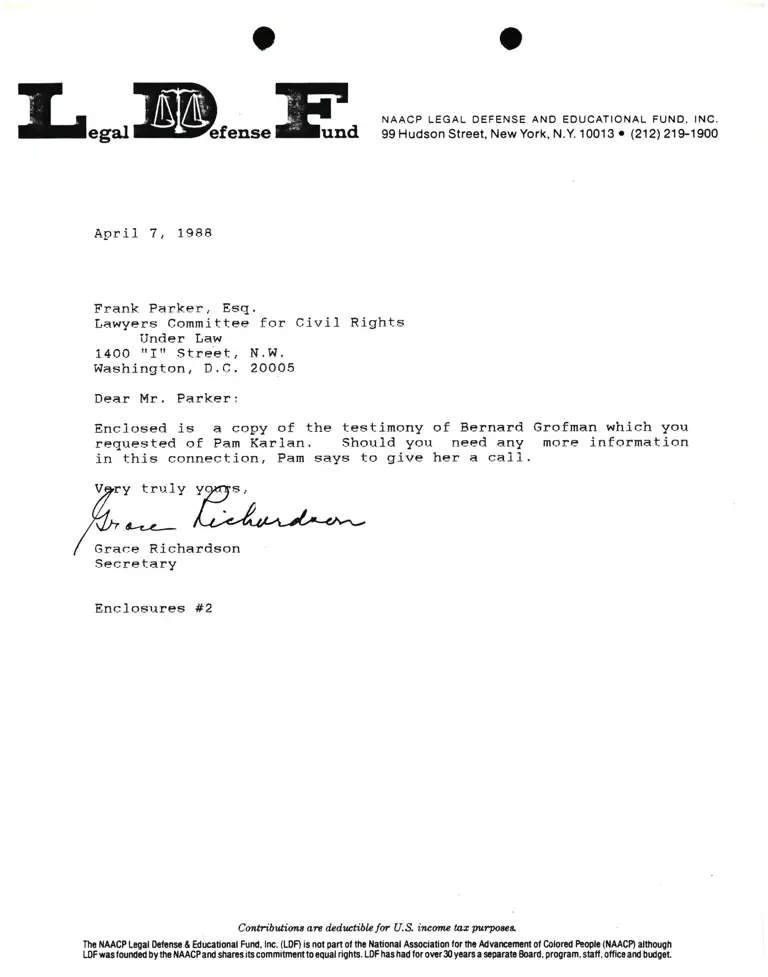

Correspondence from Grace Richardson to Frank Parker(Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights)

Correspondence

April 7, 1988

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Grace Richardson to Frank Parker(Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights), 1988. 124efbe3-ec92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db67432e-6117-4185-85d9-a6935b1d5666/correspondence-from-grace-richardson-to-frank-parker-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

Lesar@renseH"

ApriI 7, 1988

Frank Parker, Esq

Lawyers Committee

Under Law

14OO itJ'' Stre'et,

Washington, D.C.

Dear Mr. Parker:

Enclosed is a copy of

regr-rested of Pam Kar1an

in this conneetion, Pam

for Civil Rights

N . 9,i.

20005

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, New york, N.y. 10013 o (2121219-1900

the testimony of Bernard

. Should yor.r need any

says to give her a call.

Grofman which you

more information

|ty

trrrly yp*

krL-c*- l'r>

/ or^"" Richardson

Secretary

Enclosures #2

Contri.bntions orc dcdutihla for U.S ituottu ta.a pul?prr,&

Ihe NMCP Legal t)cfcnsc & &rraUonel Fund, Irc. (LDF) is not pan ol $t tlatonal AssociaUon tor thc Adwrclmrnt ol Colorud Pcoplc (tlMCP) although

OFwagloundld byurltMCPand sllaItsiEcommimfittocqualriChb. LDFhashadlorowrXlycarsa slpanb Board, proCram, shlt, orltctand bdCrt