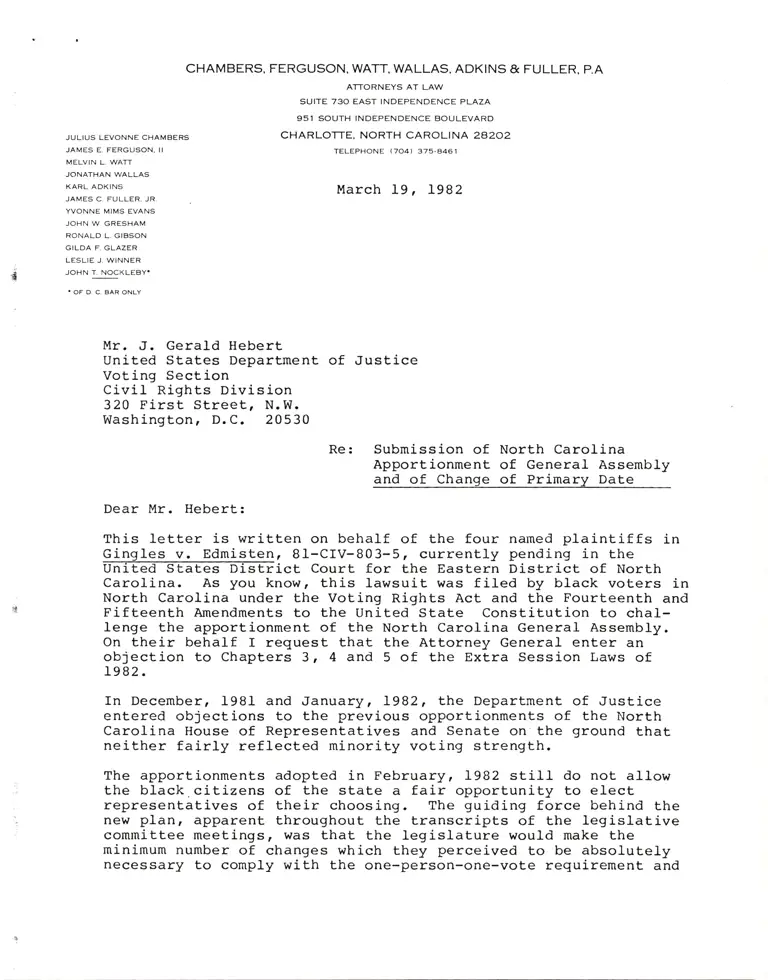

Correspondence from Chambers and Winner to Hebert

Correspondence

March 19, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Williams. Correspondence from Chambers and Winner to Hebert, 1982. 167011fd-da92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/da8efe05-6ade-49bb-be9d-a079a4ac4a3d/correspondence-from-chambers-and-winner-to-hebert. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

CHAMBERS, FERGUSON, WATT. WALLAS, ADKINS 8c FULLER, P.A

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

SUITE 730 EAST INDEPENDENCE PLAZA

951 SOUTH INDEPENDENCE BOULEVARD

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

JAMES E. FERGUSON. II

MELVIN L. WATT

JONATHAN WALLAS

KARL ADKINS

JAMES C. FULLER. JR.

YVONNE MIMS EVANS

JOHN W. GRESHAM

RONALD L. GIBSON

GILDA F, GLAZER

LESLIE J. WINNER

JOHN T NOCKLEBY‘

' OF D C. BAR ONLY

CHARLOTTE. NORTH CAROLINA 28202

TELEPHONE (704) 375-8461

March 19, 1982

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

United States Department of Justice

Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

320 First Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530

Re: Submission of North Carolina

Apportionment of General Assembly

and of Change of Primary Date

Dear Mr. Hebert:

This letter is written on behalf of the four named plaintiffs in

Gingles v. Edmisten, 81—CIV-803-5, currently pending in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of North

Carolina. As you know, this lawsuit was filed by black voters in

North Carolina under the Voting Rights Act and the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the United State Constitution to chal—

lenge the apportionment of the North Carolina General Assembly.

On their behalf I request that the Attorney General enter an

objection to Chapters 3, 4 and 5 of the Extra Session Laws of

1982.

In December, 1981 and January, 1982, the Department of Justice

entered objections to the previous opportionments of the North

Carolina House of Representatives and Senate on the ground that

neither fairly reflected minority voting strength.

The apportionments

the black_citizens

adopted in February, 1982 still do not allow

of the state a fair opportunity to elect

representatives of their choosing. The guiding force behind the

new plan, apparent throughout the transcripts of the legislative

committee meetings, was that the legislature would make the

minimum number of changes which they perceived to be absolutely

necessary to comply with the one—person-one—vote requirement and

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

March 19, 1982

Page 2

to pass Justice Department scrutiny. The result is that the

plans are largely based on the two sections of the North Carolina

Constitution, Article II, §3(3) and §5(3), which you previously

found necessarily submerge concentrations of black voters. In

addition, since the goal was to pass scrutiny rather than to

allow for fair representation of black citizens, the modifications

are frequently more in form than in substance, and districts

which on first glance appear to be "majority black districts"

are designed not to allow the black community actually to elect a

representative of its choosing. The result is an assurance that

black citizens will continue to remain seriously underrepresented

in the North Carolina General Assembly.

I. Chapter 5 of the Extra Session Laws of 1982, the North

Carolina Senate.

There are two primary problems with the Senate plan: (A) District

#2, in the rural northeast, was enacted with the purpose and

effect of assuring that the black citizens of that district

cannot elect a representative of their choosing; and (B) the

failure to divide counties not covered by Section 5 dilutes the

voting strength of black citizens in counties which are covered

by SS.

A. Senate District #2 was drawn to dilute black voting strength.

District # 2 in the Senate plan has a black population of 51.7%.

The adjacent district, district #6, has a black population of

49.1%. Thus, this is a classic example of fracturing black

communities to divide their voting strength and, thus, prevent

either half from exerting real influence over the election. In

examining the Senate Redistricting Committee transcripts, it is

evident that the purpose of creating a 51.7% district was to give

the appearance of having a majority black district without in

fact threatening the re—election of the white incumbent by real

competition from a candidate who is the choice of black citizens.

I have based this conclusion on the following excerpts from the

transcripts as well as from the newspaper articles which I have

attached as Exhibit A.

l. The tone for the meeting was set by the staff to the

meeting in his preliminary remarks about the proposed plan:

[I]t was the opinion of the counsel that this is

the minimum that you have to do at this point to

our knowledge to pass justice and the challenges

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

March 19, 1982

Page 3

under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

(1/28/82, p.11)

Thus the purpose had nothing to do with truly avoiding dilution;

the only goal was to pass muster.

2. Kathleen Heenan, retained counsel to the committee,

repeatedly informed the committee that a 50—51.5% black district

could not elect a representative of black choosing and that the

committee should increase the percent black population in that

district at least to 55% (See, e.g. 2/9/82, tape 3, pp. 3-5, and

Tape 4, p. 5).

3. Both Ms. Heenan and Jerris Leonard, also retained counsel

to the committee, informed the committee that staff had drawn a

district in that area that was over 59% black, was compact, and

was not gerrymandered. (1/29/82, p. 27; 2/9/92, Tape 4 p. 6). No

one ever asked to consider or even see these plans before the

various votes were taken.

4. In addition, the committee had before it a 61.2% minority

district in roughly the same area which had been presented at the

public hearing by the North Association of Black Lawyers. Senator

Frye specifically informed the committee of the proposed district.

(2/9/92, Tape 1, P. 7).

5. Senator Frye moved that the chair appoint a subcommittee

to propose a plan which would establish a 58% black district in

the Northeast and single member districts in Guilford with at

least one majority black district. The motion was only to have

the proposal presented to the committee for review, not that it

be adopted. First Senator Frye was convinced to reduce the

percent black to 55%, then the motion was defeated anyhow. The

members were so opposed to having a true majority black district

that they did not even want to know what their options were.

(29/92, Tape 4, pp. 7-12)

6. The main people who expressed concern over Senator

Frye's motion were Senators Allsbrook and Harrington, the senators

who live in districts 2 and 6. Harrington openly opposed any

plan that would have increased the black percent over 52% saying

that that was enough. (2/9/82, Tape 4 pp. 8-10) It is interest-

ing to note that in an earlier exchange between Senator Harrington

and Jerris Leonard, Harrington said that he liked the district as

drawn and appreciated Leonard's giving him a rationale to justify

it publicly. (1/28/82, p. 29—31)

7. Frye's subsequent motion to divide Guilford County into

three single member disticts with one majority black district

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

March 19, 1982

Page 4

passed unanimously without discussion (2/9/82, Tape 5, p. 3)

making it clear that the opposition to Frye's earlier motion was

to increasing the black population of the second district, not to

dividing Guilford County.

8. In later discussion Senator Daniels implied that Senator

Harrington drew the boundaries of the second district. (2/9/82,

Tape 5, p. 2) If this is true, that is further evidence that the

purpose was to protect Harrington, not to allow black citizens to

choose their own representative.

9. During the floor debate on the Guilford County split,

Senator Cocherham stated that Guilford would have the only black

district. (2/10/82, Tape 3, p.2) This is evidence that other

members did not perceive district 2 as a district subject to the

control of black voters.

10. The adopted district #2 adheres to the Article II,

§5(3) prohibition against dividing counties. It is composed of

whole counties only. It was the Senates adherence to this pro-

vision, to which the Department of Justice previously objected,

that prevented the Senate from creating a district in the north-

east with an effective black voting majority.

B. The failure of the Senate to divide counties not covered by

SS dilutes minority voting strength in covered counties.

Especially in the central and western parts of the state, the

counties covered by §5 do not tend to be contiguous with each

other. Thus, the refusal of the Senate to divide non—covered

counties, except for one—person—one—vote reasons, often acted to

dilute black voting strength. Forcing those counties to be

combined into districts with other rural counties, each with

submerged black communities, instead of with a part of a larger,

urban county, assured that the black population of the covered

county would remain diluted.

The best example of this is Gaston County. It is proposed to be

combined with Lincoln, Cleveland and Rutherford Counties to form

a three member Senate district which is 13.9% black. However, if

the eastern part of Gaston County, including the black community

of Gastonia were combined with some of the western part of

Mecklenburg, the result would be a 59% black district which would

include 30% of the black citizens of Gaston County. See Exhibit

B attached.

In this instance as well as in part A, above, the "do as little

as you think you can get by with" approach assured the needless

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

March 19, 1982

Page 5

continued dilution of minority voting strength.

These examples demonstrate that the Senate plan adopted continues

to have the effect and in some instances the purpose, of diluting

black voting strength and assuring the continuation of a Senate

in which black citizens are not fairly represented.

II. Chapter 4 of the Extra Session Laws of 1982, the North

Carolina House of Representatives.

The enacted apportionment for the House illegally dilutes minority

voting strength in counties primarily in four ways: (a) by

submerging the black community of Cumberland County into the

larger white community; (b) by submerging the black community of

Edgecombe, Nash and Wilson Counties into a three member majority

white district; (c) by retaining Hoke County, Robeson County, and

Scotland County a three member district, and (d) by refusing to

divide even §5 counties except to create districts with a majority

of black residents.

A. Cumberland County

The legislature purported to create a majority black district in

Cumberland County. In fact, only 42.6% of the residents of the

"Fort Bragg" district are black. Although 84% of registered

voters in the district are black, this district does not assure

fair representation fo Cumberland County's black citizens for the

following reasons.

1. Because of the small number of registered voters, only

3,170, the racial balance of the district could be very easily

tipped. It would not take much of a voter registration effort at

Fort Bragg to turn this majority white population district into a

majority white registration district. This was recognized by the

House committee before the plan was enacted. (2/5/82, Tape 3, p.

5)

2. The bulk of Cumberland's black community remains sub-

merged into a four member 27.6% black district. This also was

recognized by the committee before they voted on the plan (2/5,

Tape 3, pp. 8—9); representative Hege pointed out that the pro-

posal resulted in 28,121 black voters remaining submerged in a

multimember district and giving 2,664 black voters the oppor—

tunity to elect a representative instead.

3. The legislature had the opportunity to create a single

member district that would have allowed the bulk of the black

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

March 19, 1982

Page 6

community of Cumberland County to be represented. The legisla—

tive staff presented the committee with an alternative district

which was 56.8% black in population without any military per-

sonnel included. This alternative was rejected. In addition,

the map presented the public hearing by the N. C. Association of

Black Lawyers had a Cumberland district which is 54.9% black.

(It consists of census tracts 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 10, ll, 12, l3, 14,

21, 23 and 24; see Exhibit C.) Finally, at the request of

Representative William Clark (D—Cumberland), I had a plan pre—

pared for Cumberland County which contained five compact single

member districts, included the 54.9% black district described

above, and met other criteria which he suggested, but he did not

present that plan to the House.

4. The plan fractures the black community of Cumberland

County. The heart of the black community is divided between the

majority white multi-member district and the majority white

single member district.

5. A group of black leaders from Fayetteville met with the

Cumberland County delegation and requested that Cumberland

County be divided into single member districts with at least one

majority black district. They specifically opposed the Ft. Bragg

option. A spokesman for this group, Thomas Council, reiterated

this position at the public hearing on February 4, 1982, but the

wishes of the black community were ignored. (Note: Mr. Council's

statement is the last statement in the copy of the public hearing

record which I received.)

6. Because the "black" representative under the current

proposal represents so few people, his/her voice will have

little weight in the General Assembly, and he/she will not be

able to represent anyone very effectively, much less the black

community of Cumberland County.

B. Edgecombe, Nash and Wilson Counties

Prior to the Department's objection to the October, 1981 House

plan, we submitted to the Department a sample apportionment of

these three counties dividing them into four single member dis-

tricts. Fairly drawn, a 63% black district is created leaving

the remainder to be divided into three majority white districts.

There is no evidence in the record that anyone even considered

avoiding the dilution of minority voting strength in this area of

the state. See Exhibit F

C. Hoke, Robeson, and Scotland

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

March 19, 1982

Page 7

Under the enacted apportionment of the House of Representatives

these three counties form one three member district which is

43.8% white, 29.8% black, and 26.4% indian. I separate the

black and indian percentages because their is no history of

coalition between the two groups in these counties. Thus, this

cannot be fairly represented to be a minority district. In

addition, a majority of the registered voters in the district

(approximately 52%) is white.

If the State had not followed the North Carolina Constitution's

concept of not dividing counties and had created single member

districts in that area, then if fairly drawn, one would have a

majority of Indians, and one would have a strong plurality of

black voters. (See Exhibit D showing one district 51.5% Indian,

23.3% Black and 25.2% white, and one district 42% black, 20%

Indian and 38% white.)

By continuing to use a system of keeping white counties in tact,

the state has avoiding concentrating the vote of either minority.

D. The State has failed to concentrate minority vote in most

§5 covered counties.

The ground rule for reapportionment used by the state, evident

not only from their written criteria, but also from the

House Redistricting Committee transcript, was that counties

would be divided for only two reasons: (1) if necessary to

comply with one—person-one-vote; and (2) if a majority black

district would be created from counties covered by §5. Thus in

all counties covered by §5 which have substantial concentrations

of black citizens, but not enough to make a majority black

district, those concentrations are submerged.

For example, in the Bladen, Pender, Sampson County area, the

proposed plan has one two member districts which is 38% non-

white. The North Carolina Association of Black Lawyers' plan in

the same area has a single member district 47% non—white. While

this is not a majority, it does avoid the dilution of minority

voting strength which was caused by the legislative's unwilling—

ness to divide counties except when they perceive that it was

absolutely necessary.

III. North Carolina's failure to create single member districts

in the counties not covered by §5 denies black citizens

in covered counties the right to use their vote effectively.

The record of the proceedings is replete with evidence that the

General Assembly, particularly the House, intentionally diluted

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

March 19, 1982

Page 8

black voting strength in Mecklenburg, Forsyth, Durham and Wake

Counties. See also newspaper articles attached as Exhibit E.

The evidence was particularly strong in Mecklenburg in which the

committee said, in essence, unless we submerge the 100,000 black

citizens in with the 300,000 white citizens, the white incumbent

democrats will not be able to be re—elected. The choice was

clearly made to deprive black citizens from electing a representa—

tive of their choice in order to keep them as part of the larger

voting pool. Plans were presented and rejected both in committee

and on the floor that would have created two majority black

districts out of Mecklenburg's eight. The same was true for

Forysth, Durham, and Wake Counties.

In order to understand how this affects the black citizens of the

covered counties, one must realize that the North Carolina legis-

lative is a unitary body. It will do the black citizens of

Guilford County little good to elect a representative of their

choosing, one out of 120 House members, if he or she sits in a

body that so grossly underrepresents black citizens that the

voices of the few from the covered counties is lost in the roar

of voices from the large multi—member districts. Allowing the

black citizens of Guilford County to elect a representative to a

legislative body in which he or she can have no effect prevents

those black citizens from using their vote effectively. The

intentional dilution of black voting strength is the non-covered

counties assures the continuation of a legislative body unrespon-

sive to the needs of the black citizens throughout the state,

those who live in covered counties as well as those who live in

non—covered counties.

IV. Chapter 3 of the Extra Session Laws of 1982, which changes

the election schedule for the primary election, has a

disparate effect on black citizens.

Chapter 3 sets the schedule for the filing for legislative seats

and for the primary election. The extremely short amount of time

for filing, registering to vote, and campaigning, is a dramatic

change from the usual schedule and will have a harsh impact on

black citizens, black voters, and black candidates. The statute

allows for as little as seven days for the candidate to file

after the plans are approved, seven days for voters to register

after the close of filing, and one month and six days from the

close of filing to the primary. This is in contrast to the usual

schedule in which voters and candidates know the boundaries of

the district they are in for months, if not years, the candidate

filing time is four to five weeks, N.C.G.S. §163—106(c), and

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

March 19, 1982

Page 9

there is three months between the end of filing and the election

(from the first Monday in February to the first Tuesday following

the first Monday in May). See N.C.G.S. §163—1.

This short campaign schedule will work to the disadvantage of all

non—incumbents. In understanding the disproportionate impact on

black citizens, it is important to realize that all of the incum-

bents from counties covered by §5 were elected from districts

with a majority of white voters, and all of these incumbents,

with the exception of Henry Frye from Guilford County, are

themselves white. Thus, any change that disadvantages non—

incumbents also disproportionately impacts black voters and black

candidates.

For example, the proposed District Two of the Senate has pre-

viously been majority white in population. It would be virtually

impossible for black citizens to recruit a candidate of their

choosing in time to meet the filing deadline and in time to raise

the money and do the campaign activity necessary to prevail over

the white incumbent.

In addition, for black citizens, who remain disproportionately

under—registered in counties covered by the Voting Rights Act,

the seven day registration time after the candidates are known

makes it unlikely that a substantial number of black voters will

be able to register in time to vote in the primary.

An additional problem is that North Carolina requires a substantial

filing fee, or in lieu thereof, a petition signed by 10% of the

registered voters for the covered district. Since candidates

cannot begin petitioning for signatures until they know what

district they live in, it will be virtually impossible to get a

petition signed in time to run, thus giving white incumbents

another edge over challengers supported by the black communities.

Finally, the one month between filing and the primary does not

give voters enough time to learn what district they live in and

which candidates are challenging the incumbents in order to allow

black voters, who may not support the incumbents, enough time to

decide which candidate is the candidate of their choosing. Thus,

they are truly deprived of the ability to use their votes effec-

tively.

For the foregoing reasons, I request that the Attorney General of

the United States enter objections to Chapters 3, 4 and 5 of the

Extra Session Laws of 1982 and allow the black citizens of North

Mr. J. Gerald Hebert

March 19, 1982

Page 10

Carolina to have a real chance, not just a facade of a chance,

elect representatives of their choosing.

Sincerely,

72% mm“.

L

evonne Chambers

Leslie J. Winner

LJW:ofh

to