Correspondence from Still to Cox, Stein, and Jones Re: Amicus Brief

Correspondence

October 6, 1998

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Correspondence from Still to Cox, Stein, and Jones Re: Amicus Brief, 1998. 1e920c96-db0e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d8aea4db-7549-49f0-b879-3b2a068523a1/correspondence-from-still-to-cox-stein-and-jones-re-amicus-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

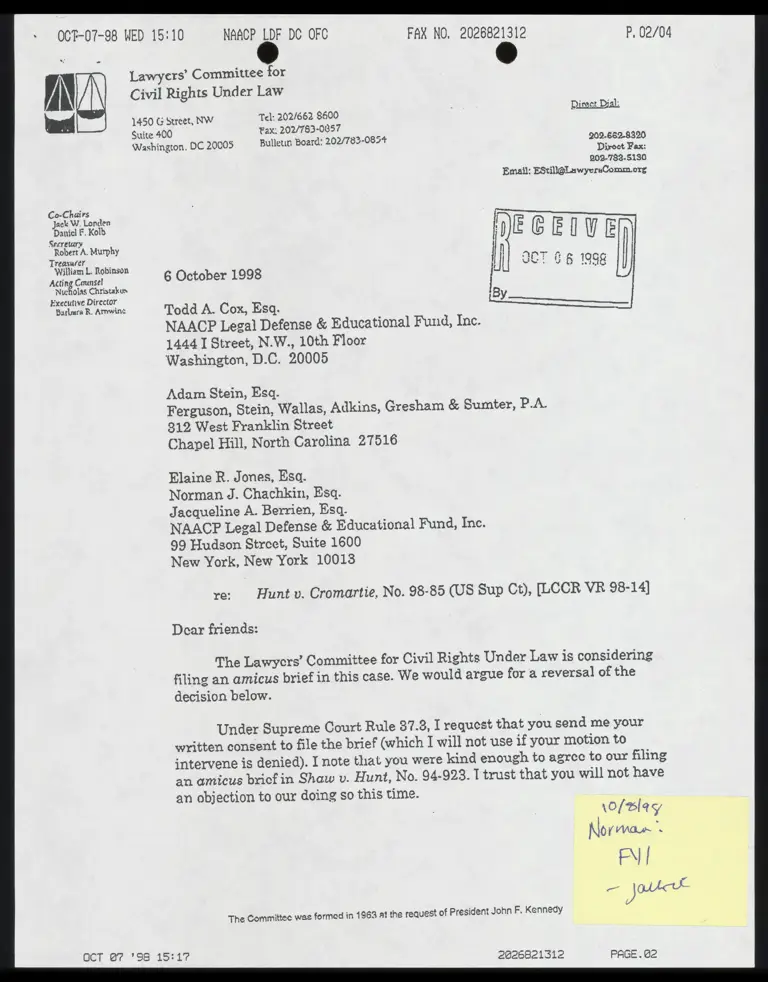

OCT-07-98 WED 15:10 NAACP LDF DC OFC FAX NO. 2026821312 P. 02/04

. Lawyers’ Committee for

IN/\ Civil Rights Under Law

| hd 1450 (3 Street, NW Tel: 202/662 8600 gf: Direct Dial:

Suite 400 Fax: 202/783-0857

Washington. DC 20005 Bullen Board: 202/782-0854

202.682.8320

Direct Fax:

202-782-5130

Email: EStill@LawyersComm

. org

Co-Chairs

Jack W. Londen

Bade Lik

Robert A. Murphy

Treasurer

i Te 6 October 1998

Nicholas Christakos

at Todd A. Cox, Esq. a

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

1444 I Street, N.W., 10th Floor

Washington, D.C. 20005

Adam Stein, Esq.

Ferguson, Stein, Wallas, Adkins, Gresham & Sumter, P.A.

312 West Franklin Street

hapel Hill, North Carolina 27516

Elaine R. Jones, Esa.

Norman J. Chachkin, Esq.

Jacqueline A. Berrien, Esa.

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

re: Hunt v. Cromartie, No. 98-85 (US Sup Ct), [LCCR VR 98-14]

Dear friends:

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law 1s considering

filing an amicus brief in this case. We would argue for a reversal of the

decision below.

Under Supreme Court Rule 37.3, I request that you send me your

written consent to file the brief (which I will not use if your motion to

intervene is denied). I note that you were kind enough to agree to our filing

an amicus brief in Shaw v. Hunt, No. 04-923. T trust that you will not have

an objection to our doing so this time.

\o/Blay

Nor ma .

=

— Jokes

The Committee was formed in 1863 a1 the request of President John F. Kennedy

OCT @7 '93 15:17 2826821312 PAGE. G2

OCT-07-98 WED 15:10 NAACP LDF DC OFC FAX NO. 2026821312 P. 03/04

Sincerely,

ek

Edward Still

es/+

cc:

Robinson O. Everett , Esq.

P.O. Box 586

Durham, NC 27702

Martin B. McGee ; Esq.

Williams, Boger, Grady, Davis & Tuttle

P.O. Box 810

Concord, NC 28026-0810

Edwin M. Speas, Jr., Esq.

Tiare Bowe Smiley, Esq.

North Carolina Dept. of Justice

PO Box 629

Raleigh, NC 27602-0629

OCT @7 ’S3 15:17 2826821312 PAGE. B3

0CF-07-98 WED 15:10 NAACP LDF DC OFC FAX NO. 2026821312 P. 04/04

bec:

David Stein, Esq.

Steptoe & Johnson

1330 Connecticut Ave NW

Washington, DC 20036-1795

OCT @7.798 15:17 2026821312 PAGE. B4