Chisom v. Roemer Joint Appendix

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Chisom v. Roemer Joint Appendix, 1991. 4fdd427a-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dbd3ed5f-7bee-4801-8f81-67ca6c1ae66f/chisom-v-roemer-joint-appendix. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

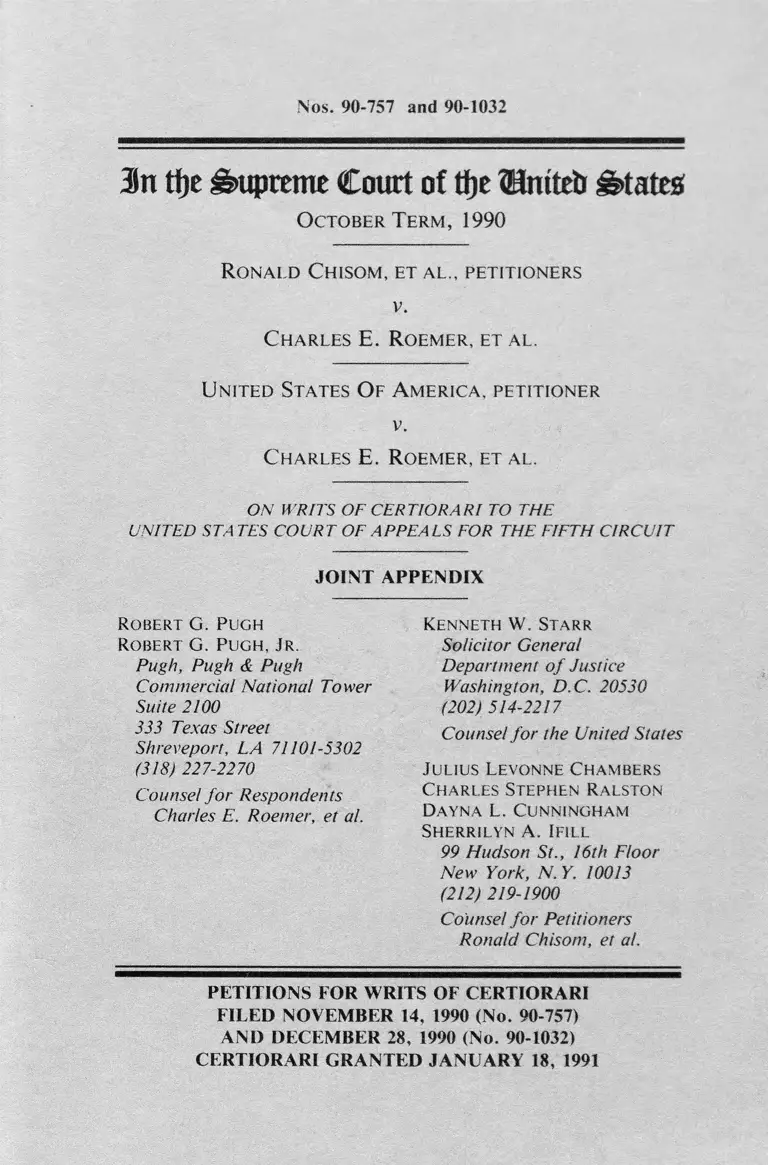

Nos. 90-757 and 90-1032

3n tf)e Supreme Court of tfje Untteb Stalest

O ctober T e r m , 1990

Ro nald C h isom , et a l ., petitioners

v.

C harles E . R o em er , et a l .

U nited States O f A m er ic a , petition er

v.

C harles E . R o em er , et a l .

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STA TES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

JOINT APPENDIX

Kenneth W .Starr

Solicitor General

Department o f Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 514-2217

Counsel for the United States

Julius Levonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Dayna L. Cunningham

Sherrilyn A. I fill

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, N. Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel fo r Petitioners

Ronald Chisom, et al.

PETITIONS FOR WRITS OF CERTIORARI

FILED NOVEMBER 14, 1990 (No. 90-757)

AND DECEMBER 28, 1990 (No. 90-1032)

CERTIORARI GRANTED JANUARY 18, 1991

Robert G. Pugh

Robert G. Pugh, J r.

Pugh, Pugh & Pugh

Commercial National Tower

Suite 2100

333 Texas Street

Shreveport, LA 71101-5302

(318) 227-2270

Counsel for Respondents

Charles E. Roemer, et al.

3 n tf)c Suprem e C o u rt o f tfje Mmtetr States;

O ctober T e r m , 1990

No. 90-757

R onald C h iso m , et a l ., petition ers

v.

C harles E . R o em er , et a l .

No. 90-1032

U nited States O f A m erica , petition er

v.

C harles E . R o em er , et a l .

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STA TES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

CONTENTS OF JOINT APPENDIX*

1. District Court Docket Entries................. 1

2. Court of Appeals Docket Entries,

No. 87-3463 ................................................ 3

3. Court of Appeals Docket Entries,

No. 89-3654 ................. ........................... . 4

4. Plaintiffs Amended Complaint, filed Sept.

30,1986............................................... 5

5. District Court decision of May 1, 1987, as

amended, dismissing the complaint......... 12

6. Court of Appeals decision of February 29,

1988 .............................................................. 26

(i)

11

CONTENTS —Continued: Page

7. Complaint in Intervention of United States,

filed August 4, 1988 ..................................... 45

8. Answer of defendants, filed August 15, 1988 . 51

9. Answer of defendants to United States Com

plaint filed April 4, 1989 ............................. 60

10. Order granting certiorari in No. 90-757.......... 63

11. Order granting certiorari in No. 90-1032........ 64 *

* The November 2, 1990, opinion of the court of appeals and the

September 13, 1989, opinion of the district court are printed in the ap

pendix to the petition for writ of certiorari filed in 90-757 and have not

been reproduced herein.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

No. 86-4075

R onald C hisom and U nited States

v.

C harles E . R o em er , et a l .

RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

DATE FILED DOCUMENT

9/19/86 Complaint.

* * *

9/30/86 Pltf’s amended complt.

* * *

5/1/87 OPINION that defts’ mtn to dismiss for fail

ure to state a claim upon which relief can be

granted is granted; unless pltfs’ complt is

amended w/in 10 days of entry of this opin

ion clerk of Court is directed to enter judg

dismissing pltfs’ claim at their costs.

* * *

5/7/87 Pltfs NOTICE OF APPEAL to 5 th Circuit

from judg of 5/1/87 granting deft’s mtn to

dismiss.

* * *

( 1)

2

DATE FILED

5/31/88

8/ 8/88

8/15/88

4/4/89

4/5/89

9/13/89

9/14/89

9/15/89

11/13/89

DOCUMENT

JUDGMENT FROM 5TH CIRCUIT — OR

DERED that judg of D.C. is REVERSED &

case is REMANDED to D.C. for further

proceedings. (Brown, Johnson & Higgin

botham) issd as mandate 5/27/88.

4c 4c %

INTERVENTION OF U.S.A.

ANSWER of defts to pltfs’ complt.

* ❖ *

ANSWER of defts to intervention.

4s 4c 4«

NON JURY TRIAL dktd 4/6/89.

4c 4c 4c

OPINION —Clerk is directed to enter judg

in favor of defts dismissing pltfs claims.

(CSjr) dltd 9/13/89.

JUDGMENT is ORDERED in favor of all

defts & agst all pltfs & U.S.A. as intervenor,

dismissing suit w/prj, pltfs to bear all costs.

9/13/89 dktd 9/14/89.

* * *

Pltfs’ notice o f appeal from final judgment

entered on 9/13/89.

4c 4c 4«

Notice o f appeal by U.S.A. from judg en

tered 9/14/89.

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

R onald C h iso m , et a l .

v.

E dw in E dw ards , et a l .

RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

DATE FILED DOCUMENT

%

2/29/88 Opinion rendered.

4

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-3654

R onald C hisom and U nited States

v.

C harles E. R o em er , et a l .

RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

DATE FILED DOCUMENT

❖ * *

11/02/90 Opinion rendered —remanded.

* * *

5

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

CIVIL ACTION NUMBER 86-4075

R onald C h iso m , M arie Bookm an , W alter W illa r d ,

M arc M o r ia l , L ouisiana Voter R eg istra tio n /

E ducation C rusa de , and H enry A. D illo n , III

PLAINTIFFS

versus

E dwin E dw ards , in his capa city as G overnor of

th e State of L o uisia n a ; J ames H . Brow n , in his

capacity as Secretary o f th e State of L o u isia n a ; and

J erry M. F o w ler , in his capa city as C omm issioner

of E lections of th e State of L ouisiana

defendants

Section A

Magistrate 6

CLASS ACTION

THREE JUDGE COURT

AMENDED COMPLAINT

I. PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This action is brought by the plaintiffs on behalf of all

black registered voters in Orleans parish to challenge the

election of Justices to the Louisiana Supreme Court from

the New Orleans area. Plaintiffs contend that the present

system of electing judges, whereby the parish of Orleans,

St. Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson elect two Justices

to the Louisiana Supreme Court at-large, is a violation of

6

II. JURISDICTION

This is an action for declaratory and injunctive relief

brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. Section 1973 and 42 U.S.C.

Section 1983. This Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28

U.S.C. Section 1331 and Section 1343 as well as 42 U.S.C.

Section 1973.

Plaintiffs also seek declaratory and other appropriate

relief pursuant to 28 U.S.C. Sections 2201 and 2202.

Plaintiffs’ claims under the Voting Rights Act and under

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S.

Constitution must be determined by a district court of

three judges pursuant to 28 U.S.C. Sect. 2284 (a).

III. PARTIES

The individual plaintiffs are all black registered voters

in Orleans parish. The organizational plaintiff is a non

profit corporation comprised of Orleans Parish black reg

istered voters active in voting rights issues. The plaintiffs

sue on behalf of themselves and all other black registered

voters in Orleans parish.

Edwin Edwards is Governor of the State of Louisiana.

Fie is sued in his official capacity of Governor. Mr. Ed

wards has the duty to support the Constitution and laws of

the State of Louisiana and of the United States and to see

that these laws are faithfully executed.

James H. Brown is Secretary of the State of Louisiana.

He is sued in that official capacity. As Secretary of State,

Mr. Brown has the duty to prepare and certify the ballots

for all elections, promulgate all election returns and ad

minister the election laws of Louisiana.

Jerry M. Fowler is Commissioner of Elections of the

State of Louisiana. He is sued in that official capacity. As

the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. Section

1973 because it dilutes the voting strengths of plaintiffs.

7

IV. CLASS ACTION ALLEGATIONS

This matter is brought as a class action pursuant to Rule

23(b)(2) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, on behalf

of all black persons who are residents and registered voters

of Orlean parish, State of Louisiana.

The number of persons who would be included in the

above-defined class would be approximately 135,000.

Plaintiffs are adequate representatives of the class in

that they are similarly situated with the rest of the mem

bers of the class. There are no actual or potential conflicts

of interest and the attorneys for plaintiffs are competent

and able to handle the litigation.

The questions of law and fact common to the class are

those implicit in this complaint including whether the

defendants should be ordered to comply with the Voting

Rights Act in the election of Justices to the Louisiana Su

preme Court from the New Orleans area.

V. FACTS

The State of Louisiana elects seven Justices to the Lou

isiana Supreme Court.

The method of electing Justices to the Louisiana

Supreme Court is set out at Louisiana Revised Statute

13:101. This statute orders that the state be divided into six

Supreme Court districts which elect seven Justices. Each

of the Supreme Court districts elects one Justice, except

for the First Supreme Court district which elects two Jus

tices at-large.

The First Supreme Court district is made up of the par

ishes of Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jeffer

son, from which two Justices are elected at-large.

Commissioner of Elections, he has the duty to work closely

with the office of the Secretary of State to prepare and cer

tify the ballots for all elections held in Louisiana.

8

The First District is the only Supreme Court district in

Louisiana that is not a single member district.

The First Supreme Court District of Louisiana contains

approximately 1,102,253 residents of which 63.36% or

698,418 are white and 379,101 or 34.4% are black. The

voter registration data for the First Supreme Court Dis

trict of Louisiana indicates a total registered voter popula

tion of 515,103. Of this total, 350,213 or 68% are white

and 162,810 or 31.61% are black.

If the First Supreme Court District of Louisiana were

divided into two single member districts, the average pop

ulation would be approximately 551,126 persons in each

district. Because Orleans parish’s present population is

555,515, the most logical division of the district into two

single member districts would have Orleans parish electing

one Supreme Court Justice and the parishes of Jefferson,

St. Bernard, and Plaquemines together electing the other

Supreme Court Justice.

If the present First Supreme Court District was divided

as indicated in the preceding paragraph, the Orleans par

ish district would have a black population and voter regis

tration majority. The Orleans parish district would have

236,987 white residents or 42.5% and 308,149 black resi

dents or 55.3%. The voter registration figures indicate

that the district would have 124,881 white voters or 47.9%

and 134,492 black voters or 51.6%.

The Supreme Court district which would be comprised

of Jefferson, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard would have a

total population of 544,738 of which 461,431 or 84.7%

would be white and 70,952 black residents or 13.0%. The

voter registration data indicates that 225,332 registered

voters are white or 88.5% while 28,318 black voters are

also registered or 11.1%.

9

Because of the official history of racial discrimination in

Louisiana’s First Supreme Court District, the wide spread

prevalence of racially polarized voting in the district, the

continuing effects of past discrimination on the plaintiffs,

the small percentage of minorities elected to public office

in the area, the absence of any blacks elected to the Louisi

ana Supreme Court from the First District, and the lack of

any justifiable reason to continue the practice of electing

two Justices at-large from the New Orleans area only,

plaintiffs contend that the current election procedures for

selecting Supreme Court Justices from the New Orleans

area dilutes minority voting strength and therefore violates

the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as amended.

VI. CAUSES OF ACTION

The defendants are in violation of Section 2 of the 1965

Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 USC Section 1973 be

cause the present method of electing two Justices to the

Louisiana Supreme Court at-large from the New Orleans

area impermissibly dilutes minority voting strength.

The defendant’s actions are in violation of the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution and 42 USC Section 1983 in that the purpose

and effect of their actions is to dilute, minimize, and

cancel the voting strength of plaintiffs.

VII. EQUITY

This action is an actual controversy between parties hav

ing adverse legal interests of such immediacy and reality as

to warrant a declaratory judgment.

Plaintiffs have no adequate remedy at law and will suf

fer irreparable injury unless injunctive relief is issued.

10

VIII. PRAYER

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray for relief as follows:

1. That a District Court of three judges be convened

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. Sect. 2284 and 42 U.S.C. Sect. 1973

to adjudicate this matter;

2. That this matter be certified as a class action;

3. That a preliminary and permanent injunction issue

against the defendants as follows:

a. Restraining defendants from allowing any further

elections of Justices from the First Supreme Court District

in accordance with Louisiana Revised Statute 13:101 Sub

section 1 until this court makes a decision on the merits of

plaintiffs challenge;

b. Ordering the defendants to reapportion the First

Louisiana Supreme Court District in a way that fairly rec

ognizes the voting strength of minorities in the New Or

leans area and completely remedies the present dilution of

minority voting strength.

c. Ordering the defendants to comply with the 1965

Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 USC Section 1973;

4. That this court declare and determine that the pres

ent system of electing two Justices at-large from the par

ishes of Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaquemines, and Jefferson

pursuant to Louisiana Revised Statute 13:101 Sub-section

1 impermissibly dilutes minority voting strength and

violates the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as amended, and also

violates the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution.

5. That attorney fees be awarded to plaintiffs;

11

Respectfully submitted,

/s / W illiam P. Q uigley

William P. Quigley

631 St. Charles Ave.

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

6. That there be other such relief as may be necessary

and proper.

Ron Wilson

Richards Building

Suite 310

837 Gravier St.

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

12

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

Civil Action No. 86-4075

R o nald C h iso m , et al

versus

E dw in E dw ards, et al

Section: “A”

AMENDED OPINION

This matter is before the Court on defendants’ motion

to dismiss for failure to state a claim upon which relief can

be granted pursuant to F.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(6). For the fore

going reasons, defendants’ motion is GRANTED.

FACTS AND ALLEGATIONS

Ronald Chisom, four other black plaintiffs and the

Louisiana Voter Registration Education Crusade filed this

class action suit on behalf of all blacks registered to vote in

Orleans Parish. Plaintiffs’ complaint challenges the pro

cess of electing Louisiana Supreme Court Justices from

the First District of the State Supreme Court. The com

plaint alleges that the system of electing two at-large

Supreme Court Justices from the Parishes of Orleans, St.

Bernard, Plaquemines and Jefferson violates the 1965

Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the United States

Federal Constitution and, finally, 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

Plaintiffs argue that the election system impermissibly

dilutes, minimizes and cancels the voting strength of

blacks who are registered to vote in Orleans Parish.

13

More specifically, plaintiffs’ original and amended com

plaint avers that the First Supreme Court District of Loui

siana contains approximately 1,102,253 residents of which

63.36%, or 698,418 are white, and 379,101, or 34.4% are

black. The First Supreme Court District has 515,103 reg

istered voters, of which 68% are white, and 31.61% are

black. Plaintiffs contend that the First Supreme Court

District of Louisiana should be divided into two single dis

tricts. Plaintiffs suggest that because Orleans Parish’s

present population is 555,515 persons, roughly half the

present First Supreme Court District, the most logical divi

sion is to have Orleans Parish elect one Supreme Court

Justice and the Parishes of Jefferson, St. Bernard and

Plaquemine together elect the other Supreme Court Jus

tice. If plaintiffs’ plan were to be carried out, plaintiffs

contend the present First Supreme Court District encom

passing only Orleans Parish would then have a black pop

ulation and voter registration comprising a majority of the

district’s population. More specifically, plaintiffs assert

presently 124,881 of the registered voters in Orleans are

white, comprising 47.9% of the plaintiffs’ proposed dis

trict’s voters; while 134,492 of the registered voters in

Orleans are now black, comprising 51.6% of the envi

sioned district’s voters. The other district comprised of

Jefferson, Plaquemines and St. Bernard Parishes and

would have a substantially greater white population than

black, according to plaintiffs’ plan.

Plaintiffs seek class certification of approximately

135,000 black residents of Orleans Parish, whom plaintiffs

allege suffer from diluted voting strength as a result of the

present at-large election system. Additionally, plaintiffs

seek a preliminary and permanent injunction against the

defendants restraining the further election of Justices for

the First Supreme Court District until this Court makes a

determination on the merits of plaintiffs’ challenge. Fur

14

ther, plaintiffs seek an order requiring defendants to re

apportion the First Louisiana Supreme Court in a manner

which “fairly recognizes the voting strengths of minori

ties in the New Orleans area and completely remedies the

present dilution of minority voting strength.” (Plaintiffs’

Complaint, p. 7). Plaintiffs also seek an order requiring

compliance with the Voting Rights Act and, finally, a dec

laration from this Court that the Supreme Court election

system violates the Voting Rights Act and the fourteenth

and fifteenth amendments to the Federal Constitution.1

Defendants do not dispute the figures presented by

plaintiffs in their amended complaint. Instead, they con

tend that section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended, the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the

United States Federal Constitution and 42 U.S.C. § 1983

fail to provide plaintiffs grounds upon which relief can be

granted for plaintiffs’ allegation of diluted black voting

strength.

SECTION 2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT OF 1965

DOES NOT APPLY TO THE INSTANT ACTION

Prior to 1982, section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (42

U.S.C. § 1973), “Denial or Abridgement of Rights to Vote

on Account of Race or Color Through Voting Qualifica

tions or Prerequisites,” read as follows:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or

standard, practice, or procedure, shall be imposed or 1

1 Plaintiffs, earlier, sought a three judge court to hear this com

plaint which was denied by this Court as the terms of 28 U.S.C. § 2284

provide for a three judge court when the constitutionality of the ap

portionment of congressional districts or the apportionment of any

statewide legislative body is challenged. Nowhere does § 2284 provide

for convening a three judge court when a judicial apportionment is

challenged.

15

applied by any State or political subdivision to deny

or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States

to vote on account of race or color, or in contraven

tion of the guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2)

of this title.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act was amended as a

response to City o f Mobile, Alabama v. Bolden, 446 U.S.

55, 100 S.Ct. 1490, 64 L.Ed. 47 (1980), in which the Su

preme Court in a plurality opinion held to establish a

violation of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, minority

voters must prove the contested electoral mechanism was

intentionally adopted or maintained by state officials for a

discriminatory purpose. After Bolden, Congress in 1982

revised section 2 to make clear that a violation of the

Voting Rights Act could be proven by showing a discrimi

natory effect or result alone. United States v. Marengo

County Commission, 731 F.2d 1546 n.l (11th Cir. 1984),

appeal dismissed, cert, denied, 105 S.Ct. 375, 83 L.Ed.2d

311. (1984)2 Section 2, as amended, 96 Stat. 134, now

reads:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be im

posed or applied by any State or political subdivision

in a manner which results in a denial or abridgement

of the rights of any citizen of the United States to vote

on account of race or color, or in contravention of the

guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2), as pro

vided in subsection (b) of this section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established if,

based on the totality of the circumstances, it is shown

2 See S.Rep. 97-417, 97 Cong.2d Sess (1982) pp. 15-43 for a com

plete discussion of Congress’ intent to overturn the section 2 “pur

poseful discrimination” requirement imposed by Mobile v. Bolden.

16

that the political processes leading to nomination for

election in the State or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by members of a class of

citizens protected by subsection (a) of this section in

that its members have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the politi

cal process and to elect representatives o f their choice.

The extent to which members of a protected class

have been elected to office in the State or political

subdivision is one circumstance which may be consid

ered: Provided, that nothing in this section establishes

a right to have members of a protective class elected

in numbers equal to their proportion in the popula

tion. 42 U.S.C. § 1973 (emphasis added).

Prior to the 1982 amendments to section 2, a three-

judge court composed of Judges Ainsworth, West and

Gordon, headed by Judge West, addressed a voting rights

claim arsingfs/c] out of the same claims of discrimination

as in this case, albeit not in a section 2 context. Wells v.

Edwards, 347 F.Supp 453 (M.D. La. 1972), affd, 409

U.S. 1095, 93 S.Ct. 904, 34 L.Ed.2d 679 (1973). In Wells,

a registered black voter residing in Jefferson Parish,

brought suit seeking a reapportionment of the judicial

districts from which the seven judges of the Supreme

Court of Louisiana are elected. Ms. Wells sought an in

junction enjoining the state from holding the scheduled

Supreme Court Justice elections and an order compelling

the Louisiana Legislature to enact an apportionment plan

in accordance with the “one man, one vote” principle and

to reschedule the pending election. On cross motions for

summary judgment, the three-judge court stated, “We

hold that the concept of one-man, one vote apportionment

does not apply to the judicial branch of government.” 342

F. Supp. at 454. The Wells court took notice of Hadley v.

Junior College District, 397 U.S. 50, 90 S.Ct. 791, 25

17

L.Ed.2d 45 (1970), in which the Supreme Court held,

“Whenever a state or local government decides to select

persons by popular election to perform governmental

functions, the equal protection clause of the fourteenth

amendment requires that each qualified voter must be

given an equal opportunity to participate in that election

. . . 90 S. Ct. 791, 795 (emphasis added), but

distinguished its holding by outlining the special functions

of judges.

The Wells court noted many courts’ past delineations

between elected officials who performed legislative or

executive functions and judges who apply, but not create,

law3 and concluded:

‘Judges do not represent people, they serve people.’

Thus, the rationale behind the one-man, one-vote

principle, which evolved out of efforts to preserve a

truly representative form of government, is simply

not relevant to the makeup of the judiciary.

347 F. Supp. at 455.

The Wells opinion interpreted the “one man one vote”

principle prior to the 1982 amendments to section 2, which

added the phrase, “[T]o elect representatives of their

choice.” 4 {See emphasis in quotation 42 U.S.C. 1973,

3 See, e.g., Stokes v. Fortson, 234 F. Supp. 575 (N.D. Ga. 1964)

(“Manifestly, judges and prosecutors are not representative in the

same sense as they are legislators or the executive. Their function is to

administer the law, not to espouse a cause of a particular

constituency”); Holshouser v. Scott, 335 F. Supp. 928 (D.D.C. 1971)

(“We hold that the one man, one vote rule does not apply to state

judiciary. . . .”); Buchanan v. Rhodes, 294 F. Supp. 860 (N.D. Ohio

1966) (“Judges do not represent people, they serve people”); New

York State Assn, o f Trial Lawyers v. Rockefeller, 267 F. Supp. 148,

153 (S.D. N.Y. 1967) (“The state judiciary, unlike the legislature, is

not the organ responsible for achieving representative government.”)

4 This language did not appear in section 2 at the time of the Wells

opinion.

18

supra.) The legislative history of the 1982 Voting Rights

Act amendments does not yield a definitive statement

noting why the word “representative” was added to section

2. However, in this case, no such statement is necessary, as

“to elect representatives of their choice” is clear and unam

biguous.

Judges, by their very definition, do not represent voters

but are “appointed [or elected] to preside and to admin

ister the law.” Black’s Law Dictionary, 1968. As

statements by Hamilton in the Federalist, No. 78 reflect,

the distinction between Judge and representative has long

been established in American legal history:

If it be said that the legislative body are themselves

the constitutional judges of their own powers, and

that the construction they put upon them is conclusive

upon the other departments, it may be answered, that

this cannot be the natural presumption, where it is not

to be collected from any particular provisions in the

constitution. It is not otherwise to be supposed that

the constitution could intend to enable the representa

tives of the people to substitute their will to that of

their constituents. It is far more rational to suppose

that the courts were designed to be an intermediate

body between the people and the legislature, in order,

among other things, to keep the latter within the

limits assigned to their authority. The interpretation

of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the

courts. . . .

Indeed, our Federal Constitution recognizes the in

herent difference between representatives and judges by

placing the federal judiciary in an entirely different cate

gory from that of other federal elective offices. It is note

worthy that articles 1 and 2, which establish Congress and

the Presidency, are lengthy and detailed, while Article 3,

19

which establishes the judiciary, is brief and free of direc

tion, indicating the judiciary is to be free of any instruc

tions. Today, Fifth Circuit jurisprudence continues to rec

ognize the long established distinction between judges and

other officials. See, e.g., Mortal v. Judiciary Committee

o f State o f Louisiana, 565 F.2d 295 (5th Cir. 1977) en

banc, cert, denied, 435 U.S. 1013, 98 S.Ct. 1887 (1978).

(See also Footnote 1, supra.)

The legislative history of the Voting Rights Act Amend

ments does not address the issue of section 2 applying to

the judiciary,* 5 indeed, most of the discussion concerning

the application of the Voting Rights Act refers to legisla

5 The Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee

on the Constitution, Senator Orrin Hatch, in voicing his strong oppo

sition of the Legislative reversal of Bolden through the section 2 revi

sions, made a brief reference to section 2 applying to judicial elections:

Every political subdivision in the United States would be liable to

have its electoral practices and procedures evaluated by the pro

posed results test of section 2. It is important to emphasize at the

onset that for the purposes of Section 2, the term “political subdi

vision” encompasses all governmental units, including city and

county councils, school boards, judicial districts, utility districts,

as well as state legislatures.

S. Rep. 97-417, 97 Cong. 2d Sess. 127, 151, reprinted in in 1982 U.S.

Code Cong. & Admin. News 298, 323.

Although Senator Hatch’s comment indicates coverage of judicial

districts by the Voting Rights Act, the purpose of the above passage

was to illustrate Senator Hatch’s belief that the impact of the section 2

Amendments’ “results test” would be far ranging and in his opinion,

detrimental. Senator Hatch’s comments were included at the end of

the Senate report usually reserved for dissenting Senators. The above

passage did not portend to be a definative or even a moderately de

tailed description of the coverage of the Voting Rights Act, nor does

Senator Hatch provide any authority for his suggestion of the poten

tial scope of section 2. Rather, this Court finds that the passage was

meant to be argumentative and persuasive, and not as a means to

define actual scope of the Act.

20

tive offices. Nevertheless plaintiffs ignore the historical

distinction between representative and judge and the lack

of any discernible legislative history in their favor and

argue that the Voting Rights Act is a broad and remedial

measure which must be extended to cover judicial election

systems..6 Plaintiffs rely principally on Haith v. Martin,

618 F. Supp. 410 (D.N.C. 1985) (three-judge court), a ff’d,

without opinion, 106 S.Ct. 3268, 93 L.Ed.2d 559 (1986)

for the proposition that the Court should ignore Wells v.

Edwards, supra, and apply section 2 to the allegations

contained in their complaint.7 In Haith, the district court

held that judicial election systems are covered by section 5

of the Voting Rights Act, which requires preclearance by

the U.S. Justice Department of any voting procedures

changes in areas with a history of voting discrimination.

Plaintiffs, in essence, argue that because the Supreme

Court, without opinion, affirmed the Haith district court

in its application of section 5 to judicial elections, this

Court should expand the holding of Haith to include sec

tion 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Plaintiffs’ argument fails

because section 5 does not specifically restrict its applica

6 See e.g., United Jewish Organization o f Williamsburg, Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 97 S.Ct. 996, 51 L.Ed.2d 229 (1977) (“It is ap

parent from the face of the Act, from its legislative history, and from

our cases of the Act itself was broadly remedial in the sense that it ‘was

designed by Congress to banish the blight of racial discrimination in

voting . . .’ ”), 130 U.S. at 156; South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383

U.S. 301, 86 S.Ct. 803 (1966) (The Voting Rights Act “reflects Con

gress’ firm intention to rid the country of racial discrimination in

voting”), 383 U.S. at 315.

7 Plaintiffs also rely on Kirksey v. Allain, Civ. Act. No.

J85-0960(B), slip op. (S.D. MS. April 1, 1987), in which a district

court dismissed the reasoning in Wells, and held section 2 does apply

to the elected judiciary. Wells, supra, has precedential authority and

clearly conflicts with Kirksey, an untested lower court opinion.

21

tion to election systems pertaining to representatives, a re

striction included in the 1982 amendments to section 2.

Although a potential conflict may develop between the

holdings in Wells and Haith, Wells clearly states the “one

man one vote” principle is not applicable to judicial elec

tions. This Court recognizes the long standing principle

that the judiciary, on all levels, exists to interpret and ap

ply the laws, that is, judge the applicability of laws in spe

cific instances. Representatives of the people, on the other

hand, write laws to encompass a wide range of situations.

Therefore, decisions by representatives must occur in an

environment which takes into account public opinion so

that laws promulgated reflect the values of the represented

society, as a whole. Judicial decisions which involve the in

dividual or individuals must occur in an environment of

impartiality so that courts render judgments which reflect

the particular facts and circumstances of distinct cases,

and not the sweeping and sometimes undisciplined winds

of public opinion.

PLAINTIFFS’ FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT

CLAIMS FAIL TO STATE A CLAIM UPON WHICH RELIEF

CAN BE GRANTED AS PLAINTIFFS DO NOT PLEAD

DISCRIMINATORY INTENT

The appropriate constitutional standard for establishing

a violation of the fourteenth amendment in the context of

voting rights is “purposeful discrimination.” Village o f

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., 429

U.S. 252, 97 S.Ct. 555, 50 L.Ed.2d 450 (1977); 8 -

McMillian v. Escambia City, Fla, 688 F.2d 960 (5th Cir.

8 In Village o f Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp.,

purposeful discrimination was held the standard necessary to establish

a violation of the fourteenth amendment where plaintiff claimed a vil

lage rezoning decision was racially discriminatory.

22

1982).9 Similarly, City o f Mobile, Alabama v. Bolden,

supra, requires a court to establish a finding of discrimina

tory purpose before declaring a fifteenth amendment vio

lation of voting rights.10

In Voter Information Project, 612 F.2d 208 (5th Cir.

1980), a panel composed of Judges Jones, Brown and

Rubin (opinion by Judge Brown) held a suit that alleged

the at-large scheme for electing city judges in Baton Rouge

invidiously diluted the voting strength of black persons in

violation of the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to

the United States Federal Constitution, and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983, could not be dismissed when the complaint alleges

purposeful discrimination. At the trial level, Judge West

relied on his reasoning in Wells, supra, that the one man,

9 In McMillian v. Escambia City, Fla., the Fifth Circuit held the

Arlington Heights’ “purposeful discrimination” standard is appropri

ate in fourteenth amendment voter discrimination claims.

10 Although there is a conflict between the requirement of “discrim

inatory effect” in Section 2, which is intended to enforce the fifteenth

amendment, and the requirement of “purposeful discrimination” for a

fifteenth amendment violation standing alone, the Senate Judicary

Committee addressed this point and recognized Congress’ limited abil

ity to adjust the burden of proving Voting Rights Violations in its

“Voting Rights Act Extension” Committee Report.

Certainly, Congress cannot overturn a substantive interpreta

tion of the Constitution by the Supreme Court. Such rulings can

only be altered under our form of government by constitutional

amendment or by a subsequent decision by the Supreme Court.

Thus Congress cannot alter the judicial interpretations in

Bolden of the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments by simple

statute. But the proposed amendment to Section 2 does not seek

to reverse the court’s constitutional interpretation.

S.Rep. 97-417, 97 Cong. 2d Sess. (1982), p. 41.

The Supreme Court, the only body empowered to interpret the Fed

eral Constitution, has not seen fit to overrule its repeated determina

tion that the fourteenth and fifteenth amendment claims require “pur

poseful discrimination.”

23

one vote principle did not apply to the elections of judges,

and dismissed plaintiffs’ suit. Judge Brown reversed, hold

ing that the “one man, one vote” principle as espoused in

Wells, supra, was not enough to dismiss plaintiffs com

plaint. The Voter Information Court found:

The problem with the District Court’s opinion, how

ever, is that it assumes the “one man, one vote” prin

ciple was the exclusive theory of plaintiffs com

plaints. In addition to a rather vaguely formulated

“one man, one vote” theory, plaintiffs contend that

both in design and operation, the at-large schemes

dilute the voting strength of black citizens and pre

vent blacks from being elected as judges. As the com

plaint attacking the city judge election system alleges:

25. The sole purpose of the present at-large

system of election of City Judge is to insure that

the white majority will continue to elect all white

persons for the offices of City Judge.

26. The present at-large system was instituted

when “Division B” was created as a reaction to

increasing black voter registration and for the

express purpose of diluting and minimizing the

effect of the increased black vote.

27. In Baton Rouge, there is a continuing his

tory of “bloc voting” under which when a black

candidate opposes a white candidate, the white

majority consistently casts its votes for the white

candidate, irrespective of the relative qualifica

tions.

Plaintiffs contend that since most of the black popu

lation of Baton Rouge and E. Baton Rouge Parish is

concentrated in a few geographic areas, black citizens

24

could, under a single member district plan, elect at

least some black judges.

612 F.2d at 211.

The Voter Information Project Court held the

plaintiffs complaint contained sufficient allegations of

intentional discrimination against black voters to survive a

motion to dismiss: “If plaintiffs can prove that the pur

pose and operative effect of such purpose of the at-large

election schemes in Baton Rouge is to dilute the voting

strength of black citizens, then they are entitled to some

form of relief.” 612 F.2d at 212. Thus, the Voter Informa

tion Project requires that “purpose and operative effect”

be pled in a fourteenth and fifteenth amendment challenge

to a judicial apportionment plan.

The complaint in the instant case states, in pertinent

part:

Because of the official history of racial discrimination

in Louisiana’s First Supreme Court District, the wide

spread prevalence of racially polarized voting in the

district, the continuing effects of past discrimination

on the plaintiffs, the small percentage of minorities

elected to public office in the area, the absence of any

black elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court from

the First District, and the lack of any justifiable

reason to continue the practice of electing two Jus

tices at-large from the New Orleans area only, plain

tiffs contend that the current election procedures for

selecting Supreme Court justices from the New

Orleans area dilutes minority voting strength and

therefore violates the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as

amended.

(See Plaintiffs’ Complaint, p.5). Later on, the Complaint

alleges:.

The defendants actions are in violation of the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendment to the United States

25

Constitution and 42 U.S.C. § 1983 in that the pur

pose and effect of their actions is to dilute, minimize,

and cancel the voting strength of the plaintiffs.

{Id., p. 6.)

Although “purpose and effect” language in the second

quotation above broadly read may imply plaintiffs’ inten

tion to plead discriminatory intent, it is this Court’s con

sidered opinion, based on the complaint as a whole, that

plaintiffs intend to prove this claim based on a theory of

“discriminatory effect” and not on a theory of “discrimi

natory intent.” City o f Mobile Alabama v. Bolden, supra.

For example, plaintiffs’ complaint does not allege the

system by which the Louisiana Supreme Court Justices are

elected was instituted with specific intent to discriminate.

This contrasts with the specific allegations in Voter Infor

mation Project, supra. Accordingly, plaintiffs lack the re

quisite allegations in order to prove a violation of the four

teenth or fifteenth amendment to the Federal Constitu

tion. The Court reserves the right for plaintiffs to reurge

its fourteenth and fifteenth amendment claims as they

relate to the Court’s ruling that plaintiffs’ complaint only

alleges “discriminatory effect.”

Accordingly, unless plaintiffs’ complaint is amended

within ten (10) days of the entry of this opinion, the Clerk

of Court is directed to enter judgment DISMISSING

plaintiffs’ claim at their cost.

New Orleans, Louisiana, this 1st day of May, 1987.

/ s / C harles Sc h w a r tz , J r .

Charles Schwartz, Jr.

United States District Judge

26

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 87-3463

R o nald C h iso m , et a l „ pla in tiffs-a ppella n ts

versus

E dw in E dw ards, et a l ., defen da nts-a ppellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT

OF LOUISIANA

February 29, 1988

Before B r o w n , J o h n so n , and H ig g in bo th a m , Circuit

Judges. J o h n so n , Circuit Judge:

Plaintiffs, black registered voters in Orleans Parish,

Louisiana, raise constitutional challenges to the present

system of electing Louisiana Supreme Court Justices from

the First Supreme Court District. Plaintiffs allege that the

current at-large system of electing Justices from the First

District impermissibly dilutes the voting strength of black

voters in Orleans Parish in violation of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended in 1982 and the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments. The district court

dismissed the section 2 claim pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P.

12(b)(6) for failure to state a claim, finding that section 2

does not apply to the election of state judges. Concluding

that section 2 does so apply, we reverse.

27

The primary issue before this Court is whether section 2

of the Voting Rights Act applies to state judicial elections.

I. FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY

The facts are undisputed. Currently, the seven Justices

on the Supreme Court of Louisiana are elected from six

geographical judicial districts. Five of the six districts elect

one Justice each. However, the First District, comprised

of four parishes (Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaquemines, and

Jefferson Parishes), elects two Justices at-large.

The population of the four parish First Supreme Court

District is approximately thirty-four percent black and

sixty-three percent white. The registered voter population

reveals a somewhat similar percentage breakdown, with

approximately thirty-two percent black and sixty-eight

percent white. Over half of the four parish First Supreme

Court District’s population and over half of the district’s

registered voters live in Orleans Parish. Importantly,

Orleans Parish has a fifty-five percent black population

and a fifty-two percent black registered voter population.

Plaintiffs seek a division of the First District into two

single-member districts, each to elect one Justice. Under

the plaintiffs’ plan of division, one proposed district

would be composed of Orleans Parish with a greater black

population and black registered voter population than

white. The other proposed district would be composed of

Jefferson, Plaquemines, and St. Bernard Parishes; this

district would have a substantially greater white popula

tion and white registered voter population than black. It is

particularly significant that no black person has ever been

elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court, either from the

First Supreme Court District or from any one of the other

five judicial districts.

28

To support their voter dilution claim, plaintiffs cite,

among other factors, a history of purposeful official dis

crimination on the basis of race in Louisiana and the exist

ence of widespread racially polarized voting in elections

involving black and white candidates. Specifically, plain

tiffs allege in their complaint:

Because of the official history of racial discrimination

in Louisiana’s First Supreme Court District, the wide

spread prevalence of racially polarized voting in the

district, the continuing effects of past discrimination

on the plaintiffs, the small percentage of minorities

elected to public office in the area, the absence of any

blacks elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court from

the First District, and the lack of any justifiable rea

son to continue the practice of electing two Justices

at-large from the New Orleans area only, plaintiffs

contend that the current election procedures for

selecting Surpreme Court Justices from the New

Orleans area dilutes minority voting strength and

therefore violates the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as

amended.

On May 1, 1987, the district court dismissed plaintiffs’

complaint for failure to state a claim upon which relief

may be granted. In its opinion accompanying the dismissal

order, the district court concluded that section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act does not apply to the election of state

judges. To support this conclusion, the district court relied

primarily on the amended language in section 2 which

states “to elect representatives of their choice.” The district

court reasoned that since judges are not “representatives,”

judicial elections are therefore not within the protective

ambit of section 2. Focusing on a perceived inherent dif

ference between representatives and judges, the district

court stated, “[jjudges, by their very definition, do not

29

represent voters but are ‘appointed [or elected] to preside

and administer the law.’ ” (citation omitted). The district

court further relied on what was understood to be a lack of

any reference to judicial elections in the legislative history

of section 2, and on previous court decisions establishing

that the “one person, one vote” principle does not apply to

judicial elections. As to plaintiffs’ fourteenth and fifteenth

amendment challenges, the district court determined that

plaintiffs had failed to plead an intent to discriminate with

sufficient specificity to support their constitutional claims.

Plaintiffs appeal the district court’s dismissal of both their

statutory and constitutional claims.

In an opinion just released, the Sixth Circuit, addressing

a complaint that the present system of electing municipal

judges to the Hamilton County Municipal Court in Ohio

violates section 2, concluded that section 2 does indeed

apply to the judiciary. Mallory v. Eyrich, No. 87-3838,

slip op. (6th Cir. Feb. 12, 1988). Other than our district

court, only two district courts have ruled on the coverage

of section 2 in this context. The Mallory district court,

subsequently reversed, concluded that section 2 does not

extend to the judiciary. Mallory v. Eyrich, 666 F. Supp.

1060 (S.D. Ohio 1987). The other district court, Martin v.

Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183 (S.D. Miss. 1987), determined

that section 2 does apply to the judicial branch. After con

sideration of the language of the Act itself; the policies

behind the enactment of section 2; pertinent legislative his

tory; previous judicial interpretations of section 5, a com

panion section to section 2 in the Act; and the position of

the United States Attorney General on this issue; we con

clude that section 2 does apply to the election of state

court judges. We therefore reverse the judgment of the

district court.

30

II. DISCUSSION

A. The Plain Language of the Act

The Voting Rights Act was enacted by Congress in 1965

for a broad remedial purpose —“to rid the country of

racial discrimination in voting.” South Carolina v. Katzen-

bach, 383 U.S. 301, 315 (1966). Since the inception of the

Act, the Supreme Court has consistently interpreted the

Act in a manner which affords it “the broadest possible

scope” in combatting racial discrimination. Allen v. State

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 565 (1969). As a result,

the Act effectively regulates a wide range of voting prac

tices and procedures. See United States v. Sheffield Board

of Commissioners, 435 U.S. 110, 122-23 (1978). Referred

to by the Supreme Court as a provision which “broadly

prohibits the use of voting rules to abridge exercise of the

franchise on racial grounds,” Katzenbach, 383 U.S. at

316, section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, prior to its

amendment in 1982, provided as follows:

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or

applied by any State or political subdivision to deny

or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States

to vote on account of race or color, or in contraven

tion of the guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2)

of this title.

Congress amended section 2 in 1982 in response to the

Supreme Court’s decision in Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S.

55 (1980), wherein the Court concluded that section 2

operated to prohibit only intentional acts of discrimina

tion by state officials. Thereafter, Congress, in disagree

ment with the high court’s pronouncement, amended sec

tion 2 with language providing that proof of intent is not

required to successfully prove a section 2 violation. In

31

stead, Congress adopted the “results” test, whereby plain

tiffs may prevail under section 2 by demonstrating that,

under the totality of the circumstances, a challenged elec

tion law or procedure has the effect of denying or abridg

ing the right to vote on the basis of race. However, while

effecting significant change through the 1982 amend

ments, Congress specifically retained the operative lan

guage or original section 2 defining the section’s coverage

- “[n]o voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed. . .

Section 2, as amended in 1982, now provides:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be im

posed or applied by any State or political subdivision

in a manner which results in a denial or abridgement

of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote

on account of race or color, or in contravention of the

guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of this title,

as provided in subsection (b) of this section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established if,

based on the totality of circumstances, it is shown

that the political processes leading to nomination or

election in the State or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by members of a class of

citizens protected by subsection (a) of this section in

that its members have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the politi

cal process and to elect representatives of their choice.

The extent to which members of a protected class

have been elected to office in the State or political

subdivision is one circumstance which may be consid

ered: Provided, That nothing in this section estab

lishes a right to have members of a protected class

32

elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the

population.

Section 14(c)(1), which defines “voting” and “vote” for

purposes of the Act, sets forth the types of election prac

tices and elections which are encompassed within the regu

latory sphere of the Act. Section 14(c)(1) states,

The terms “vote” of “voting” shall include all action

necessary to make a vote effective in any primary,

special, or general election, including, but not limited

to, registration, listing pursuant to this subchapter or

other action required by law prerequisite to voting,

casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted prop

erly and included in the appropriate totals of votes

cast with respect to candidates for public or party of

fice and propositions for which votes are received in

an election.

Clearly, judges are “candidates for public or party office”

elected in a primary, special, or general election; there

fore, section 2, by its express terms, extends to state judi

cial elections. This truly is the only construction consistent

with the plain language of the Act.1

In Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 831 F. 2d 246 (11th Cir.

1987), the Eleventh Circuit addressed the issue of the

coverage of section 2. In Dillard, the court rejected the

defendant county’s implicit argument that the election of

an at-large chairperson of a county commission was not

covered by section 2 due to that position’s administrative,

as opposed to legislative, character. The Dillard court

stated,

Nowhere in the language of Section 2 nor in the leg

islative history does Congress condition the applica

1 Evidence of congressional intent to reach all types of elections,

regardless of who or what is the object of the vote, is the fact that

votes on propositions are within the purview of the Act. Section

14(c)(1).

33

bility of Section 2 on the function performed by an

elected official. The language is only and uncompro

misingly premised on the face of nomination or elec

tion. Thus, on the face of Section 2 it is irrelevant that

the chairperson performs only administrative and

executive duties. It is only relevant that Calhoun

County has expressed an interest in retaining the post

as an electoral position. Once a post is open to the

electorate, and if it is shown that the context of that

election creates a discriminatory but corrigible elec

tion practice, it must be open in a way that allows

racial groups to participate equally.

Id. at 250.

The State asserts that by amending section 2 in 1982,

Congress intentionally grafted a limitation on section

14(c)(1) that “candidates for public or party office” only

include “representatives”; since judges are not “representa

tives,” state judicial elections are exempt from the protec

tive measures of the Act. In making this contention, the

State, as well as the district court, points to the distinctive

functions of judges as opposed to other elected officials.

Specifically, the district court, citing Wells v. Edwards,

347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972), affd , 409 U.S. 1095

(1973), notes that the “one person, one vote” principle of

apportionment has been held not to apply to the judicial

branch of government on the basis of this distinction. See

also Voter Information Project v. City of Baton Rouge,

612 F.2d 208 (5th Cir. 1980). In Wells, the plaintiff sought

reapportionment of the Louisiana Supreme Court Judicial

Districts in accordance with one person, one vote princi

ples. The Wells court rejected the plaintiffs claim, reason

ing that the “primary purpose of one-man, one-vote

apportionment is to make sure that each official member

of an elected body speaks for approximately the same

number of constituents.” Wells, 347 F. Supp. at 455. The

district court then concluded that since judges do not rep

34

resent, but instead serve people, the rationale behind one

person, one vote apportionment of preserving a represen

tative form of government is not relevant to the judiciary.

Id.

In Voter Information, this Court, bound by the holding

in Wells due to the Supreme Court’s summary affirmance

of that decision, rejected the plaintiffs’ claim for reappor

tionment of judicial districts on the one person, one vote

theory. Voter Information, 612 F.2d at 211. However, the

Voter Information Court then emphasized that the plain

tiffs further asserted claims of racial discrimination under

the fifteenth amendment which resulted in the dilution of

black voting strength. Recognizing the difference between

the two types of claims, the Court expressly rejected the

applicability of the Wells decision to claims of racial dis

crimination, stating,

[T]he various ‘one man one vote’ cases involving

Judges make clear that they do not involve claims of

race discrimination as such.

To hold that a system designed to dilute the voting

strength of black citizens and prevent the election of

blacks as Judges is immune from attack would be to

ignore both the language and purpose of the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments. The Supreme

Court has frequently recognized that election schemes

not otherwise subject to attack may be unconstitu

tional when designed and operated to discriminate

against racial minorities.

Id. (footnote omitted).

We, like the Voter Information Court, are bound by the

Supreme Court’s affirmance of Wells and its holding that

the one person, one vote principle does not extend to the

judicial branch of government. However, the district

court’s reliance on Wells in the instant case is misplaced as

35

we are not concerned with a complaint seeking reappor

tionment of judicial districts on the basis of population

deviations between districts. Rather, the complaint in the

instant case involves claims of racial discrimination result

ing in vote dilution under section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act and the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments. There

fore, the district court erred to the extent it relied on Wells

in support of its conclusion that section 2 does not apply

to the judiciary.2

The Voting Rights Act was enacted, in part, to facilitate

the enforcement of the guarantees afforded by the Consti

tution. Indeed, section 2, as originally written, no more

than elaborated on the fifteenth amendment, providing

statutory protection consonant with that of the constitu

tional guarantee. Mobile, 446 U.S. at 60. Therefore, the

reasoning utilized by the Court in Voter Information to

extend the protection from racial discrimination provided

by the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the

judiciary compels a conclusion by this Court that the pro

tection from racial discrimination provided by section 2

likewise extends to state judicial elections.

It is difficult, if not impossible, for this Court to con

ceive of Congress, in an express attempt to expand the

2 The distinction between equal protection principles applicable to

claims based on one person, one vote principles of apportionment and

those based on racial discrimination is not without prior Supreme

Court precedent. See White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (Court reversed

decision of district court that reapportionment plan for Texas House

of Representatives violated one person, one vote principles, but af

firmed the district court’s conclusion that a particular portion of the

plan unlawfully diluted minority voting strength.). See also Gaffney v.

Cummings. 412 U.S. 735, 751 (1973) (“A districting plan may create

multimember districts perfectly acceptable under equal population

standards, but invidiously discriminatory because they are employed

‘to minimize or cancel out the voting strength of racial or political ele

ments of the voting population.’ ”) (citations omitted).

36

coverage of the Voting Rights Act, to have in fact

amended the Act in a manner affording minorities less

protection from racial discrimination than that provided

by the Constitution. We conclude today that section 2 as

amended in 1982, provides protection commensurate with

the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments; therefore, in

accordance with this Court’s decision in Voter Informa

tion, section 2 necessarily embraced judicial elections

within its scope. Any other construction of section 2

would be wholly inconsistent with the plain language of

the Act and the express purpose which Congress sought to

attain in amending section 2; that is, to expand the protec

tion of the Act.

B. The Legislative History of Section 2

Our conclusion today finds further support in the legis

lative history of the 1982 amendments to section 2. An

overriding principle which guides any analysis of the legis

lative history behind the Voting Rights Act is that the Act

must be interpreted in a broad and comprehensive manner

in accordance with congressional intent to combat racial

discrimination of any kind in all voting practices and pro

cedures. Thus, in the absence of any legislative history

warranting a conclusion that section 2 does not apply to

state judicial elections, the only acceptable interpretation

of the Act is that such elections are so covered. See Shef

field, 435 U.S. 110.3

3 In Sheffield, the Supreme Court declined to adopt a narrowing

construction of § 5 and the preclearance requirements of the Act

whereby § 5 would cover only counties and political units that conduct

voter registration. “[I]n view of the structure of the Act, it would be

unthinkable to adopt the District Court’s construction unless there

were persuasive evidence either that § 5 was intended to apply only to

changes affecting the registration process or that Congress clearly

manifested an intention to restrict § 5 coverage. . . .” 435 U.S. at 122.

37

The Senate Report states that amended [section] 2

was designed to restore the “results test” —the legal

standard that governed voting discrimination cases

prior to our decision in Mobile v. Bolden. . . . Under

the “results test,” plaintiffs are not required to dem

onstrate that the challenged electoral law or structure

was designed or maintained for a discriminatory pur

pose.

Thornburg v. Gingles,___ U .S .____ , 106 S. Ct. 2752 ,

2763 n.8 (1986) (citations omitted). In amending section 2,

Congress preserved the operative language of subsection

(a) defining the coverage of the Act and merely added sub

section (b) to adopt the “results test” for proving a viola

tion of section 2. In fact, the language added by Congress

in subsection (b) —“to participate in the political process

and to elect representatives of their choice” —is derived

almost verbatim from the Supreme Court’s standard

governing claims of vote dilution on the basis of race set

forth in White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973), prior to

Mobile v. Bolden. See S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d

Sess. 27, reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin.

News 177, 205 (Congress’ stated purpose in adding subsec

tion (b) was to “embodfy] the test laid down by the

Supreme Court in White.”). In White, the Court stated

“[t]he plaintiffs’ burden is to produce evidence . . . that

[the minority groups’] members had less opportunity than

did other residents in the district to participate in the

political processes and to elect legislators of their choice.”

Id. at 766.4

As previously noted, Congress amended section 2 in

direct response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Mobile

v. Bolden,

4 It might be argued that since the Supreme Court used the term

“legislators” and Congress chose “representatives,” Congress thereby

rejected language limiting the coverage of § 2 to legislators. The better

38

Further, contrary to the statement in the district court’s

opinion that the legislative history of the 1982 amend

ments does not address the issue of section 2 applying to

the judiciary, Senator Orrin Hatch, in comments con

tained in the Senate Report, stated that the term

“ ‘political subdivision’ encompasses all governmental

units, including city and county councils, school boards,

judicial districts, utility districts, as well as state legisla

tures.” S. Rep. 417 at 151 (emphasis added). While the

above statement by Senator Hatch is not a definitive de

scription of the scope of the Act, we believe the statement

provides persuasive evidence of congressional understand

ing and belief that section 2 applies to the judiciary,

especially since the Report is silent as to any dissent by

senators from Senator Hatch’s description.

Additionally, the Senate and House hearings on the

various bills regarding the extension of the Voting Rights

Act in 1982 are replete with references to the election of

judicial officials under the Act. The references primarily

occur in the context of statistics presented to Congress in

dicating advances or setbacks of minorities under the Act.

The statistics chart the election of minorities to various

elected positions, including judges. See Extension o f the

Voting Rights Act: Hearings on H.R. 1407, H.R. 1731,

H.R. 2942, and H.R. 3112, H.R. 3198, H.R. 3473 and

H.R. 3498 Before the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitu

tional Rights o f the House Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th

Cong. 1st Sess. 38, 193, 239, 280, 503, 574, 804, 937, 1182,

1188, 1515, 1528, 1535, 1745, 1839, 2647 (1981); Voting

Rights Act: Hearings on S. 53, S. 1761, S. 1975, S. 1992,

and H.R. 3112 Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution

analysis is that Congress did not use the term “representatives” with a

specific intent to limit the section’s application to any elected officials.

Had Congress wished to do so, it could have easily promulgated ex

press language to effectuate that intent.

39

o f the Senate Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th Cong. 2d

Sess. 669, 748, 788-89 (1982). Once again, the legislative

history does not reveal any dissent from the proposition

that such statistics were properly considered by Congress

in amending the Act. Finally, throughout the Senate

Report on the 1982 amendments to section 2, Congress

uses the terms “officials,” “candidates,” and “representa

tives” interchangeably when explaining the meaning and

purpose of the Act. This lack of any consistent use of the

term “representatives” indicates that Congress did not in

tentionally choose that term in an effort to exclude certain

types of elected officials from the coverage of the Act.

In contrast to the examples of legislative history which

plaintiffs cite in support of their position that section 2 ap

plies to state judicial elections, the State offers no convinc

ing evidence in the legislative history contrary to the plain

tiffs interpretation of the Act. Instead, the State relies pri

marily on the plain meaning of the word “representative”

to assert that judges are exempt from the Act. The State’s

position is untenable.5 Judges, while not “representatives”

5 The State asserts that the Dole compromise prohibiting propor

tional representation evidences congressional intent that § 2 only ap

ply to legislative officials. Proportional representation, the State con

tinues, is relevant to the legislature; therefore, Congress intended § 2

to apply only to the election of legislators. However, what belies the

State’s argument is that proportional representation may occur in any

election wherein the people elect individuals to comprise a group. For

instance, Louisiana elects seven Justices to comprise the Supreme

Court. Certainly, the prohibition on proportional representation in

§ 2(b) applies in such a situation to prevent a legal requirement that

the number of blacks on the Louisiana Supreme Court correspond to

the percentage of blacks in the Louisiana population. Moreover, the

State conceded at oral argument that executive officials could be

covered by § 2, underlying their assertion that congressional fear of

proportional representation evidenced intent that § 2 only apply to the

legislature.

40

in the traditional sense, do indeed reflect the sentiment of

the majority of the people as to the individuals they choose

to entrust with the responsibility of administering the law.

As the district court held in Martin v. Allain:

[Jjudges do not “represent” those who elect them in

the same context as legislators represent their con

stituents. The use of the word “representatives” in

Section 2 is not restricted to legislative representatives

but denotes anyone selected or chosen by popular

election from among a field of candidates to fill an

office, including judges.

658 F. Supp. at 1200.

C. Section 5 and Section 2

The plaintiffs further support their position that judicial

elections are covered by section 2 by citing to the recent

case of Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C.

1985), affd, ___ U.S. ___ , 106 S. Ct. 3268 (1986),

wherein the district court held that judicial elections are

covered by section 5 and the preclearance requirements of

the Act. In Haith, the defendant state officials sought to

exempt the election of superior court judges in North

Carolina from the preclearance requirements of section 5

by relying on the cases holding that the one person, one

vote principle does not apply to the judicial branch of

government. In an analysis strikingly similar to that em

ployed by the Court in Voter Information, the district

court in Haith rejected the defendants’ arguments as mis

placed due to the fact that the plaintiffs claim was one

based on discrimination, not malapportionment. The

Haith court stated “[a]s can be seen, the Act applies to all

voting without any limitation as to who, or what, is the

object of the vote.” 618 F. Supp. at 413. See also Kirksey

v. Allain, 635 F. Supp. 347, 349 (S.D. Miss. 1986) (“Given

41

the expansive interpretation of the Voting Rights Act and

§ 5, this Court is compelled to agree with the pronounce

ment in Haith v. Martin” that section 5 applies to the

judiciary.).

In the instant case, the State argues that the Supreme

Court’s affirmance of Haith does not compel a conclusion

that section 2 applies to judicial elections as section 5 in

volves the mechanics of voting, while section 2 involves

the fundamental right to vote for those who govern. We

reject this asserted distinction. If, for instance, Louisiana

were to enact an election statute providing that no blacks

would be able to vote in elections for Louisiana Supreme

Court Justices, it is undisputed, after Haith, that such a

statute would be invalidated under the preclearance re

quirements of section 5. To hold, as the State asserts, that

such an egregious statute would not be subject to the re

quirements of section 2 as well would lead to the incon

gruous result that, while Louisiana could not adopt such a

statute in 1988, if that statute were in effect prior to 1982,

minorities could only challenge the statute under the Con

stitution and not the Voting Rights Act. Such a result

would be totally inconsistent with the broad remedial pur

pose of the Act. Moreover, section 5 and section 2, virtual

ly companion sections, operate in tandem to prohibit dis

criminatory practices in voting, whether those practices

originate in the past, present, or future. Section 5 contains

virtually identical language defining its scope to that of

section 2 - “any voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with respect to

voting. . . .” Therefore, statutory construction, consist

ency, and practicality point inexorably to the conclusion

that if section 5 applies to the judiciary, section 2 must

also apply to the judiciary. See Pampanga Mills v. Trini

dad, 279 U.S. 211, 217-218 (1929).

42

D. The Attorney General's Interpretation

In United States v. Sheffield Board of Commissioners,

435 U.S. at 131, the Supreme Court concluded that the

contemporaneous construction of the Act by the Attorney

General is persuasive evidence of the original congres

sional understanding of the Act, “especially in light of the

extensive role the Attorney General played in drafting the

statute and explaining its operation to Congress.” Since its

inception, the Attorney General has consistently sup

ported an expansive, not restrictive, construction of the

Act. Testifying at congressional hearings prior to the

passage of the Act in 1965, the Attorney General stated

that “every election in which registered voters are per

mitted to vote would be covered” by the Act. Voting

Rights: Hearing Before Subcomm. No. 5 o f the House

Judiciary Comm., 89th Cong. 1st Sess. (1965), at 21. See

also Allen, 393 U.S. at 566-67. Continuing the trend of

broadly interpreting the Act to further its remedial pur

pose, the Attorney General has filed an amicus curiae brief

in the instant case in which he maintains that the “plain

meaning of [the language in section 2] reaches all elec

tions, including judicial elections” and that the preexisting

coverage of section 2 was not limited by the 1982 congres

sional amendments. This construction of the Act by the

Attorney General further bolsters our holding today that

section 2 does apply to state judicial elections.

E. Plaintiffs' Constitutional Claims