Defendants' and Defendant-Intervenors' First Request for Production of Documents with Certificate of Service

Public Court Documents

September 3, 1999

8 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Defendants' and Defendant-Intervenors' First Request for Production of Documents with Certificate of Service, 1999. 79c30de6-e00e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db6ff90f-011f-4bd8-aff0-68d4ebb6bc77/defendants-and-defendant-intervenors-first-request-for-production-of-documents-with-certificate-of-service. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

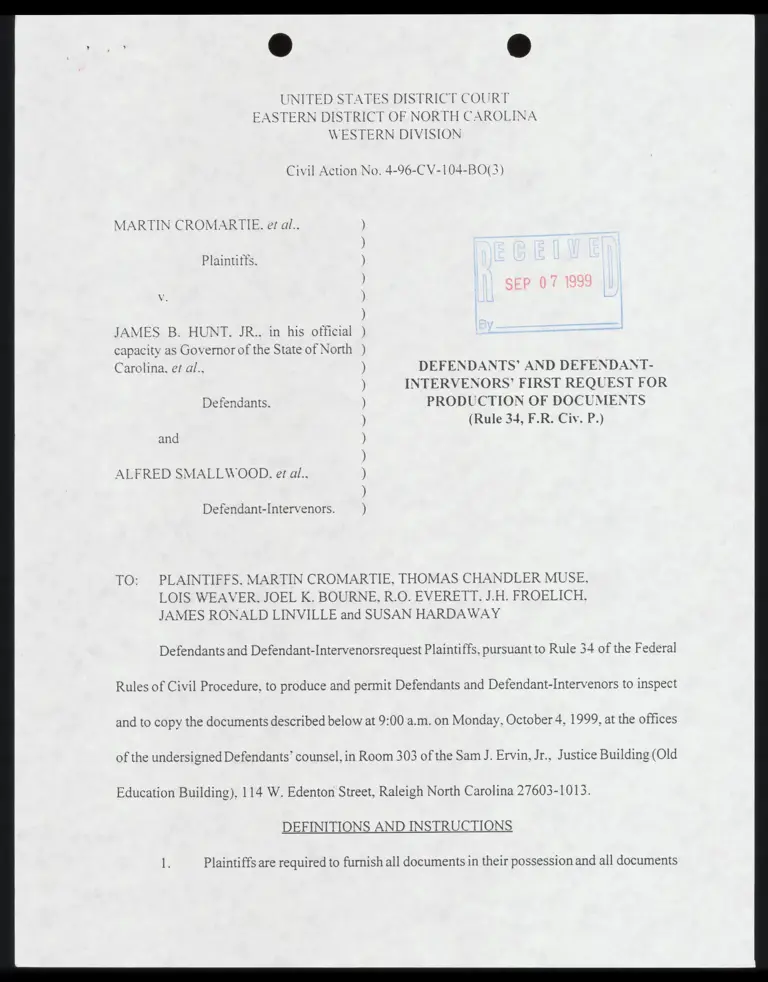

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

WESTERN DIVISION

Civil Action No. 4-96-CV-104-BO(3)

MARTIN CROMARTIE. et al..

Plaintiffs.

Y.

JAMES B. HUNT. JR.. in his official |

capacity as Governor of the State of North

Carolina. et al., DEFENDANTS’ AND DEFENDANT-

INTERVENORS’ FIRST REQUEST FOR

Defendants. PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS

(Rule 34, F.R. Civ. P.)

and

ALFRED SMALLWOOD. et al..

Defendant-Intervenors.

PLAINTIFFS. MARTIN CROMARTIE, THOMAS CHANDLER MUSE.

LOIS WEAVER. JOEL K. BOURNE, R.O. EVERETT. J.H. FROELICH,

JAMES RONALD LINVILLE and SUSAN HARDAWAY

Defendants and Defendant-Intervenorsrequest Plaintiffs, pursuant to Rule 34 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, to produce and permit Defendants and Defendant-Intervenors to inspect

and to copy the documents described below at 9:00 a.m. on Monday, October 4, 1999, at the offices

of the undersigned Defendants’ counsel, in Room 303 of the Sam J. Ervin, Jr., Justice Building (Old

Education Building), 114 W. Edenton Street, Raleigh North Carolina 27603-1013.

DEFINITIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS

Plaintiffs are required to furnish all documents in their possession and all documents

available to them. This includes all documents available to each of them. their attorney. their

employees. and or officers and agents. by reason of inquiry including inquiry 0 f their representatives.

"Document" refers to all items subject to discovery under Rule 34 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure. including. but not limited to. any written or recorded material of any kind.

including the originals and all non-identical copies. whether different from the originals by reason

of any notation made on such copies or otherwise; notations of any sort of conversations. telephone

calls. meetings (minutes. agendas or records of meetings) or other communications of any nature:

studies; letters. notes and correspondence: memoranda reports. tests and/or analyses: calendars and

telephone records: publications. reports and/or summaries of interviews and reports and/or

summaries of investigation: opinions or records of consultants. circulars and trade letters: drafts of

anv document. and revisions of drafts of any documents: charts and all graphic or oral records or

representations of any kind: mechanical or electronic records representations of any kind including

tapes. cassettes. disks or records; and computer files (including e-mail records). tapes, cassettes.

disks or records.

REQUEST FOR PRODUCTION

Produce copies of all prepared testimony. photo-offset conference proceedings.

affidavits and reports prepared by your experts in connection with other voting rights proceedings.

Produce copies of deposition or trial testimony by your experts given In connection

with other voting rights proceedings.

~

Produce each document identified or relied on in response to Defendants’ And

Defendant-Intervenors First Set of [nterrogatories (including all maps). As to any map required to

be produced. please produce all supporting data and documentation or related writings. including

electronic communications.

4. Produce any and all alternative congressional districting maps of which you are

aware and which you believe would have met constitutional and Voting Rights Acts requirements

if they had been adopted by the General Assembly in 1997. Please produce such maps, including

all supporting data and documentation or related writings, regardless of whether they were in

existence in 1997 or whether the General Assembly had them before it.

>. Produce any and all alternative maps of one or more congressional districts. but

fewer than all districts. of which you are aware and which vou believe would have met constitutional

and Voting Rights Acts requirements if they had been adopted by the General Assembly in 1997.

Please produce such maps regardless of whether they were in existence in 1997 or whether the

General Assembly had them before it.

6. Produce any writings or electronic communications that reflect the terms, conduct.

and results of any contests involving the drawing of maps for one or more congressional districts.

5

7. Produce copies of any and all congressionaldistricting maps. includingall supporting

data and documentationor related writings. whether for one or more districts or all twelve. that were

created. produced. or provided in connection with any contests involving the drawing of maps tor

one or more congressional districts.

8. Produce any maps. including all supporting data and documentation or related

writings. that were created or provided to plaintiffs and their counsel by any civic organizations,

such as the League of Women Voters.

This the 3d day of September. 1999.

MICHAEL F. EASLEY

ATTORNEY GENERAL

£ Fr Ta,

/

!

{

/

/

Edwin M. Speas. Jr. /

Chief Deputy Attorney General /

N.C. State Bar No. 4112

Tiare B. Smiley

Special Deputy Attorney General

N. C. State Bar No. 7119

Norma S. Harrell

Special Deputy Attorney General

N. C. State Bar No. 6634

N.C. Department of Justice

P.O. Box 629

Raleigh. N.C. 27602

(919) 716-6900

ATTORNEYS FOR DEFENDANTS

or Olle Tho 2 —

Adam Stein

Ferguson, Stein, Wallas, Adkins,

Gresham & Sumter, P.A.

312 W. Franklin Street, Suite 2

Chapel Hill, NC 27516

Todd Cox

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

1444 1 Street NW

Washington, DC 20005

ATTORNEYSFORDEFENDANT-INTERVENORS

’ ? »

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that [ have this day served a copy of the foregoing DEFENDANTS’ FIRST

REQUEST FOR PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS in the above captioned case upon all

plaintiffs by hand delivery to the following address:

Robinson O. Everett

Suite 300 First Union Natl. Bank Bldg.

301 W. Main Street

P.O. Box 586

Durham. NC 27702

ATTORNEY FOR PLAINTIFFS

This the 3d day of September. 1999.

ALA

iare B. Smiley

Special Deputy Attorney General /

PRODOC1.WPD