Williams v. Board of Supervisors of Elections of Choctaw County Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 9, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Williams v. Board of Supervisors of Elections of Choctaw County Brief of Appellants, 1974. 865e4548-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db377662-2cbf-493b-95a8-5691ac930ec9/williams-v-board-of-supervisors-of-elections-of-choctaw-county-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

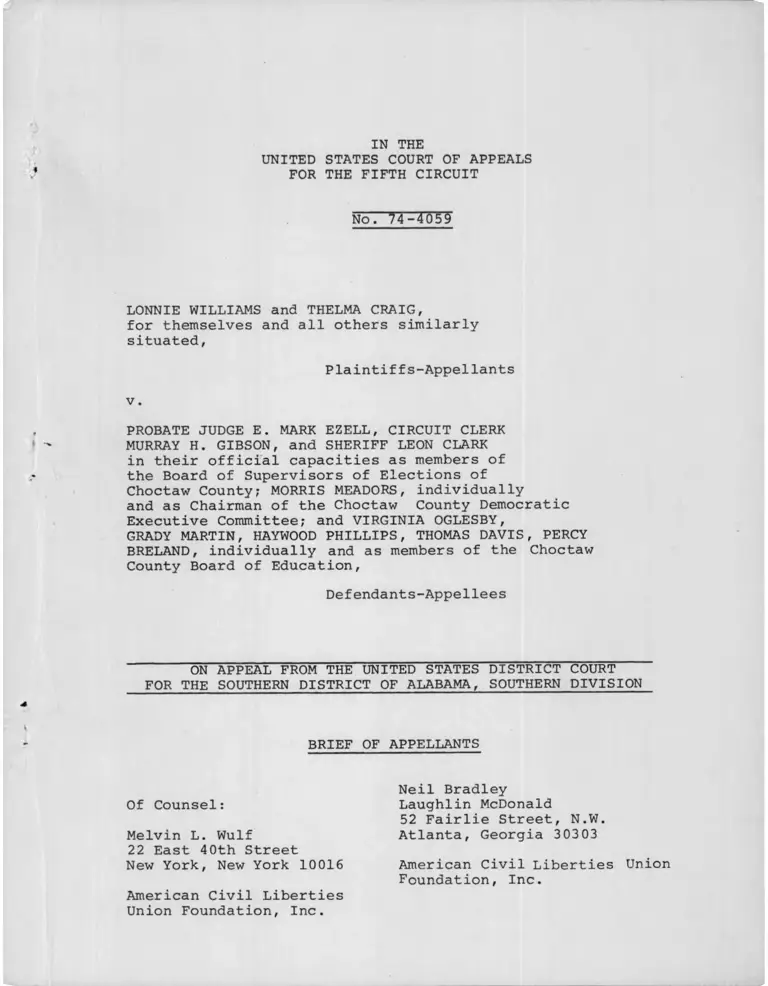

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. *74 -465$

LONNIE WILLIAMS and THELMA CRAIG,

for themselves and all others similarly

situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v

PROBATE JUDGE E. MARK EZELL, CIRCUIT CLERK

MURRAY H. GIBSON, and SHERIFF LEON CLARK

in their official capacities as members of

the Board of Supervisors of Elections of

Choctaw County; MORRIS MEADORS, individually

and as Chairman of the Choctaw County Democratic

Executive Committee; and VIRGINIA OGLESBY,

GRADY MARTIN, HAYWOOD PHILLIPS, THOMAS DAVIS, PERCY

BRELAND, individually and as members of the Choctaw

County Board of Education,

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, SOUTHERN DIVISION

Defendants-Appellees

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Melvin L. Wulf

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

Of Counsel:

Neil Bradley

Laughlin McDonald

52 Fairlie Street, N.W

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation, Inc.

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 74-4059

LONNIE WILLIAMS and THELMA CRAIG,

for themselves and all others similarly

situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

PROBATE JUDGE E. MARK EZELL, CIRCUIT CLERK

MURRAY H. GIBSON, and SHERIFF LEON CLARK

in their official capacities as members of

the Board of Supervisors of Elections of

Choctaw County; MORRIS MEADORS, individually

and as Chairman of Choctaw County Democratic

Executive Committee; and VIRGINIA OGLESBY,

GRADY MARTIN, HAYWOOD PHILLIPS, THOMAS DAVIS, PERCY

BRELAND, individually and as members of the Choctaw

County Board of Education,

Defendants-Appellees

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED by FIFTH CIRCUIT

LOCAL RULE 13(a):

The undersigned, counsel of record for appellants,

certifies that the following listed parties have an in

terest in the outcome of this case. These representations

are made in order that Judges of this Court may evaluate

possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to Local Rule

13(a).

All Parties listed in Title of Case

J. Edward Thorton

John Y. Christopher

Jack Drake

Ralph I. Knowles, Jr.

W.E. Still, Jr.American Friends Service Committee

-i-

Western Surety Company

American Civil Liberties Union Foundation, Inc.

Neil Bradley ' :

Attorney of Record for Appellants

-ii-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Rule 13(a) Certificate .................... ^

Table of Authorities..................

Issues Presented for Review ................ 1

Statement of the C a s e ...................... 3

Statement of Facts ........................ 5

Argument

S u m m a r y ........................ 1

The Brodhead C a s e ............. .. 17

The Litigation Was a Reasonable

Apportionment Suit Necessarily Brought to Vindicate the Rights of Black

Electors in Choctaw County ............ 21

Defendants Were Not Entitled to

an Award of Attorneys' Fees Under

Applicable Law on the Facts Presented 29

Awarding Attorneys' Fees to Defendants

Has a Deterrent Effect in Direct Conflict With Public Policy... 33

Conclusion................. 35

Addendum

Act 454, 1951 Acts of Alabama . . . 1

42 U.S.C. §1971 2

42 U.S.C. §1983 8

42 U.S.C. §2000a— 3 ( b )..... g

-iii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

American Cyanamid Co. v. McGhee, 317 F.2d 295

(5th Cir. 1963) ......................

Avery v. Midland County, Texas, 390 U.S. 474

(1968) ................................

Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Richmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965)

(en banc) ............................

Brodhead v. Ezell, 348 F. Supp. 1244 (S.D.

Ala. 1972) ............................

Byram Concretanks, Inc. v. Warren Concrete

Products Co., 374 F .2d 649 (3rd Cir.

1967) ................................

Davis v. United States, 422 F.2d 1139 (5th

Cir. 1970) ............................

Dusch v. Davis, 387 U.S. 112 (1967) . . . . .

Hall v. Cole, 462 F.2d 777 (2nd Cir. 1972),

412 U.S. 1 (1973) ....................

Harvey Aluminum v. American Cyanamid Co., 203

F.2d 105 (2nd Cir. 1953) cert. den. 345

U.S. 964 (1953) ......................

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974) ..................

Keller v. Gilliam, 454 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1972)

Lee v. Southern Home Cites Corp., 444 F.2d

14 1 / C i.t 1 Qn*t \jlij Cjll - _L -/ / «L / 5 s * * « - - ; „ *

Long v. Georgia Kraft Co., 455 F.2d 331

(5th Cir. 1972) ......................

19, 21

29

passim

33

34

22

32, 35

25

12, 29

20, 22

*■% ̂n

30

25

-iv-

Table of Authorities (cont'd)

MacGuire v. Amos, 343 F. Supp. 119 (M.D. Ala.

1972) (three-judge court) ............. 23

McGill v. Ryals, 253 F. Supp. 374 (M.D. Ala.

1966)(three-judge court) .............. 23

Medders v. Autauga County, ___ F. Supp.

(M.D. Ala. 1973) (No. 3805-N, Feb. iT T

1973) 19, 21

Miller v. Reddin, 422 F.2d 1264 (9th Cir.

1970) .......... ...................... 25

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S.

375 (1970)............................ 30

Morris v. Sullivan, 497 F.2d 544 (5th Cir.

1974) ................................ 23

NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala.

1972) ................................ 35

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S.

400 (1968)............................ 30

Nix v. Fulton Lodge No. 2, 452 F.2d 794 (5th

Cir. 1971) cert, den. 406 U.S. 946 (1972) 25

Peters v. Clark, 508 F.2d 267 (5th Cir. 1975) 20, 22

Plains Growers, Inc. v. Ickes-Braun Glass

houses, Inc., 474 F .2d 250 (5th Cir.

1973) ................................ 25

Reese v. Dallas County, Alabama, 505 F.2d 879

(5th Cir. 1974) (en banc), reversing, ___

F. Supp. ___ (S.D. Ala. 1973)(No. 7503-

7 3 - H ) ................................ 20, 22

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) . . . . 17

-v-

Table of Authorities (cont'd)

Richardson v. Hotel Corporation of America,

332 F. Supp. 519 (E.D. La. 1971), aff'd

468 F . 2d 951 (5th Cir. 1972).......... 32

Sailors v. Board of Education of County of

Kent, 390 U.S. 105 (1967) ............ 19, 21

Salyer Land Co. v. Tulare Lake Water Storage

Dist., 410 U.S. 719 (1973)............ 22

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir.

1 9 * 8 ) ................................... 35

Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala.

1972) (three-judge court) aff'd 409 U.S.

942 (1972)............................... 31

Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307 U.S.

161 (1939)............................... 29

Trustees v. Greencugh, 105 U.S. 527 (1882) 29

Weight Watchers of Philadelphia, Inc. v.

Weight Watchers International, Inc., 455

F . 2d 770 (2nd Cir. 1972).............. 26

Wilderness Society v.* Morton, 494 F.2d 1026

(D.C. Cir. 1974) cert, granted No. 73-

1977, 43 U.S.L.W. 3208 ................ 33

Yelverton v. Driggers, 370 F. Supp. 612 (M.D.

Ala. 1974)............................ 12, 32

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F .2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973) (en banc)........................ 19, 20

-vi

Constitutional Provisions

Fourteenth Amendment ...................... 1 , 2 , 6

Fifteenth Amendment ...................... 1 , 2 , 6

Statutes and Rules

Act 454, 1951 Acts of Alabama.............. 5, 23

28 U.S.C. §1331............................; 6

28 U.S.C. §1343 ...................... .. 6

28 U.S.C. §2201 ............................ 6

28 U.S.C. §2202 ............................ 6

42 U.S.C. §1971 ................. . . . . . 1, 6

42 U.S.C. §1983............................ 1, 6

42 U.S.C. § 2 0 0 0 a ........................ . 32

42 U.S.C. §2000a— 3 (b) .................... 12, 13, 30, 32

42 U.S.C. §2000e— 5 (k) .................... 30

Title 52, §62, et seq., Code of Alabama . . . 19

F. R. Civ. P.

Rule 23 (c) (1)............................ 26

Rule 23 (c) ( 3)............................ 26

Rule 23(e) .............................. 26

Rule 41 (a) (1)............................ 24, 25

Table of Authorities (cont'd)

• «-vxi-

F. R. Civ. P.

Rule 55 ............ • • • • • • • • •

Rule 66 ..........

Other Authorities

Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure

Civil §2363, p. 157 ..............

Table of Authorities (cont'd)

-viii-

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

I. Whether in an action brought under §§1971 and

1983, Title 42, United States Code, and the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments of the

Constitution of the United States alleging denial

of equal protection and the submergence of black

electors' voting strength in the apportionment of a county

school board, attorneys' fees and expenses may be

taxed against unsuccessful plaintiffs?

II. Whether there is any authority, statutory or judicial,

permitting the award of attorneys' fees and expenses

to a county school board in an action brought under the

civil rights acts involved here?

III. Whether there is any public policy supporting the awarding

of attorneys' fees and expenses to a county school

board in an action brought under civil rights acts?

IV. Whether in an action brought under §§1971 and 1983,

Title 42, United States Code, and the fourteenth and

fifteenth amendments of the Constitution of the United

States alleging denial of equal protection and the

submergence of black electors voting strength in the

the apportionment of a county school board, the

award of attorneys' fees and expenses against the

plaintiff is a deterrent to the bringing of such

actions and consequently in conflict

-1-

with congressionally designated national policy?

V. Whether the evidence in this case shows the seeking

and awarding of attorneys' fees and expenses

against the plaintiffs were intended to and/or has the

effect of deterring suits brought to vindicate

rights guaranteed by civil rights acts and the fourteenth

and fifteenth amendments of the Constitution of the

United States?

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This action was instituted on March 14, 1974,

seeking to reapportion the Choctaw County, Alabama,

Board of Education. The relief sought was to have

plaintiff Williams certified as a candidate, a primary

was to be held in early May, and to permanently enjoin

the existing apportionment of the board.

An emergency hearing was held on March 26,. 197 4,

and, over plaintiffs' objection to consideration of

permanent relief, the court two days later denied

all relief, dismissed the complaint, and ordered costs taxed

againfet plaintiffs.

Plaintiffs filed a motion for rehearing on April 1,

1974, and after oral argument the court, on June 5,

1974, set aside its order denying permanent relief and

set pre-trial for July 31, 1974, ordering discovery

completed by July 20, 1974. Pretrial was later

reset for July 29, 1974.

On July 25, 1974, plaintiffs filed a motion for

dismissal without prejudice. The court then denied the

4- "l /-\ n r» n i i c f» t.t i t- n A iif r> ■v* a i n n i a q a a ri »• a i a nf-n ̂ a a ^ a a

w \ y v * u t u j k >_i u n j u u * a w m w £✓ j _ v _ j u m X U C w a i U U U L C U L i i C

terms of its order of March 28, 1974.

On August 14, 1975, defendants filed a bill of

costs listing $20.00 docket fee and $1,895 for attorneys'

fees and expenses. The clerk declined to tax attorneys'

fees and expenses, noting on the bill of costs, "Not

3

taxable as item of costs under court's order of 7/31/74

but counsel for defendants may petition court for awarding

of attorney's fees in this matter." Defendants thereafter,

on August 20, 1974, filed a motion praying that the court

award them $1,895 in fees and expenses. Plaintiffs

served by mail on August 22, 1974 , an opposition to that

motion and it was stamped filed by the clerk on Auqust 26,

1974. A month later on September 26, 1974,idefendants filed

a memorandum in support of their motion in response to

plaintiffs' opposition.

The court, on October 1, 1974, entered an order

granting the motion. The order recited that the amount

of the fee would be determined by the court unless agreed

on by the parties.

On the date the order was entered, plaintiffs served

by mail a response to defendants' memorandum. This was

not filed by the clerk until October 3, 1974, two days

after the order. On October 9, 1975, plaintiffs filed

a memorandum in opposition to award of attorneys' fees

with supporting affidavit. On that date a hearing was

held and the court entered an order setting the attorneys'

fee at $2500.

Notice of appeal was filed by the plaintiffs

on November 6, 1974, appealing from the orders of

of October 1 and October 9, 1974, granting the award

of attorneys' fees to defendants and setting the fee.

4

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The Choctaw County, Alabama, Board of Education

is composed of five members, all of whom are elected at-

large by the entire county. Four members must be residents

of four separate districts and the fifth may reside anywhere

in the county. This structure is established by §1, Act 454,

1951 Acts of Alabama. Add. 1. The four districts are

established by the following language:

One member of the Board of Education

of Choctaw County shall be elected for each of

the four commissioner's districts into which

the county is now divided, I I !

(Empha sis added.)

The commission districts referred to and incorporated a~e the

county commission districts. County Commissioners were

elected by district, not at-large, and those districts

were declared violative of the one-man one-vote principle

in Brodhead v. Ezell, 348 F. Supp. 1244 (S.D. Ala. 1972),

per Judge Pittman.

On February 27., 1974, plaintiff Lonnie Williams

attempted to qualify in the Democratic Primary for place

4 of the Board, but he resided in the new district 4 under

Judge Pittman's order and not in the old district 4 established

in 1951. (Defendant's exhibit 1.) Williams

5

was under the impression that Judge Pittman's order covered

the board districts (R85). On March 11, 1974, the county

Democratic executive committee chairman refused to certify

Williams' candidacy to the probate judge. (Defendant's

exhibit 2.) The reason for failure to certify was Williams'

residence outside the old district 4.

Three days later Williams and Thelma Craig instituted

this suit seeking to represent the class of similarly

situated citizens in Choctaw County who because of the

electoral structure were alleged to be deprived of an

equal ballot and the opportunity to qualify in Board

elections (Rl, 2). Named as defendants were the election

officials, chairman of the county Democratic executive

committee, and members of the Board (R2). Plaintiffs alleged

that the use of the at-large, majoritarian system discriminated

against black voters by submerging their voting strength.

The relief sought was to have Williams certified as a candidate,

an injunction prohibiting the use of the existing electoral

structure, and consideration of a single member district

plan or proportional representation. Plaintiffs also

sought a reasonable attorneys' fee (R4-5).

Jurisdiction was based on the fourteenth ana fifteenth

amendments of the Constitution of the United States, 28

U.S.C. §§1331, 1343 2201 and 2202, 42 U.S.C. §§1971 and

1983 (Rl).

6

On the date suit was filed counsel for all parties

were heard in chambers as to the granting of emergency re

lief (R64, 68, 75). The court desired that the parties

attempt to come to agreement (R 69, 70 ), and failing this

the matter was set for a hearing on March 26, 1974.

The parties and court discussed the applicability of

the Brodhead case (generally R61-76). The district judge

recalled that he expressed the opinion that if Brodhead

were applicable and did fit the facts of this case that he

would follow the lead of Judge Pittman (R69).

The hearing notice stated that it was to be on tempo

rary and permanent relief (R66). Plaintiffs objected to the

consideration of permanent relief (R92). There is dispute

in the record as to plaintiffs' efforts to advise the trial

judge that they did not desire permanent relief be considered

on such emergency basis (R67, 70-71).

At the March 26, 1974 hearing, the only witnesses were

the two named plaintiffs who testified as to the facts of

WiHi-ams attempt to qualify and generally their standing

to bring suit. Two days later the court entered its order

denying all relief (R8-14).

The court distinguished Brodhead as involving a govern

mental body whose members had administrative duties for

Particular parts of the county and general governmental

powers, whereas the school board "does not operate as a

quasi-governmental function but is charged with the admini

strative detail of the county school system which has county

wide application" (Rll). The court found that there was no

basis offered to find Act 454 unconstitutional nor uncon

stitutionally applied under the fourteenth amendment (R12).

This is not an instance in which voters in

sparsely populated areas elect their officials

to a unit of government while voters in highly

populated areas elect the same number of offi

cials to the same unit. All members of the

Board are elected at-large, thus the fundamental

principal of representative government is ful

filled in that each member's tenure is dependent

upon the vote of all qualified voters. Such a

scheme does not violate the one man one vote

principle. Dusch, et al. v. Davis, et al., 387

U.S. 112, 87 S.Ct. 1554, 18 L.Ed.2d 656. Since

are elected at—large, the right of each voter

in Choctaw County is given equal treatment.

Dusch. /. Davis, supra, Davis v. Thomas County,

Georgia, et al., 380 F.2d 93; Goldblatt v. Citv

of_Dallas, 414 F.2d 774; Hadley v. Junior College

^̂ -strict Metropolitan Kansas City, Missouri

397 U.S. 50, 90 S.Ct. 791, 25 L.Ed.2d 45.(R12)

Thelma Craig is neither disfranchised by the re-

quired election process nor is her vote diluted

as compared with any other voter in the county.

Lonnie Williams is not precluded from running for

a position as a member of the Choctaw County

School Board but is required to run in that elec-

tion open for residents of his delineated school

district. This Court is not a super legislature,nor wi. 1 1 t accnmo ~ -i- — -» — —1- i----- -

— ^ 1 w i i u v , y w o u u i . c u . n u i . i j i i t -M : r-y ii_ i_ g m w i u [| u

citizen disagrees with a law. This Court is

jealous to protect the Constitutional rights of

all citizens and will move promptly where such are

threatened, but none such is present here.

8

As found by Judge_Pittman in the Brodhead case,

the districting lines employed in Choctaw County

axe more than a century old and there is no basis

for any finding that they were established for

racial reasons for they essentially divide the

county into four equal quarters and always have.

There is no basis to indulge a presumption that

they have suddenly become racially motivated

boundaries or that there is any subjugation of

the black voters interests. Since it is apparent

that each vote by each citizen of Choctaw County

carries the same and equal weight in the election

of members of the school commission, the require

ments of this republican form of government as

established and protected by the Constitution are

fulfilled and no relief, injunctive or otherwise,

is indicated in the premises.

For the reasons herein expressed the petition for

temporary injunction is DENIED; the petition for

permanent injunction is DENIED and this Court sees

no basis for continued jurisdiction of the remain-

ing prayer for relief; therefore, the cause is

DISMISSED, costs taxed to the plaintiffs.(R13-14)

Plaintiffs filed a motion for rehearing (R18-20), alleging

that they had relied on the Brodhead case for its findings

that the former commission districts discriminated in viola

tion of the equal protection clause. Since the order of the

court recited that no evidence of racial discrimination was

introduced plaintiffs sought the opportunity to prove this

element. The court ordered a hearing on May 2, 1974, on the

motion. At the hearing all counsel and the court were in

disagreement as to what had transpired in the meeting in

chambers regarding what plaintiffs sought and what the effect

of Brodhead was to be.

On June 5, 1974, the court entered an order granting

9

plaintiffs' motion in part:

[I]t is the opinion of the Court that the matters

and things stated by the plaintiffs' attorney as

grounds and reasons for a rehearing are not in

accordance with this Court's understanding of

the proceedings leading up to the Order of this

Court of March 28, 1974, and the same are totally

rejected. However, in order that the actions of

this Court nor the actions of counsel for the

plaintiffs might be considered as having deprived

the plaintiffs of their day in Court, the Court

will grant so much of the request of plaintiffs'

attorney that the Order denying the permanent

injunction be set aside and that this matter pro

ceed for a hearing on so much of the petition

wherein it is requested that the Court hold hear

ings that a system of single member districts

should be ordered for the election of the Choctaw

County Board of Education.(R22)

The order of the court concluded setting the pretrial for

July 31, 1974. An apparently standard pretrial order was

entered on June 28, 1974 (R24-27) which reset the pretrial

to July 29, 1974. The pretrial order directed the consulta

tion among counsel for the preparation of a proposed pretrial

order to be in the hands of the court one full week before

the pretrial hearing. The order encouraged attempted settle

ments, and included the following:

Failure of strict compliance with this Order in

the form and under the terms contained herein shall

automatically result in the offending party being

held in contempt, and such contempt shall continue

from day to day until the Order has been complied

with- Failure to comply within a period of five

days thereafter, and explanation satisfactory to

the Court not having been given and accepted shall

result in the cause being dismissed or default

judgment being entered whichever is appropriate. (R27)

10

Thereafter, on July 25, 1974, plaintiffs filed a motion

for dismissal which read: "Come now the Plaintiffs and move

the Court to dismiss this action without prejudice to any

party." (R28) The court disposed of the matter in the

following language:

On the occasion of the Pretrial Conference it

was called to the attention of the Court that the

plaintiffs had filed a Motion to Dismiss, without

prejudice, on the 25th day of July, 1974. The

requirements of the Pretrial Order issued on

June 28, 1974 not having been complied with and

this Court having been afforded no reason why the

plaintiffs should have been excused from these

requirements, and indeed the plaintiffs having

made no contact with the Court concerning the

Pretrial Conference nor the filing of the Motion

to Dismiss, without prejudice, and this Court

having previously entered an Order on the 28th

day of March, 1974 disposing of the issue in its

entirety and the matter not having been further

prosecuted by the plaintiffs, the Motion to Dismiss,

without prejudice, is therefore DENIED and this

cause stands disposed of under the terms and con

ditions of the Order entered on the 28th day of

March, 1974, the same hereby being reinstated for

want of further prosecution by the plaintiffs.

Costs of these proceedings are to be taxed to the

plaintiffs. (R29-30)

After the clerk denied the bill of costs for attorneys'

fees, defendants filed a motion therefore on August 20, 1974

(R31-32). The motion recited that "[t]his was a class action

against these- Defendants, and others, to vindicate alleged

civil rights," that defendants were the "prevailing parties,"

that "counsel, after considering the criteria set out in

11

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d 714 (C.A. 5th

1974) billed these defendants for such services a reasonable

fee and expenses, aggregating $1,895.00, which sum has been

paid" (R31). Plaintiffs opposed the motion on the grounds

that "Defendants have failed to show any statute or court

decision which entitles them to the award of attorney's

fees. . (R33). Plaintiffs further prayed the court "to

dismiss this Motion as insufficient or to place the Motion

on motion docket for briefing, argument, and evidence" (R33).

Defendants filed a memorandum on September 26, 1974,

citing 42 U.S.C. §2000a--3(b) and Yelverton v. Driggers,

370 F. Supp. 612 (M.D. Ala. 1974), as authority for the

award. The memorandum concluded:

If cases reapportioning election districts are

under this statute to award attorneys fees for

those wrecking State election laws, then cer

tainly this case which saved the State election

laws is under this statute, and attorneys fees are required here.

On May 15, 1974, the Supreme Court of the United

States in Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 40

L.Ed.2d 476^ in an odd application of retroactivity

to an Act of Congress, held school boards liable

for attorneys fees in integration suits. Concern

ing this, Jack Greenberg, attorney for the NAACP

Legal Defense Fund was quoted in the Mobile Register of May 16, 1974:

"School boards, I would hope, would not be

so free and easy to litigate if they know

it's going to cost them something."

12

We agree with Mr. Greenberg, and request this

Court to apply it in this case.(R37)

The court granted the motion insofar as entitlement to a

fee on October 1, 1974, with the amount of the fee to be

agreed upon or set by the court (R35). On October 3, 1974,

plaintiffs filed a response served by mail on October 1,

to defendant's memorandum arguing that 42 U.S.C. §2000a— 3(b)

had no application here (R38).

On the date of the hearing on the amount of the fee,

plaintiffs filed a further memorandum in opposition to the

award (R40) and attached an affidavit of plaintiffs' counsel

reciting the considerations of the motion to dismiss. The

attorney recited that in his judgment the case could not be

won before the trial judge and could probably not be reversed.

The reasons for his opinion were the judge had already decided

the case once and human nature operates against a change in

position; he believed the judge was prejudiced against the

case and the attorney because he had accused the attorney

of trying to mount a revolution in Choctaw County through

his potential proposal of a system of proportional represen-

t * a 4* 1 n n • n o r \ o ” -I o t t o o n o - i i i / i « « * • * »< -• ~ ^ ^ a ~ J _ __ i _ 1 ■*~ ^ v wu uuu j uvayc vyuo picj Uux^cQ ctgclinJDL. ail

civil rights actions because when the attorney told him he

13

was seeking a temporary restraining order or preliminary

injunction, the judge grimaced and said the clerk sent him

all these cases; the hearing for reinstatement had degener

ated into a swearing contest between the judge and the

attorney about efforts to contact each other by phone (R44-45)

At the hearing the defendants' attorney, J. Edward

Thornton, testified as to his expenses, fees, and those of

co-counsel John Christopher. Records of time and expenses

were introduced. A Mobile attorney testified as to customary

fees in the area for the work done (R96-102), and in his

opinion $50/hour was reasonable. Thornton set his fee at

$30/hour and Christopher at $25/hour (R98). Mr. Thornton

then argued to the court:

The right to a fee seems to be fairly well fixed.

The charges we actually made are below what would

be a reasonable fee. We would think twenty-five

hundred three thousand dollars would be an appro

priate allowance in this case, and this we hope Your Honor will agree with us on (R103).

[W]e had assumed that quite possibly there would

be no contest of the facts that the fee had been

paid and what was actually paid was reasonable,

and we were willing to proceed on that basis in

view of the fact that it became necessary to es

tablish this we feel that the appropriate fee

would be at a $50.00 an hour basis, and that is

substantially in excess of that which is set in

i 11 i r ih m t i r^n

(R103-04)

14

The court then noted that it had already determined that a

fee was to be allowed (R105).

However, this Court does want to correct a couple

of apparent misconceptions by the attorney re

presenting the plaintiff, as contained in the

^ffidavit and particularly those things set forth m paragraph C thereof. This Court, I do not

believe, made any reply that the assignment of

the docket to this Judge was the fault of the

Clerk. The Clerk does what the Clerk is instruct

ed to do. The Court will not deny that it probab

ly did grimace when the preliminary injunction was

brought to the Court's attention, but not because

it was of a civil rights nature, but because this

this Judge seems to have a plethora of

injunction type actions that are brought to its

attention. And it is a standing joke in this

^ ® 9 rict between the Clerk's Office, Judge Pittman's Office, and my office as to who gets what assign

ments. But it is nothing more than that. There

fore, I do not want this record to reflect that the

Court itself has any fault to find with the opera

tion of the Clerk's office or in the assignment

cases and to disabuse counsel's mind that

this Court does have some fault to find with that.

As to the other matters raised, I think the record

in this case will reflect what actually transpired.

The Court will award the attorney's fees and will

allow the petitioner $2,500.00 in the way of attor

ney s fees. The Clerk will draw an order according-

(R105-06)

15

ARGUMENT

Summary

This is a case of first impression. Two named plain

tiffs who initiated a civil rights action seeking to repre

sent a class of blacks had judgment entered against them for

$2,500 in attorneys' fees and expenses when they were not

successful. No reasons or authority were assigned therefore

by the district court.

The suit was filed to reapportionment a school board.

In the same county a similar suit had been successful in

reapportioning commission districts which used the same

lines as the school board. Plaintiffs eventually sought to

dismiss their complaint without prejudice. The district

court refused to allow this and dismissed with prejudice

and awarded attorneys' fees against plaintiffs.-

it is the award and setting of fees which is on appeal,

not the dismissal. However, in order to argue the propriety

of the award the litigation below must be discussed herein.

Plaintiffs will araue that S U "i TaJP Q r^r*r^T^or* 1 \ r Kr*nn/^Vi4-

-* - 1Z —’ E"" — / — . W | W11W* W

the denial of dismissal without prejudice was unjustified,

and that concomitantly the award of attorneys' fees was

16

unjustified, not authorized by statute or equitable con

siderations, and was in fact intended to deter and will

have the effect of deterring suits brought to vindicate

rights guaranteed by the fourteenth and fifteenth amend

ments of the Constitution of the United States.

The Brodhead Case

To understand the underlying reapportionment case, its

companion, Brodhead v. Ezell, 348 F. Supp. 1244 (S.D. Ala.

1972) , must be compared. Brodhead was filed by citizens

seeking to apply Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964),

principles to the Choctaw County Commiss.i or. The

Commission had four districts ranging in population

from 3,100 to 5,138 persons, 348 F. Supp. at 1246, with a

variation of 47 percent. Election was by district, not

at-large. Thelma Craig, plaintiff herein, was an intervenor

in Brodhead seeking to represent the class of black

electors. 348 F.Supp. at 1245. The plaintiffs sought

at-large elections, a prayer which intervenors adopted,

but the two classes later split — the intervenors, Craig

included, offered a single-member plan. 348 F. Supp.

at 1249. The Brodhead court said:

17

This court finds that those portions

of Act 122 establishing the four commissioner

districts complained of fail to satisfy

the requirements of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Constitution and are therefore null and void.

348 F. Supp. at 1248.

Further, the court in its remedy ordered, adjudged and

decreed the apportionment by Act 122 for the commission

unconstitutional and void. 348 F. Supp. 1252.

Because the act, involved here adopted the commission

districts in existence in 1951 for the school board, the

board's districts were unaffected by the Birodhead judgment.

The difference between the structures was that the board

districts were for residence only, with election by the county

at-large. The district court here disposed of the Brodhead

consideration in its order of March 28, 1974 (R8-14).

Its treatment of Brodhead is revealing. It found that Craig

had asked for at-large elections in Brodhead but not

here (RIO-11). The court found this "strange" (R12).

To the contrary, Craig and the class asked for single-

member districts and while their plan was not accepted,

the court accepted the commissioner/defendants single-member

plan. The court found the "school board here does not operate

^ s u c[Ho. 3 x —ĉ overnirienuai £ uncuion iDuti is charged with the

administrative detail of the county school system which

18

has county-wide application" (Rll). "In Brodhead the Court

was addressing itself to the election of persons having

general governmental powers and here the school board mem

bers do not" (R12). This effort to distinguish the powers

of the governing body from Avery v. Midland County, Texas,

390 U.S. 474 (1968), was not accurate. The broad powers of

Alabama school boards, Tit. 52, §62, et seq., Code of Ala

bama, leave no doubt -that they fall under the Reynolds v.

Sims requirements. Compare, Avery v. Midland County, Texas,

390 U.S. at 476; Cf_. Sailors v. Board of Education of the

County of Kent, 387 U.S. 105 (1967) (since board was "admin

istrative", its appointive selection method was constitu

tional) . Absent some special circumstances not present

here, elected school boards have been held to be under the

one-man one-vote rule. E.g_. , Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d

1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc); Medders v. Autauga County,

___ F. Supp. ___ (M.D. Ala. 1973) (No. 3805-N, Feb. 22, 1973).

Incredibly, the court here found that;

In Brodhead the Court did not find the Act of the

Legislature unconstitutional, but did find that

as applied it was violative of the 14th amendment

in that it subverted the one man one vote rule

(R12).

19

See, discussion supra, for the Brodhead holding.

Also,

As found by Judge Pittman in the Brodhead case,

the districting lines employed in Choctaw County

are more than a century old and there is no

basis for any finding that they were established

for racial reasons ... There is no basis to in

dulge a presumption that they have suddenly become

racially motivated boundaries or that there is

any subjugation of the black voters' interests

(R13).

Of course population shifts over a century could result in

vote dilution and Brodhead found that dilution to exist,

and found specifically, "Tô order the County Commissioners

to run at-large would effectively deny the sizeable black

minority a political voice." 348 F. Supp. at 1251. (Empha

sis added.)

In disposing of the case, the district court did not

cite Keller v. Gilliam, 454 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1972), or

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F .2d 1297, 1305 (5th Cir. 1973) (en

banc). More importantly neither the court nor counsel had

benefit of Reese v. Dallas County, Alabama, 505 F.2d 879

(5th Cir. 1974) (en banc); followed, Peters v. Clark, 508 F.2d

267 (5th Cir. 1975).

20

THE LITIGATION WAS A REASONABLE

APPORTIONMENT SUIT NECESSARILY

BROUGHT TO VINDICATE THE RIGHTS

OF BLACK ELECTORS IN CHOCTAW COUNTY

The purpose of this section is not to argue the decision

on the merits of apportionment, for that was not appealed.

It is to show that plaintiffs did nothing to justify the

punitive award of fees against them. %

A. The Litigation Had Merit.

The district lines attacked had been held by Brodhead

v - Ezell, 348 F. Supp. 1244 (S.D. Ala. 1972) to violate the

equal protection clause. More importantly Brodhead held

that at-large elections in the county woald deny a political

voice to the sizeable black minority. 348 F. Supp. at 1251.

Reliance on the Brodhead decision, a decision from that dis

trict pertaining to that county was well placed.

The one-man one-vote principle was more than fairly

alleged to apply to the elected school board under case law.

Avery v. Midland County, Texas. 390 U.S. 474 (1968); Medders

v. Autauga County, ___ F. Supp. ___ (M.D. Ala. 1973) (No.

3805-N, Feb. 22, 1973). There were not present any special

non-elective factors such as found present in Sailors v.

21

Board of Education of the County of Kent, 390 U.S. 105 (1967),

or Salyer Land Co. v. Tulare Lake Water Storage Dist., 410 U.S.

719 (1973).

Plaintiffs challenged an at—large electoral structure

w^t*1 residential districts. The constitutionality of such

plans were not clear, Dusch v. Davis, 387 U.S. 112 (1967),

S i - ’ Keller v. Gilliam, 454 F .2d 55 (5th Cir. 1972)^ but in

light of the Brodhead findings, the challenge was well taken.

At the time suit was filed, Reese v. Dallas County, Alabama,

505 F .2d 879 (5th Cir. 1974) (en banc), had not reached this

court although it had been decided by the district court (by

the same judge as here) adverse to plaintiffs' position.

Reese v. Dallas County, Alabama, ___F. Supp. ____ (S.D. Ala.

1973) (No. 7503-73-H, Oct.3, 1973). In fact, part of the

opinion of the district court here tracked the district court

opinion in Reese. Ibid., p. 3. Peters v. Clark, 508 F.2d

267 (5th Cir. 1975), had been under consideration by this

court for almost two years. Moreover, both Reese and Peters

did not concern racial vote dilution by at-large/residential

districts.

At the very worst, in seeking to dismiss their case

22

plaintiffs made a miscalculation of law, more particularly,

how the law would develop. Morris v. Sullivan, 497 F.2d 544,

546 (5th Cir. 1974).

B* The Litigation Was Not Unduly Delayed.

Suit was filed within three days after Williams was

notified that his qualification was not being certified to

the probate judge to be placed on the ballot. (Defendants'

exhibit 2.) The mistake was in believing Brodhead had the

effect of voiding the district lines for all purposes. How

ever, the board statute, Act 454, 1951 Acts of Alabama,

adopted the commissioner districts "into which the county

is. now divided, i.- » in 195i, nut as the districts may from

time to time be altered. The county Democratic Executive

Committee chairman recognized the problem and the source

thereof, and consulted attorneys before his refusal to certi

fy Williams. (Defendants' exhibit 2.) Williams made an

understandable mistake (R83-85), and filed suit as soon as

could be expected. Cf. McGill v. Ryals, 253 F. Supp. 374

(M.D. Ala. 1966)(three-judge court); MacGuire v. Amos, 343

F. Supp. 119 (M.D. Ala. 1972) (three-judge court).

23

c. Plaintiffs Were Entitled, to a Dismissal Without Prejudice

as a Matter of Law.

Plaintiffs' motion for dismissal without prejudice (R28) ,

was filed on July 25, 1974. At this time no responsive

pleading had been filed by any defendant. Indeed, none ever

was. Rule 41(a)(1), F. R. Civ. P. reads as follows:

(a) Voluntary Dismissal: Effect Thereof.

(1) By Plaintiff; by Stipulation. Subject to

the provisions of Rule 23(e), of Rule 66, and of

any statute of the United States, an action may

be dismissed by the plaintiff without order of

court (i) by filing a notice of dismissal at any

time before service by the adverse party of an

answer or of a motion for summary judgment, which

ever first occurs, or (ii) by filing a stipulation

of dismissal signed by all parties who have appeared

in the action. Unlers otherwise stated in the no

tice of dismissal or stipulation, the dismissal is

without prejudice, except that a notice of dismissal

operates as an adjudication upon the merits when

filed by a plaintiff who has once dismissed in

any court of the United States or of any state an

action based on or including the same claim.

The dismissal is automatically without prejudice unless other

wise stated.

Rule 41(a)(1) is the shortest and surest route to

abort a complaint when it is applicable. So long

as plaintiff has not been served with his adver

sary's answer or motion for summary judgment he

need do no more than file a notice of dismissal

with the Clerk. That document itself closes the

file. There is nothing the defendant can do to

fan the ashes of that action into life and the

24

court has no role to play. This is a matter of

running to the plaintiff and may not be

extinguished or circumscribed by adversary or

court. There is not even a perfunctory order of

court closing the file. Its alpha and omega was

the doing of the plaintiff alone. He suffers no

impairment beyond his fee for filing.

American Cyanamid Co. v. McGhee, 317 F .2d 295,

297 (5th Cir. 1963).

The right of plaintiff under the rule is absolute. Although

1

there is at least one case to the contrary, it has not been

followed but rather the text of the rule is applied. Wright

& Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure: Civil §2363, p. 157;

Plains Growers, Inc, v. Ickes-Braun Glasshouses, Inc., 474

F.2d 250 (5th Cir. 1973); Nix v. Fulton Lodge No. 2, 452 F .2d

794 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, den. 406 U.S. 946 (1972); Miller v .

Reddin, 422 F.2d 1264 (9th Cir. 1970)(where trial court

announced orally how it was going to decide voluntary dis

missal still allowed).

2Rule 41(a)(1) is subject to the provisions of Rule 66,

1. Harvey Aluminum v. American Cyanamid Co., 203 F .2d

105 (2nd Cir. 1953), cert, den. 345 U.S. 964 (1953)(voluntary

dismissal denied after hearing on preliminary injunction de

nied when hearing took several days and yielded some 420 pages of record).

2. Concerning receivers and not applicable.

25

and Rule 23(e), F. R. Civ. P. This latter provides that

class actions should not be dismissed or compromised without

the approval of the court and notice to the class. Even

assuming Rule 23(e) applies to a Rule 23(b)(1) class (R2),

the suit was never certified as a class action pursuant to

1

Rule 23(c)(1) and the judgment did not describe the class.

Rule 23(c)(3). Moreover, since the notice contemplated is

to protect the class, the district could hardly have refused

dismissal without prejudice because of Rule 23(e) and then

dismissed with prejudice. The latter would have been clearly

detrimental to the class.

D. The Reasons Given By the District Court For Reinstating

Its Order on the Merits Are Legally Insufficient.

The court assigned two reasons for reinstating its

March 28, 1974, order— failure to comply with the pretrial

order and failure to prosecute (R29-30).

1. Non-Compliance With the Pretrial Order

The district did not state exactly how plaintiffs failed

to comply with the pretrial order. It stated only that the

1. Cf. Weight Watchers of Philadelphia, Inc. v. Weight

Watchers International, Inc., 455 F.2d 770, 773, n. 1 (2nd

Cir. 1972).

26

requirements "not having been complied with" and "this Court

having been afforded no reason why the plaintiffs should have

been excused from these requirements", and recited that the

plaintiffs made no contact with the Court concerning the

Pretrial Conference nor the filing of the Motion to Dismiss."

(R29)

The pretrial order directed counsel to confer and pre-

^ proposed pretrial order to be filed a week in advance

of the pretrial hearing (R24). It also directed considera

tion of settlement to avoid the "extensive labor of prepar

ing the proposed Pretrial Order. Save your time, the Court's

time, and the client's time." (R24)

Aside from the anomaly of apparently requiring plain

tiffs to prepare a pretrial order even though they were dis

missing the case, the "fault" is hardly properly ascribed to

plaintiffs alone. The time records submitted in support of

fees reveals that the only effort of defendants to confer

with plaintiffs regarding pretrial was to write a letter on

July 23, 1974, a date after the pretrial order was to be in

the court's hands. (Defendants' exhibits 1 and 3 on motion

for fees.)

27

There is no requirement in the pretrial order or law

that plaintiffs contact the court to take the action they

did, but failure to contact the court was a part of the

district court's recited reasons for its decision.

Although the pretrial order provided penalties for

both plaintiffs and defendants for "[f]ailure of strict

compliance", the court imposed the penalty only on plain

tiffs (R27) .

2. Failure to Prosecute

While declaring "want of further prosecution" as a

reason for reinstating the order on the merits, the court

ignored the fact that defendants had themselves failed

to comply with the pretrial order equally as plaintiffs.

Want of prosecution is hardly applicable when volun

tary dismissal is sought. Moreover, defendants had failed

to responsively plead to the complaint, or to plead at all.

Defendants were just as liable to have default judgment

1

entered, Rule 55, F. R. Civ. P., as were plaintiffs for

dismissal with prejudice for failure to prosecute.

1. And the pretrial order.

28

DEFENDANTS WERE NOT ENTITLED TO

AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS' FEES UNDER

APPLICABLE LAW ON THE FACTS PRESENTED

Contrary to Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.,

488 F .2d 714, 720 (5th Cir. 1974), the district court gave

no hint of what it might have considered to be the proper

authority for the award nor the considerations which led

-it to set the amount. There is no authority for such award,

statutorily or judicially created.

A. Background of Law.

Federal courts have always had the equitable discretion

to award attorneys' fees in the absence of specific statu

tory authorization, Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307

U.S. 161 (1939), but in actual practice this was a power

rarely utilized. The American as opposed to the English rule

has always been that absent statutory or other specific

authority attorneys' fees are not to be awarded even to the

prevailing party. Fees were sometimes awarded where plain

tiffs created a fund for the benefit of a class. Trustees v,

Greenough, 105 U.S. 527 (1882). r\ i. u i j i i i r - uumrm d'.VcltU“G

in early civil rights cases only where "obdurate obstinacy"

was shown. Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

345 F .2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965) (en banc).

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 provided for attorneys'

29

fees to the prevailing party in cases involving employment

1 2

discrimination and public accommodations. The Act was

applied in Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400,

402 (1968):

When a plaintiff brings an action under ... Title

[II], he cannot recover damages. If he obtains

an injunction, he does so not for himself alone

but also as a "private attorney general," vindi

cating a policy that Congress considered of the

highest priority. If successful plaintiffs were

routinely forced to bear their own attorneys' fees,

few aggrieved parties would be in a position to

advance the public interest by invoking the in

junctive powers of the federal courts. Congress

therefore enacted the provision for counsel fees—

not simply to penalize litigants who deliberately

advance arguments they know to be untenable but,

more broadly, to encourage individuals injured by

racial discrimination to seek judicial relief under

Title II.

(Footnotes omitted).

In light of Newman and Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396

U.S. 375 (1970), courts began awarding fees in cases based

on statutes which set broad national policies but did not

provide expressly for attorneys' fees. See, Long v. Georgia

Kraft Co., 455 F.2d 331, 336 (5th Cir. 1972); Lee v. Southern

1. Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e— 5 (k) .

2. Title II, 42 U.S.C. §2000a— 3 (b) .

30

Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143 (5th Cir. 1971).

The blend of "private attorney general" and "benefit

to the class concepts is certainly applicable to suits

challenging apportionment statutes as discriminatory on the

basis of race.

If/ pursuant to this action/ plaintiffs have

benefited their class and have effectuated a

strong congressional policy, they are entitled

to attorneys' fees regardless of defendants'

good or bad faith. See Mills v. Electric Auto-

Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375, 90 S.Ct. 616, 24 L.Ed.2d

593 (1970). Indeed, under such circumstances,

the award loses much of its discretionary charac

ter and becomes a part of the effective remedy

a court should fashion to encourage public-minded

suits, id., and to carry out congressional policy.

Lee v. Southern Home Sites, 444 F.2d 143 (5th Cir 1971).

The present case clearly falls among those meant

to be encouraged under the principles articulated

in Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc, and Mills, and

expanded upon in Southern Home Sites and Bradley.

The benefit accruing to plaintiffs' class from

the prosecution of this suit cannot be overempha

sized. No other right is more basic to the in

tegrity of our democratic society than is the

right plaintiffs assert here to free and equal

suffrage. In addition, congressional policy strong

ly favors the vindication of federal rights violated

under color of state law, 42 U.S.C. §1983, and,

more specifically, the protection of the right to

a nondiscriminatory franchise.

(Footnote omitted.)

Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691, 694 (M.D. Ala. 1972)

(three-judge court), aff'd, 409 U.S. 942 (1972).

31

The benefit of enforcing Congressional policy is strongly

entrenched. Hall v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1 (1973)(union member

allowed fee from union treasury for suing union to vindi

cate right of free speech within union).

There Being No Statutory Authorization For Awarding Fees

Here, Defendants Must Rely on Judicially Developed Law.

This suit was brought under 42 U.S.C. §§1971 and 1983.

Neither has a provision relating to attorneys' fees. Defen

dants citation of 42 U.S.C. §2000a— 3(b), was completely

erroneous since by its terms it applies only to the sub

chapter it is a part of, 42 U.S.C. §2000a— public accom

modations. Contrary to their citation of Yelverton v.

Driggers, 370 F. Supp. 612 (M.D. Ala. 1974) as an example

of attorneys' fees being awarded in a local apportionment

case under 42 U.S.C. §2000a— 3(b), Judge Johnson in Yelverton

cited Title II merely as an example of a civil rights statute

providing for attorneys' fees. 310 F. Supp. at 620. Even if

defendants had available a statute providing for attorneys'

fees to the "prevailing party", they have not established

that as public defendants in a civil rights action that an

award would be appropriate. Richardson v. Hotel Corporation

of America, 332 F. Supp. 519 (E.D. La. 1971), aff'd, 468 F.2d

951 (5th Cir. 1972).

- 32

AWARDING ATTORNEYS' FEES TO

DEFENDANTS HAS A DETERRENT EFFECT

IN DIRECT CONFLICT WITH PUBLIC POLICY

The converse of awarding fees to plaintiffs in civil

rights actions, î .e. , to award fees against them, has an

unarguable deterrent effect on the bringing of such suits.

This was acknowledged in Wilderness Society v. Morton,

495 F.2d 1026, 1032, n. 2 (D.C. Cir. 1974)(en banc), cert.

granted No. 73-1977, 43 U.S.L.W. 3208:

Had appellees been the prevailing parties and

sought attorneys' fees from appellants, the pos

sibility of deterrence would be significant and

the rationale of the American rule would therefore

bar recovery of fees. In this sense there is an

admitted lack of reciprocity in granting attorneys'

fees under a private attorney general theory.

The same lack of reciprocity, however, appears

to be present in so-called "common benefit" cases.

In Hall v. Cole, 412 U.S. 1, 93 S.Ct. 1943, 36

L.Ed.2d 702 (1973), for example, the successful

plaintiff in a suit brought under §102 of the

Labor-Management Reporting & Disclosure Act of

1959 was awarded fees from the defendant union on

the ground the suit benefitted all union members

and reimbursement of attorneys' fees out of the

union treasury would shift the costs of litigation

to these beneficiaries. 412 U.S. at 7-8, 93 S.Ct.

1943. Had the defendant union prevailed on the

merits, however, it is doubtful that the same theory

would have required awarding fees to defendant

because of the risk of deterring plaintiffs from

bringing suit.

And see, Byram Concretanks, Inc, v. Warren Concrete Products

33

Co^, 374 F.2d 649, 651 (3rd Cir. 1967), reversing an award of

attorneys' fees to the defendant in a private anti-trust action

because "[t]he incentive which the prospect of treble damages

provides for instituting private anti-trust actions would

be dampened by the threat of assessment of defendant's

attorneys' fees and other costs as a penalty for failure."

in their pleadings admit that they seek to

deter civil rights actions by the quotation from the NAACP

attorney (R37). And they left no doubt by taking out a

garnishment against one of the plaintiffs employed

1

by the American Friends Service Committee while this matter

is on appeal (R50-57, 59-60).

““ ' -- —3 ~~(Quakers) often in

bama. E.cj_., Davis

1970) .

r\ i- t- n /-< ij I i i n _ _ ■ _ i _ r « • ■»— j.wUo ouCie of r riends

conflict with the school systems of Ala-

v. United States, 422 F.2d 1139 (5th Cir.

34

CONCLUSION

The two lawyers who submitted fees represented jointly

the school board and the party chairman. They did not

represent all defendants (R80). They sought and seek $2,500

for litigating a case in which the first pleading they filed

wae a biLl of costs. They argue that the fee is justified

to deter such litigation and further that the court should

award a fee at an hourly rate higher than they billed be

cause plaintiffs did not acquiesce and pay their fee (R103-

04) .

They filed no pleadings, answered no discovery, put on

no witnesses on the merits, only as to fees. They suffered

no ostracism for handling an undesirable case. Sanders v.

Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968); NAACP v. Allen, 340

F. Supp. 703, 710 (M.D. Ala. 1972). The award is hardly

justified as supporting any public policy necessary to be

certain that school boards are represented by counsel in

civil rights actions. To the contrary, the action of the

<̂ str-̂ct court goes beyond the concern expressed in Cole v.

hail, 402 F.2d 777, 779-80 (2nd Cir. 1972), aff'd 412 U.S.

1 (1973), where the lone union member prevailed against his

union:

Not to award counsel fees in cases such as this

would be tantamount to repealing the Act itself

by frustrating its basic purpose ... Counsel

fees in cases of this kind are not only appro

priate, they are imperative to preserve the

Congressional purpose ... Without counsel fees

the grant of federal jurisdiction is but a

gesture...

In comparison, the deterrent effect of awarding attorneys

fees against plaintiffs in a civil rights action, without

statutory authority, is clearly against the thrust of

public policy. The grant of federal jurisdiction would

indeed be a hollow promise if this is permitted.

For the foregoing reasons the orders of the district

court of October 1 and October 9, 1974, should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Of Counsel:

Melvin L. Wulf

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York 10016

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

Neil Bradley

Laughlin McDonald

52 Fairlie Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

36

Act 454, 1951 Acts of Alabama:

AN ACT

<or the 0,'"i0n lhe mem-

Be It Enacted by the Legislature of Alabama:

taw f w S } ' u S ?? me1mbei: of the Board of Education of Choc-

districts Ĵected for each of the f ° ur commissioner’s

member of t h T h ? J hl T ? ty J8 -divided, and the fifth

°S the board shal1 be elected for the county at large

t K e d S Sector of, and reside in

he bnmlnof ? j hl,ch h° , ls elected, but all the-members shall

fifK tCdiand ! Ie,cted by the elcctors of the county at large-

JesideinT h^rtT “ r " 6 boardm ust be a clualificd elector of, and

m e and h l = ta^ County Members of the board for districts

one and two shall be elected at the general election in 1952

and every a « years thereafter. Members of the boaM from dS

loafi thj and tour shal1 be eIeated at the general election in

boardashaflVbeye r X, T ? T h e fifth member of the Doard shall be elected at the general election in 1954 and everv

hnl/th™ tb®,r.eafter- The incumbent members of the ’board shall

C6S Until th6ir SUCCessors are elected as Provided in

Acfare^pealed!1 ^ °F ^ ° f laWS which c0nflict with this

a , Thc, Provisi?ns ° f this Act are severable. If any

ratin -^-ot1S declared invalid or unconstitutional, such decla

ration shall not effect the part which remains.

Section 4. This Act shall become effective immediatelv nnnn

f c S I a W . aPPr° Val ^ " ’ e GOVCm0r- “

Approved August 17, 1951.

Time: 8:11A .M .

42 U.S.C. §1971:

SUBCHAPTER I.—GENERALLY

Voting rights— Race, color, or previous condition

not to affect right to vote; uniform standards for

voting qualification; errors or omissions from

papers; literacy tests; agreements between A t

torney General and State or local authorities;

definitions

(a )(1 ) All citizens of the United States who are otherwise quali

fied by law to vote at any election by the people in any State, Terri

tory, district, county, city, parish, township, school district, munici

pality, or other territorial subdivision, shall be entitled and al

lowed to vote at all such elections, without distinction of race, color,

or previous condition of servitude; any constitution, law, custom,

usage, or regulation of any State or Territory, or by or under its au

thority, to the contrary notwithstanding.

(2) No person acting under color of law shall—

(A) in determining whether any individual is qualified under

State law or laws to vote in any election, apply any standard,

practice, or procedure different from the standards, practices, or

procedures applied under such law or laws to ocher individuals

within the same county, parish, or similar political subdivision

who have been found by State officials to be qualified to vote;

(B) deny the right of any individual to vote in any election be

cause of an error or omission on any record or paper relating to

any application, registration, or other act requisite to voting, if

such error or omission is not material in determining whether

such individual is qualified under State law to vote in such

election; or

(C) employ any literacy test as a qualification for voting in

any election unless (i) such test is administered to each indi

vidual and is conducted wholly in writing, and (ii) a certified

copy of the test and of the answers given by the individual is

furnished to him within twenty-five days of the submission of

his request made within the period of time during which records

and papers are required to be retained and preserved pursuant

to sections 1974 to 1974e of this title: Provided, however, That

the Attorney General may enter into agreements with appro

priate State or local authorities that preparation, conduct, and

maintenance of such tests in accordance with the provisions of

applicable State or local law, including such special provisions

as are necessary in the preparation, conduct, and maintenance of

such tests for persons who are blind or otherwise physically

§ 1971.

Add. 2

handicapped, meet the purposes of this subparagraph and con

stitute compliance therewith.

(3) For purposes of this subsection—

(A) the term “vote” shall have the same meaning as in

subsection (e) of this section;

(B) the phrase “ literacy test” includes any test of the ability

to read, write, understand, or interpret any matter.

latlm ldation , threat*, o r coercion

(b) No person, whether acting under color of law or otherwise,

shall intimidate, threaten, coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten,

or coerce any other person for the purpose of interfering with the

right of such other person to vote or to vote as he may choose, or of

causing such other person to vote for, or not to vote for, any candi

date for the office of President, Vice President, presidential elector,

Member of the Senate, or Member of the House of Representatives,

Delegates or Commissioners from the Territories or possessions, at

any general, special, or primary election held solely or in part for

the purpose of selecting or electing any such candidate.

Preventive re lie f) in junction ; rebuttable literacy presum ption;

liab ility o f United States fo r costs ; State as party defendant

(c) Whenever any person has engaged or there are reasonable

grounds to believe that any person is about to engage in any act or

practice which would deprive any other person of any right or privi

lege secured by subsection (a) or (b) of this section, the Attorney

General may institute for the United States, or in the name of the

United States, a civil action or other proper proceeding for preven

tive relief, including an application for a permanent or temporary

injunction, restraining order, or other order. If in any such nro-

ceeding literacy is a relevant fact there shall be a rebuttable pre

sumption that any person who has not been adjudged an incompe

tent and who has completed the sixth grade in a public school in, or

a private school accredited by, any State or territory, the District of

Columbia, or the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico where instruction is

carried on predominantly in the English language, possesses suffi

cient literacy, comprehension, and intelligence to vote in any elec

tion. In any proceeding hereunder the United States shall be liable

for costs the same as a private person. Whenever, in a proceeding

instituted under this subsection any official of a State or subdivi

sion thereof is alleged to have committed any act or practice consti

tuting a deprivation of any right or privilege secured by subsection

(a) of this section, the act or practice shall also be deemed that of

the State and the State may he ininpd as a party defendant and, if,

prior to the institution of such proceeding, such official has re

signed or has been relieved of his office and no successor has as

sumed such office, the proceeding may be instituted against the

State.

Add. 3

Jurisd iction ; exhaustion o l other rem edies

(d) The district courts of the United States shall have jurisdic

tion of proceedings instituted pursuant to this section and shall ex

ercise the same without regard to whether the party aggrieved shall

have exhausted any administrative or other remedies that may be

provided by law.

Order qu a lify in g ptraon to v ote ; applications hearings voting

referee*; transm ittal o f report and orders certifica te

o f qualifications defin itions

(e) In any proceeding instituted pursuant to subsection (c) of

this section in the event the court finds that any person has been

deprived on account of race or color of any right or privilege se

cured by subsection (a) of this section, the court shall upon request

of the Attorney General and after each party has been given notice

and the opportunity to be heard make a finding whether such depri

vation was or is pursuant to a pattern or practice. If the court

finds such pattern or practice, any person of such race or color resi

dent within the affected area shall, for one year and thereafter un

til the court subsequently finds that such pattern or practice has

ceased, be entitled, upon his application therefor, to an order declar

ing him qualified to vote, upon proof that at any election or elec

tions (1) he is qualified under State law to vote, and (2) he has

since such finding by the court been (a) deprived of or denied un

der color of law the opportunity to register to vote or otherwise to

qualify to vote, or (b) found not qualified to vote by any person act

ing under cnor of law. Such order shall be effective as to any

election held within the longest period for which such applicant

could have been registered or otherwise qualified under State law

at which the applicant’s qualifications would under State law enti

tle him to vote.

Notwithstanding any inconsistent provision of State law or the

action of any State officer or court, an applicant so declared quali

fied to vote shall be permitted to vote in any such election. The At

torney General shall cause to be transmitted certified copies of such

order to the appropriate election officers. The refusal by any such

officer with notice of such order to permit any person so declared

qualified to vote to vote at an appropriate election shall constitute

contempt of court.

An application for an order pursuant to this subsection shall be

heard within ten days, and the execution of any order disposing of

such application shall not be stayed if the effect of such stay would

be to delay the effectiveness of the order beyond the date of any

election at which the applicant would otherwise be enabled tn vntp

The court may appoint one or more persons who are qualified vot

ers in the judicial district, to be known as voting referees, who shall

subscribe to the oath of office required by Revised Statutes, section

Add. 4

1757; to serve for such period as the court shall determine, to re

ceive such applications and to take evidence and report to the court

findings as to whether or not at any election or elections (1) any

such applicant is qualified under State law to vote, and (2) he has

since the finding by the court heretofore specified been (a) de

prived of or denied under color of law the opportunity to register to

vote or otherwise to qualify to vote, or (b) found not qualified to

vote by any person acting under color of law. In a proceeding be

fore a voting referee, the applicant shall be heard ex parte at such

tunes and places as the court shall direct. His statement under oath

shall be prima facie evidence as to his age, residence, and his prior

efforts to register or otherwise qualify to vote. Where proof of lit

eracy or an understanding of other subjects is required by valid

provisions of State law, the answer of the applicant, if written,

shall be included in such report to the court; if oral, it shall be tak

en down stenographically and a transcription included in such re

port to the court.

Upon receipt of such report, the court shall cause the Attorney

General to transmit a copy thereof to the State attorney general and

to each party to such proceeding together with an order to show

cause within ten days, or such shorter time as the court may fix,

why an order of the court should not be entered in accordance with

such report. Upon the expiration of such period, such order shall

be entered unless prior to that time there has been filed with the

court and served upon all parties a statement of exceptions to such

/eport. Exceptions as to matters of fact shall be considered only if

supported by a duly verified copy of a public record or bv affidavit

of persons having personal knowledge of such facts or by state

ments or matters contained in such report; those relating to mat-

i ° L lawr Shal* be suPP°rted by an appropriate memorandum of

law. The issues of fact and law raised by such exceptions shall be

determined by the court or, if the due and speedy administration of

justice requires, they may be referred to the voting referee to deter

mine m accordance with procedures prescribed by the court. A

earing as to an issue of fact shall be held only in the event that

the proof in support of the exception disclose the existence of a

genuine issue of material fact. The applicant’s literacy and under

standing of other subjects shall be determined solely on the basis of

answers included in the report of the voting referee.

The court, or at its direction the voting referee, shall issue to

each applicant so declared qualified a certificate identifying the

holder thereof as a person so qualified.

Any voting referee appointed by the court pursuant to this

subsection snan to the extent not inconsistent herewith have all the

powers conferred upon a master by rule 53(c) of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure. The compensation to be allowed to any persons

Add. 5

appointed by the court pursuant to this subsection shall be fixed by

the court and shall be payable by the United States.

Applications pursuant to this subsection shall be determined expe

ditiously. In the case of any application filed twenty or more days

prior to an election which is undetermined by the time of such elec

tion, the court shall issue an order authorizing the applicant to vote

provisionally: Provided, however, That such applicant shall be qual

ified to vote under State law. In the case of an application filed

within twenty days prior to an election, the court, in its discretion,

may make such an order. In either case the order shall make appro

priate provision for the impounding of the applicant’s ballot pend

ing determination of the application. The court may take any other

action, and may authorize such referee or such other person as it

may designate to take any other action, appropriate or necessary to

carry out the provisions of this subsection and to enforce its de

crees. This subsection shall in no way be construed as a limitation

upon the existing powers of the court.

When used in the subsection, the word “ vote” includes all action

necessary to make a vote effective including, but not limited to, reg

istration or other action required by State law prerequisite to vot

ing, casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted and included in

the appropriate totals of votes cast with respect to candidates for

public office and propositions for which votes are received in an

election; the words “ affected area” shall mean any subdivision of

the State in which the laws of the State relating to voting are or

have been to any extent administered by a person found in the pro

ceeding to have violated subsection (a) of this section; and the

words “ qualified under State law” shall mean qualified according to

the laws, customs, or usages of the State, and shall not, in any

event, imply qualifications more stringent than those used by the

persons found in the proceeding to have violated subsection (a) of

this section in qualifying persons other than those of the race or

color against which the pattern or practice of discrimination was

found to exist.

Contem pt) assignm ent o f counsel; w itnesses

(f) Any person cited for an alleged contempt under this Act shall

be allowed to make his full defense by counsel learned in the law;

and the court before which he is cited or tried, or some judge there

of, shall immediately, upon his request, assign to him such counsel,

not exceeding two, as he may desire, who shall have free access to

him at all reasonable hours. He shall be allowed, in his defense to

make any proof that he can produce by lawful witnesses, and shall

have the like process of the court to compel his witnesses to appear

at. >ii<a trial nr hoaring an i<5 usually granted to Compel witnesses to

appear on behalf of the prosecution. If such person shall be found

by the court to be financially unable to provide for such counsel, it

shall be the duty of the court to provide such counsel.

Add. 6

Three-judge district cou rt: hearing, determ ination, expedition o f action,

eeriest by Supreme C ourt: s in g le -ju d ge d istrict cou rt: hearing,