Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief of Appellees

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief of Appellees, 1966. 2ea7402d-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/da8a63a7-6fa8-4e53-9484-db38ae1f7f9d/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-brief-of-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

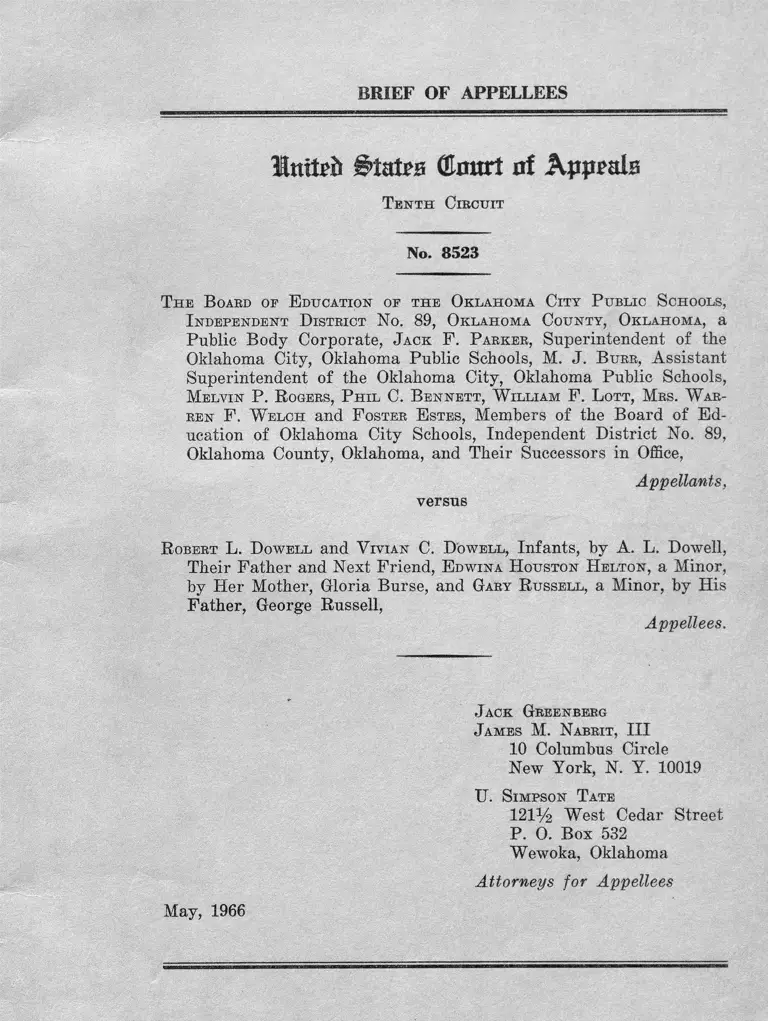

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

Intteb States (Enurt nf Appeals

Tenth Circuit

No. 8523

T he B oard op E ducation of the Oklahoma City Public Schools,

I ndependent District No. 89, Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, a

Public Body Corporate, Jack F. Parker, Superintendent of the

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Public Schools, M. J. B urr, Assistant

Superintendent of the Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Public Schools,

Melvin P. R ogers, Phil C. Bennett, W illiam F. Lott, Mrs. W ar

ren F. W elch and F oster E stes, Members of the Board of Ed

ucation of Oklahoma City Schools, Independent District No. 89,

Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, and Their Successors in Office,

versus

Appellants,

R obert L. Dowell and V ivian C. Dowell, Infants, by A. L. Dowell,

Their Father and Next Friend, E dwina H ouston H elton, a Minor,

by Her Mother, Gloria Burse, and Gary R ussell, a Minor, by His

Father, George Russell,

Appellees.

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

U. Simpson Tate

121% West Cedar Street

P. 0 . Box 532

Wewoka, Oklahoma

Attorneys for Appellees

May, 1966

I N D E X

Statement of the Case -...... -................ -...... -...... -....... —- 1

I. Legal Segregation in Oklahoma City Public

Schools and Practices Which Continued Segre

gation, from 1907 to Date of District Court’s

Order .................................... ■............................. -...... 2

II. The District Court’s Order Authorizing An Ex

pert Study to Formulate an Effective Plan for

Desegregation of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools ............................................. -.......... .............. 9

III. The Expert Panel’s Analysis of the Deficiencies

of the School Board’s Plan of Desegregation,

and Their Proposals for An Adequate Plan ....... 11

A. The Adequacy of the Overall Plan ........... .... 11

B. Transfer Policies .............................................. 13

C. Zoning and Attendance Areas ............. ........ 16

D. Faculty Desegregation .......................... - ......... 19

IV. The District Court’s Order Requiring an Effec

tive Plan of Desegregation of the Oklahoma City

Public Schools, and Establishing Certain Stan

dards for Such a Plan .............................................. 22

Argument

I. Substantial Evidence Was Introduced of the Ex

istence and Continuation of Segregation in the

Oklahoma City School System .......................... . 25

PAGE

11

II. Where There Is Legal Segregation in a Public

School System, the District Court Must Order

An Effective Plan of Desegregation ............- 28

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) .... 30

Bradley v. School Board, City of Richmond,

Va., 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ..... ......................... 32

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington,

Va., 324 F.2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) ...........30, 32

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) ...................... ....... ................. ............. -28,29

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............... 29

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir.

1960) ...... ......................... ................... ...... -...... 30

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knox

ville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) ................. ......... 30, 31

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Ed

ward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ........... 30

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of

Palm Beach, Fla., 258 F.2d 730 (5th Cir.

1958) .................................................................. 32

Houston Independent School District v. Ross,

282 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1960) ...................... 30

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir.

1965) ...................... 32,33

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City

of Memphis, 333 F.2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ... 31, 32

Price v. Denison Independent School District,

348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965) ........... 31

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ...........29, 31

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 30

PAGE

I l l

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir.

19 ) ; 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 19 ) .......30, 31

III. The District Court Properly Obtained Expert

Testimony as a Basis for Formulating an Effec

tive Plan of Desegregation, and Such Testimony

Provided a Reasonable Basis for the Court’s

Order ................................... -................................-..... 33

Ackelson v. Brown, 264 F.2d 543 (8th Cir.

1959) .................................................... ............. 33

Duff v. Page, 249 F.2d 137 (9th Cir. 1958) .... 33

Padgett v. Buxton-Smith Mercantile Co., 262

F.2d 39 (10th Cir. 1959) .......... .................... 33

Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington

County, Va., 357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) .... 35

IV. Power and Duty of Court of Equity to Remedy a

Wrong Is Commensurate with the Scope of the

Wrong .......................................................................... 37

Bowles v. Skagg, 151 F.2d 817 (6th Cir.

1946) ... .................. 37

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 II.S. 294

(1955) .............. 39

Dabney v. Chase National Bank of the City of

New York, 201 F.2d 635 (2nd Cir. 1953),

cert, dism’d, 346 IT.S. 863 ............................ 37

Leo Feist, Inc. v. Young, 138 F.2d 972 (7th

Cir. 1944)

PAGE

37

IV

PAGE

Overfield v. Penrod Corp., 42 F. Supp. 586

(D.C. Pa. 1942), affd 146 F.2d 889 (3rd

Cir. 1942) .......................................................... 37

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334

U.S. 110, petition denied, 334 U.S. 809 ....... 38

Schneider v. Schneider, 141 F.2d 542 (D.C.

Cir. 1944) .......................................................... 37

United States v. Aluminum Company of

America, 91 F. Supp. 333 (D.C. N.Y.

1950) .................................................................. 38

United States v. Bausch & Lomb Optical Co.,

321 U.S. 707 ....................................................... 38

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S.

319 ...................................................................... 38

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 .. 38

United States v. United States Steel Corp.,

223 F. 55 (D.C. N.J. 1915), aff’d 251 U.S.

417 ...................................................................... 38

V. Conclusion ............................................................. 40

Imfrii States (Emtrt nf Appeals

Tenth Circuit

No. 8523

The Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools, I ndependent District N o. 89, Oklahoma

County, Oklahoma, a Public Body Corporate, Jack F,

Parker, Superintendent of the Oklahoma City, Okla

homa Public Schools, M. J. Burr, Assistant Superin

tendent of the Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Public Schools,

Melvin P. R ogers, Phil C. Bennett, W illiam F. L ott,

Mrs. W arren F. W elch and F oster E stes, Members

of the Board of Education of Oklahoma City Schools,

Independent District No. 89, Oklahoma County, Okla

homa, and Their Successors in Office,

Appellants,

versus

R obert L. Dowell and V ivian C. Dowell, Infants, by

A. L. Dowell, Their Father and Next Friend, E dwina

H ouston H elton, a Minor, by Her Mother, Gloria

Burse, and Gary R ussell, a Minor, by His Father,

George Russell,

Appellees.

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case involves a suit by Negro plaintiffs against

the Oklahoma City Board of Education and its agents as

defendants to enjoin them “from continuing to enforce

2

rules, regulations, and procedures which affect and result

in the maintenance of segregated schools in Oklahoma

City, . . . from assigning plaintiffs and the members of

the class they represent to racially segregated schools, . . .

and from refusing to adopt and execute plans to eliminate

existing patterns of racial segregation in the public schools

of Oklahoma City” (R. 39-41). The lower court granted

the requested relief in two opinions and orders, the first

on July 11, 1963 (R. 50-82), and the second on Septem

ber 7, 1965 (R. 147-165). Defendants-appellants have ap

pealed the latter order which requires them to develop

and institute an effective plan of desegregation and specifies

certain standards for an adequate plan. Plaintiffs-appel-

lees seek to uphold the district court’s order.

I.

Legal Segregation in Oklahoma City Public Schools

and Practices Which Continued Segregation, from 1907

to Date of District Court’s Order.

For nearly fifty years, from the time of its admission

into the Union in 1907, the State of Oklahoma maintained

legally required segregation of Negro and white students

in public education as well as segregation of the races in

other public activities (R. 56). The Constitution of Okla

homa, Article XIII, Section 3, provided: “ Separate schools

for white and colored children with like accommodation

shall be provided by the Legislature and impartially main

tained” (R. 56).

This state constitutional requirement was implemented

by a statutory structure (Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes,

Sections 5-1 through 5-8 and 5-11), which provided that

3

(1) “ The public schools of the State of Oklahoma shall

be organized and maintained upon a complete plan of

separation between the white and colored races . .

(2) members of each district school board must be com

posed exclusively of members of the majority race; (3)

private educational institutions must also be completely

segregated; (4) any teacher or school official who permits

a child to attend a school with members of the other race

is guilty of a misdemeanor; (5) any student who attends

a school with members of the other race is guilty of a

misdemeanor; and (6) transportation will be furnished

to other districts by those districts which do not maintain

schools for a particular race (R, 56-58). It is undisputed

that the State of Oklahoma did in fact maintain the com

pletely segregated educational system required by its con

stitution and statutes for nearly fifty years, up until

the time of the second Brown decision in 1955.

In addition to the laws requiring segregation in all

major public activities of the State, the district court

found that residential segregation was customary and

legally supported by statute and court enforcement in

Oklahoma over a long period of time:

[W]hen new additions were added to the cities and

towns in Oklahoma, it was generally the practice of

the developers to provide in the plats restrictive

covenants on lands used for new homes or dwelling

places, prohibiting the sale of lands or lots or the

ownership by persons of the Negro race. These restric

tive covenants also generally provided some penalty

for an attempt to violate them. In the case where

lands or lots were sold at a tax sale in Oklahoma,

these restrictive covenants survive the sale (68 O.S.A.

Section 456) (R. 58).

4-

The district court also found that this general state prac

tice of residential segregation with its supporting legal

structure existed in Oklahoma City:

The residential pattern of the white and Negro people

in the Oklahoma City school district has been set

by law for the period in excess of fifty years, and

residential pattern has much to do with the segrega

tion of the races. . . . The east and southeast portion

of the original city of Oklahoma City was Negro,

and all other sections and districts of the original

city of Oklahoma City were occupied by the white

race. Thus the schools for Negroes have been centrally

located in the Negro section of Oklahoma City, com

prising generally the central east section of the city

(R. 59).

After the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board

of Education, the Oklahoma City Board of Education made

the following public statement of policies:

Statement Concerning Integration Oklahoma Public

Schools 1955-1956

August 1, 1955

All will recognize the difficulties the Board of Edu

cation has met in complying with the recent pro

nouncement of the United States Supreme Court in

regard to discontinuing separate schools for white

and Negro children. The Board of Education asks

the cooperation and patience of our citizens in its

compliance with the law and making the changes that

are necessary and advisable. This action requires the

Oklahoma Board of Education to change a system

which has been in effect for centuries and which is

desired for many of our citizens.

5

Boundaries have been established for all schools.

These boundaries are shown on a map at the City

Administration Building and maps are being dis

tributed to each school principal. These new bounda

ries conform to the policies, always followed in estab

lishing school boundaries. They consider natural

geographical boundaries, such as major traffic streets,

railroads, the river, etc. They consider the capacity

of the school. Any child may continue in the school

where he has been attending until graduation from

that school. Bequests for transfers may be made and

each one shall be considered on its merits and within

the respective capacity of the buildings (R. 60).

The foregoing resolution indicates that the Board of

Education, as compliance with the Supreme Court’s deci

sion, undertook only to redraw school boundaries to elimi

nate obvious duality of zones based on race. Certain new

school boundaries were established (R. 61). The formerly

Negro Douglass High School and related Negro elementary

schools in the east central area of Oklahoma City became

the public schools for that district. Many white families

moved out of the east central area and many Negro families

moved into the area (R. 61). As the number of Negro

families in the east central area increased, the facilities

of Douglass High School were enlarged considerably

through the use of temporary or portable classrooms

until an enrollment of 1,820, which was the largest in the

school system, was reached—while Northeast High School

(in a white area) continued at an enrollment of 1,215

students without any temporary or portable facilities (R.

68, 74). This arrangement was in lieu of a re-zoning which

would have distributed students more evenly among the

various high schools, but which would also have lessened

the amount of segregation of the races. With respect to

6

the assignment of high school students from dependent

school districts (those without high schools) outside the

city to high schools within the city, school officials con

tinued their policy of assigning Negroes to “ Negro” schools

and whites to “white” schools (E. 64). Negro plaintiff

Robert Dowell was automatically assigned to all-Negro

Douglass High School when he sought admission to the

Oklahoma City high schools from outside the city (R.

63-64) while a white child similarly situated would have

been assigned to a “white” school.

The effects of the relatively small amount of desegre

gation which necessarily took place because of the con

solidation and elimination of dual school zones were coun

teracted, the district court found (R. 79), by the Board

of Education’s “minority to majority” transfer policy

which was maintained through 1963 until invalidated under

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373 U.S.

683 (1963) by the original district court order. The Board

formally adopted a statement of the policy as follows:

It is the policy of the school board to consider, pass

upon and to practically always grant the applications

of parents for the transfer of their children from

schools where the children’s race is in the minority

to a school or schools solely of the child’s race or in

which the child’s race is in the majority providing

that transfers under policy last above described be

granted only when it is the opinion of the parents

of the child and the district that such transfer is

necessary for the best interest of the child as a pupil

(R. 70).

The board assumed that “ the best interest of the child as a

pupil” was that he not be “unhappy” as a result of being in

a minority racial position, and that this unhappiness was

7

sufficiently evidenced by the parents’ request to change

schools (R. 66). The district court found that “ the policy

set forth in this resolution is the same policy the school

board has followed at all times since 1955. There can be

no argument but that such a policy is designed to per

petuate and encourage segregation . . .” (R. 70).

The combination of the Board of Education’s zoning and

transfer policies successfully held down desegregation.

This is indicated by a comparison of the racial composition

of individual schools for 1959-60 and 1964-65:

Total

Schools White Negro Integrated

1959-60 73 12 7

1964-65 81 14 12

(R. 97)

Elementary

Schools White Negro Integrated

1959-60 62 9 6

1964-65 67 11 9

(R. 100)

Secondary

Schools White Negro Integrated

1959-60 11 3 i

1964-65 14 3 3

(R. 103)

Note: The working definition of an “ integrated” school used by the expert

panel appointed by the district court was a school which is less

than 95% white or less than 95% non-white.

There were 13 new elementary schools in operation in

1964-65 which had not been in operation in 1959-60 (some

8

of the old schools had been closed down or combined),

and all of these were segregated—11 completely so and

2 with 99% members of one or the other race (R. 99).

There were 6 new secondary schools in operation in 1964-65

which had not been in operation in 1959-60, and 5 of these

were completely all-white or all-Negro (R. 101-102). There

were white high school students who lived in the all-Negro

Douglass High School area but none attended Douglass

in any of the years from 1954-55 through 1962-63 (R. 65).

All of this led the district court to conclude that “ since

August 1, 1955, the only integration has been in the fringe

areas as between minority Negro residential pattern and

the majority white residential pattern” (R. 79), and “ that

evidence of gerrymandering or otherwise of maintaining

separate and distinct schools for Negroes and schools

for whites can be seen in a review of the testimony”

(R. 77).

Racial segregation of students and teachers in public

education was further preserved by the Board’s teacher

assignments during the period since 1955. The district

court found that “ during the school year 1954-55 there

were no Negro teachers assigned to teach white students

in the white schools or white and Negro schools where

the white students were predominant and the same was

true for the year 1961-62 and all years in between” (R. 65).

The Superintendent stated the reason for this policy,

which indicated his belief in the undesirability of contact

between members of different races: “ I have advised the

Board and have concluded that nothing would be gained

educationally by a desegregation of staffs and that as a

matter of fact the appointment of Negro teachers in cer

tain schools and the mixing of staffs could very well

detract from the quality of the instructional program in

9

Oklahoma City; and that there would be only one reason

that I could think of for doing this, and it would not be

an educational reason. It would be merely for the sake

of integration . . (E. 76).

II.

The District Court’s Order Authorizing An Expert

Study to Formulate an Effective Plan for Desegregation

of the Oklahoma City Public Schools.

Based on the foregoing, the district court concluded

in its opinion of July 11, 1963, that “ the School Board has

not acted in good faith in its efforts to integrate the

Oklahoma City Public Schools, as defined and required in

the Brown cases, as to pupils and personnel” (R. 76). The

court noted as an element of this finding of lack of good

faith, the failure of the board to engage an expert who is

familiar with the particular problems raised by the duty

to desegregate a school system (R. 79). The court then

ordered the school board to file a comprehensive plan of

desegregation (R. 82).

The school board adopted another “ Policy Statement”

on January 14, 1964, in response to the court’s order,

which stated the general purposes of the Oklahoma City

public schools, the policy of attendance zones based on

“neighborhood schools,” certain criteria for the granting

of special transfers, and the existence of opportunity for

any teacher to apply for any position in the system (R.

105-108). Concluding that this policy statement was still

inadequate to achieve desegregation of the Oklahoma City

public schools, the district court at the hearing on the plan

on February 28, 1964, suggested that defendant school

board employ an outside expert to draft an effective plan,

10

and that if they chose not to do so he would invite the

plaintiffs to do so (R. 199-202). Defendant school board

refused to employ such an expert (R. 83-84). Plaintiffs

then moved for authority to undertake such a study (R.

87-88), which motion was granted by the court on June 1,

1964 (R. 90-91).

The experts commissioned to undertake the study were:

(a) Dr. William R. Carmack, Director, Southwest Center

for Human Relations Studies, The University of Okla

homa, Norman, Oklahoma. Dr. Carmack advised that per

sonnel of the Human Relations Center under his super

vision were prepared and qualified to gather information

concerning school curriculums, pupil distribution, faculty

distribution, school zones, transfer procedures and other

relevant facts necessary for the proper evaluation of the

problem, (b) Dr. Willard B. Spaulding, Assistant Director,

Coordinating Council for Higher Education, San Fran

cisco, California. Dr. Spaulding is considered one of the

outstanding educators in the nation. He has wide ex

perience in public school administration, having served as

Superintendent of Schools in Massachusetts, New Jersey

and Oregon. He is a former Dean of the College of Edu

cation of the University of Illinois and Chairman of the

Division of Education of Portland State College. He is

the co-author of several books on education, including

The Public Administration of American Schools and

Schools And National Defense, (c) Dr. Earl A. McGovern,

Administrative Assistant to the Superintendent of New

Rochelle Schools, New Rochelle, New York. Dr. McGovern

has been in school administration since 1955 and was then

involved in the research and evaluation problems in the

New Rochelle school system’s efforts to achieve desegrega

tion of its public schools (R. 88).

11

III.

The Expert Panel’s Analysis of the Deficiencies of

the School Board’s Plan of Desegregation, and Their

Proposals for An Adequate Plan.1

A. The Adequacy of the Overall Plan.

Pursuant to order of the court the expert panel analyzed

both the adequacy of the school board’s plan as a whole,

and that of specific components within it. With regard

to the adequacy of the overall plan, they concluded: “In

overview it may be said the policy statement of the Okla

homa City Board of Education is not a plan to be followed

to achieve integrated public education in Oklahoma City”

(R. 108). Dr. Spaulding, the member of the expert panel

who took primary responsibility for the section of the

report dealing with the overall plan, amplified this state

ment in his oral testimony. He said: “ First, I would like

to state that I do not consider this a plan. As I under

stand planning in the area of public school administration,

and I think I know this quite well, a plan requires a

clear statement of the goals that will be achieved. It

[includes] the description of what is going to be done to

achieve those goals. Thirdly, it indicates the personnel

who are going to be assigned to these tasks; and fourthly,

it includes a time schedule indicating the steps to be ac

complished at particular times, and the time in which the

goal is to be reached” (R. 263).

1 The total school population in 1964-65 was 73,963, with 44,019 ele

mentary and 29,244 secondary students (R. 95-100). The percentage of

white and non-white pupils has remained relatively stable over the last

six years with the white population decreasing slightly from 86.4% to

83.1% while the non-white population increased from 13.6% to 16.9%

(R. 95). The total number of schools in 1964-65 was 107, with 87 ele

mentary and 20 secondary schools (R. 95-102).

12

In analyzing the board’s two stated purposes of public

education in Oklahoma City of (1) providing the best

possible educational program for every pupil, and (2) pro

viding equal educational opportunity for all without refer

ence to any hereditary or environmental differences, the

expert panel pointed out in their report that “equal oppor

tunity to profit from the best possible educational pro

grams occurs most frequently when programs are designed

to meet individual differences among pupils. When such

differences are found to exist in substantial numbers of

cases, wise educational planning yields adaptations of

programs so that all students . . . may learn from them”

(R. 108). They also noted that the Oklahoma City public

schools now provide programs which are adapted to a

number of pupils, such as those for the physically handi

capped, slow learners, youth with special social and eco

nomic problems, etc. (R. 109). Dr. Spaulding again ampli

fied these statements in oral testimony: “It seems to me

that these two statements [of purposes] are self-contra

dictory. If one is to provide the best possible educational

program for every pupil, then one must necessarily take

into account the individual differences which exist and

which exist among wide numbers of students . . .” (R.

263-264).

Dr. Spaulding suggested that it is impossible to have

an effective desegregation plan without considering factors

of race, economic background, etc., since a system that at

one time had been segregated cannot be effectively deseg

regated unless affirmative steps are taken (R. 270). For

example, he said, “ I think we recognize that in any school

system which was segregated, that the location of build

ings was determined by the pattern of segregation rather

than by criteria which might have been used otherwise.

13

Obviously if one is going to have a school into which only

Negroes would be assigned, it is located in an area where

Negroes can be assigned to it . . . so that generally in

school systems of this character, the location of individual

buildings is not the same as would be found in a city which

was not segregated from the beginning” (R. 270-271).

He concluded that the failure to do more than simply issue

a policy statement that “we no longer believe in segregated

schools” would be ineffective in changing the patterns of

a segregated system (R. 271-272).

Dr. McGovern, in oral testimony, noted that during the

five year period of the operation of the school system

which the panel studied, some small progress in terms

of the number of integrated schools had been made. How

ever, he concluded: “As we examined it, we kept turning

these things over, it became more obvious that this was

not anything, that this was not due to any overt action

I believe on the part of the Board of Education to provide

for an integrated school system” (R. 214).

B. Transfer Policies.

Dr. McGovern, who took primary responsibility for the

section of the report dealing with transfers, pointed out

that the board’s present transfer policy continues to per

petuate the segregationist effects of the “minority to

majority” policy which was invalidated in 1963. Up until

that time there had been four or five thousand transfers

annually (R. 218). Under the present policy, a pupil who

successfully transferred under the “minority to majority”

policy before 1963 is allowed to remain in the school to

which he transferred. Furthermore, a brother or sister

of such a student may also obtain a transfer to that school

under the policy permitting transfers to make it possible

14

for two or more members of the same family to attend

the same school (R. 218, 107), Based on detailed statistical

study, he also said that the “good faith” transfer criterion

further provided white pupils with an effective loophole for

escaping from integrated school situations (R. 220, 113).

He concluded that under the board’s present policy it is

still possible for many parents to achieve the same results

as they might have under the “minority to majority” trans

fer policy (R. 223-224). He also noted that the result of

some whites getting transfers out of schools with Negroes

is an ever increasing tendency of remaining whites to also

attempt to transfer out (R. 221).

As a remedy for the effects of these transfer policies

and the general failure of the board to take affirmative

action to correct the effects of segregation, the expert

panel proposed a “majority to minority” transfer policy

which would turn the old “minority to majority” policy

inside out (R. 115). The “majority to minority” policy

would permit an elementary school pupil, if he were in a

majority group, to transfer to a school in which he was

in a minority. Thus if the attendance area for a school

was predominantly Negro (over 50%), Negro pupils could

transfer out. However, the Negro pupils could transfer

only to schools in which they would be in a minority, i.e.,

white schools (over 50%) (R. 115). The report said:

“Admittedly, due to present circumstances, it is not likely

that many white pupils would take advantage of this policy,

but it would provide Negro pupils—especially those who

care enough—with a way for escaping from the restrictions

of the present neighborhood school plan” (R. 115). In

support of this proposal as a workable means of helping

to remedy the past effects of segregation within the con

fines of the present school system, the report emphasized

1 5

the considerable amount of excess capacity available partic

ularly in the elementary schools (R. 116).2

In amplifying the basis for this recommendation in his

oral testimony, Dr. McGovern noted that in making the

proposal, the panel had carefully considered the capacity

of the various schools in the system. It was for this reason

that they avoided an open enrollment or free transfer

plan where everybody could just go to the school they

wished (R. 230). It was pointed out by Dr. Carmack that

“ this is not a plan that completely ignores attendance

boundaries or the so-called neighborhood concept. This is

in fact in relation to some other plans that are being

utilized, a relatively modest plan” (R. 297).

Dr. McGovern said that the basis for this plan was es

sentially what is being done in his own city (R. 227). He

indicated that the achievement levels of students who had

been in predominantly Negro schools who were distributed

out to predominantly white schools improved: Having

this opportunity to receive an education in a different

milieu had “a very salutary effect, in terms of the distri

2 Excluding three elementary schools for which no data was available,

in 1964-65 the total capacity o f the remaining 84 elementary schools was

54,973 pupils, while the enrollment was 43,752—leaving space available

for 11,221 pupils (R. 103). The 63 all white schools had room for 8,928

additional pupils, and the 6 schools with a majority of white pupils had

room for 1,137 additional pupils—or a total of 10,065 additional pupils.

Forty-five of these 69 schools had room for 100-plus pupils (R. 104).

The elementary schools with all or a majority of non-white pupils had

room for 1,156 additional pupils (R. 104).

Excluding three secondary schools for which no data was available,

in 1964-65, the total capacity o f the remaining 20 secondary schools was

31,936 pupils, while the enrollment was 29,774—leaving space available

for 2,162 additional pupils (R. 104). The 13 all white secondary schools

had room for 262 additional pupils, and the 4 secondary schools with a

majority of white pupils had room for 759 additional pupils— or a total

of 1,021 additional pupils. Six of these 17 schools had room for 100-plus

additional pupils (R. 104). The secondary schools with all or a majority

of non-white pupils had room for 1,141 additional pupils (R. 105).

16

bution of readiness of scores . . . I would say that this is

largely due to the fact that when the youngsters have an

opportunity to receive this education where the expecta

tion of both the pupils and the teachers and all in general

are much higher, that they respond to this” (R. 231-232).

He also said that there were not any effects of a negative

nature on the white population, and furthermore, that

some of the stereotypes that both Negroes and white pupils

had of each other as a result of being in a segregated

school system were broken down when they did have an

opportunity to get together, and that they became less

fearful of each other (R. 233-234).

In his oral testimony, Dr. Carmack suggested an addi

tional effect of a “majority to minority” transfer policy:

“I f there is no attendance boundaries in Oklahoma City

where one could go without anticipating the probabilities

of some Negroes in the adjacent schools, the efforts to

move one’s residence would be minimized; so I would say

that this would have a throw-off effect or a spin-off effect

of probably assisting in the stabilization of the community,

particularly the northeastern section” (R. 298). He em

phasized that at the same time the plan was reasonable

and fair in that it takes into account not only the need

to give substantive relief to the plaintiffs, but also the

concept of freedom of choice. Thus those who do not wish

to avail themselves of the opportunity to take advantage

of a different kind of educational environment do not have

to do so (R. 298).

C. Zoning and Attendance Areas.

The expert panel concluded that the school board’s zon

ing and attendance area policies lacked flexibility needed

to promote progress toward desegregation of schools.

These policies serve, the panel determined, to contain

17

Negroes, and the few whites who do not wish or cannot

afford to move, in present attendance areas or in new

ones established under them. If progress toward desegre

gation of schools is to be achieved, the panel said, the

racial composition of schools must be considered in de

termining the boundaries of attendance areas (R. 109).

Dr. Spaulding, in amplifying the report in his oral testi

mony, noted the confusion which has arisen around the

use of the term “neighborhood school.” He pointed out

that the term “neighborhood” as used in the study of

people is a sociological term wdiich indicates a group of

people having certain kinds of relations with each other.

However, schools are not generally designed for this kind

of a neighborhood, but the boundaries are drawn in order

to get enough students inside the schools to fill them and

to operate them effectively, i.e., in terms of density of

population, size of buildings, etc. (R. 265). It is probably

not proper to attach to these zones the word “neighbor

hood” which has emotional connotations which suggest

that these people are already related to each other and

all know each other, etc. (R. 264-265).

The expert panel recommended in their report that two

sets of adjacent school districts, each containing schools

with grades 7-12, be combined so that one school in each

combined district would house grades 7-9 and the other

would house grades 10-12. The combination of the Harding

and Northeast districts would produce a racial composi

tion of 91% white and 9% non-white, compared to a 100%

white enrollment in Harding and a 78% white enrollment

in Northeast; the combination of the Classen and the

Central districts would produce a racial composition of

85% white and 15% non-white, compared to a racial com

position of 100% wdiite in Classen and a racial composi

18

tion of 69% white in Central (1964-65 enrollment figures)

(R. 118-120).

Dr. McGovern said in oral testimony that the basis for

this recommendation was particularly that the northeast

area of the school district appears to be changing from a

white to a non-white district based on what is happening

in the elementary schools (R. 237). He concluded: “If

the decision is made to do nothing, they have made the

decision . . . that they will have the same kind of a school

in Northeast as they have in Douglass, that they have in

Kennedy and they have in the Moon area [all Negro

schools]” (R. 237-238).

The practical problems of merging these districts were

considered in detail. The amount of traveling required

of pupils in these merged districts would be no further

than the board now requires of pupils living in the north

west section of the city who are assigned to Northwest

High School (R. 239). Merger should produce no sub

stantially different operating costs because of the effi

ciencies in having large schools (R. 240). Furthermore,

combining these schools would allow for a broader and

richer curriculum, and would bring these high schools

more nearly in line with the other high schools in the

system. For example, at Northwest, there is a 12th grade

class of 800 pupils, one at Grant of 600, one at Capitol

Hill of 731, one at Marshall of 468, and one at Douglass

of 383. The proposed merged schools presently have 12th

grade classes of the following sizes: (a) Central, 162, and

Classen, 240; (b) Northeast, 212, and Harding, 288 (R.

243).

19

D. Faculty Desegregation

The expert panel stated in their report: “ Since a

greater percentage of non-white personnel holds masters

degrees than of white personnel, and since testimony of

the superintendent of schools indicated no difference in

quality of performance between white and non-white per

sonnel, it is assumed that the range of individual com

petence among faculty has no relationship to race” (R.

93-94). They concluded, however, that the integration of

teaching personnel in elementary and secondary schools

has occurred only when the pupils in those schools were

integrated, i.e. that if the pupil enrollment is all-white, so

is the faculty, and similarly, if the pupil enrollment is all

non-white, the faculty is all non-white (R. 95). The re

port said that although the general policy statement of

the school board appeared to point toward impartiality in

respect to employment of faculty and other personnel,

nevertheless “ it is somewhat too cautious to lead to fur

ther progress toward integrated faculties” (R. 110). The

school board’s general policy statement is susceptible of

the interpretation that Negro teachers will be assigned

to schools Avith all-white faculties only when they are

“ ready” to accept Negro teachers, the panel concluded (R.

110).

In order to avoid the disruption of the existing faculty

of individual schools which Avould occur by withdrawing

most of the Negro faculty members from the Negro schools

and distributing them throughout the system, the panel

recommended that “ a majority of the Negro teachers as

signed to all Avhite or to integrated schools should be se

cured by employing new teachers” (R. 114). Based on the

frequency of vacancies in the system, the panel proposed

that “the Board should immediately take action that it will

Avithout reducing either the number of Avhite or the num-

20

her of non-white teachers now employed, integrate the fac

ulty so that, by 1970, the following conditions will prevail:

The ratios of whites to non-whites in, (a) the central ad

ministration of the schools, (b) non-teaching positions

which are filled by certificated personnel, and (c) faculty

in each school will be the same as the ratio of whites to

non-whites in the whole number of certificated personnel

of the Oklahoma City Public Schools. Maintaining these

ratios does not imply any policy in respect to the use of

race as a criterion for initial employment. To the con

trary, it assumes that the superintendent will recommend

for employment, and that the Board will employ, the best

faculty available” (R. 114).

Dr. Carmack amplified the basis for the panel’s recom

mendation in his oral testimony:

. . . if the members of the faculty who are now of a

minority group are as well qualified and there is some

evidence to suggest that they may be better qualified

than their counterparts in the total faculty, there must

be some artificial factor at work if we find them con

centrated closely together, and that it might not be

unreasonable to hope that if random selection were

employed, eventually random distribution should oc

cur.

We ought to find, if we have 15% or 20% or what

ever it might be of this group, and they are just as

well qualified and can function as effectively as the

others, we ought to find them appearing all over the

system in about their ratio on the general faculty

(R. 302).

Dr. Spaulding noted in his oral testimony:

These tables will show also that the Negro teachers

are paid on the average more than the white teachers

21

are paid. Yet if one examines the way in which people

have been placed in the central administration of the

schools, one finds that only 9% of those employed in

the central administration are Negroes in 1964-65;

and I have some difficulty understanding how it is that

if the policy is in truth being followed that the teach

ers with the longest experience, with the highest level

of training on the average and who are paid best on

the average, don’t provide a higher proportion of the

educational leadership of the city in the central ad

ministration (R. 268).

I)r. Spaulding also pointed out an important reason for

the inclusion of specific standards in an adequate plan of

faculty desegregation:

. . . when schools are desegregated there is a tendency

to dismiss Negro teachers or to reduce the number of

Negro teachers employed and to fill these places with

white teachers . . .

One of the things that we were concerned about

then is that any program of integration of faculty have

safeguards which would prevent the occurrence in

Oklahoma City of what has occurred elsewhere—this

has taken place in southern states—and so we were

endeavoring to set up some kind of safeguard here

when we suggest that the current percentage in num

ber of white and Negro teachers be maintained (R.

290).

22

IV.

The District Court’s Order Requiring an Effective

Plan of Desegregation of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools, and Establishing Certain Standards for Such

a Plan.

Based on the foregoing, the district court, on Sep

tember 7, 1965, ordered the school board to prepare:

. . . a further desegregation plan purposed to com

pletely disestablish segregation in the public schools

of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, as to both pupil assign

ment and transfer procedures, and hiring and assign

ment of all faculty personnel.

Said plan shall provide: (1) a statement of goals

to be achieved, (2) descriptions of procedures to be

followed to achieve such goals, (3) a statement of

the personnel to be responsible for carrying out said

procedures, and (4) a reasonably early time schedule

of specific steps to be taken to attain the stated goals.

Said plan shall further specifically provide for:

1. New school district lines for the Harding and

and Northeast High School attendance districts and

the Classen and Central school attendance districts

drawn in accordance with recommendations relating

to said school attendance districts as contained in the

Integration Report to the end that effective no later

than the start of the 1966-67 school year:

a. The Harding (7-12) school attendance district

and the Northeast (7-12) school attendance district

shall be combined into one school attendance dis

trict, . . . The decision as to which school shall serve

grades 7-9 and which school shall serve grades 10-12

23

shall be left to the sound discretion of the school

board, based on an appraisal of existing permanent

facilities and the location of other secondary school

facilities;

b. The Classen (7-12) school attendance district

and the Central (7-12) school attendance district shall

be combined into one school attendance district. . . .

The decision as to which school shall serve grades

7-9 and which school shall serve grades 10-12 shall

be left to the sound discretion of the school board,

based on an appraisal of existing permanent facilities

and the location of other secondary school facilities.

2. A new “majority to minority” transfer policy,

under which policy all pupils initially assigned to

schools where pupils of their race predominate (over

50%) shall be permitted to request and obtain transfer,

if space permits, to schools in which pupils of their

race will be in a minority (under 50%), and such

transfer shall make that his permanent home school

for the grades it provides. . . .

3. A revised special transfer policy containing spe

cific standards and designed to eliminate, as far as

possible, requests for transfer, the intent and/or re

sult of which is to obtain admission to a school in

which the race of the pupil seeking transfer predom

inates. . . .

4. Faculty desegregation of all faculty personnel,

i.e., central administration, certified nonteaching and

teaching personnel, so that by 1970, the ratio of whites

to non-whites assigned in each school of the defen

dants’ system will be the same, with reasonable leeway

of approximately 10%, as the ratio of whites to non-

24

whites in the whole number of certificated personnel

in the Oklahoma City Public Schools.

5. In-service education of faculty, incorporating

recommendations for such training program contained

in the Integration Report, including (1) City-wide

workshops devoted to school integration, (2) special

seminars for administrators and teams of teachers

from each school, and (3) special clinics for all teach

ing and administrative personnel (R. 162-164).

The Court also stated:

The Court does not by this Order intend to say that

the performance of the provisions of this Order will

satisfy and meet the full good-faith requirements of

desegregation as provided by law. Further study and

action of the Board of Education should be under

taken in order for the Oklahoma City Public Schools

to be further and completely desegregated as the law

requires (R. 164).

25

A R G U M E N T

I.

Substantial Evidence Was Introduced of the Existence

and Continuation of Segregation in the Oklahoma City

School System.

Without dispute the State of Oklahoma maintained com

plete segregation in public education for nearly fifty years,

from its admission into the Union in 1907 until the second

Brown decision in 1955,3 and segregation continued in

Oklahoma City thereafter. As indicated by the statutory

structure concerning segregation in public education (see

Statement of the Case, supra) this meant that all planning

concerning schools, all decisions on the location of build

ings, all pupil attendance policies, all faculty assignments,

etc.,—i.e. every facet of the school system -had to be

designed and executed to achieve and maintain “com

plete” separation between the races. Thus the entire pat

tern of operation of the school system and the resulting

action of staff and pupils, and community customs re

lated to schools, were directed toward segregation as an

explicit and overriding goal. Many decisions and most

customs developed during the period of required segrega

tion would necessarily have long continuing effects.

In this context of fifty years’ history of using all of

the state’s resources to maintain a segregated school sys

tem (as well as a segregation generally), the School Board

ostensibly undertook to achieve desegregation required by

the Fourteenth Amendment by simply publicly stating

that certain zone lines would be redrawn.4 It cannot

3 See Statement of the Case, pp. 2-4.

4 See Statement of the Case, pp. 4-5.

26

seriously be contended that such minimal steps could

undo the effects of fifty years of concentrated state effort

to build a segregated school system.

Because of the obvious inadequacy of such a paper

statement to effectively desegregate the schools and the

depth of the roots of the practice of segregation in the

public school system, it is not surprising that the record

shows that School Board decisions and policies following

1955 generally had the effect of maintaining segregation.5

Thus, the Board zoned the all-Negro Douglass High

School in such a way that it remained a predominantly

Negro school, driving whites who lived in the area to

either move out or at least seek transfers to other schools,

thereby increasing residential segregation in the city.

Furthermore, Douglass was continually enlarged by tem

porary facilities so that nearly all Negro high school

students could continue to be assigned to the “Negro”

high school. Negro pupils who came into the Oklahoma

City school system from dependent school districts out

side the city were automatically assigned to predominantly

Negro schools because it was assumed this was where

they wanted to go.6 The segregationist effect of the

Board’s zoning policies is even more graphically shown by

the fact that virtually all of the new schools placed into

operation during the period from 1959-60 through 1964-65

were either virtually all Negro or all white.7 The board’s

assertion that it was to the principle of the “neighborhood

school” to justify perpetuating segregation cannot dis

guise that when it draws zone lines it necessarily knows

obvious facts such as the racial composition of the area

5 See Statement of the Case, pp. 5-9.

6 See Statement of the Case, pp. 5-6.

7 See Statement of the Case, pp. 7-8.

27

and is responsible for racial zones which result; school

zoning has substantial influence on the racial composi

tion of an area because private housing decisions fre

quently are made on the basis of school zones.8

The “minority to majority” transfer policy was, of

course, fundamental to continuing school segregation.9

Whites assigned to formerly and still predominantly

Negro schools were able to transfer out; Negroes assigned

to formerly all-white schools were encouraged to avoid

hostility, which they might have anticipated, by re-segre

gating themselves. The existence of this policy until it

was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1963 belies

Board’s asserted dedication to the “neighborhood school.”

That the combination of the board’s zoning and transfer

policies even after 1963 continued to maintain segregation

is demonstrated by comparing the number of white and

Negro schools in 1959-60 with those in 1964-65; their

number increased.10

That faculty members were assigned to schools only

with members of their own race before 1955, and after

1955 generally continued to be assigned only to schools

where their race predominated (although some whites

could teach in predominantly Negro schools) is conclusive

evidence of perpetuation of racial segregation in faculty

assignments.11

There was, therefore, substantial evidence to support

the district court’s conclusion that the Oklahoma City

public schools have not been desegregated.

8 See Statement of the Case, pp. 16-17.

9 See Statement of the Case, pp. 6-7.

10 See Statement of the Case, p. 7.

11 See Statement of the Case, pp. 8-9.

28

II.

Where There Is Legal Segregation in a Public School

System, the District Court Must Order an Effective

Plan of Desegregation.

A. General Principles.

The Supreme Court held from the beginning that the

constitutional ban on segregation in public education re

quired far reaching affirmative action to eliminate the

practice.12 In the second Brown decision, 349 U.S. 294

(1955), the Court said:

At stake is the personal interest of plaintiffs in ad

mission to public schools as soon as practicable on a

nondiscriminatory basis. To effectuate this interest

may call for elimination of a variety of obstacles in

making the transition to school systems operated in

accordance with the constitutional principles set forth

12 This case does not involve a claim for relief from school segregation

not shown to have resulted from officially sponsored and supported state

action. Thus the several “racial imbalance,” or so called “ de facto,” cases

of B ell v. S ch oo l C ity o f G a ry , In d ., 213 F. Supp. 819 (N.D. Ind. 1963),

aff’d, 324 F.2d 209 (7th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 377 U.S. 924 (1964),

D ow n s v. B oa rd o f E d u ca tion o f K a n sa s C ity , K a n sa s , 336 F.2d 988 (10th

Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 380 U.S. 914 (1965), and B arksda le v. S p rin g fie ld

S ch oo l C om m ittee , 348 F.2d 261 (1st Cir. 1961), cited in appellant’s brief

are irrelevant. As an aside, however, we might note that the right to such

relief has been sustained in B o o k e r v. B oa rd o f E d u ca tion o f P la in field ,

45 N.J. 161, 212 A.2d 1 (1965); B ala ba n v. R u b in , 40 Mise.2d 249, 242

N.Y.S.2d 974 (Sup. Ct. 1963), rev’d, 20 A.D.2d 438, 248 N.Y.S.2d 574

(2d Dept.), aff'd, 14 N.Y.S.2d 193, 199 N.E.2d 375 (1964), cert, denied,

379 U.S. 881 (1964), 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 690; M orea n v. B oa rd o f E d u

ca tion o f M on tcla ir , 42 N.J. 237, 200 A.2d 97, 9 Race Rel. L. Rep. 688

(1964) ; J ackson v. P a sad en a S ch oo l B oa rd , 31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 382 P.2d

878, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 924 (1963); B lo c k e r v. B o a r d o f E d u ca tion o f

M a n h asset, 226 F. Supp. 208 (E.D.N.Y. 1964) ; B a rksd a le v. S p rin g fie ld

S ch oo l C om m ., 237 F. Supp. 543 (D. Mass. 1965), vacated without preju

dice, 348 F.2d 261 (1st Cir. 1961).

29

in our May 17, 1954, decision. Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U.S. at 300.

Recognizing that time might be required to eliminate such

obstacles further indicated the intent of that far reaching

and basic changes be made. The Court directed the dis

trict courts:

They will also consider the adequacy of any plans the

defendants may propose to meet these problems and

to effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscrimina-

tory school system. Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. at 301.

The Supreme Court and the federal courts of appeals

have had frequent occasion in the years since the Brown

decision to reconsider general principles applicable to the

duty to desegregate a school system where there has been

legal segregation. The Supreme Court held in Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958), that under the second Brown

decision, state authorities were “ duty bound to devote

every effort toward initiating desegregation and bringing

about the elimination of racial discrimination in the public

school system.” 358 U.S. at 7.

Recently in Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965), the

Supreme Court treated the “adequacy” of a plan of de

segregation and demonstrated the breadth of the concept,

by holding that racial allocation of faculty would poten

tially render inadequate a pupil desegregation plan. The

Court’s statement that racial allocation of faculty denies

students equality of educational opportunity further dem

onstrates that decisions and policies which tend to pre

serve segregation in any aspect in a school system are

proscribed and must be changed.

30

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has now

clearly held that school boards operating a dual system

are required by the Constitution not merely to eliminate

formal racial criteria, but must affirmatively and com

pletely disestablish segregation in public schools, Singleton

v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d

729 (5th Cir. 1965), 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966). As suc

cinctly stated in the first Singleton case, “ . . . the second

Brown opinion imposes on public school authorities the

duty to provide an integrated school system.” 348 F.2d 729,

at 730.5. This constitutional duty to desegregate is so in

clusive that if the application of otherwise proper educa

tional principles and theories results in the preservation

of an existing system of imposed segregation, the neces

sity of vindicating constitutional rights prohibits their use.

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960); Ross v.

Dyer, 312 F.2d 191, 196 (5th Cir. 1963); Brooks v. County

School Board of Arlington, Virginia, 324 F.2d 303, 308

(4th Cir. 1963).

The Supreme Court and the federal courts of appeals

have further held that the crucial test of the adequacy of

a school board policy in desegregation plan is its effect

in either preserving segregation or promoting desegrega

tion, rather than whether there is an actual showing of

specific purpose on the part of the board to retain segre

gation. Thus plans and policies which have the effect of

preserving segregation are invalid. Goss v. Board of Edu

cation, 373 U.S. 683 (1963); Griffin v. County School Board

of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964); Boson v.

Hippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960); Houston Independent

School District v. Ross, 282 F.2d 95 (5th Cir, 1960). Not

only is effect the crucial test, but the Sixth Circuit has

held, in the context of a challenge to zoning, that where a

board is required to desegregate, the burden of proof rests

31

with it to demonstrate that its policies do not preserve

segregation. Northcross v. Board of Education of the City

of Memphis, 333 F.2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964).

B. Specific Components of an Adequate Plan

of Desegregation,

In Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373

U.S. 683 (1963), the Supreme Court held a “ minority to

majority” transfer provision invalid. The basis for the

decision was that the policy tended to perpetuate the pre

existing racially segregated system, running counter to the

admonition of the second Brown opinion that a plan of de

segregation must be “ adequate.” Thus any other transfer

policy which has similar effects would also be invalid.

However, transfer policies which would have the effect of

promoting desegregation of a school system would stand

on an entirely different footing, because they would im

prove the adequacy of a plan of desegregation rather than

impair it. The United States Office of Education recog

nized this in its Revised Statement of Policies for School

Desegregation Plans (March 1966) implementing Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.A. §2000d) when

it said: “ A school system may (1) permit any student to

transfer from a school where students of his race are a

majority to any other school, within the system, where

students of his race are a minority, or (2) assign students

on such basis.” Revised Statement of Policies §181.33(b).

H.E.W. guidelines are an appropriate mode of desegrega-

ton. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, swpra; Price v. Denison Independent School District

Board of Education, 348 F.2d 1010, 1013 (5th Cir. 1965).

Where a school system has been legally segregated, zone

lines cannot be drawn to preserve a maximum amount of

segregation even though ostensibly based on customary

32

geographical criteria. Northcross v. Board of Education of

City of Memphis, supra; see also Brooks v. County School

Board of Arlington, Va., supra. This principle must be even

more carefully and forcefully applied where there has been

a past history of legal support of residential segregation;

to do otherwise would preserve segregation in education

under the guise of eliminating it. Holland v. Board of Pub

lic Instruction of Palm Beach Fla., 258 F.2d 730 (5th Cir.

1958). Obviously the racial composition of residential areas

must be taken into account when drawing school zone lines

if this result is to be prevented. The general basis of these

decisions again is that a plan of desegregation which in

fact preserves segregation in schools through the use of

zones based on residential segregation cannot logically be

“adequate.”

The constitutional prohibition of segregation in educa

tion applies to faculty assignments. The Supreme Court,

in Bradley v. School Board, City of Richmond, Va., 382

U.S. 103 (1965), clearly recognized the close relation be

tween faculty allocation on a racial basis and the adequacy

of desegregation plans. By reference to the second Brown

opinion’s mandate to desegregate the schools, the Court

indicated that affirmative action would be required to

eliminate the effects of previous faculty assignments on the

basis of race. See Rogers v. Paul, supra. The holding of

the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Singleton v.

Jackson Municipal Separate School Distrct, 355 F.2d 865

(5th Cir. 1966), that the Jackson, Mississippi desegregation

plan must “provide an adequate start toward elimination

of race as a basis for the employment and allocation of

teachers, administrators, and other personnel,” 355 F.2d

at 870, requires an affirmative plan of faculty desegregation

where prior assignments were based on racial segregation.

The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit held in Kemp

33

v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965), that the. “Board’s

failure to integrate the teaching staff” is discrimination

“proscribed by Brown and also the Civil Bights Act of 1964

and the regulations promulgated thereunder.” 352 F.2d

at 22.

III.

The District Court Properly Obtained Expert Testi

mony as a Basis for Formulating an Effective Plan of

Desegregation, and Such Testimony Provided a Reason

able Basis for the Court’s Order.

A. The Propriety of Obtaining Expert Testimony.

Where a court faces issues, proper resolution of which

requires specialized knowledge and which cannot be de

termined intelligently merely with ordinary information,

testimony of persons possessing special knowledge is ap

propriate, indeed, necessary (20 Am. Jur. §775). Whether

expert testimony is required depends primarily on the facts

of the particular case and the question of its appropriate

ness is for the trial court in the exercise of sound discretion.

Duff v. Page, 249 F.2d 137 (9th Cr. 1958). The propriety

of admission of such testimony will not be reviewed unless

manifestly erroneous. Ackelson v. Brown, 264 F.2d 543

(8th Cir. 1959). All expert testimony is admissible if it is

not mere guess or conjecture and if it reasonably tends to

aid the trier of fact in resolving a decisive issue. Padgett

v. Buxton-Smith Mercantile Co., 262 F.2d 39 (10th Cir.

1959).

The reorganization of a school system to eliminate segre

gation is the type of complex problem to which this

principle applies. Although the school board contended

that its own staff was competent to formulate a plan of

34

desegregation, the district court could properly conclude

that the school board’s staff did not have expert knowledge

on the problem of planning for desegregation since they

had always operated within a segregated system, and

since the school board had been demonstrably ineffective

in achieving substantial desegregation of the school system

over a ten-year period.

B. The Expert Testimony Provided a Reasonable

Basis for the District Court’s Order.

The expert panel made a detailed study of the Oklahoma

City school system as a basis for their recommendations.

As detailed supra in the Statement of the Case, the three

experts were all prominent in the field of education and

obviously competent to undertake this task. All of the

sections of the district court’s order establishing standards

for an adequate plan of desegregation are based on the

report and testimony of the expert panel. The general

conclusion of the panel was similar to the holdings of

courts cited above, i.e., that effective desegregation of

a school system which had been segregated requires sub

stantial affirmative action which must be planned in detail

to achieve the goal. The four components of effective

planning which the expert panel outlined were adopted

by the district court. The experts’ statement that in

dividual differences have to be taken into account to

equalize opportunity to obtain the best education, is the

general basis of the district court’s premise that considera

tion of race cannot be avoided in formulating effective

measures of desegregation.13 As the Fourth Circuit re

cently held it is obviously necessary and appropriate to

consider race when attempting to correct racial discrimina

13 See Statement o f the Case, p p . 11-13.

35

tion. Wanner v. County School Board of Arlington City,

Va,, 357 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966).

Having shown that the school system remained primarily

segregated and that the board’s policies generally have

the effect of perpetuating that segregation, it was in

cumbent upon the expert panel to devise specific policies

to promote desegregation. The effectiveness of the past

policy of “minority to majority” transfers in maintaining

segregation suggested that a converse “majority to mi

nority” policy might he effective in producing desegrega

tion. This was confirmed by an extensive analysis of the

pupil composition of each school in the system, which

showed that there was substantial excess capacity, par

ticularly in the elementary schools. That the school sys

tem was able to process several thousand transfers an

nually under the old “minority to majority” policy showed

that this proposal would not impose an undue adminis

trative burden. The expert panel also testified that not

only would the proposal counteract the former transfer

policy and the present transfer policies which continue

to perpetuate the effects of the former policy, but would

also counteract the effects of the board’s zoning policies

which have also fostered segregation through encourag

ing residential segregation. This testimony provided a

more than adequate basis for the “majority to minority”

transfer policy in the district court’s order.14

Many of the experts’ findings regarding “majority to

minority” transfer policy proposal also support the por

tion of the district court’s order consolidating the four

high school districts into two. While this order does not

on its face have the same system-wide effect as the

“majority to minority” transfer proposal, it is appropriate

14 See Statement o f the Case, pp . 13-16.

36

relief for areas of the city which have particularly felt

the effects of the board’s zoning policies in producing

and maintaining residential segregation. That this was

also practical as well as appropriate relief was shown by

the experts’ analyses of such factors as amount of travel

required by pupils in the merged districts, operating costs

of the merged schools, effects on curriculum, and com

parison of size of the merged schools with other high

schools in the system. That the expert panel, after an

exhaustive study of the entire school system, made this

particular proposal, reasonably suggested to the district

court that an adequate plan for desegregation should in

clude such relief. Therefore, it was properly included in

the order.16

The expert panel very carefully considered the proper

remedy for faculty segregation, including qualifications of

Negro and white teachers, necessity for continuity of fac

ulty in individual schools, and annual faculty turnover

rate. They concluded that most Negro teachers to be

assigned to all-white or integrated schools should be se

cured by employing new teachers to avoid unduly disrupt

ing existing faculties of individual schools. However, in

accordance with general requirements for effective plan

ning, they considered there must be some defined goal and

program if faculty desegregation were eventually to be

achieved, and proposed that based on the annual faculty

turnover rate, by 1970 the ratio of whites to non-whites

assigned to each school and in the central administration

should be the same as the ratio of whites to non-whites in

the whole number of certificated personnel in the school

system. This would provide a clear standard for measur

ing the progress of the school system toward desegrega

36 See Statement o f the Case, pp . 16-18.

37

tion of faculty. It would also protect against the tendency

which has developed elsewhere for desegregation of fac

ulty to become a one-way street in which Negro teachers

are squeezed out of the system. The experts’ analyses and

proposal thus provided a reasonable basis for the district

court’s order relating to faculty desegregation.16

rv.

Power and Duty of Court of Equity to Remedy a

Wrong Is Commensurate With the Scope of the Wrong.

The general equity principle is that equity suffers no

right to be without a remedy or, alternatively, that in

equity jurisprudence there is no wrong without a remedy.

Leo Feist, Inc. v. Young, 138 F.2d 972 (7th Cir. 1944).

Where a duty exists equity will provide a remedy for its

violation, and will not permit a wrong to remain unrighted

if there is any possible way to remedy the situation.

Schneider v. Schneider, 141 F.2d 542 (D.C. Cir. 1944).

Because of this inherent general power and duty of a

court of equity to remedy a wrong, equity courts have

broad power to mold their remedies and adapt relief to

the circumstances and needs of particular cases. Dabney

v. Chase National Bank of the City of New York, 201

F.2d 635 (2nd Cir. 1953), cert, dism’d, 346 U.S. 863;

Bowles v. Skagg, 151 F.2d 817 (6th Cir. 1946). Equity

courts have power to determine all of the rights of the

parties and to grant such relief as will finally determine

the issues between them, and the decree should be framed

so that complete justice will be done. Overfield v. Penrod

Corp., 42 F. Supp. 586 (D.C. Pa. 1942), aff’d 146 F.2d 889

(3rd Cir. 1942).

16 See Statement o f the Case, p p . 19-21.

38

The inherent power and duty of a court of equity to

effectively remedy a wrong is graphically demonstrated

in the area of monopoly cases. 15 U.8.C. §4 confers juris

diction on the courts of the United States to prevent

and restrain violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act,

15 U.S.C. §§1-7. However, the scope of the power granted

under that act is determined by classical equity juris

prudence. United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S.

319, holds that in suits to restrain violations of the Sher

man Act, the federal district court, as a court of equity,

has the duty of making the remedy as effective as possible.

The test of the propriety of measures adopted by the court

is whether the required remedial action reasonably tends

to dissipate the effects of the condemned actions and to

prevent their continuance. Indeed, a court can prohibit

the use of admittedly valid parts of an invalid whole.

United States v. Bausch & Lomb Optical Co., 321 U. S. 707.

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 holds that

the relief must neutralize the extension and continued

operating force which the possession of power unlawfully

obtained had brought about and would continue to bring

about, and that this required dissolution of a corporation.

Not only must the court take account of the structure and

position of the defendant corporation itself, but also present

and future conditions in the entire affected industry, to

determine adequately the relief required to undo effects

of the past condemned action and to prevent their con

tinuation, or in the language of the Court, to “ render

impotent” the monopoly power. Schine Chain Theatres

v. United States, 334 U.S. 110, petition denied, 334 U.S.

809; see also, United States v. Aluminum Company of

America, 91 F. Supp. 333 (D.C. N.Y. 1950); and see

United 'States v. United States Steel Corp., 223 F. '55

(D.C. N.J. 1915), afPd 251 U.S. 417.

39

Problems of formulating appropriate and effective relief

in school desegregation suits bear considerable similarity

to those involved in suits to prevent monopolization by a