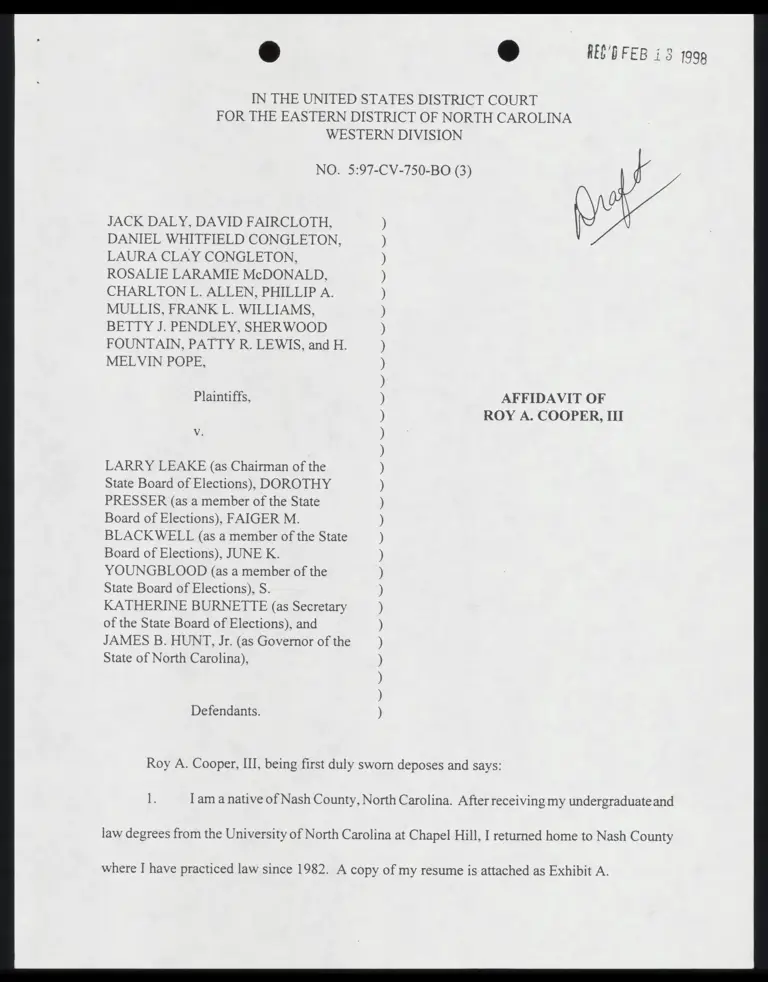

Draft Affidavit of Roy A. Cooper, III

Working File

February, 1998

9 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Draft Affidavit of Roy A. Cooper, III, 1998. 641c4616-da0e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dce85926-e6d6-43cd-a4ee-86cecebbbe56/draft-affidavit-of-roy-a-cooper-iii. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

® » REC'GFEB 13 1998

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

WESTERN DIVISION

NO. 5:97-CV-750-BO (3)

JACK DALY, DAVID FAIRCLOTH,

DANIEL WHITFIELD CONGLETON,

LAURA CLAY CONGLETON,

ROSALIE LARAMIE McDONALD,

CHARLTON L. ALLEN, PHILLIP A.

MULLIS, FRANK L. WILLIAMS,

BETTY J. PENDLEY, SHERWOOD

FOUNTAIN, PATTY R. LEWIS, and H.

MELVIN POPE,

AFFIDAVIT OF

ROY A. COOPER, III

Plaintiffs,

Vv.

LARRY LEAKE (as Chairman of the

State Board of Elections), DOROTHY

PRESSER (as a member of the State

Board of Elections), FAIGER M.

BLACKWELL (as a member of the State

Board of Elections), JUNE K.

YOUNGBLOOD (as a member of the

State Board of Elections), S.

KATHERINE BURNETTE (as Secretary

of the State Board of Elections), and

JAMES B. HUNT, Jr. (as Governor of the

State of North Carolina),

S

a

r

t

w

i

e

Du

ar

”

a

w

w

u

t

v

n

S

s

S

t

Sv

at

N

n

e

r

t

w

t

S

u

t

S

o

t

!

S

i

a

t

t

S

i

l

.

N

a

l

a

t

N

a

i

e

N

i

N

a

N

w

.

S

e

a

.

N

a

e

N

l

.

N

a

?

N

a

t

Defendants.

Roy A. Cooper, III, being first duly sworn deposes and says:

1, I am a native of Nash County, North Carolina. After receiving my undergraduateand

law degrees from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I returned home to Nash County

where I have practiced law since 1982. A copy of my resume is attached as Exhibit A.

® »

2. In 1986, 1988 and 1990, I was elected to the North Carolina House of Representatives

and in 1992, 1994 and 1996 I was elected to the North Carolina Senate. During the 1996 Session

of the General Assembly, I served as Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee and the Senate

Select Committee on Congressional Redistricting.

3. My responsibility as Chairman of the Senate Redistricting Committee was to attempt

to develop a new congressional plan that would cure the constitutional defects in the prior plan, and

that would have the support of a majority of the members of the Senate, which was controlled by the

Democrats, and the support of a majority of the members of the House, which was controlled by the

Republicans. Under an order entered by the three-judge court in Shaw v. Hunt the new plan had to

be completed by March 31, 1997, to avoid the federal court imposing a plan on the State. The

Senate’s efforts to meet this responsibility are recorded in the transcripts of the meetings of the

Senate Committee and of the debates on the floor of the Senate. A true and accurate copy of these

transcripts is attached as Exhibit B.

4. Representative W. Edwin McMahan was appointed Chairman of the House

Redistricting Committee by Speaker Brubaker. His responsibilities were essentially identical to

mine.

. Many people doubted that the General Assembly would be able to achieve a

compromise between the Democratic controlled Senate and Republican controlled House

Redistricting generally is a task which becomes extremely partisan. Working with the leadership

of the Senate and the House, however. Representative McMahan and I early on identified a single

path by which a compromise might be reached and a new plan adopted. This path was to craft a plan

which would cure the defects in the old plan and at the same time preserve the existing partisan

2

balance in the State’s congressional delegation. The Senate Redistricting Committee made the first

attempt to travel down this path. Gerry Cohen, Director of Legislative Drafting, was assigned to

work with me and to draw plans under my direction and supervision.

6. On February 20, 1997, after consultation with other Senate members, | presented a

proposed plan, entitled Congressional Plan A (hereinafter Plan A), to the Senate Redistricting

Committee. This plan was similar to alternative plans later proposed by the House Redistricting

Committee and Representative McMahan and to the plan ultimately enacted by the General

Assembly. Because Plan A turned out to be the prototype for the enacted plan, I will describe the

goals the Senate leadership and I wanted to achieve in designing this plan. In addition, I will

describe the process used to draw the districts in Plan A to achieve those goals. Particular attention

will be given to Districts 1 and 12.

7. We had three goals for the plan as a whole. The first goal was to cure the

constitutional defects in the prior plan by assuring that race was not the predominate factor in

constructing any district in the plan and to assure that traditional redistricting criteria were not

subordinated to race. To accomplish this first goal. emphasis was placed on the following factors

in constructing the plan: (1) avoidance of division of precincts; (2) avoidance of the division of

counties when reasonably possible: (3) functional compactness (grouping together citizens of like

interests and needs); (4) avoidance of long narrow corridors connecting concentrations of minority

citizens; and (5) ease of communication among voters and their representatives. A comparison of

the unconstitutional 1992 plan and Plan A demonstrates that this goal was accomplished. For

example: (1) the unconstitutional plan divided 80 precincts while Plan A divided only 2 precincts

(both of which were divided only to accommodate peculiar local circumstances); (2) the

3

unconstitutional plan divided 43 counties while Plan A divided only 24; (3) the unconstitutional plan

divided 7 counties among 3 districts while Plan A did not divide any county among 3 districts; (4)

the unconstitutional plan used “cross-overs,” “double cross-overs” and “points of contiguity” to

create contiguous districts while Plan A used none of these devices.

8. Our second goal was to assure that Plan A complied with one-person, one-vole

requirements. Plan A met this requirement.

9, Our third goal, and the goal that made it possible for the General Assembly to agree

upon and enact a new plan, was to maintain the existing partisan balance in the State’s congressional

delegation, 6 Republicansand 6 Democrats. Based on my discussions with Senate leaders and with

Representative McMahan, I knew that any plan which gave an advantage to Democrats faced certain

defeat in the House while any plan which gave an advantage to Republicans faced certain defeat in

the Senate. Preserving the existing partisan balance, therefore, was the only means by which the

General Assembly could enact a plan as required by the Court. To achieve this pivotal goal, we

designed Plan A to preserve the partisan core of the existing districts to the extent reasonably

possible and to avoid pitting incumbents against each another. One tool I used to measure the

partisan nature of districts was election results gathered and analyzed by the National Committee for

an Effective Congress (NCEC). The NCEC information was based on the results of a series of

elections from 1990 to 1996. I also used to some extent older election results contained in the

legislative computer data base. In the end. these election results were the principal factor which

determined the location and configuration of all districts in Plan A so that a partisan balance which

could pass the General Assembly could be achieved.

10. The three goals we applied in drawing the plan as a whole were also applied in

drawing Districts 1 and 12. To assure that race did not predominate over traditional redistricting

criteria, District 12 was drawn so that (1) only 1 precinct was divided (a precinct in Mecklenburg

County that was divided in every local districting plan); (2) its length was reduced by 46% from 191

miles to 102 miles) so that it became the third shortest district in the state; (3) the number of counties

included in the district was reduced from 10 to 6; (4) all “cross-overs,” “double cross-overs” and

“points of contiguity” were eliminated; and (5) it was a functionally compact, highly urban district

joining together citizens in Charlotte and the cities of the Piedmont Urban Triad. To assure that race

did not predominate over traditional redistricting criteria, District 1 was drawn so that (1) no

precincts were split; (2) the number of counties included in the district was reduced from 28 to 20;

(3) the number of divided counties included in the district was reduced from 18 to 10; (4) all “cross-

overs,” “double cross-overs” and “points of contiguity” were eliminated; (5) the length of the district

was reduced by 24% (from 225 miles to 171 miles); and (6) it was a functionally compact district

joining together citizens in most rural and mostly economically depressed counties in the northern

and central Coastal Plain region of the State.

1}: Maintaining Districts 1 and 12 as Democratic leaning districts was critical to

solic the pivotal goal of protecting the partisan balance in the State’s congressional plan.

Achieving this goal for Districts 1 and 12. however, presented special problems. First, the House

insisted that District 1 had to be drawn in a manner that protected Congressman Jones in District 3

and that avoided placing Congressman Jones’ residence inside the boundaries of District 1. Second,

District 12 had to be drawn in a manner that avoided placing Congressman Burr’s and Coble’s

residences inside the boundaries of District 12. Third, District 12 had to be drawn in a manner that

would not include Cabarrus County, Congressman Hefner's home county. Fourth, significant

portions of Congressman Watt’s and Congresswoman Clayton’s former districts had been eliminated

because of the directive in Shaw v. Hunt, thus lessening their strength as incumbents. Finally, we

were concerned that Congressman Watt might lose some votes because of his race and that

Congresswoman Clayton almost certainly would lose votes because of her race. To help protect

District 1 as a Democratic leaning district, we included the heavy concentrations of Democratic

voters in the cities of Rocky Mount, Greenville, Goldsboro, Wilson and Kinston, and to help protect

District 12 as a Democrat leaning district, we included the heavy concentrations of Democratic

voters in Charlotte, Greensboro and Winston-Salem in the district.

12. In developing Congressional Plan A, I also became convinced from expert studies

before the General Assembly and my own knowledge and experience that Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act likely required the creation of a majority-minority district in the control to northern part

of the Coastal Plain. That belief, along with my primary goals of curing the defects in our prior plan

and protecting the executing partisan balance in the C ongressional delegation, guided me in locating

and drawing District 1 in Congressional Plan A.

13. On February 20, 1997, I presented Congressional Plan A to the Senate Redistricting

Committee and on February 25, 1997, Representative McMahan presented his first plan,

Congressional Plan A.1, to the House Redistricting Committee. Congressional Plan A and A.1 were

similar. Based on NCEC electionresults, however, I was concerned that Representative McMahan’s

Plan unnecessarily diminished Democratic performance in Districts 2, 8 and 12, Congressmen

Hefner’s, Etheridge’s and Watt's districts.

14. Over the next several weeks Representative McMahan and [ were able to resolve my

concerns and the condoms of the Senate leadership by negotiation. The compromise we reached

finally was reflected in a alin entitled “97 House/Senate Plan.” This is the plan that was enacted by

the General Assembly on March 31, 1997. The first plan, “Congressional Plan A,” and “97

House/Senate Plan,” the enacted plan are very similar. Perhaps the biggest difference is that the first

plan had 24 divided counties while the enacted plan reduced the number of divided counties to 22.

13, In their complaint, plaintiffs allege that “97 House/Senate Plan” is an

unconstitutional racial gerrymander. They are wrong. “97 House/Senate Plan” is a negotiated

bipartisan plan which contains districts located and shaped in a manner to avoid constitutional

problems and to protect the existing partisan balance in the State’s Congressional delegation. Racial

fairness was, of course, considered in the development of the plan. Our obligations to represent all

of our constituents of all races and to comply with the Voting Rights Act demanded that racial

fairness be considered. The plan enacted is racially fair, but race for the sake of race was not the

dominate or controlling factor in the development or enactment of the plan.

16. To support their allegations, plaintiffs point to the fact that a large proportion of the

predominantly black precincts in the counties in which District 12 is located in “97 House/Senate

Plan” are assigned to District 12 and that a large proportion of the predominantly white precincts in

the counties in which District 12 is located are assigned to other districts. Their effort to paint a

political compromise as a racial gerrymander is unfounded. In drawing initially Congressional Plan

A and in negotiating the eventually enacted plan, partisan election data, not race, was the

predominant basis for assigning precincts to districts including precincts in Districts 1 and 12. That

a large proportion of precincts assigned to District 12 have significant black populations is simply

7

the result of strong Democratic voting pattern among blacks in general. Moreover, District 12 is not

even composed of a majority of black citizens; it is a district in which white citizens constitute 52%

of the district’s total population, 55% of the distrief} oting age population and 54% of the districty

registered voters. Simply, District 12 is a Democratic island in a largely Republican sea.

17. Plaintiffs also allege in their complaint: “the primary reason the district (District 12)

does not contain a majority of blacks is that Democrat state Senator Roy Cooper, an attorney and

Chairman of the Senate Congressional Redistricting Committee, erroneously advised his fellow

Senators and Republicans on more than one occasion that the original 12th congressional district had

been deemed unconstitutional because it was majority black, and that the legislature could legally

gerrymander along racial lines so long as it did not produce a district in which blacks comprised an

“absolute majority.” Comp. § 58. I have never advised my colleagues that it was legal to

gerrymander along racial lines so long as it did not produce a district in which blacks compromised

an absolute majority. To the contrary, I have advised my colleagues that the Constitution forbids

legislative bodies from using race as the predominate factor in the drawing of electoral districts. I

have told my colleagues that in making a determination as to met racial gerrymandering has

occurred, the Court would look at the common interests or needs of the district. I have told them the

Court also would look at the shape of the districts and whether land bridges were used to connect

citizens who don’t have these common interests. In addition, I told my colleagues that the Court

naturally would look at the racial composition of a district to determine whether a racial gerrymander

exists and the fact that the new District 12 did not have a majority of black citizens was a significant

factor in determining whether racial gerrymandering had occurred.

This the day of January, 1998.

Roy A. Cooper, Jr.

Sworn to and subscribed before me this

day of January, 1998.

Notary Public

My commission expires: