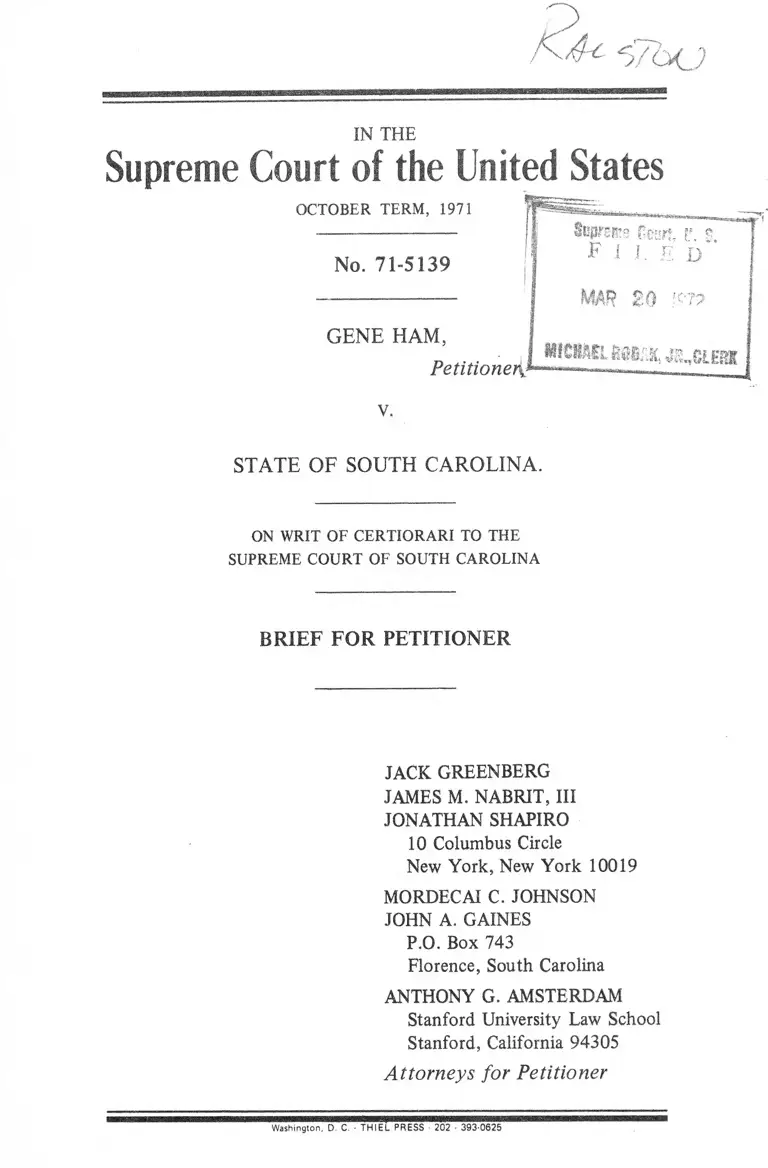

Ham v. South Carolina Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

March 20, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ham v. South Carolina Brief for Petitioner, 1972. 0304122e-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/db9ad281-913b-429b-a5c0-13eb2c72cd36/ham-v-south-carolina-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

A M 5 / 6 < J

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

J fS B S

Sup,

I F

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

No. 71-5139

GENE HAM,

Petitioneri*

v.

Scprsfits ficajt. p s

F I J. E D "

MAR 20 N7?

i f feaiiii, as.,sing

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

MQRDECAI C. JOHNSON

JOHN A. GAINES

P.O. Box 743

Florence, South Carolina

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioner

Washington, D. C. " t h ie T PRESS 202 ■ 393-0625

( i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

OPINION BELOW ................................ .. ........................... .. 1

JURISDICTION ........................... 1

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS INVOLVED............................. 2

QUESTION PRESENTED .......... 2

STATEMENT OF THE C A SE..................................................... 2

ARGUMENT

The Trial Judge’s Refusal To Examine the Jurors on Voir

Dire as to Whether They Were Prejudiced Against Peti-

titioner Because of His Race or Because of Their Exposure

to Pretrial Publicity Violated Petitioner’s Right to an

Impartial Jury Guaranteed by the Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution.......... .. 6

CONCLUSION........................... ...................................................... 18

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Aldridge v. United States, 283 U.S. 308 (1931)............. 6, 12, 1 6 ,18

Bailey v. United States, 53 F.2d 982 (5th Cir. 1 9 3 1 )................. 12

Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238 (1 9 6 9 ).................... ................. 8

Brown v. United States, 119 U.S. App. D.C. 203, 338 F.2d

543 (D.C. 1964)............................................... .......................... 12

Carter v. Jury Commissioners, 396 U.S. 320 (1 9 7 0 ).................... 9

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 (1964 )......................... .. 8

Dennis v. United States, 339 U.S. 162 (1 9 5 0 )........................... 10, 12

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1 9 6 8 )................................ . 6

Epps v. State, 102 Ind. 539, 1 N.E. 491 (1885)........................... 14

Estes v. Texas, 381 U.S. 532 (1965) ............................................. 7

Fendrick v. State, 39 Tex. Cr. 147, 45 S.W. 589 (1 8 9 8 )............ 17

Foute v. State, 85 Tenn. 712 (1 8 8 5 ).......................................... .. 14

Frasier v. United States, 267 F.2d 62 (1st Cir. 1959).......... .. 16

Gholston v. State, 221 Ala. 556, 130 So. 69 (1930) ............ .. . 16

Giles v. State, 229 Md. 370, 183 A.2d 359 (1962) ....................... 16

Groppi v. Wisconsin, 400 U.S. 505 (1971) .................... .. 6, 8, 17

Hamer v. United States, 259 F.2d 274 (9th Cir. 1958), cert.

denied, 359 U.S. 196 (1959)....................... ............................... 13

Herndon v. State, 178 Ga. 832, 174 S.E. 597 (1934) . . . . . . . . 16

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 (1961) ...................................6, 7, 9, 17

Johnson v. State, 88 Neb. 565, 130 N.W. 282 (1911)................. 16

Jones v. People, 23 Colo. 276, 47 Pac. 275 (1898) .................... ] i

Kiernan v. Van Schaik, 347 F.2d 775 (3rd Cir. 1965). ............ 13

King v. United States, 362 F.2d 968 (DC. Cir. 1966)................. 16

Lewis v. United States, 146 U.S. 370 (1892).............................. 9 ,10

Marson v. United States, 203 F.2d 904 (6th Cir. 1953)............... 17

Morford v. United States, 339 U.S. 258 (1950) ............................ 12

Nobles v. State, 127 Ga. 212, 56 S.E. 125 (1906) ....................... 14

North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711 (1 9 6 9 ) ................... 7

Owens v. State, 177 Miss. 488, 171 So. 345 (1936) .................... 16

Parker v. Gladden, 385 U.S. 363 (1966)...................................... . 7

People v. Boulware, 29 N.Y.2d 135, 324 N.Y.S.2d 30 (1971) . . . 12

People v. Decker, 157 N.Y. 186, 51 N.E. 1018 (1 8 9 8 )....... 17

People v. Wheeler, 96 Mich. 1, 55 N.W. 371 (1 8 9 3 )............... . 11, 14

Pinder v. State, 27 Fla. 370, 8 So. 837 (1891) .......................... 16

Pointer v. United States, 151 U.S. 396 (1894)........................... 10,12

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) .......................................... 8

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 723 (1963)................................. 7 ,9 , 17

Roberson v. State, 456 P.2d 595 (Okla. Crim. 1968) .................. 14

Santobello v. New Y ork,___ U .S .____, 30 L.Ed.2d 427

(1971) .......................................................................................... 8

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966) ................................... 7, 17

Silverthorne v. United States, 400 F.2d 627 (9th Cir. 1968) . . 15,17

Smith v. United States, 262 F.2d 50 (4th Cir. 1959) ................. 16

State v. Britt, 237 S.C. 293, 117 S.E .2d 379 (1960) ................. 17

(ii)

State v. Dooley, 89 Iowa 584, 57 N.W. 414 (1 8 9 4 ).................... 14

State v. Gurrington, 11 S.D. 178, 76 N.W. 326 (1 8 9 8 )............... 14

State v. Hoagland, 39 Idaho 405, 228 Pac. 314 (1924)............... 14

State v. Higgs, 143 Conn. 138, 120 A.2d 152 (1 9 5 6 ).................. 16

State v. Jones, 175 La. 1014, 144 So. 899 (1932) ....................... 16

State v. McAfee, 64 N.C. 339 (1870)............................................. 17

State v. Mann, 83 Mo. 489 (1884).................................................. 14

State v. Marfaudille, 48 Wash. 117, 92 Pac. 939 (1907)............... 14

State v. Mercier, 98 Vt. 368, 127 Atl. 715 (1925) .................... 14

State v. Morgan, 23 Utah 212, 64 Pac. 356 (1900) .............. 14

State v. Peterson, 255 S.C. 579, 180 S.E. 2d 341......... 17

State v. Pyle, 343 Mo. 875, 123 S,W.2d 166 (1938) .................. 36

State v. Smith, 49 Conn. 376 (1 8 8 1 )............................................. 11

State v. Stonestreet, 112 W. Va. 668, 116 S.E. 378 (1932) . . . . 14

Stone v. United States, 324 F.2d 804 (5th Cir. 1963), cert.

denied, 376 U.S. 938 (1964)............................................... .. 13

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880 )......................... .. 7

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) ........................................ 16

Swenson v. Bosler, 386 U.S. 258 (1967)........................................ 7

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 (1960)................. 7

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1 9 7 0 )........................................ 9

Turner v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 466 (1965)..................................... 7

United States v. Carter, 440 F.2d 1132 (6th Cir. 1 9 7 1 ) ..........15, 16

United States v. Dennis, 183 F.2d 201, n. 35 (2d Cir. 1951,

affd, 341 U.S. 494 (1951) .................................................... .. 16

United States v. Gore, 435 F.2d 1110 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ............ 16, 17

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967 )........................................ 7

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78 (1970) . ............. ........................ 10

Zancannelli v. People, 63 Colo. 252, 165 Pac. 612 (1917).......... 14

Statutes and Court Rules:

Ala. Code, Tit. 15, §52 (1 9 5 8 )....................................................... 13

§55 ....................................................... 11

{ Hi)

Alaska Stat. §09.20.090 (1962).................................................... 11, 13

Ariz. R. Crim. P. 217 (1956) .......................................................... 11

219 ............................................................................ 13

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 39-226 (1962) ................................. .. 14

§43-1915 (1964).................................................... 11

Cal. Pen. Code § 1078 (West’s 1969).......................................... 14

§ 1066 (West’s 1970)............................................... 11

Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. §51-240 (Cum. Supp. 1 9 6 7 )................. .. 14

Del. Code §11-3301 (1953) ............................................................ 14

Del. Super. Ct. (Crim.) R. 24 (1 9 4 8 ) .......................................... 11,14

D.C. Code Gen Sessions Ct. R. 24 (1961) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11, 14

Fed. R. Crim. P. 2 4 (a ) ........................ 11,14

Fla. Stat. Ann. §913-02(2) (1969)........................... 11

Fla. Stat. Crim. Pro. R. § 1.290 (1968) . ........................... 14

Ga. Code Ann. §59-804 (1965)..................................... 11

§59-806 ............... ......................................... ” ’ ’ 14

Hawaii Rev. Stat. §635-27 (1968) ....................... ..................... .. . 14

§635-28................................................ 11

Idaho Code Ann. §§19-2012, 2013, 2016 (1948)......................... H

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38, §115-4 (1965) .......................................... 11,14

Ind. Stat. (Bums) §9-1054 (1956 ).................................................. 11

Iowa Code Ann. §779.6 (1946) ..................................................... 11

Kan. Stat. §22-3410 (1 9 7 1 ) ............................. H

§22-3408(3) ................................................................... 14

Ky. Rev. Stat. R. Crim. P. §§9.36,9.38 (1970) • ....................... 11, 14

La. Const. Art. I § 1 0 ...................................................................... 11,14

La. Stat. Ann. Code Crim. P. §786 (1 9 6 7 ) ................................... 14

§ 797 ............................................... 11

Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. Tit. 15, § 1258 (1 9 6 9 )................................... 14

§ 1259 ................................................ 11

Md. Ann. Code, Tit. 51, §§10, 18 (1957)......................... .. H

Rule 745 (1971)................................................... 14

Mass. Ann. Laws ch. 234, §28 (1956) ........................................ 11,14

(iv)

Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. §768.8 (1 9 4 8 ) ................................... .. . 14

§768.9 .......................................... 11

Minn. Stat. Ann. §631.26 (1945) ................. ............................... 14

§631.28 ............................................................ 11

Miss. Code Ann. § 1802 (1 9 4 2 ) .................................................. 11,14

Mo. Rev. Stat. §§546.120-546.160 (1959) ....................... 11

Mont. Rev. Code, Tit. 95, § 1909 (1947) ...................................... 11

§ 1909(c)...................... 14

Neb. Rev. Stat. §29-2004 (1964)...................... 14

§29-2006 ................................................................. 11

Nev. Rev. Stat., Tit. 14 § 175.031 (1 9 6 7 ) ..................................... 14

§175.036 . ........................... 11

N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann., ch. 500-A:32; 606:1 (Cum. Supp.

1 9 7 1 ) ....................................................................................... .. . 14

ch. 606, §3 (1 9 5 5 )..................................... H

N.J. Stat. Ann. Tit. 2A §78-4 (1952) . ........................................... 14

2A §78-7 ......................................................... 11

N.M. Stat. §19-1-14 (1953) ........................... n

§ 21-1-1 (47a)............................................ 14

N.Y. Crim. Proc. L. §270.15 (McKinney’s 1 9 7 1 )......................... 14

§270.20 ...................... i i

N.C. Gen Stat. §9-15 (1969)...................... ............................. .. .11, 14

N.D. Cent. Code §29-17-28 (1960) ............................................... 14

§29-17-32......... 11

Ohio Rev. Code §2945.24 (1 9 7 1 ) .................... ............................. n

§2945.27 ...................................................... 14

Okla. Stat. Ann. §656 (1969) .......................................................... 11

Ore. Rev. Stat. § 136.210 (1961 )..................................................... 14

§§ 17.165,136.210 ...................... 11

Pa. Stat. Tit. 19 §811 (1 9 6 4 ).................................................... 11, 14

R. I. Gen Laws §9-10-14 (1956).................................................. 11,14

S. C. Code of Laws § 38-61 (1962) 13

§38-202 ............................................... 5,11, 14, 17

S.D. Comp. Laws §§23-43-28, 23-43-29 (1967) . . .................. .. . n

Tenn. Code §22-301 (1 9 5 6 ) .................................................. n

Tex. Code Crim. P. (Vernon’s Ann.) Art. 35.16 (1965) . . . . . . . n

35 .17 ...................... .. . 14

United States Code, Tit. 28, § 1257(3).......................................... 2

Utah Code §77-30-16 (1953) ......................................................... 11

Va. Code §§8-199, 19.1-206 (1960).......................................... 11, 14

Vt. Ann. Stat., Tit. 12 § 1941 (1947)............................................. 11

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §10.40.040 (1961). . ......................... .. 11

W. Va. Code §62-34 (1966) ......................................................... 11

Wis. Stat. Ann. §§957.14, 270.16 (1957) .............................. .. 11,14

Wyo. Stat. R. Crim. P. 25 (1 9 6 8 ) ............ ................... .............. 11, 14

Wyo. Stat. §7-222 (1957) .................................................. ........... 11

Other Authorities:

ABA PROJECT ON STANDARDS FOR CRIMINAL

JUSTICE, Fair Trial and Free Press, §2.3, 126-127

(Approved Draft 1968) ................................ ..................... 9 ,15 ,17

ABA PROJECT ON STANDARDS FOR CRIMINAL

JUSTICE, Trial by Jury, §2.4 (Supp. 1968) . 9, 11, 13, 14, 17, 18

ALI CODE OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE (1931)...................... 11,14

1 ANNALS OF CONG. 435 (1 7 8 9 )......... 10

3 BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES 363 ................................. 13

1 BUSCH, LAW AND TACTICS IN JURY TRIALS 9

(Encyl. ed. 1 9 5 9 ) ........................................................................ 9

DEVLIN, TRIAL BY JURY 30-31 (1956) ................................ 9, 13

FORSYTH, HISTORY OF TRIAL BY JURY 175 (1852 ).......... 8

HELLER, THE SIXTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTI

TUTION OF THE UNITED STATES 24 (1951) .................... 10

1 LETTERS AND OTHER WRITINGS OF JAMES

MADISON 491 (1856)............................................... io

Note, Community Hostility and the Right to an Impartial

Jury, 60 COLUM. L. Rev. 349 (1 9 6 0 ) ..................................... 13

2 WRIGHT, FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE

38(1969)

(vi)

11

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

No. 71-5139

GENE HAM,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina is

reported at 256 S. C. 1, ISO S.E.2d 628 (1971) and is set

out in the Appendix (A. 100). Petitioner was convicted

upon trial by jury in the Court of General Sessions of

Florence County, South Carolina, and there is no opinion

with respect to that conviction.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

was entered on April 7, 1971 and a timely petition for

rehearing was denied on April 28, 1971 (A. 106). The

petition for writ of certiorari was filed on July 24, 1971

and certiorari was granted on January 24, 1972. The juris

diction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C

§ 1257(3).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution

provides in part:

“In all criminal prosecutions the accused shall enjoy

the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial

jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall

have been committed . .

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Consti

tution provides in part:

“ Section 1 . . . No State shall make or enforce any

law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities

of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State

deprive any person of life, liberty, or property with

out due process of law; nor deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws.”

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the trial judge’s refusal to examine the jurors

on voir dire as to whether they were prejudiced against

petitioner because of his race or because of their exposure

to pretrial publicity violated petitioner’s right to an

impartial jury, guaranteed by the Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioner Gene Ham is a black civil rights worker who

has long been active in the civil rights movement in Flor

ence County, South Carolina (A. 73). On June 3, 1970

he was convicted after a jury trial in the Court of General

Sessions of Florence County of possession of marijuana and

sentenced to eighteen months upon the public works of the

county or in the state penitentiary (A. 2).

3

Petitioner was arrested by three police officers on the

afternoon of May 15, 1970 on the basis of several warrants

that had been issued for his arrest (A. 4-7, 49). After his

arrest he was frisked on the street, placed in a patrol car

and taken to the police station (A. 75). There he was

booked and asked to take everything out of his pockets

(A. 50). According to the police officers, he removed

eight packages from his pocket which were opened,

examined, and found to contain somewhat less than an

ounce of marijuana (A. 50, 60). An additional warrant

charging him with possession of marijuana was then issued

(A. 53).

After a preliminary hearing on May 28th and 29th,

petitioner was bound over to the grand jury on each of the

five charges against him, including possession of marijuana

(A. 2). He was indicted on each charge on June 1st

(A. 2), and on June 2nd the possession of marijuana

charge was called for trial in the General Sessions Court

(A. 8).

Petitioner’s motion for a continuance on the ground that

he had not been able, on one day’s notice, to file motions

or prepare for trial was denied, and counsel was directed to

make all motions orally (A. 11). His motion for a

change of venue or for a continuance on the ground of

prejudicial publicity was summarily overruled (A. 12).

A brief hearing was then held on his motion to strike the

petit jury venire on the ground that Negroes had been sys

tematically excluded (A. 17). Despite his showing that

only six (17%) of the thirty-six petit jurors who were

available for his case were black although 32% of the

names in the jury box were of blacks, and that the trial

venire was selected from slips of paper on which the race

of the juror was indicated, the motion was denied (A. 31-32).

Over petitioner’s objection, the trial on the merits was set

for the following day (A. 32).

At the beginning of the selection of the jury, petitioner

requested that the judge put the prospective jurors on voir

dire and ask them the following questions:

4

1. Would you fairly try this case on the basis of the

evidence and disregarding the defendant’s race?

2. You have no prejudice against negroes? Against

black people? You would not be influenced by the

use of the term “black?”

3. Would you disregard the fact this defendant wears

a beard in deciding this case?

4. Did you watch the television show about the local

drug problem a few days ago when a local police

man appeared for a long time? Have you heard

about recent newspaper articles to the effect that

the local drug problem is bad? Would you try this

case solely on the basis of the evidence presented

in this courtroom? Would you be influenced by the

circumstances that the prosecution’s witness, a police

officer, has publicly spoken on TV about drugs?”

(A. 35-36).

The judge refused to ask any of these proposed questions

on the ground that “ [tjhey were not relevant” (A. 35).

Instead, he asked generally whether any member of the

panel was related by blood or marriage to petitioner

(A. 35), and addressed the following three questions to

each juror individually:

“Have you formed or expressed any opinion as to the

guilt or innocence of the defendant?

“Are you conscious of any bias for or against him?

“Can you give the State and the defendant a fair

trial?” (A. 36-48).

Tito© jurors were excused by the court because of their an

swers to these questions.1 No one was challenged for cause

by either the State or petitioner, but each side exhausted its

five peremptory challenges (A. 37, 39, 40, 41,42, 44, 46, 47).

1 One juror answered in the affirmative to the first two questions

(A. 42), and one juror answered “no” to the third question (A. 47).

5

The State’s case consisted only of testimony that eight

packages had been discovered among petitioner’s personal

belongings when he had been searched at the police station

after his arrest (A. 50), and that the packages had been

found to contain a small quantity of marijuana (A. 60).

Petitioner took the stand in his own defense and testified

that the first time he had seen the package was when he

removed the contents of his pockets (A. 76). He stated

that he had not had the packages in his possession at any

time before he was arrested, and could only speculate that

the police officers had planted them in his pockets when

he was frisked or later at the police station (A. 77). He

also testified that he had heard that the local police were

“out to get him” because of his civil rights activities, which

included working for the Southern Christian Leadership Con

ference (SCLC) and being a member of the Bi-Racial Com

mittee of the City of Florence (A. 71, 73-74, 85).

The jury returned a verdict of guilty and, despite the fact

that it was a first offense, petitioner was sentenced to

eighteen months imprisonment (A. 92). A motion for judg

ment notwithstanding the verdict or for a new trial, which pre

served his rights on appeal under all motions and objections

raised during the trial, was denied (A. 92).

On appeal, petitioner assigned as error the refusal of the

trial court to examine the jurors on voir dire with respect

to racial prejudice or their exposure to pretrial publicity

and argued that such refusal violated his right to an impartial

jury guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution.2 A divided South Carolina Supreme Court

affirmed petitioner’s conviction. The majority held that the

trial judge had asked the basic questions required by §38-

202 S. C. Code (1962),3 and had not abused his discretion

in refusing to ask others.

2Brief of Appellant, p. 15; Reply Brief, pp. 3-7.

3This section provides:

§38-202. Jurors may be examined by court; i f not

indifferent, shall be set aside. - The Court shall, on motion

6

Noting that petitioner was a “black, bearded, civil or

human rights activist,” two of the five Justices dissented on

the ground that the trial court’s refusal to examine the jurors

was in conflict with the decision of the United States

Supreme Court in Aldridge v. United States, 283 U.S. 308

(1931), which they considered binding on the States. A

petition for rehearing was denied over the same dissenting

votes (A. 106).

ARGUMENT

THE TRIAL JUDGE’S REFUSAL TO EXAMINE THE

JURORS ON VOIR DIRE AS TO WHETHER THEY

WERE PREJUDICED AGAINST PETITIONER BECAUSE

OF HIS RACE OR BECAUSE OF THEIR EXPOSURE

TO PRETRIAL PUBLICITY VIOLATED PETITIONER’S

RIGHT TO AN IMPARTIAL JURY GUARANTEED BY

THE SIXTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS TO

THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION.

The Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments guarantee a crim

inal defendant a trial by an impartial jury. Groppi v. Wis

consin, 400 U.S. 505 Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S.

717 (1961); Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717 (1961). This Court

has said:

“In essence, the right to jury trial guarantees to the

accused a fair trial by a panel of impartial, ‘indif

ferent’ jurors. The failure to accord an accused a

fair hearing violates even the minimal standards of

due process . . . In the language of Lord Coke, a

juror must be as ‘indifferent as he stands unsworne.’

Co Litt 155 b. His verdict must be based on evi

dence developed at the trial . . .” 4

of either party in the suit, examine on oath any person who

is called as a juror therein to know whether he is related

to either party, has any interest in the cause, has expressed

or formed any opinion or is sensible of any bias or prejudice

therein, and the party objecting to the juror may introduce

any other competent evidence in support of the objection.

If it appears to the court that the juror is not indifferent in

the cause, he shall be placed aside as to the trial of that cause

and another shall be called.”

4Irvin v. Dowd, supra, 366 U.S. at 722.

7

Unless the impartiality of the jury can be assured, the fun

damental right to a fair trial will itself be rendered mean

ingless.

It cannot be doubted that the right to an impartial jury

requires a panel of jurors who are free from prejudice against

the defendant because of his race or because of their expo

sure to pretrial publicity. As long ago as 1880 this Court

held that the “apprehended existence of prejudice” against

a black criminal defendant from a jury from which blacks

had been systematically excluded required the reversal of

his conviction. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303

(1880). In order to prevent racial prejudice from affecting

the impartiality of juries, an unbroken line of cases since

that time has condemned any racial discrimination in the

jury selection process. Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545

(1967). Similarly, the right of the accused to a jury deter

mination based only upon the evidence presented at a trial

has been recognized as one of the fundamental guarantees

of due process. Irvin v. Dowd, supra, 366 U.S. at 722;

Thompson v. City o f Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 (1960). And

this Court has been particularly sensitive to the denial of

this right by prejudicial publicity and extra-judicial state

ments. Parker v. Gladden, 385 U.S. 363 (1966); Sheppard

v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966); Estes v. Texas, 381 U.S.

532 (1965); Turner v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 466 (1956);

Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 723 (1963).

It is well established that where federal constitutional

rights such as the right to an impartial trial are at stake,

federal law requires that the States make available the means

that are necessary to safeguard those rights. Swenson v.

Bosler, 386 U.S. 258 (1967).5 Only recently this Court

5 In several different areas, this Court has held that specific state

court procedures are necessary to adequately insure the protection of

federal rights. Thus, a state court is constitutionally required to give

a statement of reasons for an increased sentence after a second con

viction of a successful appellant in order to provide assurance that he

is not being penalized for the exercise of his right to appeal, North

8

recognized that since a change of venue may provide the

only means by which to assure an impartial jury, a State

could not constitutionally bar changes of venue in all mis

demeanor cases. Groppi v. Wisconsin, supra. Thus, it was

held that “under the Constitution a defendant must be

given an opportunity to show that a change of venue is

required in his case.” Id. at 511. (Emphasis in original).

Just as a defendant is constitutionally entitled to show that

a change of venue is required to insure an impartial jury,

Groppi v. Wisconsin, supra, so too must he be entitled to

an adequate means to select an impartial jury in the venue

in which he is tried. In the present case, petitioner con

tends that his right to an impartial jury can only be vouch

safed if he is given a meaningful opportunity to challenge

for cause prospective jurors who are prejudiced against him

because of his race or because of their exposure to pretrial

publicity.

The right to challenge prospective jurors for cause on

account of bias or prejudice is essential to the constitu

tional guarantee of an impartial trial because it is the prin

cipal, if not the only, means by which a criminal defendant

can secure an impartial jury.6 Even the fairest procedures

by which master jury lists are compiled can at best only

Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711 (1969); it cannot sentence a defen

dant on a guilty plea where any aspect of the prosecutor’s

plea-bargaining promise has not been kept, in order to insure against

the involuntary waiver of his constitutional right to a jury trial,

Santobello v. New York, ___ U.S. ___ , 30 L.Ed.2d 427 (1971);’

it cannot accept a guilty plea unless the prerequisites of the plea

affirmatively appear on the record, Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U.S.

238 (1969); and it must give a defendant an opportunity to introduce

evidence in support of his claim that the jury selection procedure

violated his rights under the Fourteenth Amendment, Coleman v.

Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 (1964); Reece v. Georgia, 350 U S 65

(1956).

6See W. FORSYTH, HISTORY OF TRIAL BY JURY 175 (1852);

DEVLIN, TRIAL BY JURY 30-31 (1956); Note, Community Hos

tility and the Right to an Impartial Jury, 60 COLUM. L. REV 349

354 (1960).

9

provide juries that represent a “cross-section” of the com

munity and cannot guarantee that the jurors selected will

be unbiased toward a particular defendant. Carter v. Jury

Commissioner, 396 U.S. 320 (1970); Turner v. Fouche, 396

U.S. 346 (1970). Similarly, the right to a continuance or

to a change of venue only serves to reduce the likelihood

of prejudice to a defendant which may result from com

munity hostility in connection with a particular case. Irvin

v. Dowd, supra-, Rideau v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 723 (1963).

Indeed, a continuance or change of venue is available in

many jurisdictions only after a defendant has been unable

to secure an impartial jury through his exercise of chal

lenges.7 It is, therefore, only through the right of challenge

that the defendant can eliminate from the jury which may

strip him of liberty or life those individuals who are actu

ally prejudiced against him. As one authority has stated:

“Trial by jury will be useless as a safeguard for the

subject. . . if it means trial by a packed jury. There

fore the precautions which the law takes to secure

that a jury is unbiased and independent must be

preserved . . .” 8

The right of challenge for cause on account of bias or

prejudice is also a fundamental component of the right to

a jury trial. As this Court has recognized, “the right of

challenge comes from the common law with the trial b y j^ 'j

itself, and has always been held essential to the fairness of

trial by jury.” Lewis v. United States, 146 U.S. 370, 376

(1892). As early as the middle of the thirteenth century,

Bracton wrote that exceptions could be taken to individual

jurors on the ground of a previous conviction for perjury,

serfdom, consanguinity, affinity, enmity, or close friend

ship.9 And by the middle of the fifteenth century, most of

7 ABA PROJECT ON STANDARDS FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE,

Fair Trial and Free Press, 126-2(17 (Approved Draft 1968).

8 DEVLIN, supra, n. 5, at 31

91 BUSCH, LAW AND TACTICS IN JURY TRIALS 9 (Encyl. ed.

1959).

10

the incidents of the modern jury trial, including the right

of challenge, had become settled.10 Although a specific

reference to the right of challenge was not included in the

Sixth Amendment,11 it has always been recognized in this

country as a fundamental element of a jury trial, embraced

by the guarantee of an “impartial” jury .12 It is guaranteed

to a criminal defendant under the law of every State and

10 Ibid.

11 Because of the objections to the absence of an explicit provision

saving the right to challenge prospective jurors in Article III of the

Constitution, the Sixth Amendment originally contained such a pro

vision when introduced in the House by James Madison. HELLER,

THE SIXTH AMENDMENT 24 (1951). This version provided that:

“The trial of all crimes . . . shall be by an impartial jury of

freeholders of the vicinage, with the requisite of unanimity

for conviction, of the right of challenge and other accus

tomed requisites . . . ” 1 ANNALS OF CONG. 435 (1789).

Largely at the insistence of the Senate, however, the Amendment was

altered to eliminate the specific references to the common law

features of a jury trial. HELLER, supra at 31-33. The reason for

these deletions is unclear because there is no record of the Senate

debates on the Sixth Amendment. Id. at 31. However, in two letters

to Edmund Pendleton, Madison wrote that the vicinage requirement

was the only feature of the common law jury that was specifically

objected to by the Senate. 1 LETTERS AND OTHER WRITINGS

OF JAMES MADISON 491, 492-93 (1865); see Williams v. Florida,

399 U.S. 78, 94-96 (1970). In the absence, therefore, of any con

crete evidence that the Senate opposed the right of challenge, its

deletion from the Amendment cannot be taken as an indication that

Congress did not intend the right of challenge to be part of the con

stitutional right to a jury trial. On the contrary, it is at least as likely

that the Senate’s action in streamlining the Madison version rested on

the “assumption that the most prominent features of the jury would

be preserved as a matter of course.” Williams v. Florida, supra, 399

U.S. at 123 n. 9 (Harlan, J. Concurring).

12 HELLER, THE SIXTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION

OF THE UNITED STATES 71 (1951); see Dennis v. United States,

339 U.S. 162 (1950); Pointer v. United States, 151 U.S. 396 (1894);

Lewis v. United States, 146 U.S. 370 (1892).

11

the District of Columbia,13 and is established practice in the

federal courts.14 The right of challenge for cause, therefore,

13 The right of challenge is guaranteed specifically by statute in

most states, and in other states by either court rule or decisional law.

See ALA. CODE, Tit. 15, §55 (1958); ALASKA STAT. §09.20.090

(1962); ARIZ. R. CRIM. P. 219 (1956); ARK. STAT. ANN. §43-1915

(1964); CAL PEN. CODE § 1066 (West’s 1970); Jones v. People, 23

Colo. 276, 47 Pac. 275 (1898); State v. Smith, 49 Conn. 376 (1881);

DEL. SUPER. CT. (CRIM.) R. 24 (1948); D.C. CODE GEN SESSIONS

CT. R. 24 (by inference) (1961); FLA. STAT. ANN. §913-02(2)

(1969); GA. CODE ANN. §59-804 (1965); HAWAII REV. STAT.

§635-28 (1968); IDAHO CODE ANN. §§19-2012, 2013, 2016

(1948); ILL. REV. STAT. ch. 38, § 1154 (1965); BURNS IND. STAT.

§9-1054 (by inference) (1956); IOWA CODE ANN. §§779.6 (1946);

KAN. STAT. §22-3410 (1971); KY. REV. STAT. R. CRIM. P.

§§9.36, 9.38 (1970); LA. CONST. ART. I §10; LA. STAT. ANN.

CODE CRIM. P. §797 (1967); ME. REV. STAT. ANN., tit. 15,

§1259 (1969); MD. ANN. CODE, tit. 51, §§10, 18 (1957; MASS.

ANN. LAWS ch. 234, §28 (1956); MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. §768.9

(1948); People v. Wheeler, 96 Mich. 1, 55 N.W. 371 (1893); MINN.

STAT. ANN. § 631.28 (1945); MISS CODE ANN. § 1802 (by inference)

(1942); MO. REV. STAT. §§546.120-546.160 (1959); MONT. REV.

CODE, tit. 95, §1909 (1947); NEB. REV. STAT. §29-2006 (by

inference (1964); NEV. REV. STAT., tit. 14, § 175.036 (1967); N.H.

REV. STAT. ANN., ch. 606, §3 (1955); N .J. STAT. ANN., tit.2A

§78-7 (1952); N. M. STAT. §19-1-14 (1953); N. Y. CRIM. PROC.

L. §270.20 (McKinney’s 1971); N. C. GEN. STAT. §9-15 (1969),

N. D. CENT. CODE §29-17-32 (1960); OHIO REV. CODE §2945.24

(by inference) (1971); OKLA. STAT. ANN. §656 (1969); ORE. REV.

STAT. §§ 17.165, 136.210 (1961); PA. STAT. tit. 19 §811 (1964);

R. I. GEN. LAWS §9-10-14 (1956); S. C. CODE OF LAWS §38-202

(1962); S.D. COMP. LAWS §§2343-28, 2343-29 (1967; TENN.

CODE §22-301 (1956); TEX. CODE CRIM. P. (Vernon’s Ann.) Art.

35.16 (1965); UTAH CODE §77-30-16 (1953); VT. ANN. STAT.,

tit. 12 § 1941 (1947); VA. CODE §§ 8-199, 19.1-206 (1960); WASH.

REV. CODE ANN. § 10.49. 040 (1961); W. VA. CODE § 62-34 (1966);

WIS. STAT. ANN. §§957.14, 290.16 (1957); WYO. STAT. §7-222

(1957); WYO. R. CRIM. P. 25 (1968). See ALI CODE OF

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE, 109-110, 822 (Official Draft 1931); ABA

PROJECT ON STANDARDS FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE, Trial by

Jury 67 (Approved Draft 1968).

14FED. R. CRIM. P. 24(a); see 2 WRIGHT, FEDERAL PRAC

TICE AND PROCEDURE 38 (1969).

12

is not only essential to the enforcement of the right to an

impartial jury, but it has an independent source in the

Sixth Amendment’s right to a jury trial.

In order to exercise effectively his constitutional right to

challenge for cause jurors who are prejudiced against him

by reason of his race or pretrial publicity, a criminal

defendant must be provided with some procedure for exam

ining prospective jurors with respect to their biases and pre

judices. As this Court has said, “ [p]reservation of the

opportunity to prove actual bias is a guarantee o f a defend

ant’s right to an impartial jury .” Dennis v. United States,

339 U.S. 162, 171-172 (1950). And the right of challenge

would indeed be a hollow guarantee unless the defendant

were “brought face to face in the presence of the court,

with each proposed juror, and an opportunity given for

such inspection and examination of him as is required for

the due administration of justice.” Pointer v. United States,

151 U.S. 196, 409 (1894).15

In the absence of a voir dire examination, the only

means that a defendant would have of discovering the exis

tence of grounds upon which he could exercise a challenge

for cause would be to investigate prospective jurors prior to

the commencement of the trial. But such a possibility does

not provide a realistic alternative to a voir dire examination.

Not only would such an investigation be unlikely to dis

close the biases and prejudices that a juror will only reveal

when he is put on oath and examined by the court or coun

sel, but there would be no way to lay the foundation for

the exercise of a challenge for such a cause without ques

tioning the juror himself. The practical impossibility, more

over, for a criminal defendant, who may be indigent, to

conduct an extensive investigation of a trial venire in the

15See also Morford v. United States, 339 U.S. 258, 259 (1950);

Aldridge v. United States, 283 U.S. 308 (1931); Brown v. United

States, 119 U.S. App. D.C. 203, 338 F.2d 543 (D.C. 1964); Bailey

v. United States, 53 F.2d 982, 984 (5th Cir. 1931), People v. Boul-

ware, 29 N.Y.2d 135, 324 N.Y.S.2d 30 (1971).

13

limited time between its publication and the time of trial

severely limits its usefulness.16 Finally, any procedure

which encouraged pretrial contact between a defendant

and prospective jurors might itself impair their impartiality

and be open to serious abuse.17 It is for these reasons

that a voir dire examination of prospective jurors in con

nection with the exercise of challenges for cause has been

widely recognized as the principal, if not the only, means

of selecting an impartial jury .18 The practice is deeply

rooted in the history of trial by jury,19 and is the right

of a criminal defendant in the fifty States, the District of

Columbia and the federal courts.20

16In the present case, the trial venire of 50 persons was not selected

and summoned until ten days before the term of court at which

petitioner was tried, in accordance with §38-61, S. C. CODE (1962)

(A. 28). There is, moreover, no requirement that the defendant be

provided with a list of the veniremen prior to the day of the trial.

See Stone v. United States, 324 F.2d 804 (5th Cir. 1963), cert, denied,

376 U.S. 938 (1964); Hamer v. United States, 259 F.2d 274 (9th Cir.

1958), cert, denied, 359 U.S. 196 (1959); cf. ABA PROJECT ON

STANDARDS FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE, Trial By Jury §2.3

(Approved Draft 1968).

17See Kiernan v. Van Schaik, 347 F.2d 775, 780 (3rd Cir. 1965)

(“The impartiality of jurors should be tested under the control of the

court rather than by the unsupervised activities of investigators with

all the undesirable possibilities of intimidation and jury tampering

which such surveillance inevitably presents.”)

18See Note, supra n. 5, 60 COLUM. L. REV. at 354; DEVLIN,

supra, n. 5, at 31-33.

19Blackstone described the practice at common law as follows:

“A juror may himself be examined on oath of voir dire,

veritatem dicere (to speak the truth) with regard to such

causes of challenge as are not to his dishonor or discredit;

but not with regard to any crime, or any thing which tends

to his disgrace or disadvantage.” 3 W. BLACKSTONE, COM

MENTARIES 363 (Cooley ed. 1899).

20The right to conduct a voir dire examination is guaranteed

specifically by statute in most states, and in other states by either

court rules or decisional law. See ALA. CODE, tit. 15, §52 (1958);

ALASKA STAT. §09.20.090 (1962); ARIZ. R. CRIM. P. 217 (1956);

14

By refusing to ask the questions proposed by petitioner,

the trial judge effectively denied petitioner any opportunity

to have the prospective jurors examined on voir dire with

respect to whether they were prejudiced against him.

ARK. STAT. ANN. §39-226 (1962); CAL. PEN. CODE §1078 (West

1969); Zancannelli v. People, 63 Colo. 252, 165 Pac. 612 (1917);

CONN. GEN. STAT. ANN. §51-240 (Cum. Supp. 1967); DEL. CODE

§ 11-3301 (1953); DEL. SUPER. CT. (CRIM.)R.24(1948); D.C. CODE

GEN. SESSIONS CT. R. 24 (1961); FLA. STAT. ANN. CRIM.

PRO. R. § 1.290 (1968); GA. CODE ANN. §59-806 (felony); Nobles

v. State, 127 Ga. 212, 56 S.E. 125 (1906) (misdemeanor); (1965);

FLAW All REV. STAT. §635-27 (1968); State v. Hoagland, 39 Idaho

405, 228 Pac. 314 (1924); ILL. REV, STAT. ch. 38, § 115-4(0

(1965); Epps v. State, 102 Ind. 539, 1 N.E. 491 (1885); State v.

Dooley, 89 Iowa 584, 57 N.W. 414 (1894); KAN. STAT. ANN.

§22-3408(3) (Cum. Supp. 1971); KY. REV. STAT. R. CRIM.

P. §9.38 (1970); LA. CONST. ART. I. § 10; LA. STAT. ANN. CODE

CRIM. P. § 786 (1967); ME. REV. STAT. ANN., tit. 15, § 1258

(1969); MD. ANN. CODE, Rule 745 (1971); MASS. ANN.

LAWS, ch. 234, § 28 (1956); MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. §768.8

(1948); People v. Wheeler, 96 Mich. 1, 55 N.W. 371 (1893); MINN.

STAT. ANN. §631.26 (1945); MISS. CODE ANN. § 1802 (1942); State

v. Mann, 83 Mo. 589 (1884); MONT. REV. CODE, tit. 95 §1909 (c)

(1947); NEB. REV. STAT. §29-2004 (1964); NEV. REV. STAT., tit.

14 §175.031 (1967); N. H. REV. STAT. ANN., ch. 500-A:32; 606:1,

(Cum. Supp. 1971); N. J. STAT. ANN. tit. 2A §78-4 (1952); N. M.

STAT. §21-1-1 (47a) (1953); N. Y. CRIM. PROC. L. §270.15

(McKinney’s 1971); N. C. GEN. STAT. §9-15 (1969); N. D. CENT.

CODE §29-17-28 (1960); OHIO REV. CODE §2945.27 (1971);

Roberson v. State, 456 P.2d 595 (Okla. Crim. 1968); ORE. REV.

STAT. §136.210 (1961); PA. STAT., tit. 19 §811 (1964); R.I. GEN.

LAWS § 9-10-14 (1956); S. C. CODE OF LAWS' § 38-202

(1962);State v. Gurrington, 11 S. D. 178, 76 N.W. 326 (1898);Ebwte

v State, 83 Tenn. 712 (1885); TEX. CODE CRIM. P. (Vernon’s

Ann.), Art. 35.17 (1965); State v. Morgan, 23 Utah 212, 64 Pac.

356 (1900); State v. Mercier, 98 Vt. 368, 127 Atl. 715 (1925); VA.

CODE §§8-199, 19.1-206 (1960); State v. Marfaudile, 48 Wash. 117,

92 Pac. 939 (1907); State v. Stonestreet, 112 W. Va. 668, 116 S.E.

378 (1932); WIS. STAT. ANN. §§957.14, 270.16 (1947); WYO STAT.

R. CRIM. P. 25 (1968). See ALI CODE OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE,

109-110, 822 (Official Draft 1931); ABA PROJECT ON STANDARDS

FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE, Trial by Jury 67 (Approved Draft

1968). FED. R. CRIM. P. 24 (a).

15

Clearly, the three general questions the judge put to the

jurors relating to their impartiality were inadequate to elicit

meaningful responses. It is widely recognized that the mere

statement by the juror in response to a general query that

he can be impartial is entitled to little weight. As one fed

eral court concluded:

“ [Mjerely going through the form of obtaining

juror’s assurances of impartiality is insufficient. . . .

[Wjhether a juror can render a verdict based solely

on evidence adduced in the courtroom should not

be adjudged on that juror’s own assessment o f self-

righteousness without something more” (Emphasis

in original).21

Calling for purely subjective responses to general questions

is ineffective to test impartiality, and “the defendant in a

criminal case has the ‘right to probe for the hidden preju

dices o f jurors’.”22

A specific inquiry into prejudices of the jurors resulting

from racial bias or pretrial publicity was particularly vital

under the circumstances of the present case. As noted by the

two dissenting Justices of the South Carolina Supreme

Court, petitioner is a “black, bearded, civil or human rights

activist” whose role as an SCLC worker had gained him noto

riety in Florence County (A. 71,73-74). The outcome of the

prosecution against him for the possession of marijuana de

pended solely upon weighing the credibility of a white police

officer who claimed that he had found the drug in petitioner’s

possession while searching him, and of petitioner who testi

fied that he did not have the marijuana in his possession and

that he was being “framed” by the authorities because of

his involvement in civil rights. The case was, moreover,

21 Silverthorne v. United States, 400 F.2d 627, 638-39 (9th Cir.

1968); see also United States v. Carter, 440 F.2d 1132, 1134 (6th

Cir. 1971).

22Silverthorne v. United States, supra, 400 F.2d at 640; see ABA

PROJECT ON STANDARDS FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE, supra, n.6,

at 130-134.

16

of unusual interest because of the recent concern and publi

city in Florence over a serious “drug problem” (A. 36).

Indeed, the police officer who was the State’s chief witness

had recently appeared on local television on a program

devoted to violation of the drug abuse laws (A. 36). Peti

tioner’s motions to quash the trial venire on the ground

that blacks had been systematically excluded and for a

change of venue or continuance on the ground of pretrial

publicity, furthermore, alerted the trial judge to the possi

bility that prospective jurors might be prejudiced against

him (A. 12, 15).

This Court has itself recognized that inquiries of the

nature sought by petitioner are essential to the guarantee of

an impartial trial. In Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 221

(1965), the Court noted that the influence of race on jurors

is widely explored during voir dire and “that the fairness of

trial by jury requires no less.” And in Aldridge v. United

States, 382 U.S. 308, 310 (1931), this Court reversed a con

viction on the ground that the refusal of a federal trial

judge to ask prospective jurors a question relative to racial

prejudice in a case o f a black defendant who was charged

with shooting a white policeman violated “ the essential

demands of fairness.” Federal courts have consistently held

that a criminal defendant has a right to examine jurors

specifically with respect to racial prejudice,23 and such ques

tions have been widely approved by state courts.24

23United States v. Carter, 440 F.2d 1132 (6th Cir. 1971); United

States v. Gore, 435 F.2d 1110 (4th Cir. 1970); King v. United States,

362 F.2d 968 (D.C. Cir. 1966); Frasier v. United States, 267 F.2d

62 (1st Cir. 1959); Smith v. United States, 262 F.2d 50 (4th Cir.—

1959); United States v. Dennis, 183 F.2d 201, 227, n. 35 (2d Cir.),

a ff’d 341 U.S. 494 (1951).

24Gholston v. State, 221 Ala. 556, 130 So. 69 (1930); State v.

Higgs, 143 Conn. 138, 120 A.2d 152 (1956); Finder v. State, 27

Ha. 370, 8 So. 837 (1891); Herndon v. State, 178 Ga. 832, 174

S.E. 597 (1934); State v. Jones, 175 La. 1014, 144 So. 899 (1932);

Giles v. State, 229 Md. 370, 183 A.2d 359 (1962); Owens v. State,

111 Miss. 488, 171 So. 345 (1930); State v. Pyle, 343 Mo. 876, 123

S.W.2d 166 (1938); Johnson v. State, 88 Neb. 565, 130 N.W. 282

17

The right to conduct an inquiry into whether the jurors

have been prejudiced by pretrial publicity is implicit in the

decisions of this Court. Irvin v. Dowd, supra; Rideau v.

Louisiana, supra-, Sheppard v. Maxwell, supra. Unless there

had been such a voir dire examination in these cases, this

Court would have been completely unable to assess the

impact of the pretrial publicity on the impartiality of the

jurors. And a defendant who has a right to a hearing to

show that he is entitled to a change of venue because of

pretrial publicity surely must also be entitled to show that

a particular juror is not impartial for the same reason.

Groppi v. Wisconsin, supra,25

In affirming petitioner’s conviction, the South Carolina

Supreme Court held that the trial judge did not abuse his

discretion in refusing to examine the jurors as requested in

view of the fact that petitioner “ failed to carry the burden

of showing that [the] questions should have been asked to

assure a fair and impartial jury” (A. 102).26 But the judge

was fully aware of petitioner’s race, the nature of the pros

ecution, the existence of pretrial publicity, and the pro

posed questions were reasonably designed to disclose the

prejudices o f jurors.27 Under the circumstances, the limita

(1911); People v. Decker, 157 N.Y. 186, 51 N.E. 1018 (1898); State

v. McAfee, 64 N.C. 339 (1870); Fendrick v. State, 39 Tex. Cr. 147,

45 S.W. 589 (1898).

25 See ABA PROJECT STANDARDS FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE,

supra, n. 6 at 130-135; Silverthorne v. United States, supra; Marson

v. United States, 203 F.2d 904 (6th Cir. 1953).

26The court did not indicate what kind of a showing a defendant

must make before being permitted to make inquiries with respect to

race or pretrial publicity. Although it is clear under South Carolina

law that in examining prospective jurors on voir dire it is within the

discretion of the trial judge to go beyond the questions that are

required by § 38-202 S. C. CODE (1962), State v. Peterson, 255 S. C.

579, 180 S.Ed.2d 341 (1871); State v. Britt, 237 S. C. 293, 117

S.Ed. 379 (1960), the cases do not establish any standards for the

exercise of that discretion.

27See United States v. Gore, 435 F.2d 1110 (4th Cir. 1970). In

this case, the Fourth Circuit rejected the argument that this Court’s

18

tion o f the voir dire examination by the court deprived

petitioner of the only means by which he could enforce his

constitutional right to challenge for cause jurors who were

not impartial towards him. Although the extent of exami

nation to which a defendant is entitled and the manner in

which it is to be conducted, i.e., by court, counsel or both,

must fee necessarily be left largely to the discretion of the

trial judge depending on the circumstances of the particular

case,28 petitioner submits that minimal constitutional stan

dards for the effective exercise of his right to an impartial

jury required the trial judge to have permitted him some

opportunity to probe for prejudice resulting from racial

bias or pretrial publicity.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, petitioner’s conviction violated

his right to be tried by an impartial jury, guaranteed by the

Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States

decision in Aldridge v. United States, supra, should be limited to

cases of interracial violence. The court held that the refusal to ask

questions concerning racial bias could not be considered harmless

error where, as in the present case, the defendant was black, the

government’s witnesses were white, and the outcome depended on

weighing credibility. Id. at 1112.

28See ABA PROJECT ON STANDARDS FOR CRIMINAL JUS

TICE, Trial by Jury, §2.4 (Supp. 1968), giving the judge primary

responsibility to conduct a voir dire examination but authorizing him

to “permit such additional questions by the defendant or his attorney

and the prosecuting attorney as he deems reasonable or proper.”

Since counsel for petitioner did not seek to conduct the voir dire

examination himself, this case raises no issue as to who should con

duct the interrogation. Similarly, as the dissenting judges on the

South Carolina Supreme Court recognized, the only question here

is whether any inquiry into racial prejudice or the effect of pretrial

publicity should be permitted, and not the extent of such inquiry.

19

Constitution. The judgment of the Supreme Court of

South Carolina should be reversed and the case remanded

for a new trial.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, til

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

MORDECAI C. JOHNSON

JOHN A. GAINES

P.O. Box 743

Florence, South Carolina

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioner