN IT DENIED INTERVENTION

The applicants for intervention are thirty-four

black workers who have worked or are working in every one

22/of the nine plants at Fairfield Works except the Ore

28/

Conditioning and Rail Transportation plants. Further

more, the applicant group includes former employees who are

presently retired and who were not in the group of employees

who received consent decree tenders, see supra at 9-10,as

well as employees who refused the consent decree tender.

However, all of these emoloyees had previously been in

cluded in the Ford class and had been relying on the case

to present their back pay claims and interest in the

2 9/

effective implementation of the Decree.

Within two weeks of the district court's decertifi

cation of the class action the intervenors filed the motion

27/ Appendix D lists the intervenors by plant.

28/ The Ore Conditioning plant contains only a handful

of black workers, see Appendix C. The Ford plaintiffs are

employed within the Rail Transportation plant.

29/ In the alternative the intervenors moved for a

substitution of parties. The district court held that "the

intervenors' efforts must be tested under the principles

applicable to intervention, rather than those applicable to

amendments". (R. 72 n.l) While appellants rely primarily

on intervention, they maintain that the interest in back pay

was transferred from the named plaintiffs to them and that

they properly may be substituted as parties pursuant to Rule

25(c), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Cf. Walker v .

Providence Journal Company, 493 F.2d 82, 86-7 (1st Cir.

1974).

34

to intervene and complaint in intervention. (R. 64-5)

The district court determined that according to the standards

established by Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558 F .2d 257

(5th Cir. 1977) the intervention filed October 25, 1977, in

a case which commenced October 7, 1966, was untimely. (R.

73-79) Additionally, the district court stated that even

if the intervention has been timely sought it would have

denied the intervention within its discretion under Rule

30/24(b) because it would "have prejudiced the adjudica

tion of the rights of the original defendants". (R. 80)

The district court erred on both accounts.

A. Timeliness

The district court erred in ruling that the interven

tion was untimely in two respects: the relevant date for

determining whether the intervention was timely was October

13, 1977, when the class was decertified, not the October 5,

1966 filing date relied on by the district court, United

Airlines, Inc, v. McDonald, 432 U.S. 385 (1977); the district

court improperly applied the Stallworth v. Monsanto Co.

standards.

The Supreme Court in McDonald held that the "critical

fact" determining whether a class member timely intervenes

is how soon that intervention is sought from the entry

30/ The district court determined that the invervention

did not meet the standards of intervention by right, Rule

24(a)(2), (R. 79)

35

of a final judgment of an adverse class determination when

it is clear that the named plaintiffs will or cannot con

tinue to represent the interests of the unnamed class mem

bers, 432 U.S. at 394, 396. In McDonald the intervenors

sought to intervene eighteen days after the entry of final

judgment against the named plaintiffs but over five years

after the district court had denied class certification.

The Supreme Court held that intervention was timely sought

pursuant to Rule 24(b).

Judge Pointer noted the application of McDonald but

misapplied the decision to this case. The court stated

that the period from May 2, 1973 to October 13 could "not

be counted against the would-be intervenors" because during

that period they belonged to the certified class. (R.

73-4) But the court asked "what about the time prior to

May 2, 1973". The court stated that although it is not

possible "to fix precise dates" when the intervenors

knew that they were not being represented by the Ford case

the period must be "measured in years". Of primary impor

tance the court states that "the period of inaction [cannot]

be excused on the basis that intervenors were expecting the

Ford plaintiffs to press their cause, when ripe, on an

appeal, for the Ford plaintiff had never sought to repre

sent employees in other plants". (R. 74)

It is true that the Ford plaintiffs never sought to

represent emloyees in other plants prior to May 1973 but

the court dismisses the fact that the plaintiffs in the

36

McKinstry, Hardy, and the other private actions did

purport to represent blacks throughout Fairfield Works,

see supra at 3-5. The broad classes set forth in the

complaints in these private actions had been limited by

prior court determination, see supra at 4. However,

the class members in these cases like the class members in

McDonald, where the district court had refused to certify

the class, had no reason to believe that the named plain

tiffs would not appeal the court's ruling limiting the

scope of the class certification. It serves no purpose to

require putative class members who seek to appeal an

interlocutory order denying class certifica.tion to move to

intervene shortly after that order is entered because the

intervenors would be "superfluous spectators" until after

final judgment when the order is appealable. United

Airlines, Inc, v. McDonald supra at 394 n.15. Nor are the

defendants, United States Steel Corporation or United

Steelworkers, unfairly surprised or prejudiced by this

intervention since the complaints in the private actions

put them on notice of the possibility of broad classwide

liability, United Airlines, Inc, v . McDonald, supra at

394-95. Here, unlike McDonald, the government filed a

broad "pattern and practice" suit in 1970 and the Stage I

liability trial was, for all practical purposes, identical

to the trial which would have been held if the private actions

had not been restricted to narrowly defined classes.

A fortiori, the defendant Company and Union cannot claim

surprise or prejudice.

- 37 -

There is no reason to distinguish this case from

McDonald, as the district court did, on the grounds that

the intervenors were never included in the class sought to

be represented by the Ford case but rather were included in

the class sought to be represented by plaintiffs in cases

which were consolidated with the Ford case. The logic of

the district court's argument would have required interven

tion by the unnamed class members in each and every one of

the six private class actions at the time the opinions

limiting the class actions were rendered since the named

plaintiffs in any of the class actions may have been found

later to be appropriate class representatives. In this

case no less than in McDonald the unnamed class members may

fairly have relied on pending litigation to present their

interests. To require cross-intervention as suggested by

the disctrict court would result in the "very multiplicity

of activity which Rule 23 was designed to avoid" and which

McDonald declared was unnecessary, 432 U.S. at 394 n.15;

Philadelphia Elec. Co. v. Anacanda American Brass Co. 43 F.R.P.

452, 461 (E.D. Pa. 1968).

The district court's erroneous application of McDonald

requires reversal of the conclusion that the intervention

was untimely. Assuming that the decision is not reversed

on this ground, it must be reversed because the lower court

misapplied the standards for determining timeliness set

forth in Stallworth v. Monsanto Co. In Stallworth the

court noted prior law providing that "timeliness is

38

not a word of exactitude" and that timeliness must "be

determined from all the circumstances". Nevertheless, the

Court distilled four factors to be considered in determin

ing whether the motion to intervene is timely brought, id.

at 264-66.

Factor 1. The length of time during which the

would-be intervenor actually knew or reasonably

should have known of his interest in the case

before he petitioned for leave to intervene.

Factor 2. The extent of the prejudice that

the existing parties to the litigation may

suffer as a result of the would-be intervenor's

failure to apply for intervention as soon as

he actually knew or reasonably should have

known of his interest in the case.

Factor 3. The extent of the prejudice that

the would-be intervenor may suffer if his

petition for leave to intervene is denied.

Factor 4. The existence of unusual circum

stances militating either for or against a

determination that the application is untimely.

In determining that the intervention was untimely

the district court relied on factors 1, 3, and 4. The

court's reliance on factors 1 and 3 in determining that

the intervention was untimely was erroneous as a matter of

law; in addition the court failed under factor 4 to take

into account "unusual circumstances" in this case which

would have militated in favor of a determination of

31/timeliness.

3 1/ in its analysis of factor 2, the district court

determined that the defendants did not suffer prejudice as

a result of intervenors' failure to apply for intervention

as soon as they knew of their interest in the case even

39

The district court's analysis of factor 1 is in

error for the same reason that the court misapplied McDonald.

The time at which the intervenors "should have been aware

that [their] interest[s]...were not being adequately

represented" was not as the court rules in 1966 (R. 73-4)

when the Ford action was filed, nor 1967 when the scope of

the private actions was limited, but rather October 13,

1977 when the Ford action was decertified and final judg

ment was entered. Until that time the intervenors were

included in the classes which the private named plaintiffs

sought to represent or were included in the 1973 certifica

tion of the Ford class.

In McDonald, the Supreme Court specifically approved

a line of decisions of the federal courts where, as here,

post-judgment intervention is sought for purpose of

appeal, 432 U.S. at 395-6 n.16. "The critical inquiry in

every such case is whether in view of all the circumstances

the intervenor acted promptly after the entry of the final

judgment", id. at 395-6. There is no question that the

intervenors Wright, et al., in filing their motion twelve

̂V Cont'd

though the district court wrongfully held that the date the

intervenors knew or should have known of their interest in

the case requiring intervention was 1966. (R. 75-7)

Rather as explained supra at 35-6, the date by which the

timeliness of the intervention should be evaluated is

October 13, 1977, the day the class was decertified and

final judgment was entered.

40

days after the entry of final judgment, expeditiously moved

to intervene.

In applying factor 3, the court concludes that

"strange as it may seem, any prejudice to the would-be

intervenors by denial of intervention in the Ford case is

minimal". (R. 76) The district court acknowledges that it

might be argued that the denial of intervention would

deny the intervenors the benefit of the "tolling" of the

d A ̂

applicable limitations period (a very important benefit);

the argument that tolling applies only to intervention

cases and not to new litigation would be based on the fact

that, as Judge Pointer states, "the key Supreme Court

decisions recognizing such a tolling were cases involving

intervention". However, Judge Pointer dismisses the

argument:

The rationale, however, for the American

Pipe [& Construction Co. v. Utah], 414

U.S. 538 (1974)] decision, as well as the

language in the opinion, makes it clear

32/ This denial would adversely affect the intervenors

whether the "tolling" would apply only to the period during

the certification of the Ford class as Judge Pointer

indicates or to the entire period from the filing

of private class action suits, (see R. 78 n.2). Actually,

the tolling of the statute of limitations in Title VII

commences from the filing of the EEOC charges. Romasanta

v. United Airlines, 537 F.2d 915, 918 n.6 (7th Cir. 1976)

aff1d as United Airlines v. McDonald, 432 U.S. 385 (1977).

Whether the tolling commences at the time of the filing of

the EEOC charge or the private actions makes little dif

ference here because the Hardy, McKinstry and Ford actions

were all filed in 1966.

41

that tolling, where appropriate, would

also be allowed with respect to newly

instituted litigation. Whatever tolling

benefits the would-be intervenors could

obtain on intervention, they could, this

court is convinced, also obtain in new

litigation. (R. 78)

The district court did not rely on any authority to

support its

directly on

While Judge

as clear as

commentator

conviction. Nor could any authority bearing

the issue one way or the other be found.

Pointer may be right, the issue is not

his opinion states. For example, a prestigious

has stated that the answer is "obscure" and

that, ...there is much in the Court's opinion

[American Pipe] that suggest that interven

tion under Rule 24 is the only recourse for

the class member against whose claim the

statute has run during the pendency of class

action. 3B J. Moore, Federal Practice, 1977-78

Supplement at 178.

Accordingly, it is possible that, contrary to the district

court's facile conclusion, intervention may, due to the

tolling of the applicable limitations periods, result in a

substantially greater recovery of back pay than new litiga

tion .

Furthermore, the district court acknowledges that the

would-be intervenors may be harmed by denial of the interven

tion becaue they might not be able to take advantage of the

EEOC charges filed by the named plaintiffs. (R. 77) Again

this is not a simple question to answer. If tolling is per

mitted in new litigation, then the plaintiffs in that litiga

tion may receive the benefit of the EEOC charges filed by

42

the named plaintiffs in the Ford and the other private

actions. However, this is certainly not clearly establish

ed law; whereas it is established law that intervenors,

although they have not filed charges, may rely on the EEOC

charges filed by the original plaintiffs. Wheeler v.

American Home Products, 563 F .2d 1233 (5th Cir. 1977).

The district court dismisses this potential

ly serious harm to the intervenors by concluding that, in

any case, the charge filed by the Ford plaintiffs is not

sufficiently broad to include the claims of the intervenors.

(R. 77-8) This is a particularly problematic conclusion.

The district court had found in 1973 that the Ford plain

tiffs could represent the claims of the intervenors. This

Court on appeal stated that "as a matter of law" the Ford

plaintiffs could represent the intervenors and the Supreme

Court denied the defendants' petition for certiorari. It

would appear too late in the litigation of this case for the

district court to determine that the EEOC charges are after

all too narrow to permit the claims of the intervenors to be

presented, see Argument III.

33/ The intervenors maintain that it is appropriate to

look not only at the EEOC charges filed by the Ford plain