Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 3, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond Brief for Appellees, 1972. 2557a4a2-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d9cfb4d7-f2f3-4073-a454-2241e621cab1/bradley-v-school-board-of-the-city-of-richmond-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

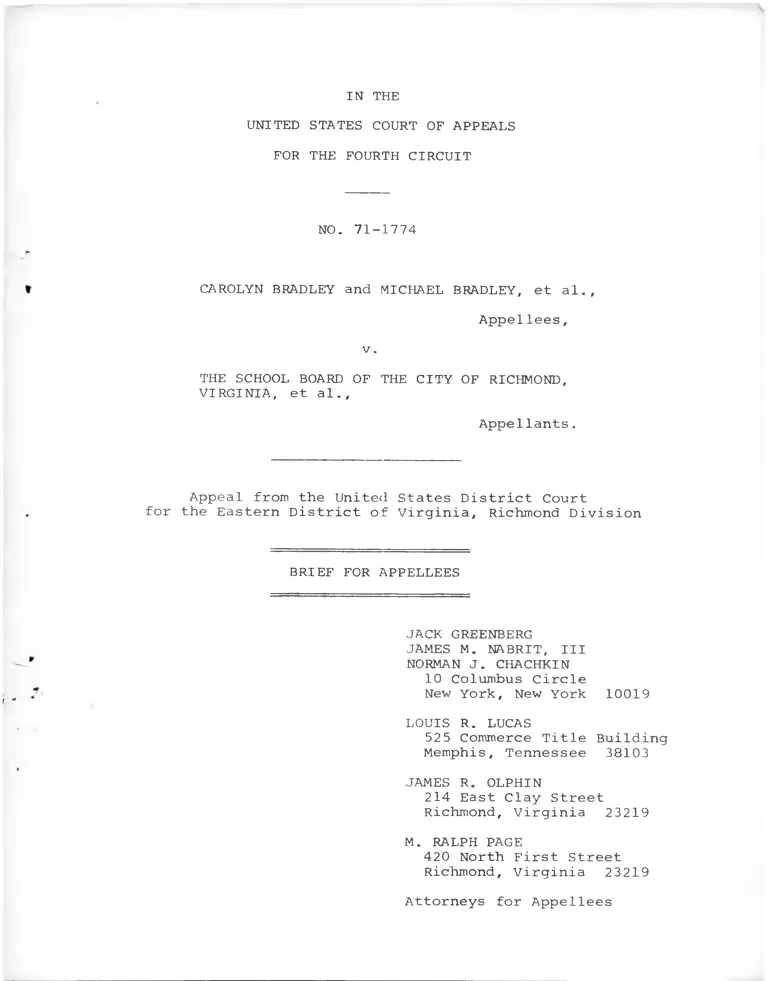

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71-1774

CAROLYN BRADLEY and MICHAEL BRADLEY, et al.,

Appellees,

v.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF RICHMOND,

VIRGINIA, et al.,

Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

LOUIS R. LUCAS

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

JAMES R. OLPHIN

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

M. RALPH PAGE

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Appellees

I N D E X

paae

Table of Authorities........................... ii

Issue Presented for Review .................... 1

Counter Statement of the C a s e .................. 2

ARGUMENT —

Introduction ............................ 6

The District Court Properly Awarded

Counsel Fees To Effectuate The Purpose

Of The Civil Rights A c t s .................. 6

The District Court's Award Of Fees

Is Within Its Equitable Discretion . . . . 14

CONCLUSION..................................... 41

Certificate of Service ........................ 42

Appendix A

l

Table of Authorities

pa.ae

Cases:

Avery v. Midland, 390 U.S. 474 (1968).......... 29

Basista v. Weir, 340 F.2d 74 (3d Cir. 1965) . . . 7n

Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (1946).............. 11

Bell v. School Bd. of Powhatan County, 321

F. 2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963).................. 15,18,19n, 20n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 382 U.S.

104 (1965)................................ 3,20

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 345 F.2d

310 (4th Cir. 1965) ...................... 3,12,16n,18,

19n,2 2

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 317 F.

Supp. 555 (E.D. Va. 1970) ................ 4,25n,28n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F.

Supp. 456 (E.D. Va. 1971) 5,31,32,33

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 325 F.

Supp. 828 (E.D. Va. 1971) ................ 36

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 53 F.R.D.

28 (E.D. Va. 1971) ........................ 2,6,16n,19,20n

24,25,26,28,31

33,34n,36

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 434 F.2d 408

(4th Cir. 1970) .......................... 26

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37

(4th Cir. 1968) .......................... 25,26

Brotherhood of R. Signalmen v. Southern Ry.

Co., 380 F.2d 59 (4th Cir.), cert, denied,

389 U.S. 958 ( 1 9 6 7 ) ....................... 10n,l2n,16n

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954);

349 U.S. 294 (1955) ...................... 9

Brown v. Earth, Inc., 2 Race Rel. L. Sur. Ill

(M.D. Tenn. 1970) ........................ 12n

li

Table of Authorities (cont'd)

Page

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d

820 (4th Cir. 1970) ................. 39

Carlisle, Brown & Carlisle v. Carolina

Scenic Stages, 242 F.2d 259 (4th

Cir. 1957).......................... .. 15,16n

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 304 F.

Supp. 603 (E.D. La. 1969) ............ 8n

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 449

F. 2d 493 (8th Cir. 1971).............. 19n

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 426

F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970), cert,

denied, 402 U.S. 952 (1971) ........... 26

Conte v. Glota Mercante del Estado, 277 F.2d

664 (2d Cir. 1960).................... lOn

Dobbins v. Local 212, IBEW, 292 F. Supp.

413 (S.D. Ohio 1968)................ .. 8n

Dyer v. Love, 307 F. Supp. 974 (N.D. Miss.

1969) ................................ . 29

Farmer v. Arabian American Oil Co., 379

U.S. 227 (1964) .................... .. lOn

Felder v. Harnett County Bd. of Educ.,

409 F.2d 1070 (4th Cir. 1969) ......... 13n,24

Fleischmann Distilling Corp. v. Maier

Brewing Co., 386 U.S. 714 (1967) . . . ., 8,lOn,lln,16n

Flemming v. South Carolina Elec. & Gas

Co., 239 F.2d 277 (4th Cir. 1956) . . .. 21

Gibbs v. Blackwelder, 346 F.2d 943 (4th

Cir. 1965) ............................ , 13

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) .........., 20,21,22,23,

24,26

i n

Table of Authorities (cont*d)

?.a9e

Guardian Trust Co. v. Kansas City Southern

Ry. Co., 28 F.2d 233 (8th Cir. 1928) . . 15

Hammond v. Housing Auth. & Urban Renewal

Agency, 328 F. Supp. 586 (D. Orel.

1971) .............................. . 9n, 12

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate

School Dist., 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 396 U.S. 940 (1969) . . . 26

Holley v. City of Portsmouth, 150 F.

Supp. 6 (E.D. Va. 1957) ............ . 21

In re Carico, 308 F. Supp. 815 (E.D. Va.

1970) .......................... . lOn

James v. Beaufort County Bd. of Educ.,

Civ. No. 680 (E.D.N.C., Nov. 15, 1971) . 12

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 (1968) .......................... . 7n,8n

Kelley v. Altheimer, 297 F. Supp. 753 (E.D.

Ark. 1969) .......................... . 21

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) lln

Lakewood Homes, Inc. v. Board of Adjustment,

23 Ohio Misc. 211, 258 N.E.2d 470 (Ct.

Common Pleas 1970) .................. ,. 11

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86

(4th Cir. 1971) .................... . 8n,17n

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d

143 (5th Cir. 1971) ................... 9,11-12

Lightfoot v. Odum, No. 11,647 (N.D. Ga.,

June 29, 1970) ......................... I2n

Local No. 149, Int'l Union v. American

Brake Shoe Co., 298 F.2d 212 (4th

Cir. 1962)................... . I6n

Lyle v. Teresi, 327 F. Supp. 683 (D.

Minn. 1971) ........................ , 12

I V

Table of Authorities (cont'd)

Page

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) . • • 39

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396

U.S. 375 (1970) .................. 8,9n,lln

Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Educ.,

418 F.2d 1040 (4th Cir. 1969) . . . 13n, 14,21,23n,24

Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 308 F.

Supp. 407 (S.D. Ohio 1968), Civ. No.

6871 (S.D. Ohio, March 12 and April

1969) ............................ 22,

11

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

U.S. 400 (1968) ..................

390

8n,10-11,13,14

Newton v. Consolidated Gas Co., 265 U.S.

78 (1924) ........................ 15

North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v.

Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971) ........ 39

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Tel. Co., 433

F.2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970) .......... 8n

People v. Doughtie, Civ. No. 1150-S (M.D.

Ala., Nov. 18, 1971) .............. 12n

Phillips v. Pinehurst Realty Co., 2 Race

Rel. L. Sur. 33 (M.D. Tenn. 1970) • • 12n

Pina v. Homsi, Civ. No. 69-666-G (N.D.

Mass., July 10, 1969) ............ 12n

Research Corp v. Pfister Associated Growers,

Inc., 318 F. Supp. 1405 (N.D. 111. 1970) 2 3n

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) . . • • 29

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971) .................. 8n,17n

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 429

F„2d 11 (6th Cir. 1970) .............. 37

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 186

F.2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951) .......... lOn,17,18

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d

1097 (5th Cir. 1970) .............. 7n, 8n

v

Table of Authorities (cont'd)

Page

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School Dist., 419 F.2d 1211 (5th

Cir. 1969) .......................... . 2 3n

Smith v. Hampton Training School for

Nurses, 360 F.2d 577 (4th Cir. 1966) . . 7

Specialty Equipment & Machinery Corp. v.

Zell Motor Car Co., 193 F.2d 515

(4th Cir. 1952) .................... . 16n

Sperry Rand Corp. v. A-T-0 Corp., 447 F.2d

1387 (4th Cir. 1970) ................ . 16n

Sprague v. Ticonic Nat'l Bank, 307 U.S.

161 (1939) .......................... . 15,17

Stanley v. Darlington County School Dist.,

424 F.2d 195 (4th Cir. 1970) ........ . 2 3n

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc.,

396 U.S. 299 (1969) ................ . 11

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............ . 4-5,30,35,37

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ., 431 F.2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970) . 26,27,28n

Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery, 307 F. Supp.

369 (N.D. Ala. 1969), Civ. No. 69-490

(N.D. Ala., Jan. 29, 1970) .......... . 12n

Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills,

353 U.S. 448 (1957) ................ . 11

Turner v. Lazarus,d/b/a Johnson & Lazarus,

Realtors, No. 50366 (N.D. Cal., Nov.

22, and Dec. 3, 1968) .............. . 12n

United States v. Blackwell, 238 F. Supp.

342 (W.D.S.C. 1965) ................ . lOn

United States v. Board of Educ. of Bald

win County, 423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir.

1970) .............................. . 2 3n

V I

Table of Authoities (cont'd)

Page

Vaughan v. Atkinson, 369 U.S. 527 (1962) . . lOn

Vaughn v. Ting Su, No. 49643 (N.D. Cal.,

July 19 and Dec. 3, 1 9 6 8 ) ............ 12n

Walker v. County School Bd. of Brunswick

County, 413 F.2d 53 (4th Cir.), cert,

denied, 396 U.S. 1061 (1970).......... 13n

Wanner v. County School Bd. of Arlington

County, 357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) . . 39

Williams v. Kimbrough, 415 F.2d 874 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 1061

(1970)..................................lln

Statutes:

35 U.S.C. §285 ............................ 23n

42 U.S.C. §1981 ........................... 7,11,12

42 U.S.C. §1982 ........................... 7,9,11,12

42 U.S.C. §1983 ........................... 1,6,7,8,9,10,12,

13,14

42 U.S.C. §2000a—3 ........................... 8n

42 U.S.C. §2000a-3(b) ...................... lln

42 U.S.C. §2000c-6....................... 8n

42 U.S.C. §2000c-8 8n,10,lln

42 U.S.C. §3612........................... 8n

Other Authority:

H.R. Rep. 914, 88th Cong., 2d Sess., 2 U.S.

Cong. Code & Adm. News 2 3 94 .......... 10

vii

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71-1774

CAROLYN BRADLEY and MICHAEL BRADLEY, et al.,

Appellees,

v.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF RICHMOND,

VIRGINIA, et al.,

Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Issue Presented for Review

Whether the district court abused its discretion by-

awarding counsel fees in a school desegregation action

as part of its equity jurisdiction and in furtherance of

federal policy in §1983 actions.

schools. Although the district court had denied a motion

made by plaintiffs after it disapproved the Board's first

plan (A. 69-71) by which

plaintiffs sought to require the purchase of buses, because

of the court's expressed hope and confidence that the Board

would act in whatever manner necessary to comply with

its constitutional obligations (A. 72-75)

, the school board

had not made any arrangements to increase its transporta

tion capability during the summer. The district court

was left with no alternative but to approve the Board's

second plan on an interim basis for the 1970-71 school

year, while recognizing its constitutional infirmities.

317 F. Supp. 555.

The school board was instructed to report by November

15, 1970 what steps would be necessary to convert to a

unitary school system and by what date such a system could

be implemented, but, on November 15, it merely notified

the court that it was preparing plans which it hoped'to

file in early January, 1971. Accordingly, the court

again entered no specific orders requiring the purchase

of transportation facilities, and the school board did

nothing to acquire greater transportation capability.

Because of this inaction and because appellate courts in

the fall of 1971 had deferred pending school cases while

awaiting the Supreme Court's decision in Swann v. Charlotte-

-4-

Mecklenburg Board of Educ.. 402 U.S. 1 (1971), the district

court denied plaintiffs' motion (A. 110-12)

to have their plan put

into effect for the second semester of the 1970-71 school

year. 324 F. Supp. 456.

In the meantime, however, the school board did seek

to vacate an injunction against new construction which

had been issued by the district court pending approval

of a constitutional plan for the Richmond public schools.

Substantial time and energy was expended on this collateral

issue, resolved in plaintiffs' favor by the district court,

which found that the school authorities had not, despite

the explicit language of the injunction ordered and the

court's oral opinion from the bench, reconsidered its

site locations in light of their effect on desegregation.

324 F. Supp. 461.

When the school board finally did propose a new

plan in 1971, it submitted three plans: one the same as

its rejected first 1970 plan; another the same as its

second 1970 plan which had been approved for interim use

but specifically held unconstitutional; and a third, a

variation on the plan proposed by plaintiffs' expert the

previous year. After plaintiffs had responded to each

of these and a full day's hearing was held, the district

court entered an order on April 5, 1971 requiring that

the third plan be implemented effective September, 1971.

-5-

ARGUMENT

Introduction

We argue below that the award of counsel fees by

the district court was a necessary and proper part of

the remedy in §1983 school desegregation suits; that

alternatively the court acted within its equitable

discretion in making the award; and finally, that appel—

lar*ts have demonstrated no abuse of discretion which

would require this Court to disturb the ruling below.

I

The District Court Properly Awarded

Counsel Fees To Effectuate The Purpose

Of The Civil Rights Acts.

The district court awarded counsel fees in this

school desegregation action because "the character of

school desegregation litigation has become such that

full and appropriate relief must include the award of

expenses of litigation. This is an alternative ground

for today's ruling." Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond.

53 F.R.D. 28, 41 (E.D. Va. 1971). The defendants do not

address themselves to this ground of the district court's

holding except to characterize it as a "basic conceptual

change" which has never been articulated by this Court

and which, they suggest, is implicitly in conflict with

earlier decisions of this Circuit. We show below that

there is no conflict between this Court and the district

- 6 -

court, and that the lower court's holding is a fully

justified and necessary interpretation of 42 U.S.C.

§1983 in school desegregation suits.

2/That statute, like its companion sections 1981 and

3/

1982, are part of the Civil Rights Acts passed in the

decade following the Civil War to guarantee equal treat-1/ment to the freedman. This Court has emphasized, in an

action arising (as does this one) under the statute that

§1983

authorizes federal courts in civil rights

cases to grant broad relief "in equity, or

other proper proceeding" and is designed

to provide a comprehensive remedy for the

deprivation of constitutional rights.

Smith v. Hampton Training School for Nurses, 360 F.2d 577,

581 (4th Cir. 1966). In that case, not only were dis

charged black nurses ordered reinstated with back pay,

but the case was remanded to the district court "to

fashion any other appropriate relief in light of this opin

ion." Id. at 582.

The court below has acted in accord with this Circuit

construction of §1983 by awarding counsel fees to the

plaintiffs in a school desegregation case.

jj/ E.g., Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097

(5th Cir. 1970); £f. Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409, 441 n. 78 (1968).

2/ Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968)

4/ Basista v. Weir, 340 F.2d 74, 86 (3d Cir. 1965)

While the statute does not explicitly provide for

such an award, neither does it prohibit it nor establish

5/

an intricate remedial scheme from which a Congressional

intent to exclude such an award may fairly be implied.

Compare Fleischmann Distilling Corp. v. Maier Brewing Co.,

386 U.S. 714 (1967) with Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co.,

396 U.S. 375 (1970).

Awarding counsel fees in school desegregation cases

brought under §1983 will effectuate federal policy. The

plaintiffs in such actions are but nominal petitioners

6/

on behalf of all students. They cannot and should not

be expected to finance such proceedings from their own

The provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act regarding

school desegregation clearly do not provide an alter

native remedy. 42 U.S.C. §2000c-6 permits suits by

the Attorney General of the United States against local

school districts maintaining segregated schools, upon

complaint to him, but no new cause of action or even

administrative remedy is made available to private

parties, as is true of the Public Accommodations Act

(Title II, 42 U.S.C. §2000a-3) or the 1968 Fair Housing

Act (Title VIII, 42 U.S.C. §3612).

In fact, the 1964 Civil Rights Act specifically pre

serves the existing remedy, 42 U.S.C. §2000c-8, indica

ting a Congressional intention that its policies be

implemented through privately initiated litigation as

well as suits by the United States. (Even if a new

enforcement mechanism had been established, no repeal of

§1983 could have been implied. See Jones v. Alfred H.

Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968); Sanders v. Dobbs Houses,

Inc,, 431 F.2d 1097 (5th Cir. 1970)).

6/ The plaintiffs in desegregation suits are truly "private

attorney[s] general," Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 n. 4, who perform valuable public

services. See Parham v. Southwestern Bell Tel. Co., 433

F.2d 421, 429-30 (8th Cir. 1970); Lea v. Cone Mills Corp.,

438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971); Robinson v. Lorillard Corp.,

444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971); Clark v. American Marine

Corp., 304 F. Supp. 603, 611 (E.D. La. 1969); Dobbins

- 8 -

resources. The investigation, research and presentation

of expert and fact witnesses require the expenditure of

tremendous amounts of time by capable counsel, aside from

the actual trial hearings. To undertake to pay the

reasonable value of such services is only within the

financial ability of the rich. School boards, on the other

hand, have at their command in their defense able and

experienced lawyers compensated from public funds, as

well as their own staffs— the very persons enjoined by

law to render and perform the duties sought to be enforced

in such litigation.

Just as courts have looked to more recently enacted

statutes in determining the remedial scope of 42 U.S.C.

§1982, Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143, 146

(5th Cir. 1971), so too does the Civil Rights Act of 1964

support the declaration of a vigorous enforcement policy

under §1983.

The basis for the enactment of the provisions

regarding school desegregation in the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 was Congressional dissatisfaction with the slow

pace of implementing the Constitutional principles of

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954); 349 U.S. 294

6/ cont'd

v. Local 212, IBEW, 292 F. Supp. 413 (S.D. Ohio 1968);

Hammond v. Housing Auth. & Urban Renewal Agency, 328

F. Supp. 586 (D. Ore. 1971) ; cf_. Mills v. Electric Auto-

Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375, 396 (1970).

-9-

(1955). See, e.g., H.R. Rep. 914, 88th Cong., 2d Sess.,

2 U.S. Cong. Code & Adm. News 2394. As noted above (n. 5),

Congress specifically recognized that privately initiated

litigation (brought under §1983), as well as suits initiated

by the United States, would serve to vindicate its policy.

42 U.S.C. §2000c-8. In these circumstances it is entirely

appropriate that the federal courts award counsel fees

7/

in §1983 school desegregation lawsuits to "encourage

individuals injured by racial discrimination to seek

judicial relief . . . " Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

. . . As pointed out in Goodhart, Costs,

38 Yale L.J. 849, 872-77 (1929), the

American practice of generally not inclu

ding counsel fees in costs was deliberate

departure from the English practice,

stemming initially from the colonies' dis

trust of lawyers and continued because of a

belief that the English system favored the

wealthy and unduly penalized the losing

party.

Conte v. Glota Mercante del Estado, 277 F.2d 664, 672 (2d

Cir. 1960) ; see also, Farmer v. Arabian American Oil Co.,

379 U.S. 227, 235 (1964).

The general practice ought not to apply where litigation

is brought to implement important federal public policy.

E.g., Vaughan v. Atkinson, 369 U.S. 527 (1962); Rolax v.

Atlantic Coast Line R. Co.. 186 F.2d 473, 481 (4th Cir.

1951); Brotherhood of R. Signalmen v. Southern Ry, Co.,

380 F.2d 59, 68 (4th Cir.), cert. denied, 389 U.S. 958

(1967); In re Carico, 308 F. Supp. 815 (E.D. Va. 1970);

United States v. Blackwell, 238 F. Supp. 342 (W.D. S.C.

1965); but cf. Fleischmann Distilling Co. v. Maier Brewing

Co., 386 U.S. 714 (1967).

- 1 0 -

8/

Inc.. 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968).

Such a policy is consistent with the general

approach of federal courts in construing federal statutes.

"The existence of a statutory right implies the existence

of all necessary and appropriate remedies. . . . " Sullivan

v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 239 (1969);

11 v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (1946) ; cf. Textile Workers

Union v. Lincoln Mills. 353 U.S. 448 (1957); accord.

Lakewood Homes, Inc, v. Board of Adjustment, 23 Ohio Misc.

211, 258 N.E.2d 470, 502-04 (ct. Common Pleas 1970).

Other courts have held counsel fees appropriate

under this rationale. E.g., Newbern v. Lake Lorelei.

Inc., Civ. No. 6871 (S.D. Ohio, March 12 and April 22,

1969), see 308 F. Supp. 407 (S.D. Ohio 1968) (§§1981, 1982);

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp.. 444 F.2d 143, 147-48

87— The fact that Congress did not add a counsel fee

award provision, as in Title II, 42 U.S.C. §2000a-3(b),

is not dispositive since in the 1964 Civil Rights

Act, Congress did not create a new enforcement scheme

fen private litigants but rather specifically approved

of the old. 42 U.S.C. §2000c-8. Compare Fleischmann

Distilling Co. v. Maier Brewing Co,. 386 U.S. 714

(1967). Language to the contrary in Williams v. Kim

brough, 415 F.2d 874, 875 n. 1, cert, denied. 396 U.S.

1061 (1970) and Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 23 (8th

Cir. 1965) rests upon the sort of strict Fleischmann-

like analysis of statutes which the Supreme Court

disavowed in Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co.. 396 U.S. 375 (1970).

- 1 1 -

1/(5th Cir. 1971) (§1982); Lyle v. Teresi, 327 F. Supp.

683, 686 (D. Minn. 1971) (§1983); Hammond v. Housing

Auth. & Urban Renewal Agency. 328 F. Supp. 586 (D. Ore.

1971) (by implication) (§1983); James v. Beaufort County

Bd, of Educ.. Civ. No. 680 (E.D. N.C., Nov. 15, 1971)

(§§1981, 1983).

Affirmance of the ruling below would not be incon

sistent with this Court's own decisions. There is dicta

in an earlier opinion in this case, Bradley v. School

Bd. of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310, 321 (4th Cir. 1965) that

an award of attorneys' fees in a school desegregation

case should be made only "when it is found that the bringing

of the action should have been unnecessary and was compelled

by the school board's unreasonable, obdurate obstinacy"

10/

but there the issue was the adequacy of an award, not

0/ Unreported actions involving discrimination in the sale

or leasing of property in which attorneys' fees have

been awarded include: Turner v. Lazarus, d/b/a Johnson

& Lazarus, Realtors, No. 50366 (N.D. Cal., Nov. 22 and

Dec. 3, 1968); Vaughn v. Ting Su. No. 49643 (N.D. Cal.,

July 19 and Dec. 3, 1968); Lightfoot v. Odum, No. 11,647

(N.D. Ga., June 29, 1970); Brown v. Earth, Inc., 2

Race Rel. L. Sur. Ill (M.D. Tenn. 1970); Phillips v.

Pinehurst Realty Co., 2 Race Rel. L. Sur. 33 (M.D.

Tenn. 1970); Pina v. Homsi, Civ. No. 69-666-G (N.D.

Mass., July 10, 1969); Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery, Civ.

No. 69-490 (N.D. Ala., Jan. 29, 1970), see 307 F. Supp.

369 (N.D. Ala. 1969); People v. Doughtie, Civ. No. 1150-S

(M.D. Ala., Nov. 18, 1971).

10/ The Richmond School Board does not challenge on this

appeal the amounts awarded by the district court. (See

A. 146-51);

Brotherhood of R. Signalmen v. Southern Ry. Co., 380

F.2d 59, 69 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 958 (1967).

- 12-

I

whether any award at all should have been made:

We can find no abuse of the District Court's

discretion in refusing to allow attorneys'

fees in a larger amount than it did.

Id. at 322. This Court has not had occasion to consider

whether, apart from traditional discretionary equitable

principles, e.g,, Gibbs v. Blackwelder, 346 F.2d 943 (4th

Cir. 1965), fees should normally be awarded in school

11/desegregation cases brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1983.

Nor will an affirmance here mean, as appellants

suggest, that "all school boards within this Circuit

would of necessity be obligated to pay attorneys' fees

to counsel for Plaintiffs in all desegregation cases

irrespective of their particular conduct." The Supreme

Court has enunciated the rule applicable where counsel

fees are to be awarded in furtherance of statutory policy:

. . . one who succeeds in obtaining an

injunction . . . should ordinarily recover

an attorney's fee unless special circum

stances would render such an award unjust.

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400,

402 (1968).

llAn Felder v. Harnett County Bd. of Educ. , 409 F.2d

1070 (4th Cir. 1969), this Court declined to award

attorneys' fees on an appeal pursuant to F.R.A.P. 38,

a rule of general application in non-civil rights

as well as desegregation cases, which requires a

finding that the appeal is frivolous. The same result

was reached in Walker v. County School Bd, of Brunswick

County, 413 F.2d 53 (4th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 396

U.S. 1061 (1970). However, in Nesbit v. Statesville

City Bd. of Educ., 418 F.2d 1040, 1043 (4th Cir. 1969),

this Court directed that plaintiffs-appellees in the

Halifax and Amherst County cases recover "their costs

and reasonable counsel fees, including reasonable out-

of-pocket expenses, to be determined by the district

judge."

-13-

Thus, it might be that plaintiffs might not be

entitled to counsel fees had they obtained an injunction

in January, 1970 requiring a school district which had

already achieved desegregation of all its schools' stu

dent bodies, to complete an already substantial faculty

desegregation program by reassigning faculty for the second

semester in accordance with the system-wide ratio, as

announced by this Court in December, 1969, Nesbit v.

Statesville City Bd. of Educ., 418 F.2d 1040 (4th Cir.

1969). That is not this case (see II infra).

Such a rule would substantially further suits by

"private attorneyfs] general," Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, Inc., id. at 402 n. 4. It will encourage

speedy resolution of school desegregation cases in which

school boards now gain premiums by delay, see Swann, 402

U.S. at 13-14, and it should help reduce the burden of

school litigation in the federal courts in the future.

The judgment below should be affirmed on the district

court's opinion.

II

The District Court's Award of Fees

Is Within Its Equitable Discretion

Apart from the necessity of counsel fee awards in

actions brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1983 to protect

the constitutional rights of black students, the judgment

below is a proper exercise of the "historic equity juris-

-14-

diction of the federal courts," Sprague v. Ticonic Nat11

Bank, 307 U.S. 161, 164 (1939); see also. Guardian Trust

Co. v. Kansas City Southern Ry. Co., 28 F.2d 233, 243-44

(8th Cir. 1928).

Such awards are discretionary, and the basis for

appellate review is a narrow one. "Questions of cost in

admiralty and equity are discretionary, and the action of

the Court is presumptively correct. United States v.

[Brig Malik) Adhel. 2 How. [(43 U.S.)] 210 [,237], 11 L.Ed.

237, 250." Newton v. Consolidated Gas Co.. 265 U.S. 78,

83 (1924). See also, Carlisle, Brown & Carlisle v.

, . 12/Carolina Scenic Stages. 242 F.2d 259, 260 (4th Cir. 1957).

It is significant that in the only instance in

which this Court has overturned a district court's dis

cretion as to such a matter, it directed that counsel

fees be awarded where they had been denied by the lower

court. Bell v. School Bd. of Powhatan County, 321 F.2d

494 (4th Cir. 1963). in several cases this Court has set

H 7 Even m Sprague, the Supreme Court implied that, had

the lower courts recognized their power to award fees

and costs but denied them in light of the particular

circumstances, the action would not have been an

appropriate one for review by the high court. 307

U.S. at 164, 170.

-15-

13/

aside awards of fees or costs on other grounds, and it

has also routinely affirmed lower court discretionary

11/denials of fee awards, but it has generally declined to

substitute its own judgment for that of the trial court.

11/Nor should it here.

13/in Specialty Equipment & Machinery Corp. v. Zell Motor

Car Co., 193 F.2d 515 (4th Cir. 1952), this Court antic

ipated the Supreme Court1s reasoning in Fleischmann

Distilling Co. v. Maier Brewing Co., supra, in reversing

the award of non-statutorily-taxable costs in a patent

case. In Sperry Rand Corp. v. A-T-0 Corp., 447 F.2d

1387 (4th Cir. 1970), this Court reversed a counsel fee

award in a trade secrets action, holding that the Court's

power to award fees was governed not by federal law

but by state law, which did not allow it.

14/E.g., Local No. 149, Int'l Union v. American Brake Shoe

Co., 298 F.2d 212 (4th Cir. 1962); Carlisle, Brown &

Carlisle v. Carolina Scenic Stages, 242 F.2d 259 (4th

Cir. 1957); cf. Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 345

F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965) (discretionary award of fees

affirmed but not raised in amount on appeal).

15/While the amount of the award here is larger than has

been taxed in some school desegregation cases, it is

not attacked by appellants; furthermore, in this action

involving "a long and complex set of hearings," Bradley

v. School Bd. of Richmond, 53 F.R.D. 28, 40 (E.D. Va.

1971), the award is consistent with the standards

approved by this Court:

In determining reasonable attorneys' fees,

factors to be taken into account are the

importance and complexity of the issue

being litigated, the quality of the legal

services, and the time required for prepara

tion and court appearances. The standards

applied in compensating attorneys for the

opposing party in litigating the self-same

issue give some indication of the importance

of the case and are a relevant consideration

in fixing the fee.

Brotherhood of R. Signalmen v. Southern Ry. Co., 380 F.2d

59, 69 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 958 (1967).

(See A. 146-51, 155).

-16-

In general, an equity court will exercise its dis

cretion to award counsel fees "for dominating reasons of

justice," Sprague v. Ticonic Nat'l Bank, supra, 307 U.S.

at 167. Civil rights cases in this and other Circuits

indicate that such litigation, brought to enforce rights

of individuals against the governmental bodies legally

obligated to protect those rights, will ordinarily call

for such an award, in the discretion of the lower court,

to do justice— but that appellate courts will interfere

with the district court's discretion only in the most

extreme circumstances.

In Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co.. 186 F.2d 473,

481 (4th Cir. 1951), a pre-Title VII employment discrimi-

16/

nation suit, the lower court found for the plaintiffs

and awarded them counsel fees. This Court upheld the

action as consistent with the Sprague principles:

. . .Ordinarily, of course, attorneys' fees,

except as fixed by statute, should not be

taxed as part of the costs recovered by the

prevailing party, but in a suit in equity

where the taxation of such costs is essential

to the doing of justice, they may be allowed

in exceptional cases. The justification

here is that plaintiffs of small means have

been subjected to discriminatory and oppres

sive conduct by a powerful labor organization

which was required, as bargaining agent, to

protect their interests. The vindication of

their rights necessarily involves greater

expense in the employment of counsel to insti-

16/Compare Lea v. Cone~Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86 (4th

Cir. 1971); Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971).

-17-

tute and carry on important litigation

than the amount involved to the individual

plaintiffs would justify their paying.

In such situation, we think that the allow-

ance of counsel fees in a reasonable amount

as a_ part of the recoverable costs of the

case is a matter resting in the sound

discretion of the trial judge . . . . (em

phasis supplied)

Rolax gave this Circuit's imprimatur to counsel fee

awards by district court in cases of great public im

portance involving discrimination; in Bell v. School Bd.

of Powhatan County, supra, 321 F.2d at 500, this Court

announced that in such cases, where the circumstances

were extreme, it would itself direct lower courts to

exercise their discretion to award fees. Even in the

dicta from Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 345 F.2d

310, 321 (4th Cir. 1965) so heavily relied upon by

appellants, this Court indicated it would act to disturb

a lower court's action only in compelling instances:

It is only in the extraordinary case that

such an award of attorneys' fees is requi

site. In school cases throughout the

country, plaintiffs have been obtaining

very substantial relief, but the only case

in which an appellate court has directed

an award of attorneys' fees is the Bell

case in this Circuit. Such an award is

not commanded by the fact that substantial

relief is obtained. Attorneys' fees are

appropriate only when it is found that the

bringing of the action should have been

unnecessary and was compelled by the school

board's unreasonable, obdurate obstinacy.

Whether or not the board's prior conduct

was so unreasonable in that sense was

-18-

initially for the District Judge to deter

mine. Undoubtedly he has large discretion

in that area, which an appellate court

ought to overturn only in the face of

̂ • • 1 1 7 / 1 ft /compelling circumstances. ±JJ> ±3/

No compelling circumstances are present here.

Rather, the history of this case would justify direction

19/of an award by this Court had none been made below. — '

We do not wish to duplicate the district court's compre

hensive opinion in this matter, 53 F.R.D. 28 (E.D. Va. 1971),

but in light of the representations of appellants' brief,

17/1t is significant to recall that in Bradley this Court

merely declined to increase the amount of attorneys'

fees awarded by the district court. It did not over

turn the award which was made by the lower court even

though it found some of the School Board's conduct

at that time was "commendable and exemplary," see

Brief for Appellants herein, p. 30 n.10.

18/Since 1965, the award of counsel fees in school

desegregation cases has become much more common;

the Bell case no longer stands alone. E.g., Clark v.

Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 449 F.2d 493, 499

(8th Cir. 1971).

19/ln Powhatan County— a rural school system in which

complete desegregation was relatively sir pie to

achieve— it was of course unreasonably obstinate for

the county school board to take no steps whatsoever

toward desegregation for as long as it did after

Brown. In Richmond, on the other hand— a large school

system in which complete desegregation would require

considerable planning and detail of execution— the

school authorities could avoid any real desegregation

without appearing so obstinate merely by tolerating

token desegregation and failing to take meaningful

steps toward eventual elimination of the dual system.

-19-

2 0/

we highlight below some of the events of this case,

indicating our differing viewpoints:

1966-70

On March 30, 1966, following remand from the Supreme

Court of the United States on the issue of faculty desegre

gation, Bradley v. School Bd. of City of Richmond, 382

U.S. 104 (1965), a consent decree was entered calling

initially for freedom of choice in Richmond. The school

board retained this method of student assignment until

1970 in spite of its lack of significant results (see

S.A. "B"),

and despite the Supreme Court's ruling in Green v. County

School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). In

its opinion awarding counsel fees, the district court noted

-i-2/Unlike appellants, who hypothesize four or five

distinct occurrences upon which the district court is

said to have "principally relied" (Brief, p. 19),

the court below did not purport to do more than set

forth a "few points relevant to the present motion. . ."

it generally summarized the Board's conduct as follows:

At each stage of the proceedings the School

Board's position has been that, given the

choice between desegregating the schools and

committing a contempt of court, they would

choose the first, but that in any event

desegregation would only come about by court

order.

53 F.R.D. at 30, 39. The lower court thus awarded fees

in consideration of all the circumstances, Bell v.

County School Bd. of Powhatan County, 321 F.2d at 500.

In contrast, appellants' approach seems to be to suggest

that each individual occurrence, considered alone,

would not warrant an award of counsel fees because some

other court had permitted some other school board to

escape paying counsel fees after having done something

analogous.

- 2 0 -

that " . . . since 1968 at the latest the School Board was

clearly in default of its constitutional duty." 53 F.R.D.

at 39.

Appellants argue that their adherence to free choice

could not support a counsel fee award for two reasons:

First, the plan had been entered pursuant to a consent

decree which plaintiffs had not sought to modify until

1970 (Brief, p. 20) and second, a 1969 decision of this

Court establishes that counsel fees are not to be awarded

for failure to eliminate free choice plans after Green.

The Board's first argument was presented to, and

rejected by, the district court (8/7/70 Tr. 18-19).

Similar arguments have been rejected by this and other

courts. Flemming v. South Carolina Elec. & Gas Co., 239

F.2d 277 (4th Cir. 1956); Hoiley v. City of Portsmouth,

150 F. Supp. 6, 7 (E.D. Va. 1957) ("Merely because the

City was acting in compliance with the prior order of

this Court affords no protection after the United States

Supreme Court placed a contrary interpretation on the

validity of the separate-but-equal doctrine. . . .") And

contrary to the suggestion of appellants, counsel fees

have been awarded where school boards sought to maintain

freedom-of-choice plans after their invalidity was made

clear by Green. E.g., Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of

Educ., supra; Kelley v. Altheimer, 297 F. Supp. 753, 758-

59 (E.D. Ark. 1969). Furthermore, it is hard to understand

- 21 -

how the School Board could believe the plaintiffs would

support free choice after Green since they had attacked

its sufficiency in the 1965 appeal to this Court! Bradley

v. School Bd. of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965).

What made the 1966 plan acceptable to plaintiffs

at the time it was entered by consent decree was its

affirmative provisions concerning both student and faculty

desegregation (A. 4-8):

. . . PROFESSIONAL PERSONNEL

3. In the recruitment and employment of

teachers and other professional personnel,

all applicants and other prospective

employees will be informed that the City of

Richmond operates a racially integrated school

system and that the teachers and other pro

fessional personnel are subject to assignment

in the best interest of the school system and

without regard to their race or color.

PUPILS

2. The pattern of assignment of teachers and

other professional staff among the various

schools will not be such that schools are

identifiable as intended for students of a

particular race, color, or national origin;

or such that teachers or other professional

staff of a particular race are concentrated

in those schools where al1 or the majority of

the students are of that race.

4. If the steps taken by the School Board do

not produce significant results during the

1966-67 school year, it is recognized that

the freedom of choice plan will have to be

modified with consideration given to other pro

cedures such as boundary lines in certain areas.

- 22-

Thus, even before the Green decision, the Richmond

School Board consented to the entry of a decree which

obligated it to meaningfully desegregate its faculties

and student bodies— and to replace freedom of choice if

that method did not work. Both before and after Green,

desegregation was minimal (see S.A. "A" and "B").

Yet the School Board

made no move to adequately desegregate ( A. 46) .

The school system had never made assign

ment across racial lines a condition of faculty employment

(A. 45).

Of course, the fact that plaintiffs did not move for

further relief or to modify the outstanding decree

between May, 1968 and March, 1970 hardly relieved the School

Board of the responsibility to comply with both the consent

22/, 23/

decree and supervening law.

jl/Cf. Research Corp. v7 Pfister Associated Growers, Inc.,

318 F. Supp. 1405, 1407 (N.D. 111. 1970) (awarding fees

in patent action pursuant to 35 U.S.C. §285, permitting

awards in "exceptional cases," where party did not

observe consent decree but collaterally attacked it).

22/The School Board was aware that plaintiffs' attorney,

who had been elected to the Richmond City Council in

the interim (A. 158-59), had a potential

conflict of interest which required his withdrawal (see

A. 8) ;

it was not until counsel experienced in these

matters, with time to devote to this cause could be

found, that plaintiffs were able to proceed in court to

protect their interests.

■23/Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Educ. , supra; Stanley

v. barlingt'on County School Dist.. 424 F. 2d 195 (4th

Cir. 1970); Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School Dist., 419 F.2d 1211, 1216 (5th Cir. 1969); United

States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County, 423 F.2d 1013

1014 (5th Cir. 1970).

-23-

Finally, the appellants' construction and applica

tion of Felder v. Harnett County Bd. of Educ., 409 F.2d

1070 (4th Cir. 1969) (Brief, p. 21) must also fail.

Felder is distinguishable for two reasons: first, this

Court was construing F.R.A.P. 38, authorizing the award

of counsel fees and double costs in "frivolous" appeals,

rather than prescribing the limits of a district court's

equity jurisdiction; second, Felder would not be control

ling where a school board had, as Richmond had, committed

itself to give up free choice if it did not produce

significant results. In any event, Felder should be con

trasted with Nesbit, supra. As the district court here

put it, the Richmond School Board's conduct must be measured

against judicial standards in early 1970 (post-Nesbit),

not early 1969 (post-Felder).

The 1970 Plans

After the Motion for Further Relief was filed,

according to appellants the school board "voluntarily

abandoned" free choice (Brief, p. 30). In fact, the

Board said only that it had "been advised" that its free-

choice plan would not comply with Green (see A. 9-11).

Only when pressed by the court

at a March 31, 1970 pre-trial conference did the Board's

attorneys concede, "reluctantly" (53 F.R.D. at 30), that

-24-

it would be futile to litigate the validity of free

choice.

At the hearing on the first 1970 plan submitted by

the school board, the Associate Superintendent testified

that under free choice, most students attended schools

located near their homes (A. 34-35),

but in response to an inquiry from the court, the Board's

attorneys would not concede that the failure of free choice

had any relationship to discriminatory housing patterns.

Cf. Brewer v. School Board of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th

Cir. 1968) (A. 47). The initial 1970

plan submitted by the Board followed Richmond residential

patterns with negligible improvement over free choice and

plaintiffs, therefore, had to formally prove segregated

24/

housing patterns in Richmond (53 F.R.D. at 30).

The first plan proposed by the Board in 1970 was

drafted at its request by the Department of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare, another step which appellants declare

showed their good faith (Brief at pp. 31-32). In fact,

the School Board looked to HEW only in order to relieve

itself of any responsibility ( see A. 45) for bringing

about desegregation; it gave no instructions to HEW ( A. 43) ,

-25/The"-Board^s attorneys refused to agree to stipulations

tendered by plaintiffs (see Appendix A to this brief)

which would have obviated much of this proof. Compare

317 F. Supp. at 561-63.

-25-

it weakened the already ineffective MEW

plan ( A. 43-45) which had been drawn without using

the tools (A. 40-42) which the school authori

ties themselves knew would be necessary to desegregate

their system (A. 60-63), and the Board

itself never even considered the use of such tools ( A.

46) . The district court very properly disapproved

a plan which was so ineffectual (see A. 18-30)

that it should

never have been submitted ( A. 63-69; 53 F.R.D. at 31).

While appellants now claim the plan is inadequate

only by hindsight (Brief at page 32) and make much of

this Court's Spring, 1970 decisions in Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.. 431 F.2d 138, and Brewer v.

School Bd. of Norfolk. 434 F.2d 408 (Brief, pp. 22-24),

the invalidity of the "HEW" plan was already clear under

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk. 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir.

1968) and Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County.

391 U.S. 430 (1968). See, e.g., Henry v. Clarksdale

Municipal Separate School Dist.. 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.),

cert- denied, 396 U.S. 940 (1969); Clark v. Board of Educ.

of Little Rock. 426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970), cert.

denied. 402 U.S. 952 (1971).

-26-

The Board's discussion of its second 1970 plan (Brief,

pp. 24-26) is illustrative of the manner in which appel

lants have distorted the history of this case. The Brief

states that "[i]n retrospect the District Court has

characterized the Interim Plan as being glaringly inade

quate in that it left substantial numbers of students in

virtually all-white or all-black elementary schools,"

but it suggests that the plan must have been acceptable

at the time it was submitted because this Court, in its

1970 Swann opinions, had not required the elimination of

every all-black school. In fact, the second 1970 plan

left 12 elementary schools more than 90% black and 7 ele

mentary schools more than 90% white (A. 88) even

though with the use of transportation, specifically

endorsed by this Court in Swann (431 F.2d at 144-45), all

could have been desegregated (a . 91) (see

A. 83-85).

The plan did not receive the support

of the black school board members because of this inade

quacy ( A. 89-90) .

There is no inconsistency in the district court's

action, as the appellants imply in these two sentences

(Brief for Appellants, p. 24):

The District Court found that the plan

submitted by the School Board in July,

1970, was further evidence of its

intransigency. However, this same plan

was ordered for implementation on an

interim basis for the 1970-71 school

year.

-27-

The plan was ordered implemented for the 1970-71 school

year only because the school district did not have

sufficient transportation resources to implement, by

September, 1970, the plaintiffs' plan (found fully

25/

constitutional by the district court). The lower court

found the school system's stubborn refusal to take steps

toward acquiring transportation capability, a refusal

which directly resulted in the necessity of implementing

a less than constitutional plan for 1970-71, to be the

more remarkable in light of the school administrators'

consensus that an adequate desegregation plan for Richmond

would require busing (53 F.R.D. at 32).

The confusion and uncertainty touted by appellants

was nothing less than a vain hope that the federal courts

would turn their backs upon black citizens, and halt the

desegregation process. If integration of the schools was

to become a reality, there could be no doubt that the

Supreme Court would authorize the use of such a traditional

educational tool as busing. In similar circumstances.

-̂ -5/it was in this sense only that the district court

considered the plan "reasonable" under Swann: for

without additional transportation resources (which

could not be purchased by September), implementation of

plaintiffs' plan would have required, for example,

"unreasonable" staggering of opening hours. The

district court's opinion specifically held the Board's

plan did not meet existing constitutional standards,

317 F. Supp. at 574-75. Compare the Board's Brief at p.32

Regardless of how the District Court viewed

the conduct of the School Board in proposing

this Interim Plan, the fact remains that the

plan was approved for use in the 1970-71

school year on an interim basis because it

fulfilled the test of reasonableness under

Swann.

-28-

a Mississippi district court awarded attorneys' fees

in a reapportionment suit against county officials who

insisted upon waiting from Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533

(1964) until Avery v. Midland, 390 U.S. 474 (1968) to

end malapportionment in local representation. Dyer v.

Love, 307 F. Supp. 974, 986-87 (N.D. Miss. 1969).

-29-

School Construction

After the Motion for Further Relief was filed, discovery-

revealed an ongoing construction program (S.A. "D");

because of

the long-range effects of school construction upon

desegregation, Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-21, plaintiffs sought

reexamination of the program after a desegregation plan

had been approved. (A. 31-33).

The testimony showed that school

sites in question were selected without regard to race or

effect upon desegregation (A. 34, 37, 39-40)

even though school

authorities were aware that in fact the new schools were

planned in areas of racial concentrations and would

probably be one-race schools (A. 38-39).

The district court enjoined

all new construction pending a convincing demonstration

by the school board that it would further integration

rather than perpetuating segregation (A. 47-59).

Following the hearings in the summer of 1970, after

which the board's second 1970 plan was approved for

implementation only for the 1970-71 school year and the

board directed to prepare a fully constitutional plan,

30

counsel for plaintiffs were notified that the board

wished to proceed with some nine school construction

projects, and an oral motion to lift the injunction was

made. The parties agreed to submit evidence by deposition.

As the lower court has put it,

The evidence disclosed that the School Board

had not seriously reviewed the site and capacity

decisions which it had made, according to earlier

testimony, without consideration of their impact

on efforts to desegregate.

53 F.R.D. at 32; see 324 F. Supp. 461. Plaintiffs expert

witness, m fact, performed such a review and based upon

his conclusion plaintiffs offered no objection to three

sites. (see A. 95-96, 108-10).

The district court formalized the agreement by lifting

the injunction. But the implications of the Board's Brief

are decidedly misleading. At pp. 7-8 they fail to mention

that the construction permitted was that to which plain

tiffs agreed and for which an explanation that desegre

gation would not thereby be impeded was offered by plain-

^ ffs' expert witness. At p. 28 they state: "The fact

remains that portions of the injunction were vacated."

31

But this had little to do with the conduct of the Board

or school authorities; appellants' misleading descriptions

of the entire adventure in their Brief are a notable

example why deference is given lower court findings.

The 1971 Plans

The district court's order, approving the Board's

second 1970 plan for that school year only, required the

Board to propose the additional steps needed to completely

desegregate the Richmond schools, and the earliest possible

date for their implementation, by November 15, 1970 (A.

93-94; S.A. "E").

On that date, the Board's counsel advised the Court by

letter that plans would not be ready until January, 1971

(A. 103-08).

Accordingly, plaintiffs sought

to have their plan implemented for the second semester

of the 1970-71 school year (A. 110-12).

The district court denied

that motion on January 29, 1971. 324 F. Supp. 456. It

noted that although the Board was aware that it would need

buses for eventual complete desegregation, it had taken

no steps to acquire them (The court recognized that it

had not ordered the Board to do so). Thus second-semester

32

implementation of plaintiffs' plan was still fraught with

the same difficulties as it had been in August, and the

question came down to whether the court should order the

Board to purchase buses for second-semester implementation

of plaintiffs'plan.

The district court ruled that it would not require

this. It noted that since its August ruling, the Swann

cases had been argued before the Supreme Court and the

Courts of Appeals had postponed disposition of all pending

appeals in school desegregation cases in anticipation

of a Supreme Court ruling. Under these circumstances, the

court declined to require purchase of buses (324 F. Supp.

456). However, with respect to this episode, the court

noted in its opinion awarding fees (53 F.R.D. at 33):

The fact remains, nonetheless,

that the School Board had made

effective and immediate further

relief nearly impossible

because it had not taken the

specific step of seeking to

acquire buses. This policy

of inaction, until faced with

a court order, is especially

puzzling in view of represen

tations later made by counsel

for the School Board to the

effect that at least fifty-

six bus units would have to

be bought, in the Board's

view, in order to operate

under nearly any possible

plan during the 1971-72 ,

school year. — /

pr /

— ' Appellants make far too much of this comment (Brief,

pp. 26-27). The district court did not award plaintiffs

counsel fees because the Board failed to buy buses during

33

Thereafter, the Board filed a new plan in conformity

with the August 17, 1970 order. It submitted three plans

one, based upon contiguous geographic zoning only, was

similar in operation and effect (no desegregation) to the

26/ (Cont'd)

1970. This example, and others like it, demonstrate the

district court's basic point that the Board's consistent

approach was an extremely reluctant one: it would do

nothing unless specifically ordered. See n.20 supra.

While some of the Board's reticence was arguably justi

fiable (such as its failure to purchase buses in time

for second-semester implementation of plaintiffs1 plan),

much of it is not (such as its reliance upon the 1966

decree to support continued adherence to a totally in

effective freedom-of-choice plan). But the Board liti

gated arguable points and settled law with equal vigor.

As the lower court said (53 F.R.D. at 39) (emphasis

supplied):

It is no argument to the contrary

that political realities may compel

school administrators to insist

on integration by judicial decree

and that this is the ordinary,

usual means of achieving com

pliance with constitutional

desegregation standards. If

such considerations lead

parties to mount defenses

without hope of success,

the judicial process is none

theless imposed upon and the

plaintiffs are callously put

to unreasonable and unnecessary

expense.

34

Board's first 1970 plan. The Board was aware that it was

unacceptable under settled legal principles.

The second plan was similar to the one implemented

in 1970-71, which the district court had already ruled

would be insufficient for 1971-72. But the Board sought

approval of this plan on the ground that it had appealed

to this Court, the district court's August, 1970 order

rejecting it for permanent use--despite the fact that

the Board itself had then sought to delay disposition of

that appeal, over plaintiffs' objection, until the Supreme

Court announced its Swann decision ( A. 137).

Thus, had the district court approved that plan

on these grounds, the Board would have succeeded in post

poning desegregation again as a result of its own delay

and inaction.

The third plan, now in effect in Richmond, utilized

all the techniques recommended by plaintiffs' expert to

completely desegregate the schools. The Board did not,

however, support adoption of this plan and plaintiffs were

required to respond to all the plans (A. 138-40).

After a full hearing March 4, 1971 at which plaintiffs’

35

counsel elicited testimony, the district court rejected

the first two plans submitted by the Board and ordered

the third into effect for the 1971-72 school — including

the requirement that the Board acquire sufficient pupil

transportation capability to effectuate the plan at that

time (325 F. Supp. 828).

Appellate Proceedings

Appellants claim they have been very restrained in

using appellate processes for delay (Brief, pp. 35-36).

The argument seems to be that the Board could have been

even more obstructive and delay-seeking than it was. We

bring a few points to the Court's attention. First, the

appellants state that "[wjhile justifiably appealing the

District Court's decision to the effect that its Interim

Plan was a nonunitary one, the School Board nevertheless

declined to seek any stay . . . ." it did not have to do

so, for the Richmond City Council and the City of Richmond

(which had been added as defendants upon motion of plain

tiffs to insure effective implementation of any plan)

did so — carrying their request to the Supreme Court of

the United States, where it was denied. (The district

court explicitly did not award fees for this part of the

litigation, 53 F.R.D. at 43 n.8). The School Board, which

36

now claims to have been so solicitous of plaintiffs' rights,

did not oppose such a stay.

Second, appellants point to their withdrawal, after

Swann, of their appeal from the August, 1970 decree (Brief,

p. 35). In fact, that appeal would have been moot in

light of the district court's April 5, 1971 Order approving

a new plan, Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 429

F.2d 11 (6th Cir. 1970), and no benign or malevolent pur

pose can be read into the dismissal.

Third, the modification of the lower court's April 5,

1971 Order sought by the Board would have had exactly the

same effect as a stay; its motion was pending when Swann

was decided. In any event, the district court's order

had not required anything but orderly implementation of

Plan III. Once again, the Board's conduct could only

serve to delay.

Joinder of Surrounding Counties

Finally, we add a word about the Board's action in

seeking to consolidate Richmond with suburban county

school systems (Brief, pp. 36-37). Appellants venture that

it is probable that no other

urban school board has

expended such effort to

bring fulfillment to its

belief as to the promises

of Brown I and II.

37

Of course, a school system so dedicated to the constitutional

rights of all its schoolchildren need not have waited for

court orders to desegregate its schools. E.g., McDaniel

v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971); cf. North Carolina State

Bd. of Educ. v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971); and see Wanner

v. County School Bd. of Arlington County, 357 F.2d 452

(4th Cir. 1966).

The district's interest in consolidation is but a

continuation of its course of attitude and conduct since

the inception of this lawsuit. Having delayed and resisted

integration as long as it could, the Board realized when

the HEW plan was rejected that school integration in

Richmond would be a reality. It then sought immediately

to blunt what it considered to be the unfavorable impact

of integration by bringing more white students into the

system--all the while denying that plaintiffs' constitutional

rights were or had been abridged (see A. 76-78).

The Board's interest in consolidation is because

of its fear of white flight and its dislike of an integrated

but majority-black school system. See Brunson v. Board of

27/Trustees, 429 F. 2d 820 (4th Cir. 1970) (concurring opinion) .—

The "delay" referred to in n. 16 of the appellants'

Brief was due to the involvement of counsel for plaintiffs

in another case. The trial was ultimately postponed from

39

From the outset of this case appellants have represented

and protected their perceived social interests of

Richmond's white population, not the constitutional

rights of all its citizens. Thus as late as January, 1971,

the Board still denied it had ever done any constitutional

wrong (A. 124-28).

A perusal of the Amended Complaint filed by the

plaintiffs against the adjoining county school systems

(A. 113-23)

will reveal that plaintiffs 1 claims are far broader than

the Board's. Plaintiffs have no objection to an integrated

majority-black school system but are concerned with pal

pable constitutional violations in the maintenance of the

separate school systems around Richmond. The coincidence

that both plaintiffs and the Board now support some form

of merged school system in the Richmond area does not in

any way imply that the Board's interest is the protection

27/ (Cont'd)

the end of April, 1971 until the middle of August, 1971.

Plaintiffs sought the additional time so that they might

adequately present their case. The Board sought a quick

trial in the hope that it could avoid implementing the

desegregation plan for Richmond City at all. The case

has not yet been decided by the lower court.

40

of the constitutional rights of black school children.

CONCLUSION

We invite this Court to carefully study the entire,

voluminous record in this matter. Such a review will

reveal no compelling circumstances for overturning the

lower court’s counsel fee award in this case or for con

eluding that the award was unjust.

We respectfully pray that the lower court's decree be

affirmed and plaintiffs awarded their costs and reasonable

counsel fees on this appeal.

Respectfully ̂ bmitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NAB^IT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

LOUIS R. LUCAS

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

JAMES R. OLPHIN

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

M. RALPH PAGE

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

41

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 3rd day of

January, 1972, two copies of the foregoing Brief for

Appellees were served upon counsel for the appellants

herein, by mailing a copy of same via United States

mail, first class postage prepaid, to:

George B. Little

John H. O'Brion, Jr.

James K. Cluverius

Browder, Russell, Little and Morris

1510 Ross Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

and to:

Conard B. Mattox

City Attorney

402 City Hall

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Following preparation of the deferred appendix,

two copies of this Brief with altered citations to the

Appendix and Supplemental Appendix, see n. 1 supra,

were served upon counsel above the 23rd day^pf February,

1972.

-42-

Iff TulS UNITCl) B 'i 'A T ,lU 'R T lilC T COURT

l1 Oi{ TilJi iSACTBRH DISTRICT OF V I I iCJINIA

RICHMOND D I. VIRION

CAROLYN BRADLEY and

MICJALL UiiiVDLUY, infants, et ul. e tc .,

C IV IL ACTION

NO. 3353

STIPULATION ON COIINgKL HO. 1

I t Is hereby agreed by and between counsel for the

parties herein, that the following facts are true:

Restrictive covenants in the deeds for residentia l

property including subdivision tracts continued to be recorded

in the City of Richmond for a number of years a fte r they were

struck down by the Supreme Court in Shelley v. Kraomer. 334 U.S.

1 (1943). Many of the deeds to residentia l property in the

City of Richmond contain rac ia l re s tr ic tive covenants. Some of

these covenants contain a reverter condition which requires a

release from a trustee, and some of the restric tions w il l not

expire u n til 1997. The extra expense of securing Q release

ranges from $20. to $73- per deed. U n til 1967 , rea l estate sales

in the Richmond dally newspapers were lis ted separately for whites

and blacks. Black real estate brokers could not advertise any

property for sale except in a column designated, "For Bale to

Colored." Black real estate brokers were not permitted to

advertise property in white neighborhoods for sale in the "For

Sale to Colored" column even though the owner may have requested

them to s e ll to colored. Black brokers are further lim ited in

t; '' t-Ncy can offer for sale because U,.„ nave not been

permitted to become members of the Richmond BoarJ of Realtors

and thus to have access to multiple l is t in g services, e tc ..

* _- / Attorney for Plaintiffs

f\ PPfT/lL> (y Attorney tor Defendants

U U . i l i , . .■ r.: . . . J > o l t - * . - 1C - * * C O i t . i .

i U-?» V ’ ", A •! s' - ... hi.;... ...) CP O.1 /.I i -j I X A

RTC;!i-:o:.D t>tv.tg ic :j

ca .g l . b ■;/ cudfile LV. .1, jj-U .AT , ii i C;:u L;>, etc.,

et Jil.

ve.

TIU SCHOOL. LO.Y.'J) OP T.Vi CXTI OF

RICilMOMD, V3 dUIMJA, c t a l .

CIVIL ACTIOiJ

XTO. 33f>3

STIPUT.Yi’T0*.T OF OOIFt.S: - h 'TO. 2

Xt ic hereby agreed by arid between conned lo r the

pr.rti.eo herein, that the following facts are true:

Uegro residences arc concentrated in particu lar

eectlone of the City of Rich;.and ca a resu lt of both public

r,,r private actions. City zoning ordinances d ifferentiate

between Mae it ar/1 white residentia l areas. Zones for black

areas generally permit denser occupancy, while most white areas

are zones for restricted land usage. Urban renewal projects,

supported by heavy federal financing and the active participation

of local government, contributed substantially to the c ity 's

ra c ia lly segregated housing patterns., line R ich u L i City School

Roar.:, pursuant to Sts to-re nulled legal cegregat’. on and policy,

practice, custom and usage located and expanded -drools in black

residentia l areas and fixed the size of the sc1k >1» to accommodate

these areas of rac ia l concentration. Predominantly black schools

were the inevitable resu lt.

Attorney for P la in t if fs

Attorn / for Defendants