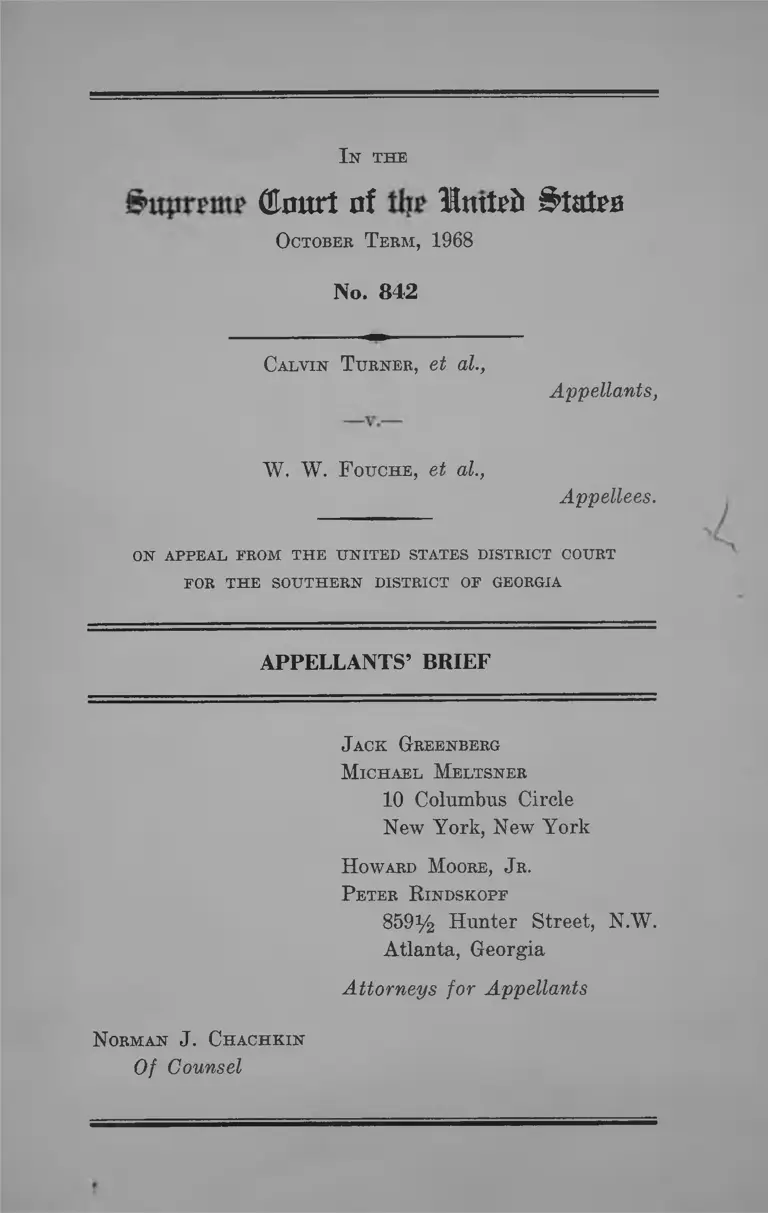

Turner v. Fouche Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Turner v. Fouche Appellants' Brief, 1968. 49d9e702-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d971fff7-7e19-4b2c-9679-b717443a8fdc/turner-v-fouche-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

OInurt of llnttjefn t̂at̂ o

October Term, 1968

No. 842

Calvin Turner, et al.,

W. W. F ouche, et al.,

Appellants,

Appellees.

ON a p pe a l from t h e u n it e d st a te s distric t court

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Jack Greenberg

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

H oward Moore, J r.

P eter R indskopf

859^ Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

Norman J. Chachkin

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinion Below ................................................................. i-

Jnrisdiction ...................................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 3

Questions Presented......................................................... 4

Statement .......................................................................... 4

A. Initiation of This Litigation ............................. 4

B. District Court Proceedings ............................... 5

C. Background of This Litigation......................... 8

D. The Selection of Jurors ....................................... 14

E. Selection and Duties of School Board Members 20

Summary of Argum ent...................................................... 23

A e g u m e n t

I. Statutory Standards Which Govern Georgia

Jury Selection Are Unconstitutionally Vague

and Permit Exclusion of Negroes From Jury

Service in Violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitiition of the United States .. 25

II. Georgia Constitutional and Statutory Provi

sions for Selection of School Board Members

Operate in Taliaferro County to Dilute Negro

Participation in the Selection of Board Mem

bers in Violation of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth,

and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United S ta te s ............................................ 38

u

PAGE

III. Georgia’s Prohibition of Membership on Connty

Boards of Education to Non-Freeholders Vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment...................... 48

Conclusion..................................................................................... 55

A ppendix

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved la

Table oe Cases

Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U. S. 203

(1963) ............................................................................ 54-55

Allen V. State Board of Elections,----- U. S . ------ , 37

U. S. L. Week 4168 (March 3, 1969)............................ 41

Anderson v. Georgia, 390 U. S. 206 (1968) .................. 25

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 (1964) ............ ......... 50

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U. S. 500 (1964) .... 52

Baggett V. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964).......................... 34

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186 (1962) ............................. 41,49

Board of Public Instruction of Duval Co., Fla. v. Brax

ton, 326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir., 1964) ............................. 46

Board of Supervisors v. Dudley, 252 F. 2d 373 (5th Cir.

1958) .............................................................................. 34

Bond V. Floyd, 385 U. S. 116 (1966) ............................. 49, 50

Bostick V. South Carolina, 386 U. S. 479 (1967) ........... 25

Brown v. Allen, 344 U. S. 433 (1953) ........................... 36-37

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .... 47

Brunson v. North Carolina, 333 U. S. 851 (1948) ........... 37

Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 (1952) .............. 34

Carr v. Montgomery County (Ala.) Board of Educa

tion, 253 F. Supp. 306 (M. D. Ala. 1966) ................. 46

Ill

PAGE

Cassell V. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 (1950) ......................... 37

Cipriano v. City of Houma, 286 F. Supp. 823 (E. D. La.

1968), probable jurisdiction noted, 37 U. S. L. Week

3275 (Jan. 14, 1969), 0. T. 1968, No. 705 .................. 51

Cline V. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U. S. 445 (1927) .............. 34

Cobb V. Georgia, 389 U. S. 12 (1967) ............................. 25

Colegrove v. Green, 328 U. S. 549 (1946) ...................... 41

Commercial Pictures Corp. v. Regents of University of

New York reported with Superior Films, Inc. v. De

partment of Education, 364 U. S. 587 (1954) .......... 34

Davis V. Mann, 377 U. S. 678 (1964) ............................. 41

Davis V. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S. D. Ala.), aff’d per

curiam, 336 U. S. 933 (1949) .....................................34,42

Dowell V. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W. D. Okla., 1965), atf’d 375 F. 2d 158 (10th Cir.

1967), cert, den., 387 U. S. 931 (1967) ...................... 46

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) .......34, 52

Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 383 U. S. 339 (1966) .............. 34

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339 (1960) .......36,40,41,

42, 43,44

Green v. New Kent County Board of Education, 391

U. S. 430 (1968) ........................................................... 46

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U. S. 12 (1956) ........................... 49

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, Va.,

377 U. S. 218 (1964) ...................................................... 46

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 (1965) ........... 52

Hadnott v. Amos,----- U. S .------ , 37 U. S. L. Week 4256

(March 25, 1969) .................................................40,42,43

Hague V. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 (1939) ......................... 26

IV

PAGE

Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U. S. 663

(1966) ................................................... 24,43,49,50,52,53

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 H. S. 242 (1937) ...................... 34

Hill V. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 (1942) ................... .............. 32

Jones V. Georgia, 389 IT. S. 24 (1967) ............................. 25

Kelly V. Altlieiiner, 378 F. 2d 483 (8tli Cir. 1967) ....... 46

Keyishian v. Board of Eegents, 385 IJ. S. 589 (1967) .... 52

Kramer v. Union Free School District No. 15, 282 F.

Supp. 70 (E. D, N. Y. 1968) ........... ......................... 51, 54

Landes v. Town of Hempstead, 231 N. E. 2d 120, 20

N. Y. 2d 417, 284 N. Y. S. 2d 417 (1967) ..................51,53

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939) ....................42,43,44

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U. S. 145 (1965) ....26, 30, 34,

35, 37,45

MacDougall v. Green, 335 U. S. 281 (1948) .................. 39

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184 (1964) ................ 53

N.A.A.C.P. V. Alabama, 377 U. S. 288 (1964) ................ 52

N.A.A.C.P. V. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) .............. 51,52

Neal V. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1881) .......................... 37

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 (1951) ................ 26

Nixon V. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 (1927) .......................... 40

N. L. E. B. V. Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock

Co., 308 U. S. 241 (1939) .............................................. 45

Pierce v. Ossining, 292 F. Supp. 113 (S. D. N. Y. 1968) .. 51

Eahinowitz v. United States, 366 F. 2d 34 (5th Cir. en

banc 1966) .................................................................... 31

PAGE

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. 533 (1964) .......... 24,39,40,41

Rice V. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (4tli Cir. 1948) .............. 43

Sailors v. Board of Education of Kent County, 387

U. S. 105 (1967) .................. -.............................. 39,40,42

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U. S.

110 (1948) ...................................................................... 45

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 (1939) ...................... 52

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ......................40,43

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 (1960) ......................... 52

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U. S. 398 (1963) ..................51,52

Sims V. Baggett, 247 F. Supp. 96 (M. D. Ala.

1965) ...................................................................... 39,42,44

Sims V. Georgia, 389 U. S. 404 (1967) ......................... 25

Slaughter House Cases, 83 U. S. 36 (1873) .................. 43

Smith V. Alhvright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944) ......................42,44

Smith V. Bennett, 365 U. S. 708 (1961) ......................... 49

Smith V. Paris, 257 F. Supp. 901 (M. D. Ala. N. D.

1966) aff’d 386 F. 2d 979 (5th Cir. 1967) .................. 42

Smith V. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 (1940) ......................... 35

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U. S. 301 (1966) 34

State ex rel. Mitchell v. Heath, 34 Mo. 226, 132 S. W.

2d 1001 (1939) ............................................................... 53

Staub V. City of Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 (1958) .............. 34

Sullivan v. Georgia, 390 U. S. 410 (1968) ...................... 25

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461 (1953) .............. 24,42, 43, 46

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 (1945) ...................... 52

Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 724 (S. D. Ga. 1965;

supp. opinion 1966) .....................................1, 9,11,12,47

United States v. Atkins, 323 F. 2d 733 (5th Cir. 1963) .. 34

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 (1943) .............. 50

VI

PAGE

United States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U. S. 81

(1921) ............................................................................ 34

United States v. Logue, 344 F. 2d 290 (5th Cir. 1965) - 46

United States v. Mississippi, 380 U. S. 128 (1965) ....... 30

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U. S. 319

(1947) ............................................................................ 45

United States v. Scarborough, 348 F. 2d 168 (5th Cir.

1965) ............................................................................. 46

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U. S. 1 (1910) 45

West Virginia State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette, 319 U. S.

624 (1943) .................................................................... 51-52

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 346 F.

2d 768 (4th Cir. 1965) ................................................ 46

Whitus V. Georgia, 385 U. S. 545 (1967) .......... 15, 25, 26, 27

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 (1948) ................. 34

Witcher v. Peyton, 405 F. 2d 725 (4th Cir. 1969) ....... 33

WMCA V. Lomenzo, 377 U. S. 633 (1964) .................. 41

Yick Wo V. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ................. 26

T able of S tate C o n st it u t io n a l a n d

S ta tu to ry P ro visio ns

Ga. Code Ann. §2—6801, Art. VIII, §V, para. I. of

Georgia Constitution of 1945 ............................. 5, 6, 20, 48

Ga. Code Ann. §2—6802; Art. VIII, §V, para. II of the

Georgia Constitution of 1945 ..................................... 20

Ga. Code Ann. §24—2501 ................................................ 14

Ga. Code Ann. §32—902 ........................................... 5, 6, 48

Ga. Code Ann. §32—902.1 .................................... 5, 6, 20,48

Ga. Code Ann. §32—903 ............................................ 5,6,20

Ga. Code Ann. §32—905 ............................................ 5, 6

Ga. Code Ann. §32—1116................................................ 54

V ll

PAGE

Ga. Code Ann. §32—1118 ................................................ 53

Ga. Code Ann. §32—1127 ................................................ 53

Ga. Code Ann. §59—101 ........................................ 5, 6,14, 26

Ga. Code Ann. §59—106 ..................5, 6,15, 23, 26, 27, 29, 31

Ga. Code Ann. §59—201 ................................................ 15

Ga. Code Ann. §59—202 ......... ........................................ 15

Ga. Code Ann. §59—306 .................................................. 15

Ga. Code Ann. §59—308 .................................................. 15

Ga. Code Ann. §59—310.................................................. 16

Ga. Code Ann. §59—311 .................................................. 16

Ga. Code Ann. §59—314 .................................................. 16

Ga. Code Ann. §59—315 .................................................. 16

Ga. Code Ann. §59—401 .................................................. 16

Ga. Code Ann. §92—6307 ................................................ 15

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

28 Am. Jur. 2d, Estates §8 ............................................ 48

Atlanta Journal, Feb. 2, 1969 ........................................ 20

Circular No. 6; Educational Research Service (1967) 21

Hearings on S. 1318 before the Subcomm. on Improve

ments in Judicial Machinery of the Senate Comm,

on the Judiciary, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. (1967) ....... 30

Kuhn, “Jury Discrimination: The Next Phase,” 41

U. S. C. Law Rev. 235 (1968) ............................. 30,31,34

Sjunposium on the Griswold Case and the Right of

Privacy, 64 Mich. L. Rev. 197 (1965) ....................... 52

The Congress, The Court and Jury Selection, 52 Va.

L. Rev. 1069 (1966) ..................................................... 30

The Forty-Eight State School Systems (1949) .......... 21

U. S. Code Congressional and Administrative News,

90th Cong., 2nd Sess................................................... 31

I n t h e

Ol0urt sti Btsd̂ s

October Teem, 1968

No. 842

Calvin Turner, et al.,

— V.—

W. W. F ouche, et al.,

Appellants,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FEOai THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOE THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Opinion Below

The opinion of the court below is reported at 290 F.

Supp. 648 (S. D. Ga. 1968) and is set forth in the appen

dix, pp. 397-405d Earlier litigation involving several of

the parties is reported as Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp.

724 (S. D. Ga. 1965; supp. opinion, 1966).

̂Hereinafter cited (A. ).

Jurisdiction

This is an action for injunctive and declaratory relief

in which jurisdiction of the district court was invoked

under 28 U. S. C. '^§1331, 1343, 2201-02; 42 U. S. C.

^§1981, 1983, 1988, 1994, 2000d and 2000e; and the Fifth,

Ninth, Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

The complaint sought, inter alia, to enjoin enforcement

and operation of Georgia’s constitutional and statutory

scheme for the selection of jurors and county boards of

education as in violation of the Constitution of the United

States. A statutory three-judge court Avas convened pur

suant to 28 U. S. C. §§2281, 2284 (A. 18).

The three-judge court determined that it was properly

convened but found “no merit in the three-judge District

Court questions presented” (A. 403). A final judgment and

decree was entered on September 19, 1968 (A. 406-407).

Timely notice of appeal to this Court was filed in the

court beloAv on October 14, 1968. On December 2, 1968,

J-Ir. Justice Black extended the time for filing a Jurisdic

tional Statement to, and including, February 8, 1969. On

February 24, 1969, this Court noted probable jurisdiction

(A. 408). Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant

to 28 U. S. C. §1253.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This action involves the following Georgia constitutional

and statutory Provisions, which are set forth in an ap

pendix infra pp. la - l la :

Article VIII, Section V, paragraph I, of the Consti

tution of the State of Georgia of 1945; Ga. Code Ann.,

§2-6801.

Article VIII, Section V, paragraph II, of the Consti

tution of the State of Georgia of 1945; Ga. Code Ann.,

§2-6802.

Ga. Code Ann. §23-802

Ga. Code Ann. §32-901

Ga. Code Ann. §32-902

Ga. Code Ann. §32-902.1

Ga. Code Ann. §32-903

Ga. Code Ann. §32-905

Ga. Code Ann. i§32-908

Ga. Code Ann. §32-909

Ga. Code Ann. §32-1101

Ga. Code Ann. §32-1118

Ga. Code Ann. §32-1127

Ga. Code Ann. §59-101

Ga. Code Ann. §59-106

Ga. Code Ann. §59-202

Ga. Code Ann. §59-203

Ga. Code Ann. §59-318

Ga. Code Ann. §59-319

This action also involves the Thirteenth, Fourteenth,

and Fifteenth

United States.

Amendments to the Constitution of the

Questions Presented

1. Whether statutory standards which govern Georgia

jury selection are unconstitutionally vague and permit the

arbitrary exclusion of Negroes from jury service in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States ?

2. Whether the Georgia system of selection of school

board members by the county grand jury operates to dilute

Negro participation in the selection of the board in viola

tion of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments ?

3. Whether Georgia’s prohibition of service on school

boards to non-freeholders violates the Fourteenth Amend

ment?

Statement

A. Initiation of This Litigation

On November 14, 1967, Calvin Turner, a registered

Negro voter residing in Taliaferro County, Georgia, and

his daughter, a student in the public schools of the county,

brought this action against members of the county board

of education, jury commission, and representative grand

jurors. A Negro father of six school age children, ŵ ho is

not a freeholder, Avas permitted to intervene as a plaintiff

(A. 72, 73). The complaint alleged that appellants, and

others similarly situated, were denied rights guaranteed

by the federal Constitution by the operation of Georgia

statutory and constitutional provisions which authorize the

selection of school board members and jurors.

Appellants contended, inter alia, that: (1) they had been

denied an opportunity to serve as jury commissioners,

grand jurors, and traverse jurors on account of race (com

plaint paras. 11(c), 11(d)); (2) they had been denied on

account of race an opportunity to participate in the process

of selecting the officials who administer the public schools

of Taliaferro County (complaint, para. 11(a), (h)); and

(3) they had been denied on account of poverty, and the

requirement that school board members be freeholders,

the opportunity to actually serve as board members (com

plaint 11(b)) (A. 7-14).

The complaint sought injunctive and declaratory relief

as to the offending provisions of state law: Ga. Code Ann.

§§2-6801; 32-902, 902.1, 903, 905; 59-101, 106; that mem

bership on the board of education and jury commission

be declared vacant; that a receiver be appointed to operate

the public schools pending selection of a constitutionally

acceptable board; that a special master select members

of the grand and petit juries; and that ancillary damages

be awarded (A. 16-17). Because appellants sought injunc

tive relief restraining the enforcement of state statutes

and constitutional provisions, a three judge court was em

panelled and the State of Georgia permitted to intervene

(A. 18, 65).

B. D istrict Court Proceedings

The district court held two hearings before it rendered

its decision. At the first, January 23, 1968, the court found

that the

evidence indicated and the court announced then and

now so finds that Negroes were being systematically

excluded from the grand juries through token inclu

sion. . . . The grand jury situation was such that

Negroes had little chance of appointment to the school

board (A. 399).

Counsel for the appellees were directed “to familiarize

defendants with the provisions of law relating to the pro

hibition against systematically excluding Negroes from the

jury system” (A. 399). Appellees were also informed by

the court that it would be appropriate if two Negroes were

appointed to the school board (A. 252).

At the second hearing, February 23, 1968, the court was

informed that the county jury list had been revised in

light of the court’s oral pronouncement that the master

list was illegally composed, and that on February 16, 1968,

the county grand jury had confirmed one Negro and one

white man to fill two school board vacancies (A. 265-69).

On August 5, 1968, the district court entered its opinion,

stating the issues as follows;

The thrust of the complaint is that the Negroes have

no voice in school management and affairs in that

there are no Negroes on the school board. It is con

tended that Art. VII [sic], §V, U of the Constitution

of the State of Georgia of 1945, Ga. Code Ann.,

§2-6801, and Ga. Code Ann., §§32-902, 902.1, 903 and

905, all having to do with the election of county school

boards by the grand jury, are unconstitutional under

the equal protection and due process clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment and under the Thirteenth

Amendment, both facially and as applied by reason of

the systematic and long continued exclusion of Ne

groes and non-freeholders as members of the Board

of Education of Taliaferro County, Georgia, and on

the selecting grand juries. The same contention is

made with respect to the Georgia laws regarding the

appointment of and service as jury commissioners.

Ga. Code Ann., §§59-101 and 106 (Ga. Laws 1967,

p. 251, Vol. 1). Here again unconstitutionality in ap

plication is asserted on the basis of systematic exclu

sion of members of the Negro race from service as

jury conunissioner. Unconstitutionality is claimed also

by reason of the alleged uncertainty, indefmiteness,

and vagueness of the standards set forth in each of

the statutes (A. 398).

The district court concluded that the grand jury list,

“as revised”, is not unconstitutional and that state consti

tutional provisions and statutes governing jury and school

board selection are not unconstitutional on their face or as

applied: “The facts showed systematic exclusion in the

administration of the grand jury system prior to the revi

sion but this resulted from the administration of the system

and not from the constitutional provision and statutes

under attack” (A. 403).

The court also concluded that the requirement that mem

bers of the school board be freeholders is not unconstitu

tional :

“There was no evidence to indicate that such a quali

fication resulted in an invidious discrimination against

any particular segment of the community, based on

race or otherwise” (A. 403).

On September 19, 1968, the court entered a final judg

ment, in conformance with its opinion, upholding the va

lidity of all the challenged state statutes and constitutional

8

provisions and. denied relief/ other than to enjoin jury

commissioners from “systematically excluding Negroes

from the grand jury system” (A. 406).

C. Background of This Litigation

Consideration of appellants’ claims requires some fa

miliarity with general characteristics of Taliaferro County

and earlier litigation between several of the parties.

According to the 1960 Census county population ;

Number Percent

White 1,273 37.8

Negro 2,096 62.2

White (over 21) 877 47.3

Negro (over 21) 979 52.7

White (over 18)“ 917 46.0

Negro (over 18) 1,073 54.0

WTiile the exact number of registered voters of each

race in the county was not known it was generally agreed

—and the district court found—that Negroes and whites

each constituted 50% of those registered (A. 368-69, 390,

399).

* The court declined in its discretion to consider a single-judge

claim for ancillary money damages in the amount of $500,000 to

compensate plaintiffs for past deprivations and denials of federal

rights. ̂ A prayer for attorney’s fees was denied. Earlier the court

had dismissed the complaint as to three defendants named indi

vidually as representative grand jurors (A. 71).

® 1960 Census of population, Table 25, pp. 12-83, Table 27, pp

12-130, and Table 28, pp. 12-148.

“ Of the 910 persons of school age in the county, 15.2% were

white males; 13.2% white females; 39.6% non-white males and

32.1% non-white females. Ibid.

All of the teachers and children who attend public

schools of the county are Negro although the superinten

dent is white (A. 21, 38-39; 24, 47, 52). The five-man

county school hoard had not had a Negro member in the

memory of board members until one was appointed as a

consequence of this litigation (A. 23, 46); none of the

white board members themselves had children attending

the public schools (A. 23, 47, 20, 38). The county jury

commission has been composed of whites for at least the

last 50 years (A. 20, 38).

In 1965, Negro citizens of Taliaferro County, including

appellant Turner, brought an action in the district court

against the circuit solicitor, county sheriff, county attorney,

superintendent of schools, and county board of education,

alleging, in summary, that by misuse of their offices and

by lodging unfounded criminal charges they had conspired

to deny the rights of county Negroes to free speech and to

a desegregated education. A three-judge court was con

vened and found that a public assembly protesting segre

gation had “set off a chain of events resulting in a flagrant

unconstitutional application of the statute proscribing the

disturbance of divine worship.” Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F.

Supp. 724, 727 (S. D. Ga. 1965). The court also described

the tactics emploj^ed by whites to avoid desegregation of

the schools:

There are onlj ̂ two schools in the county; Murden

which is populated by Negroes, and Alexander Steph

ens Institute which was populated by whites during

the last school term. It appears without dispute that

Alexander Stephens Institute has been closed since

the beginning of this school term on or about Sep

tember 1st, and that all white children in Taliaferro

10

County are attending school in adjoining counties

with most being transported on Taliaferro County

school buses. The role that the school superintendent

and the school board are alleged to have played in

the conspiracy is to have secretly and covertly ar

ranged for all the white children to leave the county

for school in other counties so as to eliminate the only

white school available to 87 Negro children who sought

transfers to a desegregated school. The transfers were

sought pursuant to a plan of desegregation filed with

the Health, Education and Welfare Department. The

transfer applications of these Negro students had

never, up until the time of hearing, been considered

by the superintendent and the school board. Instead,

the school superintendent concluded that some of the

applications for transfer were not bona fide and there

upon called upon the school board attorney, defendant

Richards, to conduct an investigation as to whether

some of the applications were forged . . .

At any rate, Mr. Richards took over the investiga

tion from this point forward. And it must be noted

in considering this phase of the case that the form of

application for transfer was illegal in the light of

several opinions of this court that notarization of the

signature of the applicant or of the parents or guard

ian may not be required [citing cases].

Defendant Richards obtained what he considered to

be sufficient evidence to have Plaintiff Calvin Turner,

a former teacher in the Negro school of Taliaferro

County, indicted for forgery. We view that evidence

with considerable scepticism in the light of the illegal

transfer applications and other evidence submitted at

the hearing . . .

11

There was some evidence that the unrest on the part

of the Negro plaintiffs stemmed in part from the fact

that the superintendent of schools refused their re

quest for a gymnasium or for use of the only school

gymnasium in the county which was assigned to the

white school. There was some evidence relating to

the refusal to rehire several Negro school teachers

but this was not developed to the point of showing

that this resulted from the alleged conspiracy (255

F. Supp. at 727, 28).

The court determined that the white school superin

tendent “with at least the knowledge, if not the help, of

tlie school board” {Id. at 728) knew that the white schools

would he closed. Negroes, however, were not advised.

The decision “if not kept secret, was at least not pub

licized” and “The superintendent arranged during the

month of August for her own son to transfer” to a school

in another county {Ibid.). Although Negro transfer appli

cations had been refused, white applications to attend

school in adjoining counties were granted and Taliaferro

piihlic school buses used to transport them {Ibid.).

In response to these facts, the court placed the school

system in receivership and appointed the state superin

tendent of schools as receiver. He was instructed to sub

mit a plan (i) to end the illegal expenditure of public

funds use to transport whites to adjoining county schools

and (ii) to grant the right of 87 Negro applicants for

transfer to adjoining counties where white children had

been transferred {Id. at 730). The solicitor, county sheriff

and county attorney were enjoined from prosecuting

Negroes including appellant Turner under “spurious”

12

indictments for disturbing divine worship, as well as on per

jury and forgery charges. The court also enjoined plain

tiffs from disturbing schools and interfering with school

buses carrying students to adjoining counties (Ibid.).^

The formerly white school was ultimately reopened as an

elementary school and the formerly Negro school as a

high school {Id. at 731-34), but white children who'had left

the public schools of the county, rather than attend them

on a desegregated basis, never returned. They either a t

tended a newly created private school or continued to

attend school in other counties (A. 47-9, 51-2, 354-59, 397).®

At this time, Negro parents believed that they could not

alter continued operation of a segregated school system,

and that the white school board, several of whose present

members Avere also serving in 1965, was hostile to the needs

and desires of the students actually attending the public

schools (A. 214-217). Kepeated attempts by appellant

Turner and members of the Voters League, a civic group,

to appear at school board meetings Avere unsuccessful.

The time of scheduled meetings Avas changed Avithout

public notice, contrary to law (A. 343-47; infra pp. 5a, Ga)"

' On May 20, 1966, the court entered a supplementary opinion

in which it granted the receiver’s motion for discharge after con

cluding that Negro children who Avished to attend school in ad

joining counties did so and that adjoining counties had given

notice they would take no children, Avhite or Negro, for the school

term 1966-67. Administration of the schools Avas returned to the

Taliaferro board of education.

® During the 1966-67 term, there were 458 Negro children in th4

public school system and 72 white children attending a local priA'ate

school.

'A t the second hearing, appellees admitted that timely notice

of the schedule change had not been published but also alleged,

throAigh the introduction of hearsay evidence, that such failure

was inadvertent (A. 345-346).

13

and the time also could not he determined despite attempts

to obtain information from the hoard chairman (A. 188-

90, 206-07). llTien reached by phone his attitude was

brusque and unhelpful (A. 210-11). A registered letter

sent to him went unanswered (A. 188-89).

One ;^arent, Mrs. Mary Allen, told the district court her

experience with the school system. She was invited to

visit her child’s classroom by the Negro principal. After

the white superintendent observed Mrs. Allen in class,

the classroom teacher was told by the principal: “Miss

Hadden, discontinue this class until the parents (sic)

leave” (A. 225). Mrs. Allen subsequently asked to be

allowed to organize a parent-teacher association in order

to “have some kind of communication with the teacher”

(A. 229). The principal of the high school informed her

that this could not be done because the superintendent

had refused permission (Ibid.). When a group of parents

attempted to appeal that decision, and present other griev

ances, the board abruptly adjourned a meeting without

responding to any of the complaints. The course of the

meeting was described at tr ia l:

“Judge Bell: How long did you stay in there?

The W itness: About ten minutes.

Judge Bell: And then they moved that meeting

be adjourned?

The Witness: That’s right, and put the heater out.

They had the heater on and a gentleman put the

heater out and we walked out. He started putting

the lights out too and we walked out and then they

closed the door.

Judge Bell: Did they give you an answer at all as

to your complaints?

14

The Witness: No answer.

Judge Bell: No answer?

The Witness: No sir.

Judge Bell: Have you had one since then?

The Witness: No, sir” (A. 233).^

Mrs. Allen stated her opinion of the school system as

follows:

“You can’t even talk with the teacher, and can’t go

and sit in the classroom and can’t talk to the board,

can’t talk to anybody, nothing about your problems”

(A. 234).

Shortly after her experience with the school board she

moved to another county for the benefit of her child. Her

purpose in moving, she said, was “to get communication”

(A. 234).

D. The Selection of Jurors

The challenged selection process for the grand jury and

school board members begins when a judge of the Superior

Court, elected by the voters of a six county circuit,” ap

points six jury commissioners from among “discreet per

sons” in the county for a six year term, Ga. Code Ann.,

§59-101. At least biennially, these commissioners compile

from the official registered voter’s list used at the last pre

ceding election a jury list of “intelligent and upright citi-

® At the first hearing Judge Bell stated: “ . . . The court con

strues that paragraph of the petition to mean, based on the evi

dence, that the First Amendment has been suspended in Taliaferro

County to the extent that citizens can’t assemble before their

officials and petition for their grievances. That’s been the evi

dence” (A. 214-215).

” Ga. Code Ann. §24-2501.

15

zens of the county.” Ga. Code Ann., §59-106.“ IVhile

Georgia law permits 18 year olds to vote only persons over

21 are eligible for jury service, Ga. Code Ann., §59-201.

After compiling the jury list the commissioners select

a “sufficient” number of the most “experienced, intelligent

and upright citizens”," not exceeding two fifths of the

whole, to serve as grand jurors." The judge of the Su

perior Court draws from the grand jury list so selected

not less than 18 nor more than 36 names to serve on a venire

for the next term of court, and the sheriff summons the

prospective jurors, Ga. Code Ann., §§59-203, 206. After

excusals, a grand jury panel consisting of not less than 18

nor more than 23 persons is drawn from the venire (A. 311-

314, 322), Ga. Code Ann., §59-202."

§106 also provides that: “If at any time it appears to the

jury commissioners that the jury list so composed, is not a fairly

representative cross-section of the intelligent and upright citizens

of the county, they shall supplement such list by going out into

the county and personally acquainting themselves with other citi

zens of the county, including intelligent and upright citizens of

any significantly identifiable group in the county which may not

be fairly represented thereon.”

” Prior to 1967, the commissioners were instructed to select

as jurors upright and intelligent persons from the books of the

Tax Receiver. Ga. Code Ann., §59-106 (superseded). The tax

books from which the prospective jurors were selected were segre

gated by race. Ga. Code Ann. §92-6307. See Whitus v. Georgia,

385 U. S. 546, 549 (1967).

The requirement that Grand Jurors be the most “experienced,

intelligent and upright citizens” was added to the statute in 1968

subsequent to trial in this ease.

Under Georgia law grand juries have a number of powers in

addition to indictment and appointment of school board mem

bers. They may recommend that individual tax returns be cor

rected, Ga. Code Ann. §59-306; inspect the list of voters, Ga. Code

Ann. §59-308 and the offices, papers, books and records of the

16

At the January 23,1968 hearing evidence was introduced

showing that on the jury list most recently composed, 56

out of a total of 328 traverse jurors (or 17%) were Negro

(A. 182-83, 399), and 11 out of 130 on the grand jury list

(or 8.5%) were Negro {ibid.). The district court concluded

that systematic exclusion of Negroes was taking place and

condemned the practice:

“We all know what systematic exclusion is, and when

there is as many registered Negro voters in a county

as whites and you have 130 to 11 on the grand jury,

why that’s systematic exclusion, and that will have

to be corrected” (A. 251).

The court adjourned the hearing after informing defend

ants of the court’s power to enjoin racial discrimination

if a remedy were not devised (A. 251, 254-255, 399).

At the beginning of the February 23, 1968 hearing ap

pellees’ counsel presented a report to the district court

which stated that on January 26, 1968, the judge of the

Superior Court ordered the jury commissioners to revise

clerk of the Superior Court, the ordinary and the county treasurer

or depository for conformance with their duties, 6a. Code Ann.

§59-309. The jury may appoint citizens to inspect the affairs of

the ordinary or other authority having charge of county affairs,

the clerk of the Superior Court, county treasurer, tax collector,

school superintendent, sheriff, and all other county ofSces, Ga.

Code Ann. §59-310. Persons appointed by the grand jury to

inspect have full power to take control of the various offices, to

compel the attendance of witnesses, and hear evidence of fraud

and the non-performance of official duty, Ga. Code Ann §59-311.

The jury is also obliged to inspect the sanitary conditions of jails

and to make recommendations as to their proper operation, Ga.

Code Ann. §59-314; to inspect all public buildings and property of

the county and report their condition, Ga. Code Ann. §59-315; and

to appoint a committee to inspect every orphanage, sanitorium, hos

pital, asylum, and similar facilities for the purpose of ascertaining

what persons are confined and by what authority, Ga Code Ann

§59-401.

17

both the grand and traverse jury lists “to comply with the

oral pronouncement” of the district court (A. 266). This

order was filed with the clerk of the Superior Court but

not generally publicized. By word of mouth, however, some

persons did hear of it and requested not to be put on the

jury list (A. 280-81). Over forty whites but only two or

three Negroes were not placed on the list as a result of such

requests not to serve (A. 89, 402). Appellants’ counsel ob

jected to the report on the ground that it was hearsay and

that neither he nor appellants had been informed of the

revision or furnished with the report in advance of the hear

ing but the district court received it in evidence (A. 269-

72; cf. 262).

According to the report the commissioners considered

“each and every name” (A. 77, 266, 67), on a list of 2,152

registered voters. When they were not familiar with

Negroes, they inquired of three Negroes who w'ere “brought

in to work with us in order to assist in excluding people

from the list” (A. 275, 76). They consisted of an insurance

agent, his daughter-in-law and a person who was employed

by the board of education but whose position the chairman

did not know. These Negroes were not, however, appointed

jury commissioners {Ibid).

The Commission eliminated the following numbers of

persons from the voters list for the reasons stated:

Poor health and over-age................................. 374

Under 21 years of a g e .................................... 79

Dead ............................................................... 93

Persons who maintained Taliaferro County

as a permanent place of residence but

were most of the time away from the

county ............................................................ 514

18

Persons who requested to be eliminated

from consideration ..................................... 48

Persons about whom information could not

be obtained ................................................ 225

Persons of both the white and Negro race

who were rejected by the Jury Commis

sioners as not conforming to the statu

tory qualifications for juries either be

cause of their being unintelligent or

because of their not being upright

citizens ....................................................... 178

Names on voters lists more than once......... 33

Total ............................................ 1,544

(A. 77-78, 267).

These disqualifications left 608 names on the list. The

commissioners determined that fewer than 608 names were

needed, alphabetized the remaining names, and discarded

every other one. Of the 304 persons on the list, 113 (37%)

were Negro and 191 (63%) were white (A. 78, 267). From

tlie 304 they drew 121 names by lot and put those names

on the grand jury list (A. 78, 268). Forty-four (36%)

of 121 persons on this list were Negroes (A. 79, 268).

Of 32 persons initially drawn from this list for the grand

jury, 9 (or 28%) were Negro. Of the 23 persons actually

selected to serve on the grand jurv, 6 (or 26%) were

Negro (A. 79, 268-69).'^

The judge begins with the first name on the list of 32 and

hears requests for excuses. After persons granted excuses are

eliminated, he chooses the first 23 names on the list (A 322)

19

Two months after the February 23, 1968 hearing, the

jury commissioners reported additional information con

cerning the revision to the district court and corrected

errors in earlier figures furnished. They found that 2,252

names, instead of 2,152, were on the voters list and that

eliminations were made for the following reasons:

Total Number Negro

Category of Names Names

Under 21 ........................... 81 71

Dead ................................. 94 Unknown

Kequested ......................... 43 2

No Information ....... 226 Unknown

Poor health and/or old

age ................................. 482 191

Away ................................. 533 263

Miscellaneous .................. 179 167

Elected Officials and then

Known Duplications .... 8 -0-

Not Alternately Selected 302 106

(A. 89).

The district court only partially accepted the fact stated

in this report. The court found that 171 of the 178 persons

excluded by reason of character and intelligence (as op

posed to 167 of 179) were Negro and that 3 of 43 persons

excluded by request (as opposed to 2 of 43) were Negro

(A. 402; cf. 89).

The commission chairman testified concerning the re

vision. Wlien asked what was meant by the standard of

“intelligent,” the chairman first stated it would be some

one capable of interpreting proceedings in the courtroom

but then that the standard used was whether persons could

20

read or write (A. 283). He later testified: “ we made

the overall consideration of uprightness in people who

were dependent and reliable and honest. We did not say

pick out so and so and say they were unintelligent”

(A. 284). Pie also testified that an “upright” citizen was

one who had a “good reputation, people who were honest

and of good character” (A. 284). While some persons

were omitted from the list because they had a criminal

record the Chairman had no idea of the number or the

offenses which constituted grounds for exclusion (A. 285).

For example, he did not know whether any persons were

found to lack a sufficiently upright character because of

having been convicted of a traffic violation (A. 287).

E. Selection and Duties of School Board Members

Under Georgia law, the county grand jury selects as

school board members five freeholders “of good moral

character, who shall have at least a fair knowledge of the

elementary branches of an English education and be favor

able to the common school system”, Ga. Code Ann.

§§32-902.1, 903. The operation of this system is statewide,

except in those counties altering it “by local or special

law conditioned upon approval by a majority of the quali

fied voters of the county voting in a referendum thereon,”

Ga. Code Ann. §2-6802. Approximately 94 of Georgia’s

school boards are chosen by county grand jury, Atlanta

Journal, p. 7-A (Feb. 2, 1969). Each member is elected

for a four year term, Ga. Code Ann. §2-6801; §32-902, but

the board files vacancies, other than which result from ex

piration of a term, until the next grand jury meeting, at

which a successor is chosen, Ga. Code Ann. §2-6801.

21

The board is required to meet between the 1st and the

15th of each month at the county seat for the transaction

of business pertaining to the public schools. Ga. Code

Ann. §32-908 provides that the board “shall annually de

termine the date of the meeting” and shall “publish same

in the official organ for two consecutive weeks following

the setting of said date; Provided further that said date

shall not be changed oftener than once in twelve months.”

The Georgia grand jury selection method is unusual. A

1949 study concluded that the prevailing method of selec

tion in the United States is by public vote. While several

states where the county is the basic unit of government,

have appointive boards (by the Governor in Maryland; the

General Assembly in North Carolina; School Trustee Elec

toral Boards in Virginia; and County Courts in some coun

ties in Tennessee) Georgia was apparently the only state

where appointment was by the grand jury. The Forty-

Eight State School Systems (Council of State Governments,

1949), pg. 59, Table 23, p. 196. A more recent survey of

477 school boards of various sizes and locations revealed

that 82.2% were elected. See Circular No. 6, Nov. 1967,

Educational Research Service (Washington, D. C.).

At the January 23, 1968 hearing in the district court the

presiding judge remarked that the absence of Negroes on

the board of education “simply will not do” and stated

pointedly that it would be wise if the school board filled

its vacancies with “two outstanding Negroes . . . if you

don’t want to do that we will know that on the 23rd [of

February]” (A. 252). Two vacancies existed on the school

board at the time of the hearing. The superintendent of

schools attended the hearing and upon her return informed

the school board of the presiding judge’s remarks (A. 350,

22

351)2'' Two days later, the county hoard of education met

and appointed one Negro and one white to the board.

Shortly thereafter these choices were ratified by the grand

jury (A. 268, 339)—apparently without the public notice

required by law (A. 348-349, 351). No Negroes attended

the meeting at which the Negro board member was selected

although Negroes had attended board meetings in the past

(A. 347-348). Nor did the board discuss the qualifications of

Casper Evans, the new Negro member, for board mem

bership (A. 351-52). He was “put in nomination and

elected” (A. 353). No elfort was made to give notice of

the appointment meeting to any parent or the plaintiffs in

this suit (A. 348, 353).

Appellant Turner testified that Mr. Evans was a distant

relative of his who was about 71 or 72 years of age and

retired (A. 374). Mr. Evans had only attended school to

the third or fourth grade (A. 375) and had often stated

that he did not feel like going out in public any more or

to attend community meetings, because of his age (A. 374-

75). Turner believed that Evans was unrepresentative of

the Negro community (A. 381, 385), and that if Negroes

had been afforded an opportunity to choose, they would

have selected someone far more qualified educationally,

and otherwise, to serve (A. 385).̂ ®

"W hen the superintendent was asked what efforts she had

made to keep the public school system from becoming all Negro

she replied that “the schools are open to all the children of Talia

ferro County” (A. 355-56).

He stated; “Mr. Casper Evans was taken from the lower

bracket, the very lowest bracket of those persons who have at-

tamed a education” (A. 387). “I submit, said Mr. Turner, the

pwple in that community . . . knew nothing about the election

of Mr. Evans, and . . . this certainly wouldn’t be the democratic

process” ( A. 381).

23

Summary of Argument

I.

Georgia confers an opportunity for arbitrary and dis

criminatory jury selection on jury commissioners by au

thorizing them to exclude persons they do not believe are

“intelligent and upright” citizens. Neither Ga. Code Ann.

§59-106, nor the practice of the all-white Taliaferro County

commission, supplies a meaningful definition of the statu

tory language. Vague standards have often been con

demned in other spheres of governmental activity precisely

because of their tendency to vest this sort of undue dis

cretion in officials to deprive citizens of their constitutional

rights. Eequirements of specificity are at least as neces

sary to a juror selection system, for although blatant acts

of discriminatory exclusion may be prevented by injunc

tion, the more subtle forms of the evil, such as discrimi

natory limitations of the number of Negro jurors, will

survive as long as Negroes can be declared ineligible on the

basis of subjective and intangible character judgments.

(In this case the opportunity to discriminate was employed

by exclusion of 171 Negroes and only 7 whites as not be

ing “intelligent and upright”.) The necessity of striking

Georgia’s vague selection standards for grand jurors is

heightened by the fact that the grand jurj" selects mem

bers of the county school board—a circumstance which has

resulted in the exclusion of Negroes from board member

ship in a county where all the public school children are

Negro.

24

II.

Georgia law authorizes a multi-layered scheme of selec

tion of school board members which has resulted in the

virtual exclusion of Negroes from board membership. Lim

itations on the right of Negroes to participate in the se

lection of officials “who control the local county matters

that intimately touch [their] lives,” Terry v. Adams, 345

U. S. 461, 470 (1953), violate the Constitution. When such

limitations dilute the weight of Negro votes they may be

redressed according to the standards of Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U. S. 533 (1964), but other remedies, reflecting the spe

cial need of Negroes to unimpaired political rights, may

also be employed. In Taliaferro County, dilution of the

power of Negroes to elect school board members has re

sulted in a segregated school system and in making the

Negroes virtually subject to the commands of the whites

in regard to the education of their children. The district

court erred by not declaring a school board selection system

which so operates unconstitutional and by failing to con

sider relief which would eliminate diminution of Negro

voting power for school board members.

III.

Georgia’s constitutional and statutory requirement that

county school board members must be freeholders violates

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

for it discriminates against the poor and landless far more

than the poll tax condemned in Harper v. Virginia Board

of Elections, 383 U. S. 663 (1966). The freeholder restric

tion reflects an obsolete view of the attributes of real

25

property ownership, it hears no reasonable relationship

to any legitimate governmental objective, and it retards

citizen participation in what may be the most important

unit of local government. While the mischief caused by such

a prohibition is plain, Georgia has not suggested any “com

pelling interest” in the prohibition of non-freeholders from

board membership which would begin to meet the exact

ing standards of equal protection applied when the right

to vote is involved.

A R G U M E N T

I.

Statutory Standards Which Govern Georgia Jury Se

lection Are Unconstitutionally Vague and Permit Exclu

sion of Negroes From Jury Service in Violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

In Wliitus V. Georgia, 385 U. S. 545, 552 (1967) this

Court condemned Georgia statutes which injected race into

the selection of jurymen because they provided an “oppor

tunity to discriminate,” see also Sims v. Georgia, 389 U. S.

404 (1967); Cohh v. Georgia, 389 U. S. 12 (1967); Jones v.

Georgia, 389 U. S. 24 (1967); Anderson v. Georgia, 390

U. S. 206 (1968); Sullivan v. Georgia, 390 U. S. 410 (1968);

Bostick v. South Carolina, 386 U. S. 479 (1967). In 1967,

the Georgia legislature changed the source of prospective

jurors from racially designated tax digests to voter lists,

but retained the “opportunity to discriminate” condemned

in Whitus, supra, by reenacting the vague and subjective

character “standards” of juror eligibility challenged here

26

—that all jurors be “intelligent and upright”.” In addi

tion, the “opportunity” for racial selection inherent in this

statutory language was “resorted to” (385 U. S. at 552)

by Taliaferro County jury commissioners, both before and

after this litigation commenced, a circumstance entitled

to considerable weight in considering the constitutionality

of the challenged statutory scheme, Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U. S. 145 (1965); Niemotko v. Maryland, 340

U. S. 268 (1951); Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 (1939);

Tick Wo V. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886). Although the

number of white and Negro voters in the county is equal,

until suit was filed only 11 of the 130 persons on the grand

jury list were Negro (A. 399) and during the court-ordered

revision of the jury list, approximately 96% (171 out of

178) of the persons disqualified by the commissioners as

not “intelligent and upright citizens” were Negro (A. 402).

It is apparent that the vagueness of the challenged provi

sions at the very least serves as a convenient mask for

what is plainly racial discrimination.

Georgia law creates several levels in the jury selection

process at which virtually unlimited discretion is dele

gated to persons possessing appointive powers. First, the

judge of the Superior Court, an official elected by the

voters of six counties, is authorized to appoint as county

jury commissioners anyone he deems to be “discreet”, Ga.

Code Ann. ^fifi-lOl. Although Negroes constitute a ma

jority of the county population, all the “discreet” persons

selected by Siiperior Court judges to be jury commission-

In 1968, the Legislature amended Ga. Code Ann. §59-106 to

require that grand jurors be “the most experienced, intelligent

and upright citizens” of those chosen as jurors.

27

ers over the years have been white. Second, the discretion

of the jury commissioners is such that they may disqualify

from service as jurors anyone they find not to be an “in

telligent and upright citizen” and anyone for grand jury

service who is not among “the most experienced, intelli

gent and upright”, Ga. Code Ann,, §59-106. Section 106

also provides that if at any time “it appears to the jury

commissioners” that the jury list is not a fairly representa

tive cross-section of the “intelligent and upright citizens”

of the county, they shall supplement the list by “going out

into the county and personally acquainting themselves with

other citizens of the county, including intelligent and up

right citizens of any significantly identifiable group in the

county which may not be fairly represented thereon.”

(Emphasis supplied.) Thus the statute first provides

the jury commissioners with “the opportunity to discrimi

nate” ; then charges the very same persons with the power

to determine by use of the same subjective standard

whether in fact the opportunity “was resorted to” {Whitus,

supra, 385 U. S. 552) and should be remedied.'®

The Taliaferro jury commissioners concede that eligi

bility under §106 is determined by their “personal” opin

ion. "Wlaen asked to “describe in full and complete detail

the standards applied” the commissioners responded by

denying the existence of uniform criteria defining “intel

ligent and upright” :

'® The language of 6a . Code Ann. §59-106 instructing the jury

commissioners to find additional jurors from readily identifiable

groups is less of a caveat than a camouflage. As long as “intelligent

and upright” remains a part of the jury selection statute, the

jury commissioners will have a built-in excuse for failing to in

clude Negro citizens on the juries.

28

We did not detail or fix any standards in making

a determination as to who is upright and intelligent.

As previously stated, this determination is based

upon our knowledge either personal or through in

vestigation of these persons being considered (A. 36).

When asked to state “in full and complete detail, the pro

cedures followed in selecting persons for the grand jury

list” the commissioners stated that there “was no set pro

cedure for this selection process” :

From the official registered voters list which was

rised in the last preceding general election, as a group

we selected a fairly representative cross-section of

the upright and intelligent citizens of the county.

There was no set procedure for this selection process.

AVe did it as a group (A. 36).

The manner in which the commissioners confronted their

constitutional and statutory duty to select a cross-section

of the community is illustrated by the fact that until after

the court-ordered revision of the illegal jury lists the

commissioners professed total ignorance as to whether

discernible groups in the community were represented:

Q. 6. How many members of the present grand jury

list are members of the Negro race? A. 6. AVe do not

know.

Q. 7. How many members of the present grand jury

list are w’hite females? A. 7. AVe do not know.

Q. 8. How many members of the present grand jury

list are Negro females? A. 8. AÂe do not Imow.

29

Q. 17. Of the names on the voter’s list, how many

are Negroes? A. 17. We do not know.

Q. 18. Of the names on the voter’s list, how many are

white females? A. 18. We do not know.

Q. 19. Of the names on the voter’s list, how many

are Negro females? A. We do not know (A. 30-32,

36, 37).

Even after the revision process was completed, the com

mission had not formulated standards of selection to make

the vague language of §106 more precise. The chairman

testified, for example, that an “upright citizen” Avas one

who had a “good reputation in the community, good

character” (A. 284). As to the term “intelligent”, he

presented totally inconsistent definitions. First, he defined

the intelligent a s :

People who we thought would be capable of inter

preting proceedings that would be going on in the

courtroom (A. 283).

But we asked “what standards did you use,” he replied:

People that could not read nor write to our knowledge.

I don’t think we rejected anyone because you say they

are unintelligent. I mean that—

Judge Bell: You said awhile ago being able to

understand proceedings in court.

The W itness: Yes sir, and we made the overall

consideration of uprightness and people who were de

pendent and reliable and honest. We did not say pick

out so and so and say they were unintelligent.

Judge Bell: In other words, you measured these

people by the standard as to Avhether or not they were

30

capable of serving on a jury and understand what the

duty of a juror was?

The Witness: That’s right, sir (A. 284).

This jury selection scheme—as authorized by Georgia

law and employed by the Taliaferro County Commissioners

—violates appellants’ rights under the Fourteenth Amend

ment. First. As is true with racial discrimination in

voting '̂* (an analogy especially pertinent here in light of

the dual role of the grand jury system see supra p. 20),

excessive discretion in the hands of local officials thwarts

nonracial selection of prospective jurors. Judge Kaufman

merely summarized what is generally recognized when he

told a United States Senate Committee that:

“ . . . long experience with subjective requirements such

as ‘intelligence’ and ‘common sense’ has demonstrated

beyond doubt that these vague terms provide a fertile

ground for discrimination and arbitrariness, even when

the jury officials act in good faith.”

One study of jury selection procedures has concluded that

until character tests are replaced by objective standards

non-racial selection is unlikely: “It is this broad discretion

located in a non-judicial officer which provides the source

of discrimination in the selection of juries.” The Congress,

Condemnation of discretion in the hands of state voting of

ficials is the heart of recent decisions of the Court. See United

States V. Mississippi, 380 IT. S. 128 (1965); Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U. S. 145 (1965).

Statement of Hon. Irving E. Kaufman, Hearings on S. 1318

before the Subcomm. on Improvements in Judicial Machinery of

the Senate Comm, on the Judiciary, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. at 251

(1967). See also Kuhn, “Jury Discrimination: The Next Phase,”

41 U. S. C. Law Rev. 235, 266-82 (1968).

31

The Court and Jury Selection, 52 Va. L. Rev., 1069, 1078

(1966); see also Rabinowitz v. United States, 366 F. 2d 34

(5th Cir. en banc 1966).^^

Second. While character tests such as those contained

in §106 provide a ready opportunity for racial selection,

their “indefiniteness . . . makes it most difficult to prove

that rejection of an eligible juror was the product not of

honest opinion but of racial policy” Kuhn, op. cit. p. 271.

Opinions of uprightness and intelligence primarily depend

on the individual making the judgment. Thus, a commis

sion bent on racial discrimination may do so without check

as long as it is satisfied with limiting the number of

Negroes serving rather than excluding them totally.

Third. Even the fair minded commissioner is likely to

be misled by the shifting and subjective nature of char

acter standards into racial or other arbitrary selection.

The Fourth Circuit made this point forcefully when con

sidering a Virginia statutory scheme similar to that in

volved in this case:

I t should not surprise anyone that an all-white jury

commission guided by a white judge would be unlikely

to find as high proportion of the Negro community

to be “best qualified” as found among white people.

I t is a simple truth of human nature that we usually

find the “best” people in our own image, including,

In recognition of the dangers of subjective selection standards,

Congress passed the 1968 Jury Selection and Service Act, Pub. L.

No. 90-273, 28 U. S. C. §§1861 et seq., abandoning the “key man”

system in favor of “random selections” and “objective criteria

only” in determining juror qualifications. See House Report, No.

1076, Peb. 6, 1968 (to accompany S. 989) set out in U. S. Code

Congressional and Administrative News, 90th Cong. 2nd Sess. pp.

748-63.

32

unfortunately, our own pigmentation. But the danger

is not simply subjective. As a practical matter, in a

society that is still largely segregated, at least socially,

it is obviously true that white people do not generally

have the wide acquaintance among Negroes that they

have among other white people. A failure of either

the judge or the commissioners fully to acquaint them

selves with all those eligible for jury duty can just as

effectively result in racial discrimination as would

conscious and deliberate invidious selection. Indeed,

within the meaning of the Equal Protection Clause,

such a failure has been equated with deliberate and

purposeful discrimination. Rill v. Texas, 316 U. S.

400, 404 (1942).

Achievement of the stated purpose of the judge and

the jury conamissioners to get only the “best qualified

people” was not aided by the existence of any objective

standard that might have been readily applied. The

only direction given by the legislature to the judge

in that regard is that he select from the citizens of

each county “persons 21 years of age and upwards,

of honesty, intelligence and good demeanor and suit

able in all respects to serve as grand jurors * * * ”

These are qualities hard to judge. The standards ap

plied by the jury commissioners were, according to

the oath subscribed by them, no more definite: “We

wull select none but persons whom we believe to be of

good repute for intelligence and honesty” Standards

such as these afford but little guidance to the consci

entious judge and jury commissioner. I t is not un

natural that each may be left with the feeling that he

has discharged his duty when he has subjectively

selected the “best folks” loiown to him.

33

Selection of jurors “must always accord with the

fact that the proper functioning of the jury system,

and, indeed, our democracy itself, requires that the

jury be a ‘body truly representative of the community,’

and not the organ of any special group or class. If

that requirement is observed, the officials charged with

choosing federal jurors may exercise some discretion

to the end that competent jurors may be called. But

they must not allow the desire for competent jurors

to lead them into selections which do not comport with

the concept of the jury as a cross-section of the com

munity. Tendencies, no matter how slight, toward the

selection of jurors by any method other than a process

which will insure a trial by a representative group are

undermining processes weakening the institution of

jury trial, and should be sturdily resisted. {Witcher v.

Peyton, 405 F. 2d 725, 727 (4th Cir., 1969)

Finally, there is an evil inherent in vague character and

intelligence eligibility standards which is no less signifi

cant for it being difficult to prove in any particular case.

It is that “commissioners can easily select only those Ne

groes who behave as Negroes are meant to behave in their

contacts with white society—Negroes who ‘know their place.’

Indeed, it is only natural for southern jury officials to find

lacking in ‘judgment’ and ‘character’ those Negroes who

engage in civil rights activities, who ‘talk back’ to white

employers, or who have hung juries in previoris cases with

racial significance. The usual statutory criteria readily

lend themselves to selection only of ‘safe’ Negroes who will

do what is expected of them in the jury room. The jury

commissioners may consciously exclude all but ‘Uncle

Toms,’ or they may in good faith simply regard other

34

Negroes as lacking in the qualities required of good jurors.”

(Kuhn, op. cit. at p. 271).

It is settled, however, that officials may not be empow

ered to dispense or deny important constitutional rights

in the exercise of a discretion which consists solely of

their own judgment, unguided by statutory or other guide

lines. In other spheres of governmental activity this Court

has declared similar language permitting public officials

to make subjective decisions unconstitutional.^^ Dealing

with voting qualifications imposed by South Carolina

law, similar to those involved here for jury service, this

Court declared in South Carolina v. Katsenbach, 383 U. S.

301, 312-13 (1966):

“ . . . the good morals requirement is so vague and sub

jective that it has constituted an open invitation to

abuse at the hands of voting officials.”

Kequirements of specificity are at least as necessary in

a selection system for jurors. “ [EJxclusion from jury

“Unreasonable charges” United States v. L. Cohen Grocery

Co., 255 U. S. 81 (1921); “unreasonable profits” Cline v. Frink

Dairy Co., 274 U. S. 445 (1927); “reasonable time” Herndon v.

Loivry, 301 U. S. 242 (1937); “sacrilegious” Joseph Burstyn, Inc.

V. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 (1952); “so massed as to become vehicles

for excitement” (a limiting interpretation of “indecent or ob

scene”) Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 (1948); “immoral”

Commercial Pictures Corp. v. Regents of University of New York

reported with Superior Films, Inc. v. Department of Education,

364 U. S. 587 (1954); “an act likely to produce violence” in Ed

wards V. South Carolina, 373 U. S. 229 (1963) ; “subversive per

son” in Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964); “reprehensive

in some respect” ; “improper” ; and outrageous to “morality and

justice” Giaccio V. Pennsylvania, 383 U. S. 339 (1966). See also

Stauh V. City of Baxley, 355 U. S. 313 (1958) ; Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U. S. 145, 153 (1965) ; United States v. Atkins, 323

F. 2d 733, 742-743 (5th Cir. 1963); Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp.

872 (S. D. Ala.) aff’d per curiam, 336 U. S. 933 (1949); Board of

Supervisors v. Ludley, 252 F. 2d 373, 74 (5th Cir. 1958).

35

service . . . is at war with our basic concepts of a demo

cratic society and a representative government”. Smith v.

Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 130 (1940). And when, in addition,

the electoral function of the Georgia grand jury is con

sidered (see stbpra p. 20), the denial of Fourteenth Amend

ment rights by conferral of excessive discretion in the jury

commissioners is plain. There is simply no reason for

the State of Georgia to require that grand jurors who

may vote in its school board elections be “intelligent and

upright” when persons who vote in general elections must

meet no such standard. The school board “voter registrars”,

who in Georgia happen to be jury commissioners, have “vir

tually uncontrolled discretion as to who should vote and

who should not.” Louisia'im v. United States, 380 U. S.

145, 150 (1965). In that case, this Court sustained a lower

court decision holding the state’s voter qualification test,

which required the prospective voter to interpret portions

of the Louisiana or United States Constitutions, invalid

on its face and as applied, under the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments. Basic to the Court’s holding was

the fact that the test “imposed no definite and objective

standards” upon the registrars who were charged with

administering it. (380 U. S. at 152)

Appellants do not contend that the state can set no

standards at all as qualifications for jurors (or school

board electors) but qualifications that the state sets must

be compatible with federal constitutional requirements.

As the record in this case amply demonstrates, there is

no question but that the present indefinite and non

objective standards permit an extraordinary denial of

equal protection: in a county where Negroes are more

than 60 percent of the popxilation and 50 percent of the

36

voters, they make up a disproportionate minority of grand

jurors. By manipulation of the standardless and unre-

viewahle discretion which Georgia has delegated to jury

commissioners, Negroes have been rendered a minority

of the school board electors as surely as though they

had been gerrymandered out of the county. Cf. Oomillion

V. LigUfoot, 364 U. S. 339 (1960).

General injunctions against racial exclusion such as

granted by the district court may be sufficient to prevent

blatant acts of discrimination such as existed prior to

institution of this litigation, but subtler forms will sur

vive as long as tools such as character tests which measure

intangibles remain readily available. At the first hearing

in this case, the district court, in effect, ordered recom

position of the county jury lists on a non-discriminatory

basis. While the result was an increase in the absolute

number of Negroes selected, an overwhelming proportion

(about 96%) of those excluded by the all-white commis

sioners during the revision as not “intelligent and upright

citizens” were Negro. Thus, under the existing statu

tory scheme it may well be possible to eliminate near

total exclusion, but not the racial limitation of Negroes

from the jury rolls. It is not, however, only exclusion

but limitation on the basis of race as well which the Con

stitution prohibits: “Discriminations against a race by

barring or limiting citizens of that race from participa

tion in jury service are odious to our thought and our Con

stitution” (emphasis added).^^ Broivn v. Allen, 344 U. S.

That an unconstitutional limitation of Negroes has taken

place in Taliaferro County is shown by the fact that in compiling

a new list of jurors, the jury commissioners had 304 names (113

Negroes or 37%; 191 whites or 63%) remaining after randomly

discarding half the registered voters not disqualified. One of the

37

433, 470-471 (1953) citing Brunson v. North Carolina, 333

U. S. 851 (1948); Cassell v. Texas, 339 II. S. 282, 286, 287

(1950).