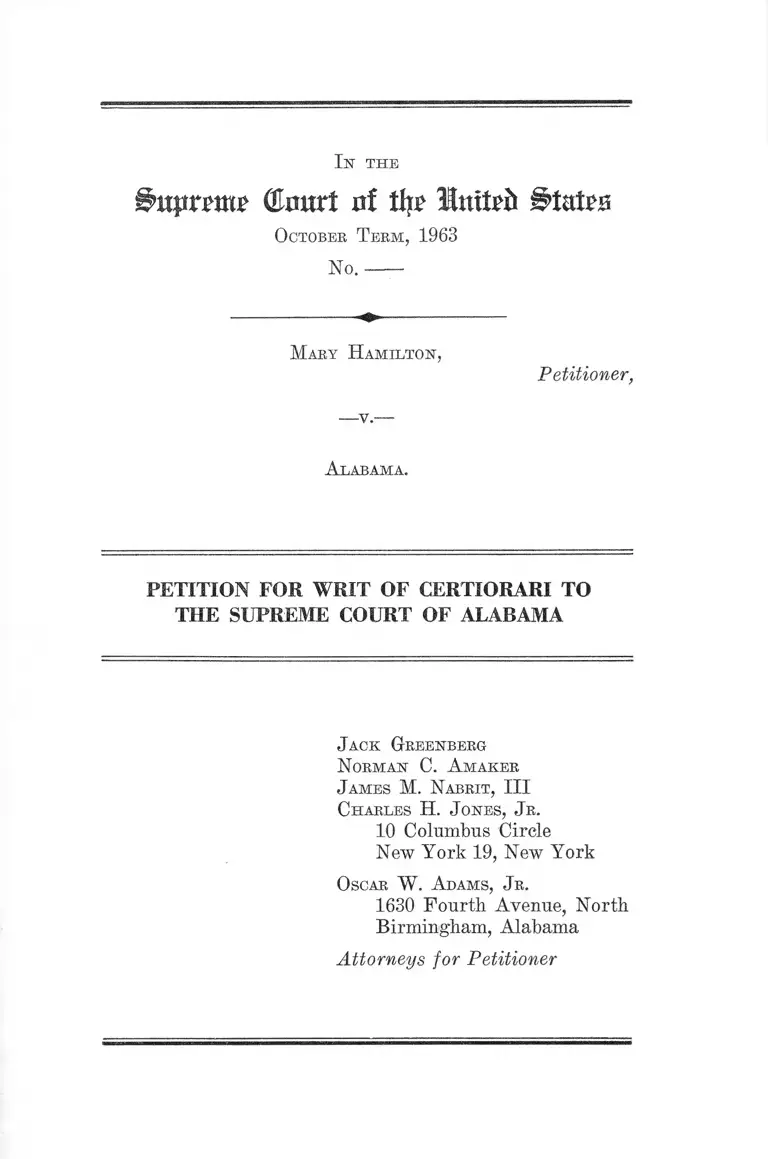

Hamilton v. Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari tothe Supreme Court of Alabama

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hamilton v. Alabama Petition for Writ of Certiorari tothe Supreme Court of Alabama, 1963. 88227e40-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d8cc474d-b077-4538-b2f6-354b143cbc08/hamilton-v-alabama-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-tothe-supreme-court-of-alabama. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(Ciuirt nf % United Butts

October T erm, 1963

No.-----

Mary H amilton,

Petitioner,

—v.-

Alabama.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

J ack Greenberg

Norman C. Amaker

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles H. J ones, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Oscar W. Adams, J r.

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below.................... -.................—.....— ........... 1

Jurisdiction ..................... .............................*..............1

Questions Presented .................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved...... 3

Statement ............................................................. ....... 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ ... ..............—............... 7

I. This case involves a significant form of racial

discrimination affecting the fair administra

tion of justice in the courts and petitioner’s

contempt conviction sanctioned such discrim

ination in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment ...... - .....- .................................................. 7

II. The failure to afford petitioner notice and a

hearing before punishing her for contempt

was a denial of due process of law ........ ......... 19

Conclusion ................ ........... -....... ............................. ...... 24

Appendix.......................................................................... 25

Opinion Below........................................... .............. 25

Judgment ................................................... - .... -...... 28

Denial of Rehearing ................................ .......... —- 29

T able of Cases

page

Alford v. United States, 282 U. S. 687 ......................... 17

Bell v. State, 16 Ala. App. 36, 75 So. 181 ...... ........... 17

Berger v. United States, 295 U. S. 78 ....... ........... ..... 17

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 ........ .............. ............ 9

Cooke v. United States, 267 U. S. 517 ....... ............. . 20

Ex parte Dickens, 162 Ala. 272, 50 So. 218 (1909) .... 6

Ex parte Terry, 128 U. S. 289 ................... ..................... 20

Garret v. State, 268 Ala. 299, 105 So. 2d 541 ..... ......... 17

George v. Clemmons, 373 U. S. 241 ........................... 8

Havens v. State, 24 Ala. App. 288, 134 So. 814, cert,

denied 134 So. 815, 323 Ala. 98 (1930) ..................... 18

In re McConnell, 370 U. S. 230 ...... ............................. 23

Jencks v. United States, 353 U. S. 657 ........................ 17

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61 _______ _____ ____8,17

Loeb v. Webster, 213 Ala. 99, 104 So. 25 ..................... 17

Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 264 .................................... 8

O’Neil v. State, 189 Wis. 259, 207 N. W. 280 (1926) .... 17

Panico v. United States, 375 U. S. 29 ........... .............1, 22

People v. LaFrance, 8 Cal. 839, 92 P. 2d 465 .............. 17

Re Green, 369 U. S. 689 .................... .......................... 21

Re Oliver, 333 U. S. 257 ...........................................20, 21, 22

11

I l l

Sanford v. State, 38 Ala. 332, 83 So. 2d 254 .............. 17

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ............................. . 8

State v. Bessa, 115 La. 259, 38 So. 985 (1905) ........... 17

State v. King, 222 S. C. 108, 71 S. E. 2d 793 ............. 17

State v. Murdock, 183 N. C. 779, 111 S. E. 610__ 17

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 .................. 8,9

Taliaferro v. United States, 47 F. 2d 699 (1931) ___ 17

Thomas v. Dorsey, 15 Ala. App. 419, 73 So. 747 ...... 17

Tribue v. State, Fla. App., 106 So. 2d 630 .......... 17

Ungar v. Sarafite, 375 U. S. 809 .......... ..... ................... 23

Viereck v. United States, 318 U. S. 236 .................. . 17

White v. State, 135 Tex. Cr. 210, 117 S. W. 2d 450

(1938) ........................ .... ........................................... 17

Statutes I nvolved

18 U. S. C. §401 ...................................... 23

28 U. S. C. §1257(3) .................... 1

42 U. S. C. §1981 (Civil Rights Act of 1870) . 16

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure 42(a) ...... 23

Ala. Code of 1940, Tit. 13, Section 2 ....................... 3

Ala. Code, Tit. 15, Sec. 341 (1958) ........... 5

Ala. Code, Title 7, §442 (1958) ... 18

La. Stats. Anno. R.S. 14:317 ....................................... 9

S. C. Code (1962), §58-1333

PAGE

9

IV

Other Authorities

page

21 Ala. Lawyer 193 (1960) ....... ........................... ........ 17

Baldwin, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1954) ........... . 13

Baldwin, Nobody Knows My Name (1963) ............... . 13

Bentham, Rationale of Judicial Evidence, Volume II,

Chapter V ........... ....... .............. ..... .............................. 17

A. Davis & Dollard, Children of Bondage (1940) ....... 13

A. Davis, B. Gardner & M. Gardner, Deep South (1941) 13

Dawes, “Titles and Symbols of Prestige in 17th Cen

tury New England”, William and Mary College

Quarterly (Jan. 1949) ......... 14

Dollard, Caste and Class in a Southern Town (3rd ed.

1957) ........................................................................ 10

Doyle, The Etiquette of Race Relations in the South

(1937) ............... 11,12

Elkins, Slavery (Universal Library Ed. 1963).......... . 16

Ellison, The Invisible Man (1947) ............................ 13

1 Encyclopedia Britannica, University of Chicago

(1963 ed.) .................................... 14

C. S. Johnson, Patterns of Negro Segregation (1943) ..10,13

Johnson, Growing Up in the Black Belt (1941) .......... 13

Johnson, To Stem This Tide (1943) ............ ................ 13

Moton, What the Negro Thinks (1929) .....................12,13

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944) .......... ......... 10

Nettels, The Roots of American Civilization: A His

tory of American Colonial Life (1938) ..................... 14

V

New York Times Magazine, Dec. 8, 1963 _____ ___

Patterson, Colour and Culture in South Africa (1953)

Richmond, The Colour Problem (1955) ...................

Smith, Strange Fruit (1948) ....... ................................

Wigmore on Evidence.................................

Wright, Native Son (1957) .................................... ....

Wright, Black Boy (1951) .........................................

... 15

.. 14

... 14

... 14

18,19

.. 13

.. 13

PAGE

I n th e

(Em it! ni % United

October T erm, 1963

No.-----

Mary H amilton,

Petitioner,

—v.—

Alabama.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama which was

entered September 26, 1963, rehearing of which was de

nied October 31, 1963.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama of Sep

tember 26, 1963, is reported at 156 So. 2d 926 and is set

forth in the appendix, infra p. 25. No opinion was given

by the Circuit Court of Etowah County, Alabama..

Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court of Alabama entered its judgment on

September 26, 1963 (R. 8), and denied rehearing on Oc

tober 31, 1963 (R. 14). The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1257(3), petitioner having

2

asserted below and here the deprivation of rights, privi

leges, and immunities secured by the Constitution of the

United States.

Questions Presented

Whether petitioner was denied rights protected by the

due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment when she was summarily fined and imprisoned

for contempt of court in the following circumstances:

1. Petitioner, a Negro, was a witness in her own behalf

at a habeas corpus hearing in an Alabama court. Through

out the hearing the solicitor representing the State per

sisted in the degrading custom of addressing ail Negro

witnesses by their first names, declining to call them “Mr.”

or “Miss” or to use their surnames as he did with all white

witnesses, and was sustained in this conduct by the trial

judge. Petitioner was held in contempt of court when the

prosecutor insisted upon addressing her as “Mary” and she

said that she would not answer his questions until he ad

dressed her “correctly.”

2. The trial judge ordered petitioner to answer, and

upon her statement that she would not answer until she

was “addressed correctly,” immediately and summarily

held her in contempt and sentenced her to a fine and im

prisonment, without affording her notice of the contempt

charge or a hearing.

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. This case involves section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

2. This case involves Alabama Code of 1940, Title 13,

Section 2, which provides:

Powers of court to inflict summary punishm ent —

The powers of the several courts in this state to issue

attachments and inflict summary punishment for con

tempts, does not extend to any other cases than:

Disrespectful, contemptuous, or insolent behavior in

court, tending in anywise to diminish or impair the

respect due to judicial tribunals, or to interrupt the

due course of trial.

A breach of the peace, boisterous conduct, violent

disturbance, or any other act calculated to disturb or

obstruct the administration of justice, committed in

the presence of the court, or so near thereto as to have

that effect.

The misbehavior of any officer of the court, in his

official transactions, or the disobedience or resistance

of any officer of the court, party, juror, witness, or any

other person, to any lawful writ, process, order, rule,

decree, or command thereof.

Deceit, or the abuse of the process of the proceed

ings of the court, by any person or party, or any un

lawful interference with the process or proceedings of

the court.

Refusing to be sworn, or to answer, either in the

court or before the grand jury, any lawful question as

a witness or garnishee.

When summoned as a juror in a court, improperly

conversing with a party to an action, to be tried at

4

such court, or with any other person in relation to the

merits of such action, or receiving a communication

from a party, or other person, in respect to it, without

immediately disclosing same to the court.

Conversing with a juror, knowing him to be such, in

relation to the merits of any action which he is en

gaged in the trial o f; or supplying any juror with any

refreshments of any kind, except water, during the

time he is engaged in the trial of any cause, without

leave of the court.

Statement

On June 25, 1963, petitioner was held in contempt of the

Circuit Court of Etowah County, Alabama and sentenced

to five days in jail and a fine of fifty dollars (R. 2). On that

day petitioner was a witness in her own behalf at a hear

ing on a petition for a writ of habeas corpus, during which

the state solicitor persisted in addressing all Negro wit

nesses by their first names. When petitioner’s counsel

objected the trial judge overruled him (R. 2, 3), saying on

one occasion, “I ’m not going to tell a lawyer how to address

a witness” (R. 3). The solicitor addressed only the Negro

witnesses by their first names (R. 3).

When the solicitor began cross-examining petitioner he

asked her name and she replied, “Miss Mary Hamilton”

(R. 2). Addressing her as “Mary,” he asked who arrested

her (id.). She replied that her name was Miss Hamilton

and said, “Please address me correctly” (id.). Ignoring this

request, the solicitor repeated his question, this time add

ing “Mary” at the end (id.). She said she would not

answer “until I am addressed correctly” and one of her

attorneys interjected that her name was Miss Hamilton

(id.). The judge then said, “Answer the question” (id.).

5

Petitioner again said she would not answer unless ad

dressed correctly (id.). The judge said, “You are in. con

tempt of court.” One of petitioner’s attorneys attempted

to speak at this point saying, “Your honor—your honor—”,

but the court immediately sentenced petitioner to jail and

to a fine.1

Petitioner immediately began serving the sentence and

completed the five day jail term, but was admitted to bond

pending review of the conviction before serving additional

time in jail for nonpayment of the fine2 (R. 1).

On July 25, 1963, petitioner sought review of her sen

tence of contempt by filing a petition for writ of certiorari

in the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 1), the method under

1 The entire sequence of events appears in the following lines of

the record (R. 2) :

“Cross examination by Solicitor Rayburn;

Q. What is your name, please?

A. Miss Mary Hamilton.

Q. Mary, I believe—you were arrested—who were you arrested

by?

A. My name is Miss Hamilton. Please address me correctly.

Q. Who were you arrested by, Mary?

A. I will not answer a question—

By Attorney Amaker: The witness’s name is Miss Hamil

ton.

A. —your question until I am addressed correctly.

The Court: Answer the question.

The Witness: I will not answer them unless I am ad

dressed correctly.

The Court: You are in contempt of court—

Attorney Conley: Your Honor—your Honor—

The Court: You are in contempt of this court, and you

are sentenced to five days in jail and a fifty dollar fine”

(R. 2).

2 Petitioner is liable to serve an additional 20 days in jail in

default of payment of the fine. Alabama Code, Title 15, Section

341 (1958).

6

Alabama law for securing review of a contempt conviction

(Ex parte Dickens, 162 Ala. 272, 50 So. 218 (1909)). The

Alabama Supreme Court denied the petition for writ of

certiorari on September 26, 1963 (R. 8) with an opinion on

the merits (R. 5).

The petition for certiorari filed with the Alabama Su

preme Court alleged that petitioner’s contempt conviction

violated the equal protection and due process clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment, asserting inter alia:

Petitioner avers that her conviction of contempt in

these circumstances was erroneous, unjustified, illegal,

null and void, contrary to the decision of this Court

and violated her right to the equal protection of the

laws and due process of law guaranteed under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States (R. 2-3).

The verified petition filed in the Alabama Supreme Court,

which alleged the circumstances of the contempt conviction

was not contradicted by the State and was accepted by the

court below as true. Briefs were filed, and the court below

ruled on the merits against petitioner’s claims, holding that

the trial court had power to inflict summary punishment

under Alabama Code, Title 13, Section 2, and saying that

(R.7):

* * * the question was a lawful one and the witness

invoked no valid legal exemption to support her re

fusal to answer it.

The record conclusively shows that petitioner’s name

is Mary Hamilton, not Miss Mary Hamilton.

Many witnesses are addressed by various titles, but

one’s own name is an acceptable appellation at law.

This practice is almost universal in the written opin

ions of courts.

7

In the cross-examination of witnesses, a wide latitude

is allowed resting in the sound discretion of the trial

court and unless the discretion is grossly abused, the

riding of the court will not be overturned. * * * We

hold that the trial court did not abuse its discretion

and the record supports the summary punishment in

flicted.

Petitioner’s application for rehearing and for stays pend

ing review in this Court were denied without opinion (R.

12, 14), but petitioner has remained at liberty and has not

yet served the remaining portion of the sentence.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I. This case involves a significant form of racial discrim

ination affecting the fair administration of justice in the

courts and petitioner’s contempt conviction sanctioned such

discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Petitioner was convicted of contempt for refusing to

respond to questions as a witness when the solicitor repre

senting Alabama insisted upon addressing her by her first

name. It is uncontroverted that the solicitor took such

familiarities only with the Negro witnesses who testified

at the hearing, and that he persisted notwithstanding ob

jections. Indeed, it is patent that the solicitor, who insisted

upon calling petitioner “Mary” even when she asked him

not to, was deliberately making a point of addressing her

familiarly by her first name. While the significance of this

differential treatment is apparent only in the context of

the racial caste system, on the surface it is clear that there

was a racial discrimination. A public official, the solicitor

representing the state in proceedings in its courts, and as

such accountable for his conduct under the Fourteenth

8

Amendment (cf. Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 264), accorded

petitioner and other Negroes a different treatment than

that accorded white witnesses. A state court, also subject

to the Fourteenth Amendment (cf. Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 XJ. S. 1), sanctioned and enforced the solicitor’s dis

criminatory conduct by punishing petitioner for contempt

when she refused to submit to the prosecutor’s umvarrant-

edly familiar mode of addressing her.

The decision belowT clashes sharply with two interrelated

lines of authority in this Court. First, Johnson v. Virginia,

373 U. S. 61, and George v. Clemmons, 373 U. S. 241, hold

that the State may not inflict the penalty of contempt upon

a Negro because he refused to obey an order relegating

him to a segregated section of the courtroom. Second,

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, holds that the

judicial process may not be used to brand a stamp of

inferiority on a Negro party litigant. Both are different

aspects of a common concern that the State, and particularly

its instruments of justice, must keep out of the business of

maintaining a racial caste system in the United States.

Johnson v. Virginia, supra, was, of course, not concerned

merely with the abstract question of whether persons may

be separated from one another physically. A court may

invoke the rule of exclusion and require witnesses to leave

the courtroom. If the court had decided to seat spectators

in alphabetical order, or to separate them according to

whether they were plaintiffs or defendants without regard

to race, Johnson certainly would have had no complaint.

The constitutional vice in separating Johnson from others

was that it enforced a racial caste status, with all the in

feriority which that has come to imply in the light of our

history.

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, written with

the memory of the slave system still fresh, recognized that

the vice in segregation (in that case in the form of exclu

9

sion from juries) is not gross physical separation, or

indeed prejudice to a particular litigant in the sense that

members of another race might be most likely to vote

against him. Rather, the evil was that exclusion of Negroes

from juries “is practically a brand upon them, affixed by

law; an assertion of their inferiority, and a stimulant to

that race prejudice which is an impediment to securing to

individuals of the race that equal justice which the law

aims to secure to all others” (100 U. S. at 308).3

Of course, a racially inferior caste status can be imposed

in ways other than physical separation. A familiar exam

ple of discrimination without separation is the law which

allows Negro servants or employees to occupy facilities

otherwise limited to whites.4 The crux of the matter is

status, not spatial separation.

Petitioner’s reaction to being called “Mary” in a court

room where, if white, she would have been called “Miss

Hamilton,” was not thin-skinned sensitivity. She was re

sponding to one of the most distinct indicia of the racial

caste system. This is the refusal of whites to address Ne

groes with titles of respect such as “Miss,” “Mrs.” or “Mr.”

and to refer to them as “boy” or “girl.”

The literature of race relations abounds with recogni

tion of the key role played by this difference in modes of

address. Myrdal writes:

3 That the line of eases descending from Strcmder does not rest

upon a concept of injury to a particular defendant is evidenced

by Cassell v. Texas, 339 U, S. 282. In that case there was indict

ment by a grand jury from which Negroes had been systematically

excluded (indeed, there was also systematic inclusion of Negroes),

but no claim of such exclusion or inclusion with respect to the

petit jury. See Justice Jackson’s dissent, 339 IT. S. at 298, et seq.

4 See, e.g., S. C. Code (1962), §58-1333 (a Negro woman can

ride in white car of train if accompanying white child) and La.

Stats. Anno. R. S. 14:317 (exception to residential segregation law

for employees).

10

The Negro is expected to address the white person by

the title of “Mr.,” “Mrs.,” or “Miss.” The old slavery

title of “Master” disappeared during Deconstruction

entirely and was replaced by “Boss” or sometimes

“Cap” or “Cap’ll.” From his side, the white man ad

dresses the Negro by his first name, no matter if they

hardly know each other, or by the epithets “boy,”

“uncle,” “elder,” “aunty,” or the like, which are ap

plied without regard to age. If he wishes to show a

little respect without going beyond the etiquette, he

uses the exaggerated titles of “doctor,” “lawyer,”

“professor,” or other occupational titles, even though

the term is not properly applicable. [2 Myrdal, A x

A mericas' D ilemma 611 (1944).]

* # m * #

In all articulate groups of Negroes there is a demand

to have white men call them by their titles of Mr.,

Mrs., and Miss; to have white men take off their hats

on entering a Negro’s house; to be able to enter a white

man’s house through the front door, rather than the

back door, and so on. [1 Myrdal, A x Americax

Dilemma 64 (1944).]

and John Dollard makes the same point in Caste and Class

in a Southern Town:

In Southerntown the use of “Mrs.” as a white-caste

mark and the omission of it in speaking to Negroes

have great emotional value. The Negroes know that to

omit the “Mr.” in referring to a white man would al

ways mean that the addressee could enforce his right

in some uncomfortable way. The main fact is that

behind deference from the Negroes is the demand for

deference by the whites and the ability to secure it by

11

force if it is not willingly given. [Dollard, Caste and

Class in a Southern T own 179 (3rd ed. 1957).]

-Sf. Jf. M.W • * . W •TV'

Negroes are called by their first names without respect

to their wishes, as are children. (Id., p. 435.)

In Patterns of Negro Segregation, Charles S. Johnson has

written:

Otherwise, only a few whites, usually those who are

socially or economically secure, can freely use titles of

respect in addressing Negroes. This taboo is deep-

seated, involving in a complicated manner, the status,

self-interest, and self-conception of the individual

white person. [C. S. J ohnson, P atterns of Negro

Segregation 140 (1943).]

# # # # #

Formal salutations in letters also fall under the eti

quette. When a letter is being addressed to a person

known to be a Negro, “My dear” and “Sir” are self

consciously omitted. The letter begins simply “John,”

or there is no salutation at all, and the envelope carries

no title for the name. A prominent Negro woman,

president of a state parent-teacher organization in

Louisiana, wrote the governor, regarding a question of

public concern. She received a reply from the gover

nor’s secretary addressing her, without formal saluta

tion, simply as “Huggins.” (Id., p. 143.)

In The Etiquette of Race Relations in the South, B. W.

Doyle has written:

Negroes normally greet white men with the title “Mis

ter.” . . . Occasionally, however, “cap” or “eap’n” or

even the round term “boss” may be substituted for

“mister,” or even just “white folks” may be used. If the

12

white persons are well known, Negroes may address

them by the intimate “Mr. John” or “Miss Mary,”

as the case may be. If, however, formality is required

the forms may be changed to “Mr. So-and-so” or

“Miz . . . So-and-so.” [Doyle, T he E tiquette of

R ace R elations in the South 142 (1937).]

On the other hand, white persons are not expected

to address Negroes as “mister” ; but “boy” is still

good usage as a term to address Negro males of all

ages. Even “nigger” is occasionally used. . . . This

term does not strictly conform to what is accepted,

for Negroes resent it occasionally. Where these terms

are not used, the ubiquitous “Jack” and—as on Pull

man cars—“George” and “boy” are in good form.

{Id., pp. 142-143.)

Robert Moton, too, describes this phenomenon in What

the Negro Thinks:

It is to be expected that those persons who find it

impossible to give the same consideration in cold

type to Negroes which they give to people of other

races will find it no more easy to give them the same

consideration in personal contacts and in the ac

cepted amenities of our order of civilization; for

which reason these same people simply refuse to refer

to or address any Negro man or woman as “Mr.” or

“Mrs.” or “Miss,” regardless of any legal signifi

cance in those terms, especially the title “Mrs.” The

habit of slavery days was to address the slave by

a given name—few of them had any other. If any

distinction was to be made between slaves of the same

given name on different plantations, the master’s name

was employed in the possessive as “Thompson’s

13

John” or “Hightower’s Jim.” With advancing years,

if endowed with sufficient personal dignity and other

elements of character, that individual became “Uncle

Jim,” and in the case of women “Aunt Harriet,”

instead of simply “Harriet.” When the slave became

a free man, many of them simply adopted the names

of their former masters, but in the order charac

teristic of a free man; and so he styled himself John

Thompson or James Hightower. With it also they

adopted the titles of Western democracy “Mr.,”

“Mrs.,” and “Miss.” There are many who regard this

as a presumption, but in the mind of the Negro it

registers not only his respect for himself but Ms re

spect also for both men and women in his own race_

a distinct gain over the lack of respect characteristic

of the status of a slave. [Moton, W hat the Negro

T hinks 190-191 (1929).]

See also: A. Davis & Dollard, Children of B ondage

18-19, 239 (1940); A. Davis, B. Gardner & M. Gardner,

Deep South 22, 23, 24 (1941); J ohnson, P atterns of Negro

Segregation 121,122,135, 138,139,140-143, 206, 207 (1943);

J ohnson, Growing U p in the B lack Belt 277, 278 (1941);

J ohnson, T o Stem T his T ide 112 (1943); Moton, W hat

the Negro T hinks 190-192, 194-196, 215 (1929).

The social effects of maintaining status in this way

have been noted elsewhere in American literature as a

particularly distinctive indication of racial caste. See:

W right, Native Son 57-58, 177, 258-260, 285 (1957);

W right, Black B oy 199-200, 208-209 (1951); see also:

Baldwin, Nobody K nows My Name 28, 112 (1963); B ald

w in , Go Tell I t on the Mountain 146-147 (1954); E llison,

14

T he I nvisible Man 384 (1947); Sm ith , Strange F ruit 16,

84-85, 92, 141 (1948).

The maintenance of racial caste status by means of titles

of address is not unique to the United States.5 With re

spect to British colonial countries, Anthony H. Richmond in

The Colour Problem has written:

Many Europeans show marked discourtesy to Africans

and demand an excessively servile demeanour from

them. The European tends to use forms of address,

such as “boy,” “nigger,” “wog,” and “kaffir,” when ad

dressing or talking about Africans, who very much

resent these expressions and the tone of voice that

goes with them. [R ichmond, T he Colour P roblem 150

(1955).]

And see Sheila Patterson’s Colour cond Culture in South

Africa:

In addressing or referring to other whites whom they

do not know well, Afrikaners use the titles Meneer,

Mevrou and Mejuffrouw, for “Mr.,” “Mrs.,” and

“Miss” respectively. It is one of the biggest griev

ances of urban Coloureds who have achieved some

status within their own community that comparatively

few Afrikaners will accord them these titles. Low-

class whites are said to ignore all titles, but better-

educated ones will sometimes use such titles as

“Reverend,” “Doctor” and so on, wherever it is possi

ble. [P atterson, Colour and Culture in South

A frica 140 (1953).]

5 For origin of the title “Mr.” as used in the United States see:

NETTBLS, THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN CIVILIZATION:

A HISTORY OF AMERICAN COLONIAL LIFE 327 (1938);

DAWES, “TITLES AND SYMBOLS OF PRESTIGE IN 17TH

CENTURY NEW ENGLAND,” WILLIAM AND MARY COL

LEGE QUARTERLY 69-83 (Jan. 1949); 1 ENCYCLOPAEDIA

BRITANNICA, University of Chicago 134d (1963 ed.).

15

Indeed, more recently, upon Kenya becoming an inde

pendent nation, the Minister of Justice and Constitutional

Affairs mentioned prominently among the indicia of racial

discrimination there the mode of address which had come

into usage during colonial days, and directly compared it

to that in the United States:

Many U. S. citizens will know the sort of thing we had

to put up with: the separate queues and counters, the

exclusion from hotels, restaurants and clubs in our

own country. Hospitals, schools, housing and social

services were provided on a descending scale of ade

quacy—Europeans, Asians, Africans. An individual

African’s ability to pay opened no doors for him. To

the racialist settlers, he was a Black, just a “boy,”

hardly human. [N. 7. Times Magazine, December 8,

1963, pp. 24, 112.]

In the United States this use of the term “boy” and the

omission of titles of respect when ordinarily they would be

accorded whites, has its roots in slavery. In the recent,

authoritative evaluation of slavery’s role here Stanley M.

Elkins has written:

The Negro was to be a child forever. “The Negro . . .

in his true nature, is always a boy, let him be ever so

old. . . . ” “He is . . . a dependent upon the white race;

dependent for guidance and direction even to the pro

curement of his most indispensable necessaries. Apart

from this protection he has the helplessness of a child

—without foresight, without faculty of contrivance,

without thrift of any kind.” Not only was he a child;

he was a happy child. Few Southern writers failed to

describe with obvious fondness the bubbling gaiety of

a plantation holiday or the perpetual good humor that

seemed to mark the Negro character, the good humor

16

of an everlasting childhood. [E lkins, Slavery 132

(Universal Library Ed. 1963).]

w w w w

Might the process, on the other hand, be reversed? It

is hard to imagine its being reversed overnight. The

same role might still be played in the years after slav

ery—we are told that it was6—and yet it was played to

more vulgar audiences with cruder standards, who

paid much less for what they saw. The lines might be

repeated more and more mechanically, with less and

less conviction; the incentive to perfection could be

come hazy and blurred, and the excellent old piece

could degenerate over time into low farce. There could

come a point, conceivably, with the old zest gone, that

it was no longer worth the candle. The day might

come at last when it dawned on a man’s full waking

consciousness that he had really grown up, that he was,

after all, only playing a part. {Id., at 133.)

During slavery the southern states are said to have uni

versally prohibited slaves from testifying in court, except

against each other (Elkins, op. cit. supra 57), and the Civil

Rights Act of 1870 addressed itself to this by providing

that “all persons . . . shall have the same right . . . to sue,

be parties, give evidence . . . as is enjoyed by white citi

zens___ ” (42 U. S. C. §1981).

It is no more the legitimate business of the states’ courts

to maintain the racial caste system by using the contempt

power in support of racially demeaning forms of address

ing Negroes by public officials than it is the states’ busi

6 Even Negro officeholders during Reconstruction, according to

Francis B. Simians, “were known to observe carefully the etiquette

of the Southern caste system.” “New Viewpoints of Southern

Reconstruction,” Journal of Southern History V (February, 1939),

52. [This footnote is from the original.]

17

ness to do the same thing by physical segregation. Johnson

v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61.

The trial court had two choices, to compel the witness to

answer by contempt, or to require the prosecutor to cease

his racial abuse. That the latter course would have been

correct, is dictated by well accepted legal principles gov

erning examination of witnesses as well as by the Four

teenth Amendment. This Court has held that a prosecuting

attorney is a quasi-judicial officer of the court and under a

duty not to prejudice a party’s case through overzealous

prosecution, Berger v. United States, 295 U. S. 78; Jencks

v. United States, 353 U. S. 657; Taliaferro v. United States,

47 F. 2d 699 (1931); see also: O’Neil v. State, 189 Wis. 259,

207 N. W. 280 (1926).7

Moreover, the prosecutor has a responsibility not to

detract from the impartiality of the courtroom atmos

phere.8

It is the plain duty of the court to interfere, on objec

tion or without, if an attempt is made by counsel to brow

beat, insult, or intimidate witnesses. Alford v. United

7 Because of the special relationship between prosecuting attor

ney and court the prosecutor must avoid conduct which is abusive

to the witness, People v. LaFrance, 8 Cal. 839, 92 P. 2d 465-

State v. Murdock, 183 N. C. 779, 111 S. E. 610; State v. King, 222

S. C. 108, 71 S. E. 2d 793; Tribue v. State, Fla. App., 106 So. 2d

630; not engage in undignified conduct; Garret v. State, 268 Ala.

299, 105 So. 2d 541; Sanford v. State, 38 Ala. 332, 83 So. 2d 254;

Bell v. State, 16 Ala. App. 36, 75 So. 181; or conduct himself in

an harassing, intimidating, or insulting manner; Bentham, Ra

tionale of Judicial Evidence, Volume II, Chapter V.

8State v. Bessa, 115 La. 259, 38 So. 985 (1905) ; White v. State,

135 Tex. Cr. 210, 117 S. W. 2d 450 (1938); (see 21 Ala. Lawyer

193 (1960) address by Judge Walter P. Jones, Montgomery, Ala

bama) ; he must avoid making inflammatory argument to the jury,

Viereck v. United States, 318 U. S. 236; and appeals to racial

prejudice during the course of his argument, Loeb v. Webster,

213 Ala. 99, 104 So. 25; Thomas v. Dorsey, 15 Ala. App. 419, 73

18

States, 282 U. S. 687; Havens v. State, 24 Ala. App. 288,

134 So. 814 , cert, denied 134 So. 815, 323 Ala. 98 (1930).

The Alabama courts have indicated recognition of the

higher interests to he served, as between allowing a wit

ness to be intimidated or harassed, or exempting the wit

ness from testimonial compulsion. In Havens, supra, the

court said:

The court should refuse to compel a witness to an

swer a question which is put for the purpose of har

assing him rather than testing his credibility. The

foregoing questions were so apparently for the pur

pose of humiliating or harassing the witness, rather

than for the purpose of impeachment, that the court

properly exercised his discretion in refusing to per

mit the witness to answer. Havens v. State, supra, at

815.®

The Alabama legislature has erected protections around

the witness to support the same policy. Alabama Code,

Title 7, §442 (1958) reads:

It is the right of the witness to be protected from

improper questions and from harsh or insulting de

meanor.

This case does not present the often difficult question

posed by Fifth Amendment or First Amendment claims of

privilege, for in those cases if the claim is upheld, the court

will be deprived of evidence which may lead to ascertaining

the truth. In other words, in those cases it is held, in 9

9 These considerations have a general importance in the admin

istration of justice in that potential witnesses often walk away

from a situation concerning which they may be called to testify,

and potential litigants forego rights because going to court involves

the possibility of harassment and abuse. See: Wigmore on Evi

dence, §2192, p. 67.

19

effect, that the social interest in protecting the witness

is greater than the interest in learning the facts. See

Wigmore on Evidence, §2196, p. 111. In this case the

truth can he secured by forbidding racial abuse of the

witness. But racial abuse of the witness cannot be stopped

except by following the course which Miss Hamilton under

took in this case and by reversing the conviction of con

tempt.

II. The failure to afford petitioner notice and a hearing be

fore punishing her for contempt was a denial of due

process of law.

The Supreme Court of Alabama held:

Here, the question was a lawful one and the witness

invoked no valid legal exemption to support her re

fusal to answer it . . . [T]he record supports the

summary punishment inflicted (E. 7).

The juxtaposition of these two sentences illumines the

fundamental procedural unfairness of petitioner’s con

viction.

It is true that petitioner was summarily convicted.

It is also true that petitioner was given no reasonable

opportunity to prepare and present a defense invoking a

“valid legal exemption to support her refusal to answer.”

Her lawyer was given no opportunity to consult with her,

no opportunity to prepare a defense, no opportunity to call

witnesses, introduce evidence or otherwise present a de

fense. In fact, the petitioner’s attorney attempted to speak

but the court disregarded him and imposed sentence im

mediately upon the petitioner’s refusal to answer (E. 2).

This failure to provide her an opportunity to present a

defense and to invoke a state or federal “exemption” was

a denial of due process of law.

20

A person’s right to a reasonable opportunity to be heard

in his defense is basic in our system of jurisprudence.

Except for a narrowly limited category of contempts, due

process of law requires that one charged with contempt

of court be advised of the charges against him, have a

reasonable opportunity to meet them by way of defense or

explanation, and have a chance to testify and call other

witnesses in his behalf.

It is true that courts have long exercised a powrer sum

marily to punish certain conduct committed in open court

without notice, testimony or hearing. Ex parte Terry, 128

U. S. 289. But the holding in the Terry case is not to be

considered an unlimited abandonment of basic procedural

safeguards in contempt cases. Special circumstances were

presented in that case. There Terry assaulted the court

marshal who was attempting to remove a heckler from the

courtroom. This violent misconduct occurred under the eye

of the court and physically disrupted the trial court’s busi

ness. Under these circumstances, this Court held that the

judge had power to punish an offender at once, without

notice and hearing.

That this departure from accepted standards of due

process was to be limited to cases of court-disrupting

conduct was re-emphasized in Cooke v. United States, 267

U. S. 517. The court stressed that the Terry rule reached

only such conduct as created “an open threat to the orderly

procedure of the court in such a flagrant defiance of the

person and presence of the judge before the public [that

if] not instantly suppressed and punished, demoralization

of the court’s authority will follow” (267 U. S. at 536).

Re Oliver, 333 U. S. 257, crystallized the rule in this way:

The narrow exception to these due process require

ments [notice and hearing] includes only charges of

21

misconduct in open court in the presence of the judge

which disturbs the court’s business, where all of the

essential elements of the misconduct are under the

eye of the court, are actually observed by the court,

and where immediate punishment is essential to pre

vent “demoralization of the court’s authority before

the public.” 333 U. S. at 275.

In Oliver, a Michigan judge, conducting a “one-man

grand jury” investigation in accordance with statutory

authority, summarily adjudged Oliver, a witness before

the “grand jury”, to be in contempt of court because of

the apparent inconsistency of his testimony with that of

other witnesses. This Court held that the failure to afford

Oliver a reasonable opportunity to defend himself against

the charge of false and evasive swearing was a denial of

due process of law.

More recently, in Be Green, 369 U. S. 689, this Court

said, reversing an Ohio contempt conviction for lack of a

hearing:

We said in Ee Oliver, 333 U. S. 257, 275, 92 L. ed. 682,

695, 68 S. Ct. 499, that procedural due process “re

quires that one charged with contempt of court be

advised of the charges against him, have a reasonable

opportunity to meet them by way of defense or ex

planation, have the right to be represented by coun

sel, and have a chance to testify and call other wit

nesses in his behalf, either by way of defense or ex

planation.”

Petitioner was guilty of no misconduct that fell within

the category of acts which constitute contempt in

open court, where immediate punishment is neces

sary to prevent “demoralization of the court’s author

ity” (id. 333 U. S. at 275) or the other types of eon-

22

tempt considered in Brown v. United States, 359 U. S.

41, 3 L. ed. 2d 609, 79 S. Ct. 539 (369 U. S. at 691-92).

To sum up, the test which this Court has promulgated

is that summary convictions will only be permitted when

essential to prevent “demoralization of the court's au

thority before the public.”

Such a case is not presented by disobedience of a judge’s

order to answer questions, such as occurred here.

A refusal to answer questions may be privileged, either

as a matter of state or federal law. Put another way, one

of the essential elements of misconduct arising out of a

refusal to answer is that the refusal be without justifica

tion. Thus, a refusal to answer does not present a case

“where all the essential elements of the misconduct are

under the eye of the court.” 10

This proposition leads to a more central one. Simply

stated, permitting a witness to be heard in his own defense

does not demoralize the court’s authority; rather, it ren

ders that court more worthy of respect. This simple yet

fundamental proposition apparently impelled Mr. Justice

Black to caution in Re Oliver, supra:

The right to be heard in open court before one is

condemned is too valuable to be set aside under the

guise of “demoralization of the court’s authority.”

333 U. S. at 278.

10 Another case where all the essential elements of the miscon

duct are not under the eye of the Court is where insanity is prop

erly interposable as a defense against a charge of contemptuous

misconduct. This was illustrated in the federal system by the case

of Panico v. United States, 375 U. S. 29. There, this Court held

that summary punishment could not be imposed for undisputedly

contemptuous misconduct in open court if some question existed

as to sanity of the putative eontemnor.

23

The guarantees of the due process clause, as we have

seen, may only be curbed through imperative necessity.11

Such necessity did not exist in this case. Petitioner’s re

fusal to answer did not require instant punishment. Her

attempt to justify her refusal to answer did not require

instant suppression. Her case does require reaffirmation

of the traditional constitutional right to notice and a

hearing before imposition of a jail sentence.12

11 What constitutes such necessity in the federal system was

limned by In Be McConnell, 370 U. S. 230, where it was held un

warranted to punish by summary proceeding under 18 U. S. C.

§401 and Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rule 42(a) the

refusal of counsel to abandon a line of questioning forbidden by

the judge. There this Court said:

[BJefore the drastic procedures of the summary contempt

power may be invoked to replace the protections of ordinary

constitutional procedures there must be an actual obstruction

of justice . . .

[TJhere was nothing in petitioner’s conduct sufficiently dis

ruptive of the trial court’s business to be an obstruction of

justice. It is true that petitioner stated that counsel had a

right to ask questions that the judge did not want asked and

that “we propose to do so unless some bailiff stops us.” The

fact remains, however, that the bailiff never had to interrupt

the trial by arresting petitioner, for the simple reason that

after this statement petitioner never did ask any more ques

tions along the line which the judge had forbidden. And

we canot agree that a mere statement by a lawyer of his

intention to press his legal contention until the court has a

bailiff stop him can amount to an obstruction of justice. . . .

370 U. S. at 234-236.

12 That this case involves issues of constitutional importance is

evidenced by the noting of probable jurisdiction in TJngar v.

Sarafite, 375 U. S. 809 (October 14, 1963), which involves issues

similar to those presented here.

24

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is respectfully submitted

that the writ of certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Norman C. A maker

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles H. J okes, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Oscar W. Adams, J r.

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Petitioner

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

September 26,1963

T he State op Alabama—J udicial Department

T he Supreme Court op Alabama

Special Term, 1963

7 Div. 621

Ex parte Mary H amilton

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO ETOWAH CIRCUIT COURT

Merrill, Justice.

Petition for writ of certiorari to the Circuit Court of

Etowah County to review a conviction of contempt of

court.

Petitioner, Mary Hamilton, filed a petition for writ of

habeas corpus in the Circuit Court of Etowah County.

She was a witness in her own behalf and on cross examina

tion she refused to answer the third question propounded

to her. The trial court adjudged her to be in contempt and

sentenced her to serve five days in jail and fined her $50.

She has served the jail sentence.

The cross examination of petitioner was as follows:

“Q. What is your name, please! A. Miss Mary

Hamilton.

Q. Mary, I believe—you were arrested—who were

you arrested by! A. My name is Miss Hamilton.

Please address me correctly.

Q. Who were you arrested by, Mary! A. I will not

answer a question—

26

By Attorney Amaker: The witness’s name is Miss

Hamilton.

A. —your question until I am addressed correctly.

The Court: Answer the question.

The Witness: I will not answer them unless I am

addressed correctly.

The Court: You are in contempt of court—

Attorney Conley: Your Honor—your Honor—

The Court: You are in contempt of this court,

and you are sentenced to five days in jail and a fifty

dollar fine.”

The power of the several courts to inflict summary

punishment upon a witness for refusing to answer a lawful

question is specifically authorized in Tit. 13, §2, Code 1940.

“It is every man’s duty to give testimony before a duly

constituted tribunal unless he invokes some valid legal

exemption in withholding it.” Ullmann v. United States,

350 U. S. 422, 76 S. Ct. 497,100 L. Ed. 511.

Here, the question was a lawful one and the witness in

voked no valid legal exemption to support her refusal to

answer it.

The record conclusively shows that petitioner’s name is

Mary Hamilton, not Miss Mary Hamilton.

Many witnesses are addressed by various titles, but one’s

own name is an acceptable appellation at law. This practice

is almost universal in the written opinions of courts.

In the cross examination of witnesses, a wide latitude is

allowed resting in the sound discretion of the trial court

and unless the discretion is grossly abused, the ruling of

the court will not be overturned. Blount County v. Camp

bell, 268 Ala. 548, 109 So. 2d 678; Kervin v. State, 254 Ala.

27

419, 48 So. 2d 204. We hold that the trial court did not

abuse its discretion and the record supports the summary

punishment inflicted.

P etition for W rit of Certiorari Denied.

Lawson, Goodwyn and Harwood, JJ., concur.

28

T he Supreme Court oe Alabama

Thursday, September 26, 1963

T he Court Met in Special Session

P ursuant to Adjournment

Present:

Chief Justice L ivingston and

Associate Justices L awson, S impson, Goodwyn,

Merrill, Coleman and H arwood

7th Div. 621

Ex parte:

Mary H amilton,

Petitioner.

PETITION FOE WEIT OF CERTIOBABI

TO ETOWAH CIRCUIT COURT

Comes the petitioner, by attorneys, and the Petition for

Writ of Certiorari to the Circuit Court of Etowah County,

Alabama, being submitted and duly examined and under

stood by the Court,

I t is considered and ordered that the Petition be, and the

same and the same, is hereby denied, at the costs of the

petitioner, for which costs let execution issue.

29

T he Supreme Court oe Alabama

Thursday, October 31, 1963

T he Court Met P ursuant to A djournment

Present: All the Justices

7th Div. 621

Ex parte:

Mary H amilton,

Petitioner.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

CIRCUIT COURT OF THE SIXTEENTH JUDICIAL

CIRCUIT OF ALABAMA, ETOWAH COUNTY,

ALABAMA

(Re: Mary Hamilton vs. State of Alabama)

Etowah Circuit Court

I t is ordered that the application for rehearing filed on

October 9, 1963, be and the same is hereby overruled.

No Opinion Written on Rehearing.

â J8^£> 38