Baskin v. Brown Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Baskin v. Brown Appellants' Brief, 1949. a4bac9e7-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dc1dec2c-8a6e-45db-ab04-c1026b3bb504/baskin-v-brown-appellants-brief. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

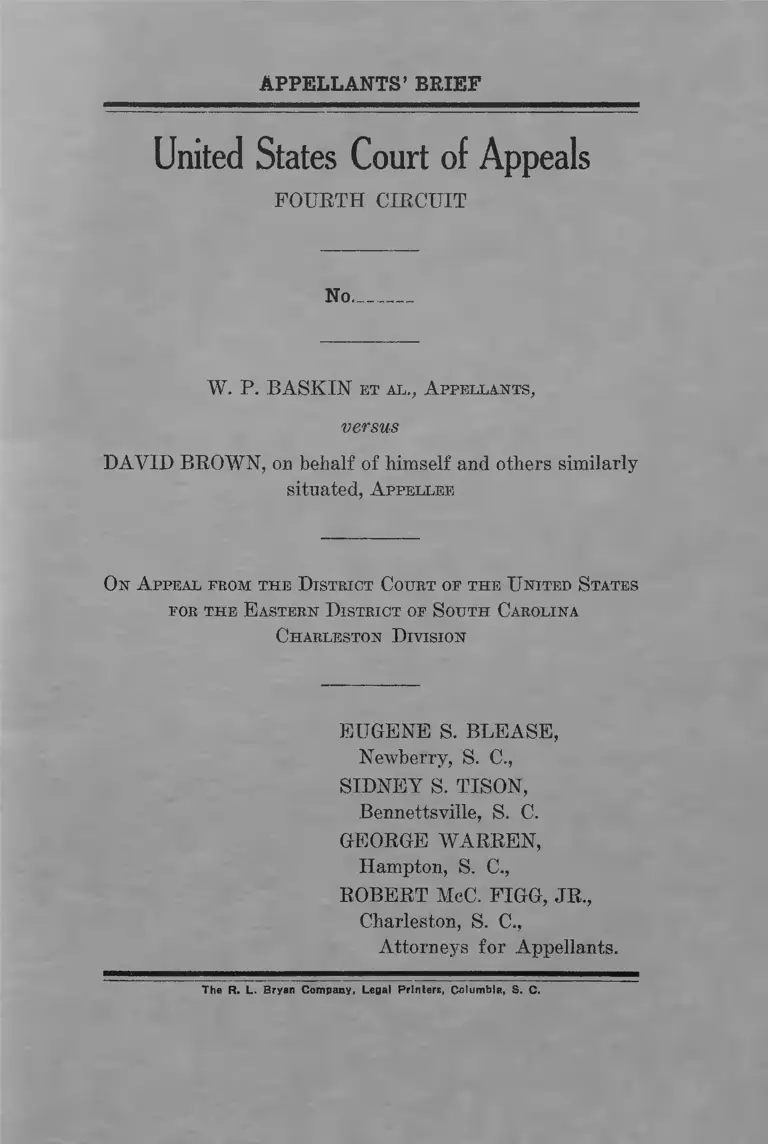

APPELLANTS' BRIEF

United States Court of Appeals

FOURTH CIRCUIT

No______

W. P. BASKIN et al., A ppellants,

versus

DAVID BROWN, on b eh a lf o f h im se lf and o th e rs s im ila r ly

s itu a te d , A ppellee

On A ppeal eeom t h e D istrict Court of t h e U nited S tates

fob t h e E astern D istrict of S outh Carolina

Charleston D ivision

EUGENE S. BLEASE,

Newberry, S. C.,

SIDNEY S. TISON,

Bennettsville, S. C.

GEORGE WARREN,

Hampton, S. C.,

ROBERT MeC. FIGG, JR.,

Charleston, S. C.,

Attorneys for Appellants.

The R. L. Bryan Company, Legal Printers, Columbia, S. C.

INDEX

P AGE

Introductory Summary......... ......................................... 1

Questions Involved............................................. 3

Statement of F a c ts ......... ................................................ 4

Argument:

Question I ......................................................... 16

Question II ............................................................ 22

Question III .................................................. 36

Question I V ............................................................. 38

Conclusion ............................... 45

(i)

TABLE OF CASES

P age

Berger v. United States, 225 U. S. 22, 41 S. Ct. 230, 65 L.

Ed. 481.................................................... . 17, 21,

Brown v. Baskin, 78 F. Supp. 933 ..................................

Brown v. Baskin, 80 F. Supp. 1017..............................

Davis v. Hambrick, 109 Ky. 276, 58 S. W. 779, 22 Ivy.

Law Bep. 815, 51 L. R. A. 671 ..............................

De Jonge v. State of Oregon, 299 U. S. 353, 57 S. Ct. 255,

81 L. Ed. 278 ..............................................................

Elmore v. Rice, 72 F. Supp. 516 . . . .4, 8, 10, 12, 15, 19,

Harrell v. Sullivan, 220 Ind. 108, 40 N. E. (2d) 115, 41

N. E. (2d) 354, 140 A. L. R. 455 ...........................

Henry v. Speer, 201 Fed. 869 ........................................

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242, 57 S. Ct. 740, 81 L. Ed.

1066 ..................... ...................................................

Hicklin v. Coney, 290 U. S. 169, 54 S. Ct. 142, 78 L. Ed.

247 ......................................................... .................

Ingersoll v. Curran, 70 N. Y. S. (2d) 435,188 Misc. 1003,

affirmed 297 N. Y. 522, 74 N. E. (2d) 405 ...........26,

Ingersoll v. Heffernan, 71 N. Y. S. (2d) 687, 188 Misc.

1047, affirmed 297 N. Y. 524, 74 N. E. (2d) 466 . .25,

Judicial Code, Section 21 .............................................

Kelso v. Cook, 184 Ind. 173, 110 N. E. 987, Ann. Cas.

1918E 6 8 ......... ;........................................................

In Re: Newkirk, 259 N. Y. S. 434, 144 Misc. 765 . . . .28,

People ex rel Lindstrand v. Emmerson, 333 111. 606, 165

N. E. 217, 62 L. R. A. 912 ...........................25, 28,

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. (2d) 387 ----5, 38, 39, 41, 42, 43,

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, 64 S. Ct. 757, 88 L.

Ed. 987,151 A. L. R. 1110......................................4,

Smith v. Howard, 275 Ky. 165, 120 S. W. (2d) 1040 . . . .

Socialist Party v. Uhl, 155 Cal. 776,103 Pac. 181 . . . .26,

22

2

15

27

24

38

40

17

24

24

28

28

16

25

38

40

45

44

27

28

(iii)

TABLE OF CASES—Continued

P age

South Carolina Code of Laws:

Section 1269 ......................................;.................... 31

Section 1271................. 32

Section 1272 ......................................... 30

Section 8396 ................. 31

Section 8403 .............. 31

Section 8490 ................. 31

Section 8530-1 ..................................... 31

South Carolina Constitution:

Article III, Section 3 3 ................ ............................ 30

Article XI, Section 7 .............................................. 30

State v. Messervy, 86 S. C. 503, 68 S. E. 766 ................. 41

State of Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337,

59 S. Ct. 232, 83 L. Ed. 208 ................................ 30, 32

State ex rel Tamminen v. Eveleth, 189 Minn. 229, 249

X. W. 184, 99 A. L. E. 289 ..................................... 42

Tinsley v. Kirby, 17 S. C. 1 ........................................... 41

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299, 61 S. Ct. 1031,

85 L. Ed. 1368 ....................................................42, 44

United States v. Eoyer, 268 U. S. 394, 45 S. Ct. 519, 69

L. Ed. 1011.............................................................. 42

United States Code, Title 28, Section 144..................3, 16

United States Constitution:

Amendment XIX .................................................... 35

Werbel v. Genrstein, 78 X. Y. S. (2d) 440,191 Misc. 275,

affirmed 273 App. Div. 917, 78 X. Y. S. (2d) 926 .28, 38

Whitaker v. McLean, 118 F. (2d) 596 ....................... 18, 22

Zuckman v. Donahue, 79 X. Y. S. (2d) 169,191 Misc. 399,

order modified 274 App. Div. 216, 80 X. Y. S. (2d)

698 ....................................................................... 28, 38

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

United States Court of Appeals

FOURTH CIRCUIT

No.

W . P. BASKIN et al., A ppellants,

versus

DAVID BROWN, on b eh a lf of h im self an d o th e rs s im ila r ly

s itu a ted , A ppellee

On A ppeal from th e D istrict Court of t h e U nited S tates

for th e E astern D istrict of S outh Carolina

Charleston D ivision

INTRODUCTORY SUMMARY

This action was commenced on July 8, 1948, by appel

lee, a Negro qualified elector under the Constitution and

laws of the State of South Carolina, on behalf of himself

and others similarly situated, against appellants, who are

state and county officers of the Democratic Party of South

Carolina, seeking a declaratory judgment that certain rules

of that party being enforced by appellants as party officers

violate appellee’s asserted rights under Sections 2 and 4

of Article I of the Constitution of the United States, and

2 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

the Fourteenth, Fifteenth and Seventeenth Amendments

thereto, and also Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8 of the United

States Code.

A temporary injunction was granted on July 19, 1948,

restraining the enforcement of the rules in controversy

pending the final determination of the action. Brown v.

Baskin, 78 F. Supp., 933. This injunction was obeyed in

the conduct of the primaries of the Democratic Party of

South Carolina held in the summer of 1948. Brown v. Bas

kin, 80 F. Supp., 1017, 1018.

An affidavit was filed on October 20, 1948, by John E.

Stansfield that he was informed and believed, on the basis

of certain facts set forth therein, that District Judge War

ing, before whom the cause was pending and scheduled to

be heard, had a personal bias and prejudice in favor of ap

pellee and against him and the other appellants by reason

of which the said District Judge might be prevented from

or impeded in rendering judgment impartially between the

parties. On October 22, 1948, Judge Waring filed an order

refusing to disqualify himself.

The cause was heard on its merits by Judge Waring

on November 23, 1948, on the pleadings and a stipulation

between counsel for the parties as to the facts, which stipu

lation incorporated the testimony of appellee and appel

lant Baskin taken July 16, 1948, at the hearing on the tem

porary injunction, and also the platform, principles, and

rules of the Democratic Party of South Carolina, which

were attached as an exhibit to the return filed by appellants

at such hearing.

On November 26, 1948, Judge Waring filed his final

order, which in substance permanently restrained and en

joined the enforcement of the party rules in controversy.

Baskin et a t, Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 3

Within the proper time, a notice of appeal to this court

was filed by appellants from the denial of the application

for disqualification, and from the orders dated July 19,

1948, and November 26, 1948, and the findings of fact, con

clusions of law and opinions on which the same were based.

QUESTIONS INVOLVED

I. The Stansfield affidavit was legally sufficient under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 144 (and Judicial

Code, Section 21, 28 U. S. C. A., Section 25); and District

Judge Waring should have proceeded no further in the

cause.

II. The Democratic Party of South Carolina is a po

litical party, having the right as such to limit membership

in it and participation in its party actions by voting in its

primaries to those who are in sympathy with its principles

and the purpose of fostering and effectuating them; and

the District Judge erred in enjoining the enforcement of

the portion of Rule 6 of the party rules which limits mem

bership to those who subscribe to the principles of the

party as declared by the State Convention and Rule 36 of

the party rules which prescribes the voter’s oath.

III. The Democratic Party of South Carolina, as a

political party, had the right to adopt in its State Conven

tion political and governmental principles and objectives

of the party relating to the separation of the races, States’

Rights and the Federal so-caled F. E. P. C. law, and

to exclude from membership and from voting in its pri

maries appellee and others similarly situated who did not

believe in and were not in sympathy with such lawful po

litical and governmental objectives; and the District Judge

erred in holding to the contrary and rendering judgment in

favor of appellee.

4 Baskin et al, Appellants, v . Brown, Appellee

IV. The general election is the only election machinery

provided by the Constitution and laws of the State of

South Carolina; and the District Judge erred in holding

that the primaries of the Democratic Party of South Caro

lina, conducted and held under party rules alone, are an

integral part of the election machinery of the State, to

which Article I and Amendments Fourteen, Fifteen and

Seventeen of the Constitution of the United States and

Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8 of the United States Code are

applicable.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Shortly after the decision in Smith v. Allwright, 321

U. S., 649, 64 S. Ct., 757, 11 L. Ed., 987, 151 A. L. R., 1110,

the General Assembly of the State of South Carolina re

pealed all state laws relating to party primary elections,

including those punishing fraud at the same, and the Con

stitution of the State was duly amended in accordance with

its provisions as to amendment so as to eliminate therefrom

the provision reading:

“ The General Assembly shall provide by law for

the regulation of party primary elections and punish

ing fraud at the same.”

In 1944 and in 1946 the primaries of the Democratic

Party of South Carolina were held under party rules

adopted at the party’s biennial State Conventions. Such

rules restricted enrollment in the party to white Democrats,

and restricted the right to vote in its primaries to those

enrolled.

In Elmore v. Bice et al., 72 F. Supp., 516, an action for

a declaratory judgment brought to test the legality of the

action of the election managers of a precinct in Richland

County, South Carolina, and of the members of that coun

ty ’s Democratic Executive Committee in not permitting

Baskin et a t, Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 5

Elmore and other qualified Negro electors to vote in the

primary held on August 13, 1946, the District Court held:

“ I am of the opinion that the present Democratic

Party in South Carolina is acting for and on behalf of

the people of South Carolina; and that the Primary

held by it is the only practical place where one can

express a choice in selecting federal and other officials.

Racial distinctions cannot exist in the machinery that

selects the officers and lawmakers of the United States;

and all citizens of this State and County are entitled

to cast a free and untrammeled ballot in our elections,

and if the only material and realistic elections are

clothed with the name ‘primary’, they are equally en

titled to vote there.”

The District Court’s decision was affirmed by this

Court in Bice v. Elmore, 165 P. (2d), 387, and certiorari

was denied, 333 U. S., 875, 68 S. Ct., 905.

The State Convention of the Democratic Party of

South Carolina was held next on May 19,1948. The conven

tion adopted a party Platform, a statement of the party’s

Principles, and a set of Rules governing the holding of the

party’s primaries that year.

The party Platform (found on page 28 of the “ Rules

of the Democratic Party of South Carolina,” attached as

an exhibit to the return to rule to show cause, pages 26-30

of the record), includes statements that

“ We believe in States’ Rights and local self gov

ernment, and are opposed to the Federal Q-overnment

assuming any powers except those expressly granted

it by the states in the Federal Constitution,”

and

“ We believe in the social and educational separa

tion of races. ’ ’

6 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

The statement of the party’s principles declared by

the state convention (found on page 29 of the Rules), in

cluded the statements above quoted from the Platform, and

a further statement that

“ We oppose any Federal legislation setting up

the proposed so-called F. E. P. C. Law.”

The party Rules adopted contain the following provi

sions :

Oath required to be subscribed to by all candidates:

(Rule 29):

“ As a candidate for the office of_________________

in the Democratic Primary to be held o n ______ day of

------------------------------------ } 19------ } I h e reb y p led g e m y self to

abide the results of such primary, and support the nominees

of this primary, and the political principles and policies

of the Democratic Party of South Carolina, during the term

of office for which I may be elected, and I declare that I

am a Democrat and that I am not, nor will I become the can

didate of any faction, either privately or publicly sug

gested, other than the regular Democratic Party of South

Carolina.”

Oath required to be taken by the voting precinct man

agers (Rule 35):

“ We do solemnly swear that we will conduct this pri

mary according to the rules of the party; and will allow no

person to vote whose name is not regularly enrolled in this

club, or who is not a qualified Negro elector, and we will

not assist any voter to prepare his ballot and will not ad

vise any voter as to how he should vote at this primary.”

Oath required to be signed by each voter: (Rule 36)

“ I do solemnly swear that I am a resident of this club

district, that I am duly qualified to vote in this primary

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 7

under the rules of the Democratic Party of South Caro

lina, and that I have not voted before in this primary, and

that I am not disqualified from voting under Section 2267

of the South Carolina Code of Laws, 1942, relating to dis

qualifying crimes.

“ I further solemnly swear that I (understand and)

believe in and will support the principles of the Democratic

Party of South Carolina, and that I believe in and will sup

port the social (religious) and educational separation of

races.

“ I further solemnly swear that I believe in the princi

ples of States’ Rights, and that I am opposed to the pro

posed Federal so-called F. E. P. C. Law.

“ I further solemnly swear that I will support the elec

tion of the nominees of this primary in the ensuing general

election, and that I am not a member of any other political

party. ’ ’

N ote: The words in parenthesis were eliminated by

action of the party’s State Executive Committee, were not

proposed to be enforced or administered by the appellants,

and were not contained in the Rules as printed by the Party

officials.

Qualifications for club membership: (Rule 6)

“ The applicant for membership shall be twenty-one

(21) years of age, or shall become so before the succeeding

general election, and be a white Democrat, who subscribes

to the principles of the Democratic Party of South Caro

lina, as declared by the State Convention. He shall be a

citizen of the United States and of the State of South Caro

lina, and shall be able to read and write and interpret the

Constitution of the State of South Carolina. No person

shall belong to any club unless he has been a resident of

8 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

the State of South Carolina for two (2) years, of the

County for six (6) months prior to the succeeding general

election, and of the club district for sixty (60) days prior

to the first primary following his offer to enroll. Provided,

that public school teachers, and ministers of the gospel in

charge of a regular organized church, shall be exempt from

the provisions of this rule as to residence, if otherwise

qualified.”

Qualifications for voting in the party primary: (Eule 7)

“ All duly enrolled club members are entitled to vote

in the precinct of their residence, if they take the oath re

quired of voters in the primary; and in conformity with

the Order of Judge J. Waties Waring, United States Dis

trict Judge, in the case of Elmore, etc., v. Rice et al., all

qualified Negro electors of the State of South Carolina are

entitled to vote in the precinct of their residence, if they

present their general election certificates and take the oath

required of voters in the primary.”

Appellee, a Negro qualified elector under the Con

stitution of the State, enrolled as a member of the local

club of the party at Beaufort, S. C., and on or about July

2, 1948, his enrollment was cancelled under Eule 6, because

he was not eligible to enroll thereunder.

He instituted this action on July 8, 1948, seeking a de

claratory judgment that the provision in Eule 6 restricting

party membership to white. Democrats, the provision in

Eule 7 requiring Negro voters to present their general elec

tion registration certificates and take the oath required of

voters, and the voter’s oath prescribed by Eule 36, as ap

plied to Negro voters, are each violative of his rights under

the Constitution and laws of the United States.

The District Court made an order dated July 19, 1948,

enjoining the appellants, their agents, servants, employees

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 9

and attorneys pending the determination of this action

from refusing to enroll Negroes as members of local clubs

and the Democratic Party of South Carolina because of

race and color, and from denying to them full and complete

participation in the said party without distinction because

of race, color, creed, or condition, and from enforcing the

rule requiring Negro electors to present general election

certificates as a prerequisite to voting in the August 10th

primary, and from requiring plaintiff and other Negro elec

tors to take the voter’s oath as a prerequisite to voting in

primary elections, and from requiring of prospective voters

in Democratic primaries of South Carolina any oath other

than that the prospective voter meets the qualifications of

an elector as set out in the Constitution of South Carolina,

and is a Democrat and will support the election of the nomi

nees of the Democratic party at the ensuing general elec

tion.

The temporary injunction also required the enrollment

books, which had already been closed under the applicable

rule provisions, to be reopened for the enrollment of indi

viduals who meet the qualifications for electors as set out

in the Constitution of South Carolina without distinction

as to race, color, creed, or condition.

Three days later, on July 22, 1948, the District Court

of its own motion made another order modifying the tem

porary injunction by striking out the portion thereof relat

ing to the voter’s oath and inserting a new paragraph read

ing as follows:

“ 5. From requiring voters or prospective voters in

Democratic Primaries of South Carolina to take any oath

setting out any beliefs or pledges as a prerequisite to en

rolling and voting, except that the defendants may (but

they are not required) require an oath in part or in whole

containing the following:

10 Baskin et til., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

“ ‘1. That the voter has the requisite residence,

and has lived the legal time within the State, County

and precinct, or other voting subdivision, and is quali

fied to vote at the primary election.

“ ‘2. That he has not voted before in that particu

lar election.

“ ‘3. That he pledge himself to support the nomi

nees of that primary.’

“ It is reiterated that it is optional with the defendants

to require an oath containing the whole or any part or parts

of the foregoing, or to forego requiring any oath at all. ’ ’

It will be observed that the modifying order eliminates

the portion of the original temporary injunction which per

mitted the voter’s oath to contain a provision that the pro

spective voter is a Democrat.

As was the case in Elmore v. Rice, supra, the complaint

was predicated upon allegations (paragraphs 9 and 10)

that the only material and realistic elections in South Car

olina, and the only elections at which plaintiff and others

on whose behalf he sues can make a meaningful choice and

exercise their right to vote, are the Democratic primaries;

that the Democratic primary in South Carolina is an in

tegral part of the election machinery of the state; that the

Democratic Party of South Carolina is an organization act

ing for and on behalf of the people of South Carolina; that

the primary conducted by said organization for and on be

half of the people of South Carolina is the only election

where the appellee and other qualified electors can express

a meaningful choice in selecting federal and state officers;

and that the appellants, in performing their duties as offi

cers of the Democratic Party of South Carolina, including

the conducting of primary elections, are performing an im

portant governmental function essential to the exercise of

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 11

sovereignty by the people, and in doing so are subject to

the provisions of the United States Constitution.

The answer of the appellants, in paragraph Seventh of

the Fourth defense, denies these allegations, and on the con

trary alleges and shows that the elections provided by law

in South Carolina are the general elections established by

the Constitution and Statutes of the State; that that Con

stitution and those Statutes make no mention of, and do not

provide for, and do not regulate the primaries held by the

Democratic Party of South Carolina under party rules and

procedure adopted at the party’s state convention; that the

Democratic Party and the Democratic primary do not be

come the property of every person in the state simply be

cause the members of that party have been the only ones

who have had the character, ability, vigor and community

of interests to associate themselves together as citizens to

exercise their constitutional right to work together for

public and governmental principles and objectives; and that

any contention or holding to the contrary is believed by the

appellants to be in derogation of their constitutional rights.

The complaint also alleges (paragraphs 16 and 17) that

the denial to Negroes of the right to enroll in party clubs

of the Democratic Party of South Carolina, and requiring

all Negro electors to present general election certificates as

a prerequisite to voting, effectually limits their right to

vote in primary elections to select federal and state officers

and their participation in other particulars in the election

machinery of the State of South Carolina; and being based

solely on race or color is in violation of Article I and

Amendments Fourteen, Fifteen and Seventeen of the Con

stitution of the United States and Sections 31 and 43 of

Title 8 of the United States Code.

The answer (paragraph Tenth) denies these allega

tions, on information and belief, and alleges that the ap-

12 Baskin et a t, Appellants, v . Brown, Appellee

pellants did not and do not construe the decisions in the

case of Elmore v. Bice to hold that the Democratic Party

of South Carolina was no longer a political party which

could restrict its membership to those in sympathy with

its principles and the purpose of fostering and effectuating

them, but only as holding that Negroes who were qualified

electors must be given the right to vote in its primaries,

which are governed by the rules adopted by the state con

vention of the Democratic Party of South Carolina, and that

the requirement of producing general election certificates

was merely a procedural requirement in reference to the

person seeking to vote evidencing the right to do so.

The complaint (paragraph 18) alleges that the oath re

quired of voters in primary elections ‘ ‘ that I believe in and

will support the social and educational separation of races, ’ ’

and “ I further solemnly swear that I believe in the prin

ciples of States’ Eights, and that I am opposed to the pro

posed Federal so-called F.E.P.C. Law” is aimed directly

at continuing the disfranchisement of appellee and other

qualified Negro electors despite prior rulings of this and

other Federal courts, and is a test not relevant to qualifi

cations to vote, is an unconstitutional test and condition

for the exercise of the right to suffrage, is based on race

and color, and is in violation of Article I and Amendments

Fourteen, Fifteen and Seventeen of the United States Con

stitution and Sections 31 and 43 of Title 8 of the United

States Code.

The answer (paragraph Eleventh) denies these allega

tions on information and belief, and alleges that the appel

lants and all other members of the Democratic Party of

South Carolina have the constitutional right to associate

themselves together in party membership for the purpose

of supporting and working for lawful principles and gov

ernmental objectives in which they may believe, and to

Baskin et a l, Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 13

foster and effectuate which they may desire to work to

gether, and that they have the right to make a condition of

membership in such political party sympathy with its prin

ciples and the purpose of fostering and effectuating them,

and that the oath prescribed by the state convention, and

referred to in the said paragraph of the complaint, was

a proper and legitimate exercise of that right, at least so

far as enrolling and becoming members of the said party

is concerned, and that to deny them this right is to hold

that they are compelled to admit to membership in their

party those who are not in sympathy with its principles and

governmental objectives, but seek only to thwart and de

stroy them.

This paragraph of the answer also alleges that it is

well known that the Democratic Party is a party which has

advocated a strict construction of the Constitution, sharp

limitation of the powers of the Federal Government, and

a broad construction of the reserved right of the states; and

that the membership of the Democratic Party of South Car

olina, they are informed and believe, had and have the right

to compel a prospective member of the party to attest his

adherence to such principles, either stated generally or

specifically, in an appropriate manner as a condition of

membership.

The second defense in the answer alleges that the ap

pellee and many of those for whom he sues are members

of another political party, namely, the Progressive Dem

ocratic Party, which party is not in sympathy with the

fundamental principles and governmental objectives of the

Democratic Party of South Carolina, such as the opposition

of the Democratic Party of South Carolina to the proposed

Federal F.E.P.C. law, and other federal laws usurping or

encroaching upon the sovereignty of the States of the

Union and of the rights of the states and of the people pre-

14 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

served in and by the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, and such as the adherence of the Dem

ocratic Party of the State of South Carolina to the prin

ciple of States’ Eights, and such as the adherence of the

Democratic Party of South Carolina to the principle of so

cial and educational separation of the races, and opposition

to federal law interfering with state and local laws in ref

erence to the separation of the races; that the Democratic

Party of South Carolina and these appellants and other

members of it have the right to restrict membership in the

said party to those who are in sympathy with its principles

and the purpose of fostering and effectuating them, and

that these appellants are informed and believe that the ap

pellee and other members of the Progressive Democratic

Party, and other persons who do not adhere to and believe

in the principles of the Democratic Party of South Caro

lina, have no constitutional or legal right to membership in

the Democratic Party of South Carolina.

Deference is made in the introductory summary above

to the affidavit filed by the appellant John E. Stansfield on

October 20, 1948, seeking the disqualification of District

Judge Waring to hear and determine the cause. This affi

davit was based upon a newspaper account of a speech made

by Judge Waring in October, 1948, at a luncheon in his

honor given by the New York Chapter of the National Law

yers Guild, in reference to the racial problem in the South

and its solution. The newspaper account stated that in the

course of his address Judge Waring turned to Thurgood

Marshall, attorney for the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored people, and one of appellee’s coun

sel in this cause, and said:

“ The danger of Arnall and others is that they say: ‘Let

us alone and we will do it ourselves’. Well, no Negro would

have voted in South Carolina if you hadn’t brought a case.”

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 15

The affidavit also made reference to certain statements

made by Judge Waring at the hearing on the temporary in

junction, July 16, 1948, in which he thanked counsel for

some other defendants on behalf of the government and on

behalf of America for a return showing that the party rules

were not being enforced in three counties of the state; ex

pressed his opinion that the party leaders, the appellants

here, had made a deliberate attempt to evade the spirit of

the opinion in Elmore v. Rice; and, in reference to the

voter’s oath, stated to the appellants that “ I t ’s a disgrace

and a shame that you have got to come into court and ask

one judge to tell you to be an American and to obey the

law. ’ ’

Prior to the hearing on the merits, a stipulation of

facts was entered into by counsel for the parties, and filed

November 23,1948, which incorporated the testimony given

by appellee and by appellant Baskin at the hearing on July

16, 1948, at which appellee admitted that he was a member

of the Progressive Democratic Party of South Carolina,

which had nominated and supported a candidate against the

candidate of the Democratic Party of South Carolina for

United States Senator.

The case was heard on its merits by Judge Waring on

November 23, 1948, and his final order together with the

findings of fact, conclusions of law and opinion on which it

was based was filed on November 26th, 1948. Brown v. Bas

kin, 80 F. Supp. 1917.

The final order permanently restrained and enjoined

the appellants, together with their agents, servants, em

ployees and attorneys and all persons in active concert and

participation with them from:

1. Refusing to enroll Negroes as members of local clubs

of the Democratic Party of South Carolina, because of race

and color; and

16 Baskin et al., Appellants, v . Brown, Appellee

2. From denying to the plaintiff and others on whose

behalf he sues from (sic) full and complete participation in

the Democratic Party of South Carolina without distinction

because of race, color, creed, or condition; and

3. From enforcing the rules of the Democratic Party

of South Carolina requiring Negro electors to present gen

eral election certificates as a prerequisite to voting in any

primary election unless the same requirement applies to all

other persons;

4. From requiring the plaintiff and other Negro elec

tors to take the voter’s oath prescribed in Rule 36 of the

party rules as a prerequisite to voting in primary elections;

and

5. From requiring of members of the Democratic Party

or of prospective voters in Democratic Primaries in South

Carolina any form of pledge or oath which attempts to re

quire them to support racial or religious discrimination in

violation of the Constitution or laws of the United States.

6. From ordering or maintaining any different require

ments for exercising the right of suffrage in Democratic

Primary elections and in party participation because of

race or religion.

ARGUMENT

I

The Stansfield affidavit was legally sufficient under

title 28, United States Code, section 144 (and Judicial Code,

Section 21, 28 U. S. C. A., Section 25); District Judge

Waring should have proceeded no further in the cause.

Judicial Code, section 21, 28 U. S. C. A., section 25,

was superseded by section 144 of new title 28, Judiciary

and Judicial Procedure. Act June 25, 1948, c. 646, section

39, 62 Stat. 922, effective September 1, 1948.

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 17

It would not seem, however, that the phrase “ timely

and sufficient affidavit” in section 144 enlarges the function

of a District Judge in passing on the sufficiency of affidavit

filed thereunder.

In Berger v. United States, 255 IT. S., 22, 41 S. Ct., 230,

65 L. Ed., 481, the Court approved the following statement

as to sufficiency contained in Judge Meek’s opinion for the

Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Henry v.

Speer, 201 Fed., 869: (p. 32, of 255 U. S.)

“ Upon the making and filing by a party of an af

fidavit under the provisions of section 21, of necessity

there is imposed upon the judge the duty of examining

the affidavit to determine whether or not it is the af

fidavit specified and required by the statute and to de

termine its legal sufficiency. If he finds it to be legally

sufficient then he has no other further duty to perform

than that prescribed in section 20 of the Judicial Code.

He is relieved from, the delicate and trying duty of de

ciding upon the question of his own disqualification.”

The Court held: (p. 35 of 255 U. S.)

“ We are of opinion, therefore, that an affidavit

upon information and belief satisfies the section and

that upon its filing, if it show the objectionable incli

nation or disposition of the judge, which we have said

is an essential condition, it is his duty to ‘proceed no

further’ in the case. And in this there is no serious

detriment to the administration of justice nor incon

venience worthy of mention, for of what concern is it

to a judge to preside in a particular case; of what con

cern to other parties to have him so preside?”

And further: (p. 36 of 255 U. S.)

“ To commit to the judge a decision upon the truth

of the facts gives chance for the evil against which the

section is directed. The remedy by appeal is inade

quate. It comes after the trial and, if prejudice exist, it

has worked its evil and a judgment of it in a review-

18 Baskin et al., Appellants, v . Bkown, Appellee

ing tribunal is precarious. It goes there fortified by

presumptions, and nothing can be more elusive of esti

mate or decision than a disposition of a mind in which

there is a personal ingredient.”

The court said (p. 35 of 255 U. S.) that the solicitude

of the statute

“ is that the tribunals of the country shall not only

be impartial in the controversies submitted to them but

shall give assurance that they are impartial, free, to

use the words of the section, from any ‘bias or prej

udice’ that might disturb the normal course of impar

tial judgment. ’ ’

The new section changes neither the provision of the

old section as to the time of filing nor the provision as to

the contents of the affidavit.

It seems clear, therefore, that the words “ timely” and

‘ ‘ sufficient ’ ’ are both used in the light of the decisions inter

preting the meaning of the old section, and were not in

tended to extend the judge’s authority to consider the af

fidavits beyond that conferred upon him by section 21 of

the Judicial Code.

In Whitaker v. McLean, 118 F. (2d), 596, the disquali

fying affidavit was based upon remarks made by the trial

judge in the absence of the jury. In reversing the judgment

of the District Court, the Court of Appeals for the District

of Columbia said:

“ The judge may, as indeed he insisted, have felt

no hostility to the plaintiff, and in that view he was,

subjectively, free from bias. But bias must be con

sidered objectively. Few, if any, judges would make

the reported remarks, in the course of a trial, unless

they had developed definite and positive hostility to

plaintiff and his case. Hostility is a form, of bias. * # *

Often some degree of bias develops inevitably during

a trial. Judges cannot be forbidden to feel sympathy

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 19

or aversion for one party or the other. Mild expres

sions of feeling are as hard to avoid as the feeling it

self. But a right to be tried by a judge who is reason

ably free from bias is a part of the fundamental right

to a fair trial. If, before a case is over, a judge’s bias

appears to have become overpowering, we think it dis

qualifies him. It follows that the judgment must be

reversed. This is the more regrettable because it is our

impression, based on an examination of the record,

that the claim on which the plaintiff sued was probably

without merit.”

The affidavit of the appellant Stansfield sets forth

statements made by Judge Waring on July 16, 1948, and

also an account from the New York Times of a speech made

by Judge Waring at a luncheon in his honor given by the

National Lawyers Guild in New York during the month of

October, 1948.

The affidavit shows that on July 16th, before hearing

from counsel for the appellants on their return to the rule

to show cause why an injunction pendente Lite should not

be granted, Judge Waring expressed himself as gratified

with the returns made by the party officials of three coun

ties showing that they were not enforcing the party rules

in their counties. He said that he was proud that the gov

erning body of these counties had “ sense enough, nerve

enough and patriotism enough to make a true, fair and just

decision” . He thanked their counsel for the return, “ not

personally, but on behalf of the Government and on behalf

of America” . He expressed the hope that the press would

publish the whole or excerpts of the returns made by these

three counties “ and my brief remarks in regard to them”.

He next stated that the “ leaders of the party”, ob

viously referring to the appellants, had made “ a deliberate

attempt to evade the spirit of the opinion” in Elmore v.

Rice.

20 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

Finally, lie said of appellants

£ 4 I t ’s a disgrace and a shame that you’ve got to

come into Court and ask one Judge to tell you to be

an American and to obey the law.”

In the New York speech, Judge Waring discussed his

views on the racial problem in the South in considerable

detail. He stated that to him 4 4 the racial atmosphere of

my part of the South is at present pretty dim” , and that

he did not believe “ that the windows are going to be opened

voluntarily” . He said that the most discouraging aspect

is the attitude of the majority of white Southerners, and

that 44the problem is to change the feeling, the sentiment,

the creed, of the great body of white people of the South

that a Negro is not an American citizen” .

He said:

4 4 My people have one outstanding fault—the ter

rible fault of prejudice. They have been born and edu

cated to feel that a Negro is some kind of an animal

that ought to be well-treated and given kindness, but

as a matter of favor, not right.”

With reference to the instant cause, he made two state

ments. “ Referring to his decisions in the United States

District Court in Charleston which outlawed bans on Negro

primary voting,” he said:

4 4 Not one man in public life has dared to support

these decisions based on the fact that a Negro is en

titled to vote as an American citizen. The few people

in public life who have communicated with me have

done so in letters marked ‘strictly confidential’. That’s

pretty bad. ’ ’

During the speech, turning to Thurgood Marshall, at

torney for the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, a member of the Lawyers Guild execu

tive board who was seated near him, the judge said:

Baskin et til., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 21

“ ‘The danger of Arnall and others is that they

say: “ Let us alone and we’ll do it ourselves.” Well,

no Negro would have voted in South Carolina if you

hadn’t brought a case’.”

The affidavit states that, upon considering the account

of Judge Waring’s speech in the light of the statements

made at the July 16 hearing, the deponent came to the def

inite and positive conclusion that Judge Waring had a

personal bias in favor of the appellee and his success in

the cause, and a personal bias and prejudice against de

ponent and the other appellants regarding the justiciable

matter pending, as a result of which they cannot expect an

impartial judgment of the issues.

The remarks made on July 16 evidenced positive hos

tility to the appellants or their cause of the same quality as

that which the Supreme Court of the United States found

legally sufficient in Berger v. United States, supra. It is

inconceivable that such hostility would not prevent a judge

from or impede him in rendering judgment impartially

between the parties to the cause. His remarks in the New

York speech certainly did nothing to militate against such

a conclusion.

In the New York speech, he placed himself in a posi

tion where he would later make himself look ridiculous, to

say the least, if he decided the cause against the appellee.

He publicly referred to this very cause, and by the clearest

kind of implication commanded both the bringing of it and

the decision. From that moment on, human nature being as

it is, he was under a distinct kind of duress against deciding

it differently on the merits. From then on it could not be

said that his mind was devoid of “ a personal ingredient ’ ’,

and the appellants were entitled to a trial before another

judge. They should not have labored under the burden of

22 Baskin et al., Appellants, v . Brown, Appellee

convincing the judge against a stand in this very cause

which he had publicly taken.

It is respectfully submitted that Judge Waring’s duty,

on the filing of the affidavit in the cause, was to “ proceed

no further therein” .

Berger v. United States, supra.

Whitaker v. McLean, supra.

II

The Democratic Party of South Carolina is a political

party, having the right as such to limit membership in it,

and participation in its party actions by voting in its pri

maries, to those who are in sympathy with its principles

and the purpose of fostering and effectuating them; and the

District Judge erred in enjoining the enforcement of the

portion of Rule 6 of the party rules which limits member

ship to those who subscribe to the principles of the party

as declared by its State Convention and Rule 38 of the Party

rules which prescribes the voter’s oath.

This question deals with the validity of that portion of

Rule 6 of the party rules restricting membership in the

party to those who subscribe to “ the principles of the

Democratic Party of South Carolina, as declared by the

State Convention.”

It also deals with the validity of Rule 36, which, to

gether with Rule 7, restricts voting in the primaries of the

party to those who take the voter’s oath therein prescribed,

as follows:.

“ I do solemnly swear that I am a resident of this

club district, that I am duly qualified to vote in this

primary under the rules of the Democratic Party of

South Carolina, and that I have not voted before in

this primary, and that I am not disqualified from vot-

Baskin et al., Appellants, v , Brown, Appellee 23

ing under Section 2267 of the South Carolina Code of

Laws, 1942, relating to disqualifying crimes.

“ I further solemnly swear that I believe in and

will support the principles of the Democratic Party

of South Carolina, and that I believe in and will sup

port the social and educational separation of races.

“ I further solemnly swear that I believe in the

principles of States’ Rights, and that I am opposed

to the proposed Federal so-called F. E. P. C. law.

“ I further solemnly swear that I will support the

election of the nominees of this primary in the ensuing

general election, and that I am not a member of any

other political party.”

The District Judge, both in his order and opinion filed

July 19, 1948, and in his order and opinion filed November

26, 1948, held that membership and the privilege of voting

in the party’s primaries could not validly be conditioned

on belief in the party’s principles in relation to the separa

tion of the races, States’ Rights, and opposition to Federal

F. E. P. C. legislation.

He said: (p. 1019 of 80 F. Supp.)

“ The proposed oath cannot be said to have any

purpose other than the exclusion of Negro voters. * * *

It is common knowledge of which this Court may take

judicial cognizance that the proposed Federal FEPC

is legislation proposed to prevent discrimination of

employment according to race. Of course, every one

knows that a Negro would not take a solemn oath that

he is opposed to legislation that would remove dis

crimination against him. And there are even stronger

reasons why he would not take an oath that he believes

in and will support ‘the social, religious and educa

tional separation of races’.”

(The word “ religious” appears in the District Court’s

opinion because it originally appeared in the rules as they

were adopted at the State Convention but was afterwards

24 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

deleted by action of the State Executive Committee and

was not printed in the final version of the Rules. The Dis

trict Judge held that they did not have power to eliminate

this word, and reinstated it and then enjoined its enforce

ment by the appellants. Since they had already taken ac

tion not to administer this portion of the oath, there was

certainly no necessity for bringing it back into the oath for

the purpose of enjoining it. Hicklin v. Coney, 290 U. S.

169, 172, 54 S. Ct. 142, 144, 78 L. Ed. 247.)

The appellants contend that the right to organize a

political party, to associate in party membership for the

purpose of supporting and working for lawful political

principles and governmental objectives, is a constitutional

right.

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242, 259, 57 S. Ct. 732,

740, 81 L. Ed. 1066.

In De Jonge v. State of Oregon, 299 IT. S. 353, 57 S.

Ct. 255, 81 L. Ed. 278, the Court said:

“ The right of peaceable assembly is a right cog

nate to those of free speech and free press and is

equally fundamental. As this Court said in United

States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542, 552, 23 L. Ed. 588:

“ ‘The very idea of a government, republican in

form, implies a right on the part of its citizens to meet

peaceably for consultation in respect to public affairs

and to petition for a redress of grievances.’

“ The First Amendment of the Federal Constitu

tion expressly guarantees that right against abridge

ment by Congress. But explicit mention there does not

argue exclusion elsewhere. For the right is one that

cannot be denied without violating those fundamental

principles of liberty and justice which lie at the base

of all civil and political institutions—principles which

the Fourteenth Amendment embodies in the general

terms of its due process clause. # #

Baskin et ah, Appellants, v. Bkown, Appellee 25

“ The greater the importance of safeguarding the

community from incitements to the overthrow of our

institutions by force and violence, the more imperative

is the need to preserve inviolate the constitutional

rights of free speech, free press and free assembly in

order to maintain the opportunity for free political

discussion, to the end that government may be respon

sive to the will of the people and that changes, if de

sired, may be obtained by peaceful means. Therein lies

the security of the Republic, the very foundation of

constitutional government. ’ ’

In People ex rel Lindstrand v. Emmerson, 333 111. 606,

165 N. E. 217, 62 A. L. R. 912, the Court said:

“ Political parties had birth in this country as a

result of differences of opinion arising in the second

session of the first Congress of the United States, in

1790, over Alexander Hamilton’s plan to fund the in

debtedness of the various states incurred before and

during the Revolution. They have always represented

a divergence in thought in governmental policy. Their

influence and importance have grown, until they are

today a necessary adjunct to representative govern

ment, yet there is no constitutional or statutory re

quirement that there be political parties, but it has

always been recognized that they are voluntary or

ganizations, possessing inherent powers of self-govern

ment. ’ ’

It has been said that

“ A political party is an association of voters be

lieving in certain principles of government, formed to

urge the adoption and execution of such principles in

governmental affairs through officers of like beliefs.”

Kelso v. Cook, 184 Ind. 173, 110 N. E. 987, 994,

Ann. Cas. 1918 E. 68.

In Ingersoll v. Heffernan, (1947) 71 N. Y. S. 2d 687,

188 Misc. 1047, affirmed 297 N. Y. 524, 74 N. E. 2d 466, the

Court said:

26 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

“ A political party is something more than a me

dium for nomination or election to public office. The

formulation of party principles and policies is a duty

which, if political parties are to continue to serve their

historical functions in the scheme of the democratic

process, transcends the mere purpose to elect particu

lar candidates to public office.”

In Ingersoll v. Curran (1947), 70 N. Y. S. 2d 435, 188

Misc. 1003, affirmed 297 N. Y. 522, 74 N. E. 2d 465, the

court said:

“ Political parties are voluntary organizations of

people who believe generally in the principles enunci

ated and the candidates offered to the people by the

particular party of their choice. It is true that over

the years the Legislature has enacted many laws regu

lating the conduct of political parties in order to cor

rect abuses which had arisen. The voluntary nature of

political parties nevertheless continues to be recog

nized.”

In Socialist Party v. Uhl, 155 Cal. 776, 103 Pac. 181,

the Court said:

“ A political party is an organization of electors

believing in certain principles concerning govern

mental affairs, and urging the adoption and execution

of those principles through the election of their re

spective candidates at the polls. The existence of such

parties, the dominant party and the parties in opposi

tion to it, lies at the foundation of our government,

and it is not expressing it too strongly to say that

such parties are essential to its very existence. The

design of the primary law is not to destroy political

parties, but, while carefully preserving their integrity,

to work out reforms in their methods of administration.

Such being the purpose of the law, it is not only proper

to prescribe such a test, but the absence of such a test

would tend to work the absolute disintegration and

destruction of all parties, except for the saving power

Baskin et al., Appellants, v . Brown, Appellee 27

within the party itself of prescribing its own tests and

regulations.”

(The test referred to was the requirement of Statute

that an elector is not entitled to vote in a primary unless

he states, at the time of registration the name of the poli

tical party with which he intends to affiliate, and that he is

not permitted to vote on behalf of any party other than the

party designated in his registration.)

In Smith v. Howard, 275 Ky. 165, 120 S. W. 2d 1040,

the Court quoted with approval the following from Davis

v. Hambrick, 109 Ivy. 276, 58 S. W. 779, 22 Ky. Law Kep.

815, 51 L. B„ A. 671:

“ Political parties are voluntary associations for

political purposes. They are governed by their own

usages, and establish their own rules. Members of such

parties may form them, reorganize them, and dissolve

them at their will. The voters constituting such party

are, indeed, the only body who can finally determine be

tween contending factions or contending organizations.

The question is one essentially political, and not ju

dicial, in its character. It would be alike dangerous to

the freedom and liberty of the voters, and to the dig

nity and respect which should be entertained for ju

dicial tribunals, for the courts to undertake in any case

to investigate either the government, usages, rules, or

doctrines of a political party, or to determine between

conflicting claimants’ rights growing out of its gov

ernment. ’ ’

The right of the membership of a political party to

protect its party integrity against intrusion of those who

are not in sympathy with its principles and the purpose of

fostering and effectuating them is not affected by the fact

that political parties and their party activities, including

party primaries, are regulated by state statutes; indeed,

the right is safeguarded in many such statutes.

28 Baskin et ah, Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

Ingersoll v. Heffernan, (1947) 71 N.Y.S. 2d 687,

188 Misc. 1047, affirmed 297 N.Y. 524, 74 N.E.

2d 466.

Ingersoll v. Curran, (1947) 70 N.Y.S. 2d 435, 188

Misc. 1003, affirmed 297 N.Y. 522, 74 N. E. 2d

465.

Zuckman v. Donahue, (1948) 79 N.Y.S. 2d 169, 191

Misc. 399, order modified 274 App. Div. 216, 80

N.Y.S. 2d 698.

Werbel v. Gernstem, (1948) 78 N.Y.S. 2d 440, 191

Misc. 275, affirmed 273 App. Div. 917, 78 N.Y.S.

2d 926.

In Be: Newkirk (1931), 259 N. Y. S. 434, 144 Misc.

765;

Socialist Parly v. Uhl, 155 Cal. 776, 103 Pac. 181;

People ex rel Lindstrand v. Emmerson, 333 111, 606,

165 N. E. 217, 62 A. L. E. 912.

It was held that the enrollment in the Democratic Party

of persons adhering to the principles of the American Labor

Party was validly cancelled by the party’s county chairman

under the provisions of the New York Election Law

(Werbel v. Gernstem, supra)] that the enrollment in the

American Labor Party of persons adhering to the prin

ciples of the Democratic Party was validly cancelled in a

similar proceeding (Zuckman v. Donahue, Supra); and that

the enrollment of persons not in sympathy with the princi

ples of the Socialist Party was likewise validly cancelled,

despite their declaration that they were in sympathy there

with (In Re: Newkirk, Supra).

In the instant case, the State Convention of the Demo

cratic Party of South Carolina adopted a platform and de

clared the principles of the party. They limited member

ship and enrollment to those who subscribe to the principles

of the party, as declared by the state convention, and vot-

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 29

ing to those who subscribe to the voter’s oath. These re

quirements were applicable without

Respect to race or color, upon the elimination of the

provision as to White Democrats.

The District Judge, however, in the order of July 19,

1948, enjoined the administration of the oath to any voters,

whether white or Negro, and the only concession to the

principle of party intergrity was the provision in his order

that an oath containing a provision that he or she is a

Democrat and will support the election of the nominees of

the Democratic Party (sic) at the ensuing general election

might be administered to prospective voters.

On July 22, 1948, however, the District Judge, of his

own motion, modified the order of July 19, 1948, by elimi

nating the provision that the voters oath might contain a

statement that the prospective voter is a Democrat, and

permitted only a statement that “ he pledge himself to sup

port the nominees of that primary.”

The provisions of the oath, proposed to be adminis

tered by the appellants, which were held invalid were:

‘ ‘ I further swear that I believe in and will support

the principles of the Democratic Party of South Caro

lina, and that I believe in and will support the social

and educational separation of races.

“ I further solemnly swear that I believe in the

principles of States’ Rights, and that I am opposed to

the proposed Federal so-called F. E. P. C. Law.”

The provision in the oath “ that I am not a member of

any other political party” was also embraced within the

interdiction of his orders.

The first provision which the District Judge regarded

as violating the sections of the Constitution and statutes of

30 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

the United States relied on by the appellee was the pro

vision relating to the separation of races.

The Constitution of South Carolina, 1895, Article XI,

section 7, reads:

“ Separate schools shall be provided for children

of the white and colored races, and no child of either

race shall ever be permitted to attend a school provided

for children of the other race.”

This section is constitutional under the decisions of

the Supreme Court of the United States.

State of Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S.

337, 59 S. Ct. 232, 83 L. Ed. 208, and cases cited therein.

Social separation is also provided for by constitutional

and statutory provisions.

Article III, Section 33, of the Constitution reads in

p a rt:

“ The marriage of a white person with a negro or

mulatto, or person who shall have one-eighth or more

of negro blood, shall be unlawful. * # * ”

Section 1272 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina,

1942, provides in part:

“ It shall be unlawful for any person, firm or cor

poration engaged in the business of cotton textiles

manufacturing in this State to allow or permit opera

tives, help and labor of different races to labor and

work together within the same room, or to use the same

doors of entrance and exit at the same time, or to use

and occupy the same pay ticket window’s or doors for

paying off its operatives at the same time, or to use

the same stairway and windows at the same time, or

to use at any time the same lavatories, toilets, drink

ing water buckets, pails, cups, dippers or glasses: pro

vided, equal facilities shall be supplied and furnished

to all persons employed by said persons, firms or cor

porations engaged in the business of cotton textile

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 31

manufacturing as aforesaid, without distinction as to

race, color or previous conditions. # * * ”

Section 1269 of the Code provides in part:

“ Electric railways outside of the corporate limits

of cities and towns shall have authority to separate the

races in their cars, and the conductors in charge of

said cars are hereby authorized and directed to sep

arate the races in said cars under their charge and

control. * * # ”

Section 8530-1 of the Code provides in part:

“ All passenger motor vehicle carriers, operating

in the State of South Carolina shall separate the white

and colored passengers in their motor buses. # * * ”

Section 8396 of the Code provides in part:

“ All railroad and steam ferries and railroad com

panies engaged as common carriers of passengers for

hire, shall furnish separate coaches or cabins for the

accommodation of white and colored passengers: pro

vided, equal accommodations shall be supplied to all

persons without distinction of race, color or previous

condition, in such coaches or cabins. * * * ”

Section 8490 of the Code provides in part:

“ All street railway companies now operating or

hereafter to operate lines of street railways in the

State of South Carolina are hereby required to provide

separate accommodations for the white and colored

passengers on their cars. * * # ”

Section 8403 of the Code provides in part:

“ No persons, firms or corporations, who or which

furnish meals to passengers at station restaurants or

station eating houses, in times limited by common

carriers of said passengers, shall furnish said meals

to white and colored passengers in the same room, or

at the same table, or at the same counter. * * * ”

32 Baskin et al., Appellants, v . Brown, Appellee

Section 1271 of the Code provides in part:

“ Any circus or other such traveling show exhibit

ing under canvas or out of doors for gain shall main

tain two main entrances to such exhibition, and one

shall be for white people and the other entrance shall

be for colored people. * * * ”

These provisions are also constitutional.

State of Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, supra, and

cases cited therein.

Social and educational separation of the races is dealt

with and commanded by the Constitution and laws of the

State, and the membership of a political party has the right

to associate themselves together to support such provisions,

to adopt their support as a political objective of their party,

and to condition enrollment in their party and voting in

their party’s primaries upon belief in and support of the

same.

The next provision of the oath which the District Judge

regarded as violating the sections of the Constitution and

statutes of the United States relied on by the appellee was

the provision relating to belief in the principles of States ’

Rights and opposition to the proposed Federal so-called

F. E. P. C. law.

There is nothing unlawful in the membership of a polit

ical party associating themselves together as a political

party to advocate and support the principles of States’

Rights as a political objective of their party, and to oppose

the enactment of Federal so-called F. E. P. C. legislation

(such as S. 984, 80th Congress, 1st Session, introduced by

Senator Ives under the title “ A Bill to Prohibit Discrimi

nation in Employment Because of Race, Religion, Color,

National Origin, or Ancestry” ) which they believe to be

an encroachment upon the reserved powers of the States

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 33

under the Tenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States.

The principle of States’ Rights was a firm belief of

Thomas Jefferson, who, in his first Inaugural Address, gave

the Democratic Party its traditional creed :

“ * * * the support of the State governments in all

their rights, as the most competent administrations

for our domestic concerns and the surest bulwarks

against anti-republican tendencies. * * * ”

Jefferson warned that

“ * * * the States should be watchful to note every

material usurpation on their rights; to denounce them

as they occur in the most peremptory terms; to protest

against them as wrongs. # * * ”

Letter to W. B. Giles, 1825, The Wisdom of Thomas

Jefferson, Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., N. Y., 1941.

Alexander Hamilton, in a speech urging the adoption

of the Constitution before the Constitutional Convention at

Hew York, June 24, 1788, said:

“ The state governments are essentially necessary

to the form and spirit of the general system. As long,

therefore, as Congress has a full conviction of this

necessity, they must, even upon principles purely na

tional, have as firm an attachment to the one as to the

other. This conviction can never leave them, unless

they become madmen. ’ ’

And further:

“ The states can never lose their powers till the

whole people of America are robbed of their liberties.

These must go together; they must support each other,

or meet one common fate.”

The address of Retired Associate Justice Owen J.

Roberts as President of the Pennsylvania Bar Association,

June 26,1948, quoted in the August 1948 issue of the Ameri

can Bar Association Journal, contained these statements:

34 Baskin et a l, Appellants, v . Brown, Appellee

“ Does not centralization portend a revolution in

the form and function of the national government?

* * * A failure on the part of either the legislative or

the judicial branch of government to observe the spirit

of the compact may well spell the end of our form of

government. * * # We should at least discover whether

our people prefer something more nearly approaching

alien systems, wherein the States are mere administra

tive districts of a central government.”

Can it be said that the membership of a political party

may not adopt, as a party principle, belief in States ’ Rights

and opposition to Federal so-called F. E. P. C. legislation

which many people in every part of the country believe to

be a violation of States’ Rights? Having adopted it, may

they not work for it as a political objective, and condition

enrollment in their party and voting in their party’s pri

maries upon sympathy with such party principle and the

purpose of fostering and effectuating it?

Neither of the political objectives ruled invalid by the

District Judge are unlawful. Both are legitimate political

aims, under both the Federal and State Constitutions.

The District Judge took “ judicial cognizance” of the

fact that Negroes generally do not believe in such political

objectives, and that they would not take a voter’s oath at

testing adherence to them, and of course would not sub

scribe to them as party principles. Lawful political objec

tives are thus held to become invalid because they are not

believed in by a class of prospective members and voters.

If the District Judge can take judicial cognizance of

the fact that Negroes do not believe in the lawful political

principles and objectives of the Democratic Party of South

Carolina, may not the party itself take such notice of that

as a fact, in adopting the limitation of membership in Rule

6 to white Democrats ? It would seem that the judicial cog-

)

Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee 35

nizance so taken by the District Judge should compel him

to the conclusion that it was not invalid for the party con

vention to exclude Negroes from membership and voting

on the ground that they are not in sympathy with, but are

opposed to, the political principles and objectives of the

party, and are not entitled to invade it for the purpose of

thwarting and destroying its principles and objectives.

If the District Judge is correct in finding that Negroes

generally do not subscribe to the party’s lawful principles

and political aims, it is their political or personal beliefs

which exclude them from membership and participation in

the activities and primaries of the party. This does not call

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments into operation,

for the party requirement is applicable without discrimina

tion, and the only part which race or color plays is in caus

ing the political beliefs of the appellee and the others for

whom he sues, which beliefs are different from those of the

party he seeks to join.

The Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States provides:

“ The right of citizens of the United States to vote

shall not be denied or abridged by the United States

or by any State on account of sex. * * #

Would this amendment deny the right of women to

form a party having as its political objective the enactment

of constitutional and statutory provisions guaranteeing

equal rights for women, to prescribe belief in that objec

tive as a condition of membership and participation in their

party’s activities and primaries, and to exclude therefrom

any men (as well as any women) who do not believe in their

party’s political objective! We respectfully submit that it

would not, for if sex in such a case denies or abridges the

right of the men to vote, it is only because of its effect upon

36 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Bkown, Appellee

their political belief and not because sex is made a test of

membership and voting.

If the District Judge is right in the instant case, that

Negroes generally do not subscribe to the party’s lawful

principles and political aims and objectives, it is their polit

ical or personal belief which brings about abridgement of

their right to membership and to vote, for the test is not

race or color, and it is applied to all alike.

It is respectfully submitted that the portion of Rule 6

under consideration, and the voter’s oath, were not ren

dered invalid under the sections of the Constitution and

statutes of the United States on which the appellee relies,

and that the District Judge erred in his holding to the

contrary.

Ill

The Democratic Party of South Carolina, as a political

party, had the right to adopt in its State Convention po

litical governmental principles and objectives of the party

relating to the separation of the races, States’ Rights and

the Federal so-called F. E. P. C. law, and to exclude from

membership and from voting in its primaries appellee and

others similarly situated who did not believe in and were

not in sympathy with such lawful political and govern

mental objectives; and the District Judge erred in holding to

the contrary and rendering judgment in favor of appellee.

In our discussion of Question II, supra, we have en

deavored to show that the provisions of the party rules

limiting enrollment to those who subscribe to the party’s

principles, as declared by the State Convention, and limit

ing voting in its primaries to those who take the voter’s

oath are not invalid, and should have been left of force in

the August 10th primary and in the enrollment period

which preceded it.

Baskin ei al., Appellants, v . Brown, Appellee 37

Under those provisions the appellee and those for

whom he sires were not eligible to enroll as members of

the party or to vote in its primary, even after the elimina

tion of that portion of Rule 6 which limits membership to

white Democrats.

The stipulation of facts filed November 23,1948, shows

that the appellee does not believe in the principles of the

Democratic Party of South Carolina relating to the separa

tion of the races and the so-called federal F. E. P. C. law,

and that he believes that all States’ Rights are subject to

the paramount authority of the Constitution of the United

States.

He does not subscribe to the principles of the party,

as declared in the State Convention, and he could not truth

fully take the voter’s oath.

As we have shown, it was his belief on the party’s

political principles and objectives which made him in

eligible to enroll and vote and not any limitation based

upon race or color. It was his privilege to hold beliefs con

trary to those of the party; it was his privilege to join or

organize a political party to foster and effectuate his be

liefs; it was his privilege not to join a party with whose

principles he disagreed; but it was not his privilege to in

vade that party for the purpose, not of assisting in the at

tainment of its lawful political objectives, but to seek to

thwart and destroy them.

It is respectfully submitted that, entirely apart from

the limitation of enrollment to white Democrats, the ap

pellee was not entitled to enroll in the Democratic Party

of South Carolina and to vote in its primary, and that the

District Judge erred in holding to the contrary, both in

his order dated July 19, 1948, and his order dated Novem

ber 26, 1948.

38 Baskin et al., Appellants, v. Brown, Appellee

Zucknum v. Donahue, (1948) 79 N. Y. S. (2d), 169,

191 Misc., 399, order modified 274 App. Div.,

216, 80 N. Y. S. (2d), 698;

Werhel v. Gernstein, (1948) 78 N. Y. S. (2d), 440,