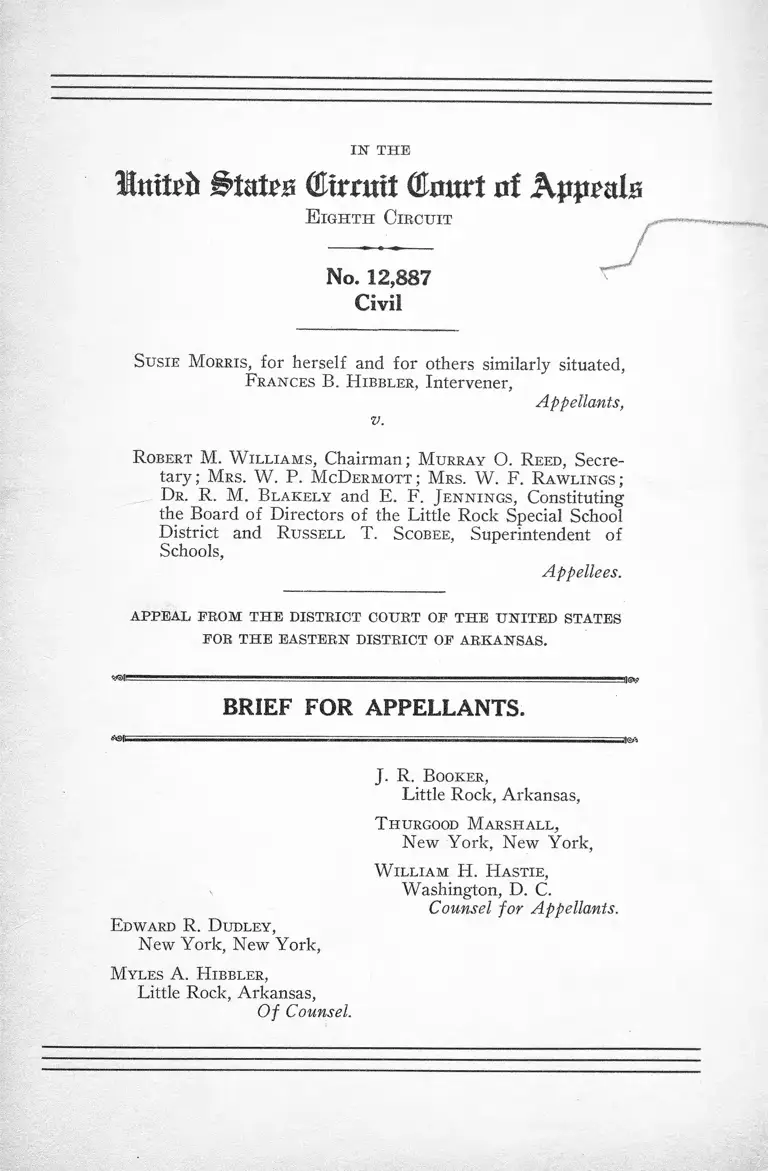

Morris v. Williams Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1945

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morris v. Williams Brief for Appellants, 1945. 0aeca6c6-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db8bfaa9-4e92-4ad4-b388-8817d260809a/morris-v-williams-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

IN' T H E

llmtih (Bxvmit (tort nf Appals

E i g h t h C i r c u i t

No. 12,887

Civil

Susie M orris, for herself and for others similarly situated,

Frances B. K ibbler, Intervener,

Appellants,

v.

R obert M. W illiams, Chairman; M urray O. R eed, Secre

tary ; Mrs. W . P. M cD ermott ; M rs. W . F. R awlings ;

Dr. R. M. Blakely and E. F. Jennings, Constituting

the Board o f Directors o f the Little Rock Special School

District and R ussell T. Scobee, Superintendent of

Schools,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE DISTRICT COURT OP THE UNITED STATES

POR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS.

Edward R. Dudley,

New York, New York,

J. R. Booker,

Little Rock, Arkansas,

T hurgood M arshall,

New York, New York,

W illiam H. H astie,

Washington, D. C.

Counsel for Appellants.

M yles A. K ibbler,

Little Rock, Arkansas,

O f Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

S tatem ent of th e C a s e _______ __________________________

S tatem ent of F a c t s ______________________________________

Method of Fixing Salaries_____________________

New Teachers_____________________________

Old Teachers _____________________________

Policy of Board in the Past____________________

Bonus Payment _______________________________

S tatem ent of P oints T o B e R elied U pon_______________

S tatem ent of P oints T o B e A rgued and A uthorities

R elied U p o n ___________________________________________

A rgument ____________________________________

Introduction ________ 1_________________________

I. The Fourteenth Amendment Protects the In

dividual Against All Arbitrary and Unrea

sonable Classifications by State Agencies____

II. Payment of Less Salary to Negro Public

School Teachers Because of Race Is in Vio

lation of Fourteenth Amendment__________

III. The Policy, Custom and Usage of Fixing Sal

aries of Public School Teachers in Little Rock

Violates the Fourteenth Amendment________

IV. The So-Called Rating System in Little Rock

Is Not an Adequate Defense to This Action.__

Conclusion ________________________________________________

Appendix A ______________________________________

Appendix B ________ __________________________

Appendix C ______________________________

1

oa

4

4

7

8

10

11

14

18

18

20

27

32

45

56

57

64

74

11

CITATIONS.

Cases:

PAGE

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F. (2d)

992 (1940); certiorari denied, 311 U. S. 693 (1940)„16,17

20,28

Buchannan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917)___________ 14, 21

Chaires v. City of Atlanta, 164 Ga. 755, 139 S. E. 559

(1927) ___1______________________________________ 14,21

Chamberlain v. Kane, 264 S. W. 24 (1924)_________ _17, 48

Davenport v. Cloverport, 72 Fed. 689 (D. C. Ky.

1896)______________________________________—..15, 21

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 (1880)______________ 18

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915)__...______ 15, 24

Hale v. Kentucky, 303 U. S. 616 (1938)_______________ 25

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 401, 404 (1942)_____15,16,17,26, 32

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939)__________ 14,15, 21, 24

McDaniel v. Board, 39 F. Supp. 638 (1941)___________ 20

Mills v. Board of Education, et al., 30 F. Supp. 245

(1940) ___________________________________ 16,17,28,29

Mills v. Lowndes, et al., 26 F. Supp. 792 (1939)__16,17, 20

28, 29

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337

(1938) ______________________________________ 15,19, 21

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941)________ 14, 21

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 (1915)______________ 15

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1880)________ 15,16,25, 32

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 (1932)__________________ 14, 20

Norris v. Alabama, 294 IT. S. 591 (1935)_____________ 15, 25

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 (1939)______14,15, 20, 35

Boles v. School Board of City of Newport News, Civil

Action No. 6 (1943), U. S. District Court for East

ern District of Virginia, unreported_____________ 16, 30

PAGE

iii

Simpson v. Geary, et al., 204 Fed. 507, 512 (D. C. Ariz.

1913) ___________________________________________ 21

Smith v. Texas, 311 TJ. S. 128, 85 L. Ed. 84-87 (1940)__15,26

State v. Bolen, 142 Wash. 653, 254 P. 445 (1927)_____18, 48

Steel v. Johnson, 9 Wash. (2d) 347, 358, 115 P. (2d) 145

(1941) --------------------j.____________________________17,48

Strauder v.. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1879)—.14,15, 20

21, 24

Thomas v. Hibbitts, et al., 46 F. Snpp. 368 (1942)—16, 20, 28

29, 36

Truax v. Raich, 239 TJ. S. 33 (1915)__________________15, 21

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356_______________ 15,27, 38

Miscellaneous.

Flack, Adoption of 14th Amendment (1908), pp. 219,

223, 227 ________________________ ________________15,22

20 American Jurisprudence, Sec. 1027, p. 866_________ 18

14 Stat. 27, April 9, 1866________ _____________________ 22

16 Stat. 140, May 31, 1870____________________________ 22

Reports and Hearings______________ _________________ 19

■

. .

IN THE

Ittttefc BtnttB (Eirnttt GJmtrt nf Appeals

E ig h th C ircuit

No. 12,887

Civil

S usie M orris, for herself and for others similarly

situated, F rances B. H ibbler, Intervener,

Appellants,

v.

R obert M. W illiam s , Chairman; M urray 0. R eed,

Secretary; M rs. W. P. M cD e r m o tt ; M rs. W. F.

R aw lin g s ; D r . R. M. B lakely and E. F. J en

nings, Constituting the Board of Directors of the

Little Rock Special School District and R ussell

T. S cobee, Superintendent of Schools,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS.

P A R T I.

Statement of the Case.

This is an appeal from a final judgment of the District

Court of the United States, the Western Division of the

Eastern District of Arkansas. The appellant, Susie Morris,

on behalf of herself and all others similarly situated, filed

an original complaint seeking a declaratory judgment, and

a permanent injunction against the appellees, being the

Superintendent of Public Schools, and the members of the

School Board of Little Rock, Arkansas. The complaint

2

alleged that the appellees were maintaining a policy, cus

tom and usage of paying Negro teachers and principals in

the public schools of Little Rock, Arkansas, less salary than

that paid to white teachers and principals in the public

schools of Little Rock because of their race or color (R. 1-9).

The appellees in their answer denied most of the essential

allegations of the complaint (R. 9-13). A comparison of the

allegations of the complaint and the answer is set out in

Appendix A to this brief. After a full trial on the merits,

United States District Judge T homas C. T rimble entered

a final judgment on March 10, 1944, that the complaint of

the appellant be dismissed on the merits (R. 817-823).

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law were filed (R.

817-823). The opinion of the District Judge appears in the

record at pages 800-817. Notice of appeal was promptly

filed on March 11,1944 (R. 823).

On April 29, 1944, appellant Frances P. Hibbler, filed

her motion and affidavit for leave to intervene (R. 826-829).

Counsel for both original appellant and appellees consented

to the entering of an order permitting intervention, which

order was signed by the District Judge May 4, 1944 (R.

828-829).

Statement of Facts.

As a result of the peculiar circumstances surrounding

this type of case the majority of the testimony in the record

is from the appellees who were first called by appellant as

adverse witnesses. The documentary material available

showed evidence of disparity in expenditures for public

education, including teachers’ salaries, on the basis of race.

The appellees denied that there was any discrimination be

cause of race or color. The Superintendent considers only

white teachers for positions in white schools and Negro

teachers for positions in Negro schools and in making his

3

recommendations to the Personnel Committee, designates

the teachers by schools so that the members of the Personnel

Committee in considering the appointment and fixing of

salaries of teachers are aware of the race of the teachers

being considered (R. 192). In general the report from the

Personnel Committee to the Board designates Negro teach

ers by the word “ Negro” and no designation beside the

names of white teachers (R. 118). It is likewise admitted

that the members of the Personnel Committee in consider

ing teachers are aware of the race of the teachers being

considered (R. 119). The salaries for public school teachers

for the years 1941-1942 were not fixed on the basis of teach

ing ability or merit (R. 192).

Appellants have prepared comparative tables of salaries

paid white and Negro teachers based upon undisputed testi

mony and these comparative tables are set forth in Appen

dix B to this brief. These tables show a great disparity

between the salaries of white and Negro teachers of equiva

lent qualifications and experience.

Superintendent Scobee, first employed by the School

Board of Little Rock in 1941, testified that since he had been

Superintendent there had been no change in salaries with

the exception of a few adjustments and that they had re

mained much the same as when he became Superintendent

(R. 183). He also testified that if the salaries prior to his

administration had a differential based solely on the

grounds of race and color, the same difference would exist

at the present time (R. 183).

Superintendent Scobee testified further that he could not

deny that the salaries fixed before his term of office were

based on race or color (R. 192).

In the school district of which Little Rock is a part the

per capita expenditure per white child was $53 and per col

4

ored child was $37 for 1939-40. During the same period

the revenue available was $47 per child. In Arkansas dur

ing that period the average salary for elementary teachers

was: white $526 and Negro $331; and for high school teach

ers was $856 for white and $567 for Negro (R. 18-19).

All of the public schools in Little Rock, both white and

Negro, are part of one system of schools and the same type

of education is given in both the Negro and white schools

(R. 182). The same textbooks and same courses of study

are used in all schools (R. 191). All public schools are open

the same number of days per year and the same number of

hours per day (R. 183).

Method of Fixing Salaries.

The salaries of teachers are recommended by the super

intendent to the Personnel Committee of the board after

which a report is made by the Personnel Committee to the

board for adoption (R. 21). Neither the board nor the Per

sonnel Committee interviews the teachers (R. 31, 102). In

the fixing of salaries from year to year the board does not

check behind the recommendations of the superintendent

(R. 56).

New Teachers.

Although all of the appellees denied that there was a

salary “ schedule” as such, the appellant produced a salary

schedule for Negro teachers providing a minimum salary

of $615 (R. 716). Superintendent Scobee denied ever hav

ing seen such a schedule but admitted that since 1938 “ prac

tically all” new Negro teachers had been hired at $615. All

new white teachers during that period have been hired at

not less than $810 (R. 316). For years it has been the policy

of the Personnel Committee to recommend for Negro teach

5

ers lower salaries than for white teachers new to the sys

tem (R. 36). This has been true for many years (R. 36).

Other appellees admitted that all new Negro teachers were

paid either $615 or $630 and all new white teachers were

paid a minimum of $810 (R. 84, 87-88, 99, 189).

In 1937 the School Board adopted a resolution whereby

a “ schedule” of salaries was established providing that

new elementary teachers, were to be paid a minimum of

$810, junior high $910 and senior high $945 (R. 285, 286, 576-

579). Although Superintendent Scobee denied that the

word “ schedule” actually meant schedule he admitted that

since that time all white teachers had been employed at

salaries of not less than $810 (R. 286-287).

The difference in salaries paid new white and Negro

teachers is supposed to be based upon certain intangible

facts which the superintendent gathers by telephone conver

sations and letters in addition to the information in the

application blanks filed by the applicants (R. 317-318). For

example, two teachers were being considered for positions,

one white and one Negro. The superintendent, following

his custom, telephoned the professor of the white applicant

and received a very high recommendation for her. He did

not either telephone or write the professors of the Negro

applicant. As a result he paid the white teacher $810 as an

elementary school teacher, and the Negro teachers $630 as

a high school teacher despite the fact that their professional

qualifications were equal (R. 316-317). Superintendent Sco

bee also admitted that where teachers have similar qualifi

cations, if he would solicit recommendations for one and

receive good recommendations and fail to do so for the

other, the applicant whose recommendations he solicited

and obtained would appear to him to be the better teacher

(R. 317). He seldom sought additional information about

6

the Negro applicants (R. 327, 346), although personal inter

views were used in the fixing of salaries and played a large

part in determining what salary was to be paid (R. 323,

326).

Superintendent Scobee testified that the employment

and fixing of salaries of new teachers always amounted to

a “ gamble” (R. 322). He admitted that he had made sev

eral mistakes as to white teachers and that although he was

paying one white teacher $900 she was so inefficient he was

forced to discharge her (R. 486). During the time he has

been superintendent Mr. Scobee has never been willing to

“ gamble” more than $630 on any Negro teacher and during

the same period has never “ gambled” less than $810 on a

new white teacher (R. 324). Some new white teachers are

paid more than Negro teachers with superior qualifications

and longer experience (R. 338).

One of the reasons given for the differential in salaries

is that Negro teachers as a whole are less qualified (R. 39)

and that the majority of the white teachers “ have better

background and more cultural background” (R. 39).

Since it is the general understanding that the board can

get Negro teachers for less it has been the policy of the

board to offer them less than white teachers of almost iden

tical background, qualificaitons and experience (R. 120).

Further explanations of why Negroes are paid less is that:

“ They are willing to accept it, and we are limited by our

financial structure, the taxation is limited, and we have to

do the best we can” (R. 121); and, that Negroes can live

on less money than white teachers (R. 121). The president

of the board testified that they paid Negroes less because

they could get them for less (R. 23-24).

One member of the school board, in response to a ques

tion: “ If you had the money would you pay the Negro

7

teachers the same salary as you pay the white teachers?”

testified that: “ I don’t know, we have never had the

money” (R. 59).

Old Teachers.

Comparative tables showing the salaries of white and

Negro teachers according to qualifications, experience and

school taught have been prepared from the exhibits filed in

the case and are attached hereto as Appendix B, According

to these tables no Negro teacher is being paid a salary equal

to a white teacher with equal qualifications and experience.

This fact is admitted by Superintendent Scobee (R. 497).

It is the policy of the appellees to pay high school

teachers more salary than elementary teachers (R. 183). It

is also the policy of the appellees to pay teachers with expe

rience more than new teachers. It is admitted that the

Negro teachers at Dunbar High School are good teachers

(R. 191). However, the appellant and twenty-four other

Negro high school teachers with years of experience are

now being paid less than any white teacher in the system

including newly appointed and inexperienced elementary

teachers new to the system (R. 187). Superintendent Sco

bee was unable to explain the reason for this or to deny

that the reason might have been race or color of the teachers

(R. 189, 192). He testified that he could not fix the salaries

of Negro high school teachers on any basis of merit because

“ my funds are limited” (R. 192).

In past years Negro teachers have been employed at

smaller salaries than white teachers and under a system

of blanket increases over a period of years Negroes have

received smaller increases (R. 87-88). The differential over

a period of years has increased rather than decreased (R.

88). One member of the board testified that “ I think there

are some Negro teachers as good as some of the white

8

teachers, but I think there are some not as good” (R. 88).

Another board member testified that he thought there were

some Negro teachers getting the same salary as white

teachers with equal qualifications and experience (R. 104).

Policy of Board in Past.

Several portions of the minutes of the school board

starting with 1926 were placed in evidence (R. 511-641).

In 1926 several new teachers were appointed. The white

teachers were appointed at salaries of from $90 to $150 a

month. Negro teachers were appointed at from $63 to $80

a month (R. 511-512). Later the same year the superin

tendent of schools recommended that “ B. A. teachers with

out experience get $100.00, $110.00, $115.00, according to

the assignment to Elementary, Junior High, or Senior High

respectively” . Additional white teachers were appointed

at salaries of from $100 to $200 a month and at the same

time Negroes were appointed at salaries of from $65 to $90

(R. 514-515), in 1927 all white teachers with the exception

of six were given a flat increase of $75 per year and all

Negro teachers were given a flat increase of $50 per month

(R. 517).

On May 14, 1928, the school board adopted a resolution:

“ all salaries for teachers remain as of 1927-1928, and in

event of the 18 mill tax carrying May 19, 1928, the white

school teachers are to receive an. increase of $100 for 1928-

29 and the colored teachers an increase of $50 for 1928-

1929” (R. 519). During the same year three white prin

cipals were given increases of from $25 a month to $100 a

year while one Negro principal was given an increase of $5

a month (R. 520).

On May 21, 1929, the board adopted a resolution that:

“ an advance of $100.00 per year be granted all white teach

9

ers, and $50.00 per year for all colored teachers, subject to

the conditions of the Teachers’ salary” (R. 525). Prior to

that time Negro teachers were getting less than white teach

ers (R. 57). According to this resolution all white teachers

regardless of their qualifications received increases of $100

each while all Negro teachers were limited to increases of

$50 each (R. 57). It was impossible for a Negro teacher

to get more than a $50 increase regardless of qualifications

(R. 57). One reason given for paying all white teachers a

$100 increase and all Negro teachers $50 was that at the

time the Negro teachers were only getting about half as

much salary as the white teachers (R. 58).

On April 30, 1932, all teachers’ salaries were cut 10%

(R. 543). On June 19,1934, a schedule of salaries for school

clerks was established providing $50 to $60 a month for

white clerks and $40 to $50 a month for colored clerks (R.

560). It was also decided that: “ white teachers entering

Little Rock Schools for 1933-34 for the first time at a mini

mum salary of $688.00, having no cut to be restored, be

given an increase of $30 for the year 1934-35 (R. 560). On

June 28,1935, at the time the appellant was employed white

elementary teachers new to the system were appointed at

$688 to $765 for elementary teachers and $768 for high

school teachers while plaintiff and other Negro teachers

were employed at $540 (R. 564-565).

On March 30, 1936, the school board adopted the follow

ing recommendations: “ That the contracts for 1936-37 of

all white teachers who are now making $832 or less be in

creased $67.50, and all teachers above $832.50 be increased

to $900, and that no adjustment exceed $900.” ; and “ that

the contracts for 1936-37 of all colored teachers who now

receive $655 or less be increased $45, and all above $655 be

increased to $700, and that no adjustment exceed $700” .

10

It was also provided “ that the salaries of all white teachers

who have entered the employ of the Little Rock School

Board since above salary cuts, or whose salaries were so

low as not to receive any cut, be adjusted $45.00 for 1935-

36” ; and “ that the salaries of all colored teachers who have

entered the employ of the Little Rock School Board since

the above salary cuts, or whose salaries were so low as not

to receive any cut, be adjusted $30.00 for 1935-36” (R. 567-

568).

On April 25, 1936, it was decided by the school board:

“ The contracts are to be the same as for 1935-36, except

that those white teachers receiving less than $900.00, and

all colored teachers receiving less than $700, who are to get

$67.50 and $45 additional respectively, or fraction thereof,

not to exceed $900 and $700, respectively” .

Bonus Payments.

In 1941 the school board made a distribution of certain

public funds as a supplemental payment to all teachers

which was termed by them a “ bonus” . This money was

distributed pursuant to a plan adopted by the school board

(R. 713-715, see Exhibits 3-A and 3-B). The plan was

worked out and recommended by a committee of teachers in

the public schools (R. 88-89). This committee was composed

solely of white teachers (R. 194) because, as one member

of the board testified: “ We don’t mix committees in this

city” (R. 89). Superintendent Scobee testified that he did

not even consider the question of putting some Negro teach

ers on the committee (R. 197-198).

Under this plan there were three criteria used in deter

mining how many “ units” a teacher was entitled to: one,

years of experience, two, training, and three salary (see

Exhibits 3-A and 3-B). After the number of units was de

11

termined the fund was distributed as follows: each white

teacher was paid $3.00 per unit and each Negro teacher was

paid $1.50 per unit. After the number of units were de

termined the sole determining factor as to whether the

teachers received $3.00 or $1.50 per unit was the race of

the teacher in question (R. 314).

After the 1941 distribution the Negro teachers went to

Superintendent Scobee and protested against the inequality,

yet, another supplemental payment was made in 1942 and

the same plan was used (R. 197).

In 1937 the Negro teachers filed a petition with the

appellees seeking to have the inequalities in salaries because

of race removed. No action was taken other than to refer

it to the superintendent (R. 573). In 1938: “ Petition signed

by the Colored Teachers of the Little Rock Public Schools

requesting salary adjustments, was referred to Committee

on Teachers and Schools” (R. 579). On May 27, 1939, a

report was adopted by the school board which included the

following: “ Petition of colored teachers for increase in

pay. Disallowed” (R. 585).

Statement of Points To Be Relied Upon.

I.

The District Court erred in that its findings of fact num

bered 11, 15, 15-a and 17 (R. 819-820), state, contrary to

the evidence, that there are not in force in the Public Schools

of Little Rock Special School District schedules of salaries

discriminatory against Negro teachers as a class (R. 23, 36,

59, 84, 87-88, 100, 121, 122, 183, 189, 282, 285, 286, 314, 316,

329, 347-349, 489, 511-641, 716).

12

II.

The District Court erred in that its findings of fact, num

bered 14, 15, 15-a, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20 (R. 820-821) state,

contrary to the evidence, that teachers ’ salaries in the Pub

lic School District are fixed and determined by the merits

of the individual teacher without discrimination because of

race or color, and that no policy, practice, custom or usage

of such discrimination exists or has existed in the fixing of

salaries (R. 23-24, 34, 36, 40, 59, 84-88, 120-122, 183, 187,

189, 192, 282, 314, 316-320, 329, 347-349, 489, 497). '

III.

The District Court erred in making Conclusion of Law

No. 3 which is in actuality a finding of fact concerning the

absence of salary schedules, objectionable for the reasons

set out in paragraph I of these points (R. 511-641, and cita

tions under I, supra).

IV.

The District Court erred in making Conclusion of Law

No. 4 which is in actuality a finding of fact concerning the

absence of usage, policy, or custom on the part of the

appellees, objectionable for the reasons set out in paragraph

II of these points (R. 23, 34, 36, 57, 58, 59, 121,122, 183, 511-

512, 514-515, 517, 519, 520, 525, 564-565, 567-568, 585, 713-715,

and citations under II, supra).

V.

The District Court erred in making Conclusion of Law

No. 4 in holding that rating sheets were admissible in evi

dence as part of the records of the School District (R. 41,

281, 282, 391, 408, 426, 430, 440, 441, 447, 473-474, 492).

The evidence admitted appears as: Appellees ’ Exhibits

Nos. 3 and 5 (R. 183, 192, 768, 779).

13

Objection raised by appellant to Appellees’ Exhibit No.

3 was stated as follows: “ . . . Our objection to this rating

sheet is, in the first place, according to the testimony of Mr.

Scobee it has never been presented to the Board. It is,

therefore, not an official document of the School Board in

the Little Bock School District. The second ground, we

place it on, is that this is a self-serving declaration whether

it be written or not is no objection. This is a self-serving

declaration. It is admitted it was not for the purpose of

fixing salaries, it is merely for the self-serving purpose of

setting out their own ideas to the effect that the rating and

the salaries have some connection . . . ”

The Court: “ It is understood these other people will

testify this is the conclusion and there was a conclusion

which can be brought in to substantiate his testimony. I

will admit it for that purpose with the understanding that

these other parties who aided him in coming to the conclu

sion he has reached in making this schodule will be intro

duced” (R. 236).

Objection raised to Appellees’ Exhibit No. 5: “ I f your

Honor please, at this stage I object to them being admitted

on the basis of Mr. Nash’s testimony. . . . Let’s find out

from Mr. Scobee, and we object at this stage to it being

introduced on the ground that there has been no proper

foundation laid by the witness . . . but here we have some

prepared by Mr. Scobee and some prepared by Mr. Hamil

ton and now Mr. Scobee produces them and I certainly insist

they are not admissible until Mr. Scobee has been intro

duced.”

The Court: “ I will permit these for the time being”

(B. 270).

14

VI.

The District Court erred in making Conclusion of Law

No. 7 in that the necessary inference of racial discrimina

tion which follows from the large actual differences between

the salaries of all Negro teachers and any comparable white

teachers was not overcome by any proof that such differ

ences reflect the superior merits of white teachers (R. 18-19,

23-24, 36, 84, 87-88, 99, 120-121, 189, 316-317, 323, 326,

347, 497.

VII.

The District Court erred in entering judgment of dis

missal of the complaint.

Statement of Points To Be Argued and

Authorities Relied Upon.

I . T he F ourteenth A m endm en t P rotects th e I ndi

vidual A gainst A ll A rbitrary and U nreasonable Classifi

cations by S tate A gencies.

Exclusion from petit jury—Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U. S. 303 (1879).

Exclusion from grand jury—Pierre v. Louisiana, 306

U. S. 354 (1939).

Exclusion from voting at party primary—Nixon v. Con

don, 286 U. S. 73 (1932).

Discrimination in registration privileges—Lane v. Wil

son, 307 U. S. 268 (1939).

Ordinance restricting ownership and occupancy of prop

erty Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917).

Ordinance restricting pursuit of vocation—Chaires v.

City of Atlanta, 164 Ga. 755, 139 S. E. 559 (1927).

Refusal of Pullman accommodations—Mitchell v. United

States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941).

15

Discrimination in distribution of public school fund—

Davenport v. Cloverport, 72 Fed. 689 (D. C. Ky.

1896).

Discrimination in public school facilities—Missouri ex

rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938).

Simpson v. Geary, et al. (D. C. Ariz. 1913), 204 Fed. 507,

512.

A . I n I nstances W here R acial D iscrimination I s N ot

A pparent F ederal C ourts H ave E stablished M easures op

P roof S ufficient to E stablish R acial D iscrim ination .

Strauder v. West Virginia, supra.

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 (1915).

May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140; April 9, 1866, 14 Stat. 27.

See also Flack, The Adoption of the 14th Amendment

(1908) pp. 219, 223, 227.

1. Measure of Proof Under Discriminatory Statutes

Not Mentioning Race.

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915).

See also Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 (1915).

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 275 (1939).

2. Measure of Proof Where Discrimination Is Denied

By State Administrative Officers.

Strauder v. West Virginia, supra.

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1880).

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 591 (1935); Hale v. Ken

tucky, 303 U. S. 616 (1938).

Pierre v. Louisiana, supra.

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 85 L. Ed. 84-87 (1940).

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 401 (1942).

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 401, 404.

Yiok Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356.

16

II . P aym en t of L ess S alary to N egro P ublic S chool

T eachers B ecause of R ace I s I n V iolation of F ourteenth

A m en d m en t .

A. I n General .

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F. (2d)

992 (1940); certiorari denied, 311 U. S. 693.

See also Mills v. Lowndes, et al., 26 F. Snpp. 792 (1939).

Mills v. Board of Education, et al., 30 F. Supp. 245

(1940).

Thomas v. Hibbitts, et al., 46 F. Supp. 368 (1942).

B . M in im u m S alary S chedules.

Mills v. Lowndes, et al., supra.

Mills v. Board of Education, supra.

C. E conomic T heory .

Thomas v. Hibbitts, et al., supra.

D . V ariable Salary S chedules.

Roles v. School Board of the City of Newport News,

Civil Action No. 6 (1943), U. S. District Court for

the Eastern District of Virginia, unreported.

Mills v. Board of Education, et al., supra.

Mills v. Lowndes, et al., supra.

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, supra.

Thomas v. Hibbitts, et al., supra.

Neal v. Delaware, supra.

Hill v. Texas, supra.

17

III. T he P olicy, C ustom and U sage of F ixing Salaries

of P ublic S chool T eachers in L ittle E ock V iolates the

F ourteenth A m endm en t .

Mills v. Board of Education, et al., supra.

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, supra.

A . General P olicy of A ppellees.

1. Cultural Background.

2. Economic Theory.

Thomas v. Hibbitts, et al., supra.

B. M in im u m Salaries for N ew T eachers.

1. Little Eock Salary Schedule.

Mills v. Lowndes, et al., supra.

Mills v. Board of Education, et al., supra.

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, supra.

Hill v. Texas, supra.

C. S alaries of Older T eachers and F lat I ncreases.

1. Blanket Increases on Basis of Eace.

D . T he D iscriminatory P olicy of D istributing S upple

m entary S alary P aym ents on an U nequal B asis B ecause,

of E ace.

IV. T he S o-called E ating S ystem in L ittle E ock I s

N ot A dequate D efense to T his A ction .

A . T he C omposite E ating S heets Offered in E vidence

by A ppellees S hould N ot H ave B een A dmitted in E vi

dence.

Steel v. Johnson, 9 Wash. (2d) 347, 115 P. (2d) 145, 150

(1941).

See also Chamberlain v. Kane, 264 S. W. 24 (1924).

18

State v. Bolen, 142 Wash. 653, 254 P. 445.

20 American Jurisprudence, sec. 1027, p. 866.

B. T h e C omposite R ating S heets A re E ntitled to N o

W eight in D eterm ining W h eth er th e P olicy, C ustom and

U sage oe F ixin g S alaries in L ittle R ock I s B ased on R ace.

1. Elementary Schools.

2. High Schools.

3. Ratings by Mr. Hamilton.

ARGUMENT.

Introduction.

The Fourteenth Amendment, passed in 1868, has not as

yet achieved the purpose for which it was enacted: “ To

raise the colored race from that condition of inferiority and

servitude in which most of them had previously stood, into

perfect equality of civil rights with all other persons within

the jurisdiction of the states . . . to take away all possi

bility of oppression by law because of race or color.” *

Despite the requirement of equal treatment wherever

separate schools are maintained, it is clear that there is a

gross disparity in the distribution of public funds for the

maintenance of white and Negro schools:

“ Financial support of Negro schools must he in

creased.—In addition to the general need for partial

equalization of school opportunities among the States

there has long been a need for more funds for Negro

schools. This need has recently been brought into

sharp focus by the rulings of Federal courts that

under the Constitution no discrimination on the basis

* E x parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 (1880).

19

of race or color may be made in the payment of

teachers’ salaries.

The Supreme Court has said that laws providing

separate schools for Negroes meet the requirements

of the Constitution if equal privileges are provided

for children of the separate races. In practice, how

ever, equal facilities have been furnished only rarely.

The States maintaining separate schools for Negroes

are for the most part States with the least economic

ability to raise funds for 'public education. The

schools for white pupils have been financed with great

difficulty and the schools for Negroes have been given

even less support than those for the white pupils. In

the Negro schools the buildings have been poor,

school terms have been shorter, teachers’ salaries

lower, and teacher loads heavier than in schools for

white pupils. The white teachers and educational

leaders have deplored this situation but have lacked

the funds to correct it without levelling down the

none-too-generous program of public education for

white pupils.” *

The United States Supreme Court has reaffirmed the

principle that wherever separate schools are maintained

they must be maintained on an equal basis without discrim

ination because of race.f There no longer is any question

that segregated school systems must offer equal treatment

in all of the facilities of education. Because of the intimate

relations of the teachers to the educational process, the pay

ment of unequal salaries to Negro teachers because of race

* Report: Senate Committee Education and Labor on S. 1313

(Federal Assistance to the States for the Support of Public Educa

tion) 77th Congress, Second Session (June 16, 1942). See also:

Hearings Before Sub-Committee on Education and Labor, United

States Senate, 78th Congress, First Session, on S. 637 (April 6, 7,

and 8, 1943), pp. 98-102 on question of inequalities in educational

facilities in the State of Arkansas, including the figures on average

salaries of white and Negro public school teachers.

f Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 (1938).

20

imposes upon Negro pupils a major educational disadvan

tage even as it imposes unfair and unlawful discrimination

upon the teachers. The right of a Negro teacher to main

tain this type of action has never been disputed.*

I.

The Fourteenth Amendment Protects the Indi

vidual Against All Arbitrary and Unreasonable

Classifications by State Agencies.

While a state is permitted to make reasonable classifi

cations without violating the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, such classifications must be based

upon some real and substantial distinction, bearing a rea

sonable and just relation to the things in respect to which

such classification is imposed. Classification cannot be arbi

trarily made without any substantial basis. Eace can never

be used as a basis for classification.

This protection of the Fourteenth Amendment has been

applied to protect injured persons in numerous types of

cases in which the courts concluded that unreasonable clas

sification and resultant discrimination were arbitrary and

unlawful. /

Exclusion from petit jury—Strauder v. West Vir

ginia, 100 TJ. S. 303 (1879);

Exclusion from grand jury—Pierre v. Louisiana,

306 U. S. 354 (1939);

Exclusion from voting at party primary—Nixon

v. Condon, 286 IT. S. 73 (1932);

* Alston v. School Board, 112 F. (2d) 992 1940), certiorari

denied, 311 U. S. 693; Mills v. Lowndes et al., 26 F. Supp. 792

(1939) _; Mills v. Board of Education, 30 F. Supp. 245 (1939);

McDaniel v. Board, 39 F. Supp. 638 (1941 ); Thomas v. Hibhitts

et al., 46 F. Supp, 368 (1942).

21

Discrimination in registration privileges—Lane

v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 (1939);

Ordinance restricting ownership and occupancy

of property—Buchannan v. Warley, 245 U. S.

60 (1917);

Ordinance restricting pursuit of vocation—•

Chaires v. City of Atlanta, 164 Ga. 755, 139

S. E. 559 (1927);

Refusal of Pullman accommodations—Mitchell v.

United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941);

Discrimination in distribution of public school

fund—Davenport v. Cloverport, 72 Fed. 689

(D. C. Ky. 1896) ;

Discrimination in public school facilities—Mis

souri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337

(1938).

This doctrine has been invoked to prohibit unlawful dis

crimination in employment. An Arizona statute which pro

vided that all employers of more than five employees must

employ not less than eighty percent qualified electors or

native-born citizens of the United States was held unconsti

tutional in a suit by an alien.1

‘ ‘ The right to contract for and retain employment

in a given occupation or calling is not a right secured

by the Constitution of the United States, nor by any

Constitution. It is primarily a natural right, and it

is only when a state law regulating such employment

discriminates arbitrarily against the equal right of

some class of citizens of the United States, or some

class of persons within its judisdiction, as, for ex

ample, on account of race or color, that the civil rights

of such persons are invaded, and the protection of the

federal Constitution can be invoked to protect the

individual in his employment or calling. ’ ’

Simpson v. Geary, et at. (D. C. Ariz. 1913), 204

Fed. 507, 512.

1 Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 (1915).

22

It is clear from the cases set out above that:

(1) State agencies such as appellees, cannot base dis

criminations in the treatment of persons on classifications

which are arbitrary and unreasonable and,

(2) Discrimination based on race or color is the clearest

example of such unlawful classification.

A.

In Instances Where Racial Discrimination Is Not

Apparent Federal Courts Have Established

Measures of Proof Sufficient to Establish Racial

Discrimination.

The Fourteenth Amendment was purposely enacted in

general language, as were the provisions of the Civil Rights

A ct2 passed to enforce the Amendment:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment makes no attempt

to enumerate the rights it is designed to protect. It

speaks in general terms, and those are as comprehen

sive as possible. Its language is prohibitory; but

every prohibition implies the existence of rights and

immunities, prominent among which is an immunity

from inequality of legal protection, either of life, lib

erty, or property. Any State action that denies this

immunity to a colored man is in conflict with the Con

stitution. ’ ’

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1879).

Few states have continued statutes on their books which

mention race or color. However, some states have at

tempted to evade the purpose of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments by (1) enacting statutes which

2 May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140; April 9, 1866, 14 Stat. 27. See also

Flack, The Adoption of the 14th Amendment, pp. 219, 223, 227

(1908).

23

discriminate against Negroes without mentioning race; or

(2) passing statutes without mentioning race, yet broad

enough to permit state officers to discriminate. The United

States Supreme Court has met the problem of discrimina

tory statutes by looking behind the statutes to discover the

discrimination involved. Where state officers have admitted

discrimination under broad statutes their action has been

declared to be unlawful. On the other hand, where state

officers have denied that they have been guilty of discrimina

tion the complaining parties have, because of the very

nature of the facts to be proved, been faced with the almost

impossible task of proving deliberate discrimination. In

the latter type of case the Supreme Court has established

yardsticks of proof to establish discrimination.

(1)

Measure of Proof Under Discriminatory

Statutes Not Mentioning Race.

The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments were con

sidered to strike from state constitutions and statutes the

word “ white” as a qualification for voting. Several states,

however, adopted qualifications for voting which did not

mention race, but which provided that all persons qualified

to vote must be able to read and write. These statutes also

provided that no person who was eligible to vote in 1866 or

any time prior thereto and no lineal descendant of such

person should be required to read and write. When such a

statute from Oklahoma was presented to the United States

Supreme Court it was declared to be unconstitutional and

the Court in its opinion stated:

“ It is true it contains no express words of an

exclusion from the standard which it establishes of

any person on account of race, color or previous con

dition of servitude prohibited by the Fifteenth

24

Amendment, but the standard itself inherently brings

that result into existence since it is based purely upon

a period of time before the enactment of the Fifteenth

Amendment, and makes that period the controlling

and dominant test of the right of suffrage.” 8

In 1916, a year after the decision last mentioned, the

State of Oklahoma enacted another statute providing

that all persons who voted in the general election of

1914 automatically remained qualified voters, but that new

registrants must register between April 30 and May 11,

1916. The United States Supreme Court looked behind this

obvious effort to-circumvent its prior ruling and declared

the latter statute unconstitutional because the Fifteenth

Amendment “ nullifies sophisticated as well as simple-

minded modes of discrimination. It hits onerous pro

cedural requirements which effectively handicap exercise of

the franchise by the colored race although the abstract right

to vote may remain unrestricted as to race.” 3 4 5

(2)

Measure of Proof Where Discrimination Is

Denied by State Administrative Officers.

Wheie a state statute excludes Negroes from jury ser

vice the decision as to its constitutionality raises no par

ticular difficulties.3 However, few such statutes have been

enacted since the Fourteenth Amendment. 'Most of the

cases of discrimination have concerned the action of judicial

or administrative officials in charge of the selection of

jurors.

3 Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915)

v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 (1915).

4 Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 275 (1939).

5Strauder v, West Virginia, supra.

See also Myers

25

The difficulty of proving discrimination because of race

is apparent. In the first place, there is a presumption of

the legality of both grand and petit juries. There also

exists the rule that if exclusion results, not because of race

or color, but because of lack of other qualifications pre

scribed by statute, there is no violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. How, then, is it possible to establish discrimi

nation of race! If the defendant can get the officials who

selected jurors to admit that they refused to summon mem

bers of his race because of their race, he clearly presents

sufficient proof. But it is almost impossible to get a state

official to admit that he has violated the Constitution of the

United States. In Neal v. Delaware,6 the United States

Supreme Court recognized the rule that in a place where

Negroes constitute a large proportion of the population,

exclusion from jury service because of race is presumed

from the fact that no Negroes have been called for jury ser

vice over a long period of years. This rule has been uni

formly followed by the United States Supreme Court.7

In a more recent case, Pierre v. Louisiana,s the lower

Court, while dismissing the petit jury on the grounds of

exclusion of Negroes, refused to quash the indictment on the

grounds of exclusion of Negroes from the grand jury. The

Supreme Court of Louisiana held that the evidence failed

to establish that members of the Negro race were excluded

from the grand jury or petit jury because of race, but

that their exclusion was the result of a bona fide compliance

with state laws. The United States Supreme Court, how

ever, in reversing the decision, found that Negroes had been

excluded from jury service by showing that there had been

only one Negro called for jury service within the memory

6 103 U. S. 370 (1880).

7 See Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 591 (1935); Hale v. Ken

tucky, 303 U. S. 616 (1938).

*306 U. S. 354 (1939).

26

of the Clerk of Court; that according to the 1930 census

Negroes constituted 49.3 per cent of the population and 70

per cent of the Negro population was literate, and that there

was no evidence that any appreciable number of Negroes in

the Parish were guilty of a felony. The opinion of the

Supreme Court therefore concluded: “ that the exclusion of

Negroes from jury service was not due to their failure to

possess the statutory qualifications” .

In one of the latest cases involving the exclusion of

Negroes from jury service it appeared that in Harris

County, Texas, only 5 of 384 grand jurors summoned during

a seven year period were Negroes and only 18 of 512 petit

jurors were Negroes. In reversing the conviction of a

Negro under such a system, Mr. Associate Justice B lack

stated:

“ Here, the Texas statutory scheme is not itself

unfair; it is capable of being carried out with no

racial discrimination whatsoever. But by reason of

'the wide discretion permissible in the various .steps

of the plan, it is equally capable of being applied in

such a manner as practically to proscribe any group

thought by the law’s administrators to be undesirable

and from the record before us the conclusion is in

escapable that it is the latter application that has

prevailed in Harris County. Chance and accident

alone could hardly have brought about the listing for

grand jury service of so few Negroes from among

the thousands shown by the undisputed evidence to

possess the legal qualification for jury service . . , ” 8a

In the case of Hill v. Texas,* 9 the Jury Commissioners

testified that they did not intentionally exclude Negroes

from grand jury service; that they only considered excep-

8a Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 85L. Ed. 84-87 (1940).

9 316 tJ. S. 401 (1942),

27

tional people for jury service and that they did not know

of any Negroes who met that qualification. They testified

further that they made no effort to ascertain whether there

were Negroes qualified for grand jury service in the county.

The Supreme Court held this to be discriminatory because

“ discrimination can arise from the action of commissioners

who exclude all Negroes whom they do not know to be

qualified and who neither know nor seek to learn whether

there are in fact any qualified to serve. ’ ’ 10

Thus wherever state officers, dealing with a large body

of persons including substantial numbers of Negroes, have

placed all or substantially all of the Negroes in a disadvan

taged category and all or substantially all of the whites in

a favored category, the Supreme Court has found this to

suffice to prove discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The Court is not to be deceived by state

officials who administer laws that are fair on their face

“ with an evil eye and an uneven hand” .11 A yardstick for

proof is found commensurate with human experience. The

Courts have kept abreast of legislative and administrative

ingenuity of state officers seeking to evade the positive man

dates of the Fourteenth Amendment.

II.

Payment of Less Salary to Negro Public School

Teachers Because of Race Is in Violation of

Fourteenth Amendment.

In states where separate schools are maintained there

has been a policy of paying Negro public school teachers

less salary than white teachers because of race {supra, pp.

18, 19). For years this policy was unchallenged by legal

10 316 U. S. 401, 404.

11 Yick W o v. Hopkins, supra.

28

action. However, since 1939 there has developed a line of

decisions in federal courts firmly establishing the principle

that the payment of unequal salaries to public school teach

ers because of race or color is unconstitutional.

A.

In General.

In Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk™ the Cir

cuit Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reversed a

decision sustaining a motion to dismiss a complaint similar

to the one in this case. The question was as to the legality

of a salary schedule providing lower minimum and maxi

mum salaries for Negro teachers than for white teachers

in the public schools of Norfolk.

In the opinion for the Circuit Court of Appeals, Judge

P ark kb, after quoting pertinent paragraphs of the com

plaint, stated:

"That an unconstitutional discrimination is set

forth in these paragraphs hardly admits argument.

The allegation is that the state, in paying for public

services of the same kind and character to men and

women equally qualified according to standards which

the state itself prescribes, arbitrarily pays less to

Negroes than to white persons. This is as clear a

discrimination on the ground of race as could well be

imagined and falls squarely within the inhibition of

both the due process and the equal protection clauses

of the 14th Amendment. . . . ” (112 F. (2d) 992 995-

996.) * 18

12 112 F. (2d) 992 (1940) ; certiorari denied, 311 U. S. 693.

18 See also Mills v. Lowndes, et al., 26 F. Supp. 792 (1939);

Mills v .Board of Education et al., 30 F. Supp. 245 (1940) • Thomas

v. Hibbitts et al., 46 F. Supp. 368 (1942).

29

B.

Minimum Salary Schedules.

The first Mills ease,14 involved the question of the con

stitutionality of a statutory minimum salary schedule pro

viding a lower minimum salary for Negro teachers than for

white teachers of equal qualifications and experience. The

second Mills case,15 involved a county salary schedule pro

viding lower minimum salaries for Negro teachers and prin

cipals than for whites. It should be noted, however, that

in the second Mills case, the School Board paid salaries to

white and Negro teachers higher than the minimum pro

vided by their county scale and sought to justify the higher

salaries for white principals on the grounds that the white

principals had “ superior professional attainments and

efficiency” to that of the plaintiff. The School Board also

sought to justify the disparity in salaries on the grounds

that the Negro teachers as a group were inferior because

Negro pupils made lower grades in a county-wide examina

tion than white pupils. Both of these contentions were

found to be unsubstantial and a permanent injunction was

issued by the Court against discrimination because of race

or color.

C.

Economic Theory.

In the case of Thomas v. Hibbitts, et al., supra, the local

School Board of Nashville, Tennessee, sought to evade the

prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment by establishing

salary schedules on the basis of “ colored” and “ white”

schools. At the trial the lower scale for teachers in colored

schools was explained on the grounds that Negro teachers

14 Mills v. Lowndes, et al., supra.

15 Mills v. Board of Education, supra.

30

did not need as much money for living purposes as white

teachers. This “ economic theory” was dispelled by the

decision in that case granting a permanent injunction

against the maintenance of the policy, custom and usage of

paying teachers in colored schools less than the salaries

paid teachers in white schools.

Following these reported decisions several school boards

abolished all salary schedules which were discriminatory on

their face and set up in place thereof either (1) variable

salary schedules allowing discretion in the payment

of salaries on the basis of merit, or (2) adoption of rating

systems as a basis of payment of salaries.

D.

Variable Salary Schedules.

In the case of Roles v. School Board of the City of New

port News,16 District Judge L u th er W ay disposed of the

so-called variable schedule as follows:

“ With respect to the variable schedule which has

been frequently referred to both in the testimony

and arguments, the Court was at first favorably in

clined to that type of schedule. It not infrequently

occurs that two principals or teachers, without re

gard to whether they are white or colored, appearing

to have of record the same professional qualifications,

are not in truth and fact equally qualified to perform

the duties assigned to them. One may possess strong

personality and aptitude for the performance of his

or her duties that the other will never acquire no

matter how long he or she may engage in school

work, and that observation is just as applicable to

colored teachers and principals as to white teachers

and principals. In fact, it is a rule that applies to all

. 18_Civil Action No. 6 (1943), U. S. District Court for the Eastern

District of Virginia, unreported; copy of this opinion appears in this

brief in Appendix C.

31

activities of life. For that reason the Court was at

first impressed with the argument in favor of the

allowance of a variable schedule. However, when the

evidence was introduced it disclosed that the variable

schedule, although it is said to have been under con

sideration for sometime prior thereto, was not put

in force until after the demands of the plaintiff and

her associates had been made upon the School Board

for equalization of the salaries, without regard to

race or color. This, in itself, gave rise to the idea

that the variable schedule might be an after-thought

that resulted from the demands of the plaintiffs

rather than from a real intention to use a variable

schedule which takes into consideration the purely

personal qualifications of principals and teachers, as

well as other matters. However, the evidence went

much farther than that. It disclosed without any

substantial conflict that in every instance where spe

cial treatment was given to a white teacher or prin

cipal on account of his or her personal qualifications,

such principal or teacher received favorable treat

ment in the way of increased compensation, while in

no instance had such favorable treatment been ac

corded to a colored principal or teacher on account of

his or her special personal qualifications. Under

these circumstances the Court does not feel justified

in approving in its decree the variable schedule. ’ ’

The cases cited above show reasoning parallel to that in

the decisions on the exclusion of Negroes from jury service.

The Mills cases declared that salary schedules which on

their face showed lower salaries for Negro teachers than

for white teachers were unconstitutional. The Alston case

declared that minimum salary schedules which on their face

showed a difference because of race were unconstitutional.

These decisions are closely similar to those concerning stat

utory exclusion of Negroes from jury service {supra, p. 20).

The Hibbitts and Roles cases met the question of dis

criminatory actions by school officials acting without benefit

32

of either statutory or administrative salary schedules dis

criminatory on their face. These decisions are similar to

those jury exclusion cases from Neal v. Delaware, supra, to

Hill v. Texas, supra.

III.

The Policy, Custom and Usage of Fixing Sal

aries of Public School Teachers in Little Rock

Violates the Fourteenth Amendment.

In the instant case we begin with an examination of the

salaries of white and Negro teachers and find that in every

single instance Negro teachers get less salary than white

teachers with equal qualifications and experience in the

teaching profession.17 There is very little difference be

tween the racial differential in salaries in Little Rock and

in the other cases mentioned above. The appellees all deny

that there is any written salary schedule in existence in

Little Rock. They also deny that there is any intentional

discrimination because of race or color. The main defense

is that they established a rating system after the salaries

had been fixed and that the ratings given the teachers justi

fied the difference in salaries being paid Negro teachers.

In the Little Rock school system it is admitted that the

appointment and fixing of salaries of teachers is done by

the Superintendent of Schools by means of recommenda

tions to the Personnel Committee, which in turn recom

mends to the Board. It is also admitted that the Personnel

Committee and the members of the Board do not usually go

behind the recommendations of the Superintendent. The

present Superintendent has been in office since 1941 and

testified that the present salaries are much the same as the

salaries he found when he took office and although he has

17 See tables in Appendix B,

B3

made a few adjustments “ in the main they are much

the same” (R. 183). The Superintendent also testified that

he did not know what bases were used for the fixing of sal

aries prior to his administration (R. 192). He also testified

as follows:

“ Q. I will ask you if it is not a fact if prior to

your coming into the system, the difference was based

solely on the grounds of race the same difference

would be carried on today? A. It would be so in

many cases” (R. 183).

Comparative tables showing the salaries of white and

Negro teachers according to qualifications, experience and

school taught have been prepared from the exhibits filed

in the instant case and are attached hereto as Appendix B.

According to these tables “ no one colored teacher receives

so much salary as any white teacher of similar qualifica

tions and experience” . These facts were admitted by

.Superintendent Scobee (R. 497). This brings the instant

case clearly within the rule as established in the Mills case,

which rule was later approved by the Circuit Court of

Appeals in the Alston case, supra.

The present differential in salaries of white and Negro

teachers is the result of a combination of discriminatory

practices of the defendants forming a policy, custom and

usage extending over a long period of years. These prac

tices have been:

A. A general over-all policy of paying Negro teachers

less salary than white teachers.

B. A policy of fixing lower initial salaries for new Negro

teachers than for new white teachers.

C. A system of flat salary increases providing larger in

creases for all white teachers than for any Negro

teacher.

34

D. A system of distributing supplementary payments on

an unequal basis because of race.

A.

General Policy of Appellees.

The facts in the instant case are peculiarly in the hands

and knowledge of the appellees. It was, therefore, neces

sary to develop a large part of the appellant’s case by testi

mony from the appellees called as adverse witnesses.

The appellees have repeatedly classified teachers by race

in fixing salaries. The appellees admitted that for many

years it has been the policy of the Personnel Committee to

recommend lower salaries for Negro teachers than for white

teachers new to the system (R. 36).

(1)

Cultural Background.

The appellees attempt to explain this differential in

salaries in several ways. For example, one appellee testi

fied that Negro teachers as a whole are less qualified (R.

39); and that the majority of the white teachers “ have

better background and more cultural background” (R. 62).

The President of the Board testified as to the Negro teach

ers that: “ I did not think they were all qualified as well as

the white people” (R. 22).

This is but a rationalization of the notion that Negroes

as a group should be paid less than whites for equal work.

The unconstitutionality of any such differentiation has al

ready been discussed.

35

(2)

Economic Theory.

Another appellee testified: “ I think I can explain that

this way; the best explanation of that, however, is the

Superintendent of the Schools is experienced in dealing and

working with teachers, white and colored. He finds that we

have a certain amount of money, and the budget is so much,

and in his dealing with teachers he finds he has to pay a

certain minimum to some white teachers qualified to teach,

a teacher that would suit the school, and he also finds that

he has to pay around a certain minimum amount in order

to get that teacher, the best he can do about it is around

$800 to $810, to $830, whatever it .may be he has to pay that

in order to pay that white teacher that minimum amount,

qualified to do that work. Now, in his experience with

colored teachers, he finds he has to pay a certain minimum

amount to get a colored teacher qualified to do the work. He

finds that about $630, whatever it may be” (R. 120).

Further explanation is that since there is a general

understanding that the board can get Negro teachers for

less it has been the policy of the board to offer them less

than white teachers of almost identical background, qualifi

cations and experience (R. 120). It was also revealed that

Negroes are paid less because: “ They are willing to accept

it, and we are limited by our financial structure, the tax

ation is limited, and we have to do the best we can” , and

also: “ the Negro can live cheaper, and there are various

reasons” (R. 121). The president of the board testified that

they paid Negroes less because they could get them for less

(R. 23). Still another member of the board, in response to

a question: “ If you had the money, would you pay the

Neg-ro teachers the same salary as you pay the white teach

ers !” replied that: “ I don’t know, we have never had the

36

money” (R. 59). Superintendent Scobee testified that he

could not fix the salaries of Negro high school teachers on

any basis of merit because “ my funds are limited” (R. 192).

In the case of Thomas v. Hibbitts et al.,17a decided by

District Judge E lm er D. D avies, sitting in the Middle Dis

trict of Tennessee, the defendants offered as a defense on

part of the Board of Education that the salary differential

was an economic one and not based upon race or color; and

also, that salaries were determined by the school in which

the teacher was employed. In deciding these points Judge

D avies wrote:

_ “ The Court is unable to reconcile these theories

with the true facts in the case and therefore finds

that the studied and consistent policy of the Board

of Education of the City of Nashville is to pay its

colored teachers salaries which are considerably less

than the salaries paid to white teachers, although the

eligibility and qualifications and experience as re

quired by the Board of Education is the same for

both white and colored teachers; and that the sole

reason for this difference is because of the race of

the colored teachers.” (46 F. Supp. at 368.)

B.

Minimum Salaries for New Teachers.

All of the appellees denied that there ever has been a

salary ‘ ‘ schedule ’ ’ for the fixing of teachers ’ salaries. The

appellant, however, produced a salary schedule for Negro

teachers providing a minimum salary of $615 (R. 716).

Superintendent Scobee denied ever having seen such a

schedule but admitted that since 1939 “ practically all” new

Negro teachers had been hired at $615 while all new white

teachers hired during the same period were paid not less

than $810 (R. 316).

17a46 F. Supp. 368.

37

In 1937 the School Board adopted a resolution whereby

a “ schedule” of salaries was established providing that new

elementary teachers were to be paid a minimum of $810 (B.

577). Although Superintendent Scobee attempted to ex

plain that the word “ schedule” did not mean schedule, he

admitted that since that time all white teachers had been

hired at salaries of not less than $810 (B. 285-286).

O )

The Little Rock Salary Schedule.

In the instant case the appellee sought to escape the rule

as established in the Mills and Alston cases, supra, by de

nying that they have a salary schedule. They testified that

all teachers, white and Negro, were hired on an individual

basis without regard to race or color. All of the appellees

denied that there was any schedule establishing lower sal

aries for Negro teachers because of race or color. They,

however, admitted that in actual practice all new Negro

teachers were hired at either $615 or $630 while all new

white teachers were hired at not less than $810 (B. 84, 100,

189). The validity of their method of fixing salaries is

determined by the actual practice rather than the theory.

In the second Mills case Judge Chesnttt held that a

minimum salary schedule adopted by local school board pro

viding a higher minimum salary for white teachers than for

Negro teachers was unconstitutional despite the fact that

the board paid salaries higher than the schedule.

On the basis of the testimony of the appellees there is

no essential difference between the facts in the Alston case

and the instant case. In the Alston case all white elemen

tary teachers were paid a minimum of $850 and white high

school teachers were paid a minimum of $970, while all

Negro elementary teachers a minimum of $597.50 and Negro

38

high school teachers $699, pursuant to a written salary

schedule. In Little Rock all white elementary teachers were

paid a minimum of $810 and white high school teachers a

minimum of $900 while all Negro elementary teachers were

paid $615 and Negro high school teachers $630 in the absence

of a written salary schedule.

There is no magic in a written schedule as compared with

a schedule in fact which is not in writing. Although appel

lees deny they have a salary schedule Superintendent Seo-

bee admitted all salaries were within certain limits:

“ Q. jOne second. How did it happen that your

judgment always runs along in certain figures,

namely, $615, $630 for Negroes, and $810 and $900

for white teachers, how does it run there all of the

time? A. I cannot answer” (R. 329).

Of course, Superintendent Scobee denied that race was

involved in this system (R. 329-330).

All efforts of Superintendent Scobee to deny that he

followed a schedule were dispelled by his testimony that

although some white high school teachers were willing to

work for less he insisted on paying them $900 (R. 329).

In the Mills case, supra, Judge C hesntjt stated:

“ • • • In considering the question of constitutional

ity we must look beyond the face of the statutes them

selves to the practical application thereof as alleged

in the complaint . . . ” 18

Superintendent Scobee testified that the difference in

salaries paid new white and Negro teachers has been based

upon certain intangible facts, most of which he had forgot

ten by the the time of the trial. Information for these

intangible facts used1: in fixing salaries was obtained from

18 See also Yick W o v. Hopkins, supra.

39

letters and telephone conversations in addition to the appli

cation blanks filed by the applicants (R, 316). In actual

practice this procedure itself discriminates against Negro

applicants.

The testimony of Superintendent Scobee reveals the

extent of this discrimination. Two teachers, one white and

one colored, were being considered for teaching positions.

The superintendent, following his custom, telephoned the

college professor of the white applicant and received a very

high recommendation for her. He did not either telephone

or write the professors of the Negro applicant. As a result

he offered the white applicant $810 as an elementary teacher

and the Negro $630 as a high school teacher despite the fact

that their professional qualifications were equal (R. 317-

320).

The extent of the discrimination against Negro teachers

brought about by this unequal treatment is emphasized by

further testimony of Superintendent Scobee that:

a. Where teachers had similar qualifications, the super

intendent would solicit recommendations for one and

receive good recommendations, yet fail to make such

inquiry for the other. In such case the applicant

whose recommendations he solicited and obtained

would appear to him to be the better teacher (R. 317).

b. He seldom sought such additional information or

recommendation about the Negro applicants (R. 327).

c. Personal interviews were used in the fixing of sal

aries (R. 323); and played a large part in determin

ing the amount of salary (R. 323).

d. He did not even interview all of the Negro applicants

(R. 346).

40

In another recent case involving the question of exclu

sion of Negroes from jury service facts were presented

which are closely similar to the facts presented by the de

fendants in this case. In the jury case, Mr. Chief Justice

S tone for the Supreme Court stated:

‘ ‘ Discrimination can arise from the action of com

missioners who exclude all Negroes whom they do

not know to be qualified nor seek to learn whether

there are in fact any qualified Negroes available for

jury service.” {Hill v. Texas, supra.)

In the instant case the practice of Superintendent

Scobee outlined above is just as discriminatory as the policy

and custom of the jury commissioners in the Hill case and

in itself violates the Fourteenth Amendment.

C.

Salaries of Older Teachers and Flat Increases.

According to the tables of teachers’ salaries for 1941-42

attached hereto as Appendix B no Negro teacher is being-

paid a salary equal to a white teacher with equal qualifica

tions and experience. This fact is admitted by Superinten

dent Scobee (R. 497-498). These salaries for 1941-42 were

not fixed on any basis of merit of the individual teachers

(R. 192).

All of the public schools in Little Rock, both white and

Negro, are part of one system of schools and the same type

of education is given in all schools, white and Negro (R.

182). The same courses of study are used. All schools are

open the same number of hours per day and the same num

ber of days (R. 195). The same type of teaching is given

in all schools. Negro teachers do the same work as the

white teachers (R. 191).

41

The appellees testified that there is a policy to pay high

school teachers more than elementary teachers (E. 183) :

and to pay teachers with experience more than new teachers.

It is also admitted that the Negro teachers at Dunbar High

School are good teachers and do practically the same work

as other high school teachers in the white school (E. 191).

However, the plaintiff and twenty-four other Negro high

school teachers of Dunbar with years of experience are now