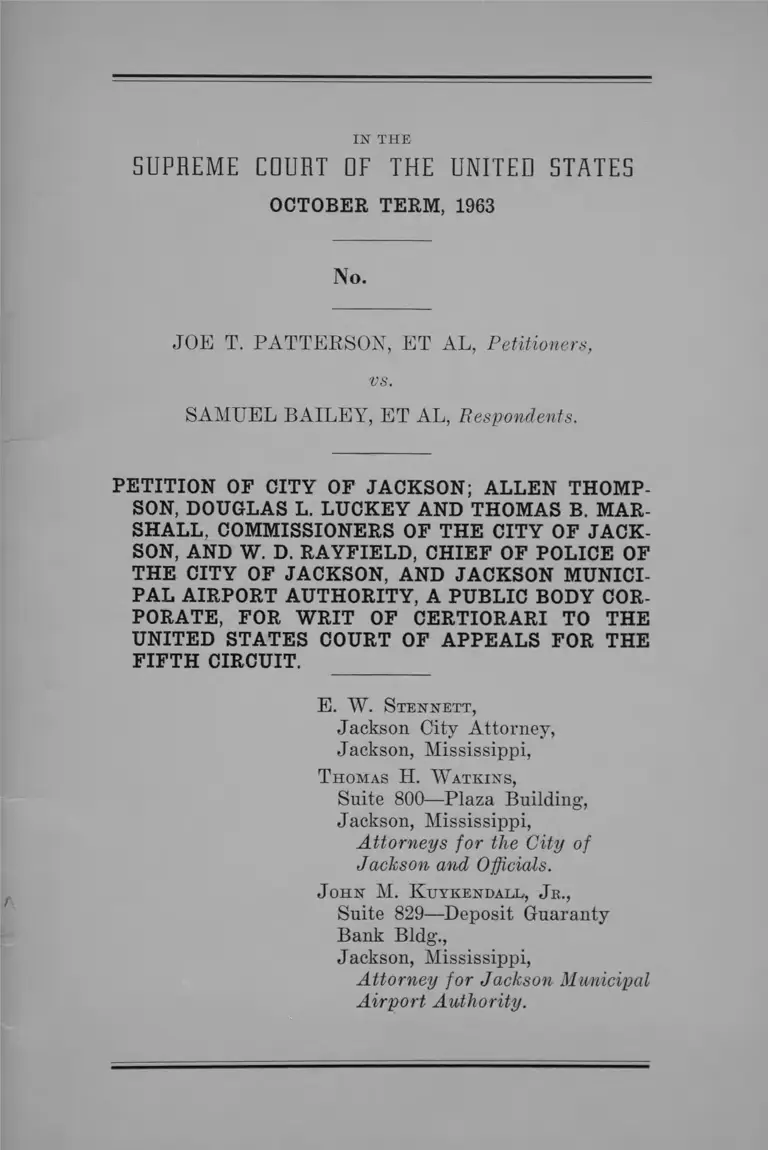

Patterson v. Bailey Petition of City of Jackson

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. Bailey Petition of City of Jackson, 1963. 3c6757e3-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dd48f241-e269-491c-9ff1-9751445850c0/patterson-v-bailey-petition-of-city-of-jackson. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

S U P R E M E EO U R T DF T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1963

No.

JOE T. PATTERSON, ET AL, Petitioners,

vs.

SAMUEL BAILEY, ET AL, Respondents.

PETITION OF CITY OF JACKSON; ALLEN THOMP

SON, DOUGLAS L. LUCKEY AND THOMAS B. MAR

SHALL, COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY OF JACK-

SON, AND W. D. RAYFIELD, CHIEF OF POLICE OF

THE CITY OF JACKSON, AND JACKSON MUNICI

PAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY, A PUBLIC BODY COR

PORATE, FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT.

E . W . S t e n n e t t ,

Jackson City Attorney,

Jackson, Mississippi,

T h o m a s H. W a t k in s ,

Suite 800—Plaza Building,

Jackson, Mississippi,

Attorneys for the City of

Jackson and Officials.

J o h n M. K tjyk en dalh , J k .,

Suite 829—Deposit Guaranty

Bank Bldg.,

Jackson, Mississippi,

Attorney for Jackson Municipal

Airport Authority.

INDEX

Page

Jurisdiction and Opinions Below................................ 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................. 3

Questions Presented..................................................... 4

Statement ...................................................................... 5

Reasons for Allowance of W rit.................................... 10

1. The ruling of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit that this was a proper class

action and that Respondents were entitled to class

relief is in direct conflict with decisions of this

Court and in direct conflict with prior decisions of

the Circuit Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit

and in direct conflict with prior decisions of other

Courts of Appeal in other Circuits........................ 10

2. The holding of the Court of Appeals of the Fifth

Circuit that Respondents for themselves and/or

for the class were entitled to injunctive relief

under the facts and circumstances here is in direct

conflict with decisions of this Court and of the

Courts of Appeal of other circuits and with prior

decisions of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. . 22

(a) A Court will not enjoin the enforcement of

state criminal statutes, even if unconstitu

tional, unless the same have been enforced

against petitioner or petitioner is threatened

with enforcement thereof and he is in clear

and imminent danger of immediate arrest

thereunder ........................................................ 23

(b) The refusal of injunctive relief was within the

discretion of the trial judge which was not

abused ................................................................ 24

(c) An injunction should only issue with great

caution and only in exceptional circumstances

to prevent immediate irreparable injury. . . . 25

(d) The Court cannot enjoin the future enforce

ment of constitutional breach of the peace

statutes .............................................................. 26

—9492-0

11 INDEX

(e) The denial of injunctive relief against the Mu

nicipal Airport Authority by the Trial Judge

was peculiarly within his discretion................. 30

3. Even if any relief should have been granted

against the City officials, which is denied, no in

junctive relief should have been granted against

the City of Jackson and the Municipal Airport

Authority ................................................................ 31

Conclusion .................................................................... 32

Cases:

American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 90 L.ed.

873, 327 U.S. 582....................................................... 23,26

Anderson v. Kelly, 32 F.R.D. 355................................. 12

Bailey v. Patterson, 368 U.S. 347, 7 L.ed.2d 332. . . . 12

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31, 7 L.ed.2d 512......... 12

Bailey v. Patterson, 7 L.ed.2d 332, 368 U.S. 346. . . . 23

Barnes v. City of Gadsden, C.A. 5, 174 F.Supp. 64,

affirmed 268 F.2d 593, cert. den. 4 L.ed.2d 186 . . . . 24

Bates v. Batte, C.A. 5, 187 F.2d 142, cert. den. 96 L.

Ed. 616, 342 U.S. 815............................................... 18

Beal v. Missouri Pacific R. Corp., 312 U.S. 45, 85 L.ed.

577 ............................................................................. 25,26

Bowles v. Huff, C.A. 9', 146 F.2d 428........................ 24

Bradford v. Hurt, C.A. 5, 84 F.2d 722...................... 23, 30

Brotherhood v. Missouri-Kansas-T. R. Co., 4 L.ed.2d

1379, 363 U.S. 528..................................................... 24

Brown v. Board of Trustees, 187 F.2d 20................. 15

Brown v. Ramsey, C.A. 8, 185 F.2d 225..................... 12

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, C.A. 5, 308

F.2d 491, 503.............................................................. 17

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, E.D.La., 138

F.Supp. 337................................................................ 17

Carroll v. Associated Musicians of Greater New York,

C.A. 2, 316 F.2d 574................................................... 12

Carson v. Warlick, C.A. 4, 238 F.2d 724, cert. den. 353

U.S. 910, 1 L.Ed. 2d 664........................................... 17

Casey v. Plummer, 353 U.S. 924, 1 L.ed.2d 719. . . . 16

Page

Page

Charlton v. Hialeah, C.A. 5, 188 F.2d 421................. 32

City of Montgomery v. Gilmore, C.A. 5, 277 F.2d 364 16, 20

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, 27 L.ed. 836............. 19

Clark v. Thompson, 206 F.Supp. 535, affirmed 313

F.2d 637; petition for certiorari denied December

16, 1963................................................................... 15, 24, 25

Cohen v. Public Housing Administration, C.A. 5, 257

F.2d 73....................................................................... 20

Coleman v. Miller, 307 U.S. 433, 83 L.ed. 1385......... 21

Collins v. Texas, 223 IJ.S. 288, 56 L.ed. 439............. 21

Conley v. Gibson, 29 F.R.D. 519.................................. 12

Cook v. Davis, C.A. 5, 178 F.2d 595............................ 18

Covington v. Edwards, C.A. 4, 264 F.2d 780, cert. den.

4 L.Ed.2d 79, 361 IJ.S. 840....................................... 18

Davis <& F. Mfg. Co. v. Los Angeles, 189 U.S. 207, 47

L.ed. 778, 23 S. Ct. 498........................................... 28

Dawley v. City of Norfolk, 159 F.Supp. 642, affirmed

260 F.2d 647, C.A. 4, Certiorari denied, 3 L.ed.2d

636, 359 U.S. 935....................................................12,25,26

Denny v. Bush, 367 U.S. 908, 81 S.Ct. 1917, 6 L.Ed.2d

1249 ....................................................................................17

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F.2d 922, certiorari

denied sub nom........................................................ 16

Douglas v. Jeamnette, 319 U.S. 157, 87 L.ed. 1324. . . . 27, 29

Empire Pictures Distributing Company v. City of

Fort Worth, C.A. 5, 273 F.2d 529.......................... 23,29

Erie Railroad v. Williams, 233 U.S. 68, 58 L.ed 1155 21

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U.S. 202, 3 L.ed.2d 222, 79 S Ct

178 ............................................................................. 13,14

Fenner v. Boykin, 271 U.S. 240, 70 L.ed. 927, 46 S. Ct.

492 ............................................................................. 28

First National Bank v. Albright, 52 L.ed. 614, 208 U.S.

548 ............................................................................. 24

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337, 83 L.ed. 208............... 19

Gremillion v. U.S., 368 U.S. 11, 82 S.Ct. 119, 7 L.Ed.

2d 75........................................................................... 17

Haynes v. Shuttlesworth, 310 F.2d 303....................... 16

Hecht Company v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321, 88 L.ed. 754 24

INDEX 111

IV INDEX

Hewitt v. Jacksonville, C.A. 5, 188 F.2d 423............. 32

Hickey v. Illinois Central Rairoad, C.A. 7, 278 F.2d

529 ....................................................... ................... 12

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, C.A. 5, 258

F.2d 730...................................................................... 20

Holt v. Raleigh City Board, C.A. 4, 265 F.2d 95, cert.

den. 4 L.Ed.2d 63, 361 U.S. 818.............................. 18

Jeffrey Manufacturing Company v. Blagg, 235 U.S.

571, 59 L.ed. 364. ...................................................... 21

Johnson v. Crawfis, 128 F.Supp. 230.......................... 12

Johnson v. Stevenson, C.A. 5, 170 F.2d 108, cert. den.

93 L.End. 359, 335 U.S. 801...................................... 18

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Com, v. McGrath, 95 L.ed.

817, 341 U.S. 123...................................................... 20

Kansas City v. Williams, C.A. 8, 205 F.2d 47. 12,25

M. & 0. R.R. Co. v. State, 153 U.S. 486, 38 L.ed. 793 20

Matthews v. Rodgers, 284 U.S. 529, 530, 76 L.ed. 454,

455, 52 S. Ct. 217...................................................... 28

McCabe v. Atchison, 59 L.ed. 169, 235 U.S. 151. . . 11,14,15

McGhee v. Sipes, 92 L.ed. 1161, 34 U.S. 1 ...... 19

McKissick v. Durham City Board, 176 F. Supp. 3. . . . 18

Mitchell v. United States, 313 LT.S. 80, 93, 85 L.ed.

1201, 1210, 61 S Ct 873............................................ 13

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 5 L.ed.2d 492............. 32

Oivnbey v. Morgan, 65 L.ed. 837, 256 U.S. 94........... 20

Parham v. Dove, C.A. 8, 271 F.2d 132........................ 17

Peay v. Cox, C.A. 5, 190 F.2d 123, cert. den. 96 L.ed

671 .............................................................................. 18,24

Poe v. Ullman, 6 L.ed.2d 512, 367 U.S. 497................. 23

Potts v. Flax, C.A. 5, 313 F.2d 284, affirming 204 F.

Supp. 458.................................................................... 17,18

PUmmer v. Casey, 148 F.Supp. 326 sub nom......... 16

Redlands Foothill Groves v. Jacobs, 30 F.Supp. 995 24

Redlands v. Jacobs, 30 F.Supp. 995............................. 26

Reliable Transfer v. Blanchard, C.A. 5, 145 F.2d 551 25

Rock Drilling, Blasting, etc. v. Mason <& Hanger Co.,

C.A. 2, 217 F.2d 687....................................' ............ 12

School Board v. Allen, C.A. 4, 240 F.2d 59............. 20

Page

IHDEX V

Shelley v. Kraemer, 92 L.ed. 1161, 34 U.S. 1 ............. 19

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board, 162 F.Supp.

372, affirmed per curiam 3 L.ed.2d 145, 358 U.S. 101 19-20

Shuttlesworth v. Gaylord, 202 F.Supp. 59, affirmed

sub iiom ...................................................................... 16

Spielman Motor Sales v. Dodge, 79 L.ed. 1322, 295

U.S. 89....................................................................... 23,25

Stefanelli v. Minyard, 96 L.ed. 138, 342 U.S. 117. . . . 23, 30

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378, 77 L.ed. 375. . . 25,26

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 94 L.ed. 1114......... 19

Tennessee Electric Power v. Tennessee Valley, 306

U.S. 118, 83 L.ed. 543............................................... 21

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 105, 60 S. Ct. 736, 84

L.Ed. 1093.................................................................. 30

Tileston v. Ullman, 318 U.S. 44, 87 L.ed. 603............. 21

Toomer v. Witsel, 334 U.S. 385, 92 L.ed. 1460, 93

L.ed. 389...................................................................... 21

Troup v. McCart, C.A. 5, 238 F.2d 289..................... 15

Turner v. Memphis, 7 L.ed.2d 762, 369 U.S. 350. . . . 14

U.S. v. Grant, 346 U.S. 629, 97 L.ed. 1303................. 31

United Electrical Workers v. Baldwin, 67 F.Supp.

235 ............................................................................. 30

United States v. City of Jackson, C.A. 5, 318 F.2d 1 6

Walling v. Buettner dc Co., C.A. 7, 133 F.2d 306. . . . 24

Watson v. Buck, 85 L.ed. 1416, 313 U.S. 387............. 23

Watson v. Buck, 313 U.S. 387, 85 L.ed. 1460............. 30

Wilson v. Schnettler, 365 U.S. 381, 5 L.ed.2d 620. . . . 30

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. 1343(3)....................................................... 1

28 U.S.C. 2281............................................................. 1

28 U.S.C. 2284............................................................. 1,2

42 U.S.C. 1983............................................................. 2

28 U.S.C. 1253............................................................. 2

28 U.S.C. 1343(3).......................................................... 32

42 U.S.C. 1983.............................................................. 32

204 F.Supp. at 460...................................................... 18

313 F.2d at 288............................................................ 18

Page

VI INDEX

Sections 7545-32............................................................ 9

Sections 2087.5, 2087.7, 2089.5.................................... 6

Rule 23( i ) ...................................................................... 2

138 F.Supp. 33.............................................................. 17

204 F.Supp. 568, affirmed 308 F.2d 491, 503............. 17

369 U.S. 31, 7 L.ed.2d 512........................................... 13

Statutes of the State of Mississippi, Sections 2351,

2351.5, 2351.7, 7784, 7785, 7786, 7786-01................. 5-6

Rule 23 of the Rules of Federal Practice................. 21

Miscellaneous:

Fourteenth Amendment.............................................. 2,19,20

Opinion, 199 F. Supp. 595.......................................... 2

Opinion, 368 U.S. 346, 7 L.ed.2d 332........................ 2

District Court, 369 U.S. 31, 7 L.ed.2d 512............. 2

Opinion, Fifth Circuit, 323 F.2d 201........................ 3, 6, 21

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1254(1)......... 3

Civil Rights A ct............................................................ 32

Fifth Circuit, 369 U.S. 31, 7 L.ed.2d 512................... 13

Page

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit ..................................... 1, 3,12,13,15,16, 21, 22, 31,32

IN' THE

S U P R E M E EO U R T DF T H E U N I T E D STAT ES

OCTOBER TERM, 1963

N o .

JOE T. PATTERSON, ET AL, Petitioners,

vs.

SAMUEL BAILEY, ET AL, Respondents.

PETITION OF CITY OF JACKSON; ALLEN THOMP

SON, DOUGLAS L. LUCKEY AND THOMAS B. MAR

SHALL, COMMISSIONERS OF THE CITY OF JACK-

SON, AND W. D. RAYFIELD, CHIEF OF POLICE OF

THE CITY OF JACKSON, AND JACKSON MUNICI

PAL AIRPORT AUTHORITY, A PUBLIC BODY COR

PORATE, FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT.

Petitioners, some of the Appellees in the Court below,

pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review the judgment

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit entered on September 24th, 1963, followed by the Order

of said Court denying a Petition for Rehearing entered on

November 8th, 1963.

Jurisdiction and Opinions Below

The basis for the jurisdiction of the courts below was

2 8 U.8.C. 1 3 4 3 (3 ) , 28 U.S.C. 2281 and 28 U.8.C. 2284 , the

Complaint further alleging that the action was authorized (l)

(l)

2

by 42 U.S.C. 1983 , the action being one for alleged depriva

tion of rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States. A Three-Judge Court was

organized under 2 8 U.S.C. 2284.

An Order of the Three-Judge Court retaining juris

diction but staying further proceedings awaiting State

Court actions or decisions was entered November 17th,

1961 (R. 705). A copy thereof is submitted as Appendix

“ A ” .1 A copy of the Opinion of the Three-Judge Court

(R, 630), reported 199 F. Supp. 595, is submitted as Ap

pendix “ B ” . A copy of the Dissenting Opinion (R. 667)

is submitted as Appendix “ C” .

An appeal was taken to this Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

1253 (R. 706). Pending the appeal a Motion was filed

in this Court for an injunction to stay the prosecution of

criminal cases in the Courts of Mississippi. The Motion

for injunctive relief pendente lite was denied by this Court

on December 18th, 1961, the Opinion being reported in

368 U.S. 346, 7 L.ed.2d 332. A copy thereof is submitted

as Appendix “ D ” .

On the appeal to this Court the Judgment of the Three-

Judge Court was vacated, this Court holding that the

Three-Judge Court was unnecessary, and the cause was

remanded to the District Court by decision of February

26th, 1962, reported 369 U.S. 31, 7 L.ed.2d 512. Copy

thereof is submitted as Appendix “ E ” .

The District Court of the United States for the Southern

District of Mississippi, Jackson Division, entered a Find

ings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Declaratory Judg

ment on May 3rd, 1962 (R. 732). The Opinion and Declara

tory Judgment is not published and a copy thereof is sub

mitted as Appendix “ F ” . 1

1 Appendices, because voluminous, are separately printed and presented

herewith under Rule 23(i).

3

An oral amendment to the Findings of Fact was made

by the District Judge on May 31st, 1962 (R. 843-5), not

published, and a copy thereof is submitted as Appen

dix “ G” .

On July 25th, 1962, the District Court entered Supple

mental Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Declara

tory Judgment (R. 785), not published. A copy thereof

is submitted as Appendix “ H ” .

On August 24th, 1962, there was entered in the District

Court below an Order sustaining in part and overruling

in part Plaintiff’s Motion that the Court amend its Sup

plemental Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and De

claratory Judgment (R. 846). It has not been published

and a copy thereof is submitted as Appendix “ J ” . The

Opinion of the Court which formed the basis thereof, also

dated August 24th, 1962, is in letter form (R. 850) and

unpublished. A copy thereof is submitted as Appen

dix “ I ” .

The Decision of the District Court for the Southern

District of Mississippi, Jackson Division, was reversed

by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals on September 24th,

1963. The Opinion is reported in 323 F.2d 201. Copy of

the Opinion is submitted as Appendix “ K ” . Copy of

the Judgment of said Court is submitted as Appendix “ L ” .

A Petition for Rehearing was denied by the Court of

Appeals of the Fifth Circuit without opinion on Novem

ber 8th, 1963. Copy of the Order is submitted as Appen

dix “ M ” .

The Order of the Court below staying the mandate for

sixty days, dated November 15th, 1963, is submitted as

Appendix “ N ” .

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1254(1).

4’

Questions Presented

The specific questions presented are:

1. Whether the three Respondents, Samuel Bailey,

Joseph Broadwater and Burnett L. Jacob, have any right

to maintain a class action on behalf of other Negroes

when they themselves have admittedly not been discrimi

nated against on account of their race by Petitioners and

have not been deprived by them of any rights under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and where

they are thus not members of the class for which relief

was sought.

2. Whether under the facts of this case Respondents,

although personally entitled to non-discriminatory use of

transportation facilities, which they obtained by Declara

tory Judgment in the District Court, were entitled to injunc

tive relief either personally or for a class against enforce

ment of Segregation Statutes of the State of Mississippi

or Ordinances of the City of Jackson.

3. Whether under the facts of this case Respondents,

although personally entitled to non-discriminatory use of

transportation facilities which they obtained by Declaratory

Judgment in the District Court, were personally or for a

class entitled to broad sweeping injunctive relief against

any policy, practice, custom or usage of segregation of

transportation facilities by Petitioners allegedly under

color of the “ Breach of the Peace” statutes of the State of

Mississippi.

4. Whether Respondents were entitled in this Civil Rights

action to any injunctive relief against the City of Jackson

or the Jackson Municipal Airport Authority, a public body

corporate.

The serious underlying questions involved include: (1)

Whether or not our established jurisprudence applicable

5

to injunctive relief and class suits is now totally inappli

cable in civil rights cases; (2) Whether a city by injunc

tion against all of its law enforcement officers can be for

bidden to prevent disorderly conduct and breaches of the

peace where a Negro is involved on penalty of its right

to so do in individual instances being triable in a Federal

Court in Contempt of Court proceedings with the risk

of criminal punishment for a possible error of judgment

on the part of the police officers. The necessity for local

police control during racial demonstrations has been amply

demonstrated; and (3) Whether an individual Negro has a

personal right under the Fourteenth Amendment not only

to the use of any public facility he desires but whether he

also has a constitutional right to the use of completely inte

grated facilities.

Statement

Three individual Negroes, Respondents here, filed a Com

plaint in the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Mississippi, Jackson Division, on behalf of all

other Negroes similarly situated, against the Attorney Gen

eral of the State of Mississippi; the City of Jackson and

the Mayor and Commissioners thereof and the Chief of

Police thereof; the Jackson Municipal Airport Authority;

the Continental Southern Lines; Southern Greyhound

Lines; Illinois Central Railroad; Jackson City Lines; and

Cicero Carr, operator of a restaurant at the Jackson Munic

ipal Airport.

Respondents alleged that Negroes had been deprived of

rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States by the Defendants below and

sought both preliminary and permanent injunctions against

said Defendants enjoining them from:

(A) Enforcing certain Segregation Statutes of the State

of Mississippi, i.e. Sections 2351, 2351.5, 2351.7, 7784, 7785,

6

7786, 7786-01, copies of which are separately submitted as

Appendix “ 0 ” , together with a 1956 Ordinance of the City

of Jackson, copy of which is submitted as Appendix “ P ” .

It was alleged that said Statutes require segregation of

facilities of carriers and that they violated the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution.

(B) Enforcing any policy, practice, and custom ana

usage of segregating passengers of any facility of a public

carrier and any policy, custom or usage of liarrassing or

intimidating Negroes in the exercise of their Federally pro

tected right to use interstate and intrastate transportation

facilities and services without discrimination or segrega

tion, the Complaint alleging that Defendants in so doing

were acting under color of the “ Breach of the Peace”

Statutes of Mississippi, i.e. Section 2087.5, 2087.7 and 2089.5,

copies of which are submitted as Appendix “ Q” herewith.

(C) Posting or permitted to be posted signs designating

separate facilities in or on any terminal or sidewalk sur

rounding the same.

The Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit acting through

Circuit Judges Wisdom and Hayes, Circuit Judge Cameron

dissenting, granted injunctive relief “ as prayed for”

against all the carriers. None of the carriers have joined

in this Petition for Writ of Certiorari. The injunctive re

lief “ as prayed fo r” was granted against those Petitioners

insofar as persons using any facilities of the Jackson Munic

ipal Airport Authority or the buses of the bus company

Defendants were concerned.2 323 F.2d 201; Appendix “ K ”

submitted herewith.

2 Question of injunctive relief against the City and its officials for

enforcing or encouraging racial segregation in the use of terminal facilities

of the carriers, except the Jackson City Bus Line and the Municipal A ir

port Authority, having, the court stated, been eliminated by the decision

in United States V. City o f Jackson, C.A. 5, 318 F.2d 1, brought by the

7

None of the carriers being Petitioners here, a large por

tion of the evidence in the record is eliminated. There is

here involved none of the alleged acts of any of the car

riers, including the Jackson City Lines, in maintaining any

racial signs or enforcing or encouraging any racial segre

gation in their terminals or facilities. Also any testimony

as to any incidents occurring outside of the City of Jack-

son are eliminated, i.e. any incidents not involving officials

of the City of Jackson or the Municipal Airport Authority.

That there was no ground for any class action was

frankly and freely admitted by Respondents themselves.

Each of these three claimants testified that they had never

been arrested under any of the statutes or under the ordi

nance complained of, nor had they been threatened with or

in danger of any arrest under such statutes or ordinance.

They went further and testified that they themselves had

never been deprived of or denied the indiscriminate use

of any facility of any Defendant. They also admitted that

they had not consulted with any other members of the

class they purported to represent before the action was

brought and that they knew that all members of the alleged

class did not approve of their action or did not agree with

the position being taken by them in the action. (Broad

water, R. 109-11; Jacob, R. 120-22; Bailey, R. 140-42)

Not only did Respondents, Plaintiffs below, admit that

they themselves had never been arrested under any of the

“ Segregation Statutes” , but no other witness testified that

he had ever been arrested under any of these statutes or

the City Ordinance complained of or been threatened with

any arrest thereunder and the undisputed testimony of the

City officials was that they had never arrested or threatened

United States of America under the Interstate Commerce Commission Act.

Also eliminated was the question o f racial signs maintained by the City

o f Jackson surrounding terminals, which had been removed as a result of

said decision.

arrest of anyone under these statutes (E. 348, 354-6, 359).

The unconstitutionality of these statutes was thoroughly

recognized by city officials and there was no suggestion of

any intent on the part of the City to attempt to enforce

such unconstitutional statutes. The Mayor testified that

the City had no objection to Negroes using any facility of

any carrier where peace and quiet could be maintained and

there would be no disturbances (E. 355).

The issue of the existence of the City signs on side

walks surrounding terminals being removed and eliminated,

the only evidence against the City or its officials dealt with

arrests of Freedom Eiders under the “ Breach of the

Peace” statutes. Unquestionably, there were a substantial

number of arrests of these Freedom Eiders occurring after

April, 1961, when the Freedom Eiders made their much

publicized invasion of Mississippi, all such arrests being-

made under the Breach of the Peace Statutes. The dis

orders and breaches of the peace and disturbances caused

by these same Freedom Eiders in Alabama and the fact that

they were coming into Mississippi to create the same dis

turbances had become public knowledge in the State of

Mississippi (E. 492-507, 507-513, 516-519). Due objection

was made to the evidence of these arrests in this cause on

the ground that it was a collateral attack on criminal ac

tions pending in the State court (E. 474, et seq). These

cases are still pending in the State Courts and several of

them have now been submitted to the Supreme Court of the

State of Mississippi and a decision may be reached therein

at any time.3

In each instance of such arrest for breaches of the peace

sufficient crowds had congregated under such circumstances

as to indicate to local officials probable breaches of the

3 I f such a decision is handed down prior to a decision on this Petition,

copies o f the opinions will be submitted as a supplement hereto.

9

peace. The police officers in their opinion were convinced

in each instance that there would have been trouble and

there would have been a breach of the peace had the police

not taken action. Such action prevented any serious dis

turbances in Mississippi. In each instance the police, be

fore any arrest, ordered the crowds or groups dispersed.

In each instance only those who refused to obey the order

of the police to disperse or move on were arrested. In

each instance in arrests of the Freedom Riders both white

and colored were arrested at the same time, i.e. all were

arrested who refused to move on at the order of the offi

cers at a time when and under circumstances such that

a breach of the peace could be occasioned by the failure of

the crowd to obey the orders of the police (R. 370-6, 378-9,

381-2, 386-8, 444-49, 454-56, 459-46, 185-6, 261-71).

However, we again point out that none of the Respond

ents were among the groups so arrested under the “ Breach

of the Peace” statutes or even in the crowd at the time

or observed any such arrest.

As to the Municipal Airport Authority, a separate statu

tory authority created by Sections 7545-32, et seq. of the

Code pertinent portions of which are submitted as Ap

pendix “ R ” hereto: The proof showed that there had been

racially discriminatory signs in the airport terminal. How

ever, prior to the final decree of the Court below and on

June 4th, 1962, these signs had all been removed from the

airport (R. 770). None of the Segregation Statutes were

applicable to the airport. The Airport Authority had no

jurisdiction over the enforcement of law or arrests in the

airport, a City policeman being assigned to the airport

and the policeman not taking orders from the Authority.

'There was no evidence of any arrests in the airport and

none had been reported to the Authority. The Authority

had no policy of discrimination. True, the airport restau-

io

rant, operated by Cicero Carr, bad been segregated by

this lessee of the Airport Authority over whom the Air

port Authority had no control. However, when Carr re

fused to conform to the Decree of the District Court to

discontinue such discrimination and before the final order

in the District Court, the Authority terminated Carr’s

lease and filed an affidavit to the effect that in the future

the Authority itself would operate the restaurant and would

operate it without discrimination (R. 810-11).

Again Respondents admittedly had been subjected to

no such discrimination themselves and had not been de

prived of any use of any airport facility.

The District Court made a Finding of Fact and Law

that this was not a proper class action and that no relief

could be granted other than that to which the Respondents

were personally entitled. The Court and adjudged that

each of the three! plaintiffs had a right to unsegregated

use of any transportation facility and were given relief

by way of declaratory judgment. The Court held how

ever the Plaintiffs were not entitled to any injunctive

relief but jurisdiction was retained for the entry of fur

ther orders and relief as might be subsequently appropriate

(R. 740, Appendices F, G, H, I and J).

Reasons for Allowance of Writ

1. The ruling of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit that this was a proper class action and

that Respondents ivere entitled to class relief is in direct

conflict with decisions of this Court and in direct conflict

with prior decisions of the Circuit Court of Appeals of

the Fifth Circuit and in direct conflict with prior decisions

of other Courts of Appeal in other Circuits.

The decision of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit in this case is in direct conflict with the decision

11

of this Court in McCabe v. Atchison, 59 L.ed. 169, 235 U.S.

151. There an action was brought by a few Negroes for

a class injunction against railroad carriers to prevent

them from complying in any way with a State separate-

coach law. There the Complainants had never requested

the Defendants for accommodations in any sleeping cars,

dining cars or chair cars and Complainants had never

been notified by the Defendants that they would not be

furnished to them, when furnished to others, upon reason

able request and payment of the customary charge. Com

plainants had thus never been refused accommodations

equal to those afforded to those of the white race. The

injunction was sought to be justified on the ground of

avoiding a multiplicity of suits, the Complaint alleging

“ . . . there being at least ‘ fifty thousand persons of the

Negro race in the State of Oklahoma’ who will be in

jured and deprived of their civil rights ’ ’. The lower Court

dismissed the Bill and this Court, in affirming the lower

Court’s decree, stated:

“ . . . The Complainant cannot succeed because

someone else may be hurt. Nor does it make any dif

ference that other persons who may be injured are

persons of the same race or occupation. It is the fact,

clearly established, of injury to the Complainant—not

to others, which justifies judicial intervention . . . The

desire to obtain a sweeping injunction cannot be ac

cepted as a substitute for compliance with the general

rule that the complainant must present facts sufficient

to show that his individual need requires the remedy

for which he asks. The bill is wholly destitute of any

sufficient ground for injunction, and unless we are to

to ignore settled principles governing equitable relief,

the decree must be affirmed,”

12

The decision of the Court below is in direct conflict with

Dawley v. City of Norfolk, 159 F.Supp. 642, affirmed 260

F.2d 647, C.A. 4, Certiorari denied, 3 L.ed.2d 636, 359 U.S.

935. There an action was brought by a Negro attorney for

a mandatory injunction requiring the City to remove the

word “ colored” from doors of certain restrooms in a

courthouse building occupied by State Courts and Judges.

The Court held that this relief could not be secured by

plaintiff. The District Court Judge pointed out: “ There

had been no threats or orders to plaintiff with respect to

using the rest rooms in the state courthouse building.”

The decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit is in direct conflict with decisions of other

Federal Courts of other Circuits holding that a party can

not obtain injunctive relief on behalf of a class where he

is not a member of the class in that he has not been per

sonally discriminated against or deprived of rights sought

to be obtained for others or actually suffered any wrongs

sought to be remedied in the litigation on behalf of the

class. These Decisions include: Kansas City v. Williams,

C.A. 8, 205 F.2d 47; Hickey v. Illinois Central Railroad,

C.A. 7, 278, F.2d 529; Rock Drilling, Blasting, etc. v. Mason

& Hanger Co., C.A. 2, 217 F.2d 687; Carroll v. Associated

Musicians of Greater New York, C.A. 2, 316 F.2d 574;

Brown v. Ramsey, C.A. 8, 185 F.2d 225. See also: Johnson

v. Cranvfis, 128 F.Supp. 230; Anderson v. Kelly, 32 F.R.D.

355; Conley v. Gibson, 29 F.R.D. 519.

The decision of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit in this case is, we submit, in direct conflict with prior

decision of this Court in this case, i.e. Bailey v. Patterson,

368 U.S. 347, 7 L.ed.2d 332, and Bailey v. Patterson, 369

U.S. 31, 7 L.ed.2d 512. In the first opinion on a Motion

for an injunction pendente lite to stay the prosecution of

a number of criminal cases in Mississippi Courts, the Court

13

denied relief on the primary ground that there was no

justification for the extraordinary remedy and two con

curring justices, Mr. Justice Black and Mr. Justice Frank

furter, also pointed out that: “ The three movants are not

themselves being prosecuted or threatened with prosecu

tion in Mississippi . . . ”

In the second decision, in overruling the Order of the

Three-Judge Court that the case he delayed pending a

State construction of the statutes involved, 369 U.S. 31,

7 L.ed.2d 512, this Court held that the Respondents lacked

standing to enjoin prosecutions under the Mississippi

Breach of the Peace Statutes in that “ They cannot repre

sent a class of whom they are not a part” .

After the remand of this case after these decisions no

additional evidence was offered with reference to any dis

crimination against the Respondents or any matters or

things making them a member of the class for whom they

sought relief. This case stands before this Court on this

issue on exactly the same facts that existed at the time of

the prior decisions.

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit apparently

misconstrues one sentence in the decision of this Court in

369 U.S. 31, 7 L.ed.2d 512. This Court merely stated: “ But

as passengers using the segregated transportation facili

ties they are aggrieved parties and have standing to en

force their rights to nonsegregated treatment. Mitchell v.

United States, 313 U.S. 80, 93, 85 L.ed. 1201, 1210, 61 S Ct

873; Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U.S. 202, 3 L.ed.2d 222, 79 S Ct

178.” This Court was clearly only referring to Respond

ents having a standing to enforce their personal rights,

not class rights. True, Mitchell v. U.S., supra, and Evers

v. Dwyer, supra, were class suits. But in each of those

cases the passenger seeking rights was actually a member

of the class. For example, in Mitchell v. U.S., supra, the

14

action was brought by a Negro who was himself put off

of the pullman into a coach on crossing a state line by an

employee of the carrier. The employee in so doing was

admittedly engaged in enforcing a State statute. Or, for

example, in Evers v. Dwyer, supra, the Plaintiff himself

was ordered to move to the rear of a Memphis bus because

of his color and upon his refusal two police officers entered

the bus and ordered him to go to the back of the bus or get

off and on this order he left the bus.

This Court therefore clearly used these cases as an illus

tration of the personal rights of Respondents because they

were public transportation facility cases and in so using

them this Court at the same time clearly stated that Re

spondents “ cannot represent a class of whom they are

not a part. McCabe v. Atchison, T d S. F. R. Co., 235 U.S.

151, 162, 163, 59 L.ed. 169. . .” This Court did no more

than remand the case for disposition by the District Court

“ of the appellants’ claims of right to unsegregated trans

portation service” i.e. referring to their personal rights.

It did not hold that they were entitled to class relief.

Note the difference between the order in the prior appeal

of this case, supra, and in the order of this Court in the

case of Turner v. Memphis, 7 L.ed.2d 762, 369 U.S. 350.

There the plaintiff was “ a Negro who was refused non-

segregated service in the Memphis Municipal Airport res

taurant” and who brought the action for himself and other

Negroes similarly situated. There the plaintiff was a mem

ber of the class and the order of this Court read: “ . . . The

case is remanded to the district court with directions to

enter a decree granting appropriate injunctive relief against

the discrimination complained.” Here there was no order

of this Court remanding the case for class relief or for in

junctive relief but merely for appropriate personal relief

15

after the Court had pointed out that Respondents were not

entitled to class relief.

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit frankly admits

that the decision in this case is in conflict with prior deci

sions of that Court, pointing out that it was in conflict with

Clark v. Thompson, 206 F.Supp. 535, affirmed 313 F.2d

637. Petition for Certiorari denied December 16,1963. The

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit adopting the opinion

of the District Court which used the following language:

“ None of the plaintiffs has been arrested or threat

ened with arrest under any statute or alleged dis

criminatory practice attacked in this case. The plain

tiffs have not been denied any right, privilege or im

munity claimed by them by any of the defendants . . .

There is no evidence that they have been denied the

right to use any public recreational facility in that

city . . . This is not a proper class action, and no re

lief may be granted other than that to which the plain

tiffs are personally entitled . . . The plaintiffs cannot

make this a legitimate class action by merely calling

it such . . . Class action cannot be maintained where

the interests of the plaintiffs . . . are not wholly com

patible with the interests of those whom they purport

to represent4. . .”

The decision here is also in conflict with another decision

of the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit, i.e. Brown v.

Board of Trustees, 187, F.2d 20, where the Court cited with

approval McCabe v. Atchison, supra, and pointed out:

“ . . . it is elementary that he has no standing to sue for the

deprivation of the civil rights of others.” The Court there

also pointed out: “ A suit to supervise and control by in

4 Even in a class suit claimant’s interest must be wholly compatible with

that of the class. Troup v. McCarty C.A. 5, 238 F.2d 289.

16

junction the general conduct of a political subdivision of the

state, this suit has for its purpose, not the mere according

of a specific right which has been denied, but the establish

ment of a sort of general government by injunction over the

school district in respect of its schools and school system

. . . Such an injunction . . . will not usually he granted.”

We submit that the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit

in the opinion here is in error in saying the decisions of that

Court are divided on this question in that there is no Fifth

Circuit decision authorizing a class suit under the cir

cumstances here.

In support of that position the Court of Appeals of the

Fifth Circuit refers to Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F.2d

922, certiorari denied sub nom Casey v. Plummer, 353 U.S.

924, 1 L.ed.2d 719. The facts in that case are stated in the

District Court opinion in 148 F.Supp. 326 sub nom Plummer

v. Casey where the Court pointed out: “ Plaintiffs contend

. . . that they are and have been routinely excluded from

the court house cafeteria solely by reason of their race and

color specifically, plaintiffs allege that they were excluded

on August 27th, 1953, when they sought to buy and consume

food upon the premises.” The case was clearly a proper

class action.

The Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit then refers to

Shuttlesworth v. Gaylord, 202 F.Supp. 59, affirmed sub nom

Haynes v. Shuttlesworth, 310 F.2d 303, based on a prior de

cision of that Court in City of Montgomery, Alabama v.

Gilmore, 277 F.2d 364. In both of those cases the defendant

city was unquestionably enforcing under state statutes and

city ordinances complete segregation of municipal facili

ties. The specific question of the right to maintain a

class action was not raised. However, in each of those

cases the plaintiffs themselves had filed a petition with

the city authorities seeking as Negroes personal permission

to use the facilities and had been refused such right. Here

17

the respondents freely admitted that they had never been

denied any right to do anything they wanted to do (R. 110-

11, 122, 142).

The Court below has sought to justify its decision on

the basis of desegregation of schools cases citing Potts

v. Flax, C.A. 5, 313 F.2d 284, in turn citing Bush v. Orleans

Parish School Board, C.A. 5, 308 F.2d 491, 503. These

cases were proper class suits.

The case of Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, C.A.

5, 308 F.2d 491, affirming 204 F. Supp. 568, is merely a

final step in a long series of decisions.5 The litigation was

brought by a group of minor Negro plaintiffs and all

Negroes similarly situated seeking desegregation of the

schools of Orleans Parish, Louisiana. The opinion in 138

F. Supp. 33 pointed out that the plaintiffs “ have petitioned

the Board on three separate occasions asking that their

children be assigned to nonsegregated schools.” This had

been refused these plaintiffs. Desegregation orders were

entered. By the time of the decision in 204 F. Supp. 568,

which was affirmd 308 F.2d 491, 503, a hundred and one

additional intervenors were before the Court. It was a

proper class action.

A Negro child can neither individually nor of course

for a class obtain relief in the desegregation of schools

until they have personally exhausted their administrative

remedy and been denied attendance in a white school, i.e.

actually been personally deprived of their rights. Parham

v. Dove, C.A. 8, 271 F.2d 132; Carson v. Warticle, C.A. 4,

5 For the prior history of this litigation, see Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, E.D.La., 138 F.Supp. 337, affirmed, 5 Cir., 242 1.2d 156;

id., 163 F.Supp. 701, affirmed, 5 Cir., 268 F.2d 78; id., 187 F.Supp. 42,

affirmed, 365 U.S. 569, 81 S.Ct. 754, 5 L.Ed.2d 806; id., 188 F.Supp. 916,

affirmed, 365 U.S. 569, 81 S.Ct. 754, 5 L.Ed.2d 806; id., 190 F.Supp. 861,

affirmed, 365 U.S. 569, 81 S.Ct. 754, 5 L.Ed.2d 806; id., 191 F.Supp. 871,

affirmed, Denny V. Bush, 367 U.S. 908, 81 S.Ct. 1917, 6 L.Ed.2d 1249;

id., 194 F.Supp. 182, affirmed, Gremillion v. V.S., 368 U.S. 11, 82 S.Ct,

119, 7 L.Ed.Zd 75.

18

238 F.2d 724, cert. den. 353 U.S. 910, 1 L.Ed. 2d 664;

Covington v. Edwards, C.A. 4, 264 F.2d 780, cert. den. 4

L.Ed.2d 79, 361 U.S. 840; Holt v. Baleigh City Board, C.A.

4, 265 F.2d 95, cert. den. 4 L.Ed.2d 63, 361 U.S. 818;

McKissick v. Durham, City Board, 176 F. Supp. 3. See

Johnson v. Stevenson, C.A. 5, 170 F.2d 108, cert. den. 93

L.Ed. 359, 335 U.S. 801; Peay v. Cox, C.A 5, 190 F.2d 123;

Bates v. Batte, C.A 5, 187 F.2d 142, cert. den. 96 L. Ed.

616, 342 U.S. 815, following Cook v. Davis, C.A. 5, 178

F.2d 595.

Similarly, in Potts v. Flax, C.A. 5, 313 F.2d 284, affirming

204 F.Supp. 458, suit was brought by six Negro children

of Herbert Teal and one Negro child of Flax. The Court

pointed out: “ . . . the children named in the complaint

were refused enrollment at the school nearest their re

spective homes solely on the ground of their race and

color.” 6 The decree granting class relief was not chal

lenged on the ground that plaintiffs were not members of

the class. It was merely challenged on the ground that

‘ ‘ such matters are not . . . determined on a class basis

since the Board ‘must register each child one at a time as

individuals,’ ” 7 i.e. the contention was made that there

could be no class action whatsoever in a school case. The

Court merely held: “ The pleaded reason for challenging

the class suit was, therefore, unfounded.”

The issue here was not presented in either of the above

cases and could not be presented because the plantiffs were

members of the class and actually discriminated against.

Any language therein, therefore, with reference to segre

gation in the schools being discrimination against “ a class

as a class” , which is “ appropriate for class relief” is

6 Quoting 204 F.Supp. at 460.

7 Quoting 313 F.2d at 288.

19

pure dicta insofar as the right of Respondents to bring

an action for a class is concerned.

In the present case the Court of Appeals has attempted

to take such, language out of context and thereby in reality

create a new constitutional right. That Court has said

that although Respondents sought class relief (and by the

judgment here are in reality granted class relief) it is

really not a class action in that plaintiffs “ seek the right

to use facilities which have been desegregated . . . ” No

other court has gone so far.

No such right is given by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution. This Amendment merely forbids any

state from depriving “ any person” of due process of law

or denying to “ any person” the equal protection of the

laws. The rights under the Fourteenth Amendment are

individual personal rights, not class rights. Shelley v.

Kraemer, 92 L.ed. 1161, 34 U.S. 1; McGhee v. Sipes, 92

L.ed. 1161, 34 U.S. 1; Siveatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 94

L.ed. 1114; Gaines v. Canada, 305 US. 337, 83 L.ed. 208.

The Constitution only protects against state action de

priving an individual of his “ life, liberty or property” .

A man is deprived of none of these merely because he

desires in his pursuit of happiness to live in a completely

integrated community. Congress cannot under the power

given it by the Fourteenth Amendment regulate “ all pri

vate rights between man and man in society” . Civil Rights

Cases, 109 U.S. 3, 27 L.ed. 836. The effect of such a theory

is that any one Negro although not himself deprived of

any of his rights of liberty or to equal protection of the

law could require or compel, even contrary to the wishes

of other Negroes, complete integration. And yet the Four

teenth Amendment merely prohibits state enforced segre

gation against an individual and dos not command inte

gration. Shuttleswortli v. Birmingham Board, 162 F.Supp.

2 0

372, affirmed per curiam 3 L.ed.2d 145, 358 U.S. 101;

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, C.A. 5, 258 F.2d

730; School Board v. Allen, C.A. 4, 240 F.2d 59; Cohen v.

Public Housing Administration, C.A. 5, 257 F.2d 73; City

of Montgomery v. Gilmore, C.A. 5, 277 F.2d 364, where

this same Court said: “ We can only call attention to the

limit of the pertinent constitutional provision as construed

by the Supreme Court, i.e. that it does not compel the

mixing of the different races in the public parks.”

If the law does not compel integration, how can an in

dividual compel complete integration? The acts of the

State must adversely affect the “ legal” interests of a

petitioner, not merely the personal interests. Separate

opinion of Judge Frankfurter, Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee

Com. v. McGrath, 95 L.ed. 817, 341 U.S. 123.

The Fourteenth Amendment itself grants no rights but

only protects against infringement of existing rights. “ Its

function is negative, not affirmative, and it carries no

mandate for particular measures of reform.” Ownbey v.

Morgan, 65 L.ed. 837, 256 U.S. 94. See also M. £ 0. R.R.

Co. v. State, 153 U.S. 486, 38 L.ed. 793 at pages 506 and 800.

A Negro has under the Fourteenth Amendment no right

to general desegregation. For example, he has a consti

tutional right not to be deprived of the right to serve on

a jury, but the Constitution gives him no right to require

that there be other Negroes on the jury. By whatever name

it was called the Court below was in the final analysis still

saying that Respondents had a right to protect the rights of

other Negroes although not deprived of their own rights.

The Constitution not requiring segregation and therefore

Respondents having no constitutional right to anything but

their own personal freedom from discrimination, the fact

that they may be aggrieved by or made unhappy by the

segregation of others does not allow such person to chal

lenge the constitutionality thereof.

21

For example, the case of Tileston v. Ullmcm, 318 U.S. 44,

87 L.ed. 603, a state statute prohibited giving of advice as

to the use of contraceptives. A physician was aggrieved

thereby in that the statute would prevent his giving pro

fessional advice to three patients whose condition of health

was such that their lives would be endangered by child

birth. The Court held that he had no standing to litigate

the constitutional question, the statute obviously depriving

his patients and not him of constitutional rights.

Or, for example, in Tennessee Electric Power v. Tennes

see Valley, 306 U.S. 118, 83 L.ed. 543, an unconstitutional

statutory grant of power to the Tennessee Valley Authority

to erect a series of dams on the Tennessee River and sell

the power created thereby resulted in competition to cer

tain public utility corporations. The Court held that al

though aggrieved at the result of the unconstitutional Act

the utilities could not attack the unconstitutionality thereof.

See also Collins v. Texas, 223 U.S. 288, 56 L.ed. 439;

Jeffrey Manufacturing Company v. Blagg, 235 U.S. 571, 59

L.ed. 364. See concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Frank

furter in Coleman v. Miller, 307 U.S. 433, 83 L.ed. 1385.

Erie Railroad v. Williams, 233 U.S. 68, 58 L.ed. 1155;

Toomer v. Witsel, 334 U.S. 385, 92 L.ed. 1460, 93 L.ed. 389.

The only time that any person has been allowed to attack

the constitutionality of a statute, except for the direct and

explicit purpose of redressing a wrong actually done him,

is in a class case. Class cases are a creature of equity and

have always been in our jurisprudence subject to the provi

sion that the plaintiff must be a member of the class. This

principle has been readopted in Rule 23 of the Rules of

Federal Practice. The allowance of a class suit here under

the circumstances of this case would be an instance of the

throwing of precedence and established legal principle out

of the window. If this decision is allowed to stand, then,

at least in the Fifth Circuit, any single Negro can require

2 2

the integration of an entire community although he

himself has not been in any way discriminated ag*ainst or

denied any rights or privileges under the Constitution and

even though as a matter of fact the actual members of the

class which he seeks to represent may not desire or ap

prove of the litigation.

2. The holding of the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Cir

cuit that Respondents for themselves and/or for the class

were entitled to injunctive relief under the facts and cir

cumstances here is in direct conflict with decisions of this

Court and of the Courts of Appeal of other circuits and with

prior decisions of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The imposing of an injunction against a defendant, and

particularly against public officials, is an extraordinary

remedy applied with great hesitancy and only under unusual

circumstances because of the stigma and the harsh penalties

attached thereto. The tendency of some federal courts in

civil rights actions to overlook this fact and ignore ap

plicable precedents and long established principles of

equity controlling injunctive relief should be curbed by this

Court. In some Circuits broad sweeping permanent in

junctions are becoming the rule not the exception and, we

submit, it behooves this Court to require that these estab

lished precedents and principles be as applicable in Civil

Eights actions as in other actions.

The facts of this case do not justify the granting of any

injunctive relief either to the Eespondents personally or for

a class, much less the granting of the broad sweeping class

injunctive relief against public officials. The granting of

the injunctive relief by the Circuit Court of Appeals of

the Fifth Circuit here was in conflict with all of the follow

ing well established principles.

23

(a)

A Court will not enjoin the enforcement of state criminal

statutes, even if unconstitutional, unless the same have

been enforced against petitioner or petitioner is threat

ened with enforcement thereof and he is in clear and

imminent danger of immediate arrest thereunder.

These Petitioners here were enjoined from enforcing

certain unconstitutional criminal statutes of the State of

Mississippi, including one Municipal Ordinance. The

Municipal Airport Authority had no authority to and did

not enforce any statutes. It was undisputed that the

officials of the City of Jackson had never enforced any of

the statutes complained of nor threatened the enforcement

thereof. Respondents position was that they did not need

to he actually arrested before obtaining injunctive relief.

While under unusual circumstances this is true, there can

be no injunctive relief unless Respondents were actually

threatened with enforcement of the criminal statutes and

were in clear and imminent danger of arrest thereunder.

Not only were these Respondents not threatened with any

arrest under the statute, but no arrest of anyone had ever

been made or threatened or contemplated.

Cases denying the right to injunctive relief under such

circumstances include: Poe v. Ulltnan, 6 L.ed.2d 512, 367

U.S. 497; Bailey v. Patterson, 7 L.ed.2d 332, 368 U.S. 346;

American Federation of Labor v. Watson, 90 L.ed. 873,

327 U.S. 582; Spielman Motor Sales v. Dodge, 79 L.ed. 1322,

295 U.S. 89; Stefcmelli v. Minyard, 96 L.ed. 138, 342 U.S.

117; Watson v. Buck, 85 L.ed. 1416, 313 U.S. 387; Bradford

v. Hurt, C.A. 5, 84 F.2d 722; Empire Pictures Distributing

Company v. City of Fort Worth, C.A. 5, 273 F.2d 529.

Equity will not grant an injunction because of the mere

apprehension or suspicion or fear that there might be a

24

need therefor. First National Bank v. Albright, 52 L.ed.

614, 208 U.S. 548; Walling v. Buettner & Co., C.A. 7, 133

F.2d 306; Redlands Foothill Groves v. Jacobs, 30 F.Supp.

995.

(b)

The refusal of injunctive relief was within the discretion

of the trial judge which was not abused.

The trial judge who exercised his discretion in refusing

injunctive relief in the District Court was the same trial

judge that denied injunctive relief against the same Peti

tioners, i.e. the City of Jackson and its officials, in the case

of Clark v. Thompson, 206 F.Supp. 539, affirmed by the

Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit 313 F.2d 637.

The Court in denying injunctive relief there specifically

held that in his opinion it was unnecessary and that the in

dividual defendants, the City officials, were “ all outstand

ing high-class gentlemen and in my opinion will not violate

the terms of the Declaratory Judgment issued herein . . .

They will conform to the ruling of this court without being-

coerced so to do by an injunction.” This finding by the

trial judge was affirmed by the Fifth Circuit Court of Ap

peals. It is applicable here.

Cases holding that the discretion exercised by a trial

judge in denying injunctive relief is reviewable only for

abuse of discretion and that under the facts here there was

no abuse of discretion particularly where the injunction

sought was to control state officers in the conduct of their

office who are presumed to obey the law, include: Brother

hood v. Missouri-Kansas-T. R. Co., 4 L.ed.2d 1379, 363 U.S.

528; Peay v. Cox, C.A. 5, 190 F.2d 123, cert. den. 96 L.ed.

671; Barnes v. City of Gadsden, C.A. 5, 174 F.Supp. 64,

affirmed 268 F.2d 593, cert. den. 4 L.ed.2d 186; Bowles v.

Huff, C.A. 9, 146 F.2d 428; Hecht Company v. Bowles, 321

25

U.S. 321, 88 L.ed. 754; Reliable Transfer v. Blanchard, C.A.

5, 145 F.2d 551; Spielman Motor Sales v. Dodge, 79 L.ed,

1322, 295 U.S. 89; Beal v. Missouri Pacific R. Corp., 312 U.S.

45, 85 L.ed. 577; Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U.S. 378, 77

L.ed. 375; Dawley v. City of Norfolk, C.A. 4, 159 F.Supp.

642, affirmed 260 F.2d 647, cert. den. 3 L.ed.2d 636; Kansas

City v. Williams, C.A. 8, 205 F.2d 47.

The trial judge in Clark v. Thompson, supra, in exer

cising his discretion denying injunctions against the officials

of the City of Jackson also stated that these officials knew

what the law was and what their obligations were and that

they would conform to the ruling of the Court. He then

stated: “ I am further of the opinion that during this period

of turmoil the time now has arrived when the judiciary

should not issue injunctions perfunctorily, but should place

trust in men of high character that they will obey the man

date of the court without any injunction hanging over

their heads ’ This statement leads us to :

(c)

An injunction should only issue with great caution and only

in exceptional circumstances to prevent immediate ir

reparable injury.

In Speilman Motor Sales v. Dodge, 79 L.ed. 1322, 295 U.S.

89, this Court stated:

“ To justify such interference (by injunction) there

must be exceptional circumstances and a clear showing

that an injunction is necessary in order to afford ade

quate protection of constitutional rights . . . The bill

contained general allegations of irreparable damage

and deprivation of ‘ rights, liberties, properties and im

munities’ without due process of law, if the statute

were enforced. But the bill failed to state facts suffi-

26

cient to warrant such conclusions, which alone were

not enough.”

See also D'awley v. City of Norfolk, 159 F.Supp. 642,

affirmed 260 F.2d 647, cert. den. 3 L.ed.2d 636; Beal v.

Missouri Pacific, 312 U.S. 45, 85 L.ed. 577; Sterling v.

Constantin, 287 U.S. 378, 77 L.ed. 375; Redlands v. Jacobs,

30 F.Supp. 995; American Federation of Labor v. Watson,

327 U.S. 582, 90 L.ed. 873.

(d)

The Court cannot enjoin the future enforcement of consti

tutional breach of the peace statutes.

The injunction here ordered by the Court of Appeals

was a broad sweeping injunction prohibiting Petitioners

from enforcing any policy, practice, custom or custom and

usage of segregating persons using transportation facili

ties under color of the Mississippi Breach of the Peace

Statutes.

There had, as reflected by this record, been a substantial

number of arrests by City officials under the Breach of

the Peace statutes. In each instance both white and colored

had been arrested and there had been no arrests when per

sons gathering in crowds did disperse upon order and no

arrests save where the police officers were of the honest and

firm conviction that a breach of the peace was imminent.

It is not alleged that these Breach of the Peace statutes

are unconstitutional and they are not unconstitutional on

their face (See Appendix “ Q” ), Whether or not they were

acutally in any one instance enforced so as to deprive any

particular person of his constitutional rights would depend

upon the special facts and circumstances of the individual

case, now pending in the State courts. They were never

enforced against Respondents or in their presence. Nor

were Respondents ever a member of any of the groups

27

ordered to move on. Persons so arrested are having their

day in court and will have an opportunity to appeal to this

court if they so desire. Whether or not there will be any

future arrests under this statute that might deprive any

particular individual of his constitutional rights will de

pend upon the facts and circumstances of the arrest, which

cannot he predicted. And yet the Court of Appeals of the

Fifth Circuit has issued a blanket injunction against these

Petitioners, public officials who would be presumed to do

their duty and obey the law which they understand, pre

venting them generally from enforcing in any way the

Breach of the Peace Statutes where a Negro was involved

under penalty of contempt of court proceedings.

In Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157, 87 L.ed. 1324, cer

tain members of Jehovah’s Witnesses had been arrested

for soliciting and distributing religious literature under a

municipal ordinance prohibiting solicitation without pro

curing a license from the City authorities. It was alleged

that the City officials threatened to continue to enforce the

ordinance by arrests and prosecution of any members of

the Jehovah Witness under this ordinance and plaintiff-

members, for all members of the Jehovah’s Witnesses,

sought an injunction to restrain the city officials from en

forcing this ordinance against the members of the Jehovah’s

Witnesses. The Court, in affirming the dismissal of the

petition, used the following language:

. Congress, by its legislation, has adopted the

policy, with certain well defined statutory exceptions,

of leaving generally to the state courts the trial of

criminal cases arising under state laws, subject to re

view by this Court of any federal questions involved.

Hence, courts of equity in the exercise of their dis

cretionary powers should conform to this policy by

refusing to interfere with or embarrass threatened pro

28

ceedings in state courts save in those exceptional cases

which call for the interposition of a court of equity to

prevent irreparable injury which is clear and im

minent; . . .

“ It is a familiar rule that courts of equity do not

ordinarily restrain criminal prosecutions. No person

is immune from prosecution in good faith for his

alleged criminal acts. Its imminence, even though al

leged to be in violation of constitutional guaranties,

is not a ground for equity relief since the lawfulness

or constitutionality of the statute or ordinance on which

the prosecution is based may be determined as readily

in the criminal case as in a suit for an injunction. Davis

& F. Mfg. Co. v. Los Angeles, 189 US 207, 47 L.ed.

778, 23 S Ct 498; Fenner v. Boykin, 271 US 240, 70

L.ed. 927, 46 S. Ct. 492___

# # #

. . It does not appear from the record that peti

tioners have been threatened with any injury other

than that incidental to every criminal proceeding

brought lawfully and in good faith, . . .

# * #

“ Nor is it enough to justify the exercise of the equity

jurisdiction in the circumstances of this case that there

are numerous members of a class threatened with

prosecution for violation of the ordinance. In general

the jurisdiction of equity to avoid multiplicity of civil

suits at law is restricted to those cases where there

would otherwise be some necessity for the maintenance

of numerous suits between the same parties involving

the same issues of law or fact. It does not ordinarily

extend to cases where there are numerous parties

and the issues between them and the adverse party—

here the state—are not necessarily identical. Matthews

29

V. Rodgers, supra (284 US 529, 530, 76 L.ed. 454, 455,

52 S Ct 217), and eases cited. Far less should

a federal court of equity attempt to envisage in advance

all the diverse issues which could engage the attention

of state courts in prosecutions of Jehovah’s Witnesses

for violations of the present ordinance, or assume to

draw to a federal court the determination of those is

sues in advance, hy a decree saying in what circum

stances and conditions the application of the city ordi

nance will be deemed to abridge freedom of speech and

religion.

# # #

“ For these reasons, establishing the want of equity

in the cause, we affirm the judgment of the circuit court

of appeals directing that the bill be dismissed.” (em

phasis ours)

The language in the last paragraph quoted from the

Douglas v. Jeannette case, supra, is particularly applicable

here. Here the issues between the City and the parties

arrested under the Breach of the Peace statutes are not

only not necessarily identical but would be different on

each occasion of a breach of the peace. A federal court of

equity could not attempt to envisage in advance all the

diverse issues of fact and law which could engage the at

tention of the state courts in prosecutions under the Breach

of Peace Statutes or assume to draw to a federal court the

determination of those issues in advance by a decree, in

effect saying that under no circumstances could the Breach

of the Peace Statutes be enforced against Negroes in or on

transportation facilities.8

8 Later cases expressing the reluctance of the federal courts to interfere

with the enforcement of criminal statutes by state or municipal authorities

and citing and relying on Douglas v. Jeannette, supra, include: Empire

30

We also call the attention of the Court to the language in

United Electrical Workers v. Baldwin, 67 F.Supp. 235, as

follows:

“ It does not appear that any federal right to utilize

a solid line of pickets blocking entrance to the plant

exists. Whether such an activity constitutes a hr each of

the peace under Connecticut law, it is not incumbent

upon this court to decide . . .

And the right of officials of the state to prevent

breaches of the peace cannot he denied. Thornhill v.

Alabama, supra, 310 U.S., at 105, 60 S. Ct. 736, 84

L. Ed. 1093. * * * In such situations we are all familiar

with the fact that the police often lay down rules which

temporarily interfere with one or another basic right.

To deny them the power to do so would be as much a

burdensome restraint on their duty to preserve the

peace, . . . ”

(emphasis ours)

See also Watson v. Buck, 313 U.S. 387, 85 L.ed. 1460.

(e)

The denial of injunctive relief against the Municipal Air

port Authority hy the Trial Judge was peculiarly within

his discretion.

The only matters and things proved against the Munici

pal Airport Authority were the presence of some racial

signs in the airport and racial discrimination by lessee in

the restaurant. Prior to the final decree in the District

Court all signs had been removed and the lease of the

Pictures Distributing Co. V. City of Ft. Worth, C.A. 5, 273 F.2d 529;

Stefanelli v. Minyard, 342 U.S. 117, 96 L.Ed. 138; Wilson v. Schnettler,

365 U.S. 381, 5 L.ed.2d 620. See also Bradford v. Hurt, C.A. 5, 84 F.2d

722.

31

restaurant to Cicero Carr had been cancelled and an affi

davit had been filed by the Municipal Airport Authority

to the effect that it would operate the restaurant itself

without segregation.

The Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit reversed the

refusal of the District Judge to enjoin the Municipal Air

port Authority in the face of U.8. v. Grant, 346 U.S. 629,

97 L.ed. 1303, where this Court in denying injunctive relief

after voluntary cessation of alleged illegal conduct by the

defendant stated:

“ But the moving party must satisfy the Court that

relief is needed. The pecessary determination is that

there exist some cognizable danger of recurrent vio

lation, something more than the mere possibility which

serves to keep the case alive. The Chancellor’s deci

sion is based on all the circumstances; his discretion is

necessarily broad and his strong showing of abuse must

be made to reverse it . . . The government must demon

strate that there was no reasonable basis for the Dis

trict Judge’s decision . . . How much contrition should

be expected of a defendant is hard for us to say. This

surely is a question better addressed to the discretion

of the trial court . . . We conclude that, although the

actions were not moot, no abuse of discretion has been

demonstrated in the trial court’s refusal to award in

junctive relief.”

3. Even if any relief should have been granted against

the City officials, which is denied, no injunctive relief should

have been grcmted against the City of Jackson and the

Municipal Airport Authority.

Both the City of Jackson and the Municipal Airport Au

thority are public bodies politic. They are not a person

under the Civil Bights Act.