Draft Motion to Dismiss Appeals

Working File

January 1, 1971

14 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Draft Motion to Dismiss Appeals, 1971. d6938e86-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d8f46a2a-5a01-48c2-8695-c0018706c656/draft-motion-to-dismiss-appeals. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

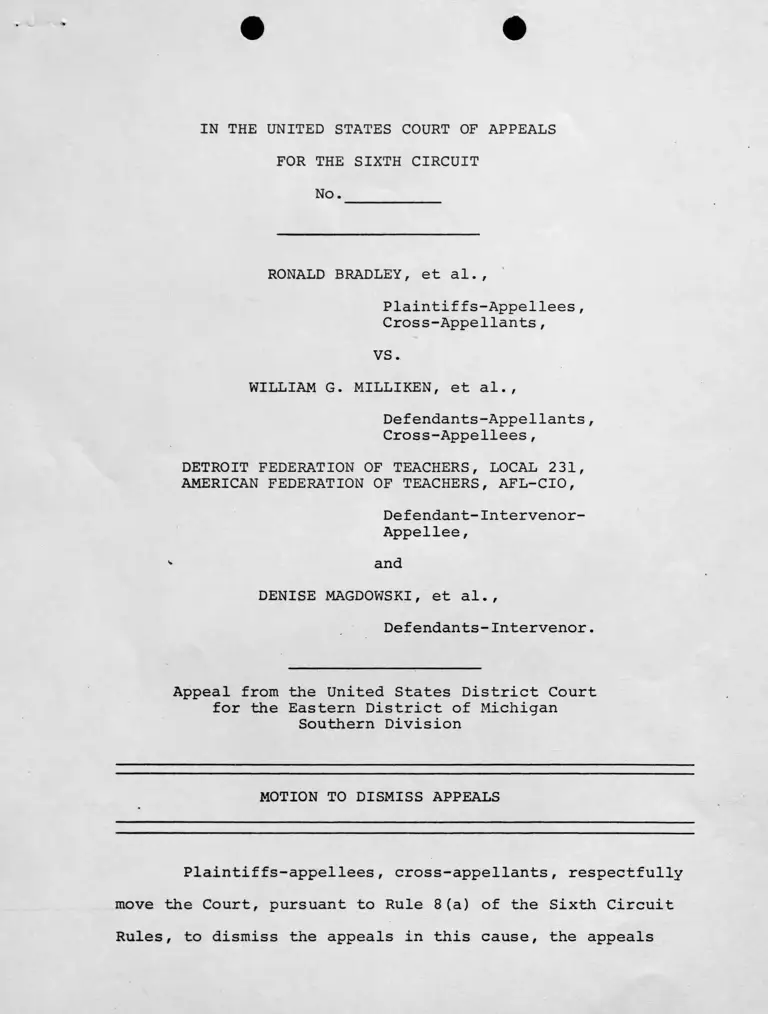

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No.

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

Cross-Appellants,

VS.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants,

Cross-Appellees,

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 231,

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor-

Appellee,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendants-Intervenor.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Michigan

Southern Division

MOTION TO DISMISS APPEALS

Plaintiffs-appellees, cross-appellants, respectfully

move the Court, pursuant to Rule 8(a) of the Sixth Circuit

Rules, to dismiss the appeals in this cause, the appeals

being not within the jurisdiction of the Court at this

juncture.

As grounds for this motion, plaintiffs would show

the following:

BACKGROUND

Procedural History of the Litigation

Plaintiffs commenced this litigation on August 18,

1970, against the Board of Education of the City of

Detroit, its members and superintendent of schools, the

Governor, Attorney General, State Board of Education and

State Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State

of Michigan. Plaintiffs challenged, on constitutional

grounds, a legislative enactment of the State of Michigan

which interferred with the implementation of a voluntary

plan of partial high school pupil desegregation which had

been adopted by the Detroit Board of Education. Plaintiffs

further alleged the existence of a racially identifiable

pattern of faculty and student assignments in the Detroit

Public Schools which pattern was the result of official

policies and practices of the defendants and their predecessors

in office.

At the conclusion of a hearing held upon plaintiffs'

application for preliminary injunctive relief the district

court denied all relief on the grounds that the existence

of racial segregation had not yet been established. The

court further dismissed the action as to the State defendants.

On appeal, this Court declared the challenged Michigan statute

to be unconstitutional and reinstated the State defendants

2

as parties. 433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970).

Upon remand, plaintiffs moved in the district court

for an order requiring immediate implementation of the volun

tary plan of partial desegregation which had been impeded by

the unconstitutional State statute. After receiving

additional plans preferred by defendants and conducting

a hearing thereon, the district court entered an order

approving an alternate plan which plaintiffs opposed

as being constitutionally insufficient. Plaintiffs again

«appealed, but this Court refused to reach the merits

of the appeal and remanded the case to the district court

with instructions that the entire case be tried on its

merits forthwith. 438 F.2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971).

After a lengthy trial the district court, on

September 27, 1971, entered its "Ruling on Issue of Segre

gation." (Attached hereto as Appendix A). The court

concluded that the public schools in Detroit are "segregated

on a racial basis" (App. A at 13) and that both state and

local defendants "have committed acts which have been causal

factors in the segregated condition...." (App. A at 21)

The court and the parties then turned to the problem

of relief. Plaintiffs sought (and seek) conversion of the

—^These findings and conclusions pertain to the pattern

of pupil assignments only, as the court declined to find

the pattern of faculty assignments to be unconstitutional

(as alleged by plaintiffs). (App. A at 15-20).

3

• •

Detroit school system from a racially segregated to a

racially unitary one. The intervening parent defendants.?/

had filed, at the conclusion of the trial, a motion to add

as parties defendant numerous suburban school districts "on

the principal premise or grounds that effective relief

cannot be achieved or ordered in their [other districts']

absence."2/ (App. A at 28). The court, however, deferred

decision on the content and extent of the remedy until the

completion of further proceedings. (App. A at 28-29).

On October 4, 1971, the district court conducted

a pre-trial conference (the transcript of which is attached

hereto as Appendix B) on the matter of relief. At the

conclusion of the conference the court directed both the

Detroit Board defendants and the State defendants to submit

proposed plans of pupil desegregation on specified dates.

(App. VB at 26-27). These directions were subsequently

incorporated into an order filed on November 5, 1971

(Appendix C, attached hereto). It is from this order that

2/Prior to the trial on the merits the district

court permitted the Detroit Federation of Teachers and a

group of white parents to intervene as parties defendant.

3/The parent-intervenors had intervened for the

purpose of defending the "neighborhood school concept,"

but had lost all hope of success by trial's end. (See

statement of attorney for parent-intervenors, App. B at 15).

4

both the Detroit Board defendants (Appendix D) and the

State defendants (Appendix E) noticed appeals on December

3, 1971. Although plaintiffs have, from the outset,

questioned the "appealability" of the district court's

order, we filed a protective notice of appeal (Appendix

F) on December 11, 1971, challenging the court's failure

to require further faculty desegregation.—^

The Substance of the Order Appealed From

4

At the pre-trial conference of October 4, 1971,

the district court directed the Detroit Board defendants

(1) to submit within 30 days a progress report on and an

evaluation of the Magnet School Plan (under which the

Board is presently operating), and (2) to submit within

60 days a plan for the desegregation of the Detroit public

schools. (App. B at 26-27). Further, the court directed

the State defendants to submit within 120 days a metro

politan plan of desegregation, "perhaps in more or less

skeletal form." (App B at 27)

4/— Plaintiffs question the propriety of their own

appeal at this juncture also. Plaintiffs feel/ however,

that their appeal is on sounder grounds than are the appeals

of defendants, for it would appear that the result which

plaintiffs challenge (refused to require further faculty

desegregation) is "final" (see infra), although this may

not necessarily be so. In any event, should plaintiffs

prevail in this motion to dismiss defendants' appeals,

plaintiffs would voluntarily dismiss their own appeal.

5

After these directions were delivered, the following

occurred:

THE COURT: ___ The time table is

understood, is it?

MR. BUSHNELL: Yes, sir.

MR. LUCAS: Yes.

THE COURT: I am not going to— unless you

gentlemen want--to prepare an order, I am not

going to prepare a formal order.

MR. BUSHNELL: I don't believe it is

necessary, your Honor. We understand the

the timetable.

THE COURT: Anybody disagree with that?

[No response]

(App. B at 29). Nevertheless, the State defendants sub

sequently insisted on a formal order (see Appendix G),

which was entered on November 5, 1971 (App. C).

In accordance with the court's direction the Detroit

Board defendants filed, on November 3, 1971, a report on

the Magnet School Program, and on December 3, 1971, they

submitted two alternative proposed plans for desegregation

of Detroit schools^/ and a statement setting forth the

Board's preference for metropolitan desegregation.

The metropolitan plan required to be submitted by

the State defendants is due to be filed within two weeks.

REASONS WHY THE APPEALS SHOULD BE DISMISSED

State defendants were correct, of course, in insisting

upon a formal order, for "[t]he filing of an opinion by

the District Court does not consitute the entry of an

—^Plaintiffs promptly filed objections to the Detroit

Board's proposed plans and are presently preparing their

own alternatives for submission to the district court.

6

order, judgment or decree from which an appeal can be taken."

Robinson v. Shelby County Board of Educ., No. 71-1825

(6th Cir., order of Nov. 8, 1971)(attached hereto as Appendix

H). And not even all orders may be appealed, for this Court

only has jurisdiction of appeals from "final decisions"

(28 U.S.C.A. §1291) and certain classes of "interlocutory"

orders (28 U.S.C.A. §1292(a)).6/

Clearly the order appealed from is not a "final

decision" within the meaning of 28 U.S.C.A. §1291.

It [the order] constituted only a

determination that plaintiffs were entitled

to relief, the nature and extent of which

would be the subject of subsequent judi

cial consideration by [the district court].

What remain[s] to be done [is] far more

than those ministerial duties the pendency

of which is not fatal to finality and

consequent appealability....

Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, 288 F .2d 600,

602 (2d Cir. 1961).

The only possible source for this Court's jurisdiction

over the instant appeals is 28 U.S.C.A. §1292 (a) (1). Taylor,

supra, 288 F.2d at 603. And for the reasons set forth in

Judge Friendly's opinion in Taylor, we submit that the Court

is without jurisdiction to hear the instant appeals.

6/Certain "certified" orders "not otherwise

appealable" may, with the permission of the court of

appeals, be appealed pursuant to the provisions of

28 U.S.C.A. §1292 (b). These provisions have not

been complied with in the instant case, however.

7

§1292 (a)(1), in pertinent part, gives this Court

jurisdiction of appeals from interlocutory orders "granting,

continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving injunctions....

The issue here is whether or not the district court has

entered an "order granting an injunction." We believe

that no such order has been entered in this case.

The order appealed from does but one thing: it

directs defendants to submit a report and plans for dese

gregation, and it permits other parties to file objections

and alternate plans. The order does not require reorgani

zation of the school system; it does not specify the nature

or extent of any reorganization that will be required; nor

does it establish a timetable for any reorganization that

will be required. At the pre-trial conference of October

4, 1971, Judge Roth made it clear that he "had no precon

ceived notion about what the Board of Education should do

in the way of desegregating its schools nor the outlines

of a proposed metropolitan plan. The options are completely

open." (App. B at 27).

To be sure, the ...[order] used the word

"ordered" with respect to the filing of a

plan, just as courts often "order" or

"direct" parties to file briefs, findings

and other papers. Normally this does not

mean that the court will hold in contempt

a party that does not do this....[But] even

if the order was intended to carry contempt

sanctions ... a command that relates

merely to the taking of a step in a judicial

proceeding is not generally regarded as

a mandatory injunction, even when its

effect on the outcome is far greater

than here. For ... not every order con

taining words of command is a mandatory

injunction within [§1292 (a) (1)].

8

m •

Taylor, supra, 288 F.2d at 604. Nor may defendants contend

that they will suffer irreparable injury by complying with

7 /the order.—

[W]hile we understand defendants' dislike

of presenting a plan of desegregation and

attending hearings thereon that would be

unnecessary if the finding of liability

were ultimately to be annulled, and also

the possibly unwarranted expectations this

course may create, this is scarcely

injury at all in the legal sense and

surely not an irreparable one.

Id. at 603.

To allow defendants’ appeals at this juncture will

surely result in either (1) protracted piecemeal appellate

litigation, depriving the Court of the opportunity for fully

informed consideration of the important issues to be

presented, or (2) appellate litigation which may be

unnecessary as to all or some of the present parties

appellant and all or some of the issues to be presently

raised.§/

[T]o permit a hearing on relief to go

forward in the District Court at the very

time we are entertaining an appeal, with

the likelihood, if not indeed the certainty,

of a second appeal when a final decree is

entered by the District Court, would not

be conducive to the informed appellate

deliberation and the conclusion of this

controversy with speed consistent with order,

which the Supreme Court has directed and

ought to be the objective of all concerned.

In contrast, prompt dismissal of the appeal

as premature should permit an early con

clusion of the proceedings in the District

Court and result in a decree from which

defendants have a clear right of appeal,

and as to which they may then seek a stay

pending appeal if so advised. We — and

the Supreme Court, if the case should

See following page. _8/

9

— For example, ypon plaintiffs preliminary motion

to require the Detroit Board to implement its previously-

adopted voluntary plan (after this Court had declared the

impeding state statute unconstitutional, 433 F.2d 897),

defendants contended that they were not constitutionally

obligated to implement the plan. The district court, however,

ordered the Board to submit an updated version of that

plan and/or alternative plans. The Detroit Board, while

protesting this order, submitted two other plans which

they preferred, and the court approved and ordered imple

mented the Magnet School Plan (under which the Board is

presently operating) to which the Board had assigned first

priority. Plaintiffs challenged the plan approved as being

legally insufficient and appealed (438 F.2d 945), but none

of the defendants appealed. Pursuant to the order which

is the s*ubject of the instant appeal, the Detroit Board

defendants have submitted a variation of the Magnet Plan;

it is not too unrealistic to think that, should the

court approve the present submission of the Detroit

Board, these defendants would be content and no appeal

would be initiated. Furthermore, should the district

court decide that a metropolitan plan is not necessary

or is not proper, it is possible that the final decree

would not require anything of the State. Finally, it is

possible that, should the district court ultimately deem

a metropolitan plan to be necessary and proper, the

court might also require faculty reassignments, as a part

of any such plan, thereby eliminating the grounds for

plaintiffs' present complaint. This is not to say that

this important litigation will never be before this

Court for review, but it is quite possible that the case

could come to this Court in an entirely different

posture and with a different alignment of parties than

is contemplated by the present appeals.

10

go there — can then consider the decision

of the District Court, not in pieces but

as a whole, not as an abstract declara

tion inviting the contest of one theory

against another, but in the concrete.

Taylor, supra, 288 F.2d at 605. The Taylor court refers,

critically, to an unreported order of this Court denying

a motion to dismiss in an early appeal in Mapp v. Board of

Educ. of Chattanooga. Judge Friendly's criticism is based,

in part, on the developments in Mapp after the motion to

dismiss the appeal was denied (288 F.2d at 605):

[Mjoreover, the subsequent proceedings

in the Mapp case, where the District

Court has already rejected the plan directed

to be filed and required the submission of

a new one, with a second appeal taken from

that order although the first appeal has not

yet been heard, indicate to us the unwisdom

of following that decision even if we

deemed ourselves free to do so.

A situation similar to that in Mapp occurred in

Robinson v. Shelby County Board of Educ., Nos. 20, 123,

20, 124 (6th Cir., order of June 25, 1970)(attached hereto

as Appendix I), where the school board had appealed from

a decision requiring the submission of new plans. While

the appeals were pending, however, the new plans were

received by the district court and a new order was entered

from which a new appeal had been taken. This Court dismissed

the pending appeals as being most. (App. I at 3).

In the instant case the Detroit Board defendants

have already submitted plans in accordance with the

order, and the State defendants will submit their plans

within two weeks. Thus, long before briefs are filed in

this appeal, the order from which defendants appeal will

11

have, "by its terms, expired." Robinson, supra, App. I

would rest here and rely upon Judge Friendly's

in Taylor but for a statement in 9 Moore's Federal

1(110.20 at p. 235 (2d Ed. 1970) , that "the weight

of authority would appear to be the other way.1110/

Two cases are cited for this proposition: Board of Public

Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton, 326 F.2d 616

(5th Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 377 U.S. 924 (1964);

Board of Educ. of Oklahoma City v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 158

(10th Cir. 1967). Braxton is distinguishable on its

at 3.—

We

reasoning

Practice,

9 /—'The State defendants have attempted to meet this

problem by stating in their Notice of Appeal (App. E)

that they appeal "from the order entered herein on November

5, 1971, which incorporates the findings of fact and con

clusions of law...." Saying it doesn't make it so, however,

and even if it did the order is clearly not a "final"

judgment; State defendants can only challenge what the

order requires them to do, which will shortly be mooted

(putting aside the question as to the appealability of

the order in the first instance).

10/But cf. 9 Moore' s Federal Practice, 1(110.20

at p. 233: ""it can be broadly stated that an order

incidental to a pending action that does not grant part

or all of the ultimate injunctive relief sought is not an

injunction, however mandatory or prohibitory its terms,

and indeed, notwithstanding the fact that it purports

to enjoin."

12

• •

facts,— / and Judge Tuttle specifically stated that the

decision in Braxton was not in conflict with the decision in

Taylor; "What was said here was quite different from the

limited statement made by Judge Kaufman in his decree

[in Taylor]." 326 F.2d at 619. In Dowell, supra, the

issue of appealability of the order was not raised. Even

so, the order appealed from in Dowell is more clearly

appealable than the order involved in Braxton, and is

completely distinguishable from the Taylor order. The

4

Dowell order was much more than a mere direction to submit

plans; the order encompassed the remedy for the constitutional

violations: "We conclude that the remedy employed by the

court below ... is appropriate...." 375 F.2d at 168

(emphasis added).

A recent case in the Fifth Circuit is instructive.

In Cianeros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dist.,

324 F. Supp. 599 (S.D. Tex. 1970), the district court

found that Mexican-Americans had been unlawfully separated

from whites in the public schools as a result of various

school board practices. The court ordered the school board

and plaintiffs to submit plans for remedying the constitutional

- -----/The order in Braxton with not only injunctive

language but with injunctive effect, enjoined the school

board: (1) from operating a segregated school system;

(2) from operating dual attendance patterns; (3) from

assigning pupils on the basis of race; (4) from expending

funds to support segregation; (5) from assigning teachers on

the basis of race. 326 F.2d at 617 n.l. Although the order

was not to be effective until plans were submitted for the

implementation of the terms of the order, it is clear that

.the Braxton order, which defines the remedy, is much

different than the instant case where "[t]he options are

completely open." (App. B at 27).

13

violations, but the court also certified, pursuant to

28 U.S.C.A. §1292 (b), that there existed "A controlling

question of law as to which there is substantial ground for

differences of opinion...." 324 F. Supp. at 627. Upon

application by the school board to the Fifth Circuit

pursuant to §1292 (b), the Court denied leave to appeal

from the district court's interlocutory order. Cisneros v.

Corpus Christi Independent School Dist., Misc. No. 1746

(5th Cir. July 10 , 1970) (order attached hereto as Appendix

J). The district court subsequently ordered implementation

of a plan of desegregation, and the school board's appeal

of the whole case is now pending. See 448 F.2d 1392, 1394-95

(5th Cir. 1971) (Bell, J., dissenting from refusal hear

the appeal en banc).

We doubt that Moore's is correct as to the"weight

of authority"; in any event, we submit that the weight

of the reasoning compells dismissal of the appeals herein.

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs

respectfully pray that, after the time allowed for

responses to this motion has elapsed, the Court enter an

order dismissing the appeals herein.

14