Baker v. Jefferson County Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 14, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Baker v. Jefferson County Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1980. 567a1e9e-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/da338492-b73f-402c-9c07-58cce8de4e05/baker-v-jefferson-county-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

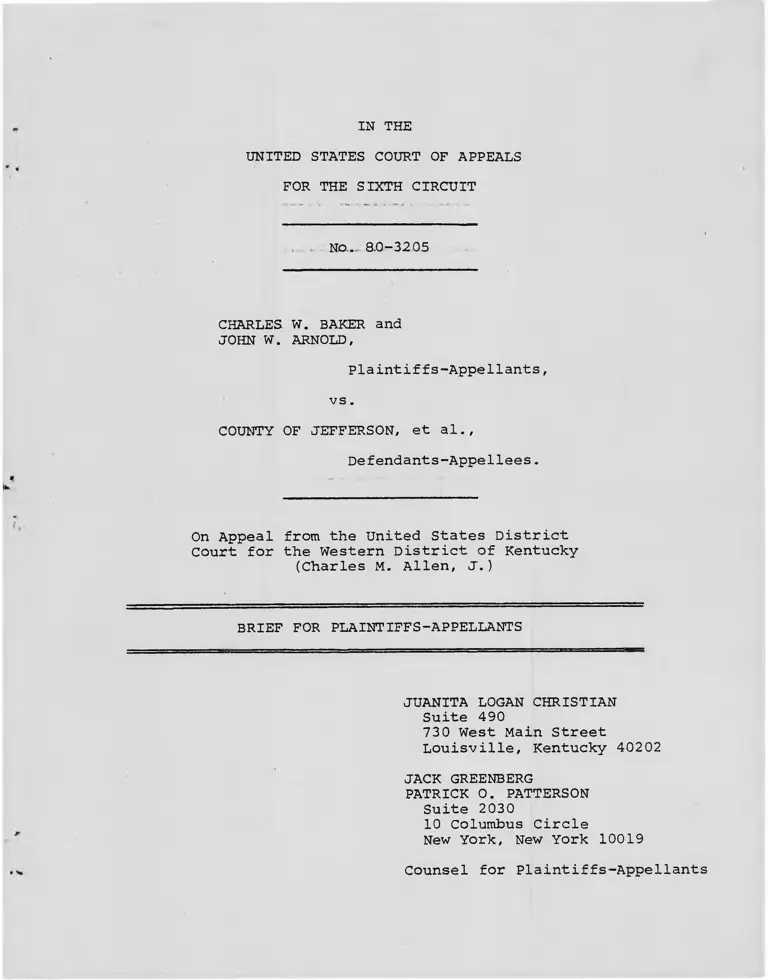

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO... 8.0-3205

CHARLES W. BAKER and

JOHN W. ARNOLD,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

COUNTY OF JEFFERSON, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Western District of Kentucky

(Charles M. Allen, J.)

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JUANITA LOGAN CHRISTIAN

Suite 490

730 West Main Street

Louisville, Kentucky 40202

JACK GREENBERG

PATRICK O. PATTERSON

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Table of Contents

Page

Table of Authorities ............................... ii

Questions Presented .... 1

Statement of the Case .............................. 2

Statement of Facts ................................. 3

Summary of Argument.... ............................ 15

Argument ........................................... 16

I. The district court misconstrued

Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 ...... 16

A. Standards of proof ................. 16

B. The district court erred as

a matter of law in holding

that an employer may lawfully

retaliate against employees

because they have accused

their supervisors of racial

discrimination ..................... 18

C. The district court erred as

a matter of law in holding

that an employer may lawfully

retaliate against an employee

because he has supported a

co-worker's claim of dis

criminatory treatment .............. 23

II. The district court based its

decision on clearly erroneous

findings of fact ........................ 26

III. The district court abused its

discretion in denying the motion

for a preliminary injunction ........... 35

Conclusion .......................................... 40

Addendum: § 704(a), Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-3(a);

Civil Rights Act of 1866,

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ........................ 41

- i -

Table of Authorities

Cases; Page

Aguirre v. Chula Vista Sanitary Service,

Inc., 542 F . 2d 779 (9th Cir. 1976) .............. 16, 17,

35, 36, 39

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415

U.S. 36 (1974) .................................. 23

Berg v. La Crosse Cooler Co., 612 F.2d

1041 (7th Cir. 1980) ............................ 19, 20

DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak Co., 511 F.2d

306, modified on other grounds, 520

F .2d 409 (2d Cir. 1975) ...................... 21, 24

Eichman v. Indiana State University

Board of Trustees, 597 F.2d 1104

(7th Cir. 1979) ................................. 25

Federoff v. Walden, 17 FEP Cases 91

(S.D. Ohio 1978) ............................ 25, 35, 37

Garcia v. Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's

Medical Center, 80 F.R.D. 254

(N.D. 111. 1978) .............. 24

Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 622 F.2d

43 (2d Cir. 1980) ............................... 16, 17

Gresham v. Chambers, 501 F.2d 687

(2d Cir. 1974) .................................. 35

Hearn v. R.R. Donnelly & Sons Co.,

460 F. Supp. 546 (N.D. 111. 1978) .............. 20, 21

Hearth v. Metropolitan Transit

Commission, 436 F. Supp. 685

(D. Minn. 1977) ................................. 20, 21

Kirkland v. Buffalo Board of Education,

487 F. Supp. 760 (W.D.N.Y. 1979)

aff'd, 622 F .2d 1066 (2d Cir. 1980) ............ 16

Liotta v. National Forge Co., 473

F. Supp. 1139 (W.D. Pa. 1979) .................. 24

-ii-

Page

Mason County Medical Ass'n v. Knebel,

563 F. 2d 256 (6th Cir. 1977) .................. 35, 36

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973) ............................ 16, 20

National Organization for Women v.

Sperry Rand Corp., 457 F. Supp. 1338

(D. Conn. 1978) ................................ 24

Novotny v. Great American Federal Savings

& Loan Ass'n, 584 F.2d 1235 (3rd Cir.

1978) (en banc), vacated on other grounds,

442 U.S. 366 (1979) ............................ 19,20, 24

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

411 F .2d 998 (5th Cir. 1969) .................. 19

Ragheb v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of

Michigan, 467 F. Supp. 94 (E.D. Mich.

1979) ........................................... 24

Senter v. General Motors Corp., 532 F.2d

511 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 429 U.S.

870 (1976) ...................................... 22

Sias v. City Demonstration Agency, 588

F . 2d 692 (9th Cir. 1978) ...................... 19, 20

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc.,

396 U.S. 229 (1969) ............................ 25

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 624 F.2d 525

(5th Cir. 1980) ................................ 22, 34

United States v. United States Gypsum Co.,

333 U.S. 364 (1948) ............................ 34

Winston v. Lear-Siegler, Inc., 558 F.2d

1266 (6th Cir. 1977) ........................... 21, 24

Womack v. Munson, 619 F.2d 1292 (8th

Cir. 1980) .................................... 16, 19, 21

Statutes and Rules;

28 U.S.C § 1292 .................................. 3

-iii-

Page

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C.

§. 1981 ........................................... Passim

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e et seq.......... Passim

Rule 52, Fed. R. Civ. P................. 34

Rule 65, Fed. R. Civ. P. ......................... 35

-iv-

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No... 80-3.205.

CHARLES W. BAKER and

JOHN W. ARNOLD,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

COUNTY OF JEFFERSON, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Western District of Kentucky

(Charles M. Allen, J.)

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Questions Presented

1. Whether the district court erred in holding that

an employer may lawfully retaliate against employees

because they have accused their supervisors of racial dis

crimination.

2. Whether the district court erred in holding that

an employer may lawfully retaliate against one employee

because he has supported another employee's claims of dis

criminatory treatment.

3. Whether the district court based its decision on

clearly erroneous findings of fact.

4. Whether the district court abused its discretion

in refusing to grant a preliminary injunction protecting

the plaintiffs from unlawful retaliation.

Statement of the Case

This case was brought as a class action in January

1980 under, inter alia, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, to remedy racial

discrimination in employment in the Police Department of

Jefferson County, Kentucky. The plaintiffs also sought a

temporary restraining order and preliminary and permanent

injunctions protecting plaintiffs Charles W. Baker, John

W. Arnold, and other employees from retaliation for their

opposition to the defendants' racially discriminatory prac

tices. The district court initially granted a temporary

restraining order (order of Jan. 25, 1980) but, after a

hearing, dissolved that order and denied plaintiffs' motion

for a preliminary injunction (order of March 4, 1980). This

Court has jurisdiction of plaintiffs' appeal pursuant to

- 2 -

28 U.S.C. § 1292 (a) (1) .

Statement of Facts

Plaintiff Charles W. Baker, who is black, joined the

Jefferson County Police Department as a Class A Patrolman

in 1972 and became a plainclothes detective in 1973. Tr.

Vol. I, at 13, 24 (Baker). Except for a brief period in

1977, during which he first served in the Department's

training unit and then temporarily left the police force,

plaintiff Baker remained a detective until January 1980,

shortly before this suit was filed, rd. at 24. Before

joining the Jefferson County Department, he had worked as

a police officer in both Washington, D.C., and Louisville,

Kentucky, and before that he had been in the U.S. Marine

Corps for ten years. Id_. at 13-14. Plaintiff Baker also holds

a Doctor of Divinity degree (Tr. vol. I, at 14); he serves

both as the pastor of a church (id_. at 13) and as a volun

teer chaplain for the Police Department (Helm Dep. at 18-

19). His Police Department personnel file (PX 11)

contains 14 letters of commendation from his commanding

officers, private.citizens, and others; it contains only

one letter of reprimand, which was issued in 1974 because

he was overweight.

Plaintiff John W. Arnold, who is white, has been an

officer in the Jefferson County Police Department since

1968. Tr. Vol. I, at 199 (Arnold). He served as a nar

cotics detective in 1972-73 (id. at 200; Vol. II, at 6),

-3-

and he became a burglary bea-t detective and then a homicide

detective in 1977 (Tr. Vol. I, at 201-202). His personnel

file (PX 18) contains 26 letters of commendation from his

commanding officers, private citizens, and others. The

file shows that he was the subject of formal discipline

only once: in 1974, he received a letter of reprimand

because his hair needed trimming..

In the fall of 1978, Detectives Baker and Arnold were

selected to work as a team in a new burglary intelligence

unit funded through a federal grant administered by the

Louisville/Jefferson County Criminal Justice Commission.

Tr. Vol. I, at 202 (Arnold); PX 20, at 3. The primary

purpose of the unit was to reduce residential burglaries

by means of new and inventive methods of crime prevention,

apprehension of burglars, and recovery of stolen property.

PX 20, at 3-4. Unlike other detectives in the residen

tial burglary squad, Baker and Arnold were not assigned to

specific geographical areas or beats, but were responsible .

for conducting surveillance and gathering intelligence

throughout Jefferson County and surrounding areas. Tr.

Vol. I, at 202-203 (Arnold); Vol. IV, at 1-3 (Whalin).

Detectives Baker and Arnold were selected for the new

unit in 1978 because the lieutenant in charge of the unit

regarded them as the best qualified persons in the Department

to fill these two positions. Tr. Vol. I, at 202 (Arnold).

They remained in the unit until January 1980, shortly before

-4-

this suit was filed. When the unit was evaluated in

November and December of 1979, the staff of the Criminal

Justice Commission found that Baker and Arnold were

"enthusiastic about the project," that they had logged

"an impressive amount of surveillance time," and that

"there was nothing that we found to be lacking" in their

performance. Tr. vol. IV, at 206-207 (Bewley). A month

later, however, Baker and Arnold not only were removed

from the burglary intelligence unit, but were demoted from

detectives to uniformed patrol officers. Tr. vol. I, at 68-

70 (Baker), 236-37 (Arnold).

The events which culminated in Baker's and Arnold's

demotion began in April 1979, when plaintiff Baker filed

a charge of discrimination with the U.S. Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission and the Kentucky Commission on

Human Rights. A copy of the charge was served on the

Chief of Police (Helm Dep. at 14), and the fact that it

had been filed was common knowledge within the Department.

Tr. Vol. I, at 19-20 (Baker); Vol. Ill, at 87 (White);

Vol. V, at 13 (Hall). Another black officer, Detective

Bruce White, considered filing a charge of discrimination

at the same time but decided against it because he feared

retaliation by the defendants. Tr. Vol. Ill, at 86-87 (White).

Baker's charge (PX 1) alleged that he and other black

officers had been denied promotions to higher ranks in the

Police Department because of their race; it further alleged

-5-

that less than 3% of the officers in the Department were

black, and that no black person held any position aboveuthe rank of patrol officer. By contrast, in 1970 blacks

accounted for 13.8% of the population of Jefferson County

and 12.2% of the population in the Louisville Standard

yMetropolitan Statistical Area. At the time of the February

1980 hearing in this case, blacks held only 12, or 2.7%,

of 450 jobs as sworn officers in the Department (Helm Dep.

at 12; Tr. Vol. I, at 17 (Baker)); of approximately

71 commanding officers, only one was black. This sole

black sergeant, J. C. Carter, had been promoted to that

rank late in 1979, several months after plaintiff Baker

had filed his charge of discrimination. Helm Dep. at 12-14;

Tr. Vol. I, at 194 (Baker). Carter is the only black person

who has ever attained the rank of sergeant in the entire

history of the Jefferson County Police Department. Id.

After Baker filed his EEOC charge, he was subjected

to racial harassment and intimidation by other officers in

the Department, and he experienced an increasing level of

hostility and criticism from his commanding officers. For

example, soon after the charge was filed in April 1979,

Detective Jack Wright, told Baker that he had heard about

1/ Two black applicants who were denied jobs as police

officers in the Department, Ronald Coley and Purgie Mack,

also filed charges of discrimination. They are plaintiffs

in this action but are not directly involved in this appeal.

2/ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census Tracts, Louisville, Ky.

Ind. Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area, Table P-1 (General

Characteristics of the Population: 1970).

- 6 -

it and said, "You know, we've never had a nigger to retire

on the Police Department yet, and I see that you're killing

your chance right now of doing so." Tr. Vol. I, at 20-21

(Baker), 205-206 (Arnold). Baker also received several

threatening calls over the Police Department's intercom

system telling him, "Nigger, you'd better drop that suit."

Id. at 21-23 (Baker). Lt. David Whalin, who assumed command

of Baker's squad in June, told Baker in July that he was no

longer permitted to hang his Doctor of Divinity degree above

his desk. Tr. Vol. I, at 30-33 (Baker). Other detectives

in comparable offices were allowed to hang pictures, degrees,

and awards on the walls (id_. at 33-35), and as late as

November 1979 other officers in squad rooms under Lt. Whalin's

command were permitted to hang things on the walls. Tr. Vol.

IV, at 146-47 (Brodt). Baker's immediate supervisor, Sgt.

Edward Brodt, openly criticized Baker's work and called it

"garbage" in the presence of another detective junior to

Baker. Tr. Vol. I, at 35-39 (Baker).

Baker testified that, after several such incidents had

occurred, "I knew that I was headed for some problems back

there in Burglary. I was either going to be gotten rid of

or fired or something ...." Tr. Vol. I, at 67. Therefore,

in August 1979 he went to Col. Helm, the Chief of Police,

and requested a transfer from the burglary intelligence

unit to the chaplain's office. Chief Helm denied his request

on the ground that there was no one available to replace him

in the burglary intelligence unit. Id.

-7-

By January of 1980, the hostility directed at Baker

by his commanding officers had intensified. On January

2, Sgt. Brodt orally reprimanded Baker for failing to

appear on New Year's Eve at an invesitgative detail to

which Baker had never been assigned. Tr. Vol. IV, at 135-36

(Brodt); vol. I, at 41-43 (Baker). The detail resulted

from information which had been developed by Arnold. Tr.

Vol. I, at 231 (Arnold). However, Sgt. Brodt had not

assigned Arnold to the detail even though Baker and Arnold

worked as a team, and he had attempted to reach only Baker

on New Year's Eve. Tr. vol. IV, at 135 (Brodt). Both

Baker and Arnold were on vacation on the date in question,

their vacation requests having previously been approved

by Sgt. Brodt himself. Tr. Vol. I, at 41-43 (Baker), 232

(Arnold). Although both Baker and Arnold were present at

the time of the reprimand, only Baker was reprimanded. Id;

see also, Tr. Vol. IV, at 135-36 (Brodt).

Then, on January 7, Sgt. Brodt and Lt. Whalin repri

manded both Baker and Arnold for allegedly failing to

follow Sgt. Brodt's instructions when they made arrests

without notifying Detective Michael Doughty, a white bur

glary detective. Tr. Vol. IV, at 30-31 (Whalin). The

record shows that Sgt. Brodt had instructed them to notify

the detective assigned to a particular beat before making

any arrests on that beat, and to include that detective in

any such arrests. Tr. Vol. I, at 43-44 (Baker), 226 (Arnold).

- 8 -

When Baker and Arnold began investigating a series of

burglaries in December 1979, they believed that the sus

pects had committed crimes on Detective Doughty's beat.

In accordance with their sergeant's instructions, they

communicated their findings to Doughty and they gave

Doughty leads, suggestions, and photographs to assist

him in his own investigation. Tr. Vol. IV, at 136-37

(Brodt); Vol. I, at 222-24 (Arnold). When Baker and

Arnold learned through further investigation that the

suspects had in fact committed burglaries on the beat of

Detective Bruce White (a black detective) and. not on

Detective Doughty's beat, they continued to follow the

instructions they had been given: after telling Sgt.

Brodt what they were planning to do, they notified

Detective White, they gave him the information they had

developed in their investigation, and they involved him in

the arrests. Tr. Vol. I, 43-48 (Baker), 226-28 (Arnold).

Despite their compliance with the procedures they were

directed to follow, on January 7 Baker and Arnold were

reprimanded for their conduct.

Baker's growing concern about his future in the Depart

ment prompted him to write his letter of January 9, 1980,

to Chief Helm (PX 7). The letter recounted the facts of

the New Year's Eve incident and the Doughty incident, and

it stated as follows (id. at 4):

-9-

It is obvious that this action is aimed

against me because I am black. The lieutenant

and sergeant have indicated that the guys are

envious. I feel that they believe a black

should not hold this position. ...

This pressure has been experienced over

a period of time and because of this, I came

to you as Chief of Police, in August 1979

seeking another assignment, but you were not

able to reassign me. I feel that, in light

of these facts my job would be in constant

jeopardy as long as the lieutenant desires

to put someone else [i.e., a white officer,

Detective Doughty] where I am.

B a k e r the r e f o r e r e q u e s t e d t h a t he b e

transferred to another detective position outside the

burglary intelligence unit. He also requested that a copy

of the letter be placed in his personnel file for future

reference, and he delivered a copy of the letter to his

attorney and to each officer in the chain of command— Sgt.

Brodt, Lt. Whalin, Maj. Minter, Lt. Col. Roemele, and

Chief Helm.

Upon receiving the letter, Chief Helm directed Maj.

William Minter, Commander of the Criminal Investigation

Division and Chief of Detectives, to invesitgate the matter.

Tr. Vol. IV, at 171 (Helm). Maj. Minter's investigation,

which took place on January 16, 1980, consisted of inter

viewing Baker, Arnold, and seven or eight other persons.

Tr. Vol. Ill, at 40-43 (Minter). When Minter's deposition

was taken only two weeks later, however, he testified under

oath that he could not remember the nature of his conversa

tion with Baker (id. at 32); that he could not recall the

- 10 -

reason he interviewed Arnold, or the questions he asked

Arnold, or the substance of his conversation with Arnold

(id. at 37-39); that he could not remember the names of any

of the eight other persons he had interviewed (id_. at 41-42);

that he could not think of anything he had discussed with

any of these persons (id. at 45-46); that he knew he had

recommended that Baker and Arnold be transferred because

there was friction in their section, but that he could not

remember the name of even one person with whom they had

such friction (id. at 50-52); and that he could not remem

ber any specific problem with Baker's or Arnold's job per-Vformance (id. at 53).

Baker testified that Minter’s interview of him consisted

of questions about the contents of the letter, a statement

by Minter that he did not believe there was any discrimina

tion in the Department, and an inquiry as to why he had sent

a copy of the letter to a "civil rights attorney." Tr. Vol.

I, at 63-64. Arnold testified that Maj. Minter pressed him

to deny the allegations in Baker's letter, and to state that

Baker was not being singled out because he was black. Id.

at 235-36. Arnold refused to discredit Baker's letter;

instead, he told Minter that the letter was Baker's, not his,

3/ At the hearing on February 6, Minter testified that he

now remembered some of the facts which he had so completely

forgotten between the date of his investigation, January 16,

and the date of his deposition, January 31. The reason for

the remarkable improvement in his memory, he said, was that

before testifying at the hearing he had refreshed his recol

lection by reviewing some notes. Tr. Vol. Ill, at 32-33.

Minter did not explain why he had not reviewed these notes

before his deposition.

- 11-

that he could not state that Baker was not being subjected

to racial discrimination, and that "the incidents in the

letter spoke for themselves." Id. at 235-36; Vol. II, at

38. On the basis of Baker's letter and Minter's "investi

gation, " Chief Helm decided on January 17, 1980, to transfer

both Baker and Arnold, not to different positions within

the detective bureau as Baker had requested, but rather to

jobs as uniformed patrol officers. Helm Dep. at 29; Tr.

Vol. IV, at 191-92 (Helm). After being notified of the

transfer, Arnold informed Minter that he believed Baker's

allegations of racial discrimination were true. Tr. Vol.

II, at 38-40 (Arnold). He had not told this to Minter in

his earlier interview because he feared retaliation. Id;

Vol. Ill, at 7-9 (Arnold).

The transfer resulted in the loss of substantial extra

wages which had been available to Baker and Arnold as detec

tives, and in the loss of status and prestige within the

Department. It also deprived them of the use of unmarked

cars and the privilege of flexible working hours, and it

damaged their professional reputations and their ability to

perform as detectives by depriving them of the confidence of

contacts and informants they had cultivated through years

of work as detectives. Tr. Vol. I, at 70-79 (Baker), 240-

49 (Arnold). Therefore, their reassignment to uniformed

patrol duties was widely regarded by officers throughout

the Department not as a lateral transfer, but as a punitive

- 12-

demotion. Id; Vol. Ill, at 59-60 (Pike), 85 (White);

Vol. IV, at 196-98 (Moore); Vol. V, at 14 (Hall).

In the complaint which they filed in this action on

January 24, 1980, and in a motion and supporting affidavits

filed on the same date, the plaintiffs sought a temporary

restraining order and a preliminary injunction to restrain

the defendants from transferring, demoting, or otherwise

retaliating against plaintiffs Baker and Arnold pending a

final decision on the merits of their case. The district

court granted a temporary restraining order the following

day. Baker and Arnold were thereafter reinstated as detec

tives, but they were not granted the full benefits and privi

leges of their previous employment. Tr. Vol. I, at 79-81,

182-83 (Baker), 249-50 (Arnold).

After holding an evidentiary hearing, the district

court on March 4, 1980, dissolved the temporary restraining

order and denied the motion for a preliminary injunction.

In its memorandum opinion, the court held or assumed that

the plaintiffs had established a prima facie case of re

taliatory demotion for exercising their rights under Title

VII and 42 U.S.C. §. 1981. Opinion at 4. However, the court

went on to hold as follows (id. at 5):

4/ On January 28, 1980, Baker's attorney received his statu

tory Notice of Right To Sue from the U.S. Department of. Justice

(PX 2) . On January 22, Arnold filed an EEOC charge alleging

unlawful retaliation (PX 13). He requested a Notice of Right

To Sue which, at the time of the hearing, had not yet been

issued. Tr. Vol. I, at 253 (Arnold).

-13-

The weight of the evidence ... shows that

the decision to transfer Baker and Arnold was

primarily due to the following factors:

1. Baker's specific contention that he could

not work under Lt. Whalin whom he accused of

playing favorites and of being racially biased;

2. The conclusions of the Commanding Officer

that it was not in the best welfare of the

Police Department to have Baker and Arnold

continue on the detective force where they

have shown inability to follow direct commands

and more importantly, had expressed their lack

of trust in the impartiality of the chain of

command.

The court ... concluded that defendants

have shown a legitimate nondiscriminatory

reason for the transfer of plaintiffs. ... [T]he

alleged reason for their transfer was a legitimate

one.

After reaching this conclusion of law, the court recited

four findings of fact which were said to prove that the

defendants' asserted reasons for transferring Baker and

Arnold were not a pretext for unlawful discrimination or

retaliation. Opinion at 5-6. Accordingly, the court

dissolved the temporary restraining order and denied plain

tiffs' motion for a preliminary injunction. Order of March

4, 1980. Baker and Arnold were then demoted once again to

positions as uniformed patrol officers. They subsequently

filed a timely notice of appeal.

-14-

Summary of Argument

In holding that an employer may lawfully retaliate

against employees for their opposition to racially dis

criminatory employment practices, the district court

misconstrued Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and 42 U.S.C. § 1981. The court further erred as a matter

of law in holding that an employee may be punished for

supporting a co-worker's claims of discriminatory treat

ment. The court also based its decision on clearly

erroneous findings of fact, and it abused its discretion

in refusing to grant a preliminary injunction.

-15-

Argument

I. THE DISTRICT COURT MISCONSTRUED TITLE VII OF THE

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964 AND 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

A. Standards of Proof

As the district court acknowledged (Opinion at 4), the

Supreme Court1s decision in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green.

411 U.S. 792 (1973), controls the order and allocation of proof

in cases of alleged retaliation for activities protected by Title

VII and § 1981. Under McDonnell Douglas, the plaintiff must first

establish a prima facie case of retaliation? the burden then shifts

to the employer to demonstrate a legitimate nondiscriminatory

reason for the apparent acts of reprisal; and finally, the burden

returns to the plaintiff, who has an opportunity to show that the

employer's asserted reasons are a pretext for unlawful retaliation.

See, e.g., Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 622 F.2d 43, 46 (2d cir.

1980); Womack v. Munson, 619 F.2d 1292, 1296 (8th Cir. 1980);

Aguirre v. Chula Vista Sanitary Service, Inc., 542 F.2d 779, 781

(9th Cir. 1976). The plaintiff's prima facie case may be estab

lished by evidence showing: (1) statutorily p r o t e c t e d

a c t i v i t y ; (2) adverse employment action; and (3) a causal con

nection between the two. Womack, supra, 619 F.2d at 1296; Grant,

supra, 622 F.2d at 46; Kirkland v. Buffalo Board of Education, 487

-16-

F.Supp. 760, 772-73 (W.D.N.Y. 1979), aff'd, 622 F.2d 1066 (2d Cir.

1980). The requisite causal connection can be established by

circumstantial evidence showing that protected activity was fol

lowed by adverse treatment. Grant, supra, 622 F.2d at 46-47;

Aguirre, supra, 542 F.2d at 781.

The evidence in the case at bar demonstrates that both

plaintiff Baker and plaintiff Arnold engaged in protected activity.

See Sections IB and IC, infra. Baker filed a formal EEOC charge

alleging discrimination in promotions. He also wrote a letter to

his supervisors, informing them of treatment which he reasonably

believed to be discriminatory and seeking their assistance in im

proving the situation through informal means. Arnold refused to

deny or discredit the statements in Baker's letter, although

pressed by his commanding officer to do so. This activity was

followed by prompt adverse action: both Baker and Arnold were re

moved from the detective bureau and demoted to positions as uni

formed patrol officers. There is overwhelming evidence, circum

stantial and direct, that the protected activity was the primary

cause of the demotion. See pp. 6-12, supra. Indeed, Major

Minter, who conducted the internal "investigation11 into Baker's

allegations, admitted that one of the reasons for the action taken

against Baker and Arnold was that "[t]hey had accused the sergeant

and lieutenant of being prejudiced." Tr. Vol. Ill, at 50. Chief

-17-

Helm also admitted that he transferred Baker to uniformed patrol

duties in part because of Baker's statement to the Chief that he

believed Minter was racially biased- Tr. Vol. IV, at 190-91.

Thus, the district court was clearly correct insofar as it

held that Baker and Arnold had established a prima facie case of

unlawful retaliation. Opinion at 4. However, as set forth below,

the court erred as a matter of law in concluding that the defend

ants had demonstrated legitimate nondiscriminatory reasons for de

moting the plaintiffs, and it relied on clearly erroneous findings

of fact in holding that the defendants1 asserted reasons were not a

pretext for unlawful retaliation.

B. The District Court Erred as a Matter of Law in

Holding that an Employer May Lawfully Retaliate

Against Employees Because They Have Accused their

Supervisors of Racial Discrimination.

Section 704 (a) of Title VII prohibits discrimination against

any person "because he has opposed any practice, made an unlawful

employment practice by this title, or because he has made a charge,

testified, assisted, or participated in any manner in an investiga

tion, proceeding, or hearing under this title." 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-

5/3(a). The courts have recognized that the two disjunctive clauses

5/ The full texts of Section 704(a) of Title VII and 42 U.S.C. § 1981

are reproduced in an addendum to this brief.

-18-

of this section protect two different kinds of activities. The

"participation" clause protects employees from retaliation for

filing formal charges of discrimination or lawsuits under Title VII,

and it protects other persons who testify, assist, or otherwise

participate in such formal proceedings. The purpose of this clause

is "to protect the employee who utilizes the tools provided by Con

gress to protect his rights." Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe

Co., 411 F.2d 998, 1005 (5th Cir. 1969). Accordingly, the merits

of the charges made in formal administrative or judicial proceed

ings are irrelevant to the protection granted by the participation

clause; "employer retaliation even against those whose charges are

unwarranted cannot be sanctioned." Womack v. Munson, supra, 619

F.2d at 1298. See also, Sias v. City Demonstration Agency, 588 F.2d

692, 695 (9th Cir. 1978).

The "opposition" clause of § 704 (a), on the other hand,

reaches beyond the protection of direct participation in formal

proceedings. Novotny v. Great American Federal Savings & Loan

Ass1n , 584 F.2d 1235, 1260 (3rd Cir. 1978) (en banc), vacated on

on other grounds, 442 U.S. 366 (1979). This clause "is designed

to encourage employees to call to their employers' attention dis

criminatory practices of which the employer may be unaware or which

might result in protracted litigation to determine their legality

if they are not voluntarily changed." Berg v. La Crosse Cooler Co.,

-19-

612 F-2d 1041, 1045 (7th Cir. 1980). See also, McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green, supra, 411 U.S. at 796 (§ 704(a) "forbids discri

mination against applicants or employees for attempting to protest

or correct allegedly discriminatory conditions of employment").

The protection afforded by the opposition clause does not

depend upon a determination that the practices complained of are

in fact unlawful. The imposition of such a requirement would

"undermine Title VII1s central purpose, the elimination of employ

ment discrimination by informal means," and it would "destroy one

of the chief means of achieving that purpose, the frank and nondis-

ruptive exchange of ideas between employers and employees. . . . "

Berg v. La Crosse Cooler Co., supra, 612 F.2d at 1045. The courts

have refused to interpret the opposition clause in a manner which

"would not only chill the legitimate assertion of employee rights

under Title VII but would tend to force employees to file formal

charges rather than seek conciliation or informal adjustment of

grievances." Sias v. City Demonstration Agency, supra, 588 F.2d at

695. Therefore, it is now well settled that this clause of § 704(a)

protects employees from retaliation for peaceful, nondisruptive

opposition to practices which they reasonably believe to be dis

criminatory. Berg, supra, 612 F.2d at 1045-46? Sias, supra, 588

F.2d at 695-96? Novotny, supra, 584 F.2d at 1260-62? Hearn v. R.R.

Donnelley & Sons Co., 460 F.Supp. 546, 548 (N.D. 111. 1978)? Hearth

- 20 -

v. Metropolitan Transit Commission, 436 F.Supp. 685, 688-89 (D.

Minn. 1977) .

It is also well settled that 42 U.S.G. § 1981, like § 704(a)

of Title VII, protects employees who seek to improve the conditions

of their work place through informal methods as well as through

formal legal proceedings. See Hearn v. R.R. Donnelley & Sons Co.,

supra, 460 F.Supp. at 548. The substantive protection from retali

ation afforded by § 1981 is essentially the same as that afforded

by Title VII. See, e.g., Winston v. Lear-Siegler, Inc., 558 F.2d

1266 (6th Cir. 1977); DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak Co., 511 F.2d 306,

modified on other grounds, 520 F.2d 409 (2d Cir. 1975).

In the case at bar,-the district court found that Baker and

Arnold were demoted primarily because Baker had accused his lieuten

ant "of playing favorites and of being racially biased," and because

they had shown an "inability to follow direct commands" and "more

6/ Plaintiffs demonstrate in Section II, infra, that this finding

is not supported by the record and should therefore be set aside

as clearly erroneous. Even if this finding were accepted at face

value, however, it would not legitimize the demotion of Detectives

Baker and Arnold. It is clear from the court's opinion that the

trial judge regarded the plaintiffs' alleged inability to follow

orders as, at best, a secondary reason for the action taken against

them. The primary reason, the court found, was that they had made

complaints to their supervisors of favoritism, partiality, and

racial discrimination. Opinion at 5. The evidence shows that, in

the absence of these complaints, the plaintiffs would not have been

demoted. Thus, their alleged inability to follow orders, even if

proved, could not be considered as an independent justification for

their demotion. See Womack v. Munson, supra, 619 F.2d at 1297 and

n. 7.

- 21-

importantly, had expressed their lack of trust in the impartiality

of the chain of command." Opinion at 5. The complaints of favor

itism, partiality, and racial discrimination were made in Baker's

letter of January 9, 1980, to Chief Helm (PX 7), and in Baker’s

and Arnold's subsequent discussions of the letter with their com

manding officers. Tr. Vol. I, at 63-64 (Baker), 235-36 (Arnold);

Vol.II, at 38-40 (Arnold); Vol. Ill, at 7-9 (Arnold). The district

court concluded that, by calling these problems to the attention of

their supervisors and by seeking to resolve these problems through

informal means, Baker and Arnold provided the defendants with a

"legitimate nondiscriminatory reason" to demote them. Opinion at2/5. This conclusion is at odds with the language and purpose of

the "opposition" clause of § 704(a) of Title VII, and it is contrary

to the decisions interpreting both that provision and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981.

The congressional purpose underlying Title VII is to elimi

nate unlawful discrimination in employment. "Cooperation and volun-

7/ Since this conclusion depends upon the application of legal

standards and not upon the resolution of contested factual ques

tions, the clearly erroneous rule does not apply. Therefore, this

Court must make an independent determination of whether the defend

ants demonstrated a legitimate nondiscriminatory reason for demoting

the plaintiffs. See Senter v. General Motors Corp., 532 F.2d 511,

526 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 870 (1976); Swint v. Pullman

Standard, 624 F . 2d 525, 533 n.6 (5th Cir. 1980).

- 22-

tary compliance were selected as the preferred means for achieving

this goal." Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974).

Section 704(a) serves this congressional objective by protecting

employees from retaliation because they have "opposed any practice,

made an unlawful employment practice by this title ...." 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-3(a). The district court's decision, on the other hand

ignores the language and frustrates the purpose of Title VII by

authorizing employers to punish employees who advise their super

visors of discriminatory treatment and who seek to eliminate such

discrimination through informal means. The district court erred

in holding that Title VII and § 1981 permit the punishment of em

ployees for engaging in conduct which Congress plainly intended to

protect and encourage. See pp. 19-21, supra.

C. The District Court Erred as a Matter of Law in

Holding that an.Employer May Lawfully Retaliate

Against an Employee Because he has Supported a

Co-worker's Claim of Discriminatory Treatment.

Although the district court treated the two plaintiffs'

claims as if they were identical, the conduct for which Arnold was

punished differed in significant respects from that of Baker. Un

like his black partner, Arnold had not filed any formal charges

of discrimination and had not written any letter of complaint

to his commanding officers. When he was interviewed by Major

Minter on January 16, 1980, he refused to confirm or deny Baker's

allegations of racial discrimination (Tr. Vol. I, at 235-36); he

-23-

merely stated that "the incidents in the letter spoke for them

selves." Tr. Vol. II, at 38. Only after he had already been

demoted and had nothing more to fear did he tell Minter that he

believed Baker's allegations were true. Id. at 38-40; Vol. Ill,

at 7-9.

Thus, contrary to the district court's finding, Arnold was

not demoted because he personally complained of favoritism, partial

ity, or racial bias, but rather because he refused to discredit the

complaints made by Baker. As this court held in Winston v. Lear-

Siegler, Inc.., supra, 558 F.2d at 1268-70, it is a violation of

42 U.S.C. § 1981 for an employer to punish a white employee for

supporting a black co-worker's claim of discriminatory treatment.

This Court's decision in Winston has been followed in the district

2/courts, and it is consistent with other appellate decisions under

both § 1981 and § 704(a) of Title VII. See DeMatteis v. Eastman

Kodak Co., supra, 511 F.2d at 312 (employer's punishment of a white

employee for selling his home to a black co-worker violates § 1981)

Novotny v. Great American Federal Savings & Loan Ass'n, supra, 584

F.2d at 1262 (discharge of a male employee for reasonable opposi

tion to employer's alleged discrimination against a female employee

8/ See Ragheb v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Michigan. 467 F.Supp..

94, 95 (E.D. Mich. 1979); Liotta v. National Force Co.. 473 F.Supp.

1139, 1145-46 (W.D. Pa. 1979); National Organization for Women v .

Sperry Rand Corp., 457 F.Supp. 1338, 1346 (D. Conn. 1978); Garcia

v. Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's Medical Center, 80 F.R.D. 254, 265-

66 (N.D. 111. 1978).

-24-

violates § 704 (a)); Eichman v. Indiana State University Board of

Trustees, 597 F.2d 1104, 1107 (7th Cir. 1979) (failure to reappoint

a male faculty member because he assisted a female faculty member

in pursuing discrimination claims violates § 704(a)); Federoff v .

Walden, 17 FEP Cases 91, 96-97 (S.D. Ohio 1978) (discharge of

employee for supporting co-worker's charge violates § 704(a)).

These decisions recognize the principle that a white employee

at times may be the only effective adversary of unlawful discrimina

tion against minorities, and that to permit the punishment of such

an employee will result in the perpetuation of discrimination.

See Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 237 (1969).

The court below ignored this principle, and its conclusion that

the defendants demonstrated a legitimate nondiscriminatory reason

for demoting Arnold is therefore in error.

-25-

II. THE DISTRICT COURT BASED ITS DECISION ON

CLEARLY ERRONEOUS FINDINGS OF FACT.

After reaching the erroneous legal conclusion that the

defendants1 asserted reasons for demoting Baker and Arnold

were legitimate and nondiscriminatory, the district court

recited four numbered findings of fact which, it said, proved

that these reasons were not a pretext for unlawful discrimina

tion or retaliation. Opinion at 5-6. As set forth below, each

of these findings is clearly erroneous and should therefore be

set aside.

1. The district court found that "[t]he oral reprimand

which was administered to Baker for failing to be present at

a detail [on New Year's Eve], was not administered to Arnold.

That reprimand happened to be administered to Baker alone,

since Arnold was not present and the reprimand was meant to

be conveyed to Anold [sic], since he and Baker acted as a

team." Opinion at 5.

The record shows that Detectives Baker and Arnold were

both present when Sgt. Brodt called Baker into his office

and reprimanded him for failing to appear at a detail on

New Year's Eve. Tr. Vol. I, at 232 (Arnold). On New Year's

Eve, both Baker and Arnold had been on vacation; their vaca

tion requests had been approved by Sgt. Brodt himself. Id;

Tr. Vol. I, at 41-43 (Baker). But when Arnold asked Brodt if

he should come into the office with Baker, Brodt replied that

he did not want Arnold to be there, and he did not reprimand

-26-

Arnold. Tr. Vol. I, at 232 (Arnold); see also, Tr. Vol. IV,

at 135-36 (Brodt). The district court's finding to the con

trary is clearly erroneous.

2. The district court found that "[i]t appeared with

out question that Lt. Whalin did not allow any officers to

hang any degrees or any other matters in the area under his

command." Opinion at 5. But Sgt. Brodt, testifying for the

defendants, admitted that when he came into Whalin's unit in

October or November of 1979, there were things hanging on the

walls in the squad rooms. Tr. Vol. IV, at 146-47. This

occurred long after July of 1979, when Lt. Whalin had told

Detective Baker that he was no longer permitted to hang his

Doctor of Divinity degree on the wall. Tr. Vol. I, at 30-33

(Baker).

3. The court found as follows: "Baker alleged that he

had been called a 'nigger' by fellow officers from the Police

Force, but stated that many of the occasions were in a joking

mood. He and Arnold were able to identify only one person,

Detective Wright, whom they claimed used the word in a serious

and biased manner and they showed no relationship between

Detective Wright and the chain of command in which they were

involved." Opinion at 6.

Baker did in fact testify that Detective Jack Wright

called him a "nigger" to his face after he filed his EEOC

charge in April 1979. Tr. Vol. I, at 20-21. Baker never

-27-

testified that he was called "nigger" in a joking mood. See

Tr. Vol. I, at 22-23.

Arnold testified that he frequently heard other officers

call Baker names and make derogatory comments about Baker's

race. Tr. Vol. I, at 206-208. He often heard statements

about "niggers" and other racial slurs made in the presence

of Chief Helm, Lt. Whalin, and other commanding officers, but

no one was ever reprimanded for this conduct. Tr. Vol. II, at

69-70; Vol. Ill, at 1. Arnold believed that some of these

statements were made "in a joking manner" but others were

meant to be taken seriously. Tr. Vol. I, at 207; Vol. II, at 70.

In September 1977, Arnold's immediate supervisor, Sgt. Flowers,

asked him if he would have any objections to riding with a

"nigger." When Arnold replied that he had no objections,

Flowers said, "then Charlie is your nigger. You've got him

..." Tr. Vol. Ill, at 1-2.

It was not Detective Baker, as found by the court, but

rather Detective Ronald Pike, the white president of the

Fraternal Order of Police, who testified that in his opinion

racial epithets were used in the department in a "joking

manner." Tr. Vol. Ill, 61. He also testified that he himself

had made racial slurs, that he had heard racial slurs made by

commanding officers and in the presence of commanding officers,

and that neither he nor any other officer had been reprimanded

for this conduct. Tr. Vol. Ill, at 61, 69-70.

-28-

4. The court found that "Baker and Arnold made refer

ences to some members of the Police Force being members of

Ku Klux Klan but were unable to identify any particular officer

as a member." Opinion at 6. The record shows, however, that

Detective Baker and Detective Bruce White testified that there

were members of the Klan in the Police Department. Tr. Vol.

I, at 63 ; Vol. Ill, at 89. Baker was never asked to identify

any of these officers. White testified that he did not know

their names but he knew some faces. Tr. Vol. Ill, at 100.

In addition to the four clearly erroneous findings dis

cussed above, the district court also clearly erred in making

the following findings of fact:

5. The court found that "Baker specifically addressed

a letter to Col. Helm in July, 1979, praising him for the

objective and racially fair manner in which he had run the

Police Force." Opinion at 6. In fact, the subject of the

letter (DX 2) is limited to the discharge of one officer:

"The action taken by yourself as Chief of this department

in reference to Officer M. Jones has received my full support

and the support of the many other Black Officers." Id. at

1. The letter does not praise Chief Helm for being "objec

tive and racially fair" in his overall operation of the

police force (Opinion at 6), but refers only to the Chief's

handling of the Jones incident. Tr. Vol. I, at 96, 98-99

(Baker).

-29-

6. The district court found as follows: "During

December, 1979, plaintiffs were engaged in detective work in

an area where Detective Michael Doughty was the beat detective.

The weight of the evidence is that they had been instructed by

Sgt. Brodt, their superior officer, to keep in touch with

Doughty as to all events which transpired with regard to the

break in which they were investigating in his area. They

failed to do this and were called on the carpet by Lt. Whalin

and Sgt. Brodt on January 6, 1980. Lt. Whalin and Sgt. Brodt

found fault with Detectives Baker and Arnold for the manner

in which they had handled the matter and for their failure to

communicate with Doughty as per instructions." Opinion at 2.

The record does not show that Baker and Arnold were told

"to keep in touch with Doughty as to all events which transpired

with regard to the break in ...." Opinion at 2. Rather, the

record shows that Sgt. Brodt told Detectives Baker and Arnold

to notify the detective assigned to a particular beat before

making any arrests on that beat, and to include that detective

in any such arrests. Tr. Vol. I, at 43-44 (Baker), at 226

(Arnold).

When Baker and Arnold began investigating the Norfolk

Apartment burglaries in December 1979, they believed that

the suspects had committed crimes on Detective Doughty's

beat, and accordingly they gave Doughty leads, suggestions,

and photographs to assist him in investigating the burglaries.

Tr. Vol. IV, at 136-37 (Brodt); Vol. I, at 222-24 (Arnold).

-30-

When Baker and Arnold learned through their investigation that

the suspects had committed crimes on Detective Bruce White's

beat and not on Detective Doughty's beat, they then assisted

Detective White, in accordance with their instructions. Tr. Vol.

I, at 43-48 (Baker), at 226-28 (Arnold). See pp. 8-9, supra.

The court below clearly erred in finding that Baker and Arnold

failed "to communicate with Doughty as per insturctions."

Opinion at 2.

7. The district court found that "plaintiff Baker,

despite the fact that no action had been taken against him

[following the Doughty incident], proceeded to write a five-

page letter to Col. Helm ...." Opinion at 2-3.

The record shows that action had been taken against

Detective Baker before he wrote his letter of January 9, 1980,

to Chief Helm. On January 2, Sgt. Brodt reprimanded Baker

for failing to appear at a detail on New Year's Eve, when he

had been on a vacation approved by Sgt. Brodt himself. Tr.

Vol. IV, at 135-36 (Brodt); Vol. I, at 41-43 (Baker); Vol. I,

at 231-34 (Arnold). In addition, on January 7 both Baker and

Arnold were orally reprimanded by Lt. Whalin and Sgt. Brodt

for allegedly failing to follow instructions regarding

Detective Doughty. Tr. Vol. IV, at 137-40 (Brodt); Vol. I,

at 43-45 (Baker); Vol. I, at 226-28 (Arnold).

8. The district court found that " [a]11 witnesses who

testified attested to their [i.e., Baker's and Arnold's] out

standing ability in the field of detective work, but the

-31-

weight of the evidence also was to the effect that they had

some problems in cooperating with detectives on the beat ...."

Opinion at 1-2. However, all of the detectives who testified,

including one detective called by the defendants, stated that

Baker and Arnold had been helpful and cooperative at all

times.

Detective Bruce White testified that he had always enjoyed

a good working relationship with Detectives Baker and Arnold,

and that Baker had assisted him in developing informants on

his beat. White further testified that Baker and Arnold were

regarded highly by the rank-and-file in the Police Department.

Tr. Vol. Ill, at 81-83. Contrary to the testimony of Major

Minter regarding Detective White (Tr. Vol. Ill, at 51), White

himself denied that he had experienced any friction with Baker

and Arnold. Tr. Vol. Ill, at 83-84.

Detective Ronald Pike, the president of the local lodge

of the Fraternal Order of Police, testified that he had worked

with both Detective Baker and Detective Arnond, and that he

had found them to be cooperative. He had not heard any

criticism of them from other detectives or commanding officers

in the Department. He testified that both Baker and Arnold had

always performed in a professional manner wherever they were

assigned. Tr. Vol. Ill, at 60-61.

Detective Jerry Hall also testified that Baker and Arnold

had worked well with him in the past. Tr. Vol. V, at 12, 14.

He stated that Arnold had readily accompanied him on a lengthy

-32-

surveillance detail in October 1979, even though Arnold was

suffering from an injury sustained the prior weekend and was

scheduled to be off duty at that time. Id. at 17. Detective

Hall had "never seen anything but cooperation from Detective

Arnold or Detective Baker either one," and he had "never asked

them to do anything they haven 11 done . . . . " Id.. at 12 .

Detective Garland Conway testified that his experience

with Baker and Arnold had been positive and that he had en

countered no difficulties in working with them. Tr. Vol. V,

at 5, 8.

Detective Joe Carter, a defense witness, testified that

on one occasion he had made a complaint about the plaintiffs 1

participation in an investigation. But on cross-examination

he admitted that Baker and Arnold were helpful, and that the

problem in that one case might have been due to his own lack

of experience. Furthermore, he testified that Baker's and

Arnold's assistance helped him solve the case. Tr. Vol. IV,

at 163-66.

Michael Doughty, a detective with whom Baker and Arnold

were said to have encountered difficulties, was not called as

a witness although defendants' counsel made repeated references

to him and to an alleged lack of cooperation with him. Thus,

the district court clearly erred in finding that Baker and

Arnold had problems in cooperating with detectives on the beat.

-33-

Since a review of the evidence leaves "the definite and

firm conviction that a mistake has been committed," the fore

going findings of fact are clearly erroneous and should be set

aside. United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S.

364, 395 (1948); Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 624 F.2d 525, 533

n. 6 (5th Cir. 1980); Rule 52(a), Fed. R. Civ. P.

-34-

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ABUSED ITS DISCRETION IN

DENYING THE MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNC

TION.

Under Rule 65, Fed. R. Civ. P., as interpreted by

this Court in Mason County Medical Ass'n v. Knebel, 563

F.2d 256, 261 (6th Cir. 1977), a preliminary injunction

should be granted where: (1)the plaintiffs have shown a sub

stantial probability of success on the merits; (2) the

plaintiffs have shown irreparable injury; (3) the injunc

tion would not cause substantial harm to others; and (4)

the injunction would serve the public interest. See also,

Federoff v. Walden, 17 FEP Cases 91, 96-97 (S.D. Ohio 1978).

In retaliation cases under Title VII and § 1981, some courts

have adopted a less demanding standard, holding that a pre

liminary injunction should issue

"... upon a clear showing of either (1) probable

success on the merits and possible irreparable

injury, or (2) sufficiently serious questions

going to the merits to make them a fair ground

for litigation and a balance of hardships tipping

decidedly toward the party requesting the pre

liminary relief."

Aguirre v. Chula Vista Sanitary Service, Inc., supra, 542

F.2d at 781 (emphasis in original), quoting Gresham v.

Chambers, 501 F.2d 687, 691 (2d Cir. 1974). Under either

the Mason standard or the Aguirre standard, the district

court here abused its discretion in refusing to grant plain

tiffs the protection of a preliminary injunction.

-35-

The court below denied the motion for a preliminary-

injunction on the ground that plaintiffs failed to show a

substantial chance of success on the merits. Opinion at

7. As demonstrated above, this conclusion was based on

the district court's misconstruction of Title VII and § 1981

(see Section I, supra) and on a series of clearly erroneous

findings of fact (see Section II, supra). The foregoing

sections of this brief show that, on a correct view of the

law and the facts, the plaintiffs not only raised serious

questions requiring litigation (Aguirre, supra) but they

also established a substantial probability of success on

the merits of their retaliation claims (Mason, supra).

Having erroneously concluded that the plaintiffs had

little chance of success on the merits, the district court

failed to determine whether the plaintiffs had established

irreparable injury, whether an injunction would cause any

substantial harm to others, or whether an injunction would

serve the public interest. The record shows that, on all

of these counts, the plaintiffs satisfied, the requirements

for obtaining a preliminary injunction.

The demotion of plaintiffs Baker and Arnold to uniformed

patrol positions not only deprived them of extra wages they

would have earned as detectives, but also caused them to

lose status and! prestige within the Police Department. See

Opinion at 3. The demotion also deprived them of the use of

unmarked cars, the privilege of flexible working hours, and

other non-monetary benefits and privileges, and it damaged

b -36-

their professional reputations and their ability to perform

as detectives in the future by depriving them of the confi

dence of contacts and informants they had developed through

years of work as detectives. See pp. 12-13, supra. It

is now impossible to fully remedy these injuries.

Moreover, "[i]ndependently of the threat to [the plain

tiffs'] employment future, there is irreparable damage done

to the administrative process if other employees feel that

their positions are in jeopardy if they cooperate with

agency investigations." Federoff v. Walden, supra, 17 FEP

Cases at 96-97. There is direct evidence of such irreparable

damage in the instant case. Bruce White, another black de

tective, testified that he had considered joining Baker in

filing a charge of discrimination, but he decided against

it because he feared that such action would be met by re

taliation. Tr. Vol. Ill, at 86-87. After the court granted

a temporary restraining order to Baker and Arnold, Detective

White agreed to testify on their behalf. When asked at the

hearing why he previously had been afraid to file a charge

of discrimination but now was willing to testify in open

court, he answered as follows (id. at 89):

Well, maybe the Court could probably grant

me some sort of protection, not that I am going

to be physically harmed or something like that;

but as far as shift to uniform or late shift or

radio room or something like that, that worried

me. I think it worried — it's worried a lot

of people that have testified. It's probably

... the biggest worry of anybody that will come in,

the fact that you might get transferred or some

thing like that.

-37-

Detective White and other officers were willing to testify

for the plaintiffs because they had some reason to believe

the court would protect them from retaliation. The removal

of that protection irreparably damaged the integrity and

effectiveness of the legal process.

There is ample evidence in the record that a preliminary

injunction protecting Baker and Arnold from retaliatory de

motion would not have caused any substantial harm to others.

As the district court acknowledged, they had "outstanding

ability in the field of detective work ... . " Opinion at

1-2. There is no substantial evidence that they were un

cooperative toward other detectives; the great weight of

the evidence is to the contrary. See Section II, supra.

Their personnel files contained many commendations and no

serious reprimands. PX 11, 18. Their performance in the

burglary intelligence unit was rated highly by the independent

Criminal Justice Commission- Tr. vol. IV, at 206-207 (Bewley).

Thus, a preliminary injunction requiring that Baker and Arnold

be permitted to remain as detectives pending the outcome of

the lawsuit would not have caused any harm to others but, on

the contrary, would have preserved their considerable skills

as detectives and would have assured the continued use of

those skills for the benefit of the citizens of Jefferson

County.

Finally, "the public interest would be served by an

injunctive order which protects the process designed by

Congress to attack employment discrimination in this country."

-38-

Federoff v. Walden, supra, 17 FEP Cases at 97. The district

court's decision in this case has not served the public interest;

rather, it has sanctioned retaliation against employees who

oppose discriminatory practices and who seek to correct those

practices, either through congressionally authorized informal

means or through the formal administrative and judicial pro

cess. Few employees will be so courageous — or so foolhardy

— as to ignore this warning from the district court. Many

employees who believe they have been victimized by unlawful

discrimination, and others who might wish to support their

claims, now will remain silent rather than risk their jobs

to assert their rights. The preliminary injunction requested

by plaintiffs, on the other hand, would have served the public

interest by protecting the process established by Congress

for the peaceful and fair resolution of employment discrimina

tion claims.

Since the plaintiffs satisfied all the applicable require

ments, the district court abused its discretion in denying

their motion for a preliminary injunction. On remand, the

district court therefore should be directed to enter an appro

priate preliminary injunction.. See Aguirre v. Chula Vista

Sanitary Service, Inc., supra, 542 F.2d at 781.

-39-

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the district court's order

dissolving the temporary restraining order and denying the

motion for a preliminary injunction should be reversed, and

the case should be remanded for the entry of appropriate

injunctive relief pending a final decision on the merits.

Respectfully submitted.

JUANITA LOGAN CHRISTIAN 7

Suite 490

730 West Main Street

Louisville, Kentucky 40202

(502) 587-8.091

JACK GREENBERG

PATRICK 0. PATTERSON

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

-40-

Addendum

§ 704(a), Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-3(a):

It shall be an unlawful employment

practice for an employer to discriminate

against any of his employees or applicants

for employment, for an employment agency,

or joint labor-management committee con

trolling apprenticeship or other training

or retraining, including on-the-job train

ing programs, to discriminate against any

individual, or for a labor organization to

discriminate against any member thereof or

applicant for membership, because he has

opposed any practice, made an unlawful

employment practice by this title, or be

cause he has made a charge, testified,

assisted, or participated in any manner

in an investigation, proceeding, or hearing

under this title.

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981:

All persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States shall have the same

right in every State and Territory to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full

and equal benefit of all laws and proceed

ings for the security of persons and pro

perty as is enjoyed by white citizens, and

shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions

of every kind, and to no other.

-41-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that two copies of the foregoing brief

for plaintiffs-appellants were served on this date by

United States mail, first class postage prepaid, addressed

to William L. Hoge, III, Assistant County Attorney, 1112

Kentucky Home Life Building, Louisville, Kentucky 40202.

Dated: November 14, 1980

Patrick 0. Patterson

1