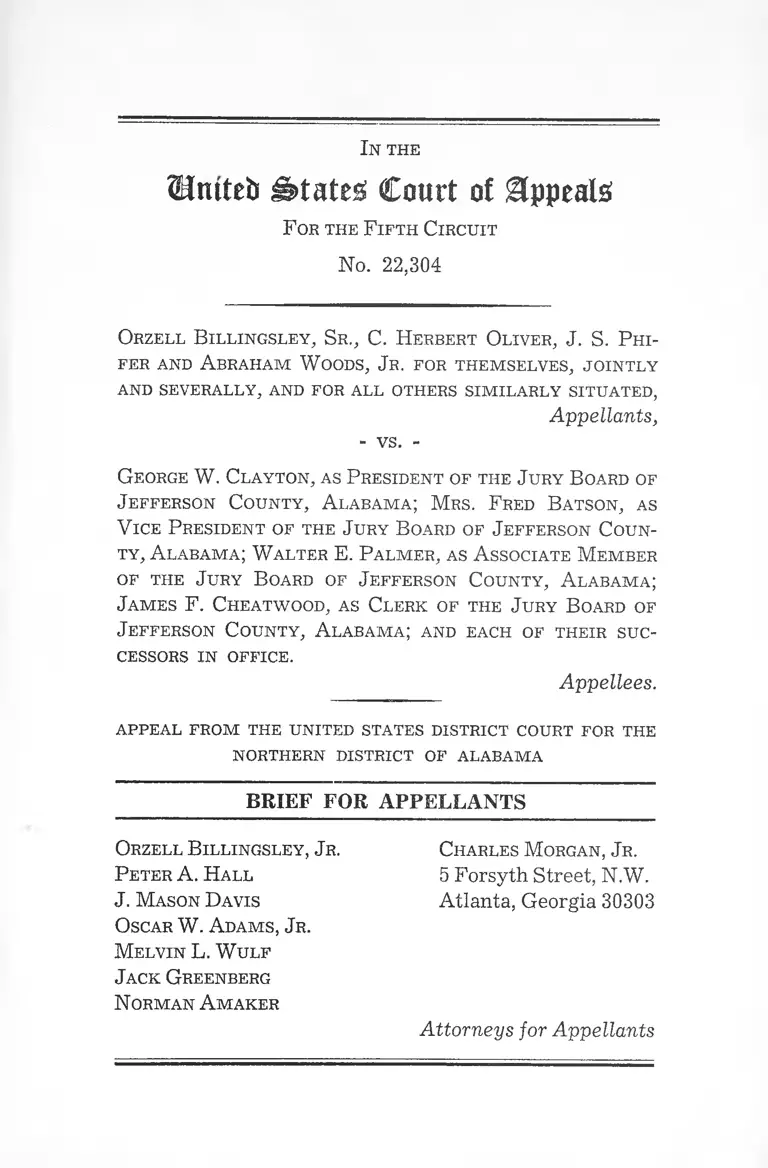

Billingsley v. Clayton Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Billingsley v. Clayton Brief for Appellants, 1965. 1aefbfde-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d9264cbb-1e7e-4649-b3cd-c3b25c281bd6/billingsley-v-clayton-brief-for-appellants. Accessed January 24, 2026.

Copied!

In THE

H m te b S ta te s ’ C o u r t of appeals;

F o r t h e F i f t h C i r c u i t

No. 22,304

O r z e l l B i l l i n g s l e y , Sr., C. H e r b e r t O l iv e r , J. S. P h i

f e r a n d A b r a h a m W o o d s , Jr. f o r t h e m s e l v e s , j o i n t l y

AND SEVERALLY, AND FOR ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED,

Appellants,

- vs. -

G e o r g e W . C l a y t o n , a s P r e s i d e n t o f t h e J u r y B o a r d o f

J e f f e r s o n C o u n t y , A l a b a m a ; M r s . F r e d B a t s o n , a s

V i c e P r e s i d e n t o f t h e J u r y B o a r d o f J e f f e r s o n C o u n

t y , A l a b a m a ; W a l t e r E . P a l m e r , a s A s s o c ia t e M e m b e r

o f t h e J u r y B o a r d o f J e f f e r s o n C o u n t y , A l a b a m a ;

J a m e s F . C h e a t w o o d , a s C l e r k o f t h e J u r y B o a r d o f

J e f f e r s o n C o u n t y , A l a b a m a ; a n d e a c h o f t h e i r s u c

c e s s o r s IN OFFICE.

Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r ic t c o u r t f o r t h e

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

O r z e l l B i l l i n g s l e y , J r .

P e t e r A . H a l l

J . M a s o n D a v is

O s c a r W . A d a m s , J r .

M e l v i n L. W u l f

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

N o r m a n A m a k e r

C h a r l e s M o r g a n , J r .

5 Forsyth Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Attorneys for Appellants

1

I N D E X

PAGE

STATEMENT.............................................................. 1

The Proceedings...................................................... 1

The Jury Board and its Selection Techniques . . . . 3

The Random Procedures Followed in the Selection

of Names of Jurors from the Jury Box in Jeffer

son County .......................................................... 7

The Results: Grand J u r ie s ..................................... 9

The Results: Petit J u r ie s ....................................... 12

The Population........................................................ 13

SPECIFICATIONS OF ERRO R................................. 14

ARGUMENT ................................................................ 15

I. A Survey or Canvass or Sample System of Juror

Name Selection Is not only a Proper but Is also

a Preferred Technique which Should end the

Systematic Exclusion of Racial or other Groups

from Jury R o lls ..................................................... 15

The Problem of the Selection of Sources of

Names .......................................................... 15

The Survey or Canvass or Sample System

Can Provide an Accurate Cross-section . . . . 19

Discretionary Power in the Hands of Jury Of

ficials Must Be Elim inated......................... 20

XX

Literary Digest Juries Do Not March in Step

with American Life — or L a w .................. 23

The Results of Discrimination in Juror Name

Selection ...................................................... 29

Segregated Ju s tice .......................................... 31

Remedies for the Systematic Exclusion of Ne

groes from Jury Service............................. 34

The Negro Revolution and All White Courts 38

II. The Evidence Clearly Shows that the Jury

Board Systematically Excluded the Names of

Negroes from Jury Rolls in Both the Birming

ham and Bessemer D ivisions............................. 45

Plaintiffs Proved a Prima Facie C a se ......... 45

The Laws of Probability Demonstrate the

Likelihood of Exclusion............................... 51

III. Conclusion............................................................ 54

Certificate of Service..................................................... 57

APPENDIX A .............................................................. 58

The Opinion and Order of the court below, June

7, 1962 .................................................................... 58

The Order on Pretrial Hearing, July 20, 1964 . . . . 66

Additional Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law in the Court below, December 2, 1964 . . . . 68

Ill

APPENDIX B ............................................................ 71

Statutes Relating to the Operation of the Jury

System in Jefferson County, A labam a............ 71

APPENDIX C

Maxwell, N.A., “The Liuzzo Case,” The Wall St.

Jrnl., May 4, 1965 ................................................ 83

T a b l e o f C a s e s

Allen v. State, 110 Ga. App. 56, 137 S.E. 2d 711

(1964) ...................................................................... 34

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U.S. 773 (1964) . . . . 34

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559, (1953) ................. 22

Bailey v. Wharton, Civil Action No. 3674 (j)

(D.C.S.D. Miss.) .................................................... 36

Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 (1 9 4 6 )........ 19

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) .............................................. 39

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S. 110 (1882) .................... 34

Brown v. Rutter, 139 F. Supp. 679 (D.C.W.D. Ky.,

1956) ........................................................................ 35

Cameron v. Johnson, . . . U.S. . . ., 33 L. Week 3395

(1965) ...................................................................... 42

Clarence C. Walker Civic League v. Board of Public

Instruction, 154 F.2d 726 (5th Cir., 1946)............. 50

Cobb v. Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95 (5th Cir., 1964) . . . . 46

IV

Cox v. Louisiana, . . . U.S. . ., 33 L. Week 4105

(1965) .................................................... 40, 41, 42, 43

Cobb v. Montgomery Library Board, 207 F. Supp.

880 (M.D. Ala., 1962) ............................................ 46

Collins v. Walker, 335 F. 2417 ( ) cert. den. sub.

nom. Hansley v. Collins, No. 407, . U.S. . . .,

33 L. Week 3171 (1 9 6 4 )......................................... 22

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950) ................... 34, 36

Douglas v. California, 372, U.S. 353 (1963) 23

Draper v. Washington, 372 U.S. 487 ( ) 23

Eskridge v. Washington;'4i7^"U.S.-i^'(1958) 23

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) 34

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 ............................... 35

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368 (1963) ................... 24

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) 23

Glasser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 (1942) ......... 19

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) ..................... 23

Hale v. Kentucky, 303 U.S. 613 (1938) ................. 34

Harper v. Mississippi, . Miss. . . ., 171 So. 2d 129

(1965) ..................................................................... 34

Harvey v. Mississippi, 340 F. 2d 263 (1 9 6 5 )........... 23

Hazlewood v. Aycock, Civil Action No. . . (1965). 36

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954) 34, 28

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942) ........................... 34

Hollins v. Oklahoma, 295 U.S. 394 (1935) ........... 34

Jackson v. United States, No. 21,345 (5th Cir.) 37

V

Lane v. Brown, 372 U.S. 487 (1963) .......................

Louisiana v. United States, . . . U.S. . . ., 33 L. Week

4262 (1965) ............................................................

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370, (1880) .................

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 387 (1935) ............. 34,

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 464 (1947) .............

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 (1 9 3 9 ).................

Rabinowitz v. United States, No. 21,256 (5th Cir.) . .

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ...................

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) .....................

Repouille v. United States, 165 F. 2d 152 (2d Cir.,

1947) .......................................................................

Shepard v. Florida, 341 U.S. 50 (1950) .................

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ............. 19, 20,

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) . .

Swain v. Alabama, . . U.S. . . ., 33 L.Week 4231

(1965) ............................................................22, 46,

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1946) . .

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964) ...............

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (1964), cert. den.

379 U.S. 931 (1964) .................................... 31, 34,

United States v. Mississippi, . U.S. , 33 L.Week

4258 (1965) ............................................................

United States ex. rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d

71 (1959) cert, den., 361 U.S. 838

(1959) .............................................. 29, 31, 46, 50,

23

20

34

46

34

34

37

24

34

19

54

34

34

47

19

24

46

20

54

VI

United States ex. re. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 54

(5th Cir., 1962) cert, den., 372 U.S. 924

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. Sec. 1343 (3) ......................................... 2

42 U.S.C. Sec. 1981 .................................................2, 36

42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983 .......................................... 2, 35, 36

28 U.S.C. Sec. 2201 .................................................. 2, 36

Title 30, Sec. 72, Code of Ala., 1940 — 1958 ......... 9, 41

18 U.S.C. Sec. 243 ......................................... 35, 36, 50

42 U.S.C. Sec. 1985 ............. ...................................... 36

42 U.S.C. Sec. 1988 .................................................... 36

28 U.S.C. Sec. 1343 .................................................... 36

28 U.S.C. Sec. 1331 .................................................... 36

28 U.S.C. Sec. 1863 (c) ............................................ 36

28 U.S.C. Sec. 1651 .................................................... 36

28 U.S.C. Sec. 1861-71 .............................................. 36

Title III, Civil Rights Act of 1964 ...........................36-37

(H.R. 5640, pending)

18 U.S.C. 1507 ............................................................ 41

Title 62, Secs. 199-200, Code of Alabama (recomp.

1958 .......................................................................... 15

Title 30, Sec. 34-6, Code of Alabama (recomp 1958) 50

Title 30, Sec. 51, Code of Alabama (recomp. 1958) 50

Title 30, Sec. 48-9, Code of Alabama (recomp.

1958) 49, 50

V ll

Statutes (Cont’d.):

Title 30, Sec. 21, Code of Alabama (recomp. 1958) 49

Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 ......................... 25

Criminal Justice Act of 1964 ..................................... 23

Title 30, Sec. 38, Code of Ala. (recomp. 1958). . .51, 53

Title 30, Sec. 72, Code of Ala. (recomp. 1958)........ 51

Other Authorities:

Barksdale, The Use of Survey Research Findings as

Legal Evidence (1957) .......................................19, 21

Bulletin, Criminal Division (July 17, 1950) ......... 38

Bulletin, Criminal Division (June 8, 1953) ........... 38

Cash, Mind of the South (1941) ........................... 30, 31

Conference on Bail and Criminal Justice (1965) . . 23

(Proceedings and Interim Report of the)de Tocque-

ville, Journey to America (1960) ....................... 25

Frankel, The Alabama Lawyer, 1954-64: Has the

Official Organ Atrophied?, Col. L. Rev., (Nov.

1964) ....................................................................... 39

Fenton, In Your Opinion, (1960) .........................17, 21

Gallup and Rae, The Rules of Democracy,

(1940) .......................................16, 17, 18, 21, 52, 53

Ginzburg, 100 Years of Lynchings, (1962) ........... 29

Harrington, The Other America, (1 9 6 2 )........16, 24, 44

Jury Commissions for U.S. District Courts, Report

of the Committee on the Judiciary, No. 261 . . . . 38

The Jury System in the Federal Courts (1960) . . . 26

vm

Other Authorities (Coni’d.):

Justice, (U.S. Civil Rights Commission Reports,

1961) ................................................ 24, 25, 35, 37, 38

Kennedy, Law and the Courts, in The Polls and Pub

lic Opinion, Meier and Saunders, ed. (1949) .19, 23

Lester, Justice in the American South (1965) .32, 35

Maxwell, The Liuzzo Case, The Wall Street Journal,

(June 2, 1965) .................................................... 29, 33

Morgan, A Time to Speak, (1964) ......................... 32

Morgan, Look, (June 29, 1965) ............................... 33

Nelson, “Jim Crow Justice,” Los Angeles Times,

(June 13-17, 1965) ...................................... 15, 33, 35

Olshausen, Rich and Poor in Civil Procedure, 9 Sci

ence and Society 11 (1947) ................................. 24

Racial Discrimination in the Southern Federal

Courts, Southern Regional Council, (1965) ........ 32

Reed, Jury Deliberations, Voting and Voting Trends,

in The Southwestern Social Science Quarterly,

Vol. 45 No. 1 (1965) .......................................... 27, 28

Snead and Womack, Juries — Selection of Federal

Jurors — Exclusion of Economic Class (Mar.

1961) ....................................................................26, 27

Southern Regional Council Reports, May 1963, June

1964, July 14, 1964 ................................................ 33

Trebach, The Rationing of Justice; Constitutional

Rights and the Criminal Process (1964) ........... 24

Thoreau, Civil Disobedience, (1964) ..................... 44

United States Attorneys Bulletin, (January 6, 1956) 38

1960 U. S. Census, A labam a...................................... 14

I n t h e

U n tte b S ta te s C o u r t of appeals

F o r t h e F i f t h C i r c u i t

No. 22,304

Orzell Billingsley, Sr., C. Herbert Oliver, J. S. Phifer

and Abraham Woods, Jr. for themselves, jointly and

severally, and for all others similarly situated,

Appellants,

v.

George W. Clayton, as President of the Jury Board of

Jefferson County, Alabama; Mrs. Fred Batson, as Vice

President of the Jury Board of Jefferson County, Ala

bama; Walter E. Palmer, as Associate Member of the

Jury Board of Jefferson County, Alabama; James F.

Cheatwood, as Clerk of the Jury Board of Jefferson

County, Alabama; and each of their successors in office.

Appellees.

A PPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement

The proceedings.

On April 26, 1962, the plaintiffs,1 Negro residents of

the Birmingham and Bessemer Divisions of Jefferson

1 P laintiff B illingsley was also p a rty to a civil action then pending

in the C ircuit C ourt of the Tenth Judic ia l C ircuit (Jefferson County)

A labama. (R. 8-9)

2

County, Alabama, filed this class action. The defendants

are the members and clerk of the Jury Board of Jeffer

son County, Alabama ( “Jury Board” ). Jurisdiction was

invoked under Title 28 U.S.C. Section 1343 (3), Title 42

U.S.C. Sections 1981 and 1983 and the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments of the Constitution of the United

States. (R. 3,4-5)

The plaintiffs alleged that in the selection of names

for jury service the Jury Board used irregular and arbi

trary methods (contrary to the Constitution and laws

of Alabama and the United States) and systematical

ly excluded Negroes. (R. 8)

They sought a declaration pursuant to 28 U.S.C. Sec

tion 2201 that the Board’s policy, custom or usage in ex

cluding qualified Negroes from jury rolls and boxes is

in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments

of the Constitution of the United States. (R. 11.) They

also sought to enjoin the Jury Board “and all persons

in active concert and participation with them” from

failing or refusing to include in their selection the names

of Negroes otherwise qualified for Jury duty and from

using the names then used until the names of all quali

fied Negroes had been included (R. 11-2).

They sought a temporary restraining order (R. 10,

13-4) and preliminary (R. 10, 14-5) and permanent (R.

10) injunctions. A hearing was held on May 16, 1962

(R. 21), the court taking the matter under advisement

(R. 22).

On June 7, 1962, the Court declined — without preju

dice to a final decree — to issue a temporary restraining

order (R. 22) (See Opinion and Order, Appendix A,

p. 58).

3

On November 2, 1964, a final hearing was held (E.

34). The court entered judgment against the plaintiffs

on December 2, 1964 (R. 34-7 at 37) finding additional

facts and adopting the opinion previously filed on mo

tion for a temporary restraining order. (See Addition

al Findings of Facts and Conclusions of Law; Appen

dix A, p. 68)

Notice of appeal was filed on December 31, 1964

(R. 37-8).

The Jury Board and Its Selection Techniques.

The three members of the Jury Board:

a. Generally supervise the clerk (R. 150, 158, 60, 162,

186,187-9)

b. Know few or no Negroes (R. 151, 155-6, 191, 478)

c. The two male members are retired (R. 43,185)

d. Have suggested the names of white persons for

jury duty but have suggested the names of no

Negroes (R. 149-50,190-2)

e. Use the same juror selection techniques in the

Birmingham and Bessemer Divisions of Jefferson

County (R. 464-5)

The Jury Board relies on a house-to-house survey to

obtain the names of persons to be placed on jury rolls

(R. 82-3, 92,149,152-3, 278, 283-4, 371, 436.) Phone books,

the city directory, tax records, letters and visits to store-

owners and postmasters are also sometimes employed

(R. 45-48, 92-93, 337-9, 436). But primary reliance is

placed on the personal canvass of neighborhoods (R.

371). The voter registration list has never been used

(R. 91), tax rolls are relied upon rarely (R. 92) and the

city directory is used for corrections and spelling (R. 92).

4

Store people and postmasters are consulted in rural areas

(R. 304, 372).

The conduct of the survey is in the hands of the clerk

of the Jury Board. For a number of years J. F. Cheat-

wood served in this capacity (R. 82, 277, 435). He utilized

five to nine assistants to make the survey; each was a

white woman (R. 89-90, 293, 342-3). The Jury Board at

tempts by use of its techniques to obtain a fair repre

sentation — an economic and racial “cross-section” of

the population — for jury duty (R. 277, 284, 295, 311).

Despite this neither Mr. Cheatwood nor his assistant

(later his successor) (R. 367-8, 435) knew:

a. What percentage of a precinct was surveyed (R.

294)

b. The percentage of Negroes and whites on jury

lists (R. 85, 312)

c. The Negro communities he went to in Bessemer

(R. 376)

d. Negro people personally (R. 351, 381-2, 444)

e. The time spent in a Negro community visited

and remembered (R. 384)

f. The amount of time spent in Negro and white

neighborhoods (R. 442).

Although work sheets employed by canvassers do not

designate race (R. 290) they are not retained (R. 84).

Jury rolls prior to 1953 have been burned (R. 54-5, 86).

Present jury rolls contain no racial designations (R. 56-

7, 88, 447); nor do jury cards (R. 400, 406-7, 432-3).

Names contained on past jury lists are brought for

ward and used in succeeding lists (R. 55, 91). When a

person has actually served his name is removed for two

years (R. 90, 91).

5

The procurement of names of Negroes and whites

is handled differently. The methods employed are racial

ly determined. For example:

Letters. The Jury Board sent letters to Negroes

asking them to suggest names for inclusion on jury

lists but did not use letters to obtain the names of

whites (R. 57, 61, 303, 339, 436). There was diffi

culty obtaining Negro but not white names so let

ters were mailed only to Negroes (R. 295, 303). Of

88 letters mailed to Negroes only 9 replies were re

ceived (R. 322-3). The mailed form requests the pre

cinct number, the name, and residence and business

addresses, the occupation, place and date of birth of

the person suggested for jury duty (R. 337-8). This

technique was employed even though the Jury Board

knew it was not effective in providing the names of

Negroes (R. 340-2). At the first hearing (in 1962) a

Negro attorney stated that the next time a letter

came he’d send in 50,000 names, Mr. Cheatwood then

stating that he thought the letters would now be ef

fective (R. 346). At the time of the second hearing (in

1964) Negro attorneys were no longer on the mail

ing list (R. 437). No question of the legality or il

legality of attorneys suggesting names of prospective

jurors had been considered. And the practice of mail

ing letters to Negroes was continued — but not to

Negro lawyers (R. 436-7).

Volunteers. Thousands of whites have volun

teered for jury duty by coming to the Jury Board

office. Only 2 Negroes have done so (R. 349). White

groups assist the Jury Board but Negro professional

people have never been consulted nor has their as

sistance been sought (R. 347).

Publicity. Although articles appeared in the Bir-

6

mingham daily papers concerning jury service they

did not appear in Negro papers the Jury Board seek

ing no publicity there (R. 344).

The house-to-house survey. The white ladies em

ployed by the clerk to conduct the survey are ob

tained from the Personnel Board of Jefferson County

(R. 90). Thirteen to fifteen months are spent mak

ing the survey (R. 293).

There is more difficulty in obtaining the names

of Negroes than whites (R. 303, 305-9, 327-9). In

back alleys the canvasser may have to walk five or

six blocks to obtain two or three names (R. 328-329).

And Negroes are more suspicious and won’t come to

the door (R. 305-6). “When they refuse to answer the

question I say thank you and walk off,” said the

clerk. “I am not out there to argue with any of the

citizens” (R. 307). Fifty percent of the cards which

are left with white people are returned; less than 5

percent of those left with Negroes are returned (R.

327-8).

The white women employed by the Jury Board

are not allowed to go into “back alleys” the clerk

covering these areas himself (R. 343, 449-50). Indeed

the clerk and one other white man cover the Negro

areas (R. 343, 369-70, 380-1). None of the white ladies

go into the Negro community (R. 369-70). They don’t

go into rough areas, slum areas, where the homes

are in bad repair, the porches are falling off and

there are vicious dogs (R. 439, 440).

Despite the difficulty encountered in obtaining

the names of Negroes for jury service the entire staff

of the Jury Board is white (R. 375, 440). The clerk

did not know if Negro personnel would help (R.

7

339). And never tried to hire any Negro ladies (R.

442). Once a letter was sent to a Negro it was not

felt necessary to call on him personally since “that

would be a lot of trouble” and “costing double” (R.

59). Letters mailed to the Negro attorneys in this

case resulted in “nair” a name back (R. 61-2). In the

higher Negro income areas the personal survey is ef

fective but names do not come back from the letters

(R. 84, 308).

Work sheets are checked by the clerk (there is

no quota) some canvassers getting 30 to 40 names,

others 70 to 80 (R. 311). In a congested area the clerk

says he can cover 300 to 400 houses on foot per day

(R. 345). When no one is home he leaves cards for

the owner to fill out and return to the Jury Board

(R. 441).

The Jury Board employs the same policy in the

Birmingham and Bessemer Divisions of Jefferson

County (R. 441, 464-5).

The Random Procedures Followed in the Selection of

Names of Jurors from the Jury Box in Jefferson County,

Birmingham Division.

Cards on which are written the names of prospec

tive jurors are drawn from the big jury box (a heavy

steel box on rollers) (R. 111-2) by the presiding judge.

The cards are then taken to the Circuit Clerk’s office,

he draws up the list of jurors and gives it to the sheriff

who executes subpoenas requiring prospective jurors to

report to the jury assembly room on the 5th floor of

the court house (R. 203, 231). The clerk and the judge

who organizes the jury enter the jury assembly room

and the judge swears them in. The jury is then in the

charge of the jury room bailiff (R. 232).

8

Within an hour the cards containing the names of

jurors are placed in “a small black tin box” (R. 112,

232, 235) and a mimeographed list of the names of per

sons on the jury venire is drawn (R. 232).

No racial designations are on the cards or the list

and the names themselves are kept secret until 10:30

a.m. on Monday morning when they are made public

(R. 232-3).

At 9:00 a.m. on Mondays the docket is sounded, cases

announced ready are sent to the case clerk and readied

for trial (R. 233). The trial judge then sends to the jury

assembly room for the “tin little box” and draws the

names of 24 to 28 persons from it (R. 111-3). The partial

panel — persons whose names have been drawn — are

then brought to the courtroom where the lawyers pro

ceed to “strike” (R. 113).

Bessemer Division

The clerk sets the docket. Thirty days before trial

time the jury box is removed from the safe in the clerk’s

office and taken to the courtroom. In the presence of

the clerk the judge opens the box, shuffles the cards,

pulls out a “handful” and counts out 20. Then he re

shuffles the box. After selecting the names of 80 per

sons the venire is sent to the sheriff for service (R. 397-

9).

When grand juries are to be selected the clerk car

ries the box to the courtroom the judge drawing 35 to

40 names from the box. The clerk then prepares an al

phabetical list of the names drawn and delivers it to

the sheriff for service. On the following Monday morn

ing the prospective grand jurors arrive in court and 18

of them are selected for grand jury duty (R.R. 419-

20).

9

The Results — Grand Juries

Birmingham Division. Since 1947 (R. 211) the larg

est number of Negroes to appear on a grand jury which

consists of 18 persons is 3 (R. 214). On others 2 Negroes

have appeared. Almost all grand juries include at least 1

Negro (R. 213-5). Four grand juries are empaneled in

the Birmingham Division each year (R. 214, 216-7).

The names of grand jurors are selected at random

from the jury box (R. 215, 226).

Bessemer Division. On only one occasion (September

9,1957, when Caliph Washington was indicted) in the last

20 years has a Negro sat on a grand jury (R. 70, 357,

392-3, 415-6). The names of grand jurors are drawn from

the jury box at random (R. 418-22) at least 4 times a

year (Title 30, Sec. 72, Code of Alabama, 1940 Recomp.

1958). “The strange absence of Negroes from grand

jury service” is unexplained (R. 422).

The Results, Birmingham Division:

A. Petit Jurors in the Jury Assembly Room.

1. The testimony of attorneys practicing in Bir

mingham.

Roscoe B. Hogan, 12 years practice — 8 to 12

of the 90 to 105 persons in the jury assembly room are

Negroes (R. 167-8). Arthur D. Shores, 25 years practice

— 7 of the 65 to 70 persons in the jury assembly room

was the highest number he had ever seen (R. 128-9).

David H. Hood, 14 years practice — often no Negroes in

the jury assembly room (R. 100-1) sometimes 1 or 2

(R. 100).

2. The testimony of officials.

J. Edgar Bowron, presiding judge and a Circuit

Judge for 27 years —■ the number of Negroes varies but

10

there were 8 one week 2 or 3 another (R. 240). Of 240

persons called for jury duty 8 or .10 may be Negroes

(R. 242-3). Julian Swift, Circuit Clerk, 14 years —

'‘imagines” 10% or 12% of persons in the jury assembly

room are Negroes (R. 210). Nine of 112 or 105 (R.

206) who appeared during the week he testified were

Negroes (R. 205). He recalfe as many as 18 to 20 Ne

groes reported for jury duty once but never as many as

30% (R. 209) and on further examination fixed 10 to

12% as the percentage of Negroes in the room (R. 210).

3. The testimony of Negroes called for jury duty.

Frederick L. Ellis — 10 Negroes in room with

him. There were 35 or 40 there he “imagined.” The

room was full (R. 246). Hugh L. Lemon — 3 of 100

were Negroes (R. 122). Louis J. Willie — 10 of more

than 100 were Negroes (R. 139).

B. Partial panels called from the jury assembly room.

1. The testimony of attorneys practicing in Bir

mingham.

Jerry O. Lor ant, 12 years practice — no

judgment of largest number of Negroes seen on a par

tial panel (R. 76). Negroes had served on juries in cases

he’d tried (R. 77), but he couldn’t remember how often

or the name of a case (a criminal case) or the judge

before whom it was tried (R. 78-80). David H. Hood —

14 years practice — no Negroes on panels prior to 1961

but he has seen 1 or 2 since then (R. 102-3). James G.

Adams, 41 years practice — “occasionally, not often, but

occasionally” he has seen Negroes on a partial panel

apparently in the criminal courts (R. 115). He has seen

3 Negroes on a partial panel of 27 to 28 men but in the

preceding year he saw no more than 1 or 2 Negroes

(R. 117-9). Arthur D. Shores, 25 years practice — on 1

11

or 2 occasions he observed 1 or 2 Negroes on partial

panels (R. 129). Matt Murphy, 15 years practice —

once saw 6 to 8 Negroes on a partial panel (R. 144-5)

but since 1960 he has seen no more than 3 or 4 on a

panel of 40 and this in a criminal case (R. 145-7). John

H. Lair, 10 years practice — once saw 7 Negroes on a

panel but doesn’t remember the case and may have been

in error (R. 220).

2. The testimony of officials.

Emmett Perry, Circuit Solicitor since 1947 —

he had seen Negroes on partial panels but never counted

the number of them (R. 212-3). Wallace Gibson, Circuit

Judge criminal courts since 1957 — once saw a partial

panel of 24 jurors with 6 Negroes none of whom ac

tually served (R. 223). Prior to this one occasion the

largest number of Negroes in a partial panel was 2 or

3 (R. 224-5). J. Edgar Bowron, presiding judge and a

Circuit Judge for 27 years — Negroes are on partial

panels fewer times than they are not (R. 239) and infre

quently have served on juries in his court. No more

than 1 Negro has served on a petit jury at one time

(R. 238). He often handles excuses from jury duty but

there is no evidence that a higher percentage of Ne

groes than whites sought excuses (R. 240-4).

Negroes who are called for jury service seldom leave

the jury assembly room and when they do are almost

always struck and rarely serve (R. 125, 140, 174, 197,

228-9, 245, 247-54, 255-7). In the criminal courts agree

ments not to include Negroes on partial panels called

from the jury room have been abolished (R. 225). But

exclusionary agreements exist in the civil courts (R. 115,

169-70, 198-9, 234, 237) although this was disputed (R.

220-1).

12

The Results: Bessemer Division

A. Petit Juries

1. The testimony of attorneys practicing in Bes

semer.

H. P. Lipscomb, Jr., more than 40 years prac

tice — 3 Negroes out of “quite a number” of whites;

4 or 5 juries were empaneled for the Washington case

in 1957. Prior to 1962 this was the only time any

Negroes were empaneled (R. 69-70). During the succeed

ing 2 years he noted as many as 3 or 4 Negroes on the

venire of 50 to 60 persons (R. 360-4). David H. Hood, 14

years practice — no observation of Negroes on the panel

or venire (R. 97). William C. Smithson, 45 years prac

tice — no Negroes seen on a jury panel (R. 109). Hugh

McEniry, 52 years practice — last saw a Negro juror

serve in the Caliph Washington case (R. 180-1). Edward

Saunders, 32 years practice — no Negroes on a panel in

5 years (R. 183-5).

2. The testimony of officials.

Edward L. Ball, Jr., Circuit Judge and at

torney for 23 years — cannot recall a civil or criminal

case when Negroes actually served on a petit jury (R.

390-1). Since 1957, 4 Negroes usually appear on a venire

of 37 to 38 people, one week it was 5 Negroes in a venire

of 48, and once there were 7 or 8 Negroes on a venire

of 42 (R. 391-2). There have never been as many Ne

groes as whites on a venire (R. 410). Although there

are no racial markings on jury cards he knows by ad

dresses which communities are predominantly or all

white and which are Negro (R. 401-3). Elmore McAdory,

Deputy Circuit Clerk and Registrar for 12 years — no

Negroes have served on a petit jury in 20 years (R. 415).

13

Negroes first began to appear on the venire in 1953

(R. 424). Although he once observed 9 Negroes on a

venire and once 8 he could recall no details of this

except it happened in 1964 (R. 430-1).

Several Negroes testified as to their own qualifica

tions and the failure of the state to call them or their as

sociates, neighbors, kinsmen and church members for

jury service (R. 261-76). Indeed the clerk of the Jury

Board had no opinion on whether “the incidence of quali

fication for conviction of crime was higher among

white than colored, or colored than white” when the

Court asked (R. 444). There was no testimony concern

ing Negro or white crime or illiteracy rates (R. 464).

There is some vague testimony concerning more whites

being qualified and more colored citizens asking to be ex

cused or it “could be the sheriff didn’t serve Negroes”

(see generally R. 467-74). But the presiding judge of the

Tenth Judicial Circuit (Birmingham Division) did not

testify that he excused more or a higher percentage of

Negroes than whites (R. 240-4). Nor did the Deputy

Clerk (Bessemer Division) know about this (R. 422).

There was no testimony regarding the rates of lit

eracy, householding, freeholding, honesty, intelligence,

character, habitual drunkeness, disease or physical weak

ness of either Negroes or whites.

The population: Jefferson County as a whole.

There are 120,205 (70%) white and 51,961 (30%)

non-white males over 21 years of age in Jefferson County

(R. 301). Of these 13,796 white and 7,097 non-white males

are over 65 years of age and, consequently, ineligible

for jury service (R. 302-3). Thus the total number of

whites eligible for jury service in Jefferson County is

14

106,409 (70%). The total number of eligible non-whites,

44,864 (30%) (R. 302-3; see 1960 U.S. Census, Alabama

p. 2-83).

The total number of names listed on jury rolls is ap

proximately 52,000 (R. 284).

Bessemer Division. The Bessemer Division consists

of Precincts 53, 33 and a small part of 9 (R. 364-5, 377-

9). There are 33,989 males over 21 years of age. Of

these 20,449 are white, 13,540 are non-white. Of the

29,900 males in the 21 to 65 age bracket 18,313 (61%)

are white, 11,587 (39%) are non-white. (See Exhibit 1:

also R. 376-9).

The total number of names listed on jury rolls in

1961-63 was 8,892 (R.379).

Birmingham Division. There are 121,373 males eligi

ble for jury service in the Birmingham Division. Of

these 88,096 (73%) are white, 33,277 (27%) are non

white.

The total number (approximate) of names listed on

jury rolls is 43,108.

Specifications of Error

1. The District Court erred in ruling that the plain

tiffs did not prove that the Jury Board systematically

excluded from jury rolls the names of Negroes in the

Birmingham and Bessemer Divisions of Jefferson Coun

ty, Alabama in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States.

2. The District Court erred in refusing to enjoin the

Jury Board from discriminating against the plaintiffs

and others similarly situated in the selection of names

of persons eligible for jury service, in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States.

15

Argument

X A SURVEY OR CANVASS OR SAMPLE SYSTEM

OF JUROR NAME SELECTION IS NOT ONLY A

PROPER BUT IS ALSO A PREFERRED TECHNIQUE

WHICH SHOULD END THE SYSTEMATIC EXCLU

SION OF RACIAL OR OTHER GROUPS FROM JURY

ROLLS.

The problem of the selection of sources of names.

The survey or canvass or sample system of juror

name selection2 offers hope for federal and state

courts across the nation. Selection techniques now dif

fer from state to state and within states from court to

court. The federal system differs from the state sys

tem. Qualifications differ from state to state. Federal

qualifications differ from state qualifications. Indeed

former Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall re

cently noted: “A Justice Department survey in 1961

showed that the 92 federal district courts had 92 dif

ferent systems of selecting juries.” 3

One jury commissioner’s telephone book is another’s

city directory. A third may try voter registration lists.

The Junior Chamber of Commerce, church membership

lists (regardless of the First Amendment), lists of school

teachers, American Legion posts or labor unions, lists

of industrialists and lists of automobile owners, lists of

2 A lthough th e Jefferson County ju ro r nam e selection system is

sometim es term ed a canvass (See T itle 62, Section 199, Code of A la

bam a; Recomp. 1958) it is, in reality , a sam ple selection system

upon the only “. . . six per cent of th e population of the county . . .”

th e Ju ry B oard’s responsibility is discharged. (See T itle 62, Section

200, Code of A labam a; Recomp. 1958). (R. 285) The Ju ry B oard does

not claim to canvass every dw elling in th e county.

8 Nelson, Jack. Jim Crow Justice, Los Angeles Times, Thursday,

Ju n e 16, 1965.

16

householders or PTA members or registered voters or

real property tax payers —* all are used. The dearth of

truly cross-sectional lists is the plague of jury commis

sioners. Some rely, especially in the federal courts, on

the “key-man system,” key men suggesting their friends

and associates for jury duty. One clear light shines

through the forest of lists 4 — the United States in al

most every one of its courts tries its citizens before Lit

erary Digest juries.5

The inability of the Literary Digest list system and,

for that matter, any other list system to obtain a eross-

4 “A sm all point: A m erica has a self-im age of itself as a nation of

jo iners and doers. There are social clubs, charities, com m unity drives,

and the like. Churches have always played an im portan t social role,

often m ark ing off the status of individuals. And yet the en tire s truc

tu re is a phenom enon of the m iddle class. Some tim e ago, a study in

F ranklin , Indiana, reported th a t the percentage of people in the bo t

tom class who w ere w ithout affiliations of any kind was eight tim es

as g reat as th e percentage in the high income class. The poor person

who m ight w an t to jo in an organization is afraid. Because he or she

w ill have less education, less money, less com petence to articulate

ideas th an anyone else in the group they stay aw ay.” H arrington,

Michael, T he O ther Am erica, P enguin Books, Inc., Baltim ore, 1964,

p. 130.

5 T he L iterary D igest by 1895 had collected lists of nam es of m id

dle and upper economic class persons who m ight subscribe to the

m agazine and purchase its advertised products. In 1895, it had 350,000

names, by 1900, 685,000. In 1916 it entered the polling field. In 1920 it

m ailed 11,000,000 ballots to residen tia l te lephone subscribers seeking

th e ir preferences as to p residential nominees. It conducted polls on

national prohibition and o ther m atte rs like th e M ellon tax reduction

proposal.

P rio r to the 1928 P residen tial election it m ailed 18,000,000 ballots

and in 1932 20,000,000 ballots. I t correctly predicted the w inner each

year.

Jam es J. F arley considered the poll “conclusive evidence.” O thers

hailed it as “uncanny,” “infallible,” “am azingly accurate.” Before it

began its 1936 operations it was said, “the Digest poll is still the Bible

of m illions.” To pred ic t the Roosevelt-Landon race it m ailed 10,000,000

ballots to its list of te lephone subscribers and autom obile owners.

One of every four ballots was retu rned . (Gallup, George and Rae,

S. F., The Pulse o f Democracy, Simon and Shuster, New York, 1940.

pp. 39-43)

17

section of the population, was demonstrated in 1936.

Prior to the Digest’s mailing of its ballots in 1936,

George Gallup’s American Institute of Public Opinion

made preliminary studies and discovered that although

Landon would receive 59% of the votes of telephone

subscribers and 56% of the votes of automobile own

ers, he would receive only 18% of the votes of those on

relief. Following this the Institute began in earnest a

prediction not merely of the coming election results

but also of the coming results of the Digest poll. It pre

dicted that the Digest would predict 56% for Landon,

and 44% for Roosevelt. The Institute also predicted

that the Digest would be wrong in 1936. And it predict

ed the Digest’s margin of error within 1%. The editor

of the Digest retorted: “Our fine statistical friend . . .

should be advised that the Digest would carry on with

those old fashioned methods that have produced correct

forecasts exactly one hundred percent of the time.” 6

Messrs. Gallup and Rae point out that in 1936 class

alignments were drawn with a firmness; economics di

vided America. The large sample used was of no help

since the basis of sample selection was itself faulty: per

sons in upper income brackets tended to respond to

mail canvasses in greater proportion than the poor; the

rich were so angry with Roosevelt they were moved to

protest; and the entire sample was biased to older per

sons. More than this the Digest system failed to capture

changes in sentiment near the end of the campaign

— an error Mr. Gallup was to make 12 years later.7

e Ibid,., p. 47.

'l B u t it should be noted th a t although G allup’s predictions in 1936

w ere correct and, coupled w ith the resu lts of other scientific surveys

opened the field of scientific polling, his e rro r of 6.8% percentage

points was g rea ter than the 4.8 percentage point e rro r m ade in 1948.

Pollsters today would be ru ined by an erro r of 6.8 percentage points.

Fenton, J. M., In Y our Opinion, L ittle Brown and Company, Boston,

18

Thus in 1936 when the cleavage of economic class

was as pronounced as the racial cleavage in the South

the Literary Digest failed spectacularly — as spectacu

larly as Mr. Roosevelt succeeded with 60.7% of the

votes. The use of lists — and no welfare, relief, or other

lists of the visible or invisible poor were then used by

the Digest or are now used by the courts — led to the

Digest’s colossal error. And the death of the magazine.

The jury system in America faces the same problem of

error, the same continuing trial, of “those old fashioned

methods that have” — fictionally — “produced correct

forecasts exactly one hundred percent of the time.”

“One fundamental lesson became clear in the 1936

election: the heart of the problem of obtaining an ac

curate measure of public opinion lay in the cross section,

and no mere accumulation of ballots could hope to elimi

nate the error that sprang from a biased sample.” 8

Indeed, “less than one tenth of one percent of The

Literary Digest’s 19 point error in 1936 could reason

ably be due to the size of the sample. One tenth of one

percent is the range of error which can be expected with

practical certainty in a sample of 2,227,500 cases . . .

where opinion divides in the ratio of 55 to 45. The Di

gest’s final report, showing Landon with 57 percent to

43 percent for Roosevelt, was based on 2,376,523 ballots.

Virtually all the Digest’s error was undoubtedly due to

two other factors which determine accuracy in this field

of opinion research — cross section and timing.” 9

I960, p. 9. In 1948 the public opinion polls w en t w rong because they

stopped in terview ing too early (October 15) and did not catch last

m inute trends, th e re was an “unusually high proportion of undecided

vo ters” then and “the problem of vo ter tu rnou t was particu larly

acute.” The 1948 errors have been rem edied in la te r surveys. (Ibid.,

pp. 71-3).

8 G allup and Rae, op. cit., pp. 54-5, emphasis supplied.

9 Ibid., p. 71.

19

The Survey or Canvass or Sample System Can Provide

an Accurate Cross-Section.

Juries are required to be drawn from a cross-section

of the eligible population.10 The jury decides ultimate

questions. Prior to its decision the jury is intensively ed

ucated with facts and law. But the jury’s verdict can

be accurate only to the degree that the jury itself is

not drawn from a biased source. A jury venire drawn at

random, is itself a sample of the names in the jury box.

To the degree that the names in the box represent a

cross-section of the population the jury’s verdict can be

unbiased. To the extent that the names of jurors are not

drawn from a cross-section of the population the venire

is as biased as the verdict of the jury is inclined to be.

Survey results are themselves used “as evidence in

numerous cases and in various areas of litigation.” 11

10 Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 (1946); see also Glas-

ser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 (1942). “The system atic and in ten

tional exclusion . . . of a racial group, Sm ith v. Texas, 311 U.S, 128

. . . deprives the ju ry system of the broad base it was designed by

Congress to have in our dem ocratic society. I t is a departu re from the

sta tu to ry scheme. . . . The in ju ry is not lim ited to the defendant—

there is in ju ry to th e ju ry system, law as an institution, to the com

m unity a t large, and to the dem ocratic ideal reflected in th e processes

of our courts.” Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187, 195 (1946).

11 “Most frequen tly in trade-m ark , trade-nam e, and un fair com pe

tition cases.” They are also em ployed in false and m isleading advertis

ing cases and in cases involving “adulterated and m isbranded foods,

drugs and cosmetics; design pa ten t infringem ent; and changes of

venue.” Sam pling techniques have been employed “in an ti- tru s t lit i

gation and public u tility ra te cases.” Barksdale, H. C., The Use of

S u rvey Research Findings as Legal Evidence, P rin te rs’ Ink Books,

P leasantville, N.Y., 1957, p. 141.

A lthough Judge Learned Hand once reg retted th a t the courts have

no Gallup poll to aid them in defining the “good m oral character”

dem anded of a candidate fo r naturalization (Repouille v. United

States, 165 F.2d 152, 153 (2nd circ. 1947)), Mr. Gallup had, in fact,

conducted a survey on the problem w ith w hich the court was con

cerned (Kennedy, F. R., L aw and the Courts, a C hapter in The Polls

and Public Opinion, edited by M eier and Saunders, H. W., H enry Holt

and Company, N ew York, 1949, p. 104, note 41.) The conduct of su r

veys by an agent of the court has been suggested (Ibid., p. 106).

20

The introduction into evidence of survey results

may be debatable. Questions arise regarding the relia

bility of the survey, the partisanship of the research

er, the admissibility of hearsay evidence and the prob

lem of whether to judicially notice survey results. But

the use of a survey system of jury selection poses only

problems relating to the administration of the survey

itself.

Discretionary Power in the Hands of Jury Officials

Must be Eliminated.

President Johnson in his address to the joint session

of Congress Monday, March 15,1965, stated:

“Experience has clearly shown that the existing proc-

cess of law cannot overcome systematic and ingeni

ous discrimination. No law we now have on the

books can insure the right to vote when local offi

cials are determined to deny it.”

The same may be said regarding the right to serve

on juries. But techniques may be established in a sur

vey system of jury selection to provide checks against a

racially exclusionary administration. Discretion is an en

emy of the selection of names of a cross-section of the

population.12 As Mr. Justice Black has said. .. by rea

son of the wide discretion permissible in the various

steps of the plan, it is equally capable of being applied

in such a manner as practically to proscribe any group

thought by the law’s administrators to be undesira

ble.” 13

12 Condem nation of discretion in the hands of sta te voting officials

is a t the h ea rt of two recent decisions of the Suprem e Court. See

United States v. Mississippi, ——• U.S. ------, 33 L.W.4258 (1965) and

Louisiana v. United S ta te s ,------U .S .------- , 33 L.W.4262 (1965).

is Sm ith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940).

21

Survey research procedures may be adopted which

eliminate the discretion of the canvasser.14 “Within the

interviewing area, reporters work from prearranged se

lection codes in determining which people to question —

they are allowed no personal choice in the matter. The

total process is designed to minimize the bias which

might be introduced either by the home office statisti

cians or the interviewer in the field.

“It serves to remove from the interviewer’s hands

the decision on where to start interviewing and whom

to question, thus reducing the possibility of bias. If in

terviewers were given a choice in this matter, human

nature might inevitably work to turn up a sample of

front-porch sitters or, in rural areas, a representative

scattering of farms without fierce looking dogs.” 10

The elimination of discretion in the hands of jury

commissioners seems essential — especially since such

discretion no longer has any value. In urban unlike rural

areas no jury commissioner’s circle of friends and knowl

edge of the community-at-large is sufficient to enable

him — by himself or with a clerk or another commis

sioner — to select the names of persons he knows for

jury service. Indeed in a pluralistic society with differ

ent cultures and subcultures a jury commissioner may

know no one in many segments of society to ask for

names. He may have no knowledge to enable him to

14 Barksdale, H. C., op. cit., pp. 17-35; see also Roper, B. W., Public

Opinion Surveys in Legal Proceedings, 51 A.B.A. Jm l. 44 (January ,

1965) com m enting on Sherm an, E. F., The Use of Public Opinion Polls

in Continuance and Venue Hearings, 50 A.B.A. Jrn l., p. 357, (A pril

1964). Fenton, J. M., op. cit., pp. 11-18. Gallup, George and Rae, S. F.,

op. cit., pp. 56-76.

15 Fenton, J. M., op. cit., p. 15. See also R. 439-40 regarding the

problem of vicious dogs.

22

find lists of persons.16 The survey system of jury selec

tion can eliminate this problem which has grown as

have our cities.

Criminal defendants ordinarily serve as challengers

of the systematic exclusion of a class from juries. But

the mass of names that must be examined and the ex

pense of that examination are often economically pro

hibitive. This difficulty of proof led the courts to sta

tistical determinations of exclusion and standards of a

prima facie case.17 Any survey system of jury exclu

sion should meet the constitutional requirement that the

procedure followed by jury commissioners — their

“course of conduct” — “not operate to discriminate in

the selection of jurors on racial grounds.” 18

Sampling techniques employed by pollsters rely on

the laws of probability. And mathematical formulae ap

plied to random drawings from jury boxes can prove

with the smallest range of error — an infinitesimal

range when compared with other techniques of proof

— not only whether or not there has been systematic

exclusion from jury rolls but also what group has been

excluded and the extent of the exclusion. This tech

nique is used later to show the extent of Negro exclu

sion in Jefferson County.

The Jury Board of Jefferson County, Alabama, em-

16 Indeed, is i t constitutionally perm issible to seek out lists of names

of persons in racial o r o ther groups to include on a “general ven ire

lis t?” A lthough Judge Rives reserved ru ling on th is question in

Collins v. W alker, 335 F.2d 417 (1964) cert. den. sub. nom. Hanchey v.

Collins, No. 407, ------ U.S. ------ , 33 L. W eek 3171 (1964) Judge Jones

sta ted th a t Negroes “perhaps” m ust be included but, apparently , not

purposefully. Cf. Sw ain v. Alabam a, ------ U.S. ------ , 33 L. W eek 423

(1965) and cases th e re cited.

17 See V.S. ex. rel. Seals v. W iman, 304 F.2d 53 (5th Cir. 1962).

18 A ve ry v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559, 561 (1953).

23

ploys the proper technique of juror selection; the fact

that it did not correctly use i t 19 should not detract

from the basic soundness of the method itself, one that

can and should be used in state and federal courts across

the land. “The courts’ machinery and processes for dis

covering truth are time-tested but they are not per

fect.” And most of our judges recognize the value of

availing themselves of all modern scientific aids in their

search for truth as soon as their reliability can be es

tablished. If the application of opinion research method

ology can contribute to the discovery of truth in the

courts of justice, it can serve no worthier purpose.” 20

Literary Digest juries do not march in step with the

trends of American life or law.

In the South the problem of jury selection is com

pounded by the problems of poverty and race.

The United States seeks to abolish class distinction

in court. Although many legal problems remain for the

poor advances have been made.21

As the federal government moved to protect the

rights of the oppressed — whether defenseless because

19 See statem ent pp. 3-7, infra.

20 Kennedy, F. R., op. cit., p. 108.

21 G riffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1958)_.v0.he righ t of the poor to a

free transc rip t); Eskridge v. W a s h in g tc A f^ I U.S. 214 (1958) (m ade

Griffin re troac tive); Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963) (the

righ t of the poor to counsel on appeal); Lane v. Brown, 372 U.S. 477

(1963) (the righ t of poor to free transcrip t for post-conviction rem

edy); Gideon v. W ainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) (the righ t of the poor

to counsel in non-capital felony cases); H arvey v. Mississippi, 340 F.2d

263 (1965) (the righ t of the poor to counsel in m isdem eanor cases);

See also National Conference on Bail and Criminal Justice, Proceedings

and In terim Report of the, W ashington, D.C. (1965); C rim inal Justice

A ct of 1964.

24

of poverty 22 or race or both—the Supreme Court moved

to insure democracy on the state level. It declared the

equal right of every man to an equal vote.23

But the exclusion of the poor and Negroes from the

administration of justice continues. And it continues in

those very institutions which are intended to protect

the rights of the minority, the weak and oppressed

against the demands of the majority, the wealthy and

powerful. As the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights has

said:

“The victims of lawlessness in law enforcement are

usually those whose economic and social status af

ford little or no protective armour — the poor and

racial minorities. Members of minority races, of

course, are often prevented by discrimination in gen

eral from being anything but poor. So, while almost

every case of unlawful official violence or discrimina

tion studied by the Commission involved Negro vic

tims, it was not always clear whether the victim

suffered because of his race or because of his lowly

economic status. Indeed, racially patterned miscon

duct and that directed against persons because they

are poor and powerless are often indistinguishable.

However, brutality of both types is usually a de

privation of equal protection of the laws and of di

rect concern to the Commission.” 24

22 See Trebach, A. S., The Rationing of Justice; Constitutional

Rights and the Criminal Process, R utgers Univ. Press, New B runs

wick, N.J., 1964. F or a sem inal trea tm en t see Olshausen, George,

Rich and Poor in Civil Procedure, 11 Science and Society, No. 1

(1947).

23 Reynolds v. Sim s, 377 U.S. 533 (1964); W esberry v. Sanders, 376

U.S. 1 (1964); Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368 (1963).

24 Justice, U.S. Civil R ights Comm. Rep. 1961, pp. 2-3.

25

But if the poor and Negroes served on juries, would

official oppression continue? Probably not, for juries es

tablish standards of community conduct. By wrongful

acquittals they endorse crime, 25 by proper convictions

they contain it. The Commission has noted:

“The jury is perhaps the most important instrument

of justice. For jury service is the only avenue of di

rect participation in the administration of justice

open to the ordinary citizen. Moreover the function

of the jury can be a solemn one. It is the jury, not

the judge, who must pronounce a man ‘guilty’ or

‘not guilty’ — an awesome responsibility.” 26

Although the nation has declared a war on pover

ty 27 it often seems that white southern justice has de

clared a war against the poor. And there are many poor

as Alexis de Tocqueville, in his notebook recording his journey in

the U nited S tates recounts this conversation w ith a M ontgomery,

A labam a law yer in 1832:

De Tocqueville asks, “Is it then tru e th a t the ways of the people

of A labam a are as v iolent as is said?”

A. “Yes. There is no one here b u t carries arm s under his

clothes. A t the slightest quarrel, knife or pistol comes to hand.

These things happen continually; it is a sem i-barbarous sta te of

society.”

Q. “B ut w hen a m an is k illed like that, is his assassin not

punished?”

A. “He is always brought to trial, and always acquitted by the

ju ry , unless there are greatly aggravating circum stances. I cannot

rem em ber seeing a single m an who was a little known, pay w ith

his life for such a crime. This violence has become accepted. Each

ju ro r feels th a t he m ight, on leaving the court, find him self in the

same position as the accused, and he acquits. Note th a t the ju ry

is chosen from all the free-holders, how ever sm all th e ir p roperty

m ay be. So it is the people th a t judges itself, and its prejudices

in this m atte r stand in the w ay of its good sense.”

De Tocqueville, Alexis, Journey to America, edited by J. P. Mayer,

Yale U niversity Press, New Haven, translated by George Lawrence,

1960, p. 108).

26 Justice, ibid., p. 89.

27 Economic O pportunity A ct of 1964.

26

— 40,000,000 to 50,000,000 28 poor. They are invisible,

“off the beaten track,” away from the suburbs. And it is

in the suburbs where jurors live: “. . . the very develop

ment of the American city has removed poverty from

the living emotional experience of millions upon mil

lions of middle-class Americans.” 29

The exclusion of the poor by Literary Digest jury

selection systems by key-man 30 or other biased polling

techniques is disastrous for the jury system — and for

justice. “The poor are not like everyone else. They are

a different kind of people. They think and feel differ

ently; they look upon a different America than the mid

dle class looks upon. They, and not the quietly desper

ate clerk or the harried executive, are the main victims

of this society’s tension and conflict.” 31

Michael Harrington also points out that “The mid

dle class does not understand the nature of its judg-

28 H arrington, Michael, op. cit. p. 9.

22 Ibid., p. 12.

30 See generally The Jury System, in th e Federal Courts, W est P u b

lishing Co., St. Paul, (1960). Snead, W. E., and Womack, J. E., Com

m ent: Juries — Selection of Federal Jurors — Exclusion of Economic

Class — N atural Resources Jrnl., p. 181 (Mar. 1961). “The character

of the key-m an system itself m ight give rise to an inference of dis

crim ination. If the key-m an is not acquainted w ith Negroes or la

borers it is un likely h e w ill pick them fo r the a rray (Ibid., pp. 185-6).

U nder the New Mexico D istrict key-m an system, an impossible b u r

den of proof is placed on one w ho challenges the ju ry panel o r a rray

on the ground of exclusion of an economic class (Ibid., 186). The

prospects of successful a ttack are discouraging. The system itself in

sulates ju ry selection from attack. The righ t to have a represen tative

ju ry under these circum stances is a righ t w ithout a rem edy (Ibid.,

p. 187).

31 Ibid., p. 135. “A fter one reads the facts, e ither th e re are anger

and shame, or the re are not. And, as usual, the fate of the poor hangs

upon the decision of the better-off.” (Ibid., p. 156) See also Gallup,

George, op. cit., pp. 60-1.

27

ments. And worse, it acts upon them as if they were

universal and accepted by everyone.” 32

But any system of jury selection which fails to af

firmatively seek out jurors from all segments of society

will almost inevitably be “predominantly male, middle-

aged, middle-minded and middle class.” 33

And there is little doubt that jurors tend to vote in

accordance with their consciences — and conscience may

well be a creature of experience. What many lawyers

have known, others are now submitting to study. One 34

stated:

“In reality jury deliberations are often anything but

rational and certainly never confined solely to the

evidence . . . Figuring in deliberations were trial func

tionaries . .. the evidence . .. and nontrial matter.

Nontrial matter consisted of ‘weather,’ ‘people on the

jury or in the community,’ ‘reputation of the parties

in the case,’ ‘the famliy of the accused,’ ‘reputation of

the lawyers,’ and ‘race and racial differences.’ ” 35

* ❖ ❖

“Voting by the jurors in East Baton Rouge Parish

evidenced considerable uniformity. Among re

sponding petit jurors, associations between birth

place, previous jury service, socio-economic class,

and a vote of guilty or not guilty were significant.

. . . Individually, previous jury service and a birth-

32 Ibid., p. 125.

83 A com m ent of Mr. Justice Devlin appearing in M em orandum

subm itted by the N ational Council for Civil L iberties to the D epart

m ental Com m ittee on Ju ry Service, th e Home Office, October, 1963,

p. 2.

84 Reed, J. P., Ju ry Deliberations, V oting and Voting Trends, Vol.

45, No. 1, The Southw estern Social Science Q uarterly 361 (1965).

as Ibid., p. 364.

28

place in the Anglo-Saxon northern part of Louisiana

produced proportionally a greater number of guilty

votes than ‘fresh jurors’ (no previous jury service)

and a birthplace in the French southern part of the

state. The class based nature of the juror’s vote ap

peared in associations between occupation, educa

tion, and vote outcome. “. . . the higher the status of

the individual juror the more likely he was to vote

guilty; the lower the status of the individual juror

the more likely he was to vote not guilty.”

❖ ❖ ^

“Petit jurors also differentially treated persons

accused of a crime. Persons with high occupational

status were much more frequently held not guilty

than their low socio-economic counterparts. 38

̂ ^

“Judgment by one’s peers has been running

counter to holding the accused strictly accountable

for his offense. Among jurors whose socio-economic

status was low there were more not guilty votes for

both low-and high-status violators of the criminal

code than guilty votes. High status jurors were

fewer in number and rarely, if ever, majorities on

the juries in East Baton Rouge Parish.”

* * *

“On a national level, the long term trend in ver

dict outcomes would seem to be quite similar. In

writings by Koestler, Bok, and Martin and Swinney

the implications are that ‘jury justice’ favors the

accused. While the data are somewhat old and sparse,

they lend support to the literature which has made

the same claim for many decades.” 37

36 Ibid., pp. 365-6.

37 Ibid., p. 369.

29

The Results of Discrimination in Jury Name Selection.

In the South the results of racial discrimination are

often so apparent as to be assumed. Most of us have

come to accept that which we have always known. “We

have called the figures startling; but we do not feign

surprise because we have long known that there are

counties not only in Mississippi but in the writer’s own

home state of Alabama, in which Negroes constitute the

majority of the residents but take no part in government

either as voters or as jurors. Familiarity with such a

condition thus prevents shock, but it all the more in

creases our concern over its existence.” 38

Lynchings were for years an extra curricular activity

of the worst and best elements in the southern town. Ap

proximately 5,000 Negroes have been reported lynched

in the United States since 1859.39 The number not re

ported and consequently not known must be staggering.40

“When a lynching took place, neither local nor state

officials made any honest effort to apprehend and punish

the criminals. The police either didn’t investigate at all

38 U.S. ex. rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71, 78-79 (1959).

39 Ginsburg, R., 100 Years of Lynchings, L ancer Books, New York,

1962, p. 253.

40 As is the num ber and w hite/N egro ratio of legal executions for

the crim e of rape. Betw een 1930 and 1963, 449 m en w ere executed

for rape; 45 (10%) w ere white, 402 (89.6%) w ere Negroes, 2 w ere

Indians. Of these executions the 11 states of th e Old Confederacy

accounted fo r 393 (87%) of the total; two arose in federal courts and

the rem ainder in border and adjoining states. Negroes fared better

w ith m urder. Of a national to ta l of 3315 executions for m urder only

1625 (49%) w ere Negroes. Executions, N ational P risoner Statistics,

U.S. Dept, of Justice, B ureau of Prisons, No. 34, May 1964. For a

resum e of recen t civil rights killings see M axwell, Neil, The Liuzzo

Case, The W all S tree t Journal, May 4, 1965, rep rin ted here as A p

pendix C, p. 83. Since the M axwell article, O’Neal Moore, Negro

D eputy Sheriff was slain (June 2, 1965) a t Varnado, Louisiana, 7

m iles no rth of Bogalusa.

30

or reported, tongue in cheek, that they were unable to

identify anybody, though who the guilty parties were was

commonly neighborhood knowledge. Judges, attorney-

generals (sic), and governors almost never made any at

tempt to spur them into active performance of their duty.

When, for a wonder, they did, they got no co-operation

or support from the body of ‘best citizens’ in the local

community or the state; on the contrary, the ranks closed

now as always, and all investigators got was grim warn

ings to mind their own business under penalty of tar and

feathers.” 41

“Contrary to wide-spread popular belief, which the

South itself has fostered, the persistence of lynching in

the region down to the present has not been due simply

and wholly to the white-trash classes. Rather, the major

share of the responsibility in all those areas where the

practice has remained common rests squarely on the

shoulders of the master classes. The common whites have

usually done the actual execution, of course, though even

that is not an invariable rule (I have myself known uni

versity-bred men who confessed proudly to having helped

roast a Negro). But they have kept on doing it, in the last

analysis, only because their betters either consented

quietly or, more often, definitely approved.” 42

Yesterday’s lynch mob may be tomorrow’s jury. As

W. J. Cash said. “. . . the South was solidly wedded to

Negro-lynching because of the cumulative power of

habit, obviously.” 43 But more than that, he notes that

in time of stress for “best” as well as the “sorriest crack

er,” lynching was “an act of racial and patriotic expres-

41 Cash, W. J., M ind of the South, V intage Books, New York, 1941,

pp. 309-10.

42 Ibid., pp. 310-11.

42 Ibid., p. 121.

31

sion,” of “chivalry,” an act of “ritualistic value in respect

to the entire southern sentiment. . “It was not wrong

but the living bone and flesh of right.” 44

After Reconstruction — when the courts were even

tually returned to the white South — the Negro “was to

become almost open game.” Negroes and racially mav

erick white Southerners could find no justice — only

oppression — in the halls of southern justice.45

Southern justice was and is as white as the marble on

a courthouse facade.

Often this court has been forced to take judicial notice

of facts obviously true.46 This court knows the nature

and extent of racial segregation in the South — and in

Jefferson County, Alabama. Indeed the name Birming

ham provided the world a pre-Selma symbol of intransi

gence. This court also knows of the “grisly ‘Hobson’s

Choice’ ” 47 much of the South provides a Negro criminal

defendant on trial for his life.

Segregated Justice.

The county courthouse has always been a seat of pow

er in the South. Yesterday Negroes rarely went there.

When they went it was to pay taxes or purchase a license

or be a witness or be tried. Tomorrow they may go there

to vote or serve on juries or, perhaps, to work, or prac

tice law, or see a friend. But that tomorrow — like so

many of the South’s tomorrows — will never come if

segregated justice continues.

44Ibid.

« Ibid., p. 122-3. See also Ibid., 425.

46 Sometimes th a t the facts noticed are painful and an indictm ent

e ither of a society or the law yers w ith in it. See U.S. ex. rel. Goldsby

v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71 (1959).

« W hitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Circ. 1964).

32

Southern federal courts are themselves almost totally

white;48 Jefferson County’s courts more so.49

In Jefferson County no Negroes work for the Jury

Board (R. 136). In the Bessemer Division the names of

Negroes called for petit jury service are placed on the

bottom of the jury list (R. 397, 399). And they are segre

gated and placed on jury number 4 (R. 360-1, 394-7). The

courthouses, Birmingham and Bessemer, were segre

gated. (See R. 385-7.) The courthouse segregation policy

— drinking fountains and rest rooms — is in the hands

of the county commission (R. 399). The court noted that

there was a time when they used a “C” or some desig

nation to show who was colored or white (R. 428). The

names of jurors have been carried over from previous

lists (R. 156). Voter lists in the county now designate

color (R. 165).

In this system of justice it should cause no wonder

ment that when a Negro served on a jury with 11 white

men (the defendant was a Negro) the whites allowed

the lone Negro juror to decide the case (R. 116).

During the trial of this case in a federal court a white

witness used the term “nair” in making his point to a

Negro attorney (R. 61-2). The solicitor himself referred

to a Negro witness as “Arthur” (R. 130). When called

48 Racial D iscrim ination in the Southern Federal Courts, Southern

Regional Council, A tlanta, 1965.

48 See Morgan, Charles, A Tim e to Speak, H arper and Row, pp.

113-122. Morgan, Charles, Integration in the Y ellow Chair, New South,

Southern Regional Council, A tlanta, Feb. 1963, p. 11. “The Deep South

rem ains tru e to its heritage. The segregation of th e m achinery of

justice, police, judges, courts and juries, rem ains. “B ut rea lly s ta

tistical evidence is unnecessary. One need only en ter a sou thern court

room to see discrim ination a t w ork.” Lester, A nthony, Justice in the

A m erican South, A m nesty In ternational, 1 M itre C ourt Buildings

Temple, London, E.C. 4., (1965) pp. 12-3.

33

to task over his pronunciation of the word Negro he re

sponded, “I can’t change my speech after 59 years.” The

court stated: “We understand.” (R. 132-3).

Although between 1960 and 1964, 145 Negroes applied

to the City-County Civil Service System for the position

of clerk-typist only 17 passed their examinations. Some

of these 17 have been certified to county officers but the

county officer need take only 1 of 3 names furnished

to him (R. 452-6). Of course the Jury Board took none.

Civil rights killings in the South increase. Convictions

are few. And when convictions occur the sentences are

wrist slaps — more an encouragement to murder than

a guarantor of order.50

All-white justice as it exists in Jefferson County and

other sections of Alabama and the South makes heroes of

killers, rallying points of men accused of heinous crimes.

Philadelphia and Jackson, Mississippi, law men and fer

tilizer salesmen, Selma and Birmingham Klansmen,

bombers, burners, and sharpshooters strike terror in the

hearts of Negro citizens seeking to free themselves from

the vestiges of slavery.

Any consideration of the systematic exclusion of Ne

groes from juries requires recognition of the totality of

the system of segregated justice.51

And the cases which consider and condemn total ex