Order

Public Court Documents

February 3, 1986

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Order, 1986. e3627ac1-b9d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db9540d7-e58d-4c57-a942-1a18e239c8e5/order. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

w® » oy LOE

it Frc J

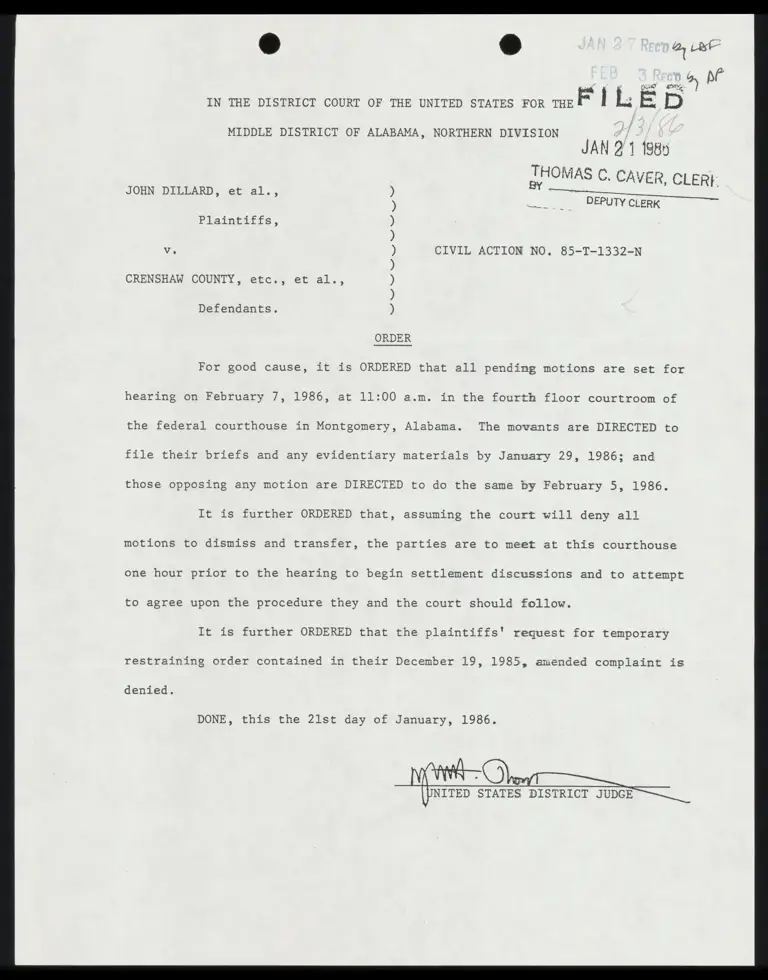

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR IL I L E D

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, NORTHERN DIVISION

JAN 2'1 198

HHOMAS C. CAVER, CLER}:

JOHN DILLARD, et al., ) gi RR

___ DEPUTY CLERK

Plaintiffs, )

)

Vis ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 85-T-1332-N

)

CRENSHAW COUNTY, etc., et al., )

)

Defendants. )

ORDER

For good cause, it is ORDERED that all pending motions are set for

hearing on February 7, 1986, at 11:00 a.m. in the fourth floor courtroom of

the federal courthouse in Montgomery, Alabama. The movants are DIRECTED to

file their briefs and any evidentiary materials by January 29, 1986; and

those opposing any motion are DIRECTED to do the same by February 5, 1986.

It is further ORDERED that, assuming the court will deny all

motions to dismiss and transfer, the parties are to meet at this courthouse

one hour prior to the hearing to begin settlement discussions and to attempt

to agree upon the procedure they and the court should follow.

It is further ORDERED that the plaintiffs' request for temporary

restraining order contained in their December 19, 1985, amended complaint is

denied.

DONE, this the 21st day of January, 1986.

NH —

\PNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE ~—___