Whitfield v. Clinton Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

August 27, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Whitfield v. Clinton Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1990. 8b8d0e11-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dd5fc546-2866-48e4-bf42-28ef4043a24f/whitfield-v-clinton-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

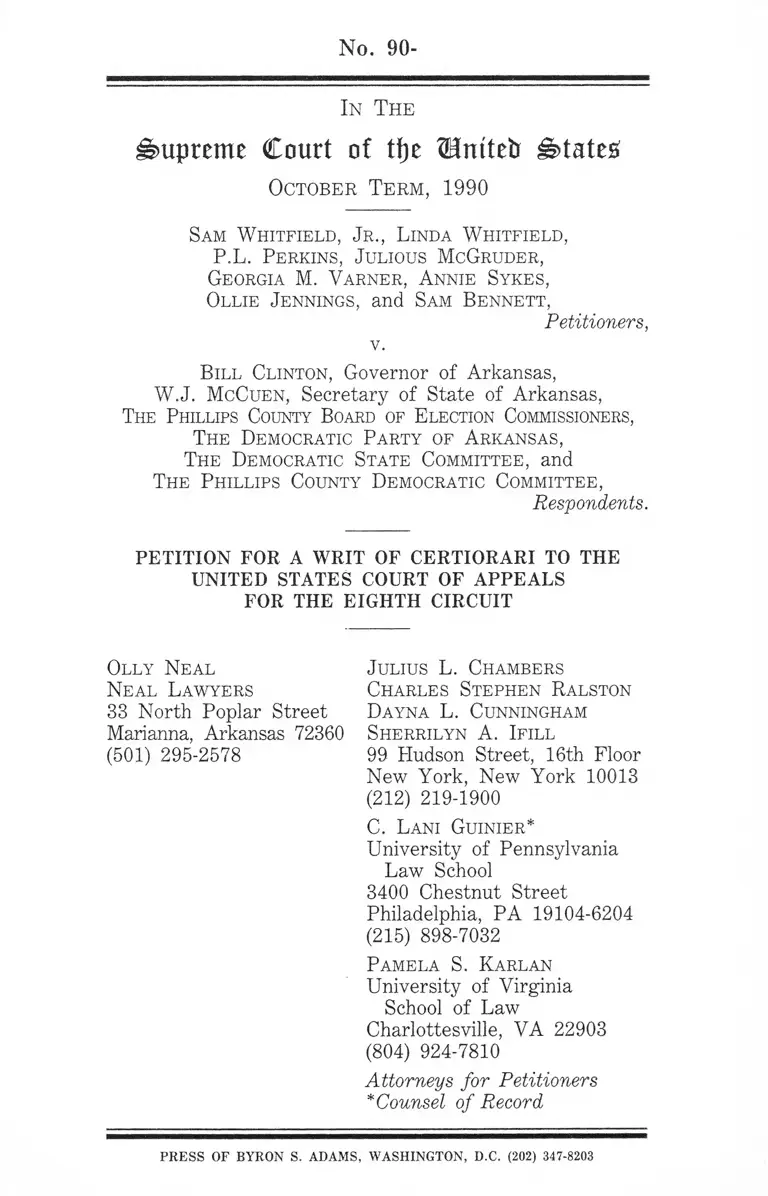

No. 90-

In Th e

Supreme Court of tfje ®mteti states

October Te r m , 1990

Sam Whitfield, J r ., Linda Whitfield,

P.L. Perkins, J ulious McGruder,

Georgia M. Varner, Annie Sykes,

Ollie Jennings, and Sam Bennett,

Petitioners,

v.

Bill Clinton, Governor of Arkansas,

W.J. M'cCuen, Secretary of State of Arkansas,

The Phillips County Board of Election Commissioners,

The Democratic Party of Arkansas,

The Democratic State Committee, and

The P hillips County Democratic Committee,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Olly Neal

Neal Lawyers

33 North Poplar Street

Marianna, Arkansas 72360

(501) 295-2578

J ulius L. Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Dayna L. Cunningham

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

C. Lani Guinier*

University of Pennsylvania

Law School

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104-6204

(215) 898-7032

P amela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22903

(804) 924-7810

Attorneys fo r Petitioners

* Counsel o f Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

Questions Presented

1. Does section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, prohibit the use of a runoff

primary requirement in a county where blacks constitute 47

percent of the voting-age population but where:

• black candidates who win the initial primary, are

always defeated in the runoff primary by the white candidate

who had originally finished behind them;

• black citizens were historically disenfranchised

on account of race or color;

• blacks continue to suffer disproportionately from

the legacy of past discrimination; and

• voting patterns are characterized by extreme

racial bloc voting?

2. Did the courts below err in creating a per se rule

that section 2 of the Voting Rights Act as amended does not

protect black voters if black citizens are a bare majority of

the total population within the relevant jurisdiction, even

when blacks are not a majority of the population of voting

age?

3. Are State executive branch officials, who certify

election results and otherwise administer state election laws,

proper parties defendant in a challenge to those state laws

under section 2 of the Voting Rights Act?

Ill

List of Parties

The names of all the parties to the proceedings below

appear in the caption.

Table of Contents

Page

Questions Presented . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . i

List of Parties . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii

Table of Contents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iv

Table of Authorities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vi

Opinions Below . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . l

Jurisdiction of this Court . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Statutes Involved . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Statement of the Case . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Introduction ....................................... 3

Statement o f Facts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

1. The runoff’s interaction with racial

bloc voting in Phillips County . . . . . . 10

2. The runoffs interaction with other

social and historical conditions in

Phillips County . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

3. The tenuousness o f the policy under

lying the use o f runoff primaries . . . . 21

Course o f the Proceedings Below . . . . . . . . . 25

V Page

Reasons for Granting the Writ . . . . . . . . . 29

I. This Court Should Grant Certiorari to

Provide the Lower Courts with Guidance

on How to Treat Section 2 Claims

Challenging Runoff Requirements . . . . 29

II. The Per Se Rule that Section 2 Does Not

Protect Black Voters if Blacks Constitute a

Majority of the Population (But Not a

Majority of the Voting-Age Population)

Announced in this Case Squarely Conflicts

with Decisions of this Court and the

Other Courts of Appeals . . . . . . . . . . . 35

A. This Court Has Rejected the Use

o f Per Se Rules in Section 2 Cases . . . 36

B. The Specific Per Se Rule Created in

this Case Conflicts with this Court’s

Decisions in White v. Regester and

Rogers v. Lodge and with Decisions of

the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits . . . . . 39

III. The Holding Below that the Governor and

Secretary of State are Not Proper

Defendants to a Statutory and Constitu

tional Challenge to a General Election

Runoff Statute Conflicts with Almost

Three Decades of this Court’s

Decisions .................. .. 42

Conclusion 49

VI

Table of Authorities

Page

Cases

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) . . . . . . . . .44-45

Butterworth v. Smith, 110 S.Ct. 1376 (1990) . . . .46-47

Butts v. City o f New York, 779 F.2d 141 (2d Cir.

1985), cert, denied, 478 U.S. 1021 (1986) . . 34

Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City o f Gretna,

834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987) . . . . . . . . . . 48

City o f Port Arthur v. United States, 459 U.S. 159

(1983) . . . . . . . . . . . . ........... . . . . . . . 31

City o f Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156

(1980) ........... .. 30-31

Eu v. San Francisco County Democratic Central

Committee, 109 S.Ct. 1013 (1989) . . . . . . . 47

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) . . . 46, 47

Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433 (1965) . . . . . . . 45

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704 (W.D. Tex 1972)

(three-judge court), ajf’d in relevant part and

rev’d in part on other grounds sub nom White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) . . . . . . . . . . 40

Hendrix v. McKinney, 460 F. Supp. 626 (M.D. Ala.

1978) . . . . . . . . ................. . . . . . . . . . . 48

INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983) . . . . . . . . 47

Jeffers v. Clinton, No. H-C-89-004 (E.D. Ark.

May 16, 1990) (three-judge court) . . . 5, 22-23, 42

McMillan v. Escambia County, 748 F.2d 1037 (11th

Cir. 1984) ................... 48

Monroe v. City ofWoodville, 819 F.2d 507 (5th Cir.

1987) . . . . . . . . .................... . . . . . . . . . 41

Perkins v. City of West Helena, 675 F.2d 201

(8th Cir), qffd, 459 U.S. 801 (1982) . . . . . .7, 21

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971) . . . . . . 20

Quinn v. Millsap, 109 S.Ct. 2324 (1989) . . . . . . 47

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) . . . . . . . 45

Rockefeller v. Matthews, 249 Ark. 341, 459

S.W.2d 110 (1970) ...................... 22

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) . . . 40, 45

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) . . . . . . 23

Smith v. Clinton, 687 F. Supp. 1310 (E.D. Ark.)

(three-judge court), aff’d, 109 S.Ct. 531 (1988) . . 8

Page

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 25 (1986) 4, passim

United States v. Board of Commissioners of

Sheffield, Alabama, 435 U.S. 110 (1978) . . . 31

United States v. Dallas County Commission, 850

F.2d 1430 (11th Cir. 1988) . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964) . . . . . . 45

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) . . . . . 45

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) . . 40, 45

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)

(en banc), aff’d on other grounds sub nom. East

Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424

U.S. 636 (1976) (per curiam) . . . . . . . . . . 41

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1331 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ........... .. 6

28 U.S.C. § 2201 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

28 U.S.C. § 2202 ..................................................... 6

Voting Rights Act of 1965 as amended, § 2,

42 U.S.C. § 1973 ........... .. 4, passim

viii

IX Page

Voting Rights Act of 1965 as amended, § 5,

42 U.S.C. § 1973c ........... .. 19, 20, 32

42 U.S.C. § 1973j(f) ........... .. 6

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-5-106 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-5-203 ........... .. 45

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-5-701 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-5-704 . ......................... 45

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-7-202 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Other Materials

28 C.F.R. § 51 (appendix) .............. .. ...................... 5

8th Cir. R. 16(a) ............................................... 28

Isikoff, U, S. Sues Georgia Over Voting Law:

Widespread Effect Seen if Requirement for

Runoffs is Overturned, Wash. Post, Aug. 10,

1990, at Al, col. 1 .................................... .. . 4

McDonald, The Majority Vote Requirement: Its

Use and Abuse in the South, 17 Urb. Law.

429 (1985) ................... ................ ...................... 5

X Page

S. Rep. No. 97-417 (1982) . . . . . . . . . . 4, passim

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting

Rights Act: Unfulfilled Goals (1981) . . . . . . 32

Voting Rights Act: Runoff Primaries and Registration

Barriers: Oversight Hearings Before the

Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional Rights of

the House Comm, on the Judiciary, 98th Cong.

2d Sess. (1984) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

No. 90-

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term 1990

Sam Whitfield, Jr ., Linda Whitfield,

P.L. Perkins, Julious McGruder,

Georgia M. Varner, Annie Sykes,

Ollie Jennings, and Sam Bennett,

Petitioners,

v.

Bill Clinton, Governor of Arkansas,

W.J. McCuen, Secretary of State of Arkansas,

The Phillips County Board of Election Commissioners,

The Democratic Party of Arkansas,

The Democratic State Committee, and

The Phillips County Democratic Committee,

Respondents.

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

Opinions Below

The opinion issued by the Court of Appeals sitting en

banc is reported at 902 F.2d 15, and is contained in the

2

Appendix at page la. The opinion of the Court of Appeals

panel is reported at 890 F.2d 1423, and is contained in the

Appendix at page 3a. The memorandum opinion of the

district court dismissing petitioners’ challenge to the primary

runoff statute is reported at 686 F. Supp. 1365, and is

contained in the Appendix at page 58a. The order of the

district court dismissing petitioners’ challenge to the general

election runoff statute and dismissing the Governor and

Secretary of State as party defendants is unreported; it and

relevant portions of the transcript of the district court’s oral

ruling are contained in the Appendix at page 132a.

Jurisdiction of this Court

The per curiam opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit upon rehearing en banc,

summarily affirming, by an equally divided court, the

decision of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Arkansas, was issued on May 4, 1990.

3

On July 26, 1990, Justice Blackmun entered an order

extending the time for filing a petition for writ of certiorari

to and including August 31, 1990.

This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Statutes Involved

This case involves the following statutes, which are set

out in the Appendix at page 171a:

• Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973

• Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-5-106

• Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-7-102

• Ark. Stat. Ann. § 7-7-202

Statement of the Case

Introduction

The Senate Report accompanying the 1982 amendments

4

to section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §

1973—which this Court has described as an "authoritative"

source for interpreting section 2, Thornburg v. Gingles, 478

U.S. 25, 43 n. 7 (1986)—expressly recognized that "majority

vote requirements . . . may enhance the opportunity for

discrimination against the minority." S. Rep. No. 97-417,

p. 29 (1982) [hereafter referred to as "Senate Report"].

Earlier this month, in announcing that the United States has

filed suit under section 2 to invalidate Georgia’s primary

runoff statute, Assistant Attorney General John Dunne, the

head of the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of

Justice, described majority-vote requirements as "an electoral

steroid for white candidates."1

In most states, a candidate wins an election or a party’s

nomination in a primary when he or she receives more votes

than any of his or her opponents. Arkansas is one of ten

hsikoff, U.S. Sues Georgia Over Voting Law: Widespread Effect

Seen i f Requirement fo r Runoffs is Overturned, Wash. Post, Aug. 10,

1990, at A l, col. 1.

5

states, all of them in the South, and all of them with a long

history of purposeful racial vote dilution, that do not follow

this general rule.2 Instead, under Arkansas law, a candidate

must receive a majority of the vote cast in a primary election

to obtain the nomination of a political party. Ark. Stat.

Ann. § 7-7-202. If no candidate wins an outright majority

of the votes cast in the first, or "preferential," primary than

a second, "general," runoff primary is held between the top

two vote getters two weeks later. Another statute, Ark. Stat.

Ann. § 7-5-106, requires that a candidate for municipal or

county office receive a majority of the vote cast to be

declared the winner of a general election. Again, if no

"The ten states are Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana,

Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, and Oklahoma. See

McDonald, The Majority Vote Requirement: Its TJse and Abuse in the

South, 17 Urb. Law. 429, 429 (1985). All of these states are subject,

at least in part, to the preclearance requirements of the Voting Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c, precisely because of their history of voting

rights discrimination. See 28 C.F.R. § 51 appendix (1987) (listing states

subject to preclearance requirements); Jeffers v. Clinton, No. H-C-89-

004 (E.D. Ark. May 16, 1990) (three-judge court) (imposing partial

preclearance requirement under section 3(c) of the Voting Rights Act on

the state of Arkansas based on a finding of pervasive intentional

discrimination in the adoption of general election runoff requirements).

6

candidate receives an outright majority, a runoff election

between the top two vote getters is conducted two weeks

after the general election.

This case challenges both of these runoff requirements

as they operate in Phillips County, Arkansas. Petitioners are

black registered voters in Phillips County. Their complaint

alleged that the two runoff requirements interact with social

and historical conditions to deny them an equal opportunity

to participate in the political process and to elect the

candidates of their choice to local and county wide office, in

violation of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973. It further alleged that the

runoff requirements had been adopted and maintained for the

purpose of diluting black voting strength, in violation of

section 2 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to

the Constitution.3

3The district court’s jurisdiction was based on28U .S .C . §§1331,

1343, 2201, and 2202; and 42 U.S.C. § 1973j(f).

7

Statement o f Facts

Phillips County, Arkansas, is a rural, heavily black

county on the Mississippi River. Although a bare majority

of the county’s total population is black, undisputed census

figures show that only 47.00% of the residents of voting age

are black. App. to Pet. for Cert, at 6a & n. 1.

Despite the large number of black residents, no black

candidate has received the Democratic or Republican

nomination for, or been elected to, any county wide office in

Phillips County since the turn of the century. See App. to

Pet. for Cert, at 6a; id. at 125a.

Historically, the primary reason for the lack of black

electoral success was outright disenfranchisement through

such devices as physical intimidation; discriminatory literacy

tests; poll taxes; a white primary; and segregated polling

places. See App. to Pet. for Cert, at 5a; Perkins v. City of

West Helena, 675 F.2d 201 (8th Cir.), aff’d, 459 U.S. 801

8

(1982);4 Smith v. Clinton, 687 F. Supp. 1310 (E.D. Ark.

1988) (three-judge court), aff’d 109 S.Ct.541 (1988). Cf.

App. to Pet. for Cert, at 115a (terming the history of official

discrimination against black voters a "given").

Today, even when black voters do manage to surmount

this legacy of discrimination-as well as the tremendous

barriers that still preclude many of the county’s black

residents from registering and voting, see infra pages 16 to

18—they are still unable to nominate and ultimately to elect

the candidates of their choice because of Arkansas’ primary

runoff requirement.

In the two most recent election cycles for countywide

office in Phillips County, four black candidates, competing

for separate offices, received the highest totals of votes cast

in the first Democratic primary. Yet all four of those

plurality winning candidates were subsequently unable to

4The largest concentration of black voters in Phillips County lives

in West Helena.

9

obtain the Democratic Party nomination because they were

defeated by white candidates in head-to-head primary runoff

contests. (There was no Republican opposition in the

general election for any of these positions.) By contrast, no

white candidate who has ever led a preferential primary in

Phillips County has been defeated in a runoff. In all four

black-white contests in which a black finished first in the

initial election, the white candidate was able to come from

behind to win the runoff.5

There are two major reasons why the runoff system

operates to defeat black candidates: the extreme level of

racial bloc voting in Phillips County and the interaction of

the runoff system with the devastating poverty and

continuing effects of past official discrimination that

permeate the black community.

5

la the two black-white contests in which a white candidate won

the initial election, the white candidate was able to maintain his lead in

the runoff.

10

1. The runoff’s interaction with racial bloc

voting in Phillips County

Voting patterns in Phillips County are characterized by

"extreme" racial polarization. App. to Pet. for Cert, at

107a; 116a. Petitioners’ expert political scientists as well as

experienced political observers of the Arkansas Delta—both

white and black, Republicans and Democrats—testified

without contradiction to the extraordinary levels of bloc

voting.

Dr. Richard L. Engstrom, Research Professor of

Political Science at the University of New Orleans, whose

work on racial bloc voting has been cited with approval by

this Court in Gingles, 478 U.S. at 53 n. 20 and 55,

performed both extreme case analysis and bivariate

ecological regression analysis on the fifteen county-wide,

city-wide, and state legislative elections since 1984 in which

both black and white candidates competed. He concluded

that in all fifteen elections, voting was racially polarized as

11

that term was defined in Gingles: black candidates were

supported by an average of over 94 percent of black voters,

but in no contest did more than 4.9 percent of the white

voters support a black candidate; in six of eight countywide

races, virtually no white voters supported the black

candidate.

The extreme racial bloc voting to which Dr. Engstrom

testified was demonstrated once again by the results of the

1988 preferential and runoff primaries. The preferential

primary took place on the second day of the trial in this

case. Two black candidates sought the Democratic

nomination for different countywide offices and received the

support of over 90 percent of the voters in the virtually

homogeneous black precincts while receiving less than 6

percent of the votes from the virtually homogeneous white

precincts. Sam Whitfield came in first in a four-way race,

receiving 37.4 percent of the vote, and Linda Whitfield lost

a challenge to the white incumbent, receiving 42.9 percent

12

of the vote in a head-to-head contest.

In the runoff election two weeks later (in which Sam

Whitfield, the preferential primary winner, competed and

lost to the white candidate who had finished second in the

preferential primary), voting was even more polarized, with

Sam Whitfield receiving an average of 95.6 percent of the

votes in the overwhelmingly black wards and an average of

only 3.1 percent in the overwhelmingly white wards.6

Party officials also testified that voting in Phillips

County is racially polarized. John Anderson, the chairman

of the county Democratic Party, testified that race is a

"more significant" factor in Phillips County politics than it

used to be and that "both sides will vote for white

[candidates] because they’re white or a black because they’re

black regardless of the reputations or ability of either

candidate." Bankston Waters, the head of the Republican

^The results of the runoff primary were admitted into evidence as

a supplemental exhibit pursuant to the district court’s order.

13

Party in Phillips County, also stated that voting in Phillips

County split along racial lines. The same conclusion-that

voting in Phillips County was extremely racially

polarized—was reached by every lay witness who addressed

the question. Not a single witness testified to any white

crossover voting in a single election contest in Phillips

County.

Racial bloc voting interacts with the runoff requirement

to deprive black voters in Phillips County of the opportunity

to nominate and elect their preferred candidates in this

fashion. The electorate in the county is primarily white.

See App. to Pet. for Cert, at 6a, 22a, 105a. Thus, a black

candidate can finish first only when the white community

splits its support among two or more (invariably white)

candidates. A black candidate has never received a majority

of the votes cast in a primary election; at best, he or she has

finished first by a plurality. The majority-vote requirement

necessarily forces a black plurality winner into a head-to-

14

head contest against one white opponent. In such a contest,

pervasive racial bloc voting has guaranteed that the white

candidate will win.

For white voters, the majority-vote requirement lets

them, in effect, have a separate white primary in the

preference race among themselves, with the most popular

white candidate being able to attract the support of all white

voters in the black-white runoff. As U.S. Assistant

Attorney General Dunne noted, the runoff serves as an

"electoral steroid" for the remaining white candidate, by

giving him or her an additional, artificially contrived, boost

to win the nomination.

In any event, the majority-vote requirement has not in

fact resulted in the winning candidate being the choice of a

majority of those voting in Phillips County. Turnout in

every runoff primary in Phillips County was lower than

turnout in the preferential primary. In three of the four

runoff primaries in which black candidates were overtaken

15

by whites who had finished behind them, the winner’s total

votes, although a majority of the votes cast in the runoff,

did not represent a majority of the total votes cast in the

preferential primary. (The winning total in the runoff was

46 percent of the number of votes cast in the preferential

primary for county judge; the winning total in the runoff

was 46 percent of the number of votes cast in the

preferential primary for circuit clerk; and the winning total

in the runoff was 42 percent of the number of votes cast in

the preferential primary for coroner See, e.g., Trial

Transcript at 556-60, 563-64, 589). In fact, in one of the

four runoffs, the decline in turnout was so steep that the

white runoff "victor" actually received fewer total votes in

the runoff than the black plurality winner had received in

the preferential primary! Id.

16

2. The runoff’s interaction with other

social and historical conditions in

Phillips County

Several features of the runoff system as it

interacts with social and political factors in Phillips County

exacerbate its discriminatory impact. Phillips County’s

black residents suffer from "devastating" poverty. App. to

Pet. for Cert, at 119a. With respect to education and

income~the socioeconomic indicators most closely correlated

with political participation-blacks in Phillips County lag far

behind whites.7 Petitioners’ expert, Dr. Richard L.

Engstrom, testified that he had never analyzed data for an

area in which the black community was as disadvantaged, in

both absolute and relative terms, as it is in Phillips County.

The median years of school completed by white adults in Phillips

County is 12.2, compared to 8.4 for blacks, and 58.3 percent of white

adults are high school graduates, whereas only 22.9 percent of black

adults are high school graduates. Per capita black income in Phillips

County is only $2336, and the median family income in Phillips County

for black families in Phillips County ($6437) is only 39 percent of the

median family income for white families in the county ($16,440). A

majority of black families in Phillips County (53.6 percent) have incomes

below the federally defined poverty level, and over four times as many

black families as white families live below the poverty line.

17

Access to motor vehicles and telephones is a

particularly important socioeconomic indicator for political

participation because these politically relevant private

resources are critical to effective voter mobilization,

including seeking information about registration

requirements and getting out the vote on election day. The

district court recognized that "not having a telephone or an

automobile makes it more difficult and less convenient for a

citizen to qualify for, and to exercise, his or her voting

rights." App. to Pet. for Cert, at 123a. The black

community has far less access to these critical resources than

does the white community. While only 9.0 percent of white

households have no vehicle available, and only 10.9 percent

have no telephone, 42.0 percent of black households have no

vehicle and 30.5 percent have no telephone.

Many poor and less educated black citizens in Phillips

County were unaware of their political rights; they still

believed that they must pay a poll tax to be entitled to vote.

18

Others, who are economically dependent on the white

community, are intimidated from full participation. Some

lack transportation to get to polling places, which are often

located long distances from black neighborhoods. Still

others, worn down by generations of racism and oppression,

have a sense of futility about the efficacy of the political

process. Cf. App. to Pet. for Cert, at 123a (recognizing

that "lack of education" and feelings of "estrangement,

frustration, [and] futility" are "likely bases" for

nonparticipation in politics).

These socioeconomic factors interacted in five separate

ways with the runoff requirement to further decrease the

political efficacy of Phillips County’s black citizens. First,

the short period of time between the preferential election and

the runoff crippled fundraising in the economically

disadvantaged black community. Second, the short time

period made it difficult for black candidates to educate their

often politically unsophisticated supporters about the need to

19

return to the polls despite the black candidate’s apparent

victory.8 Third, because fewer black candidates are

competing in the runoff election (since the results for many

offices were already determined by the preferential primary)

there were fewer get-out-the-vote activities in the black

community and the financial burdens on the remaining black

candidates were greater. Fourth, the fact that polling places

in the black community were changed, without advance

notice, on the eve of the election and between preferential

and runoff elections,9 depressed black participation since

many black voters were confused or discouraged from

8Linda Whitfield testified that she received numerous congratulatory

calls after her first place showing in the May 1986 primary, from people

who did not understand that she had not yet won the nomination. Many

blacks, even after being told that they had to return to the polls a second

time, refused, saying "Well, the white folks are just going to take it

away from you."

9

One witness testified without contradiction that in Ward 1, West

Helena, a 98 percent black precinct with the highest concentration of

blacks in Phillips County, polling places were changed five times in ten

election contests over a two year period.

20

participating.10 Indeed, it is uncontested that in every runoff

election black participation declined from its rate in the

corresponding preferential election. Fifth, runoffs further

polarized an already divided community.11 In sum, the use

of runoff elections in Phillips County exacerbates the

numerical and socioeconomic disadvantages of the black

community, while enhancing the likelihood that racial bloc

voting will result in the defeat of the candidate preferred by

the black community.

By contrast to the virtually certain defeat of their

preferred candidates in runoff systems, black voters within

10Iii jurisdictions covered by section 5 of the Voting Rights Act (at

the time of the trial in this case Arkansas was not yet subject to section

5), changes in polling places must be approved in advance by either the

Attorney General of the United States or the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia, precisely because such changes pose the

potential for intentional discrimination against minority voters or for a

discriminatory impact on minority political participation. See Perkins v.

Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971).

UFor example, using extreme case analysis, white crossover votes

for black candidate Sam Whitfield decreased between the 1988

preferential primary and the 1988 runoff. Moreover, in 1986, a few

store owners who initially accepted Linda Whitfield posters along with

those of white candidates in the first primary refused her literature but

not that of the white candidate in the runoff.

21

Phillips County have been able to elect their preferred

candidates to local office under plurality-win systems. See

Perkins v. City of West Helena, 675 F.2d 201, 203 (8th

Cir.), affd, 459 U.S. 801 (1982). Thus, the presence of a

runoff has a direct causal relationship to the inability of

black voters in Phillips County to elect the candidates of

their choice.

3. The tenuousness o f the policy

underlying the use o f runoff

primaries

The sole justification for the use of runoffs articulated

by respondents was that it fosters the election of candidates

who represent the views of a majority of the population. As

we have already seen, however, the use of runoffs in

Phillips County does not have that effect. See supra pages

14 to 15. In addition, however, the very structure of

Arkansas’ election laws shows that this is not in fact a

consistent state purpose. Under the Arkansas Constitution,

22

the State s six "constitutional" offices—Governor, Secretary

of State, Treasurer, Attorney General, Auditor, and

Commissioner of Lands-may all be elected by a simple

plurality. Indeed, in Rockefeller v. Matthews, 249 Ark.

341, 459 S.W.2d 110 (1970), the Arkansas Supreme Court

struck down as unconstitutional an attempt to extend the

majority-vote requirement to the general election for these

positions. Similarly, state senators and representatives may

be elected by a plurality, rather than a majority. Thus,

neither the State Constitution nor any state statute applies a

majority-vote requirement to these critical state positions.12

^ O t until 1975 did the state impose a majority-vote requirement in

any local general elections; not until 1983 did it create a statewide

majority-vote requirement for most county or local general elections; not

until 1990 did it extend that requirement to municipal offices in all cities

and towns. In all three cases, the imposition of the requirement was

racially motivated: it followed directly on the heels of a black candidate’s

having achieved a plurality victory. See Jeffers v. Clinton, No. H-C-

89-004 (E.D. Ark. May 16, 1990), slip op. at 24:

"We cannot ignore the pattern formed by these enactments.

Devotion to majority rule for local offices lay dormant as long

as the plurality system produced white office-holders. But

whenever black candidates used this system successfully-and

victory by a plurality has been virtually their only chance at

success in at-large elections in majority-white cities—the

23

The state never explained why its purported interest in

majority rule is served by requiring a majority vote for

nomination by a primary while permitting election by a

plurality.* 13

Nor, despite the district court’s suggestion, does the

runoff requirement enhance coalition-building within political

parties. See App. to Pet. for Cert, at 73a, n.l; see also

103a. There was no evidence in the record to suggest that

response was swift and certain. Laws were passed in an

attempt to close off this avenue of black political victory.

This series of laws represents a systematic and deliberate

attempt to reduce black political opportunity. Such an attempt

is plainly unconstitutional. It replaces a system in which

blacks could and did succeed, with one in which they almost

certainly cannot. The inference of racial motivation is

inescapable."

13The district court observed that ”[i]n the hierarchy of the

fundamental values of a democratic states, the manner in which political

parties choose to identify their nominees for public office positions is not

as important as the procedures used to control the actual election of such

public officers." App. to Pet. for Cert, at 71a n. 1. With respect to the

fundamental value of racial fairness contained in the Constitution and the

Voting Rights Act, the district court was wrong: racial discrimination is

forbidden in the nomination process as well as the general election itself.

See, e.g., Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) (white primary

violates Fifteenth Amendment); Voting Rights Act, § 2(b) (violation of

section 2 is established when the processes leading to "nomination or

election" are not equally open) (emphasis added).

24

the desire to promote coalition-building was in fact a state

policy; indeed, the respondents never mentioned such a

goal. Nor, using the district court’s own analysis, could

enhancing biracial appeals have been a purpose in enacting

a primary runoff requirement, since the requirement was

adopted at a time when blacks were completely excluded

from the Democratic Party, App. to Pet. for Cert, at 70a.

To the contrary, the evidence showed that runoff

requirements have been adopted in Arkansas because they

enable the white community to exclude blacks from the

coalition-building process. See supra note 12. Finally, the

evidence is unrebutted in this case that because whites

absolutely refuse to support black candidates in Phillips

County, the majority-vote requirement does just the

reverse-it promotes coalition building within the white

community only. In the first primary, white voters can

select the most popular white candidate to then coalesce

behind in the runoff to defeat the black candidate. Election

25

returns from Phillips County showed that polarization was

often more extreme in the runoff than it was in the initial

election.

Course of the Proceedings Below

Petitioners’ complaint challenged both Arkansas runoff

statutes, claiming that they violated, the results test of

amended section 2 as well as the intent tests of both

amended section 2 and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments.14 After a three-day trial, in which the state

attorney general represented the respondent Democratic

Party organizations despite the fact that every state official

defendant had been dismissed from the lawsuit, the district

14On the eve of trial, the district court dismissed petitioners’

challenge to the general election runoff on the ground that the governor

and secretary of state were not proper and adequate defendants in such

a lawsuit; instead, the district court held, petitioners were required to

have sued the local election officials actually responsible for conducting

elections and counting the ballots. See App. to Pet. for Cert, at 141a;

id. at 155a. In addition, it dismissed petitioners’ suit because no black

candidate had in fact lost a general election in a runoff. Id. at 164a-

167a.

26

court dismissed petitioners’ challenge to the primary runoff

statute. It concluded, first, that because blacks were a

majority of the total population (although not of the

electorate), they were barred as a matter of law from

bringing a section 2 claim. App. to Pet. for Cert, at 107a-

108a. Second, although the district court recognized that the

Senate Report had expressly singled out the majority-vote

requirement as a discrimination-enhancing device, it declined

to give any weight to that conclusion. See App. to Pet. for

Cert, at 118a. Indeed, it described the Senate Report

factors, upon which this Court placed great weight in

(Singles as "more [of] a distraction than a useful tool for

evaluating the cause and effect operation of the challenged

runoff laws." App. to Pet. for Cert, at 130a. It held,

essentially, that majority-vote requirements were so central

to democratic principles that they were immune from attack

as racially discriminatory devices.

A divided panel of the Eighth Circuit reversed. It

27

found that the undisputed evidence showed that black voters

were in fact a minority of the Phillips County electorate

(and the district court’s finding to the contrary was

unsupported by any record evidence) and held that, in any

event, section 2’s protection was not limited to numerical

minorities. See App. to Pet. for Cert, at 20a-22a. It

further held that the district court had committed critical

legal error in refusing to apply the analysis set out on pages

28-29 of the Senate Report and approved by this Court in

Gingles, App. to Pet. for Cert, at 26a-27a. It noted the

uncontested evidence regarding the presence of critical

Senate Report factors—such as a history of discrimination;

extreme bloc voting; "devastating" socioeconomic

deprivation; the "dominati[on] over qualifications and

issues" of candidates’ racial identity; and the complete lack

of black electoral success, App. to Pet. for Cert, at 28a-

29a—and concluded that "based on the proof set forth by

Whitfield and the totality of the circumstances in Phillips

28

County, a section 2 violation has been established under the

results test." App. to Pet. for Cert, at 37a.15

The Eighth Circuit granted respondents’ motion for

rehearing en banc. After reargument, the court of appeals

affirmed the district court by an equally divided vote.16

15It affirmed the district court’s dismissal of the challenge to the

general election on the ground that petitioners had failed to show that a

black candidate had been defeated in a general election runoff in Phillips

County. App. to Pet. for Cert, at 37a n. 4.

16Five of the nine active judges on the Eighth Circuit—Chief Judge

Lay and Judges McMillian, John R. Gibson, Fagg, and Beam—would

have reversed the district court. App. to Pet. for Cert, at 2a. The tie

was the result of the fact that Senior Circuit Judge Bright was permitted

to sit because he had sat on the original panel. See 8th Cir. R. 16(a).

29

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I. This Court Should Grant Certiorari

to Provide the Lower Courts with

Guidance on How to Treat Section

2 Claims Challenging Runoff

Requirements

In Gingles, this Court did not address the question of

how the lower courts should assess section 2 claims

involving challenges to runoff election requirements. See

478 U.S. at 46 n. 12. The deadlock in the en banc Court

of Appeals in this case, in which five circuit judges voted to

affirm a district court that rejected completely the

applicability of the Senate Report factors and this Court’s

opinions, shows how necessary further guidance from this

Court is to the proper functioning of the Voting Rights Act.

All three branches of the government have repeatedly

recognized the discriminatory impact of runoff requirements

in jurisdictions where blacks are a minority of the electorate

and racial bloc voting exists. The Senate Report

30

accompanying the 1982 amendment of section 2, which this

Court has termed an "authoritative" source of congressional

intent, Gingles, 478 U.S. at 43 n. 7, explicitly identifies

majority vote requirements as a practice that can "enhance

the opportunity for discrimination against the minority

group." Senate Report at 29. See also Voting Rights Act:

Runoff Primaries and Registration Barriers: Oversight

Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Civil and Constitutional

Rights o f the House Comm, on the Judiciary, 98th Cong 2d

Sess. (1984) (collecting data and testimony regarding the

discriminatory impact of runoff primaries).

This Court has also repeatedly found that runoff

requirements improperly minimize black voting strength. In

City o f Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980), for

example, this Court held that a change from a plurality-win

system to a runoff system would have a discriminatory

effect on black voters in Rome, Georgia:

[Ujnder the pre-existing plurality-win system, a

31

Negro candidate would have a fair opportunity to

be elected by a plurality of the vote if white

citizens split their votes among several white

candidates . . . . The 1966 change to the majority

vote/runoff election scheme significantly decreased

the opportunity for such a Negro candidate since,

even if he gained a plurality of votes in the general

election, [he] would still have to face the runner-

up white candidate in a head-to-head runoff election

in which, given bloc voting by race and a white

majority, [he] would be at a severe disadvantage.

Id. at 183-84 (bracketed materials in this Court’s opinion;

internal quotation marks omitted); see also, e.g, , Gingles,

478 U.S. at 39 (discussing three-judge court’s finding that

North Carolina’s majority-vote requirement posed "a

continuing practical impediment to the opportunity of black

voting minorities to elect candidates of their choice"); City

o f Port Arthur v. United States, 459 U.S. 159, 167 (1983)

(striking down runoff requirement for municipal elections

under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act).

Finally, the Attorney General, whose interpretations of

the Act have been accorded "great deference" by this Court,

United States v. Board of Commissioners of Sheffield,

32

Alabama, 435 U.S. 110, 131 (1978), has also repeatedly

found that runoff requirements impermissibly diminish back

voting strength. Indeed, during the period 1975-1980, the

Attorney General objected, under section 5 of the Voting

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c, to the adoption of sixty-six

separate majority-vote requirements. Only annexations and

at-large elections occasioned more objections. U.S.

Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights Act:

Unfulfilled Goals 187 (table 6.4) (1981) (compiling data

regarding section 5 objections). And earlier this month, the

United States filed suit against the state of Georgia, seeking

the invalidation of its primary runoff statute under section 2.

The court below squarely rejected the position taken by

this Court, Congress, and the Attorney General:

It is interesting to note that the U.S. Supreme

Court apparently has suggested that "majority"

voting is a procedure that "may enhance the

opportunity for discrimination." That is far from

clear to the Court based on the evidence and

authorities it has reviewed.

33

App. to Pet. for Cert, at 118a. In place of the intensely

local, fact-specific appraisal required by Congress and this

Court, it announced two novel and unsupportable legal

principles. First, it rejected the applicability of the Senate

Report factors to section 2 results claims. See, e.g. , App.

to Pet. for Cert, at 130a ("the positive findings with respect

to the Senate Report factors have no tendency to prove" a

section 2 violation; instead, they serve as "a distraction");

id. at 111a (the Senate Report factors "more logically

support proof relating to ’intent’ issues that ’cause and

effects’ issues"). Second, it held that runoff requirements

(which this Court has found racially discriminatory) are so

fundamental a part of the American democratic system that

they are simply immune from attack. Id. at 81a-82a.

This Court’s opinion in Gingles provided lower courts

with guidance on how to assess claims of vote dilution

through submergence in multimember districts. See Gingles,

478 U.S. at 48-51 (setting out how the Senate Report factors

34

should be applied to claims that multimember districts

violate section 2). However, it is clear from Whitfield and

from the Second Circuit’s opinion in Bum v. City o f New

York, 779 F„2d 141, 148-49 (2d Cir. 1985) (also holding

that runoff requirements are not subject to challenge under

section 2), cert, denied, 478 U.S. 1021 (1986), that lower

courts faced with challenges to runoffs are refusing to apply

the "intensely local appraisal of the design and impact of the

contested electoral mechanism" based "upon a searching

practical evaluation of the past and present reality" of

politics within the relevant jurisdiction that this Court and

Congress have mandated, Gingles, 478 U.S. at 79 (internal

quotation remarks omitted); Senate Report at 30. This Court

should grant certiorari to clarify the standards for assessing

these increasingly common section 2 claims.

35

II. The Per Se Rule that Section 2 Does Not

Protect Black Voters if Blacks Constitute

a Majority of the Population (But Not a

Majority of the Voting Age Population)

Announced in this Case Squarely

Conflicts with Decisions of this Court and

the Other Courts of Appeals

According to the most recent available, uncontested,

census data, blacks form a bare majority of Phillips County’s

total population. (They are, however, a distinct minority of

the population of voting age.)17 The court below held that,

"as a matter of law, the undisputed population figures here

are not such as will permit the plaintiffs to challenge the

primary runoff law of the state of Arkansas as a violation of

section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, as amended," App.

to Pet. for Cert, at 106a-107a, since blacks were not a

"minority," within the meaning of the statute.

1?The district court’s suppositions to the contrary were clearly

erroneous, as the stipulated figures from the Census Bureau show that

blacks constitute 52.94 percent of the total population and 47.00 percent

of the population of voting age. See App. to Pet. for Cert, at 6a. The

stipulated figures also showed that the number of blacks in the county

has been steadily declining over the past three decades. Finally, it was

uncontested that blacks are a minority of registered voters.

36

That conclusion represents a complete misreading of

section 2. The text of section 2 never uses the word

"minority." By its terms, section 2 prohibits discrimination

against "any citizen of the United States" on the basis of

race or color, section 2(a) (emphasis added), and condemns

electoral arrangements not equally open to participation by

"members of a class of citizens protected by subsection (a),"

section 2(b), without placing any strictures on the relative

size of that class.

This rule conflicts with the decisions of this Court in

two separate ways.

A. This Court Has Rejected the Use of

Per Se Rules in Section 2 Cases

In Gingles, this Court held that in a section 2 lawsuit,

the trial court is to consider the "totality of the

circumstances" and to determine, based "upon a

searching practical evaluation of the ’past and

present reality,”' S. Rep. 30 (footnote omitted),

whether the political process is equally open to

minority voters. "’This determination is peculiarly

dependent upon the facts of each case,’" Rogers [v.

Lodge, 458 U.S.] at 621, quoting Nevitt v. Sides,

37

571 F.2d 209, 224 (CA5 1978), and requires "an

intensely local appraisal of the design and impact"

of the contested electoral mechanisms. 458 U.S.,

at 622.

478 U.S. at 79. "The essence-of a § 2 claim," then, is "that

a certain electoral law, practice, or structure interacts with

social and historical conditions to cause an inequality in the

opportunities enjoyed by black and white voters to elect their

preferred representatives." Id. at 47.

This Court’s interpretation in Gingles, as well as the

actual outcome (which affirmed the finding of liability in

four legislative districts and reversed the finding of liability

in a fifth), thus clearly require jurisdiction-specific

consideration of challenged electoral mechanisms, rather than

the development of per se rules regarding the legitimacy of

various practices.

Despite this clear directive, the court in this case

announced a per se rule: "as a matter of law," regardless of

social and historical conditions within Phillips County,

38

petitioners were barred from bringing a section 2 challenge

to Arkansas5 runoff requirements. App. to Pet. for Cert, at

106a-107a. Rather than discussing political reality in

Phillips County, Arkansas, in 1988 or at any other time, the

court’s discussion focused on conditions in France, id. at

81a; Chile at the time of Allende’s election in the 1970’s,

id. at 81a-82a; New York City during the 1970’s, id. at 74a-

78a; Virginia and Chicago, id. at 94a; and gubernatorial

politics generally in the South between 1932 and 1977, id.

at 99a and 102a. It relied on the experience with runoffs in

these situations to hold that runoff provisions cannot be

attacked under section 2. Such an approach clearly conflicts

with the approach taken by this Court in Gingles. This

Court should grant certiorari to make clear that the Voting

Rights Act does not permit the erection of per se barriers to

section 2 claims.

39

B; The Specific Per Se Rule Created in

this Case Conflicts with this Court’s

Decisions in White v. Regester and

Rogers v. Lodge and with Decisions

of the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits

In this case, the court held that petitioners were barred

as a matter of law from bringing a section 2 lawsuit because

they were not a numerical minority in Phillips County. (In

fact, blacks are a numerical minority of the voting-age

population.) No other court has ever held that black voters

are barred as a matter of law from bringing a section 2

lawsuit because black residents outnumber white residents of

the relevant jurisdiction. To the contrary, both this Court

and the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits have recognized that

electoral arrangements can illegally diminish the voting

strength of black voters even when they are a majority of

the electorate.

Two of this Court’s leading voting rights cases, White

v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973), and Rogers v. Lodge, 458

40

U.S. 613 (1982), have reached precisely the opposite

conclusion. Rogers involved a challenge to at-large

elections in Burke County, Georgia, which was 53.6 percent

black. Id. at 614. Despite this numerical superiority, the

Court concluded that the system denied black voters an

ability to elect their preferred candidates. And in White,

roughly half the population of Bexar County, Texas, was

Mexican-American. The White district court squarely

rejected the idea that only numerical minorities are

protected: Such a position

misconceives the meaning of the word "minority".

In the context of the Constitution’s guarantee of

equal protection, "minority" does not have a merely

numerical denotation; rather it refers to an

identifiable and specially disadvantaged group.

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704, 730 (W.D. Tex. 1972)

(three-judge court), aff’d in relevant part and rev’d in part

on other grounds sub nom. White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755

(1973); see also 412 U.S. at 767 (district court properly

41

treated plaintiffs as a minority).18

Moreover, the decision in this case squarely conflicts

with recent holdings of the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits. In

Monroe v. City ofWoodville, 819 F.2d 507 (5th Cir. 1987),

the Fifth Circuit held that the fact that blacks constitute a

majority of a jurisdiction’s population cannot as a matter of

law preclude a section 2 lawsuit. Monroe involved a

challenge to at-large elections in a city whose total

population was 60.5 percent black. Id. at 508. The Fifth

Circuit held that plaintiffs must be given the opportunity to

prove that, despite this numerical predominance, they did not

enjoy the equal opportunity to elect the candidates of their

choice. Id. at 511. Similarly, the Eleventh Circuit found a

18White was one of two cases on which the Senate relied in

articulating the section 2 "results test." The other was Zimmer v.

McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc), aff’d on other

grounds sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424

U.S. 636 (1976) (per curiam). See Senate Report at 23, 27-28. Zimmer,

like White v. Regester involved a predominantly minority jurisdiction.

East Carroll Parish, Louisiana, was roughly 59 percent black in total

population, 485 F.2d at 1301. Nonetheless, there too the court found

racial vote dilution.

42

section 2 violation in Dallas County, Alabama, which was

55 percent black in total population and 49 percent black in

voting-age population. United. States v. Dallas County

Commission, 850 F.2d 1430, 1434 (11th Cir. 1988).

In sum, a clear conflict exists between the numerical

threshold rule applied in this case and the approaches taken

by this Court and the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits.

in. The Holding Below that the

Governor and Secretary of

S t a t e a r e n o t P r o p e r

Defendants to a Statutory and

Constitutional Challenge to a

General Election Ru n o ff

Statute Conflicts with Almost

Three Decades of this Court’s

Decisions

Petitioners’ statutory and constitutional challenges to

Arkansas’ "systematic and deliberate attempt to reduce black

political opportunity" through the enactment of a series of

general election runoff statutes, Jeffers v. Clinton, No. H-

C-89-004 (E.D. Ark. May 16, 1990) (three-judge court),

43

slip op. at 24,19 was dismissed, prior to trial because the

district court held that a challenge to a statewide election

statute cannot be maintained against the Governor and

Secretary of State as the only defendants. First, it held that

plaintiffs wishing to bring such a challenge must also name

the local officials physically responsible for running the

elections:

You’ve got to serve the people, it seems to me,

who are charged with the duty of conducting the

election or to effectuate the statute you are

challenging. The Governor as such and the

Secretary of State as such are not those people.

App. to Pet. for Cert, at 141a-142a. Second, it held that,

because the duties performed by the Governor and Secretary

are purely ministerial and compelled by statute, the

Governor and Secretary are improper parties in any event:

[N]o claim of wrongdoing has appropriately been

asserted against those defendants . . . . [I] f the

Court were to require that the defendant political

county committees certify certain candidates, "the

The opinion in Jeffers was issued only a fortnight after the en banc

decision in this case.

44

separate defendants Clinton and McCuen cannot

exercise their legal function in any way other than

to issue commissions and certify candidates and

results certified by local authorities."

App. to Pet. for Cert, at 155a. These holdings directly

conflict with the longstanding precedents of this Court.

This Court has consistently treated governors and

secretaries of state as proper and adequate defendants in

voting rights cases, despite the fact that these officials

neither physically conduct actual elections nor have any

discretion under the state statutory schemes.

In the seminal case of Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186

(1962), the lead defendant, Joe C. Carr, was the Tennessee

Secretary of State. The duties that made him a proper

defendant—furnishing envelopes and forms to county election

commissions; maintaining election returns sent to him by the

county commissions; and, along with the governor, declaring

election results, id. at 205 n. 25-are identical to the duties

performed by Secretary McCuen in this case. See Ark. Stat.

45

Ann. §§ 7-5-203 (secretary certifies lists of candidates to

county commissions), 7-5-701(d) (secretary maintains

election records); 7-5-704(a) (secretary informs governor of

identity of winning candidates).

In case after case since Baker v. Carr, this Court has

treated governors and secretaries of state as proper and

adequate defendants in vote-dilution litigation. See, e.g.,

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964) (governor and

secretary of state were only defendants); Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533 (1964) (secretary of state); Fortson v, Dorsey,

379 U.S. 433 (1965) (secretary of state as only defendant);

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) (governor as only

defendant); White v. Regester, 422 U.S. 935 (1975)

(governor). Cf. Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)

(county commissioners elected under at-large system being

challenged were proper defendants although they had nothing

to do with enactment or maintainance of system or with

actual running of elections); Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S.

46

30 (attorney general as defendant in section 2 case). No

court has ever required the actual local officials who conduct

elections also to be named.

Furthermore, in none of the cases cited in the previous

paragraph was there any allegation that the relevant state

official had himself willfully violated federal law. In each

case, the named defendants performed solely ministerial

duties.

Since Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908), it has been

clearly established that plaintiffs may maintain federal

lawsuits against state officials that allege that those officials’

performance of ministerial duties denies the plaintiffs some

federal right. The fact that state law requires the officials to

act as they have has never before been used to immunize

them from a suit requiring injunctive relief. Every Term,

this Court decides cases involving claims for declaratory and

injunctive relief against state officials performing their duties

in accordance with state law. See, e.g. , Butterworth v.

47

Smith, 110 S.Ct. 1376 (1990) (state attorney general as

defendant in lawsuit challenging enforcement of state grand

jury secrecy statute); Quinn v. Millsap, 109 S.Ct. 2324

(1989) (mayor and governor as defendants in lawsuit

challenging property ownership as qualification for

appointment to local board); Eu v. San Francisco County

Democratic Central Committee, 109 S.Ct. 1013 (1989) (state

secretary of state as defendant in lawsuit challenging statute

regulating political parties). In fact, this Court has viewed

officials performing ministerial functions as appropriate

defendants even in cases where the official in fact agrees

with the plaintiff’s claim but is constrained by statute. See,

e.g., INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983).

In sum, the lower court’s position in this case would

require the complete abandonment of the entire structure of

federal judicial review that has been erected since Ex parte

Young. This Court should grant certiorari to make clear that

plaintiffs may seek injunctions against state officials whose

48

ministerial acts violate federal law.20

20The alternative ground for dismissal-that petitioners lacked

standing to challenge the general election runoff statute because they had

not lost an election, as candidates, due to the operation of the general

election runoff, see App. to Pet. for Cert, at 155a~also squarely conflicts

with congressional intent, Gingles and decisions of other circuits.

This Court has squarely held that section 2 liability (and therefore

a fortiori standing) can be established even in cases where no minority-

preferred candidate has yet been defeated by the operation of the

challenged practice. "Where a minority group has never been able to

sponsor a candidate, courts must rely on other factors that tend to prove

unequal access to the electoral process." Gingles, 478 U.S. at 57 n. 25.

Thus holding is critical to the operation of the Voting Rights Act, since

one of the major consequences of discriminatory practices is that they

deter the minority community from sponsoring candidates in the first

place. See, e.g., McMillan v. Escambia County, 748 F.2d 1037, 1045

(11th Cir. 1984); Citizens fo r a Better Gretna v. City o f Gretna, 834

F -2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987); Hendrix v. McKinney, 460 F. Supp. 626, 631-

32 (M.D. Ala. 1978) (Frank Johnson, J.).

49

C o n c l u sio n

For the reasons stated above, this Court should grant

the petition for a writ of certiorari to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

Pamela S. Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22903

(804) 924-7810

Oily Neal

Neal Lawyers

33 North Poplar Street

Marianna, AR 72360

(501) 295-2578

Julius L. Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Dayna L. Cunningham

Sherrilyn A. Ifill

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

*C. Lani Guinier

University of Pennsylvania

Law School

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

(215) 898-7032

Counsel for Petitioners

*Counsel of Record

August 27, 1990