Wisconsin v. Mitchell Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 28, 1993

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wisconsin v. Mitchell Brief Amicus Curiae, 1993. 5e3b4360-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db6d1424-b04b-423e-9e28-cd6a7af4832f/wisconsin-v-mitchell-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

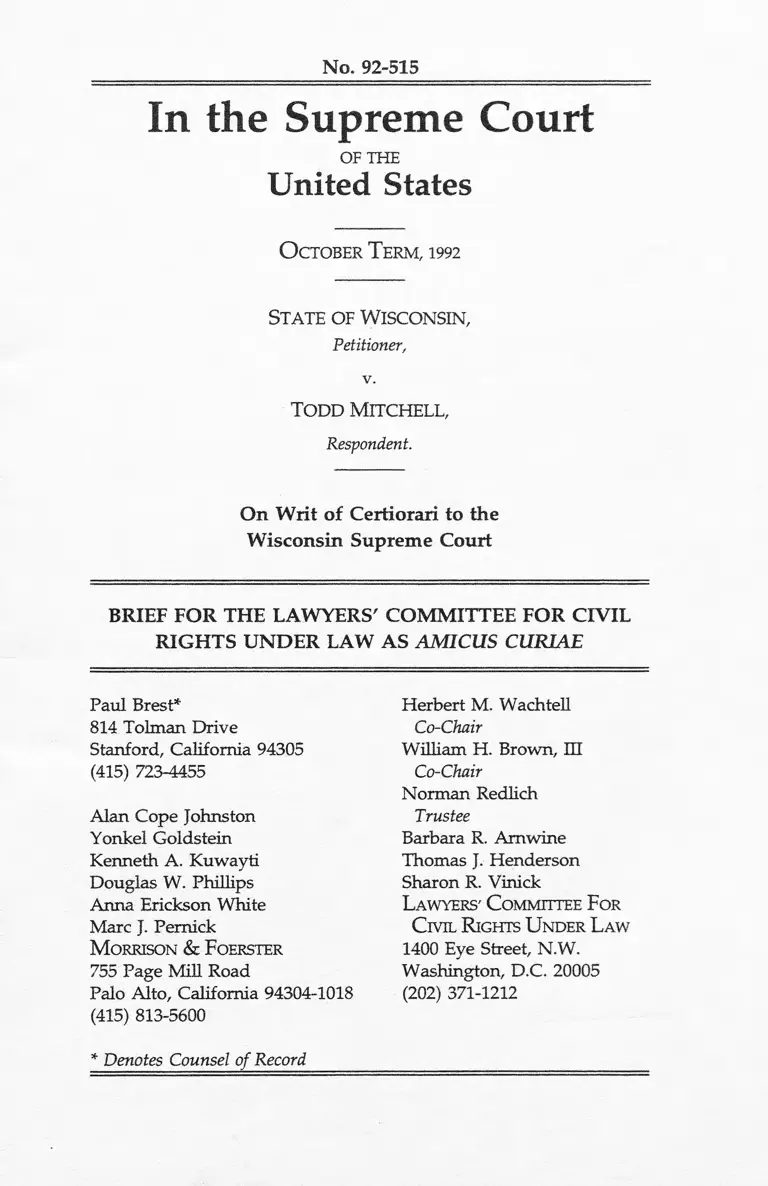

No. 92-515

In the Supreme Court

OF THE

United States

O c t o b er T e r m , 1992

S t a t e o f W is c o n s in ,

Petitioner,

v.

TODD MITCHELL,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Wisconsin Supreme Court

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

Paul Brest*

814 Tolman Drive

Stanford, California 94305

(415) 723-4455

Alan Cope Johnston

Yonkel Goldstein

Kenneth A. Kuwayti

Douglas W. Phillips

Anna Erickson White

Marc J. Pemick

M orrison & F oerster

755 Page Mill Road

Palo Alto, California 94304-1018

(415) 813-5600

* Denotes Counsel of Record

Herbert M. Wachtell

Co-Chair

William H. Brown, HI

Co-Chair

Norman Redlich

Trustee

Barbara R. Amwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Sharon R. Vinick

L awyers' C ommittee F or

C ivil R ights U nder L aw

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

- 1 -

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does the First Amendment to the United States

Constitution prohibit states from providing greater maximum

penalties for crimes if a fact-finder determines that a criminal

offender intentionally selected his or her crime victim because

of the victim's race, color, religion or other specified status?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

___________________________________________________ Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .............................................. v

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ........................ 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ......................................... 2

ARGUMENT............................... 4

I. ENHANCING THE PUNISHMENT FOR A

CRIME COMMITTED BECAUSE OF THE

VICTIM'S RACE OR STATUS DOES NOT

HAVE EVEN AN INCIDENTAL EFFECT

ON SPEECH ......................................... 4

A. Government Regulation of Discriminatory

Conduct Does Not Implicate Freedom of

Speech................ 5

B. Weighing a Defendant's Selection of

the Victim in Ascertaining a Criminal

Sentence Is Consistent with Other

Criminal Statutes................................................ . 10

II. EVEN IF THE COURT WERE TO DETERMINE

THAT SECTION 939.645 INCIDENTALLY

AFFECTS EXPRESSION, IT DOES NOT

VIOLATE THE FIRST AMENDMENT ................... 16

- ii -

- Ill -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(Continued)

Page

A. Statutes That Regulate Conduct Rather

Than Speech Are Analyzed Under a Four-

Prong Test .......................................................... 17

B. Section 939.645 Fully Meets the

Four-Prong Test ......................................... 17

1. The State of Wisconsin Clearly

Has the Power to Enact Laws

Criminalizing Discrimination............ .. 18

2. Section 939.645 Furthers Several

Important Governmental Interests . . . . . 18

a. Section 939.645 Legitimately

Protects the Community's Sense

That Status-Dependent Crimes

Are Inherently More Reprehensible

Because of Their M otivation............ .. . 19

b. Status-Dependent Violence Has an

In Terr orem Effect on Members of

the Victim's Community and Is

More Socially Disruptive ...................... 20

- IV -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(Continued)

Page

c. Crimes Motivated by the Status

of the Victim May Be More

Difficult to Deter Than Other

Crimes . .................... ..................... .. 21

3. Section 939.645 Is Unrelated to the

Suppression of Speech . ................................ 22

4. The Incidental Restriction on Speech,

if Any, Caused by the Wisconsin

Statute Is No Greater Than Necessary

to Further the Governmental Interests

Served by Section 939.645 ........................... 23

CONCLUSION 23

- V -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

_________________________________________________Page(s)

Cases

Abrams v. United States,

250 U.S. 616 (1919)___ . . . . . . . ------- . . . . . . . 23

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan,

372 U.S. 58 (1963)................................................ .. ■ 9

Barclay v. Florida,

463 U.S. 939 (1983) ............................... ................ 19

Barnes v. Glen Theatre, Inc.,

_ U.S. 111 S. Ct. 2456 (1991) . . . . . . . ----- 19

Boos v. Barry,

485 U.S. 312 (1988) ........................... .. .................... 11

Bray v. Alexandria Women's Health Clinic,

___U .S .___ , 61 U.S.L.W. 4080 (1993) . . . . ___ 9

CISPES (Committee in Solidarity with the

People o f El Salvador) v. Federal Bureau of

Investigation,

770 F.2d 468 (5th Cir. 1985) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Coker v. Georgia,

433 U.S. 584 (1977)___ _____ . . . 21

- vi -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Continued)

Dawson v. Delaware,

_ U.S. 112 S. Ct. 1093 (1992) ........................ 19

Ex Parte Virginia,

100 U.S. 339 (1880)...................... ............................ 10

Griffin v. Breckenridge,

403 U.S. 88 (1971)...................................................... 7

Hishon v. King & S-palding,

467 U.S. 69 (1984) . ................................................... 5

Jacobson v. Massachusetts,

197 U.S. 11 (1905) .................... ................................. 18

Jurek v. Texas,

428 U.S. 262 (1976) .................... ............................ .. 14

Mistretta v. United States,

488 U.S. 361 (1989) .................................................... 14

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama,

357 U.S. 449 (1958)....................................... ........... 6

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,

376 U.S. 254 (1964).................................................. 9

Norwood v. Harrison,

413 U.S. 455 (1973)................................. ................ 6

___ _____________________________________________ Page(s)

- vii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Continued)

Page(s)

Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton,

413 U.S. 49 (1973).......................... .. 19

Pell v. Procunier,

417 U.S. 817 (1974) . . . . . . . . . . . . ___ _ _____ 22

Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v.

Feeney,

442 U.S. 256 (1979) . . . . ....... ................................. 9

RA.V. v. City of St. Paul, Minnesota,

_ U.S. 112 S. Ct. 2538 (1992) ................. .. 16, 21

Roberts v. United States Jaycees,

468 U.S. 609 (1984) ................................................... 7

Runyon v. McCrary,

427 U.S. 160 (1976) ........................... 6 ,7

South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 U.S. 301 (1966) .................................. .. ............. 10

State v. Beebe,

680 P.2d 11 (Or. App. 1 9 8 4 )___ . . . . . . . . . . . 21

State v. Mitchell,

485 N.W.2d 807 (Wis. 1 9 9 2 ) .................................. 4, 9

- V l l l -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Continued)

Page(s)

United Brotherhood o f Carpenters & Joiners

v. Scott,

463 U.S. 825 (1983)............ ...................................... 9

United States v. Erves,

880 F.2d 376, cert, denied, 493 U.S. 968

(11th Cir. 1989) ........................................................ 14

United States v. Griffin,

585 F. Supp. 1439 (M.D.N.C. 1983)...................... 13

United States v. Guest,

383 U.S. 745 (1966)...................... ............................ 11

United States v. O'Brien,

391 U.S. 367 (1968)................................................... 3, 17

United States v. Wayne,

903 F.2d 1188 (8th Cir. 1990) ............................... 14

Statutes

U.S. Constitution

Amendment I ........................................................... passim

Amendment VIII ..................................................... 14

Amendment XIII . . . . ............................................ 10

Amendment XIV ..................................................... 10, 14

Amendment X V ........................................................ 10

- ix -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Continued)

Page(s)

18 U.S.C.

Appendix 4, § 3A1.2 ............................................... 3, 14

§ 112 ........................... ........... . . . . . . . . . . . ____ 11

§ 241 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ___ . . . . . . . 10, 11

§ 245 ...................................... .................................... 11, 12

42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 .................... .......................... .......................... 6

§ 1985(3) ................................................. .................. 7, 8, 9,

10

§ 2000e-2(a)(l) .......................................................... 5

Ala. Code § 13A-5-40(a)(5) (1992) ................. .. 13

Alaska Stat. § 12.55.125(1) (1992) .............................. 14

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-703(10)

(The Michie Co. 1992) ................................ 14

Ark. Code Ann. § 5-10-101(a)(3) (1992) ................. 14

Cal. Penal Code § 190.2(a)(7)

(Deering's 1992) ..................................... 14

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 18-3-107 (1992)___ . . . . . . . . . 14

Ha. Stat. Ann. § 921.141(5)(k) (1991) . . . . . . . . . . 13

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Continued)

_________________________________________________ Fage(s)

Haw. Rev. Stat. § 706-660.2

(The Michie Co. 1992) ............................................ 14

111. Rev. Stat. Ch. 38 para. 9-l(b)(l)

(Smith-Hurd 1979 & Supp. 1990) ........................ 14

Iowa Code § 707.2 (1991)............................. .. 14

Kan. Stat. Arm. §§ 21-3409 & 21-3411 (1991) ___ 14

Mass. Ann. Laws Ch. 279 § 69(a)(1)

(Lawyers Cooperative Publishing 1 9 9 3 )............. 14

Mich. Comp. Laws § 28.747(1)(3) (1989) .............. 14

N.Y. Penal Law § 125.27(l)(a)

(Lawyers Cooperative 1992) ......................... 14

Nev. Rev. Stat. § 200.033(7)

(The Michie Co. 1991) ............................................ 14

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2929.04(a)(6)

(Baldwin's 1992)........................................................ 14

Or. Rev. Stat. § 163.095(2)(a) (1991) ......................... 14

42 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 9711(d)(1) (1991).......... ........... 14

Term. Code Arm. § 39-13-204(9) (1992) . . . . ___ 14

- X -

- XI -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Continued)

Page(s)

Tex. Penal Code Arm. § 19.03(a)(1) (1 9 9 3 )............ 14

Utah Code Ann. § 76-5-202(k)

(The Michie Co. 1992) ............................................ 14

Va. Code Ann. § 18.2-31(6)

(The Michie Co. 1992) . ...................... .................. 14

Wash. Rev. Code § 10.95.020(1) (1991) .................... 14

Wis. Stat. § 939.645 (1992 Supp.) . . ......................... passim

Other Authorities

B. Levin, Bias Crimes: A Theoretical & Practical

Overview, 4 Stan. L. & Pol'y Rev. 165, 166-168

(forthcoming 1993) ................................................... 18

National Institute Against Prejudice & Violence,

The Ethnoviolence Project, Institute

Report No. 2, 5 (1986) ................. .................. . . . . 21

J. Weinstein, First Amendment Challenges to

Hate Crime Legislation: Where's the Speech?,

11 Criminal Justice Ethics 3, (forthcoming

1992) ...................... ................................... ........... .. . 20

- xii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(Continued)

Page(s)

C. Wexler and G. Marx, When Law And

Order Works, 32 Crime & Delinquency

205 (1986) ..................................................................... 22

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

O c t o b er T e r m , 1992

No. 92-515

S t a t e o f W is c o n s in ,

Petitioner,

v.

T o d d M it c h e l l ,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Wisconsin Supreme Court

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights under Law

("the Lawyers' Committee") submits this brief as amicus curiae

in support of Petitioner, the State of Wisconsin.

The Lawyers' Committee is a nationwide civil rights

organization that was formed in 1963 by leaders of the

American Bar, at the request of President Kennedy, to provide

legal representation to Blacks who were being deprived of their

civil rights. The national office of the Lawyers' Committee and

its local affiliates have represented the interests of Blacks,

Hispanics and women in hundreds of class actions relating to

employment discrimination, voting rights, equalization of

- 2 -

municipal services and school desegregation. Over one

thousand members of the private bar, including former

Attorneys General, former presidents of the American Bar

Association and other leading lawyers, have assisted the

Lawyers' Committee in such efforts.

This case raises issues of great importance to the clients

served by this amicus curiae. The Lawyers' Committee views

section 939.645 as an anti-discrimination statute, which, if

upheld, will help to protect individual rights. Anti-

discrimination criminal laws are a vital link in the chain of

legislative and law enforcement efforts to safeguard the civil

rights of individuals. The Wisconsin legislature, in enacting

section 939.645, has adopted this approach to combat the

increasing incidence of discriminatory criminal behavior. The

legislature did so while taking great care not to infringe upon

guaranteed First Amendment rights. The statute involved in

the present case is substantially similar to several existing civil

rights and criminal statutes which are consistent with the First

Amendment. Section 939.645 should therefore be upheld on

analogous grounds.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Wisconsin Penalty Enhancement Statute which

comes before the Court today, section 939.645(l)(b), Stats. 1989-

90, increases the applicable maximum sentence in cases where

the defendant selected a victim based on the victim's race or

other protected status. No First Amendment rights are

implicated by this statute because it is aimed at discriminatory

conduct, not speech. The operation of the statute is directly

analogous to the operation of civil rights laws which penalize

discrimination in employment, education, and public

accommodations. Furthermore, enhancing a penalty based

- 3 -

upon the defendant's selection of a particular victim is

consistent both with general principles of criminal law and

existing criminal statutes. The Federal Sentencing Guidelines,

for example, provide for an increased penalty for crimes

intentionally directed at a government officer or employee.

18 U.S.C. Appendix 4, § 3A1.2. Section 939.645 should be

upheld on precisely the same grounds as the numerous anti-

discrimination and criminal statutes which define an offense or

punishment in relation to a victim's status. The Court should

reaffirm its long-standing teaching that neither discriminatory

intent nor discriminatory selection raises any First Amendment

issues.

Even if the Court were to conclude that the

discriminatory selection of a victim on the basis of the victim's

protected status involves expression, the Wisconsin statute

should, nonetheless, be upheld. Under United States v. O'Brien,

391 U.S. 367 (1968), the state's interest in regulating expressive

conduct must be balanced against the individual's right to

freedom of expression. Here the state unquestionably has

police power to regulate public safety. The Wisconsin

legislature could reasonably have concluded that status-

dependent crimes, which the statute seeks to regulate, are

especially reprehensible, that they produce a greater and more

disruptive injury, and that they are particularly difficult to

deter; consequently, there can be no question that the

legislature was acting within its purview when it enacted this

statute. Furthermore, the law is narrowly tailored to address

victim selection; any effect that it might have on expressive

conduct is incidental at best. Thus, even under the O'Brien

test, the decision of the Wisconsin Supreme Court should be

reversed and the constitutionality of the statute upheld.

- 4 -

ARGUMENT

I. ENHANCING THE PUNISHMENT FOR A CRIME

COMMITTED BECAUSE OF THE VICTIM'S RACE OR

STATUS DOES NOT HAVE EVEN AN INCIDENTAL

EFFECT ON SPEECH.

Section 939.645(l)(b), Stats. 1989-90, subjects a criminal

defendant to an enhanced penalty if the defendant

"intentionally selects the person against whom the crime is . . .

committed . . . because of the race, religion, color, disability,

sexual orientation, national origin or ancestry of that

person . . . " It is the commission of a crime against a person

selected because of her status that section 939.645 punishes.1

The statute punishes only conduct.

To come within its reach, section 939.645 plainly requires

only (1) that the defendant commit a crime against a victim,

and (2) that the defendant have intentionally selected that

victim because of that victim's protected status. The statute is

not concerned with the actor's speech, or with her views about

the victim or the group to which the victim belongs. Like all

other anti-discrimination laws, it is concerned only with

whether the actor targeted the victim because of the victim's

race or other status.

1 See State v. Mitchell, 485 N.W.2d 807, 820 (Wis. 1992) (Bablitch, ].,

dissenting).

- 5 -

A. Government Regulation of Discriminatory Conduct

Does Not Implicate Freedom of Speech.

Section 939.645 closely parallels civil rights laws which

impose penalties for discrimination in employment, education,

and public accommodations. Civil rights laws penalize

otherwise permissible conduct (e.g., refusing to employ or rent

an apartment to a person) when targeted against individuals

who are selected because of their race or other protected status.

By the same token, section 939.645 entrances the penalty for

engaging in impermissible conduct when targeted against

individuals who are selected because of their race or other

protected status. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, for

example, bars discrimination "with respect to [the]

compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment,

because of [an] individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin." 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)(l) (emphasis added). Similarly,

the Wisconsin statute imposes more severe sentences where a

criminal offender selects his victim "because of" the victim's

race or other protected status.

This Court has rejected the argument that Title VII

impinges on First Amendment guarantees of free speech. In

Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984), the Court held

that a female associate in a law firm could state a claim against

the firm under Title VII by alleging she was denied equal

consideration for partnership, because such consideration was

one of her "terms, conditions, or privileges of employment."

The Court dismissed the law firm's contention that such a

holding would "infringe constitutional rights of expression or

association," because the law firm could not show how its right

to free speech "would be inhibited by a requirement that it

consider petitioner for partnership on her merits." 467 U.S. at

78.

- 6 -

The Court reached a similar conclusion in Runyon v.

McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976). Runyon rejected a First

Amendment challenge to 42 U.S.C. section 1981, which

guarantees, inter alia, that persons of all races in the United

States shall have equal rights to make and enforce contracts.

Runyon held that section 1981 bars a private, non-sectarian

school from selecting students on the basis of race and that, as

so applied, the statute does not impinge upon First

Amendment rights to freedom of association. The Runyon

Court recognized that the First Amendment provides a right

"'to engage in association for the advancement of beliefs and

ideas, . and that a right of association "is protected because

it promotes and may well be essential to the '[effective

advocacy of both public and private points of view,

particularly controversial ones' that the First Amendment is

designed to foster." Id. at 175, quoting N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama,

357 U.S. 449, 460 (1958). While private schools may advocate

a belief in school segregation,

it does not follow that the practice of excluding

racial minorities from such institutions is also

protected by the same principle. As the Court

stated in Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973),

"the Constitution . . . places no value on

discrimination," id., at 469, and while "[ilnvidious

private discrimination may be characterized as a

form of exercising freedom of association

protected by the First Amendment. . . it has

never been accorded affirmative constitutional

protections. . . ." Id., at 470. In any event, as the

Court of Appeals [in Runyon] noted, "there is no

showing that discontinuance o f [the] discriminatory

admission practices would inhibit in any way the

teaching in these schools of any ideas or dogma.”

- 7 -

Runyon at 176 (emphasis added).

Likewise, Respondent cannot show that the additional

penalty imposed on him because of his race-based choice of a

victim in any way inhibits his freedom of speech. Respondent

was at liberty, under section 939.645, to hurl even the most

offensive racial invectives at his victim. Respondent's

enhanced penalty, however, stems from his hurling punches

rather than words. "[VJiolence or other types of potentially

expressive activities that produce special harms distinct from

their communicative impact. . . are entitled to no

constitutional protection." Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468

U.S. 609, 628 (1984), citing Runyon, supra, 427 U.S. at 175-176

(Minnesota statute requiring Jaycees to accept women as full

members did not abridge the male members' freedom of

expressive association).

Respondent essentially claims that the government may

not impose a penalty on him simply because of his

discriminatory intent. This contention is not only at odds with

the cases cited above, but also with the Court's interpretation

of 42 U.S.C. section 1985(3), an interpretation which was

adopted over twenty years ago and reaffirmed earlier this year.

In Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1971), the Court clarified

the scope of section 1985(3), which provides a civil remedy for

conspiracy to deprive any person of the equal protection of the

laws.2 The broad sweep of the initial draft of this

2 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3) provides:

If two or more persons in any State or Territory conspire or go in

disguise on the highway or on the premises of another, for the

purpose of depriving, either directly or indirectly, any person or

class of persons of the equal protection of the laws, or of equal

(continued...)

- 8 -

Reconstruction era statute was narrowed by a subsequent

amendment, which "centered entirely on the animus or

motivation that would be required." Id. at 100. Thus:

The constitutional shoals that would He in the

path of interpreting § 1985(3) as a general federal

tort law can be avoided by giving full effect to

the congressional purpose—by requiring, as an

element of the cause of action, the kind of

invidiously discriminatory motivation stressed by

the sponsors of the limiting amendment. . . . The

language requiring intent to deprive of equal

protection, or equal privileges and immunities,

means that there must be some racial, or perhaps

otherwise class-based, invidiously discriminatory

animus behind the conspirators' action.

Id. at 102 (emphasis in original).

Discriminatory animus, therefore, is both an essential

and a constitutionally permissible element of section 1985(3).

The Court reaffirmed this principle earlier this year when it

held that an action to enjoin protestors from obstructing access

2(...continued)

privileges and immunities under the laws . . . [and] in any case of

conspiracy set forth in this section, if one or more persons engaged

therein do, or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of the object

of such conspiracy, whereby another is injured in his person or

property, or deprived of having and exercising any right or

privilege of a citizen of the United States, the party so injured or

deprived may have an action for the recovery of damages,

occasioned by such injury or deprivation, against any one or more

of the conspirators.

- 9 -

to abortion clinics fell outside the scope of section 1985(3). The

Court found that the alleged conspirators lacked the

discriminatory motivation required by section 1985(3):

"Discriminatory purpose . . . implies more than

intent as volition or intent as awareness of

consequences. It implies that the decisionmaker

. . . selected or reaffirmed a particular course of

action at least in part because of/ not merely 'in

spite of/ its adverse effects upon an identifiable

group."

Bray v. Alexandria Women's Health Clinic, _ _ U.S. ___,

61 U.S.L.W. 4080,4082 (1993) quoting Personnel Administrator of

Massachusetts v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256, 279 (1979). See also United

Brotherhood o f Carpenters & Joiners v. Scott, 463 U.S. 825, 838

(1983) (holding that section 1985(3) does not reach conspiracies

"motivated by commercial or economic animus").3

While the preceding discussion has focused on federal

civil rights legislation, the same principles apply to state fair

employment, fair housing, and similar laws. Many states have

3 The Wisconsin Supreme Court distinguished civil rights laws from

section 939.645 in part on the grounds that section 939.645 provides

for criminal penalties, as opposed to civil sanctions. State v. Mitchell,

485 N.W.2d 807, 817 (Wis. 1992). The Wisconsin Supreme Court cited

no authority for this distinction, and this Court has never endorsed it.

Indeed, because the standard of proof for conviction under criminal

laws is higher than that for judgments under civil laws, and because

the fines available under civil laws may be much greater than under

criminal laws, a civil statute affecting free speech may be "'a form of

regulation that creates hazards to protected freedoms markedly

greater than those that attend reliance upon criminal law.'" New York

Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 277-278 (1964) quoting Bantam Books,

Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 70 (1963).

- 10-

had such laws on the books for several decades, and it would

be surprising, to say the least, if they were to be held invalid

under the First Amendment as applied to the states through

the Fourteenth Amendment.4

B. Weighing a Defendant's Selection of the Victim in

Ascertaining a Criminal Sentence Is Consistent with

Other Criminal Statutes.

Section 939.645 is consistent with criminal statutes as

well. For example, 18 U.S.C. section 241, a criminal

counterpart to 42 U.S.C. section 1985(3), makes it a crime to

conspire to intimidate a person from exercising her

constitutional rights.5 As this Court has held, to fall under

4 Of course, federal anti-discrimination laws enjoy a special status

under the Constitution. See Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 345 (1880)

(holding that the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, "were

intended to be, what they really are, . . . enlargements of the power of

Congress"); South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 326 (1966)

(applying a similar interpretation to legislation enacted under the

Fifteenth Amendment). Hence, even if this Court were to hold that

section 939.645 conflicted with the First Amendment, it would not be a

determination that federal anti-discrimination laws authorized by the

Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments were similarly

unconstitutional.

5 That section provides, in the relevant part:

If two or more persons conspire to injure, oppress,

threaten, or intimidate any citizen in the free exercise or

enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the

Constitution or laws of the United States, or because of his

having so exercised the same;

(continued...)

-11 -

section 241, a defendant "must act with a specific intent to

interfere with the federal rights in question." United States v. Guest,

383 U.S. 745, 753-54 (1966). For example:

[A] conspiracy to rob an interstate traveler would

not, of itself, violate § 241. But if the predominant

purpose of the conspiracy is to impede or prevent

the exercise of the right of interstate travel, or to

oppress a person because of his exercise of that

right, then . . . the conspiracy becomes a proper

object of the federal law under which the

indictment in this case was brought.

Id. at 760 (emphasis added).

While the statute makes it a crime to conspire

specifically to intimidate a victim from exercising her rights, it

does not follow that any particular message is being

proscribed. See CISPES (Committee in Solidarity with the People

of El Salvador) v. Federal Bureau o f Investigation, 770 F.2d 468,474

(5th Cir. 1985) (holding that 18 U.S.C. § 112(b)(l-2), which, like

section 241, proscribes intimidating persons in certain status-

based categories, does not condemn a particular message, but

prohibits threatening or intimidating conduct); see also Boos v.

Barry, 485 U.S. 312, 323-26 (1988) (stating that 18 U.S.C. § 112

is content neutral and narrowly tailored to meet the

government's "vital interest in complying with international

law").

5(...continued)

They shall be fined not more than $10,000 or imprisoned

not more than ten years, or both.

- 12-

Title 18 U.S.C. section 245 is yet another example of a

criminal statute which proscribes the deliberate targeting of

protected groups as one of its elements.6 Among its other

6 That statute states, in part:

Whoever, whether or not acting under color of law, by

force or threat of force willfully injures, intimidates or

interferes with, or attempts to injure, intimidate or

interfere with—

* * * *

(2) any person because of his race, color, religion or

national origin and because he is or has been—

(A) enrolling in or attending any public school

or public college;

(B) participating in or enjoying any benefit,

service . . . or activity provided or administered

by any State or subdivision thereof;

(C) applying for or enjoying employment, or any

perquisite thereof, by any private employer or any

agency of any State or subdivision thereof . . .;

(D) serving or attending upon any court of any

State in connection with possible service, as

a grand or petit juror,

(E) traveling in or using any facility of interstate

commerce, or using any vehicle, terminal or facility of

any common carrier by motor, rail, water or air;

(F) enjoying the goods, services, facilities, privileges,

advantages, or accommodations of any inn, hotel. . . .

* * *

shall be fined not more than $1,000 or imprisoned not

more than one year or both . . . .

18 U.S.C.A. § 245(2).

- 13-

provisiorts, it seeks to protect a potential victim who is selected

for intimidation, threats, injury, or interference because of her

race, color, religion or national origin and because she is

engaging in any of various enumerated acts (such as attending

a public school, engaging in interstate commerce, or staying at

a hotel). At least one lower court decision, United States v.

Griffin, 585 F. Supp. 1439 (M.D.N.C. 1983), has specifically

focused on the scienter requirement of this statute. Far from

holding that the specific intent required by the statute violates

the constitution, the court concluded that the required specific

intent to interfere with federal rights7 saves the statute from

a constitutional attack based on vagueness. Id. at 1444.

Moreover, imposing a different punishment on the

defendant in this case because he deliberately selected a victim

of a particular race is entirely consistent with basic American

criminal law principles. Courts routinely consider the intended

choice of or effect on a victim both in categorizing particular

crimes and in determining appropriate sentences.

Section 939.645 applies where the victim is selected

because she is a member of a class specified by the statute.

Other criminal statutes similarly enhance the penalty of a

criminal offender based on the victim's membership in a

specified class.8 State capital crime statutes typically list

7 Specifying that a defendant must have the specific intent to

interfere with federal rights provided Congress with the authority to

enact this legislation. Of course, states acting pursuant to their police

powers have much broader authority to regulate criminal conduct.

8 It is commonplace for criminal statutes to take into account a

victim's status when defining or punishing a crime. See e.g., Ala.

Code § 13A-5-40(a)(5) (1992); Ha. Stat. Ann. § 921.141(5)(k) (1991);

(continued...)

- 14 -

selection of a police officer as a victim as an aggravating factor

which may justify the imposition of the death penalty/ and the

Court has endorsed this criterion. See e.g., Jurek v. Texas, 428

U.S. 262, 276 (1976) (upholding Texas' capital sentencing

procedures under Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments).

Similarly, the Federal Sentencing Guidelines provide for an

enhanced penalty for offenses committed against a government

officer or employee when the offense "was motivated by such

status." 18 U.S.C. Appendix 4, § 3A1.2 (emphasis added).9

8(...continued)

Mass. Ann. Laws Ch. 279 § 69(a)(1) (Lawyers Cooperative Publishing

1993); Or. Rev. Stat. § 163.095(2)(a) (1991); 42 Pa. Cons. Stat.

§ 9711(d)(1) (1991). Moreover, many such laws which include victim

status as an element also include criminal intent to select a victim

based on her status as a necessary element. See e.g., Alaska Stat.

§ 12.55.125(1) (1992); Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-703(10) (The Michie Co.

1992); Ark. Code Ann. § 5-10-101 (a)(3) (1992); Cal. Penal Code

§ 190.2(a)(7) (Deering's 1992); Colo. Rev. Stat. § 18-3-107 (1992); Haw.

Rev. Stat. § 706-660.2 (The Michie Co. 1992); 111. Rev. Stat. Ch. 38

para. 9-l(b)(l) (Smith-Hurd 1979 & Supp. 1990); Iowa Code § 707.2

(1991); Kan. Stat. Ann. §§ 21-3409 & 21-3411 (1991); Mich. Comp. Laws

§ 28.747(1)(3) (1989); Nev. Rev. Stat. § 200.033(7) (The Michie Co.

1991); N.Y. Penal Law § 125.27(l)(a) (Lawyers Cooperative 1992); Ohio

Rev. Code Ann. § 2929.04(a)(6) (Baldwin's 1992); Term. Code Ann.

§ 39-13-204(9) (1992); Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.03(a)(1) (1993); Utah

Code Ann. § 76-5-202(k) (The Michie Co. 1992); Va. Code Ann. § 18.2-

31(6) (The Michie Co. 1992); Wash. Rev. Code § 10.95.020(1) (1991).

9 The Federal Sentencing Guidelines have withstood numerous

attacks on their constitutionality. In Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S,

361, (1989), this Court affirmed that the guidelines neither violate the

separation of powers doctrine nor constitute an excessive delegation of

legislative power. Other courts have likewise upheld the Guidelines

against various constitutionally based attacks. See e.g., United States v.

Ewes, 880 F.2d 376, cert, denied, 493 U.S. 968 (11th Cir. 1989) (proce

dural and substantive due process); United States v. Wayne, 903 F.2d

1188 (8th Cir. 1990) (constitutionally mandated standard of proof). To

(continued...)

- 15 -

Respondent contends that a statute which penalizes the

selection of a victim based on that victim's membership in a

particular class must violate the First Amendment. Under this

view, the choice of a victim because she is a police officer, for

example, would also constitute expression protected by the

First Amendment. Unless Respondent can provide a

principled distinction between these statutes and

section 939.645, every state or federal statute which provides

stiffer penalties for crimes committed with the intent to injure

individuals who are members of particular classes must violate

the right to free expression. Respondent, however, cannot

provide any support for this position.

In summary, the language of section 939.645 is clearly

directed at discriminatory conduct. To run afoul of the statute,

one need only be guilty of discriminatory conduct—the statute

is not concerned with the motivations or beliefs which led to

the discriminatory choice of victim. For example, a rapist who

victimizes southeast Asian women might do so because he

believes that they are less likely to report his crimes to the

police. Or, a mugger who only attacks Jews might do so

because he thinks that they have more money than others.

These criminals, if convicted of their crimes, can have their

penalties enhanced under section 939.645. Both criminals

"intentionally select" their victims "because of" their protected

status—the first to avoid detection and the second to increase

his plunder. On the other hand, a bigot who shouts a string

of racial epithets at an African-American is outside of the

9(...continued)

our knowledge, no case has challenged the constitutionality of the

Federal Sentencing Guidelines on First Amendment grounds.

- 1 6 -

statute's reach; her expression is completely unaffected by the

Wisconsin statute.10

The First Amendment prevents the government from

driving "'certain ideas or viewpoints from the marketplace.'"

R.A.V. v. City o f St. Paul, Minnesota, supra, at 2545 n.9 (citations

omitted). Section 939.645 does not drive any ideas from the

marketplace nor does it strive to; it only seeks to drive status-

based crimes from Wisconsin's streets. The marketplace of

ideas still remains open to KECK meetings and Nazi rallies.

II. EVEN IF THE COURT WERE TO DETERMINE THAT

SECTION 939.645 INCIDENTALLY AFFECTS EXPRES

SION, IT DOES NOT VIOLATE THE FIRST AMEND

MENT.

Even if this Court were to determine that respondent's

violent assault on Matthew Riddick contained a sufficient

communicative element to bring it within the scope of the First

10 In R.A.V. v. City o f St. Paul, Minnesota,__U .S.__ , 112 S. Ct. 2538

(1992), this Court found a St. Paul ordinance which prohibited

"fighting words" that contain "messages of 'bias-motivated' hatred"

facially unconstitutional because it prohibited otherwise permissible

speech solely on the basis of the subjects that the speech addressed.

Id. at 2548. R.A.V. is distinguishable from the instant case on at least

two grounds.

First, the Wisconsin statute is aimed at discriminatory conduct,

not expression. The St. Paul ordinance directly targeted "fighting

words", which, although outside the normal ambit of First

Amendment protection, still constitute a form of expression. See id. at

2543-44. Second, unlike the St. Paul ordinance, the Wisconsin statute

evinces no hostility or favoritism to any particular viewpoint. Rather,

the statute targets discriminatory conduct, without regard to the

viewpoint that inspired it.

- 17-

Amendment, section 939.645 is unrelated to the suppression of

expression and readily meets the test enunciated in United

States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968).

A. Statutes That Regulate Conduct Rather Than Speech

Are Analyzed Under a Four-Prong Test.

Under well-settled law, the government has a freer hand

in restricting conduct combining "speech" and "nonspeech"

elements than it has in restricting pure speech. O'Brien,

391 U.S. at 376. Where speech and conduct are combined in

one course of action, the state's interests in regulating the

conduct in question must be balanced against First

Amendment rights. In such cases, the statute does not violate

the First Amendment if: (1) the regulation falls within the

constitutional power of the government; (2) the regulation

furthers "an important or substantial governmental interest;" (3)

the regulation is "unrelated to the suppression of free

expression;" and (4) "the incidental restriction on alleged First

Amendment freedoms is no greater than is essential to the

furtherance of that interest.” Id. at 376-377.

B. Section 939.645 Fully Meets the Four-Prong Test.

Because section 939.645 is narrowly tailored to serve

several legitimate and compelling governmental interests

which are not aimed at suppressing speech, it does not violate

the First Amendment.

- 18 -

1. The State of Wisconsin Clearly Has the Power to

Enact Laws Criminalizing Discrimination.

The power of the State of Wisconsin to punish criminal

conduct is well established. The legislature clearly has the

power to enact laws that are necessary to promote the public

health, safety and morals. See Jacobson v. Massachusetts,

197 U.S. 11, 25 (1905). Here, in view of the increasing

incidence of reported crimes where victims are targeted based

on their status11 and the particular danger of widespread civil

unrest resulting from such acts, the Wisconsin state legislature

was well within its power to enact section 939.645.

2. Section 939.645 Furthers Several Important Govern

mental Interests.

The governmental interests served by section 939.645 are

compelling. The State of Wisconsin has a substantial interest

in penalizing crimes targeted at members of certain groups

more than other crimes because, as elaborated below, the

legislature could find that they are more reprehensible and

socially disruptive, that they have the effect of terrorizing a

community, and that they are harder to deter.

11 B. Levin, Bias Crimes: A Theoretical & Practical Overview, 4 Stan.

L. & PoTy Rev. 165, 166-168 (forthcoming 1993).

- 19 -

a. Section 939.645 Legitimately Protects the

Community's Sense That Status-Dependent

Crimes Are Inherently More Reprehensible

Because of Their Motivation.

The Wisconsin legislature could reasonably have

concluded that status-dependent crimes are inherently more

reprehensible due to the status-dependent motivation. That

the State of Wisconsin has a legitimate interest in enforcing the

community's sense of morality is indisputable. This Court has

repeatedly upheld the state's power to do so. For example,

just two years ago, this Court upheld a public indecency

statute under the O'Brien test because it furthered "a

substantial government interest in protecting order and

morality." Barnes v. Glen Theatre, In c .,__U.S. ___, 111 S. Ct.

2456, 2462 (1991). See also Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton, 413

U.S. 49 (1973).

Moreover, considering the relative evil of an act in

determining the degree of punishment has long been viewed

as an appropriate method of determining punishment. In

Barclay v. Florida, 463 U.S. 939, 949 (1983), for example, the

Court held that the defendant's desire to start a race war when

he indiscriminately murdered a white hitchhiker was relevant

to showing aggravating circumstances. As recently as last

year, in Dawson v. Delaware, _ U .S .__, 112 S. Ct. 1093, 1097

(1992), the Court reaffirmed its holding in Barclay that in

capital sentencing the judge may consider "evidence of [the

defendant's] racial intolerance and subversive advocacy where

such evidence was related to the issues involved." In other

words, where a criminal act has been committed, an inquiry

into the malevolence of defendant's motivations, including

discriminatory animus, is appropriate so that a fitting sentence

can be set.

- 2 0 -

In the instant case, of course, a criminal assault was

committed. Absent that assault, defendant's apparent belief

that whites are appropriate targets for racial violence would be

completely protected. Given that assault, however, a trial

court would be fully justified in taking into account that the

victim was selected because of his race. A legislature can

certainly do the same in enacting penalty enhancement

provisions.

b. Status-Dependent Violence Has an In Terrorem

Effect on Members of the Victim's Community

and Is More Socially Disruptive.

The extra punishment given to perpetrators of status-

dependent crimes is justified by the extra harm that status-

dependent crimes cause. Status-dependent violence transforms

the injury into a different type of harm which is more

damaging to the victim than the same violent act lacking

status-dependent motivation. In addition to the injury inflicted

on the victim, these crimes have an in terrorem effect on

members of the victim's community. As one commentator

observed, "The effect of Kristallnacht on German Jews was

greater than the sum of the damage of buildings and assaults

on individual victims." J. Weinstein, First Amendment

Challenges to Hate Crime Legislation: Where's the Speech?,

11 Criminal Justice Ethics 3 (forthcoming 1992).

Not only are status-based offenses more damaging than

the same offense lacking such motivation because they

terrorize the victim and the community, they are also more

damaging because they are more socially disruptive. Take, for

example, the disturbance caused by the racially charged

Rodney King beating. Alternatively, consider the disruption

that occurred when a Korean grocer shot and killed a black girl

- 21 -

in Los Angeles. As one court observed: "Such confrontations

. . . readily—and commonly do—escalate from individual

conflicts to mass disturbances. That is a far more serious

potential consequence than that associated with the usual run

of assault cases." State v. Beebe, 680 P.2d 11,13 (Or. App. 1984).

Calculating the magnitude of a criminal penalty based

on the terroristic or disruptive effect the crime has on the

victim or community is in accordance with well-established

principles. In Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584, 598 (1977), for

example, this Court explained that rape is a crime deserving

serious punishment because, among other harmful

consequences, rape can "inflict mental and psychological

damage" on the victim and, in addition, "undermine[] the

community's sense of security." Similarly, in R.A.V. v. City of

St. Paul, Justice Stevens noted that "[threatening someone

because of her race or religious beliefs may cause particularly

severe trauma . . . ; such threats may be punished more

severely than threats against someone based on, say, his

support of a particular athletic team." 112 S. Ct. at 2561

(Stevens, J. concurring).

c. Crimes Motivated by the Status of the Victim

May Be More Difficult to Deter Than Other

Crimes.

The Wisconsin statute enhances penalties because status-

based crimes need to be deterred even more than non-status-

based crimes. The State of Wisconsin could reasonably

conclude that conventional criminal statues are not effective in

deterring status-dependent crimes. Victims of status-

dependent crimes are often exposed to a series of attacks and

their assaulters are more likely to repeat their attacks than non

status-based assaulters. National Institute Against Prejudice &

- 22 -

Violence, The Ethnoviolence Project, Institute Report No. 1, 5

(1986); C. Wexler and G. Marx, When Law And Order Works, 32

Crime & Delinquency 205 (1986). Deterrence is clearly a

legitimate justification for determining the degree of

punishment. See Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817, 822 (1974).

Racial, ethnic and religious-based criminal acts have

divided our society throughout history. Such conduct is not

merely a relic of the past. In addition to the recent ethnic and

racial disruption in our own nation, every day the newspapers

report ethnic violence throughout the world—Protestants and

Catholics in Northern Ireland; Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians in

former Yugoslavia; Kurds and Sunni Muslims in Northern

Iraq. Surely, it is within the power of the states to deter such

divisive violence in our own nation.

3. Section 939.645 Is Unrelated to the Suppression of

Speech.

As the above justifications for the statute illustrate, the

State of Wisconsin's interest in punishing crimes motivated by

the victim's status are unrelated to the suppression of speech.

Quite to the contrary, the state's aim in enacting section

939.645 is solely to combat the devastating effects of violent

status-dependent crimes. Protecting society from crimes

targeted at individuals because of their membership in

identifiable groups is a separate and distinct goal, unrelated to

free speech rights.

- 23 -

4. The Incidental Restriction on Speech, if Any,

Caused by the Wisconsin Statute Is No Greater

Than Necessary to Further the Governmental

Interests Served by Section 939.645.

The Wisconsin legislature has narrowly tailored

section 939.645 so that the statute only addresses criminal acts

directed at individuals because of their race or other status.

The statute does not, for example, create a new crime for those

who engage in bigoted speech but do not commit crimes. An

individual remains free to express his or her discriminatory

views by any means other than committing already proscribed

crimes. Further, the statute imposes no penalties on bigots

who commit crimes which are not in themselves

discriminatory. The statute only provides extra penalties for

those who commit crimes against the property or persons of

protected groups because the victims belong to those groups.

In doing so, the statute merely codifies the type of judicial

consideration long given to status-dependent conduct, which

this court has already deemed constitutionally permissible.

CONCLUSION

While this Court "should be eternally vigilant against

attempts to check the expression of opinions we loathe,”

Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 630 (1919) (Holmes, J.,

dissenting), the Wisconsin statute at issue here poses no such

risk. It is an exaggeration to say that imposing an additional

penalty for the senseless beating of a fourteen year old boy,

because the victim was selected on the basis of his race, even

- 2 4 -

incidentally affects the "free trade in ideas." Id. For these

reasons, section 939.645 does not abridge freedom of speech in

violation of the First Amendment.

Dated: January 28, 1993.

Respectfully submitted,

Paul Brest*

814 Tolman Drive

Stanford, California 94305

(415) 723-4455

Alan Cope Johnston

Yonkel Goldstein

Kenneth A. Kuwayti

Douglas W. Phillips

Anna Erickson White

Marc J. Pemick

M orrison & F oerster

755 Page Mill Road

Palo Alto, California 94304-1018

(415) 813-5600

Herbert M. Wachtell

Co-Chair

William H. Brown, III

Co-Chair

Norman Redlich

Trustee

Barbara R. Arnwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Sharon R. Vinick

L aw yers ' C ommittee F or

C ivil R igh ts U nder L aw

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Denotes Counsel o f Record