Wallace v. Kern Brief of Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wallace v. Kern Brief of Appellant, 1973. 98b91d60-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dbfabe70-1f89-4f8c-bc55-7d9b44604328/wallace-v-kern-brief-of-appellant. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

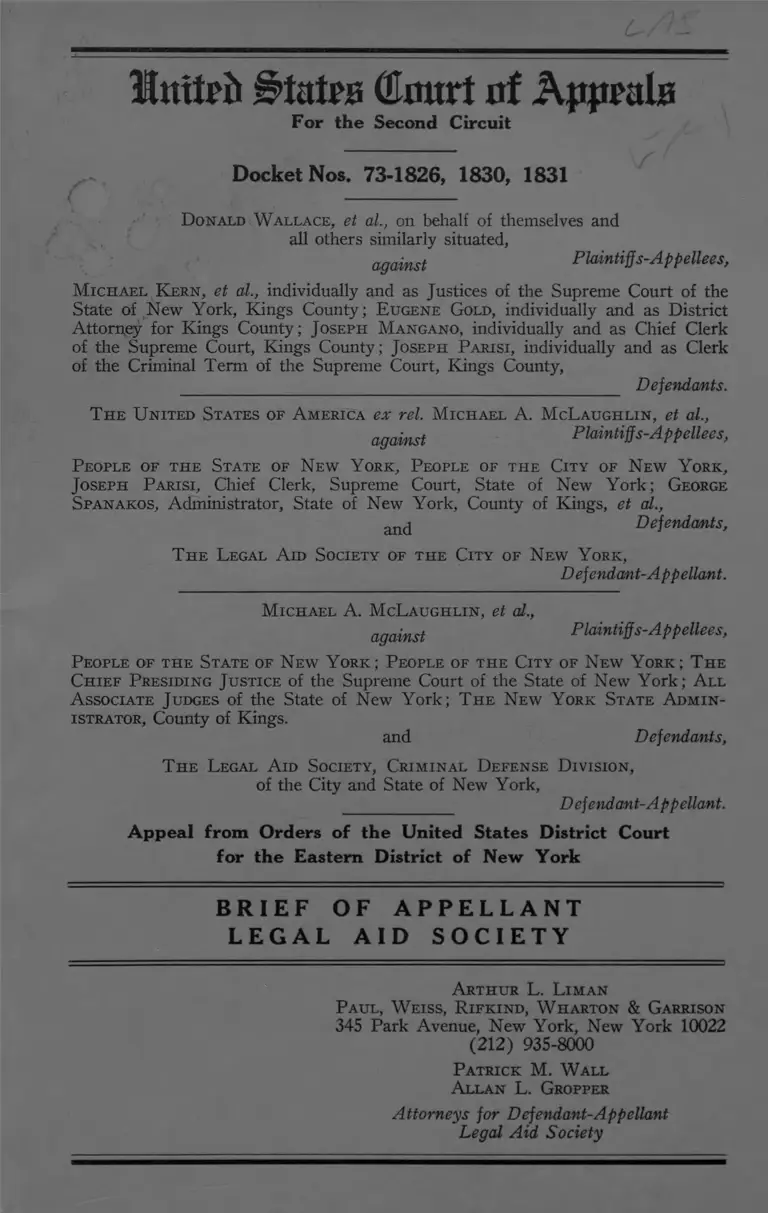

idatea dour! of Appeals

For the Second Circuit

Docket Nos. 73-1826, 1830, 1831

Donald W allace, et al., on behalf of themselves and

all others similarly situated,

against Plaintiffs-Appellees,

M ichael K ern, et al., individually and as Justices of the Supreme Court of the

State of New York, Kings County; E ugene Gold, individually and as District

Attorney for Kings County; Joseph M angano, individually and as Chief Clerk

of the Supreme Court, Kings County; Joseph Parisi, individually and as Clerk

of the Criminal Term of the Supreme Court, Kings County,

____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Defendants.

T he U nited States of A merica ex rel. M ichael A.

against

M cLaughlin, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

People of the State of N ew Y ork, People of the City of N ew Y ork,

Joseph Parisi, Chief Clerk, Supreme Court, State of New York; George

Spanakos, Administrator, State of New York, County of Kings, et al.,

a n j Defendants,

T he Legal A id Society of the City of N ew Y ork,

Defendant-Appellant.

M ichael A. M cLaughlin, et al.,

against Plaintiffs-Appellees,

People of the State of New Y ork ; People of the City of N ew Y ork ; T he

Chief Presiding Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of New York; A ll

A ssociate Judges of the State of New York; T he New Y ork State A dmin

istrator, County of Kings.

and Defendants,

T he Legal A id Society, Criminal Defense Division,

of the City and State of New York,

_______________________________________________________________________________________ Defeiidant-Appellant.

Appeal from Orders of the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of New York

B R I E F O F A P P E L L A N T

L E G A L A I D S O C I E T Y

A rthur L. L iman

Paul, W eiss, Rifkind, W harton & Garrison

345 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10022

(212) 935-8000

Patrick M. W all

A llan L. Gropper

Attorneys for Defendant-Appellant

Legal Aid Society

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

PAGE

Preliminary Statement ................................................... 1

The Issues Presented ..................................................... 4

Statement of Pacts ......................................................... 5

The Proceedings B elow ............................................... 5

The Wallace Action ................................................. 5

The McLaughlin Actions ....................................... 6

The Structure of the Criminal Courts in Kings

County .................................................................. 8

The Criminal Court ............................................. 8

The Supreme Court ............................................. 10

The Legal Aid Society............................................. 12

The Structure ....................................................... 12

Assignments of Criminal Cases to the Society 13

The Society’s Kings County Office .................... 15

The Crisis in Kings County Supreme Court ....... 16

The Society’s Efforts to Cope with the Crisis ..... 17

The Quality of the Society’s Services .................. 18

Caseload .................................................................... 19

The Opinion and Orders B elow ..................................... 21

Point I— The Legal Aid Society—“ a private institu

tion in no manner under State or City supervision

or control,” which performs a function “ nor

mally performed for and by private persons” —

does not act “ under color o

the meaning of Section 1983 27

11

Legal Defender Organizations, Which Owe Undi

vided Loyalty to Their Clients and Are, by

Their Very Nature, Adversary to the State,

Do Not Act “ Under Color of State Law” in

Representing Indigents—and Federal Courts

Have Repeatedly So Held .............................. 30

Point II—In fixing a caseload limitation for the So

ciety, the District Court applied an erroneous

constitutional standard and erred in translating it

mechanically into a numerical maximum.............. 36

Point III— The District Court erred in entering an

order which merely shifts some of Legal A id ’s

caseload to 18-B attorneys, not subject to the same

degree of judicial supervision, and which does not

relieve the congestion and delays which are at the

heart of the crisis in Kings County, or even direct

that adequate funds be provided for the employ

ment of additional attorneys and investigators by

PAGE

the Society ................................................................ 42

The Need for Federal Enforcement of a Prompt

Trial R u le ........................................................... 44

The Relief Granted Adversely Affects the Condi

tions in Kings County .................................... 48

Conclusion 50

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Argersinger v. Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25 (1972) .................. 43

Barker v. Wingo, 407 U.S. 514 (1972) .......................... 47

Brown v. Duggan, 329 F.Supp. 207 (W.D. Pa. 1971) .... 35

Burgett v. Texas, 389 U.S. 109 (1967) .......................... 37

Chambers v. Maroney, 399 U.S. 42 (1970) .................. 37

Christman v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, et al.,

275 F.Supp. 434 (W.D. Pa. 1967), cert, denied, 393

U.S. 885 (1968) ....................................................... 35

Conley v. Dauer, 463 F.2d 63 (3d Cir. 1972) .............. 42

Conover v. Montemuro,------F .2d ------- (3d Cir. Dec.

20, 1972, No. 71-1871) ............................................ 42

Espinoza v. Rogers, 470 F.2d 1174 (10th Cir. 1972) 33

French v. Corrigan, 432 F.2d 1211 (7th Cir. 1970),

cert, denied, 401 U.S. 915 (1971) .......................... 33

Gardner v. Luckey,------F. Supp. —— (M.D. Fla., Jan.

24, 1973, No. 71-561 Civ. T-K) ................................ 33

Gilliard v. Carson, 348 F. Snpp. 757 (M.D. Fla. 1972) 43

Green v. City of Tampa, 335 F. Snpp. 293 (M.D. Fla.

1971) ..................................................................... 43

Hilbert v. Dooling, ------ F .2 d ------ (March 12, 1973,

en banc, slip opinion at 2192) ................................. 38

Jackson v. Hader, 271 F. Supp. 990 (W.D. Mo. 1967) 35

Lefcourt v. The Legal Aid Society, 445 F.2d 1150 (2d

Cir. 1971) ...........................................................27, passim

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965) .................. 37

Littleton v. Berbling, 468 F.2d 389 ( 7th Cir. 1972),

cert, granted, 41 U.S.L.W. 3527 (April 2, 1973) 42-43

Loper v. Beto, 405 U.S. 473 (1972) .............................. 37

PAGE

IV

Mulligan v. Schlachter, 389 F.2d 231 (6th Cir. 1968) 33

Palermo v. Rockefeller, et at., 332 F. Supp. 478

(S.D.N.Y. 1971) (Mansfield, J.) .............................. 34

Peake v. County of Philadelphia, 280 F. Supp. 853

(E.D. Pa. 1968) ......................................................... 35

People ex rel. Franklin v. Warden, Brooklyn House

of Detention, 31 N.Y. 2d 498 (1973) ...................... 16, 45

People v. Ganci, 27 N.Y.2d 418 (1971) .......................... 45

Powe v. Miles, 407 F.2d 73 (2d Cir. 1968) .................. 28, 29

Pugliano v. Staziak, 231 F. Supp. 347 (W.D. Pa. 1964),

aff’d per curiam, 345 F.2d 797 (3d Cir. 1965) ....... 34

Reinke v. Richardson, 279 F. Supp. 155 (E.D. Wise.

1968) ..................... 35

Szijarto v. Legeman, 466 F.2d 864 (9th Cir. 1972) .... 33

Thomas v. Howard, 455 F.2d 228 (3d Cir. 1972) .......... 33

Thorne v. Warden, Brooklyn House of Detention,------

F .2d------ (May 16,1973, slip opinion at 3609) .2,16,47

United States ex rel. Frizer v. McMann, 437 F.2d 1312

(2d Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 1010 (1971) .16, 46

United States ex rel. Marcelin v. Mancusi, 462 F.2d

36 (2d Cir. 1972) ................................................... 36

United States ez rel. Wood v. Blacker, 335 F. Supp.

43 (D. N.J. 1971) ................................................... 34

Vance v. Robinson, 292 F. Supp. 786 (W.D. N.C. 1968) 35

Wardrop v. Ross, 319 F. Supp. 1299 (W.D. Pa. 1970) 34

Wood v. Virginia, 320 F. Supp. 1227 (W.D. Va. 1971) 35

PAGE

V

Statutes and Rules:

PAGE

18 U.S.C. §3006A(a) ....................................................... 14

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................................. 3, 5, 7, 27, passim

New York Criminal Procedure Law (“ CPL” ) §10.30 8

CPL §180.10(2) ................................................................. 9

CPL §190.80 ...................................................................... 10

New York County Law, Article 18-B ........................4,13,18

New York County Law, §722 ......................................... 14

Miscellaneous:

American Bar Association’s Project on Standards for

Criminal Justice—The Defense Function (1970) 23,

31, 37, 38

American Bar Association’s Project on Standards for

Criminal Justice— Standards Relating to Speedy

Trial (1968) .............................................................. 38

Appellate Division, Subcommittee on Legal Represen

tation of the Indigent, Report on the Legal Rep

resentation of the Indigent in Criminal Cases

(Honorable Robert L. Carter, Chairman) (1971) 40

Judicial Conference Management Planning Unit

March Term Report ................................................. 8

Monthly Reports of the Special Committee for Pur

pose of Alleviating Overcrowded Conditions Pre

vailing in Local Houses of Detention and to Ex

pedite Disposition of Criminal Cases .................. 46

The New York Times, May 27, 1973, p. 16, col. 4 ....... 47

Proposed Resolution 5 of Standards/National Legal

Aid and Defender Association at the National

Conference, November 9-11, 1972 .......................... 39

Report of the President’s Commission on Law En

forcement and Administration of Justice (1967) 39

Mnxtvh Staton dour! of Appals

For the Second Circuit

Docket Nos. 73-1826, 1830, 1831

------------— > * m -------------

Donald W allace, et al,, on behalf of themselves and all

others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

against

M ichael K ern, et al., etc.,

Defendants.

T he U nited States of A merica, ex rel.,

M ichael A. M cLaughlin , et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

against

T he City of N ew Y ork, et al.,

and

Defendants,

T he Legal A id Society of the City of New Y ork,

Defendant-Appellant.

M ichael A. M cLaughlin , et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

against

People of the State of New Y ork, et al.,

Defendants,

and

T he Legal A id Society, Criminal Defense D ivision,

of the City and State of New York,

Defendant-Appellant.

Appeal from Orders of the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of New York

BRIEF OF APPELLANT LEGAL AID SOCIETY

2

Preliminary Statement

This in an appeal by the Legal Aid Society (“ Society” )

from a preliminary injunction of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of New York (Judd, D.J.)

which, among other things, restrains the Society from ac

cepting or acting upon additional assignments of felony

cases in Kings County Supreme Court so long as the aver

age caseload of its attorneys in the trial parts of such Court

exceeds 40.*

The opinion below, like this Court’s recent decision in

Thorne v. Warden,** reflects deep and justifiable concern

over the intolerable calendar conditions in the criminal

courts in Kings County. We share this concern, as this

Court knows from the Society’s brief in Thorne. No party

has been more outspoken than the Society in pleading for

additional resources for the criminal justice system so as

to assure all defendants a prompt and fair trial. In Kings

County, the District Court found, “ it is not unusual for

defendants who cannot post bail to be held in custody for

12 to 15 months before their cases can be tried. ” f

A “ dramatic increase” in indictments in Kings County

has thrown the Court into a state of deep crisis in which

there are simply not enough judges and facilities to afford

persons charged with a crime a prompt trial. With new

legislation providing for mandatory sentences for certain

offenders, and the failure of the state to designate a single

one of the 100 new judges to Kings County, the crisis in

* The Court also directed the Supreme Court clerks to place pro

se motions on the calendar. That portion of the order is not the

subject of this appeal.

** Thorne v. Warden, Brooklyn House of Detention, ------ F.2d

------ (May 16, 1973, slip opinion at 3612-3613).

f Memorandum opinion of May 10, 1973, Docket # 6 3 in Wallace,

p. 5 (hereinafter cited as “ Opinion” ).

3

failure to provide prompt trials can only become worse.

The District Court concluded that:

“ While the court remains mindful of the limitations

on federal court intrusion in a state’s criminal justice

system, it bears reiteration that the crisis situation in

Supreme Court, Kings County, its long existence, and

the failure of the state and city thus far to provide

effective remedies justifies federal court action.”

(Opinion, p. 44)

Having stated the case for federal intervention, the

District Court, in recognition of ‘ ‘ a federal court’s limited

powers and in the interest of comity with state courts,”

declined at this stage to enter an order directing that

prompt trials be held and mandating the additional re

sources necessary to achieve this constitutional end. In

stead, departing from an unbroken long line of decisions,

in this Circuit and elsewhere, holding that the Society and

other organized defender services were not engaged in

“ state action” within the meaning of 42 U.S.C. §1983, the

District Court chose, as “ the most practicable way” to

reconcile intervention with federalism, to run its injunction

against a private defender organization, which has no

power to summon the resources necessary to relieve the

crisis in the state courts.

The Court’s objective to promote the most effective

assistance of counsel is the Society’s objective. But the

injunction against the Society will not relieve calendar con

gestion, accelerate the trial of cases, reduce the control of

the calendar by the District Attorney, permit the Society

to hire additional attorneys, or add one whit to the resources

necessary for the fair and prompt disposition of criminal

cases. It will, if not reversed, require the Society to divert

its scarce resources to defending a flood of Section 1983

lawsuits, saddle the Society with mechanical and arbitrary

caseload limitations stated as constitutional imperatives,

4

subject the Society to a finding of unconstitutional repre

sentation of clients, which may have implications in other

courts, and most of all, relegate indigents to representa

tion by inexperienced counsel who have been impressed on

an emergency basis at a grossly inadequate compensation

scale under Article 18-B of the County Law.

As the District Court recognized, increased reliance

on private counsel appointed pursuant to 18-B may actually

add to calendar delays “ because such counsel will not be

permanently assigned to a Part, like a Legal Aid attorney.”

Indeed, the plaintiffs themselves urged that the diversion of

excess cases from the Society to 18-B attorneys was “ not

merely inappropriate but impermissible,” * and urged that

the state and city be directed to make available the resources

for the employment by the Society of additional attorneys

and investigators.

We appeal from the District Court’s order because it

is directed against the wrong party and provides no relief

for the thousands of indigents who are the victims of the

overcrowded calendars in Kings County.

The Issues Presented

1. Did the District Court err in holding that the Soci

ety was “ acting under the color of state law” in accepting

and acting upon assignments by the State Supreme Court

to defend indigents accused of crime?

2. Did the District Court err in finding new constitu

tional imperatives in the American Bar Association’s Proj

ect on Standards for Criminal Justice, and in translating

those standards into numerical caseload limitations?

* Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion for Pre

liminary Injunction, Docket # 4 3 in Wallace, p. 14.

5

3. On the findings below, did the District Court err in

entering a preliminary injunction which will have the effect

merely of shifting some of the caseload from the Society

to an undermanned 18-B panel, and which does not provide

either (a) relief against the failure of the state to afford

defendants in Kings County prompt trial, or (b), as plain

tiffs requested, direct that adequate funds he provided for

the employment of additional attorneys and investigators

by the Society?1

Statement of Facts

The Proceedings Below

The injunction against the Society was issued after hear

ings had been held in three separate but related cases:

Wallace v. Kern, United States ex rel. McLaughlin v. Peo

ple of the State of New York, and McLaughlin v. People

of the State of New York.

The W allace Action

The Wallace case, brought under 42 U.S.C. §1983, was

commenced as a class action in July of 1972 by a group of

inmates in the Brooklyn House of Detention awaiting trial

on felony charges in Supreme Court, Kings County. Inso

far as is pertinent here, the complaint named as defendants

all the Judges of that Court, its Chief Clerk, the Clerk of

its Criminal Term and the District Attorney of Kings

County. It made numerous allegations about the quality

of the administration of criminal justice in that county,

including the failure to afford defendants a prompt trial.

Although the complaint did not name the Society as a de

fendant, it charged that the Society’s resources were so

overtaxed and the criminal justice system in Brooklyn so

structured that plaintiffs and other indigents were being

denied their constitutional right to effective representation.

The complaint sought, inter alia, an order directing the

6

dismissal of all charges pending against an accused for

more than six months or, in the alternative, directing the

release of any person who had been incarcerated for more

than six months awaiting trial on such charges; a declara

tion that certain of defendants’ practices deprived plain

tiffs of adequate representation by counsel; and an order

enjoining them from the continuation of such practices.

The case was ultimately assigned to Hon. Orrin G. Judd,

who, declaring it to be a class action, ordered an evidentiary

hearing limited to plaintiffs’ applications for a preliminary

injunction with respect to those of defendants’ practices

which allegedly prevented assigned counsel from adequate

ly representing plaintiffs.* The hearings commenced in

February 1973, and the Society, not being a party to the

action, did not participate at that stage.

The McLaughlin Actions

Before the hearings in Wallace commenced, the second

McLaughlm action was brought pro se under Section 1983

by other inmates of the Brooklyn House of Detention await

ing trial on felony charges in Supreme Court, Kings

County.** The named defendants included the Society,

the City of New York, the Presiding Justice of the Appel

late Division, Second Department, the Justices of the Su

preme Court in Kings County, the Chief Clerk of that

Court, and the Administrator of the attorneys ’ panel set up

under Article 18-B of the County Law. Insofar as is

pertinent here, the complaint alleged that counsel assigned

to represent indigent defendants in Kings County Supreme

Court were violating their constitutional rights by repre-

* The Supreme Court’s practice with respect to pro se motions

was also a subject of the hearing. That aspect of the case, however,

is not an issue in the Society’s appeal.

** A prior proceeding in the nature of habeas corpus had been

brought by the McLaughlin plaintiffs. 73 Civ. 55.

7

senting them inadequately.* Plaintiffs sought to enjoin

defendants, including the Society, from interfering with

their constitutional rights.

The Society moved to dismiss the McLaughlin actions

on the ground that, in representing indigent defendants in

state criminal cases, it was not acting ‘ 'under color o f”

state law within the meaning of Section 1983. The motion

was denied on April 6,1973.

Evidentiary hearings in Wallace had been held in Febru

ary. The Court scheduled hearings on the McLaughlin

complaints against the Society for April, which had the

effect of bringing the Society before the Court.** At the

April evidentiary hearings, the Society was given the op

portunity to respond not only to the allegations in Mc

Laughlin but to those in Wallace as well. The Court

treated the actions as consolidated insofar as the claim of

inadequate representation was concerned, and the orders

from which this appeal is being taken were issued in the

McLaughlin actions.

* Both Michael A. McLaughlin and his co-plaintiff Kenneth J.

Stone had brought separate actions under 42 U.S.C. §1983 against

the Society and others alleging, inter alia, the ineffective assistance

of court-assigned counsel. See E.D.N.Y. Docket Nos. 72-C-815

and 72-C-1037. By two orders filed October 13, 1972, both actions

were dismissed by Judge Travia on the grounds that they were really

habeas corpus actions disguised as civil rights suits and that plain

tiffs had not exhausted state remedies. Their applications for leave

to appeal in forma pauperis, for certificates of probable cause and for

assignment of counsel were denied by this Court. See Docket Nos.

72-8327 and 72-8243.

** The Court indicated the reason why it desired the Society be

fore it: “ I would rather be able to issue an injunction against both

the Legal Aid Society and the judges of the courts so that if there is

any dispute about it I would not be in a position of having to hold

any judge in contempt.” Wallace minutes of March 29, 1973, at p. 7.

Ultimately, only the Society was enjoined, not the judges.

8

The Structure of the Criminal Courts in Kings County

The criminal justice system in New York by its very

structure diffuses responsibility for the management of a

felony case between two courts, and many judges sitting

in different parts. To the accused, the system is a maze

with no end—except by plea bargain. The court has the

resources to try only a minimal number of cases. Out of

its cases pending in the past year, only 7.2% were disposed

of by trial as opposed to 81.4% which terminated in plea

bargains. As of this March Term, 1992 defendants were

awaiting trial and incarcerated because of their inability

to make bail. The backlog keeps growing as the intake

exceeds the output despite the incentive for plea bargains.

If all incarcerated defendants insisted on their right to

trial, it would take almost 4 years for the court at its pres

ent size and pace to try those cases, without any considera

tion for the new cases brought in the interim.*

The Criminal Court

The starting point for the felony defendant in Kings

County is generally the Criminal Court. The Criminal

Court of the City of New York is a city-wide court, with two

types of jurisdiction, trial jurisdiction over offenses of less

than felony grade, and preliminary jurisdiction over felony

cases. (New York Criminal Procedure Law [“ CPL” ]

§10.30.)

The Criminal Court sitting in Kings County has a num

ber of parts serving different judicial functions—arraign

ment parts, ‘ ‘ all purpose ’ ’ parts, hearing parts, trial parts,

etc. When a defendant charged with a felony is first

* Based on the figures and assumptions of the Judicial Confer

ence Management Planning Unit March Term Report. The

court is of course adding parts. However the impact of the new

state legislation imposing mandatory minimum prison term has not

been considered. Responsible estimates suggest that 124 new Su

preme Court parts will be required in the City of New York.

9

brought to the Court, he will appear in an arraignment

part, where he will be advised of the nature of the charge

against him and of some of his rights with respect to that

charge. The conditions of his release from detention pend

ing the ultimate disposition of his case will also be deter

mined by the judge. I f the defendant qualifies for assigned

counsel, the assignment will usually be made upon arraign

ment.*

A defendant charged with a felony in the Criminal Court

is entitled to a hearing on the issue of whether there is

sufficient evidence to warrant the Court’s holding him for

action by the grand jury. CPL §180.10(2). The accused

may waive the hearing, but if he does not and if he is in

carcerated, he must be released on his own recognizance

if that hearing has not commenced within 72 hours of his

incarceration.

There are three ways by which a felony case pending

in the Criminal Court may reach the grand jury and,

through an indictment, the Supreme Court. First, the ac

cused may waive a hearing, and be held for grand jury

action. Second, the Criminal Court may, after a hearing,

hold the defendant for such action. Third, the prosecutor

may, even in the absence of a hearing or the waiver thereof

by the accused, present the case to the grand jury and

obtain an indictment, thus divesting the Criminal Court of

further jurisdiction over the matter.

In practice, most cases proceed via a preliminary hear

ing to the grand jury. The Society’s attorneys seldom

* One of the complaints against the Society voiced by plaintiffs

in the court below involved the brevity of the prearraignment inter

views conducted by Society attorneys in the Criminal Court. See,

e.g., transcript of the Wallace hearings (hereinafter cited as Wal

lace), at 170. It was later brought out, however, that a prearraign

ment interview with counsel was a benefit given only to defendants

represented by the Society. Those with private counsel cannot con

fer with their attorneys until the actual arraignment. See transcript

of the McLaughlin hearings (hereinafter cited as McLaughlin) at

310, 490, 491.

10

waive a hearing since it provides the defendant with an

invaluable pre-trial—indeed, pre-indictment— examination

of the prosecution’s case and witnesses. (McLaughlin,

328-31).

If a defendant is held for grand jury action after either

a hearing or his waiver thereof, the prosecutor must present

his case to a grand jury with reasonable promptness. If

the defendant is incarcerated for 45 days without such

action he is entitled, upon motion in the Supreme Court,

to be released.*

The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court in Kings County has three types of

parts—arraignment, conference and trial. Upon indict

ment, a defendant appears in the arraignment part, where

he is advised of the nature of the charges against him, has

the conditions of pre-trial release fixed by the court and,

if eligible, is assigned counsel.** Some time after arraign

ment, a defendant’s case appears on the calendar of a con

ference part, where, through counsel, he is informed of

the “ plea” offer which emerges from the conference, and

* See CPL §190.80. See also the testimony of Mr. Gallagher

at McLaughlin, 372, 373, as to the system devised by the Society by

which motions under CPL §190.80 are automatically made with

respect to those of its clients who have been held. Barry Wilson,

one of the named plaintiffs in Wallace, complained that the Society

had made no such motion on his behalf and that, although his pro se

motion had been granted, the Society’s attorneys did not notify him

of that fact, thus causing him to spend needless days in jail. See

Wallace, 175-79. During the McLaughlin hearing, however, it was

brought out that: (a) the Society had advised Wilson that such

a motion was not being made since a warrant on another charge

which had been lodged against him would render the motion fruit

less; and (b ) a Society attorney, unaware of the warrant, had argued

Wilson’s pro se motion. See McLaughlin, 581-91. Wilson spent no

extra time in jail by virtue of any act or failure to act by a Society

attorney.

** An assignment of counsel in the Criminal Court is not effective

in Supreme Court.

11

the maximum sentence he might receive under such a plea.*

The conference parts, like the preliminary hearing in the

Criminal Court, also serve a discovery function. To ad

vance the plea bargaining process, the prosecutor must

often lay his cards on the table, giving the defense the op

portunity to evaluate the prospects of success at trial.**

If a defendant declines to accept the offered plea, his case

is marked off the calendar and assigned to a trial part.

The case remains in a trial part until its ultimate dis

position.

There are now 24 trial parts in Kings County, including

2 homicide parts and 2 additional parts which were estab

lished last year at the request of the District Attorney to

handle so-called “ major offenses.” Sixteen of the trial

parts are now manned by the Society’s attorneys and handle

almost exclusively the cases in which the Society represents

the defendant.

In theory, the calendars of the Court are subject to con

trol by the Court (McLaughlin, 704-05). In practice they

are controlled by the assistant district attorney ( Wallace,

34) who selects for each part 30 cases to be included

each week on the ready day calendar, and chooses on short

notice the cases within the 30 to be tried (Wallace, 83-87).

There was testimony that the assistant district attorneys

tend to select their strongest cases for trial, with the ironic

effect that defendants with the best prospects of acquittal

* The sentence “ promise” is a conditional one, and its fulfillment

depends upon whether the judge, after reviewing the pre-sentence

report, believes the interests of justice would be served by such a

sentence. If not, the defendant is permitted to withdraw his plea

and stand trial. See McLaughlin, 211. One of the charges against

the Society, made by Peter Grafakos, was that a Society attorney

failed to assist him in enforcing an absolute and unconditional sen

tence. See McLaughlin, 211. The minutes of Grafakos’s guilty plea,

however, clearly show that the promise made to him was a condi

tional one, which the judge, upon consideration of the probation

report, withdrew. See Society’s Exhibit W W .

** McLaughlin, 343.

12

must languish in jail awaiting their day in court (Wallace,

230; McLaughlin, 355). Cases on the ready day calendar

will sometimes he dropped by the assistant district attorney

one week, only to reappear in a later week (McLaughlin,

742). Predictability of a trial date is impossible.

With the court choked by a mushrooming volume of

cases, the very term “ trial part” has become a cruel mis

nomer. Only 110 cases could be tried in the Society’s trial

parts in 1972.*

The Legal Aid Society

The Structure

The Society is a private membership corporation

formed in 1876 for the purpose of providing representation

to the poor. The Society is managed by a Board of Direc

tors consisting of private citizens elected by the member

ship.

Of the Society’s approximately 500 attorneys, 370 are

assigned to the Criminal Defense Division. In addition,

the Criminal Defense Division has a staff of over 68 ex

perienced investigators.

Each new attorney in the Criminal Defense Division is

given five weeks of intensive training, including lectures,

simulations and appearances in court, supervised by the

trainers. (Docket # 6, 73 Civ. 55.) The attorneys are then

assigned to an office in one of the five counties. The most

experienced attorneys are ultimately assigned to the Su

preme Court for felony cases; the junior attorneys are as

signed to the Criminal Court, where, under the supervision

of senior attorneys, they handle, among other things, ar

raignments, preliminary hearings, and trials of misdemean

ors.

* During 1972 the parts available to the Society for the trial of

cases were increased slowly to eleven parts.

13

As they gain experience in the Criminal Court, the-Soci

ety’s attorneys progress to the Supreme Court. Each of

the Criminal Defense Divisions’ offices in the five counties

is headed by an attorney in charge, who reports to the At

torney in Charge of the Society’s Criminal Defense Divi

sion, Robert Kasanof. Mr. Kasanof, who is also acting at

torney in charge of all divisions of the Society, has the

responsibility for maintaining an equitable distribution of

the Society’s manpower to meet the demands for profes

sional services in all counties.

Assignment of Criminal Cases to the Society

Article 18-B of the County Law of New York, adopted in

1965, required New York City to place in operation a plan

for providing counsel for all indigents charged with crime

within the City.

Pursuant to that provision, the Society was designated

in 1965 by the City to furnish counsel to persons within the

City of New York who were charged with a crime, but un

able to afford private counsel. The City entered into an

agreement with the Society in 1966, providing it with a

fixed sum for the representation of indigents charged with

crimes. (The contract was handed up to Judge Judd, was

referred to in his opinion and copies will be furnished to

this Court.) Each year, the Society and the City negotiate

the sum to be provided the Society for its next year’s opera

tions; except for the dollar amount, the original contract

remains in effect and has never been reexecuted. Upon 90

days’ notice, the Society may terminate the contract. The

Society has undertaken to employ sufficient attorneys, clerks

and investigators to provide representation to all indigent

defendants except where for good cause, such as the charge

of murder or a conflict of interest, the Society does not act.

In those cases, a lawyer is assigned from an “ 18-B panel’ ’

drawn by the panel administrator. The 18-B attorney is

14

paid by the City in accordance with certain rates and proce

dures established by statute.*

In negotiating the annual payment with the City, the

Society estimates its anticipated caseload. I f the actual

caseload threatens to exceed its capability, the Society is

protected by its right on 90 days’ notice to terminate the

agreement and decline the assignment of new cases. Con

trary to the lower court’s impression, the Society cannot be

compelled to continue to accept cases which in its profes

sional judgment it cannot handle. In 1972, only a last min

ute appropriation from the City deterred the Society from

terminating the arrangement. (See Docket # 6 in 73 Civ.

55, p. 3.)

In the past two years the Society has incurred substan

tial deficits. For the fiscal year ending June 30, 1972 the

Society incurred a deficit of $754,650.00. For the six-month

period ending June 30,1971 the Society incurred a deficit of

$366,225.00. For the fiscal year ending June 30, 1972 the

Society realized from the private sector $1,526,700.00. It

received $5,403,866 from the City of New York, and $1,668,-

135 from the Federal government in the form of grants to

support its criminal defense efforts.**

At no time has the City attempted to interfere in the

operations of the Society, or given any direction to the

Society on how it should operate or handle its cases.

Neither the City, State nor Federal government has any

* The rate of compensation is $10 per hour for out-of-court work

and $15 per hour for in-court work— a rate exactly one-half of that

provided under the Federal Criminal Justice Act. See County Law

§722; 18 U.S.C. §3006A(a). The attorneys on the panel need not

specialize in criminal law. They undergo no training program. They

function without supervision. They have other cases to handle in

addition to those obtained through the assignment process. (See

McLaughlin, 392, 394-395). No increase in the rate of compensa

tion was enacted by the Legislature at the session which just ended.

** The Society’s annual report, although not marked as an exhibit,

was submitted to the District Court, and copies will be filed with this

Court.

15

representation on the Society’s Board. The Society oper

ates autonomously, and without any governmental control.

Indeed, the agreement with the City explicitly acknowledges

that the Society “ shall alone be responsible for their [its

attorneys’, investigators’ and other employees’ ] work, and

the direction thereof, and their compensation.”

The Society’s Kings County Office

At present, the Society has 115 attorneys and 19 inves

tigators assigned to criminal cases in Kings County. Of

these attorneys, 46 are assigned to the Criminal Court, 57

to the Supreme Court, and 12 to the Community Defense

Office. Included in the figure are seven experienced super

visors.

When a defendant is brought to Criminal Court for

arraignment, he is interviewed in the “ pen” by a Legal

Aid attorney to determine if he qualifies for representa

tion. I f he does, the judge sitting in the arraignment part

will assign the Society to represent him or, in the case of

conflict or murder charges, an 18-B attorney. The assign

ment is effective only for the Criminal Court and tech

nically expires when the defendant is held for grand jury

action. Once a defendant is indicted, a new assignment of

counsel is made at the arraignment part in Supreme Court.

Thus, as a general rule, the Legal Aid Society is appointed

twice to represent each indicted indigent defendant, first

in the Criminal Court and later in the Supreme Court.

As will be described at p. 17, infra, the Society, never

theless, continues to represent its clients during the period

when the case is awaiting grand jury action. Indeed, the

Society had developed a system for assigning, prior to

grand jury action, a Supreme Court attorney to the defend

ant who would be expected “ to carry” the case through trial

if an indictment resulted (McLaughlin, 324-325, 827-829).

16

Almost 75 percent of all defendants accused of felonies

and 90 percent of those incarcerated pending trial in Kings

County are represented by the Society (Wallace, 22, 28-29).

The Crisis in Kings County Supreme Court

The administration of criminal justice in Kings County

Supreme Court is in a state of crisis. Incarcerated defend

ants awaiting trial in that court must often wait for more

than a year to have their cases heard.* This deplorable

situation is not of recent origin. Speedy trials were being

denied to incarcerated defendants in 1970, when this Court

decided United States ex rel. Frizer v. McMann, 437 F.2d

1132 (2d Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 1010 (1971).

Since then, the situation has grown far worse, as both this

Court and the New York Court of Appeals have recently

noted.** A partial explanation for the worsening of the

* The Court below found that as of the end of 1972, “ there were

644 defendants who had been * * * [incarcerated] for more than six

months * * * and nearly half that number had been there over a

year.” See Opinion, p. 6.

** See Thorne v. Warden, Brooklyn House of Detention, -------

F.2d ------- (2d Cir. May 16, 1973) ; People ex rel. Franklin v.

Warden, Brooklyn House of Detention, 31 N.Y.2d 498 (Feb. 16,

1973). The Society’s brief in the Thorne case, made a part of the

record in the Court below, provides, at page 26, the following figures

as to the number of defendants awaiting trial in Kings County Su

preme Court incarcerated more than 90 days:

October 1971 516

November 1971 667

December 1971 545

January 1972 875

February 1972 562

March 1972 512

May 1972 398

June 1972 638

August 1972 710

October 1972 746

November 1972 901

December 1972 935

January 1973 856

17

crisis may be found in the dramatic increase in indictments

obtained by the Kings County District Attorney in 1972, a

year in which indictments increased by 48 percent over

1971 while felony arrests decreased by 8 percent (Docket

#6 , 73 Civ 55 at p. 26). More so than ever before, there

fore, the Supreme Court found itself without the facilities

to cope with the ever-increasing number of indictments

which ultimately overwhelmed it.

The net result of this backlog of cases is the wholesale

denial of incarcerated defendants’ rights to a speedy trial

and the frustrations caused by such a denial. Moreover,

the control of the Court’s calendar by the District Attorney

climaxes the long trial delay with an unfairly short period

for final preparation and notification of witnesses.

The Society’s Efforts to Cope With the Crisis

Over the past 18 months, as the crisis in Kings County

grew, the Society has made constant efforts to cope with it.

It has more than tripled its staff in the Supreme Court

office, from 16 in December of 1971 to 48 in March of 1973

to 57 at present.* It initiated a system to increase continu

ity of representation of its clients by enabling its Supreme

Court attorneys to assume responsibility for a defendant

shortly after that defendant’s case leaves the Criminal

Court,** It has filed hundreds of motions requesting the

dismissal of an indictment for lack of a speedy trial.f

It has initiated numerous bail reviews for its incarcerated

clients, resulting, for example, in the pre-trial release of

more than 200 of them during the summer of 1972. $ It

* See McLaughlin, 313. The rate of staff increase has far ex

ceeded the rate of increase in the number of indictments.

** That system, called the “ digit system” , is explained at 324, 325.

It has now been replaced by a new system with the same purpose.

See McLaughlin, 827, 828, 829.

f See, e.g., McLaughlin, 33.

f See McLaughlin, 336.

18

has held numerous conferences with those having power to

administer in the court. (McLaughlin, 360 et seq.) It has

suggested that all trial parts maintain a full schedule this

summer and has offered to man all those parts in an effort

to reduce the backlog in Supreme Court.* These efforts,

however, have failed to relieve the calendar congestion.

The Supreme Court simply has not been provided with

resources adequate to the task of handling the staggering

number of cases on its calendar.

The Quality of the Society’s Services

The District Court found that, despite their increased

burden, ‘ ‘ Legal Aid attorneys compare favorably with pri

vate attorneys in the quality of their work and their

results.” (Opinion, p. 18.) The record firmly supports this

finding. No judge before whom those attorneys appear, on

a daily basis, has ever complained to the Society about the

caliber of their services to our clients; the only complaint

voiced by the state judiciary was about the zeal of the

Society’s attorneys in bringing every conceivable motion

to protect those clients.** As the District Court found,

the Society’s acquittal rate in Kings County Supreme

Court is about the same as that of the private bar.f In

deed, there is not a single instance supported by the record

below in which a client of the Society was prejudiced or

harmed in any way by the action of any of its attorneys.

The Court below, in its opinion, equated the quality of

the Society’s attorneys with that of those assigned under

Article 18-B of the County Law.f Virtually every witness,

however, when asked to make a comparison between the

* See McLaughlin, 317-320, 361-362.

** See McLaughlin, 311, 341.

f See Opinion, p. 48.

f See Opinion, p. 48.

19

Society and the 18-B attorneys, testified that, on the whole,

the Society’s attorneys were better.*

The 18-B panel operates with major disabilities. As

Justice Thomas R. Jones testified, “ the criminal bar of

Brooklyn is limited.” (McLaughlin, 707). The fee sched

ule for 18-B attorneys admittedly is inadequate, and attor

neys have resigned from the 18-B panel in protest against

the meager fee awards. (Wallace, 125, 128, McLaughlin,

402). There are no funds available to institute programs

for recruitment or training of new attorneys for the 18-B

panel. (McLaughlin, 386-417.)

The administrator of the 18-B panel in Kings County

testified that while the panel “ could perhaps handle more

cases, I am not prepared to say how many more cases that

would be. I find it very difficult in my office to get attor

neys, frankly, to participate in the 18-B panel at this par

ticular stage.” (McLaughlin, 390-91.)

In recognition of these limitations of the 18-B program,

counsel for plaintiffs in Wallace specifically requested the

Court below not to rule that 18-B attorneys should be as

signed the cases which the Society would he unable to

handle because of any caseload limitation imposed upon

it.** Instead they urged that the Society be authorized to

have additional personnel—a recognition that, properly

funded, the Society is the organization best suited to render

effective representation to indigents.

Caseload

There was no evidence, or finding, that the outcome of

a single case had been prejudiced by the caseload carried

* See, e.g., McLaughlin, 311, 312, 669, 721; Wallace, 125, 232,

297, 381.

** See plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion for

Preliminary Relief, Docket # 4 3 in Wallace.

20

by the Society’s attorneys. There was, however, testimony

from a number of the Society’s attorneys that the maxi

mum caseload per trial attorney should be no more than

50 and, preferably, 40. (Wallace, 44, 86). The plaintiffs,

and the Association of Legal Aid Attorneys, urged a case

load limitation of 40 per Supreme Court attorney, including

cases awaiting sentence and grand jury action. (Docket

#60 in Wallace, 72 Civ. 898).

The Society’s position on numerical limitations was

expressed in the testimony of its Director of Operations,

and the affidavit of its Acting Attorney in Charge. Stress

ing the calendar stagnation in Kings County, the Director

of Operations testified that an attorney can handle any

number of cases “ if he is not going to trial for a year, a

year and a half” (McLaughlin, 477). The Acting Attorney

in Charge stated:

“ It is my own view that this problem will not be

finally resolved until the courts or the legislatures im

pose an absolute requirement that every defendant

accused of a crime and confined must be brought to

trial or released from custody within ninety days, ex

cepting only such period of delay as are the result

of conscious, freely-elected action by the defendant.

Such a requirement of speedy trial with effective sanc

tions will, I believe, produce an expenditure of the

public resources required to implement it, and I am

pessimistic that any other measures will be as fully

effective.” Afif. of Robert Kasanof, April 28, 1973,

Docket # 5 , 73 Civ. 55.

In imposing a caseload limitation on the Society, the

District Court relied in part on the testimony of a private

attorney called as an expert by plaintiffs, who stated that

his criminal caseload ranged between 25 and 35 active cases.

But the same attorney testified that his cases included a

homicide which entailed a 7-week trial, and that in addition

21

lie handled some civil matters. Moreover, unlike the So

ciety, he did not have the benefit of permanent investigators,

nor the convenience of offices within the court {Wallace,

100-139). One cannot dispute the fact that even 25 active

cases awaiting trial in different courts, including complex

cases requiring protracted trials, may be too many cases

for any single attorney to handle. But that begs the ques

tion of how many cases a skilled attorney can master and

effectively defend in a court in which the opportunity for

a trial is a rare event.

The fact is that numbers are no substitute for the pro

fessional judgment of attorneys as to whether they can

effectively assume responsibility for more cases. Indeed,

one need look no further than the Federal court to ap

preciate the unreliability of a case count as a measure of

effective representation. There, with calendars controlled

by the courts, cases handled by the Society, which are gen

erally more complex than those brought in the state court,

proceed promptly to trial despite the fact that the average

caseload per attorney exceeds the 40 case maximum im

posed by the District Judge on the state court.

Despite the burdens it shoulders, and the uncertainty

created by the prosecution’s control of the calendar, it is

undisputed that the Society is not in any way responsible

for the delay in disposition of cases in Kings County. The

Society’s attorneys are prepared to try far more cases than

the Court has resources to try.

The Opinion and Orders Below

On May 10, the District Court simultaneously entered

an order including a preliminary injunction and filed its

principal 57-page opinion. As we treat elsewhere (pp. 27-

36, infra) the Court’s earlier Memorandum and Order

dated April 6, denying our motion to dismiss on jurisdic

tional grounds, we focus here on the Court’s lengthy and

22

detailed opinion addressed to the conditions in Kings

County, and the relief it ordered.

The opinion below opens and closes on the same theme:

‘ ‘ The Criminal Parts of the Kings County Supreme

Court are in a state of deep crisis. The Deputy Di

rector of Operations of the Legal Aid Society testified

that ‘ The system isn’t working. ’ It has not been shown

that any individual judge or any Legal Aid attorney

or Assistant District Attorney is failing to do his best

under existing circumstances, but it is small comfort

to a defendant in jail to be told that the fault lies with

‘ the system’.” (Opinion, p. 5)

* # #

‘ ‘ The fact that the injunction to be granted will run

only against The Legal Aid Society and the Court

Clerks does not indicate any allocation of culpability,

but merely a determination of the most practicable

way, consistent with a federal court’s limited powers

and in the interest of comity with the state courts, to

remedy two of the deficiencies which led a Legal Aid

executive to testify, as quoted earlier, that ‘ The system

isn’t working’ ” (Opinion, p. 57).

The District Court found that, judged by traditional

standards of effective representation, the work of the Soci

ety and its lawyers was not wanting. Indeed, it found:

“ Legal Aid attorneys compare favorably with pri

vate attorneys both in quality of their work and in

their results. Their acquittal rate is approximately

the same as that of private attorneys. In the calendar

year 1972, Legal Aid obtained acquittals in 39.1 per

cent of the cases that were decided by jury verdict,

but there were only 140 trials out of 4,587 cases that

were closed.” (Opinion, p. 18)

* * *

23

‘ ‘ The overburdening of its attorneys is not the fault

of The Legal Aid Society, and it may not prevent

adequate representation being given in cases that are

actually tried. It is important, however, that criminal

defendants have the appearance of justice as well as

having a coincidental right result in the end.” (Opin

ion, p. 41).

The Court reasoned that since the litigation was one

in which it was being asked to exercise wide-sweeping

prospective control of the conduct of state criminal cases,

it could and should apply a different standard.

The Court reviewed the various functions which de

fense counsel should undertake in the discharge of their

duties, citing the American Bar Association’s Project on

Standards for Criminal Justice (pp. 37-40). The Court

concluded:

“ Comparing the level of representation now pro

vided by The Legal Aid Society with the American

Bar Association Standards, it becomes evident that

the overburdened, fragmented system used by Legal

Aid does not measure up to the constitutionally

required level.” (Opinion, p. 41).

The Court concluded that the appropriate relief was

a caseload limitation on the Society. The Court fixed an

average caseload of 40 for each of the attorneys assigned

to the trial parts of the Supreme Court and added a

requirement that new assignments could not be under

taken without the professional certificate of the local Brook

lyn office chief. The Court was at pains to emphasize the

importance of inclusion of sentencing cases in the calcula

tion (pp. 46, 47).

On May 17, 1973, one week after the Court entered its

injunction, Justice Damiani, the Assistant Administrative

24

Judge, District Attorney Gold and one of the latter’s as

sistants met ex parte with Judge Judd in his Chambers. As

a result, on the following day a conference of all counsel

was held in which the Court stated:

“ Now, I confess that my injunction order may be a

little cloudy.” (McLaughlin, 790)

# # #

“ I did not give thought to the practical problems

which may he involved between Criminal Court ar

raignments and Supreme Court arraignments or Su

preme Court preliminary hearings. I f I had done so,

I think I would have adopted the view that Justice

Damiani and the District Attorney urged that the

Legal Aid continue in those cases until there is an

arraignment in the Supreme Court.” (McLaughlin,

792)

The practical problems to which the Court alluded arose

in part from the treatment to be given cases which had al

ready left the jurisdiction of the Criminal Court and were

in the grand jury process. These defendants would be ar

raigned in the Supreme Court after indictment at a time

when the Society would be restrained by the Court’s Order

from undertaking further cases. The Court substantially

accepted the suggestions by the Assistant Administrative

Judge and the District Attorney that the Society be di

rected to continue its representation of defendants await

ing grand jury action until replaced by 18-B counsel. In

addition, the Court now excludes cases awaiting sentence

from the 40 case maximum—after having only a week be

fore declared in its opinion that “ Excluding cases awaiting

sentence from the caseload is inconsistent with the con

stitutional requirement for advice of counsel at the time

of sentence.” (Opinion, p. 46.) A new order modifying

the May 10 order in these respects was entered on May 22.

The District Court ’s injunction could not have intruded

more deeply on the Society’s internal affairs. It, in effect,

25

shifts responsibility from the Society’s executives to the

Federal court for determining the staffing needs of the

Society in the state court. Even after the caseload drops

below 40, the Society is barred from undertaking new as

signments unless its local administrator certifies to the

Federal court as well as to the clerk of the state court that

“ in his personal professional judgment (after consulta

tion with his supervisory staff in Kings County)” the as

signment of the additional cases to be anticipated in the

next month will not exceed the capacity of the Society to

give effective representation. The Society’s attorney in

chief is bypassed. The fact that the first application for

modification of the Court’s order came not from the Soci

ety, nor from plaintiffs, but from the prosecutor and As

sistant Administrative Judge does not bode well. The

District Court’s decision, we submit, consigns the Society

to a tug of war between its clients and the prosecutor over

the number of cases the Society should handle.

But the District Court’s order is as striking for what

it omits as for what it directs. Unwilling to act at this stage

against public officials who control the funding for assigned

counsel, the District Court took no steps to insure that

18-B counsel would be available, despite the undisputed

testimony in the record that new lawyers could not easily be

recruited because of the grossly inadequate compensation

rates. Rejecting the prayer by the Wallace plaintiffs that

the state be directed to provide the Society with additional

funds to increase the number of attorneys, the Court ob

served that ‘ ‘ difficulties in recruiting 18-B attorneys do not

justify forcing Legal Aid to accept more clients than it can

effectively represent” and it limited itself to expressing the

hope that the state courts “ may recognize the economic

facts of law practice” by increasing allowances to 18-B

attorneys. (Opinion, p. 49.)

The Court’s order leaves indigents with no assurance

that they will receive meaningful representation by coun-

26

sel. Indeed, the Court did not even consider imposing the

same caseload limitations on the private 18-B counsel, who

must he recruited on an emergency basis, that it imposed

on the Society.

The opinion below is even more disturbing in recogniz

ing, without acting upon, the heart of the crisis: the delay

which pervades the administration of justice in Kings

County. In view of the Court’s perception of the degree

of this crisis, it is puzzling that it singled out for its initial

consideration and fashioned relief which its opinion recog

nizes may exacerbate its delays,* and which will require

modification if “ defendants did not stay in jail as long, if

there were better facilities for interviews, if there were

more adequate supporting services, and if problems of

calendar control are resolved” (Opinion, p. 45).

A mandatory requirement that confined defendants re

ceive a speedy trial might, at least, have shaken loose the

public resources which are essential for any improvement

of the criminal justice system in Kings County. By acting

to fashion new relief on a new theory without mandatory

allocation of additional resources, the District Court left

untouched, and perhaps even aggravated, the chronic and

persistent violation of the constitutional right, of benefit

both to defendants and the public, of a speedy trial.

* “ Appointment of more 18-B counsel will cause some inconven

ience to the Judges and Court Clerks because such counsel will not be

permanently assigned to a Part, like a Legal Aid attorney, and some

calendar delays may result, but this factor is not sufficient to over

come the need for immediate relief.” (Opinion, p. 33) (emphasis

supplied).

27

P O I N T I

The Legal Aid Society— “ a private institution in no

manner under State or City supervision or control,” *

which performs a function “ normally performed for

and by private persons” **— does not act “ under color

of State law” within the meaning of Section 1983.

The District Court ruled that The Legal Aid Society is

“ so far involved with state action that it should not be

immune from suit” under Section 1983f (Opinion, April 6,

1973, Docket #10 in 73 Civ. 113, p. 7). The Society, the

Court held, had “ interposed itself as an agent of a munici

pality between the defendants and their right to counsel,”

and, “ [s]ince it is under contract with a subdivision of the

state to supply attorneys,” it is “ acting under color of

state law.” {Ibid.)

In so holding, the District Court rejected the unanimous

authority of the Federal courts—at least six decisions of

Courts of Appeals and twelve District Court decisions, all

of which have, without exception, held directly to the con

trary—including a 1971 decision of this Court holding

squarely that the Society is not an “ agent” of the City

or State and is not amenable to suit under Section 1983.

The question presented is of overriding importance to

the Society and to all private and public defender organ

izations.

In Lefcourt v. The Legal Aid Society, 445 F.2d 1150

(2d Cir. 1971), this Court ruled that a “ prerequisite” for

any relief against a defendant under Section 1983 was a

* Lef court v. The Legal Aid Society, 445 F.2d 1150, 1157 (2d

Cir. 1971).

** Id. at 1156.

f 42 U.S.C. §1983.

28

finding that a federal right had been denied by the defend

ant “ under color of state law.” The absence of such pre

requisite, this Court held, constituted a defect “ jurisdic

tional in nature.” (Id. at 1153-54). After meticulous re

view of the Society’s status, this Court concluded that the

Society was a private institution free of governmental

control, regulation and interference, and affirmed the dis

missal of a complaint brought against it under Section 1983

(Id. at 1155, 1157).

This Court, in its opinion in Lefcourt, stressed the So

ciety’s “ independence” from State or City supervision or

control (Id. at 1157). The management of the Society,

this Court noted, is vested in its Board of Directors, and

in officers elected by that Board (Id. at 1152). The Society’s

Attorney-in-Chief, the Court further noted, is designated

by its Board, as are the attorneys in charge of the Society’s

three divisions, including the Criminal Defense (then the

Criminal Courts) Division (Ibid.). In addition to govern

mental funding, the Society also receives “ private financial

contributions.” (Id. at 1154). The Society’s “ history,

constitution, by-laws, organization and management defi

nitely established,” this Court concluded, that the Society

is “ a private institution in no manner under State or City

supervision or control.” (Id. at 1157).

The District Court rejected the conclusion of this Court,

and it did so on a single basis. “ The Second Circuit,” the

lower Court stated, citing Powe v. Miles, 407 F.2d 73 (2d

Cir. 1968), “ has recognized the importance that a contract

may have in deciding whether a ‘ private’ institution has

acted under color of state law.” (Opinion, April 6, 1973,

p. 6). The Society, the lower Court held, had, by its con

tract with the City, “ interpos[ed] itself as an agent of a

municipality between the defendants and their right to

counsel” (Id., p. 7), and, “ [s]ince it is under contract with

a subdivision of the state to supply attorneys, ” it is “ acting

under the color of state law.” (Ibid.)

This Court’s decision in Lefcourt was distinguished on

the basis that that case “ was not related to any provision

of the contract between The Legal Aid Society and the

City.” (Ibid.)* In Lef court as in the instant cases, how

ever, the Society’s contract with the City** was directly

placed in issue and was, indeed, a chief basis on which it

was contended that the Society was acting “ under color

of state law” and hence subject to Section 1983.

This Court noted in Lef court that, in view of the allega

tions in the Lef court complaint which suggested that the

Society was “ the mere agency of the City,” f it was “ neces

sary to examine whether, irrespective of the function the

Society performs, it may be an agency of the City by virtue

of its contractual relationship with the City.” (445 F.2d

at 1155). This Court then concluded that the plaintiff in

Lef court had failed to establish

“ that the City or any other governmental subdivision

or agency had any right whatever to intervene in any

significant way with the affairs of the Society with

respect to its employment practices or otherwise.” (Id.

at 1155),

and further concluded that:

“ It cannot be said that the Society acts under color

of State law by virtue of the financial and other benefits

which it receives from the City and various other gov

ernmental agencies, courts and subdivisions, since there

* Nowhere does the lower Court’s opinion refer to the fact that

Powe v. Miles was discussed at length by this Court in Lefcourt and

was relied on as support for the conclusion that the Society was not

acting under color of state law and not subject to Section 1983.

** The 1966 contract with which the Lefcourt decision dealt is still

the agreement in effect today.

f Even such a finding might not be enough. This Court ex

plicitly noted in Lefcourt that, even if the Society were a “ mere

agency” of the City, “ the Society itself might not be a proper defend

ant since §1983 may not properly be used in suits against municipali

ties.” (Id. at 1155, n.5.)

29

30

has been no sufficient showing of governmental control,

regulation or interference with the manner in which

the Society conducts its affairs.’ ’ {Hid.)

It need not be added that there was no vestige of show

ing on the record below of governmental “ control, regula

tion or interference.” * Indeed, the record below rein

forces the conclusion of this Court in Lefcourt as to the

absence of “ control, regulation or interference.” The

City’s contract with the Society (submitted to the Court

below) explicitly provides that the Society “ shall alone be

responsible for their [the Society’s attorneys’ and em

ployees’ ] work, and the direction thereof. * * *” (Agree

ment, Paragraph First, p. 3). The only testimony before

the Court on the question of state control was the response

of a Society staff executive, when asked whether any City

official had ever attempted to tell any Society attorney how

to handle an individual case or what policy should be fol

lowed with respect to the defense of the indigent accused:

“ not once in the 27 years that I have been with the Society,

directly or indirectly.” (McLaughlin, 523-24.)

Legal Defender Organizations, Which Owe Undivided

Loyalty to Their Clients and Are, by Their Very Nature,

Adversary to the State, Do Not Act “ Under Color of

State Law” in Representing Indigents— and Federal

Courts Have Repeatedly So Held.

The anomaly of the lower Court’s decision is that it

branded, as acting “ under color of state law,” a legal de-

The District Court took judicial notice in its opinion of a re-

port of a committee (the “ Carter Commission” ) appointed by the

state Appellate Division as showing “ [t]he relation between The

-Legal Aid Society and the state in relation to staffing * * * ” This

report, the lower Court noted, “ is part of the record in Wallace v.

and also within the scope of judicial notice.” (Opinion, April

O, LWS p. 6 ). The report, however, in no way showed— nor could

have shown— any ‘ control, regulation or interference” by the state

n the Society s staffing— or in any other phase of the Society’s

operations.

31

fender organization which is generally regarded as a model

of independence and freedom from partisan political pres

sure.* The Society fully meets the goals of the American

Bar Association Standards for Providing Defense Services

that, to guarantee “ sufficient independence,” responsibility

for operation of a legal defender service must be lodged

in a board “ outside the ordinary framework of state or local

government” (p. 21). Equally, the system must be “ prop

erly insulated from pressures, whether they flow from an

excess of benevolence or from less noble motivations” (p.

20). Indeed, the Standards point out that:

“ The plan and the lawyers serving under it should be

free from political influence and should be subject to

judicial supervision only in the same manner and to

the same extent as are lawyers in private practice.”

(p. 19)

Not all defender organizations have been as fortunate

as the Society in being structurally independent of political

influence. As the ABA Standards state, in stressing such

independence as a chief advantage of private defender sys

tems :

‘ ‘ In privately financed defender systems the power

to select the chief defender is vested in the governing

board of the legal aid society or defender association.

The independence from political influence which this

form of selection permits has been cited as one of the

most advantageous features of private defender sys

tems. Some public defenders are elected officials;

* Indeed, the Society has now, or has had within the last year,

lawsuits pending against the Governor, the Mayor, the Presiding

Justice of the Appellate Division, Second Department, all the Judges

of the Criminal Court of the City of New York, all the Justices of

the Supreme Court of the State of New York authorized to sit

in the First Department, the Police Commissioner, the Commissioner

of Corrections of the City of New York, the Commissioner of Cor

rections of the State of New York, and numerous other public offi

cials.

32

others are appointed by the judiciary, * * * or by a

political body such as the county commission or city

council.” (p. 35)

Nonetheless, even in the case of public defender sys

tems which lack such complete independence, the Federal

courts have uniformly held that they are not under Section

1983 because they are not acting ‘ ‘ under color of state law.”

The rationale underlying this rule was cogently set out

by this Court itself in Lefcourt:

a* * * representation of persons accused of crimes,

far from being the function of any agency which ‘ tradi

tionally serves the community’ is normally performed

for and by private persons. Those who can afford

their own counsel value the fact that their relationship

with their attorney will be protected by the Courts

through the attorney-client privilege. The person with

a retained attorney knows that that attorney will use

his best efforts consistent with ethics and law, and that

no State official is in a position to alter this in any

way. The City has sought to have the Society function

under similar circumstances. Under the contract, the

City retains few controls over the Society, and the

Society’s obligation under the contract is to its clients

and not to the City.” 445 F.2d at 1156 (emphasis sup

plied).*

Every other court that has considered the status under

Section 1983 of private and public defender organizations,

as well as assigned counsel, has reached precisely the same

* Lef court noted that the plaintiff’s case did “ not involve the

manner in which the Society carries on its public function.” (445

F.2d at 1156-57). The Society’s fulfillment of its public function, the

representation of its clients, is, however, precisely that aspect of its

function which is not action of the state, but action taken solely on

behalf of the client in opposition to the purposes of the state.

33

conclusion as did this Court. In Espinoza v. Rogers, 470

F.2d 1174 (10th Cir. 1972), an action brought against

Colorado public defenders, the Tenth Circuit found that a

public defender’s professional duties and responsibilities

toward his client are the same as those of all other attor

neys, and that public defenders in the office of the Colorado

State Public Defender do not act under color of state law

so as to be amenable to suit under Section 1983. In French

v. Corrigan, 432 F.2d 1211 (7th Cir. 1970), cert. denied, 401

U.S. 915 (1971) and Mulligan v. Schlachter, 389 F.2d 231

(6th Cir. 1968), attorneys appointed by the state court to

represent indigent defendants were held to have been ap

pointed solely to serve the interest of the client, and thus

not acting under color of state law.* Similarly, in Thomas

v. Howard, 455 F.2d 228 (3d Cir. 1972), counsel was as

signed from a pool of attorneys maintained by the Essex

County Legal Aid-Criminal Division. The Third Circuit

concluded that the attorney appointed by the Court could

not be sued under Section 1983, observing that, since the

attorney was “ performing his duties solely for [his client],

to whom he owed the absolute duty of loyalty, as if he were

a privately retained attorney * * * [he] was not acting

‘ under color of state law, custom or usage ’ within the mean

ing of the Civil Bights Act * * * and no triable issue of

fact upon which relief may be granted remained in the

case.” (455 F.2d at 229-30) (citations omitted).

The same conclusion—that defender organizations are

not subject to Section 1983 since they do not act under

color of state law—has been reached by the District Courts

in a variety of suits brought against attorneys under Sec

tion 1983, including a recent decision in an action strikingly

similar to the instant actions: Gardner v. Luckey, ------

F.Supp. ---- (M.D. Fla., Jan. 24, 1973, No. 71-561 Civ.

T-K). There, plaintiffs, in an action under Section 1983

* See also Ssijarto v. Legenian, 466 F.2d 864 ( 9th Cir. 1972)

(attorney, whether retained or appointed, does not act under color of

state law).

34

against the Public Defenders for two judicial circuits for

failure to provide adequate representation, sought, among

other things, a caseload limitation. Although the office of

public defender was created by statute, and funded by the