Barclay v. Florida Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

December 29, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Barclay v. Florida Brief for Petitioner, 1982. 4b821e78-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dccc73bf-bbac-4d63-a914-2996d70f98a1/barclay-v-florida-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

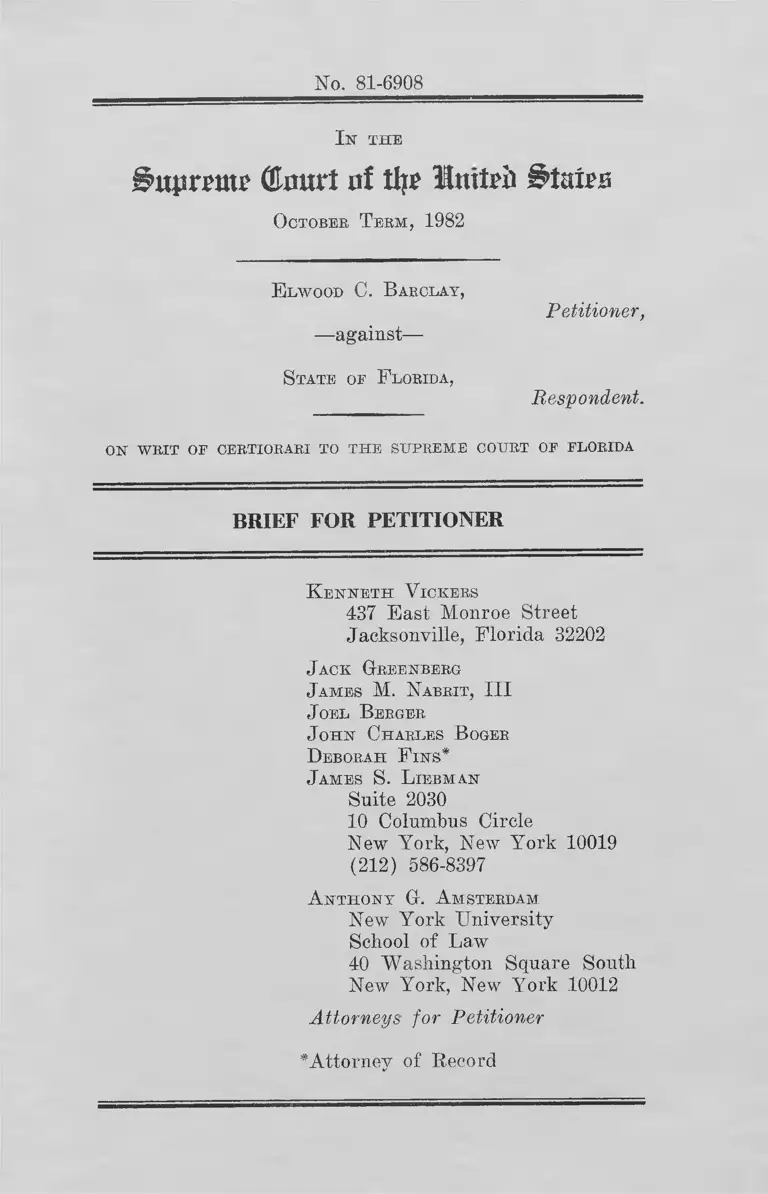

No. 81-6908

I n t h e

i$uprrmr ( ta r t of tfyr Mnttrii Stairs

O ctober T e r m , 1982

E lwood C . B arclay,

—against—

S tate oe F lorida ,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

K e n n e t h V ic k er s

437 East Monroe Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

J oel B erger

J o h n C h a rles B oger

D eborah F in s *

J am es S. L ieb m a n

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

A nthony ' G. A msterdam

New York University

School of Law

40 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

Attorneys for Petitioner

* Attorney of Record

(i)

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

(1) Whether a death sentence, imposed over

a jury recommendation of life, v i o

l a tes the E i g h t h and F o u r t e e n t h

A m e n d m e n t s when it is bas e d upon

a trial j u d g e ' s f i n d i n g s of (a)

factors not included in the roster

of s t a t u t o r y a g g r a v a t i n g c i r c u m

stances; (b) factors found only by

distorting the statutory aggravating

circumstances beyond recognition; and

(c) factors freighted with emotions

arising from the judge's prior exper

iences, extraneous to the circum

stances of the crime or the character

of the defendant?

(2) W h e t h e r a ’dea t h s e n t e n c e i m p o s e d

through such an arbitrary process can

nonetheless be executed because the

(ii)

trial judge may additionally have

found one or more properly applicable

statutory aggravating factors?

(iii)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ................. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............... vi

OPINIONS BELOW ....................... 1

JURISDICTION ......................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED .............. . . 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .............. 4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................. 24

ARGUMENT .............................. 27

I. BARCLAY'S DEATH SENTENCE WAS

THE PRODUCT OF A CAPRICIOUS

SENTENCING PROCESS, FLOUTING

THE SAFEGUARDS WHICH PROFFITT

RELIED UPON TO ASSURE AGAINST

ARBITRARINESS IN DEALING OUT

THE DEATH PENALTY ............. 27

A. Barclay's Death Sentence

Rests Preponderately Upon

Lawless Findings and

Considerations Not

Channelled By The Florida

Capital Sentencing

Statute ..................... 27

1. Findings of nonstatutory

aggravating cir

cumstances ................. 29

IV

Page

a. Prior criminal

activity .................. 29

b. "Under sentence of im

prisonment" and pre

vious conviction of

a violent felony .......... 32

2. Lawless findings of statu

tory aggravating cir

cumstances ................. 33

a. Under sentence of im

prisonment ................. 33

b. Previous conviction of

a violent felony .......... 36

c. Great risk of death

to many persons ........... 40

d. Murder committed during a

kidnapping ................. 48

e. Murder committed to disrupt

a governmental function, and

"especially heinous, atro

cious or cruel" ........... 51

3. An additional nonstatutory

aggravating circumstance,

and its relationship to

Judge Olliff's personal

experience ................. 58

B. A Sentencing Process So

Lawless as The One Which

Condemned Barclay To Die

Violates the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments ....... 63

- V

Page

II. THE UNCONSTITUTIONAL PROCESS

THAT PRODUCED BARCLAY'S DEATH

SENTENCE REQUIRES ITS

REVERSAL ......................... 83

A. The "Elledge rules" ...... 84

B. Nonarbitrary Application

Of The First Elledge Rule

Requires the Vacation of

Barclay's Death Sen

tence ....................... 87

C. Application Of The Second

Elledge Rule To Salvage

Barclay's Death Sentence

Would Itself Be Federally

Unconstitutional ......... 94

CONCLUSION ........................... 106

APPENDIX ............................... 1a

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Page

Adams v. State, 412 So. 2d 850

(Fla. 1982) ............................ 53

Alvord v. State, 322 So. 2d 533

(Fla. 1 975) ...... 43

Antone v. State, 382 So. 2d 1205

(Fla. 1 980) ................ 52

Bachellar v. Maryland, 397 U.S. 564

(1970) ................................... 102

Barclay v. State, 343 So. 2d 1266

(Fla. 1977) ............................ passim

Barclay v. State, 362 So. 2d 657

(Fla. 1 978) 2

Barclay v. State, 411 So. 2d 1310

(Fla. 1981) ............................. 2,23

Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S.

146 (1 964) ........ 93

Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625

( 1980) ................. 103

Bell v. Watkins, ___ F.2d ___ ,

No. 81-4358 (5th Cir. Dec. 6,

1982) ................... 72

Blair v. State, 406 So. 2d 1103

(Fla. 1981) ....................... 40,51,76,85

Vll

Bolender v. State, So. 2d ,

1982 Fla. Law Wkly, SCO 490

(No. 59,333) (Oct. 28, 1982) .....

Brown v. State, 381 So. 2d 690

(Fla. 1980) .........................

Carnes v. State, No. 74-2024,

74-2131, Cir. Ct., 4th Jud. Cir.,

Duval Cty, Fla. (Nov. 19, 1974) ..

Clark v. State, 379 So. 2d 97 (Fla

1 979) ................................

Cooper v. State, 336 So.2d 1133

(Fla. 1976) .........................

Cramer v. United States, 325 U.S.

(1945) ...............................

Demps v. State, 395 So. 2d 501

(Fla. 1982) .........................

Dobbert v. Florida, 432 U.S. 282

(1977) ...............................

Dobbert v. State, 375 So. 2d 1069

(Fla. 1979) .........................

Dougan v. State, 398 So. 2d 439

(Fla. 1981) .........................

Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104

( 1982) ..............................

Elledge v. State, 346 So. 2d 998

(Fla. 1977) .........................

Enmund v. Florida, U.S. , 73

L .Ed.2d 1140 (1982) ...............

Page

.. passim

41 ,76,85

passim

52

71 ,93

102

56

57,61

passim

35,39,57

63,94,105

passim

97

V1X1

Page

Enmund v. State, 399 So.2d 1362

(Fla. 1981) .............. 97

Ferguson v. State, 417 So. 2d 639

(Fla. 1 982) ........................... 41,51

Ferguson v. State, 417 So. 2d

631 (Fla. 1 982) ........................ 34

Fleming v. State, 374 So. 2d 954

(Fla. 1 979) ............................. 85

Ford v. State, 374 So. 2d 496 (Fla.

1979) .................................... passim

Francois v. State, 407 So. 2d 885

(Fla. 1981) ............................. 51

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238

( 1972) ...................... 24,69,70,81

Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349

(1977) ................................. 2,21,62

Gardner v. State, 313 So. 2d 675

(Fla. 1 975) ............................. 53

Gilvin v. State, 418 So. 2d 996

(Fla. 1 982) ............................. 51,56

Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420

(1980) ....................... passim

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153

(1976) ..... passim

Gregory v. Chicago, 394 U.S. 111

( 1 969) ..... 102

- IX

Page

Halliwell v. State, 323 So. 2d 557

(Fla. 1 975) ........................... 56

Hargrave v. State, 366 So. 2d 1

(Fla. 1 978) ............................. 86

Harris v. Pulley, ___ F.2d ___ ,

No. 82-5246 (9th Cir. Sept. 16,

1982) .................................... 73

Harvard v. State, 414 So. 2d 1032

(Fla. 1 982) ............................ 54

Henry v. Wainwright, 661 F.2d 56

(5th Cir. 1 981 ) ........................ 72,106

Hitchcock v. State, 413 So. 2d 741

(Fla. 1 982) ................. 53

Holmes v. State, 374 So. 2d 944

(Fla. 1 979) ............................. 52

Hopper v. Evans, U.S. , 72

L . Ed. 2d 368 (1982) ...................... 65

Huckaby v. State, 343 So. 2d 29

(Fla. 1 977) ............................. 42,77

In re Florida Rules of Criminal

Procedure, 343 So. 2d 1247 (Fla.

1977) ......... 76

Jackson v. State, 366 So. 2d 752

(Fla. 1 978) ............................ 91

Jacobs v. State, 396 So. 2d 713

(Fla. 1981) ............................. 41,52

Johnson v. State, 393 So. 2d 1069

(Fla. 1980) ......... 41,55,93,95

- x -

Page

Jones v. State, 411 So. 2d 165

(Fla. 1 982) .................... ........ 51

Jordan v. Watkins, 681 F .2d 1067

(5th Cir. 1 982) ........................ 72

Kampff v. State, 371 So. 2d 1007

(Fla. 1979) ....................... 40,41,54

Lewis v. State, 398 So. 2d 432

(Fla. 1981) ................... P assim

Lewis v. State, 377 So. 2d 640

(Fla. 1979) .......... 41,56,85

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586

(1978) ................................... P assim

Lucas v. State, 376 So. 2d 1149

(Fla. 1 979) ........ 42,76,85

Maggard v. State, 399 So.2d 973

(Fla. 1981) ............................ 29

Mann v. State, 420 So. 2d 578

(Fla. 1 982) ............................ 37

McCampbell v. State, ___ So. 2d

, 1982 Fla. Law Wkly, SCO 492

jNo. 57,026) (Oct. 28, 1 982) .......... 76

McCaskill & Williams v. State, 344

So. 2d 1276 (Fla. 1 977) .............. 43

McCray v. State, 416 So. 2d 804

(Fla. 1 982) ............................ 55

XI

Page

Meeks v. State, 339 So. 2d 186

(Fla. 1976) ............................ 52,91

Meeks v. State, 336 So. 2d 1142

(Fla. 1 976) ............................ 52

Menendez v. State, 368 So. 2d 1278

(Fla. 1979) ............................ passim

Messer v. State, 403 So. 2d 341

(Fla. 1981) ............................ 90

Mikenas v. State, 367 So. 2d 606

(Fla. 1978) ...................... 30,43,77,86

Miller v. State, 373 So. 2d 882

(Fla. 1 979) ............................ 76

Mines v. State, 390 So. 2d 332

(Fla. 1 980) ............................ 42

Moody v. State, 418 So. 2d 989

(Fla. 1982) ......................... 79,85,96

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama ex rel.

Patterson, 357 U.S. 449 (1958) ...... 94

Odom v. State, 403 So. 2d 936 (Fla.

1981) .................................... 40,76

Peek v. State, 395 So. 2d 492 (Fla.

1981) .................................... 34

Perry v. State, 395 So. 2d 170

(Fla. 1 980) ........................... 76

Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242

(1976) .................................. passim

- X l l -

Page

Proffitt v. State, 315 So. 2d 461

(Fla. 1 975) .......................... 43,77

Proffitt v. Wainwright, 685 F.2d

1227 ( 1 1th Cir. 1 982) ................. 72

Provence v. State, 337 So. 2d 783

(Fla. 1976) .......................... 31,77,78

Purdy v. State, 343 So. 2d 4 (Fla.

1977) .................................... 77

Raulerson v. State, 358 So. 2d 826

(Fla. 1 978) ............................. 52

Riley v. State, 366 So. 2d 19 (Fla.

1978) .................................... passim

Roberts v. Louisiana, 431 U.S 633

(1 977) ............... 80

Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S.

325 ( 1976) .............................. 80

Salvatore v. State, 366 So. 2d 745

(Fla. 1 978) ............................ 91

Sandstrom v. Montana, 442 U.S. 510

(Fla. 1 979) ............................ 102

Sawyer v. State, 313 So. 2d 680

(Fla. 1 975) ........... 75

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners,

353 U.S. 232 (1957) .............. 74

Simmons v. State, 419 So. 2d 316

(Fla. 1 982) ............................ 56

X l l l

Page

Slater v. State, 316 So. 2d 539

(Fla. 1 975) ............................ 43

Smith v. North Carolina, ___ U.S.

, 51 U.S.L.W. 3418 (U.S.,

Nov. 29, 1982) ........................ 98

Smith v. State, 365 So. 2d 704

(Fla. 1978) ........................... 91

Smith v. State, 407 So. 2d 894

(Fla. 1981) ........................... 51

Songer v. State, 365 So. 2d 696

(Fla. 1978) ........................ 52,71,93

Spaziano v. State, 393 So. 2d 1119

(Fla. 1981) ........................... . 38,76

State v. Bartholomew, P.2d ,

No. 48346-9 (Sup. Ct. Wash. Nov. 24,

1 982) ......... ........................ 72

State v. Dixon, 283 So. 2d 1 (Fla.

1973) ................................. 53,55,71

Street v. New York, 394 U.S. 576

(1969) ................................. 102,104

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S.

359 ( 1 931 ) .................... 102,103 ,104,105

Tafero v. State, 403 So. 2d 355

(Fla. 1981) .......................... 42,52,91

Tedder v. State, 322 So. 2d 908

(Fla. 1975) ........................... . 56,57

xiv -

Page

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1

(1 949) .................... .............. 102

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516

(1945) ................................. 102,104

Thompson v. State, 328 So. 2d 1

(Fla. 1 976) ............................. 77

Townsend v. Burke, 334 U.S. 736

(1 948) ................................... 107

Vaught v. State, 401 So. 2d 147

(Fla. 1 982) ........... 54,86

Washington v. State, 362 So. 2d 658

(Fla. 1 978) ............................. 43,52

Welty v. State, 402 So. 2d 1159

(Fla. 1981) ............................. 52

White v. State, 403 So. 2d 331

(Fla. 1981) ....................... 46,52,93,95

White v. State, 415 So. 2d 719

(Fla. 1 982) ............................. 52

Williams v. North Carolina, 317

U.S. 287 (1942) .......................... 102

Williams v. State, 386 So. 2d 538

(Fla. 1980) ............................. passim

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S.

510 (1 968) .............................. 92

Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S.

280 ( 1 976) .............................. 100

XV

Page

Yates v. United States, 354 U.S.

298 ( 1957) ............................. 102

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356

(1886) .................................. 70

Zant v. Stephens, U.S. ,

72 L.Ed.2d 222 (1982) ........ 64,97,103,105

Zeigler v. State, 402 So. 2d 365

(Fla. 1 981) ............................. 52,85

STATUTES

Fla. R. Crim. Proc. 3.800 ............ 76

Fla. Stat. §782.04 .................... 7,82

Fla. Stat. §921.141.................... passim

28 U.S.C. §1257 ........................ 2

No. 81-6908

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1982

ELWOOD C. BARCLAY,

Petitioner,

against

STATE OF FLORIDA,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF

FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINIONS BELOW

The judgment and findings of fact en

tered when petitioner was initially sentenced

to die by the Circuit Court of Duval County,

Florida are unreported and appear at J.A.

2

1-53. The initial opinion of the Supreme

Court of Florida affirming petitioner's con

viction of first degree murder and sentence

of death by electrocution is reported in

Barclay v. State, 343 So.2d 1266 (Fla. 1977);

J .A . 54-77.

The su bsequent order of the Supreme

Court of Florida vacating the sentence of

death and r e manding for res e n t e n c i n g in

light of Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349

(1977), is reported in Barclay v. Sta t e ,

362 So.2d 657 (Fla. 1978); J.A. 78-81. The

judgment and findings of fact on resentencing

are unreported and appear at J.A. 82-141. The

o p inion of the Supreme Court of Florida

affirming the r e i m p o s i t i o n of the death

sentence is reported in Barclay v. State, 411

So.2d 1310 (Fla. 1981); J.A. 142-45.

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this Court rests upon

28 U.S.C. §1257(3), the petitioner having as-

3

serted below and asserting here a deprivation

of rights secured by the Constitution of the

United States.

The judgment of the Supreme Court of

Florida was entered on June 4 , 1981. A

timely petition for rehearing was denied by

that court on April 14, 1982. The petition

for certiorari was filed on June 16, 1 982

and granted on November 8, 1982. U. S .

f 51 U.S.L.W. 3362 (U.S., Nov. 8, 1 982 )

(No. 81-6908) .

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the Eighth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States,

which provides:

Excessive bail shall not be required,

nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel

and unusual punis h m e n t s inflicted;

and the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States, which provides, in

pertinent part:

- 4

[N]or s h a l l any S t a t e d e p r i v e any

person of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law....

This case also involves the following

provisions of the statutes of the State of

Florida, which are set forth in the Appendix

to this brief: Fla. Stat. §§782.04, 921.141.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

1 . Introduction

On June 17, 1974, the dead body of eigh-

teen-year-old Stephen A. Orlando was dis

covered on a dirt road in Jacksonville Beach,

Florida. (T.T. 169 ) . —̂ The cause of death

was a bullet which entered the left ear.

V References to the transcript of Barclay's trial,

held in the Circuit Court of the Fourth Judicial Dis

trict in and for Duval County, Florida, from February

21, 1975, through March 4, 1975, are indicated by the

abbreviation "T.T." followed by the number of the

page(s) on which the reference may be found. The abbrev

iation "V.T." refers to the transcript of the voir dire;

"S.T." to the transcript of the separate penalty trial

held on March 5, 1975; "R." to the record on appeal;

"R.T." to the transcript of the resentencing hearing on

June 23, 1979, October 23, 1979, and April 18, 1980;

"A." to the Appendix to Petitioner's Brief; and "J.A."

to the Joint Appendix.

5

(T.T. 126, 133). Orlando also sustained

another bullet wound in the cheek, and

several superficial stab wounds. (T.T. 126).

A note was found under a small pocketknife

lying on his stomach. (T.T. 317-18, 321,

324).—/ The note stated that "the revolution"

had begun and that the "atrocities and brutal

izing" of black people by the "oppressive

state" would no longer go "unpunished." The

note was signed "The Black Revolutionary Army.

All power to the people." (J.A. 57; Barclay v .

State, 343 So.2d 1 266 , 1 267 (Fla. 1 977 )).

Several days later Orlando's mother and

local radio and television stations received

cassette tapes in which the speakers declared

that Orlando was the first victim in "the rev

olution." (T.T. 157, 408-09, 1022). The

tapes contained diatribes against "white rac

ist America," listed the historic grievances

2/ There is some evidence that the note may have been

stuck to the body with the knife before it was found.

(T.T. 324-25).

6

of black people, and compared the murder of

Orlando to the lynchings and other murders of

black people in America. (T.T. 1014-43). The

tapes described Orlando's murder, claiming he

had begged for mercy "just as black people did

when you took them and hung them to the trees,

burned their houses down, threw bombs in the

same church that practices the same religion

that you forced on these people, my people."

(T.T. 1019-20). Each tape ended, "Your Black

Liberation Army." (T.T. 1021, 1023, 1026,

1031, 1042-43).

Three months later, five young black men,

Jacob Dougan, Dwyne Crittendon, Brad Evans,

William Hearn and petitioner Elwood Barclay,

were arrested for Orlando's murder. All but

Hearn were indicted for first degree murder by

a grand jury for Duval County, Florida. (R.

5). Hearn was charged by information with

second degree murder and allowed to plead

guilty to that offense in exchange for his

7

testimony against the other four. (T.T.

1349). The four were tried together. The

jury returned verdicts finding Crittendon and

Evans guilty of murder in the second degree,

and finding Barclay and Dougan guilty of mur

der in the first degree. (T.T. 23 0 1 -02 )..=®/

After a penalty trial under Florida's bifur

cated sentencing system, the jury recommended

that Barclay be sentenced to life but Dougan

be sentenced to death. (S.T. 179-80). The

trial judge refused to follow the jury's

recommendation as to Barclay and sentenced

both young men to death. (J.A. 52).

2. The Trial

a. The Guilt Trial

Hearn was the state's key witness at the

trial. He testified that he knew the four

defendants from a karate class they all

attended taught by Dougan. (T.T. 1351). On

3/ The statute defining first degree murder, Fla.

Stat. §782.04, is set forth in the Appendix to this

brief, A. 1a-2a.

8

Sunday, June 16, 1974, Hearn was playing

basketball with Crittendon, Evans and Barclay.

(T.T. 1352-54). Dougan arrived and asked

Hearn if he had his gun with him, because

Dougan wanted "to go out and scare some

people." (T.T. 1353). Dougan said he was

willing to do it by himself, but that it would

be better if they all went together. When

Hearn asked what it was they were going to do,

Dougan said he'd tell them later. (T.T.

1354). He instructed them all to go home and

change into dark clothes. (T.T. 1354-55).

The five young men met again at Barclay's

house about an hour later, sometime around

8:00 or 8:30 in the evening. (T.T. 1356).

Hearn brought a .22 caliber automatic pistol

with him, which he gave to Dougan. (T.T.

1356, 1358). Barclay had a "small pocket-

knife." (T.T. 1357). The five got into

Hearn's two-door car with Hearn driving, Crit

tendon in the front passenger seat, and the

9

rest in the back seat. Dougan told them he

would instruct them on where to go and what to

do. (T.T. 1358, 1381).

After driving for a short time, Dougan

instructed Hearn to pull the car to the side

of the road under a street light. Hearn did,

and Dougan wrote out a note. Dougan read the

note to the group and passed it around. Hearn

asked again what they were going to do, and

Dougan again replied he would tell them later.

He told Hearn to drive on, and Heard did so.

Dougan continued to direct the route until

they arrived at a monument. There Dougan

announced that they would "catch a white devil

and kill him and leave the note on him."

(T.T. 1359-61).

For the next couple of hours, the five

drove around Jacksonville, looking unsuccess

fully for an isolated person in an isolated

area. (T.T. 1363-65). Finally the group

headed to Jacksonville Beach, arriving about

10

10:30 p.m. There they saw Orlando, a young

white man, hitchhiking by the side of the

road. Hearn stopped the car, and Orlando

entered the car and sat between Dougan and

Evans in the back seat. (T.T. 1370). The car

headed south toward the beach. Orlando told

the group his name, and they each told him

their names. Orlando asked them if they

"smoked reefer" (marijuana). Dougan replied

that they did, and asked Orlando if he had any

with him. Orlando said he did not, but could

get them some from a house on 12th Street.

(T.T. 1370). When they got to 12th Street,

Dougan told Hearn to drive past the street and

keep going straight. Hearn did. (T.T. 1371).

Dougan directed the route once again. A

police car passed by, and Orlando said, "That

pig sure is watching us close." Someone asked

him if he disliked police officers, and he

replied, "Well, my father's one." Dougan

then told Orlando that he was taking him to

meet a black girl who could give him some

drugs. (T.T. 1372). As they approached a

road, Dougan announced they were getting

close to where the girl lived. (T.T. 1377).

They turned, then turned again down a dirt

road into a wooded area. Dougan told Hearn

to stop the car. He did. (T.T. 1 380).— /

Hearn opened the door on the driver's

side and held his seat back but did not

leave the car. Crittendon opened the door

on the passenger side, got out, and held

the seat back. Barclay got out on Hearn's

4/ The trial judge's original sentencing order stated

that Orlando was driven to the scene of the homicide

"[ajgainst his will and over his protest" (J.A. 9).

This finding was quoted in the opinion of the Florida

Supreme Court on Barclay's first appeal. (J.A. 56;

Barclay v. State, supra, 343 So.2d at 1267). There is

simply no evidence in the record to support such a

finding, and the finding does not reappear in the second

sentencing order (J.A. 82-141). The only evidence of

Orlando's statements or actions during the car ride

canes from Hearn's testimony at the trial (T.T. 1370-

79), and the entire substance of those statements and

actions has been described in our text above. The judge

and the prosecutor agreed that Orlando had entered the

car voluntarily (T.T. 1913), and the prosecutor acknowl

edged during his closing argument to the jury that

Orlando's first reaction of "protest" occurred after the

car stopped and Dougan ordered Orlando to step outside.

(T.T. 2026).

12

side, Dougan on Crittendon's . As Dougan got

out he said, "This is it, sucker, get out."

Orlando got out behind Dougan and broke to run.

(T.T. 1381). Dougan hit Orlando in the back

with the gun. Barclay, who apparently had

moved around the car, then grabbed Orlando.

Evans got out of the car and stood behind

Dougan; Orlando was standing between Dougan

and Barclay. (T.T. 1384). Hearn watched from

the front seat of the car, looking back over

his shoulder at the group. (T.T. 1383). He

saw Dougan put his hand on Orlando's back and

jerk it, throwing Orlando to the ground. Bar

clay "started stabbing" Orlando, who offered

to give them a "bag of reefer." (T.T. 1385).

Barclay stabbed Orlando more than once, al

though Hearn could not say how many times.

Dougan told Barclay to move back, and then

fired twice. (T.T. 1385). Dougan pulled the

gun up, shook it, and tried to fire again but

the gun wouldn't go off. (T.T. 1386). Evans

13

moved up close, went down toward the body a

couple of times, and then stood up with the

note in his hand. Barclay took the note, went

down toward the body with it, and then Evans,

Dougan and Barclay returned to the front of

the car. (T.T. 1 387). The car headed back

to Barclay's house. (T.T. 1388).

Hearn next saw the others on Tuesday

at the karate class. Dougan told Hearn to

bring his car the next day because there was

going to be a meeting at the house of another

member of the karate class, James Mattison.

(T.T 1396). The next evening after the class

ended, Hearn, Dougan, Crittendon, Evans,

Barclay and three other students from the

class (Otis Bess, Edred Black and James

Mattison) met at Mattison's house. (T.T.

1397). There Crittendon, Evans, Dougan and

Barclay discussed the murder. Dougan had

brought a tape recorder and he suggested

that everyone present make tapes. No one

disagreed. (T.T. 1399). Dougan then wrote

14 -

out a script for each person to read into

the microphone. (T.T. 1402). Barclay sug

gested some additions to Dougan's script.

(T.T. 1403).

Hearn testified that all the tapes made

that night referred to the killing, and that he

personally saw Black, Dougan and Barclay

making tapes. (T.T. 1399, 1403). He said

that although the taped messages depicted

Orlando as begging for mercy, Orlando never

had. Barclay only added that to "make it seem

more aggressive." (T.T. 1403).

Black, Bess and Mattison also testified

for the State. Each admitted being present

while the tapes were made, and Black and

Mattison admitted making tapes themselves,

similar in all respects to those made by

Barclay and Dougan. (T.T. 949, 977, 1182).

The three men each denied any direct knowledge

of Orlando's death. Black and Mattison claimed

to have made the tapes from a script prepared

15

by Dougan. (T.T. 990, 996 , 1 1 82 ). They

corroborated Hearn's testimony that Dougan was

the person who suggested making the tapes,

brought the tape recorder, and directed the

production of the tapes. (T.T. 938, 950,

958-59, 986, 1155-56, 1160, 1181, 1276, 1283,

1307). Five of the tapes — only those

recorded by Barclay and Dougan — were intro

duced into evidence and played for the jury.

(T.T. 1009, 1014-43). Black testified to

incriminating statements made by Crittendon

(T.T. 1159), Evans (T.T. 1 159, 1 183), -^Dougan

(T.T. 1182) and Barclay (T.T. 1183). Bess

corroborated the testimony to some extent.

(T.T. 1279, 1281, 1287).

An expert for the State testified that

the note found on Orlando's body was written

by Dougan. (T.T. 1112). Another testified

that a cartridge case found by the body was

5/ Evans allegedly stated he tried to stick the knife

in the victim's chest but it kept folding up. (T.T.

1183).

16

fired from Hearn's gun. (T.T. 1550).

Crittenden, Dougan, Evans and Barclay

each took the stand. Crittendon, Dougan and

Barclay admitted having made the tapes, but

claimed they did so at Mattison's urging and

direction. (T.T. 1608, 1616, 1773, 1782,

1805). All four denied complicity in the

homicide. (T.T. 1607, 1609, 1773, 1789,

1817).

After each side had rested, the trial

judge called all counsel into chambers to

discuss the charges that would be given to

the jury before its deliberations on guilt

or innocence. It was at first agreed by all

counsel and the trial judge that no felony

murder charge would be given because of a lack

of any basis in the record for such a charge.

(T.T. 1912-13, 1918-19). However, when the

court later brought up the possibility of a

charge on murder in the third degree — which

is defined in Florida as murder in the course

of a felony not enumerated in the first and

17

second degree felony-murder provisions —

defense counsel decided that they were unwill

ing to waive a charge on the lesser included

offense of murder in the third degree.

(T.T. 1924, 1975). The state attorney then

insisted that the felony-murder provisions

of first and second degree murder be charged

as well, to avoid confusing the jury; and the

trial judge ultimately agreed. (T.T. 1925,

1975). The jury was subsequently instructed

on both premeditated and felony-murder. (T.T.

2230, 2232).

b. The Sentencing Trial

At the sentencing hearing, Dougan produced

several witnesses to testify to his good char

acter. (S.T. 59, 61 , 64, 66, 70). No addi

tional testimony was presented on Barclay's

behalf. The State then brought Hearn back to

testify about a second homicide committed by

Crittendon and Evans at Dougan's direction,

where Hearn once again acted as driver and

18 -

observer. (S.T. 90-111). Barclay was in no

way implicated in the second homicide, and was

unquestionably out of town when it occurred.

(S.T. 109-110).

During closing argument, Barclay's at

torney informed the jury that Barclay was

t w e n t y - t h r e e years old, m a rried and the

father of five children, had never been

convicted of a crime and had no criminal

charges pending against him (S.T. 154). He

highlighted the disparity in treatment of

Hearn, Crittendon and Evans, who all faced

punishment for only second degree murder and

would be eligible for parole immediately upon

their incarceration, while a life sentence for

Barclay under the first degree murder statute

would make him ineligible for parole until he

was forty-eight years old. (S.T. 156). He

further noted that Barclay was a follower, not

a leader, and that he acted under the domina

tion of another. (S.T. 155).

19

In its verdict, the jury expressly found

that "sufficient aggravating circumstances do

not exist to justify a sentence of death; ...

[and that] sufficient mitigating circumstances

do exist which outweigh any aggravating circum

stances," and the jury concluded that life

imprisonment was the appropriate punishment for

Barclay. (S.T. 180).

The trial judge dismissed the jury and

ordered that a presentence investigation

report be prepared on each defendant. (S.T.

181). On April 10 , 1975 , he imposed death

sentences on both Barclay and Dougan, despite

the jury's verdict of life for Barclay,

issuing a single order applicable to both

young men. (J.A. 52; see J.A. 1-53).

3. Post-Trial Proceedings

Barclay's and Dougan's automatic appeals

to the Florida Supreme Court were heard and

decided together. (J.A. 54; Barclay v. State,

343 So.2d 1266 (Fla. 1977).) The court af-

20

firmed the convictions and death sentences

for both, holding that if it did not affirm

Barclay's death sentence, "[t]wo co-perpetra

tors who participated equally in the crime

would have disparate sentences...." (J.A. 72;

343 So.2d at 1271). The court did not review

each of the trial court's findings of aggra

vating circumstances applied to Barclay. In

stead, it noted the aggravating circumstances

found in Dougan's case, held that those find

ings were "well documented,"— ^and recited that

"[a]s regards Barclay ... virtually the same

considerations apply with respect to conse-

6/ The Florida Supreme Court's description of the trial

court's findings is puzzling. It correctly states that

the trial judge found no mitigating circumstances as to

Dougan, and then lists among the facts pertaining to

Dougan that he "had no significant history of prior

criminal activity," unquestionably a statutory mitigat

ing factor. (Fla. Stat. §921.141(6)(a) ("the defendant

has no significant history of prior criminal activity.")

(J.A. 68; 343 So.2d at 1270). In discussing the aggra

vating circumstances applicable to Dougan, the Florida

Supreme Court dropped a footnote describing the aggra

vating circumstances which the trial judge purportedly

did not find; in fact, however, he unambiguously did

find two of those. Compare J.A. 34, 35 with J.A. 69;

343 So.2d at 1271 n.3.

21

quences of the criminal episode." (J.A. 71;

343 So.2d at 1271). The court did not discuss

the factual basis for those aggravating cir

cumstances found by the trial court in Bar

clay's case which are directed toward the

character of the defendant rather than the

circumstances of the offense, Fla. Stat.

§921.141(5)(a) ("The capital felony was com

mitted by a person under sentence of imprison

ment"), and Fla. Stat. §921.141(5)(b) ("The

defendant was previously convicted of another

capital felony or a felony involving the use

or threat of violence to the person"). Both

of those factors are at issue in the present

proceeding.

The Supreme Court of Florida subsequently

vacated the death sentences imposed on both

Barclay and Dougan in light of this Court's

decision in Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349

(1977), since there was a possibility that the

trial court had relied on a presentence invest

igation report which the defendants had had no

22

opportunity to rebut, deny or explain.

New counsel was appointed for Barclay,

and a resentencing hearing was held in three

parts on June 23, 1979, October 23, 1979 and

April 18, 1980, before the trial judge who

had imposed the death sentence originally. A

law enforcement officer who had investigated

the case was called by the defense (R.T. 4),

and testified that Dougan was the leader of

the group (R.T. 20-21), although Barclay was

"second in command" (R.T. 24) because he was

older and smarter than Crittendon, Evans and

Hearn. (R.T. 28). Counsel for Barclay argued

that the trial judge's original sentencing

order contained a number of errors, including

the finding of a nonstatutory aggravating

circumstance and the overbroad interpreta

tion of several statutory aggravating circum

stances. (R.T. 56-94). The trial judge re

imposed the death sentence. (R.T. 128). His

new sentencing order was a virtual duplication

of his original order, different only in the

23

omission of a few findings that he had made

earlier, principally those findings relating

to Dougan, whose resentencing had been separ

ately conducted. (J.A. 89).—/

Once again the Florida Supreme Court

affirmed on appeal, this time with no analysis

at all of the trial judge's order. (J.A. 142—

45; Barclay v. State, 411 So.2d 1310 (Fla.

1981)). The court deemed all sentencing

issues other than those concerning conformity

with its Gardner remand order to have been

decided by the original appeal. (J.A. 144-45).

Rehearing was denied on a three-to-three vote

2/ The Florida death-sentencing statute, Fla. Stat.

§921.141 (Supp. 1976-1977) was amended in 1979 to

clarify that mitigating circumstances are not limited to

those in the statute, and to add an aggravating circum

stance ("The capital felony was a homicide and was

committed in a cold, calculated, and premeditated manner

without any pretense of moral or legal justification").

See Fla. Stat. §921.141(5)(i)(Supp. 1982). The jury

recommended life and the judge sentenced Barclay to

death under the older version of the statute. On resen

tencing in 1980, the trial judge appears to have used

the older version as well, because his recitation of the

aggravating circumstances considered did not include

Fla. Stat. §921.141—(5)(i). See Sentencing Order, J.A.

134.

24

of the Justices. (J.A. 146).—^ This proceed

ing on certiorari followed.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Elwood Barclay's death sentence was im

posed through procedures bearing scant re

semblance to those which this Court approved

in Proffitt v, Florida, 428 U.S. 242, 251

(1976) (opinion of Justices Stewart, Powell

and Stevens), as appearing " (o]n their face

... to meet the constitutional deficiencies

identified in Furman [v. Georgia, 408 U.S.

238 (1972)]."

In Part 1(A) below, we show that Bar

clay's trial judge overrode a jury recommenda

tion of life and sentenced Barclay to die on

the basis of (1) factors not included in the

list of "statutory aggravating circumstances,"

Proffitt v. Florida, supra, 428 U.S. at 250,

8/ Of the nine justices in the two appeals, four

dissented from the affirmance of the death sentence, and

a fifth (who had not heard either appeal) would have

voted for rehearing of the decision affirming the

sentence after the Gardner remand.

25

which are supposed to give "specific and

detailed guidance" to the capital sentencing

decision, _id. at 253; (2) factors found only

by distorting the statutory aggravating

circumstances beyond recognition, so as to

nullify their effect as guarantors of

even minimal "consistency in the imposition

[of the death penalty] at the trial court

level," jLcU at 252; and (3) factors not

"focus [ed] on the circumstances of the crime

and the character of the individual defen

dant," id. at 251. In Part 1(B), we demon

strate that this sentencing procedure was

unconstitutional, as the very antithesis of

"an informed, focused, guided, and objective

inquiry into the question whether [Barclay]

... should be sentenced to death," i d . at

259.

In Part II below, we show that the

affirmance of the resulting death sentence

by the Florida Supreme Court violated every

- 26

precept of a system of appellate review in

which the "reasons [for a death sentence],

and the evidence supporting them, are consci

entiously reviewed by a court which, because

of its statewide jurisdiction, can assure

consistency, fairness, and rationality in the

evenhanded operation of the state law," id.

at 259-60. Part II proceeds by (A) describing

the rules of Elledge v. State, 346 So.2d 998

(Fla. 1977), which purport to define the

circumstances under which lawless findings of

aggravating circumstances require reversal of

a death sentence by the Florida Supreme

Court; (B) showing that Barclay's death sen

tence must be reversed under any consistent

and evenhanded administration of the Elledge

rules; and (C) showing that, insofar as the

Elledge rules do not require the reversal

of Barclay's death sentence, they cannot be

squared with Due Process or the Eighth

Amendment.

27

ARGUMENT

I. BARCLAY'S DEATH SENTENCE WAS THE PRODUCT

OF A CAPR ICIOUS SENTENCING PROCESS,

FLOUTING THE SAFEGUARDS WHICH PROFFITT

RELIED UPON TO ASSURE AGAINST ARBITRA

RINESS IN DEALING OUT THE DEATH PENALTY

A. Barclay's Death Sentence Rests Pre

ponderate^ Upon Lawless Findings

and Considerations Not Channelled

By The Florida Capital Sentencing

Statute

This Court is familiar with the manner

in which the Florida death-penalty statute

is supposed to work. First, an advisory

jury "is directed to consider '[wjhether

sufficient mitigating circumstances exist

. . . which outweigh the aggravating circum

stances found to exist; and ... [biased on

these considerations, whether the defendant

should be sentenced to life [imprisonment] or

death.'" Proffitt v. Florida, supra, 428 U.S.

at 248. The sentencing judge is supposed to

follow a jury's recommendation of life unless

"'the facts suggesting a sentence of death

- 28 -

[are] ... so clear and convincing that

virtually no reasonable person could dif

fer. ' " I_ <3 . at 249. The facts governing

this latter decision are required to be set

forth in writing, following a process in

which the trial "judge is also directed to

weigh the statutory aggravating and miti

gating circumstances . . . ." jrd. at 250.

Since Barclay's jury recommended life

-- e x p l i c i t l y finding that "sufficient

m i t i gating circums t a n c e s do exist which

outweigh any aggravating c i r c u mstances"

(S.T. 180) — the crux of the present case

is the set of findings upon which the trial

judge relied to override the jury's recom

mendation and impose a death sentence. We

turn immediately to these, and show that

they include (1) findings of nonstatutory

aggravating circumstances, (2) lawless find

ings of statutory aggravating circumstances,

29

and (3) findings relating to the judge's World

War II experiences.

1. Findings of nonstatutory aggravating

circumstances________________

a- Prior criminal activity

Fla. Stat. § 921.141(6)(a ) makes it a

mitigating circumstance that " [tjhe defendant

has no significant history of prior criminal

activity." The statute does not conversely

make the presence of a significant history of

prior criminal activity an a g g r a v a t i n g

circumstance. See Fla. Stat. §921.141(5);

gjL_9- »■ Maggard v. State, 399 So.2d 973, 977-78

(Fla. 1981). Nevertheless, Barclay's trial

judge, the Honorable R. Hudson Olliff, made

the following sentencing finding:

"A. WHETHER DEFENDANT HAD NO SIGNIFI

CANT HISTORY OF PRIOR CRIMINAL

ACTIVITY

FACT:

The defendant, Barclay, has an

extensive criminal record of

seven prior arrests. It shows

that he had previously been on

30

probation for the crime of

uttering a forgery, and that

subsequently that probation was

revoked and he was sentenced

to a term of six months County

Jail. It also shows that he

had previously been on five

years probation for the crime

of Breaking and Entering and

Grand Larceny. There are also

a number of misdemeanor crimes

charged. (See PSI)

CONCLUSION:

There is an aggravating, rather

than a mitigating circumstance

as to the defendant Barclay

b e c a u s e of his e x t e n s i v e

record showing at least one

prior felony conviction and

one prior felony probation."

(J .A . 108-09).

Lest there be any doubt that the absence

of the mitigating circumstance defined by

§921.141(6)(a) is not "an aggravating ... cir

cumstance," the Florida Supreme Court expli

citly so held in Mikenas v. State, 367 So. 2d

606, 610 (Fla. 1978). Barclay's counsel

called Mikenas to Judge Olliff's attention

(R.T. 61), to no avail. In addition, the

Florida Supreme Court has repeatedly held

31

that, even as to prior convictions of violent

felonies, which do constitute proper statutory-

aggravating circumstances under Fla. Stat.

§921.141(5)(b) [see pages 37-38 infra], "mere

arrests" do not q u a lify as convictions,

Provence v. State, 337 So.2d 783, 786 (Fla.

1976), and any "charge [which has] ... not

resulted in a conviction at the time of the

[capital] trial" must be considered an im

proper "nonstatutory aggravating factor,"

Blledqe v. State, supra, 346 So.2d at 1002.—/

If a defendant does have prior violent felony

convictions, these must be proved by "evi

dence, either at trial or during the sentenc

ing phase," in order to warrant their consid

eration as a statutory aggravating factor

within § 921.141(5)(b ); their consideration

"based solely on information contained in the

9/ We shall see in note 24 and accompanying text infra,

that the Florida Supreme Court itself has now clearly

taken the position that consideration of nonstatutory

aggravating circumstances as the basis for a death

sentence is improper.

32

presentence investigation report" is forbid

den. Williams v. State, 386 So.2d 538, 542-43

(Fla. 1980). Thus, on three distinct and

unmistakable counts, Judge Olliff's finding

that " [t]here is an aggravating, rather

than a mitigating circumstance as to the

defendant Barclay because of his extensive

record" (J.A. 108) falls outside the contem

plation of any statutory aggravating circum

stance recognized by Florida law.

b. "Under sentence of imprisonment"

and previous conviction of a

violent felony_________ _________

Two additional aggravating circumstances

found by Judge Olliff should probably be

classified as nonstatutory, since his own

discussion of them negates their statutory

elements. In each case, his findings follow

an identical logic: The statutory aggravating

circumstances do not exist [or have not been

proved] factually; however, the facts show

something resembling them; t h e r e f o r e , an

33

aggravating circumstance is found. Because

these two findings do have some connection —

albeit no lawful connection — to statutory-

aggravating factors, we consider them in

the following section. They are items

(2)(a) and (b), immediately below.

2. Lawless findings of statutory aggra-

vating circumstances__________________

a * Under sentence of imprisonment

Fla. Stat. § 921.141(5)(a ) makes it an ag

gravating circumstance that " [t]he capital

felony was committed by a person under sen

tence of imprisonment." Judge Olliff found:

"A. WHETHER THE DEFENDANT WAS UNDER

SENTENCE OF IMPRISONMENT WHEN HE

COMMITTED THE MURDER OF WHICH HE

HAS BEEN CONVICTED

FACT:

The defendant, Barclay, was

not u n d e r s e n t e n c e of i m

p r i s o n m e n t at the time of

the commission of this murder.

His rap sheet shows seven prior

arrests and he had previously

been convicted of a felony and

had been on felony probation.

34

CONCLUSION:

Although not imprisoned, the

criminal record of B a rclay

is an a g g r a v a t i n g c i r c u m

stance ."

(J.A. 120-21).

Like the fact that Barclay "had pre

viously been convicted of a felony," the

fact that he "had been on felony probation"

was a thing of the past. Barclay was not

on probat ion at the time of the present

offense. Even if he were, the "under sentence

of imprisonment" aggravating circumstance of

§921.141(5)(a) would plainly not apply, since

the Florida Supreme Court has construed the

statute as meaning exactly what it says. To

come within §921.141(5)(a ), a defendant must

be "under sentence of imprisonment" at the

time of the capital felony, not under sentence

of probation. E.g,, Ferguson v. State, 417

So.2d 631, 636 (Fla. 1982); Peek v. State, 395

So.2d 492, 499 (Fla. 1981). Where, as Judge

Olliff found here, a defendant "was not under

35

sentence of imprisonment at the time of the

commission of his murder," no amount of cy

pres reasoning can make his "criminal record

... an aggravating circumstance" (J.A. 121),

as Judge Olliff then went on to find.— ^

See Ford v. St ate, 374 So.2d 496, 501 n.1,

502 (Fla. 1979).

10/ Judge Olliff has sentenced five defendants to

death, overriding a jury recommendation of life in four

of the five cases. One of the four defendants in whose

cases Judge Olliff ignored a jury's life recommendation

committed suicide on death row before his appeal could

be heard. Carnes v. State, No. 74-2024, 74-2131, Cir.

Ct. 4th Jud. Cir., Duval County, Florida (Nov. 19,

1974); Miami Herald, July 4, 1975, at 9-A. One case was

reversed by the Florida Supreme Court because of im

proper consideration of aggravating circumstances.

Lewis v. State, 398 So.2d 432 (Fla. 1981). Two were

affirmed. Barclay v. State, supra; Dobbert v. State,

375 So.2d 1069 (Fla. 1979).

Judge Olliff found the "under sentence of imprison

ment" aggravating circumstance to be applicable in each

of the five cases in which he imposed a death sentence,

although it could properly be applied in only one of

those five. Lewis v. State, supra, 398 So.2d at 438. In

Dougan v. State, 398 So.2d 439, 441 (Fla. 1981) (Mc

Donald, J., dissenting), Judge Olliff found that al

though Dougan was not under sentence of imprisonment, he

had once been convicted of criminal contempt, and the

aggravating circumstance therefore applied. In Dobbert

v. State, supra, 375 So.2d at 1071, Judge Olliff found

that although Dobbert was not under sentence of impris

onment, he had prevented his own imprisonment for child

36

b. Previous conviction of a vio-

________________________

Fla. Stat. §921.141(5)(b ) makes it an

aggravating circumstance that "[t]he defendant

was previously convicted of another capital

felony or of a felony involving the use or

threat of violence to the person." Judge

Olliff found:

"B. WHETHER THE DEFENDANT HAD PREVIOUSLY

BEEN CONVICTED OF ANOTHER CAPITAL

FELONY OR OF A FELONY INVOLVING THE

USE OR THREAT OF VIOLENCE TO THE

PERSON

FACT:

The defendant, Barclay, was

p r e v i o u s l y c o n v i c t e d of

breaking and entering with

intent to commit the felonv

of grand larceny. It is not

known if such prior felony

10/ (continued)

abuse by intimidating his victims and deceiving the

authorities, and he had been convicted twice in the

past. In Carnes v. State, supra, Judge Olliff found

that although Carnes was not under sentence of imprison

ment, he was out on bond on another charge at the time

of the offense and therefore the aggravating cirucum-

stance applied. (A. 29a).

37

involved the use or threat

of v i o l e n c e in the crime.

However, such crime can and

often does involve violence

or threat of violence - if

t h e r e is a p e r s o n in the

building broken into.

CONCLUSION:

This is more of an aggravat

ing than a negative circum

stance . "

(J.A . 121-22).

Once again, this £y pres finding of an

aggravating circumstance is wholly lawless.

The Florida Supreme Court has held that the

aggravating circumstance defined by §921.141-

(5) (b ) also means what it says: only capital

felonies or felonies which by definition

involve the use or threat of violence (such as

armed robbery) may be used in aggravation,

unless there is proof beyond a reasonable

doubt that the offense underlying the prior

conviction actually involved the use or threat

of violence. See, e,g. , Mann v. State, 420

So.2d 578, 580 (Fla. 1982) (burglary convic-

38

tion may not be used as an aggravating fac

tor); Spaziano v. State? 393 So.2d 1119,

1122-23 (Fla. 1981) ("nonviolent felony"

conviction "must be excluded as [an] aggravat

ing factor]]"); Ford v. State, supra, 374

So. 2d at 501 n.l, 502 (conviction of breaking

and entering to commit a felony may not be

used as an aggravating factor). In Lewis v .

State, 398 So.2d 432, 438 (Fla. 1981), the

Florida Supreme Court expressly found that

"two convict:ions of breaking and entering

with intent to commit a felony" did not

fall "within the meaning of this aggravat-

ing circumstance as defined by the statute,"

because the statute "refers to life-threaten

ing crimes in which the perpetrator comes in

direct contact with a human victim." More

over, as we have noted at pages 31-32, supra,

even if Barclay's prior breaking-and-entering

offense had involved "the use or threat of

violence in the crime" — facts which Judge

39

Olliff conceded were "not known" (J.A. 121),

i .e., unproved despite the State's obligation

to prove the elements of every aggravating

circumstance beyond a reasonable doubt,

Williams v. State, supra, 386 So.2d at 542 —

Judge Olliff could not properly have found an

aggravating circumstance under §921.141(5)(b)

based upon the PSI alone, as he purported to

do here.— / Williams v. State, supra, 386

So.2d at 543.— /

1V Again, Judge Olliff found this aggravating circum

stance to be present in all but one of the cases in

which he sentenced a defendant to death. He found it

applicable in Dougan v. State, supra, 398 So.2d at 441,

although Dougan's only prior record involved a criminal

contempt conviction with no evidence of violence. He

found it applicable in Lewis v. State, supra, 398 So.2d

at 438, although Lewis' prior record consisted of two

breaking and enterings with intent to commit a felony,

two escapes, one grand larceny, and one possession of a

firearm by a convicted felon. (A. 49a-50a). The Flor

ida Supreme Court disapproved the finding in Lewis, as

noted on page 38, supra. Judge Olliff found it applic

able in Carnes v. State, supra, although Carnes had

never been convicted of any offense, but had been

charged with a felony involving violence. (A. 30a).

The Florida Supreme Court has held that charges not

reduced to a conviction may not be used in aggrava

tion. See page 31 supra.

J_2/ Conpliance with the requirement of Williams would

not have been superfluous in this case. The PSI relied

40 -

c . G r e a t r i s k of d e a t h to m a n y

Fla. Stat. § 921.141(5)(c ) makes it an

aggravating circumstance that "[t]he defen

dant kno w i n g l y created a great risk of

death to many persons." Recognizing the

need to give this statutory aggravating

circumstance a limiting construction which

would assure some measure of consistency in

its application, see Kampff v. Sta t e , 371

So.2d 1007, 1009 (Fla. 1979 ), the Florida

Supreme Court has interpreted it to require

( 1 ) that the risk of death created be to

"many" people, not just to one or two,-LI/

and (2) that there must be something in the

12/ (continued)

upon by Judge Olliff to establish Barclay's record

contains two different versions of that record, and a

comparison of the two produces only confusion as to the

actual number and nature of Barclay's encounters

with the law. (A. 77a-79a).

-11/ Blair v. State, 406 So.2d 1103, 1107-08, (Fla.

1981) (victim alone with defendant in house, child

outside mowing lawn; held, "one or two" is not "many"

persons); Odom v. State, 403 So.2d 936, 942 (Fla. 1981)

(two women present with victim in house when defendant

and accomplice fired shotguns through window; held, not

41

nature of the homicidal act itself (as in ar

son or the use of explosives), or in the de

fendant's conduct immediately surrounding the

homicidal act, which created such a risk.li/

13/ (continued)

"many" persons); Lewis (Robert) v. State, supra, 398

So.2d at 438 (same; Odom's accomplice); Jacobs v. State,

396 So.2d 713, 718 (Fla. 1981)("Although the shooting

occurred in a rest area close to a major highway, it was

done with pistols at close range where few, not many,

suffered a risk of injury"); Johnson v. State, 393 So.2d

1069, 1073 (Fla. 1981) ("gun battle" in pharmacy, three

other people present; held, not "many" persons); Wil

liams v. State, supra, 386 So.2d at 541-42 (two people

shot in bed; held, not "many" persons); Brown v. State,

381 So.2d 690, 696 (Fla. 1980) (robbery of shop, no

indication of number of persons present; held, no proof

that "many" persons were endangered); Lewis (Enoch) v.

State, 377 So.2d 640, 646 (Fla. 1979) (victim's son and

daughter in yard witti victim when several shots were

fired; held, not "many" persons); Dobbert v. State,

supra, 375 So.2d at 1070 (defendant killed one child,

physically abused three other children; held, not "many"

persons); Karnpff v. State, supra, 371 So.2d at 1009-10

(defendant fired five shots at victim in heavily tra

veled retail bakery where two others were present; held,

not "many" persons).

W Bolender v. State, So.2d , 1982 Fla. Law

Wkly, SCO 490, 491 (No. 59,333) (Oct. 28, 1982) (other

people present at scene of homicide, but defendant

"never directed his actions toward any of the uninvolved

people, and the means by which he inflicted the injur

ies, the gun, knife and baseball bat, were not used to

endanger the lives of those individuals"); Ferguson

v. State, 417 So.2d 639, 643, 645 (Fla. 1982) (eight

People in house, each shot by defendant or accomplice

- 42 -

14/ (continued)

while bound, all but two killed; each homicide committed

without risk to others; held, aggravating circumstance

inapplicable); Tafero v. State, 403 So.2d 355, 362 (Fla.

1981) ("attempting to run a roadblock and being stopped

by police gunfire does not constitute 'great risk' to

'many persons' as we defined those terms in Kampff");

Mines v. State, 390 So.2d 332, 337 (Fla. 1980) (defen

dant killed victim in van, then stopped passing motorist

whom he hit with a machete; he fled in the car at high

speed, took another woman hostage; finding of "great

risk" vacated because only conduct surrounding the

homicide of the victim, not after-occurring acts,

may provide the basis for "great risk"); Dobbert v .

State, supra, 375 So.2d at 1070 (murder by strangulation

did not create "great risk" of death to others despite

defendant's violent abuse of his several children at

other times); Elledge v. State, supra, 346 So.2d at 1004

(defendant committed another homicide in another city

after the victim was killed; "[i]t is only conduct

surrounding the capital felony for which the defendant

is being sentenced which properly may be considered" as

a basis for a finding of "great risk").

We must acknowledge that this aggravating circum

stance has been found in a handful of cases in which the

standards enunciated by the Florida Supreme Court

have not been followed. Lucas v. State, 376 So.2d 1149,

1153 (Fla. 1979) ("raging gun battle" but only three

people present); Ford v. State, supra, 374 So.2d at 497,

500-02 n.1 (defendant threatened victims of robbery with

gun; drove at high speeds creating a risk to others on

the road) (compare with Tafero v. State, supra);

Huckaby v. State, 343 So.2d 29 (Fla. 1977) (defendant

convicted of sexual battery of a child, "sincere threats

on the lives of his nine children and wife over the

43

Judge Olliff based his finding of the

"great risk" aggravating circumstance— /on

14/ (continued)

course of many years" often resulting in actual harm

considered sufficient (compare with Dobbert v. State,

supra); Alvord v. State, 322 So.2d 533, 535 (Fla. 1975)

(defendant murdered three woman by strangulation). In

another small number of cases the Florida Supreme

Court neither approved nor disapproved the finding of

"great risk" by the trial court. Most of these cases

were reversed on other grounds. Mikenas v. State, 367

So.2d 606 (Fla. 1978) (shoot-out during robbery of

convenience store, number of people present not indi

cated; reversed because of consideration of nonstatutory

aggravating circumstances); Washington v. State, 362

So.2d 658, 660, 663 (Fla. 1978) (four victims of robbery

shot at close range while bound, one killed; death

sentence affirmed); McCaskill & Williams v. State, 344

So.2d 1276, 1277, 1280 (Fla. 1977) (thirty-five to forty

people in liquor store during hold-up, gun battle

outside store as participants fled; death sentences

reversed because jury recommendation of life was reason

able); Slater v. State, 316 So.2d 539, 540, 542 (Fla.

1975) (only one victim present, but threat existed to

"any unknown persons who might have chanced into the

office;" death sentence reversed because jury recommen

dation of life was reasonable); Proffitt v. State, 315

So.2d 460, 461, 467 (Fla. 1975) aff'd sub nom. Proffitt

v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242 (1976) (victim in bed stabbed

once in chest; wife sleeping beside him was pushed down

by intruder when she awoke; death sentence affirmed).

15/ Yet again, Judge Olliff found this aggravating

circumstance to be present in every case in which he

imposed a death sentence. The finding was vacated

by the Florida Supreme Court in both Lewis v. State,

44

the fact that the defendants passed over

several other people before O r l a n d o was

selected as the victim (J.A. 122-23), and on

the potential danger created by the "call for

revolution and racial war" contained in the

tapes sent to the news media several days

after the homicide. (J.A. 123-24). Neither

of these features of the case brings it

properly within the Florida Supreme Court's

usual construction of the aggravating circum

stance:

(i) The fact that the defendants

may have passed by and rejected other victims

before finding and killing Orlando does not

establish that Orlando's murder was committed

15/ (continued)

supra, 398 So.2d at 438 and Dobbert v. State, supra, 398

So.2d at 1070. (See n. 13 supra.) In Carnes v. State,

supra, there were two people present in the house,

although in another room, when the defendant shot

the victim. (A. 13a-14a). Judge Olliff found the

aggravating circumstance to be applicable because

of the defendant's mistreatment of the two other people

after the homicide was completed. (A. 31a-33a).

45

in such a fashion as to create a great risk of

death to many persons. Dougan and his confed

erates set out to kill one person; they

searched until they found one alone; they took

him to a still lonelier spot, where he was the

only person present in addition to the confed

erates at the time of the killing. To find

that the 'casing' of other victims elsewhere

prior to the homicide makes this aggravating

circumstance applicable would be to find that

every robber who passes several stores, every

rapist who walks the street looking for a

victim, has, by his very decision to avoid the

presence of other people, created a "great

risk of death to many people." If this reason

ing were allowed, there would simply be "no

principled way to distinguish this case, in

which the death penalty was imposed, from

the many cases in which it was not." Godfrey

v. Florida, 446 U.S. 420, 433 (1980) (plural

ity opinion).

46

(ii) Reliance on the "call to

revolution" fares no better. It violates

both the principle that behavior subsequent

to the homicide (here the production of the

tape recordings) cannot be considered as

establishing the "great risk" aggravating

circumstance, see note 14 supra, and the

principle "that a person may not be condemned

for what might have occurred. The attempt to

predict future conduct cannot be used as a

basis to sustain an aggravating circumstance."

White v. State, 403 So.2d 331, 337 (Fla. 1981)

(emphasis in original).

We recognize that the Florida Supreme

Court affirmed the finding of this aggravating

circumstance in its opinion on the first of

Barclay's two appeals. (J.A. 70; Barclay v .

State, supra, 343 So.2d at 1271 n.4). In do

ing so, however, it made no effort to ration

alize the finding by any logic which would

render it consistent with the substantial body

47

of the court's own decisions that have inter

preted the "great risk" statutory circumstance

in a way which would make it inapplicable

here. See notes 13 and 14 s u p r a . The

conclusionary statement that the finding is

"well documented in the record before us,"

(J.A. 70; Barclay v. State, supra, 343 So.2d

at 1271) therefore brings the case to this

Court in a posture identical to Godfrey v .

Georgia, supra, 446 U.S. at 432, where "the

State Supreme Court [had] simply asserted

that the verdict was 'factually substan

tiated,'" although not by any consistent

reasoning that this Court could discern.

What this implies at best is that the Florida

Supreme Court itself has here — and perhaps

in some other cases as well, see the second

paragraph of note 14 supra — failed to

observe with regularity its own professed

interpretations of Fla. Stat. §921.141(5)(c).

See also notes 16 and 17 infra. If these

- 48

failures can be taken together with their

opposites as constituting the law of Florida,

then Judge Olliff's finding of the "great

risk" circumstance in Barclay's case was not

indeed "lawless" in the sense of departing

from the law; it was "lawless" in the more

fundamental sense of lacking any law to follow

or depart from.

d. Murder committed during a kid-

n a p p i n g__________

Fla. Stat. § 921.141(5)(d ) makes it an

aggravating circumstance that "[t]he capital

felony was committed while the defendant was

engaged, or was an accomplice, in the commis

sion of ... any ... kidnapping ...." Judge

Olliff found this aggravating circumstance

(J.A. 125-27); and, at first blush, it might

well seem to apply to the facts as he sets

them forth. There are, however, two problems

with this finding. First, the facts as re

lated by Judge Olliff are nowhere to be found

in the record. Second, the judge himself ruled

49

in the first instance that there was insuffi

cient evidence of a kidnapping in this case.

Judge Olliff recites in his sentencing

findings that the defendants "by force and/or

threats kept [Orlando] ... in their car until

they found an a p propriate place for the

murder." (J.A. 126). But the only witness

who testified about the circumstances of the

car ride, William Hearn, said that Orlando got

in the car voluntarily, joked and exchanged

pleasantries, and rode with the defendants

without any threat or force being used. (T.T.

1369-72). There is no evidence that he pro

tested in the slightest when Dougan ordered

Hearn to pass the street which Orlando had

designated as the one where they could buy

some marijuana, and instead to proceed to

another place where they could get drugs from

a black woman. It was only when Dougan told

Orlando to get out of the car at the site of

the homicide that Orlando first indicated any

- 50

unwillingness to accompany the occupants of

the car in which he had hitched a ride.

More importantly, Judge Olliff himself

deemed the evidence insufficient to estab

lish a kidnapping. During the charge confer

ence at the close of the trial on guilt, all

counsel and the trial judge agreed that the

felony-murder provisions of the first and

second degree murder statutes which included

kidnapping as one of the predicate felonies

would not be read to the jury because they

were not applicable on the facts proved at

trial. (T.T. 1912-1913, 1918-19). A felony

murder instruction was eventually given only

because counsel for the defendants refused

to waive an instruction on the lesser offense

of third degree murder (murder during the

course of a nonenu m e r a t e d felony) (T.T.

1924-1975), and the instruction would be too

confusing and incomprehensible unless the jury

had received instructions on first and second

51

degree felony-murder spelling out the enumer

ated felonies. (T.T. 1925, 1975).

e. Murder committed to disrupt a

g o v e r nmental function, and

"especially heinous, atrocious

or cruel"_________________________

The two remaining aggravating circum

stances found by Judge Olliff pose considerab

ly greater difficulty in analysis, the first

(that "the capital felony was committed to

disrupt or hinder the lawful exercise of any

governmental function or the enforcement of

laws," Fla. Stat. § 921.141(5)(g )) because

the Florida Supreme Court has said so little

1 6/about it that no clear standards emerge;— '

16/ The "hinder law enforcement" aggravating circum

stance has been found by the trial court in twenty-five

cases reviewed by the Florida Supreme Court on appeal.

In all but eleven of the cases, the circumstance was

applied to a factual situation in which a victim or

bystander witness of a felony was then killed by the

felon, apparently to avoid prosecution for the underly

ing felony. See Gilven v. State, 418 So.2d 996, 1000

(Fla. 1982); Ferguson v. State, 417 So.2d 639, 642-43

(Fla. 1982); Jones v. State, 411 So.2d 165, 168 (Fla.

1982); Smith v. State, 407 So.2d 894, 903 (Fla. 1981);

Francois v. State, 407 So.2d 885, 890 (Fla. 1981);

Blair v. State. 406 So.2d 1103, 1108-09 (Fla. 1981);

52

the second (that the offense was "especially

16/ (continued)

White v. State, 403 So.2d 331, 337-38 (Fla. 1981); Welty

v. State, 402 So.2d 1159, 1164 (Fla. 1981); Zeigler v.

State, 402 So.2d 365, 376 (Fla. 1981); Williams v .

State, supra, 386 So.2d at 541, 543; Clark v. State, 379

So.2d 97, 107 (Fla. 1979); Washington v. State, 362

So.2d 658, 665-66 (Fla. 1978); Meeks v. State, 339 So.2d

186, 190 (Fla. 1976); Meeks v. State, 336 So.2d 1142,

1143 (Fla. 1976). In six of the cases, the defendant

killed a police officer, apparently to avoid arrest for

another offense. Tafero v. State, 403 So.2d 355, 362

(Fla. 1981); Jacobs v. State, 396 So.2d 713, 715-16,

(Fla. 1981); Holmes v. State, 374 So.2d 944, 945-46

(Fla. 1979); Ford v. State, supra, 374 So.2d at 497;

Songer v. State, 365 So.2d 696, 698-99 n.2 (Fla. 1978);

Raulerson v. State, 358 So.2d 826, 828 (Fla. 1978). In

three cases the victim was a police informant, or slated

to be a witness in a judicial proceeding against the

defendant or his associates. Bolender v. State,

So.2d ____, 1982 Fla. Law Wkly, SCO 490 (No. 59,333)

(Oct. 28, 1982); White v. State, 415 So.2d 719, 720 n.2

(Fla. 1982); Antone v. State, 382 So.2d 1205, 1208-09

(Fla. 1980). The remaining two cases are those of

Barclay and Dougan, where the circumstance was based on

the defendants' "call for revolution."

The Florida Supreme Court has often questioned the

applicability of the "hinder law enforcement" aggravat

ing circumstance to a particular case because of doubts

whether the evidence was adequate to show that the de

fendant killed the victim to avoid arrest, rather than

for some other reason. It has never vacated a finding

of "hinder law enforcement," however, except to correct

its use as an additional factor when the reasons for

applying it were counted separately against the defend

ant under the "avoid arrest" aggravating circumstance,

Fla. Stat. §921.141 (5)(e).

53

heinous, atrocious or cruel," Fla. Stat.

§921.1 41(5)(h)) because the Florida Supreme

Court has made so many contradictory state

ments about it that no clear standards

emerge.~/ The dissenting justices in Dougan

17/ The "especially heinous, atrocious or cruel"

aggravating circumstance has generated a welter of

unintelligible law. The Florida Supreme Court has

vacated many findings of "especially heinous, atrocious

or cruel", but it has also approved the finding in

circumstances which seem factually indistinguishable.

The narrowing construction given §921.141(5)(h) in

State v, Dixon, 283 So.2d 1, 9 (Fla. 1973), and approved

by this Court in Proffitt v. Florida, supra, 428 U.S. at

255-56, does not seem to have assisted in ensuring a