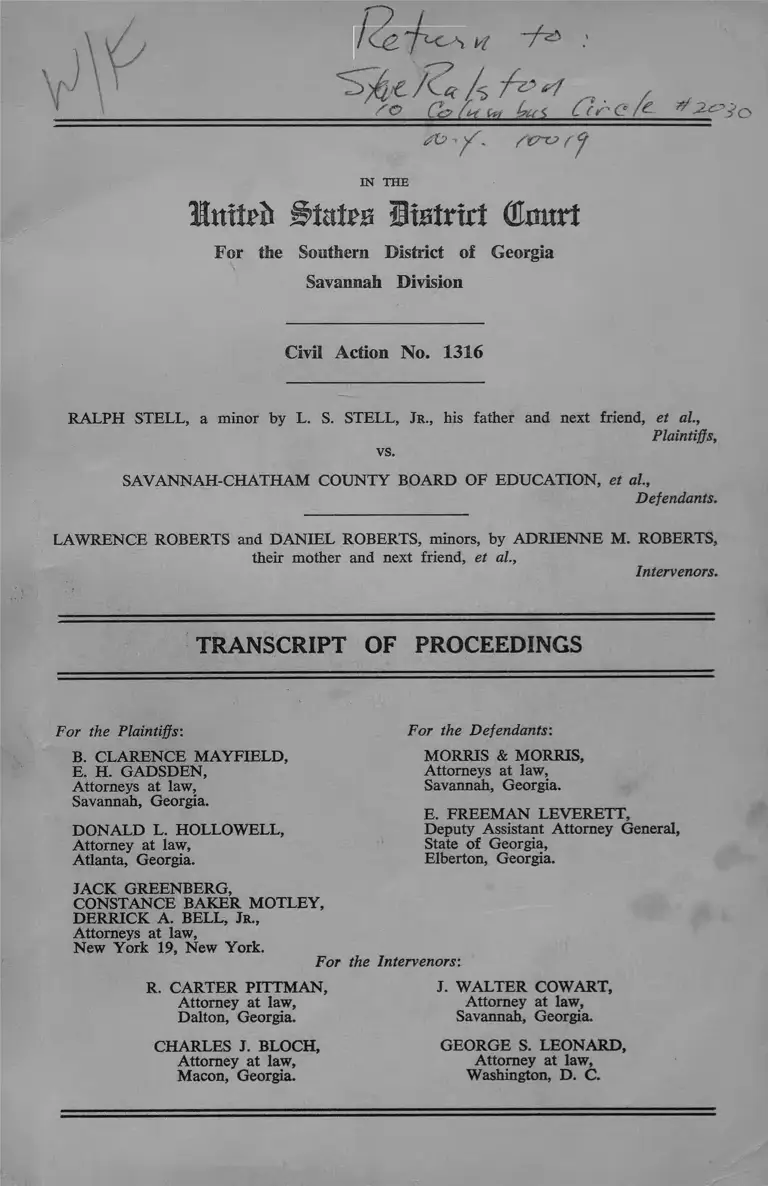

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Transcript of Proceedings

Public Court Documents

June 15, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Transcript of Proceedings, 1963. d121972f-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d965a6d8-9452-495b-84ad-0d5be465964a/stell-v-savannah-chatham-county-board-of-education-transcript-of-proceedings. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

\ r

\ \ 0\ Y

\4 ~h* :

U ~f~z>*1 /

VO OyftrU , Ur< O r e f e

<&> ^ /eTxv f<j

IN THE

MxnUft States Sistrirt (Zimvt

For the Southern District of Georgia

Savannah Division

Civil Action No. 1316

RALPH STELL, a minor by L. S. STELL, Jr ., his father and next friend, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

SA Y A N N A H -C H A T H A M C O U N T Y BOARD OF E D U C ATIO N , et al.,

Defendants.

LAW RENCE ROBERTS and D A N IE L ROBERTS, minors, by A D R IEN N E M . ROBERTS,

their mother and next friend, et al.,

Intervenors.

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS

For the Plaintiffs:

B. CLAREN CE M AYFIELD ,

E. H . GAD SD EN ,

Attorneys at law.

Savannah, Georgia.

D O N A LD L. HOLLOW ELL,

Attorney at law,

Atlanta, Georgia.

JACK GREENBERG,

CO N STAN CE BAK ER M O TLEY,

DERRICK A . BELL, Jr„

Attorneys at law,

New York 19, New York.

For the

R. CARTER PITTM AN ,

Attorney at law,

Dalton, Georgia.

CHARLES J. BLOCH,

Attorney at law,

Macon, Georgia.

For the Defendants:

MORRIS & MORRIS,

Attorneys at law.

Savannah, Georgia.

E. FR EEM AN LEVERETT,

Deputy Assistant Attorney General,

State of Georgia,

Elberton, Georgia.

Intervenors:

J. W A L T E R C O W A R T,

Attorney at law,

Savannah, Georgia.

GEORGE S. LEO N ARD ,

Attorney at law,

Washington, D . C.

I N D E X

page

Transcript of Proceeding............................................ 1

Certificate of Court Reporter............................... 266

TESTIMONY

P l ain tiffs ’ W itnesses

D. L. McCormac:

C ross......................................................................... 5

Recross..................................................................... 40

L. Scott Stell, Jr.:

D irect....................................................................... 61

C ross......................................................................... 68

I ntervener ’s W itnesses

D. L. McCormac:

D irect....................................................................... 94

Dr. R. T. Osborne:

D irect....................................................................... 99

C ross......................................................................... 121

Redirect................................................................... 123

R ecross..................................................................... 124

Re-redirect .............................................................. 124

Dr. Henry E. Garrett:

D irect....................................................................... 127

C ross......................................................................... 147

Redirect................................................................... 150

R ecross..................................................................... 153

Re-redirect .............................................................. 154

Re-recross ............................................................... 171

Re-re-redirect.......................................................... 172

11

PAGE

Dr. Clairette P. Armstrong:

Direct ...................................................................... 176

Cross ....................................................................... 184

Dr. Wesley Critz George:

Direct ...................................................................... 191

Dr. Ernest van den Haag:

Direct ...................................................................... 218

Cross ...................................................................... 249

Intervener’s Exhibit 1 267

Transcript of Proceedings

[ 1 ] IN TH E

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe th e S outhebn D isteict oe Georgia

Savannah D ivision

Civil Action No. 1316

---------------------- o------------------ —

R alph S tell , a minor by L. S. S tell , Jb., bis father and

next friend, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

S avannah -C h ath am C ounty B oaed op E ducation, et al.,

Defendants.

L aweence R obeets and D aniel R obeets, m inors, by

A dbienne M. R obeets, their m other and next friend ,

et al.,

Appearances:

Intervenors.

For the Plaintiffs:

B. Clabence M ayfield , E. H . Gadsden, Attorneys at

law, Savannah, Georgia.

D onald L. H ollowell, Attorney at law, Atlanta,

Georgia.

Jack Geeenbeeg, C onstance B akee M otley, D eeeick

A. B ell, Jk., Attorneys at law, New York 19, New

York.

2

[2] For the Defendants:

M orris & M orris, Attorneys at law, Savannah, Georgia.

E. F reeman L everett, Deputy Assistant Attorney

General, State of Georgia, Elberton, Georgia.

For the Interveners:

R. Carter P ittm an , Attorney at law, Dalton, Georgia.

J. W alter Cowart, Attorney at law, Savannah,

Georgia.

Charles J. B loch , Attorney at law, Macon, Georgia,

at law, Dalton, Georgia.

George S. L eonard, Attorney at law, Washington, D. C.

Colloquy

The Court: All right, are there any motions by any

members of the Bar?

(Court Reporter: No motions were made.)

The Court: All right, the case set here this morning

is the case of Ralph Stell, et al., vs. Savannah-Chatham

County Board of Education, et al. I am going to take

this case up and decide it one way or the other. I under

stand this is a case to be heard on its merits.

I might say that I have had inquiries about what [3]

I am going to do about my court starting Monday in

Savannah. If we are not through with this case this

week, then I am going to recess it over to Savannah next

week, and open my court down there and then come right

back on this case and continue on all next week, and if

necessary I will adjourn the Savannah court entirely and

continue right on through with this case until I get it

disposed of, and nobody is going to try to continue this

case or put it off. I am going right straight through until

3

I get through with it and render a judgment one way or

the other in it.

Now, what is the announcement in this case of Ralph

Stell, by next friend, et al. vs. Savannah-Chatham County

Board of Education, et al.?

Mrs. Motley: The plaintiffs are ready, your Honor.

The Court: What about the defendants?

Mr. Morris: The defendants are ready, your Honor.

The Court: Since the case is brought by Ralph Stell,

as plaintiff, you may proceed.

Mrs. Motley: We would like to call Mr. McCormac to

the stand.

Mr. Bloch: I f the Court please, I would like to present

Mr. George S. Leonard, of Washington, D. C., a member

of the Bar of the District of Columbia and of New York

and the Supreme Court of the United States, and ask leave

for him to [4] participate to some extent.

The Court: I am sure there are no objections. We

are glad to have you with us. Now, as I understand, both

sides are ready, so you may proceed.

Mrs. Motley: We would like to ask that Mr. McCormac

take the stand.

The Marshal: Do you want them to call all of their

witnesses ?

The Court: Yes. How about each side calling all of

their witnesses, and we will know more about the length of

the trial. Suppose each side call their witnesses and let

them be sworn now.

Mrs. Motley: Rev. Stell, Mrs. Mabel Godson. Those

are all the witnesses we have, your Honor.

The Court: All right, suppose you call the witnesses

for the other side now? Who is going to try this case for

the other side? Call your witnesses first, though?

Mr. Pittman: Dr. Osborne and Dr. Garrett.

The Marshal: Dr. Osborne and Dr. Garrett.

Colloquy

4

Mr. Pittman: Your Honor, since this case involves

issues on which lawyers are not ordinarily equipped we

would like to divide the work among the attorneys.

The Court: That is perfectly all right. Only thing

is I just abhor to get into the trial of a case and have one

[5] lawyer jump up and another one pop up. Of course,

I know you all are not going to do that.

Mr. Pittman: Well, we will divide the work, question

ing and cross-examining the witnesses, and as to the objec

tions and so forth, one counsel will handle that.

The Court: That will be all right, just so we don’t

have two or three lawyers jumping up at one time.

The Clerk: Do you have any witnesses, Mr. Morris ?

Mr. Morris: None other than Mr. McCormac.

The Court: How is that?

Mr. Morris: None other than Mr. McCormac. He is

all we have, and he has already been called by the other

side.

The Court: How about you gentlemen over there? Do

you have any witnesses?

Mr. Pittman: We will have witnesses coming in as

we need them. They are special men, college professors.

The Court: All right, notify the Marshal as they come

in, so we will know.

Mr. Pittman: All right, sir.

The Clerk: All the witnesses raise your right hands.

You do solemnly swear that the evidence you shall give

upon the trial of the issues in the case between Ralph Stell,

by his next friend, etc., Plaintiffs vs. the Savannah-Chatham

County Board of Education, et al., shall be truth, the whole

truth, and [6] nothing but the truth. So help you Cod.

The Court: All right. Do the attorneys on both sides

want the witnesses placed under the rule, or is it satis

factory for them to stay in the court room?

Mr. Pittman: We have no objections to them remaining

in the court room.

Colloquy

5

The Court: All right, is that satisfactory with the

plaintiffs for the witnesses to stay in the court room, or

do you want them placed in the witness room?

Mrs. Motley: We have no objections, your Honor, to

them staying in the court room.

The Court: All right, then you may proceed for the

plaintiff.

Mrs. Motley: We now call Mr. McCormac to the stand

for the purpose of cross-examination, your Honor.

The Court: All right.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

[7] H. L. McCokmac, called by the plaintiffs for the

purpose of cross-examination and after having been first

duly sworn the truth, the whole truth and nothing but

the truth to tell, testified as follows:

On cross-examination by Mrs. M otley:

Q. Mr. McCormac, are you a defendant in this case?

A. Yes.

Q. Are you the Superintendent of Schools in Chatham

County? A. Yes, I am.

Q. How long have you been Superintendent of Schools

in Chatham County? A. Acting Superintendent since

November 1, 1958, and Superintendent since January 16,

1959.

Q. Hid you hold any position with the Chatham County

School System prior to 1958? A. Yes.

Q. What was that? A. I was Assistant Superintendent

in charge of instruction at the time I became Acting Super

intendent.

Q. And, how long have you held that position? A. Since

the fall of 1956.

6

[8] Q. Did you have any position with the Chatham

County School System prior to the fall of 1956! A. Yes,

for the year 1955 and ’56 Director of Secondary Education.

Q. Did you have any position with the School System

prior to that time! A. No, not before August 1, 1955.

Q. So, you have been connected with the Chatham

County School System since August 1st, 1955, is that

correct! A. Yes.

Q. Now, on August 1st, 1955, the Chatham County

Public Schools were operated on a racially segregated

basis, were they not! A. Yes.

Q. Now, since August 1st, 1955, until the present day,

has there been any de-segregation of the Chatham County

Public Schools to your knowledge! A. No.

Q. Now, were you connected with the school system in

1955, when a petition was presented to the School Board

by negro parents to desegregate the schools!

Mr. Leverette: May it please the Court, we think

the petition will speak for itself. The petition,

itself, would be the highest and best evidence.

[9] The Court: Well, I think he could testify

to it, if he knows of his own knowledge. She is not

going into what it contains. She just asked him if

it was presented. I think that is admissible. I

think the question, as asked, is admissible. She is

not going into the merits or what is contained in the

petition. She just asked him if it was presented.

Go ahead.

The Witness: All I can say is, as I understand,

that something with regard to it was brought to

the Board of Education, but I was not directly

working with the Board at that time.

Q. Now, were you connected with the school system

when a petition was presented by negro parents seeking

de-segregation of the schools in October of 1959!

D. L. McGormac■—-for Plaintiffs—Gross

7

Mr. Leverett: There again, your Honor, she is

stating what the petition contains.

The Court: Well, I think he answered it just

now. I will let her ask that question.

The Witness: I was Superintendent at that

time, yes, the date you mentioned.

Q. Well, do you have any knowledge of any action

taken by the Board with respect to that petition? A. I

do not know of any action of the Board.

Mr. Leverett: May it please the Court, I think

the records of the Board would be the highest and

best evidence.

[10] The Court: Well, if he goes into the

contents of any of the records, or anything like that,

then you can raise your objection. I think the, ques

tion, as asked, is admissible. You can go ahead.

Q. Do you have any knowledge of any meetings, con

ducted by the Board, concerning de-segregation of the

Public Schools of Chatham County? A. Meetings called

for the purpose of discussing the matter?

Q. Yes? A. I know of no general board meeting that

was called for that purpose.

Q. Do you know of any other meetings, called by the

Board, other than board meetings, for the purpose of

discussing the de-segregation of the Chatham County Public

Schools? A. There were some committee hearings for

various groups to appear before a Committee of the, Board,

which I did not attend.

Q. Do you know who, on the Board, served on the

Committee? A. I know the Chairman of the Committee.

Q. Who is that? A. Mr. Shelby Myrick, Jr.

Q. Do you know any other members of the. Committee ?

[11] A. For that particular purpose, I don’t recall. That

was a special arrangement for the hearing.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

8

Q. Do you know of any action taken by the Board as

a result of those meetings? A. From the standpoint of

taking action on the basis of the hearing, I know of none,

no.

Q. Do you know of any present plan of the Board of

School Commissioners of Chatham County for de-segregat-

ing the schools as of September, 1963, or any future date ?

A. No.

Q. Do you know whether or not the Board has estab

lished any procedure to be followed by negro students

seeking initial assignment or transfer to white schools?

A. No.

Q. Now, isn’t it a fact, that in September of 1962

thirteen negro parents made application for admission or

transfer of their children to a white elementary known as

the Pulaski School in the City of Savannah? A. I under

stand that a group did appear at that school.

The Court: Not what you understand, but what

you know. Do you know that, of your own knowl

edge ?

The Witness: I was told that.

Q. By whom were you told that? [12] A. By the

principals.

Mr. Leverett: Your Honor, we object to any

thing that this witness was told by anybody else.

The Court: That’s right. I asked him the ques

tion and he said that he was told by so and so. Well,

I think you will agree that is hearsay evidence, if

somebody else told him, wouldn’t you?

Q. Now, your testimony is that you have no knowledge

of those applications by negroes for admission to the

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

9

Pulaski School. Is that your testimony! A. I did not

say that.

Q. Well, that is what I am asking you. What knowl

edge do you have about those applications for admission

to the Pulaski School! A. The principal of the school

stated that they—

The Court: —Now, you can’t go into what the

principal of the, school stated to you. That is hear

say evidence.

Q. Just tell us what you know about those applications!

The Court: Just what you personally know

about it.

The Witness: All I know is that I was told that

they—

The Court: —I have told you twice that you

can’t testify to what somebody else told you. That

is hearsay evidence,. [13] Just testify from your

personal knowledge.

The Witness: Well, I will say that they appeared.

Q. Pardon me! A. I will say that they appeared, or

their parents did.

Q. Did you see the applications made out by those

parents! A. No.

Q. Did the principal of the school present those applica

tions to the Board, to your knowledge! A. No.

Q. Who acted on those applications? A. The principal

of the school advised them what to do.

Q. Advised the parents what to do? A. Ye,s.

Q. Do you know what advice he gave them?

The Court: Wouldn’t that he hearsay?

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

10

Mrs. Motley: Not if he knows what advice he

gave them.

The Court: Well, if he knows of his own knowl

edge, I cautioned him three times, but it apparently

didn’t do any good, to just testify to what he knows

of his own personal knowledge. If you know of

your own knowledge, of course, you [14] can testify

to it, but anything somebody told you you cannot

testify to it.

Q. Well, let me ask you this question: Do you know

what happened to those applications? A. I simply know

that the applications were not approved.

Q. Now, when you heard about these applications, did

you discuss that matter with the Board? A. I don’t recall

discussing it with the Board.

Q. You never made any mention at all to the Board of

the fact that negroes had applied for admission to white

schools, is that it? A. No.

Q. You did not? A. No.

Q. Let me, ask you this: Do you know of any action

taken by the Board with respect to those applications? A.

No.

Q. Do you know of a letter written to the Board by

those parents protesting the assignment to negro schools?

A. Such a letter was sent to the Board.

Q. Did you ever see the letter? A. Yes.

Q. Did you ever discuss the letter with the Board?

[15] A. I recall no discussion with the Board on the letter.

Q. Now, you were subpoenaed to bring certain maps to

this hearing, were you not? A. Yes.

Q. Did you bring them? A. Yes.

Q. May I see them? A. Yes.

Q. Now, are all of these the same, or are they different?

A. They are different.

I). L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

■ l

Mrs. Motley: Will you mark these—or this map

here for identification?

(Note: Accordingly, same was then marked for

identification as Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 1.)

Q. Let me show you the map, which has been marked

as Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 1 for identification, and ask you

to explain what that map shows? A. This is a map of

Chatham County showing attendance areas for negro

schools.

Q. The negro elementary schools, or negro high schools,

or all negro schools? A. We have only one identification

of districts [16] for all purposes.

Q. So, all negro schools aye on that map? A. The

schools are not on this map, but the attendance districts

are.

Q. For each negro school? A. A district does not indi

cate a school. Croups of districts may be assigned to a

school, junior high school, elementary and senior high

school.

Q. Well, let’s get it clear in the record, please, what

this map shews. You say this map shows districts and not

the school zone for each negro school? A. That is correct.

Q. Now, these districts, you say one or more districts

may be assigned to a school? A. Yes.

Q. Now, how are these districts determined? A. I don’t

know the entire history of the development of it, but it is

a matter that’s grown up, depending on, maybe, several

factors, but for a long time they have been identified by

districts, which are sometimes changed, divided and so

forth, for convenience in assigning to schools. What the

original basis for the outline of these districts was I do

not know.

Q. Now, do these district lines have any relation [17]

to the capacity of a particular school? A. Maybe to some

D. L. McCormao—for Plaintiffs—Cross

12

extent because of population shifts and so forth. We

sometimes have to re-shape because of housing problems,

which have been serious for many years. We, maybe,

assign half of one of these and identify it to a school

because of school capacity for housing. They do change

occasionally. These were the maps used in 1962 and 1963.

Q. But this map takes into consideration the total

negro school population of Chatham County? A. Yes, and

we would identify levels in each of these districts.

Q. That is elementary, junior high and senior high?

A. They are on this, but don’t show up too well, the schools

to which they would go but not total numbers, but we do,

in assigning, have to prepare such lists, which I don’t have.

Q. What do those numbers refer to on there? For

example, 103(a), what does that refer to? A. It is just

merely one of the areas used on the map for the purpose

of assigning people in the area described (circled there),

to a particular school. The “ A ” or “ B ” simply means

that once it was 103 and divided into two, and identified

as 103(a) and 103(b).

[18] Q. Is there a separate school in 103(a) and 103(b) ?

A. No, but students in 103(a) may go to one school and

those in 103(b) to another, just as you would have for any

two adjacent areas. It could happen at any place else.

Mrs. Motley: Will you mark this for identifica

tion, please?

(Note: Accordingly, same was then marked for

identification as Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 2.)

Q- I show you a map; which has been marked as Plain

tiff’s Exhibit No. 2, for identification, and ask you to explain

that map, please? A. This is a map of the city. The other

was a map of the entire county. Because of the problem

in size and the density of population we use separate maps.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs— Cross

13

This is for the city, and designates the attendance areas

for negro schools.

Q. Now, are all the negro schools in the City of Savan

nah shown on this map? A. Not the schools, hut all of the

attendance areas.

The Court: What?

The Witness: The attendance areas, sometimes

referred to as districts.

Mrs. Motley: Mark this one, please.

(Note: Accordingly, same was then marked for

identification [19] as Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 3.)

Q. I show you a map, which has ben marked as Plain

tiff’s Exhibit No. 3, for identification, and ask you to ex

plain that map, please? A. This is the county map, with

attendance areas for whites.

Q. That shows—well, that takes into consideration all

of the white school population in the county, is that right?

A. That’s right, with the exception of the city, which is

blocked out here, as in the other case.

Mrs. Motley: I would like to have this marked

for identification, please.

(Note: Accordingly, same was then marked for

identification as Plaintiff’s Exhibit 4, for identifica

tion.)

Q. I show you another map, which has been marked

Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 4, for identification, and ask you to

explain that map, please? A. This is the map of the city,

showing the attendance areas for whites.

Mrs. Motley: We would like to offer these maps

into evidence, your Honor.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

14

The Court: Any objections?

Mr. Cowart: May we see them?

[20] The Court: Yes.

Mr. Cowart: No objections.

The Court: Admitted without objections.

By Mrs. Motley.

Q. Now, isn’t it a fact that these school district lines

overlap, that is, where negro and white live in the same

area? A. Yes, and different areas.

The Court: I didn’t understand you. You say

different areas?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

Q. Now, are you familiar with ail of these school dis

tricts yourself? A. Not in detail, except as the maps indi

cate.

Q. Pardon me? A. Except as the maps indicate. I

would not know all of the details in regard to them.

Q. Now, isn’t it a fact, that negro children living out in

the country are transported into the city of Savannah to

attend negro schools and pass white schools in the process ?

A. That does happen.

Q. Do you know about the negro children who live in

the Grove Point Road area, who are transported to the

Sophronia Tompkins School and pass the Robert Groves

School in [21] the process? A. For the moment, I can’t

identify Grove Point.

Q. Do you want to look on the map of negro schools?

A. I am not sure that it will indicate it, but I will need the

maps. (Witness examining map) I would have to know

exactly where Grove Point is and, frankly, I don’t.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

15

Q. About ten miles south of Savannah on Highway 17 f

A. Then the route would not be—did you say Groves High

School?

Q. Yes, Robert W. Groves High School? A. Then I

would not know of any transportation by there from Grove

Point unless the bus takes a route that I am not familiar

with, because that would not be the route to take.

Q. Isn’t the Robert Groves High School nearer to the

Groves Point road than the Tompkins School? A. No.

Q. It isn’t? A. No. I would think it would be a half a

mile or more nearer to Tompkins from Grove Point.

Q. Than to Robert Groves School? A. Yes, if it is where

you say it is.

[22] Q. What about Savannah High School, which is

a white high school, isn’t it? A. Yes.

Q. Isn’t that nearer to Grove Point than the Tompkins

School is? A. I am not sure of those distances.

Q. How far would you say the negro children have to

travel from Grove Point to reach the Tompkins School?

A. As I say, I can’t quite identify Grove Point. I think

I know, roughly, where it is ; and your question now is

what?

Q. How far is Grove Point from the Tompkins School?

A. I could not answer that.

Q. All right. Do you know anything about the negro

children living in the White Bluff area to travel to De-

Renne, Wheeler and Heard Schools? A. I know where

they are, yes.

Q. Don’t they pass several white schools in the process?

A. I think, on that route, I am sure they would pass one,

if they come directly toward the city, they would pass at

least one.

Q. But they may pass others, you think? [23] A. Pos

sibly, depending on the bus route.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs— Cross

16

The Court: Depending on what!

The Witness: Depending on the bus route.

Q. All right, how about the negro children who live

on Wilmington Island! Where do they go to school! A.

I do not have the record on that. I would say they are

brought into Savannah.

Q. Isn’t there a new school for whites on Wilmington

Island which has just opened up! A. Fairly new, about

six years, I suppose.

Q. Now, far would you say those negro children have

to travel from Wilmington Island to get into the city school,

which they attend! A. Roughly, eight or ten miles.

The Court: By bus !

The Witness: Yes.

The Court: Furnished by the county!

The Witness: Yes.

Q. All right, how about negro children on the Isle of

Hope! A. They are transported into town from the Isle

of Hope.

Q. Don’t they live nearer the Thunderbolt School, which

is white! [24] A. I am not sure that is true, because

Thunderbolt is, of course, not on that Island.

Q. I know it is not on an Island, but isn’t that school

nearer to the Island than to the school to which they are

assigned! A. We have a school that handles students, one

through twelve, and the Johnson School which is probably

a quarter of a mile, something like that, nearer to Isle of

Hope.

Q. Than Thunderbolt! A. Than Thunderbolt School.

Q. Why is the Johnson School one through twelve? A.

A. At one time there was a school there called Ballard

Laboratory School, which was used as a training school for

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs— Cross

17

prospective schools supervised, to some extent, by the col

lege staff, Savannah State College, and—

The Court: What college? I didn’t catch that.

The Witness: Savannah State College. Then in

recent years a school designed for junior-senior high

school students was built there. First, a new school

was built to substitute for the Ballard Laboratory

School, and then the Junior-Senior High School

added, which is a new plant, and use of site and

proximity to the college there were several selections

in consideration—or rather several considerations in

selection of the site but they happened to be on the

same site and are now [25] under the same adminis

tration.

Q. Do you have any other schools which encompass

grades one through twelve? A. We did have at Tompkins.

We are separating the administration there, but we do not

have another situation where we have one through twelve.

We do have one through nine.

Q. What school is that? A. That is Chatham Junior

High School, the old academy.

Q. Is that a negro or white school? A. White.

Q. Is Tompkins School a negro school? A. Yes.

Q. And Johnson is negro, isn’t it? A. Yes.

Q. Now, isn’t it a fact that negro students from the east

side of the City of Savannah have to pass by Savannah

High School, which is white, and Jenkins High School,

which is white, and the John Wilder Junior High School to

attend this Sol C. Johnson School that you just referred

to? A. I think we would have to see bus routes and the

nearest routes from where they actually live, and I think

the only way it could be answered would be to take it area

by area and I am not familiar with all the routes, or the

nearest [26] bus routes. It is possible that they could.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

18

Q. But Savannah High School is on the east side, isn’t

it? A. Yes.

Q. How about the Jenkins High School? A. Southeast.

Q. What about John Wilder Junior High School? A.

Somewhat southeast of the city.

Q. Now, where is the Sol C. Johnson School located?

A. At Thunderbolt.

Q. Where is that with relation to the east side ? Is that

east? A. It is the place to which you referred to a minute

ago.

Q. On the west side? A. On the east side.

Q. Now, isn’t it a fact that negro students living in the

Montgomery Eoad area also pass the Montgomery School

which is white ? A. I do not know whether we actually have

anybody that would do that. If so, it would be few, but I

am not sure that we have any where the new building has

just been completed.

Q. Now, these school zone lines, which we went over on

the map, are children assigned to the school in the [27]

zone in which they live? A. Not necessarily. That de

pends upon housing and whether or not there is adequate

housing close to them, and sometimes we have to shift

segments of these, or these areas, say, to other schools. It

doesn’t mean that once we establish the numbers here that

they would go to the same school indefinitely, and those

things do change occasionally. I am not sure of the point

of your question.

Q. I am getting at the basic purposes of the zone lines,

or district lines, as you call them, the basic purpose is

to assign children to a particular school because they

live in that area, isn’t that the purpose of the lines? A.

Yes, but not in the sense that a school is in the area, be

cause it may not be. There may not be one.

Q. And, when there isn’t a school in the area, they

are assigned to the nearest available school, is that it?

A. Not always the nearest available school, but available

from the standpoint of space or seating them.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

19

Q. And in the case of negroes, they would be assigned

to the nearest available negro school, and the case of

whites they would be assigned to the nearest available

white school in terms of space, isn’t that right? A. If

space is available, that is correct.

Q. Now, have you ever discussed with the Board [28]

the policy of assigning teachers to schools on basis of

race and color!

Mr. Leverett: Your Honor, we would like to

object to this testimony on the grounds that it is

irrelevant and immaterial to the issues in this case.

It has no bearing whatsoever on the issues here.

The Court: Well, what was the question? I

didn’t get the question.

Mrs. Motley: I asked him whether he had ever

discussed with the Board the policy of assigning

teachers to schools on the basis of race and color?

The Court: I think, perhaps, that’s admissible.

The Witness: No.

Q. You never have discussed it with the Board? A.

No.

Q. But the teachers and principals and other pro

fessional personnel are assigned on the basis of race, aren’t

they? That is, only whites are assigned to white schools

and only negroes are assigned to negro schools, isn’t that

right ?

Mr. Leverett: Your Honor, for the purpose of

the record, I would like to note an exception.

The Court: That is the same objection you made

just now?

Mr. Leverett: Yes, sir.

[29] The Court: I ’ll overrule your objection.

The Witness: Now, would you give me the ques

tion, please?

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—-Cross

20

Mrs. Motley: Mr. Reporter, may we have the

question!

The Court Reporter: (Reading) “ But the

teachers and principals and other professional per

sonnel are assigned on the basis of race, aren’t

they! That is, only whites are assigned to white

schools and only negroes are assigned to negro

schools, isn’t that right!”

The Witness: Yes.

Q. Mr. McCormac, do you recall that your deposition

was taken by the plaintiffs’ counsel on December 7th,

1962! A. Yes.

Mrs. Motley: We would like to offer Mr. Mc

Cormac’s deposition into evidence for the admis

sions contained therein.

The Court: Well, you will have to be specific

on that, I should think.

Mrs. Motley: Well, we have asked him a num

ber of things which he has admitted in here. It

would take a long time to read it, your Honor.

The Court: We have got all of this week and

nest week.

Mrs. Motley: Pardon me!

[30] The Court: We have got all of this week

and next week too. I want to get what’s the pur

pose of it.

Q. Well, let me ask you some additional questions

which avoid us having to put this into evidence; you re

consider those school zone lines each year, don’t you, to

determine what the capacity of a particular school is going

to be! A. Yes. We at least look into it to determine

whether or not it is necessary to redefine areas.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

21

Q. So, that, every year, prior to the beginning of a

school year you look at the total school population and

assign students to schools, don’t you, according to those

maps? A. Yes.

Q. How long does that take each year? A. What aspect

of it?

Q. The assignment of students to schools? A. Well,

I can’t answer specifically on it, but it requires several

weeks of detail study to determine how many students

can be taken care of in each school and from which area

they should come and what staff should be assigned to

the schools, and some members of my staff have been on

it a number of weeks each year.

Q. When you say a number of weeks, how many weeks?

A. I can’t say specifically, because we try, I [31] am

sure they try to keep records as they go, as they have

information, and it may run along for several months,

but actually on detail study I would say that it would

require at least four or five weeks to do the detail study.

That is an estimate on it.

Q. And have you done that for September, 1963? A.

We have already done that. We have looked into it.

Q. What time of the year do you usually do that? A.

That is usually started around January or February,

some time along then.

Q. Now, you have converted schools from negro to

white schools in Savannah and the county recently, have

you not? A. I don’t get the question.

Q. You have converted schools from negro to white

youths in Savannah and the county recently, have you

not? A. Yes.

The Court: You have done what? I didn’t get

it.

The Witness : Well, I would like to get her ques

tion again.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

The Court: Well, ask it again.

Q. You have converted schools from white to negro

youths in the county and the City of Savannah recently,

[32] have you not! A. We did one for the current year.

Q. What school was that? A. Anderson Street.

Q. Why was that school converted to negro youths?

A. Well, it happened that the negro student population

around the building justified the use of the building, and

the white enrollment had dwindled.

Q. What did you do with the white students remain

ing there? A. They were sent to the nearest white schools.

Q. You have also converted other schools in the past

the same way, haven’t you? A. I do not recall but one,

which was converted at the immediate time from a divi

sion of instruction building to a negro school. It had

formerly been a white school.

Q. How about the Barnard Street School? A. That is

the one to which I refer.

The Court: Was that the case which I tried,

the Barnard School?

The Witness: Yes, sir, it was.

Q. Have you ever converted any schools from negro

to white youths? A. Not during my administration.

[33] Q. Now, do you have any technical high schools

in Savannah? A. We have what we call an area trade

school, and we are building two schools that will be called

Technical Vocational Schools that will serve areas in the

state beyond our county. We have the Harris Area Trade

School.

Q. Is that negro or white? A. Negro.

Q. Do you have a similar white trade school? A. Not

that we call a trade, school at the moment. We do have

a vocational school.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—-Cross

23

Q. What is the name of that one? A. Savannah Voca

tional School.

Q. And the negro school again was what, called what?

A. Harris Area Trade School.

Q. Was that devoted to trades only, or were other

subjects taught there ? A. Well, if you call nursing a trade,

nursing is taught, electronics, and masonry.

Q. What other trades? A. Shoe repairing. I believe

there is a home making course there. I do not have a

listing of all the offerings that are there.

[34] Q. What do you teach at the, white vocational

schools ?

Mr. Leverett: May it please the Court, we would

like to object to this line of testimony on the grounds

that it is irrelevant and immaterial.

The Court: Well, it might be releyant. I will

let you ask it. Go ahead and answer the question.

The Witness: I don’t have a listing of all the

offerings, but we have the electronics course in the,

Savannah Vocational School. We have offered,

periodically, upholstering. We have—I believe there

are, others in the home making areas maybe that are

not always offered. That is one of the things the

offerings change from time to time, and for the

moment I cannot give you a listing exactly of all

of it.

Q. Now, you were subpoenaed to bring the papers show

ing the differences in the curriculum between negro and

white schools, were you not? A. Yes.

Q. Did you bring those? A. I do not have a document

showing differences. I have a document showing courses

approved for all schools because our high schools are

comprehensive schools and the programs are the same

D. L. McCormac—■for Plaintiffs—Cross

24

from the standpoint of administration through the elemen

tary grades.

[35] Q. Well, the papers which you brought, do they

list the curriculum of the Area Trade School of the Harris

School! A. No, I do not have anything on the vocation,

but I have a listing of subjects for all schools that is the

basis for the development of a program in the individual

high school, which would apply to all high schools.

Q. Now, do you have a person who supervises the negro

schools under your jurisdiction! A. Not as a separate

supervisor of negro schools.

Q. What does he do! A. I say we do not have a super

visor of negro schools. We have several staff members

that work in different capacities with the different schools.

Q. What negro staff members do you have on your

staff! A. From the standpoint of supervision, we have

a supervisor that works in the secondary level.

Q. What is his name! A. Hardwick.

Q. What is his full name! A. Mr. Clifford Hardwick.

Q. Well, what is his title! A. Supervisor. It ’s come

out as specialist, and [36] maybe that is all right, but he

is in a supervisory capacity.

Q. Well, now, what white schools does he supervise!

A. None.

Q. What other negroes do you have on your staff! A.

We have two elementary supervisor’s positions but because

we, have moved those two people at different times, one

last year and this year, we moved them to principalship,

and we have vacancies there at the moment.

Q. You have two vacancies! A. Yes.

Q. You do not have any negro supervisors at the

elementary schools at the present time! A. The person

who was the supervisor moved to a principalship, which is

a promotion. She is simply carrying out her commitments

until the end of the year, at which time the position will

be tilled.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

25

Q. What other negroes do you have on your staff!

A. We have, maybe we need to define staff, but we have

two visiting teachers.

Q. What do they do? A. Well, they are supposed to

visit the homes of students, where they are problems in

school and absences and so forth. At one time they were

generally considered to be [37] attendance teachers.

Q. Do they visit in any white homes? A. No.

Q. Do you have any other negroes on your staff? A.

We have some itinerant librarians, because we don’t have

full time librarians in the elementary schools, but we do

have a few people that devote their time, and they are

trained librarians, serving more than one school each to

set up the libraries and make them useful.

Q. How many negroes do you have in such capacity?

A. I believe that it is two at the present time.

Q. Do they service any white schools? A. No.

Q. Do you have any other negroes on your staff? A.

From the standpoint of operating out of the central office,

no.

The Court: What do you mean by that?

The Witness: Well, it comes back, your Honor,

to the question of definition, I would consider a

principal on the staff. It is a question of definition,

and I certainly would consider the principal of a

school as being on the staff, and we have those prin

cipals, and it is just a matter of definition as to

whether we want to say the immediate staff of

the Superintendent or the staff in the division of

instruction, or what-not.

[38] Q. Well, let me ask you this: We went over in

stances where negroes passed white schools. Do you know

of any instances where whites passed negro schools? A.

I am sure they do. I am sure that happens.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

26

Mrs. Motley: I believe those are all the questions

for this witness, your Honor.

The Court: All right, do you gentlemen wish to

cross-examine. Who is going to do the cross-

examining.

Mr. Leverett: I understand we are entitled to

cross-examine our own party on matters brought

out.

The Court: No, you can’t do that. He is an

adverse witness. That is right, is it not?

Mrs. Motley: Yes, sir.

The Court: You cannot cross-examine your own

witness. You can call him as your witness at the

proper time. See if I am correct, gentlemen. I don’t

think he would be entitled to cross-examine an ad

verse witness. He is your witness. She put him

up as an adverse witness, and I don’t think you

have a right to cross-question your own witness,

when he is an adverse witness. You can put him

up later.

Mr. Leverett: I am not arguing with the Court

except to state my position.

The Court: All right.

Mr. Leverett: It is my understanding, may it

please [39] the Court, that where a party is called,

one of the parties are called as an adverse party, that

his own counsel has a right to propound to him

questions in the nature of cross-examination on mat

ters brought out.

The Court: When you put him up as your wit

ness, yes. That is my recollection. What do you

gentlemen say? If you all will quit talking among

yourselves and answer my question. Let’s go ahead,

gentlemen. Answer my question, if you will. If

you didn’t hear it, I would not mind repeating it,

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs— Cross

27

of course. Is he entitled to cross-examine this wit

ness!

Mr. Leonard: It is my understanding of the

rule that he has a right to do so to the extent of

matters brought out by the witness.

The Court: All right, if you agree to it. What

do you say!

Mrs. Motley: I think that is right, your Honor.

The Court: All right, if both sides agree to it.

It is up to you all. Go ahead. I sure have been

committing a lot of errors around this court.

Mr. Leverett: Your Honor, I believe I read a

recent decision to that effect.

The Court: All right, if both sides agree to it.

That’s up to them.

[40] Cross-examination by Mr. Leverett:

Q. Mr. McCormac, refreshing your recollection, do you

recall whether or not Mr. Bartlett, Mr. Shuman and Mr.

Wiggins were on this committee to study the matter of de

segregation that you referred to on your examination in

chief! I was simply trying to ask you to refresh your

recollection as to the composition of the committee! A. I

am not certain about that.

Q. Isn’t it true that Committee held several meetings,

public meetings! A. The particular Committee, I am not

sure.

Q. Do you recall whether or not any public announce

ments were ever made by the Savanah School System with

reference to meetings that that Committee would hold! A.

Yes.

Q. Do you recall what the substance of those announce

ments were! A. That the Board Committee would meet

with various groups wanting to be heard.

Q. Do you recall whether or not such meeting was held!

A. Such meetings were held.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

28

Q. Do you know approximately how many? A. I don’t,

but possibly three or four. I am not [41] sure.

Q. Isn’t it true, Mr. McCormac, that this Committee

had a meeting scheduled which was postponed or put off

because of the filing of this suit? A. Yes, sir.

Q. In 1962! A. Yes, sir.

Q. In other words, this Committee was still conducting

its hearing and its study when its proceedings were stopped

by virtue of the filing of this suit? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And at that time this Committee had not completed

its study, had it? A. No.

Q. Now, isn’t it true, Mr. McCormac, if you know, but

of course if you don’t know you can’t answer it; but isn’t

it true that not a single one of the plaintiffs in this law

suit ever appeared at any of these Committee meetings to

assist the Board in solving this problem? A. I could not

answer that, because I was not at the meetings.

Q. Now, with respect to the application of these pupils

to attend the, Pulaski School, Mr. McCormac, of your own

knowledge, isn’t it true that the reason no further proceed

ings [42] were had with respect to that was that the parents

themselves indicated that they really didn’t want to pursue

their applications? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Will you explain to the Court the reason, or detail

the reason, why this determination was made? A. Yes,

because of re-assignment of pupils in what is known as the

Staley Heights Area while a new school was being built,

or planned to be built and is now under construction. While

it was being constructed we had to redistribute and elim

inate, as far as possible, double sessioning of students, and

these students were unhappy about their assignment.

Q. They were being assigned from one existing negro

school to another? A. Yes, and had attended one of those,

but some were moved to another negro school, which is a

brand new school.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

29

Q. Wasn’t it determined that they really wanted to stay

at the school they then were attending? A. Yes.

Q. And that this application to Pulaski was simply for

the purposes of emphasizing their discontent with being

reassigned from a negro school which they were then at

tending? [43] A. Yes.

Q. Now, Mr. McCormac, do you handle the assignment

of pupils in the Savannah-Chatham County School System?

A. I do not do the detail work. The total program, when it

has been worked out by members of the staff, is submitted

to me for approval.

Q. For that reason, then, you are not familiar with all

the aspects of these attendance area maps and procedure

as to how this is done, is that correct? A. Yes.

Q. Now, Mr. McCormac, have any applications ever

been made, to your knowledge, from negroes in the Grove

Point area seeking transfer to any other school? A. I know

of none.

Q. What about with respect to Wilmington Island? A.

I know of none.

Q. What about with respect to Montgomery Eoad? A.

I know of none.

Q. Or any of the other areas that counsel for the plain

tiffs questioned you about? A. I know of none.

Q. Now, these two vacancies in the negro supervisors

that you referred to, are they in the process of being filled,

or is some one from the Board seeking to fill those [44]

vacancies? A. Yes.

Q. Will they be, filled? A. So far as I know, they will be

filled, yes.

Q. Now, Dr. McCormac, you were questioned about the

processing or the preparation of your attendance areas, has

all of that already been done for the 1963 and 1964 school

year? A. Yes, it has been done tentatively.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs— Cross

Mr. Leverett: That’s all.

30

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

The Court: All right.

Cross-examination by Mr. Pittman:

Q. How many years did you spend as a classroom

teacher! A. I was principal and teacher for four years,

and then I taught in high school four years.

Q. As teacher, were the problems of discipline directly

under you of your class! A. The four years I taught as a

teacher, full time teacher, I was responsible for the dis

cipline in my groups. Prior to that time I had supervision

over the entire school.

Q. How long have you been in a capacity as a [45]

supervisor over classroom teachers! A. Well, as a prin

cipal, for twenty years, and as a superintendent approxi

mately eight altogether.

Q. I believe you bear the title of Doctor, do you not!

A. No, sir, I am not entitled to that title.

Q. Mr. McCormac, how long have you been in a position

which would enable you to exercise discretion or power with

respect to segregation or integration or separation of races!

A. I would say that I have never been in that position.

Q. What body exercises that power or performs those

duties! A. I would consider it a function of the Board of

Education within the framework of law under which it

works.

Q. Has it been your function to recommend to the Board

policies and plans under which you believe to be to the best

interest, or which you believe to be, to the best interest of

the white children and the colored children! A. Yes.

Q. And have you made such recommendations to your

Board! A. May I ask if you are referring to a particular

type of organization!

[46] Q. No. In general! A. In general, the welfare of

people.

31

Q. Do you believe it to the best interest of tbe negro

children and white children that they be mixed in the

schools? Would you have recommended that? A. I would

not, if I knew that it was not in the power of the Board

to do anything about it under law.

Q. If the Board had such power, would you have rec

ommended it? A. Would I have recommended a particular

type of thing?

Q. Yes? A. I consider the problem we are dealing with

one of policy-making with the Board having the function

of making poliey. I certainly have not been in position,

say, up to the moment of making a recommendation for any

change with regard to this problem.

Q. You know all the schools and you know many of the

people in the schools? A. Yes.

Q. And you know the different types and characters and

traits of the various groups in Savannah, do you not? A.

I would say I know a good many of those.

Q. In your opinion, is the present system, by [47] racial

schools, most advantageous to whites and blacks ? A. That

would be merely stating an opinion.

Q. Yes, sir. That is what I am asking you for. You

are qualified. Give us your opinion. You are qualified to

give an opinion on that subject? A. As I view it and have

worked with it and considered the development of the pro

gram for both races and strength and so forth it would be

my answer that I believe that it is best as it is.

Q. In all of your years of experience as a teacher and

supervisor have you ever observed any injury to a colored

child by reason of that child not being permitted to mix

and mingle with white children in schools? A. I know of

no concrete evidence to that effect.

Q. You recognize, do you not, that the petition filed by

the plaintiffs in this case makes this allegation in the first

paragraph of paragraph 9:

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs— Cross

32

“ Plaintiffs, ancl members of the class which they rep

resent, are injured by the refusal of defendants to cease

operation of a compulsory biracial school system in Cha

tham County.”

Are you familiar with that allegation? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Is that true or untrue? [48] A. I have no evidence

to show that it is true.

Q. In your opinion, is it untrue? A. So far as my

knowledge goes, yes.

Q. I read you another allegation of that same para

graph :

“ The plaintiffs, and members of their class, are, injured

by the policy of assigning teachers, principals and other

school personnel on the basis of the race and color of the

children attending a particular school and the race and

color of the person to be, assigned.”

Do you know of any injury suffered by the plaintiffs

or the members of their class as the result of the policy of

assigning white teachers to the white schools and the col

ored teachers to the colored school? A. No.

Q. On the contrary, is it not your opinion that such

assignment of colored teachers to colored schools and white

teachers to white schools is to the best interest of the

negroes and to the best interest of the white people? A.

That is my personal belief, yes.

Q. Further on in this same paragraph, I would like

to read this allegation:

“ The injury which plaintiffs and members of

their class suffer as a result of the operation of a

compulsory biracial [49] school system in Chatham

County is irreparable and shall continue to irrep

arably injure plaintiffs and their class until enjoined

by this Court.”

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

33

Are you familiar with that allegation! A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you know of any injuries the plaintiffs and mem

bers of their class have suffered as a result of the mainte

nance of separate schools for the white children and the

colored children in Savannah and Chatham County? A. No.

Q. Would you deny that allegation, the theory of it?

A. I have no proof that that is true.

Q. In your opinion, is it untrue? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, you said you had a number of meetings to dis

cuss the question of desegregating the schools of Savannah.

At any of those meetings was it pointed out to you, or by

counsel, that it was necessary for the NAACP counsel to

prove that the colored children were injured by segregation

before they would be entitled to an injunction in this case ?

A. I believe the meetings to which you refer were meetings

which I didn’t attend.

Q. Well, at any meetings of your school hoard was [50]

it not pointed out that it was necessary for the NAACP

to prove that segregation injured colored children in order

to entitle them to an injunction? A. I do not recall the

Board taking that position.

Q. You mean that you have come here to try this case

without any witnesses besides yourself to disprove this

allegation? A. I was subpoenaed to come as a witness.

Q. I will ask you, Mr. McCormac, in your opinion,

what would happen in a classroom in Savannah, if it was

balanced as to races ? We will take the fifth or sixth grade

class. First, let me ask you this: What proportion of the

school population in Savannah is negro? A. Approximately

38 percent, between 38 and 40 percent.

Q. And the, balance is white? A. Yes, sir.

Q. State, as your opinion, what problems would arise if

negro children and white children were mixed in the ratio

of 38 to 62?

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

34

Mrs. Motley: We object to that question, Your

Honor. It is speculative as to what problems would

arise, if?

The Court: I think you would have, to rephrase

your question, because it is speculative as to what

is or might [51] happen in the future. Anything

in the past might be admissible, anything that he

knows, but anything that might happen in the future

would be speculative.

Q. From your experience as a school man and your

experience with problems of discipline, do you have any

knowledge what would result, or might result, from the

mixing of children of different colors in the same school

room? A. I certainly don’t think I am competent as an

expert to estimate in detail as to what would occur under

those conditions.

Q. In your answer in this case, page 7, you state that

you are cognizant that great social, economic, psychological

and other influences were, at work both for and against seg

regation, is that true? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you also say on the same page, page 7, that the

school board had before it evidence of such developments

in other communities leading—at least on two occasions the

intervention of the armed forces of the United States—it

recognizes that such development would not be conducive

to the education and welfare of all children of whatever

race and creed? Do you subscribe to that statement? Is

that a true statement? A. I would like, if you will, to give

me the, last part of your statement again. I am sorry?

[52] The Court: That is the Board of Educa

tion’s statement, isn’t it?

Mr. Pittman: That is the Board of Education,

but answered by him as well.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

35

Q. Are you not a defendant in this ease? A. Yes.

Q. So, in your answer, you have before you, the evidence

of such developments in other communities, and I will read

you: ‘ ‘ leading at least on two occasions to the intervention

of the armed forces of the. United States, and it recognizes

that such a development would not be conducive to the

education and welfare of all children of whatever race and

creed.” Do you recognize that statement? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Is it true? A. Yes, I agree with that.

Q. So, either you or the members of the school board

felt qualified to make an allegation as to what would happen

or might happen if integration of the races took place, is

that true? A. Yes, that is true.

Q. In the Savannah School System you are obeying the

state law with reference to compulsory education? A. Yes,

sir.

[53] Q. I f you have a serious disciplinary problem with

respect to a boy or a girl, what do you do? Do you expel

them? A. The principal has the right to suspend tem

porarily, but only the Board of Education has the right to

expel.

Q. If serious problems of discipline should arise as a

result of racial conflict, and those could not he solved on

the teacher level or the principal level, and you had sources

of constant irritation, that could he settled by the Board

of Education dismissing those responsible for it?

Mrs. Motley: We object to that, Your Honor, it

is irrelevant as to whether the schools are segregated

or integrated?

The Court: What do you say, Mr. Pittman?

Mr. Pittman: It is to show, if Your Honor

please, that under the present system in Savannah

there is no way that the conflict that might arise

from integration could he effectively controlled.

The Court: I will let you go ahead on that.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

36

Q. Further on in your answer, Mr. McCormac, you

said this: ‘ ‘ Defendant Board has never received an appli

cation from either a negro or white student for transfer or

assignment to a school of the opposite race,” is that true?

[54] A. I know of no such a case.

The Court: Read that again. I didn’t catch it.

Mr. Pittman: The Defendant Board has never

received an application from either a negro or a

white student for transfer or assignment to a school

of the opposite race. ’ ’ Is that true ?

The Witness: With the exception of the testi

mony with regard to the group brought out earlier.

Q. Well, what about these particular plaintiffs in this

case, Stell and others? Have any of those children ever

made application to the school board for transfer or as

signment to a white school? A. Not to my knowledge.

Q. The first notice that you had of the desire of those

particular plaintiffs was when the petition was served upon

you? A. Yes.

Q. Mr. McCormac, in your opinion, do negro children

learn better, or would they learn better, from negro teachers

than from white teachers?

Mrs. Motley: That’s irrelevant, Your Honor.

We object to that.

The Court: I think it would be irrelevant for

this reason: He never has had any, so he wouldn’t

know of his own [55] knowledge.

Mr. Pittman: I know, Your Honor, but I don’t

ask him for his knowledge. I asked him his opinion

as a school man. We believe he qualified as an expert.

The Court: He did do that, yes. I tell you what

I am going to do: I am going to admit all the evi

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

37

dence, which I think is pertinent at this time, and

then when we get through with all the evidence, then

yon can make your motion, which I presume you will

make, to eliminate all of this, and then I will hear

you. I want to hear the full case, if you will. When

they get through with their evidence, if there is any

evidence that you think should he thrown out, why,

then you get up and make your motion, and then

you will have your record clear. I think that is the

best way to handle it.

Q. The school hoard appears in this case, seemingly,

without taking sides with the white or the colored, is that

true! Is that your posture! You appear as a neutral

body! A. I think that would have to be defined. I certainly

would say that the Board of Education has the interest

of both races at heart and would like to see the best pos

sible program of education for each race.

Q. What are the education aims of the Chatham County

School System! A. I probably could give you a list of

things we [56] hope to achieve through the educational

system.

Q. Is it all directed toward the welfare of the children!

A. Yes.

Q. It is directed toward the welfare of all the children!

A. Yes, from the standpoint of the philosophy of the staff

and the administration, yes.

Q. If, in your opinion, it would be best for the negro

school children to be taught and supervised by negro school

teachers, would you recommend that policy! A. It would

be conjecture with me. I don’t have evidence that such

would be true and therefore would not face the issue of

making such a recommendation.

Q. Do you know why the schools in Chatham County

are segregated! A. Well, I know that the State of Georgia

until early 1961 and back for ten years behind that, at any

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

38

rate, would not permit the mixing of the races in the school

and continued to contribute to the financial support of the

program.

Q. Isn’t it true, Mr. McCormac, that segregated schools,

a segregated school system, is now maintained by your

board and by you in order to provide the best educational

[57] opportunities possible for both races! A. I can simply

say that seems to me, as I evaluate it, to be the desire of

the Board of Education and the Administrative Staff, and—

Q. —is that exercise based upon the considered judg

ment for the best interest of the children! A. That cer

tainly would be my appraisal of the thinking.

Q. If you believed it best for negroes and whites to

congregate them in schools, would you recommend that!

A. In my own approach to any educational problem and

coming around to the point of readiness to make a recom

mendation, I would certainly say that I would want a lot

of evidence pro and con, and I think for me to answer that

could be answered in only one way, and that is if I was

convinced that a thing is good then I should point it out

as something that I feel is good.

Q. Have you ever found any evidence that it was good

to congregate them in school together! A. I have not had

the experience with it.

Q. Do you know of any evidence or experience of any

city like Washington, D. C., or any other city where it is

to the benefit of the colored and the white children to con

gregate them rather than to segregate them! [58] A. I

know of no conclusive evidence.

Q. Is not the action of your Board based somewhat

upon experience and observation! A. It has, of course,

experience with the segregated system and is of the opinion

that is better, evidently.

Q. I believe your answer says this: “ No formal action

has ever been taken by the board (since the date you men

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

39

tioned a few minutes ago) and the defendants contend that

the Defendant Board has not adopted by custom or other

wise any so-called biracial system.” Do you recall that

allegation! A. Yes.

Q. You don’t mean by that that the biracial system that

exists in Savannah does not exist with your approval and

that of your Board of Education! A. My interpretation

of this statement simply is in the period of time cited it

has not definitely restated its policy with regard to it.

Q. On page 8 you allege this: That any school system

and locality over which it has jurisdiction for educational

purposes they present an independent factual picture,”

is that correct! A. Yes.

Q. That your school system and the locality over which

it has jurisdiction for educational purposes present an

[59] independent factual picture.” Is that true! A. Yes,

I would think so.

Q. Do you feel that you and your school hoard are

qualified to pass upon and act upon the independent factual

pictures that exist in Chatham County! A. Well, I think

it is a competent group. Our Board of Education, I think,

to do that, it should take the, position it has, that it would

study it and get opinions from various groups and thoughts

of various groups before coming to a point of determina

tion.

Q. Now, you say, in the last part of your answer, on

page 9, that none of the students—you say, nor has any

of its students been denied a proper and adequate education

irrespective of race or creed and it does not desire that

such progress be interrupted or unduly disturbed. What

do you mean by unduly interrupted or unduly disturbed!

A. Well, it means the present organization, the basis for

organization seems to us to be sound for the time because

we, believe, or I do, as Superintendent, I believe that the

program of education is gradually and in many ways

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Cross

40

faster developing strength and that for both races every

effort is being made within the realm of our finances to

strengthen both programs with no differentiation in our

out-look toward it from the standpoint of race.

[60] Mr. Pittman: Your Honor, we, reserve the

right to call Mr. McCormac hack later on as our

witness.

The Court: All right, any other questions?

Mrs. Motley: Yes, Your Honor.

Recross Examination Ry Mrs. Motley:

Q. Mr. McCormac, I believe you testified that the filing

of this suit cut off certain committee hearings being con

ducted by the board on de-segregation? A. Yes.

Q. Is that your testimony? A. Yes.

Q. Now, who was conducting those hearings at that

time? A. A committee of the Board of Education.

Q. Who were the members of that committee? A. I

can recall only the Chairman of the committee.

Q. Who was that? A. Mr. Shelby Myrick, Jr.

Q. Is he still Chairman of the Committee? A. He is no

longer a member of the board.

Q. Wasn’t that why the hearings were cut off? [61]

A. What do you mean?

Q. It was not because of the filing of the suit. It was

because Mr. McCormac left the board, wasn’t it? A. Mr.

Myrick, you mean?

Q. Myrick, I am sorry? A. It was not because Mr.

Myrick left the board.

Q. Well, why were the hearings cut off? A. Well, when

the suit was filed the hearings were discontinued because

it was to be thrown into court.

Q. And you never attended any of these hearings? A.

No, sir.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Recross

41

Q. Do you know how many were held! A. No, I men

tioned three or four, but I do not know exactly.

Q. Now, you indicated that you knew that the negro

parents, who applied for admission to the Pulaski School,

desired not to pursue that application through. Now, how

did you know all of that about the parents and their appli

cations? A. I read the letter that was written on behalf

of the parents in which it was stated that this was not an

application to integrate the school.

Q. What did the letter state? A. It indicated that it

was a protest because of moving their children from one

school to another.

[62] Q. Who wrote the letter? A. I do not recall the

name of the person.

Q. Was there more than one name signed to it? A. It

seems that one person was signing for the group, but I am

not sure of that. It may have been signed by more than one

person.

Q. Where did you see that letter? A. Well, it came

through my office.

Q. When you say it came through your office, was it

mailed to your office? A. I am not sure now whether it was

the original or a copy made and put on my desk.

Q. Now, had that letter been received when their appli-

tion was turned down? A. As I recall the letter came in

before definite action was taken, and I believe I testified

that the Board never did take action on it, and I do not re

call, but it was some days following their appearance at the

school that the letter came in.

Q. Now, has the hoard ever authorized you or any per

son under your jurisdiction, such as the person in charge of

assigning the students, to admit negroes to white schools?

A. No, not to my knowledge.

Q. Have you ever discussed with the teachers and [63]

principals of the Chatham County School system the deseg

regating of the schools? A. No.

D. L. McCormac—for Plaintiffs—Recross

42

Q. Do the negro and white teachers meet separately for

in-service training programs and other programs! A.

Ususally, yes, for their general meeting. We have some

joint committees and our monthly staff meeting of princi

pals and supervisors and directors—is a meeting for all.

Q. Well, how about your in-service training program for

teachers, are they integrated or segregated? A. As a rule

they are segregated. We have joint committee working on

different phases of the program.

Q. Now, as to the Superintendent of the Public Schools

of Chatham County, you are the Chief Executive Officer of

the Board, are you not? A. Yes.

Q. And your primary duty is to carry out the policy

established by the board, is it not ? A. Yes.

Q. Now, the negro and white teachers, do they have to

meet the same qualifications for employment in the Public

School System of Chatham County? A. Yes, and they are

on the same salary schedule.

[64] Q. You have already testified, I believe, that the

curriculum in the elementary schools and the junior high

schools and the senior high schools are the same for both

negro and white schools, is that correct ? A. So far as that

can be made. If you interpret the term ‘ ‘ curriculum ’ ’ in its