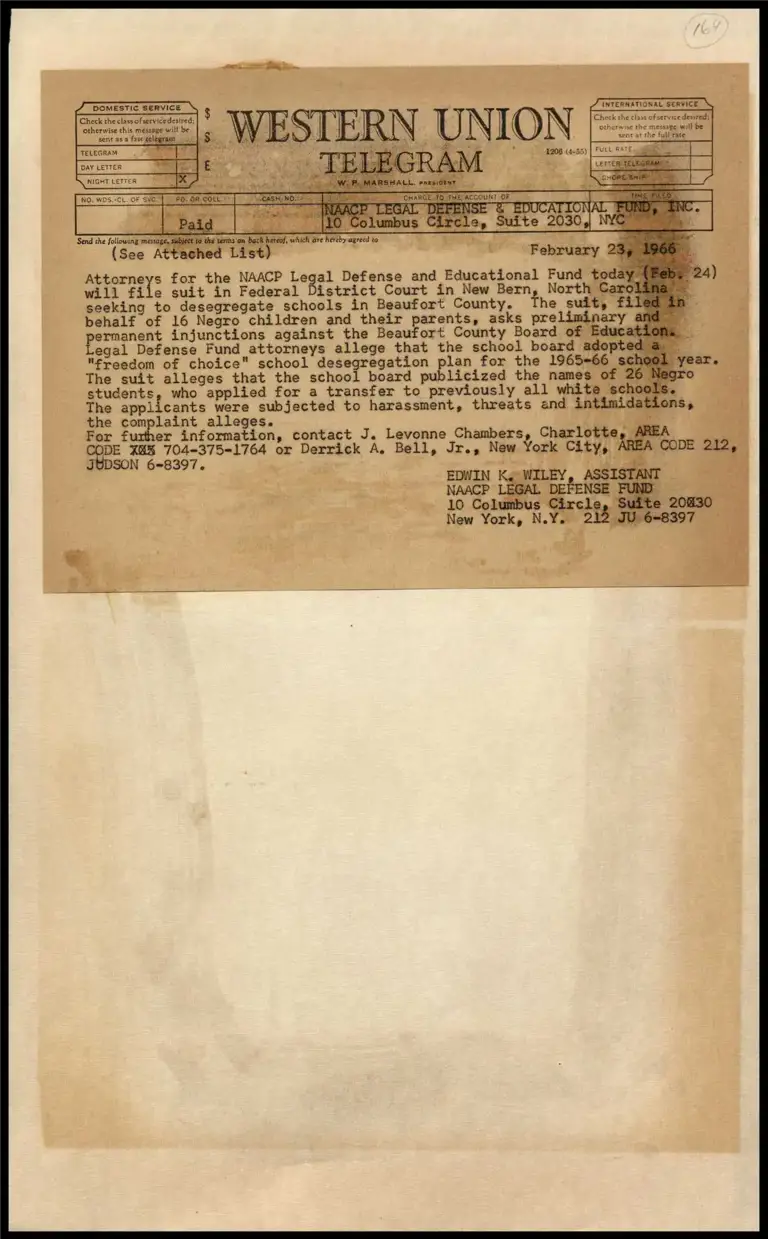

Desegregation in Beaufort County, N.C. Schools (Telegram)

Press Release

February 23, 1966

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 3. Desegregation in Beaufort County, N.C. Schools (Telegram), 1966. 8dfe28cc-b692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d9513df0-143b-459c-ae1f-3e0398b0c24b/desegregation-in-beaufort-county-nc-schools-telegram. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

J_DOMESTIC SERVICE \ CZ INTERNATIONAL SERVICE \

‘Check the class ofservicedesired; Check the class ofservice desired:

‘otherwise this méssage-will be otherwise the message will be

sent asa fase mb i 2

TELEGRAM

DAY LETTER

NIGHT LETTER

[[no, wos.-cu. oF Sve:

ce eee

will fi

seeking to de

behalf of 16

students

The applic

the complaint alleges. :

For furher information, contact J. Levonne Chambers, Charlotte, AREA

CODE xa 704-375-1764 or Derrick A, Bell, Jr., New York City, AREA CODE 212,

SON 6-8397. fs

EDWIN KssWILEY, ASSISTANT

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 20830

New York, N.Y. 219 JU 6-8397