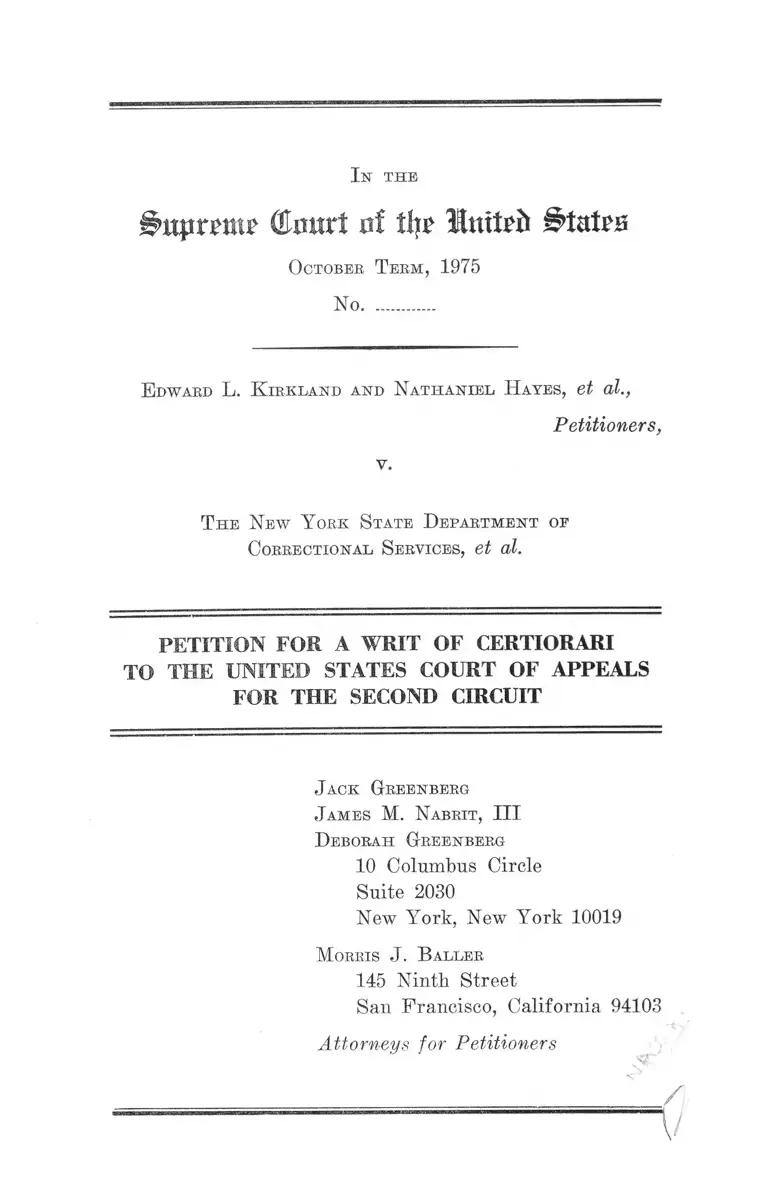

Kirkland v. The New York State Department of Correctional Services Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

May 31, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kirkland v. The New York State Department of Correctional Services Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1976. d4e09d1d-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/da9a681f-eff2-4d50-9fbd-c9dcb47714b8/kirkland-v-the-new-york-state-department-of-correctional-services-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Bnpxmit (ttamt of % litttoft States

October T erm, 1975

No..............

E dward L. K irkland and Nathaniel H ayes, et al.,

Petitioners,

v .

T he New Y ork State D epartment of

Correctional Services, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

D eborah Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

M orris J. B aller

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Petitioners

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below .........-.... ......... -...... .... -........................... 2

Jurisdiction ...................... .................................................. 2

Questions Presented ................. -........... -----------------...... 2

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved....... 3

Statement of the Case ------- ----- ---------- ------—....... -...... - 5

Beasons for Granting the Writ ......... ................ ...... ..... 9

A. The District Court’s Power to Award Com

plete Belief ........................... ......... ...................... 9

B. Attorney’s Fees ------- ---- ------------- ---------------- 14

Conclusion .................... ..... — .... ......... ........ ...... —- ........ 16

T able oe A uthorities

Cases:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) ....9,15

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974) ...... ..... ............... ......................................... ..... 15,15n

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society,

421 U.S. 240 (1975) ............................. ............. ...3,8,14,15

Boston Chapter, isT A A CP v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017 (1st

Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910 (1975) ..10n, 13,13n

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport Civil Service

Comm’n, 482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1973), aff’g in

relevant part, 354 F. Supp. 778 (D. Conn. 1973) .... . lOn

11

Carter v. Gallagher, 425 F.2d 315, 327 (8th. Cir. 1972)

(en banc), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) ........... . lOn

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972) .......... . lln

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 11 EPD H 10,633 (No.

75-7161 2d Cir. Jan. 19, 1976) ..................................... . l ln

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. O’Neill, 473 F.2d

1029 (3d Cir. 1973) (en banc), aff’g in relevant part,

348 F. Supp. 1084 (EJD. Pa. 1972) ............. ............... 10n

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Sebastian, 480 F.2d

917, reported fully, 6 EPD If 9037 (3d Cir. 1973),

aff’g, 368 F. Supp. 854, reported fully, 5 EPD If 8558

(W.D. Pa. 1972) ............... ..................... ....... ................ H)n

Crockett v. Green, 11 EPD ff 10,781 (7th Cir. 1976) ..10n, 13

Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976 (D.C. Cir. 1975) .... 13n

EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 515 F.2d 301 (6th Cir.

1975) ...................... ....... .................................................. lOn

EEOC v. Local 638 . . . Local 28 of the Sheet Metal

Workers Assoc., 11 EPD 10,740 (No. 75-6079, 2d

Cir. March 8, 1976) __________________ ______ __ _ l i n

Erie Human Relations Comm’n v. Tullio, 493 F.2d 371

(3rd Cir. 1974) .......... ........ ....... ..... ............................ io n

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 44 U.S.L.W.

4356 (No. 74-728, March 24, 1976) ......... .....................9-10

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir. 1974) ....................................................lln , 12,14n

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ..12-13

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454

(1975) ...................... ......... ................ .'_________ ______ 15n

Jones v. New York City Human Resources Adminis

tration, 11 EPD U 10,664 (2d Cir. 1976) ...................... 13n

PAGE

Ill

Local 53, International Association of Heat & Frost

PAGE

I & A Workers v. Yogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th. Cir.

1969) .... ........ ........... ........... ..................... .......... .... ..... . lOn

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ......... 9,12

Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693 (1973) ....... 14

Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 419 U.S. 895 (1974) ............................ ................. l ln

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974) .......... lOn

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ....................... ....................................................... 15

Oburn v. Shapp, 521 F.2d 142 (3rd Cir. 1975) ............. lOn

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 11 EPD Tf 10,728

(4th Cir. 1976) .................... ................ ...................... . 11

Patterson v. Newspaper & Mail Deliverers Union, 514

F.2d 767 (2d Cir. 1975) .......................... ....... ..... ....... lOn

Rios v. Enterprise Association Steamfitters, Local 638,

501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974) ............ ................... .......... lOn

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340 (8th

Cir.), vacated and remanded on other grounds, 46

L.Ed. 2d 29 (1975) ................ ............ ....... ................. . 13n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) .................... ........ ................... ........... 12

United States v. Carpenters, Local 169, 457 F.2d 210

(7th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 851 (1972) .... lln

United States v. IBEW Local 212, 472 F.2d 634 (6th

Cir. 1973) ........................ ................................................ lOn

United States v. Ironworkers, Local 86, 443 F.2d 544

(9th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971),

aff’g, 315 F. Supp. 1202 (W.D. Wash. 1970) ........... lOn

IV

United States v. Masonry Contractors Ass’n of Mem

phis, Inc., 497 F.2d 871 (6th Cir. 1974) ...................... lOn

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ..... ........................................ 12

United States v. N. L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354 (8th

Cir. 1973) ....... ..................................... ....................... .lln , 13

United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers, Local

46, 471 F.2d 408 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 412 U.S. 939

(1973) ...................... ..................... .................................. lOn

Vulcan Society of New York City Fire Dept. v. Civil

Service Comm’n, 490 F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973) ....... lOn, 13n

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. §1981 .......

42 U.S.C. §1983 ____

42 U.S.C. §1988 .......

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k)

Other Authorities:

United States Senate Subcommittee on Labor of the

Committee on Labor, Legislative History of the

PAGE

Equal Employment Opportunity Act o f 1972 (No

vember 1972) ..................... ......................................... . 11

M. Slate, Preferential Relief in Employment Discrimi

nation Cases, 5 Loyola Univ. L. J. 315 (1974) ......... . 12n

3, 5,14,15

3, 5,14,15

....4,14,15

.....5,14,15

I n the

tour! uf tip

October T erm, 1975

No.............

E dward L. K irkland and Nathaniel H ates, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

T he New Y ork S tate D epartment op

Correctional, Services, et al.

PETITION FOB. A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Petitioners, Edward L. Kirkland and Nathaniel Hayes,

individually and on behalf of the class they represent,

respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari issue to re

view the judgment and opinion of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit of August 6,

1975 in this case.1

1 Respondents include, in addition to those named in the caption

the following: Russell Oswald, in his capacity as Commissioner

of the New York State Department of Correctional Services; the

New York State Civil Service Commission; Ersa Poston, in her

capacity as President of the New York State Civil Service Com

mission ; Michael N. Scelsi and Charles P. Stockmeister, each in

his capacity as Civil Service Commissioner; Albert M. Ribeiro

and Henry L. Coons.

2

Opinions Below

1. The opinion of the District Court is reported at

374 F.Supp. 1361 and is in the Appendix, pp. la.-19a.

2. The decree of the District Court is not officially

reported, but is reprinted in 8 EPD ([9675 and is in the

Appendix, pp. 20a~21a.

3. The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at

520 F.2d 420 and is in the Appendix, pp. 22a-41a.

4. The order denying rehearing and the opinions dis

senting from said denial are not officially reported, but

are reprinted in 10 EPD Tf 10,547 and are in the Appen

dix, pp. 42a-56a.

Jurisdiction

The Court of Appeals entered judgment August 6, 1975.

Bequest for rehearing was denied December 10, 1975.

February 19, 1976, Mr. Justice Marshall signed an order

extending time for filing this petition until May 8, 1976.

This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Since 1961 there have been only two blacks and no

Hispanics^ in supervisory positions in the entire New

York State prison system. Substantial uncontradicted

evidence demonstrated that this situation was caused by

unconstitutional racial discrimination. As part of the rem

edy the District Court ordered that one minority be pro

moted to sergeant for every three whites so promoted

3

until the ratio of minority to white sergeants equals the

ratio of minority to white officers—the entry level rank

immediately below sergeant.

Did the District Court have the power to award this

aspect of the relief or was the Court of Appeals correct

in reversing on the ground that it was prohibited by the

United States Constitution, the New York State Consti

tution and the New York Civil Service law?

2. Did the Court of Appeals err in reversing an award

of counsel fees in this case, brought under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981

and 1983, on the ground that such award was forbidden by

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society?

Statutory and Constitutional Provisions Involved

Section 1981, 42 United States Code, provides:

All persons within the judisdietion of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of per

sons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and

shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties,

taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no

other.

Section 1983, 42 United States Code, provides:

Every person who, under color of any statute, or

dinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or

Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any

citizen of the United States or other person within the

jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights,

privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution

4

and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an

action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceed

ing for redress.

Section 1988, 42 United States Code, provides:

The jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters con

ferred on the district courts by the provisions of this

chapter and Title 18, for the protection of all persons

in the United States in their civil rights, and for their

vindication, shall be exercised and enforced in con

formity with the laws of the United States, so far as

such laws are suitable to carry the same into effect;

but in all cases where they are not adapted to the ob

ject, or are deficient in the provisions necessary to

furnish suitable remedies and punish offenses against

law, the common law, as modified and changed by the

constitution and statutes of the State wherein the court

having jurisdiction of such civil or criminal cause is

held, so far as the same is not inconsistent with the

Constitution and laws of the United States, shall be

extended to and govern the said courts in the trial and

disposition of the cause, and, if it is of a criminal

nature, in the infliction of punishment on the party

found guilty.

Section 2000e-5(k), 42 United States Code, provides:

In any action or proceeding under this subchapter

the court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing-

party, other than the Commission or the United States,

a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs, and

the Commission and the United States shall be liable

for costs the same as a private person.

5

Statement of the Case

As of May 1, 1973, of 122 permanent Correction Ser

geants in the New York State Department of Correctional

Service not one was black or Hispanic. Since 1961, there

have been only two blacks and no Hispanies in supervisory

positions in the entire New York State prison system;

there is no evidence that any minorities held supervisory

positions prior to 1961.2

The complaint filed April 10,1973, challenged the legality,

under the Fourteenth Amendment and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981

and 1983, of Civil Service examination 34-944 for promo

tion to Correction Sergeant (Male), administered October

14, 1972, on the ground that it was racially discriminatory

in that it excluded disproportionate numbers of black and

Hispanic candidates and was not job-related. An amended

complaint of June 22, 1973, challenged Sergeant examina

tions administered prior to 1972 on the same ground.

Petitioners introduced substantial, unrebutted evidence

that the gross under-representation of minorities among

supervisors was brought about by the screening-out effects

of the examinations.

For the 1972 examination, complete racial pass-fail sta

tistics showed that whites passed at three times the rate

of blacks and Hispanies, whites scored high enough to

be likely to be appointed at six times the black rate, and

no Hispanies scored high enough to be appointed. While

complete data was not available for earlier examinations,

2 In the Correction Officer series of the New York State Depart

ment of Correctional Services, the entry level position is Correc

tion Officer. Promotions are made to successive supervisory posi

tions of Sergeant, Lieutenant, Captain, Assistant Deputy Super

intendent, Deputy Superintendent and Superintendent on the

basis of a series of written examinations.

6

it was undisputed that, of 995 whites and 46 blacks and

Hispanics who took the 1970 exam and were still em

ployed January 1, 1973, 9.4% of the whites and no mi

norities passed. Prior to 1970, at one correctional facility

25 blacks took the 1968 exam and 10 to 15 blacks took the

1965 exam. Seven black officers testified they took the

Sergeant examination as many as four times and never

scored high enough to be appointed. Six of these officers

had, at time of trial, been serving as provisional Ser

geants for as long as a year, all satisfactorily. Finally,

there was uncontroverted expert testimony that blacks

and Hispanics tend to achieve lower scores than whites

on the type of examinations in issue.

The State respondents3 attempted, unsuccessfully, to

demonstrate that the 1972 examination was job-related.

Petitioners established that the earlier exams were pre

pared by the same process and were similar in content to

the 1972 examination. Respondents put on no evidence

about job-relatedness of earlier examinations.

The District Court found that respondents had engaged

in racial discrimination in that examination 34-944 had

a disproportionate impact upon blacks and Hispanics (3a-

7a) and respondents had not met their burden of estab

lishing its job relatedness (7a-15a). As to past examina

tions, it found that “while there is evidence in the record

of the discriminatory impact of the earlier tests, there

is no evidence as to their job-relatedness” (14a). It en

joined the use of eligibility lists promulgated on the basis

3 Respondents Ribeiro and Coons are provisional Sergeants who

would have been appointed permanent Sergeants on the basis of

their performance on examination 34-944 but for the District

Court’s temporary restraining order entered April 10, 1973. They

applied and were permitted to intervene after the District Court

entered its opinion.

7

of performance on examination 34-944 and ordered prep

aration of a new selection procedure (20a).

The District Court further ordered (a) that permanent

appointments of Correction Sergeants prior to developing

a new selection procedure be in a ratio of one black or

Hispanic for each three whites until “ the combined per

centage of Blacks and Hispanics in the ranks of Correc

tion Sergeants (Male) is equal to the combined percent

age of Blacks and Hispanics in the ranks of Correction

Officers (Male)” (20a); (b) after adoption of a new se

lection procedure the same ratio of appointing one black

for three whites was required to be maintained until the

black-Hispanie sergeant percentage equalled their percent

age among correction officers. (20a-21a)4

The District Court awarded attorneys’ fees to petitioners

on the ground that they were acting to vindicate the

right to equal employment opportunities in the public

sector (17a-19a).

On appeal, a panel of the Court of Appeals affirmed

the provisions of the decree enjoining defendants from

making appointments based upon the results o f examina

tion 34-944 and directing the development of a new se

lection procedure (28a-33a); affirmed that portion of the

decree requiring quota appointments during the interim

period prior to the development of a new selection pro

cedure (38a-39a); but reversed the District Court’s order

with respect to minority goals and implementing ratios

subsequent to development of a new selection procedure.

It is this reversal, denying the power of the district judge

4 The court did not 'specify the time at which the percentage of

minority representation among correction officers was to be ascer

tained for purposes of determining whether the goal for minority

Sergeants had been met. As of May 1, 1973, 395 of 4490 Correc

tion Officers, 8.8%, were black or Hispanic.

8

to award such relief in such circumstances, for which cer

tiorari is sought.

The panel’s reversal of the grant of affirmative relief

following establishment of a new procedure was based on

the grounds that (1) there was insufficient proof of a

“ clearcut pattern of long-continued and egregious racial

discrimination” because (a) complete statistical pass-fail

data was unavailable, (b) petitioners failed to prove that

the earlier exams were not job related, and (c) there was no

claim of bad faith (34a-35a); and (2) a quota might re

sult in minority individuals being given preference over

identifiable non-minorities (persons ranking higher on a

civil service list) which, the panel asserted, “would seem

to be violative” of the United States Constitution, the New

York State Constitution, and the New York Civil Service

Law (35a-38a). The panel failed to consider, or to remand

to the District Court to consider, alternative forms of re

lief to class members who had unconstitutionally and dis-

criminatorily been denied appointment because of per

formance on pre-1972 examinations.

The panel also reversed the award of attorneys’ fees in

reliance on Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness

Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975).

Petitioners petitioned for rehearing, with a suggestion

for rehearing en banc, o f the issue of affirmative relief. The

petition was denied (5-3), Chief Judge Kaufman and Cir

cuit Judges Mansfield and Oakes dissenting (43a-56a).

Judge Mansfield, Judges Oakes and Kaufman concurring,

pointed out that the first ground for reversal, insufficient

proof of past discrimination, was not supported by the

record (49a-51a), and that the second, that a quota would

result in “ identifiable reverse discrimination” , did not dis

tinguish it from all the other cases in which Courts of

Appeals for the Second Circuit and seven other circuits

9

had affirmed the imposition of hiring goals, and that the

panel’s denial of quota relief had the effect of providing

“wholly inadequate relief to those aggrieved” (43a-49a,

51a-55a). In a separate opinion, Chief Judge Kaufman

expressed the view that the court could “ retrace the steps

taken by previous panels . . . only by an en banc . . . or

by a Supreme Court holding that [its] earlier decisions

have been in error” (55a-56a).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

A. The District Court’s Power to Award Complete Relief

The decision below restricts the power of a court of

equity to award effective relief after a finding of racial

discrimination in employment and is thereby in conflict

with the decisions of seven other Courts of Appeals and of

this Court. Such restriction, moreover, denies petitioners

and their class positions they would have held but for re

spondents’ discriminatory testing practices, contrary to

principles asserted by this Court.5

This Court has consistently recognized the power, indeed

the duty, of district courts to fashion relief “which will so

far as possible eliminate the discriminatory effects of the

past as well as bar like discrimination in the future” .

Louisiana v. United States, 380 IT.S. 145, 154 (1965). In

employment cases, this Court has emphasized the necessity

of granting relief which will, to the extent possible, place

victims of racial discrimination in the position they would

have been in but for the discrimination. Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418-419 (1975); Franks v. Bow-

5 The District Court defined plaintiffs’ class to include all blacks

and Hispanics who had taken examination 34-944 and either failed

or scored too low to be appointed from the resulting eligible list

(16a).

10

man Transportation Co., 44 U.S.L.W. 4356 (No. 74-728,

March 24, 1976).

Relief from class-wide discriminatory exclusion from

jobs, at entry and higher levels, in public and private em

ployment, has frequently included numerical or percentage

goals or quotas, utilizing hiring or promotional ratios to

implement the goals. Courts of appeals for seven other

circuits, as well as the court below in decisions prior to

the instant one, have uniformly upheld the power of dis

trict courts to grant such relief.6

6 Boston Chapter, NAACP v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017 (1st Cir.

1974) , cert, denied, 42 TJ.S. 910 (1975) ; United States v. Wood,

Wire <& Metal Lathers, Local 46, 471 F.2d 408 (2d Cir.), cert,

denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973) ; Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridge

port Civil Service Comm’n, 482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1973), aff’g

in relevant part, 354 F. Supp. 778 (D. Conn. 1973) ; Vulcan

Society of New York City Fire Dept. v. Civil Service Comm’n,

490 F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973); Bios v. Enterprise Association

Steamfitters, Local 638, 501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974) ; Patterson

v. Newspaper & Mail Deliverers Union, 514 F.2d 767 (2d Cir.

1975) (approving consent decree) ; Commonwealth of Pennsyl

vania v. Sebastian, 480 F.2d 917, reported fully, 6 [CCH] EPD

1(9037 (3rd Cir. 1973), aff’g, 368 F. Supp. 854, reported fully,

5 EPD ([8558 (W.D. Pa. 1972) ; Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

v. O’Neill, 473 F.2d 1029 (3rd Cir. 1973) (en banc), aff’g in

relevant part, 348 F. Supp. 1084 (E.D. Pa. 1972) ; Erie Iluman

Relations Comm’n v. Tullio, 493 F.2d 371 (3rd Cir. 1974); Oburn

v. Shapp, 521 F.2d 142 (3rd Cir. 1975); Local 53, International

Association of Heat & Frost I & A Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

1047 (5th Cir. 1969) ; NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir.

1974); United States v. IBEW Local 212, 472 F.2d 634 (6th Cir.

1973) ; United States v. Masonry Contractors Ass’n of Memphis,

Inc., 497 F.2d 871 (6th. Cir. 1974) ; EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co.,

515 F.2d 301 (6th Cir. 1975) ; Crockett v. Green, 11 EPD 1(10,781

(7th Cir. 1976) ; Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315, 327 (8th

Cir.) (en bane), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) ; United States

v. Ironworkers, Local 86, 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir. 1971), cert,

denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971), aff’g, 315 F. Supp. 1 2 0 2 '(W.D.

Wash. 1970).

11

Courts of appeals for four circuits have reversed a dis

trict court’s failure to order such relief.7 With the ex

ception of two recent Second Circuit decisions which re

lied upon the panel’s decision in the instant case,8 the

only appellate decision to have reversed a grant of quota

relief is Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 11 EPD

1110,728 (4th Cir. 1976), where the court, recognizing the

appropriateness of snch relief in certain circumstances,

found that under the facts of that case it was not necessary.

The legislative history of the 1972 amendments to Title

VII demonstrates that such relief accords with the intent

of Congress. In 1972, two amendments were proposed to

prohibit the type of remedy which the court below struck

down. Both were defeated. Floor managers of both parties

explained that they opposed the amendments because they

would prevent District Courts from providing adequate

remedies for past discriminatory practices. United States

Senate, Subcommittee on Labor of the Committee of Labor

and Public Welfare, Legislative History of the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Act of 1972, November 1972, pp.

1017, 1038-1075, 1681, 1714-1717.

In analogous contexts, this Court has upheld the power

of district courts to shape remedies for past constitutional

7 Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972) ; Morrow V.

Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.) (en banc), cert, denied, 419 U.S.

895 (1974) ; Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398,

418-20 (5th Cir. 1974), reversed on other grounds, 44 U.S.L.W.

4356 (No. 74-728 March 24, 1976) ; United States v. Carpenters,

Local 169, 457 F.2d 210 (7th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 851

(1972) ; United States v. N. L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir.

1973).

8 Chance v. Board of Examiners, 11 EPD 1)10,633 (No. 75-7161

Jan. 19, 1976), petition for rehearing filed Feb. 2, 1976) ; EEOC

v. Local 638 . . . Local 28 of the Sheet Metal Workers Assoc.,

11 EPD 1)10,740 (No. 75-6079 March 8, 1976), petition for re

hearing filed, April 12, 1976.

12

violations by taking into account black-white ratios. Swann

v. Charlotte-M ecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971); United States v. Montgomery County Board of

Education, 395 U.S. 225 (1969).

The element that makes such affirmative provisions both

lawful and necessary is proof of prior discrimination or its

continuing effects. Louisiana v. United States, supra; cf.

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra. And the

appropriateness in this particular case is manifest, for as

Judge Mansfield pointed out, rejecting goals denies “non

white correction officers the long overdue promotions to

which they were entitled [and] . . . by requiring them to

compete afresh with late comers once a non-discriminatory

test is devised . . . postpones their promotions even

further” (51a). Yet, the alternative remedy which would

“ adhere most closely to the merit principle, would be to

void and recall all past promotions made on the basis of

the non-validated tests. . . . [But] such relief . . . would be

extremely harsh. . . .” (52). The district judge took a mid

dle ground, well within the powers of a court of equity.9

One ground given by the panel for reversal was the

“paucity of proof” of past discrimination (35a.). But this

argument is not supported by the record. Substantial un

contradicted evidence demonstrated the discriminatory ef

fects of respondents’ past testing practices. While com

plete statistical pass-fail evidence was not introduced, be

cause it was not available, the argument that such evidence

is necessary to a finding of discriminatory impact has been

rejected, expressly or by implication, by this Court and

several Courts of Appeals. Griggs v. Duke Power Com-

9 See M. Slate, Preferential Belief in Employment Discrimina

tion Cases, 5 Loyola Univ. L. J. 315 (1974) for a comprehensive

rationale of the law of this subject.

13

pany, 401 U.S. 424, 430 and n. 6 (1971), Courts of Appeals

for the First, Second, Eighth and District of Columbia

Circuits have found discriminatory impact in the absence

of complete pass-fail data.10

The panel’s second ground for denying that there is

equitable power to grant quota relief upon a finding of

racial discrimination was that the non-minority officers

over whom the minority officers would be preferred for

promotion were identifiable. However the identifiability

vel non of those whose expectations might be diminished

has never been a criterion for determining the appropriate

ness of affirmative relief (54a). In virtually all of the cases

in which preferences have been ordered, the identity of

those who possessed expectations deriving in part from

the continuing effects of past discrimination was known.

See, e.g., Boston Chapter, NAACP v. Beecher, 504 F.2d

1017, 1026-1027 (1st Cir. 1974). Nor has such relief been

confined to entry level jobs. See United States v. N. L.

Industries, 479 F.2d 354, 377 (8th Cir. 1973); Crockett v.

Green, 11 EPD ([10,781 (7th Cir. 1976). Indeed the panel

decision recognized existence of the power to appoint ac

cording to quotas until the time when new selection pro

cedures would be developed, but denied its existence there

after, when the use of such power would be most meaning

ful.

In sum, the decision of the court below creates a conflict

with decisions of other circuits concerning the equitable

10 Boston Chapter, NAACP v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017, 1020-1021

(1st Cir. 1974) ; Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission, 490

F.2d 387, 393 (2d Cir. 1973) ; Jones v. New York City Human

Resources Administration, 11 EPD ({10,664 (2d Cir. 1976) ; Rogers

v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340', 1348-49 (8th Cir.)

vacated and remanded on other grounds, 46 L.Ed. 2d 29 (1975) ;

Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F.2d 976, 982-983 (D.C. Cir. 1975).

14

power of district judges to award meaningful relief. This

Court, we respectfully submit, should resolve the conflict.11

B. Attorneys’ Fees

This Court has not yet decided whether a district court

has the power to award attorneys’ fees to prevailing

plaintiffs in cases of racial discrimination in employment

brought under 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983. While there is

language in Alyesha Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness

Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975) to support the decision of the

Court below, see especially id. at 270 n. 46, petitioners

respectfully submit that the rationale underlying Alyesha,

considered in conjunction with 42 U.S.C. §1988 and 42

TT.S.C. §20Q0e-5(k), requires a contrary result.

In Alyesha, a case involving the enforcement of certain

laws for the protection of the environment, this Court held

that in the absence of express statutory authorization the

courts could not, except in limited classes of cases, award

attorneys’ fees. But there is express statutory authoriza

tion, 42 U.S.C. §1988, which, we submit, warrants award

of counsel fees in this case. Sections 1981 and 1983 do not

specify any of the remedies available for the rights they

create. Rather, Section 1988 instructs the federal courts in

civil rights cases to exercise their jurisdiction in conformity

with the laws of the United States and, indeed, if they are

deficient, state laws, to provide remedies which will most

fully effectuate the substantive rights at issue. Moor v.

County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693, 702-705 (1973).

11 Subsequent to the denial of rehearing in the instant ease, this

Court decided Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra. While

the issue resolved in Franks, the propriety of granting retroactive

seniority to discriminatees, was not raised in the court below, a

remand to the Court of Appeals for reconsideration in the light

of Franks might afford complete^ relief to those members of plain

tiffs’ class who were denied promotion to Sergeant on the basis

of their performance on pre-1972 examinations.

15

Congress enacted Title VII of the Civil Eights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. §§20Q0e et seq. for the purpose of eradicat

ing discriminatory employment practices; it gave a signif

icant role to private litigants in the enforcement process.

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 44-45 (1974).

In Section 7Q6(k) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k),

Congress provided for the award of attorneys’ fees to

successful plaintiffs, and this Court has recognized the

importance of implementing this provision to effectuate

the purpose of Title VII. Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

405, 415 (1975).

Thus, unlike the situation presented to the Court in

Alyeska, where Congress had not seen fit to authorize the

award of attorneys’ fees in environmental litigation, there

is, in section 706 (k) of Title VII, a clear expression of

Congressional intent to authorize federal courts to award

attorney’s fees to vindicate the national policy of eliminat

ing racial discrimination in employment, a policy advanced

equally through suits brought pursuant to Sections 1981

and 1983 and Title VII.12

Accordingly, by assimilating §706 (k) of Title VII to

§§1981 and 1983 as directed by §1988, the district court in

the instant case was authorized to award attorneys’ fees to

petitioner, and the reversal of said award by the court

below was contrary to the principle enunciated by this Court

in Alyeska, as well as to the rule expressed in Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968).

Certiorari should be granted also, we submit, to resolve

this important ambiguity resulting from Alyeska.

12 Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 47 and n .7 ;

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454 (1975).

16

CONCLUSION

The Court should grant a Writ of Certiorari to review

the judgment and opinion of the Court of Appeals.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

D eborah Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

M orris J. B aller

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Petitioners

May 1976

A P P E N D I X

la

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe the Southern District op New Y ork

73 Civ. 1548

Edward L. Kirkland, et al., Plaintiffs,

v.

New York State Department op

Correctional Services, et al., Defendants.

Filed: April 2, 1974

Opinion o f District Court

Jack Greenberg, Jeffry A. Mintz,

Morris J. Bailer, Deborah M. Greenberg,

New York City, for plaintiffs.

Louis J. Lefkowitz, A tty. Gen., of the

State of New York, New York City, for

defendants; Judith A. Gordon, Asst.

Atty. Gen., Stanley L. Kantor, Deputy

Asst. Atty. Gen., of counsel.

OPINION

LASKER, District Judge.

This suit is another in an evcr-exte;...!-

ing series of challenges to civil service

examinations. Plaintiffs, who are

Correction Officers,1 provisionally ap

pointed to the rank of Correction Ser

geant (Male), contend that the test for

promotion and permanent appointment

to that position discriminated against

them on the basis of race. They seek to

represent all Black and Hispanic Correc-

1. Originally, there was a lliinl named plain

tiff, the Brotherhood of New York State

Correction Officers, Inc. However, this

plaintiff withdrew at the commencement of

tlie trial.

2. Defendants urge us to apply the doctrine

of primary jnrisdielion and defer the case to

tiie Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion oil tiie theory that by extending Title

V II to cover states and municipalities Con

gress intended to oblige persons seeking re

dress against governmental discrimination in

employment to resort in the first instance to

tiie EEOC. This conleuiion has been re

soundingly rejected in cases involving suits

against private employers under Id H.S.C. §

HIM. Macklili v. Specter Knight Systems,

Inc.. Hid li.S.App.D.C. (Ill, ITS Ro,|

996-997 ui>7;» ; Brady v. Bristol-Meyers,

turn Officers and provisional Correction

Sergeants who failed the examination,

who passed it but ranked too low to be

appointed or who were deterred by the

appointment system from seeking pro

motion. Defendants are the New York

State Department of Correctional Serv

ices, its Commissioner, and the New

York State Civil Service Commission

and its Commissioners.

The action is brought under the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution and under the Civil

Rights Act (42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and

1983) and its jurisdictional counterpart

(28 U.S.C. §§ 1343(3). and (4 )) . Plain

tiffs make no claim under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000e to 2000O.-17), despite the avail

ability, by recent amendment, of reme

dies under it against states and munici

palities (id. at § 2000e(a)).2

Inc., 159 E.L'd (121, (1211-1124 (.8th Oil-. 1972) ;

Caldwell v. National J Growing Co., 448 F.2d

1041 (fit11 C ir.). cert. denied, 404 IT.S. 098,

92 S.Ct. 500, 80 L.10d.2d 551 (1971) ; Young

v. International Telephone & Telegraph Co.,

488 F.2d 757, 708 (8rd Cir. 19 7 1 ); Sanders

v. Dobbs House. I nr., 481 F.2d 1097, 1.100-

1101 (5th Cir. 1970), rort. denied, 401 U.S.

94.X, 91 S.Ct. 985, 28 L.Ed.2d 281 (1971).

Furthermore, rases in this Circuit: involving

suits which, like the instant case, were

brought under § 1988 hold that the amend

ment. to Title VII was not intended to fore

close recourse to the earlier Civil Rights

Act. Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Com

mission, 490 F.2d 8X7, at. 890, n. I (2d Cir.,

1978) ; Bridgeport (Junrdians, lncM v.

Bridgeport Civil Service Commission, 4X2

F.2d .1888, 1884, n. 1 (2d Cir. 1978).

2a Opinion of District Court

In spring, 1972, the 1970 eligible list

for Sergeant appointments was exhaust

ed. To fill needed positions pending es

tablishment of a new list, the Depart

ment of Corrections appointed provision

al Correction Sergeants, in August,

1972, to hold their posts until permanent

appointments could be made. Both

named plaintiffs were appointed at that

time.

Upon request of the Department of

Corrections, the Civil Service Commis

sion prepared a promotional examination

which was administered on October 14,

1972. That examination, 34-944, was

taken and failed by plaintiffs and is the

subject of this action.

34-944 was taken by 1,383 persons,3

including 1,264 whites, 103 Blacks and

16 Hispanics. The candidates examina

tions were graded and the passing grade

was established at 70%. After adjust

ment for veteran’s preference and seni

ority, those who passed were ranked by

grade and an eligible list was promulgat

ed on March 15, 1973. On April 10,

1973, this suit was filed and a temporary

restraining order entered preventing de

fendants from making appointments

from the list and from terminating the

provisional appointments of plaintiffs or

members of the class. By modification

and stipulation, the restraining order

was extended to maintain the status quo

until a decision on the merits.

The ground rules for cases such

as this have been thoroughly elucidated

by recent decisions of the Court of Ap

peals for this Circuit. We note in par

ticular Vulcan Society of the New York

City Fire Department, Inc. v. Civil Serv

ice Commission ( “ Vulcan"), 490 F.2d

387 (2d Cir. 1973), a ff ’g, 360 F.

Supp. 1205 (S.D.N.Y.1973) ; Bridge

port Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport Civ

3. The total candidate poo! was approximately

1,441. However, for reasons not apparent

from the record, the computer display pro

vided by defendants to deseribe eandidate

performanee (P X -1 2 ) indieates the perform

ance of only .1,883 candidates. Since, both

parties have based their calculations on that

figure, we will do likewise.

il Service Commission ( “ Guardians” ),

482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir.), a ff ’g in part

and rev’g in part, 354 F.Supp. 778 (D.

Conn.1973), and Chance v. Board of Ex

aminers ( “ Chance"), 458 F.2d 1167 (2d

Cir. 1972), a ff ’g, 330 F.Supp. 203 (S.D.

N.Y.1971). To summarize the approach

adopted by the eases, plaintiffs must

first establish a prima facie case show

ing that the examination has had “ a ra

cially disproportionate impact.” Vulcan,

490 F.2d at 391; Castro v. Beecher

( “Castro"), 459 F.2d 725, 732 (1st Cir.

1972). If they succeed, it then becomes

defendants' burden to justify the exami

nation’s use despite its differential im

pact by proving that it is job-related

( Vulcan, 490 F.2d at .391) and that any

disparity of performance results solely

from variance in qualification and not

from race (Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424, 430-431, 91 S.Ct. 849, 28

L.Ed.2d 158 (1971); Chance, 330 F.

Supp. at 214). Discharging this burden

would entitle defendants to judgment;

failure would, of course, require the

court to take the third step of determin

ing what remedy would be appropriate.

As is typical in cases of this

type, plaintiffs do not allege that de

fendants have intentionally discriminat

ed against their class. Such an allega

tion is not a necessary part of their

case. Chance, 458 F.2d at 1175-1176.

As the Supreme Court stated in

Griggs: 1

“ [G jood intent or absence of discrimi

natory intent does not redeem employ

ment procedures or testing mecha

nisms that operate as ‘built-in head

winds’ for minority groups and are

unrelated to measuring job capability.”

401 U.S. at 432, 91 S.Ct. at 854.

However, the fact that the alleged dis

crimination is not claimed to be deliber-

4. (Iritifis arose under Title V II of (lie Civil

Bights Art of 1})(J4: however, tin1 some ap

proach to employment iliserimination eases

has generally been followed in § 1083 eases

ns in Title VII raises. V it lam. 400 F.2<1 at

304, 11. 0 ; Castro, -150 F .2(1 at 733.

Opinion of District Court 3a

ate modifies the burden placed on the

state to justify its actions. Intentional

racial discrimination would require the

state to demonstrate a compelling neces

sity for its selection methods. Cf. Lov

ing v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 87 S.Ct.

1817, 18 L.Ed.2d 1010 (19G7); Tick Wo

v. Hopkins. 118 U.S. 356, 0 S.Ct. 1064.

30 L.Ed. 220 (1886). However, “ the Su

preme Court has yet to apply that strin

gent test to a case such as this, in which

the allegedly unconstitutional action un

intentionally resulted in discriminatory

effects.” Chance, 458 F.2d at 1177.

Agonizing over whether the state can

discharge its constitutional obligations

merely by suggesting a rational basis

for the examination's use or whether it

must satisfy a more demanding stand

ard, short of the compelling interest

test, is unnecessary. Tin; guidelines

have been so refined by the cases that

no ambiguity obscures the road to deter

mination regardless of the difficulties

of classification which may remain to

plague the theorists. Guardians, 482 F.

2d at 1337. The decisions impose on the

state "a heavy burden of justifying its

contested examinations by at least dem

onstrating that they were job-related.”

Chance, 458 F.2d at 1176; see also

Guardians, 482 F.2d at 1337. This

“ heavy burden” is discharged if the

state "come[s] forward with convincing

facts establishing a fit between the qual

ification and the job.” Vulcan, 490 F.2d

at 393, quoting Castro, 459 F.2d at 732.

Once the state proves its case to that ex

tent, it need not establish, as would be

required under the compelling interest

approach, that no alternate means of

selection are open to it. Castro, 459 F.

2d at 733; see also Vulcan, 490 F.2d at

393.

However clearly the issues are deline

ated by well-established precedent, noth

ing can make easy the task of deciding a

case such as this. The competing inter

ests are vital to the named parties, to

other individuals who may be affected

by the outcome and to the public at

large. Plaintiffs strive to insure for

I hemselves and the minorities they seek

to represent the fair treatment in the

public employment sphere which the

Constitution guarantees. Their efforts

bring them into conflict with those indi

viduals who passed the challenged exami

nation and have a vested interest in se

curing the promotions which are right

fully theirs if the examination is upheld.

For both groups, the outcome is critical

since it affects their ability to earn a

living by advancing in the profession of

their choice. Last and perhaps most im

portant is the public's stake in establish

ing and maintaining a system of prison

administration which is both competent

and representative of the population.

As members of the public, we include, of

course, the inmates o f the prison system

who, more than anyone else in the com

munity, are directly affected by the

quality of correctional supervision. The

delicacy of Hie decision is further com

pounded by the potential for heightened

tension which attends any direct conflict

along racial and cultural lines.

Bearing these factors in mind, we pro

ceed, with caution but without more ado,

to a consideration of plaintiffs’ prima

facie case.

I. DISPROPORTIONATE IMPACT.

Plaintiffs rest their case on the fol

lowing uncontested statistics. The fig

ures computed by defendants indicate

that White candidates passed 34-944 at

a rate of 30.9%, while only 7.7% of

Black candidates and 12.5%, of Hispanic

candidates achieved a passing score.

(Transcript at 500). That is, Whites

passed at a .rate approximately four

times that of Blacks and 2.5 times that

of Ilispanics. Defendants concede the

statistical significance of these differ

ences. (Post-trial Memorandum at 1-4.)

Plaintiffs’ evidence reveals an even

more startling disparity among those

who ranked high enough to be appoint

ed. The Department of Corrrections in

tends to appoint a maximum of 147 per

4a Opinion of District Court

sons from the present eligible list.5 A

computer display of the results of 34-

944 (PX -12) reveals that, o f 159 per

sons who scored 57 or above (a group

large enough to satisfy the Department's

projected needs), 157 were White, two

were Black and none was Hispanic.

Thus, 12.5% of the Whites who took

34-944 are likely to be appointed, while

only 1.9% of Black candidates and no

Hispanics have a chance at appointment.

These results would lead to the appoint

ment of Whites at 6.5 times the rate of

Blacks and would bar completely the ap

pointment of Hispanics.

The statistical significance of these

figures is established beyond dispute by

the earlier cases. In Chance, Guardians

and Vulcan, the impact was less drasti

cally disproportionate among the races.

In Chance, the passing rate for Whites

was 1.5 times that of Blacks and His

panics (330 F.Supp. at 210); in Guardi

ans, Whites passed at 3.5 times the rate

for Blacks and Hispanics (354 F.Supp.

at 784); and in Vulcan, Whites scored

high enough to have a chance at ap

pointment at 2.8 times the rate for

Blacks and Hispanics (360 F.Supp. at

1269).

Defendants do not challenge the accu

racy of plaintiffs’ figures (for which

they are the source) nor do they deny

the statistical significance of the differ

ential impact indicated by them. They

contend, however, that the approach tak

en by plaintiffs, that is, consideration of

the statistics as to the statewide impact

of the entire exam, does not accurately

reflect the performance of the groups in

relation to each other. They urge us,

rather, to base our determination of ra

cial impact on the candidates’ perform

ances facility by facility rather than

throughout the state. They contend

that otherwise it is impossible to deter-

5. The Department of Corrections appointed

ST persons from the eligible list lmsed on

34-944 in April. 1973. f i 'X -2 . answer to

Interrogatory No. 39.) On May 29, 1973,

the Department indicated that it intends (o

make another 4 0 -60 appointments from the

list within roughly two years from that date.

(P X -2 , answer to Interrogatory No. 40.)

mine whether minority candidates are

succeeding less well as a group because

of their racial and cultural backgrounds

or because they are located at facilities

which, for reasons unspecified, prepare

their officers less well for the promo

tional exam. In fact, the great majority

of minority candidates are located at Os

sining (82 Blacks out of a total o f 104, 9

Hispanics out of a total of 16) with the

second largest concentration of Blacks at

Greenhaven (8). (PX-12, codes 1007

and 1008.) Defendants argue that if

both Whites and minority candidates at

Ossining perform less well than persons

— White, Black or Hispanic— employed

at other facilities, then 34-944 has not

been shown to differentiate on the basis

of race. Second, defendants contend

that, since 34-944 is composed of five

subtests, comparative performance on

each subtest should be determinative

rather than performance on the test as a

whole. I f these approaches are adopted,

they claim, the three groups of candi

dates will be shown not to have per

formed sufficiently differently to make

out a prima facie case of disproportion

ate impact.

To support their argument that the

results of 34-944 are relevant only if

separated by facility, defendants rely on

an analysis of the computer display of

examination results (PX-12) drawn up"

by Kenneth Siegel, the Associate Per

sonnel Examiner who was responsible

for the preparation of 34-944. He ana

lyzed the performances of the groups in

terms of mean scores on the total exam

and on each of the five subtests at Os

sining, Green Haven, all the other facili

ties and all the facilities taken together

(D X-D D ). The reason for selecting Os

sining and Green Haven for special at

tention was the concentration of minori

ty candidates at those facilities. Sie-

Thus, a maximum of 147 persons will ho ap

pointed through May of 1975. No appoint

ments are likely after that 'late, since an

other promotional extun will he given in

1974 (I 'X -4 2 . p. 4., Ttli par.) ami the eligi

ble list from 34 -944 will therefore expire in

1974 or early 1975.

Opinion of District Court •5a

gei's written analysis (D X-D D ) does

not indicate passing rates, but only

mean scores. However, Siegel testified

that the difference in passing rates be

tween Whites and Blacks at Green Ha

ven (Transcript at 511) and all other fa

cilities except Ossining is not statistical

ly significant (Transcript at 509, 515).

Based on Siegel’s testimony, defendants

argue that as a result plaintiffs' prima

facie case fails with respect to all facili

ties except Ossining.

The principal obstacle to accepting de

fendants' analysis is that it is premised

on assumptions which are factually erro

neous. Their own statistics bely their

theory. Siegel’s analysis (D X-D D ) of

the computer display (PX -12) reveals

not only that the mean score for Whites

state-wide (48.9) is superior to that of

Blacks (43.2) and Ilispanics (44.2), but

also that the mean scores at Ossining,

Green Haven and other facilities consid

ered separately reflect the same pattern.

Whites at Ossining achieved a mean

score of 47.32, compared with 42.96 for

Blacks and 41.56 for Ilispanics. The

disparity at Ossining is virtually identi

cal to that derived from a comparison of

statewide figures for Whites and Blacks

(48.9 to 43.2) and is greater than the

state-wide difference between Whites

and Hispanics (48.9 to 44.2). This ef

fectively refutes defendants’ theory that

minority candidates generally performed

less well than Whites solely because they

were concentrated at Ossining where

candidates as a whole did less well.

The range at Green Haven is almost

as striking and indicates again a

greater variance than is found state

wide between Whites and Blacks and an

almost identical disparity as that found

state-wide between Whites and Hispan

ics: Whites, 48.68; Blacks 42.00; His

panics, 44.00. A comparison of results

at facilities other than Ossining and

Green Haven bears out the trend:

Whites, 49.00; Blacks, 45.21; Hispan

ics, 48.17. It is true that Hispanics at

these facilities fared better than at Os

sining and Green Haven and their

scores more closely approximate the

performance of Whites. However, the

importance of this discovery is some

what discounted by the small size of

the sample (6 Hispanic candidates)

which 'decreases the possibility of sta

tistical accuracy (Transcript at 936-37).

Furthermore, Siegel’s analysis indicates

that the standard deviation in mean

scores between Whites and Blacks was

statistically significant at Ossining,

Green Haven and all other facilities as

well as state-wide, and the same is true

of Whites and Hispanics at Ossining

where the largest concentration of His

panics is found. (D X-D D .)

An analysis of passing rates, which is

more appropriate since it is the passing

score which determines a candidate’s eli

gibility for appointment, is even more

illuminating. Siegel testified that there

was a significant difference between the

passing rates- of Whites and Blacks at

Ossining (Transcript at 509), but that

no such difference existed between

Whites and Blacks at Green Haven and

facilities other than Ossining and Green

Haven and none between Whites and

Hispanics at Ossining, or other facili

ties. (Transcript at 509-515.) He

did not compare the passing rates of

Whites and Hispanics at Green Haven

because there was only one Hispanic

candidate at that facility. {Transcript

at 511.) Nor did he testify as" to the

difference between the passing rates

of Whites and Hispanics at facilities

other than Ossining and Green Haven.

Siegel is correct that the disparity in

passing rates between Whites and

Blacks at Ossining is significant:

Whites passed at a rate of 23.5% and

Blacks at a rate of 4.9%. (PX-33.)

However, his testimony as to Blacks at

Green Haven and at other facilities and

as to Hispanics at Ossining flies in the

face of the figures in evidence. To the

contrary, comparison of the groupings

mentioned above indicates in each in

stance a significant disparity between

the passing rate of White and minority

candidates. Whites at Green Haven

passed at a rate of 31.6%, while Blacks

and Hispanics achieved rates of only 12.-

6a Opinion of District Court

3% and 0 % s respectively. 30.7% of

Whites at facilities other than Ossining

and Green Haven 7 passed 34-944, while

only 14.3% of Blacks passed. Although

Hispanics at facilities other than Ossin

ing and Green Haven passed at a higher

rate than Whites (33.3% compared to

30.7%), the reliability of this computa

tion is put in doubt by the smallness of

the sample. Hispanics at Ossining, on

the other hand, passed at a rate of 0%

compared to a White passing rate of 23.-

5%. Accordingly, contrary to Siegel’s

conclusion, the disparity between White

and minority candidates was significant

■with regard to Blacks at Ossining,

Green Haven and all other facilities, as

well as state-wide, and was significant

with regard to Hispanics at Ossining,

where the largest number of Hispanics

are located.

These computations destroy the

factual premise of defendants’ argument

that minority performance reflects the

facilities in which they concentrated

rather than their minority characteris

tics. We would in any event be forced

to reject defendants’ theory as a matter

of law, even if it could be factually sub

stantiated. Attempts to correlate racial

performance to such non-racial charac

teristics as quality of schooling or edu

cational and cultural deprivation have

been rejected as irrelevant to rebut a

statistical prima facie case. As the dis

trict court opinion in Guardians stated:

“ More fundamentally, this data [as to

quality of schooling] fails to remove

the prima facie showing of discrimi

nation because it does not alter but

only tries to explain the difference in

6. inn.sniuvh ns tlion* was only one Hispanic

candidate from Crecn Ilaven, the importance

of tins comparison should not he exaggerat

ed.

7. The figures for White, Black and Hispanic

passing rates at facilities other than Ossin

ing and tlreen Haven arc not in the record,

lmt call lie readily computed from those

which are in evidence (see I’X -3 3 ) . The

number of Whites at “other facilities'’ is

d0(10 (12(i4, the total of W hite candidates,

minus 1!)5, which is tiie sum of Wiiite candi-

passing rates.” 354 F.Supp. at 785;

see also Vulcan, 360 F.Supp. at 1272.

Cf. Castro, supra.

The controlling decisions clearly posit

that, in order to shift to defendants the

burden of showing that performance on

the examination correlates to perform

ance on the job, plaintiffs are required

to do no more than demonstrate that mi

nority candidates as a whole fared sig

nificantly less well than White candi

dates, regardless of possible explanations

for their poorer performance. To quote

Guardians once more;

“ The point is that a discriminatory

test result cannot be rebutted by

showing that other factors led to the

racial or ethnic classification. The

classification itself is sufficient to re

quire some adequate justification for

the test.” Id., 354 F.Supp. at 786.

Finally, we fail to understand the rel

evance of defendants’ attack on plain

tiffs ’ prima facie case. Defendants ap

pear to concede that, at the very least,

Blacks at Ossining who failed 34-944

have established their right to challenge

its job relatedness. (Post-trial Memo

randum at I—11.) This group consti

tutes two-thirds of the proposed plain

tiff class (77 out of 117 Blacks and His

panics combined), but if even a far

smaller number had succeeded in prov

ing disportionate impact detrimental to

themselves, defendants would be obliged,

as they themselves concede, to prove job

relatedness.

We turn to defendants’ second

challenge to plaintiffs’ case. Siegel’s

analysis of the computer display indi

cates that although there is a statistical-

(IjiIcs at Ossining, 81, and Green Haven,

1141. The number of Whites sit “other fa

cilities" who passed is 328 (883 minus 55,

the sum of 19 at. Ossining and 30 at Green

Ilaven). Accordingly, the passing rate is

30 .7% . Slacks at “ other facilities” number

14 (103 minus 89, which is 81 at Ossining

and 8 at Green Ilaven). Two Macks at

“other facilities" passed (7 minus 5 ) . As a

result, the passing rate is 14 .3 % . There

were six Hispanics at “other facilities” (.10

minus 10, nine at Ossining, one at Green

Ilaven). Two passed and the rate is 33.3%.

Opinion of District Court 7a

ly significant difference in the total

mean scores of Whites and Blacks and

Whites and Hispanics state-wide and at

Ossining, and, as to Blacks, at Green

Haven and facilities other than Ossining

and Green Haven, not every subtest

indicates such a disparity. (I)X-DD .)

It is unnecessary to detail the permuta

tions sub-test by sub-test and facility

by facility, since the suggested approach

itself is invalid as a matter of law.

The cases indicate that a showing that

the overall examination procedure pro

duced disparate results cannot be re

butted by fragmenting the process and

demonstrating that separately the parts

did not differentiate along racial or cul

tural lines. In Chance, for example, the

fact that minority candidates had a

higher passing rate than White candi

dates on seven out of fifty examinations

did not vitiate plaintiffs’ proof that the

series of examinations as a whole dis

criminated against them and their class.

330 F.Supp. at 211; see. also Guardians,

354 F.Supp. at 786. In Vulcan, the very

question whether a single examination

procedure can properly be subdivided

and the parts considered separately, was

raised and Judge Weinfeld rejected the

proposition:

“ Moreover, the examination may not

be truncated; whether or not it has

an adverse discriminatory impact

upon minority groups should be con

sidered in terms of the total examina

tion procedure. Here there can be no

doubt, whatever the relative impact of

component parts, that in end result

there was a significant and substantial

discriminatory impact upon minori

ties. . . . ” 360 F.Supp. at 1272.

Any other approach conflicts with

the dictates of common sense. Achiev

ing at least a passing score on the ex

amination in its entirety determines eli

gibility for appointment, regardless of

performance on individual sub-tests.

Accordingly, plaintiffs’ case stands or

falls on comparative passing rates alone.

Thus, in law and in logic, we find de

fendants’ approach unwarranted.

Rejection of defendants’ dual at

tack on plaintiffs’ showing of differen

tial impact leaves no doubt that plain

tiffs ’ prima facie case has been amply

established. - Accordingly, the burden of

proof swings to defendants to demon

strate that 34-944 is job-related. We

turn to a consideration of that question.

II. JOB-RELATEDNESS.

"Validation” is the term of art

designating the process of determin

ing the job-relatedness of a selection

procedure. Cases and official guidelines

recognize three validation methods: cri

terion-related validation, construct vali

dation and content validation. See, e. p.,

Vulcan, 490 F.2d at 394-396; Guardi

ans, 482 F.2d at 1337-1338 and 354 F.

Supp. at 788-789; Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission Testing and

Selecting Employees Guidelines ( “ EEOC

Guidelines” ), 29 C.F.R. § 1607, at §

1607.5(a); American Psychological As

sociation Standards for Educational &

Psychological Tests and Manuals ( “ APA

Standards” ) (PX -26) at 12-13.

A. Criterion— Related Validation.

Decisions in this Circuit and the

EEOC guidelines agree that criterion-re

lated or empirical validation is prefera

ble to other validation methods. Guardi

ans, 482 F.2d at 1337 and 354 F.Supp. at

788; Vulcan, 360 F.Supp. at 1273;

EEOC Guidelines at § 1607.5(a). In

Vulcan, Judge Weinfeld defined the two

methods which are subsumed under the

criterion-related rubric:

“ Predictive validation consists of a

comparison between the examination

scores and the subsequent job per

formance of those applicants who are

hired. If there is a sufficient correla

tion between test scores and job per

formance, the examination is consid

ered to be a valid or job-related one.

Concurrent validation requires the

administration of the examination to

a group of current employees and a

comparison between their relative

scores and relative performance on the

job.” 360 F.Supp. at 1273.

8a Opinion of District Court

The methodology which unites the two

types of criterion-related validity re

quires two fundamental .steps:

“ Criteria must be identified which in

dicate successful job performance.

Test scores are then matched with job

performance ratings for the selected

criteria.” Guardians, 482 F.2d at

1337.

The EEOC’s minimum standards for

validation (EEOC Guidelines at § 1607.-

5) require an employer to undertake cri

terion validation if it is feasible. They

demand “ empirical evidence in support

of a test’s validity . . . based on

studies employing generally accepted

procedures for determining criterion-re

lated validity, such as those.described in

[APA Standards]” . Id. at subdiv. (a).

They state further that "[e]vidence of

content or construct validity, as defined

in that publication, may also be appro

priate where criterion-related validity is

not feasible.” Id.

Because this case was not

brought under Title VII and no resort

has been made to the EEOC as would be

required under the 1964 Act, the Com

mission Guidelines are not binding and

cannot finally resolve the issue whether

criterion-related validation is required.

However, the Guidelines are recognized

as relevant and useful as a “ helpful

summary of professional testing stand

ards” ( Vulcan, 490 F.2d at 394, n. 8)

and as “ persuasive standards for evalu

ating claims of job-relatedness” ( Vulcan,

360 F.Supp. at 1273, n. 23).»

Notwithstanding the Guidelines’ man

date of criterion-related validation and

despite suggestions in some cases that 8 *

8. See also Carter v. tiallngher, 452 F.2<1 3.15,

320, 320 (Slli Cir. 107.1), adopted in relevant

part, 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir.) (cn banc),

cert, denied. 400 U.K. 050, 02 S.Ct. 2045, 32

Ii.Kd.2d 338 (1072) ; Fowler v. Sehwarz-

walder, 351 F.Supp. 721, 724 (D.Minu.

1072); Pennsylvania v. O ’ Neill, 348 F.Supp.

.1081, 1103 ( K.l>.Pa.1072), a ffd in relevant

part, by an equally divided court, 473 F.2d

1020 ( 3d Cir. .1073) (cn bane) ; Western

Addition Community Organization v. Alioto,

340 F.Supp. 1351 (N .D .Cal.1072).

only that method suffices to carry the

burden of proof as to job-relatedness

( Vulcan, 360 F.Supp. at 1273; Guardi

ans, 354 F.Supp. at 789), no case in this

Circuit has gone so far as to hold that

failure to test an exam by criterion vali

dation or to demonstrate the nonfeasibil

ity of that approach justifies setting the

exam aside even if it has been content

validated. Those cases which have indi

cated a preference for criterion-related

validation have also found a lack of con

tent and construct validation before

striking down an examination. Further

more, the Court of Appeals for this Cir

cuit has recently abjured an absolutist

approach, stating that “ failure to use

I criterion-related validation ] is not fa

tal.” Vulcan, 490 F.2d at 395.

Defendants specifically admit

that 34-944 has not been validated by

the criterion-related approach. (Tran

script at 389; PX-2, answer to inter

rogatory 26.) However, in view of

Judge Friendly’s unambiguous statement

in Vulcan that criterion-related valida

tion is not required if the examination

can be validated by other means, we

turn our attention to the other valida

tion methods.

B. Construct Validation.

The second recognized method

of validation is “ construct validation.”

As defined by Judge Friendly in Vulcan,

this method “ requires identification of

general mental and psychological traits

believed necessary to successful perform

ance of the job in question. The quali

fying examination must then be fash

ioned to test for the presence of these

general traits.” s Vulcan, 490 F.2d at

9. The common example which is given to

highlight, the different, characteristics of the

content, and construct validation methods in

volves an examination for the position of

typist. A content valid test would require

the applicant to type. In such an instance

the content of I lie job and of the exam is

identical. A construct valid approach would

identify certain trails essential to success as

a typist, sueh as ability to eonccntrntc, per

severance and attention to detail, and would

examine tin; applicant for those traits. Vul

can, 490 F.2d at 395.

Opinion of District Court 9a

395. We mention this method only fo>-

the sake of completeness; none of the

parties has introduced evidence that

its use would be appropriate here or that

its requirements have been fulfilled.

, C. Content Validation.

We reach finally the dispositive issue

in the case: Have defendants demon

strated that 34-944 is a content valid ex

amination?

Initially, it is essential to deter

mine precisely what proof is necessary

to satisfy the requirements of content

validity. Judge Weinfeld’s definition in

Vulcan reflects the principles established

by case law and professional publica

tions:

“ An examination has content validity

if the content of the examination

matches the content of the job. For a

test to be content valid, the aptitudes

and skills required for successful ex

amination performance must be those

aptitudes and skills required for suc

cessful job performance. It is essen

tial that the examination test these at

tributes both in proportion to their

relative importance on the job and at

the level of difficulty demanded by

the job.” 360 F.Supp. at 1274 (foot

notes omitted). See also, Vulcan, 490

F.2d at 395; Guardians, 482 F.2d at

1338.

Accordingly, defendants must demon

strate not only that the knowledge, skills

and abilities tested for by 34-944 coin

cide with some of the knowledge, skills

and abilities required successfully to

perform on the job, but also that 1) the

attributes selected for examination are

critical and not merely peripherally re

lated to successful job performance: 2)

the various portions of the examination

are accurately weighted to reflect the

relative importance to the job of the at

tributes for which they test; and 3) the

level of difficulty of the exam matches

the level of difficulty for the job. In

sum, to survive plaintiffs’ challenge,

10. Tin: 14100(1 ( lm<U4im’.s stale; "KvidiMicc of

content validity alone may he acceptable for

well-developed tests that consist of suitable

34-944 must be shown to examine all or

substantially all the critical attributes of

the sergeant position in proportion to

their relative importance to the job and

at the level of difficulty which the job

demands.

The problem which confronts

the trier of fact when charged with

applying these principles to a given situ

ation is that normally, and it is the case

here, he is expert neither in psychome

trics nor in the field in which the exam

ination is given. Nevertheless, he is re

quired to make factual determinations

1) whether the examination meets pro

fessionally acceptable standards of tech

nical adequacy and 2) whether it has

content validity for the job in question.

(See. EEOC Guidelines, 29 C.F.R. at §

1607.5(a).) 10 To overcome the obstacle

presented by lack of expertise, the cases

have developed an approach which mini

mizes the obvious dangers inherent in

judicial determination of content validity

for a job about which the judge has, at

best, only superficial knowledge. Judge

Friendly described with approval the ap

proach taken by Judge Weinfeld in Vul

can as follows:

“ Instead of burying himself in a cjues-

tion-by-question analysis of Exam

0159 to determine if the test had con

struct or content validity, the judge

noted that it was critical to each of

the validation schemes that the exami

nation be carefully prepared with a

keen awareness of the need to design

questions to test for. particular traits

or abilities that had been determined

to be relevant to the job. As we read

his opinion, the judge developed a sort

of sliding scale for evaluating the ex

amination, wherein the poorer the

quality of the test preparation, the

greater must be the showing that the

examination was properly job-related,

and vice versa. This was the point he

made in saying that a showing of poor

preparation of an examination entails

the need of ‘the most convincing test!-

samples of flit* essential knowledge, skills or

behaviors composing 1 ho job in question.”

29 C.F.R. at § 1007.5(a).

10a Opinion of District Court