Court Tells Union it Cannot Discriminate Because of Race

Press Release

November 19, 1974

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Court Tells Union it Cannot Discriminate Because of Race, 1974. d8c4effb-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db6d4b9e-c5ca-4941-b47d-47c15d4e7091/court-tells-union-it-cannot-discriminate-because-of-race. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

4

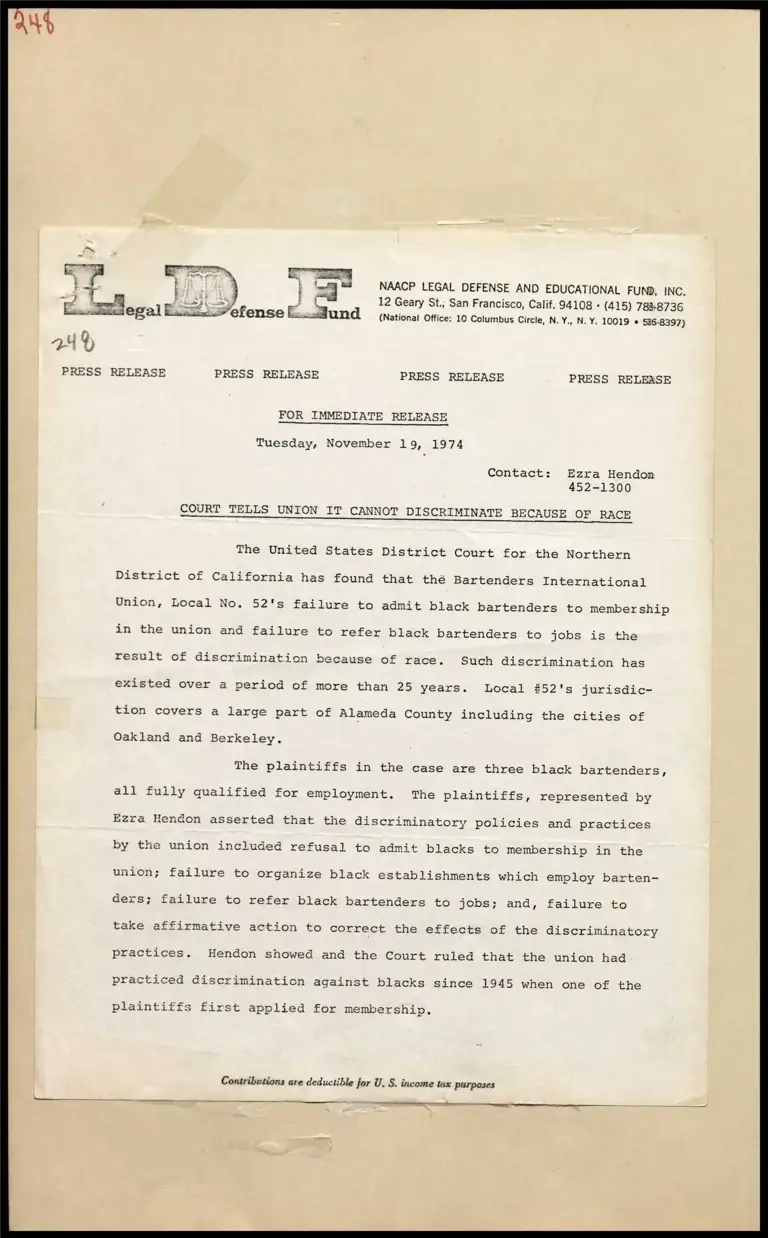

} B } =f od NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. ue F LS} BS a & 12 Geary St.; San Francisco, Calif. 94108 - (415) 783-8736 egal E.acisefense ..3und (National Office: 10 Columbus Circle, N. Y., N.Y. 10019 « §36-8397)

PRESS RELEASE PRESS RELEASE PRESS RELEASE PRESS RELEASE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ee LEAS

Tuesday, November 19, 1974

Contact: Ezra Hendon

452-1300

COURT TELLS UNION IT CANNOT DISCRIMINATE BECAUSE OF RACE

The United States District Court for the Northern

District of California has found that thé Bartenders International

Union, Local No. 52's failure to admit black bartenders to membership

in the union and failure to refer black bartenders to jobs is the

result of discrimination because of race. Such discrimination has

existed over a period of more than 25 years. Local #52's jurisdic-

tion covers a large part of Alameda County including the cities of

Oakland and Berkeley.

The plaintiffs in the case are three black bartenders,

all fully qualified for employment. The plaintiffs, represented by

Ezra Hendon asserted that the discriminatory policies and practices

by the union included refusal to adr t blacks to membership in the

union; failure to organize black establishments which employ barten-

ders; failure to refer black bartenders to jobs; and, failure to

take affirmative action to correct the effects of the discriminatory

practices. Hendon showed and the Court ruled that the union had

practiced discrimination against blacks since 1945 when one of the

plaintiffs first applied for membership.

Contributions are deductible for U. S. income tax purposes

The Court found that the union had violated the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 and the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Further, the

Court found that the plaintiffs are entitled to affirmative relief

requiring the union to refer the plaintiffs to the next available

full-time jobs as bartenders and that the plaintiffs are entitled to

an award of back pay for the losses they have suffered as a result

of the union's unlawful employment practices. Awards will be made

totalling $28,344.70 to the three plaintiffs.

The case filed in May of last year was supported by

the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.*

ate

* Please bear in mind that even though we were originally established

by the NAACP and those initials are retained in our name, the LDF is

a completely separate and distinct organization with no present

connection whatever with the NAACP. Our correct designation is the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., frequently shortened

to LDF. We provide legal representation in significant civil rights

suits across the country. The San Francisco office was opened in

1968.

EIGHTH FLOOR, 12 GEARY STREET, SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94108

TELEPHONE (415) 788-8736