Memorandum in Opposition to Suburban Motions to Dismiss

Public Court Documents

March 16, 1975

6 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Memorandum in Opposition to Suburban Motions to Dismiss, 1975. 7a53993e-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ddbbdd89-a3db-44ae-ada1-2b5494eda644/memorandum-in-opposition-to-suburban-motions-to-dismiss. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

♦ *

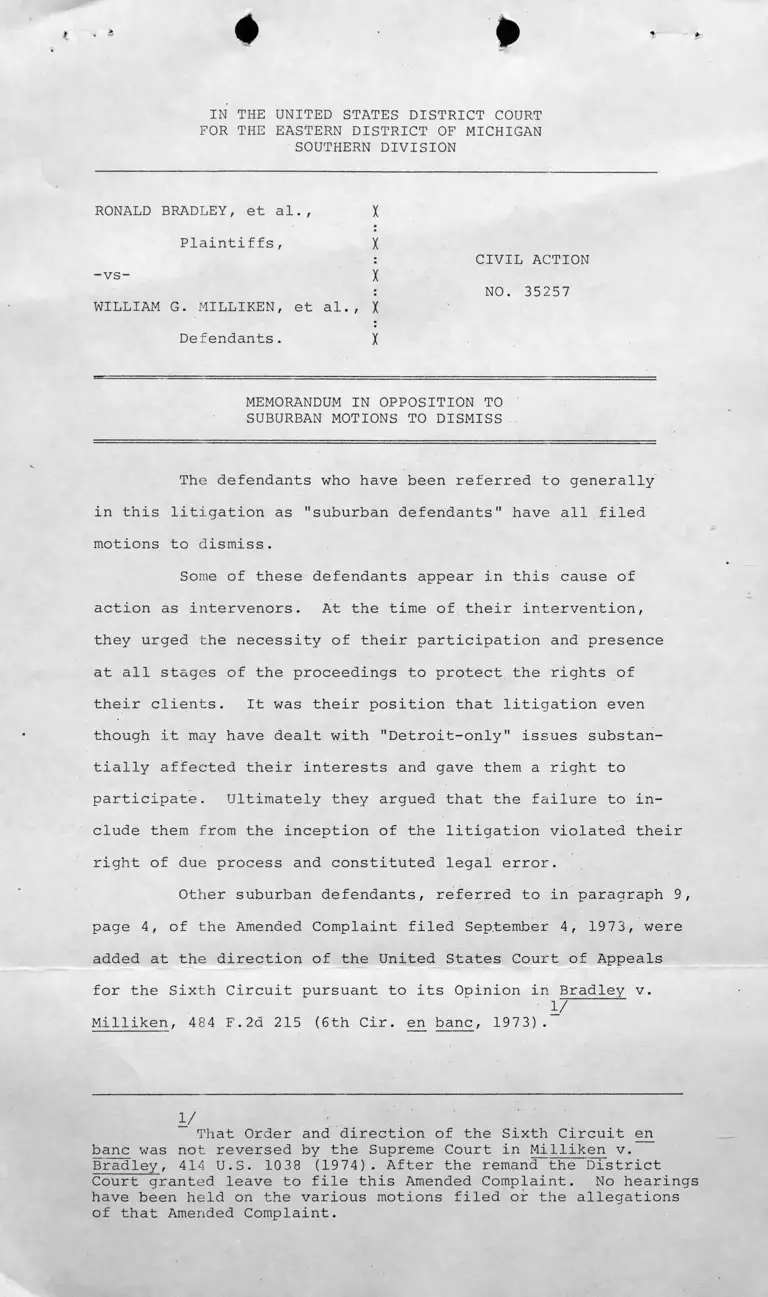

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al., X

Plaintiffs, X

-vs- X

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., X

Defendants. X

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 35257

MEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION TO

SUBURBAN MOTIONS TO DISMISS

The defendants who have been referred to generally

in this litigation as "suburban defendants" have all filed

motions to dismiss.

Some of these defendants appear in this cause of

action as intervenors. At the time of their intervention,

they urged the necessity of their participation and presence

at all stages of the proceedings to protect the rights of

their clients. It was their position that litigation even

though it may have dealt with "Detroit-only" issues substan

tially affected their interests and gave them a right to

participate. Ultimately they argued that the failure to in

clude them from the inception of the litigation violated their

right of due process and constituted legal error.

Other suburban defendants, referred to in paragraph 9,

page 4, of the Amended Complaint filed September 4, 1973, were

added at the direction of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit pursuant to its Opinion in Bradley v.

1/

Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. en banc, 1973).

1/That Order and direction of the Sixth Circuit en

banc was not reversed by the Supreme Court in Milliken v.

Bradley, 414 U.S. 1038 (1974). After the remand the District

Court granted leave to file this Amended Complaint. No hearings

have been held on the various motions filed or the allegations

of that Amended Complaint.

Pursuant to the Order of the Court of Appeals, the

first Amended Complaint alleged in pertinent part as follows

This consistent and repeated discrimination

by State officials and agencies, manifested by,

among others, the acts listed herein, is causu-

ally related in a significant manner to the

present, nearly total segregation of black

children within the tri-county area . . . .

(Emphasis Added).

The Supreme Court of the United States said:

. . . [I]t must be first shown that there

has been a constitutional violation within one

district that produces a significant segregative

effect in another district. Specifically it

must be shown that racially discriminatory acts

of the state or local school district or of a

single school district have been a substantial

cause of inter-district segregation. Milliken

v. Bradley, 41 L.Ed.2d 1069, 1091. (Emphasis

Added).

Plaintiffs have yet to have a hearing on the first Amended

Complaint.

The quoted allegation which we submit is not incon

sistent with the subsequent, Supreme Court mandate, if es

tablished by competent evidence or by fact findings based

upon the present record would furnish a basis, in whole or in

part, for the relief which plaintiffs seek.

The first Amended Complaint further alleges:

In carrying out this pattern and practice

of official segregation, the State and its

agencies have advantaged themselves of existing

school district lines and jurisdictional boun

daries with the effect of further entrenching

the containment of black students in black

Detroit schools; . . . the prevailing patterns

of racially identifiable, virtually all-white

schools in the suburbs of Detroit is a result,

in part, of the official policies of containment

and segregation of black children in racially

identifiable and virtually all-black schools

within the City of Detroit . . . .

•k k k

The school and housing opportunities for

black citizens in the Detroit Metropolitan Area,

however, have been and remain restricted by dis

criminatory governmental and private action to

separate and distinct areas within the city and

a few other areas of historic racial containment

in the metropolitan area.

* ♦ «

The Opinion of Mr. Justice Stewart, as a member of

the majority in Milliken, makes clear that should this Court

reach matters not reached by either the Sixth Circuit or the

Supreme Court in the existing record or should it, after re

ceipt of additional evidence going to these questions, deter

mine that these allegations have been established by competent

evidence, plaintiffs would be entitled to relief.

Mr. Justice Stewart said:

This is not to say, however, that an

inter-district remedy of the sort approved by

the Court of Appeals would not be proper, or

even necessary, in other factual situations.

Were it to be shown, for example, that state

officials had contributed to the separation of

the races. . .; or by purposeful, racially dis

criminatory use of state housing or zoning

laws, then a decree calling for transfer of

pupils across district lines or for restruc

turing of district lines might well be appropriate.

41 L .Ed.2d at 1097.

The defendants quote at some length from the Supreme

Court decision in Milliken, supra. We think it important to

note the extreme care which the Supreme Court used in setting

out those things which it did not reach. The District Court

and the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals were equally explicit

in indicating what portions of the evidence which they had

considered in reaching their determinations that plaintiffs

were entitled to a metropolitan remedy.

The Supreme Court said:

While specifically acknowledging that the

District Court's findings of a condition of

segregation were limited to Detroit, the Court

of Appeals approved the use of a metropolitan

remedy. . . ." 41 L.Ed.2d at 1088.

The Supreme Court pointed out that plans were re

quired to be submitted on a metropolitan basis "despite the

fact that there had been no claim that these outlying counties,

. . . had committed constitutional violations." The Court also

noted the District Court's disclaimer with respect to it's

taking of proof with respect to the suburban defendants. 41 L.Ed.

2d at 1082-83.

- 3 -

*

Again-the Court said:

No evidence was adduced and no findigs were

made in the District Court concerning the activi

ties of school officials in districts outside the

City of Detroit. 41 L.Ed.2d at 1096.

The Court noted that neither the plaintiffs nor the

trial judge considered amending the Complaint to embrace the

new theory. Milliken, supra. 41 L.Ed.2d at 1095.

In summary the Supreme Court, which did not have

before it the Amended Complaint and certainly not the second

Amended Complaint, concluded, speaking of the trial below:

This, again, underscores the crucial fact

that the theory upon which the case proceeded

related solely to the establishment of Detroit

city violations as a basis for desegregating

Detroit schools and that, at the time of trial,

neither the parties nor the trial judge were

concerned with a foundation for inter-district

relief. 41 L,Ed.2d 1069 at 1095.

The Supreme Court noted that Judge Roth in his formal

opinion candidly recognized that:

It should be noted that the Court has taken

no proofs with respect to the establishment of

the boundaries of the 86 public school districts

in the counties of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb, nor

on the issue of whether, with the exclusion of

the City -of Detroit school district, such school

districts have committed acts of de jure segregation.

345 F.Supp. 914,920; 41 L.Ed.2d at 1083 n.ll.

Since there was no "trial" on "metro" violation the

opinion of the Supreme Court did not determine any metro issue.

It did decide that metropolitan relief could not be had solely

on a remedy theory. It approved metro when certain facts are

found to exist. It carefully pointed out that in this case

those facts were not a part of the original Complaint and not

a part of the theory of the original trial, therefore no metro

relief. We have now the allegations of metro violation and

issues to be tried. The parties who insisted their presence

was required now want out.

/

A word about both amended complaints seems in order.

There is much in the way of allegations about housing discrim

ination. In part the reason may be obvious, however, more

- 4-

should be said. The importance of housing proof in light of

the Sixth Circuit decision in Deal, was in serious question

in school cases. School boards, like the Detroit Board,

took the position such evidence had no relevance and was in-

2/

admissible. The Boards would almost in the same breath

claim that housing segregation was entirely responsible for

school segregation. District courts usually permitted some

housing proof but relied on such evidence only in a minimal

way. For example, in this case the Sixth Circuit said:

. . . [w]e have not relied at all upon

testimony pertaining to segregated housing

except as school construction programs helped

cause or maintain such segregation. Bradley

v. Milliken, 484 F.2d at, 242.

However, Justice Stewart's language and other refer

ences in the majority opinion make such proof one of the

critical factors which would require or permit metropolitan

relief.

Both the first and second Amended Complaints stress

this type of housing discrimination allegation and in turn

the relationship, on an inter-district basis to school

segregation.

As the Supreme Court noted, the parties have not

been heard on inter-district violation. It seems to be with

out question that the proof of such violation is bound up in

the existing case and the Detroit school district.

To say that the Supreme Court has looked at the storm

of racial injustice and segregation in Detroit and "blinked"

at a remedy is true. But, to say that it has, (and therefore

this Court must), shut it's eyes forever is false.

Therefore, plaintiffs respectfully submit that the

suburbs' Motions to Dismiss should be denied, the Second

Amended Complaint allowed, and further proceedings therein be

In fact, the Detroit Board's first position was

that there was no housing segregation in Detroit.

2/

- 5-

■4 1 < *

delayed until the first mandate of the Supreme Court, to im-

3/

plement a desegregation plan for Detroit, be obeyed.

Respectfully submitted,

LOUIS R. LUCAS

RATNER, SUGARMON, LUCAS & SALKY

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee

JOHN A. DZIAMBA

746 Main Street

Post Office Box D

Willimantic, Connecticut 06226

ELLIOTT S. HALL

2755 Guardian Building

500 Griswald Avenue

Detroit, Michigan

NATHANIEL JONES

General Counsel

N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL DIMOND

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Lawyers Committee For

Civil Rights Under Law

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

Counsel for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing

Memorandum In Opposition To Suburban Motions To Dismiss has

been served on all counsel of record by depositing same

addressed to them at their office by United States mail, pos-

//**>■tage prepaid, this /(<■' day of March, 1975.

3/

"Within a single school district whose officials

have been shown to have engaged in unconstitutional racial

segregation, a remedial decree that effects every individual

school may be dictated by "common sense," see Keyes v. School

District No. T~, Denver, Colorado, 413 U.S. 189^ 20 3, 37 L . Ed. 2d

548", 9 3 S.CE7 2686 (1973) , and indeed may provide the only ef

fective means to eliminate segregation "root and branch," Green

v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 437, 20. L.Ed.2d 716, 88"

S.Cti 1689 (1968), and to "effectuate a transition to a racially

nondiscriminatory school system." Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 294,301, 99 L .Ed. 1083, 75 S.Ct. 753. Keyes, supra, 413

U.S. at 198-205, 37 L.Ed.2d 548. Milliken, supra, 41 L.Ed.2d at

1097. (Emphasis Added).