Secretary of Education v. Commonwealth of Kentucky Department of Education

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Secretary of Education v. Commonwealth of Kentucky Department of Education, 1984. 2fc62d2d-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dac21b2a-5498-4e45-b34b-55545743412f/secretary-of-education-v-commonwealth-of-kentucky-department-of-education. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

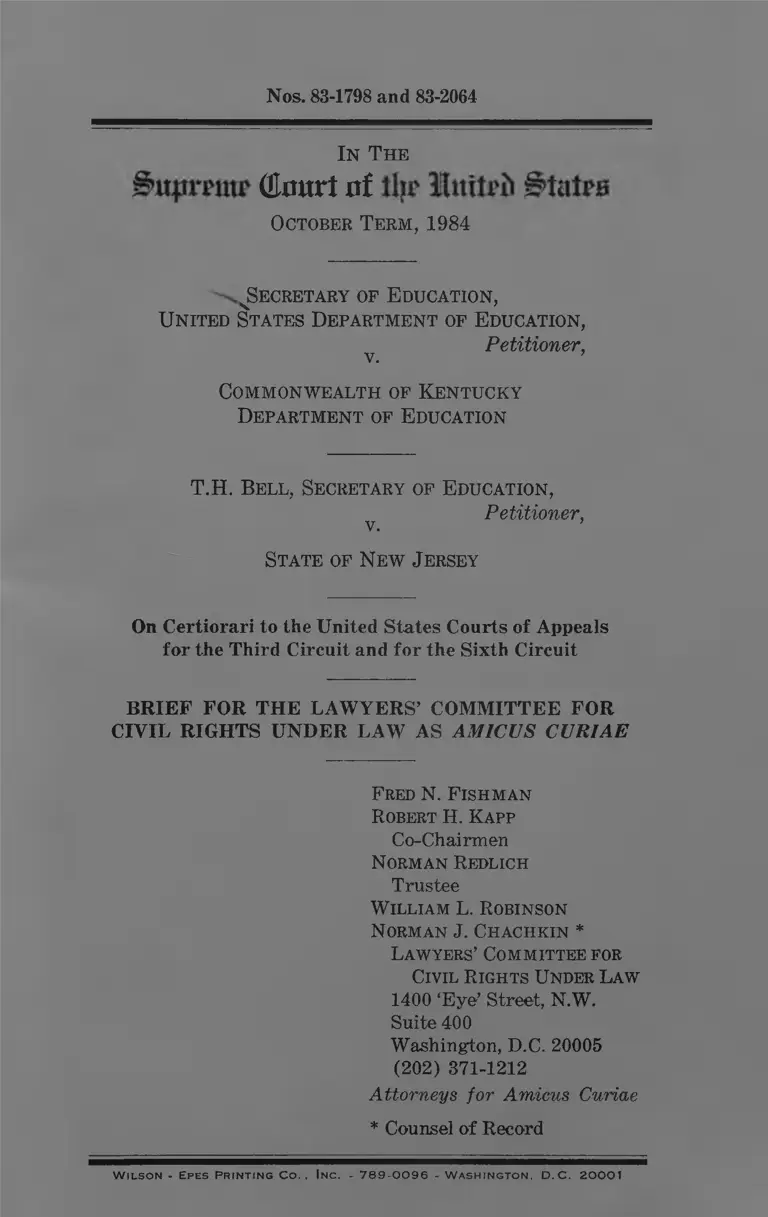

Nos. 83-1798 and 83-2064

In T he

(Enttrt at

October Term, 1984

^Secretary op E ducation,

United States Department of E ducation,

Petitioner,V.

Commonwealth op Kentucky

Department op E ducation

T.H. Bell, Secretary op E ducation,

Petitioner,V.

State op New J ersey

On Certiorari to the United States Courts of Appeals

for the Third Circuit and for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

Fred N. F ishman

Robert H. Kapp

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

William L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin *

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 ‘Eye’ Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

W i l s o n - Ep e s P r i n t i n g C o . . In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................... ii

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE.... .............................. 1

STATEMENT ........ 4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT........ .................................. 8

ARGUMENT...................................... 9

Introduction........ ................ 9

The Third Circuit’s Retroactivity Holding Is Con

trary to Established Legal Principles and Is Un

workable ................ 11

The Sixth Circuit Erred by Refusing to Follow the

Department of Education’s “Reasonable” Interpre -̂

tation of the Statute and Regulations and by In

venting a Wholly Inappropriate Standard for Re-

pajunent of Misspent Grant Monies........................ 17

The Eligibility and Supplanting Restrictions at

Issue in These Cases are Directly Related and

Critical to the Purposes of the Title I Program—

and the States Had Both Ample Notice of their

Applicability and Adequate Explanation of their

Requirements................................................................ 22

CONCLUSION........ ............................................................ 30

11

TABLE OF AUTaOBlTIES

Cases: Page

Alexander v. Califano, 432 F. Supp. 1182 (N.D.

Cal. 1977) ................ ................................ ...2n, 21, 23n

Bell V. New Jersey, —— U.S. ------, 76 L.Ed.2d

312 (1983) — ................ 'passim

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 416 U.S.

696 (1974)................ ............................................ .... 12,14

Chevron, USA v. Natural Resources Defense Coun

cil, 52 U.S.L.W. 4845 (U.S. June 25, 1984)....... 18n

Federal Election Commission v. Democratic Sen

atorial Campaign Committee, 454 U.S. 27

(1981)............................................... I8n

IndioMa Department of Public Instricction v. Bell,

728 F.2d 938 (7th Cir. 1984) ....... 18n

Kremer v. Chemical Construction Company, 456

U.S. 461 (1982) ...___ I2n

New Jersey v. Hufstedler, 662 F.2d 208 (3d Cir.

1981), rev’d sub nom. Bell v. New Jersey,------

U .S.------, 76 L.Ed.2d 312 (1983) ____________lOn-lln

Psychiatric I-nstitute of Washington, D.C. v.

Schweiker, 669 F.2d 812 (D.C. Cir. 1981)___ 18n, 20

United States v. Security Industrial Bank, 459

U.S. 70 (1982)......................................................... 13n

West Virginia v. Secretary of Education, 667 F.2d

417 (4th Cir. 1981)........ ........................ ................ 18n

Wheeler v. Barrera, 417 U.S. 402 (1974) ............. 5n, 25n

Statutes:

Chapter 1 of the Education Consolidation and Im

provement Act of 1981, Pub. L. No. 97-35,

§§ 552 et seq., 95 Stat. 464-69 (codified at 20

U.S.C. § 3801 et seq. (1982)) ........................ ........ 2n

Pub. L. No. 97-35, § 552, 95 Stat. 464 (codi

fied at 20 U.S.C. § 3801 (1982))........... ........ 2n

Pub. L. No. 97-35, §§ 556(b)(1), 558(b), 95

Stat. 466, 468 (codified at 20 U.S.C.

§§3805(b)(1), 3807(b) (1 9 8 2 )) ................ 2h

Department of Education Organization Act, Pub.

L. No. 96-88, 93 Stat. 668, reprinted in 1979

U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 668 (codified at

20 U.S.C. §§ 3401 et seq. (1982))......................... 4n

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Education Amendments of 1978, Pub. L. No. 95-

561, 92 Stat. 2143, reprinted in 1978 U.S. Code

Cong. & Ad. News 2143 et seq............................- 3n

Pub. L. No. 95-561, § 101(a), 92 Stat. 2143,

2161-62 (codified at 20 U.S.C. § 2732(a) (1)

(1982)) .................................... ..................... . 6n

Pub. L. No. 95-561, § 1530, 92 Stat. 2143,

2380, reprinted in 1978 U.S. Code Cong. &

Ad. News 2143, 2380 ________ ________ 12n

Elementary, Secondary, and Other Education

Amendments of 1969, Pub. L. No. 91-230,

§ 109(a), 84 Stat. 121, 124, reprinted in 1970

U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 133, 137 (codified

at 20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (3) (1970))_________ _ 29n

Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Educa ̂

tion Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-10, 79 Stat. 27,

reprinted in 1965 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

29, as renumbered by Pub. L. No. 89-750, § 116,

80 Stat. 1191, 1198, reprinted in 1966 U.S. Code

Cong. & Ad. News 1392, 1400____ _________ 4n

Pub. L. No. 89-10, §2, 79 Stat. 27, 30, re

printed in 1965 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad.

News 29, 33 (codified at 20 U.S.C. § 241e

(a) (1) (A) (Supp. IV 1968)) (current ver

sion at 20 U.S.C. § 2734d (1982) ................6n, 27n

Pub. L. No. 89-10, §205 (a) (1) (B), 79 Stat.

27, 30, reprinted in 1965 U.S. Code Cong. &

Ad. News 29, 33 (codified at 20 U.S.C.

§241e(a) (1) (B) (Supp. IV 1968))....... 24n

20 U.S.C. § 241c (2) (Sup-p. IV 1968) ........ ........... 23n

20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (1) (A) (1970) ........ ............... 5n

20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (1) (A) (Supp. IV 1968) ____ 23n

20U.S.C. § 241e(a) (3) (B) (1970)................ .......... 7n, 20

20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (3) (C) (1970)..... ................... 20

20 U.S.C. § 884 (Supp. IV 1974), as added by Pub.

L. No. 93-380, § 106, 88 Stat. 484, 512, reprinted

in 1974 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 541, 576.... 5n

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIE&--Continued

Page

20 U.S.C. § 1234a(g) (1982)....................................... 5n

20U.S.C. § 1234b(a) (1978)...................................... 19n

20 U.S.C. § 1234c(a) (1978).................. ..................... 19n

20 U.S.C. § 1234e(a) (2) (1982)....... ........................ lOn

20U.S.C.§ 2711(c) (1982) ....... ................................ 23n

20 U.S.C. § 2732 (1982)........... 23n

20 U.S.C. § 3803 (1982)........... 23n

20 U.S.C. § 3805 (b) (1) (A) (1982)........ 23n

20 U.S.C. § 3805 (b) (3) (1982)...........- ..... 24n

Regulations:

45 C.F.R. § 116.17(b) (1966)..................................... 25n

45 C.F.R.§ 116.17(d) (1968)............. ....................... 25n

45 C.F.R. § 116.17(f) (1966)............................ 27n

45 C.F.R. § 116.17(h) (1973)..... 21

45 C.F.R. § 116.17(h) (1968) .................- ................ 28n

32 Fed. Reg. 2742 (February 9, 1967).......... ............ 25n

Legislative Materials:

H.R. Rep. No. 805, 93rd Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted

in 1974 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 4093....... 5n

S. Rep. No. 634, 91st Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted in

1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 2768 .... ....... 9n, 20n,

29n

H.R. Rep. No. 1814, 89th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted

in 1966 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 3844....... 24n

Dismissing Certain Cases Pending Before the Edu

cation Appeal Board: Hearings on H.R. 8145

Before the Subcommittee on Elementary, Sec

ondary and Vocational Education of the House

Comm, on Educ. & Labor, 96th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1980) ................................................ ...................... 14n

Oversight Hearing on Amendments to Title I of

ESEA and GEPA: Hearings Before the Sub

committee on Elementary, Secondary and Voca

tional Education of the Hou.se Comm, on Educ.

& Labor, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. (1979)_______ 15n

Education Amendments of 1977: Hearings on S.

1753 Before the Subcommittee on Education,

Arts and Humanities of the Senate Comm, on

Human Resources, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. (1977).. 15n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES^Continued

Page

Elementary and Secondary Education Amend

ments of 1973: Hearings on H.R. 16, H.R. 69,

H.R. 5163, and H.R. 5823 Before the General

Subcommittee on Education of the House Comm,

on Educ. & Labor, 93rd Cong., 1st Sees. (1973),. 15n

129 Cong. Rec. (1984) ....... ..... ................................13n, 14n

127 Cong. Rec. (1981)................................................. 14n

116 Cong. Rec. (1970) ..................................... ........... 20n

111 Cong. Rec. (1965)............................................ . 27n

Other Authorities:

U.S. Office of Education, Title I Program Guide

No. 45A (July 31,1969)____________________ 26n

U.S. Office of Education, Title I Program Guide

No. 48 (November 20,1968).... ............................26n, 28n

U.S. Office of Education, Title I Program Guide

No. 44 (March 18,1968)........... ............................25n, 28n

U.S. Office of Education, Title I Program Guide

No. 28 (February 27,1967)._____ _____________ 25n

Washington Research Project, et al.. Title I of

ESEA: Is It Helping Poor Children? (1969).... 29n

In The

(Eo«rt at î tat̂ a

October Term, 1984

Nos. 83-1798 and 83-2064

Secretary op Education,

United States Department op Education,

Petitioner,V. ’

Commonwealth op Kentucky

Department op Education

T.H. Bell, Secretary op Education,

̂ Petitioner,

State op New J ersey

On Certiorari to the United States Courts of Appeals

for the Third Circuit and for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE i

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President of

the United States to involve private attorneys in the

national effort to assure civil rights for all Americans.

The Committee has, over the past 21 years, enlisted the

1 Letters from counsel for the parties consenting to the filing of

this brief have been submitted to the Clerk.

services of over a thousand members of the private bar

in addressing the legal problems of minorities and the

poor.

The Lawyers’ Committee has had a long-standing in

terest in Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Edu

cation Act of 1965^ because of the statutory emphasis

upon meeting the needs of poor and disadvantaged chil

dren. The Committee has sought to promote vigorous

enforcement of the programmatic and fiscal restrictions

in the statute and implementing regulations.®

2 In 1981 the Title I program was replaced by “Chapter 1” of the

Education Consolidation and Improvement Act of 1981, Pub. L.

No. 97-35, §§ 552 et seq., 95 Stat. 464-69 (codified at 20 U.S.C.

§§3801 et seq. (1982)). Chapter 1 retains the Title I focus upon

assisting educationally disadvantaged children residing in high

poverty areas, see Pub. L. No. 97-35, § 552, 95 Stat. 464 (codified

at 20 U.S.C. §3801 (1982)), as well as the specific targeting and

non-supplanting provisions of the Title I law, see id., §§ 556(b) (1),

558(b), 95 Stat. 466, 468 (codified at 20 U.S.C. § 3805(b)(1),

3807(b) (1982)). Hence, the rulings below have continuing im

portance for the major federal program of aid to elementary and

secondary schools.

® In the early 1970’s the Committee began to monitor the adminis

tration of the Title I program, in order to determine whether states

and local school districts were using their grants to operate projects

which carried out its basic purpose. These activities greatly in

tensified in 1975 with the establishment of the Committee’s Federal

Education Project. One of the Project’s major goals was to stimu

late adherence to the categorical restrictions of the Title I statute

and regulations in order to increase the effectiveness of local com

pensatory programs. The Project served as an informational re

source for parents of Title I participants and Title I staff in local

school districts, and it provided legal representation to parents of

Title I students in litigation and administrative complaint proceed

ings, including an important supplanting case, Alexander v. Cali-

fano, 432 F. Supp. 1182 (N.D. Cal. 1977).

In 1976, pursuant to a contract with the National Institute of

Education, the Lawyers’ Committee established a separately staffed

unit, the Legal Standards Project, to investigate and analyze the

legal framework of Title I. At the request of members of the

Congressional authorizing committees, this project subsequently

made extensive recommendations for legislative changes and pre-

Appl*Opriations for Title I and Chapter 1 were not and

are not unlimited. For this reason, each year thousands

of educationally deprived students cannot receive com

pensatory services. Congress was conscious of this fiscal

reality and wrote into law a set of requirements that

are central to the functioning of an effective program,

including (1) accurate targeting of compensatory proj

ects to serve only eligible schools and attendance areas,

and (2) continuation of state and local expenditures for

basic education programs for participating children so

that federally funded projects provide extra services to

needy students.

Compliance with these requirements is essential, in our

judgment, to the educational effectiveness of compensatory

instruction projects funded by the federal government.

Our experience indicates that meaningful compliance de

pends, in significant part, upon the expectation that audit

and recoupment of misspent funds will follow any failure

to adhere to the terms and conditions of the program.

Thus, the Committee is concerned that the holdings below,

anouncing rules of construction which defeat recovery of

funds not expended in accordance with grant-in-aid agree

ments accepted by Kentucky and New Jersey, will have

a detrimental impact upon educational opportunities for

poor children by weakening the incentive for adherence

to statutory and regulatory requirements.

Rather than crediting ingenious arguments that evade

the Congressional intention expressed in these statutory

restrictions, as the courts below did, state and local edu

cation officials should be held to adhere to the fiscal and

program limitations of federal law, as interpreted by the

Department of Education, when audit proceedings are

subjected to judicial review.

pared a draft bill. Many of its suggestions were incorporated in the

Education Amendments of 1978, Pub. L. No. 95-561, 92 Stat. 2143,

reprinted in 1978 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 2143 et seg., and the

Congress’ reliance upon the work of the Legal Standards Project is

acknowledged in the legislative history of the 1978 amendments.

STATEMENT

In 1965, Congress enacted Title I of the Elementary

and Secondary Education Act,^ which provided federal

grants to states and local school districts for programs

designed to assist educationally deprived children in areas

with high concentrations of low-income families. In order

to ensure that Title I grants benefited these children, the

statute included specific conditions with which state edu

cation agencies (SEAs) and local education agencies

(LEAs) were required to comply.® Two conditions are

particularly relevant to these cases: first, Title I funds

could be expended only for projects serving eligible at

tendance areas and schools; second, students participat

ing in Title I projects had to receive their “fair share”

of state and local expenditures so that federal funds

provided truly supplemental services.® State and federal

audits were authorized to assess local compliance with

statutory criteria.

New Jersey and Kentucky participated in the Title I

program each year following its enactment and were

aware of the various statutory and regulatory require

ments for participation. However, audits conducted by

the United States Department of Health, Education and

Welfare ̂ resulted in determinations that both States had

misapplied substantial amounts of federal Title I funds.

<Pub. L. Xo. 89-10, 79 Stat. 27, reprinted in 1965 U.S. Code

Cong. & Ad. News 29, as renumbered by Pub. L. Xo. 89-750, § 116,

80 Stat. 1191. 1198. reprinted in 1966 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

1392. 1400.

® These conditions were repeated and amplified in the administra

tive regulations and further clarified in numerous Title I Program

Guides sent to all of the states as earlj- as 1968. Sfe f»/ra notes 48-

51 i accompanying text, 55-57 & aocompanyins text,

* The same sorts of restrictions apply to the grant-in-aid prv>-

gram which replaced Title I. 8cc .s«pr« note 2,

■ The Title I pnigram was administertHl by the Pepsrtnient of

Health, Education and Welfare prior h> the creation of the De

partment of Education by Pub. U No. 96-88. 9.3 8tat, 668. reprinted

in 1979 U.S. Code Cong. .4d. News 668 vovnlified at 20 U.8.C,

§13401 et se4. (1982)).

New Jersey. Federal auditors found that the SEA in

correctly approved Title I grant applications for the 1970-

71 and 1971-72 school years from the Newark LEA,

which then used the grant funds in school attendance

areas that were not eligible to participate in the Title I

program.® New Jersey disputed these findings,® but ex

cept for reductions required by a “statute of limita

tions” “ the Education Appeal Board sustained the

auditors’ claims and the Secretary of Education declined

® See Joint Appendix at 11-34, Bell v. New Jersey,----- U.S.------ ,

76 L. Ed. 2d 312 (1983) (Final Audit Report) [hereinafter cited

as N.J.J.A.]. The federal statute required that projects be located

to serve “school attendance areas having’ high concentrations of

children from low-income families,” 20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (1) (A)

(1970). Regulations and Title I Program Guides issued between

1965 and 1970 by the Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare, see Wheeler v. Barrera, 417 U.S. 402, 407, 420 n.l4 (1974),

defined this term to mean attendance areas having higher-than-

average numbers or percen'tages of children from poor families than

the school district as a whole. See generally N.J.J.A. at 14-16;

infra pp. 23-27.

® The dispute as to the 1970-71 school year is whether the Newark

LEA qualified for an exception to the usual eligibility requirement,

see supra note 8, because there was “no wide variance,” within the

meaning of the regulations and Program Guides, in the level of

poverty among the district’s school attendance areas. The dispute

as to the 1971-72 school year concerns the correct manner of docu

menting and comparing levels of poverty among attendance areas in

determining eligibility.

w> 20 U.S.C. § 884 (Supp. IV 1974), as added by Pub. L. No. 93-

380, § 106, 88 Stat. 484, 512, reprinted in 1974 U.S. Code Cong. &

Ad. News 541, 576, provided that:

No state or local educational agency shall be liable to refund

any payment made to such agency under this Act (including

Title I of this Act) which was subsequently determined to be

unauthorized by law, if such payment was made more than

five years before such agency received final written notice that

such payment was unauthorized.

See also H.R. Rep. No. 805. 93rd Cong., 2d Sess. 78-79, reprinted in

1974 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 4093, 4160. The currently ap

plicable version of this provision is codified at 20 U.S.C. § 1234a (g)

(1982).

to disturb its decision.^ On review of the Department’s

action in the Court of A p p e a ls ,a panel held that 1978

amendments to Title I which eased the eligibility require

ments for school attendance areas should be given retro

spective effect so as to validate the earlier expenditures

to the extent that they would have been proper under

the new eligibility criteria.^^ The panel remanded to the

Secretary of Education to determine precisely which of

the challenged expenditures would have been permissible

under the 1978 statutory amendments.^®

See N.J. Pet. at 13a-15a.

12 See id. at 15a n.l2.

13 Pub. L. No. 95-561, § 101(a), 92 Stat. 2143, 2161-62 (codified at

20 U.S.C. § 2732(a)(1) (1982)).

11 N.J. Pet. at 4a-5a.

1® There are two reasons why the expenditures in question might

not have been lawful even had they been made after 1978. First,

as the court below recognized, use of the provision added in 1978

was conditioned upon a special “maintenance of effort” requirement

for compensatory programs; since New Jersey had not sought to

rely upon the 1978 law prior to review in the Court of Appeals,

the record previously made in the administrative proceedings is not

adequate to determine whether this condition has been met (see

N.J. Pet. at 5a). Second, the Title I law and regulations always

required that projects be of “sufficient size, scope and quality” to

offer hope of significant achievement gains for participants. See

Pub. L. No. 89-10, § 2, 79 Stat. 27, 30, reprinted in 1965 U.S. Code

Cong. & Ad. News 29, 33 (current version at 20 U.S.C. § 2734(d)

(1982)). This requirement usually resulted in a school district’s

establishing Title I projects at fewer than all eligible schools, in

light of limited Congressional appropriations—^vhich never reached

the authorization level contained in the statute. See infra note 51.

Because, in this case, the federal auditors determined that the num

ber of eligible schools was itself improperly inflated, they had no

occasion to consider whether Newark's Title I program during the

years in question otherwise met the "size, scope and quality" re

quirement. Thus, even if the 1978 amendments' 25‘'( -eligibility pro

vision could be used in Newark, questions about the program's

ccniormity with other statutory and regulatory requirements would

remain. Nevertheless, this matter is ripe for review since the deci-

Kentucky. In Fiscal Year 1974, with SEA approval,

some 50 LEAs throughout the state placed first- and

second-grade Title I participants in separate classrooms

with Title I teachers. Except for a few “enrichment

classes,” these students received their entire academic

instruction, including the basic state-mandated curricu

lum, through the federally funded Title I program.^®

Although gross state and local expenditures at Title I

schools were not reduced, again with the exception of the

enrichment classes the students participating in Title I

did not receive the benefit of any of these expenditures.

Federal auditors concluded that these practices consti

tuted “supplanting” in violation of the statutory require

ment that Title I funds

be [so] used (i) as to supplement . . . the level of

funds that would, in the absence of such Federal

funds, be made available from non-Federal sources

for the education of pupils participating in programs

and projects assisted under this subchapter, and (ii)

in no case, as to supplant such funds from non-

Federal sources.̂ "̂

With certain modifications not relevant to the issues be

fore this Court, the Education Appeal Board and the

Secretary of Education upheld the auditors’ supplanting

findings.^® A panel of the Court of Appeals, however.

sion below finally—and erroneously—determines the issue of retro

activity and will bind the Department of Education in Title I audit

cases which are now pending and which may in the future arise

from the States within the Third Circuit. Cf. N.J. Pet. at 16 ($68

million in Title I audit claims pending).

Ky. Pet. at 22a (findings of Education Appeal Board).

” 20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (3) (B) (1970) (emphasis added).

18 The Audit Report sought repayment only of those Title I funds

expended on readiness classes for students who were promoted to

the next grade level at the end of the school year—apparently to

avoid any question whether students retained at the same grade

level would ultimately receive their “fair share” of state and local

8

refused to sustain the repayment demand. While the De

partment’s interpretation of the statutory anti-supplant

ing language and implementing regulations was “reason

able” and would be controlling in future cases, the Court

of Appeals said:

[T]he statutory and regulatory provisions at issue

were [not] sufficiently clear to apprise the Common

wealth of its responsibilities. . . .

[I]t is unfair for the Secretary to assess a penalty

against the Commonwealth for its purported failure

to comply substantially with the requirements of law,

where there is no evidence of bad faith and the

Commonwealth’s program complies with a reasonable

interpretation of the law. *̂

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Because the 1978 amendments to Title I explicitly were

not made effective prior to October 1, 1978; because the

statutory change upon which New Jersey seeks to rely is

a substantive, rather than procedural or remedial one;

because this matter arises from the state’s voluntary ac

ceptance of pre-1978 statutory terms and conditions under

a federal grant program; and because the rule of retro

activity adopted by the Third Circuit is unworkable in

resources when they repeated the same curriculum. See Joint Ap

pendix in No. 83-1798, at 17 (Final Audit Report). The Depart

ment of Education adopted this position, despite the misgivings of

the Education Appeal Board (see Ky. Pet. at 30a), and the case does

not now turn upon the propriety of this approach. See Ky. Pet. at

16a. Additionally, the Secretary reduced the demand for repayment

in light of the fact that the “readiness” classes were smaller than

most regular classes in the state (see Ky. Pet. at 38a-42a). The

correctness of this adjustment is also irrelevant at this time: the

Sixth Circuit’s ruling eliminates any repayment of any funds on

account of any supplanting.

Ky. Pet. at 9a-10a, 12a.

9

both the legislative and administrative process, its judg

ment should be reversed.

II

Because the case before the Sixth Circuit originated

in Kentucky’s petition for judicial review of agency ac

tion, once the Court of Appeals concluded that the Edu

cation Department’s interpretation of the Title I statute

and regulations was a “reasonable” one, it should have

deferred to the agency. In addition, the view of the

panel below that the statute and regulations were am

biguous is unsupportable.

III

Contrary to the arguments of New Jersey and Ken

tucky and the intimations of the courts below, the grant

conditions which the auditors found those states to have

violated were adopted early in the history of the Title I

program, were repeatedly communicated to the states,

and were critical to the effectiveness of the compensatory

projects funded by the federal government.

ARGUMENT

Introduction

In Bell V. New Jersey, U.S. -, 76 L. Ed.

2d 312, 326 (1983), this Court ruled “that the pre-1978

version of [Title I] requires that recipients be held

liable for funds that they misuse” '̂ by making repay-

^ See also id., 76 L. Ed. 2d at 322, quoting S. Rep. No. 634, 91st

Cong., 2d Sess. 84, reprinted in 1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

2768, 2827 (“Even though there may be difficulties arising from

recovery of improperly used funds, those exceptions must be en

forced if the Congress is to carry out its responsibility to the tax

payer”). The states are, of course, accorded substantial opportuni

ties to demonstrate the propriety of challenged expenditures and

have a right to judicial review prior to making any repayment. See

id., 76 L. Ed. 2d at 327-28.

10

ment to the United States.'̂ ̂ The decisions below will

substantially frustrate the ability of the federal govern

ment to obtain such repayments. Without any basis in

the statutory language or legislative history, and con

trary to longstanding administrative interpretations of

the law, the courts below extinguished the obligations of

Kentucky and New Jersey to repay Title I funds ex

pended in contravention of statutory and regulatory pro

visions^ in force at the time the states accepted Title I

Up to 75% of the amount recovered may be returned to the

state to be used, “to the extent possible, for the benefit of the popu

lation that was affected by the failure to comply or by the mis-

expenditures which resulted in the audit exception,” 20 U.S.C.

§ 1234e(a) (2) (1982). See Ky. Pet. at 15 n.l3.

22 For purposes of resolving the legal issues presented to this

Court, it must be assumed that the states and their constituent

LEAs failed to comply with relevant federal program requirements.

See Bell v. New Jersey, 76 L. Ed. 2d at 327.

In the Kentucky case, the Sixth Circuit panel declined to enforce

the Secretary’s demand for repayment because of its view that the

Title I regulations were “ambiguous,” the misexpenditures identi

fied by the auditors therefore did not constitute “substantial non-

compliance,” and for this reason repayment of the misspent funds

was an “unfair . . . penalty” {id. at 12a). But the Court of Appeals

agreed that the expenditures for “readiness” classes were incon

sistent with the Department of Education’s “reasonable” interpre

tation of the Title I statute and regulations (Ky. Pet. 8a-9a) and

the Commonwealth has not challenged that determination.

In the New Jersey case, the state has acknowledged that “ ‘there

were irregularities in the original grant approval process’ ” (N.J.

Pet. 46a) resulting from the presence of a “fiaw in the initial

formula” used to determine eligible school attendance areas in the

Newark district {id. at 45a). See id. at 40a (Decision of Education

Appeal Board) (“the New Jersey SEA admits it did not meet the

Title I requirements for determining the eligibility of school at

tendance areas for Title I funding when it approved Newark’s

1971-72 project application with respect to 13 Newark schools”).

Although New Jersey argued that at least some of these schools

would have been eligible under a proper formula {see id. at 8a),

the Third Circuit never decided this question. In 1981 that court

held that the Secretary of Education had no authority to order

repayment of misexpended funds, New Jersey v. Hufstedler, 662

11

grants.®

We agree fully with the United States that the rulings

below are doctrinally unsound, for the reasons outlined

in the first two arguments below. In addition, we sub

mit that these rulings may ultimately be traced to the

lower courts’ erroneous perception that states and local

school districts were burdened by unfair or unclear pro

grammatic and fiscal restrictions which interfered with

the educational efficacy of Title I projects. However, as

we show in the third argument, the conditions which

New Jersey and Kentucky violated were very deliberately

inserted into the statutory scheme by Congress; they are

central to the success of the compensatory education

effort; they are comprehensible and capable of straight

forward application; and they were promulgated and

clearly explained to state officials by the federal govern

ment prior to the misexpenditures which are the subject

of these suits.

The Third Circuit’s Retroactivity Holding Is Contrary to

Established Legal Principles And Is Unworkable

In the New Jersey case, the Third Circuit erroneously

applied well-settled rules of statutory construction when

it held that eligibility criteria enacted in 1978 could be

F.2d 208, rev’d sub nom. Bell v. New Jersey, U.S. 76

L. Ed. 2d 312 (1983). On remand, the Third Circuit applied 1978

statutory amendments retroactively to validate Newark’s eligibility

determinations which, it said, “arguably overstated the relative

size of the class of students from low-income families” (N.J. Pet.

at 3a). The only question now before this Court, therefore, is

whether the 1978 amendments should have been applied in this

retrospective manner to excuse New Jersey from the obligation it

would otherwise have to repay funds to the Department of

Education.

See 76 L. Ed. 2d at 326 (“The State chose to participate in

the Title 1 program and, as a condition of receiving the grant,

freely gave its assurances that it would abide by the conditions of

Title I”).

12

applied retrospectively, so as to excuse a Title I grant

recipient’s noncompliance with different criteria that

were contained in federal law when the disputed expendi

tures were made (in 1970-71 and 1971-72). The 1978

amendments to Title I specifically provided that “the

provisions of this Act and the amendments and repeals

made by this Act shall take effect October 1, 1978.̂ ®

Thus, the panel below erred in concluding that “ [tjhere

is . . . nothing in the 1978 amendments or the legisla

tive history [which] indicates that the amendments were

not intended to be applied retroactively” (N.J. Pet. 4a).

And, that being the case, the predicate for application of

the Bradley '̂ principle evaporates.

Moreover, Bradley involved remedial, not substantive,

changes in the law; ^̂ thus, even in the absence of the

legislative directive for prospective application contained

in the 1978 amendments,®* Bradley would be inapplicable.

Where new legislation alters a substantive provision of

24 New Jersey does not contend, and the Third Circuit did not

hold, that the 1978 amendments explicitly repealed or explicitly

amended, retrospectively, the previous eligibility standards which

the auditors found to have been violated. Repeals by implication of

course are not favored. E.g., Kremer v. Chemical Construction

Company, 456 U.S. 461, 468-78 (1982).

2® Pub. L. No. 95-561, § 1530, 92 Stat. 2143, 2380, reprinted in

1978 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 2143, 2380.

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 (1974).

See N.J. Pet. 4a.

2̂ In Bradley, this Court noted that upon enactment of § 718 of

the Education Amendments of 1972, authorizing the award of at

torneys’ fees to prevailing plaintiffs in school desegregation cases,

“there was no change in the substantive obligation of the parties.”

416 U.S. at 721. Here there is no question about the substantive

impact of the 1978 amendments in altering school attendance area

eligibility criteria. See also Bell v. New Jersey, 76 L. Ed. 2d at

318 n.3.

28 See supra note 25 and accompanying text.

IS

a statutory scheme, the general rule is that it is to be

given prospective effect only.®®

2® F.ff., United States v. Security Industrial Bank, 459 U.S. 70,

79 (1982). Compare N.J. Pet. at 17a-18a (summarizing New

Jersey’s earlier arguments against retroactive application of 1978

amendment to Title I delineating audit repayment obligation).

Congress uses explicit language when it wishes a substantive

statutory amendment to have retrospective effect. For example, in

1984 the House of Representatives adopted amendments to the

Gneral Education Provisions Act designed to alter the auditing and

repayment process. See 129 Cong. Rec. H7891 (introduction of

final version), H7902-03 (§ 808), H7904 (passage) (daily ed„

July 26, 1984). These amendments deliberately avoided the use of

language which would have given them retrospective application in

pending audit proceedings. As their primary floor sponsor recog

nized, retroactivity

would violate the basic principle that grantees should be held

accountable for the expenditures of funds under the law as it

was when they received the funds. A current law standard

would treat differently grantees who received funds at the

same time. Depending on when they were audited, grantees

would be held to different program requirements based upon

the state of the law when they were audited. A grant might be

made on the basis of one set of standards, an audit conducted

on a second, an administrative appeal heard on a third, and

judicial review sought on a fourth.

Id. at H7814 (Rep. Ford) (daily ed., July 25,1984).

However, the measure adopted by the House would have made

certain provisions of the 1978 Title I amendments retrospective.

Section 808(a) (4) of Rep. Ford’s floor amendment, id. at H7903

(daily ed., July 26, 1984), provided:

In any final audit determination pending before the Secretary

of Education or the Education Appeals Board on or made

after the date of enactment of this Act pursuant to section 452

of the General Education Provisions Act (20 U.S.C. 1234b), the

provisions of sections 122(a)(1) and 132 of the Elementary

and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (20 U.S.C. 2732(a) (1),

2752) shall be considered to apply with respect to expendi

tures made before October 1, 1978, in the same manner that

such provisions apply to expenditures made on or after that

date, without regard to the provisions of subsections (b) (2),

14

There is a further reason why the Bradley principle is

inapplicable to the dispute between New Jersey and the

United States. Because it arises out of the state’s volun

tary acceptance of federal funds in exchange for “its

assurance that it would abide by the conditions [con

tained in the statute and r e g u l a t i o n s ] t h e case is

governed by principles of contract law. Post-grant leg

islation is relevant only insofar as it unambiguously rep

resents a waiver of the contractual conditions.® Absent

such a waiver, there is no basis for modifying the con-

(e), and (f) of section 131 of such Act (20 U.S.C. 2751) requir

ing that certain determinations be made in advance.

This portion of the bill would have mooted the New Jersey case by

authorizing retrospective use of the “25% rule.” It was, however,

dropped from the legislation prior to its final passage. See 129

Cong. Rec. S12906 (Sen. Hatch), S12908 (Sen. Kennedy) (“One

issue that was included in the House legislation but dropped in

conference was the audit reform provisions”), S12909 (passage of

conference report) (daily ed., October 3, 1984); id. at H11425

(Rep. Hawkins), id. (Rep. Jelfords), H11426 (Rep. Ford), H11429

(Rep. Goodling), H11430 (acceptance of conference report) (daily

ed., October 4, 1984).

This history indicates that the Congress can and does employ

explicit retroactivity language when it desires to create an excep

tion to the general rule that substantive amendments apply only

prospectively, especially in grant programs.

Bell V. New Jersey, 76 L. Ed. 2d at 326-27; see also, i d . at 329

(White, J., concurring).

Enactment of a bill directing the Secretary of Education not to

seek to recover misexpenditures identified in audits completed prior

to a specified date would constitute a waiver. (Such measures were

considered by the Congress in 1980 and 1981 but never enacted. See

Dismissing Certain Cases Pending Before the Education Appeal

Board: Hearings on H.R. 8145 Before the Subcommittee on Ele

mentary, Secondary and Vocational Education of the House Comm,

on Educ. & Labor, 96th Cong.. 2d Sess. (1980) (bill never reported

ou t); 127 Cong. Rec. S5427-30, S5442 (daily ed.. May 21, 1981)

(floor amendment rejected on point of order).) Similarly, the

five-year “statute of limitations” on repayment of misexpenditures

of Title I funds, see supra note 10, is such a waiver under the

circumstances specified in that provision.

15

tractual understanding between the parties by virtue of

a subsequent enactment applying to future grants; this

amounts to rewriting the contract to the detriment of the

Department of Education, and that of the program’s

beneficiaries.

Finally, because of its consequences both for the legis

lative process and for administration of federal assist

ance programs, the Third Circuit’s ruling is unworkable.

As this Court is well aware, the statutory framework of

federal grant programs rarely remains completely un

changed; rather, successive Congresses often amend and

re-amend an enactment in the light of experience and

perceptions. Indeed, State and local grantees are among

the most fervent supporters of this “fine tuning.” For

this reason, if the decision below is permitted to stand,

federal grantees subject to audit exceptions can be ex

pected to seek repeated statutory changes that would

make their past non-compliance with program require

ments conform to the law. The incentive to maintain

compliance with statutory and regulatory provisions will

*2 See, e.g., Oversight Hearing on Amendments to Title I of

ESEA and GEPA: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Elemen

tary, Secondary and Vocational Education of the House Comm, on

Educ. & Labor, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. 26-32 (1979) (testimony of New

York City Schools Chancellor Macchiarola supporting amendment to

drop matching funds requirement for schoolwide projects) ; Educa

tion Amendments of 1977: Hearings on S. 1753 Before the Sub

committee on Education, Arts and Humanities of the Senate Comm,

on Human Resources, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 1554-58 (1977) (state

ment of Akron Superintendent of Schools Conrad Ott, requesting

amendment to permit continuing services to students who formerly

attended Title I-eligible schools that were closed); id. at 1397-99

(statement of Pennsylvania Secretary of Education Caryl M. Kline,

proposing modification of supplanting provision) ; Elementary and

Secondary Education Amendments of 1973: Hearings on H.R. 16,

H.R. 69, H.R. 5163, and H.R. 5823 Before the General Subcommittee

on Education of the House Comm, on Educ. & Labor, 93rd Cong., 1st

Sess. 419 (1973) (testimony of Chicago Assistant Superintendent

James Moffat, seeking elimination of annual school eligibility

requirement).

16

be substantially diminished; federal program benefici

aries—in this case, educationally disadvantaged children

who most need assistance— ŵill be the losers.

The Third Circuit’s approach imputes to the Congress,

each time a grant program statute is amended, an inten

tion to have the new provision apply in all pending ad

ministrative or judicial proceedings that relate to prior

grants. Adoption of this standard, so different from

that which presently prevails;®* will vastly complicate

the legislative process. Deliberations about the public

policy benefits of any particular amendment will have

to be accompanied by the production and analysis of

large quantities of information about the current status

of all audit exceptions or claims under the grant pro

gram, in order to assess the impact of retrospective

application of the amendment in such proceedings. It

simply defies experience to expect that the Congress will

be able to shoulder these additional burdens and engage

in reasoned lawmaking.

Since audit or claim proceedings often take years to

resolve, many will be repeatedly affected by statutory

changes under the Third Circuit’s ruling, largely depriv

ing the administrative enforcement process of the final

ity which is necessary if grantees are to know what is

expected of them. Moreover, while the result is to New

Jersey’s liking in this instance, there seems to be no com

pelling reason why statutory changes which tighten,

rather than relax, program requirements should not also

be given retrospective application according to the rule

adopted below. For it is inherently no more unjust to

recover grant funds from states which fail to anticipate

changes in the law than it is to deprive participants in

federally funded grant programs of substantial addi

tional benefits because of such changes.

See supra note 29 and accompanying text.

See supra note 21.

17

It is far more realistic, and sensible, to give substan

tive statutory changes retroactive effect only when Con

gress explicitly indicates its intention that this result

should obtain.®' That has long been the preferred ap

proach; because the Third Circuit panel departed from

that approach without justification, its judgment can

not stand.

II

The Sixth Circuit Erred by Refusing to Follow the De

partment of Education’s “Reasonable” Interpretation of

the Statute and Regulations and by Inventing a Wholly

Inappropriate Standard for Repayment of Misspent

Grant Monies

The Kentucky case reached the Sixth Circuit as a re

sult of the state’s petition for review of final adminis

trative action taken by the Department of Education."**

Accordingly, the task of the court below was a limited

one: to determine “whether the [factual] findings of

the Secretary are supported by substantial evidence and

reflect application of the proper legal standards. § 455,

20 U.S.C. § 1234d(c); 5 U.S.C. § 706.” Bell v. New

Jersey, 76 L. Ed 2d at 328.

There was no controversy over the facts. The use of

substantial amounts of Title I grant funds for “readi

ness” classes which substituted for participating stu

dents’ regular, state and locally funded, academic educa

tion is admitted. The only matter for determination by

the reviewing court was whether the reading of the

statutory anti-supplanting language which is embodied

in Departmental regulations, Program Guides, and the

Secretary’s interpretations thereof, was proper. As this

Court has often emphasized, in this situation

the task for the Court of Appeals was not to inter

pret the statute as it thought best but rather the

See supra note 29.

See Bell v. New Jersey, 76 L. Ed. 2d at 318-20 n.3.

18

narrower inquiry into whether the [agency’s] con

struction was “sufficiently reasonable” to be accepted

by a reviewing court. Train v. Natural Resources

Defense Council, 421 U.S. 60, 75 (1975); Zenith Ra

dio Corp. V. United States, 437 U.S. 443, 450 (1978).

To satisfy this standard it is not necessary for a

court to find that the agency’s construction was the

only reasonable one or even the reading the court

would have reached if the question initially had

arisen in a judicial proceeding. Zenith Radio Corp.

V. United States, 437 U.S. 443, 450 (1978); Udall

V. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1, 16 (1965); Unemployment

Compensation Commission v. Aragon, 329 U.S. 143,

153 (1946).®'

The Sixth Circuit panel concluded that the Secretary’s

interpretation of the supplanting prohibition was “rea

sonable,” Ky. Pet. at 8a & n.6. Indeed, far from finding

that interpretation to be contrary to law, the Sixth Cir

cuit agreed that, at least prospectively, it would be con

trolling. Id. at 12a. Pursuant to the precedent cited

above, that should have been the end of the matter. In

stead, the panel below embarked upon a wholly different

inquiry than that directed by this Court:

Nonetheless, in the instant case we do not feel it is

our task on appeal to review the reasonableness of

the Secretary’s interpretation of Title I section 241

e(a) (3) (B) and regulation section 116.17(h). We

are not reviewing with reference to the future effect

of the Secretary’s interpretation of a statute.

Rather, in this appeal we are concerned with the

fairness of imposing sanctions upon the Common

wealth of Kentucky for its “failure to substantially

Federal Election Commission v. Democratic Senatorial Cam

paign Committee, 454 U.S. 27, 39 (1981) ; accord, e.g.. Chevron,

U.S.A. V. Natural Resources Defense Council, 52 U.S.L.W. 4845,

4847 n .ll (U.S. June 25, 1984) ; Indiana Department of Public

Instruction v. Bell, 728 F.2d 938, 940 (7th Cir. 1984) ; Psychiatric

Institute of Washington, D.C. v. Schweiker, 669 F.2d 812, 813-14

(D.C. Cir. 1981) (per curiam) ; West Virginia v. Secretary of Edu-

27-29, is a rational one. See Ky. Pet. at 11 n.9.

19

comply” ® with the requirements of section 241e

(a ) (3 ) (B ) and 45 C.F.R. 116.17(h), as those re*-

quirements were ultimately interpreted by the

Secretary.

8 See 20 U.S.C. § 1234b (a) and § 1234c (a) (1978) (where

the Commissioner is said to act upon the belief that a recipient

of funds had “failed to comply substantially” with any re

quirement of law applicable to such funds).

Id. at 9a (footnote omitted).

There simply is no basis in law for this approach.

Nothing in the Title I statute suggests that there should

be one standard of deference to the administrative

agency’s interpretation in a declaratory judgment action

looking to the future and another in a judicial review

proceeding following an audit and demand for repay

ment.®* “ [T]he pre-1978 version [of Title I] contem

plated that States misusing federal funds would incur

a debt to the Federal Government for the amount mis

used . . . .” Bell V. New Jersey, 76 L. Ed 2d at 321.

If the law were as stated by the court below, then fed

eral grantees could with impunity ignore the “reason

able” interpretations of statutory and regulatory lan

guage by administrative agencies until those interpreta

tions were first confirmed in court. This would largely

defeat the purpose of delegating interpretive rulemak

ing authority to the agencies in the first place. The fact

that the Court of Appeals viewed the statute and regu

lations as ambiguous, see Ky. Pet. at 9a-10a, 12a, 15a,

does not justify the Sixth Circuit’s lack of deference to

the agency’s reading of the law, for it is Congress’ in-

38 20 U.S.C. §§ 1234b(a) and 1234c(a), cited in footnote 8 of the

Court of Appeals’ opinion, are inapposite since they deal only with

cease-and-desist orders and withholding proceedings, rather than

audits. The difference in standard, which in any event would not

lead to a difference of result in the Kentucky case, see infra pp.

27-29, is a rational one. See Ky. Pet. at 11 n.9.

20

tention that the administrative agency should make the

choice among alternative interpretations. See, e.g., Psy

chiatric Institute of Washington, D.C. v. Schweiker,

supra note 37.

Even on its own terms, the decision below is not de

fensible. Although the Sixth Circuit characterized Ken

tucky’s position as a “reasonable” one, it supported this

assertion only with very general statements from the

legislative history of Title I. See Ky. Pet. at lla-12a.

The panel simply slid over the precision of the statu

tory language requiring that federal funds not sup

plant “funds that would, in the absence of such Federal

funds, be made available from non-Federal sources for

the education of pupils participating in programs and

projects assisted” by Title I, 20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (3)

(B) (1970) (emphasis added). See Ky. Pet. at 20a.

It also ignored Congress’ separate insertion into the

Title I law in 1970 of a “comparability” requirement,

20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (3) (C) (1970), which is addressed

specifically to equivalence of school-level expenditures,

rather than to participant entitlements.®®

The Sixth Circuit similarly gave little attention to the

Title I supplanting regulation in force at the time of

the expenditures in question, which was equally explicit

about the need to provide Title I participants with their

fair share of state and local expenditures:

Each application for a grant under Title I of the Act

for educationally deprived children residing in a

project area should contain an assurance that the

use of the grant funds will not result in a decrease

in the use for educationally deprived children resid

ing in that project area of State or local funds

See S. Rep. No. 634, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 14-15, reprinted in

1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 2768, 2781-82; 116 Cong. Rec.

10613 (Rep. Quie) (daily ed., April 17, 1970).

21

which, in the absence of funds under Title I of the

Act, would be made available for that project area

and that neither the project area nor the educa

tionally deprived children residing therein [i.e., Title

I participants] will otherwise he penalized in the

application of State and local funds because of such

a use of funds under Title I of the Act.

45 C.F.R. § 116.17(h) (1973) (emphasis added). The

real problem which the Court of Appeals had with the

Kentucky audit exception apparently was not the sup

posed ambiguity of the statute or regulations, but the

panel’s lack of sympathy with the policy choice made by

Congress:

Given a fixed number of dollars awarded to the

school district, the requirement that average per

pupil expenditures be transferred to the Title I

classrooms, in proportion to the number of students

in attendance there who are expected to advance a

grade, cannot help but have an adverse impact on

the funds available for the regular classroom when

the number of regular classrooms and teachers can

not be reduced.^

Ky. Pet. at 15a. As we pointed out at the beginning of

this section, however, the task of a Court of Appeals

engaged in judicial review of agency action does not

extend to rewriting the statute to conform to the court’s

view of the wisest policy. Compare Alexander v. Cali-

fano, 432 F. Supp. 1182, 1189, 1190 (N.D. Cal. 1977).

In fact, the Secretary of Education had already taken the

concern expressed by the panel into account in reducing the amount

of repayment which he requested to reflect the smaller pupil-teacher

ratios in Title I classes as compared to regular classes. See supra

note 18.

“One may well differ, as a matter of educational policy, with

the legislative choice to concentrate rather than spread aid among

educationally deprived children, but that is not a matter for this

Court. . . . That the enforcement of the federal requirement is likely

to have an impact on State and local programs and may require

changes in State regulations and guidelines is not a ground for

22

The panel of the Court of Appeals in the Kentucky case

erred in seeking to do this, and its judgment should be

reversed.

I ll

The Eligibility and Supplanting Restrictions at Issue in

These Cases are Directly Related and Critical to the

Purposes of the Title I Program—and the States Had

Both Ample Notice of their Applicability and Adequate

Explanation of their Requirements

Throughout the course of these proceedings, both New

Jersey and Kentucky have attempted to convey the im

pression that the eligibility and supplanting restrictions

involved in these audits interfered with the realization

of the goals of the Title I program in their states’ school

districts, and also that the Department of Education’s

interpretations of the statutory and regulatory language

were never clearly articulated and explained until the

audits had taken place. These arguments are, to some

extent, echoed in the opinions of the courts below ^ and

they may have contributed to the legal errors made by

the Third and Sixth Circuits. In fact, the substantive

requirements at issue in these cases—the determination

of school and attendance area eligibility, and the prohibi

tion against supplanting state and local resources—are

of central importance to the integrity and effectiveness

of federal compensatory education programs, which con

stitute the largest part of federal aid to elementary and

secondary education. These requirements have been a

disregarding that requirement. Nor is the wisdom of the policy to

concentrate compensatorj' education funds on a small number of

pupils a matter for the Court’s consideration.” (footnote omitted.)

*2 See, e.g., N.J. Pet. at 4a (“Congress enacted these [1978]

amendments to correct the injustice which the earlier eligibility

standards worked in areas with high concentrations of low-income

families) iemphasis supplied); Ky. Pet. at 9a (‘We are con

cerned -with . . . the requirements of section 241e(a') (3) (B) and 45

C.F.R. 116.17 h !. as those requirements were ultimately interpreted

by the Secretary" > emphasis supplied) ; supra p. ‘21. text at note

40.

23

part of the Title I and Chapter 1 programs since their

inception in 1965; the states were clearly notified of

their applicability and scope long before the expendi

tures questioned in these audits and should not have had

any difficulty in complying with them.

Eligibility. As we have noted, in order to promote

the statutory goals, expenditures of grant funds must

be targeted on discrete populations (“educationally

deprived children”). While it would be highly desirable

to assist all students in need of seiwices, limited appro

priations for the Title I program made this impossible.

Hence, the statute provided that appropriations were to

be allocated among States and school districts according

to the number of children from low-income families,^®

and that funds were granted only for programs which

would contribute to meeting the needs of educationally

deprived children in areas within school districts where

there are large concentrations of children from such

families.^^

The project area eligibility standards are linked to

the additional requirement, which was maintained

throughout all versions of the statute since Title I was

first passed in 1965, that programs must be “of suf

ficient size, scope and quality to give reasonable promise

of substantial progress toward meeting” those special

43 See 20 U.S.C. § 241c(2) (Supp. IV 1968); 20 U.S.C. § 2711(c)

(1982); see also 20 U.S.C. § 3803 (1982) [Chapter 1].

44 See 20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (1) (A) (Supp. IV 1968); 20 U.S.C.

§ 2732 (1982) ; see also 20 U.S.C. § 3805(b) (1) (A) (1982) [Chap

ter 1] ; Alexander v. Califano, 432 F. Supp. at 1189 (referring to

“the legislative choice to concentrate rather than spread aid among

educationally deprived children”). Once eligible project areas are

selected, every child determined to be educationally deprived, re

gardless of economic status, is eligible to receive services. Educa

tional deprivation is the .sole criterion for deciding which children

in a project area will participate in these federal programs.

24

needs.̂ ® The purpose of this provision is to avoid dis

sipation of federal grants by spreading them among too

many underfunded projects in too many different

schools. Because local school administrators are almost

always under intense pressure to serve as many stu

dents as p o ss ib le , th e threshold determination of eligi

ble school attendance areas facilitates compliance with the

“size, scope and quality” requirement. It is, for this rea

son, critical to the operation of successful compensatory

programs.

The importance of the eligibility standard was con

sistently emphasized by the federal government and was

well known to the Congress. For example, in 1966 the

House Committee on Education and Labor reported

amendments to the statute and commented:

The committee notes that during the first year of

operation funds have primarily been used in special

projects in schools with the highest concentrations

of children from low-income families. This is to be

encouraged especially since funds are limited and

therefore must be concentrated on the most pressing

needs.“‘’

Initial regulations which had allowed areas that did not

meet the “highest concentrations of children from low-

income families” requirement to be included in Title I

« Pub. L. No. 89-10, § 205(a) (1) (B), 79 Stat. 27, 30, reprinted

in 1965 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 29, 33 (codified at 20 U.S.C.

§ 241e(a) (1) (B) (Supp. IV 1968)); see 20 U.S.C. § 3805(b) (3)

(1982) [Chapter 1].

■*®See N.J.J.A. at 176 (New Jersey Department of Education’s

Application for Review of Final Audit Determination) (“LEA had

no choice but to assume high concentrations of low-income families

in all attendance areas and to attempt to spread the benefits of

Title I as broadly as possible to assure that most educationally

deprived children would be served”).

H.R. Rep. No. 1814, 89th Cong., 2d Sess. 3, reprinted in 1966

U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 3844, 3846.

25

programs^* were quickly amended in 1967 to remove

this option,“‘® and the change was specifically brought to

the attention of state education officials.®® Thereafter,

communications from the federal level repeatedly di

rected attention to the eligibility criteria and explained

in considerable detail how comparisons of poverty con

centrations should be made.®̂

45 C.F.R. :§ 116.17(b) (1966) provided that attendance areas

with numbers or percentages of children from low-income families

which were at least as high as the district-wide average were eligi

ble to be designated as project areas, and that “ [ojther areas with

high concentrations of children from low-income families may be

approved as project areas but only if the State agency determines

that projects to meet the most pressing needs of educationally de

prived children in areas of higher than average concentration have

been approved and adequately funded.”

The language quoted in the preceding footnote was removed by

32 Fed. Reg. 2742, 2744 (February 9, 1967) and never reappeared.

See 45 C.F.R. § 116.17(d) (1968).

Title I Program Guide No. 28, see Wheeler v. Barrera, supra

note 8, issued on February 27, 1967 to Chief State School Officers

and State Title I Coordinators by U.S. Commissioner of Education

Harold Howe, II, advised (p. 2) that:

1. The revised Title I regulations differ from the previous

regulations in two important respects regarding project

areas:

a. It is no longer permissible to designate as project areas

attendance areas with less than average concentrations

of children from low-income families.

2. The purpose of the “attendance area” requirement in Title

I is to identify the “target population” from which the

children with special needs are to be selected.

For example. Title I Program Guide No. 44, issued March 18,

1968 by Commissioner Howe to Chief State School Officers and

state Title I coordinators, collected in one document the “Revised

Criteria for the Approval of Title I, ESEA Applications from Local

Educational Agencies.” Section 1 of that document elaborated

upon the Title I regulations with practical instructions about how

26

Thus, far from creating a situation of injustice, the

eligibility restrictions were designed to insure that the

to collect data and make the necessary attendance area comparisons

to determine eligibility.

On November 20, 1968, Commissioner Howe distributed Program

Guide No. 48, entitled “Improving the Quality of Local Title I Com

pensatory Education Programs.” In that directive, the Commis

sioner emphasized the need to make wise use of the limited funds

available for effective compensatory programs:

Many Title I programs are based on the selection of individual

children from many grade levels from all of the attendance

areas which are technically eligible to be included in the Title

I program. This approach has usually resulted in programs

which are not as effective as they might be.. . .

The purpose of this memorandum is to suggest an approach to

the planning of Title I programs which can result in improved

program quality. This approach includes the following major

steps:

1. Focus resources on a number of children in the “target

population”—those in the most impoverished school attend

ance areas;

Id. at 1, 2 (emphasis in original). Finally, in the Title I Program

Guide No. 45A, issued July 31, 1969 by Associate Commissioner

Leon Lessinger, Chief State School Officers and Title I Coordinators

were advised:

Your title I, ESEA, offices are now in the process of reviewing

and approving applications for grants from the fiscal 1970 ap

propriation (advance funding). A number of State educational

agencies have already made special efforts to insure high qual

ity programs that meet all legal requirements. Information

reaching this office concerning the administration of Title I

indicates, however, that in some cases further efforts are likely

to be required if charges of noncompliance with Federal pro

gram requirements are to be avoided.

In reviewing Title I proposals the SEA should be particularly

alert to the following indications of violations of basic Title I

requirements:

1. The applicant proposes to pro\ide Title I services to chil

dren who do not reside in areas determined to be eligible

for Title I, ESEA. services.

• • • • [Continued]

27

expenditure of Title I funds actually provided some

benefits to the students who participated in the com

pensatory programs, rather than being just “a drop in

the bucket”—and the importance of these criteria was

repeatedly brought to the notice of state education

officials.®̂

Supplanting. Although the Title I statute, in its orig

inal 1965 formulation, contained no explicit “anti

supplanting” language, it did limit the use of grant

funds to projects designed to meet the “special educa

tional needs of educationally deprived children,”

which the Congress understood to incorporate the notion

that Title I expenditures should supplement local pro

grams.®̂ Accordingly, from the outset the Title I regu

lations included a prohibition against supplanting.® By

1968, six years before the Kentucky expenditures at

[Continued]

Each SEA should adopt a plan and schedule visits for moni

toring local Title I programs. In checking on local program

operations the SEA should take appropriate action if there is

any evidence indicating violations, such as the folio-wing:

1. Use of Title I funds in areas not designated as eligible Title

I areas.

®2It is not -without significance, in this connection, that the

Newark, New Jersey school system apparently had little difficulty

in correctly identifying eligible schools in the school year following

those for which the auditors noted misexpenditures. See N.J.J.A.

at 26 (Final Audit Report).

®Pub. L. No. 89-10, §2 [adding § 205(a) (1) (A) ], 79 Stat.

27, 30, reprinted in 1965 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 29, 33 (codi

fied at 20 U.S.C. § 241e(a) (1) (A) (Supp. IV 1968)).

See, e.g., I l l Cong. Rec. 7353 (daily ed., April 9, 1965) (Sen.

Morse, floor manager) (“I wish to clarify [the permitted use of

Title I funds] as a matter of legislative history. . . . The funds in

Title I must be used to help the educational needs of educationally

deprived children, not to remove any State responsibility from any

State in providing education for its children”) .

®»See45C.F.R.§ 116.17(f) (1966).

28

issue here, the regulatory language referred unmistak

ably to providing a fair share of state and local resources

to participating children, as well as project areas.^ ̂ As

in the case of eligibility criteria, federal authorities ex

plained the implications of the non-supplanting require

ment with great specificity and clarity.®^

See 45 C.F.R. § 116.17(h) (1968) :

Each application for a grant under Title I of the Act for edu

cationally deprived children residing in a project area shall

contain an assurance that the use of the grant funds will not

result in a decrease in the use for educationally deprived chil

dren residing in that project area of State or local funds which,

in the absence of funds under Title I of the Act, would be

made available for the project area and that neither the project

area nor the educationally deprived children residing therein

will otherwise he penalized in the application of State and

local funds because of such a use of funds under Title I of the

Act.

(emphasis supplied.) See also Program Guide No. 44, supra note

51, § 7.1 (“It is expected that services provided within the district

with State and local funds will be made available to all attendance

areas and to all children without discrimination”) (emphasis sup

plied).

Title I Program Guide No. 48, issued November 20, 1968 by

Commissioner Howe, explicitly covered the sort of situation which

developed in the 50 Kentucky school districts in 1974 and indicated

that a contribution of state or local funds would be required to

avoid supplanting:

3. Design a comprehensive program that will meet the most

pressing needs of each child in the priority groups, utilizing all

available local, State and Federal resources;

As indicated in item 3 above, the entire school program in the

project for the disadvantaged children involved. State and

local funds would then he used to pay for that portion of the

program which would replace the pre-existing regular school

program and Title I funds woidd he used to pay for additional

services above that level.

Id. at 2 (emphasis supplied). Separate Program Guides and memo

randa were issued by the Commissioner explaining the comparabil

ity requirement, see supra note 39 & accompanying text.

29

Nevertheless, the occurrence of supplanting was wide

spread in the early years of the Title I program, a fact

that was brought to the attention of the Congress by

both the U.S. Office of Education and outside groups.®®

As a result, in 1970 specific language prohibiting sup

planting was added to the statute itself. That language

referred to the continuation of state and local spending

“for the education of pupils participating in programs

and projects assisted under this title.” ®® While we think

that that language, standing alone, is sufficiently definite

and precise to have put Kentucky on notice of the im

propriety of the “readiness class” expenditures, see

supra p. 20, there simply could be no misunderstand

ing of its significance in light of the substantial atten

tion given to the concept throughout the history of the

Title I program. For the same reason, it is obvious that

the Secretary’s interpretation of the statutory and regu

latory non-supplanting language which was applied to

the Kentucky audit was no post hoc reading, as the

Court of Appeals seemed to suggest.®"

In both these cases, then, not only is the Secretary’s

interpretation of the statute and regulations amply sup

ported by the language and legislative history, but the

states received repeated and specific notice of that inter

pretation long before the events that produced the audit

exceptions.

See S. Rep. No. 634, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 9, reprinted in 1970

U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 2768, 2776, referring to Washington

Research Project, et al.. Title I of ESEA: Is It Helping Poor Chil

dren? (1969).

®« Pub. L. No. 91-230, § 109 (a), 84 Stat. 121, 124, reprinted in

1970 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 133, 137 (codified at 20 U.S.C.

§ 241e(a) (3) (1970)). See also supra, text at note 39.

See supra note 42.

30

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amicus respectfully sug

gests that the judgments of the Court of Appeals for

the Third and Sixth Circuits in these matters should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Fred N. F ishman

Robert H. Kapp

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

William L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin *

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 ‘Eye’ Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 371-1212

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record