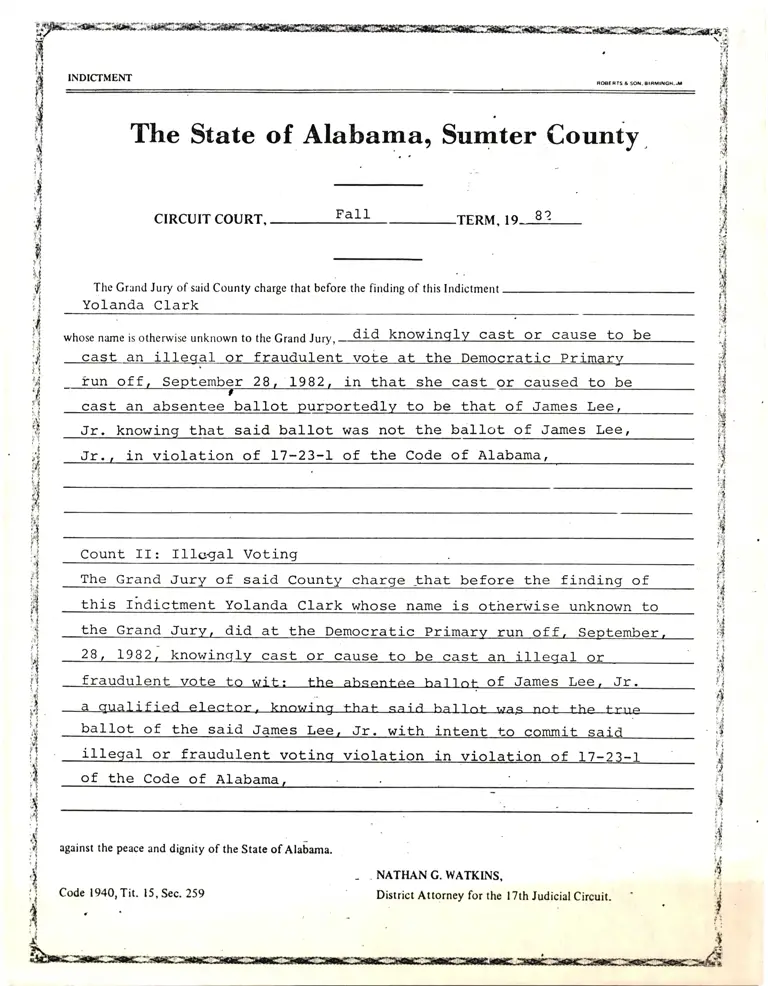

Indictment of Yolanda Clark

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1982 - January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Indictment of Yolanda Clark, 1982. 259815bc-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db10d793-d07e-4980-a2ac-e340de9e1e34/indictment-of-yolanda-clark. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

;$DJC[ r!r?

\.fi. i'i,

{. .ttiI

INDICTMENT F6EBrs&sor.erFMr'- "

:S

'!i

l..t

The State of Alahama, Sumter County i

.t;

it

t

r'l

cTRCUIT couRT, FaIl TERM, tg 82 ij

iti

,, 1\

i,

f{

ti

,J

The Grund Jury of said County charge that before the finding of this Indictment lt

iiYolanda Clark

whose name is otherwise unknown to the Grand Jury, - did knowinqly cast or cause to be

cast an illeqal or fraudulent vote at the Democratic Primary

tun off, September 28, 1982, in that she cast

cast an absentee ballot purportedlv to be that of James Lee,

Jr. knowing that said balIot. was not the ballot of James Lee,

Jr., in violation of I7-23-L of the Code of Alabama,

Count II: I1IegaI Voting

The Grand Jury of said County charge _that before the findinq of

this Indictment Yolanda Clark whose name is otherwise unknown to

the Grand Jury, did at the Democratic Primarv run off, Seotember.

28, LgB2, knowinctlv cast or cause to be cast an illeoal or

fraudulent vote to wit: the ahqonl-ao hal'l nr of James Lee, Jr-

d, qualif i e<1 e] eetor, knowi ng f haf qe i rl hall nt WaS nnt tha trUe

barlot of the said James Lee. Jr. with intent to commit said

illeqal or fraudulent votinq violation in violation of 17-23-1

of the Code of Alabama

aSainst the peace and dignity of the State of Alabama.

Code 1940, Tit. 15, Sec. 259

- " NATHAN G. WATKINS,

District Attorney for the lTth Judicial Circuit.