Crawford v. Los Angeles Board of Education Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Crawford v. Los Angeles Board of Education Brief Amici Curiae, 1981. b0282197-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dbdc3ff9-8dd9-4fc5-9826-5b6ab5f84437/crawford-v-los-angeles-board-of-education-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

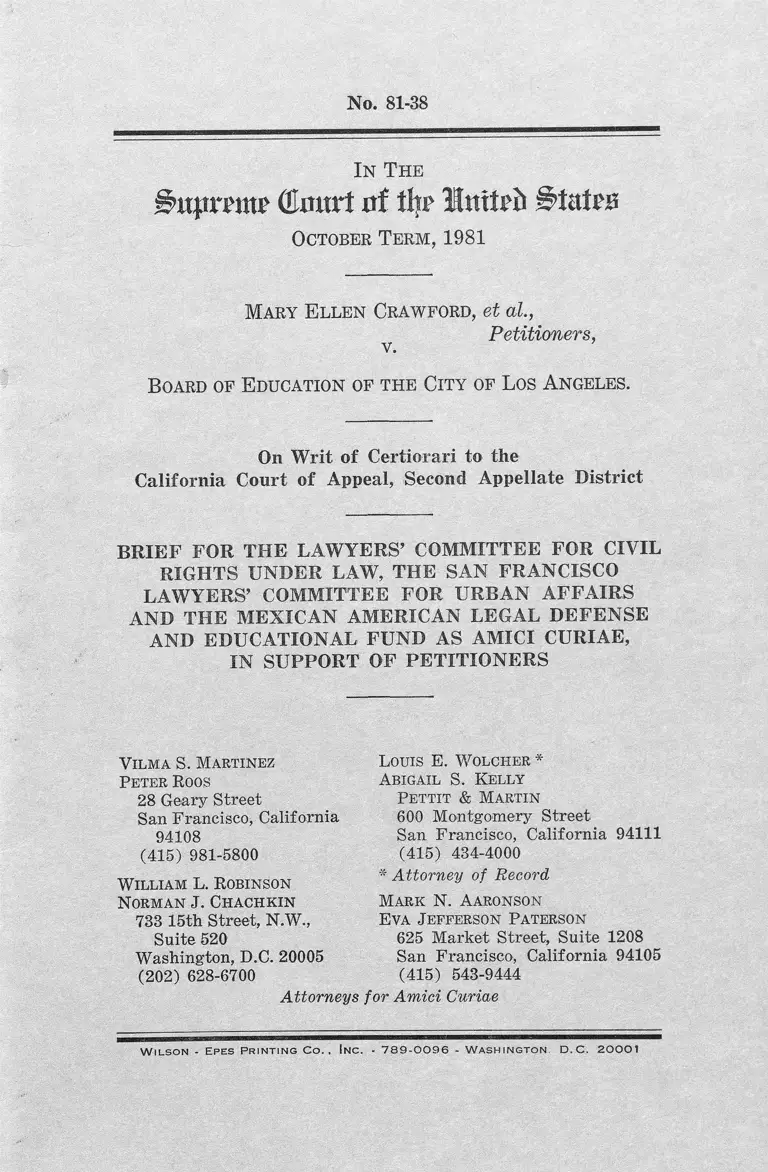

No. 81-38

In T he

Bupmm ( t a r t o f thr l i n t r b i t a t e

October Term , 1981

Mary Ellen Crawford, et a t ,

Petitioners,v.

Board of Education of the City of Los A ngeles.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

California Court of Appeal, Second Appellate District

BRIEF FOR THE LAW YERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE SAN FRANCISCO

LAW YERS’ COMMITTEE FOR URBAN AFFAIRS

AND THE M EXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND AS AMICI CURIAE,

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

V ilma S. Martinez

Peter Roos

28 Geary Street

San Francisco, California

94108

(415) 981-5800

W illiam L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin

733 15th Street, N.W.,

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

Louis E. Wolcher *

Abigail S. Kelly

Pettit & Martin

600 Montgomery Street

San Francisco, California 94111

(415) 434-4000

* Attorney of Record

Mark N. Aaronson

Eva Jefferson Paterson

625 Market Street, Suite 1208

San Francisco, California 94105

(415) 543-9444

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

W ils on - Epes Pr in t in g C o ., !n c . - 7 8 9 -0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n D .C . 20001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE .................... ............... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................. 2

ARGUMENT ........................................................ 5

TABLE OF AU TH O RITIES............................................ iii

I. PROPOSITION 1 MUST BE JUDGED IN THE

HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF LONGSTAND

ING OFFICIAL SUPPORT FOR SEGREGA

TION AND DISCRIMINATION IN CALIFOR

NIA, WHICH REINFORCES THE OTHER

EVIDENCE SHOWING THAT ITS PASSAGE

W AS MOTIVATED BY RACIAL ANIMUS

AND AN INTENT TO DISCRIMINATE____ 5

II. WHILE THERE IS ENOUGH EVIDENCE IN

THE EXISTING RECORD TO SHOW PROPO

SITION 1 IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL, THERE

IS NOT ENOUGH EVIDENCE TO SUSTAIN

ITS CONSTITUTIONALITY .............. .......... 12

A. The Constitutionality of Proposition 1 Can

not be Determined Without an Examination

of Its Impact on Minority Students_______ 14

B. The Constitutionality of Proposition 1 Can

not be Determined Without an Examination

of Its Historical Background______________ 16

III. PROPOSITION 1 IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL

BECAUSE IT DENIES THE POWER OF

STATE COURTS OF GENERAL JURISDIC

TION TO GIVE REMEDIES WHICH ARE

NECESSARY TO REDRESS C E R T A I N

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT VIOLATIONS,

IN CASES WHERE CONGRESS M AY AT

TEMPT TO CURTAIL LOWER FEDERAL

COURT JURISDICTION .... ....... ........................... 18

11

A. As Courts of General Jurisdiction, State

Courts May Not Be Limited in Their Ability

to Impose Necessary Remedies for Federal

Constitutional Violations .....- ........................... 19

B. In Violation of Due Process of Law, Propo

sition 1 Unconstitutionally Links State Court

Jurisdiction to Give Necessary Remedies to

Limits on Federal Court Jurisdiction .... .- 22

IV. IN DECIDING THAT THE SEGREGATION

IN THE LOS ANGELES PUBLIC SCHOOL

SYSTEM DOES NOT VIOLATE THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT AS A MATTER OF

LAW, THE COURT OF APPEAL ERRONE

OUSLY REVERSED THE TRIAL COURT

W HEN IT OUGHT TO HAVE OPENED THE

RECORD FOR FURTHER FACTUAL IN

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Page

QUIRY ........................................................................... 26

CONCLUSION...................... .......... -...... - ............................. 30

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Battaglia v. General Motors Corp., 169 F.2d 254

(2d Cir.), cert, denied, 335 U.S. 887 (1948)— 22

Board of Educ. of Long Beach v. Jack M., 19 Cal.

2d 691, 566 P.2d 602, 139 Cal. Rptr. 700 (1977).. 28n

Columbus Bd. of Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979) ........ ................... ............-......................- ....7-8 ,28,29

Crawford v. Board of Educ. (Crawford I) , 17

Cal. 3d 280, 551 P.2d 28, 130 Cal. Rptr. 724

(1976) ................................................ 1 4 ,18n, 26, 27n, 28, 29

Crawford v. Board of Educ. (Crawford II), 113

Cal. App. 3d 633, 170 Cal. Rptr. 495 (1980).-. 13,14,

16, 23

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S, 526

(1979) .......................................................... -----............ 8

General Oil Co. v. Crain, 209 U.S. 211 (1908)..... 21

Guam v. Olsen, 431 U.S. 195 (1977)---------- ------ - - 20

Johnson v. Richmond Unified School Dist., No.

112094 (Super. Ct., Contra Costa County, April

3, 1972) ............................ .......................................... Hn, 18n

Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S. 361 (1974)............... 20

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School Dist., 500

F.2d 349 (9th Cir. 1974) ......................................... 27

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ......... 25n

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) .........................................-...... - ....... - -...... -....... 29

Lauf v. E.G. Shinner & Co., 303 U.S. 323 (1938).... 22

Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680,

186 P. 596 (1919) ......................................... -............ 6, 9n

Maine v. Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1 (1980) .... ......... . 21,22

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) -------------- 12

North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v. Swann, 402

U.S. 43 (1971) ......... ....... -................ ------- ------------- 24

Palm ore v. United States, 441 U.S. 389 (1973)—. 20n

Personnel Administrator v. Feeney, 432 U.S. 256

(1979) ............................................ ...............-...... -....... 13

Perez v. Sharp, 32 Cal. 2d 711,198 P.2d 17 (1947).. 10n

Piper v. Big Pine School Dist., 193 Cal. 664, 226

P. 926 (1924) ............ ........... ------------------------------9n, lOn

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) .............. - 5, 6, 7,

lln , 16

iv

San Francisco Unified School Dist. v. Johnson, 8

Cal. 3d 937, 479 P.2d 669, 92 Cal. Rptr. 309,

cert, denied sub nom. Fehlhaber v. San Fran

cisco Unified School Dist., 401 U.S. 1012 (1971) ..lln , 14

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Santa Barbara School Dist. v. Superior Ct., 13

Cal. 3d 315, 530 P.2d 605, 18 Cal. Rptr. 637

(1975) .........- ........ ................................. -____________Hn, 17

Sheldon v. Sill, 49 U.S. (8 How.) 441 (1850)........ 20n

Soria v. Oxnard School Dist. Bd. of Trustees, 386

F. Supp. 539 (C.D. Cal. 1974) __________________ lOn

Spangler v. Pasadena City School Dist., 311 F.

Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) _______ .___ _________ lOn

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) ____ __ ________________ _______15n, 24, 29

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229

(1969) ................................. ................... ......... - ......... 21

Tape v. Hurley, 66 Cal. 473, 6 P. 129 (1885)...... . 9n

Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1947) _______________ 21

Time, Inc. v. Firestone, 424 U.S. 448 (1976)------ 12

Tinsley v. Palo Alto Unified School Dist., No.

206010 (Super. Ct., San Mateo County, July 10,

1980), quoted in Board of Educ. v. Superior Ct.,

448 U.S. 1343 (1980) (Rehnquist, Circuit Jus

tice) ------------------ ------------------------------------------ ------- 23

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U.S. 312 (1921)------ -------- 22

United States v. Klein, 80' U.S. (13 Wall.) 128

(1872) ................................ ..................... - ............-...... 20

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333

U.S. 364 (1948) _____________________________- - 28n

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Hous

ing Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) .............5,13, 14,18

Ward v. Flood, 48 Call. 36 (1874) ---- -------------------- 9n

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ---------- 13

W.E.B. DuBois Clubs v. Clark, 389 U.S. 309

(1967) _______________ ____________ ______ -........ - . 12

Wong Him v. Callahan, 119 F. 38 (C.C.N.D. Cal.

1902) __ ______ _______________________ __________ 9n

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) - .......... ....................... ..... ....................... ~~ 24

V

Wysinger v. Crookshank, 82 Cal. 588, 23 P. 54

(1890) ....................... -....................................-.............. 9n

Yakus v. United States, 321 U.S. 414 (1944)........ 20

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ..... —. 9n

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc., 395

U.S. 100 (1969) ............ ......... ......... - ..............- ..... 28n

Constitutions and Statutes

U.S. Const., art. Ill, § 1 ......... ................. - .....— 20n

Cal. Const., art. I, § 7 (a) ......- .............. - -.......... 2n

Ca . Const., art. II, § 106; art. IV, § 116 (1849).. 8n

Norris-LaGuardia Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 101-15 (1976).. 21

Cal. Educ. Code § 35350 (1978) (West) ----------- 17n

Cal . Educ. Code §35351 (1978) (West) ........ 17n

Cal. Educ. Code § 1009.5 (1970) ______ 17n

Cal. Educ. Code § 1009.6 (1972) .............. ............- 17n

Act of April 7, 1880, 1880 Cal. Stat. Amend, at 47.. 9n

Cal. Pol. Code §§ 1662, 1669 (1872) .......... .......... 8n

Act of April 4, 1870, 1867-70 Cal. Stats., ch. 556,

§ 56, at 838-39 --------------- ------------------- ------------- - 8n

Act of March 24, 1866, 1865-66 Cal. Stats., ch. 342,

§§ 57-59, at 398------------------ --------------- ------- -------- 8n

Act of March 22, 1864, 1863-64 Cal. Stats., ch. 209,

§ 13, at 2 1 3 ______ ___ ------- --------------------------------- 8n

Act of April 6, 1863, 1863 Cal. Stats., ch. 159, § 68,

at 210 ________________- ....... ------- ------------------ - .... 8n

1850 Cal. Stats., ch. 99, § 14, at 230 -------- ---- --------- 8n

1850 Cal. Stats., ch. 140, at 424 --------------------- ----- 8n

1850 Cal. Stats., ch. 142, § 306, at 455 ................- 8n

Legislative Materials

H.R. Rep. No. 669, 72d Cong., 1st Sess. (1932).... 22

S. 158, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) -------- 26n

S. 481, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) ....................... 26n

S. 1647, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981)........................ 25

S. 1743, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) ------- 25

S. 1760, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981)------------ ------ - 25

H.R. 72, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) .... ................ 26n

H.R. 865, 97th Cong., 1st Sess, (1981) .......... - ...... 26n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

VI

H.R. 867, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) ............ -..... 26n

1867-68 Cal. State Jo u rn al ...................... .......----- 9n

Other Authorities

P. Bator, P. Mish kin , D. Shapiro & H. Wechs-

ler, Hart & W echsler’s The F ederal Courts

and the Federal System (2d ed. 1978) ............ 19

Chicago Defender, April 27, 1957 .................... -....... 44x1

Comment, Proposition 1 and Federal Protection of

State Constitutional Rights, 75 Nw. U.L. Rev.

685 (1980) ..... —------- --------- ---------- ------.....--------H n, 4,4

Eisenberg, Congressional Authority to Restrict

Lower Federal Court Jurisdiction, 83 Y ale L.J.

498 (1974) ....................................................... ----- 20n

Goldberg, The Administration’s Anti-Busing Pro

posals—Politics Makes Bad Law, 67 Nw. U.L.

Rev. 319 (1972) .... ............... -----................ ........... 24

G. Gunther, Cases and Materials on Constitu

tional Law (9th ed. 1975) ------ ------------- -----— 24

Hart, The Power of Congress to Limit the Juris

diction of Federal Courts: An Exercise in Dia

lectic, 66 Harv. L. Rev. 1362 (1953) .................. 21,26

I. Hendrick, The Education of Non-W hites in

California 1849-1970 (1977) ..... .......................10n, 28n

Note, California’s Anti-Busing Amendment: A

Perspective on the Now Unequal Protection

Clause, 10 Golden Gate U.L. Rev. 611 (1980)..lln , 17

B. Reams & P. W ilson, Segregation and the

Fourteenth A mendment in the States: A

Survey of State Segregation Laws 1865-1953;

Prepared for United States Supreme Court

in re: Brown v. Board of Education of

Topeka (1975) „ ....................... -....... ------------8n> 9n, l ln

Reynolds, The Education of Spanish Speaking Chil

dren in Five Southivestem States, 1933 U.S.

Office of Education Bulletin No. 11, quoted

in C. W ollenberg, All Deliberate Speed:

Segregation and Exclusion in California

Schools, 1855-1975 (1976) ..................... ........... 10n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

VII

Rotunda, Congressional Power to Restrict the

Jurisdiction of the Lower Federal Courts and

the Problem of School Busing, 64 Geo. L.J. 839

(1976) ...... .............-....... ................................. - .......... 24-25

Sager, The Supreme Court, 1980 Term— Fore

word: Constitutional Limitations on Congress’

Authority to Regulate the Jurisdiction of the

Federal Courts, 95 Harv. L. Rev, 17 (1981)... 19, 20, 25

Tribe, Jurisdictional Gerrymandering: Zoning Dis

favored Rights Out of the Federal Courts, 16

Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 129 (1981) - ...............- 19, 25

Warren, New Light on the History of the Federal

Judiciary Act of 1789, 37 Harv. L. Rev. 49

(1923) .................. .................................................... -

C. W right, The Law of Federal Courts (3d ed.

1976) -------------------------- -----------------------------------

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

20n

In T he

Bnpvmt (Emtrt at tty Imtpft U ta te

October Term , 1981

No. 81-38

Mary Ellen Crawford, et al,

Petitioners, v. ’

Board of Education of the City of Los A ngeles.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

California Court of Appeal, Second Appellate District

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE SAN FRANCISCO

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR URBAN AFFAIRS

AND THE M EXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND AS AMICI CURIAE,

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The San Francisco Lawyers’ Committee for Urban

Affairs (“S.F. Lawyers’ Committee” ) began in 1968 as

the Northern California affiliate of the Lawyers’ Com

mittee for Civil Rights Under Law. It is organized as a

California nonprofit corporation and is classified as a

tax-exempt public charity under Section 501(c)(3 ) of

the Internal Revenue Code. The Committee’s program

involves the provision of pro bono legal representation to

poor or minority individuals. Its most recent activities

include participation in various suits concerning racial

isolation in elementary and secondary schools in the San

Francisco Area. The Committee also was active in the

2

campaign against the enactment of Proposition l,1 which

is at issue in this case, and has remained involved in

subsequent legal challenges to its constitutionality.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

(“ Lawyers’ Committee” ) was organized in 1963 at the

request of the President of the United States to involve

private attorneys throughout the country in the na

tional effort to assure civil rights to all Americans. Over

the past eighteen years, the Committee has enlisted the

services of thousands of members of the private bar in

addressing the legal problems of minorities and the poor in

voting, education (including school desegregation cases),

employment, housing, municipal services, the administra

tion of justice, and law enforcement.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund (MALDEF) is a private civil rights organization

founded in 1968, and dedicated to ensuring through law

that the civil rights of Mexican Americans are protected.

It has participated in numerous cases involving the edu

cational rights of Mexican American children, including

school desegregation cases.

Based on their respective experiences in representing

poor and minority clients on civil rights issues, in par

ticular regarding public education, amici file this brief

in support of petitioners.2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The drafters of Proposition 1 wanted it to appear to

be merely a neutral regulation of remedies which Cali

fornia state courts may use in certain school desegrega

tion cases brought under the California Constitution.

They failed to obscure its true purpose. In fact, the

measure violates a fundamental precept of the four-

1 Cal. Const, art. I, § 7 (a) (hereinafter cited as “ Proposition

1 ” ) .

2 The parties’ letters of consent to the filing of this brief are

being lodged with the Clerk pursuant to Rule 36.1.

3

teenth amendment: it purposefully isolates a particular

class of citizens on the basis of their race (minority

students seeking racial integration of California public

schools), and singles that class out for disfavored treat

ment by the state judiciary.

Amici join with the petitioners in urging this Court to

reverse the California Court of Appeal’s judgment sus

taining the constitutionality of Proposition 1, and they

embrace fully the arguments to this end made in peti

tioners’ brief. Amici submit this brief to draw the

Court’s attention to certain arguments against Proposi

tion 1 which we think deserve particular emphasis and

clarification. To that extent, this brief will not restate

all of the points made in petitioners’ brief, but will focus

on four distinct arguments.

First, amici will demonstrate that in addition to its

facial infirmities, Proposition 1 wTas passed with a spe

cific intent to discriminate against black and other mi

nority school children in California. We will draw the

Court’s attention to certain material, both in the record

and judicially noticeable, showing that Proposition 1 can

not be viewed in isolation, but must be seen as the latest

embodiment of a virulent racial prejudice which has in

fected California public and private life continuously

since before the Civil War.

Second, amici urge that there is only one alternative

to reversal of the Court of Appeal’s ruling on the con

stitutionality of Proposition 1: a remand for additional

fact-finding on the purpose behind Proposition 1. We

think ample evidence exists to show that Proposition 1

is unconstitutional because it was adopted for the pur

pose of discriminating against minority students. How

ever, the trial court never reached this issue, and the

Court of Appeal erroneously sustained Proposition l ’s

constitutionality without ever giving petitioners a full

and fair opportunity to develop factual evidence critical

to the issue.

4

Third, amici will demonstrate that Proposition 1 limits

remedies which may be necessary to vindicate federal

constitutional rights in cases of school segregation which

violates the fourteenth amendment. It does this by link

ing state court jurisdiction rigidly to federal court juris

diction, even though the lower federal courts can have

their jurisdiction curtailed in certain instances by Con

gress pursuant to article III of the Constitution. This

“ linkage” is a dangerous and unconstitutional encroach

ment on the fundamental principle of due process that

state courts of general jurisdiction may not have their

jurisdiction narrowed if the consequence is the denial of

any meaningful remedy for the vindication of a federal

right.

Finally, amici submit that the Court of Appeal im

properly decided the question whether the Los Angeles

public school system is segregated in violation of the

fourteenth amendment. In 1970, the trial court gave

focused attention to this issue and concluded that the

segregation of the Los Angeles public schools was de

jure. This finding was accepted by the California Su

preme Court in 1976. Nevertheless, the court below de

clared that the law had changed since that time and,

relying upon its reading of subsidiary factfinding by the

trial court in 1970, it overruled the earlier holdings.

If the Court of Appeal felt it necessary to reopen the

question of de jure segregation in Los Angeles, it should

at the least have examined the record rather than merely

reviewed the 1970 findings. Because the court below

incorrectly reached out to decide the issue, an appropriate

course for this Court to follow is to remand for addi

tional fact-finding and the application of current four

teenth amendment legal standards to an updated record.

ARGUMENT

I. PROPOSITION 1 MUST BE JUDGED IN THE HIS

TORICAL, CONTEXT OF LONGSTANDING OFFI

CIAL SUPPORT FOR SEGREGATION AND

DISCRIMINATION IN CALIFORNIA, WHICH RE

INFORCES, THE OTHER EVIDENCE SHOWING

THAT ITS PASSAGE WAS MOTIVATED BY

RACIAL ANIMUS AND AN INTENT TO DISCRIM

INATE

It has long been this Court’s view that in cases chal

lenging state legislation or official action as racially dis

criminatory, the historical context is an important evi

dentiary factor to be weighed. Village of Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Homing Development Corp.,

429 U.S. 252, 267 (1977) ; Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S.

369, 373 (1967), and cases cited therein. The historical

context of Proposition 1 compels the conclusion that its

passage was intended to, and did, accomplish the racially

motivated purpose of returning minority children in

Los Angeles and throughout the State of California to

segregated schools, just as a similar historical context

caused this Court in Reitman to strike down another

California voter initiative, Proposition 14. Although the

Court of Appeal failed to take this background into ac

count in assessing the validity of Proposition 1 (see Ar

gument II infra), much of its outline is established by

materials subject to judicial notice.

Amici agree fully with the petitioners that evaluation

of the other factors specified by this Court’s decision in

Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266-68, leads to the

inevitable judgment that Proposition 1 intentionally dis

criminates against minority students in California. In

this section of our brief, we assemble, for the Court’s

additional consideration, significant indicia of the histori

cal context surrounding Proposition 1.

The historical record demonstrates a longstanding, un

wavering pattern of governmental support for— or out-

6

right compulsion of— racial segregation and discrimina

tion in every area, including public education. To the

extent that the actions of the California Legislature,

courts, or Department of Education began to reflect any

different attitude, the voters of the state have consistently

sought to return to a prosegregation, racially discrimi

natory public policy. For example, this Court noted in

Reitmxm, 387 U.S. at 374, that the historical background

of Proposition 14 included a 1961 legislative measure

that outlawed racially restrictive covenants. That legis

lative measure was significant because California citi

zens had long used such covenants to segregate racial

minorities, and California courts had consistently en

forced them. See Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary,

181 Cal. 680, 186 P. 596 (1919). When California voters

rose up to undo this legislative progress by passing

Proposition 14, the inference of racial motivation behind

the initiative was compelling. Similarly, Proposition 1

represents but the latest in a series of attempts by the

California electorate to overturn antidiscrimination steps

taken by any branch of state government, and to pre

serve school segregation.

For the Court’s convenience, we sketch the contours of

the historical record in tabular form at the end of this

section of the brief, at 8-11, infra, and summarize it here

as follows:

Although California was not admitted to the Union

as a slave state, within a few years its Legislature

prohibited racially mixed schools, banned Negroes from

testifying in judicial proceedings involving whites, and

excluded blacks and Chinese individuals from public of

fice. The state’s official policy of racial separation and

white supremacy continued unabated well into the twen

tieth century and was sensitive to every shift in popu

lar prejudice. For example, legislation mandating sepa

rate schools was enacted in 1885 for Chinese children, in

1909 for Indian children, and in 1921 for Japanese

children.

7

State officials enforced and encouraged white suprema

cist beliefs and the practice of racial segregation. In

1867, a year before California refused to ratify the

fourteenth amendment, the Governor urged racial separa

tion and specifically noted the operation of separate

schools for “ colored” children in the State. As indicated

above, the California courts consistently enforced racially

restrictive covenants by which housing patterns were kept

segregated. By the 1930’s California school district offi

cials had developed techniques for maintaining segre

gated schools by selecting sites deep in racially homogene

ous neighborhoods, and in 1953 the California Attorney

General’s Office frankly informed this Court that school

district attendance zone boundaries were often gerry

mandered for racial reasons. Despite early enactment

of a civil rights measure, public accommodations re

mained largely segregated until the relatively recent

past.

Efforts by the California Legislature and courts in

the 1960’s and 1970’s to alter the state’s traditional

public policy to achieve greater equality of opportunity

in the sensitive areas of housing and education were

greeted with resistance and defiance. As noted above,

Proposition 14 attempted to nullify statutory fair hous

ing measures, and both the California Supreme Court

and this Court found the initiative invidiously discrimi

natory and unconstitutional in Reitman. A subsequent

legislative measure and a separate initiative, both de

signed to prevent school integration, were declared un

constitutional by the California Supreme Court, in one in

stance, and construed to avoid a declaration of uncon

stitutionality, in the other. Finally, the intentions of

Proposition l ’s supporters are illuminated by the action

of its sponsor, after its passage, in initiating legislation

(vetoed by the Governor) which would have instructed

California courts applying federal decisional law under

Proposition 1 to ignore this Court’s constitutional hold

ings in Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S.

8

449 (1979) and Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman,

443 U.S. 526 (1979), because they were viewed as too

favorable to school desegregation.

In sum, the historical context of Proposition 1 places

the measure squarely within a long tradition of state

policies to further racial separation and discrimination.

Like the other evidence discussed by the petitioners, it

points to the conclusion that Proposition 1 is invidiously

discriminatory. The Court below erred in sustaining its

constitutionality and applying it to this case.

Historical Overview of Discrimination in California

1849 California admitted to the Union.

First California Constitution limits suffrage and legis

lative office to white males.3

1850 First California Legislature passes anti-miscegenation

statute.4 *

First California Legislature enacts measures to prohibit

giving of testimony by non-whites (defined as those

having 1/8 or more non-white blood) in judicial cases

involving whites.6

1854 Separate schools for black pupils established in Sacra

mento and San Francisco; state law provides for school

census only of white children and apportionment of state

school funds based upon census only of white children.6

1863 California Legislature enacts law requiring the creation

of separate schools for non-white pupils by local dis

tricts.7

3 Cal. Const., art. II, §106; art. IV, § 116 (1849).

4 1850 Cal. Stats., ch. 140, at 424.

6 1850 Cal. Stats., ch. 99, § 14, at 230; ch. 142, § 306, at 455.

6 B. Beams & P. W ilson, Segregation and the Fourteenth

A mendment in the States: A Survey of State Segregation

Laws 1865-1953; Prepared for United States Supreme Court

in r e : Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka 40-41 (1975)

[hereinafter cited as Reams & W ilson].

7 Act of April 6, 1863, Cal. Stats,, ch. 159, § 68, at 210. See also

Act of March 22, 1864, 1863-64 Cal. Stats., ch. 209, § 13, at 213;

Act of March 24, 1866, 1865-66 Cal. Stats, ch. 342, §§ 57-59, at

398; Act of April 4, 1870, 1867-70 Cal. Stats., ch. 556, § 56, at 838-

39; Cal. Pol. Code §§ 1662, 1669 (1872).

9

1865, California Governor, in address to Legislature, notes

1867 existence of separate schools for non-white children in

State.8 *

1868 California Legislature refuses to ratify fourteenth

amendment.

1874 Segregation of black students upheld by California

Supreme Court.8

1880 California Legislature repeals statutes requiring school

segregation.10

1885 California Supreme Court orders admission of Chinese

student to white school in San Francisco.11

California Legislature, in reaction to' decision, reenacts

school segregation statute to apply to “ Mongolian and

Chinese” students, preventing admission of child.12

1886 Supreme Court of United States rules that San Francisco

authorities discriminated against Chinese in administra

tion of laundry ordinance.13

1902 Segregation of Chinese students upheld in federal court.14 15

1909 California Legislature amends Education Code to au

thorize separate' schools, for Indian students.16

1919 California Supreme Court enforces racially restrictive

covenants.16

1921 California Legislature amends Education Code to require

separate schools for Japanese Children.17

8 Reams & W ilson at 34; 1867-68 Cal. State Journal 32.

8 Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36 (1874).

10 Act of April 7, 1880, 1880 Cal. Stat. Amend., at 47.

11 Tape v. Hurley, 66 Cal. 473, 6 P. 129 (1885).

12 Reams & W ilson, at 42-43; Wysinger v. Crookshank, 82 Cal.

588, 23 P. 54 (1890).

13 Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

14 Wong Him v. Callahan, 119 F. 38 (C.C.N.D. Cal. 1902).

15 Reams & W ilson, at 42-43; see Piper v. Big Pine School Hist.,

193 Cal. 664, 226 P. 926 (1924).

16 Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680, 186 P. 596

(1919).

17 Reams & W ilson, at 42-43.

10

1925 California Supreme Court upholds separate school re

quirement for Indian pupils.18 * * 21 22 *

1933 Los Angeles school district segregates Mexican-American

children by site selection and school construction policies.1®

1934-70 Pasadena school district officials use numerous devices

to maintain racial segregation in the schools.30

1936-40, School construction, attendance zoning, racial assignment

1960-70 and within-sehool segregation used by Oxnard School

District officials to isolate Mexican-American pupils.21

1942 Widespread racial and ethnic segregation found by Los

Angeles, sheriff to affect public life.22

1947 Los Angeles County Counsel defends anti-miscegenation

law on grounds that “ Negroes are socially inferior and

have so been judicially recognized.” 38

18 Piper v. Big Pine School Dist., 193 Cal. 664, 226 P. 926 (1924).

The Co-urt held that state school authorities were responsible

for providing a “ separate but equal” education for Indian students

even in districts in which Indian children could attend federal

institutions.

10 A Los Angeles district official reported:

[0]ur educational theory does not make any racial distinction

between Mexican and native white population. However, pres

sure from white residents of certain sections forced a modifica

tion of this principle to the extent that certain neighborhood

schools have been forced to absorb the majority of Mexican

pupils of the district.

Reynolds, The Education of Spanish Speaking Children in Five

Southwestern States, 1933 U.S. Office of Education Bulletin

No. 11, quoted in C. W ollenberg, All Deliberate Speed: Segre

gation and Exclusion in California Schools, 1855-1975 112

(1976).

30 Spangler v. Pasadena City School Dist., 311 F. Supp. 501

(C.D. Cal. 1970).

21 Soria v. Oxnard School Dist. Bd. of Trustees, 386 F. Supp. 539

(C.D. Cal. 1974).

22 1942 report of Los Angeles County Sheriff noting segregation

and exclusion in “ swimming plunges, public parks and even in

schools” as well as theaters and restaurants, quoted in I. Hendrick,

T he Education of Non-W hites in California 1849-1970 99

n.5 (1977).

28 Perez v. Sharp, 32 Cal. 2d 711, 727, 198 P.2d 17, 26-27 (1947).

11

1953 California Attorney General advises Supreme Court of

the United States that racial segregation of students is

practiced by some school districts in State.24

1957 Survey finds widespread segregation in public accom

modations despite state civil rights law.25

1959-69 School construction and gerrymandering of attendance

zone boundaries used to segregate schools in Richmond

school district.26

1964 Voters adopt Proposition 14 for purpose of repealing fair

housing laws and protecting right of landlords to dis

criminate on grounds of race.27 28 29

1970 California Legislature adopts Wakefield amendment to

Education Code for purpose of prohibiting use of trans

portation for school integration; later construed as in

effective so as to avoid constitutional question.38

1972 Voters adopt Proposition 21 to rescind State1 Education

Department policy favoring elimination of racial imbal

ance and to prevent assignment on racial basis to over

come segregation; held unconstitutional.39

1979 Following passage of Proposition 1 by California voters,

Legislature passes measure to limit incorporation of fed

eral standards deemed too favorable to litigants seeking

desegregation.310

24 Reams & W ilson, at 47.

35 “ . . . ‘after having a civil rights law for 50 years . . .’ less

than 20 percent of California’s hotels and motels will accommodate

Negroes,” Chicago Defender, April 27, 1957, at 20.

26 Johnson v. Richmond Unified School Dist., No. 112094 (Super.

Ct., Contra Costa County, April 3, 1972).

27 Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967).

28 San Francisco Unified School Dist. v. Johnson, 3 Cal. 3d 937,

479 P.2d 669, 92 Cal. Rptr. 309, cert, denied sub nom. Fehlhaber

v. San Francisco Unified School Dist., 401 U.S. 1012 (1971).

29 Santa Barbara School Dist. v. Superior Ct., 13 Cal. 3d 315,

530 P.2d 605, 18 Cal. Rptr. 637 (1975).

39 See Comment, Proposition 1 and Federal Protection of State

Constitutional Rights, 75 Nw. U.L. Rev. 685, 704-05 n.120 (1980) ;

Note, California’s Anti-Busing Amendment: A Perspective on the

Now Unequal Equal Protection Clause, 10 Golden Gate U.L. Rev.

611, 666 n.251 (1980).

12

II. WHILE THERE IS ENOUGH EVIDENCE IN THE

EXISTING RECORD TO SHOW PROPOSITION 1 IS

UNCONSTITUTIONAL, THERE IS NOT ENOUGH

EVIDENCE TO SUSTAIN ITS CONSTITUTION

ALITY

In the first section of this brief we outlined how

Proposition 1 grew out of California’s long history of

racial and ethnic discrimination. The immediate history

of Proposition 1 reveals that it is intended to deprive

state courts of the means to aid minority children who

seek to enforce their right to attend desegregated schools.

We believe that the facts in this case, illuminated by the

history of Proposition 1, compel the conclusion that

Proposition 1 is unconstitutional. If this Court is dis

posed to give consideration to the possible validity of the

initiative, however, it should do so only after remanding

the case for further factual development in the trial

court.

In determining the validity of a measure like Proposi

tion 1, which purports to be racially neutral, the Court

must inquire not merely whether it denies minority stu

dents the equal protection of the laws by its express

terms, but also whether this protection is denied “ in

substance and effect.” Without such an inquiry, “ a re

view by this Court would fail in safeguarding constitu

tional rights.” Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 589-

90 (1935) (Hughes, C.J.). The Court cannot make this

essential inquiry, however, unless all parties have had

an opportunity to present relevant evidence, and the

Court has before it a complete record developed in the

trial court. Important and difficult constitutional issues

cannot and should not be decided in the absence of an

adequate factual record. Time, Inc. v. Firestone, 424

U.S. 448, 461-63 (1976) ; W.E.B. DuBois Clubs v. Clark,

389 U.S. 309, 312 (1967).

In this case, the factual record necessary to support

the decision of the Court of Appeal is entirely lacking.

The trial court did not reach the issue of the constitu

13

tionality of Proposition 1 and rested its decision for

plaintiff on other grounds. Accordingly, the subsequent

decision of the Court of Appeal that Proposition 1 is

constitutional is entirely unsupported by any findings of

fact with respect to the history of Proposition 1, its

objectives, or its impact on the plaintiffs in this case.

Rather, the Court of Appeal validated Proposition 1 by

relying on the brief and self-serving statement of legis

lative purpose appended to the measure, by indulging the

negative presumption that the legislators who wrote and

the voters who adopted Proposition 1 “ could have been

motivated without segregative intent and discriminatory

purpose,” and by characterizing arguments to the con

trary as “pure speculation,” even though petitioners had

never had their full day in court on the issue of intent.

113 Cal. App. 3d at 654-55, 170 Cal. Rptr. at 509.

This Court should not permit this unsupported decision

to stand. Instead it should remand the case for an ex

amination of these essential questions in the trial court.

If the Court does not do this, not just these petitioners,

but all minority children attending illegally segregated

schools in California will have had their right to an

effective remedy decided without an opportunity for

meaningful judicial review.

The decisions of this Court in Washington v. Davis, 426

U.S. 229, 239 (1976), Arlington Heights, supra, and Per

sonnel Administrator v. Feeney, 432 U.S. 256 (1979), es

tablish that in considering the validity of a purportedly

neutral state constitutional amendment, like Proposition

1, an evaluation of all circumstantial and direct evidence

of purpose is essential. The starting point for this inquiry

is “ the impact of the official action— whether it bears more

heavily on one race than another.” Sometimes impact

alone may present so stark a picture of racial discrimina

tion that no further inquiry is necessary. If impact alone

is not clearly determinative of intent, however, the court

must go on to examine other evidence, including evidence

of the immediate and long-range procedural and substan

tive history of the challenged action. Arlington Heights,

429 U.S. at 266-268.

A. The Constitutionality of Proposition 1 Cannot be

Upheld Without an Examination of Its Impact

on Minority Students

In its haste to affirm the constitutionality of Proposi

tion 1, the Court of Appeal failed to take even the first

step in this essential analysis of purpose. The Court of

Appeal refused to make any meaningful evaluation of the

effect of Proposition 1 on minority children. Instead, that

court simply looked at the text of Proposition 1, and

blithely concluded that “all the amendment does is remove

from the court the remedy of pupil school assignment and

pupil transportation as one among scores of remedies

available for use by a court to end racial isolation.”

Crawford v. Board of Education (“ Crawford II” ), 113

Cal. App. 3d at 655-656, 170 Cal. Rptr. at 510. The court

made no attempt to evaluate which of those “scores of

remedies” could be effectively applied to existing condi

tions in the Los Angeles Unified School District or, indeed,

to identify even one such remaining “ remedy.” In fact,

the Court of Appeal made no determination as to whether

Proposition 1 would leave the state courts with any effec

tive means to alleviate segregation.

The California Supreme Court in Crawford v. Board of

Education (“ Crawford I” ) identified the basic tools for

accomplishing desegregation— redrawing neighborhood at

tendance zones, “pairing” or “ clustering” of schools, estab

lishment of “magnet schools” and implementation of “ sat

ellite zoning.” Crawford I, 17 Cal. 3d 280, 305, 551 P.2d

28, 44, 130 Cal. Rptr. 724, 740 (1976). Every one of these

techniques requires pupil assignment or pupil transporta

tion. Indeed, effective desegregation of necessity almost

always requires some form of pupil assignment or pupil

transportation. It is the role of the school board in man

dating school assignment and transportation that forms

the predicate for its obligation to desegregate its schools,

14

and makes judicial review of its performance of that obli

gation so essential.

Although the trial court did not reach the issue, the rec

ord in this case illustrates how Proposition 1 will prevent

California courts from ordering any effective remedy for

segregation. The Los Angeles School Board refused

even to provide transportation for voluntary transfers

until ordered to do so by the trial court. (1970

Findings, If IV.48) :31 The court-ordered desegregation

plan which led to this appeal included a mix of the tech

niques indentified by the California Supreme Court, in

cluding “pairing,” “ cluster schools,” “magnet schools,”

and the continuation of voluntary transfers with trans

portation. The plan also required the assignment of non-

English-speaking Hispanic pupils in groupings which

would facilitate bilingual education and ended the practice

of assigning non-English-speaking Hispanic students to

programs for lower-achieving students. This entire plan

would be prohibited by Proposition 1. (Order After Trial

Upon Plan II and the Proposed All-Voluntary Program).

Indeed, all the evidence of impact available in the rec

ord suggests petitioners will be denied any remedy at all

if Proposition 1 is upheld. In 1970 the trial court con

cluded that the Los Angeles school board would not deseg

regate its schools unless compelled to do so. (1970 Find-

ings, If IV.47, IV.54, IV.55). Ten years later that court

found that the Los Angeles Board still “did not have a

course of action designed to make meaningful progress in

15

31 As noted by this Court, “ Provision for optional transfer of

those in the majority racial group of a particular school to other

schools where they will be in the minority is an indispensible

remedy for those students willing tio transfer to other schools in

order to lessen the impact on them of the state-imposed stigma of

segregation. In order to be effective, such a transfer arrangement

must grant the transferring student free transportation and space

must be made available in the school to which he desires to move.”

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1,

26-27 (1971). (emphasis added.)

16

the elimination of harms arising out of minority segre

gated schools and that [even then] the Board had not

. . . resolved itself to achieve any such plan.” (Opinion,

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law after Hearing

R e: Sufficiency of the Response by Respondent to the Ex

isting Writ of Mandate and to the Order Issued Pre

viously [hereinafter, “July 7 Order” ] at 3). Moreover, the

court specifically concluded that the “all voluntary” pro

gram the board proposed to implement, if permitted to do

so by the court, would not desegregate any minority

schools and reflected a lack of concern for minority stu

dents. (July 7 Order, at 4-5.)

This, with other evidence that can be adduced on re

mand, will establish that the legislators who proposed and

the voters who adopted Proposition 1 knew and intended

that it would do more than just regulate one “ remedy”—

it would effectively destroy any meaningful chance for the

minority children in Los Angeles to challenge the school

system in which they have been segregated in overcrowded

schools with inferior teachers, curriculum, and physical

facilities. Crawford II, 113 Cal. App. 3d at 643, 170 Cal.

Rptr. at 501. This sort of predicted and planned disparate

impact on minorities is central to assessing the constitu

tionality of Proposition 1, and it may be considered only

if the action is remanded for that purpose.

B. The Constitutionality of Proposition 1 Cannot be

Upheld Without an Examination of Its Historical

Background

Even a superficial review of the history of Proposition

1 contained in the existing record, made in light of the

standards established in Reitman, discloses sufficient in

dicia of discriminatory purpose to demonstrate that fur

ther examination of this history is essential before reach

ing any final determination that Proposition 1 does not

deny minority students their federally guaranteed right to

the equal protection of the laws.

This action was initiated in 1963. In 1970, the trial

court first ordered the desegregation of the Los Angeles

17

school system. (July 7 Order, at 6-14.) That same year,

legislation requiring parental consent before a child could

be bused to school was added to the California Education

Code.82 In 1972, the Education Code was amended to for

bid student assignment on the basis of race.83 The Cali

fornia Supreme Court determined that neither statute

could be constitionally applied to prevent or impede deseg

regation. San Francisco Unified School District v. John<-

son, 3 Cal. 3d 937, 479 P.2d 669, 92 Cal. Rptr. 309, cert,

denied sub nom. Fehlhaber v. San Francisco Unified

School District, 401 U.S. 1012 (1971); Santa Barbara

School District v. Superior Court, 13 Cal. 3d 315, 530

P.2d 605, 18 Cal. Rptr. 637 (1975).

In the meantime, the Los Angeles Board exercised

every means it had to resist the order to desegregate.

Indeed, the first mandatory desegregation plan was not

implemented until 1978. Only a year later, when Proposi

tion 1 was passed, the Board immediately sought to uti

lize the constitutional amendment to abandon any mean

ingful desegregation. (July 7 Order, at 6-14, 96-96).

These facts form the outline. A full evaluation of the

facts on remand would establish that Proposition 1 is the

culmination of a twenty-year campaign by the Board of

Education and its political allies throughout the state to

evade its statutory and constitutional obligation to provide

desegregated education in California and to insulate this

gross breach of duty from meaningful judicial review.

See Comment, Proposition 1 and Federal Protection of

State Constitutional Rights, 75 Nw. U.L. Rev. 685, 690-

693 (1980) ; Note, California's Anti-Busing Amendment:

A Perspective on the Now Unequal Equal Protection

Clause, 10 Golden Gate U.L. Rev. 611, 669-681 (1980). * 33

Cal. Educ. Code § 1009.5 (1970) (currently Cal. Educ. Code

§ 35350 (1978) (W est)).

33 cal . Educ. Code § 1009.6 (1972) (currently Cal. Educ. Code

§35351 (1978) (W est))-

18

We believe that the sensitive evaluation of the evidence

mandated by this Court in Arlington Heights would dem

onstrate that the true purpose of Proposition 1 was to as

sist recalcitrant school boards in California, like the Los

Angeles school board here, to evade their obligations to

minority students and to maintain and perpetuate racial

and ethnic separation in the schools free from unwelcome

judicial review. The available history, at the very least,

establishes a sufficient likelihood that Proposition 1 was

enacted with this discriminatory intent to preclude any

conclusion that it is constitutional on its face. It is there

fore essential for this Court to remand this case for an

examination in the trial court of the impact, and the ob

jectives, of Proposition 1 in light of its historical con

text and the conditions existing prior to its enactment.

III. PROPOSITION 1 IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL BE

CAUSE IT DENIES THE POWER OF STATE

COURTS OF GENERAL JURISDICTION TO GIVE

REMEDIES WHICH ARE NECESSARY TO RE

DRESS CERTAIN FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

VIOLATIONS, IN CASES WHERE CONGRESS

M AY ATTEMPT TO CURTAIL LOWER FEDERAL

COURT JURISDICTION

For the reasons set forth below, amici submit that a

state may not restrict the remedies which its courts may

provide in suits involving federal constitutional violations.34

This principle applies not only when the limitations on

remedy are imposed directly, but also when the authority

of state courts is circumscribed by making them subject

to the same restraints as are the lower federal courts.

Proposition 1 has precisely this prohibited effect. As a

matter of fundamental California law, subject to altera

tion only through the tortuous process of constitutional

34 Such findings have been made by trial courts in this and other

California school segregation actions. E.g., Crawford v. Board of

Educ., 17 Cal. 3d 280, 288-289, 551 P.2d 28, 32-33, 130 Cal. Rptr.

724, 728-729 (1976) ; Johnson v. Richmond Unified School Dist.,

No. 112094 (Super. Ct., Contra Costa County, April 3, 1972).

19

amendment, it reduces the authority of state courts in all

school segregation action pro tanto with the authority of

the lower federal courts. The availability of a remedy to

effectuate the right to a non-segregated education thus

will vary both with shifts in federal decisional law, and

also with any legitimate exercise of Congress’ authority to

regulate the jurisdiction of— or even to eliminate entire

ly— the lower federal courts. Even more significant, the

availability of necessary remedies in fourteenth amend

ment school desegregation suits in California courts will

be called into question while the federal constitutionality

of subject-specific jurisdictional limitation measures is lit

igated. See, e.g., Sager, The Supreme Court, 1980 Term

—Foreword: Constitutional Limitations on Congress’ Au

thority to Regulate the Jurisdiction of the Federal Courts,

95 Harv. L. Rev. 17 (1981) (hereinafter, “ Sager” ) ;

Tribe, Jurisdictional Gerrymandering: Zoning Disfavored

Rights Out of the Federal Courts, 16 Harv. C.R.— C.L.

L. Rev. 129 (1981) (hereinafter, “ Tribe” ).

A. As Courts of General Jurisdiction, State Courts

May Not Be Limited in Their Ability to Impose

Necessary Remedies for Federal Constitutional

Violations

It was part of the plan of the Constitution that state

courts of general jurisdiction would act as the final line of

defense against unconstitutional government— both state

and federal— in cases where the lower federal courts had

not been given jurisdiction by Congress, or where their

limited subject matter jurisdiction had been narrowed

by permissible congressional regulation. See P. Bator,

P. Mishkin, D. Shapiro & H. Wechsler, Hart &

W echsler’s The Federal Courts and the Federal

System 11-12 (2d ed. 1973) ; Warren, New Light on

the History of the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789, 37

Harv. L. Rev. 49, 53 (1923). Proposition 1 rigidly ties

the power of state courts to give constitutionally neces

sary remedies to the power of federal courts to do so:

a linkage that may seem innocuous until it is evaluated

in the context of (a) the constitutional grant of some

20

measure of control over federal court jurisdiction to

Congress,35 * * and (b) the current interest on the part of

some members of Congress to use that control to limit

the remedies which federal courts may award in suits

to enforce constitutional rights,38 including remedies nec

essary to eliminate unconstitutional dual school systems.

Of course, there are limits on Congress’ powers to restrict

federal court jurisdiction, for those powers must be

exercised in harmony with other provisions of the Con

stitution. Sager, supra at 37-42. The same limits apply

to restrictions on state court jurisdiction to adjudicate

and redress claims of federal constitutional right, in light

of the supremacy clause and the fundamental role of

state courts in the constitutional scheme.

For instance, Congress may not withdraw jurisdiction

from a federal court in a way that infringes the legiti

mate constitutional powers of the Executive Branch of

government, or requires a federal court to find facts

which are untrue to be true. See United States v. Klein,

80 U.S. (13 Wall.) 128 (1872). Another principle that

neither Congress nor the states can violate in the guise

of regulating jurisdiction is that for every violation of

the federal Constitution some court must have jurisdic

tion to give those remedies which are necessary to re

dress the wrong. See, e.g., Guam v. Olsen, 431 U.S. 195,

204 (1977) ; Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S. 361, 366

(1974) ; Yakus v. United States, 321 U.S. 414, 444

(1944) ; see also Sager, supra, at 41 n.70, 75-76 & n.183.

Professor Hart put the matter succinctly when he wrote:

85 Article III, §1 states, in part: “The judicial Power of the

United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such

inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and

establish.” See Palmore v. United States, 411 U.S. 389, 400-01

(1973) ; Sheldon v. Sill, 49 U.S. (8 How.) 441, 449 (1850) ;

C. Wright, The Law of Federal Courts § 10, at 29 (3d ed. 1976).

The proposition that the lower federal courts could today be elimi

nated or severely restricted in their authority has been questioned.

See, e.g., Eisenberg, Congressional Authority to Restrict Lower

Federal Court Jurisdiction, 83 Yale L.J. 498 (1974).

36 See discussion infra at 24-25 and n.39.

21

“ a necessary postulate of constitutional government [is]

that a court must always be available to pass on claims

of constitutional right to judicial process, and to pro

vide such process if the claim is sustained.” Hart, The

Power of Congress to Limit the Jurisdiction of Federal

Courts: An Exercise in Dialectic, 66 Harv. L, Rev.

1362, 1372 (1953).

This postulate binds state legislators and other state

law-making authorities no less than Congress. The states

may not restrict the jurisdiction of their own courts to

give remedies which are required to vindicate federal

rights. See Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396

U.S. 229, 238-39 (1969) (state court must grant injunc

tions appropriate to the enforcement of federal civil

rights “ if that court is empowered to grant injunctive

relief generally” ) ; Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1947)

(supremacy clause requires state court to assume juris

diction over a suit brought under federal price control

legislation). This is especially true when the jurisdic

tion of federal courts has been curtailed by Congress

or by the unique limits on the federal judicial power

contained in the Constitution. See, e.g., General Oil Co.

v. Crain, 209 U.S. 211, 226 (1908) (disregarding as

unconstitutional a state statute making state officers im

mune from suit in state courts where it is assumed

that “ suit against state officers is precluded in the na

tional courts by the Eleventh Amendment” ) ; cf. Maine

v. Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1, 11 & n.12 (1980) (supremacy

clause requires state courts to give attorneys’ fees

award in civil rights action which was beyond the juris

diction of a federal district court).

Indeed, the powers which Congress does have to con

trol the jurisdiction of federal courts, and the remedies

they may give, can be justified, if at all, only by the

mandatory availability of state courts to give those same

remedies where indispensable to the vindication of fed

eral rights. The Norris-LaGuardia Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 101-

15 (1976), for instance, withdraws the jurisdiction of

federal courts to issue injunctive remedies in “ a case

22

involving or growing out of a labor dispute.” In Lauf

v. E.G. Skinner & Co., 303 U.S. 323, 330 (1938), the

Court sustained the constitutionality of the Norris-

LaGuardia Act, based upon Congress’ broad authority to

regulate federal court jurisdiction. However, the Court

did so in light of and without limiting the force of its

earlier holding in Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U.S. 312

(1921), that the due process and equal protection clauses

of the fourteenth amendment prohibited similar state

legislation restricting the jurisdiction of state courts to

give injunctions in certain labor disputes. See also

H.R. Rep, No. 669, 72d Cong., 1st Sess. 10 (1932).

As the Truax Court observed, “ [i]t is beside the

point to say that plaintiffs had no vested right in

equity relief, and that taking it away does not de

prive them of due process of law.” 257 U.S. at 334.

Whatever the merits of a plaintiff’s claim to injunctive

relief in a labor dispute may be, Truax establishes that

at the very least a state court must stand ready to en

tertain his application for it, give him a fair hearing,

and grant the remedy where appropriate.

Anything less means that for some constitutional vio

lations by state and federal governments, the victim may

not obtain any judicial review and relief: a proposition

abhorrent to any legal system dedicated to the rule of

law. See Battaglia v. General Motors Corp., 169 F.2d

254, 257 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 335 U.S. 887 (1948).

That federal courts may be powerless to act in such a

case reinforces rather than detracts from the duty of

state courts to assume jurisdiction. See Maine v. Thibout-

ot, 448 U.S. at 11 n.12.

B. In Violation of Due Process of Law, Proposition 1

Unconstitutionally Links State Court Jurisdiction

to Give Necessary Remedies to Limits on Federal

Court Jurisdiction

Proposition 1 states, in pertinent part, that “ pupil

school assignment” and “ pupil transportation” remedies

may not be used by California state courts:

(1) except to remedy a specific violation by such

party that would also constitute a violation of the

Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to

the United States Constitution, and (2) unless a fed

eral court would be permitted under federal de

cisional law to impose that obligation or responsi

bility upon such party to remedy the specific viola

tion of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th

amendment of the United States Constitution, (em

phasis added.)

This provision has been construed by the state courts

to make their jurisdiction in fourteenth amendment cases

turn on what a federal court could do in a similar case.

For instance, Judge Cohn of the San Mateo County

Superior Court has observed:

Turning to the argument that Proposition 1 vio

lates the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution,

inasmuch as it merely limits California courts to

what the federal courts can do under the federal

constitution, it is indeed difficult to accept the con

tention that by limiting a state court’s jurisdiction to

that of federal courts there is somehow a violation

of [the] federal constitution.

Tinsley v. Palo Alto Unified School District, No. 206010

(July 10, 1980), quoted in Board, of Education v. Superior

Court, 448 U.S. 1343, 1345 (1980) (Rehnquist, Circuit

Justice). Likewise, the Court of Appeal in this case

characterized the effect of Proposition 1 as follows:

The effect of the amendment was to prohibit state

courts, in desegregation cases, from ordering school

boards to mandatorily reassign and transport pupils

on the basis of race, except to remedy a violation of

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution under cir

cumstances which would authorize a federal court

under federal decisional law to issue such an order.

113 Cal. App. 3d 633, 636-37, 170 Cal. Rptr. 495, 497-

98 (emphasis added). As this passage shows, Proposition

1 concerns itself with all “ desegregation cases,” whether

24

they arise under the state or the federal constitutions.

On its face, the measure restricts the power of California

state courts in all such cases to issue only those constitu

tional remedies which “ a federal court would be per

mitted under federal decisional law to impose.”

This Court’s decisions establish squarely that “pupil

transportation” and “ pupil school assignment” remedies

may be necessary, and hence mandatory, to remedy cer

tain fourteenth amendment violations. See North Carolina

State Board of Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971) ;

Swarm v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971); cf. Wright v. Council of City of

Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972). Indeed, in this very case

the trial court determined that a comprehensive structural

remedy embodying these features was necessary on the

facts to remedy de jure segregation of the Los Angeles

public school system.®'7 Yet Proposition 1 might, if given

effect by this Court, eliminate the right of access of

minority litigants to such potentially essential remedies in

state courts, even though Congress had tried to strip

lower federal courts of their jurisdiction to give com

parable remedies. At the very least, under Proposition 1,

school segregation litigation in the California courts

would be disrupted by any congressional effort to restrict

the “busing” orders of the federal courts, whether those

efforts were ultimately determined to be constitutional

or not.

The threat of Congress attempting to withdraw federal

court jurisdiction to issue such remedies is very real. In

the past decade, numerous legislative proposals have

been made to curb the power of federal courts to use

busing as a remedy in school desegregation cases. See

e.g., G. Gunther, Cases and Materials on Constitu

tional Law 730-32 (9th ed. 1975) ; Goldberg, The Ad

ministration’s Anti-Busing Proposals— Politics Makes Bad

Law, 67 Nw. U.L. Rev . 319 (1972) ; Rotunda, Congres-

87 This factual conclusion was erroneously tossed aside by the

Court of Appeal, as we make clear in the last section of this brief.

25

sional Power to Restrict the Jurisdiction of the Lower

Federal Courts and the Problem of School Busing, 64 Geo.

L.J. 839 (1976). At least three such proposals— S. 1647,

S. 1743 and S. 1760— are indeed pending in the current

session of Congress, and at least one of these, the Hatch

Bill, S. 1760, has been reported out of subcommittee to

the full Senate Judiciary Committee.

All of these measures purport to rest upon Congress’

concededly broad power to regulate federal court ju

risdiction under article III of the Constitution. But see

Sager, supra, at 77-78 n. 187, 87; Tribe, supra. What

ever the precise scope of that power, it clearly does not

authorize either Congress or the states to deny the juris

diction of state courts to grant constitutionally necessary

remedies, as Proposition 1 appears to do if followed to its

logical conclusion.

This Court cannot sanction such a result if it is to be

faithful to the constitutional principle that some court,

state or federal, must always stand ready to bring re

calcitrant government into line with the commands of

the Constitution.38 Professor Hart correctly identified

what was at stake in a case such as this when he

answered the question of where a litigant can go to get a

remedy for a constitutional violation if Congress has shut

off access to the lower federal courts:

38 Although limitations on the power of the lower federal

courts to effectuate adequate remedies in school desegregation

cases have not yet been enacted (and although the validity of such

measures has not yet been determined), Proposition 1 is unconsti

tutional. Whatever the breadth of Congress’ authority to deter

mine how the fourteenth amendment shall be enforced, see Katzen-

bach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 654-56 (1966), for the reasons given

above, the states may not determine that vindication of fourteenth

amendment rights shall be the exclusive preserve of the federal

courts, and that state courts will meekly follow wherever federal

courts are led by Congress. Proposition 1 therefore oversteps the

limits of California’s legislative authority as of its passage, whether

or not objectionable restrictions upon federal court authority are

operative, and the measure is unconstitutional on its face.

26

The state courts. In the scheme of the Constitu

tion, they are primary guarantors of constitutional

rights, and in many cases they may be the ultimate

ones. If they were to fail, and if Congress had taken

away the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction and

been upheld in doing so, then we really would be

sunk.

Hart, The Power of Congress to Limit the Jurisdiction

of Federal Courts: An Exercise in Dialectic, supra, 66

Harv. L. Rev. at 1401.

This Court should hold that Proposition 1 is an un

constitutional attempt by the law-making authorities of

California to restrict the access of civil rights litigants

to remedies in state courts to redress federal constitu

tional violations,39

IV. IN DECIDING THAT THE SEGREGATION IN THE

LOS ANGELES PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM DOES

NOT VIOLATE THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

AS A MATTER OF LAW, THE COURT OF APPEAL

ERRONEOUSLY REVERSED THE TRIAL COURT

WHEN IT OUGHT TO HAVE OPENED THE REC

ORD FOR FURTHER FACTUAL INQUIRY

The history of this case is one of monumental effort

in the trial court. The original trial in the action lasted

for 65 days, involved the introduction of voluminous evi

dentiary material; and resulted in a reporter’s transcript

running to 62 volumes. Crawford I, 17 Cal. 3d at 287,

551 P.2d at 31, 130 Cal. Rptr. at 727. After the result

ing mandate for desegregation of the Los Angeles schools

39 There are now pending in the 97th Congress numerous other

proposals designed to restrict lower federal court, and Supreme

Court, jurisdiction in certain subject matter areas, E.g., S. 158

(abortion) ; S. 481 (school prayer) ; H.R. 865 (school prayer) ;

H.R. 867 (abortion) ; H.R. 72 (school prayer). If the Court upholds

Proposition 1 in this case, it is easy to see how state legislators

and electorates might try to avoid any judicial review at all in these

controversial areas by “ tying” state court jurisdiction to federal

court jurisdiction.

27

was affirmed by the California Supreme Court, in an

opinion which specifically accepted the lower court’s find

ing of de jure segregation,40 the trial court spent an ad

ditional three years monitoring the school board’s com

pliance with the mandate. In the course of that over

sight, the Court received over 420 written exhibits, con

ducted 170 days of hearing and examined the testimony

presenting the Board’s case on the results of its prior

plans, the reports of its own referee, the court-appointed

monitoring committee, and the reports of the court-

appointed experts (July 7, 1980 order, at 2-3). The

trial court then reaffirmed its original conclusion that

there was de jure segregation in the Los Angeles Uni

fied School District in violation of the fourteenth amend

ment. Accordingly, the trial court concluded that re

examination of the mandate for desegregation in light of

the enactment of Proposition 1 was unnecessary, and it

ordered the Board to proceed with desegregation.

The Court of Appeal reversed. In doing so, that court

confined its attention to the 1970 findings of the trial court

and determined that these findings had been made with

out the benefit of later opinions of this Court establishing

that the essence of unconstitutional, or “de jure,” segre

gation is “ the purpose or intent to segregate.” At that

point, the Court of Appeal should have remanded the case

to afford the trial court “ an opportunity to reexamine the

record on the issue of intent” and to “ permit the parties

to offer such additional evidence as they may desire per

taining to that issue.” Johnson v. San Francisco Unified

School District, 500 F.2d 349, 352 (9th Cir. 1974). In

stead, based solely on its review of the findings of the

1970 trial court, and without purporting to make any

independent evaluation of the evidence, the Court of Ap

peals made its own determination that the school segrega

40 Crawford I, 17 Cal. 3d at 301, 551 P.2d at 41, 130 Cal. Rptr.

at 737.

tion in Los Angeles was not the result of purposeful

discrimination.41

This analysis has obvious flaws. The Court of

Appeal improperly considered only the subsidiary factual

findings of the trial court in reaching its conclusion that

the segregation in the Los Angeles schools was not the

result of purposeful discrimination. It should have ex

amined the entire record of the trial—but that record

was not even before it on the appeal below. This is

particularly important since the trial court’s 1970 judg

ment was based in part on the state law affirmative duty

of the Los Angeles School Board to desegregate its schools.

See Crawford I, 17 Cal. 3d at 284-285, 551 P.2d at 39

130 Cal. Rptr. at 726. The trial court’s 1970 findings for

this reason did not exhaustively catalogue the facts of

record demonstrating that the segregated condition of

the Los Angeles school district originated with “ acts done

with specific segregative intent and discriminatory pur

pose.” Cf. Columbus, 443 U.S. at 466 n.14.42

41 To the extent that the decision below rejects the trial court’s

original findings, the action of the Court of Appeal was plainly in

error. A reviewing court cannot overturn the findings of fact of

the trial court without examination “ of the entire evidence.”

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395

(1948). Even if the Court of Appeal made such an examination,

however, it would still be barred from substituting its own infer

ences for those made by the trial court. Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazel-

tine Research, Inc., 395 U.S. 100, 123 (1969). This analysis is not

altered by the fact that the decision below was made in the

California Court of Appeal. The standard in the California Courts,

is, if anything, more stringent. Board of Educ. of Long Beach v.

Jack M., 19 Cal. 3d 691, 697, 566 P.2d 602, 605, 139 Cal. Rptr. 700,

703 (1977).

42 The trial court in this case limited its findings to the period

after 1963 when this lawsuit was initiated. There was no consider

ation whether the segregation in 1963 was an outgrowth of a

segregated “dual school system” prior to 1954. On remand, peti

tioners could establish that Los Angeles was indeed operating such

a dual system. See generally I. Hendrick, T he Education of Non-

W hites in California, 1849-1970 91-104 (1977).

28

29

The Court of Appeal also erred in its facile assump

tion that the Los Angeles District’s “maintenance of a

neighborhood school system, siting schools in the geo

graphic center of their need, assignment of pupils to

neighborhood schools, and failure to provide free trans

portation for open tranfers” were “ neutral acts.” Craw

ford II, 113 Cal. App. 3d at 644, 170 Cal. Rptr. at 502.

Any determination or decision that a “ neighborhood school

policy” is in fact neutral, and not a “ potent weapon for

creating or maintaining” racial segregation requires in

tensive factual scrutiny. Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-21;

Keyes v. School District No, 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189, 201-

02 (1973) ; id. at 234-35 (Powell, J., concurring). It may

also be necessary to extend the court’s inquiry to the rela

tionship between school segregation and residential segrega

tion since residential patterns themselves may be the prod

uct of an illegally segregated school system, or other uncon

stitutional state action. Columbus, 443 U.S. at 465 n.13;

Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-21; Keyes, 413 U.S. at 201-202;

Crawford I, 17 Cal. 3d at 299-300, 551 P.2d at 40, 130

Cal. Rptr. at 736-737.

As Justice Stewart has observed, the question whether

actions which produce racial separation are intentional,

within the meaning of the decisions of this Court, presents

difficult and subtle issues of fact. Columbus, 443 U.S.

at 470-71 (Stewart, J., concurring in the result).

This careful factual scrutiny required in evaluating

a claim of constitutional right was not provided by the

Court of Appeal’s summary conclusion that the trial court

erred, eleven years ago, in finding de jure segregation in

Los Angeles. But that summary conclusion by the Court

of Appeal was the predicate for its holding that Proposi

tion 1 must be applied in this case, and, further, that it

could be applied without violating petitioners’ rights under

the fourteenth amendment. Since this Court has granted

certiorari to review that holding, the manner in which the

court below decided the fundamental issue of federal con

30

stitutional law on which the questions presented in this