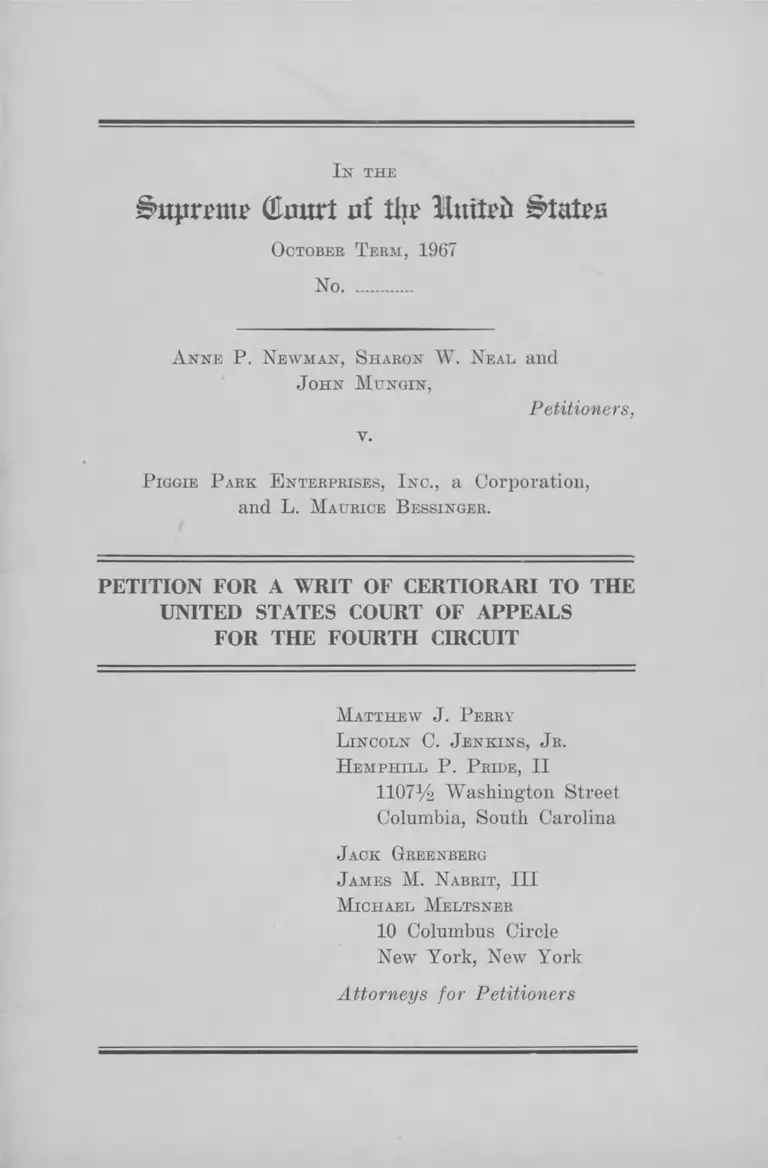

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1967. fbfa5789-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dca22bc4-9c8a-4f36-9cc5-7bf879b43ea2/newman-v-piggie-park-enterprises-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

i>upnmu> (Umtrt of tlii> lluittb States

October T erm, 1967

No..............

A nne P. New m an , S haron W. Neal and

John M ungin ,

Petitioners,

v.

P iggie P ark E nterprises, I nc., a Corporation,

and L. M aurice B essinger.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

M atthew J. Perry

L incoln C. Jenkins, J r .

H emphill P. Pride, II

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Citation to Opinions B elow .............................................. 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

Question Presented ........................................................... 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ........................................ 2

Statement ........................................................................... 2

Reasons for Granting the Writ ...................................... 6

Introduction ......................................................................... 6

The Court of Appeals incorrectly construed Title

II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to permit

recovery of counsel fees only upon a showing

of subjective bad faith .......................................... 8

Conclusion ........................................................................... 14

A ppendix—

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit .......................................... la

Opinion and Order of District Court ..................... 11a

T able of Cases

Bates v. Bonner Private Club, No. 1222 (S.D. Ga.) ..... 7

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321 F.2d

494 (4th Cir. 1963) .......................................................... 13

Braxton v. Jeanette, No. 505 (E.D. N.C.) ..................... 7

Epps v. Krystal Co., No. 66-648 (N.D. Ala.) ................... 7

PAGE

11

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) ..................... 10

Goode v. Acme Cafe, No. 4357-66 (S.D. Ala.) ............... 7

Goode v. Johnny’s Drive-in Restaurant, No. 4358-66

(S.D. Ala.) ....................................................................... 7

Goodwill v. Fletcher’s Bar-B-Que, No. 4362-66 (S.D.

Ala.) ................................................................................. 7

Goodwill v. Presto Restaurant, No. 4359-66 (S.D. Ala.) 7

Gregory v. Myer, appeal docketed, No. 32948 (U.S. Ct.

of App. 5th Cir.) ........................................................... 7

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964) ....... 10

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S.

241 (1964) ....................................................................... 10

Hughes v. Falgut, No. 66-741 (N.D. Ala.; injunction

entered April 13, 1967) .................................................. 7

Johnson v. Larry’s Restaurant, No. 4363-66 (S.D. Ala.) 7

Katzenbach v. McClung, 371 U.S. 291 (Dec. 14,1964) .... 12

Kyles v. Paul, appeal docketed, No. 18824 (U.S. Ct.

App. 8th Cir.) ................................................................. 7

Lawson v. Tito’s Restaurant, No. 4361-66 (S.D. Ala.) 7

LeFlore v. Butlers Chick-a-Teria, No. 4360-66 (S.D.

Ala.) ................................................................................. 7

LeShore v. Carter, No. 3614-65 (S.D. Ala.) .................. 7

Little v. Sedgefield Inn, No. C-180-G-65 (M.D. N.C.) .... 7

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., appeal dock

eted, No. 24,259 (U.S. Ct. App. 5th Cir.) .................. 7

Mitchell v. Krystal Co., No. 65-579 (S.D. Ala.) ......... 7

Nesmith v. Raleigh YMCA, No. 1768 (M.D. N.C.) .....

PAGE

7

Ill

Rax v. Piper, No. 11,307 (W.D. La.) ............................ 7

Rolax v. Atlantic Coastline Railroad Co., 186 F.2d 473

(4th Cir. 1951) ............................................................... 13

Stout v. YMCA of Bessemer, No. 66-715 (S.D. Ala.) 7

Wooten v. Moore, No. 631 (E.D. N.C.) ........................ 7

S tatutes

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ............................................................ 2

42 U.S.C. §2000a-(a) ......................................................... 10

42 U.S.C. §2000a-2 ............................................................. 10

42 U.S.C. §2000a-3(a) ....................................................... 10

42 U.S.C. §2000a-3(b) ................................ 2, 6, 8, 9,10,13,14

42 U.S.C. §2000a-(c) (2) .................................................... 3,12

42 U.S.C. §2000a-3(e) ..................................................... 12

42 U.S.C. §2000a-5 .............................................................. 10

Other A uthorities

110 Cong. Rec. 14201 (June 17, 1964) ......................11,12

110 Cong. Rec. 14213 (June 17, 1964) ........................ 11

110 Cong. Rec. 14214 (June 17, 1964) ......................11,12

New York Times (“Integration in South: Erratic

Pattern” ) May 29, 1967 ................................................ 7

PAGE

I n t h e

&ttpr£ttt£ (Emtrt of thr llnttefr Stairs

October T erm, 1967

No..............

A nne P. New m an , S haron W. Neal and

John M ungin ,

Petitioners,

v.

P iggie P ark E nterprises, I nc., a Corporation,

and L. M aurice B essinger.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to

review the judgment of the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit entered in the above-entitled

case on April 24, 1967.

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit is not yet reported, and is set forth

in the appendix hereto, infra p. la. The decision of the

United States district court for the district of South

Carolina is reported at 256 F. Supp. 941, and appears in

appendix infra p. 11a and in the record at pp. 206a

et seq.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit was entered on April 24, 1967.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether the Court of Appeals correctly construed Title

II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as denying recovery

of counsel fees by Negroes excluded from places of public

accommodation unless a showing is made that a restau

rateur’s patently frivolous defenses and obstructive tactics

were the product of dishonesty and bad faith.

Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves Title II of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000a et seq., and more particularly,

42 U.S.C. §2000a-3(b):

In any action commenced pursuant to this subchapter,

the court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing-

party, other than the United States, a reasonable

attorney’s fee as part of the costs . . . .

Statement

Negro plaintiffs instituted this class action December 18,

1964 against the corporate operator of a chain of six

restaurants and its president and principal stockholder,

seeking injunctive relief prohibiting exclusion of Negroes

and recovery of counsel fees pursuant to the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000a et seq. The complaint

alleged, in summary, that at various locations in South

3

Carolina the corporation operates restaurants which affect

commerce and where Negroes are refused service (R.

la-7a).

Defendants answered by denying Negroes were refused

service; that operation of the restaurants affected com

merce ; and that the restaurants were places of “public

accommodation” as that term is defined in the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.1 Defendants asserted that Title II is uncon

stitutional in violation of the Commerce Clause (Art. I,

§8); the Privileges and Immunities Clause (Art. IV, §2);

the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment; and the Thirteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. In addition, the

corporation president alleged that service of food to

Negroes, as required by Title II, violated his freedom

of religion as protected by the First Amendment (R. 8a-

10a; lla-13a; 17a-20a).

At a trial, April 4-5, 1966 (R. 21a-205a), the facts as

found by the district court were not materially disputed.

The corporation operates six eating places, five of which

are drive-ins located on major highways (R. 211a-212a).

The sixth, Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop, is in downtown

Columbia, South Carolina with tables and chairs for

approximately sixty customers (R. 212a). The district

court found “ at least” forty percent of the food purchased

by the restaurants each year moved in commerce (R. 221a)

and that the restaurants served many interstate travelers

(R. 215a-216a). It concluded that the operation of the

six restaurants affected commerce within the meaning of

Title II, 42 U.S.C. §2000a-(c) (2).

1 Defendants filed an answer February 5, 1965, an amended answer

August 23, 1965 and were permitted by the district court to file a second

amended answer March 19, 1966. A ll generally denied the allegations of

the complaint.

4

Despite denials of Negro exclusion in the pleadings,

the president of the corporation, a corporation book

keeper, and a waitress testified that Negroes were served

only on a kitchen door take-out basis (R. 160a, 169a, 172a,

189a). The district court found also that two plaintiffs

had been denied service at one of the restaurants because

of race (R. 214a-214a).

Although the district court found discrimination, and

that operation of the six restaurants affected commerce,

it excluded the five drive-ins from coverage on the ground

that Congress had not intended Title II to apply to drive-

ins. It entered an order enjoining racial discrimination

at the Sandwich Shop only, awarded Negro plaintiffs their

costs, but refused to award counsel fees, infra p. 34a (R.

229a).

Plaintiffs appealed to the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Fourth Circuit; the United States filed a

brief Amicus Curiae supporting plaintiffs’ position that

the drive-in restaurants were covered by the Act. The

Court of Appeals, sitting en banc, agreed holding that

the district court should have enjoined racial discrimina

tion at all restaurants operated by the defendants.

The Court of Appeals further instructed the district

court “ to consider the allowance of counsel fees, whether

in whole or in part,” and set forth the “ subjective” test

which district courts should apply to determine whether

to permit recovery of counsel fees, infra p. 7a:

In exercising its discretion, the district court may

properly consider whether any of the numerous de

fenses interposed by defendants were presented for

purposes of delay and not in good faith. But the test

should be a subjective one, for no litigant ought to

be punished under the guise of an award of counsel

fees (or in any other manner) from taking a position

5

Judge Winter, with whom Judge Sobeloff joined, dis

agreed with the majority conclusion that “good faith,

standing alone,” should “ immunize a defendant from an

award against him.” Judge Winter examined the rela

tionship of the provision for recovery of counsel fees to

enforcement of Title II, and concluded that a “ subjective”

test would frustrate compliance, infra p. 9a:

In providing for counsel fees, the manifest pur

poses of the Act are to discourage violations, to en

courage complaints by those subjected to discrimina

tion and to provide a speedy and efficient remedy for

those discriminated against. I f counsel fees are with

held or grudgingly granted, violators feel no sanctions,

victims are frustrated and instances of unquestionably

illegal discrimination may well go without effective

remedy. To immunize defendants from an award of

counsel fees, honest beliefs should bear some reason

able relation to reality; never should frivolity go

unrecognized.

Petitioners are represented by retained private counsel

of Columbia, South Carolina, who have been assisted by

salaried attorneys of a nonprofit civil rights organization.

The award of counsel fees is sought only by the retained

South Carolina counsel for their services, and not for

others.

in court in which he honestly believes—however lack

ing in merit that position may be.

6

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Introduction

This is a case of first impression in this Court. The

Court of Appeals has construed the counsel fees provi

sion of the public accommodation Title of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 to authorize an award only when under a

“ subjective” test, a litigant takes a position “not in good

faith.” Unless a district court finds such a state of mind,

a prevailing party is not entitled to recover counsel fees

“however lacking in merit” the position taken or tactics

employed by a discriminator.

We believe that such a construction of $2000a-3(b)

seriously impairs the acknowledged congressional purpose

“to assure rapid and effective compliance” with Title II,

infra p. 7a; that limitation of an award to cases where

bad faith is shown injects an element of culpability into

the counsel fee provision unrelated to the purposes of

Title I I ; and that the Court of Appeals, by limiting awards

to occasions when a court of the United States would

have been authorized to award a fee without statutory

authority, has seriously misread the intent of Congress.

The counsel fee provision of Title II is an important

means of promoting widespread compliance with the Act

by placing restaurateurs on notice that frivolous refusal

to comply promptly may lead to judicial proceedings in

which the burden of expenses may be on the restaurant,

not the wronged plaintiff, if the defendant resists on

frivolous grounds or is dilatory in his defense. If restau

rateurs are permitted to avoid an award of counsel fees

on the basis that they honestly believe in a position, how-

7

We call the Court’s attention to the fact that discrimina

tion in public accommodations remains a serious problem

once a Negro leaves well-travelled interstate highways.2

As a recent survey by the New York Times (“ Integration

in South: Erratic Pattern” ) put it:

It is possible to motor through the green valleys

of Virginia, veer through the cotton fields in Alabama

and Mississippi, and end up in Texas cattle country

with the conviction that racial segregation and dis

crimination are gone at last.

You could get that impression if you dined at chain

restaurants like Howard Johnson’s, slept in chain

motels such as the Holiday Inns, . . . .

A different itinerary might leave you convinced

that the South has not changed at all. Asking for a

night’s lodging in an obscure motel can be risky for

2 W hile appellants have been unable to ascertain the precise number of

Title I I actions involving restaurants presently pending before the federal

courts, the number of cases known to petitioners suggests that the total

is large. See, Little v. Sedgefield Inn, No. C-180-G -65 (M .D . N .C .) ;

LeShore v. Carter, No. 3614-65 (S .D . A la .) ; LeFlore v. Butlers Chick-a-

Teria, No. 4360-66 (S .D . A la .) ; Lawson v. Tito’s Restaurant, No. 4361-66

(S .D . A la .) ; Johnson v. Larry’s Restaurant, No. 4363-66 (S .D . A la .) ;

Hughes v. Falgut, No. 66-741 (N .D . A la .; injunction entered April 13,

1 9 6 7 ); Gregory v. Myer, appeal docketed, No. 32948 (U .S . Ct. of A p p .

5th C ir .) ; Goodwill v. Presto Restaurant, No. 4359-66 (S .D . A la .) ; Good

will v. Fletcher’s Bar-B-Q.ue, No. 4362-66 (S .D . A l a .) ; Goode v. Johnny’s

Drive-in Restaurant, No. 4358-66 (S .D . A la .) ; Goode v. Acme Cafe, No.

4357-66 (S .D . A la .) ; Epps v. Krystal Co., No. 66-648 (N .D . A la .) ;

Braxton v. Jeanette, No. 505 (E .D . N .C .) ; Bates v. Bonner Private Club,

No. 1222 (S .D . G a .) ; Mitchell v. Krystal Co., No. 65-579 (S .D . A la .) ;

Nesmith v. Raleigh YM CA, No. 1768 (M .D . N .C .) ; Wooten v. Moore,

No. 631 (E .D . N .C .) ; Stout v. YMCA of Bessemer, No. 66-715 (S .D . A l a .) ;

Rax v. Piper, No. 11,307 (W .D . L a .) ; Miller v. Amusement Enterprises,

Inc., appeal docketed, No. 24,259 (U .S . Ct. A p p . 5th C ir .) ; Kyles v. Paul,

appeal docketed, No. 18824 (U .S . Ct. A p p . 8th Cir.)

ever lacking in merit that position may be, the incentive

to comply promptly will be significantly reduced.

8

a Negro who wants to avoid embarrassment. And in

countless small towns, independent restaurants cater

mainly to an all-white clientele, and Negroes still

watch movies from segregated balconies.

(N. Y. Times, May 29, 1967, P. 1, Col. 1)

In enacting Title II Congress labored long to fashion a

scheme which would assure prompt compliance by nearly

all eating facilities because it is scant consolation to the

Negro interstate traveler that many restaurants are deseg

regated if the one he enters continues to discriminate.

Commerce is burdened by the very uncertainty that all

eating facilities are not desegregated. As it limits appli

cation of the counsel fee provision to the unusual case

where the elusive concept of manifest insincerity is demon

strated, the construction given §2000a-3(b) by a majority

of the court of appeals only serves to stiffen resistance

to the elimination of discrimination in public accommoda

tions.

The Court of Appeals incorrectly construed Title II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to permit recovery

of counsel fees only upon a showing of subjective

bad faith

In actions brought to desegregate public accommoda

tions, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provides that a prevail

ing party may recover reasonable attorney’s fee (42 U.S.C.

§2000a-3(b)) :

In any action commenced pursuant to this subchapter,

the court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing

party, other than the United States, a reasonable

attorney’s fee as part of the costs . . . .

9

“In exercising its discretion, the district court may

properly consider whether any of the numerous de

fenses interposed by defendants were presented for

purposes of delay and not in good faith. But the test

should be a subjective one, for no litigant ought to

be punished under the guise of an award of counsel

fees (or in any other manner) from taking a position

in court in which he honestly believes—however lack

ing in merit that position may be.”

The court below, therefore, has construed §2000a-3(b)

to make the vagrant notion of good faith a complete de

fense to recovery of counsel fees regardless of how patently

frivolous or how obstructive the tactics employed. Such

a construction is a variance with the congressional purpose

in enacting §2000a-3. As Judges Winter and Sobeloff

put it, infra p. 9a:

In providing for counsel fees the manifest purposes

of the Act are to discourage violations, to encourage

complaints by those subjected to discrimination and

to provide a speedy and efficient remedy for those

discriminated against. I f counsel fees are withheld

or grudgingly granted, violators feel no sanctions,

victims are frustrated and instances of unquestionably

illegal discrimination may well go without effective

remedy. To immunize defendants from an award of

counsel fees, honest beliefs should bear some reason

able relation to reality; never should frivolity go

unrecognized.

The soundness of Judge Winter’s construction of the

section is demonstrated by the legislative history of Title II

The court of appeals, sitting en banc, directed the dis

trict court to exercise its discretion to award counsel fees

only if it found subjective bad faith, infra p. 7a:

10

as a whole and §2000a-3(b) in particular. Title II demon

strates a plain desire to deter any substantial or prolonged

litigation which is inconsistent with the narrow construc

tion below of §2000a-3(b). For example, 42 U.S.C.

§2000a-3(a) permits intervention by the Attorney General

in privately initiated public accommodation suits, appoint

ment of counsel for a person aggrieved, and “ the com

mencement of the civil action without the payment of fees,

costs or security.” 42 U.S.C. §2000a-5 authorizes the At

torney General to commence litigation where there is “ a

pattern or practice of resistance to the full enjoyment”

of Title II rights. 42 U.S.C. §2000a-2 broadly prohibits

any attempt to punish, deprive, or interfere with rights

to equal public accommodations. See Georgia v. Rachel,

384 U.S. 780 (1966); Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S.

306 (1964). “The Act as finally adopted was most com

prehensive, undertaking to prevent through peaceful and

voluntary settlement discrimination in . . . public facilities”

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S. 241, 246

(1964). The counsel fee provision of 42 U.S.C. §2000a-3(b)

is part of the congressional plan for deterring evasion

and resistance to the “ full and equal enjoyment of the

goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages and ac

commodations of any place of public accommodation,”

42 U.S.C. §2000a-(a). Although the court below found that

in enacting Title II “ Congress intended to assure rapid

and effective compliance with its terms,” infra p. 7a, it

construed §2000a-3(b) in a manner which makes “ rapid

and effective compliance” more, not less, difficult.

The legislative record is scanty, but such debate as re

lates to §2000a-3 evidences intent to induce compliance

by penalizing the assertion of frivolous claims. On the

other hand, there is no support in the legislative history

for the notion that frivolity must be combined with a

11

subjective mental state evincing bad motives. In fact,

when Senator Ervin sought to eliminate the provision

from the Act on the ground that it would make those

benefiting from it special favorites of the law and would

encourage “ambulance chasing” his amendment was

rejected, 110 Cong. Rec. 14201, 14213-14 (June 17, 1964).

Senator Pastore made a brief statement in defense of

the provision stating that its purpose was deterrence of

frivolous suits and “ . . . the court within its discretion

is given power to order payment of attorneys’ fees to the

prevailing party. . . . It is not favoritism towards one

party as against the other,” 110 Cong. Rec. 14214 (June 17,

1964).3 Senator Miller emphasized the deterrence of

frivolous litigation. He saw no need to delete the section

because attorneys would be compensated only if they

raised positions with merit:

. . . I believe that this is the answer to the Senator

from North Carolina, that if we are concerned about

ambulance chasing, we had better realize that the

ambulance chasers are not about to be in the busi

ness if there is no profit in it for them. They will be

in the business only if they can make a profit. They

3 Senator Pastore stated:

The purpose of this provision in the modified substitute is to dis

courage frivolous suits. Here, the court within its discretion is given

power to order payment of attorneys’ fees to the prevailing party.

First of all, it is within the discretion of the eourt. It is not favor

itism towards one party as against the other. W hen a person realizes

that he takes the chance of having attorneys’ fees assessed against him

if he does not prevail, he will deliberate before he brings suit. H e

will make certain that he is not on frivolous ground. (110 Cong.

Rec. 14214, June 17, 1964).

Senator Pastore’s emphasis on frivolous suits is clearly explained by the

character of the challenges raised to the section by Senator Ervin. The

only construction o f Senator Pastore’s remarks consistent with their

context and the language employed in the statute is that the provision

was meant to penalize the assertion o f frivolous claims by either party.

12

are not going to make such profit out of any cases

except those which are meritorious, so I believe that

the point is exaggerated, and I believe the amendment

is inadvisable (110 Cong. Rec. 14214, June 17, 1964).

Thus, the Senators concerned spoke of the counsel fee

provision as if its application turned on merit or lack

of it, not good or bad faith.4 But, as the record here

demonstrates, to limit recovery of counsel fees to occa

sions of subjectively determined bad faith makes the

application of §2000a-3(b) turn on a principle which has

only fortuitous relation to the deterrence of extended

noncompliance and frivolous litigation. The facts of this

case show tactics and frivolous defenses which unjustifiably

delayed compliance and complicated petitioners burden of

proof, but, unless one chooses to infer bad faith, they

do not demonstrate any state of mind.

The defendant corporation in this case pursued various

claims that 42 U.S.C. §2000a-(c) (2) was unconstitutional

years after that question had been definitively resolved

by this Court in Katsenbach v. McClung, 371 U.S. 291

(December 14, 1964). Indeed, it filed a second amended

answer raising such defenses March 30, 1966 after “care

fully reviewing the pleadings heretofore filed” (R. 16a).

Defendants also denied their activities affected commerce

forcing petitioners to offer lengthy proof. But after trial,

the district court, which erroneously excluded the drive-in

facilities on another ground, had no trouble determining

that all six facilities were clearly covered by the Act both

4 A construction o f §2000a-3(b) which makes an award o f fees turn

on objective factors is not inconsistent with the discretion it lodges in the

district courts. That discretion is appropriately exercised to determine the

application of objective standards and the amount of counsel fees which

should be awarded, not to determine whether or not petitioners shall re

ceive any counsel fees solely because a restaurateur may honestly believe

that frivolous or dilatory tactics are justifiable.

13

because a substantial portion of the corporation’s food

moved in commerce and because it served or offered to

serve interstate travelers. Either circumstance satisfies

the “ affect commerce” standard of the Act. Likewise,

“ The fact that the defendants had discriminated both at

Piggie Park’s drive-ins and at Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop

was of course known to them, yet they denied the fact

and made it necessary for the plaintiffs to offer proof,

and the defendants could not and did not undertake at

the trial to support their denials,” infra p. 10a. Finally,

defendants contended the Act was invalid because it “ con

travenes the will of God” and constitutes an interference

with the “ free exercise of the Defendant’s religion,” infra

p. 10a.

These defendants have done, therefore, just what Con

gress sought to deter. “ The district judge should be told

that in awarding counsel fees, he should include an amount

which fully compensates plaintiffs for the time, effort

and expenses of counsel in overcoming these elements

of expense needlessly imposed on them” without a showing

of bad faith, infra p. 10a.

Federal equity courts have inherent power to grant

counsel fees in a narrow class of cases where manifest

insincerity and bad faith have been shown. Rolax v. At

lantic Coastline Railroad Co., 186 F.2d 473 (4th Cir.

1951); Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321

F.2d 494, 500 (4tli Cir. 1963). In §2000a-3(b), however,

Congress plainly intended something more than statutory

codification of an already existing equitable authority for

Congress authorized payment of a reasonable fee to the

prevailing party in the face of objections that such a

provision was unusual and did so in the context of a

comprehensive and delicate scheme for achieving prompt

14

change in the discriminatory practices of numerous

restaurateurs. This Court should not conclude, as did the

Court of Appeals, that Congress meant to add nothing to

the power of the federal courts by passage of §2000a-3(b).

CONCLUSION

W herefore, petitioners pray that the petition for writ

of certiorari be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

M atthew J. Perry

L incoln C. Jenkins, Jr.

H emphill P. Pride, II

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

A P P E N D I X

A P P E N D I X

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

No. 10,860.

Anne P. Newman, Sharon W. Neal

and John Mungin,

Appellants,

versus

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., a Corporation

and L. Maurice Bessinger,

Appellees.

A ppeal prom the U nited States D istrict Court for

the D istrict of S outh Carolina, at Columbia. Charles

E. Simons, Jr., D istrict Judge.

(Argued February 6, 1967. Decided April 24, 1967.)

Before H aynsworth, Chief Judge, and S obeloff, B ore-

man , B ryan, B ell, W inter and Craven, Circuit Judges.

2a

Craven, Circuit Judge:

This is a class action brought to obtain injunctive relief

and the award of counsel fees under Title II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.A. §§2000a to a-6. Plaintiffs

appeal from the decision of the district court holding that

Negro citizens may be barred on account of their race and

color from buying and eating barbecue at certain drive-in

restaurants in South Carolina. We disagree and reverse.*

The facts as found by the district court are not in dispute.

Briefly stated,* 1 Piggy Park Enterprises, Inc. (L. Maurice

Bessinger is the principal stockholder and general man

ager) owns and operates five eating establishments spe

cializing in southern style barbecue, all of which are lo

cated on or near interstate highways.2

All of Piggy Park’s eating places are of the drive-in type.

In order to be served, a customer drives upon the premises

in his automobile and places his order through an intercom.

When he pushes a button, his order is taken by an employee

inside the building who is usually out of sight of the cus

tomer. A curb attendant delivers the food or beverage to

the customer’s car and collects for the same. Orders are

served in disposable paper plates and cups. The food is

served in such a way that it is ready for consumption. Half

the customers eat in their automobiles while parked on the

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

* Judge J. Spencer Bell voted in conference with the other members of

the court to reverse. H is untimely death on March 19, 1967, prevented his

participation in the preparation of this opinion.

1 For a detailed statement see Newman v. Piggy Park Enterprises, Inc.,

256 F . Supp. 941 (D .S .C . 1966).

2 There was a sixth place, known as Little J oe’s Sandwich Shop, held by

the district court to be within 42 U .S .C .A . §2000a(b) (2 ). Injunctive relief

was granted and no appeal was taken.

3a

premises. There are no tables, chairs, counters, bars, or

stools at any of the drive-ins sufficient to accommodate any

appreciable number of patrons.

Although Piggy Park and Bessinger denied in their An

swer and two amended Answers that plaintiffs had been

denied service at one or more of Piggy Park’s drive-ins, it

was uncontested at the trial that Piggy Park denied full and

equal service to Negroes because of their race at all of its

eating places.3

The district court erroneously concluded that Piggy

Park’s drive-ins were not covered by the federal public ac

commodations law contained in the Civil Rights Act of

1964.4 The court reasoned that the statute would not apply

3 The few Negro customers who have been served took their places and

picked up their orders at the kitchen windows. They were not permitted

to consume their purchases on the premises.

4 The pertinent provisions of the Act a re :

“ 52000a. Prohibition against discrimination or segregation in places of

public accommodation— Equal access

“ (a) A ll persons shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of

the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, and accom

modations o f any place of public accommodation, as defined in this

section, without discrimination or segregation on the ground of race,

color, religion, or national origin.

“ (b) Each of the following establishments which serves the public is

a place o f public accommodation within the meaning of this sub

chapter if its operations affect commerce, or if discrimination or

segregation by it is supported by State action:

“ (2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch counter, soda

fountain, or other facility, principally engaged in selling food

for consumption on the premises, including, but not limited tq,

any such facility located on the premises of any real establish

ment; or any gasoline station;

“ (3 ) . . . ; and

“ ( 4 ) . . .

“ (c) The operations of an establishment affect commerce within the

meaning of this subchapter if (1 ) . . . (2 ) in the case of an establish-

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

4a

to a drive-in eating place unless a majority of the prepared

food sold was actually consumed by the customers on the

premises. It found from the testimony of Mr. Bessinger

that fifty percent of his food volume was consumed on the

premises and fifty percent off the premises, and from that

finding of fact concluded that the drive-ins were not facil

ities “principally engaged in selling food for consumption

on the premises.”

Such a construction, we think, finds no support in con

gressional history. The Congress did not intend coverage

of the Act to depend upon a head count of how many people

eat on the premises or a computation of poundage or vol

ume of food eaten. I f it had so intended, it would have

been a simple matter to change the questioned phrase “ for

consumption on the premises” to read “actually consumed

on the premises.”

During the House hearings,5 the Attorney General said

“ the areas of coverage should be clear to both the proprie

tors and the public.” If the “commerce” tests6 are the prin

cipal criteria, and we think they are, clarity of coverage is

promoted. A traveler can then intelligently assume that an

eating place on an interstate highway is covered. Under

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

ment described in paragraph (2) o f subsection (b) of this section,

it serves or offers to serve interstate travelers or a substantial por

tion of the food which it serves, or gasoline or other products which

it sells, has moved in commerce; . . 42 U .S .C .A . $2 00 0a (a )-(e ).

B Hearings on H.R. 7152 Before the House Committee on the Judiciary,

88th Cong., 1st Sess., pt. 4, at 2655 (1963).

6 There are two in the disjunctive:

“ (c) The operations of an establishment affect commerce . . . i f . . . it

serves or offers to serve interstate travelers or a substantial portion

of the food which it serves . . . has moved in commerce.” 42 U .S .C .A .

§2000a(c).

5a

the district court’s fifty percent test of actual consumption

on the premises, prospective Negro customers would have

no idea whether or not they might be served and would con

tinue to occupy the intolerable position—at least with re

spect to drive-ins—in which they found themselves prior to

passage of the Act with respect to interstate travel.7 In a

mobile society, the ready availability of prepared, ready-to-

eat food is a practical necessity—not a luxury.

In our view, the emphasis in the phrase “principally en

gaged in selling food for consumption on the premises” is

properly on the word “ food” . The term “ principally” did

not appear in the bill as introduced. It was added by the

House Judiciary Committee and retained in the same form

when the House version of the coverage provisions was

ultimately adopted in the Senate. Its inclusion was not in

tended to have any bearing upon the percentage of food

consumed on the premises, but was intended only to ex

clude from coverage places where food service was inci

dental to some other business, e.g., bars and “Mrs. Murphy”

tourist homes serving breakfast as a matter of convenience

to overnite lodgers. Given the intention of Congress to

eliminate bars,8 * * II the meaning of “principally” comes into

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

7 That the test is absurdly impractical is illustrated by Bessinger’s testi

mony that consumption on premises varied with the weather. On such a

hypohesis, a given drive-in might be covered one day, week, or month, and

not at other times.

8 See statement o f Senator Magnuson, Chairman o f the Senate Commit

tee on Commerce and principal floor spokesman in the Senate for Title I I ,

that “a bar in the strict sense of that word would not be covered by Title

I I since it is not ‘principally engaged in selling food for consumption on

the premises’ .” 110 Cong. Rec. 7406 (1964).

W e find no legislative history suggesting that “ principally” was inserted

to eliminate eating places doing a predominantly carry-out service.

6a

clear focus. Nothing in the 1964 Act as introduced or in

any revision made before its enactment except for the addi

tion of the word “principally” would exclude bars (and

other places such as howling alleys and pool rooms) serv

ing food as an incident to other business.

The words in the statute “ for consumption on the prem

ises” modify the prior word “ food” and describe the kind of

food sold by other facilities that are covered similar to res

taurants, cafeterias, lunchrooms, lunch counters, and soda

fountains. The Congress clearly meant to extend its power

beyond the ordinary sit-down restaurant and just as clearly

did not undertake to legislate with respect to grocery type

food stores which would have been covered hut for the

modifying phrase “ for consumption on the premises.”

Thus, food stores are not covered, hut stores (or facilities)

that sell food of a particular type, i.e., ready for consump

tion on the premises, are covered. What the customers ac

tually do with the ready-to-eat food was not the concern

of the Congress—whether they eat it then and there or

subsequently and elsewhere.

The sense of this plan of coverage is apparent. Retail

stores, food markets, and the like were excluded from the

Act for the policy reason that there was little, if any, dis

crimination in the operation of them. Negroes have long

been welcomed as customers in such stores. See 110 Cong.

Rec. 6533 (1964) (remarks of Senator Humphrey).

Discrimination with respect to ready-to-eat food service

facilities ivas a problem. When a substantial minority of

American citizens are denied restaurant facilities—whether

sit-down or drive-in—that are open to the public, unques

tionably interstate commerce is burdened. Katsenbach v.

McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964). It was this evil the Congress

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

7a

sought to eliminate to the end that all citizens might freely

and not inconveniently travel between the states. We think

the Congress plainly meant to include within the coverage

of the Act all restaurants, cafeterias, lunchrooms, lunch

counters, soda foutains, and all other facilities similarly en

gaged as a main part of their business in selling food ready

for consumption on the premises. We are further of the

opinion that the statutory language accomplished that pur

pose.

C o u n s e l F e e s

Title II as a whole demonstrates that the Congress in

tended to assure rapid and effective compliance with its

terms.9 42 U.S.C.A. Section 2000a-3(b) authorizes the court,

in its discretion, to allow the prevailing party (other than

the United States) a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of

the costs. By reason of our reversal of the district court,

the plaintiffs now become the “ prevailing party” , and on

remand we instruct the district court to consider the al

lowance of counsel fees, whether in whole or in part.

In exercising its discretion, the district court may prop

erly consider whether any of the numerous defenses in

terposed by defendants were presented for purposes of

delay and not in good faith. But the test should be a sub

jective one, for no litigant ought to be punished under the * 42

9 Thus, 42 U .S .C .A . §2000a-3(a) permits intervention by the Attorney

General in privately initiated public accommodation suits, appointment of

counsel for a person aggrieved, and “the commencement of the civil action

without the payment of fees, costs or security.” 42 U .S .C .A . §2000a-5

authorizes the Attorney General to commence litigation where there is “a

pattern or practice of resistance to the full enjoyment” of Title I I rights.

42 U .S .C .A . §2000a-2 broadly prohibits any attempt to punish, deprive,

or interfere with rights to equal public accommodations. See Georgia

v. Rachel, 384 U .S. 780 (1966).

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

8a

guise of an award of counsel fees (or in any other manner)

from taking a position in court in which he honestly be

lieves—however lacking in merit that position may be.

The court may also consider whether the defendants

acted in good faith in denying discrimination against

Negroes and thus requiring proof of what was subsequently

conceded to be true. A litigant who increases the burden

upon opposing counsel by such tactics ought ordinarily

bear the cost of unnecessary trial preparation. The so-

called “general denial” is not countenanced by the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure.

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

Reversed and Remanded for

Consideration of the Award

of Counsel Fees.

9a

W inter, Circuit Judge, with whom S obeloff, Circuit

Judge, joins, concurring specially:

Wholeheartedly I agree that Title II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.A. §2000a, et seq., is applicable to

Piggie Park’s drive-in type facilities, and I join in the rea

sons advanced for that conclusion. I agree also that the

case should be remanded for consideration of an award of

counsel fees, but I conclude that good faith, standing alone,

should not always immunize a defendant from an award

against him. Specifically, in this ease, defendants are not

entitled to the defense of good faith in regard to the major

portion of their defenses.

The district judge is told that in exercising his discretion

he should “ consider whether any of the numerous defenses

interposed by defendants were presented for purposes of

delay and not in good faith” because no defendant ought to

be punished for “ taking a position in court in which he

honestly believes— however lacking in merit that position

mag be.” (emphasis supplied) In this case, defendants inter

posed defenses patently frivolous, and I would not permit

them to avoid the costs of overcoming such defenses on a

purely subjective test of good faith.

In providing for counsel fees, the manifest purposes of

the Act are to discourage violations, to encourage com

plaints by those subjected to discrimination and to provide

a speedy and efficient remedy for those discriminated

against. I f counsel fees are withheld or grudgingly

granted, violators feel no sanctions, victims are frustrated

and instances of unquestionably illegal discrimination may

well go without effective remedy. To immunize defendants

from an award of counsel fees, honest beliefs should bear

some reasonable relation to reality; never should frivolity

go unrecognized.

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

10a

While the threat of an award of counsel fees ought not

be used to discourage non-frivolous defenses asserted in

good faith, the district court should be instructed to make

an allowance in regard to some of defendants’ defenses and,

in its discretion, to consider an allowance for the remainder

of defendants’ defenses depending upon its determination

of defendants’ good faith and honest belief. Those clearly

compensable are defendants’ assertion that their “Little

Joe’s Sandwich Shop,” a sit-down facility shown over

whelmingly by the proof to be a place where service was

refused to Negro citizens, was not subject to the Act. The

fact that the defendants had discriminated both at Piggie

Park’s drive-ins and at Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop was of

course known to them, yet they denied the fact and made

it necessary for the plaintiffs to offer proof, and the de

fendants could not and did not undertake at the trial to

support their denials. Includable in the same category are

defendants’ contention, twice pleaded after the decision in

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964), that the Act

was unconstitutional on the very grounds foreclosed by

McClung; and defendants’ contention that the Act was in

valid because it “ contravenes the will of God” and con

stitutes an interference with the “ free exercise of the De

fendant’s religion.” The district judge should be told that,

in awarding counsel fees, he should include an amount

which fully compensates plaintiffs for the time, effort and

expenses of counsel in overcoming these elements of ex

pense needlessly imposed on them.

Only as to the remaining defenses do I think that de

fendants’ good faith is the issue. If good faith is found not

to have existed as to them, an additional award of counsel

fees on a like basis should be made.

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

For the Fourth Circuit

11a

Opinion and Order of District Court

A nne P. New m an , S haeon W. Neal and

J ohn M ungin ,

Plaintiffs,

v.

P iggxe Pakk E nterprises, I nc., a Corporation,

and L. M aurice B essinger,

Defendants.

Civ. A. No. AC-1605

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

D. South Carolina, Columbia Division

July 28, 1966

O R D E R

Simons, District Judge.

This suit was commenced December 18, 1964 by plain

tiffs, who are Negro citizens and residents of South Caro

lina and of the United States, on behalf of themselves

and others similarly situated, pursuant to Rule 23(a) (3)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Jurisdiction of

this court is expressly conferred by Title II, Section 207

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. Section 2000a-6.1

1 “ §2000a-6. Jurisdiction; exhaustion of other remedies; exclusiveness

of remedies; assertion of rights based on other Federal or State laws and

pursuant of remedies for enforcement of such rights

“ (a) The district courts of the United States shall have jurisdiction

o f proceedings instituted pursuant to this subchapter and shall exer

cise the same without regard to whether the aggrieved party shall

12a

The gravamen of plaintiffs’ complaint is that corporate

defendant operates several restaurants in Columbia and

elsewhere in South Carolina which are places of public

accommodation within the purview of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964; and that defendant violated said Act by

denying service to plaintiffs at certain of its restaurants

on July 3rd and August 12th, 1964 solely upon the ground

that they were Negroes. The complaint further specifically

alleges that in their restaurants defendants serve and

offer to serve interstate travelers; that a substantial por

tion of the goods which they serve move in interstate

commerce; and that defendants’ operations affect com

merce between the states. Plaintiffs ask that defendants

be temporarily and permanently enjoined from discrim

inating against plaintiffs and the class of persons they

represent upon the ground of race, color, religion and

national origin.

Defendants admit jurisdiction of the court under Sec

tion 2000a-6, supra, generally deny the material allega

tions of plaintiffs’ complaint, and specifically deny the

allegations of the complaint which allege that their estab

lishments are places of public accommodation as defined

in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Although defendants

concede that they cater to white trade only and refuse to

Opinion and Order of District Court

have exhausted any administrative or other remedies that may be

provided by law.

“ (b) The remedies provided in this subchapter shall be the exclusive

means o f enforcing the rights based on this subchapter, but nothing

in this subchapter shall preclude any individual or any State or local

agency from asserting any right based on any other Federal or State

law not inconsistent with this subchapter, including any statute or

ordinance requiring nondiscrimination in public establishments or

accommodations, or from pursuing any remedy, civil or criminal,

which may be available for the vindication or enforcement of such

right. Pub. L. 88-352, Title I I , §207, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 245.”

13a

serve members of the Negro race at their restaurants

for on-the-premises consumption of food, they stoutly main

tain that they do not come within the coverage of Section

2000a(b) (2) and (c) (2) of the Act, infra note 2, because

(1) they do not serve the public as required by the Act;

(2) they are not principally engaged in selling food for

consumption on the premises; (3) they do not serve or

offer to serve interstate travelers; and (4) they do not

serve food, a substantial portion of which has moved in

commerce.

Defendants further contend that all foodstuffs served

by them which are processed in this state, including cattle

and hogs slaughtered in South Carolina, although shipped

in commerce from another State to this State, cannot be

considered as moving in interstate commerce under the

Act; that the Act denies defendants “due process of law

and/or equal protection of the law” as guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment; that the phrase “ substantial por

tion of the food which it serves * * * has moved in com

merce” is so vague and indefinite as to be impossible to

determine whether a business operation comes within the

Act; and further, that the Act violates defendants’ “prop

erty right and right of liberty protected by the Fifth

Amendment.”

Defendant Bessinger further contends that the Act vio

lates his freedom of religion under the First Amendment

“ since his religious beliefs compel him to oppose any

integration of the races whatever.”

The constitutionality of the public accommodations sec

tion, Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2000a, has been fully considered and determined

by the United States Supreme Court in Heart of Atlanta

Opinion and Order of District Court

14a

Motel, Inc. v. United States, et al., 379 U.S. 241, 85 S.Ct.

348, 13 L.Ed.2d 258 (1964); Katzenbacli v. McClung, 379

U.S. 294, 85 S.Ct. 377, 13 L.Ed.2d 290 (1964); see also

Willis v. Pickrick Restaurant, D.C., 231 F.Supp. 396 (1964),

appeal dismissed, Maddox v. Willis, 382 U.S. 18, 86 S.Ct.

72, 15 L.Ed.2d 13 (1965).

The constitutional questions posed by defendants herein

were before the Supreme Court in McClung and Atlanta

Motel, supra, and were decided adversely to defendant’s

contentions. Consequently, defendant’s defenses founded

upon the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment, the Fifth Amendment, and

the Commerce Clause of the Constitution are found by

the court to be without merit in view of the McClung and

Atlanta Motel cases, supra. It is noted that in McClung,

Atlanta Motel and Pickrick Restaurant the motel and

restaurants involved were admittedly places of public ac

commodation under the Act, there being no factual issue

as to whether they came within the purview of same.

Neither was any question raised that the restaurants in

volved therein were not principally engaged in selling-

food for consumption on the premises. The sole considera

tion before the lower court and the Supreme Court in

those cases was the question of the constitutionality of

the public accommodations provisions of the Act (Section

2000a).

[2, 3] Neither is the court impressed by defendant Bes-

singer’s contention that the judicial enforcement of the

public accommodations provisions of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 upon which this suit is predicated violates the

free exercise of his religious beliefs in contravention of

the First Amendment to the Constitution. It is unques-

Opinion and Order of District Court

15a

tioned that the First Amendment prohibits compulsion

by law of any creed or the practice of any form of religion,

but it also safeguards the free exercise of one’s chosen

religion. Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421, 82 S.Ct. 1261,

8 L.Ed.2d 601 (1962). The free exercise of one’s beliefs,

however, as distinguished from the absolute right to a

belief, is subject to regulation when religious acts require

accommodation to society. United States v. Ballard, 322

U.S. 78, 64 S.Ct. 882, 88 L.Ed. 1148 (1944) (Mails to

defraud); Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145, 25 L.Ed.

244 (1878) (polygamy conviction); Prince v. Common

wealth of Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158, 64 S.Ct. 438, 88

L.Ed. 645 (1943) (minor in company of ward distributing

religious literature in violation of statute). Undoubtedly

defendant Bessinger has a constitutional right to espouse

the religious beliefs of his own choosing, however, he does

not have the absolute right to exercise and practice such

beliefs in utter disregard of the clear constitutional rights

of other citizens. This court refuses to lend credence

or support to his position that he has a constitutional right

to refuse to serve members of the Negro race in his busi

ness establishments upon the ground that to do so would

violate his sacred religious beliefs.

The sole question for determination under the circum

stances of instant case is whether any or all of defendants’

eating establishments are places of public accommodation

within the meaning and purview of Section 201 of Title II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Section 2000a).2 In ar-

2 “ §2000a. Prohibition against discrimination or segregation in places

of public accommodation— Equal access

“ (a) A ll persons shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of

the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, and accommoda

tions o f any place of public accommodation, as defined in this section,

Opinion and Order of District Court

16a

riving at this determination the court is primarily con

cerned with the following factual and legal questions, which

will he considered in inverse order hereinafter: (1) Is

corporate defendant’s establishments, or any of them, “prin

cipally engaged in selling food for consumption on the

premises” ; (2) Does said defendant at its establishments

serve or offer “ to serve interstate travelers” ; and (3) has

“a substantial portion of the food which it serves, * * * *

or other products which it sells * * * moved in commerce’”?

Should the court’s answer to question # 1 be in the

affirmative, and either questions #2 or # 3 in the alter

native in the affirmative, then such of defendants’ estab

lishments are places of public accommodation within the

Opinion and Order of District Court

without discrimination or segregation on the ground of race, color,

religion, or national origin.

“Establishments affecting interstate commerce or supported in their

activities by State action as places of public accommodation; lodg

ings; facilities principally engaged in selling food for consumption

on the premises; gasoline stations; places of exhibition or entertain

ment; other covered establishments

“ (b) Each of the following establishments which serves the public is

a place of public accommodation within the meaning of this sub

chapter if its operations affect commerce, or if discrimination or

segregation by it is supported by State action:

«^2 ) * * *

“ (2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch counter, soda

fountain, or other facility, principally engaged in selling food for

consumption on the premises, including, but not limited to, any

such facility located on the premises of any retail establishment;

or any gasoline station;

“ (3) » * * ; and

* * *

“ (e) The operations of an establishment affect commerce within the

meaning of this subchapter if (1) * * 0 (2 ) in the case of an estab

lishment described in paragraph (2) o f subsection (b) of this section,

it serves or offers to serve interstate travelers or a substantial por

tion of the food which it serves, or gasoline or other products which

it sells, has moved in commerce; * * * ”

17a

purview of the Act, and plaintiffs are entitled to the

requested relief as to these establishments.

The cause was heard by the court on April 4th and 5tli,

1966. Subsequently excellent briefs and arguments have

been filed by counsel for the parties. After a careful

consideration of the evidence and the law and pursuant

to Rule 52(a) of Federal Rules of Civil Procedure the

court makes its findings of fact and conclusions of law.

F indings of F act

1. Defendant Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., hereinafter

designated as Piggie Park, is a South Carolina corporation

with its principal office in Columbia, South Carolina. De

fendant L. Maurice Bessinger, hereinafter designated as

Bessinger, is the principal stockholder and general man

ager of the corporate defendant.

2. Piggie Park owns, operates, or franchises six eating

establishments specializing in Southern style barbecue

which are located as follows:3 l)P iggie Park No. 1, 1601

Charleston Highway, also being designated as U. S. High

ways Nos. 21, 176 and 321 at the intersection of S. C.

Highway No. 215, in West Columbia, South Carolina; 2)

Piggie Park No. 2 on the Sumter Highway, also being

designated as U. S. Highways Nos. 76 and 378 in Columbia,

South Carolina; 3) Piggie Park No. 3 on the Camden

Highway, also being designated as U. S. Highway No. 1,

in Columbia, S. C .; 4) Piggie Park No. 4 on Broad Street

Extension, which is also designated as U. S. Highways

Nos. 76, 378 and 521 in Sumter, South Carolina; 5) Piggie

3 The official South Carolina State Highway Department Primary Sys

tem Map for 1965-66 has been used in determining the United States and

State Highway designations.

Opinion and Order of District Court

18a

Park No. 6 on Highway No. 291 By-Pass North, which

connects U. S. Highways Nos. 25, 29, and Interstate High

ways Nos. 85 and 385 in Greenville, South Carolina; and

6) Piggie Park No. 7, also known as “Little Joe’s Sandwich

Shop,” at 1430 Main Street in Columbia, South Carolina.

All of Piggie Park’s eating places are of the drive-in type

with the exception of Piggie Park No. 7 also known as

“Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop” in downtown Columbia.

In order to be served at one of the drive-ins a customer

drives upon the premises in his automobile and places his

order through an intercom located on the teletray imme

diately adjacent to and left of his parked position. After

pushing a button located on the teletray his order is taken

by an employee inside the building who is generally out

of sight of the customer. When the order is prepared a

curb girl then delivers the food or beverage to the cus

tomers’ car and collects for same. This is generally the

only contact which any of defendant’s employees has with

any customer unless additional service is desired. The orders

are served in disposable paper plates and cups, and may

be consumed by the customer in his automobile on the

premises or after he drives away, solely at his option,.

There are no tables and chairs, or counters, bars or stools

at any of the drive-ins sufficient to accommodate any ap

preciable number of patrons. The service is geared to ser

vice in the customers’ cars. Piggie Park claims the distinc

tion of operating the first drive-in specializing in barbecue

although it sells other types of short orders. The barbecue

meat and hash comprising a substantial majority of its

sales are sold in bulk by the pound or the quart, as well

as in individual orders. Customers are encouraged to con

sume the food off the premises by its service in disposable

Opinion and Order of District Court

19a

containers, with no chinaware or silver eating utensils be

ing used. At the five drive-ins the carry-out business for

off-the-premises consumption averages fifty percent during

the year, depending upon the season and the weather.4

3. Piggie Park No. 7, or “Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop” ,

in downtown Columbia is the one exception to the drive-in

type operation. Defendant operates this establishment as

a cafeteria type sandwich shop offering three-minute ser

vice, also specializing in barbecue, with table and chair

seating capacity for sixty customers and where the food is

primarily consumed on the premises. It is located in the

prime shopping area of Columbia’s Main Street; ninety

percent of its business is between 11:00 a.m. and 2 :30 p.m.,

with the majority of its customers being office workers,

clerks and downtown shoppers. Its business hours corre

spond generally with those of the surrounding retail stores.

4 The uncontradicted testimony of defendant Bessinger at pp. 222-223

of Tr. was as follows:

“ Q. Mr. Bessinger, with reference to the total volume of your busi

ness, do you know how much of your business is carry out, or take

away business from your drive-ins?

“ A . Yes. O f course, as I said, we try to encourage this to the

maximum degree. This would average 5 0 % . Carry out would aver

age 5 0 % . I say average, because in the real cold temperature it

would jump up to eighty to ninety percent; in the real hot tempera

ture it would also jump up to eighty to ninety percent. So it will

have an overall percentage o f my business that I know for a fact is

carried back to the office or carried back home or carried on a picnic,

what have you.

“ Q. Do you in fact have facilities for bulk carrying out?

“ A . Yes we sell a lot of barbecue by the pound. W e sell a lot of

quarts o f hash by the quart, and slaw by the quarts, and rice by the

quarts. W e built up quite a big business on that.

“ Q. Carry off?

“ A . Oh absolutely, and July 4th we sell several tons o f barbecue.”

It is noted that plaintiff’s counsel did not cross-examine Bessinger to

any extent in reference to the above testimony and no evidence was offered

to counter or rebut the same.

Opinion and Order of District Court

20a

4. Two of the Negro plaintiffs were denied service by

Piggie Park No. 2 on the Sumter Highway in Columbia on

August 12, 1964 when they drove upon the premises in

their automobile. At first a waitress who came out seeing

that they were colored went back into the building with

out taking their order or saying anything to them. Shortly

a man with an order pad came to their car, he also refused

to take their order, and gave no reason or excuse for this

denial of service, although other white customers were be

ing served there at that time. The fact that Piggie Park

at all six of its eating places denies full and equal service

to Negroes because of their race is uncontested and com

pletely established by the evidence. The limited Negro cus

tomers who are served must place and pick up their orders

at the kitchen windows and are not permitted to consume

their purchases on the premises. Thus, Negroes because

of race are being denied full service and are victims of dis

crimination at all of Piggie Park’s eating establishments.

5. No effort is made by defendant to determine whether

a Negro customer who purchases food on a take-out basis

is an interstate traveler.

6. Piggie Park displays on each of its establishments

one modest sign located generally in the front window ad

vising that it does not serve interstate travelers. In its

newspaper advertisements is included a notice in small

print at the bottom of the ad advising that “we do not serve

interstate travelers” .5 No mention of this practice is in

cluded in any of its radio advertisements for business. Al

though some testimony and business records indicate that

Opinion and Order of District Court

5 See defendant’s Exhibit “ G” .

21a

defendant has refused to serve a very limited number of in

terstate travelers in the past, the inescapable conclusion

demanded by all of the circumstances before the court is

that many interstate travelers do obtain service at all of

its locations. Except for the small sign in the window no

steps are taken by defendant at “Little Joe’s Sandwich

Shop” to determine whether or not a customer is an inter

state traveler, and at its drive-ins no attempt to determine

a customer’s travel status is claimed to be made until after

his order is prepared and actually delivered to his auto

mobile. If the curb girl who serves the order notices that

a customer’s car hears an out-of-state license, she is in

structed to inquire whether such customer is an interstate

traveler or is residing in South Carolina. There is testi

mony to the effect that if the customer admits that he is

an interstate tourist service is denied to him although the

food has been especially prepared to his order. No inquiry

whatever is ever made of any customers who are riding-

in an automobile with South Carolina license plates. In

asmuch as all five of defendant’s drive-ins are located at

most strategic positions upon main and much traveled inter

state highways and especially in view of the limited action

taken by defendant to determine the travel status of its

customers the court can only conclude that defendant does

serve interstate travelers at all of its locations.6

6 The only direct evidence adduced by plaintiffs tending to establish

service to interstate travelers was the testimony o f their witness, Sharon

A . Miles, a white woman who entered “ Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop” on

April 2, 1966 and obtained service without any question. Upon cross-

examination she admitted that she and her husband who is the Columbia

Director for the South Carolina Board of Voter Education Project had

resided in this state for one and one-half years. Apparently plaintiffs

made no attempt to conduct any surveys at defendant’s drive-in establish

ments to show that customers in out-of-state automobiles were actually

being served at any o f defendant’s locations.

Opinion and Order of District Court

22a

7. Several employees of wholesale food companies which

regularly sell foodstuffs and other merchandise to Piggie

Park testified that the bulk of the food and related prod

ucts sold by their firms to defendant was and is obtained

by them from producers and suppliers beyond the State of

South Carolina as follows:

(a) Greenwood Packing Company, a large supplier

of meat products, purchases two-thirds of its merchan

dise from suppliers outside of South Carolina. They

sell primarily pork shoulders, spareribs and Boston

Butt (a cut off the shoulder). All hogs are live when

purchased by it. They are thereafter slaughtered, cut

up, processed and packed within the State of South

Carolina. Its total sales to defendant during the fiscal

year 1964-65 was $39,663.91 and $15,148.24 from June

1 through December 12, 1965. Its sales to defendant

are made without keeping records to indicate which of

its meat is produced or slaughtered in South Carolina

as contrasted to that which is purchased by it from out-

of-state already processed and ready for sale to de

fendant.

(b) Dreher Packing Company of Columbia, South

Carolina, a wholesale distributor of luncheon meats,

pork sausage, beef and ground beef patties regularly

sells meat products to defendant. Approximately

eighty percent of the meat products sold by it to

Piggie Park is acquired from suppliers from outside

of South Carolina, and no records are maintained to

distinguish the in-state from the out-of-state items.

However, all of its meat products is processed in

some manner by it within the state before sale and

Opinion and Order of District Court

23a

delivery to defendant. It considers defendant as one

of its good customers.

(c) Holly Farms Poultry Industry, which secures

eighty-five percent to ninety percent of its chickens

from a North Carolina supplier, sells a small quantity

of meat each month to defendant.

(d) Piggie Park no longer sells beer at any of its

locations, its licenses having expired in June 1965.

Prior to that time substantial quantities of beer were

purchased from Schafer Distributing Company of

Columbia, none of which was brewed in South Caro

lina. It also purchased beer from Acme Distributing

Company, distributors of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer

which was shipped into the state from Peoria, Illinois.

(e) Defendant purchases pepsi-cola syrup by the

gallon from Pepsi-Cola Bottling Company of Colum

bia. The ingredients which go into this syrup are

shipped into South Carolina from New York, Ken

tucky and Georgia. During 1965 defendant purchased

1,374 gallons of the syrup at $2.75 per gallon, includ

ing tax.

(f) Defendant regularly buys fresh, frozen and

canned foods from Pearce-Young-Angel of Columbia,

a large wholesaler. With the exception of its eggs all

items regularly sold to defendant, including limes,

onions, beef patties, cabbage, lettuce, tomatoes, french

fried potatoes, bell peppers, shrimp and cheese are

produced out of South Carolina. Defendant’s pur

chases from this firm during the fiscal year 1964-65

amounted to $41,255.45, most of which had moved into

the state in commerce.

Opinion and Order of District Court

24a

(g) Thomas and Howard Company of Columbia, a

large wholesale distributor of food and related prod

ucts, regularly sells merchandise to defendant such

as coca-cola syrup, sugar and salt. Altogether it

handles approximately 7,000 items with about sixty

percent or more being food items, mostly produced or

manufactured in states other than South Carolina.

Thus a large quantity and variety of the products

purchased by defendant from this company have

moved in commerce. Although only about sixty per

cent of the items purchased from it are foodstuffs

the remaining forty percent of the items as herein

enumerated are necessary and related to either the

preparation of defendant’s food for sale or its service

of same.

(h) Epes-Fitzgerald Company sells to defendant

paper products consisting of cups, plates, napkins,

waxed paper, paper bags and boxes. Of these items

all are manufactured outside of South Carolina except

the paper cups and the paper boxes.

(i) Trusdale Wholesale Meat Company of Columbia

sold a substantial quantity of meat products to de

fendant up until August 1965. Since that time they

have made no sales to the defendant. This supplier

received less than five percent of its products from

outside of South Carolina.

(j) Roddey Packing Company of Columbia also

supplies meat products to defendant. Approximately

twenty percent of its hogs are purchased live out-of-

state and then slaughtered and processed in South

Carolina before sale to its customers.

Opinion and Order of District Court

25a

(k) Southeastern Poultry Company of Columbia is

another supplier of chickens to defendant. All of its

chickens are grown and processed in South Carolina.

During 1964 its sales to defendant totalled $6,895.82

and in 1965 totalled $13,757.48.

8. Mrs. Merle Brigman, defendant’s bookkeeper and

chief buyer of its merchandise, testified that she had made

a compilation from defendant’s records which she keeps

to determine what percentage of food served by defen

dant was either produced, grown or processed in South

Carolina. In arriving at her percentages she did not in

clude as out-of-state foods such items as live hogs and

cows purchased out-of-state by their suppliers when

slaughtering or any processing were done in the state

prior to delivery to defendant. Neither did she include

pepsi-cola syrup concentrate purchased from the Pepsi