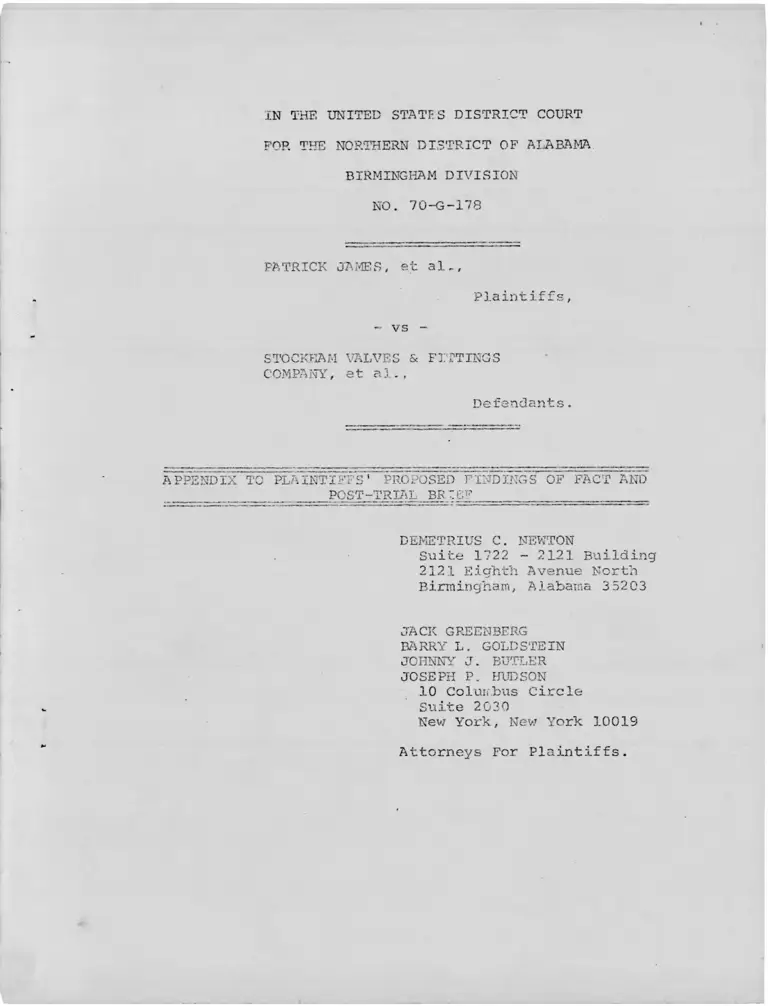

James v. Stockham Valves and Fittings Company Appendix to Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact and Post-Trial Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. James v. Stockham Valves and Fittings Company Appendix to Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact and Post-Trial Brief, 1966. c9cbb410-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d989b8b9-69c4-4ba7-8066-34d9dbee5533/james-v-stockham-valves-and-fittings-company-appendix-to-plaintiffs-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-post-trial-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BIRMINGHAM DIVISION

NO. 70—G —178

PATRICK JAMES, et a 1 - ,

Plaint iffs,

- vs -

STOCKKAM VALVES & FITTINGS

COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants.

APPENDIX TC PLAINTIFFS'

POST-

PRO POSED

?RIAL BRO:

FINDINGS OF FACT AND

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

Suite 1722 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

JOHNNY J. BUTLER

JOSEPH P„ HUDSON

10 Coluii.bus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys For Plaintiffs.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Appendix A, . List of witnesses, position, pages containing

their testimony

Appendix B, Summary of EEO-1 forms, PX13

Appendix C, Employees by Race with Earnings and Seniority

by Seniority Department, PX91

Appendix D, Average and Gross Earrings by Year of Seniority

and by Race, PX95

Appendix E, Job Class of all workers employed at Stockham

as of September 2, 1973, PX94

APPENDIX A

INDEX TO STOCKHAM TRANSCRIPT

Witness Position Pages Testi

Introduction

Coleman 1s Opening

Statement

E. Reeves Sims

Sam Perry Given

Lester Jones

Martin Mador

Patrick James

Jack Adamson

Howard Harville

Otto Carter

Joseph Fowler

Claude Chapman

Jack Marsh

John Waddy

Edward Glenn

Fred Vann

James Gandy

Marvin Leon Noland

Norman Pugh

Frances Smith

Vearmon Morrow

Joseph Robbins

Louis Edward Winston

William Wilcox

Sam Perry Given

Harry Burns

Flount Hammock

Jack Marsh

Donald Monroe

Ferrell Burt

Harry Reich

Ferrell Burt

Harry Burns

Martin Mador

Dr. Joan Haworth

Sherman Suits

Mike Warren

Dr. James Gwartney

Dr. Richard Barrett

Mr. Victor Tabaka

Dr. Philip Ash

Mr. Victor Tabaka

Otto Carter

Sam Perry Given

Patrick James

Demetrius Newton

Mrs. Lola Short

Willie Lee Richardson

Manager, Employee & Public Relations

Industrial Relations Manager

Plaintiffs1 Research Analyst

Plaintiffs' Research Analyst

Named Plaintiff

Superintendent,Personnel Selection

Named Plaintiff

Superintendent, Grey Iron Foundry

Class Member

Class Member

Production Manager

Superintendent, Personnel Development

Fo rmer Supervisor of Employment

Superintendent, Quality Assurance

Secretary, YMCA

Class Member

Former Superintendent of Malleable

Class Member

Class Member

Local 3036 President

Named Plaintiff

Marketing Manager

Industrial Relations Manager

Vice President, Corporate Projects

Manager, Ala. State Employment Service

Production Manager

Construction Superintendent

Manager, Technical Services

Manufacturer's Agent to Foundries

Manager, Technical Services

Vice President, Corporate Projects

Research Analyst

Defendant Company's Expert

Legal Clerk

Defendant Company's Attorney

Defendant Company's Expert

Plaintiffs' Expert Witness

Defendant Company's Expert

Defendant. Company's Expert

Defendant Company's Expert

Superintendent, Grey Iron Foundry

Industrial Relations Manager

Named Plaintiff

Plaintiffs' Attorney

Class Member

Class Member

1-2 2

48-72

73-253

254-308

309-348

349-416

417-507

510-644

645-699

700-752

753-785

786-855

856-391

892-925

926-963

964-1012

1013-1045

1046-1094

1095-1123

1124-1153

1154 -1178

1179 -1247

1248-1274

1275-1292

1296-1320

1321-1364

1364-1378

1379-1481

1482-1526

1527-1559

1560-1580

1581-1656

1657-1688

1703-1712

1713-1782

1783-1825,

1826-184^7

1845-2162

2166-2325

2326-2406

2407-2536

2537-2607

2609-2655

2656-2700

2701-2729

2730-2735

2736-2750

2751-2774

SUMMARY OF EEO-1

OCCUPATIONS

IS 55 1967

BLACK WHITE TOTAL BLACK WHITE

OFFICIALS & MANAGERS 1 101 102 1 120

PROFESSIONALS .1 22 23 1 23

TECHNICIANS 1 21 22 1 21

SALES WORKERS 1 1 1

OFFICE & CLERICAL 5 193 198 5 191

CRAFTSMEN (skilled) 152 162 162

OPERATIVES (semi-skilled) 854 260 1,114 875 275

LABORERS 115 115 118

SERVICE WORKERS 25 25 26 0

TOTAL 1,002 760 1,726 1,027 793

. ~ . . . i •; . t*

APPENDIX B /TV )

0

FORMS

JOI.AL BLACK

1968

WHITE TOTAL BLACK

1969

WHITE TOTAL

12] 1 126 127 1 132 133

24 2 29 31 2 29 31

22 1 19 20 1 21 22

1 1 1 1 1

196 6 200 206 8 205 213

162 152 152 158 158

1 ,150 881 24] 1,122 890 213 1,103

118 131 131 128 128

+26 23 17 40 25 21 46

1,820 1,045 785 1,830 1,055 780 1,835

SUMMARY OF EEO-

OCUPATIONS BLACK

1971

WHITE TOTAL BLACK

Officials and Managers 2 141 143 4

Professions 2 43 45 4

Technicians 1 34 35 2

Sales Workers 10 10

Office and Clerical 14 184 198 12

Craftsmen (skilled) 188 188 2

Operstives (semi-skilled) 886 280 1166 934

Laborers 123 14 137 204

Service Workers 30 + 24 54 41

TOTAL 1,058 918 1976 12C3

FORMS

1972 1973

WHITE TOTAL BLACK WHITE TOTAL

164 168 6 168 174

51 55 4 51 55

37 39 5 31 39

11 n 11 11

198 210 18 189 207

202 204 4 185 189

315 1249 926 293 1219

30 234 291 38 329

26 67 44 29 73

1034 2237 1298 998 2296

o,. APPENDIX C S.L r> r" r

J *—— -E.UU-44------____ ---- AUAL.5CS1S-QE_S:cC KHAfc..VALVES-ANC.fIXTINGS CO.

_av. 9f.NiCRj i v or o

HCUR.LV. PAYROLL REGISTER AS OF 09- 0?-71_n

. AiUKEM

— „ .1 «

X-LijaWH1TF

n s o -AV2.SX04044X2- --- .5 4 VC-ftAJc_ . BLACK ... ....AVE .GEEWH I TF S3. 72 DATE AV/F ,P. P(*. . HR.S . —6VE.R&EKWHITE

* |

*

_t» —

BLACK WHITE BLACK WHITE ii LACK WHITE' ' BLACK black WHITE BLACK -----« i«•

< •--- —OJ_—i_a_ 2 c;q —66. .76 _64..-5-1— 3.«-4 4 2.99 . 5059 .01- ' 4169.03 12 70. IT 1073.9 202.9 27.5 4.02 3.88

e

|

-02---- 6-— 59--- - 32.43-— 62. 69-

—65.33-

------ 2.S9-

------3. 53-

—3 .C4-

3.05

. ---- 3 8 4 4 .23-

---- 6324. 04-

—4351. 12-1

3686.26

_ 9 72.4 1039.2 . l 6.9

- 03-—46- -292--- -20.03- 110-4.8 1013.9 49.5 27,1 3*91

i — ■■- 0.4-----l_ 26--- 10.00- 64.6 0 - 2..ac ’ 1 ,0*5 323 .52.._4 4 37.49- 112.0 1 1 2 5 .'6 ’ .0 2 0. q

« Q

10--- - 05-

- 05-

--32-

- 474-

--- 3----

—20---

-fc5- 05-

_65..45_

- 6 1 .6.7

—64. 06- ------ 3. 42-

i . i n

_ 4061 .11-

.--4 5 70.81..’,

_2846.56

... 1247.8 _ 1319.7-__

960.5 1022.6

__ .2__

_ ?

__.3 .6_____ 4 • 14 —. 3.46

"

“ cl?-----02----47—----1----—56.4-2----51—30- 4,2 0 - —5.700.52_ 45 87,01 .... 12 7 6,6 1 2 a n . o . 9 . n

- 06-- 19- ? - 63.63 - 63.,50_ 3 6. . 3 . 7B-. 6 4 5 9 . 1 r c y *> 0,4 6

-----u

-OS-— 50- - 66.40 _ 53.25-_ _ 4.. 3.5 _ 3- 4.1 — 4507.23 —__ 1263.4—...1235.3__ —■44.3_

------- 4•05__4•1Z_ ---- or ^

“ CIS----—1-0- — 42--- —67-. 54 ---5-9.53 ■3,CP ' . 4610 .O’ 4427.01 • 1046,7 t?30-3 76.9 1 2 . A

l«--- --11---- i*_— 52--- - 32.25- -_64.32_------ 3. 40- —3. 2J_ _ -3 042 .22-— 4627.24 e 4 3 . 3 • 112 3,3 2.0 7 r4 3.1 Q

-----ii

0

- 32- -7- — 56_- 74.30- - 63. 32- 3.41 3 .24- _ _ .4718.69. 4500.69 '115.8 .-1194.9 30.2 " c14---- 13 ---40—-- 20----—66—a3--- 6-3- *A-5_ —3.3 ̂ 2.23 — -3631.44 _. 4449. ,41._ ’ 1C 16•0 1205.2 .6

-34- --45--- ---- 00- _6.UJ3- .00- 2.4 3 .. - in 4533-51 ,0 987,3 ■ 0

... —„

o

n — — —-4 5-— *5- -454--- - 65. 04-— 64-..4.9------- 3.25 - 3-, 02-_ .. - 4410-95 3916 .5 4• 1 r.QQ ,2 1034.3 5.4

Ji----- 36- --00-----2----- 62—90- -- 63-.J0--------3-+.88—---3.31- -----4 521.0c -—4378.19 . - - 1C58.6. 1276.2 1 6 . A _ ?

-----" V̂-

u--- -'37----0- — 56--- - 73. 13- 64- 7.7 .. -3-10- 3 319. 6 i A4V/3 1'

-----n

/*-•

ji —— — - 46----J_— 27--- -34-44 _ 63.,33- - 3-2 1 - 2,31 ------3 7 1 4 .26- — 44 42.9324 3.25

---- ii ^

_3.43 _—- r !?«----—1-9- ----2-----1---- - 66 .-50- -3.-5*_3.. 3 0 — 5 039 • 62..- 4503.37 • 1 3 1 2 _ Q 1264,0

n— — —-2-d----0- --33--- - 32 .33-— 5 0 .-55-------2. 94- —3 .0-0-------3 501.45- — 4999.58 —-----1C 31.3 — 1161.2___ _4 .0—___. 6____ 3.78 —-4 .31- _

-----.

— , e f

7* —-- -21- - 33- — 45--- - 65.50- — 6 2 .00- _3 , ̂ 2 __—3 .;o---- -5663 .34. - -.4734.99 .... 1389.3 ... 1352.9 114.2 112.6 3.^4 l

J7---- - 2 2 - - ■ 2 ----5----- 71.03 -- 65.23 -------3— 0 3 - ’ .24 i s n 7 c, o 3553.98 . 1268.9 1144,5 • 1 . 1 5 . A ‘ - i

- 70 — — —-20----O-. -6 9 .33- — 33. 00- ------3, 4i_ - 2 - i,i —. . 4513-75 _.1329-9 ̂ 364.9 14.1 _• 0

•

J9 —-- -74- - 23- — 42--- -57. 75- — 54. 52 --- 3.33- . 2,33 ..... 6004--92 . ... .4706.-89 '13.9 4.*! 1 0̂5,6 210.0 ___ -4 .31—

-—. - |

JO ■ ■ i"--- ---------------------------------—t

*

- o „

U -

;___ or

-------------a u n _ l l -----------------------------6il»UCS.LSi_Cc._SI0C KhA-H..V.Al\/ = S ..AN'). F I I f IN'G.S!' CO .• -HOUR L V ..P A Y.R 0.L L .. R FG.I S T £R .AS 0 F ..09-Q.2.-7 3_.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ----- '--------------- --- BY. .SEN IC° ITV DEPARTMENT . .___ ..._______ __________________

__ _ 0002 . “ Q.

o.__ — QE£I CiLlidata laant .*< v rS c * T = . ..V i .CSCSS TC Atf F -RFC, . H R <s . A \]r- _ PRFM -.HR C . r jWHITE BLACK WH I Tc BLACK WHITE BLACK tr<H i T c iiLACK WH I T t black WHITE . BLACK WHITE BLACK -« i *

1 o

f . * 2 5 ? __..QQ— _5.6_.ilQ. . .0 0 _ 3.2 6 ........ .00' 4561 .’3 .0 ■ 1319 .*0 .0 . 2 •00 3.46 - o

i ^̂ } — — 26___ L___ a___ 65..QQ__5d^ia_____ 2 . 2 2 — .2 .2 2.... ._ 4560.25 i „4375.53 ' 1224.6 • ' 26.2 90,) 3.40 3.57

u

c~ K

^ •

1

1-- . ' ’ '

o —

TOT 571 1246 65.63 63.96 3.63 3.06 4668.77 4138.02. ' m i .5 1081.4 40.3 20.9 4.20 3.83

It

o

u-- “ o

0 ..-

—If

n

1 ■' • • .• . • ' . . • . • " Ois---------- — ----- ---------------------- - - - - . __

i D „ ~ ' . A

“«T

]! 1 ~SI

*

1 21-- “ C

1 H-

—ti

c- • <

2«-- ' « ■" c

3n—

—»

r*■ • , ~ 7 -- — •

.J

V

C

r

IIIi

c

o

i

PUN 15 ANALVSIS OF Si ICKn AM V/.LVFS ANO F [TTIi'n'GS cc h

i fi

!

1

! o 4 —

' A.VbKAGE KATES •rV's 'EN1.CP I TY-ENT IR

1 YEAR NUMBER 2! INCENTIVE AV F;.RATE . A V l • G R 3SS TO DATE

4 —

WHITE bLACK WHITE BLACK WH I TE BLACK WHITE BLACK

i ~N ’ — 1923 1 1 0 0 . 0 . 0 3.21 .0 0- '689 5.3 Ii

i 1928 J__ . 0 1 0 0 . 0 • 00 1.14 . 0 0 5417.93 'i ^

1922__ _____J__ . 0 1 0 0 . 0 4 9.74. 4 J

i o 10 _ 1930 JL

-

3.09 *00 3 7 1 7 . A 6

i ^i ''

1932 - 1 . 0 no . o . , 0 0 2 , 8 5 4d c;4. OS .

12_ 1513__ _____ 1_ . 0 .3 ___ , .00 __3.31. . 0 0 5122, L5i

i o 13 .. . 1 . 0 . 0 w 3.36 . oc

» ^ 1936 J.- a -IPl-j-O- 3 o_, y _ 1 .2.i_ .3.2iL ' 6951.74 33̂ .33 • 79

i ''

1 13_ 193 7 4 .0 50.0 . 0 0 3.G.5J . 0 0 5635.69i

o 14 __JL93JL _ J__ ... . 0 . 0 4_* 4J. __*0 0.i

1 °

1/_ J9-31 __ 2_ 4- It.. 4.7.__ 2-. -JS. _5 7 L 3.7.2 — 5.L73 * 15 „

1 2it.Q 4 14 25.0 57.1 4.16 T-/5 __64.3 7* 11 54 91 -C4

i 3 11 _-194.L _ _Lfi_ -3 .'24. .. 3 *.17. 5 2 d3 * 0 5

1 ^

1

20 —-19-42._______3. JL1_ .25.11 JLL2 L- 3. LS._ 5901.34

— 1591__ 8 26 12.5 53.8 4 . IT •» - 1 9 5 ■' y< n . 9 4

0 2? _ 'j.944__ __ _3_ ____ a. _ _2 L lil.i. _..13-99. . J * z 4_ -.-j3r.lG.55..--

5 5 9 i . ,9 6-71 -1943 __ -5. . q _3 *97 3 * Ido

74 1996 6 36 16.7 61.1 4 . i 5 J *.L2_ Ij/lc 1 7* •

Q 73 _-li.9_L_ ___2JL 3.48- j . Z2 . . 6117- at 4 r> 1 7:2- 1 7 •’

0

M -19.4JB. 1 a J .22. 3 6 3 1 *13 0 54 L:i. 44

n 1949 7 - 0 1 0 0 . 0 .* 00 3 - 04 *.0o

J 7*___L55lQ._ 7 ____u___ZsLJi. 4..5_,J?__ J .95. .3.2 L_

j 21 —__Lll^. ____5— _ _U1 l l _iiL_a _ 4.12 __ i.i_a. ' . 622.7 .34l j

l «.

I

APPENDIX D

iurlY payriill Register AS OF 09-•02-73 0001 P ) ( 915”

4

•: PLAN! '

AVE .REG.HRS. AVE.PREM.HRS. GPOSS/REG.HPS.WHITE BLACK WHI IE ELACK WH I TF BLACk

12u2.5 '.0 . .0 .0 5.46 .00

.. J:0- 1.304, <i . J0 - .0 . 00 4.15

._,.a 1305,5 , . *o 28.1 . OJ 3.81

. _(7. ...149.2,2- .oc 3.33

.0 I 402 . 4 , ,0 95.9 3.43

._____ -£L L22Aa.___ .0 2.4 .00 4.67

’______,D. _ ... -,JA —LLL,-8-_ -,00- 3.74

..127-9..5-1_ 131-7 j.o ■ :,s> _— JJ.-L. 5 • 44 3 .99

__ . . .0 1 40? .4 . 0 1 34.0 .00 4 . C2

,i_l , . 0 — -,.CL_____ -4-,2J„— n£LL_

__ li3Ĵ..7.. ..1.29-O.iL _ ' .,IL___ £l»J\_ -5_,02 3.98

niz,2_ .13311,7 34.9 62 • o 4.94 4.10

J-233.-3-- JL26-i* Jw. _ -.1111,1- 2D-.J- _____ S..-19 4.17

131.9.21. --LlliLLL __ J71L.1 -IJ-D _ 4.4 7 4 *3i?

1247.-6.- 1303.8 34.9 4.79 4.13

__ iao.7.,xi. -LZaiî lL _ _72l,_2_ - -4L.J-- 4_» 04-

__ 12.1L.-5- -. L312.it- _ J29..-4__— 4J-.3- A ̂ LL

1171.7 .. 12114.5___ 4.0 36. C 4.93 4.05

- 1211̂ 9. _ _ _JLl»2. ■OJi-

.J.2 2.9.01. -12-7.1-JL._ ;JUS _ -23,_5 - ■'6,-5 0 4 .2̂

.12.0 7. 9... ’ . 44il__ .0 .09 .3 .98

.liaiUL.i J21_5_̂ &. J2UU2. _ J1L.-7 _ 4j-5L7_--_3_, 9jj_

_i_L22iLLS__ ___S1!.JL_— L'6.7„____ JLi?.- -i-LLO_

0 1

n

v r

o

2 RUN 15 ANALYST S OF STUC \ H A H V A L V l * S A i\ 0 r IT j MOS C j h YU-IV P <;>.•(ILL REGISTER AS L-F 0 9 - 0 2 - 7 3 0002

1

*

o

A V 2 - Vic TATES BY SEf ■T ITY-ENT I » r FL.ANT a*

1 YEAR NUMBER Z INCENTIVE A V f. . KATE AVfc.GH "S. . it r.a t r ' A V r . K E G . H R S . AVc.PREM .HR S. GRCSS/PEG.HRS.

•

WHITE BLACK WHITE BLACK WHIT h ‘LACK WHITE. BLACK WIUTt. BLACK WHITE BLACK WHITE BLACK --------------" C ■

o 1 15 52 7 1 1 4 . 3 1 0 0 . U 4 . 9 1 2 . 9 u 5 7 2 9 . 7 0 4 7 5 4 . 4 0 1 2 3 6 . 5 1 2 2 9 . 0 2 0 . 1 1 . 0 4 . 4 5 3 • B 7 r

1953 3 _ _-ZQ .oL___ t_Q_ _ . 5 0 . ' •. 1 3 J Z .9 . 4 . p 7 .u o

« L 2 5 Z _ _______ I _ ______ L _ 2 b . 6______Z) _> __ -.^ «30 .. . _A2 S. V.,. A 6. ... 1 3 5 9 .5 ’ 7 0 5 . 0 5 1 . 6 1 . 0 4 . 7 7 3 . 6 3

-

o 10___ l_9_5_5__ 5 _ _-2__ •-Q.2UlQ.tZ _4_« 16... .3 ,.0.0.. 6.7.22 .2.5. 5 6 0 3 . 3 ... L 4 2 5 .2 . i 7 7 0 . 6 JJ i4 ..Q 9A -9 4 * 7 A

n 11 _L9SA L _LLZ______ ZL _ .. z a _ -5.762,-9.7. - - J .2 7 3 . , .0 -0 4 - *Y ft ^qq

17 1957 _______ 6__ .0.1 l 3 4 :>. l __ .Jj__ - n 4 - 4 .n o

--------------B ^

O IJ___ 1 3 5 2 _ _______ L ___ Z 1____ZL . 3 - 'IS .— .........._ v j ( l _ ____ _Rj____ 7S . 4 4 . M

0

11___ L955._ ___ 33-' ___ -jJ.__ Z Z ^ L _ .3 ..1.4____ .. ,.00. . 0 4 ft - 4 4 . n ^ --------------- r - '

I*- 1 QA1 _______ X. 7.13 __4 7 . 9 4 9 . 7 __3 ..3 - R. /. P 7 A . A 7 -L3JZ3. '* 1 ft 7 Ci . ft' r v s .f i 5Q - 1 s . nn

o 10___ L 9 6 2 - __ -LB. __L4.tZ 2 L Z .Z 4 . 1 6 . - . 3 , 2 8 . ___ Z L 9.7 . .3 a 7 7 . 4 1 ft -4 4.7,7 ft - Q fi Q '

o

17___ L063_______ 2 7 . . __ ZB. -L Y Z —Z Z - 'L . 3 2 5 . . . 3 0 . 1 ______ 5-8-75.92 2 * 2 2 6 . 1.3 -.1 . - 1 3 1 5 .3 . ___1.242 -S_____ 4 4 - 4 - ft Q . n 4 . 4 f t 4-0i*

___ 197,4 _______ 5_______LB__ 4 0 . 0 54.7, J . 2 2 - ^ r . i i . 33 -2122-. 73__- - .1 2 6 3 .1 . Iftc^ .-ft - ft 1 A . 4 4 . ft ft ft.Q 7

--------------. , Q

o )•___ L9 6_i _ ______ 3JL_ _LQZ_ __L6_L, Z .4 . 2 3 . . 9 L . J O l - -5 -952 .15 -5 0 ‘V i. -i3 ____ ft ft - S ___ > 0 . ft 4 . 4 7 ft .Q7 O

o

70___ 19 6 ll _ ______ L3._ ___ 7.0. _ _ L -L -. 7 .L .4. . 4 . l a . . . 132-4.4, _ _ 142-^2___ ft 4 .7, ft.CA

L 2 6 L _______ 211_ 74 __31L.il__ 6 ,0 .0 ___ - 3 . 1 3 __ -5 .9 2 4 .2 4 T l > ] ’ ^ , 7 1 2 7 2 .. 3__ ft S . 4 4 - 4H ft - Q ft

--------------" C

o n _ _ _ l 9 6 i _ ______ La._ _____3-0.- —A_A_̂ .4---- 6-9-*-/*---- - 3 . .1 1. .. 5 6 7 5 .2 2 3 .3 6 5 -. 7.1 _ . .._13Lri . 3. _ _12i.-i.-7-- _ ___ 3.1—A. ft 4 2a_ 4 *30 ft - Q 0

-

n ___ 19-6.9. _ ______ 24. _ _____7 Z _ — 2.5. . jJ___6o _L -554*2.63 4 7'3 5 ..26 . - ___ L32.3. 4: _ All. 4_ ) ) . 7 4 .1 f t ft . 7.,

o

7*___ 197 Cl... 3 4 —_____2£____14.27 J L . 4 3 . HO__ - 3 . 0 / - - 537 'i.. 3 A 7. <. j. 1,7' , — - 1 2 9 2 ^ 2 -

___ - _L322 . 3.

1 / (\ 7 . s 1Q.Q

01

o w___ L9L1 Z7. _ _L25._ .2 6 —6. Z Z . 2 - 3 . 0 7..... .... 5252 .. *»3 - I 2 3 1 .9 . 1 ! - ? ft T/.ft r*

!* ___ L9.7_2__ z a L I Z - __3.. 32 .- - j - .o a ____ 4.7 5 7. ..52 .. -13X52.: .9. \ ft4 . n ft - f t 7 ,o

7’___ 1973__ _ 1Z7 ___ 27 3 . __55—1___B 5. J ... .3 • 14...

-

•I .43 4 . 1 AO‘J /1 . M - f t ft -ft ft . 44 ft - 1

<5*

o >i , l<*'

I *

*

3Z

I

TOTAL 571 1246 3 1 . 7 7 0 . 0 3 . 03 3 . 0 3 40o 6 • 7.7 4 1 3 8 . 0 2 • 1 1 1 i . 5 1031 ..4 ■ 4 0 . 3 2 0 . 9 4 . 2 0 3 . 8 3

-

V

APPENDIX E

A'--

______________________________SI.QCK.bAM.VAL V tS.. AND-F-ITIINGS-NUMEER B Y - Y E AR... ANC - JOB _C LASS—.ENTIRE-EL&NX- _QaQL_ K 9 K

o f

NUN-INCENTIVE

YEAR i 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 12 YEAR 1 2 • 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 " a

1 °33 • 1 9 3 3 . 1

___ _ 1335 —

1536 ’ 15 3 6 1 1 1 1

19 3 7—. l _.l—

1 938 - 1 1R 3 8

1940 ' 3 . 1 540 3 1 1 1

1 •a . 1 cat - _ 1

1°42 1 2 l 2 154 2 A

1 1 c; ..154 3 A _ 3 __]_ 3 _ J_

1944 l 1 1 2 1 544 3 1

- - — 194.5 - k -- 2 - . . ___ 2 - 154 5 -

1546 i 4 19A6 A 2 2 4 1 1

1547 — . 1 .. 3 . _ 1

1548 i 2 1 54b i 1 1 1i ] -2 ] R 8 o A _2. 6 2

19 4.1 2 1 2 1551 2 1

-2 1 552-..

1563 ' A . 15 5 3

1955 2 3 155 5

__________ 3 Q _ 1 4 .1 2 . 15 5 6'

o

o

n

1957 .1S5B—

15 59

-1 -941 — 156 2

- 1 5 6 3 ----

1965

1.

-11

„--------------- 4 -945-

1566n-------— — ———— 4-5 6 7-

1968 -4969- —3--;

2-6.1

...3-

1 31--1-

7

-7 -

156 7

.15 5 6

1559 1 St 1.

1 56.2

1563

1 564

.1565

1 566

1 56 7

1 56 6 -IS

1970 A 1 1 : •> 1 4 1r'.li. 1 570

a ___ . -1̂-74 _ _A -2 . _ 7 _ 6- _1 -6-~. 4- - - 3 — _. 3— 15....... ...1571

1972 7 2 1 1 5 c, u 3 3 1 ■4 4 ' 1572

4-9-7-2- - -3 _£ - 2 . -.7__7- 7 6 .... 1— 1.2...3- ------1.S33.

total 24 1 5 A 2 12 2 3 2 6 10 5 3 26 .23 31 141

i- ■ 3..._ ...1 .

1. 3 3

1. . 2 .

1...5 .,

3

1

9 .

2

_ 1. 7 1 1

—i c

1 1 1 4 1

6 4 .. 3_-18- 3 -_ 3 i- — c■ ' - 5 . 5 2 3..2....2. T

! L 1 1 2 3 3 c

1 A 1 -10 2. 7 1

! . 4 2 1 1 \

1 13: 9 .A .... 6..-. - A._ . A - . c! .2 1 . 1 2 4 1 1

5 ■ 3A . 7 3 1 _ 1 ' O

. 3 128 38 47 91 28 22 6 5 2 2 2

' -.f ̂

0

____ E.UH-L8-

" ..................... . , ■' ' ■ -r-" : . ____________________________________________________ ______ .0 r

_______________ SiaC^i^M-VALVESL.ANO FIT.U'ICS-NVMHfft.BY YEA* ANCL.J-C.d_ct. A s s u m e _PLAMT.------------------------------ AQ.QZ-------------- -----------------" •

INCENTIVE

G ’ ~

Yc AR

' 1923

1928. .

0 * 1929

_15 30

1932

1977

l i 3 8 _

0 1940

133 41__

1942

1 9 4 3

,4—— — — — — — —----

q

1944

1 9 4 5 -

1 946

1 66715

O ..

194R

19 5 0

1 3 5 1

0 145?

1 4 47

1454

- 1 9 5 5 -

” "‘j G 1956

- 1 9 5 9 -

U , 1961

___1 3 6 2 -

a - —--------- — —

1963

1965

_ 1966-

G 196 7

]

Q , _ __ C_____

1969

— 19 20

2S — — — — — — — —---

G

---------------- —---

1971

1912

1973

7 • 10 ‘11 12 . 13 Y r!

1 92 3

1

__ 2_

2

.1 .____

1 929

1 930 . 1 972

1 9 3 d

1 9 3 7

. 1 9 2 9194 0 1941.

1 94 2

rs

B L A C K S c

1 2 • 3 4 •5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 r

- -1 - C1

i3__

. 1 -

_3_

_ 3 .

■ 4

_ 2_

3

. . 2 .

__2 -

2

_ _ 1 _

'■ 1

__3 _

3

__7._

1

_ _ 1 _

1

c

4

- Z .

1 544

1 5 4 5___ : ,___

1 546

___ 3...

4

1

3

_ _ 4_»_9

4 r

4 ?

1

5 ~ 1 1

4 1 -------------------------------

’ 548 2 2

1550 1 • ' 2 7 2 2 1

O

1

_1_

D

1952 ■ 195 3_

15 54

" G

_ .___ _______ ,.1555..

1556

3

. . . . 1 -

4

1 459._______

1961

______3 __

2

.4 _

2

4 _

-1.9

2

4

__0

2

?

__2 __

1

1 1 - __________________ _________________

c

1 5 c 2.

156 3 1 10 6 19 7 6 2 G

1964.___ _ —

1 565 11 10 30 9 5 3

1 9Ld — __ 1___Li.---

1

3 2

. . I ----- 4 ----15 1

______ 1 ____i ____l ------1 ------5 --------------5 — n

16 32 14

1 967

| O R 4 .

1

5

2

2

R

9_

1969 3 15 .9 15

. 1 970.____ ___ 2 _ 6_ ■7 , . 4_

1571 ■ 6 18 10 40

1 5 7 2 ____. . . 1 2 . . 1 7 . . .11_ .23. „

1573 176 16 7 28

18__6___I-1 2

2 ___3_

2 ’ _ 0

3 5 2— 4 _ — 3 ____________________________________

1 3 1 G

. IQXAL. ..12. ..106_25-- ------- -----J-'- _._____ __2Q2_Ua_lQ5_2.63__6 8__fei— 18-- L

: J .. _ t

< •