Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts Brief on the Merits for Petitioner, Firefighters Local Union No. 1784

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts Brief on the Merits for Petitioner, Firefighters Local Union No. 1784, 1983. eed141ba-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db5659c3-6108-4e40-89e0-6541ae38003e/firefighters-local-union-no-1784-v-stotts-brief-on-the-merits-for-petitioner-firefighters-local-union-no-1784. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

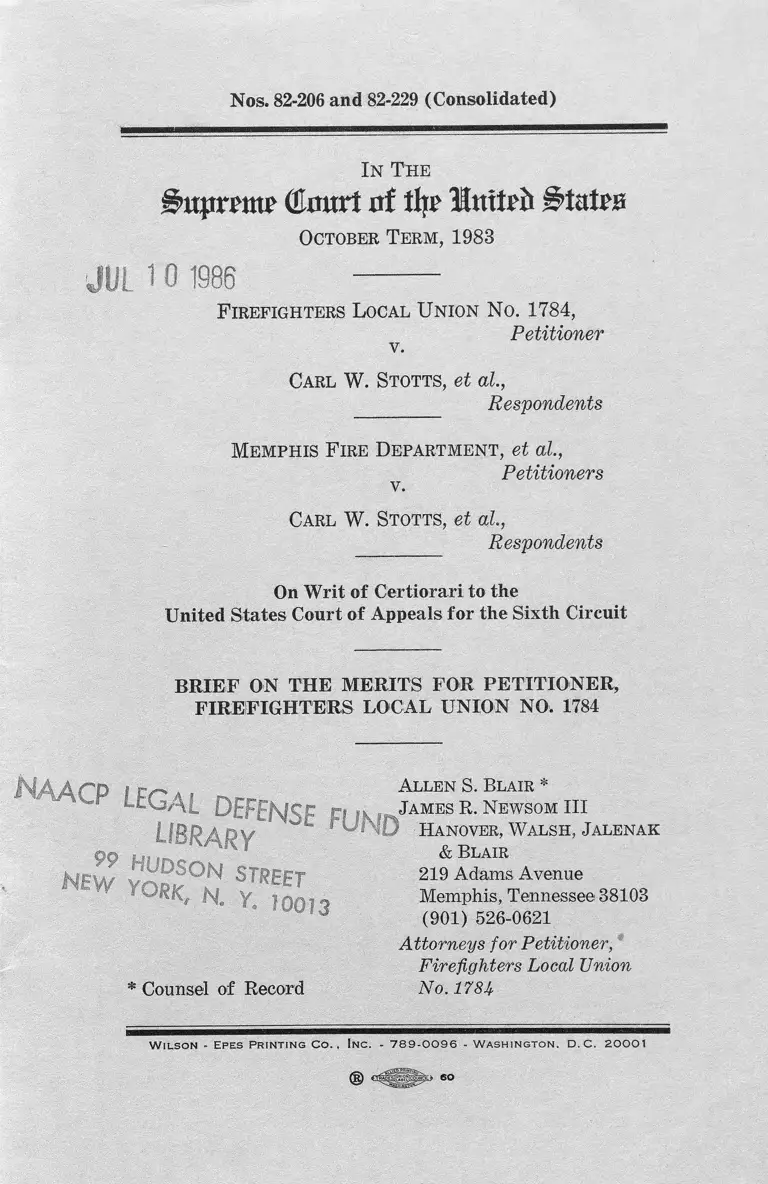

Nos. 82-206 and 82-229 (Consolidated)

In T he

i ’ujmw (Uiwrt nf % Inttefr Btatm

October T erm , 1983

JUL 1 0 1986 -------

F irefighters Local U nion N o. 1784,

Petitionerv.

Carl W. Stotts, et al,

Respondents

Mem phis F ire Departm ent , et al,

Petitionersv.

Carl W. Stotts, et al,

Respondents

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF ON THE MERITS FOR PETITIONER,

FIREFIGHTERS LOCAL UNION NO. 1784

LE upi; PFENs

99 Hi

n e w 3AK, ;N.

y

° N STREET

10013

* Counsel of Record

A llen S. Blair *

James R. Newsom III

Hanover, W alsh , Jalenak

& Blair

219 Adams Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

(901) 526-0621

Attorneys for Petitioner,

Firefighters Local Union

No. 1784.

W i l s o n - Ep e s Pr i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n . D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

L> 60

QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether a district court has the authority to modify a

consent decree, silent in regard to layoffs, in such a man

ner that a bona fide seniority system calling for layoff by

seniority is abrogated to the detriment of innocent in

cumbent employees, in an action where there has been no

adjudication of discrimination by the employer or the

union.*

* Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 has no parent, subsidiary or

affiliate required to be reported under S.Ct.R. 28.1. The local union

is itself an affiliate of the International Association of Firefighters,

AFL-CIO, CLC.

(i)

11

Petitioner Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 inter

vened in the District Court and appeared as an appellant

in Court of Appeals Nos. 81-5348 and 81-5349. Memphis

Fire Department, Robert W. Walker, City of Memphis

and Joseph Sabatini were also appellants below and are

petitioners in No. 82-229. Carl W. Stotts, individually

and as a class representative on behalf of all others sim

ilarly situated, and Fred L. Jones appeared as appellees in

Court of Appeals Nos. 81-5348 and 81-5349, respectively,

and are respondents in Nos. 82-206 and 82-229.

LIST OF PARTIES

Page

QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW .................. i

LIST OF PARTIES ____________________ _____ ______ ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS________ ___ _______-................ iii

TABLE OF AUTH ORITIES....... ...................... ......... ..... iv

OPINIONS AND JUDGMENTS BELOW ________ 1

JURISDICTION___ ________ ________________________ 2

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED ______ 2

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ..... .................... ............ . 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUM ENT_______________________ 10

ARGUM ENT................. 12

CONCLUSION .......... ........ .................... ......................... ...... 48

STATUTORY APPENDIX .............. .............. .................. la

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(iii)

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ........ ...................... ........................................... 39

American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63

(1982) ___ 41

Brown v. Neeb, 644 F.2d 551 (6th Cir. 1981) .......... 20, 24

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 534 F.2d 993 (2d

Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 431 U.S. 965 (1977)...... 46

Connecticut v. Teal, 102 S.Ct. 2525 (1982 )_______ 29

EEOC v. Ford Motor Co., 102 S.Ct. 3057 (1982).... 39, 44

Ford Motor Co. v. United States, 335 U.S. 303

(1948) _____ 17,28

Fox v. United States Department of Housing and

Urban Development, 680 F.2d 315 (3d Cir.

1982) ___ passim

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) _______ passim

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980) .......... 47

General Bldg. Contractors Ass’n, Inc. v. Pennsyl

vania, 102 S.Ct. 3141 (1982)___ ________ ___ _ 22

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)___ 45

Holmberg v. Armbrecht, 327 U.S. 392 (1946)..... . 28

Hughes v. United States, 342 U.S. 353 (1952)____ 13, 23

Jersey Central Power & Light Co. v. Local Union

327, IBEW, 508 F.2d 687 (3d Cir. 1975), cert.

denied, 425 U.S. 998 (1976)..... ............ ................ 46

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976) _____________ _____ ______ 45

Memphis Fire Dept. v. Stotts, 679 F.2d 541 (6th

Cir. 1982), cert, granted, 103 S.Ct. 2451 (1983).. 9

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)...... .......... 11, 29

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977)......... ....... 29

Northwest Airlines, Inc. v. Transport Workers, 451

U.S. 77 (1981)................... ................ ................ ...... 28,48

Orders v. Stotts, 679 F.2d 579 (6th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 103 S.Ct. 297 (1982) _________ __________ 6

Paperworkers Local 189 v. United States, 416 F 2d

980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919

(1970) _______ __ ____ __ _________ _____ .......37,38,43

V

Page

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257

(4th Cir. 1976)_________ ___ ___ ______________ _ 43

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ...... ............. 29

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229

(1969) ...... -............... ......... ....................... ................ 30

System Federation No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642

(1961) ......................... 20,28

Teamsters v. United States, 431 IJ.S, 324 (1977)....passim

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison, 432 U.S.

63 (1977)_________ 4i

TV A v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (1978) ............................ 28

United States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673

(1971) .............................. .................................... . io, 12

United States v. Atlantic Mutual Ins. Co., 343 U.S.

236 (1952) ................................................................. 28

United States v. Atlantic Refining Co., 360 U.S. 19

(1959)..... ............ ........................ ....... ....................... 13, 23

United States v. ITT Continental Baking Co., 420

U.S. 223 (1975)......... .................. ........... .......... 17

United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (1932).. 10,18,

23

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Co., 391

U.S. 244 (1968)_____ _______ ______________ ____ 17

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193 (1979), reh’g denied, 444 U.S. 889 (1980).... 22, 34

University of California Regents v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265 (1978)._____ _____ ____________ _____ _ 46,47

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976)________ 22

Watkins v. Steelworkers Local No. 2369, 516 F.2d

41 (5th Cir. 1975)................................................... 46

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., 502 F.2d 1309 (7th Cir. 1974),

cert, denied, 425 U.S. 997 (1976)_______ ____ _ 46

Youngblood v. Dalzell, 568 F.2d 506 (6th Cir.

1978)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

20

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

STATUTES

United States Constitution

Fourteenth Amendment.......................................... 21

United States Code

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) .............................................. 2

42 U.S.C.

§ 1981.............................................. passim,

§ 1983 .............................................................. passim

§ 1988 .......................... ............................................ 29, 30

§ 2000e, et seq. (Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act) ..................................................... passim

§ 2000e-2 (a) (Civil Rights Act § 703 ( a ) ) ____ 2, 10,

34, 35

§ 2000e-2 (h) (Civil Rights Act § 703 ( h ) ) ........passim

§ 2000e-2(j) (Civil Rights Act § 703( j ) ) . .......passim

§ 2000e-5 (g) (Civil Rights Act § 706 ( g ) ) ........passim

MISCELLANEOUS

110 Cong. Rec________________ __ _______31, 32, 33, 34, 42

118 Cong. R ec...... ................... .......... .......................... 36

D. Dobbs, Handbook on the Law of Remedies

(1973 )....... 26

Bureau of National Affairs, Layoffs, RIFs and EEO

in the Public Sector, Fair Employment Practices

Supplement 439, February 13, 1982 .................... 19

In T he

B n p n m t (tart a t % M nlU h B u tm

October T erm , 1983

No. 82-206

F irefighters Local U nion N o. 1784,

Petitionerv.

Carl W. Stotts, et al.,

Respondents

No. 82-229

Mem phis F ire Departm ent, et al,

Petitionersv.

Carl W. Stotts, et al.,

Respondents

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF ON THE MERITS FOR PETITIONER,

FIREFIGHTERS LOCAL UNION NO. 1784

OPINIONS AND JUDGMENTS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Cir

cuit of which review is sought is reported officially at 679

F.2d 541. The judgment of the Court of Appeals is set

forth in the Joint Appendix at J.A. 141. The opinion is set

forth in the appendix to the petition of Firefighters Local

Union No. 1784 at App. 1. The oral ruling of the District

Court, not reported, is reproduced in the appendix to the

Union’s petition at App. 77.

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of the Court rests on 28 U.S.C. § 1254

(1). The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered

on May 7, 1982. The petition for a writ of certiorari was

timely filed on August 4, 1982 and was granted on June

6, 1983.

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The statutory provisions involved are as follows: 42

TLS.C. §§ 1981, 1983 and 1988 and §§ 703(a), 703(h),

703(j) and 706(g) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a), 2000e-2(h), 20Q0e-2(j)

and 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g).

The text of the statutes is set forth in the appendix

thereto at la.

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The cases presented for review arise from class actions

filed by respondents, black male employees of the Mem

phis Fire Department (hereinafter “ respondents” ), in

the United States District Court for the Western District

of Tennessee.1 Respondents asserted claims of violations

of rights secured by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. §■§ 2000e, et seq., as amended by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (Pub.L.

92-261, March 24, 1972) and by 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and

1983 (Pet. A. 59). Particularly, the respondents alleged

that certain promotional policies and practices on the part

of the original defendants (hereinafter collectively the

“ City” ) were unlawful and favored white employees over

their minority counterparts in promotional decisions

(J.A. 10, 16). The respondents did not attack the layoff

or seniority policies of the City. The relief prayed for the

1 Stotts v. Memphis Fire Dep’t, No. 77-2104 (W.D. Term, filed

Feb. 11, 1977) (J.A. 8) ; Jones v. Memphis Fire Dep’t, No. 79-2441

(W.D. Term, filed June 19, 1979) (J.A. 15). The two actions were

consolidated in September, 1979 (Union Petition [hereinafter re

ferred to as “Pet.” ] A. 5).

3

respondents included an award of back pay, reimburse

ment of lost pensions, Social Security, experience, train

ing opportunities and promotions (J.A. 11, If 4; 17,

114). Petitioner Firefighters Local Union No. 1784

(hereinafter “ Union” ) was not named as a defendant in

either complaint. Respondents did not pray for an award

of constructive competitive seniority. As a result, the

Union did not intervene as the City of Memphis Fire

Services Division seniority system was not directly

implicated by these actions.

When these actions were filed there was in effect a city

wide seniority system that had been adopted by the City

of Memphis as an employment practice in 1973 (J.A. 49).

Under the city-wide seniority system, an employee’s

seniority is calculated on the basis of length of service in

permanent employment with the City (J.A. 67, 85).

Seniority status is freely transferable from one city divi

sion to another (i.e., from sanitation to fire) (J.A. 70-71,

103) and from one job classification to another (i.e., from

private to lieutenant) (J.A. 67, 103). The city-wide

seniority system was negotiated into the City’s Memoran

dum of Understanding with the Union in 1975 (Pet. A.

80-81; J.A. 49, 115). The city-wide seniority system con

ferred competitive seniority status to individual em

ployees in the Fire Services Division for priority in job

decisions regarding transfers (J.A. 42, 103) and layoffs

(Pet. A. 80-81; J.A. 49, 115, 119).

The instant actions were also filed against the back

ground of a prior consent decree entered into by the City

of Memphis and the United States Department of Justice

in 1974 (hereinafter the “ 1974 Decree” ) (J.A. 98-115).

The 1974 Decree arose from United States v. City of

Memphis, No. 74-286 (W.D.Tenn.). This action alleged

that the City had engaged in a pattern or practice of dis

crimination based on race and sex in hiring and promo

tion within its divisions (J.A. 98). The 1974 Decree

resolved all issues raised by the complaint in regard to

several city divisions, including the Fire Division (J.A.

4

98). The 1974 Decree explicitly states that the entry of

the decree “ shall not constitute an adjudication or admis

sion by the City of any violation of law or findings on

the merits of the case” (J.A. 99).

In the 1974 Decree the City agreed to undertake the

long-term goal of “achieving throughout the work force

proportions of black and female employees in each job

classification approximating their respective proportions

in the civilian work force” by means of hiring qualified

black applicants to fill vacancies in the force (J.A. 101).

The City also agreed to attempt to meet an interim per

centage hiring goal (J.A. 105).

The 1974 Decree contains no admission by the City that

particular individuals were entitled to “victim” status,

nor does the 1974 Decree award constructive competitive

seniority. The 1974 Decree did not dilute the city-wide

seniority system. To the contrary, it endorses the use of

the system in regard to the City’s employment decisions

in these terms:

The City shall, for all purposes of promotion, trans

fer and assignment, compute the seniority of a per

son in the affected class as defined in paragraph 5

[incumbent female and minority employees of the

City], as the total seniority of that person with the

City.

(J.A. 103)2 Neither does the 1974 Decree commit the

City to a specified timetable for achieving its long-term

goals. Rather, it is noted that the goals are “ subject to

the anticipated budgeted vacancies in the City” (J.A.

105). The 1974 Decree utilizes hiring as the exclusive

means of achieving its long-term goals in the Fire Divi

sion. No provision of the 1974 Decree has an adverse

impact on the job security or seniority rights of incum

bent fire employees.

s As indicated above, the seniority system only applied to trans

fers and layoffs in the Fire Services Division (Pet. A. 80-81).

5

Against this background, the instant actions were

settled by the entry of a consent decree in the District

Court on April 25, 1980 (hereinafter the “ 1980 Decree” )

(Pet. A, 59-69). As with the 1974 Decree, by agreeing to

the entry of the 1980 Decree, the City did not “admit any

violations of law, rule, or regulation with respect to the

allegations made by plaintiffs [respondents herein] in

their complaints” (Pet. A. 60).8

The 1980 Decree adopts the same long-term goal and

hiring relief as that contained in the 1974 Decree (Pet. A.

64). The 1980 Decree also adopts the approach of the

1974 Decree in establishing an interim hiring goal for

the City to fill “on an annual basis at least 50% of all

vacancies with qualified black applicants” (Pet. A. 64;

J.A. 101). Neither decree requires the City to hire any

particular number of employees (J.A. 101-02). The 1980

Decree contains an additional goal “ of promoting blacks

in the proportion of at least 20% for each civil service

classification or uniformed rank as measured on an an

nual basis” (Pet. A. 65). As was true with the 1974 De

cree, the 1980 Decree contains no admission by the City

that particular individuals were entitled to “victim”

status, nor does the Decree award constructive competi

tive seniority. Likewise, the 1980 Decree did not dilute

the city-wide seniority system. The 1980 Decree contains

an explicit waiver by plaintiffs of “a hearing and findings

of fact and conclusions of law on all issues raised by the

complaints” (Pet. A. 60). No class member raised objec

tions to the 1980 Decree prior to or after its entry (Pet.

A. 7). The respondents also waived any entitlement to

further relief:

Both plaintiffs [respondents] and the class they rep

resent shall seek no further relief for the acts, prac

tices or omissions alleged in the complaints save to 3

3 The 1980 Decree: states the intention of the parties to parallel

and supplement therein the relief provided in the 1980 Decree,

thereby disclaiming an intention to conflict with the 1974 Decree

(Pet. A. 60).

6

enforce the provisions of this decree, thereby waiv

ing the right to seek further relief.

(Pet. A. 61) (emphasis added). While the 1980 Decree

does contain boilerplate language to the effect that: “ [t]he

court retains jurisdiction of this action for such further

orders as may be necessary or appropriate to effectuate

the purposes of this decree” (Pet. A. 69), this “ retain[ed]

jurisdiction” is limited by the terms of respondents’ waiv

ers. As the 1980 Decree left intact the operation of the

city-wide seniority system and did not otherwise adversely

affect the rights of its members the Union did not voice

objections to the entry of the decree.4

The record reflects that the total number of blacks

hired in the Fire Department between the entry of the

1974 Decree and May, 1981 (including rehires) reached

the level of fifty-six percent, thus exceeding the City’s in

terim goals (J.A. 48). While the Justice Department had

retained the option of establishing specific numerical

ratios for the employment of black firefighters had the

City failed in its good-faith attempts to meet the interim

goals established by the 1974 Decree (J.A. 105-06), this

option was not exercised due to the City’s success in this

regard. In May, 1981, following that history of compli

ance with the terms of the 1974 and 1980 Decrees, the

city administration announced that layoffs of municipal

employees would be necessitated due to an anticipated

budget deficit in the upcoming fiscal year. The respond

ents stipulated at the hearing on respondents’ motion for

injunctive relief, discussed i?ifra, to the City’s financial

4 The factual exposition, in the opinion of the Court of Appeals

includes a discussion of certain objections raised to the entry of

the 1980 Decree by a group of 11 nonminority firefighters, (Pet.

A. 6-8). This group’s attempted intervention is treated more fully

in Orders v. Stotts, 679 F.2d 579 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 103 S.Ct.

297 (1982). The Union did not participate in this intervention at

tempt. The discussion by the Court of Appeals of the Orders inter

veners’ objections to the 1980 Decree (Pet. A. 26-30) is not perti

nent to the instant controversy.

7

need to implement layoffs (J.A. 75). In anticipation of

the layoffs, the City promulgated a formal layoff policy

which addressed all aspects o f the anticipated layoffs

(J.A. 82-96). The layoff policy reaffirmed the City’s

obligation to lay off Fire Department personnel, if neces

sary, in conformance with the city-wide seniority system.

Neither by its promulgation of the layoff policy nor in

any other way did the City announce its intention to re

nounce or repudiate its commitment to the eventual

achievement of the long-term goals agreed to in the 1974

and 1980 Decrees.

On May 4, 1981, the respondents applied for and ob

tained a temporary restraining order enjoining the City

from laying off or reducing in rank any black fire employ

ees (J.A. 20-23). Respondents contended that the routine

application of the city-wide seniority system would “effec

tively destroy the affirmative relief” granted by the 1980

Decree (J.A. 21). The United States Department of Jus

tice neither joined respondents’ petition nor sought simi

lar relief in its parallel action.

On May 5, 1981, the District Court permitted the

Union to intervene (J.A. 24). The Union intervened in

order to assert the rights and interests of its members in

the impending layoffs and reductions in rank (J.A. 24).

The order allowing the Union’s intervention was entered

with the consent of all parties. This intervention marked

the first occasion that the Union had sought to assert an

interest in these actions.

On May 8, 1981, the District Court held an evidentiary

hearing on the respondents’ request for a preliminary in

junction (Pet. A. 72-76; J.A. 29-119). Following the

hearing, the District Court found that the 1980 Decree

did not address layoffs or the method to be used in the

event that layoffs or reductions in rank became necessary

8

(Pet, A. 73, 77-78).5 Further, the Court found that the

City’s layoff policy was not adopted with the purpose or

intent to discriminate on the basis of race,8 but concluded

that the application of the city-wide seniority policy would

have a discriminatory effect.6 7 The District Court found

the city-wide seniority system to be non-bona fide due to

this discriminatory effect.8

The District Court held that it possessed the authority

to modify the 1980 Decree. It did so by enjoining the

City from implementing the city-wide seniority system

insofar as it would decrease the percentage of minority

6 The District Court found that the 1980 Decree did not contem

plate the circumstances that layoffs might be occasioned by fiscal

difficulties, as layoffs, were unprecedented in the City’s recent his

tory (Pet. A. 73). While the Court of Appeals characterizes the

District Court’s finding to be that there existed “changed” circum

stances (Pet. A. 8, passim), the District Court did not go so far in

its findings. Indeed, the appearance of the clause in the Union’s

Memorandum of Understanding providing for seniority-based lay

offs as early as 1975 (Pet. A. 81) makes it clear that the City’s

layoff decision was not a “changed circumstance” and could have

been anticipated when the 1980 Decree was entered in April of 1980.

8 This finding supports the legal conclusion that the city-wide

seniority system was bona fide in nature as routinely applied in the

layoff situation. Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 356

(1977). This finding, as noted by the Court of Appeals, has not

been, challenged on. appeal (Pet. A. 11 n.6).

7 The statistics relied upon by the District; Court (Pet. A. 9, 70-

71) are; not indicative of post-Act (post March 24, 1972) discrimi

nation or of violations by the City of the terms of the 1974 and

1980 Decrees. As promotional goals, were not adopted in the Fire

Division via the 1974 Decree (J.A. 107, ([ 15), the table of promo

tional statistics, contained in the Court of Appeals opinion (Pet.

A. 9 n.5) is not indicative of a violation of either the 1974 or 1980

Decrees. In fact, the District Court concluded that the City had

not been defiant, or contemptuous (Pet. A. 75).

8 The legal conclusion of the District Court that the city-wide

seniority system was non-bona fide was set aside properly as error

by the Court of Appeals (Pet. A. 11 n.6).

9

employees within four classifications in the Fire Depart

ment (Pet. A. 77-79).9 The District Court ordered the

City to propose a layoff method consistent with its in

junction (Pet. A. 79).

Judgment on the District Court’s ruling was entered

on May 18, 1981 (Pet. A. 77). Petitioners noticed their

appeals (J.A. 5) and moved to stay the District Court’s

injunction pending appeal (J.A. 120-22). The motion

was denied by the District Court (J.A. 122-23), as were

similar motions made to the Court of Appeals by petition

ers (Pet. A. 12). The appeals wTere advanced on the cal

endar of the Court of Appeals for oral argument and ex

pedited consideration on September 15, 1981. The opinion

of the Court of Appeals, however, was not filed until

May 7, 1982, one year after the hearing before the Dis

trict Court.

The Court of Appeals affirmed the result below. Al

though overruling the reasoning of the District Court

with regard to the bona tides of the city-wide seniority

system,10 the Court of Appeals concluded that the District

Court had the authority to modify the 1980 Decree upon

a showing of changed circumstances. The Court of Ap

peals also concluded that the interests of the Union in the

continued application of the city-wide seniority system

presented no impediment to such a modification. The

judgment of the Court of Appeals was filed on May 7,

1982 (J.A. 141-42). The Union’s petition for certiorari

was timely filed with the Court on August 4, 1982, and

a writ of certiorari was granted on June 6, 1983.11

9 Following a second hearing before the District Court on June 23,

1981 (J.A. 125-37), the preliminary injunction was expanded to

include three additional classifications not represented by the Union

(City Pet. A. 82-83).

10 See note 8, supra.

11 The City also applied for a writ of certiorari which was granted

by the Court and consolidated for review with the Union’s petition.

Memphis Fire Dep’t v. Stotts, 679 F.2d 541 (6th Cir. 1982), cert,

granted, 103 S.Ct. 2451 (1983) (No. 82-229).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

10

The orders in dispute impermissibly modified a con

sent decree that had been entered in a promotional dis

crimination case by enjoining the employer’s routine ap

plication of a seniority system to determine the order of

layoffs of municipal employees and by requiring the em

ployer to maintain the racial balance then existing in

each affected job classification. In doing so, the District

Court reached outside the “ four corners” of the consent

decree to impose a new provision allegedly to implement

its “purposes” in violation of the principles expressed by

the Court in United States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S.

673 (1971). The lower courts reached this result de

spite: (1) the absence of an adjudicated or admitted

violation of the law on the part of the parties affected

thereby, (2) the express waiver of additional relief con

tained in the consent decree itself and (3) the lack of

an ambiguity in the consent decree. Under these circum

stances, there was no basis for the imposition of a new

term or provision in the decree.

The lower courts exceeded their authority in modify

ing the consent decree. Due to the strong interests in

the finality of judgments, such a modification is permis

sible only where changed circumstances have transformed

the original decree into an “ instrument of wrong.”

United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106, 115 (1932).

The circumstances surrounding the municipal layoffs at

issue were not “ changed” circumstances as would justify

modification. Neither are the consequences of the routine

application of a bona fide seniority system “wrong” in

nature under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

the statute which the lower courts sought to enforce.

See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (h ). Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977).

Rather, the modification imposed by the lower courts is

itself “wrong,” as it impermissibly: (1) trammels the

interests of innocent nonminority incumbents to main

11

tain racial balance in favor of persons who had not es

tablished “ victim” status, (2) imposes a new duty on

petitioners in the absence of proper judicial proceedings

and (3) disregards the waiver of further relief that was

made by respondents. In addition, the orders below would

foster uncertainties regarding the finality of Title VII

settlements that would make the chances of future set

tlements much less likely.

The orders imposing the nonconsentual modification of

the consent decree had the effect of imposing involuntary

class-based relief which contravenes the directives of the

statutes that the lower courts sought to enforce. The

consent decree at issue neither constitutes an adjudica

tion nor an admission of a violation of the law on the part

of petitioners. Thus, the lower courts impermissibly im

posed substantial additional relief in the absence of a

proven or admitted violation of the law and despite re

spondents’ express waiver of such relief.

The orders below were outside the scope of the reme

dial authority under the statutes which respondents

sought to enforce. Those statutes specifically limit the

scope of permissible relief to making whole the “ victims”

of racial discrimination. See Franks v. Bowman Trans

portation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976) ; Milliken v. Bradley,

418 U.S. 717 (1974). Rather than granting relief to

individual “victims,” the relief ordered by the District

Court imposed a class-based quota remedy in contraven

tion of Title VII and its clear legislative history. In

nocent nonminority incumbents were displaced inequi

tably. The disputed orders constitute an abuse of dis

cretion, requiring reversal.

Finally, the lower courts disregarded the congressional

policy expressed in Title VII protecting routine applica

tion of a last-hired, first-fired seniority system. The or

ders below abrogated the routine operation of a bona fide

seniority system to impose a preference based on race.

In conferring “constructive” or “ fictional” competitive

12

seniority to junior black employees who had not demanded

such relief in the complaints or established their entitle

ment to such relief, the lower courts inequitably dis

placed more senior nonminority incumbents who are in

nocent of any wrongdoing. These black employees prof

fered no entitlement to preferential treatment other than

their race. The resulting orders run contrary to the

congressional directives embodied in §§ 703(h) and 703

(j) of Title VII.

ARGUMENT

I. THE; MODIFICATION OF THE: CONSENT DECREE

HEREIN TO IMPOSE A SUBSTANTIAL NEW PRO

VISION IN THE ABSENCE OF AN ADJUDICATED

VIOLATION OF THE LAW CONTRAVENES FUN

DAMENTAL PRINCIPLES GOVERNING JUDICIAL

INTERPRETATION AND ADMINISTRATION OF

CONSENT DECREES.

A. Consent Decrees Must Be Construed Within Their

“ Four Corners.”

The District Court modified a consent decree to im

pose a substantial new term affecting the petitioners.

This modification was ordered in the absence of any

adjudication of a violation of the law against petitioners

or admissions to that effect. The Union submits that

this modification constitutes clear error which requires

reversal.

The governing rule of construction, and its rationale,

were stated plainly and aptly by the Court in United

States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673, 681-82 (1971) :

Consent decrees are entered into by parties to a case

after careful negotiation has produced agreement on

their precise terms. The parties waive their right to

litigate the issues involved in the case and thus save

themselves the time, expense, and inevitable risk of

litigation. Naturally, the agreement reached nor

mally embodies a compromise; in exchange for the

saving of cost and elimination of risk, the parties

13

each give up something they might have won had

they proceeded with litigation. Thus the decree itself

cannot be said to have a purpose; rather the parties

have purposes, generally opposed to each other, and

the resultant decree embodies as much of those op

posing purposes as the respective parties have the

bargaining power and skill to achieve. For these

reasons, the scope of a consent decree must be dis

cerned within its four corners, and not by reference

to what might satisfy the purposes of one of the par

ties to it. Because the defendant has, by the decree,

waived his right to litigate the issues raised, a right

guaranteed to him by the Due Process Clause, the

conditions upon which he has given that waiver must

be respected, and the instrument must be construed

as it is written, and not as it might have been writ

ten had the plaintiff established his factual claims

and legal theories in litigation.

(Emphasis added; footnote omitted.) See also United

States v. Atlantic Refining Co., 360 U.S. 19 (1959) ;

Hughes v. United States, 342 U.S. 353 (1952).

Despite its citations to Armour (Pet. A. 23-24), the

Court, of Appeals failed to apply its substance. The Dis

trict Court determined that the proposed layoffs and der

motions under consideration were a circumstance “not

provided for in the text of the decree” (Pet. A. 8, 73).1:2

Neither respondents nor the Court of Appeals has chal

lenged this determination. It is manifest that the lower

courts have reached outside the “ four corners” of the

1980 Decree to impose a new obligation not agreed to by

the City in contravention of the principles stated in

Armour.

1:2 The Court of Appeals argues that the District Court “properly

recognized” that the respondents did not seek to. modify the decrees,

but merely sought to. “compel compliance with the terms and goals

of the decrees” (Pet. A. 33). The determination of the; District

Court referred to in the text demonstrates that this argument is

without merit. It is beyond cavil that the respondents sought relief

other than that expressly conferred by the language of the 1980

Decree.

14

Rather than mandating the result decreed by the courts

below, a reading of the “ four corners” of the 1980 Decree

requires that the City’s seniority system, as implemented

through the proposed layoff policy, should have been ap

plied. As no provision of the 1980 Decree addressed the

City’s layoff policies and procedures or prohibited the

City’s proposed layoffs and reductions in rank by senior

ity, the District Court’s injunction against such action

constituted additional affirmative relief beyond that pro

vided in the 1980 Decree. Further, the 1980 Decree con

tains respondents’ express agreement to “seek no- further

relief . . . save to enforce the provisions of this Decree,

thereby xoaiving the right to seek further relief’ (em

phasis added). The plain language of this waiver un

mistakably precludes respondents from seeking a modifi

cation even if adequate grounds for such a modification

might have existed otherwise.

Rather than limiting itself to an analysis of the “ four

corners” of the 1980 Decree, the Court of Appeals im

permissibly resorts to an interpretation of the purposes

and motivations of the 1974 and 1980 Decrees (Pet. A.

2, 3, 25, 36). This approach, as noted in Armour, im

permissibly invites consideration of how the decree might

have been written had the respondents established their

factual claims and legal theories in litigation. Armour,

402 U.S. at 682. By departing from the “ four corners”

of the 1980 Decree, the Court of Appeals exceeded its

authority.

B. In Interpreting a Consent Decree, the Court May

Not Consider Extrinsic Evidence Except To Resolve

an Ambiguity in the Terms of the Agreement.

The Armour “ four corners” rule is consistent with the

ordinary principle of contract construction that resort to

extrinsic evidence is permissible only when the decree

itself is ambiguous. See Fox v. United States Depart

ment of Housing and Urban Development, 680 F.2d 315,

319 (3d Cir. 1982). Otherwise, as Armour teaches, inter

15

probation of a consent decree is normally a question of

law based upon the instrument itself.

As noted above, the District Court determined that the

proposed layoffs and demotions were not provided for in

the text of the decree (Pet. A. 8, 73).13 As the 1974 and

1980 Decrees were silent in regard to layoffs, there is

clearly no ambiguity in the decrees that would call for

reference to extrinsic evidence to aid interpretation. The

consideration of such evidence by the courts below was

in error (Pet. A. 9 n.5, 31, 37). As Armour further in

dicates, the interpretation of a consent decree does not

rest on the subjective intent of the parties, rather it in

volves an interpretation of the meaning of the words used

by the parties. Fox, 680 F.2d at 320. The 1980 Decree

was silent, as to layoffs. In fact, neither relief from the

City’s layoff policies nor seniority relief was sought in

the respondents’ complaints (J.A. 11-12, 17). While the

1980 Decree was the result of “ intense negotiations”

(Pet. A. 2), the record does not demonstrate that con

structive competitive seniority, layoff practices or poli

cies or the potential for layoffs was considered. Certainly,

none of the subjects were addressed in the decree itself.

Respondents waived further relief in the face of the

city-wide seniority policy (J.A. 49), the mention of the

seniority system in the 1974 Decree (Pet. A. 8; J.A. 103)

and the explicit applicability of the seniority system to

layoffs contained in the Union’s Memoranda of Under

standing with the City (Pet. A. 81; J.A. 119). In light

of these considerations, the conclusion of the Court of

Appeals that the potential for seniority-based layoffs by

the City was an unanticipated change in circumstances

(Pet. A. 2) is in error. At the very least, it was capable

of anticipation by respondents. Indeed, it is now clear

that respondents seek the federal courts to bail them out

after they failed to complain about and failed to nego

113 The conclusion of the Court of Appeals to the contrary was in

error (Pet. A. 33).

16

tiate about layoffs, once confronted by actual layoffs. Re

spondents actually seek to have the courts rewrite their

settlement agreement for them after they failed to address

a subject they now see they should have addressed.

In point of fact, respondents failed to insist to im

passe, as it were, on the conferral of any constructive

competitive seniority. The record is quite clear that

Mayor Wyeth Chandler was opposed adamantly to the

abrogation of the seniority status of incumbent em

ployees. As the Mayor testified:

It is my opinion that/under the Consent Decree, we

agreed to hire, we agreed to promote, and we agreed

to do it in percentages, or what have you. And be

fair and equitable, and I felt that that was fair and

equitable, that I did then agree to it, consented to it.

But I certainly felt differently towards any policy

that would put people out of work, put them on the

street, based anything other than on the thing that

has been used in every city in this country, in every

business in this country, and by the city, and in the

Consent Decree since 1974, and that is the seniority

policy in the union agreement, and everything else.

(J.A. 37-38) Respondents certainly apprehended that

the terms of the 1980 Decree constituted the best nego

tiated setlement that could have been exacted from the

City. Rather than risking the potential for a less favor

able outcome at trial, respondents accepted a settlement

that gave them less than what might potentially have

been gained at trial. Respondents now seek to add to the

1980 Decree, through judicial modification, relief that

could not have been gained through negotiation and set

tlement.

The conclusion is inescapable that respondents have

not sought enforcement of the terms of the decrees as

required by Armour. Instead, respondents sought im

position of an additional term beyond the City’s consent.

The only prior instance in which this Court has endorsed

17

imposition of new and substantial burdens on a defend

ant party to a consent decree, United. States. v. United

Shoe Machinery Co., 391 U.S. 244 (1968) (see discus

sion in Fox, 680 F.2d at 323), is inapposite due to lack

of an adjudication of a violation of the law herein to

support the imposition of such burdens. In the instant

circumstance, it is impermissible for respondents to draw

on a consent which, by its very terms, is not available.

See Ford Motor Co. v. United States, 385 U.S. 303, 322

(19481. The: City had not agreed to constructive com

petitive seniority relief or to any relief which affected

the routine application of its seniority system, as clearly

stated by Mayor Chandler (J.A. 37-38).

C. Nonconsentual Modification of a Consent Decree

May Be Allowed Only upon the Establishment of

a Proper Predicate Absent Herein.

The Court of Appeals framed the principal issue raised

on appeal in terms of “whether the District Court erred

in modifying the 1980 Decree to prevent minority em

ployment from being affected disproportionately by unan

ticipated layoffs.” (Pet. A. 12) Even if the courts below

were not limited to an interpretation of the “ four cor

ners” of the 1980 Decree under Armour,14 those courts

were still without authority to modify the 1980 Decree to

afford respondents additional relief beyond the scope of

that relief conferred by the language of the decree.

Respondents have not sought enforcement of an ex

isting term of the 1980 Decree, but imposition of an

additional term beyond the scope of petitioners’ consent.

There can be no serious contention that petitioners have

violated the terms of the 1980 Decree (Pet. A. 75). Cf.

United States v. ITT Continental Baking Co., 420 U.S.

223 (1975). Neither did the City announce its intention

to renounce or repudiate its commitment to achieving the

14 The: Union contends that this should be the case for the reasons

noted above:, particularly in light of the respondents’ express waiver

of additional relief. (See Pet. A. 61).

IS

long-term goals contained in the 1974 and 1980 Decrees

as the Court of Appeals intimates (Pet. A. 33). Thus,

the Court must determine whether, in the absence of an

adjudication of a violation of the law or a showing of a

violation of the terms of the decree, the lower courts have

the authority to modify the 1980 Decree to impose a new

term not previously agreed to by the petitioners.

The standard for reopening a consent decree is a strict

one; the: relief is extraordinary and may be granted only

upon a showing of exceptional circumstances. Fox, 680

F.2d at 322. There are strong interests in the finality of

the judgment of the District Court as embodied in the

1980 Decree. In fact, when the respondents have made

“a free, calculated and deliberate choice to submit to an

agreed upon decree rather than seek a more favorable

litigated judgment their burden . . . is perhaps even

more formidable than had they litigated and lost.” Id.

Respondents failed to carry their burden and should not

have been granted a modification.

While courts exercising their equitable jurisdiction are

not powerless to alter the terms of a prospectively operat

ing consent decree, this power must only be exercised

with circumspection. Modification must not be allowed

unless changed circumstances have transformed the origi

nal decree into an “ instrument of wrong.” United States

v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106, 115 (1932). Nothing less

than a “ clear showing of grievous wrong evoked by new

and unforeseen conditions” should lead a court to change

or modify the terms of the original decree. Id. at 119.

The Court of Appeals justified its affirmance of the Dis

trict Court on the basis that the 1980 Decree had been

transformed into an “ instrument of wrong” by new and

unforeseen circumstances constituting a “ fundamental

change in the essential facts upon which the decree

[was] based” (Pet. A. 34-37). The Union takes excep

tion to this conclusion and the premises on which it is

based.

19

The essential facts upon which the 1980 Decree was

based, that the respondent class was involved in an

employer-employee relationship in a circumstance in which

city-wide seniority was a relevant factor in certain job

decisions, including potential layoffs, had, in fact, not

changed as a result of intervening circumstances since

the entry of the 1980 Decree. Nor had the City aban

doned or repudiated the long-term goal agreed to in the

1980 Decree, as the Court of Appeals suggests (see Pet.

A. 33). Neither were the lower courts justified in their

conclusion that the potential for layoffs was unforeseen.

The record is clear that the City and the Union antici

pated the potential for layoffs as early as 1975 when

the following language was included in their Memoran

dum of Understanding:

Layoff— In the event it becomes necessary to reduce

the Fire Division, seniority alphabetically shall gov

ern lay-offs and recalls. Employees lowest in senior

ity shall be laid off first and shall be the last to be

recalled.

(Pet. A. 81, J.A. 115). The fact that respondents failed

to anticipate the potential for future layoffs when they

acceded to a waiver of further relief in the 1980 Decree

does not justify a finding that the potential for layoffs

was unforeseen or unforeseeable in the instant case.

The prospects for layoffs and reductions in force in

the City of Memphis Fire Division must also be viewed

in light of the instances of such layoffs in other munici

palities in the relevant period. A survey of 100 cities

conducted in November, 1981 by the U.S. Conference of

Mayors indicated that 72 of those cities surveyed had

laid off employees or were expecting to lay off employees

in the near future. Bureau of National Affairs, Layoffs,

RIFs and EEO in the Public Sector, Fair Employment

Practices Supplement 439, February 13, 1982, p. 23-24.

Similar layoffs had previously arisen within the juris

diction of the Sixth Circuit in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1976,

20

Youngblood v. Dalzell, 568 F.2d 506 (6th Cir. 1978), and

in Toledo, Ohio in 1980, Brown v. Neeb, 644 F.2d 551

(6th Cir. 1981).

The Union also challenges the Court of Appeals’ as

sertion that the 1980 Decree had been transformed into

an “ instrument of wrong.” The “wrong” complained of

is that the 1980 Decree, if not modified, would permit

the application of the city-wide seniority system in deter

mining the order of layoffs and reductions in rank. The

routine application of the city-wide seniority system would

have had the effect of temporarily reducing the percentage

of blacks in the affected job classifications.15 The Court

of Appeals’ value judgment that the routine application

of the city-wide seniority system constituted a “wrong”

ignores the clear statement of congressional policy em

bodied in § 703(h) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Sec

tion 703(h) clearly stands for the; proposition that, the

routine application of a bona fide seniority system is not

a. “wrong.” Since a district court’s authority to adopt a

consent decree arises only from the statute the decree is

intended to enforce, System Federation No. 91 v. Wright,

364 U.S. 642, 651 (1961), its authority to modify a de

cree enforcing such a statute can only be exercised in

light of the policies of the statute.

In the area of employment discrimination, the routine

application of systems of competitive seniority which

have been created or operated without a racially dis

criminatory purpose has been immunized from the statu

tory proscriptions against employment practices which,

although neutral on their face and in intent, nonetheless

discriminate in effect against a particular group. Team

sters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 348-54 (1977). 16

16 Mayor Wyeth Chandler testified that the effects o f the layoffs

and reductions in rank were anticipated to be temporary in nature,

for example that lieutenants who were bumped down would be back

“ in rank’’ within a. six-month to two'-year period (J.A. 39).

21

Section 703(h) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (h) , specifically provides:

Notwithstanding any other provision of this sub

chapter, it shall not be an unlawful employment prac

tice for an employer to apply different standards of

compensation, or different terms, conditions, or privi

leges of employment pursuant to a bona fide senior

ity . . . system, . . . provided that such differences

are not the result of an intention to discriminate be

cause of race . . . or national origin, . . .

As this Court concluded in Teamsters, “ the unmistak

able purpose of § 703(h) was to make clear that the rou

tine application of a bona fide seniority system would

not be unlawful under Title VII.” 431 U.S. at 352. In

so holding, the Court acknowledged that the longest ten

ure employees, even though they might without excep

tion be white, would enjoy a “ ‘disproportionate distribu

tion of advantages [which] in a very real sense [would]

operate to ‘freeze’ the status quo of prior discriminatory

employment practices.’ ” 431 U.S. at 350. Nevertheless,

this Court recognized that this perpetuation effect could

not overcome “ the congressional judgment . . . that Title

VII should not outlaw the use of existing seniority lists

and thereby destroy or water down the vested seniority

rights of employees. . . .” 431 U.S. at 353.

The city-wide seniority system in this case was adopted

as an employment policy of the City of Memphis in 1973

(J.A. 49), and has been present in the City’s Memoranda

of Understanding with the Union since 1975 (Pet. A. 80-

81; J.A. 49, 116-19). Respondents have at no time

mounted any challenge to the genesis or operation of

this system. The system is clearly neutral and nondis-

criminatory. Its continued operation is therefore correct

and proper under Title VII, even though it may perpetuate

the effects of past discrimination by the employer.1'6 16

16 The seniority system is valid under both the United States

Constitution and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 absent a showing of discrimina

22

The Court of Appeals chose to ignore the clear con

gressional statement of policy and to impose on the par

ties its own opinion concerning the “wrongness” of the

routine application of the city-wide seniority policy to

layoffs. In fact, the modification of the 1980 Decree re

sulted in a “wrong” inflicted on innocent nonminority

incumbents who lost their rank and their jobs as a re

sult of the modification. To the extent that these incum

bents were so affected, the lower courts impermissibly

“ trammel [ed] the interests of the white employees” and

sought to “ maintain racial balance” at the expense of

innocent nonminority incumbents. Cf. United Steelwork

ers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 208 (1979), reh’g

denied, 444 U.S. 889 (1980).17

It is important to note that the question for decision

in this case is whether the 1980 Decree should have been

tory purpose in its inception or operation. See Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229 (1976) (Fourteenth Amendment); General Bldg. Con

tractors Ass’n, Inc. v. Pennsylvania, 102 S.Ct. 3141 (1982) (§ 1981).

Title VII was made applicable to the City by the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Act of 1972 (Pub. L. 92-261, Mar. 24, 1972).

Thus, any discriminatory practices on the part of the City predating

March 24, 1972 would not have been actionable under Title VII. In

this case, the! relevant time period for actionable discrimination

dates back only to February 23, 1975, 180 days prior to Mr. Stotts’

charge filed before the EEOC. Pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and

1983, respondents could only seek a remedy for intentional discrimi

nation, General Bldg. Contractors Ass’n v. Pennsylvania, 102 S.Ct.

3141 (1982) ; Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), that took

place within one year of the filing of the original complaint herein

on February 16, 1977 (J.A. 1, 8).

17 As a result, the class-based relief imposed upon petitioners by

the lower courts in order to maintain the percentage of blacks in

each job classification exceeds even that relief to: which the City

and respondents might have permissibly consented. See Weber, 443

U.S. at 208. The Court of Appeals acknowledged that the terms of

the decree cannot require the discharge o f nonminority workers and

their replacement with minorities (Pet. A. 16). It is quite peculiar

that the Court of Appeals would conclude that a consent decree

could be modified after the fact to provide relief that would have

been impermissible if contained in the decree as originally drafted.

23

modified to impose a duty that was not contained therein,

and not, as in Swift, whether the defendant should be

released from the obligations imposed by the decree. The

instances in which such a result has been approved by

this Court in prior cases have been limited to those

circumstances in which the decree was entered after an

adjudication or an admission of a violation of the law

on the part of the defendant party to the decree. See

Fox, 680 F.2d at 323. Both the 1974 and 1980 Decrees

contained nonadmissions clauses (Pet. A. 60; J.A. 99).

The 1974 Decree provided that it “ shall not constitute

an adjudication or admission by the City of any violation

of law or findings on the merits of this case” (J.A. 99).

Where there has been no adjudication or admission of a

violation of the law, as in this case, the proper predicate

does not exist for the imposition of additional relief with

out the consent of the parties affected thereby. See United

States v. Atlantic Refining Corp., 360 U.S. 19, 23 (1959) ;

Hughes v. United States, 342 U.S. 353, 357-58 (1952) ;

Fox, 680 F.2d at 323. As the consent decrees involved

herein were entered without an admission or an adjudi

cation of a violation of the law and without fact findings

that would support the imposition of further relief, the

proper predicate did not exist for the nonconsentual mod

ification of the 1980 Decree over petitioners’ objections.

Apparently, the Court of Appeals acknowledged the

need for an admission of a violation to support the im

position of additional relief. To find an admission, the

Court of Appeals would stretch the City’s disclaimer of

wrongdoing beyond recognition and into an admission of

wrongdoing:

In the context of consent decrees providing affirma

tive action relief, we interpret the disclaimer of

wrongdoing to be an admission that there is a statis

tical disparity which the defendants cannot unequiv

ocally explain, together with a reservation of the

right to attempt to explain it at any other time.

24

(Pet. A. 15 n.10) (Citations omitted) Such an inter

pretation of a disclaimer of wrongdoing, if allowed to

stand, would have a serious negative impact upon the

potential for future settlement of Title VII litigation.

Even if under some “ exceptional” circumstances a

court might have the authority to modify a consent decree

over the objection of defendant parties thereto or impose

new obligations in the absence of an admission or ad

judication of a violation of the law, such exceptional cir

cumstances do not exist herein. Viewed in their best

light, respondents’ contention is that their expectations

would have been frustrated by the seniority-based lay

offs caused by fiscal circumstances beyond the control of

the City that might have been anticipated by respondents

and addressed in negotiations with the City. Such a cir

cumstance does not constitute an “ exceptional” circum

stance. Accord Fox, 680 F.2d at 323. The municipal lay

offs in this case was a possibility that respondents should

have considered or anticipated for the reasons detailed

above. Also, the petitioners had not been guilty of mis

conduct that might have made equitable the imposition

of involuntary duties without a prior adjudication.18

Rather than demonstrating the existence of exceptional

circumstances which might make equitable the reopening

of the 1980 Decree to provide further relief to respond

ents, the record establishes that the modification was

inequitable. Respondents waived their entitlement to fur

ther relief beyond that granted by the strict terms of the

1980 Decree (Pet. A. 61). To impose additional duties

under the 1980 Decree is to disregard the basic rights of

18 Despite the Court of Appeals’ citations to Brown v. Neeb, that

case is distinguishable from this case. Unlike Brotvn, the City is not

an adjudicated discriminator, as was the City of Toledo. See 644

F.2d at 553. Respondents could not establish that the City had

been recalcitrant in its compliance with the obligations imposed by

the 1974 and 1980 Decrees. Unlike Brown, the City had approached

or exceeded its hiring goals (J.A. 48). It was not established that

the City had been defiant or contemptuous (Pet. A. 74-75).

petitioners who waived their right to litigate defenses by

consenting to have a decree entered against them. The

conditions upon which rights are waived must be re

spected. Armour, 402 U.S. at 682.

The Court of Appeals’ analysis would subject parties

to a consent decree to a virtually unlimited power of

modification by district courts whose lodestar would be

their determination of what the parties would have

agreed to on a certain issue if, indeed, they had thought

about it. Rather than encouraging compromise and set

tlement, this approach fosters uncertainties that reduce

the incentive of employers and unions to settle employ

ment discrimination litigation and increases the likeli

hood of challenges from concerned third parties, particu

larly labor unions in cases in which they are not parties.

Thus, the Court of Appeals’ analysis actually makes the

chances of settlement in an employment discrimination

case much less likely due to remaining uncertainties as

to what changes a district court could make in the decree

in the future.

IL THE INVOLUNTARY CLASS-BASED RELIEF

GRANTED BELOW CONTRAVENES THE STAT

UTES THE COURTS SOUGHT TO ENFORCE.

A. The Order of the District Court Granted Relief in

Addition to that Sought in the Complaint and

Granted in the Decrees Without Establishing Peti

tioners’ Liability or Respondents’ Entitlement to the

Relief.

By the 1974 Decree, the City agreed to a long-term

goal of “ achieving throughout the work force proportions

of black and female employees in each job classification,

approximating their respective proportions in the civilian

work force.” (J.A. 101) To achieve this goal, the City

agreed to interim hiring goals in entry level positions

(Pet. A. 63-65; J.A. 101). The 1980 Decree supplemented

this relief previously agreed to by providing promotional

goals (Pet. A. 65-66) and monetary relief in the form of

backpay (Pet. A. 66).

25

26

The 1980 Decree recites that respondents had brought

actions against the City alleging violations of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e, et

seq., as amended and made applicable to the City by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 and 42

U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983. The City, however, did not ad

mit to having violated the law by discriminating on the

basis of race or sex in its employment practices (Pet. A.

60), nor had a violation of the law been adjudicated or

admitted by petitioners in any other context (see J.A.

99). Neither decree endeavored to identify particular

victims as being actual victims of discrimination.

By the nonconsentual modification of the 1980 Decree,

the lower courts exceeded their remedial authority. As

pointed out in Part I, supra, the lower courts could not

draw their authority to modify the 1980 Decree from its

terms. In addition, the record before the District Court

is insufficient to support the relief ordered herein under

the applicable statutes.

The relief imposed upon the petitioners modified the

1980 Decree to forbid the City from applying the city

wide seniority policy “ insofar as it will decrease the per

centage of black [firefighters in certain job classifica

tions] that are presently employed in the Memphis Fire

Department.” (Pet. A. 78, City Pet. A. 80, 83) As a re

sult of these orders, the City was required to lay off and

reduce in rank more senior incumbent nonminority em

ployees to maintain the precise racial balance previously

existing in each job classification affected by the order.

The first infirmity of the judicially imposed modifica

tions is that those orders afford respondents substantial

relief in the absence of a proven violation of the law. The

orders below bypass the “ liability” phase of litigation and

enter the remedial phase without the support of a proven

finding of discrimination on the part of petitioners.18 19

19 See D. Dobbs, Handbook on the Law of Remedies, § 1.1 (1973).

The law of judicial remedies concerns itself with the nature and

scope of the relief to be given a plaintiff once he has followed

27

As the 1980 Decree was not grounded on findings of

discrimination against petitioners, no further relief was

appropriate beyond that originally granted in the decree

itself, particularly in view of respondents’ express waiver

of further relief (Pet. A. 61). Even if the proof sub

mitted to the District Court at the preliminary injunction

hearing was adequate to raise some inference of discrim

ination, respondents had additionally “waive [d] a hearing

and findings of fact and conclusions of law on all issues

raised by the complaints.” (Pet. A. 60)20 Thus, even if

the respondents had prayed for constructive competitive

seniority in their complaints, which they did not, that

potential relief was lost at the time the 1980 Decree was

entered.

appropriate procedure in court and has established a substan

tive right (Emphasis added).

In accordance with these principles, this Court has observed that

district courts must limit nonconsentual relief to circumstances in

which an illegal discriminatory act or practice is proven or found.

See Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747, 758 (1976).

20 After the City articulated its reasons for implementing

seniority-based layoffs (see, e.g., J.A. 37-38, 43-44), the ultimate

burden of persuasion remained with respondents. As the Court

explained in. Ford Motor Co. v. EEOC, 102 S.Ct. 3057 (1982) :

In Burdine we reiterated that after a plaintiff has proved a

prima, facie case of discrimination, “the burden shifts to the

defendant ‘to articulate some legitimate;, nondiscriminatory rea

son for the employee’s rejection.’ ” The “ultimate burden of

persuading the trier of fact that the defendant intentionally

discriminated against the plaintiff remains at all times with

the plaintiff.” It was then made clear that:

“ The defendant need not persuade the Court that it was ac

tually motivated by the proffered reasons. . . . It is sufficient if

the defendant’s evidence raises a genuine issue of fact as to

whether it discriminated against the plaintiff.”

Id. at 3062 n.7 (citations omitted; emphasis added). The courts

below ignored this, method of analysis and implemented a remedy

without a supporting finding of discrimination.

28

B. A Court May Not, in Order To Achieve a Particular

Racial Balance, Direct that Innocent Incumbent

Employees Be Deprived of Their Jobs so that Those

Jobs May Be Filled by Persons of Another Race

Who Have Not Been Adjudicated as Victims of

Unlawful Discrimination.

Even if the initial infirmity, lack of a proven violation

of the law, was not present, the Union submits that the

orders of the lower courts must be reversed as being be

yond the scope of the District Court’s remedial authority.

As set forth above, respondents sought relief in their com

plaints for alleged violations of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e, et seq., as

amended by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972 and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983. While violations

of these statutes have not been proven against petitioners,

these statutes provided the basis for any relief to which

respondents might have been entitled, even had these cases

been fully litigated.

Where private litigants assert claims arising under

federal statutes, federal courts may exercise their juris

diction to fashion relief only to the extent consistent with

the applicable statute. See System Federation No. 91,

364 U.S. at 651. When the authority of the federal courts

derives from an act of Congress, substantive rights sim

ply do not exist if they are not created by the statute.

“ [I]n our constitutional system, the commitment to the

separation of powers is too fundamental for [the courts]

to pre-empt congressional action by judicially decreeing

what accords with ‘common sense and the public will.’ ”

TV A v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153, 195 (1978).21

21 Title VII, of course, epitomizes Congress’ formulation of public

policy. When Congress so acts, it supplants with its own views any

judicial determination of public policy. Cf. United States v. Atlantic

Mutual Ins. Co., 343 U.S. 236, 245 (1952) (Frankfurter, J., dissent

ing). Compare Holmberg v. Armbrecht, 327 U.S. 392, 395 (1946)

with Northwest Airlines Inc. v. Transport Workers, 451 U.S. 77

(1981).

29

Thus, the pertinent inquiry is whether Title VII and

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983 authorize the relief afforded

respondents by the lower courts.22 23 The focus of these

statutes is to afford protection to individuals, not to mi

nority groups as a whole.23 It is clear that the relief

available under §§ 1981 and 1983 is limited to relief to

actual victims of discrimination. As the Court has stated:

. . . the remedy is necessarily designed, as all reme

dies are, to restore the victims of discriminatory con

duct to the position they would have occupied in the.

absence of such conduct.

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 746 (1974) ( “ Milliken

I” ) ; see also Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 281

(1977) (“ Milliken II” ). Also, the remedies specified un

der Title VII to rectify illegal employment discrimination

are consistent with and define the scope of relief avail

able in the instant context under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and

1983.

The choice of law provision, 42 U.S.C. § 1988, specifies

the law to be applied to remedy violations of 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981 and 1983. This section provides in pertinent

part:

The jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters con

ferred on the district courts by the provisions of this

Title . . . for the protection of all persons in the

United States, in their civil rights, and for their

22 The Union, would show that this inquiry is largely academic in

the absence of a proven violation of these statutes on the part of

petitioners. No- violation having been found, it was simply beyond

the power of the District Court to fashion a remedy for a wrong

that had not been proven.

23 See Connecticut v. Teal, 102 S.Ct. 2525, 2534 (1982) ( “The

principal focus of [Title VII] is the protection of the individual

employee, rather than the protection of the minority group as a

whole. Indeed, the. entire statute and legislative history are replete

with references to protection for the individual employee. See, e.g.,

§§ 703(a) (1), (b ), ( c )____” ) (Title V II ) ; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U.S. 1, 22 (1948) (constitutional violations).

30

vindication, shall be exercised and enforced in con

formity with the laws of the United States so far as

such laws are suitable to carry the same into

effect. . . .

“This means, as we read § 1988, that both federal and

state rules on damages may be utilized, whichever better

serves the policies expressed in the federal statutes.”

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 240

(1969). As § 706(g) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (g) defines the remedies that

a court may order upon finding employment discrimina

tion, application of § 706(g) in providing remedies for

violations of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983 in the employ

ment discrimination context best serves the policies ex

pressed in those federal statutes.

The remedial provision of Title VII, § 706(g), contains

a limitation in its last sentence that bars the relief pre

scribed by the lower courts. That sentence reads in per

tinent part:

No order of the court shall require the . . . reinstate

ment of an individual as . . . an employee . . . if such

individual . . . was suspended or discharged for any

reason other than discrimination on account of race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin. . . .

This section requires a court “ to fashion such relief as

the particular circumstances of a case may require to

effect restitution, making whole insofar as possible the

victims of racial discrimination in hiring.” Franks v.

Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 764 (1976)

(footnote omitted) ; accord, Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 364.

The District Court’s orders in this case are contrary to

both the language and spirit of this provision.

The District Court’s orders afforded relief to members

of the respondent class on the basis of their race alone

without consideration of whether the individual members

of the class were actual victims of discrimination. Those

orders explicitly sought to maintain the racial balance

31

then prevailing in each affected job classification (Pet.

A. 78). Obviously, as no violations of the law had been

proven against petitioners in regard to the class, no in

dividuals could claim proven victim status. Instead of

limiting relief to victims, the District Court ruled that

the layoffs could only proceed if the respondent class was

not disproportionately affected thereby. To the extent

that it did so, the District Court imposed for the first

time in this litigation strict quotas upon the racial bal

ance in the work force.

In addition to the plain language of § 706(g), the leg

islative history of Title VII demonstrates that Congress

meant to forbid such a result. The opening speech on the

floor of the House of Representatives in support of the

Act was delivered by Representative Celler, the Chairman

of the House Judiciary Committee. A portion of that

speech was devoted to answering the “unfair and unrea

sonable criticism” that had been leveled against the bill:

In the event that wholly voluntary settlement proves

to be impossible, the Commission could seek redress

in the federal courts, but it would be required to

prove in the court that the particular employer in

volved had in fact, discriminated against one or more

of his employees because of race, religion or national

origin. . . .

Even then, the court could not order that any pref

erence be given to any particular race, religion or

other group but would be limited to ordering an end

to discrimination [110 Cong. Rec. 1518 (1964)].

Subsequent to the House’s passage of the bill, the Re

publican sponsors in the House published a memorandum

describing the bill as passed. In pertinent part, the

memorandum stated:

Upon conclusion of the trial, the federal court may

enjoin an employer or labor organization from prac

ticing further discrimination and may order the hir

ing or reinstatement of an employee or the accept

32

ance or reinstatement of a union member. But Ti

tle VII does not 'permit the ordering of racial quotas

in business or unions and does not permit interfer

ences with seniority rights of employees or union

members. [Id. at 6566; emphasis added].

When the bill was taken up by the Senate, Senators

Humphrey and Kuchel, the co-managers of the bill, under

took a description of each of the titles. In the course of

his description of Title VII, Senator Humphrey detailed

the manner in which discrimination claims could be proc

essed through suit and finding of discrimination, and then

described the remedial powers available to a court:

The relief sought in such a suit would be an injunc

tion against future acts or practices of discrimina

tion, but the Court could order appropriate affirma

tive relief, such as hiring or reinstatement of em

ployees and payment of backpay. This relief is simi

lar to that available under the National Labor Rela

tions Act in connection with the unfair labor prac

tices, 29 United States Code 160(b). No court order

can require hiring, reinstatement, admission to mem

bership, or payment of back pay for anyone who was

not fired, refused employment or advancement or ad

mission to a union by an act of discrimination for

bidden by this title. This is stated expressly in the

last sentence of section 707(e) [enacted, without